1. Introduction

Oropharyngeal dysphagia (OD) is defined as the difficulty in transferring liquids and food from the oropharyngeal cavity into the stomach, and it refers to any abnormality in the swallowing physiology of the upper aerodigestive tract [

1]. It is listed under code MD93 in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), 11th revision [

2]. OD is a common comorbidity among various patient [

3,

4,

5]. Researchers demonstrated that the prevalence of diagnosed OD was 3% in all adult patients admitted to hospitals in the United States [

6] and that it was higher in the population over 75 years old than other age groups [

7]. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis the global prevalence of OD was 43.8% in different patient populations while a sub-group analysis showed that it was high (48.1%) in elderly population [

8].

Critically ill patients are also a vulnerable population in high-risk to develop dysphagia as it is a significant healthcare-acquired complication due to invasive mechanical ventilation. Although the potential mechanism of dysphagia is not yet clear, it can occur after orotracheal extubation (post-extubation dysphagia, PED) even though its etiology is multifactorial [

9]. Earlier studies on intubated patients have reported inconsistent results about incidence rate of PED ranging from 3 to 62% [

10]. A prospective observational trial identified that systematic screening for PED demonstrated a consistently high incidence rate: 12.4% after extubation in the intensive care unit (ICU) and 10.3% at ICU discharge [

11]. Previous studies have also highlighted that PED may persist even after hospital discharge and can last up to six months [

11,

12]. Negative consequences for the ICU patients associated with PED have also been identified including aspiration pneumonia [

13], malnutrition [

14], reintubation [

15], short-term mortality and long-term mortality [

16]. PED also prolongs ICU and hospital length of stay (LOS) [

14] and increases resources use [

17]. Additionally, it increases the risk of poor outcomes in ICU survivors as it has a direct negative impact on their quality of life [

18] and independence [

19]. Therefore, it appears from the above that PED remains a critical issue amongst critically il patients.

Despite PED’s high prevalence and significant association with negative patient outcomes, bedside screening is not routinely conducted, especially where speech/ language therapists are not readily accessible [

20]. Limited awareness, and inadequate knowledge are some of the reasons that were attributed to limited screening for PED in the intensive care units (ICUs) [

20]. Additionally, although a speech and language pathologist/ therapist (SLP/SLT) is helpful in the evaluation and management of dysphagia [

21], dysphagia is a complex problem that requires multi-professional targeted approach [

22,

23]. Moreover, little evidence showed that assessment and management of dysphagia are conducted by nurses and non-specialists in ICUs [

24].

As there has been an increase in life expectancy globally, a higher number of elderly patients will be admitted to the ICUs. Given that dysphagia has been associated with age and frailty [

25,

26] it is apparent that dysphagia is a critical area of concern in ICU patients. In Cyprus, PED prevalence has not previously been identified. Moreover, even though there are speech language therapists who are actively involved in the OD assessment and treatment in the community, there are not known protocols regarding assessment and treatment of dysphagic patients during their hospitalization in ICUs.

PED awareness is an important factor in screening, early diagnosis and treatment of dysphagia, as early identification is positively associated with treatment interventions [

27].

We conducted this study to establish current approaches of Greek Cypriot ICUs to PED screening, management and treatment, as well as their current status of perceived best practices. We also aimed to assess ICU awareness of PED and its consequences.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and settings

We used a cross-sectional online survey design, as part of the international survey titled “Dysphagia in Intensive Care Evaluation (DICE)” in which 26 countries, including Cyprus, participated [

24]. The study was conducted in all adult ICUs in the Republic of Cyprus. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) was followed [

28].

2.2. Participants

According to the original study (DICE) [

24], the participants were all adult Creek-Cypriot ICUs. The Cypriot national coordinator of the study was responsible, through her personal and professional and network, to recruit one senior nurse from each ICU with a good command in the Greek language to complete the questionnaire. Prior to the release pf the survey, senior nurses were contacted by phone by the Cypriot national coordinator herself. They were asked, before completing the questionnaire, to meet and collectively discuss the responses with the ICU interprofessional team involved in the assessment and treatment of dysphagia. Based on this, a questionnaire was completed by each ICU and expressed the everyday clinical practice in the particular ICU. The ICU teams involved nurses, intensivists, physiotherapists and SLP/SLTs, where available.

2.3. Data collection and instrument

We used the anonymous self-administered survey which was used in the international survey of Spronk et al. (2022) [

24]. At the beginning of the questionnaire, there was a cover letter describing the study and its objectives in detail. The 46-question survey contained five different types of questions: 7-point Likert scale, multiple-choice, checkboxes, matrix as well as open-ended questions that required short answers and it included:

2.3.1. Demographics

7 questions (5 multiple choice and 2 checkboxes) assessing the ICU demographics.

Domain 1: Current practice

16 items assessing current ICU practices on:

- (a)

PED management with questions (7 multiple choice, 3 checkboxes and 1 matrix) about the existing protocols for screening, methods used to confirm the presence of PED and responsibilities of every ICU team member for assessing PED.

- (b)

Prevention of aspiration pneumonia related to PED (2 matrix questions).

- (c)

PED treatment interventions (1 matrix, 1 checkbox and 1 multiple choice question).

2.3.2. Domain 2: Scope of the problem

10 questions (seven 7-point Likert scale and 3 multiple choice ones) were used to assess the awareness of PED and its consequences. Regarding Likert scale questions, five of them ranged from 1- Strongly disagree to 7- Strongly agree and two from 1- Strongly agree to 7- Strongly disagree.

2.3.3. Domain 3: Perceived best practice

13 questions (6 checkboxes, 4 open-ended and three 7-point Likert scale questions) assessed the perception of best practices in screening and treating PED. In this domain, two of Likert scale questions ranged from 1- Strongly disagree to 7- Strongly agree and one ranged from 1- Strongly agree to 7-Strongly disagree.

As described above, three out of 10 Likert scale questions were inverted, following the questionnaire creator's advice, to avoid response bias. Finally, the terms dysphagia, OD, and PED were used interchangeably in the questionnaire, as appropriate to the question.

2.3.4. Translation of the instrument

The questionnaire was translated from English to Greek and back-translated by two independent bilingual academics [

29]. To assess the content of the translated questionnaire, the survey was reviewed by an external panel of experts consisting of two academics with ICU experience for more than 10 years and two Ph.D. nursing students familiar with the Cypriot ICU context.

A Google Forms link to the survey, was emailed by the principal investigator to the participating ICUs senior nurses in June 2018. Only two email reminders were sent to non-responder nurses of four ICUs at a one-week intervals.

2.4. Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by the National Committee of Bioethics of Cyprus (EEBK/EP/ 2018.01.99). Submission of a completed questionnaire was considered as participation after informed consent. No intervention to patients was done during the study.

2.5. Data analysis

Google forms was used to collect data. The data were extracted in an Excel spreadsheet, quality tested, and analyzed. Data were summarized using descriptive statistics. Likert scale results are presented as means (M), medians, interquartile range (IQR), modal values and standard deviations (SD). Agreement with a specific statement in the questionnaire was defined as a score of 5–7 on a Likert-7 scale, while 4 was rated as neutral, and 1–3 was rated as disagreement. For the statistical analysis, the results of the three inverted Likert scale questions were reversed back (1 equals Strongly Disagree and 7 to Strongly Agree).

Categorical variables such as the questions regarding assessment methods were summarized as counts, and percentages.

The analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21. A non-parametric Spearman correlation used to assess the relationship between public and private ICU data and Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) used to draw the graphs.

3. Results

Fourteen ICUs across the Republic of Cyprus participated in the survey, with a response rate of 100% (14/14). Eight ICUs had a capacity of 5-9 beds, four had 10-14, and two 15-19. Eight ICUs were located in hospitals with a capacity of fewer than 200 beds and six in hospitals with 200-499 beds. 12 ICUs admitted patients with mixed medical and surgical problems, while 4 of them could also treat neurosurgical and 3 cardiothoracic patients. One ICU was a dedicated coronary unit and another a burn unit. Of the ICUs, five were located in private hospitals while 9 were in public ones. None of the ICUs had dedicated an SLP/SLT for the needs of their patients, 8 ICUs had access to an SLP/SLT upon request, and 6 didn’t have access at all (

Table 1). In all ICU interprofessional teams there was an intensivist and in those that had access to an SLP/SLT, he also took part in it.

