Submitted:

06 June 2023

Posted:

07 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Sample Collection

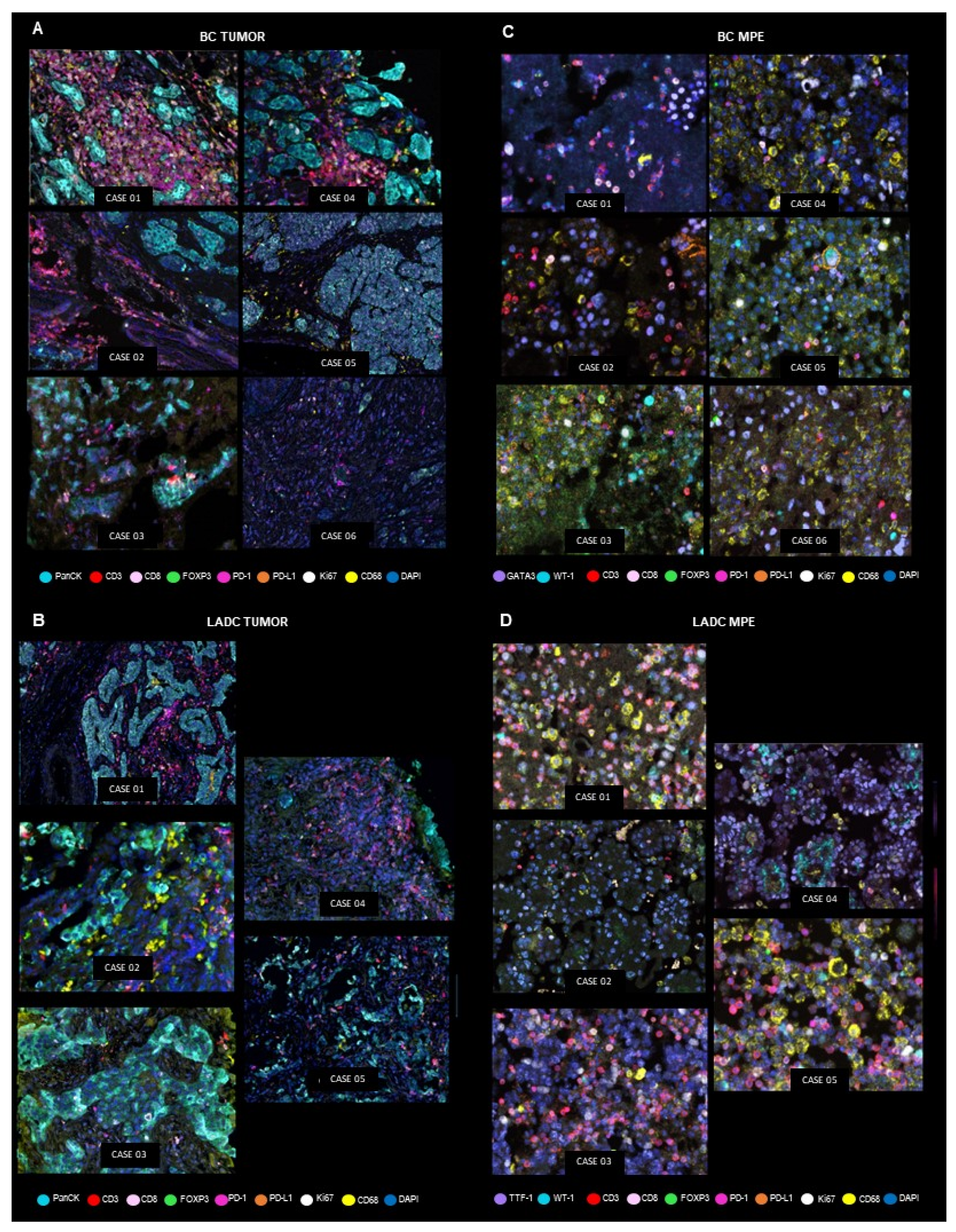

mIF samples

Selection of Representative Areas and Digital Image Analysis

Clinical Information

Statistical Analysis

Data Availability

