3.1. Yeast Isolation and Identification

Forty-five isolates were recovered from the GM, HAF and EAF samples. To identify strains, a sequential analysis was performed: the ITS lengths found in isolates were 775, 800 and 850 bp. As a result of ITS sequencing, the isolates with 775 bp were identified as

Hanseniaspora valbyensis and

Hanseniaspora uvarum, those possessing 800 bp were taken as

Torulaspora delbrueckii, and those with 850 bp as

Saccharomyces cerevisiae. To know if different

S. cerevisiae strains were present during AF, a

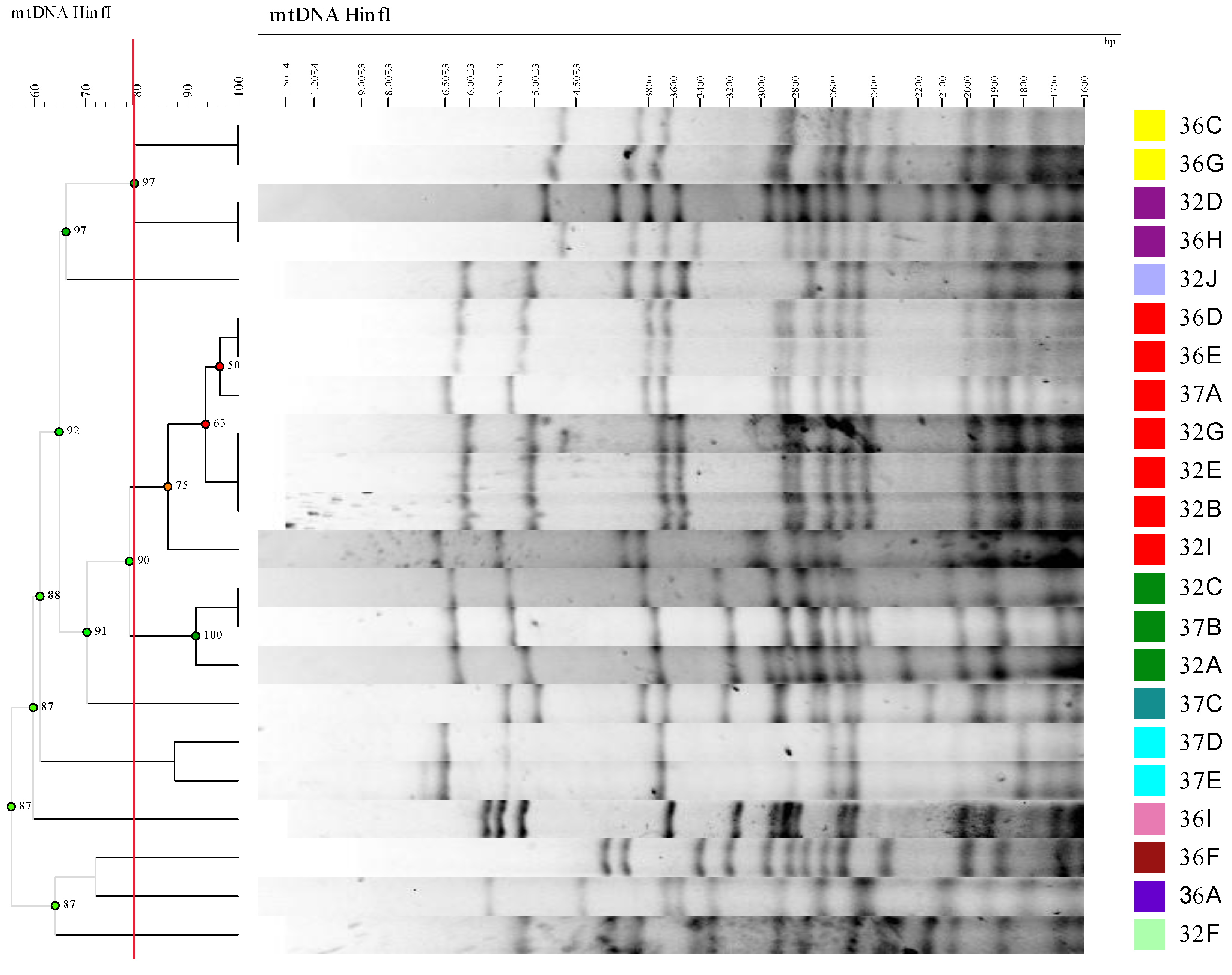

HinfI restriction mDNA analysis was done on the isolates belonging to this species. The results obtained by comparing restriction profiles appear in

Figure 1 and

Table 1.

The grape must obtained from an industrial fermenting vat had a total yeast count of 1.3x10

4 ± 2.1x10

2 CFU/mL. The microbiota was composed mainly of

T. delbrueckii (53.9%) and

H. uvarum (38.5%), whereas low

H. valbyensis percentages (7.7%) were found. The yeast population grew to reach 4.3x10

7 ± 4.2x10

6 CFU/mL at HAF, and diminished slightly to 1.1x10

7 ± 7.1x10

5 CFU/mL at EAF. At HAF and EAF, all the isolates belonged to

S. cerevisiae (100%). Lack of

S. cerevisiae isolates at GM was not surprising because some authors [

38,

39] have not found them on grape surfaces, and only at a very low concentration in grape must [

38]. The relatively low

S. cerevisiae concentration

versus the non-

Saccharomyces species was the reason why it was not easy to recover it when diluted grape must was spread on solid media. The presence of

Hanseniaspora uvarum or its anaomorph

Kloeckera apiculata is frequent in fresh must and in

Torulaspora delbrueckii, although the latter yeast has been less reported [

38,

40,

41,

42,

43].

