Submitted:

02 June 2023

Posted:

05 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

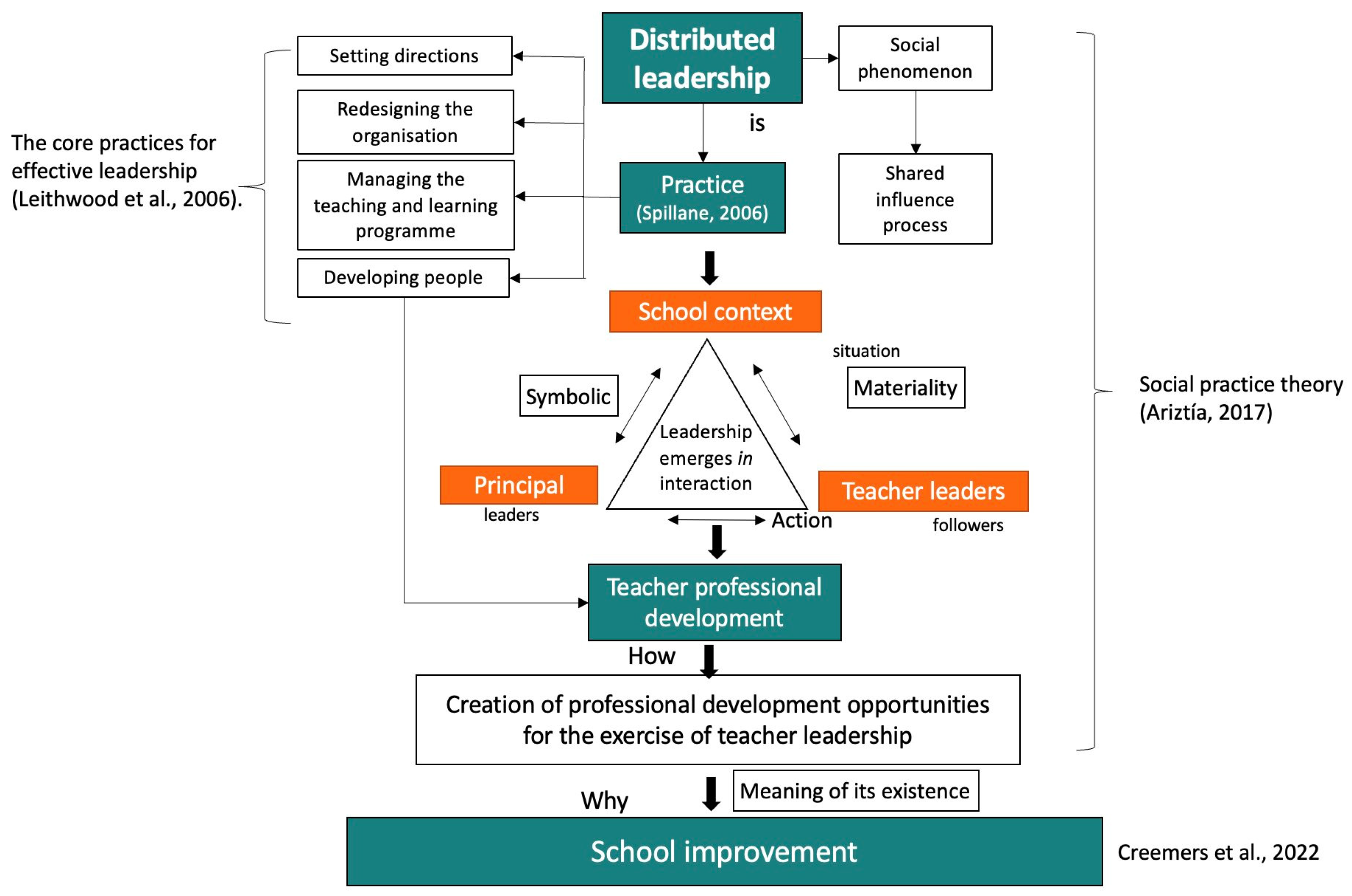

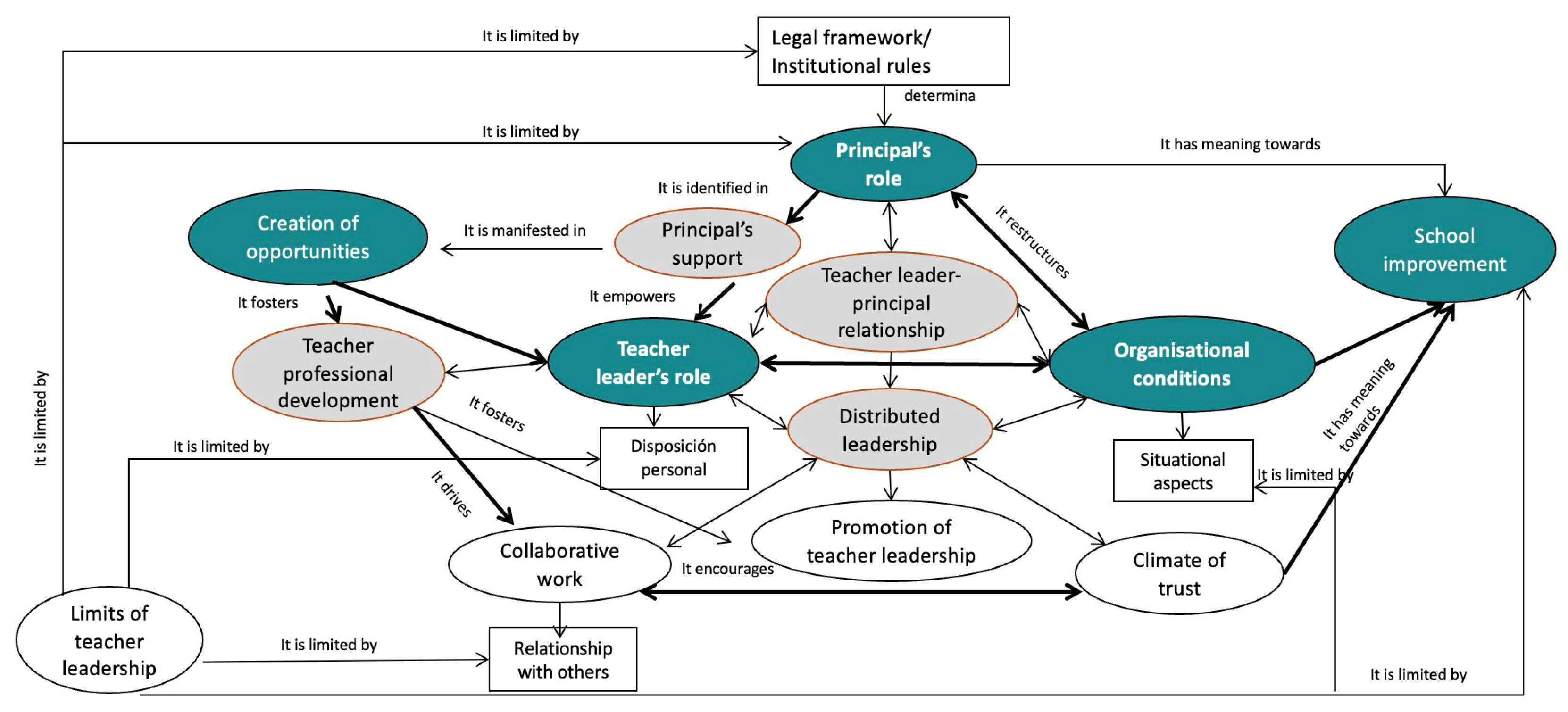

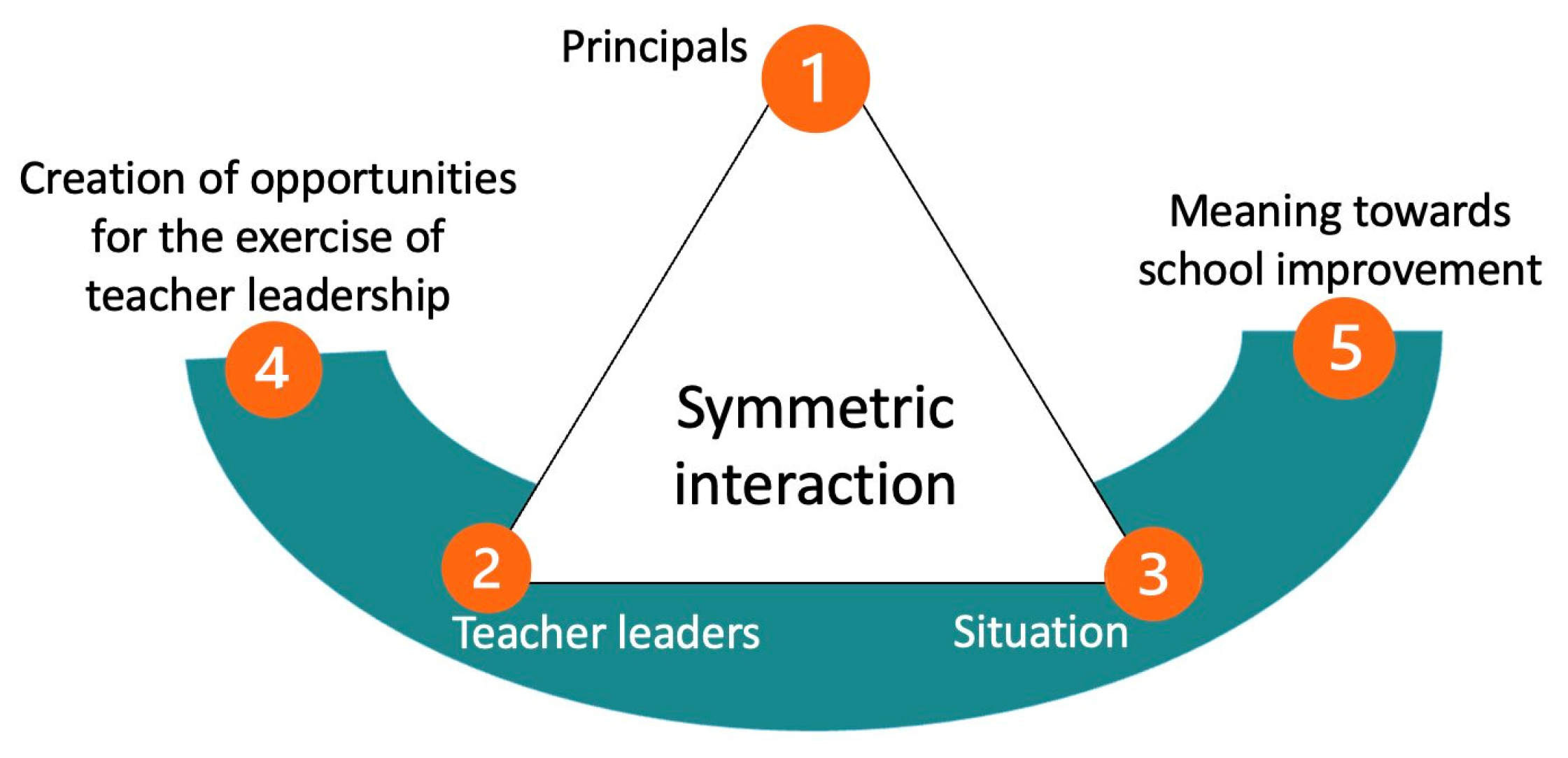

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.2. Purpose of the Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Ethical Approval

2.4. Field Work and Data Analysis

2.5. Evaluating the Realiability and Validity of the Study

- The transcriptions were faithful to the recordings of the interviews, trying at all costs to avoid being limited, selective, partial, biased, and incomplete to ensure the saturation of emerging themes;

- Updated documents were used as data sources so that the information they presented was consistent with the current context in which the research was conducted;

- The NVivo 12 program was used to mitigate and avoid possible human errors that could create confusion in the process of coding, categorizing, and providing ambiguous information;

- Transcripts are available so they can be corroborated by contacting the author;

- In the coding and categorization processes, loss of the richness of words and their connotations was avoided as much as possible;

- We avoided imposing meaning on the categories according to the point of view of the researcher and what the analysis texts declared, and the people interviewed wanted to say were maintained at all costs.

