1. Introduction

Given the current Anthropocene era, there is a compelling need to embrace nature-based solutions as a means to address the increasingly pressing issues of climate change and biodiversity loss. In cities, improving green space areas has emerged as a crucial tool to mitigate the adverse impacts of rapid urban development. Urban green space, including parks, gardens, and green walls, contributes to cooling cities [

1,

2], enhancing urban health [

3,

4], supporting the economy [

5,

6,

7], and benefiting ecosystems [

8]. Psychological research also highlights the non-physical benefits of urban greenery, as green spaces with amenities can encourage outdoor activities and interactions among residents and, thus, reduce negative emotions such as sadness, fear, and stress arousal [

9,

10,

11]. Factors such as proximity, accessibility, size, spatial elements, and interpersonal interaction play significant roles in influencing the use of green areas.

Numerous international and national policies recognize the benefits of green space on individual and community well-being, all covered under the umbrella term ‘green urban agenda’. The United Nations' Sustainable Development Goal 11 aims at providing universal access to safe and inclusive urban green and public spaces by 2030 [

12].

New Urban Agenda [

13] emphasizes the need for compact, connected, and inclusive cities that prioritize environmental sustainability, green infrastructure, and the preservation and enhancement of natural and cultural heritage. World Health Organization encourages cities to adopt policies and strategies that prioritize health and well-being, including the provision of green spaces, active transport infrastructure, and measures to address environmental determinants of health [

14]. Many cities within the C40 network have adopted sustainability and climate action plans that include strategies to reduce carbon emissions, enhance green spaces, and improve urban resilience. Finally, the European Green Deal recognizes the importance of greening urban areas and promoting sustainable urban mobility, energy efficiency, circular economy practices, and nature-based solutions as part of the overall agenda [

15].

However, while these policy frameworks support the importance of green space provision for the overall quality of life, it needs more specific guidance on the green space attributes required to address individual and community lifestyles. This is partly due to the generalization of different types of green spaces in planning policies without considering their specific characteristics or quality [

16]. Using the case study of Zurich, Switzerland, and, more specifically, looking into the neighborhoods currently undergoing significant densification (hence posing a threat to green spaces), the study examines the extent to which ‘green urban agenda’ policy priorities have been implemented in practice. More precisely, attending to the physical green space attributes (e.g., location, size, connectivity, design, equipment), but also looking at the dominant activities in green areas and people’s behavior (as immaterial green space attributes), the paper offers a critical evaluation of the current practice of the green space planning and design, pointing to the main lessons learnt as a further direction for action.

The paper is structured as follows. The introductory section precedes a brief overview of the global and European territorial/urban planning policies highlighting the principles of the 'green urban agenda'. The paper continues with a brief explanation of the methodological strategy applied to then provide a multi-layered analysis of: 1) the national policy instruments, 2) green spaces in Altstetten-Albisrieden (distribution, types, size and mutual connectivity), and 3) selected four green space clusters and the dominant activities emerging there. The discussion unveils the relations between the priorities proclaimed in the policy framework and their implementation in practice. The conclusion highlights the primary lessons learnt and the limitations of the study.

2. Towards Green Cities: Overview of Meta-Trends

Informed by the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

12] as the overall framework and, in particular, SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities), SDG 13 (climate action), and SDG 15 (life on land), the following topical meta-trends are identified under the umbrella narrative of ‘green urban agenda’: a) green city, b) climate adaptation and mitigation, c) densification/infill development, d) resilience, and e) sustainable development [

17]. To operationalize the above rather abstract meta-trends,

Table 1 summarizes the findings from key global and European territorial/urban development policy documents published recently (i.e., within the last ten years), pointing out to the major principles in line with the meta-trends. Such an overview serves to provide the background information for a similar analysis done within the case study, i.e., a documentary analysis of multi-scale policy toolkits in Switzerland.

3. Methodology and Data

Examining the extent to which the principles ingrained into the ‘green urban agenda’ have been implemented in a specific case study's urban design and planning practice demands a three-fold methodological strategy. Firstly, it is necessary to situate the ‘green urban agenda’ narrative into the Swiss context of primary policy toolkits, i.e., to identify the central tenets used to reflect the previously introduced policy trends and associated major principles. Secondly, it is vital to examine green spaces – their provision, types, size, and mutual connectivity – in Zurich’s neighborhoods of Altstetten and Albisrieden. Lastly, informed by the previous step, it is crucial to determine green space attributes and dominant activities within smaller sites, i.e., the so-called green space clusters in the mentioned neighborhoods. The methods used in each analytical step have been presented in the following subsections.

3.1. Situating the ‘Green Urban Agenda’ Narrative in Switzerland

To situate the narrative on ‘green urban agenda’ in Switzerland, a multi-scale documentary analysis was conducted. Firstly, the most important, currently standing, strategic and regulatory documents (federals strategies, federal laws, cantonal structural plans, master plans and urban strategies) relevant for various territorial scales (federal, cantonal and municipal) have been identified including: strategic documents at the federal level –

Sustainable Development Strategy 2030 [

24],

Action Plan 2021-2023 for Sustainable Development Strategy 2030 [75],

Megatrends and Spatial Development in Switzerland [

26],

Trends and Challenges: Figures and Background on the Swiss Spatial Strategy [

27],

Swiss Spatial Concept [

28]; regulatory documents at the federal level – Planning and Construction Law PBG (2013) [

29], Spatial Planning Law RPG (2019) [

30]; strategic documents at the cantonal level –

Cantonal Structural Plan Zurich 2035 [

31],

Long-term Spatial Development Strategy of Canton Zurich [

32]; and strategic documents at the city level -

Regional Structural Plan [

33],

Communal Structural Plan [34}, and

Strategies Zurich 2035 [

35]. Secondly, the content analysis was conducted, attending to the principles previously identified in the global and European policies (

Section 2). Such an analysis aims to reveal to what extent the globally recognized ‘green urban agenda’ principles have been covered in various national documents.

