Submitted:

06 June 2023

Posted:

07 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

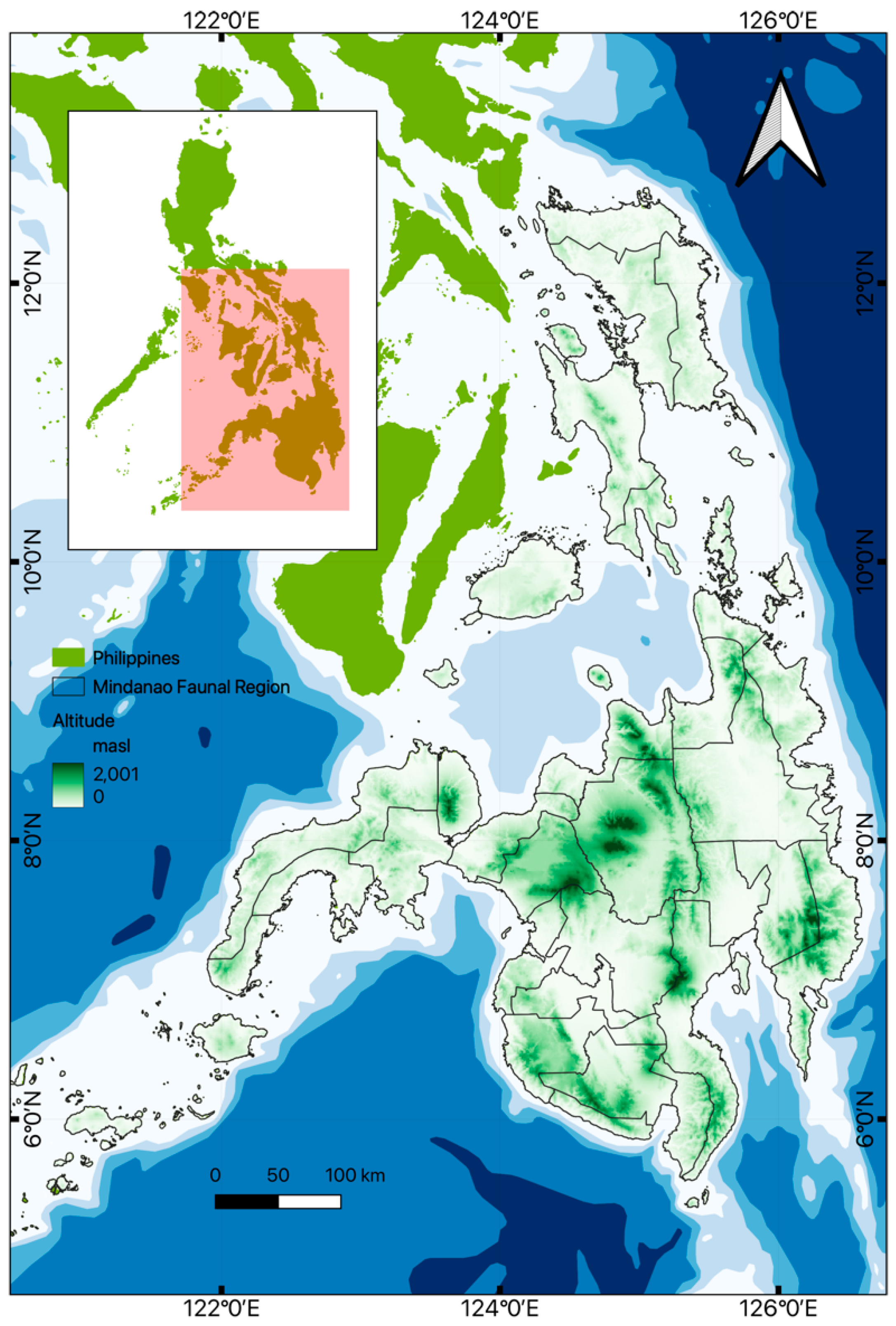

2.1. Study area and synthesis framework

2.2. Literature search and databasing

2.3. Diversity and Distribution of Amphibians and Reptiles

2.4. Site-level comparison

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

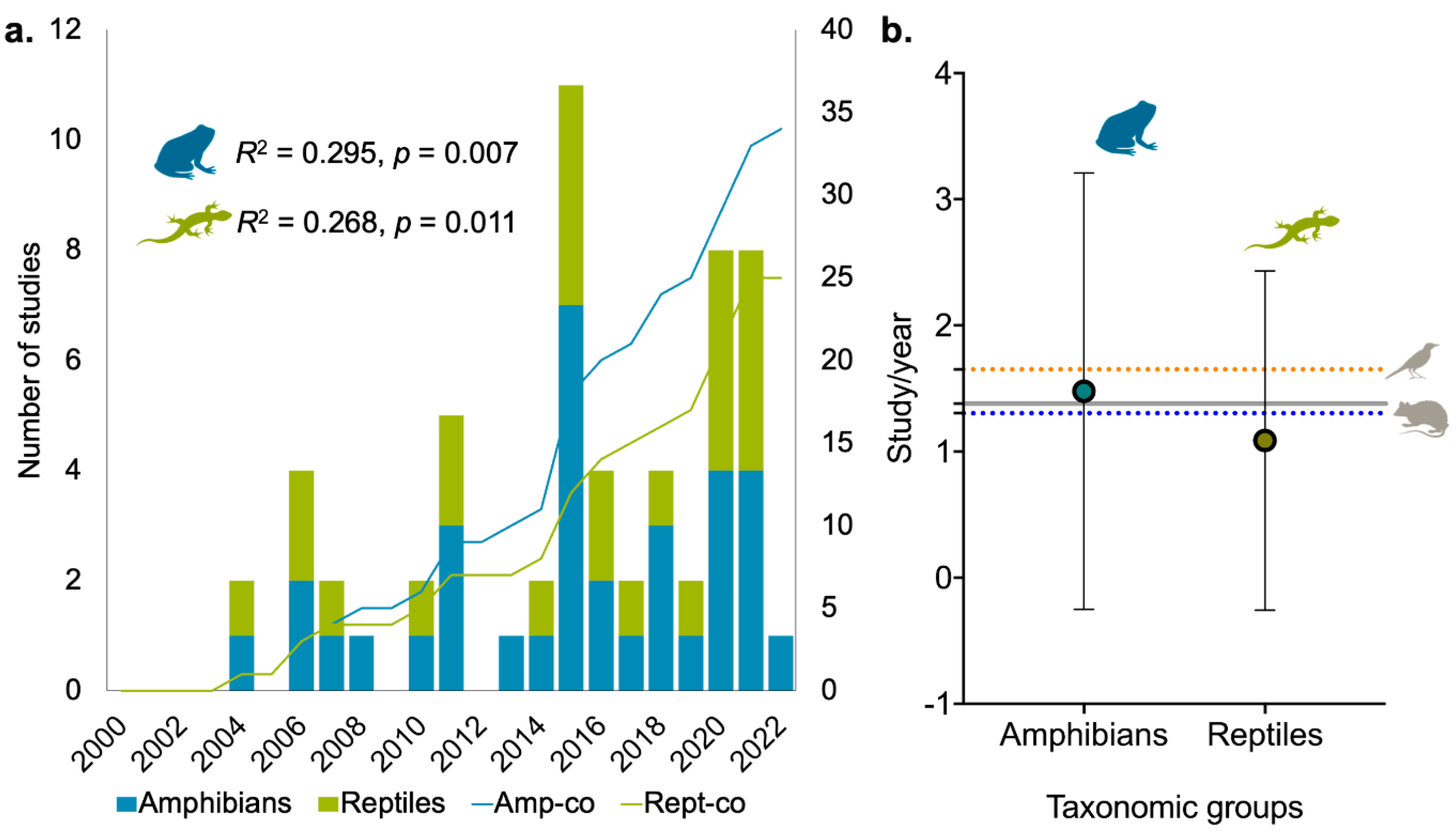

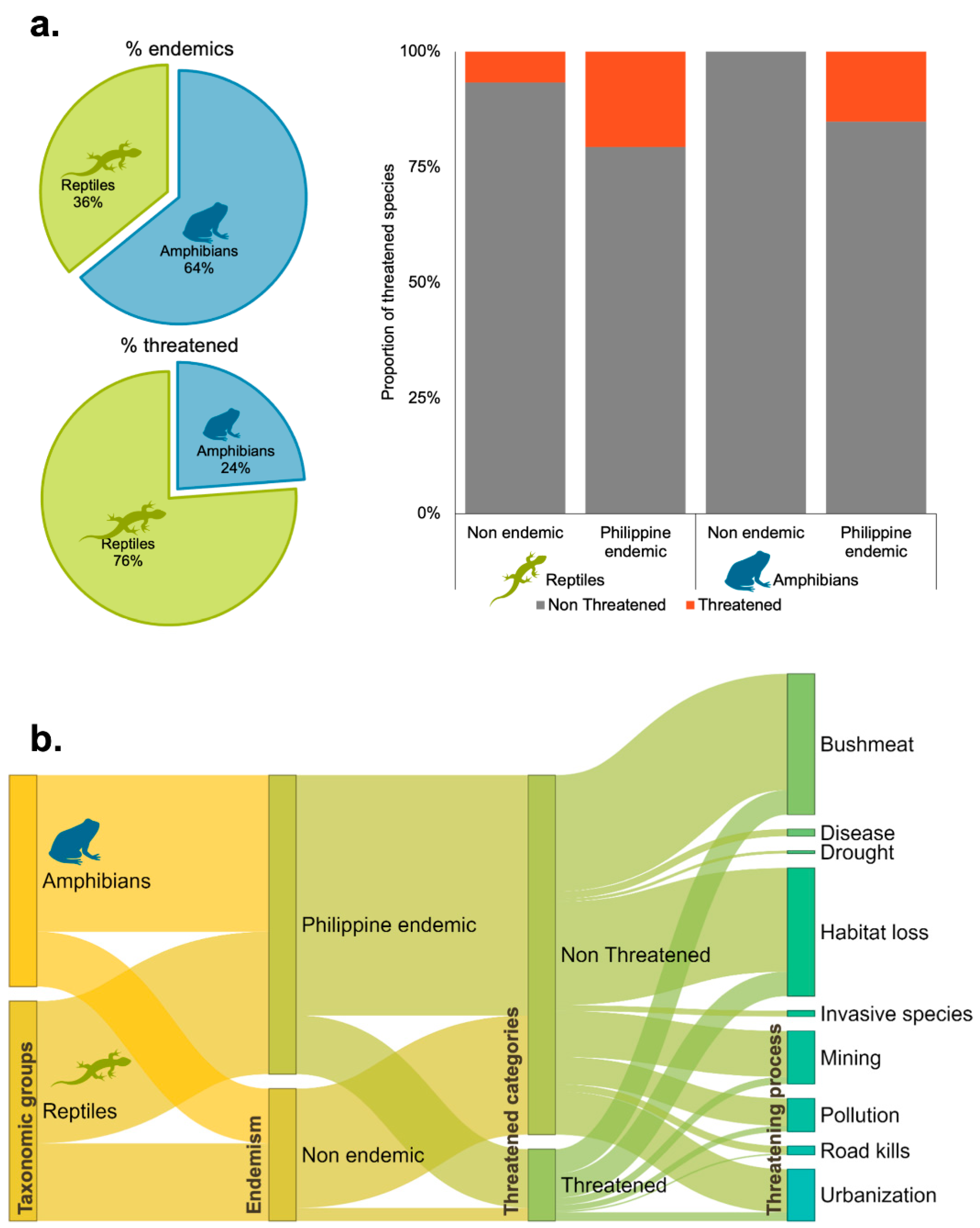

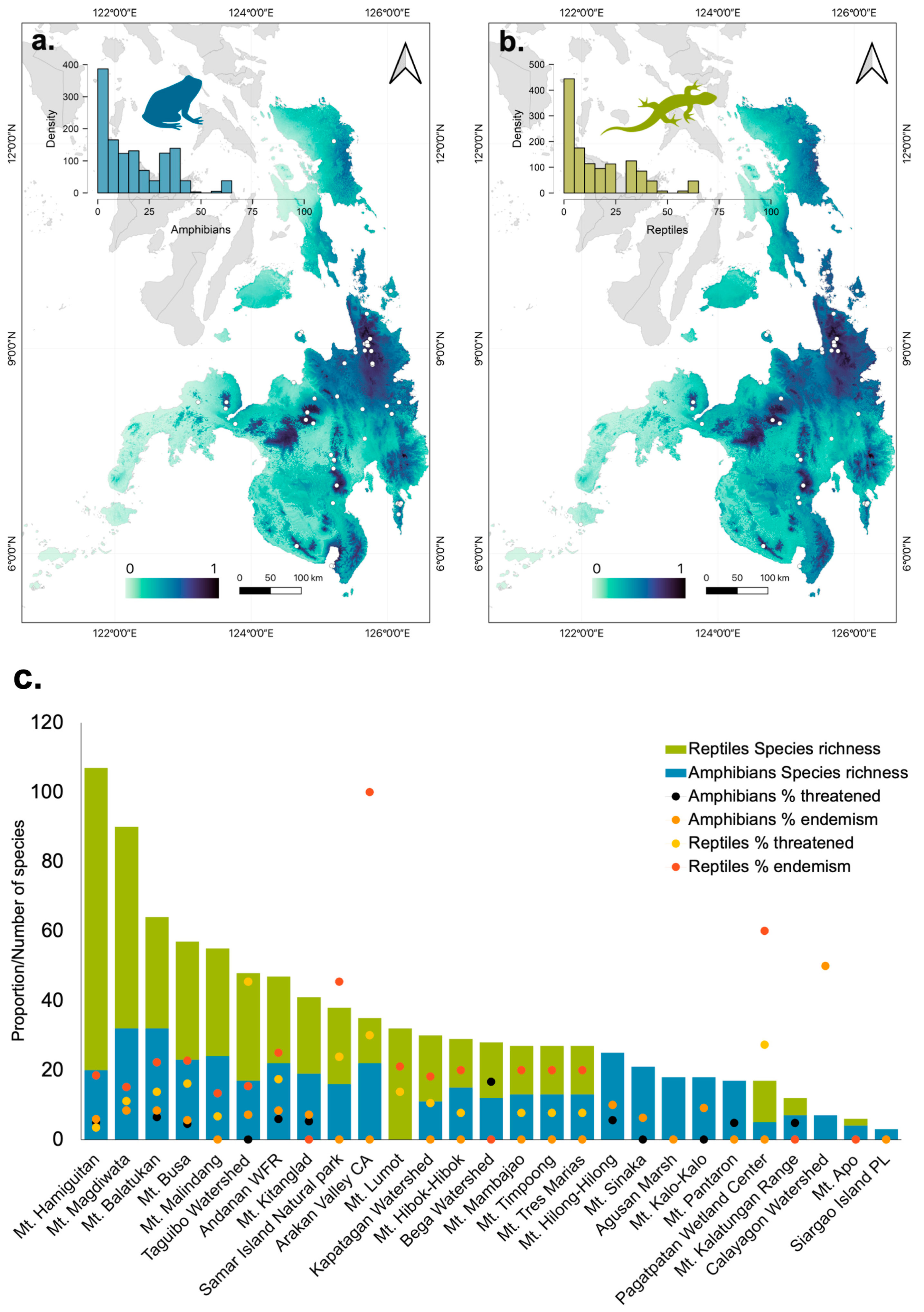

3.1. Diversity and distribution of herpetofauna in Mindanao

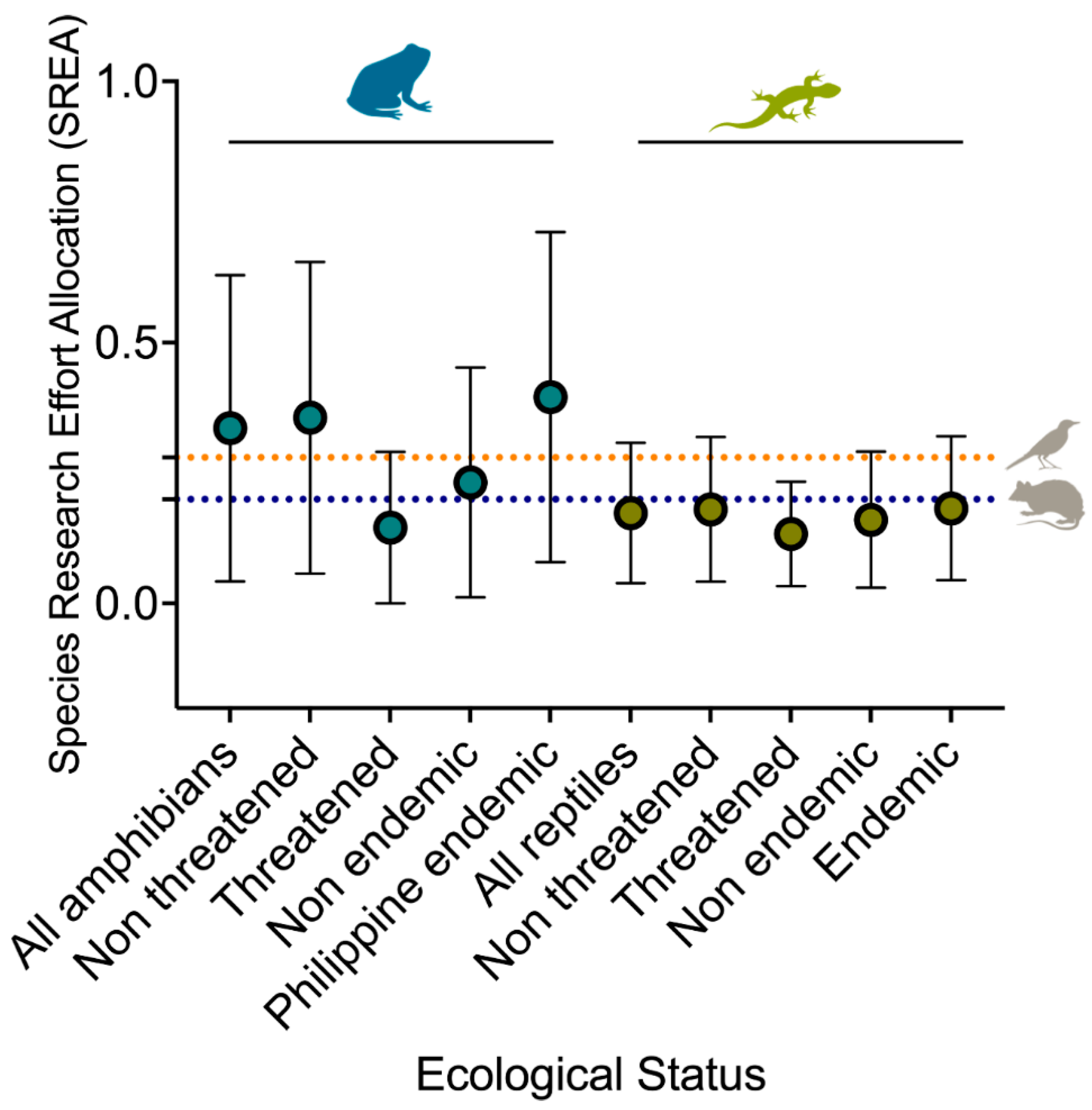

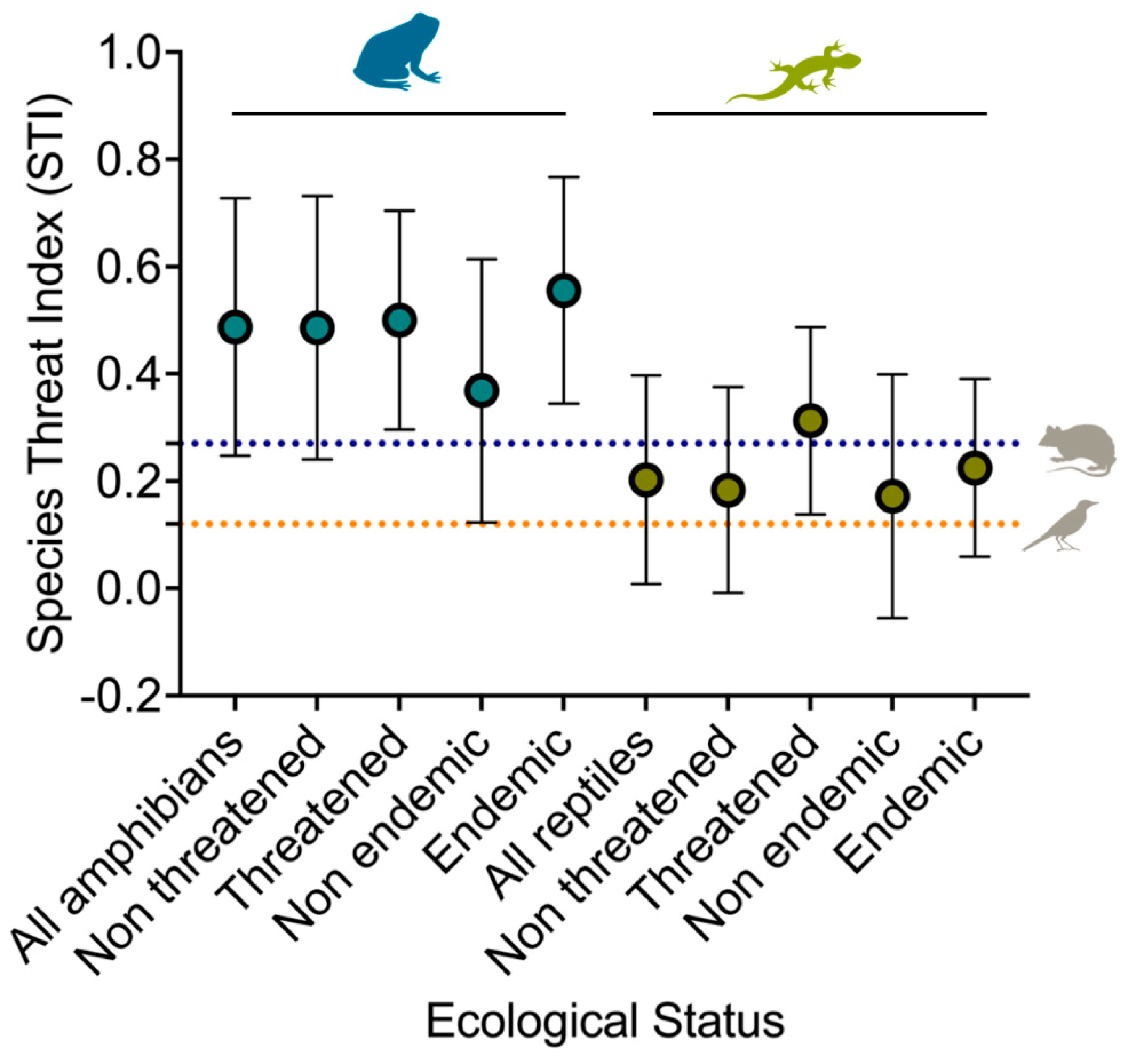

3.2. Conservation status across ecological status

3.3. Relationship between Threat Index and Research Effort

3.4. Site-level Priorities

