Submitted:

05 June 2023

Posted:

05 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Anatomical data

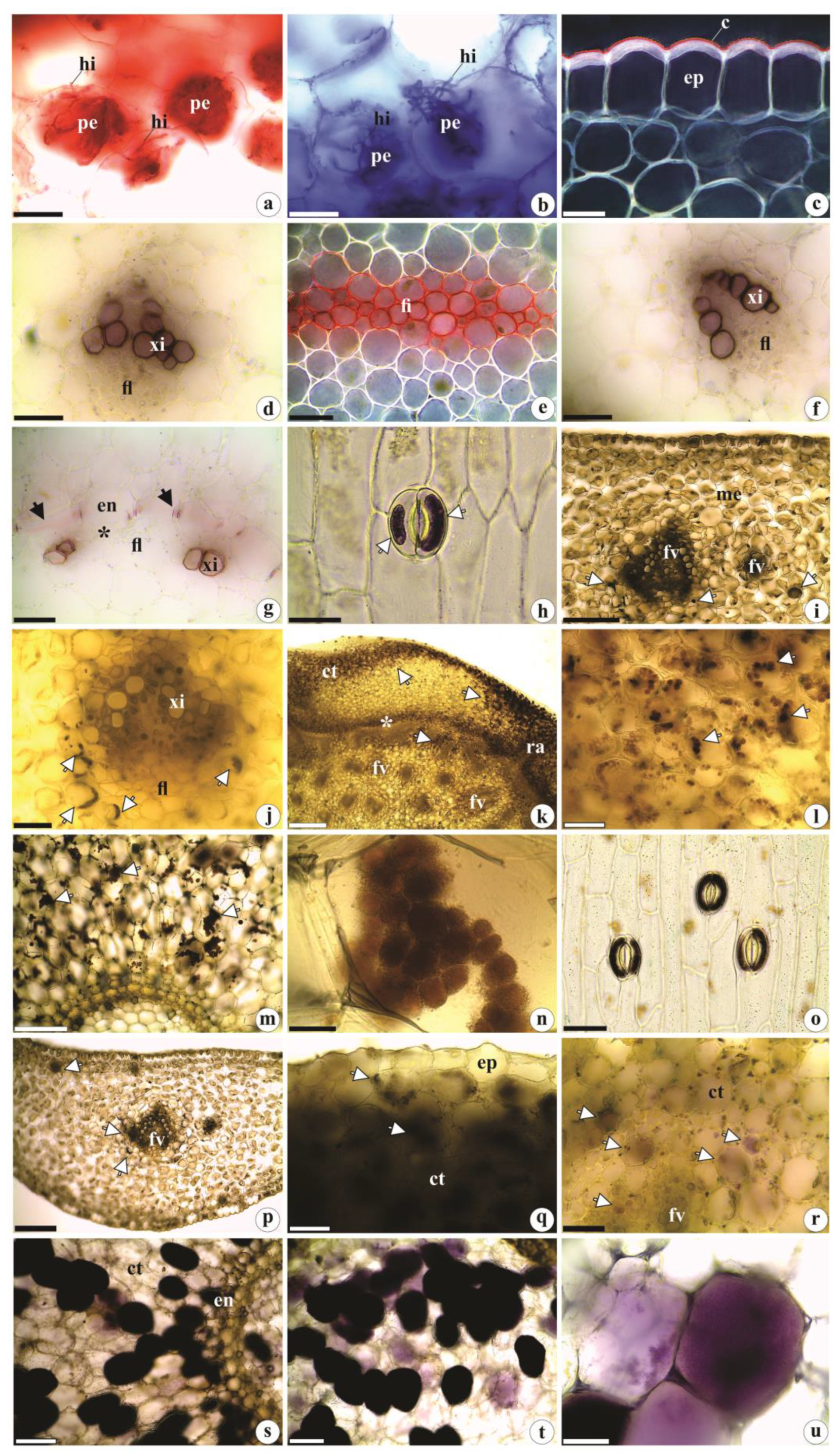

2.1.1. Leaf anatomy

2.1.2. Rhizome anatomy

2.1.3. Root anatomy

2.2. Histochemistry data

3. Materials and Methods

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rutkowski, P.; Mytnik, J.; Szlachetko, D.L. New taxa and new combinations in Mesoamerican Spiranthinae (Orchidaceae, Spirantheae). Ann. Bot. Fenn. 2004, 41, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, F.; Vinhos, F.; Rodrigues, V.T.; Barberena, F.F.V.A.; Fraga, C.N.; Pessoa, E.M.; Forster, W.; Menini-Neto, L.; Furtado, S.G.; Nardy, C.; Azevedo, C.O.; Guimarães, L.R.S.; Orchidaceae. In Lista de Espécies da Flora do Brasil. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. 2015. Available online: http://servicos.jbrj.gov.br/flora/search/Brachystele_guayanensis (accessed on 18-X-2021).

- Rasmussen, H. The diversity of stomatal development in Orchidaceae subfamily Orchidoideae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1981, 82, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porembski, S.; Barthlott, W. Velamen radicum micromorphology and classification of Orchidaceae. Nord. J. Bot. 1988, 8, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, W.L.; Aldrich, H.C.; McDowell, L.M.; Morris, M.W.; Pridgeon, A.M. Amyloplasts from cortical root cells of Spiranthoideae (Orchidaceae). Protoplasma 1993a, 172, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, W.L.; Morris, M.W.; Judd, W.S.; Pridgeon, A.M.; Dressler, R.L. Comparative vegetative anatomy and systematics of Spiranthoideae (Orchidaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1993b, 113, 161–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pridgeon, A.M. Systematic leaf anatomy of Caladeniinae (Orchidaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1994, 114, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzweil, H.; Linder, H.P.; Stern, W.L.; Pridgeon, A.M. Comparative vegetative anatomy and classification of Diseae (Orchidaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1995, 117, 171–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, W.L. Vegetative anatomy of subtribe Orchidinae (Orchidaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1997a, 124, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, W.L. Vegetative anatomy of subtribe Habenariinae (Orchidaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1997b, 125: 211–227. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, C.; Salazar, G.A.; Zavaleta, H.A.; Engleman, E.M. Root character evolution and systematics in Cranichidinae, Prescottiinae and Spiranthinae (Orchidaceae, Cranichideae). Ann. Bot. 2008, 101, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.S.F.P.; Isaias, R.M.S. Comparative anatomy of the absorption roots of terrestrial and epiphytic orchids. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2008, 51, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aybeke, M.; Sezik, E.; Olgun, G. Vegetative anatomy of some Ophrys, Orchis and Dactylorhiza (Orchidaceae) taxa in Trakya region of Turkey. Flora 2010, 205, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aybeke, M. Comparative anatomy of selected rhizomatous and tuberous taxa of subfamilies Orchidoideae and Epidendroideae (Orchidaceae) as an aid to identification. Plant Syst. Evol. 2012, 298, 1643–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corredor, B.A.D.; Arias, R.L. Morfoanatomía en Cranichideae (Orchidaceae) de la Estación Loma Redonda del Parque Nacional “Sierra Nevada”, Mérida, Venezuela. Lankesteriana 2012, 12, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, W.L. Anatomy of the Monocotyledons: X. Orchidaceae., 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, 2014; pp. 1–288. [Google Scholar]