3.2. Examining Green Spaces in Altstetten and Albisrieden

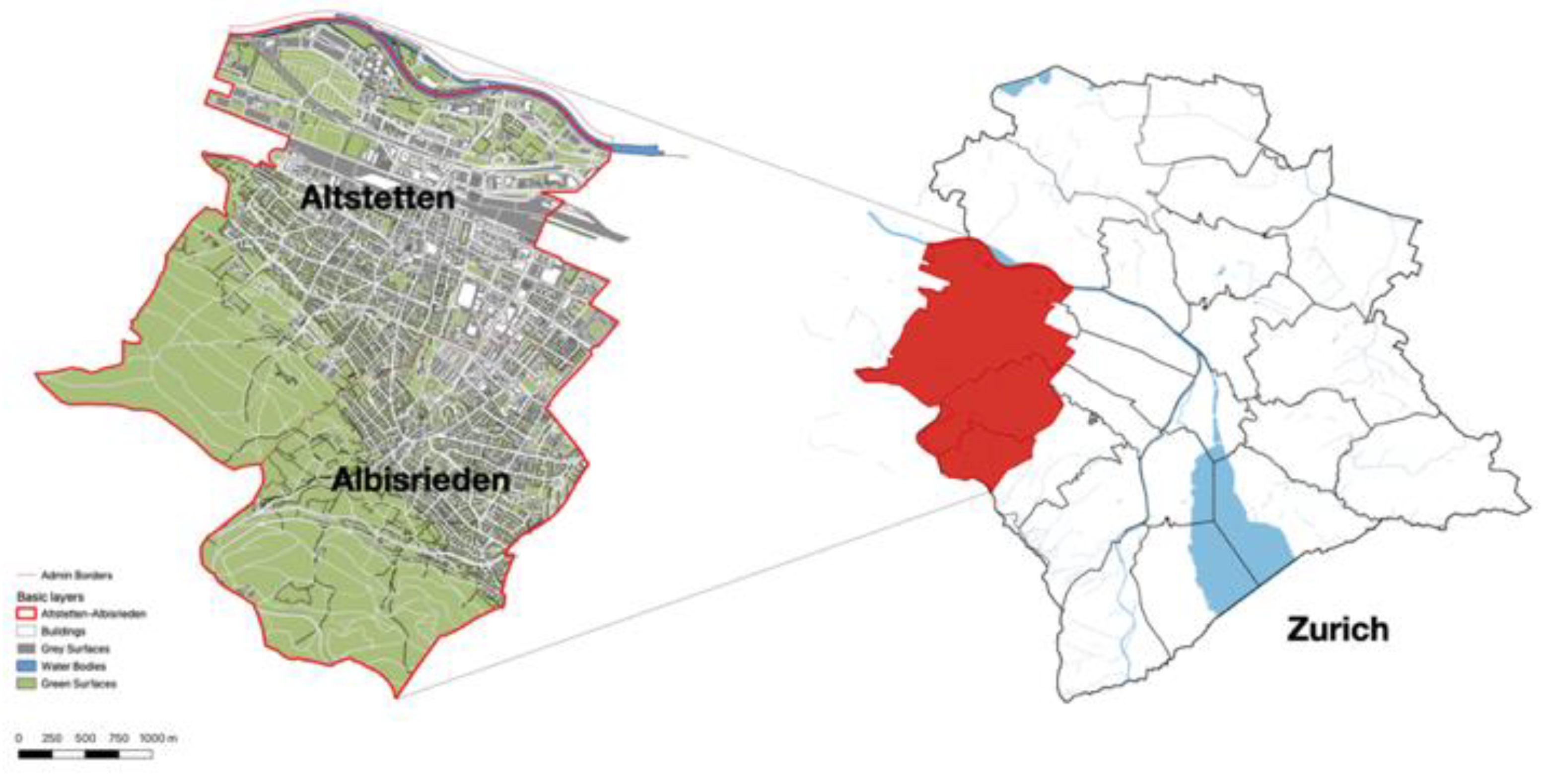

To examine green spaces in Zurich’s neighborhoods of Altstetten and Albisrieden (

Figure 1), a mixed-method approach was applied. Altstetten and Albisrieden have rich sources of greenery due to their natural geographic conditions. The large surface of closed-off woods, intensive agricultural fields, pastures, and residential green areas extend from the hill foot of Uetliberg in the south to the Limmat River in the north. Additionally, Altstetten and Albisrieden showcase building typologies and urban forms of different development ages. Community centers with farmhouses erected at the beginning of the 20th century, single-family houses and multi-family buildings constructed around the 1940s, and cooperative residential projects developed in the last decades, generate the diversity of urban fabric and greenery structures crossing the whole district. As a prominent residential district, the demographic composition of Altstetten–Albisrieden represents the overall situation of Zurich in terms of gender and age groups and provides various cultural and economic backgrounds. To examine green spaces in Altstetten and Albisrieden – their provision, types, size, and mutual connectivity – the following methods were applied.

To investigate green space provision, two measurement methods were applied: green surface ratio (GsPR), measuring the physical surface area of green space in each plot and demonstrating the provision of green space on the ground; and green plot ratio (GnPR), calculating three-dimensional greenery volume through Leaf Area Index (LAI), thus, indicating the greenery intensity of the site.

1 LAI values vary among plant types according to canopy shapes, density, plant structure, and measuring methods (

Table 2). This study deployed the general LAI values suggested by the National Parks of Singapore (NParks) as follows:

To classify green space, the geographic information on green space types from the open-source data, specifically Open Street Map of Zurich,

2 was used. Two additional parameters, ownership and accessibility, were incorporated. As a result, green spaces were categorized into four main types: 1) public green spaces – owned and maintained by the city and are accessible without restrictions; 2) community green spaces – the areas within neighborhood settlements shared and maintained by a particular community; 3) private green spaces – gardens belonging to individual households accessible only to household members or guests; and 4) other reserved green spaces – the areas restored for some particular use and functions. Some sub-groups were defined by management (for public green spaces) and function (for private and reserved green spaces).

To determine connectivity among various green spaces, the distance matrices and nearest-neighborhood tools in QGIS within the 800-meter radius were applied.

3.3. Identifying Green Space Clusters in Altstetten and Albisrieden

Informed by the previous analysis and to select representative green space clusters, the study applied a 400-meter (a 5-minute walk) radius to identify valuable connections and the area of subsite cases.

3 To analyze the use of space (i.e., dominant activities), on-site observation in the four clusters were applied. Photos and videos were used to record observed activities and interactions, which were then marked as point features in QGIS. The details of space users were transformed into variables associated with dominant activities in specific green space clusters, as shown in

Table 3. The observation covered all public green spaces, including areas with playgrounds or exercise facilities, as well as most community green spaces in the four cluster cases. However, due to restrictions on access permits and privacy concerns, activities in most private green spaces could not be observed. The observation periods were from 14:00 to 18:30 on weekdays and Sundays, chosen to ensure similar weather conditions and outdoor temperatures. Information such as language, age, gender, and user types were considered to facilitate the cross-case analysis of how green space attributes influenced the diversity of observed activities.

4. The ‘Green Urban Agenda’ in Zurich: A Multi-level Analysis

The following section presents the results of the analysis conducted at three levels: 1) policy analysis, covering a range of policy documents at different scales (federal, cantonal and local), with a particular outlook on the case of Zurich, 2) analysis of green space in Zurich’s district 9 (Alstetten and Albisrieden), and 3) analysis of green space use in the selected clusters of the mentioned district.

4.1. Situating the ‘Green Urban Agenda’ Narrative in Switzerland

The analysis of the core, standing strategic and regulatory documents through the lens of the ‘green urban agenda’ is presented in

Table 4.

The principles such as urban greening, combining high density areas with open spaces, protection of natural areas, and preservation of open and recreation spaces are spread across the range of the Swiss policies, including both strategic and regulatory instruments. Looking more closely to the local (city of Zurich) level, the following principles respond directly to green spaces and their attributes:

Preservation of city nature: This principle emphasizes the protection and conservation of natural elements within urban environments, including green spaces, urban forests, and water bodies. It aims to maintain and enhance biodiversity, ecosystem services, and the overall ecological health of the city.

High-quality open public spaces: This principle focuses on creating and maintaining high-quality open public spaces such as parks, plazas, and recreational areas. It recognizes the importance of providing accessible and well-designed spaces for social interaction, recreation, and ecological functions.

'Kurze Wege' (short distances): This principle promotes the idea of compact and connected urban environments where essential services, amenities, and facilities, as well as green spaces are within short distances from residential areas. It aims to reduce the need for long-distance travel and promote walkability, cycling, and public transportation.

Garden city: This principle draws inspiration from the Garden City movement, which promotes the integration of green spaces, landscaping, and planned garden areas. It also aims to create balanced and sustainable communities that combine urban living with the benefits of nature and open spaces.

Social inclusion coupled with natural preservation: This principle promotes the balance between the needs of the community and the enhancement of the natural environment, considering social equity, cultural diversity, and improving the quality of life as essential measures to boost the immaterial green space attributes.

4.2. Examining Green Spaces in Altstetten and Albisrieden

This subsection presents the results of the analysis of green spaces in Alstetten and Albisrieden, looking into their provision, type, size and connectivity.

Using the previous classification of green spaces (as introduced in the methodological section),

Table 5 indicates four types of green spaces, their main subtypes, and their size, as identified in the neighborhoods mentioned above.