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Barnosky, A.D.; García, A.; Pringle, R.M.; Palmer, T.M. Accelerated Modern Human–Induced Species Losses: Entering the Sixth Mass Extinction. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1400253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wake, D.B.; Vredenburg, V.T. Are We in the Midst of the Sixth Mass Extinction? A View from the World of Amphibians. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 11466–11473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimm, S.L.; Jenkins, C.N.; Abell, R.; Brooks, T.M.; Gittleman, J.L.; Joppa, L.N.; Raven, P.H.; Roberts, C.M.; Sexton, J.O. The Biodiversity of Species and Their Rates of Extinction, Distribution, and Protection. Science 2014, 344, 1246752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickford, D.; Howard, S.D.; Ng, D.J.J.; Sheridan, J.A. Impacts of Climate Change on the Amphibians and Reptiles of Southeast Asia. Biodivers Conserv 2010, 19, 1043–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Hilton-Taylor, C.; Angulo, A.; Böhm, M.; Brooks, T.M.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Carpenter, K.E.; Chanson, J.; Collen, B.; Cox, N.A.; et al. The Impact of Conservation on the Status of the World’s Vertebrates. Science 2010, 330, 1503–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, M.; Collen, B.; Baillie, J.E.M.; Bowles, P.; Chanson, J.; Cox, N.; Hammerson, G.; Hoffmann, M.; Livingstone, S.R.; Ram, M.; et al. The Conservation Status of the World’s Reptiles. Biological Conservation 2013, 157, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hof, C.; Araújo, M.B.; Jetz, W.; Rahbek, C. Additive Threats from Pathogens, Climate and Land-Use Change for Global Amphibian Diversity. Nature 2011, 480, 516–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diesmos, A.; Brown, R.; Alcala, A.; Sison, R.; Afuang, L.; Gee, G. Philippine Amphibians and