3.1. Current practices on PED

3.1.1. PED management

3.1.1.1. Existing protocols and subgroups of patients screened

More than 85% (12 ICUs) of ICUs indicated that there was no standard protocol indicating which patients should be screened for PED.

Nine out of 14 ICU teams (64.2%) reported that the the percentage of patients screened for PED in their ICU was 0%, in 1 ICU (7.1%) was 25-50%, in 2 ICUs (14.2%) was 51-75% and in 1 ICU (7.1%) less than 25%. Screening for more than 75% was reported in 1 (7.1%) ICU only.

For patients who received a tracheostomy during their ICU admission, the routine PED screening was reported to be more than 75% in 6 (42.8%) ICUs, 25-50% in 3 (21.4%) ICUs, 51-75% in 1 (7.1%) and less than 25% also in 1 (7.1%). No screening for PED regarding the patients who received a tracheostomy during their ICU admission was reported in 3 (21.4%) ICUs.

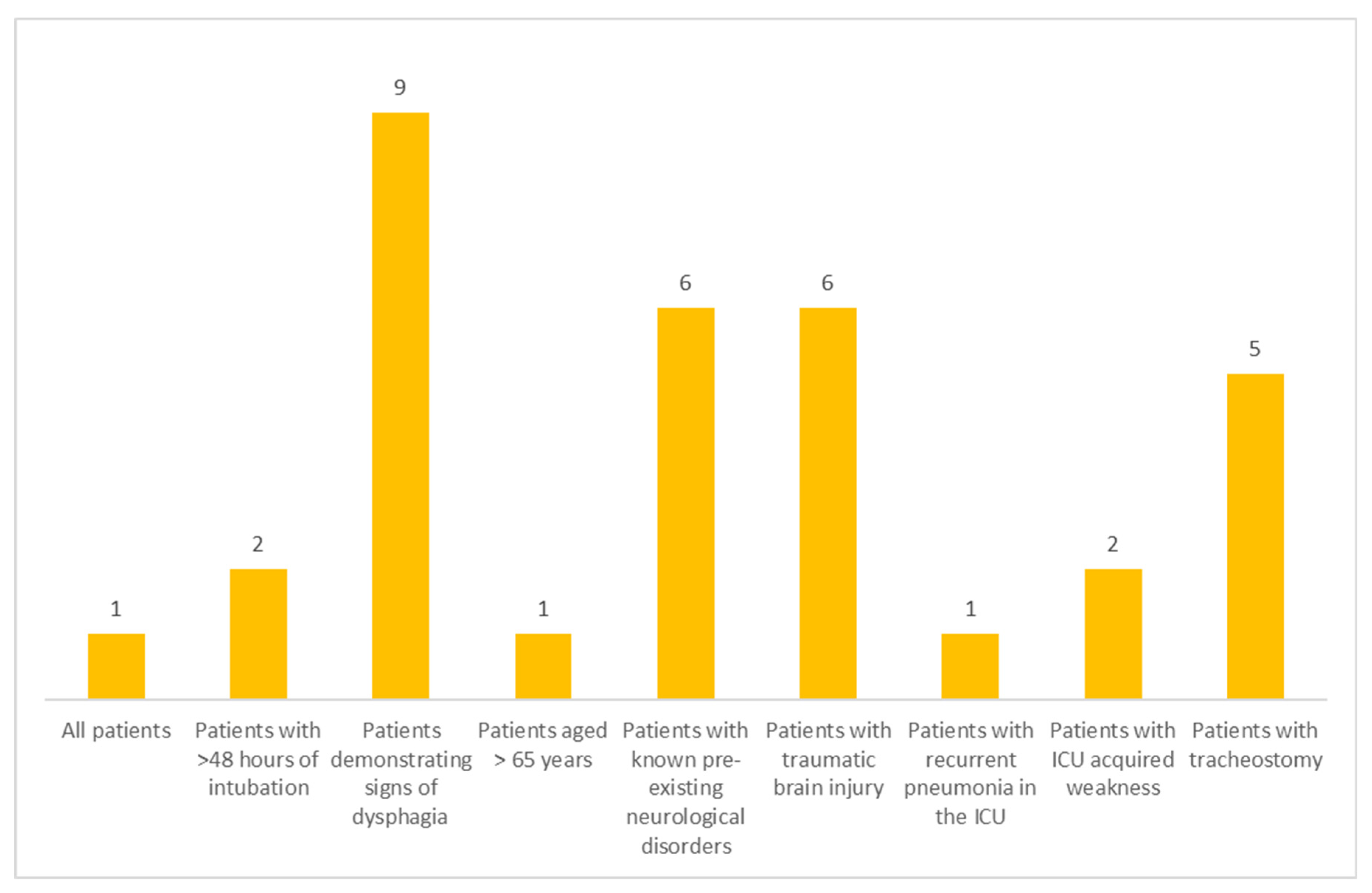

Screening for PED primarily took place for those patients who demonstrated signs of dysphagia, followed by patients with existing neurological disorders and, traumatic brain injury while patients with tracheostomy came third. Subgroups of patients routinely screened for dysphagia after their extubation are presented in

Figure 1.

3.1.1.2. Timing of screening

After ICU admission

Dysphagia screening on ICU admission was only reported by 1 unit (7.1%). One ICU team reported the time of screening to be between 3 and 7 days after admission, in 2 units (14.2%) screening took place within 24-48 hours after admission and 1 unit commented that they check for dysphagia only when it was noticed upon admission. No screening took place in 9 ICUs (64.2%).

After extubation

Regarding the first screening for PED, no screening took place in 3 ICUs (21.4%). Four ICU teams (28.5%) reported that screening happened on the day of extubation, and another 4 that this happened 3 to 7 days after extubation. In 1 ICU, the screening took place 24 to 48 hours post-extubation. Two ICUs (14.2%) commented that screening happened after extubation only if dysphagia was noticed.