The richness of green spaces in Altstetten and Albisrieden aligns with the urban development concept of a Garden City promoted since the beginning of the last century [

37]. This richness has been demonstrated from three perspectives. As shown in the table above, considering that the entire area covered by the district 9 is 12,068,034 m

2, it means that green areas of various types occupy almost 62 per cent (7,419,503 m2) of the entire district’s areas. The total resident population in the district amounts to 57,077 inhabitants [

38]

. On average, residents of Altstetten and Albisrieden can access more than 40 m

2 of green spaces. Besides 7.90 m

2 of collective spaces, such as parks, gardens, sports fields and traffic greenery, each resident can access more than 32 m

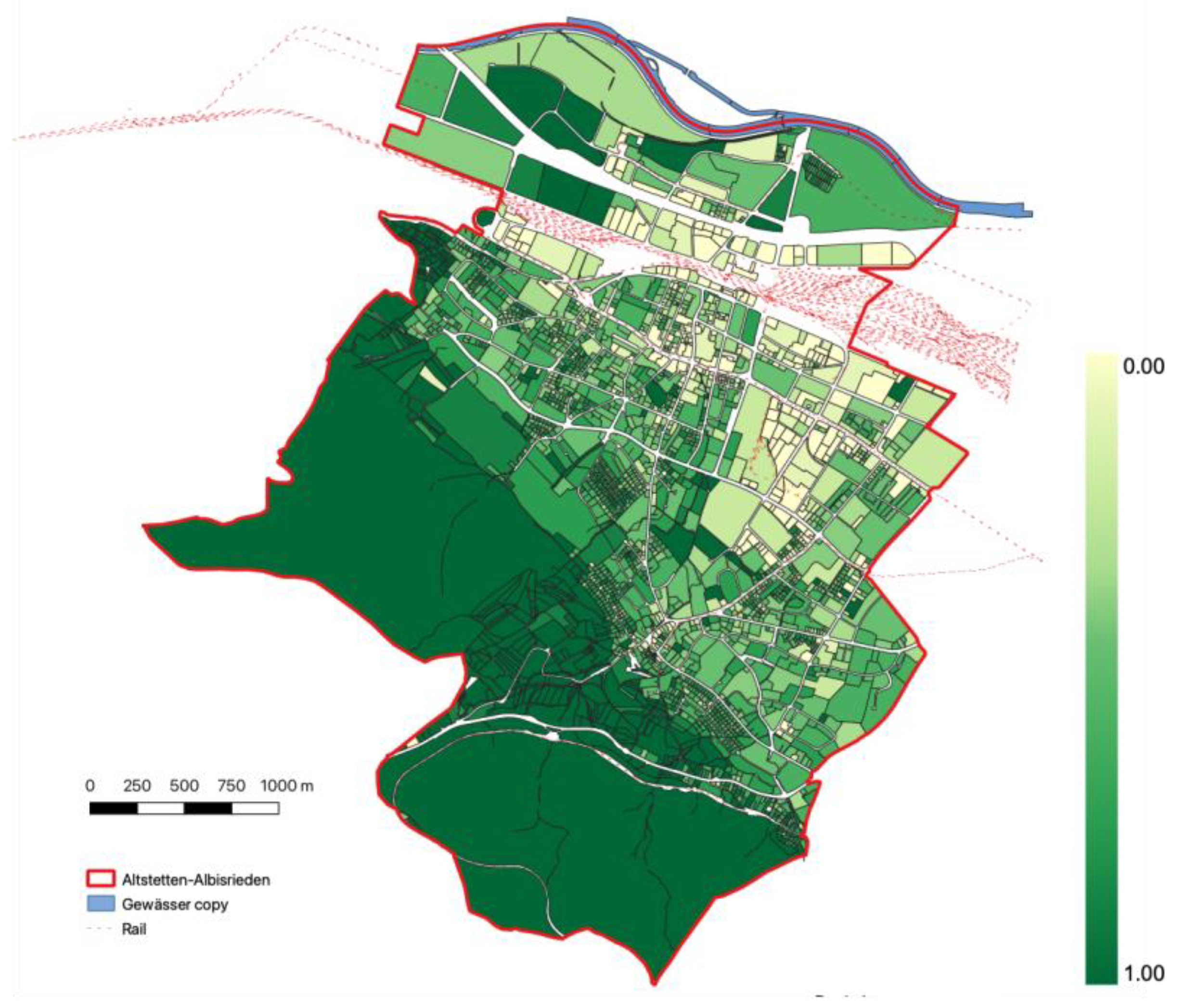

2 of green spaces near their houses for daily use. Except for intensively built industrial and commercial zones, development projects usually contribute more than 40 per cent of their site to greenery (GsPR > 40%) (

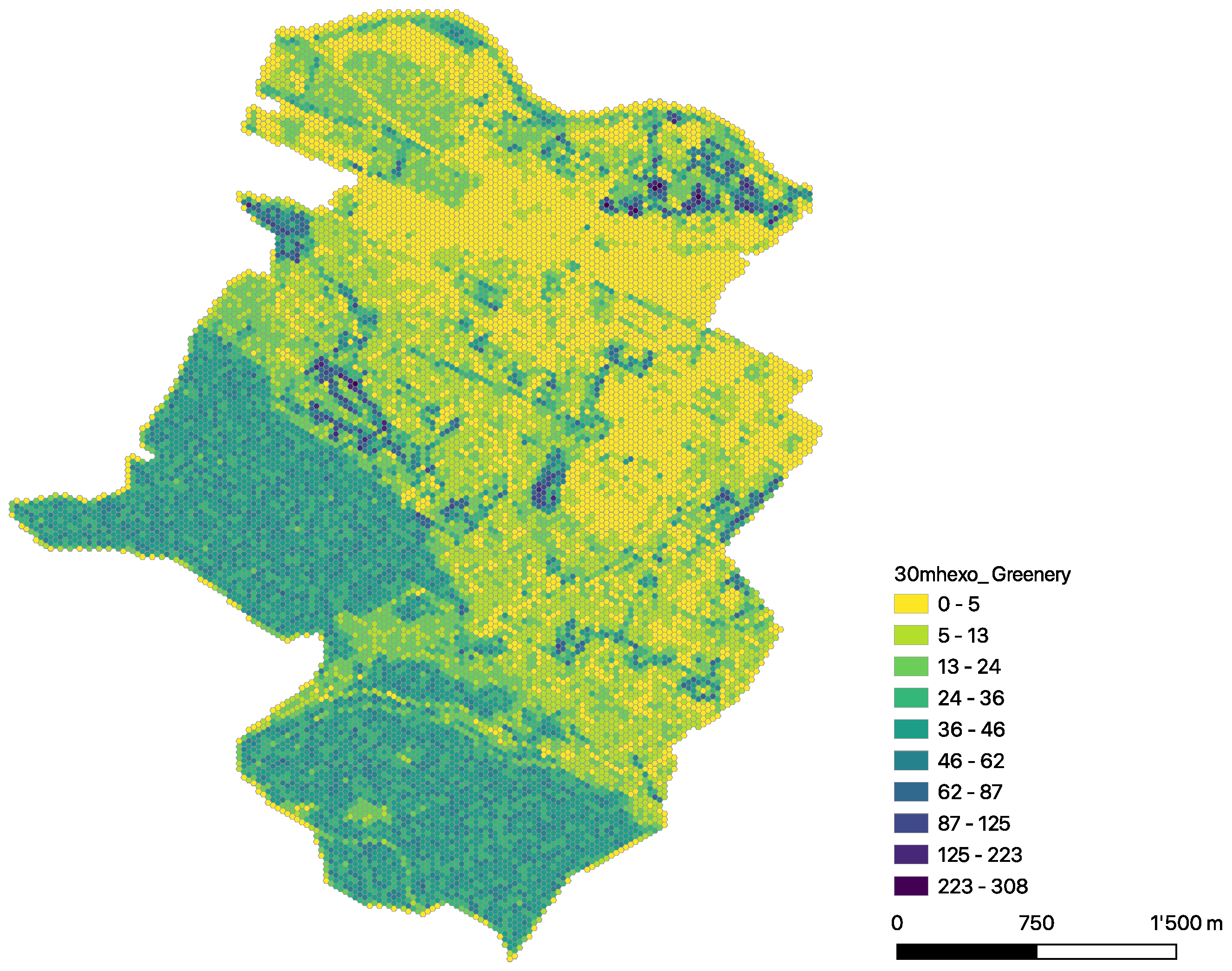

Figure 2). Given Leaf Area Index (LAI) as a factor to indicate the intensity of greenery, dense greenery extends and covers the whole residential area (

Figure 3). Public utilities, such as city parks, schools, and sports fields, are critical in providing high-quality greenery in the urban area.