Reptiles: An Overview of Species Diversity, Biogeography, and Conservation. In Philippine Biodiversity Conservation Priorities: a Second Iteration of the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan; Department of the Environment and Natural Resources– Protected Areas and Wildlife Bureau, Conservation International Philippines, Biodiversity Conservation Program–University of the Philippines Center for Integrative and Developmental Studies, and Foundation for the Philippine Environment: Quezon City, Philippines, 2002; pp. 26–44. [Google Scholar]

- Diesmos, A.; Brown, R.; Alcala, A.; Sison, R.; Afuang, L.; Gee, G. Philippine Amphibians and Reptiles: An Overview of Species Diversity, Biogeography, and Conservation. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alcala, E.L.; Alcala, A.C.; Dolino, C.N. Amphibians and Reptiles in Tropical Rainforest Fragments on Negros Island, the Philippines. Environmental Conservation 2004, 31, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posa, M.R.C.; Diesmos, A.C.; Sodhi, N.S.; Brooks, T.M. Hope for Threatened Tropical Biodiversity: Lessons from the Philippines. BioScience 2008, 58, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Brooks, T.M.; Fonseca, G.A.B. da; Gascon, C.; Hawkins, A.F.A.; James, R.E.; Langhammer, P.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Pilgrim, J.D.; Rodrigues, A.S.L.; et al. Conservation Planning and the IUCN Red List. Endangered Species Research 2008, 6, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinini, C.; Rodrigues, A.S.L.; Boitani, L. The Key Elements of a Comprehensive Global Mammal Conservation Strategy. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2011, 366, 2591–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanalgo, K.C.; Oliveira, H.F.M.; Hughes, A.C. Mapping Global Conservation Priorities and Habitat Vulnerabilities for Cave-Dwelling Bats in a Changing World. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 843, 156909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, N.; Bielby, J.; Thomas, G.H.; Purvis, A. Macroecology and Extinction Risk Correlates of Frogs. Global Ecology and Biogeography 2008, 17, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberling, J.M.; Miller, J.T.; Noesgaard, D.; Weingart, S.B.; Schigel, D. Data Integration Enables Global Biodiversity Synthesis. PNAS 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, D. Compilation & Synthesis of Valuation Studies on Philippine Biodiversity 2016.

- Diesmos, A.; Watters, J.; Huron, N.; Davis, D.; Alcala, A.; Crombie, R.; Afuang, L.; Gee-Das, G.; Sison, R.; Sanguila, M.; et al. Amphibians of the Philippines, Part 1: Checklist of the Species. 2015, 62.