3. Results

Patient Characteristics

Malignant Cells’ Overall PD-L1 and Ki67 Expression

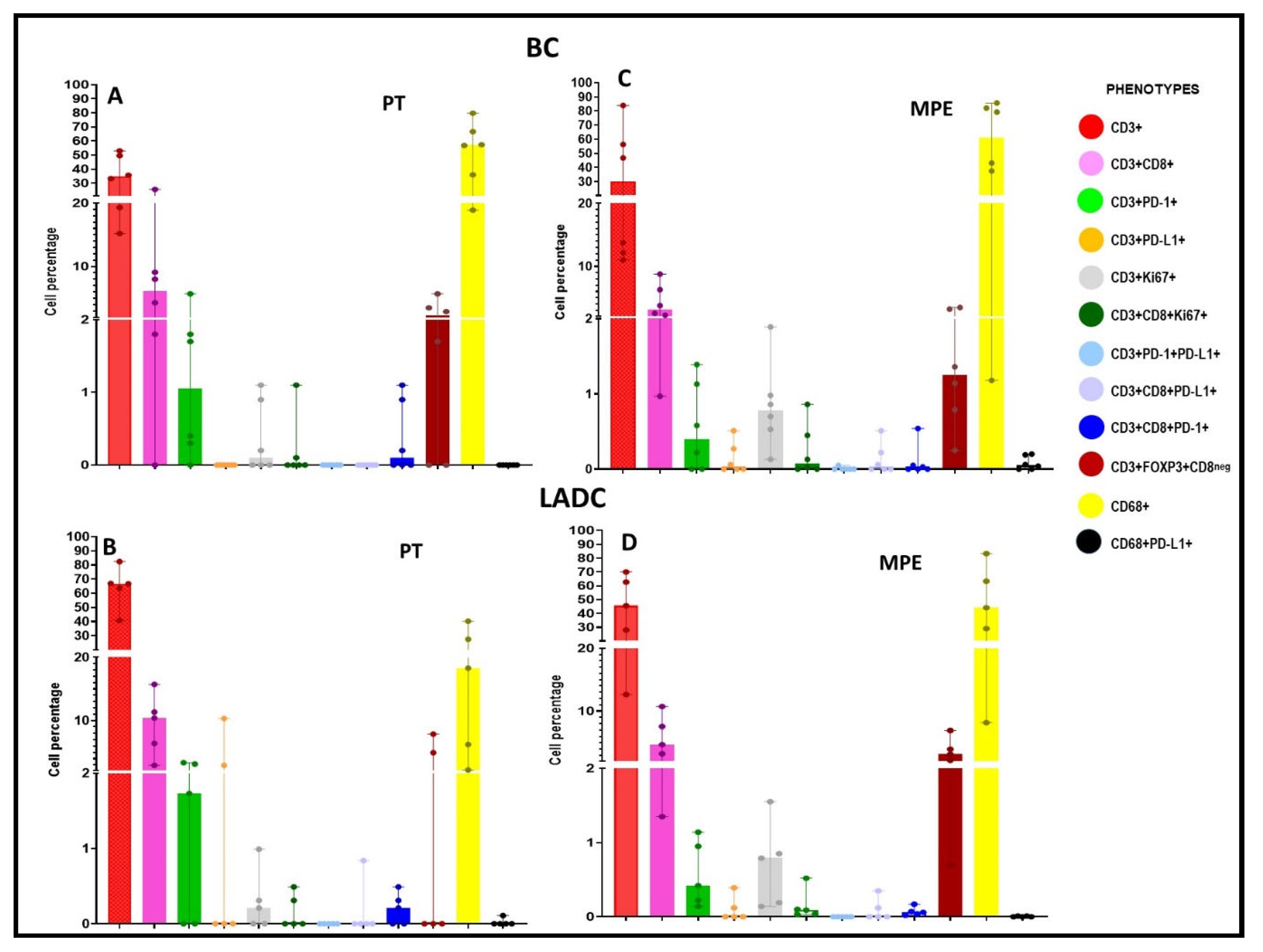

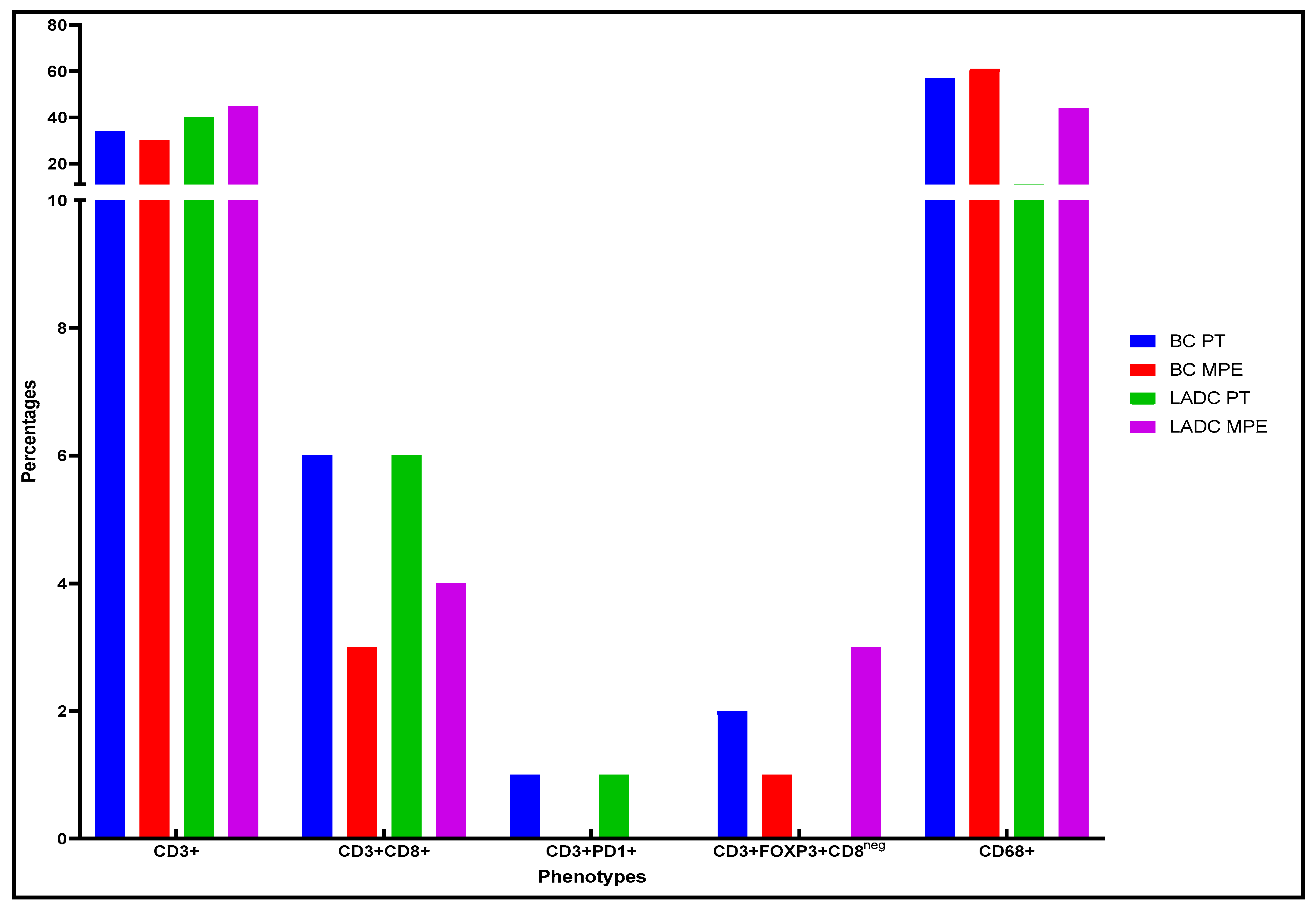

Characterization of the Tumor Microenvironment and the Immune-Cell Phenotypes of PTs and Their Paired MPEs