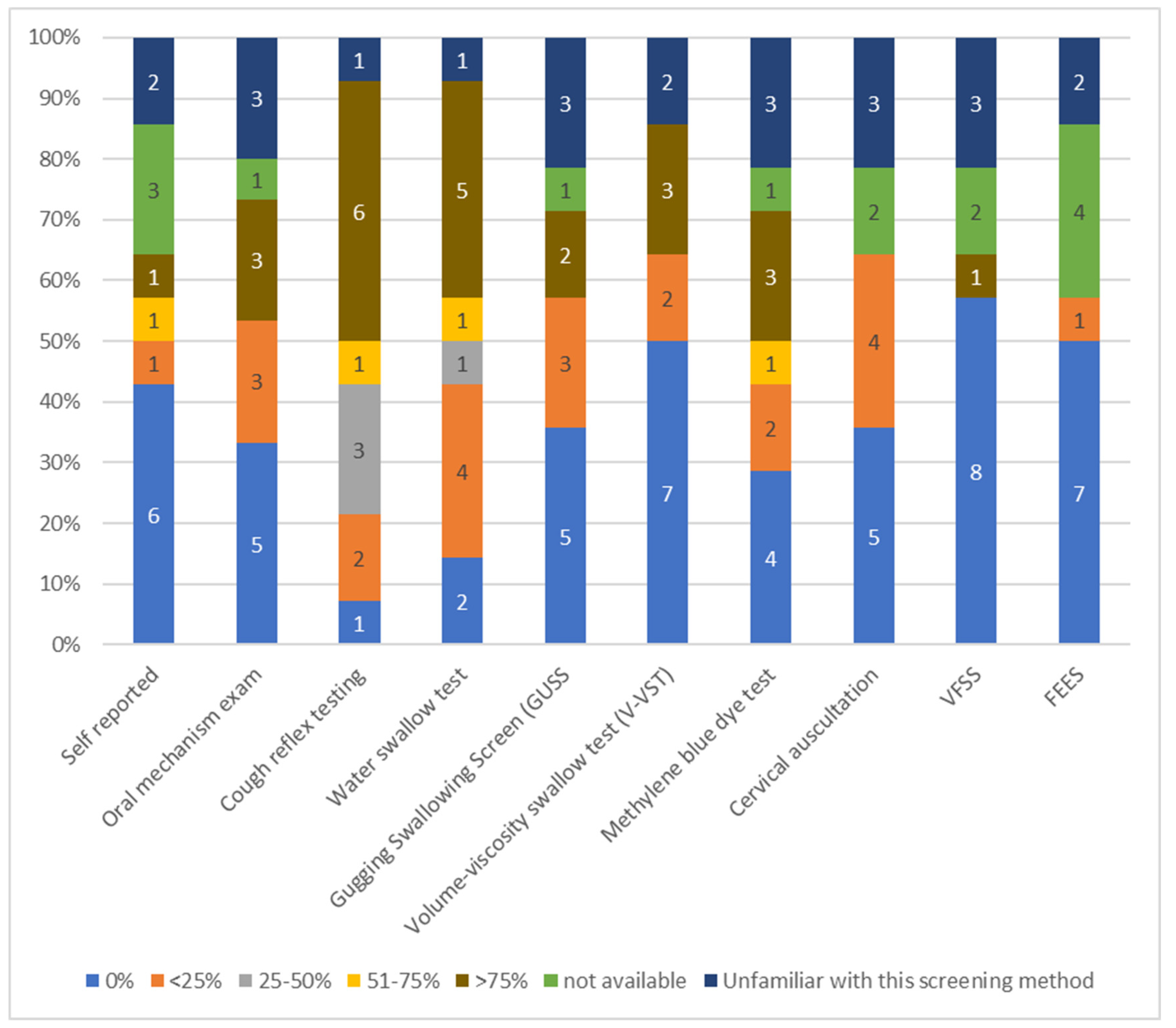

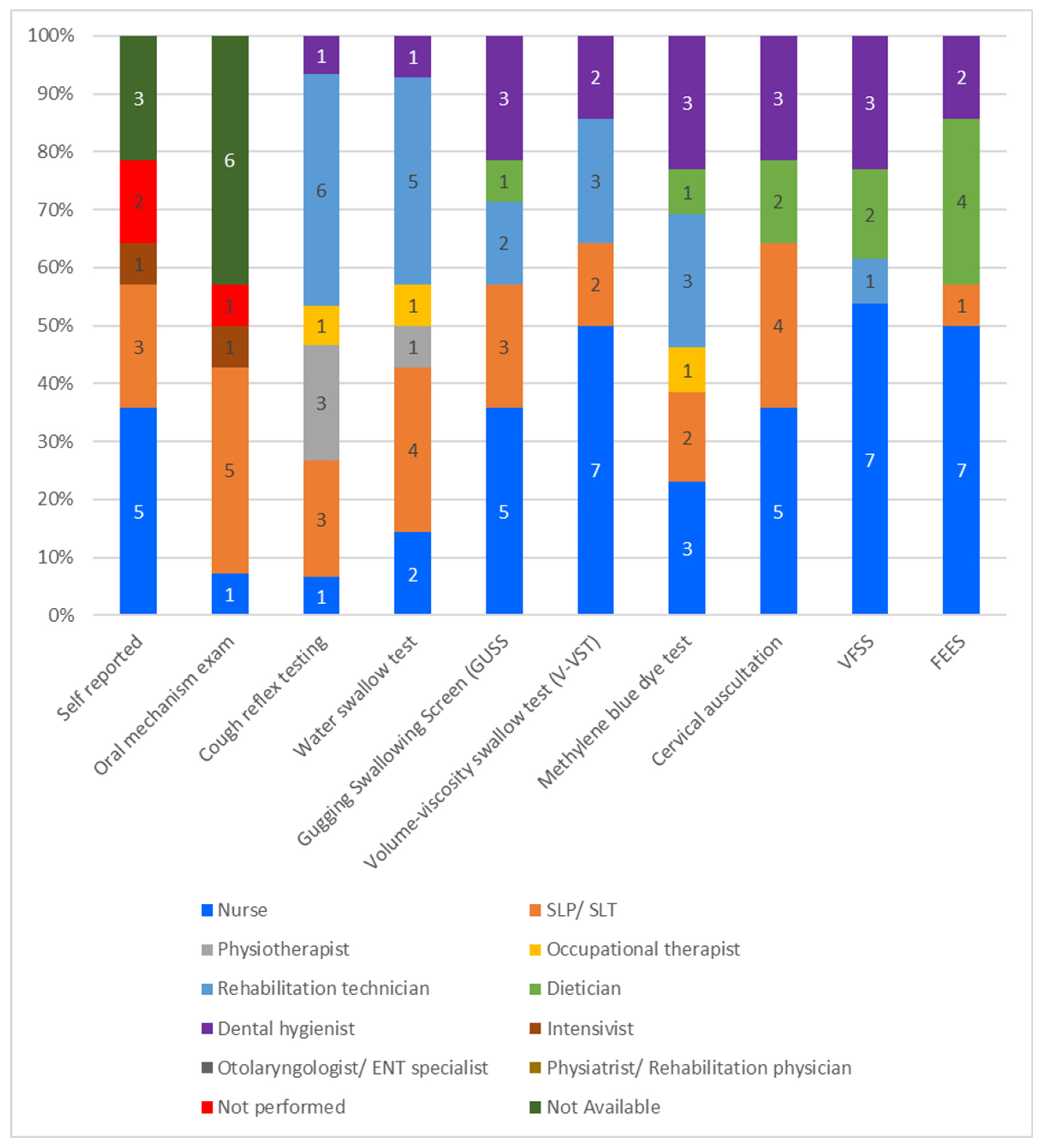

3.1.1.3. Methods used for PED assessment

Regarding the most commonly used method used in more than 75% of ICU patients to confirm the presence of PED, the cough reflex testing was chosen by 6 ICUs (42.8%), followed by the water swallow test (5 ICUs, 35%), while oral mechanism exam, volume–viscosity swallow test (V-VST), and methylene blue test reported in 3 ICU teams, respectively. videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS), flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES), and V-VST were not used at all in 7 ICUs (50%), the self-reported method was not used in 6 units, and oral mechanism exam as well as gugging swallowing screen (GUSS) were not used in 5 ICUs (35.7%), respectively. Three ICU teams reported that they were unfamiliar with VFSS, cervical auscultation, V-VST and oral mechanism exam. FEES was ranked the lowest among all methods since it was used only in 25% of patients by one ICU, and VFSS ranged second since it was used as assessing method in more than 75% of patients by only one ICU. The vast majority of the participants reported that FEES and VFSS were not used, were not available or the healthcare professionals were unfamiliar with them (

Figure 2).