- Sanguila, M.B.; Cobb, K.A.; Siler, C.D.; Diesmos, A.C.; Alcala, A.C.; Brown, R.M. The Amphibians and Reptiles of Mindanao Island, Southern Philippines, II: The Herpetofauna of Northeast Mindanao and Adjacent Islands. Zookeys 2016, 1–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dela Cruz, K.C.; Abdullah, S.S.; Agduma, A.R.; Tanalgo, K.C. Early Twenty-First Century Biodiversity Data Pinpoint Key Targets for Bird and Mammal Conservation in Mindanao, Southern Philippines. Biodiversity 2023, 0, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agduma, A.R.; Garcia, F.G.; Cabasan, M.T.; Pimentel, J.; Ele, R.J.; Rubio, M.; Murray, S.; Hilario-Husain, B.A.; Dela Cruz, K.C.; Abdullah, S.; et al. Overview of Priorities, Threats, and Challenges to Biodiversity Conservation in the Southern Philippines. Regional Sustainability 2023, 4, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanalgo, K.C.; Hughes, A.C. Priority-Setting for Philippine Bats Using Practical Approach to Guide Effective Species Conservation and Policy-Making in the Anthropocene. Hystrix 2019, 30, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, M.D.F.; Moher, D.; Thombs, B.D.; McGrath, T.A.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Clifford, T.; Cohen, J.F.; Deeks, J.J.; Gatsonis, C.; Hooft, L.; et al. Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies: The PRISMA-DTA Statement. JAMA 2018, 319, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J.; Tanalgo, K.; Landscape Ecology Group, Center for Integrative Conservation, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Menglun, Mengla 666303, Yunnan Province, P.R. China; Abante, C. Bicol University Research and Development Management Division, Legazpi City 4500, the Republic of the Philippines Role of Academic Institution to Inform Local and Regional Scale Biodiversity in the Eastern Philippines. J.Trop.Life.Science 2021, 11, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanalgo, K.C.; Hughes, A.C. Bats of the Philippine Islands—A Review of Research Directions and Relevance to National-Level Priorities and Targets. Mammalian Biology 2018, 91, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanguila, M.B.; Cobb, K.A.; Siler, C.D.; Diesmos, A.C.; Alcala, A.C.; Brown, R.M. The Amphibians and Reptiles of Mindanao Island, Southern Philippines, II: The Herpetofauna of Northeast Mindanao and Adjacent Islands. Zookeys 2016, 1–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AmphibiaWeb Database AmphibiaWeb Database Search . Available online: https://amphibiaweb.org/search/ (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- The Reptile Database The Reptile Database. Available online: https://reptile-database.reptarium.cz/ (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Atwood, T.B.; Valentine, S.A.; Hammill, E.; McCauley, D.J.; Madin, E.M.; Beard, K.H.; Pearse, W.D. Herbivores at the Highest Risk of Extinction among Mammals, Birds, and Reptiles. Science advances 2020, 6, eabb8458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bland, L.M.; Collen, B.; Orme, C.D.L.; Bielby, J. Predicting the Conservation Status of Data-Deficient Species: Predicting Extinction Risk. Conservation Biology 2015, 29, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanalgo, K.C.; Tabora, J.A.G.; Hughes, A.C. Bat Cave Vulnerability Index (BCVI): A Holistic Rapid Assessment Tool to Identify Priorities for Effective Cave Conservation in the Tropics. Ecological Indicators 2018, 89, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Dudík, M.; Schapire, R.E.; Blair, M.E. Opening the Black Box: An Open-Source Release of Maxent. Ecography 2017, 40, 887–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R.J.; Cameron, S.E.; Parra, J.L.; Jones, P.G.; Jarvis, A. Very High Resolution Interpolated Climate Surfaces for Global Land Areas. International Journal of Climatology 2005, 25, 1965–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daipan, B.P. Patterns of Forest Cover Loss in the Terrestrial Key Biodiversity Areas in the Philippines: Critical Habitat Conservation Priorities. Journal of Threatened Taxa 2021, 13, 20019–20032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project Jamovi (Version 2.3.22) [Computer Software]. 2023.

- GraphPad Prism GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA 2022.

- QGIS Development Team QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. Http://Qgis.Osgeo.Org 2022.