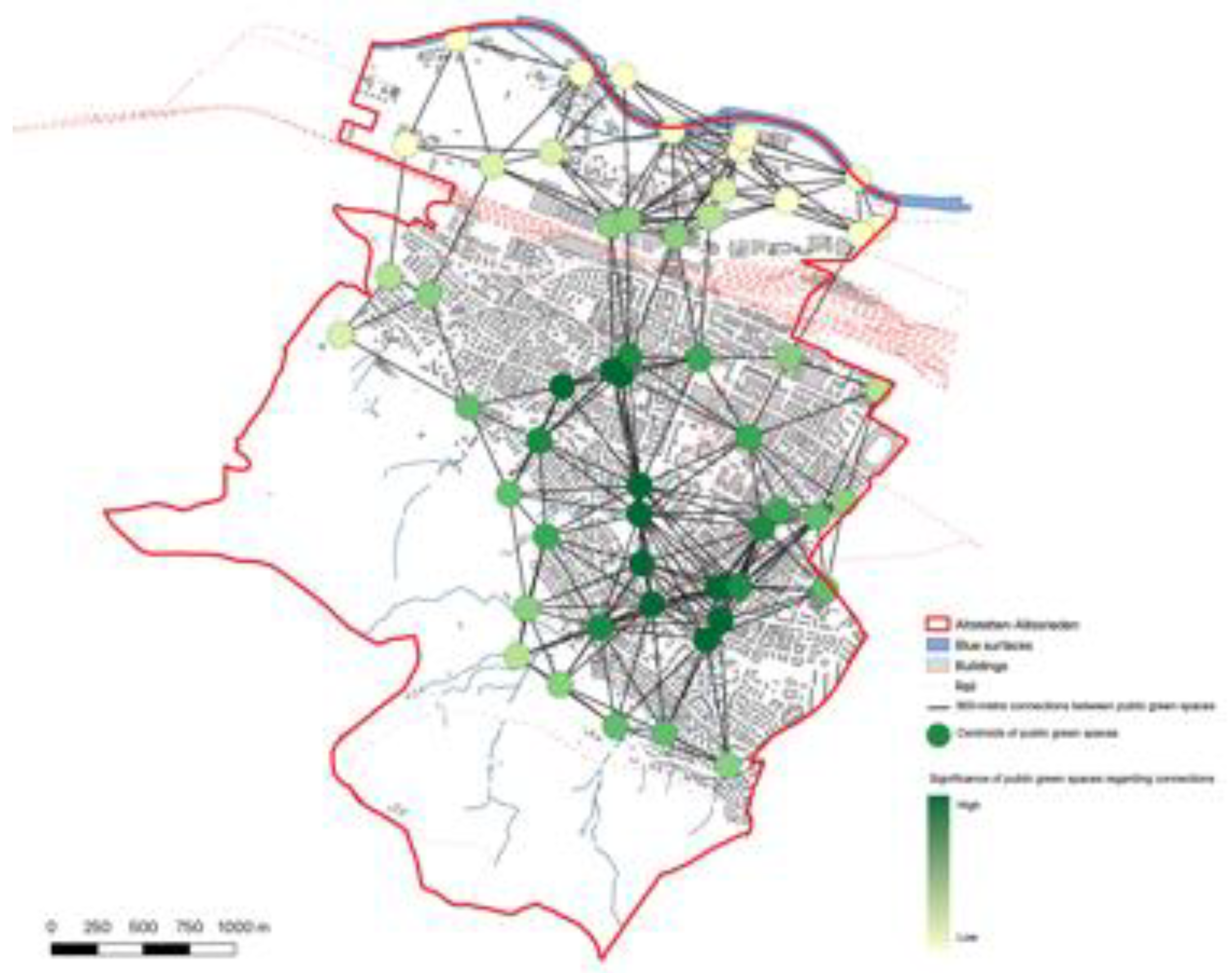

In terms of connectivity between the green spaces in Altstetten and Albisrieden, public green spaces are spread over the district so that residents can access at least one of these places within a ten-minute walk. People usually visit public green spaces on foot and rarely use community gardens in other neighborhoods. However, each community garden is equipped with similar facilities and furniture. These phenomena raised the space connectivity patterns consisting of space users’ paths as public–public, public–community, and public–private, as shown in

Figure 4. The centroids on the map symbolize individual public green spaces. The range of colors, progressing from yellow to dark green, indicates the varying number of connections linked to each centroid, ranging from fewer to greater connections.