The mDNA analysis results showed that the 22 isolates were grouped into 11 different patterns at the 79.5% cut-off level (

Figure 1). The isolates grouped in the same profile were considered to belong to the same strain. The most represented patterns (strains) in the Cabernet fermentations were patterns 2 (represented by isolate 32E) and 4 (represented by strain 32C), which respectively consisted of seven and three isolates. The other groups contained one isolate or two (

Table 1). At HAF, only profiles (representative strains) 1 (32F), 2 (32E), 3 (32D) and 4 (32C) were present. At EAF, all these profiles remained, except profile 1 (representative isolate 32F), whereas seven different profiles appeared (from 5 to 11, respectively represented by isolates 36I, 32J, 36F, 36C, 36A, 37E and 37C). Some profiles were detected only at one fermentation time point: profile 1 was exclusively present at HAF, whereas profiles 5 to 11 were recovered solely at EAF. The most abundant profile at HAF was profile 2 (50%), followed by profile 4 (25%), and profiles 1 and 3 were the least frequent (both with 12.5%). At EAF, profile 2 was still the most abundant (21%), albeit at a lower percentage than at HAF. The same occurred with profile 4, whose percentage dropped from 25% at HAF to 7% at EAF, whereas the newly appearing profiles 8 and 10 equaled the profile 4 percentage. Other profiles (5, 6, 7, 9, 11) that did not recovered at HAF were present with low percentages at EAF (7% for them all). All the recovered

S. cerevisiae strains were considered autochthonous strains because the winery had never used commercial yeasts. This high

S. cerevisiae diversity in a single fermentation has been previously reported [

44,

45]. Could the vineyard be the origin of the high diversity found in fermentation? Some authors have reported significant genetic diversity in

S. cerevisiae isolated directly from vineyards [

46,

47], whereas [

46] reportes different

S. cerevisiae biodiversity degrees in Malbec vineyards of the “Zona Alta del Río Mendoza” (Argentina). These authors attributed such differences to distinct vineyard practices. Other authors have stated that

S. cerevisiae strains come from winery equipment while fermentation is performed [

38]. We have no response for the origin of the strains isolated during Cabernet fermentation because we were unable to recover any

S. cerevisiae isolate at GM, which would have more clearly reflected the microbiota of the vineyard. In our case, strains 32F and 32C were dominant during fermentation. The larger number of strains found at EAF could reflect differences in growth behavior of the yeasts. We found differences in the growth kinetics of the different strains when they were grown alone in sterile Cabernet grape must (

Figure 2A). The strains 32C and 32E at HAF grew rapidly on the first three days in sterile grape must, but later died off more quickly than other strains, such as 36A, 36I, 37C and 37E. This different growth dynamics could explain why strains 32C and 32E were dominant at HAF, but not at EAF in the industrial fermentation. A similar picture of dominance and succession of

S. cerevisiae strains during fermentations has been previously reported [

44,

45,

48].

3.2. S. cerevisiae Yeast Characterization

The growth kinetics and fermentative characteristics of the 11 S. cerevisiae strains were tested in the same industrial Cabernet grape must from which they were isolated. In this way, the results could be better extrapolated to industrial fermentation than if they had been performed in synthetic grape must.