LADC Samples

BC Samples

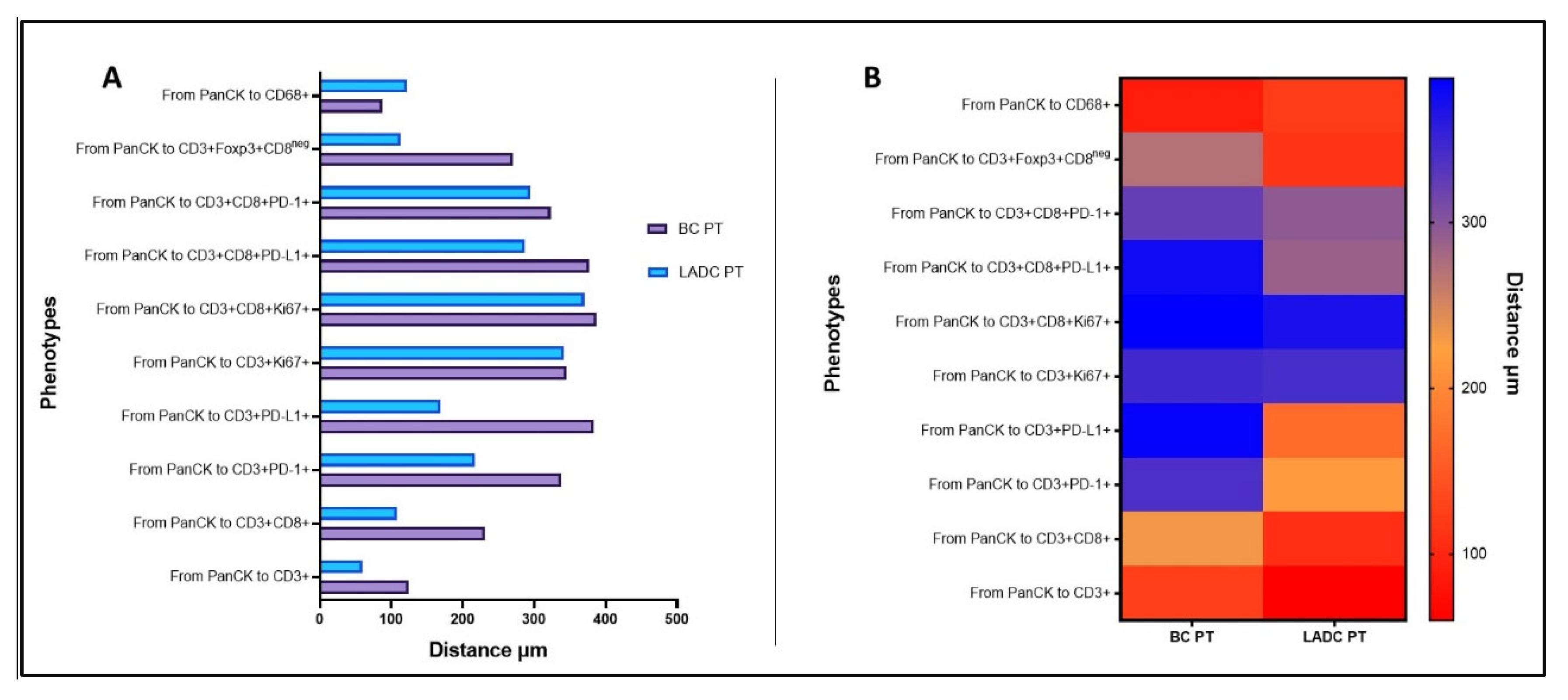

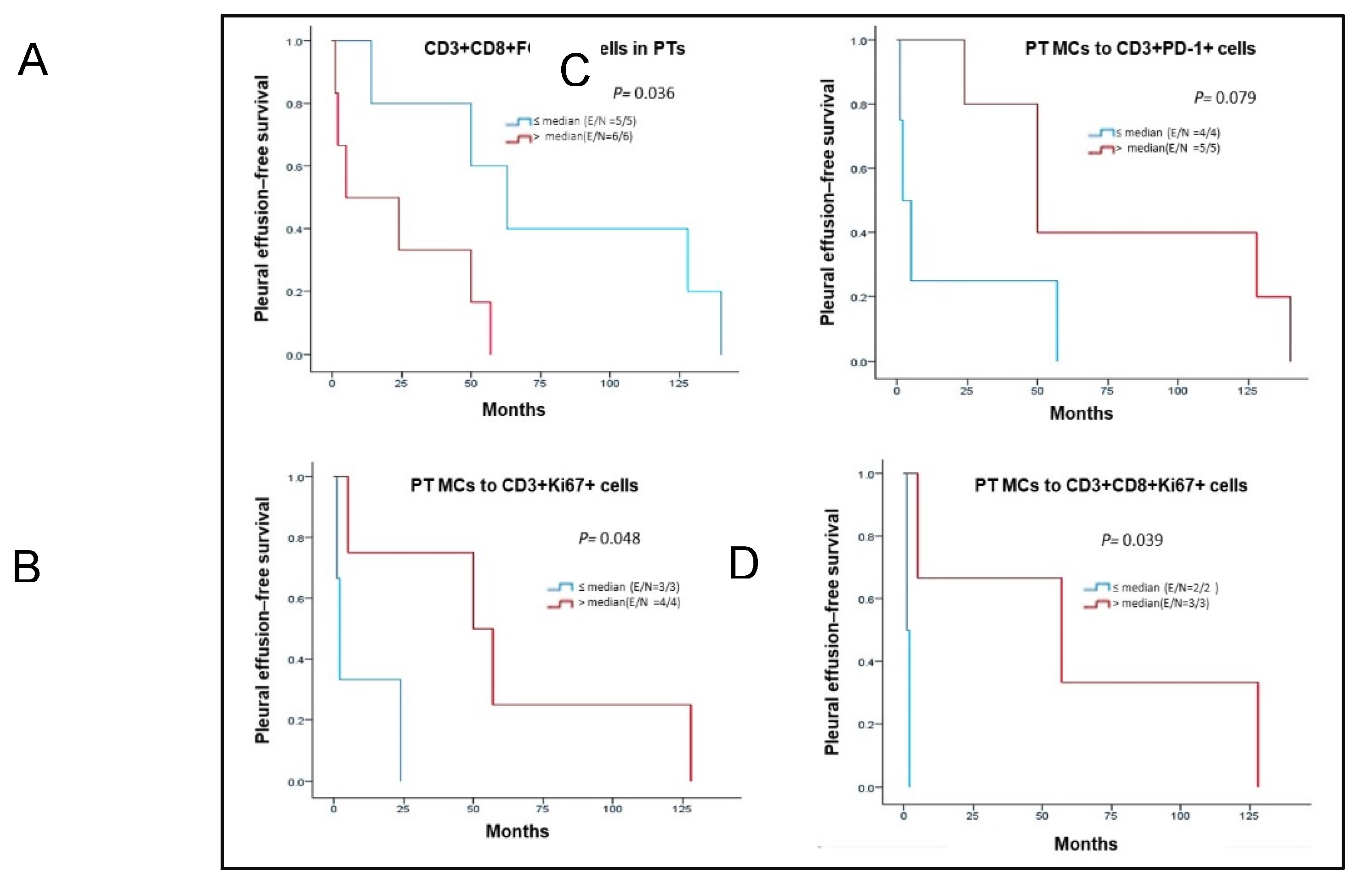

Spatial Cellular Distribution in PTs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