- Andreota, R.C.; Barros, F.; Sajo, M.G. Root and leaf anatomy of some terrestrial representatives of the Cranichideae tribe (Orchidaceae). Rev. Bras. Bot. 2015, 38, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, A.A.; Smidt, E.C.; Bona, C. Spiral root hairs in Spiranthinae (Cranichideae: Orchidaceae). Rev. Bras. Bot. 2015, 38, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenel, G.; Akbulut, M.K.; Şeker, Ş.S. Comparative anatomical properties of some Epidendroideae and Orchidoideae species distributed in NE Turkey. Protoplasma 2019, 256, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bona, C.; Engels, M.E.; Pieczak, F.S.; Smidt, E.C. Comparative vegetative anatomy of Neotropical Goodyerinae Klotzsch (Orchidaceae Juss.: Orchidoideae Lindl.). Acta Bot. Bras. 2020, 34, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, C. Orchideen als Arzneipflanzen: Ein Querschnitt durch ausgewählte medizinische und botanisch-pharmazeutische Literatur des 19. Jahrhunderts. Z. fur Phytother. 2009, 30, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verettoni, H.N. Contribución al conocimiesão bioativas de las plantas medicinales de la región de Bahía Blanca., 1st ed.; Harris y Cia: Bahía Blanca, Argentina, 1985; pp. 1–374. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, V.C.; Sajo, M.G. Leaf anatomy of epiphyte species of Orchidaceae. Rev. Bras. Bot. 1999, 22, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.I.; Milaneze-Gutierre, M.A. Caracterização morfoanatômica dos órgãos vegetativos de Cattleya walkeriana Gardner (Orchidaceae). Acta Sci. 2004, 26, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahn, A. Plant anatomy., 4th ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, England, 1990; pp. 1–530. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W.K.; Vogelmann, T.C.; DeLucia, E.H.; Bell, D.T.; Shepherd, K.A. Leaf form and photosynthesis. Bioscience 1997, 47, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, W.L.; Judd, W.S. Comparative vegetative anatomy and systematics of Vanilla (Orchidaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1999, 131, 353–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, W.L.; Judd, W.S. Comparative anatomy and systematics of the orchid tribe Vanilleae excluding Vanilla. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2000, 134, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsward, B.S.; Stern, W.L. Vegetative anatomy and systematics of Triphorinae (Orchidaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2009, 159, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, N.L.; Elbl, P.M.; Cury, G.; Appezzato-da-Glória, B.; Sasaki, K.L.; Silva, C.G.; Costa, G.R.; Lima, V.G. The meristematic activity of the endodermis and the pericycle and its role in the primary thickening of stems in monocotyledonous plants. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2012, 5, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, O.L.; Kasuya, M.C.M.; Rollemberg, C.L.; Chaer, G.M. Isolamento e identificação de fungos micorrízicos rizoctonióides associados a três espécies de orquídeas epífitas neotropicais no Brasil. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2005, 29, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougoure, J.; Ludwig, M.; Brundrett, M.; Grierson, P. Identity and specificity of the fungi forming mycorrhizas with the rare mycoheterotrophic orchid Rhizanthella gardneri. Mycol. Res. 2009, 113, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suetsugu, K.; Haraguchi, T.F.; Tanabe, A.S.; Tayasu, I. Specialized mycorrhizal association between a partially mycoheterotrophic orchid Oreorchis indica and a Tomentella taxon. Mycorrhiza 2021, 31, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, C.R. Comparative anatomy as a modern Botanical discipline. In Advances in botanical research, 1st ed.; Metcalfe, C.R., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, United States, 1963; Volume VI, pp. 101–147. [Google Scholar]

- Appezzato-da-Glória, B.; Carmello-Guerreiro, S.M. Anatomia Vegetal., 2rd ed.; Editora UFV: Viçosa, Bahia, Brazil, 2006; pp. 1–438. [Google Scholar]

- Andreota, R.C. Anatomia dos órgãos vegetativos de representantes da tribo Cranichideae (Orchidoideae: Orchidaceae). Masters’ thesis, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Rio Claro, São Paulo, Brazil, 2013.