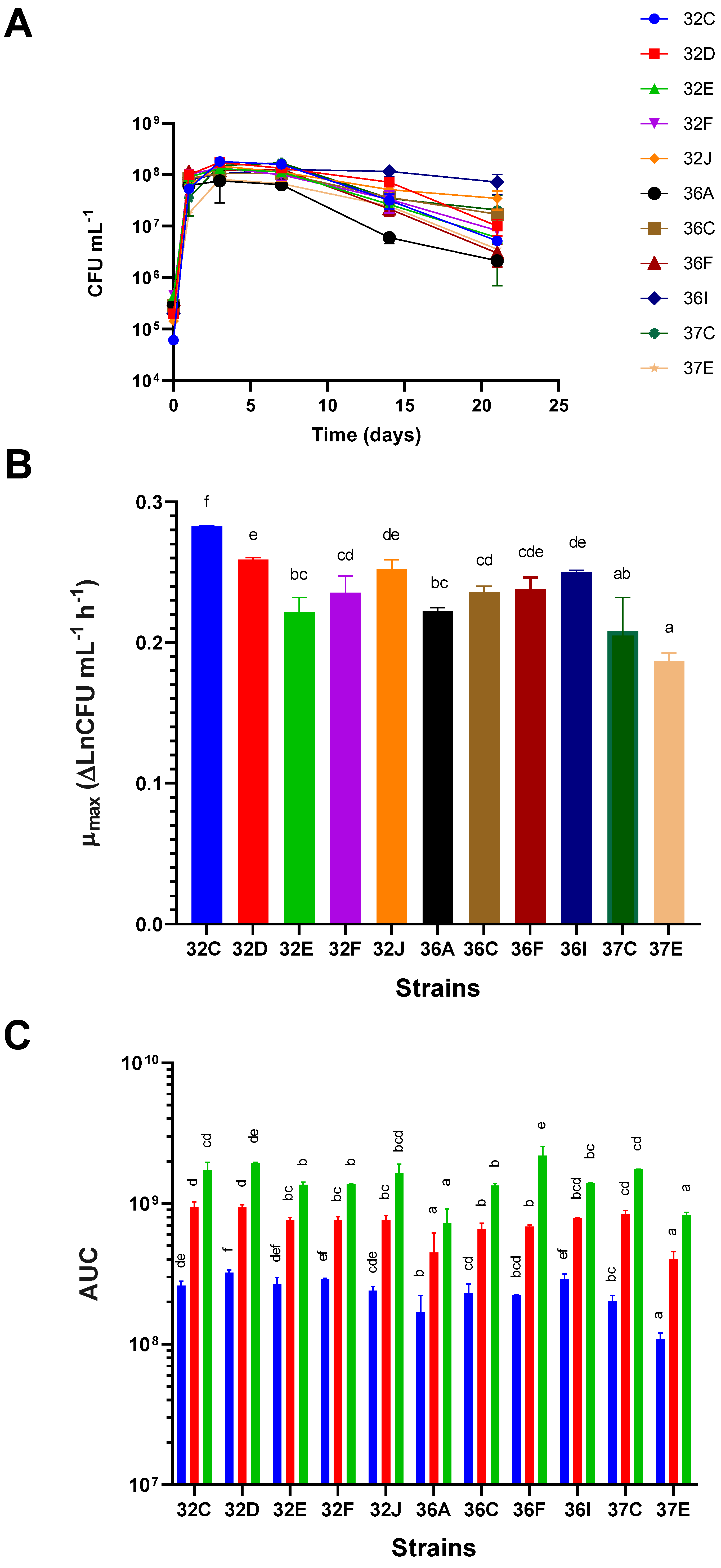

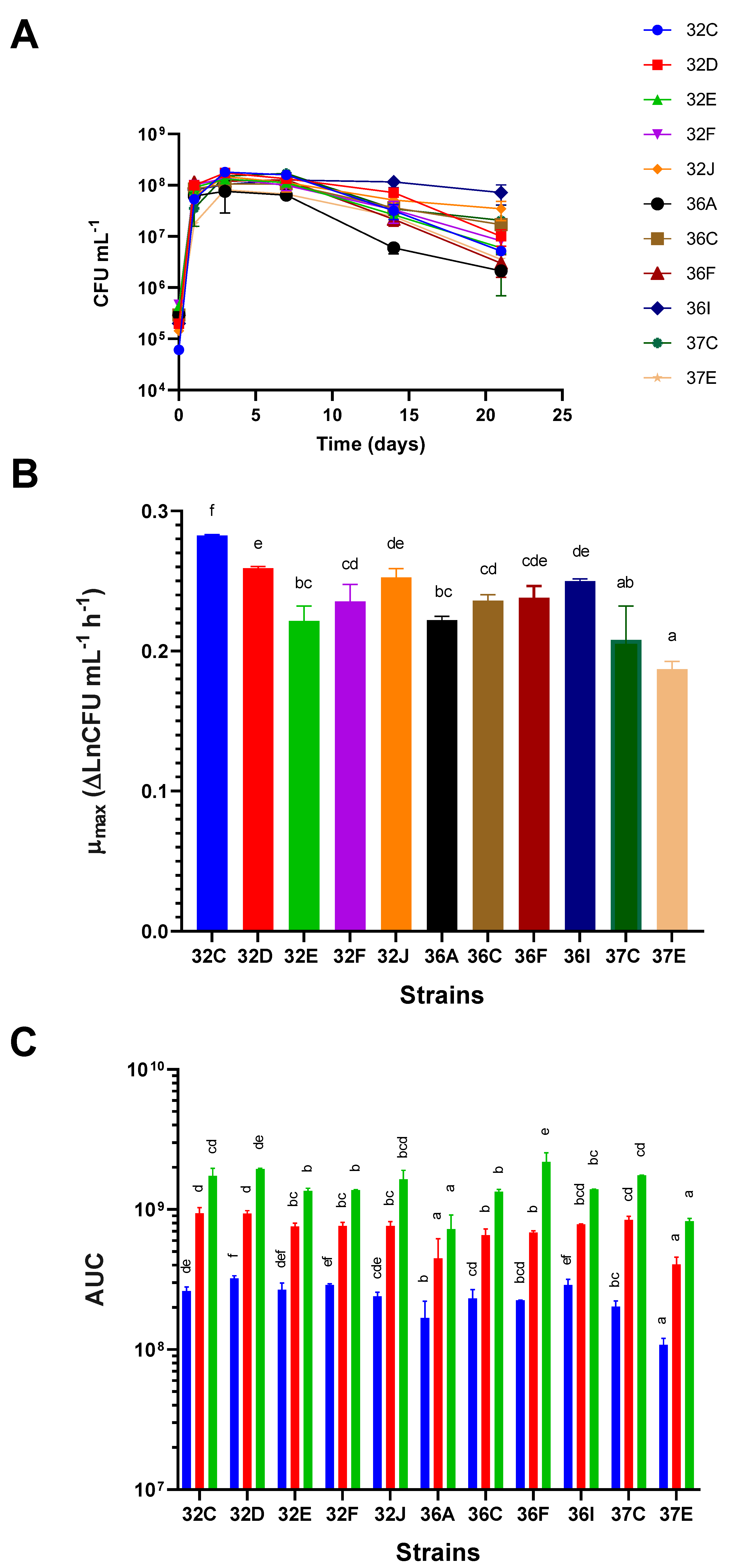

Yeast strains showed different abilities to grow in terms of their growth kinetics, μ

max, and AUC at different growth time points. Differences in the growth kinetics of the several yeasts were recorded (

Figure 2A), and they were related to different μ

max, maximum viable cell concentrations at the end of the logarithmic growth phase, and different behavior in the stationary and death phases (

Figure 2A). The strains with higher μ

max were 32C, 32D, 32I and 36J, whereas the slower ones were 37E, 37C, 32E and 36A and in increasing order. Significant differences were found between 32C and the other strains (

Figure 2B). When considering the AUC values at 3, 7 and 21 days as measures of overall growth at these time points, we observed that, despite the contemplated time points (poor growth abilities), the yeasts with significantly lower AUC values were 36A and 37E. The strain with the highest AUC values at every time point was 32D (good growth abilities), although differences were not significant with some other strains. Other strains, such as 32F and 36I, had highest AUC values at 3 days, but did not stand out at later time points (

Figure 2C).