List of Abbreviations

| BC: | breast carcinoma |

| CD: | cluster of differentiation |

| FFPE: | formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded |

| FOXP3: | forkhead box P3 |

| H&E: | hematoxylin and eosin |

| IHC: | immunohistochemistry |

| LADC: | lung adenocarcinoma |

| mIF: | multiplex immunofluorescence |

| MPE: | malignant pleural effusion |

| NSCLC: | non-small cell lung cancer |

| OS: | overall survival |

| panCK: | pancytokeratin |

| PD-1: | programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PD-L1: | programmed death-ligand 1 |

| PEFS: | pleural effusion–free survival |

| PT: | primary tumor |

| ROI: | regions of interest |

| TME: | tumor microenvironment |

| TTF-1: | thyroid transcription factor-1 |

| WT-1: | Wilms tumor 1 |

References

- American Thoracic Society. Management of malignant pleural effusions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 162, 1987–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epelbaum, O.; Rahman, N.M. Contemporary approach to the patient with malignant pleural effusion complicating lung cancer. Ann Transl Med 2019, 7, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, P.; Ekeke, C.N.; Russell, K.L.; Butler, S.C.; Wang, Y.; Luketich, J.D.; Soloff, A.C.; Dhupar, R.; Lotze, M.T. Making cold malignant pleural effusions hot: driving novel immunotherapies. Oncoimmunology 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tingquist, N.D.; Steliga, M.A. 72 - Diagnosis and Management of Pleural Metastases and Malignant Effusion in Breast Cancer. In The Breast (Fifth Edition), Bland, K.I., Copeland, E.M., Klimberg, V.S., Gradishar, W.J., Eds.; Elsevier: 2018; pp. 934-941.e932.

- Casal-Mourino, A.; Ruano-Ravina, A.; Lorenzo-Gonzalez, M.; Rodriguez-Martinez, A.; Giraldo-Osorio, A.; Varela-Lema, L.; Pereiro-Brea, T.; Barros-Dios, J.M.; Valdes-Cuadrado, L.; Perez-Rios, M. Epidemiology of stage III lung cancer: frequency, diagnostic characteristics, and survival. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2021, 10, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018, 68, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, J.; Ginsburg, O.; Rochon, P.A.; Sun, P.; Narod, S.A. Differences in Breast Cancer Stage at Diagnosis and Cancer-Specific Survival by Race and Ethnicity in the United States. JAMA 2015, 313, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. Treatment Choices for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, by Stage. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/lung-cancer/treating-non-small-cell/by-stage.html (accessed on January 7).

- Parra, E.R.; Uraoka, N.; Jiang, M.; Cook, P.; Gibbons, D.; Forget, M.-A.; Bernatchez, C.; Haymaker, C.; Wistuba, I.I.; Rodriguez-Canales, J. Validation of multiplex immunofluorescence panels using multispectral microscopy for immune-profiling of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded human tumor tissues. Sci Rep-Uk 2017, 7, 13380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangarajah, F.; Enninga, I.; Malter, W.; Hamacher, S.; Markiefka, B.; Richters, L.; Krämer, S.; Mallmann, P.; Kirn, V. A Retrospective Analysis of Ki-67 Index and its Prognostic Significance in Over 800 Primary Breast Cancer Cases. Anticancer Research 2017, 37, 1957–1964. [Google Scholar]