3. Results

3.1. Management of Principals about School Organisation

3.2. Development of the Professional Capacities of Teacher Leaders

3.3. Management of Principals about School Coexistence and Participation of Teacher Leaders

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harris, A.; DeFlaminis, J. Distributed leadership in practice: evidence, misconceptions and possibilities. Manag. in Ed. 2016, 30, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A.; Connor, M. Collaborative professionalism: When teaching together means learning for all, 1st ed.; Corwin Press: California, United States, 2018; pp. 1–141. [Google Scholar]

- Spillane, J. Distributed Leadership. The Ed. Forum 2005, 69, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J. Distributed leadership, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, United States, 2006; pp. 1–144. [Google Scholar]

- Ariztía, T. La teoría de las prácticas sociales: particularidades, posibilidades y límites. Rev. de Epistemología de Cs. Soc. 2017, 59, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdames, M.; Antúnez, A.; Silva, P. Liderazgo distribuido como práctica de los directivos escolares para la mejora escolar en Chile. In Políticas Públicas para la Equidad Social, 1st ed.; Rivera-Vargas, P., Muñoz-Saavedra, J., Morales-Olivares, R. y Butendieck, S., Eds.; Colección Políticas Públicas: Santiago, Chile, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 111–122, http://hdl.handle.net/2445/136061. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A.; Jones, M. Teachers leading enquiry. Sch. Lead. & Manag. 2022, 42, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J. H; Horn, P.; Supovitz, J.; Margolis, J. Typology of Teacher Leadership Programs. CPRE Research Reports 2019, 1, 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.; Ng, D. Teacher collaboration for change: sharing, improving, and spreading. Prof. Develop. in Ed. 2020, 46, 638–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krichesky, G.; Murillo, F. J. La colaboración docente como factor de aprendizaje y promotor de mejora. Un estudio de casos. Educ. XX1 2018, 21, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law Nº 20.006 of 2005 Competitiveness of Principal and Heads of the Administrative Department of public education. Available online: http://bcn.cl/1z01q (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Law Nº 20.501 of 2011 Education Quality and Equity. Available online: http://bcn.cl/1vz9t (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Law Nº 20.529 of 2011 Quality Assurance System. Available online: http://bcn.cl/1uv5c (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Law Nº 20.845 of 2015 School Inclusion. Available online: http://bcn.cl/1uv1u (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Law Nº 20.903 of 2016 Teacher Professional Development System. Available online: http://bcn.cl/1uzzn (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Law Nº 21.040 of 2017 New Public Education System. Available online: https://bcn.cl/2f72w (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Law Nº 20.370 of 2009 General Education Law. Available online: http://bcn.cl/1uvx5 (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- MINEDUC Avances del Sistema de Educación Pública y extensión del calendario de implementación. Available online: https://n9.cl/awsey (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Leithwood, K.; Day, C.; Sammons, P.; Harris, A.; Hopkins, D. Successful School Leadership What it is and How it influences pupil learning. Nat. College for Sch. Lead. 2006, 1, 1–132, https://n9.cl/9k6k. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.; Harris, A.; Hopkins, D. Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. Sch. Lead. & Manag 2020, 40, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pont, B. A literature review of school leadership policy reforms. Europ. Jour. of Edu. 2020, 55, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullan, M. Liderar en una cultura de cambio, 3rd ed.; Ediciones Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2022; pp. 1–176. [Google Scholar]