For the glucose and fructose consumptions at the end of the experiment (21 days from inoculation), differences between strains were minimal, especially for glucose (

Figure 3A and 3B). At this time, the strains that consumed larger quantities of fructose were 32C, 37C, 36C, 32D and 32D (in decreasing order), and those that consumed significantly less were 37E and 36A (

Figure 3B). The bigger differences in both sugar consumptions were observed on day 3, but differences became slighter later (

Supplementary Figures S1 and S2). On the 3 first days, the most glucose-consuming glucose strains were 32F, 36I, 32D and 32E (in decreasing order), and the least glucose-consuming ones were 37E, 37C, 32C and 36F (

Supplementary Figure S1A). After 7 days, strains 32C, 36I, 37C, 36C and 32F had consumed the largest quantities of glucose, while 37E, 36, 32E and 36A had consumed the least (

Supplementary Figure S1B). At the end of the experiment (21 days), glucose consumption was similar for all the strains (

Supplementary Figure S1C). Bigger differences in fructose consumption were found: after 3 days, the strains that consumed the largest fructose quantities were 32C, 32F, 36F and 36I, while 37E and 32J consumed the smallest (

Supplementary Figure S2A). On day 7, 32C remained the most fructose-consuming strain (

Supplementary Figure S2B). On day 21, 32C, 37C and 36C were the most fructose-consuming ones, while the least fructose-consuming ones were 37E, 36A and 32J (

Supplementary Figure S2C). After 21 days of fermentation, the residual glucose concentrations varied between 0 and 1.1 g/L, whereas that of fructose ranged from 0 to 10.2 g/L, which revealed the glucose preference for the majority of our

S. cerevisiae strains, as previously stated by several authors [

49,

50]. High residual fructose concentrations increase the risk of microbial spoilage [

49] for being a substrate that supports the growth of detrimental

Brettanomyces bruxellensis or lactic acid bacteria.

The strains that produced the largest ethanol quantities at the end of the experiment were 36C, 37C, 36I and 36F (in decreasing order), whereas those producing the smallest were 32J, 37E, 32F and 36A (

Figure 2C). However, this ranking varied with time. The strains that produced the largest ethanol quantities on the first 3 days were 32C, 32D, 32E and 36F, while the strains that produced the smallest ethanol quantities were 37E, 36C and 36I (

Supplementary Figure S3A). Interestingly, 36C was the most ethanol-producing strain at the end of the experiment (besides 37C and 36I), whereas 37E remained the least ethanol-producing strain over time (Supplementary Figures S3B and S3C).

The strains that produced the highest glycerol concentration at the end of experiments were 36F, 32C and 36I, whereas those producing the lowest glycerol concentration were 32D, 37C, 32F and 32E (

Figure 2D). Regarding their production time point, 32C and 36F were the highest producers, while 32E and 32F were the lowest producer no matter what the fermentation time point was (Supplementary Figures S4A-S4C).[

51] described that the maximum glycerol release in synthetic grape must occurs in the decay phase for

S. cerevisiae and

Saccharomyces paradoxus. However in our case, the maximum increase took place after the first 3 days. Glycerol synthesis was the consequence of the NADH/NAD

+ imbalance at the beginning of AF, when enzymes pyruvate decarboxylase and alcohol dehydrogenase are not fully expressed and NADH cannot be re-oxidized by the alcoholic fermentation pathway. In this circumstance, NADH re-oxidation is achieved by reducing dihydroxyacetone-P to glycerol-P, which is finally dephosphorylated to glycerol [

52,

53]. [

53] described how the differences in glycerol production between strains could be due to either distinct activities or concentrations of key enzyme triose phosphate isomerase, which catalyzes the triose phosphates interchange.

The strains that yielded more acetic acid after 21 days were 36C, 36I, 32D and 37E, whereas those that produced less were 32C, 32E, 32F and 36A (

Figure 2E). When we took into account the fermentation time point at which strains produced the most acetic acid, strains 36C, 36I and 32D stood out as being the highest producers, while strains 32C, 32E and 32F were the lowest throughout fermentation (Supplementary Figures S5A-S5C). Differences in acetic acid production were possibly related to strains’ distinct acetyl-CoA synthetase capacities. Hence this enzyme’s poor activities caused acetate overflow [

53]. In relation to yields, strain 37E generated a significantly lower yield on day 3, whereas no significant differences were found among strains 32F, 36A, 36C and 36I, nor among 32C, 32D, 32E, 32F, 32J, 36A, 36C, 36F and 37C (Supplementary Figures S6A). Differences between strain yields became bigger as fermentation progressed. Significantly lower yields were recorded for strain 32J on day 7, and for strains 32J and 37E on day 21 (Supplementary Figures S6B and S6C).

When bearing in mind the growth and metabolic traits, strain 32C was one of those that produced less acetic acid, more glycerol and moderate ethanol. It also displayed high fructose and glucose consumption. This strain obtained a high μmax and AUC, and maintained a high viable cell concentration for up to 21 days from starting fermentation when grown in sterile Cabernet Sauvignon grape must.

3.3. Correlation Analysis

The Spearman correlation analysis was applied to the growth- and the metabolism-related data obtained on days 3, 7 and 21. On day 3, the AUC correlated significantly with the μmax,

consumed glucose and fructose, and ethanol production, whereas μ

max only showed a significant correlation value with AUC (

Supplementary Table S1). Significant correlation values were found between glucose consumption and glycerol production, but not for consumed fructose. Glycerol synthesis occurs mainly at the beginning of AF when enzymes pyruvate decarboxylase and alcohol dehydrogenase are not fully expressed [

52,

53]. In line with this statement, in our experiments larger amounts of glycerol were produced at the beginning of AF (

Supplementary Figure S5). The discrepancy in glucose/fructose utilization might be related to fructose phosphorylating activity at physiological fructose levels

in vivo, and could explain

S. cerevisiae preferring this hexose [

54]. Ethanol production correlated with AUC, μ

max, and fructose consumption, but not with consumed glucose. This might seem strange, but [