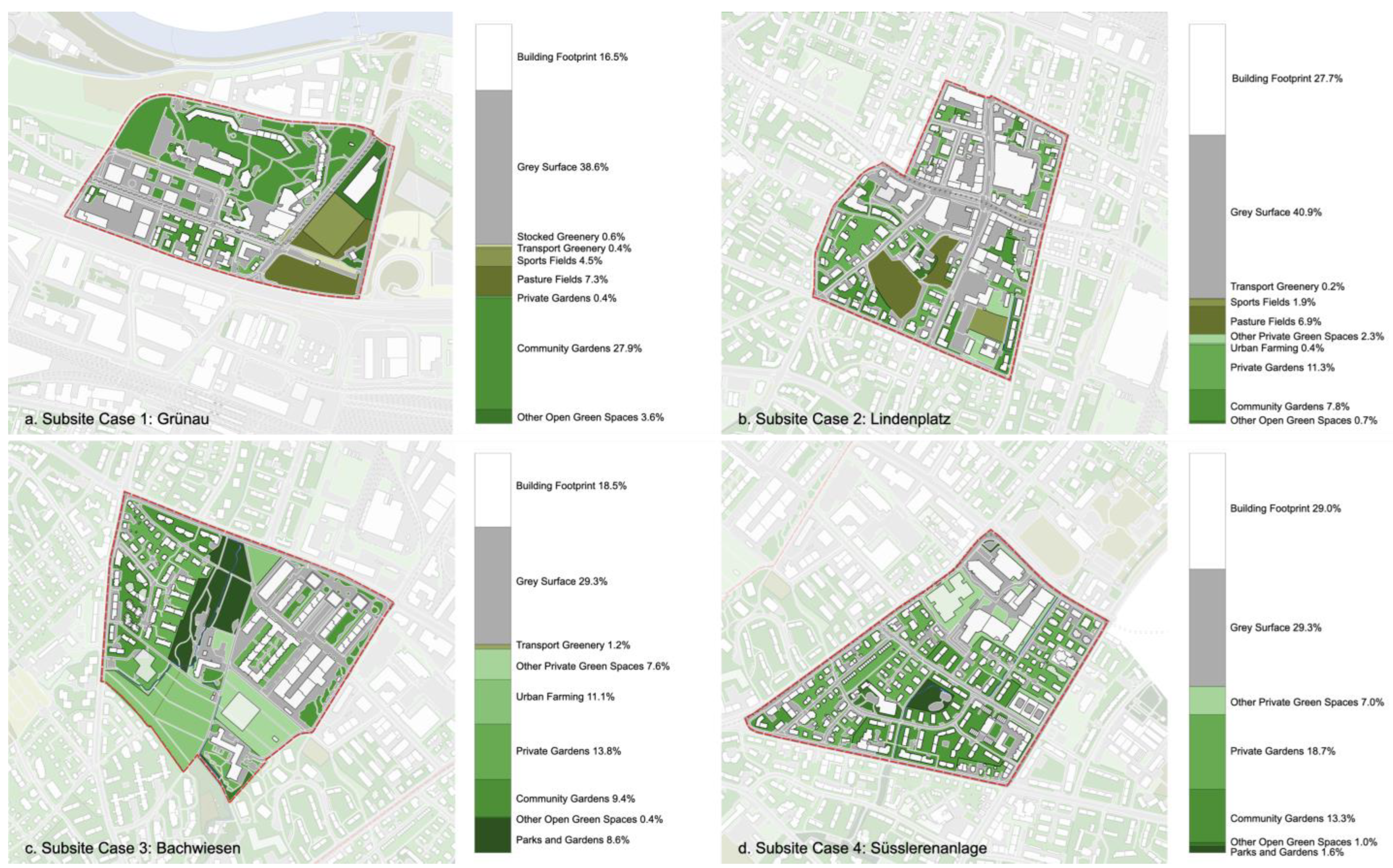

4.3 Identifying Green Space Clusters in Altstetten and Albisrieden

Based on the previous analysis, the collective paths leading to public green spaces highlight the significance of each space in the overall spatial arrangement of the urban area. Notably, public green spaces located in the central part of the district exhibit a higher number of connections, indicating the presence of four distinct clusters of green spaces with greater importance. Each cluster, namely Grünau, Lindenplatz, Bachwiesen and Süsslerenanlage, has one or more public green spaces in the center. Combined with physical boundaries, such as streets and property fences, these clusters and their 400-meter coverage areas shaped four cases (

Figure 5) for further study of the activities within these areas.

Grünau (

Figure 6-a) locates near the intersection between Europabrücke and the A1H Motorway and is close to the Limmat River. The area covers a large cooperative housing project called Grünau, a recent housing development, multi-family residential buildings, and public utilities, such as a primary school, nursing house, and commercial facilities. The green spaces in the area consist of the community garden of Grünau, some public open green spaces and a football field.

Lindenplatz (

Figure 6-b) has served as a cultural and commercial hub in Altstetten since the 1910s. This area encompasses retail establishments and residential buildings spanning up to six floors. Positioned in the central part of the area is a public square with paved surfaces, adorned with trees, and a spacious meadow near the Altstetten church is adjacent to it. A significant portion of the area's greenery is attributed to a substantial field situated across from the original community hall. Additionally, there are smaller green patches, including secluded courtyards, community gardens, and private gardens, scattered around the periphery of the area.

Bachwiesen (

Figure 6-c) contains the unique city park, Bachwiesenpark, and the green corridor linking the administrative zones of Altstetten and Albisrieden in the center. The area also covers one of the most significant high-density residential areas, Freilager, a multi-family housing neighborhood, and some urban farming fields. One-third of the green surfaces are used privately by communities or individual households.

Süsslerenanlage (

Figure 6-d) locates in the middle of Albisrieden. The urban fabric of the area is characterized by single-family houses, detached houses, and low-rise multi-family buildings. Nestled amidst these residential structures, there is a relatively small public garden located adjacent to the Neue Kirche (New Church) of Albisrieden. The majority of the green spaces in the area are comprised of community and private gardens, which often take the form of enclosed courtyards.

3.1.1. Activities in the Four Cluster Areas of Green Space

When applying the previously introduced pattern of variables associated with dominant activities in four green space clusters, the following findings have been derived (

Table 6).

Table 6 indicates the overall similarity between the clusters observed. In all the clusters, green spaces are larger than grey surfaces, except in Bachwiesen, where the grey surface is slightly larger. The distances to the buildings across clusters are similar, ranging slightly below 200 m, while only in Bachwiesen that distance amounts to ca. 215 m. In general, activities last 80 minutes in the observed areas, whereas in Grünau and Bachwiesen, people tend to stay half an hour longer than the other two clusters. Gender difference among space users is insignificant. The dominant users across clusters are mainly adults (30-60 years old) and children younger than ten, except in Lindenplatz, where adults are dominant users (61%). Across all the observed clusters, more than 90 per cent of space users enjoy green spaces with their families or friends, and a larger group of solo users (21%) is identified only in Lindenplatz. Swiss citizens contribute to over two-thirds, while people with various cultural backgrounds compose the rest of the observed population.

The main activities identified across the clusters are the following eight activities: resting, chatting, gathering (e.g., organizing events), playing, walking, walking dogs, exercising, and cycling. Their distribution (the total of 1,113 activities observed) across the clusters and per activity is indicated in

Table 7. More specific description of the activities identified in each cluster is given below.

In Grünau, casual football games and family gatherings around a high-rise residential tower dominate the space, while some short playing activities are scattered across some playgrounds around the case area (

Figure 7-a). Neighbors crossing an extensive age range gather to play football with children, chat with each other, or celebrate birthdays and similar family events (

Figure 7-b). Due to the high international profile of the Grünau neighborhood, cultural and social diversity prevail in the cluster, too.

Lindenplatz hosts many leisure and commercial activities due to its vital role in the district (

Figure 8-a). Cafetiere, restaurants and convenient shops attract people to stay for a rest, one hour on average. Youths prefer chatting, reading, or practicing music on the lawn next to the church for the whole afternoon. On Saturday mornings, local farmers and food producers hold a free market on the square (

Figure 8-b). The highest diversity of users is perceived in the open public (square) and green (park) spaces, while the community gardens accommodate mostly the local population.

In Bachwiesen, surrounded by several residential and one industrial zone, green space activities are concentrated in Bachwiesen Park (

Figure 9-a) and open spaces in the Freilager residential area, with more activities observed on weekdays than at the weekend. Large and various green space types (e.g., the park with meadows, playgrounds, a bird park, the community zoo, and the community club, connected by paths, bushes, and creeks; the Freilager area with the cycling and scooter paths and tennis courts) supported diverse activities for different ages, including also resting, suntanning, yoga, family gatherings, playing and cycling (

Figure 9-b). Most people come to the area with their families. As open to local residents and visitors from other parts of the city, the Bachwiesen area hosts the highest percentage of internationals.

In Süsslerenanlage, the size and type of green spaces differ from the other clusters due to the highest percentage of private gardens among green spaces. As a result, the entire area exhibits a tranquil and peaceful atmosphere, with a few individuals utilizing the public green spaces and spending less than an hour on average within these areas (

Figure 10-a). The users of these spaces are mostly acquaintances who share a closely-knit social background, and there is the limited promotion of cultural diversity (for instance, speaking in foreign languages tends to attract attention from the balconies and windows facing the green spaces). Young children use public green spaces more than adults (

Figure 10-b).

5. Discussion: The ‘Green Urban Agenda’ in Zurich – A Policy Proclamation or Real Implementation?

As introduced in Subsection 4.1, five main policy priorities can generally be grouped into three comprehensive groups. The first one covers the overall attitude towards natural environments; the other one covers the aspects related to the physical structure of green spaces (their size, main ecological features, equipment, design, and connectivity); the last group emphasizes the human aspect of the ‘green urban agenda’, i.e., how green spaces are used and by whom, highlighting the balance between urban lifestyles and natural environments. The critical evaluation of various aspects based on the previous analysis is given below.

Preservation of city nature. This implementation of this principle is starkly evidenced in the entire district 9. Namely, the area covered by Altstetten and Albisrieden has two natural borders: one of four Zurich’s hills – Uetliberg, stretches on the south side, while the Limmat River makes the natural border to the district on the northern side. The proximity of natural environments to urban areas is a secure way to protect biodiversity and ecosystem services. Looking more closely, Bachwiesenpark represents an excellent counterbalance to the densely built residential area of Freilager. Overall, many activities in observed green clusters, which are not considered famous for their attractiveness in the broader city area, indicate the generally strong bond of people to the natural environments.