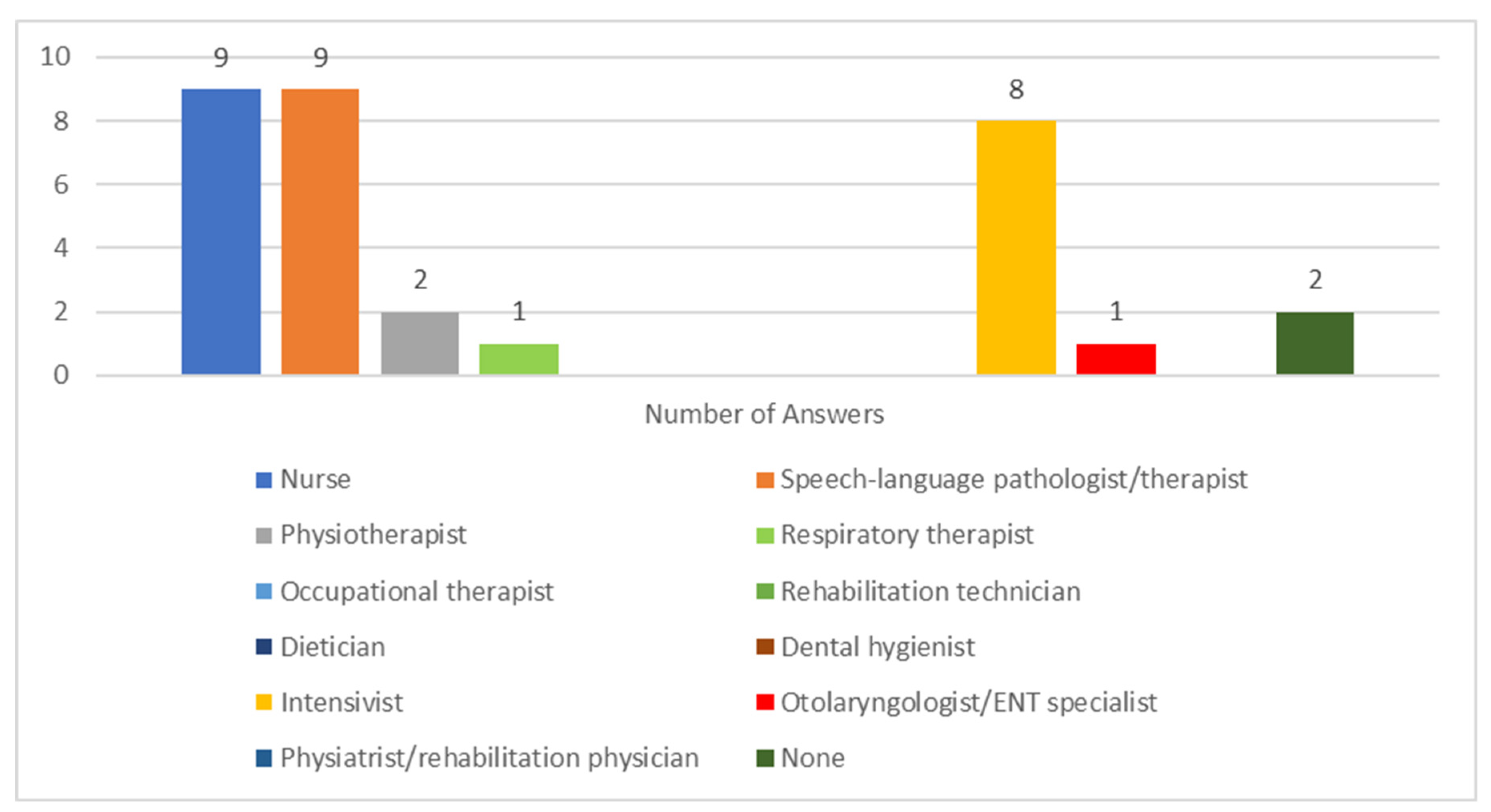

3.1.1.4. Responsibilities of ICU team members

In the majority of ICUs, nurses and intensivists were mostly responsible to assess PED as well as SLP/SLTs (

Figure 3). Eight ICU teams (57.1%) reported that, when an SLP/SLT was available, the percentage of patients consulted was <25%. The availability of an otolaryngologist/ ENT specialist in order to consult when PED was suspected was reported in 4 ICUs (28.6%), and the percentage of patients consulted was <25% in 3 ICUs (21.4%). Only one ICU team reported a proportion of patients otolaryngologist/ ENT specialist consulted of >75%.

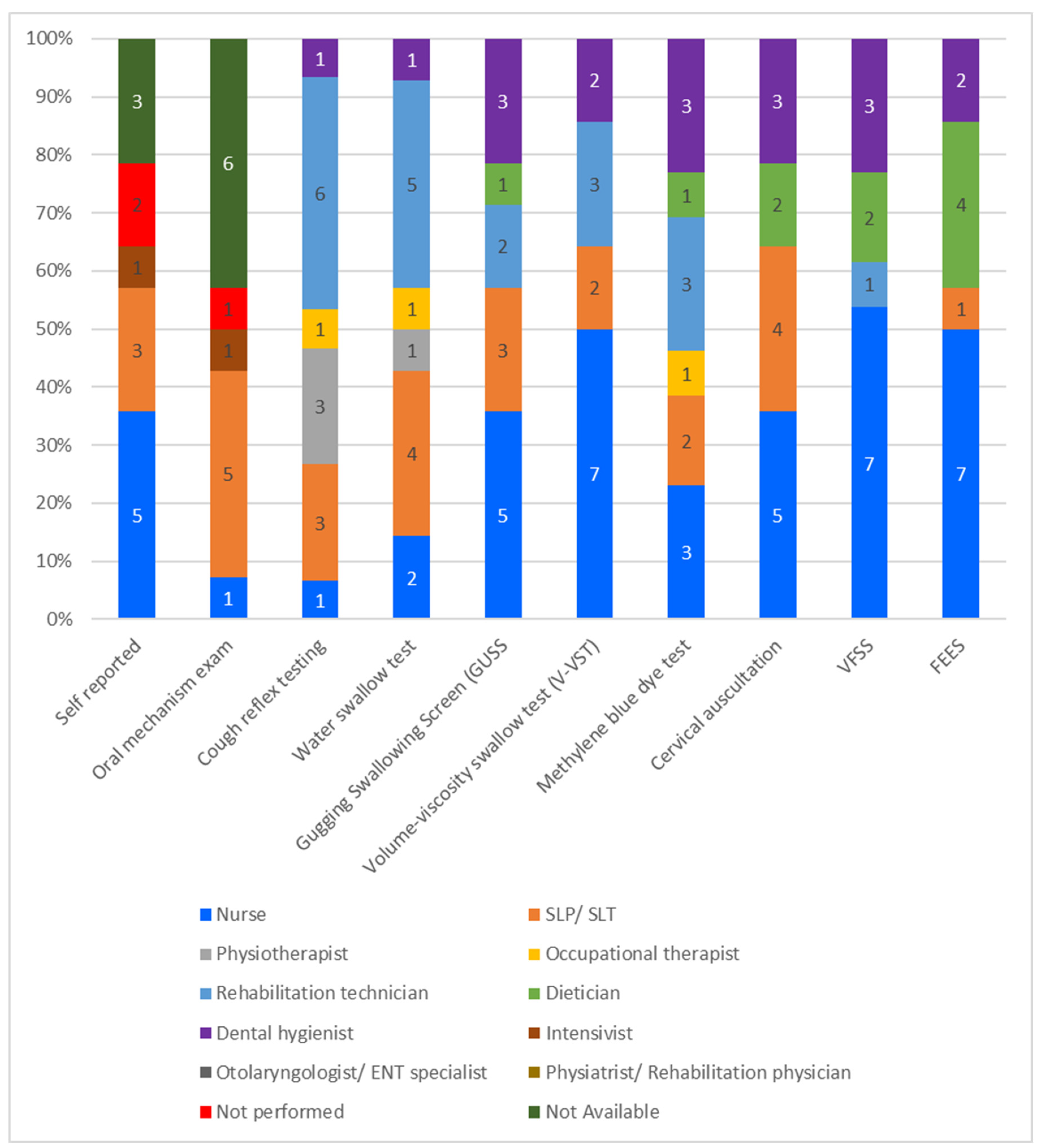

Figure 4 presents the responsibility of each ICU member in screening methods used for PED.

3.1.2. Prevention of aspiration pneumonia related to PED

3.1.2.1. Aspiration/ Aspiration pneumonia resulting from liquids/ solid food

Postural adjustment measures for the prevention of aspiration pneumonia were ranked as the most common interventions (11 ICUs, 78.6%), oral hygiene second most common (10 ICUs, 71.4%), delayed feeding as third (9 ICUs, 64.2%), and tracheostomy cuff deflation during meals as fourth (8 ICUs, 57.1%).