55] reported that their statistical data analysis evidenced that an increase in or change to the amount of consumed glucose or fructose did not cause the same increase in or change to the amount of produced ethanol. On day 7, the significant correlations were the same as on day 3, except for ethanol production, which did not correlate with the other parameters (

Supplementary Table S2). At that time, the correlation values between glucose and fructose consumptions were significant. On day 21, significant correlation values were found between: μ

max, and consumed glucose; μ

max and AUC; glucose and fructose consumptions (as on day 7); consumed fructose and ethanol production (

Supplementary Table S3). The correlation between fructose consumption and ethanol increase was logical because glucose was almost exhausted on day 7 and, hence, ethanol was produced exclusively from residual fructose. Neither glycerol nor acetic acid production correlated with any of the other parameters at any fermentation time point. A positive correlation was expected between μ

max and both glucose exhaustion and ethanol production because

S. cerevisiae obtains energy for growth from sugar fermentation (two ATP moles per glucose mole) [

53]. Hence the higher alcohol production and glucose consumption are, the faster cell growth is. The correlation values between these parameters lowered as fermentation progressed, which is a logical trend because μ

max affected mainly AUC on day 3, whereas the AUC corresponding to later time points reflected stationary phase behavior. Although μ

max should be considered one of the main criteria for selecting a starter for alcoholic beverage industries, despite some strains having a high μ

max, they were neither the highest glucose consumer nor the biggest ethanol producer.

3.4. Physico-Chemical Characteristics of Small Scale-Produced Cabernet Sauvignon Wines

The eleven microvinifications were completed in triplicate for each yeast strain, as explained in the Materials and Methods section. Wines were analyzed after 2 months of bottling when MLF had ended, which did not end at the same time in all the trials.

The composition in the physico-chemical parameters is shown in

Table 2, which reveals that significant differences appeared in all the analyzed parameters (p value <0.05), except for density. The density values did not cause statistically significant differences because all the wines had been completed. The density of 993-992 was reached 10 days after fermentation began, which was carried out at a temperature between 22-23 ºC.

All the tested yeasts had completely consumed sugars; the residual sugars in wines ranged between 2.20 and 2.70 g/L, which is consistent with those usually reported for wines [

56]. The volatile acidity of wines 2 months after EAF was acceptable in all the tests [

57], with significant differences (p <0.05) and the lowest values corresponding to the wines obtained in strains 32E and 37E with volatile acidity values close to 0.4 g/L acetic acid. The rest had acceptable values with maximums of 0.66 g/L (strain 36C). Discarding strain 36C was not a considered criterion because it fell within the normal wine values after AF and was less than acetic. Additionally, although significant differences for the pH values appeared, they were all adequate for avoiding subsequent microbiological problems. For the values obtained for titratable acidity, the strains of profiles 32C, 32D, 32E, 36F, 37C and 37E still had values above 7 g/L (tartaric acid), which is an ideal situation, especially if they are to be used in hot climates. Wine acidity and pH affect color, taste, oxidation degree, etc. [

58]. Significant differences appeared between yeast strains in relation to alcoholic yield because alcoholic graduations between 13.2% and 14.1% were obtained. They are related, on the one hand, to the slightly unavoidable heterogeneity between the raw material of vinifications and, on the other hand, to different sugar/ethanol yields. 32C, 32E and 32F can be used for those vintages for which glycometric maturity is insufficient due to adverse climate circumstances because they provide higher alcoholic yields. Finally, 32J, 36F and 36I can be used in hot regions. Indeed [

14] discovered one yeast that produced higher acid content during AF.

The color-related compounds are listed in

Table 3 at 2 months after MLF ended, along with the 11 selected yeasts. Upon analyzing the obtained results, significant differences were found in CI (p value <0.05). Yeast strains 32C, 32F, 36A and 37C were those whose values remained around 11. Conversely, the lowest CI level was detected in the wines produced by yeast strains 32D, 36F and 37E, which gave less colored wines (8,92-9,15). This can be explained by possible color adsorption by the cell walls of yeast strains due to the presence of enzymes with β-glucosidase activity that cause the β-gluglycosidic bond between an anthocyanin and sugar to break down by releasing anthocyanins and making them more oxidizable [

59,

60]. In addition, a drop in CI is related to the adsorption capacity of anthocyanins by yeast walls[

61]. A low Hue level indicates less oxidation [

62] and is, therefore, desirable in wines. The Cabernet Sauvignon wines fermented with yeast strains 32C, 36C and 37C had the lowest Hue level (< than 60), mainly because the red color concentration in these wines was higher (A

520) compared to the yellow color (A

420). The highest concentration of anthocyanins corresponded to 32C and 32F, both from the total anthocyanins (648-676 mg/L) and colored anthocyanins (487-494 mg/L), and yeast strains 32J and 36C also displayed good behavior in relation to anthocyanins.

For the color-related compounds in wines, it is important to select a yeast strain that provides a high CI level, accompanied by a large amount of total anthocyanins, preferably if they are colored anthocyanins, to obtain wine with more color that remains stable over time [

63]. The yeast strains that accomplished fermentation had a strong effect on polyphenols, and modified not only polyphenolic content, but also the state and stability of polyphenolic compounds in wine [

64,

65,

66,

67]. Anthocyanins appear in wines in the free form and are combined with other compounds, mainly tannin molecules. Free anthocyanins are those with more color, the reddest, but are more unstable are colored by SO

2. Their color varies depending on pH. Furthermore, most combined anthocyanins (colored) are insensitive to discoloration and are stabler over time [

68]. Yeasts contribute to the stabilization of coloring matter during the fermentation process due to their ability to synthesize carbonyl compounds, such as acetaldehyde and pyruvic acid, which can act as precursors of the formation of pyranoanthocyanins, which are stabler molecules over time and not discolored by SO

2, and favor condensation between anthocyanins and tannins [

67,

68]. The release of both pyruvic acid and acetaldehyde varies according to yeast strain [

63,

67]. In the present work, yeast strain 32C provided a high CI level in wines with a higher concentration of colored anthocyanins, which made them stabler over time. Therefore, it could be stated that strain 32C was the best in terms of color parameters in the Cabernet Sauvignon variety.