- Russell-Goldman, E.; Kravets, S.; Dahlberg, S.E.; Sholl, L.M.; Vivero, M. Cytologic-histologic correlation of programmed death-ligand 1 immunohistochemistry in lung carcinomas. Cancer Cytopathol 2018, 126, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Agulnik, J.; Kasymjanova, G.; Wang, A.; Jimenez, P.; Cohen, V.; Small, D.; Pepe, C.; Sakr, L.; Fiset, P.O.; et al. Cytology cell blocks are suitable for immunohistochemical testing for PD-L1 in lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2018, 29, 1417–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skov, B.G.; Skov, T. Paired Comparison of PD-L1 Expression on Cytologic and Histologic Specimens From Malignancies in the Lung Assessed With PD-L1 IHC 28-8pharmDx and PD-L1 IHC 22C3pharmDx. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2017, 25, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heymann, J.J.; Bulman, W.A.; Swinarski, D.; Pagan, C.A.; Crapanzano, J.P.; Haghighi, M.; Fazlollahi, L.; Stoopler, M.B.; Sonett, J.R.; Sacher, A.G.; et al. PD-L1 expression in non-small cell lung carcinoma: Comparison among cytology, small biopsy, and surgical resection specimens. Cancer Cytopathol 2017, 125, 896–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, M.; Juco, J.; Huang, L.K.; Hofman, V.; Khambata-Ford, S.; Hofman, P. Use of the 22C3 anti-programmed death-ligand 1 antibody to determine programmed death-ligand 1 expression in cytology samples obtained from non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Cytopathology 2018, 126, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Xu, L.; Tang, Q.; You, Q.; Wang, X.; Ding, W.; Zhao, J.; Ren, G. Cytology cell blocks from malignant pleural effusion are good candidates for PD-L1 detection in advanced NSCLC compared with matched histology samples. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yatabe, Y.; Dacic, S.; Borczuk, A.C.; Warth, A.; Russell, P.A.; Lantuejoul, S.; Beasley, M.B.; Thunnissen, E.; Pelosi, G.; Rekhtman, N.; et al. Best Practices Recommendations for Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry in Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2019, 14, 377–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Wang, H.; Zhou, H.; He, H.; Qiu, L.; Wang, Z. Correlation between expression of Ki-67 and MSCT signs in different types of lung adenocarcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e18678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafez, N.H.; Tahoun, N.S. Diagnostic value of p53 and ki67 immunostaining for distinguishing benign from malignant serous effusions. J Egypt Natl Cancer 2011, 23, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.; Wang, X.; Fan, C.; Mao, X. The Role of Ki67 in Evaluating Neoadjuvant Endocrine Therapy of Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 687244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobecki, M.; Mrouj, K.; Colinge, J.; Gerbe, F.; Jay, P.; Krasinska, L.; Dulic, V.; Fisher, D. Cell-Cycle Regulation Accounts for Variability in Ki-67 Expression Levels. Cancer Res 2017, 77, 2722–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Ma, D.; Gao, R.-F.; Yu, K.-D. Effect of Ki-67 Expression Levels and Histological Grade on Breast Cancer Early Relapse in Patients with Different Immunohistochemical-based Subtypes. Sci Rep-Uk 2020, 10, 7648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principe, N.; Kidman, J.; Lake, R.A.; Lesterhuis, W.J.; Nowak, A.K.; McDonnell, A.M.; Chee, J. Malignant Pleural Effusions-A Window Into Local Anti-Tumor T Cell Immunity? Front Oncol 2021, 11, 672747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Principe, D.R.; Chiec, L.; Mohindra, N.A.; Munshi, H.G. Regulatory T-Cells as an Emerging Barrier to Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Lung Cancer. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 684098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Brien, S.M.; Klampatsa, A.; Thompson, J.C.; Martinez, M.C.; Hwang, W.T.; Rao, A.S.; Standalick, J.E.; Kim, S.; Cantu, E.; Litzky, L.A.; et al. Function of Human Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Early-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 2019, 7, 896–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Park, H.J.; Son, J.; Lee, J.G.; Chung, K.Y.; Cho, N.H.; Shim, H.S.; Park, S.; Kim, G.; In Yoon, H.; et al. Tumor microenvironment dictates regulatory T cell phenotype: Upregulated immune checkpoints reinforce suppressive function. J Immunother Cancer 2019, 7, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danenberg, E.; Bardwell, H.; Zanotelli, V.R.T.; Provenzano, E.; Chin, S.