- Pridgeon, A.M. The velamen and exodermis of orchid roots. In Orchid biology, reviews and perspectives, 1st ed.; Arditti, J., Ed.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, New York, United States, 1987; Volume IV, pp. 139–192. [Google Scholar]

- Chomicki, G.; Bidel, L.P.R.; Ming, F.; Coiro, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Baissac, Y.; Jay-Allemand, C.; Renner, S.S. The velamen protects photosynthetic orchid roots against UV-B damage, and a large dated phylogeny implies multiple gains and losses of this function during the Cenozoic. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 1330–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, D.D.; Johnson, I.; Leake, J.R.; Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal acquisition of inorganic phosphorus by the green-leaved terrestrial orchid Goodyera repens. Ann. Bot. 2007, 99, 831–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, G.A.; Chase, M.W.; Arenas, M.S.; Ingrouille, M. Phylogenetics of Cranichideae with emphasis on Spiranthinae (Orchidaceae, Orchidoideae): evidence from plastid and nuclear DNA sequences. Am. J. Bot. 2003, 90, 777–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şeker, Ş.S. What does the quantitative morphological diversity of starch grains in terrestrial orchids indicate? Microsc. Res. Tech. 2022, 85, 2931–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzing, D.H.; Friedman, W.E.; Peterson, G.; Renfrow, A. Shootlessness, velamentous roots, and the pre-eminence of Orchidaceae in the epiphytic biotype. Am. J. Bot. 1983, 70, 121–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanford, W.W.; Adanlawo, I. Velamen and exodermis characters of west african epiphytic orchids in relation to taxonomic grouping and habitat tolerance. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1973, 66, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juniper, B.E.; Jeffree, C.E. Plant surfaces., 1st ed.; Edward Arnold Publishers: London, England, 1983; pp. 1–93. [Google Scholar]

- Dickison, W.C. Integrative plant anatomy., 1st ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, United States, 2000; pp. 1–533. [Google Scholar]

- Evert, R.F. Esau’s plant anatomy: meristems, cells and tissues of the plant body: their structure, function and development., 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New Jersey, United States, 2006; pp. 1–601. [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi, V.R.; Nakata, P.A. Calcium oxalate in plants: formation and function. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2005, 56, 41–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haridasan, M. Alumínio é um elemento tóxico para as plantas nativas do cerrado. In Fisiologia Vegetal: práticas em relações hídricas, fotossíntese e nutrição mineral, 1st ed.; Prado, C.H.B.A., Casali, C.A., Eds.; Editora Manole: Barueri, São Paulo, Brazil, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, C.A.; Murrmann, M.; Steudle, E. Location of the major barriers to water and ion movement in young roots of Zea mays L. Planta 1993, 190, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enstone, D.E.; Peterson, C.A.; Ma, F. Root endodermis and exodermis: structure, function, and responses to the environment. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2003, 21, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, A.; Luxová, M. Growth and differentiation of root endodermis in Primula acaulis Jacq. Biol. Plant. 2003, 47, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holttum, R. Growth habitats of monocotyledons - variations on a theme. Phytomorphology 1955, 5, 399–413. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, E.; Ziegler, P. Biosynthesis and degradation of starch in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1989, 40, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.; Akisue, G. Fundamentos de farmacobotânica., 1st ed.; Atheneu: São Paulo, Brazil, 1989; pp. 1–216. [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury, F.B.; Ross, C.W. Plant physiology., 4th ed.; Wadsworth: Belmont, United States, 1992; pp. 1–267. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, E.; Scopel, M.; Vignoli-Silva, M.; Vendruscolo, G.S.; Henriques, A.T.; Mentz, L.A. Caracterização farmacobotânica das espécies de Sambucus (Caprifoliaceae) utilizadas como medicinais no Brasil. Parte II. Sambucus australis Cham. & Schltdl. Braz. J. Pharmacog. 2007, 17, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, T.Y.S.; Braga, Z.V.; Potiguara, R.C.V. Anatomia foliar de Socratea exorrhiza (Mart.) H. Wendl. (Arecaceae). Biota Amazôn. 2016, 6, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, R.E.; Alvim, M.N. Anatomia foliar comparada de três espécies do gênero Oxalis L. (Oxalidaceae). NBC 2013, 3, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavasseur, A.; Raghavendra, A.S. Guard cell metabolism and CO2 sensing. New Phytol. 2005, 165, 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, W.L.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Osorio, S.; Usadel, B.; Fuentes, D.; Nagy, R.; Balbo, I.; Lehmann, M.; Studart-Witkowski, C.; Tohge, T.; Martinoia, E.; Jordana, X.; DaMatta, F.M.; Fernie, A.R. Antisense inhibition of the iron-sulphur subunit of succinate dehydrogenase enhances photosynthesis and growth in tomato via an organic acid mediated effect on stomatal aperture. Plant Cell. 2011, 23, 600–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulpitt, C.J.; Li, Y.; Bulpitt, P.F.; Wang, J. The use of orchids in Chinese medicine. J. R. Soc. Med. 2007, 100, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sut, S.; Maggi, F.; Dall'Acqua, S. Bioactive secondary metabolites from orchids (Orchidaceae). Chem. Biodivers. 2017, 14, e1700172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, T. Chemical ecology of pyrrolizidine alkaloids. Planta 1999, 207, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda-Jiménez, G.; Porta-Ducoing, H.; Rocha-Sosa, M. La participación de los metabolitos secundarios en la defensa de las plantas. Rev. Mex. Fitopatol. 2003, 21, 355–363. [Google Scholar]