Table 3 shows the results obtained from the tannic composition of the wines made with the different selected yeast strain profiles. Proanthocyanidins are responsible for bitterness and astringency. Thus tannins confer astringency and structure by complexing with saliva proteins [

69], and they also act as antioxidants. The tannin concentration of the obtained wines was between 2.12 and 2.53 g/L, values which correspond to wines with high tannicity due to the optimum grape maturity state, with alcoholic degrees in wines between 13.2 and 14.1 (as shown in

Table 2). It must be taken into account that the temperatures reached during fermentation (22-23ºC) did not allow a similar tannins extraction concentration to that obtained with temperatures close to 28ºC, which is employed in usual vinifications. The obtained alcoholic degree and fermentation kinetics determine tannins extraction from grape skins because wines were devatted and pressed at the same time. Therefore, those strains that managed to ferment more quickly achieved greater tannins extraction. The differences in the tannin concentration of the different wines could be caused by slight variations in raw material or be due to differences in fermentation kinetics because, ethanol must be present in the medium for tannins extraction.

Statistically significant differences (p <0.05) were found between wines in all the analyzed compounds (see

Table 3). The highest concentrations of condensed tannins corresponded to the wines fermented with yeast strains 32C, 32F, 32J and 36I. For the tannins related to catechins concentration, performance was the opposite because, at the same time that tannins form by polymerization of catechins, their concentration drops [

70]. Minimum catechins concentrations contribute to reduce the bitterness of wine [

6,

71]. All our wines had low catechins concentrations (0.1 g/L). The DMACH Index is a measure of the mean degree of tannins polymerization with an inverse reading [

29]. The tannins with the highest polymerization degree appeared in the wines fermented with yeast strains 32C, 32F, 36A and 36I (16.81-21.56 %).

The Ethanol Index is the percentage of tannins that can combine with wine polysaccharides (see

Table 3). It assesses the tannins-polysaccharides combination and is very favorable for wine quality. The wines with the most polymerized tannins were yeast strains 32C and 36I, and also with a higher Ethanol Index (58.2-59.1), which indicates a higher proportion of tannins combined with wine polysaccharides. Possibly the strains that contributed to a high Ethanol Index level possess marked β-glucanase activity, which would increase the presence of wine polysaccharides during their autolysis, which originate in the cell walls of these yeast strains [

72]. [

73,

74] have shown that different

S. cerevisiae strains lower the content of flavonols, total tannins and the tannins responsible for astringency in wines by influencing the chemical state of anthocyanins and tannins insofar as the greater their reactivity, the more compounds that are lost, and such reactivity decreases with its polymerization. Furthermore, yeasts produce polysaccharides from their cell wall during fermentation and aging on lees due to autolysis processes, which varies depending on the nature of the yeast strain [

72,

75,

76]. These polysaccharides react with the astringent tannins by polymerizing them, reducing the astringency sensation [

71] and also favoring lactic bacteria growth.

Regarding the parameters related to total polyphenols and condensed tannins, and their quality, the wine fermented with yeast strain 32C gave rise to not only wines that better maintained their polyphenolic and tannic concentration, but also to those with the best quality tannins, because they were those that most polymerized one another, and also with polysaccharides.

3.5. Wine Aromatic Compounds

Among fermentative aromas, a distinction is made between the aromas synthesized by yeast and those revealed from non aromatic precursors by yeast. The first of them is synthesized during yeast metabolism from the nutrients present in must and is then released to wine. The latter is released by enzymatic hydrolysis processes through the action of yeast from the precursors present in must in a non volatile form because they are bonded to large molecules. The latter depend mainly on the grape variety used to make wine, which is why they also form part of the varietal aroma [

77]. Aroma compounds confer wine its typical odor. The

S. cerevisiae strain represents one of the most important factors to affect wine fermentative volatile composition [

78].

Wine aroma is one of the main characteristics to determine wine quality and its value. Different

S. cerevisiae strains can affect wine aroma [

73,

78,

79]. More than 1000 aroma compounds have been detected in wine, including alcohols, esters, fatty acids, aldehydes, terpenes, etc. [

80]. The volatile compounds synthesized by wine yeast include higher alcohols, medium- and long-chain volatile acids, acetate esters, ethyl esters, aldehydes, among others. The capacity to form aroma depends not only on yeast species, but also on the particular strain of an individual species [

81,

82,

83].

Yeasts and their influence on the chemical composition of wines have been proven by studying fermentations which, by being carried out by different

S. cerevisiae strains and using the same must, show wide variability in the generated compounds [

84,

85,

86,

87].

The aroma composition and the ANOVA analysis results are shown in

Table 4. As we can see, yeast had a significant effect on the concentration of the different families of volatile compounds in wines. This effect differed depending on the type of analyzed compound.

The main types of fermentation aromas synthesized by S. cerevisiae are volatile organic acids, higher alcohols, esters and, to a lesser extent, aldehydes. Ketones and aldehydes are formed from either the oxidative degradation of sugars and amino acids, or the oxidation of corresponding alcohols. Aldehydes are the main source of herbaceous components in wine.

Moderate concentrations of higher alcohols contribute desirable complexity to wine aroma [

88]. Due to the close relation with yeast metabolism, the contents of higher alcohols in wine represent important variables for yeast strain differentiation and can be used as a basis for selection [

78]. Alcohols are formed from the degradation of carbohydrates, amino acids and lipids [

89]. It would appear that yeast strains formed a considerable amount of higher alcohols in the wines from the Cabernet Sauvignon variety (124-224 mg/L). Substantial amounts of isoamyl alcohol (mean values of 11-33 mg/L) were formed by yeast. The lowest level was detected in yeast strain 37E, with the highest level for 32E and 36F.