High-quality open public spaces. The case study area and, particularly, four cluster green spaces indicate a wide variety of green areas within the observation perimeter. Public green spaces and community green spaces usually provide accessible and well-designed areas for diverse types of activities – from areas for relaxation to playgrounds. The variety and good quality of public equipment are particularly evidenced in the case of the Bachwiesen area, which contains the park (Bachwiesenpark), a large residential area (multi-family housing) and extensive community gardens. In contrast, Grünau, the cluster with the vast community garden (covering almost 30 per cent of the entire green areas in the cluster), is equipped with facilities serving for the smooth organization of events in open areas yet lacking well-designed and well-connected playgrounds. Namely, four playgrounds situated in Grünau’s at considerable distances from each other do not lead to an increased attraction of children or equitable distribution of users. Instead, one playground remains crowded, while the other three experience infrequent usage. The clusters with a higher percentage of private gardens (e.g., Lindenplatz and Süsslerenanlage) are characterized by less well-designed community gardens and public green spaces, although these spaces are mainly used for playing by younger generations. Activities that demand more active human engagement (walking, cycling, exercising) are not well-represented in any of the four areas except in Bachwiesen, suggesting that all other clusters may have to be better equipped with the appropriate facilities and surfaces (e.g., turf) specifically designed for the mentioned activities.

‘Kurze Wege’ (short distances). Observed through the lens of green spaces, the entire district area shows a satisfying implementation of the ‘short distances’ and ‘green corridors’ principles. This is particularly evident in the central district’s area with the highest connectivity rate among various green areas. City parks and other public green spaces are strategically distributed across the district, ensuring that residents can reach at least one such space within a ten-minute walking distance. Looking more closely at the four cluster areas, the average distance from any building to the closest green space is 200 meters (taking approximately two minutes), which is considered excellent accessibility to green space.

Garden city. As previously mentioned, the neighborhoods of Altstetten and Albisrieden were designed as part of the 'Garden City' concept in Greater Zurich, and this concept is still evident in two aspects. Firstly, an overview of green space provision in the district reveals that the average green space area per resident is significantly higher compared to other districts in Zurich,

4 excluding private forests, agricultural fields, and urban farming areas. Secondly, the connectivity analysis of public green spaces considers the accumulated connections towards community gardens, private gardens, and individual buildings. The variation in connections suggests that the significance of each green space, as shown in

Figure 4, does not necessarily align with the size of specific green areas depicted in

Figure 11. This disconnect between space significance and size may explain why some public green spaces struggle to attract visitors. Some spaces may be unnecessarily large, such as Grünau, which is also situated near riverbanks, a sports center, and a motorway, while others may be too small to adequately serve nearby residents. A well-thought-out plan that takes into account the size and location of green spaces within the urban structure is essential to utilize their potential fully.

- 5.

Social inclusion coupled with natural preservation. Social equity and cultural diversity across observed green space clusters vary. For example, Bachwiesen has unequivocal boundaries between adjacent properties while remarkably accepting cultural diversity. Hearing more than ten foreign languages is usual, and this is significantly higher than in the other clusters. One of the reasons for such diversity may be that Freilager (a sizeable residential zone in Bachwiesen) brought many international residents to the area. The social diversity of Bachwiesen is also reflected in various activities across the site. Such a combination of green and grey spaces enables almost all outdoor activities, fulfils many visitor needs, and, ultimately, contributes to the balance between urban lifestyles and natural environments. In Grünau, as a highly international area, too, cultural diversity is evident, but the atmosphere differs from that of the Bachwiesen area – a variety of different ethnic groups is perceivable, however, their integration or using green space except for family gatherings is rare. In Lindenplatz, the square and park are vivid and full of diverse users, mainly on weekends. The Süsslerenanlage cluster faces the lowest cultural and social diversity, as individual housing and private gardens in traditional communities are considered a specific place value.

In a nutshell, the residents in the observed clusters enjoy their environment and appreciate spending time in nature. Furthermore, observed from the perspective of material green space attributes, the green areas in the vicinity of the new residential zones have recently undergone significant improvements to accommodate various needs and activities of different users. In other clusters, it is necessary to acknowledge the usual residential behaviors and visitors’ needs and improve the quality and connectivity among the green spaces. Finally, greater social diversity is expected in many community gardens, which can serve as a building block for creating a community’s identity and where people should be invited to develop a sense of belonging to specific neighborhoods.

6. Conclusions

The study probed the relationship between the policies on green space and their implementation, tested first on the case of Zurich’s district 9 and then the green space clusters within the mentioned district. The findings reveal a disconnect between policy objectives and the actual state of public green spaces in the observed cases. Instead, providing and designing public green space requires more careful consideration of location, size, and their role in the broader urban context, on the one hand, but also recognition of various local users’ needs on the other. Ultimately, such an approach can increase awareness about the natural environment among urban dwellers.

However, the study does encounter certain limitations. First, the analysis of activities in green spaces could be enhanced to provide a more accurate reflection of the actual situation by gathering additional on-site observation data over different time periods. The more detailed demographic information of the four clusters can better explain the effect of green spaces on different social groups. Finally, using qualitative methods elucidates better the people’s perceptions of green space, their feelings, and habits, thus adding more to understanding the immaterial green space attributes. Nevertheless, the comprehensive multi-scale overview offers a solid base and incentivizes further research on the ‘implementation gap’ in the planning and design of urban green space.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P. and J.Y.; methodology, A.P..; software, Y.J..; validation, A.P. and Y.J.; formal analysis, A.P. and Y.J.; investigation, A.P. and Y.J.; resources, A.P. and Y.J.; data curation, A.P. and Y.J.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P. and Y.J; writing—review and editing, A.P. and L.R.; visualization, J.Y.; supervision, S.M..; project administration, Y.J. and S.M..; funding acquisition, S.M.

Funding

This research was conducted at the Future Cities Lab Global at ETH Zurich. Future Cities Lab Global is supported and funded by the National Research Foundation, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore under its Campus for Research Excellence and Technological Enterprise (CREATE) programme and ETH Zurich (ETHZ), with additional contributions from the National University of Singapore (NUS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore and the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

| 1 |

Dr Boon Lay Ong conceived the GnPR to guide the provision of greenery in an urban setting, an indicator based on the building floor area ratio, demonstrating the intensity of building development. The GnPR estimates a three-dimensional quantification of the greenery of a site through the deployment of a leaf area index (LAI). |

| 2 |

The green spaces in Zurich were classified into eleven types based on three primary parameters: 1) the types of ground and flora, including forests, meadows, and swamps; 2) the functions served, such as agricultural fields, sports fields, and cemeteries; and 3) the locations, including street greenery and greenery surrounding residential facilities. |

| 3 |

In the SDG Indicator 11.7.1 Training Module: Public Space, public open space is categorized based on size and coverage area. The training module defines the service coverage radius for city public open spaces as 800 meters and neighborhood green spaces as 400 meters [36]. |

| 4 |

|

References

- Park, J.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, D.K.; Park, C.Y; Jeong, S.G. The influence of small green space type and structure at the street level on urban heat island mitigation. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2017, 21, 203–212. [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M.; Ban-Weiss, G.; Osmond, P.; Paolini, R.; Synnefa, A.; Cartalis, C.; Muscio, A.; Zinzi, M.; Morakinyo, T. E.; Ng, E.; Tan, Z.; Takebayashi, H.; Sailor, D.; Crank, P.; Taha, H.; Pisello, A.L.; Rossi, F.; Zhang, J.; Kolokotsa, D. Progress in Urban Greenery Mitigation Science - Assessment Methodologies, Advanced Technologies and Impact on Cities. Journal of Civil Engineering and Management 2018, 24(8), 638–671. [CrossRef]

- Maas, J. Vitamin G: Green environments—Healthy environments. Doctoral Dissertation, Universiteit Utrecht, Utrecht, 2009. https://www.nivel.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden/Proefschrift-Maas-Vitamine-G.pdf.