- DIESMOS, A.C. Ecology and Diversity of Herpetofaunal Communities in Fragmented Lowland Rainforests in the Philippines. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Plaza, J.; Sanguila, M. Preliminary Report on the Anurans of Mount Hilong-Hilong, Agusan Del Norte, Eastern Mindanao, Philippines. Asian Herpetological Research 2015, 6, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitogo, K.M.; Saavedra, A.J.; Afuang, L. Amphibians and Reptiles of Mount Busa, Sarangani Province: A Glimpse of the Herpetological Community of Southern Mindanao, Philippines. Philippine Journal of Science 2021, 150, 1279–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoffel, R.A.; Lepczyk, C.A. Representation of Herpetofauna in Wildlife Research Journals. The Journal of Wildlife Management 2012, 76, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, J.J.M.; Moura, M.R.; Alexandre, F. Diniz-Filho, J. Species out of Sight: Elucidating the Determinants of Research Effort in Global Reptiles. Ecography 2023, 2023, e06491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colli, G.R.; Fenker, J.; Tedeschi, L.G.; Barreto-Lima, A.F.; Mott, T.; Ribeiro, S.L.B. In the Depths of Obscurity: Knowledge Gaps and Extinction Risk of Brazilian Worm Lizards (Squamata, Amphisbaenidae). Biological Conservation 2016, 204, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, M.R.; Costa, H.C.; Abegg, A.D.; Alaminos, E.; Angarita-Sierra, T.; Azevedo, W.S.; Cabral, H.; Carvalho, P.; Cechin, S.; Citeli, N.; et al. Unwrapping Broken Tails: Biological and Environmental Correlates of Predation Pressure in Limbless Reptiles. Journal of Animal Ecology 2023, 92, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovan, S.O.; Al-Fulaij, N.; Christie, A.; Andrews, H. Why Link Diverse Citizen Science Surveys? Widespread Arboreal Habits of a Terrestrial Amphibian Revealed by Mammalian Tree Surveys in Britain. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0265156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnet, X.; Shine, R.; Lourdais, O. Taxonomic Chauvinism. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2002, 17, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri-Mitchell, C. The More Things Changed, the More They Stayed the Same: Trends in Conservation Focus 2010–2019. Journal for Nature Conservation 2023, 73, 126403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducatez, S.; Shine, R. Drivers of Extinction Risk in Terrestrial Vertebrates. Conservation Letters 2017, 10, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y. Ecological Correlates of Extinction Risk in Chinese Amphibians. Diversity and Distributions 2019, 25, 1586–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catenazzi, A. State of the World’s Amphibians. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2015, 40, 91–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfoot, M.B.J.; Johnston, A.; Balmford, A.; Burgess, N.D.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Dias, M.P.; Hazin, C.; Hilton-Taylor, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Isaac, N.J.B.; et al. Using the IUCN Red List to Map Threats to Terrestrial Vertebrates at Global Scale. Nat Ecol Evol 2021, 5, 1510–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, S.N.; Chanson, J.S.; Cox, N.A.; Young, B.E.; Rodrigues, A.S.L.; Fischman, D.L.; Waller, R.W. Status and Trends of Amphibian Declines and Extinctions Worldwide. Science 2004, 306, 1783–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo-Cavia, N.; Burraco, P.; Gomez-Mestre, I. Low Levels of Chemical Anthropogenic Pollution May Threaten Amphibians by Impairing Predator Recognition. Aquatic Toxicology 2016, 172, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J.W.; Scott, D.E.; Ryan, T.J.; Buhlmann, K.A.; Tuberville, T.D.; Metts, B.S.; Greene, J.L.; Mills, T.; Leiden, Y.; Poppy, S.; et al. The Global Decline of Reptiles, Déjà Vu Amphibians: Reptile Species Are Declining on a Global Scale. Six Significant Threats to Reptile Populations Are Habitat Loss and Degradation, Introduced Invasive Species, Environmental Pollution, Disease, Unsustainable Use, and Global Climate Change. BioScience 2000, 50, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, N.; Young, B.E.; Bowles, P.; Fernandez, M.; Marin, J.; Rapacciuolo, G.; Böhm, M.; Brooks, T.M.; Hedges, S.B.; Hilton-Taylor, C.; et al. A Global Reptile Assessment Highlights Shared Conservation Needs of Tetrapods. Nature 2022, 605, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcala, A.; Bucol, A.; Diesmos, A.; Brown, R. Vulnerability of Philippine Amphibians to Climate Change. Philippine Journal of Science 2012, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Carrasco, M.; Medina, I.; Ord, T.J. Global Effects of Forest Modification on Herpetofauna Communities. Conservation Biology 2023, 37, e13998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.C.; Herrel, A.; Rödder, D. A Global Analysis of Habitat Fragmentation Research in Reptiles and Amphibians: What Have We Done so Far? Biodivers Conserv 2023, 32, 439–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (A) All herpetofauna | ||||

| Variables | β | SE | z | p |

| (Intercept) | 2.39 | 0.203 | 11.758 | < .001 |

| Threatened - Non threatened | -0.646 | 0.077 | -8.42 | < .001 |

| Philippine endemic - Non-endemic | 0.417 | 0.048 | 8.69 | < .001 |

| Body size (log10) | 0.273 | 0.064 | 4.256 | < .001 |

| Species Threat Index (SPI) | -0.02 | 0.116 | -0.172 | 0.863 |

| (B) Amphibians | ||||

| (Intercept) | 1.961 | 0.35 | 5.604 | < .001 |

| Threatened - Non threatened | -1.424 | 0.16 | -8.916 | < .001 |

| Philippine endemic - Non-endemic | 0.858 | 0.081 | 10.614 | < .001 |

| Body size (log10) | 0.544 | 0.152 | 3.591 | < .001 |

| Species Threat Index (SPI) | -0.355 | 0.158 | -2.243 | 0.025 |

| (C) Reptiles | ||||

| (Intercept) | 2.427 | 0.252 | 9.641 | < .001 |

| Threatened - Non threatened | -0.351 | 0.092 | -3.811 | < .001 |

| Philippine endemic - Non-endemic | 0.173 | 0.061 | 2.821 | 0.005 |

| Body size (log10) | 0.293 | 0.07 | 4.2 | < .001 |

| Species Threat Index (SPI) | 0.199 | 0.179 | 1.109 | 0.267 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).