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) was the least used aspiration prevention method since the vast majority of ICU teams (7 ICUs, 50%) reported that usage was less than 25% of patients. 3 ICUs (21.4%) used PEG between 25-50% of patients, in one ICU it was not used, and in one the healthcare professionals were unfamiliar with the procedure. Measures taken to prevent aspiration/ aspiration pneumonia are listed in

Figure 5.

3.1.2.2. Aspiration pneumonia resulting from saliva production

The only saliva production interventions that were used in the ICUs of the study were per-os (<25% of patients in 3 ICUs, 25-50% in 1 ICU, >75%% in 2 ICUs) or intravenous (<25% of patients in 3 ICUs, 25-50% in 2 ICUs, >75% in 1 ICU) anticholinergics (e.g. glycopyrronium, atropine). Scopolamine patches, botulinum toxin type A and irradiation of the salivary gland procedures were not used.

3.1.3. Interventions to treat PED

The most commonly used interventions to treat PED were muscle strengthening exercises without swallowing and repetitive swallowing exercises/maneuvers with or without additional resistance followed by respiratory exercises. The remaining interventions, including muscle strengthening exercises using apps on a tablet/iPad, neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NEMS) of swallowing muscles, surface EMG (sEMG) biofeedback swallowing training and pharyngeal Electrical Stimulation (PES) were mostly not used or the personnel was unfamiliar with them (

Table 2).

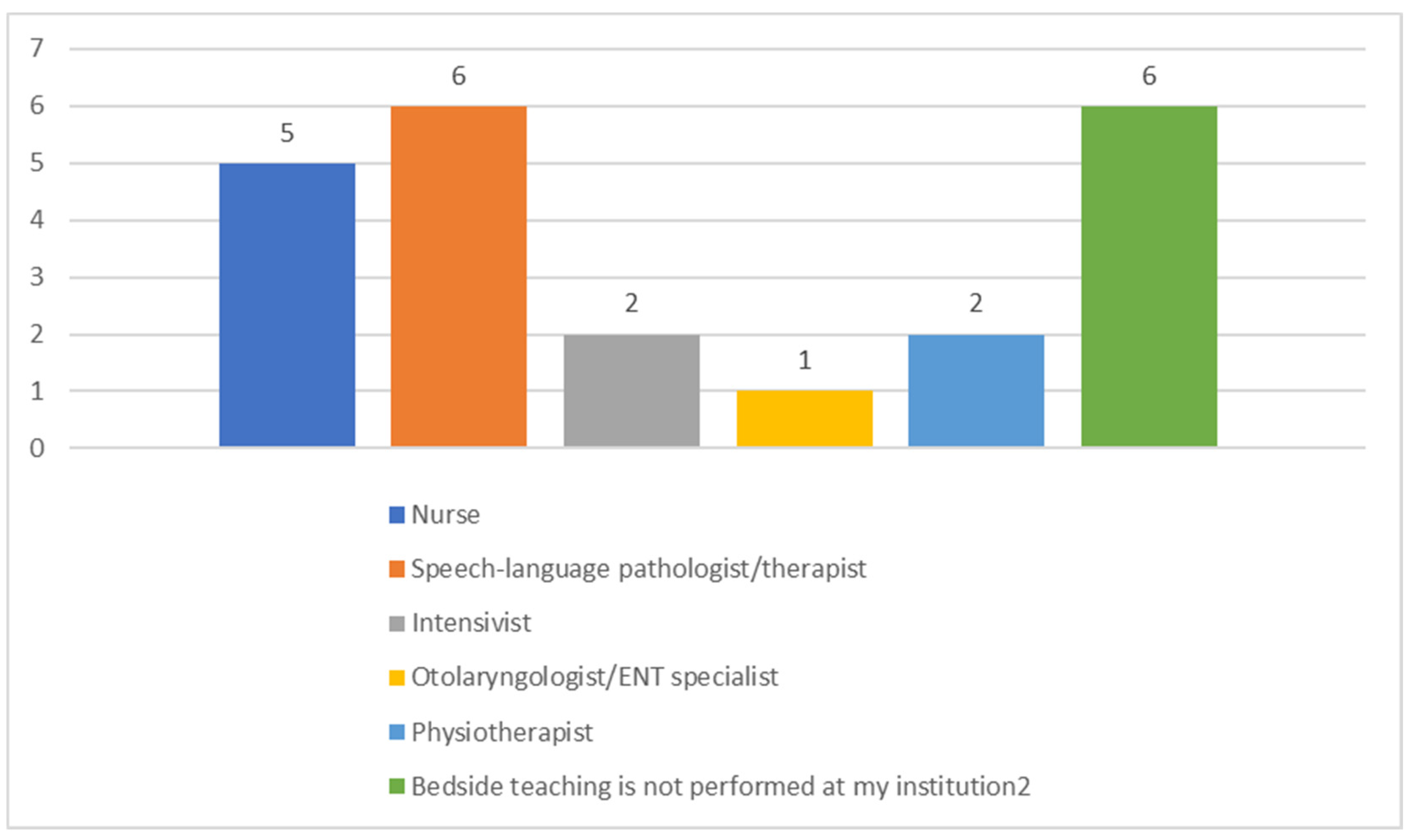

Regarding bedside swallow training, in the majority of ICUs, SLP/SLTs and nurses were identified as the team members who performed the bedside patient swallow training, whereas intensivists and physiotherapists follow. ENT was the member with the least bedside patient training. 6 ICU teams mentioned that bedside teaching was not performed at their unit (

Figure 6).

3.2. Scope of the problem

3.2.1. Awareness of PED incidence

6 ICUs (42.8%%) did not agree that PED was common in their unit, whereas 4 ICUs (28.5%) ICUs agreed. The remaining 4 ICUs gave a neutral answer [mean: 3.35; SD: 1.19, Median: 4, IQR: 3, Modal Value: 5 (6)]. 10 units (71.4%) agreed that PED was associated with the duration of intubation. 5 ICUs (35.7%) indicated that PED occurred in less than 25% of their ICU patients who remained intubated for more than 48 hours, while another 5 ICU teams estimated that it occurred in 25-50%, and one estimated that occurred in between 51-75%. On the contrary, 3 ICU teams (21.4%) estimated that none of their patients who remained intubated for >48 hours but less than 7 days developed PED. As per the estimation of how common PED was for patients who remained intubated for more than 7 days, 6 ICU teams (42.8%) estimated the incidence of PED as 25-50%, 4 estimated as less than 25%, while 3 ICU teams estimated it between 51 to 75%. One ICU team estimated 0% of PED in their patients who remained intubated for more than 7 days. For critically ill patients who received a tracheostomy during their hospitalization in ICU, 6 ICU teams estimated that PED occurred in 51-75% of those patients, 1 in >75%, four in 25 to 50%, two less than 25%, and one team estimated that no PED occurred.

3.2.2. Awareness of PED consequences

All ICUs agreed that PED delays patients' return to normal functioning and influences the need for long-term care. PED consequences are listed in

Table 3.

3.3. Perceived best practices on PED

3.3.1. Protocols and routinely screening

71.4% of ICUs [mean: 5.21; SD: 2.5; median: 7; IQR: 5; modal value: 7 (4)] agreed that a standard protocol or algorithm should be used for screening PED. 71.4% [mean: 5.14; SD: 1.87, median: 5.5; IQR: 3; modal value: 7 (4)] identified the need for routine PED screening before the discharge of patients with a length of ICU stay of more than 48hours and the same percentage [71.4%; mean: 5.35; SD: 1.39; median: 6; IQR: 2; modal value: 6 (5)] agreed that patients who remained intubated for more than 48 hours should be routinely screened for dysphagia.