- Vienneau, D.; deHoogh, K.; Faeh, D.; Kaufmann, M.; Wunderli, J.M.; Röösli, M. More than clean air and tranquillity: Residential green is independently associated with decreasing mortality. Environment International 2017, 108, 176–184. [CrossRef]

- Belcher, R.N.; Chisholm, R.A. Tropical Vegetation and Residential Property Value: A Hedonic Pricing Analysis in Singapore. Ecological Economics 2018, 149, 149–159. [CrossRef]

- Dubová, L.; Macháč, J. Improving the quality of life in cities using community gardens: From benefits for members to benefits for all local residents. GeoScape 2019, 13(1), 68–78. [CrossRef]

- Panduro, T.E.; Veie, K.L. Classification and valuation of urban green spaces—A hedonic house price valuation. Landscape and Urban Planning 2013, 120, 119–128. [CrossRef]

- Oh, R.R.Y.; Richards, D.R.; Yee, A.T.K. Community-driven skyrise greenery in a dense tropical city provides biodiversity and ecosystem service benefits. Landscape and Urban Planning 2018, 169, 115–123. [CrossRef]

- Dadvand, P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. Green Space and Health. In Integrating Human Health unto Urban and Transport Planning: A Framework; Nieuwenhuijsen, M., Khreis, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 409–423.

- Gascon, M.; Sánchez-Benavides, G.; Dadvand, P.; Martínez, D.; Gramunt, N.; Gotsens, X.; Cirach, M.; Vert, C.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Crous-Bou, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. Long-term exposure to residential green and blue spaces and anxiety and depression in adults: A cross-sectional study. Environmental Research 2018, 162, 231–239. [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P. Green space as a buffer between stressful life events and health. Social Science & Medicine 2010, 70(8), 1203–1210. [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. UN Publishing: New York, US, 2015.

- United Nations (UN). New Urban Agenda. Habitat III Secretariat: Quito, Ecuador, 2017.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Urban greenspaces and health: A review of evidence. WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016.

- European Commission (EC). A European Green Deal. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Lennon, M.; Douglas, O.; Scott, M. Green Space Attributes for Enhancing Health and Well-being. In Review of World Planning Practice, Volume 18: Towards Healthy Cities: Urban Governance, Planning and Design for Human Well-being; Perić, A., Alraouf, A., Cilliers, J., Eds.; ISOCARP (International Society of City and Regional Planners): The Hague, Netherlands, 2022; pp. 177–188.

- Perić, A.; De Blust, S.; Jiang, Y.; Guariento, N.; Wälty, S. Urban Strategies for Dense and Green Zurich: From Healthy Neighbourhoods towards Healthy Communities? In In Search of a New Planning Agenda for Urban Health, Socio-Spatial Justice and Climate Resilience (Proceedings of the 58th ISOCARP World Planning Congress); Enlil, Z., Belpaire, E., Schuett, R., Morgado, S., Eds.; ISOCARP (International Society of City and Regional Planners): The Hague, Netherlands, 2022; pp. 1654–1667.

- EU Ministers. Urban Agenda 2.0 - Ljubljana Agreement (Adopted at the Informal Meeting of EU Ministers responsible for Urban Development, November 26, Slovenia), 2022.

- EU Ministers. Territorial Agenda 2030: A future for all places (Agreed at the Informal Meeting of EU Ministers responsible for Spatial Planning and Territorial Development and/or Territorial Cohesion. December 1, Germany), 2020.

- EU Ministers. The New Leipzig Charter. The transformative power of cities for the common good (Adopted at the Informal Ministerial Meeting on Urban Matters, November 30, Germany), 2020.

- European Commission (EC). Urban agenda for EU. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- European Commission (EC). Integrated sustainable urban development – Cohesion Policy 2014-2020. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2014.

- EU Ministers. Territorial Agenda 2020: Towards an Inclusive, Smart and Sustainable Europe of Diverse Regions (Agreed at the Informal Meeting of EU Ministers responsible for Spatial Planning and Territorial Development. May 19, Hungary), 2011.

- Federal Council. Sustainable Development Strategy 2030. Federal Council: Berne, Switzerland, 2021.

- Federal Council. Action Plan 2021-2023 for Sustainable Development Strategy 2030. Federal Council: Berne, Switzerland, 2021.

- Council for Spatial Planning (ROR). Megatrends and Spatial Development in Switzerland. ROR: Berne, Switzerland, 2019.

- Office for Spatial Development (ARE). Trends and Challenges: Figures and Background on the Swiss Spatial Strategy. ARE: Berne, Switzerland, 2018.

- Federal Council. Swiss Spatial Concept. Federal Council: Berne, Switzerland, 2012.

- Planning and Construction Law PBG, 2013. (OS 68, 189; ABl 2011, 1161).

- Spatial Planning Law RPG, 2019.

- Cantonal Council. Cantonal Structural Plan Zurich 2035. Cantonal Council: Zurich, Switzerland, 2019.

- Cantonal Council. Long-term Spatial Development Strategy of Canton Zurich. Cantonal Council: Zurich, Switzerland, 2014.

- City of Zurich. Regional Structural Plan. City of Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2017.

- City of Zurich. Communal Structural Plan. City of Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2021.

- City of Zurich. Strategies Zurich 2035. City of Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2016.

- United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-Habitat). SDG Indicator 11.7.1 Training Module: Public Space. UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/07/indicator_11.7.1_training_module_public_space.pdf.

- Kurz, D. Die Disziplinierung der Stadt: Moderner Städtebau in Zürich 1900 bis 1940 (Studienausgabe). gta Verlag: Zurich, Switzerland, 2021.

- Stadt Zürich Statistik. (2022). Quartierspeigel Alstetten 2022. Zürich: Stadt Zürich Präsidialdepartement, Statistik Stadt Zürich. https://www.stadt-zuerich.ch/prd/de/index/statistik/publikationen-angebote/publikationen/Quartierspiegel/QUARTIER_092.html.

Figure 1.

Zurich’s district 9 (in red) composed by Altstetten and Albisrieden neighborhoods. Source: Authors.

Figure 1.

Zurich’s district 9 (in red) composed by Altstetten and Albisrieden neighborhoods. Source: Authors.

Figure 2.

Density of green areas in Altstetten and Albisrieden: green surface plot ratio (GsPR). Source: Authors.

Figure 2.

Density of green areas in Altstetten and Albisrieden: green surface plot ratio (GsPR). Source: Authors.

Figure 3.

Intensity of greenery in Altstetten and Albisrieden: Leaf Area Index (LAI). Source: Authors

Figure 3.

Intensity of greenery in Altstetten and Albisrieden: Leaf Area Index (LAI). Source: Authors

Figure 4.

Connectivity between identified public green spaces in Altstetten and Albisrieden: Source: Authors

Figure 4.

Connectivity between identified public green spaces in Altstetten and Albisrieden: Source: Authors

Figure 5.

Four clusters (subsites) in Altstetten and Albisrieden: Source: Authors

Figure 5.

Four clusters (subsites) in Altstetten and Albisrieden: Source: Authors

Figure 6.

The structure of green spaces in four clusters in Altstetten and Albisrieden: (a) Grünau; (b) Lindenplatz; (c) Bachwiesen; (d) Süsslerenanlage. Source: Authors.

Figure 6.

The structure of green spaces in four clusters in Altstetten and Albisrieden: (a) Grünau; (b) Lindenplatz; (c) Bachwiesen; (d) Süsslerenanlage. Source: Authors.

Figure 7.

Grünau: (a) Short and scattered playground activities; (b) A family-gathering with a group of children resting. Source: Authors.

Figure 7.

Grünau: (a) Short and scattered playground activities; (b) A family-gathering with a group of children resting. Source: Authors.

Figure 8.

Lindenplatz: (a) Activities in a weekday afternoon; (b) Free market on Saturdays. Source: Authors.

Figure 8.

Lindenplatz: (a) Activities in a weekday afternoon; (b) Free market on Saturdays. Source: Authors.

Figure 9.

Bachwiesen: (a) Goats from the Community Zoo walking around Bachwiesenpark; (b) Typical weekday afternoon’s activities. Source: Authors.

Figure 9.

Bachwiesen: (a) Goats from the Community Zoo walking around Bachwiesenpark; (b) Typical weekday afternoon’s activities. Source: Authors.

Figure 10.

Süsslerenanlage: (a) Exercising workshop; (b) Swinging. Source: Authors.