2,3-butanediol originates from the reduction of acetoin and its impact on wine aroma is limited [

90]. The tested yeast strains produced very low concentrations of this compound. However, 2-phenylethanol is a glycosylated aromatic precursor synthesized in grapes and subsequently released by either enzymatic action or acid hydrolysis [

90]. Unlike the other high alcohols in wine, it is characterized by its pleasant rose petals aroma [

83]. The yeast strains with the highest concentrations synthesized in wine from the Cabernet Sauvignon variety were 32C, 32D, 32F and 36A.

Regarding the lactones concentration, yeast strains 36F and 32C produced the highest level, and this effect was statistically significant for some studied strains. This effect is important because γ-lactones contribute to the peach aroma in some red wines [

91,

92].

Esters were the second most abundant class in terms of the number and concentration of volatiles. Ethyl esters of fatty acids are synthesized during fermentation, whose concentration depends on sugar content, fermentation temperature, yeast strain and aeration degree. Esters (including acetate esters and fatty acid ethyl esters) are important aroma compounds that positively contribute to the desired fruit aroma characters of wine. Ethyl acetate, ethyl octanoate, ethyl decanoate and ethyl decanoate can positively contribute to a wine aroma's sweet, floral, fruity and pleasant odor. In addition, all microvinifications contain low ethyl acetate levels which, when below 15 mg/L, play a positive role in wine quality [

15].

The fact that strains 32C and 32F produced the highest total esters concentration in the prepared wines is important because their total concentration is a possible indicator of fruit aroma because there are synergistic effects between the compounds from the same chemical family [

93]. 2-phenylethyl acetate, caused by the esterification between a molecule of acetic acid with 2-phenylethanol, is also interesting for the aromatic quality of red wine. 2-Phenylethyl acetate is characterized by a fruity, honey and rose aroma [

94,

95]. Microvinifications 32C, 32E, 32F and 36F contained the highest esters levels.

The wines fermented from the Cabernet Sauvignon variety with yeast strains 32C and 32F presented the highest volatile acids level (2.59 and 2.75 mg/L, respectively). Fatty acids are compounds that are considered unpleasant, but are aromatically important because they are the basis of fruity esters. The aromatic influence of these compounds has not yet been studied extensively compared to ethyl esters, although some (hexanoic acid, octanoic acid, decanoic acid, isovaleric acid) have been identified as chemical compounds with a strong aromatic impact in wine [

96,

97,

98]. Wines fermented from Cabernet Sauvignon with 32C and 32F yeasts have the highest concentration of volatile acids.

High acetaldehyde production can be a drawback for not only its aroma, but also its irreversible binding with SO

2, which leaves wine unprotected from oxidation and contamination by other microorganisms. Yeast strains 32E, 36A and 36F produced the highest acetaldehyde level, which is considered a drawback. However, yeast strains 32D, 32F, 36C and 37C were those that generated the lowest levels (

Table 4).

The wines fermented from the Cabernet Sauvignon variety with yeast strains 32C and 32F had the highest acids concentration, while those made with strains 36F and 32C had the highest lactones concentration. Strain 36A gave rise to the highest alcohols concentration and strain 37E produced wines with more aldehydes.

3.6. Sensory Profile of Cabernet Sauvignon Wines

Wines’ sensory profile was determined by a comparative sensorial analysis of the wines fermented with different yeast strains to select the

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain that could improve their organoleptic characteristics.

Table 5 shows that some descriptors were significantly influenced by yeast strain, aroma intensity and quality, red fruit and vegetable aroma. The wines with the highest sensory scores were those fermented with 32C in terms of color (intensity and quality, 8.2 points out of 10 in both cases), aroma intensity and quality (8.1 and 8.2, respectively), red fruit aroma (7.3) and vegetable aroma (1.7). In addition, the wines fermented with

S. cereviase strain 32F obtained the second highest scores by the sensorial panel, and had a similar intensity and quality aroma (8.4 in both cases) and vegetable aroma (1.1). The wines fermented by strains 36A, 36C and 36F scored high for aroma quality, red fruit aroma and vegetable aroma. Significant differences were found in aroma intensity, while aroma quality and red fruit aromas appeared to be related to sensorially favorable compounds; for example, ethyl esters, 2-phenylethanol, among others, which are related to flower and fruit descriptors. These compounds were possibly responsible for the differences noted in the scores for wine red fruit aromas, which falls in line with what [

4] and [

89] report. A lower concentration of vegetable aromas is desirable [

99]. Vegetable aromas are related to the presence of methoxypyrazines that are, in turn, related to grapes with a low degree of maturity [

100]. Nonetheless, they have also been related to the yeast strain employed during fermentation [

101]. Yeast strains can reduce the concentrations of juice and wine derived aromatic compounds through metabolic processes and sorption on the cell wall. The presence of vegetable aromas gave rise to significant differences among the tested yeasts (

Table 5). Nevertheless, no significant differences were observed for the other analyzed descriptors.

The sensory analysis disclosed that the highest-ranked wines were those fermented with strains 32C and 32F, based on good color quality and intensity, higher aroma intensity, aroma quality, red fruit aroma and lower vegetable aroma. The wines fermented with yeast strains 32C and 32F had the highest concentration of esters and lactone, which conferred wines a fruity character. Strains 32C and 32F are good candidates to improve the flavor complexity of commercial Cabernet Sauvignon wines and can contribute to increase the peculiarity of the Cabernet Sauvignon wines from this “Pago” winery.