3.3.2. Availability of screening and treating methods

Regarding their opinion about which screening method should be available for PED (

Table 4), ICUs chose all the possible answers as there was no limitation to the number of answers they could choose, as did in the next question regarding their opinion about which method should be available for the treatment of PED (

Table 5). The only answer that was not chosen in this question was the one stating that there is ‘No need for dysphagia-specific treatment, as dysphagia will disappear when the patient’s strength increases.

3.3.3. Barriers to standardized screening and treatment

More than 92% of ICUs (13/14) identified the lack of protocols regarding screening and treating of PED and specialized personnel as important barriers for the implementation of standardized screening and treatment. Additionally, they recognized the lack of knowledge and the lack of education on possible treatments of PED as extra barriers for standardized screening and treatment, respectively.

3.3.4. Facilitators to standardized screening and treatment

As regards to the most important facilitators to standardized screening and treatment, more than 85% (12 ICUS) chose the use of a standardized protocol, the availability of specially trained personnel and the knowledge and ability of the ICU members to identify and treat PED. Finally, the four open-type questions were not answered therefore they were not included in the analysis.

4. Discussion

We conducted a survey involving health care teams working in all ICUs in the republic of Cyprus to assess awareness of PED and its consequences, and to explore what the ICU teams perceived as best practices, as well as current approaches to PED assessment and treatment. It was part of DICE, a multi-center, international, online cross-sectional survey which aimed to provide evidence-based guidance for the implementation of OD protocols [

24]. Our results showed that a few ICU teams in Cyprus were aware of PED incidence in their units and most of them were aware of PED complications. Despite recognition of the need for evidence-based protocols as best practices for the screening and treatment of PED by most ICUs, very few routinely screened for dysphagia using appropriate methods. Similarly, protocols to guide PED management were not used in most ICUs, and effective treatments were limited by the lack of SLP/SPTs and/or knowledge gaps in ICU interprofessional teams.

4.1. Perceived best and current practices on PED

While most of the ICU teams in Cyprus identified the need for routine PED screening before the discharge of patients with a length of ICU stay more than 48 hours and agreed that a standard protocol or algorithm should be used for screening PED, the majority of them reported the absence of any standardized dysphagia assessment protocol. The absence of an assessment protocol and screening procedures in the ICUs is commonly reported by most [

30,

31,

32,

33]. The lack of international guidelines for the management of PED combined with these unsettling findings from studies across the world imply that dysphagia might be undiagnosed and untreated and, as such, result in negative consequences for the critically ill patients’ health and [

10,

11]. These findings point to an urgent need for the development of guidelines and the implementation of educational programs for ICU teams in order to equip staff with new skills and procedures for safe clinical practice.

For the limited number of ICU teams which reported screening for PED, the most frequent screening method was the cough reflex testing, followed by the water swallow test. The current practice is controversial in terms of accuracy in detecting PED and may contribute to silent aspiration and consequently pneumonia [

24,

34]. This suggests that PED in patients who underwent the water swallow test may not be detected, thus it remained untreated. The water swallow test was most commonly reported by other studies whereas high accuracy detection methods such as FEES or VFSS were rarely used both in Cyprus as well as in other countries [

24,

30,

31,

32,

35] may be for reasons associated with the availability of the specific technology and trained SLP/SLTs [

24].

In the majority of ICUs in our study, nurses and intensivists were responsible to assess PED as well as SLP/SLTs whereas in Switzerland nurses had the lead in the initial ICU dysphagia screening [

9] and physicians in Germany [

32]. None of the ICU teams that participated in our survey reported a dedicated SLP/SLT for their patient's needs while approximately half of them reported a lack of SLP/SLT availability even as an external partner. In case there was an SLP/SLT available on request, the percentage of patients consulted was less than 25%. However, although the availability and collaboration with an SLP/SPT in the ICU can positively affect ICU-related complications due to PED [

36], the lack of SLP/SLTs involved in ICU patient care is a common practice across the world [

37]. Interestingly, in some countries SLPs do not receive ICU-specific training, which may explain the tradition for lack of ICU-dedicated SLPs [

38]. In the absence of SLP/ SLTs, PED identification has traditionally been performed by other healthcare professionals, mainly nurses. Nevertheless, nurse-performed dysphagia screening is considered to be feasible [

23] safe [

39] and superior to no screening in terms of patient outcome [

40]. Until a dedicated SLP/SLT for PED screening and treatment becomes available for all ICUs, the empowerment of nurses through education and formalized procedures can contribute to the early identification of high-risk individuals for dysphagia and optimize their care.

Postural adjustment, as well as oral hygiene, were the most widely used methods to decrease the risk of aspiration after suspected or confirmed PED in our study. Oral hygiene can reduce the bacterial colonization of the oropharyngeal cavity and can contribute to the efforts to prevent aspiration pneumonia [

41,

42]. It is also used in intubated patients for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia, where the aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions is possible irrespective of the presence of dysphagia [

43]. Postural adjustment has been proven to promote swallowing in patients with confirmed or suspected dysphagia by affecting bolus flow and speed, especially when the patient has been placed in a sitting position [

44].

Muscle strengthening exercises without swallowing, repetitive swallowing exercises/maneuvers with or without additional resistance have been identified as the most widely used interventions to treat PED in our survey. These exercises are proven to promote muscle strengthening [

45,

46,

47] and consequently swallowing, yet they are only used by a limited number of participating ICUs.

4.2. Awareness of PED incidence and consequences

One fourth of the participating ICU teams reported that PED was common amongst hospitalized ICU patients. Our results were very similar to the findings reported by the Swiss survey of dysphagia care [

35], the MAD-ICU study in Germany [

32], and a Dutch national ICU survey [

30]. However, the ICU team awareness of PED in our study was lower than the frequency of OD occurrence reported in the DICE international study (47%) [

24]. Many respondents in our survey thought that the duration of intubation and the presence of tracheostomy seemed to increase the PED occurrence which has also been demonstrated in the literature [

9,

48,

49]. 42.8% of ICU teams estimated the incidence of PED as 25-50% for patients who remained intubated for more than 7 days while 21.4% of ICU teams between 51 to 75% which was less than the estimation of the DICE study (67%) [

24]. The variations in findings concerning awareness of PED and its consequences might reflect differences in the composition of the ICU team across countries, the availability and the level of interdisciplinary collaboration with speech therapists. A prospective observational study is needed in a way to precisely identify the proportion of dysphagia in ICUs as well as the factors associated with its occurrence.

The incidence of PED in patients with a tracheostomy was estimated to be 51–75% by most respondents in our study with 25–50% being the 2nd most frequent estimate. This is in accordance with the Dutch study [

30] with cohorts including non-neurologic critically ill patients with a tracheostomy [

50] as well as neurologic patients [

51,

52].

The vast majority of the participating ICUs in our study agreed that the duration of ICU stay was associated with increased PED occurrence. Yet, the reasons for the prolonged ICU stay were not known since no scoring system was used in the current study. However, there is evidence that ICU patients' disease severity in the Republic of Cyprus is high [

43] and as patients with increased disease severity will probably stay longer in the ICU and have a longer duration of intubation than others with less severe conditions [

53,

54], thus, they are more likely to develop PED [

54]. Additionally, it is well evidenced that PED patients have a significantly longer LOS in hospitals in comparison to patients with normal swallowing [

55,

56,

57], a finding that more than two-thirds of the participating ICUs in our study agreed with. The ICU teams in Cyprus seemed more aware of the risk of dysphagia to increase ICU and hospital LOS compared to the findings of the DICE study [

24]. Yet, it remains unclear whether PED resulted in the increased LOS or, whether the increased LOS resulted in PED in our participants' reports. A prospective observational study could help answer this question.

The functional status of a person is defined as the ability to carry out daily living abilities including eating [

58]. Since PED has the potential to compromise eating ability in hospitalized patients, it can delay the return of a patient to pre-hospitalization functioning status, a finding that was also reported by all the participating ICUs of the study. Additionally, all participants agreed that patients who present with PED may need long-term care in comparison with patients without.