-F.; Rueda, O.M.; Green, A.; Rakha, E.; Aparicio, S.; Ellis, I.O.; et al. Breast tumor microenvironment structures are associated with genomic features and clinical outcome. Nature Genetics 2022, 54, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H.R.; Chlon, L.; Pharoah, P.D.P.; Markowetz, F.; Caldas, C. Patterns of Immune Infiltration in Breast Cancer and Their Clinical Implications: A Gene-Expression-Based Retrospective Study. Plos Medicine 2016, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczmarek, M.; Sikora, J. Macrophages in malignant pleural effusions - alternatively activated tumor associated macrophages. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2012, 16, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, B.Z.; Pollard, J.W. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell 2010, 141, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shihab, I.; Khalil, B.A.; Elemam, N.M.; Hachim, I.Y.; Hachim, M.Y.; Hamoudi, R.A.; Maghazachi, A.A. Understanding the Role of Innate Immune Cells and Identifying Genes in Breast Cancer Microenvironment. Cancers 2020, 12, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionova, I.; Tuguzbaeva, G.; Ponomaryova, A.; Stakheyeva, M.; Cherdyntseva, N.; Pavlov, V.; Choinzonov, E.; Kzhyshkowska, J. Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Human Breast, Colorectal, Lung, Ovarian and Prostate Cancers. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 566511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.Y.; Nguyen, A.V.; Russell, R.G.; Pollard, J.W. Colony-stimulating factor 1 promotes progression of mammary tumors to malignancy. J Exp Med 2001, 193, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backman, M.; Strell, C.; Lindberg, A.; Mattsson, J.S.M.; Elfving, H.; Brunnström, H.; O'Reilly, A.; Bosic, M.; Gulyas, M.; Isaksson, J.; et al. Spatial immunophenotyping of the tumour microenvironment in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer 2023, 185, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra, E.R.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, M.; Tamegnon, A.; Pandurengan, R.K.; Behrens, C.; Solis, L.; Haymaker, C.; Heymach, J.V.; Moran, C.; et al. Immune cellular patterns of distribution affect outcomes of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamma, R.; Guidolin, D.; Annese, T.; Tortorella, C.; Ruggieri, S.; Rega, S.; Zito, F.A.; Nico, B.; Ribatti, D. Spatial distribution of mast cells and macrophages around tumor glands in human breast ductal carcinoma. Experimental Cell Research 2017, 359, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eng, J.; Bucher, E.; Hu, Z.; Sanders, M.; Chakravarthy, B.; Gonzalez, P.; Pietenpol, J.A.; Gibbs, S.L.; Chin, K. Robust biomarker discovery through multiplatform multiplex image analysis of breast cancer clinical cohorts. bioRxiv, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Dai, L.J.; Wu, S.Y.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, D.; Jiang, Y.Z.; Shao, Z.M. Spatial architecture of the immune microenvironment orchestrates tumor immunity and therapeutic response. J Hematol Oncol 2021, 14, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltz, J.; Gupta, R.; Hou, L.; Kurc, T.; Singh, P.; Nguyen, V.; Samaras, D.; Shroyer, K.R.; Zhao, T.; Batiste, R.; et al. Spatial Organization and Molecular Correlation of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes Using Deep Learning on Pathology Images. Cell Rep 2018, 23, 181–193.e187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kather, J.N.; Suarez-Carmona, M.; Charoentong, P.; Weis, C.-A.; Hirsch, D.; Bankhead, P.; Horning, M.; Ferber, D.; Kel, I.; Herpel, E.; et al. Topography of cancer-associated immune cells in human solid tumors. eLife 2018, 7, e36967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keren, L.; Bosse, M.; Marquez, D.; Angoshtari, R.; Jain, S.; Varma, S.; Yang, S.-R.; Kurian, A.; Van Valen, D.; West, R.; et al. A Structured Tumor-Immune Microenvironment in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Revealed by Multiplexed Ion Beam Imaging. Cell 2018, 174, 1373–1387.e1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, E.R.; Zhai, J.; Tamegnon, A.; Zhou, N.; Pandurengan, R.K.; Barreto, C.; Jiang, M.; Rice, D.C.; Creasy, C.; Vaporciyan, A.A.; et al. Identification of distinct immune landscapes using an automated nine-color multiplex immunofluorescence staining panel and image analysis in paraffin tumor tissues. Sci Rep-Uk 2021, 11, 4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.L.; Li, L.; Guo, Y.W.; Yu, P.; Yin, X.J.; Wang, S.; Liu, C.P. CD8(+) cytotoxic and FoxP3(+) regulatory T lymphocytes serve as prognostic factors in breast cancer. Am J Transl Res 2019, 11, 5039–5053. [Google Scholar]