Figure 10.

Süsslerenanlage: (a) Exercising workshop; (b) Swinging. Source: Authors.

Figure 11.

Distribution of public green spaces in Altstetten and Albisrieden (the size of the circle represents the area). Source: Authors.

Figure 11.

Distribution of public green spaces in Altstetten and Albisrieden (the size of the circle represents the area). Source: Authors.

Table 1.

The

‘green urban agenda’ principles of major global and European territorial/urban development policy documents. Source: Authors based on [

17].

Table 1.

The

‘green urban agenda’ principles of major global and European territorial/urban development policy documents. Source: Authors based on [

17].

| Documents |

Cross-Cutting Principles |

New Urban Agenda

[13] |

balanced, sustainable and integrated urban and territorial development, planning and design resilience and responsiveness to natural and human-made hazards mitigation of and adaptation to climate change compact, connected and inclusive cities environmental sustainability green infrastructure preservation and enhancement of natural heritage |

2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

[12] |

resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards capacity of local communities to pursue sustainable livelihood opportunities the importance of green spaces |

Ljubljana Agreement

[18] |

greening cities mitigation of and adaptation to climate change climate neutrality by 2050 integrated and sustainable development |

Territorial Agenda 2030

[19] |

better ecological livelihoods (nature-based solutions, green-blue infrastructure) climate-neutral and resilient towns, cities and regions rehabilitation and reutilization of the built environment |

The New Leipzig Charter

[20] |

integrated urban development compact cities, urban regeneration, brownfield development management and conversion of existing built environment green city (high quality of green and recreational spaces, climate-resilient and carbon-neutral buildings, net-zero carbon city) |

Urban Agenda for the EU

[21] |

|

|

Integrated sustainable urban development – Cohesion policy 2014–2020 [22] |

|

Territorial Agenda of the European Union 2020

[23] |

|

Table 2.

Leaf Area Index (LAI) values for different plant types. Source: Authors.

Table 2.

Leaf Area Index (LAI) values for different plant types. Source: Authors.

| Plant Types |

LAI Value |

| tree |

open canopy: 2.5

intermediate canopy: 3

dense Canopy: 4

intermediate columnar canopy: 3 |

| shrubs |

monocot: 3.5

dicot: 4.5 |

| turf |

turf: 2 |

Table 3.

Variables associated with dominant activities in selected green space clusters. Source: Authors.

Table 3.

Variables associated with dominant activities in selected green space clusters. Source: Authors.

| Variable |

|---|

| location |

approximate areas where activities occurred in QGIS |

| area size (m2) |

green space

grey surface |

| average distance to buildings (m) |

|

| duration (min.) |

mean

min.

max. |

| gender |

female

male

unknown: toddlers and some special cases |

| age |

< 10: young children and toddlers

10-20: adolescents

20-30: young adults

30-60: adults

> 60: senior people |

| user types |

solo visitors

group visitors |

| language |

local languages: Swiss German and Swiss French

European languages: German, French, Italian, English, etc.

Asian languages: Indian, Chinese, etc.

other languages: languages that cannot be identified |

Table 4.

The ‘green urban agenda’ principles of major federal, cantonal, and local (city of Zurich) urban development policy documents. Source: Authors.

Table 4.

The ‘green urban agenda’ principles of major federal, cantonal, and local (city of Zurich) urban development policy documents. Source: Authors.

| Documents |

Cross-Cutting Principles |

Sustainable Development Strategy 2030

[24] |

sustainable and resilient planning and design of the built environment

coping with climate change effects |

|

Action Plan 2021-2023 for Sustainable Development Strategy 2030 [25] |

|

Megatrends and Spatial Development in Switzerland

[26] |

new urban/regional centers

infill development

densification

city greening

higher urbanity: combining higher density and green/open areas |

Trends and Challenges: Figures and Background on the Swiss Spatial Strategy

[27] |

sustainable development

climate adaptation and mitigation

infill development / densification within the already built environment

compact and diverse settlements to allow more open space and optimal use of public infrastructure

space-saving urban design |

Swiss Spatial Concept

[28] |

infill development

brownfield redevelopment

protection of natural areas

upgrade of settlements and landscapes |

|

Planning and Construction Law PBG [29] |

|

Spatial Planning Law RPG

[30] |

infill development (Art. 1)

compact settlements (Art. 1) |

Cantonal Structural Plan Zurich 2035

[31] |

sustainable planning

dense and compact settlements |

Long-term Spatial Development Strategy of Canton Zurich

[32] |

infill development

place-specific densification

nurture of open and recreational spaces |

Regional Structural Plan

[33] |

district-specific development and diverse densification

preservation of landscape and recreational areas

energy-saving and climate-neutral urban renewal |

Communal Structural Plan

[34] |

diverse and ‘smart’ (preserving identity) densification

high-quality open public spaces

preservation of city nature

‘kurze Wege’

environmentally friendly development

garden city

ecological corridors |

Strategies Zurich 2035

[35] |

sustainable growth

social inclusion coupled with natural preservation

high-quality densification

high-quality recreational spaces |

Table 5.

Green spaces (types, subtypes, and size) in Altstetten and Albisrieden. Source: Authors.

Table 5.

Green spaces (types, subtypes, and size) in Altstetten and Albisrieden. Source: Authors.

| Green Space Type Green Space Subtype |

Size |

| public green spaces |

parks and public gardens

other open green spaces |

36,820 m2

108,670 m2

|

| community green spaces |

community gardens |

1,085,065 m2 |

| private green spaces |

private gardens

urban farming

other private green spaces |

650,877 m2

405,720 m2

355,240 m2

|

| other reserved green spaces |

closed forest

reserved pasture fields

intensive agriculture fields

sports fields

traffic greenery

cemeteries

stocked fields

other greenery |

3,489,788 m2

709,485 m2

53,340 m2

235,069 m2

70,912 m2

124,914 m2

80,170 m2

13,433 m2

|

Table 6.

Sample statistics for each cluster. Source: Authors.

Table 6.

Sample statistics for each cluster. Source: Authors.

| |

Total |

Grünau |

Linden-

Platz |

Bach-

Wiesen |

Süssleren-

Anlage |

area size (m2)

green spaces

grey surface |

318,605

193,388

125,217 |

119,091

79,166

39,925 |

67,300

39,384

27,916 |

92,250

45,527

46,723 |

39,964

29,311

10,653 |

| average distance to buildings |

|

188.8 m |

190.0 m |

213.5 m |

194.0 m |

duration (min)

mean

min.

max. |

80

2

270 |

111

10

270 |

58

5

255 |

96

5

270 |

57

2

210 |

gender

female

male

unknown |

47%

51%

2% |

47%

52%

1% |

43%

57%

|

52%

45%

3% |

42%

58% |

age

< 10

10 to 20

20 to 30

30 to 60

> 60 |

30%

4%

12%

42%

11% |

33%

7%

6%

35%

19% |

8%

8%

11%

61%

12% |

44%

1%

10%

34%

11% |

40%

3%

26%

27%

3% |

user types

group

solo |

90%

10% |

94%

6% |

79%

21% |

97%

3% |

96%

4% |

language

local languages

European languages

Asian languages

other languages

(blank)*

|

726

135

25

211

16 |

57

44

22

1 |

279

45

18

35 |

273

43

7

153

15 |

117

3

1

|

Table 7.

Activities identified in each cluster. Source: Authors.

Table 7.

Activities identified in each cluster. Source: Authors.

| |

Total |

Grünau |

Linden-

Platz |

Bach-

Wiesen |

Süssleren-

Anlage |

activity type

resting

chatting

gathering (events incl.)

playing

walking

walking dogs

exercising

cycling |

444

110

67

420

28

13

6

25 |

21

20

23

58

2 |

325

6

17

27

2

|

94

53

36

273

1

8

3

23 |

4

31

8

72

3

3

|

| total observed activities |

1,113 |

124 |

337 |

491 |

121 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).