In our study, almost all of the participating ICUs perceived that ICU readmission was associated with PED. Although, the association seems very possible it has not been positively correlated among patients with clinically significant PED compared to those without [

59]. Yet, the study reported certain limitations mostly associated with sampling methodology and size.

The current survey sought to map the state of post-extubation dysphagia management in critical care in the Republic of Cyprus, however, certain limitations must be acknowledged. One limitation lies in the fact that the results were based on the perceptions of ICU teams around the incidence, risks and management of dysphagia in their units. We did not collect data on the actual incidence and management of post-extubation dysphagia, as this could only be done prospectively due to lack of consistent documentation. Another limitation may be related to response bias as the national study coordinator was not present during the completion of the questionnaire. However, senior nurses who completed the questionnaire showed the completed questionnaires to each of the ICU team member to verify their answers. Lastly, the translated version in the Greek language of the original questionnaire has not been tested for psychometrics properties specifically, although the original version had been validated [

24].

5. Conclusions

According to the results of our study, ICU teams in Cyprus demonstrated low levels of awareness and knowledge regarding PED. Although perceived best practices were identified, there were no established protocols for the screening and treatment of dysphagia. As a consequence of high disease severity of ICU patients in the Republic of Cyprus [

43], longer ICU hospitalizations are expected which in turn associate with the occurrence of dysphagia [

43,

54,

55]. What is worse, the recent Covid-19 pandemic increased the number of patients requiring ICU admission while limiting practitioners’ time and resources to care for all [

60].

The findings for PED screening and treatment in Cyprus in combination with those by other countries are unsettling for the care of critically ill patients in ICU. Hopefully, mapping the current situation will add to the knowledge base required to produce international guidelines for PED management. Importantly, the severe clinical complications associated with PED in ICU patients [

11,

15,

61,

62] dictate that a comprehensive unit-based dysphagia education program must be urgently implemented to positively affect the uptake of therapeutic interventions and improve the quality of care provided. The interdisciplinary collaboration between nurses, intensivists and SLP/ SLTs is a prerequisite for the success of any of these initiatives.

Author Contributions

M.M. participated in ethical approval, recruitment, data collection, data interpretation and drafted the manuscript; S.I. did the data analysis, data interpretation and drafted the manuscript; M.K. (Maria Kyranou) participated in writing and in data interpretation; K.I. participated in writing and critically reviewed the final manuscript; S.P. and M.K. (Maria Kalafati) critically reviewed the final manuscript; E.P. participated in data analysis, data interpretation, in writing the manuscript and critically reviewed the final manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Cyprus University of Technology (internal funding/ research activity 3/319). The original study (DICE) was partially funded by the Gelre Hospitals science fund (Grant 2018-012).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was reviewed and approved by the National Committee of Bioethics of Cyprus (EEBK/EP/ 2018.01.99).