- Budna, J.; Spychalski, Ł.; Kaczmarek, M.; Frydrychowicz, M.; Goździk-Spychalska, J.; Batura-Gabryel, H.; Sikora, J. Regulatory T cells in malignant pleural effusions subsequent to lung carcinoma and their impact on the course of the disease. Immunobiology 2017, 222, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budna, J.; Kaczmarek, M.; Kolecka-Bednarczyk, A.; Spychalski, Ł.; Zawierucha, P.; Goździk-Spychalska, J.; Nowicki, M.; Batura-Gabryel, H.; Sikora, J. Enhanced Suppressive Activity of Regulatory T Cells in the Microenvironment of Malignant Pleural Effusions. J Immunol Res 2018, 2018, 9876014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spella, M.; Giannou, A.D.; Stathopoulos, G.T. Switching off malignant pleural effusion formation-fantasy or future? Journal of Thoracic Disease 2015, 7, 1009–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhupar, R.; Okusanya, O.T.; Eisenberg, S.H.; Monaco, S.E.; Ruffin, A.T.; Liu, D.; Luketich, J.D.; Kammula, U.S.; Bruno, T.C.; Lotze, M.T.; et al. Characteristics of Malignant Pleural Effusion Resident CD8+ T Cells from a Heterogeneous Collection of Tumors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 6178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, N.L.; Schalper, K.A.; Hatzis, C.; Saglam, O.; Tavassoli, F.; Butler, M.; Chagpar, A.B.; Pusztai, L.; Rimm, D.L. Quantitative assessment of the spatial heterogeneity of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2016, 18, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, P.; Carroll, R.G.; Henry, A.C.; Tanaka, T.; Ahmad, S.; Leibowitz, M.S.; Sterman, D.H.; June, C.H.; Albelda, S.M.; Vonderheide, R.H. Regulatory T cells and cytokines in malignant pleural effusions secondary to mesothelioma and carcinoma. Cancer Biology & Therapy 2005, 4, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laberiano, C.; Solis, L.; Chowdhuri, S.R.; Parra, E. Develop a Multiplex Immunofluorescence Panel to Identification of Distinct Complex Immune Landscapes in Pleural Effusion Liquids from Patients with Metastatic Lung Adenocarcinoma. Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer 2020, 8, A402–A402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobar, L.G.; Villalba-Esparza, M.; Abengozar-Muela, M.; Gigli, L.A.; Echeveste, J.I.; de Andrea, C.E.; Lozano, M.D. Utilisation of cytological samples for multiplex immunofluorescence assay. Cytopathology 2021, 32, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | BC n = 6 n (%) |