3.7. Multivariate Data Analysis of Cabernet Sauvignon Wines

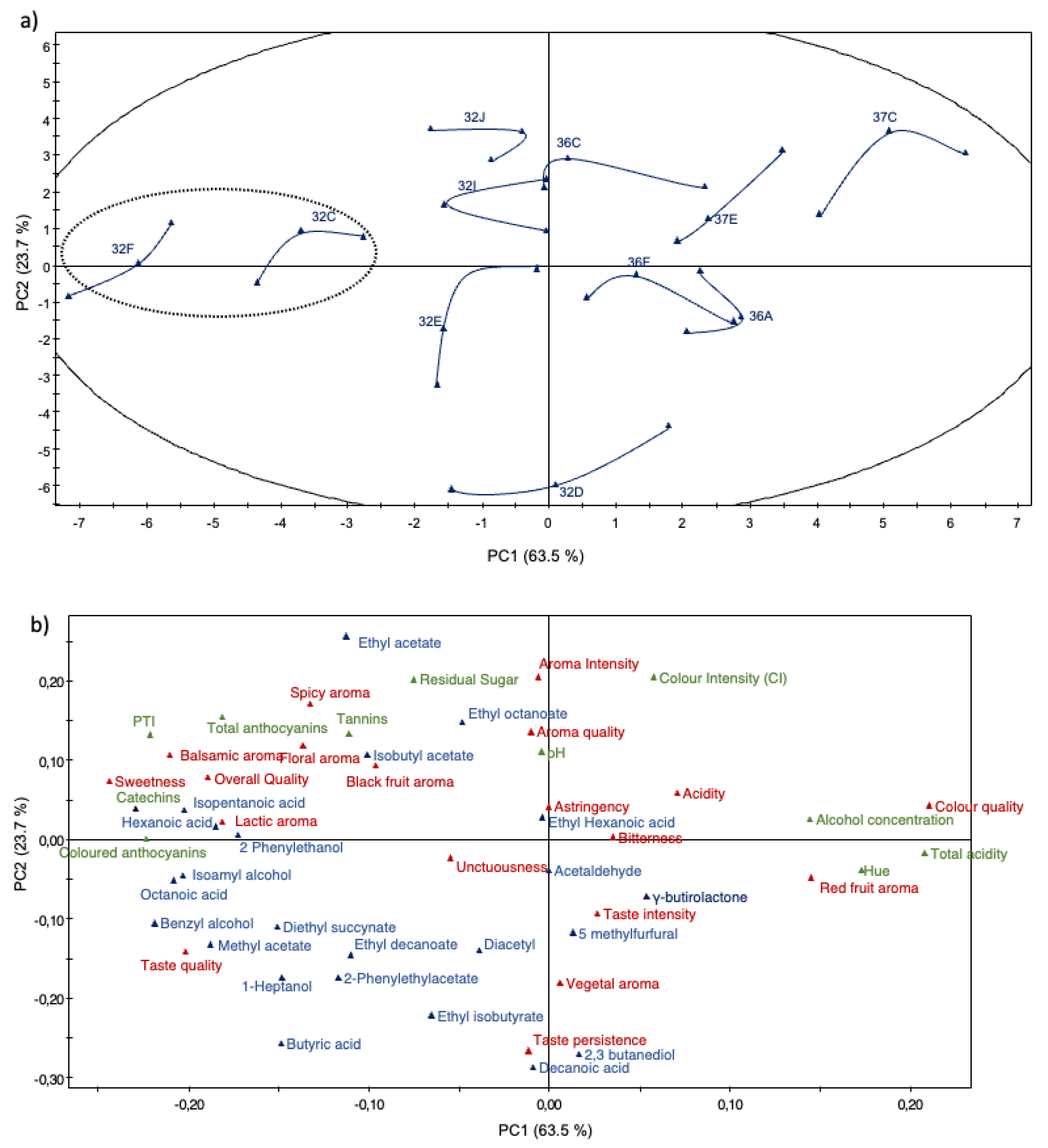

To better understand the relation between the wines fermented with the different yeast strains, a PCA on the 33 wines was performed using 64 variables (six physico-chemical parameters, 10 polyphenolic measurements, 23 volatile compounds concentrations and 25 sensory parameters). The corresponding loading plots establish the relative importance of the different chemico-sensory parameters in the plane formed by PC1 and PC2 (

Figure 4A). The PCA showed that the first principal components (PC1 and PC2) explained 87.3% of total variance. The first PC (PC1=63.5% of variance) correlated positively with acetaldehyde, γ-butirolactone, ethyl hexanoic acid concentration, taste intensity and red fruit aroma, and negatively with unctuousness, diacetyl, colored anthocyanins. The second PC (PC2=23.7% of variance) correlated positively with lactic aroma, black fruit aroma, astringency, bitterness and tannins concentration, and negatively with isoamyl alcohol and 2 phenylethanol concentration. The scores plot shows the distribution of yeast strains (

Figure 4A), and represents the arrangement of the different parameters on the plane formed by PC1 and PC2. On the scores graph (

Figure 4A), PC1 allowed wines to be separated into three groups. Strains 32F and 32C are on the left, 32J, 32I, 32E, 36C, 36F, 32D, 36F, 37E are in the centre of the coordinates and 36A and 37C are on the right.

The corresponding loading distribution of the wines fermented with yeast strains 37F and 32C lies to the left of the coordinate axis, and they are perfectly separated by PC1 and are related to sweetness, overall quality, lactic aroma, colored anthocyanins and total polyphenols, catechins and isopentanoic acid concentration. The wines fermented with strains 32J, 32I, 32E, 36C, 36F, 32D, 36F, 37E, lie in the centre of the coordinate axis, and show black fruit aroma, isobutyl acetate, diacetyl, 2-phenylethylacetate and acetaldehyde concentration, pH, aroma quality, unctuousness, color and aroma intensity. The loading graph indicates that the wines fermented with yeast strain 37C is separated from the other wines based on red fruit aroma, alcohol concentration, titratable acidity, red frit aroma, color quality and hue (

Figure 4B).