Informed Consent Statement

The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The research team would like to thank all ICU teams who participate in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Suntrup-Krueger, S.; Muhle, P.; Kampe, I.; Egidi, P.; Ruck, T.; Lenze, F.; Jungheim, M.; Gminski, R.; Labeit, B.; Claus, I.; Warnecke, T.; Gross, J.; Dziewas, R. Effect of capsaicinoids on neurophysiological, biochemical, and mechanical parameters of swallowing function. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 1360–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Jones, C.A.; Colletti, C.M.; Ding, M.C. Post-stroke Dysphagia: Recent insights and unanswered questions. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2020, 20, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuni, I.; Otsubo, Y.; Ebihara, S. Molecular and neural mechanism of dysphagia due to cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 7033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabré, M.; Almirall, J.; Clavé, P. Aspiration pneumonia: management in Spain. Eur Geriatr Med 2011, 2, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.A.; Krishnaswami, S.; Steger, E.; Conover, E.; Vaezi, M.F.; Ciucci, M.R.; Francis, D.O. Economic and survival burden of dysphagia among inpatients in the United States. Dis esophagus Off J Int Soc Dis Esophagus 2018, 31, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kertscher, B.; Speyer, R.; Fong, E.; Georgiou, A.M.; Smith, M. Prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in the Netherlands: A telephone survey. Dysphagia 2015, 30, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajati, F.; Ahmadi, N.; Naghibzadeh, Z.A.; Kazeminia, M. The global prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in different populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Transl Med 2022, 20, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuercher, P.; Moret, C.S.; Dziewas, R.; Schefold, J.C. Dysphagia in the intensive care unit: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and clinical management. Crit Care 2019, 23, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoretz, S.A.; Flowers, H.L.; Martino, R. The incidence of dysphagia following endotracheal intubation: a systematic review. Chest 2010, 137, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schefold, J.C.; Berger, D.; Zürcher, P.; Lensch, M.; Perren, A.; Jakob, S.M.; Parviainen, I.; Takala, J. Dysphagia in mechanically ventilated ICU patients (Dynamics): A prospective observational trial. Crit Care Med 2017, 45, 2061–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, M.B.; Huang, M.; Shanholtz, C.; Mendez-Tellez, P.A.; Palmer, J.B.; Colantuoni, E.; Needham, D.M. Recovery from dysphagia symptoms after oral endotracheal intubation in acute respiratory distress syndrome survivors. A 5-Year longitudinal study. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017, 14, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, G.C.; Sassi, F.C.; Zambom, L.S.; de Andrade, C.R.F. Correlation between the severity of critically ill patients and clinical predictors of bronchial aspiration. J Bras Pneumol 2016, 42, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.; Trapl, M. Development of a modified swallowing screening tool to manage post-extubation dysphagia. Nurs Crit Care 2018, 23, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macht, M.; Wimbish, T.; Clark, B.J.; Benson, A.B.; Burnham, E.L.; Williams, A.; Moss, M. Postextubation dysphagia is persistent and associated with poor outcomes in survivors of critical illness. Crit Care 2011, 15, R231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuercher, P.; Moser, M.; Waskowski, J.; Pfortmueller, C.A.; Schefold, J.C. Dysphagia post-extubation affects long-term mortality in mixed adult ICU patients-Data from a large prospective observational study with systematic dysphagia screening. Crit care Explor 2022, 4, e0714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attrill, S.; White, S.; Murray, J.; Hammond, S.; Doeltgen, S. Impact of oropharyngeal dysphagia on healthcare cost and length of stay in hospital: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2018, 18, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielske, J.; Bohne, S.; Brunkhorst, F.M.; Axer, H.; Guntinas-Lichius, O. Acute and long-term dysphagia in critically ill patients with severe sepsis: results of a prospective controlled observational study. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 2014, 271, 3085–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongo, T.; Yumoto, T.; Naito, H.; Fujiwara, T.; Kondo, J.; Nozaki, S.; Nakao, A. Frequency, associated factors, and associated outcomes of dysphagia following sepsis. Aust Crit Care 2022, S1036-7314(22)00089-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, M.B.; González-Fernández, M.; Mendez-Tellez, P.A.; Shanholtz, C.; Palmer, J.B.; Needham, D.M. Factors associated with swallowing assessment after oral endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation for acute lung injury. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014, 11, 1545–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, E.B.; Chao, T.N. Dysphagia and swallowing disorders. Med Clin North Am 2021, 105, 939–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denk-Linnert, D.M.; Farneti, D.; Nawka, T.; Am Zehnhoff-Dinnesen, A.; Moerman, M.; Zorowka, P.; Farahat, M.; Schindler, A.; Geneid, A. Position statement of the Union of European Phoniatricians (UEP): Fees and phoniatricians’ role in multidisciplinary and multiprofessional dysphagia management team. Dysphagia 2023, 38, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omura, K.; Komine, A.; Yanagigawa, M.; Chiba, N.; Osada, M. Frequency and outcome of post-extubation dysphagia using nurse-performed swallowing screening protocol. Nurs Crit Care 2019, 24, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spronk, P.E.; Spronk, L.E.J.; Egerod, I.; McGaughey, J.; McRae, J.; Rose, L.; Brodsky, M.B.; DICE study investigators. Dysphagia in Intensive Care Evaluation (DICE): An international cross-sectional survey. Dysphagia 2022, 37, 1451–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollinghurst, J.; Smithard, D.G. Identifying dysphagia and demographic associations in older adults using electronic health records: A national longitudinal observational study in Wales (United Kingdom) 2008–2018. Dysphagia 2022, 37, 1612–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smithard, D.G. Dysphagia: A Geriatric Giant? Med Clin Rev 2016, 2, 5. Available online: https://medical-clinical-reviews.imedpub.com/dysphagia-a-geriatric-giant.php?aid=8373 (accessed on 16 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Hu, A. June is national dysphagia awareness month. Ear Nose Throat J 2017, 96, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STROBE - Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology. Available online: https://www.strobe-statement.org/ (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Snippenburg, W.; Kröner, A.; Flim, M.; Hofhuis, J.; Buise, M.; Hemler, R.; Spronk, P. Awareness and management of dysphagia in Dutch intensive care units: A nationwide survey. Dysphagia 2019, 34, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macht, M.; Wimbish, T.; Clark, B.J.; Benson, A.B.; Burnham, E.L.; Williams, A.; Moss, M. Diagnosis and treatment of post-extubation dysphagia: results from a national survey. J Crit Care 2012, 27, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, T.; Dünser, M.; Citerio, G.; Koköfer, A.; Dziewas, R. Are intensive care physicians aware of dysphagia? The MADICU survey results. Intensive Care Med 2018, 44, 973–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, M.B.; Nollet, J.L.; Spronk, P.E.; González-Fernández, M. Prevalence, pathophysiology, diagnostic modalities, and treatment options for dysphagia in critically ill patients. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2020, 99, 1164–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodsky, M.B.; Suiter, D.M.; González-Fernández, M.; Michtalik, H.J.; Frymark, T.B.; Venediktov, R.; Schooling, T. Screening accuracy for aspiration using bedside water swallow tests: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 2016, 150, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuercher, P.; Moret, C.; Schefold, J.C. Dysphagia in the intensive care unit in Switzerland (DICE) - results of a national survey on the current standard of care. Swiss Med Wkly 2019, 149, w20111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, J.; Montgomery, E.; Garstang, Z.; Cleary, E. The role of speech and language therapists in the intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Soc 2020, 21, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, S.; Mills, C.; Walshe, M. Perspectives on speech and language pathology practices and service provision in adult critical care settings in Ireland and international settings: A cross-sectional survey. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 2023, 25, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinal, L.A.; Freeman-Sanderson, A.; Togher, L. The speech pathology workforce in intensive care units: Results from a national survey. Aust Crit Care 2020, 33, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichero, J.A.; Heaton, S.; Bassett, L. Triaging dysphagia: nurse screening for dysphagia in an acute hospital. J Clin Nurs 2009, 18, 1649–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- See, K.C.; Peng, S.Y.; Phua, J.; Sum, C.L.; Concepcion, J. Nurse-performed screening for postextubation dysphagia: A retrospective cohort study in critically ill medical patients. Crit Care 2016, 20, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seedat, J.; Penn, C. Implementing oral care to reduce aspiration pneumonia amongst patients with dysphagia in a South African setting. S Afr J Commun Disord 2016, 63, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneyama, T.; Yoshida, M.; Ohrui, T.; Mukaiyama, H.; Okamoto, H.; Hoshiba, K.; Ihara, S.; Yanagisawa, S.; Ariumi, S.; Morita, T.; Mizuno, Y.; Ohsawa, T.; Akagawa, Y.; Hashimoto, K.; Sasaki, H. Oral care reduces pneumonia in older patients in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002, 50, 430–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordanou, S.; Papathanassoglou, E.; Middleton, N.; Palazis, L.; Timiliotou-Matsentidou, C.; Raftopoulos, V. Device-associated health care-associated infections: The effectiveness of a 3-year prevention and control program in the Republic of Cyprus. Nurs Crit Care 2020, 27, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghadir, A.H.; Zafar, H.; Al-Eisa, E.S.; Iqbal, Z.A. Effect of posture on swallowing. Afr Health Sci 2017, 17, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Zhang, H.J. Effects of chin tuck against resistance exercise versus Shaker exercise on dysphagia and psychological state after cerebral infarction. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2017, 53, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; An, D.H.; Oh, D.H.; Chang, M.Y. Effect of chin tuck against resistance exercise on patients with dysphagia following stroke: A randomized pilot study. NeuroRehabilitation 2018, 42, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.S.; Hwang, N.K. Chin tuck against resistance exercise for dysphagia rehabilitation: A systematic review. J Oral Rehabil 2021, 48, 968–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassi, F.C.; Medeiros, G.C.; Zambon, L.S.; Zilberstein, B.; Andrade, C.R.F. Evaluation and classification of post-extubation dysphagia in critically ill patients. Rev Col Bras Cir 2018, 45, e1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, M.B.; Gellar, J.E.; Dinglas, V.D.; Colantuoni, E.; Mendez-Tellez, P.A.; Shanholtz, C.; Palmer, J.B.; Needham, D.M. Duration of oral endotracheal intubation is associated with dysphagia symptoms in acute lung injury patients. J Crit Care 2014, 29, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, M.B.; Levy, M.J.; Jedlanek, E.; Pandian, V.; Blackford, B.; Price, C.; Cole, G.; Hillel, A.T.; Best, S.R.; Akst, L.M. Laryngeal injury and upper airway symptoms after oral endotracheal intubation with mechanical ventilation during critical care: A systematic review. Crit Care Med 2018, 46, 2010–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousou, J.A.; Tighe, D.A.; Garb, J.L.; Krasner, H.; Engelman, R.M.; Flack, J.E.; Deaton, D.W. Risk of dysphagia after transesophageal echocardiography during cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg 2000, 69, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macht, M.; Wimbish, T.; Bodine, C.; Moss, M. ICU-acquired swallowing disorders. Crit Care Med 2013, 41, 2396–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naved, S.A.; Siddiqui, S.; Khan, F.H. APACHE-II score correlation with mortality and length of stay in an intensive care unit. J Coll Physicians Surg Pakistan 2011, 21, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.; Song, Y.; Dong, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Yu, L.; Gao, L.; Shi, Y. Risk score for predicting dysphagia in patients after neurosurgery: A prospective observational trial. Front Neurol 2021, 12, 605687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melgaard, D.; Rodrigo-Domingo, M.; Mørch, M.M. The prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in acute geriatric patients. Geriatr (Basel) 2018, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, H.; Yoshimura, Y.; Ishizaki, N.; Ueno, T. Dysphagia is associated with functional decline during acute-care hospitalization of older patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2017, 17, 1610–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, M.D.; Modlinski, R.M.; Poulsen, S.H.; Rosenvinge, P.M.; Rasmussen, H.H.; Holst, M. Prevalence of signs of dysphagia and associated risk factors in geriatric patients admitted to an acute medical unit. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2021, 41, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCVHS. National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics: Classifying and Reporting Functional Status Subcommittee on Populations National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics (NCVHS) CLASSIFYING AND REPORTING FUNCTIONAL STATUS. Available online: https://www.ncvhs.hhs.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/010617rp.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Regala, M.; Marvin, S.; Ehlenbach, W.J. Association between post-extubation dysphagia and long-term mortality among critically ill older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019, 67, 1895–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anesi, G.L.; Kerlin, M.P. The impact of resource limitations on care delivery and outcomes: routine variation, the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, and persistent shortage. Curr Opin Crit Care 2021, 27, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, K.W.; Yu, G.P.; Schaefer, S.D. Consequence of dysphagia in the hospitalized patient: impact on prognosis and hospital resources. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010, 136, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlow, J.H.; Berenholtz, S.M.; Garrett, E.; Dorman, T.; Pronovost, P.J. Epidemiology and impact of aspiration pneumonia in patients undergoing surgery in Maryland, 1999-2000. Crit Care Med 2003, 31, 1930–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).