LADC n = 5 n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 6 (100) | 4 (80) |

| Male | 0 (0) | 1 (20) |

| Age, years (median) | 65 | 75 |

| Tumor localization | ||

| Right | 4 (67) | 2 (40) |

| Left | 2 (33) | 3 (60) |

| Smoker | ||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 2 (40) |

| No | 0 (0) | 2 (40) |

| Unknown | 6 (100) | 1 (20) |

| Histopathology | ||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 5 (83) | - |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 1 (17) | - |

| Adenocarcinoma | - | 5 (100) |

| Stage at PT diagnosis | ||

| I | 0 (0) | 2 (40) |

| II | 1 (17) | 0 (0) |

| III | 1 (17) | 1 (20) |

| IV | 4 (67) | 2 (40) |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Treatment | ||

| Chemotherapy | 2 (33) | 1 (20) |

| Chemotherapy + surgery | 4 (67) | 0 (0) |

| Chemotherapy + radiotherapy | 0 (0) | 2 (40) |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 2 (40) |

| IHC results for PT | ||

| ER+, PR−, HER2− | 1 (17) | N/A |

| ER+, PR+, HER2− | 3 (50) | N/A |

| ER+, PR+, HER2+ | 1 (17) | N/A |

| ER−, PR−, HER2- | 1 (17) | N/A |

| EGFR+ | N/A | 1 (20) |

| EGFR− | N/A | 1 (20) |

| Unknown | 0 | 3 (60) |

| Median period between PT diagnosis and MPE collection, months | 37 (2-140) | 57 (1-128) |

| Median OS after MPE collection, months | 4.5 (1-18) | 16.5 (1-31) |

| Median OS from PT diagnosis to death, months | 53.5 (14-372) | 55.5 (32-154) |

| BC samples (%) | LADC samples (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Location | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 |

| *PD-L1+ | PT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.0 | 0 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 1.0 | 10.0 |

| MPE | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ki67+ | PT | 32.4 | 14.1 | 7.8 | 29.7 | 9.4 | 1.1 | 0 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 1.0 | 10.0 |

| MPE | 23.0 | 2.4 | 7.3 | 4.8 | 3.9 | 35.2 | 14.8 | 13.4 | 5.5 | 2.5 | 14.8 | |

| BC PT samples, % | LADC PT samples, % | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell phenotype | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 |

| CD3+ | 49.6 | 15.2 | 53.0 | 19.3 | 33.3 | 35.7 | 63.6 | 82.4 | 66.9 | 66.7 | 40.7 |

| CD3+CD8+ | 8.0 | 1.8 | 25.6 | 9.1 | 0 | 4.3 | 6.4 | 11.3 | 15.7 | 2.9 | 10.4 |

| CD3+PD-1+ | 1.8 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 5.7 | 0 | 1.7 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 0 | 0 | 1.7 |

| CD3+PD-L1+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.3 | 2.9 | 0 |

| CD3+Ki67+ | 0.9 | 0 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 |

| CD3+CD8+Ki67+ | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 |

| CD3+PD-1+PD-L1+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CD3+CD8+PD-L1+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 |

| CD3+CD8+PD-1+ | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 |

| CD3+FOXP3+CD8neg | 3.5 | 2.9 | 1.7 | 5.7 | 0 | 0 | 7.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.9 |

| CD68+ | 36.0 | 79.8 | 18.9 | 56.8 | 66.7 | 57.4 | 18.3 | 2.2 | 6.3 | 27.5 | 40.3 |

| CD68+PD-L1+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BC MPE samples, % | LADC MPE samples, % | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell phenotype | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 |

| CD3+ | 13.7 | 83.9 | 46.8 | 12.2 | 10.9 | 56.3 | 62.7 | 12.6 | 28.0 | 45.6 | 70.0 |

| CD3+CD8+ | 2.6 | 8.8 | 6.3 | 3.8 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 7.5 | 4.7 | 10.7 |

| CD3+PD-1+ | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.1 |

| CD3+PD-L1+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| CD3+Ki67+ | 1.0 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 1.6 |

| CD3+CD8+Ki67+ | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| CD3+PD-1+PD-L1+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CD3+CD8+PD-L1+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| CD3+CD8+PD-1+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 |

| CD3+FOXP3+CD8neg | 0.3 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 4.0 | 6.9 |

| CD68+ | 82.0 | 1.2 | 43.2 | 79.2 | 85.7 | 37.5 | 29.0 | 83.3 | 63.3 | 44.1 | 8.2 |

| CD68+PD-L1+ | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).