- Vizzotto, M.; Krolow, A.C.R.; Weber, G.E.B. Metabólitos secundários encontrados em plantas e sua importância., 1st ed.; Embrapa Clima Temperado: Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 2010; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.W.; Zhang, Z.B.; Zhang, S.B. Widely targeted metabolic, physical and anatomical analyses reveal diverse defensive strategies for pseudobulbs and succulent roots of orchids with industrial value. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2022, 177, 114510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, R.M.P. Orchids: A review of uses in traditional medicine, its phytochemistry and pharmacology. J. Med. Plant Res. 2010, 4, 592–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M. Therapeutic orchids: Traditional uses and recent advances—An overview. Fitoterapia 2011, 82, 102–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito, H.O.; Noronha, E.P.; França, L.M. Phytochemical analysis composition from Annona squamosa (ATA) ethanolic extract leaves. Rev. Bras. Farm. 2008, 89, 180–184. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, T.B.; Liu, J.; Wong, J.H.; Ye, X.; Sze, S.C.W.; Tong, Y.; Zhang, K.Y. Review of research on Dendrobium, a prized folk medicine. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 93, 1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liu, T.; Liu, M.; Chen, F.; Liu, S.; Yang, J. Anti-influenza a virus activity of dendrobine and its mechanism of action. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 3665–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, S.A.; Silva, L.A.; Lisboa, G.; Coradin, L. Manual de Manejo do Herbário Fanerogâmico. 2nd. ed.; CEPLAC: Ilhéus, Bahia, Brazil, 1989; pp. 1–104. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, D.A. Plant microtechnique., 1st ed.; McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc.: New York, United States, 1940; pp. 1–523. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, J.E.; Arduin, M. Manual básico de métodos em morfologia vegetal., 1st ed.; EDUR: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1997; pp. 1–198. [Google Scholar]

- Bukatsch, F. Bermerkungen zur Doppelfrbung Astrablau-Safranin. Mikrokosmos 1972, 61, 255. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, D.B. Protein staining of ribboned epon sections for light microscopy. Histochemie 1968, 16, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, T.P.; McCully, M.E. The study of plant structure principles and selected methods., 1st ed.; Termarcarphi: Melbourne, Australia, 1981; pp. 1–344. [Google Scholar]

- Furr, M.; Mahlberg, P.G. Histochemical analyses of laticifers and glandular trichomes in Cannabis sativa. J. Nat. Prod. 1981, 44, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, W.A. Botanical histochemistry: principles and practice., 1st ed.; W.H. Freeman: San Francisco, United States, 1962; pp. 1–408. [Google Scholar]

- Mace, M.E.; Howell, C.R. Histological and identification of condensed tannin precursor in roots of cotton seedlings. Canad. J. Bot. 1974, 52, 2423–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, C.J. Methods in plant histology., 5th ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, United States, 1932; pp. 1–416. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).