- DeFlaminis, J.; Abdul-Jabbar, M.; Yoak, E. Distributed leadership in schools. A practical guide for learning and improvement, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, United States, 2016; pp. 1–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Jones, M.; Ismail, N. Distributed leadership: taking a retrospective and contemporary view of the evidence base. Sch. Lead. & Manag. 2022, 42, 438–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supovitz, J. A.; D'Auria, J.; Spillane, J. P. Meaningful & sustainable school improvement with distributed leadership. CPRE Research Reports 2019, 1, 1–66, https://repository.upenn.edu/cpre_researchreports/112. [Google Scholar]

- Tintoré, M. & Gairín, J. Tres décadas de investigación sobre liderazgo educativo en España. Un mapeo sistemático. REICE 2022, 20, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tintoré, M.; Gairín, J. Liderazgo educativo en España, revisión sistemática de la literatura. In Liderazgo educativo en Iberoamérica. Un mapeo de la investigación hispanohablante, 1st ed.; Díaz Delgado, M.A. (coord.). Editorial Infinita: Ciudad de México, México, 2023; pp. 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Creemers, B. P.; Peters, T.; Reynolds, D. (Eds.) School effectiveness and school improvement, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, United Kingdom, 2022; pp. 1–430. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, G.A.; Askell-Williams, H.; Barr, S. Sustaining school improvement initiatives: advice from educational leaders. Sch. Effect. and Sch. Improv. 2023, 34, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M. Practice Theory and Routine Dynamics. In Cambridge Handbook of Routine Dynamics, 1st ed.; Feldman, M., Pentland, B., D’Adderio, L., Dittrich, K., Rerup, C., Seidl, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2021; pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azorín, C.; Harris, A.; Jones, M. Taking a distributed perspective on leading professional learning networks. Sch. Lead. & Manag. 2019, 40, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdames-Calderón, M. Prácticas directivas de liderazgo distribuido: creación de oportunidades de desarrollo profesional docente para la mejora escolar. Un estudio de caso en el municipio de Colina, Chile. Doctoral thesis, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, 25th January 2021. http://hdl.handle.net/10803/671984. 1080. [Google Scholar]

- Gronn, P. Distributed Leadership as a unit of analysis. The Lead. Quarterly 2002, 13, 423–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacBeath, J. Leadership as distributed: a matter of practice. Sch. Lead. & Manag. 2005, 25, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacBeath, J. No lack of principles: leadership development in England and Scotland. Sch. Lead. & Manag. 2011, 31, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, G. Analyzing Qualitative Data, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: California, United States, 2018; pp. 1–232. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, Sh.; Grenier, R. Qualitative Research in Practice. Examples for discussion and analysis, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, United States, 2019; pp. 1–480. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. & Poth, C. Qualitative inquiry & research design. Choosing among five approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: California, United States, 2018; pp. 1–488. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R. Investigación con estudio de casos, 6th ed.; Ediciones Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2022; pp. 1–153. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research methods in education, 8th ed.; Routledge: New York, United States, 2018; pp. 1–944. [Google Scholar]

- MINEDUC. Marco para la Buena Dirección y el Liderazgo Escolar, 1st ed.; Editora Maval: Santiago, Chile, 2015; pp. 1–44, https://n9.cl/nkwmg. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, United States, 2000; pp. 1–282. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. With constructivist grounded theory you can’t hide: Social justice research and critical inquiry in the public sphere. Quali. Inquiry, 2020, 26, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, A. The Varieties of Grounded Theory, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications: California, United States, 2019; pp. 1–152. [Google Scholar]

- Liska, L.; Seide, K. Coding for Grounded Theory. In The SAGE Handbook Current Developments in Grounded Theory, 1st ed.; Bryant, A., Charmaz, K., Eds.; SAGE Publications: California, United States, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 167–185. [Google Scholar]

| Traditional leadership | Distributed leadership |

|---|---|

| Specialized role | Shared influence process |

| Leadership as a persona characteristic | Leadership as a social practice |

| Leadership as supervision of hierarchical control processes | Leadership that arises in interaction processes |

| Individualistic | Collaborative - participatory |

| Task delegation | Distribution of responsibilities |

| Hierarchical relationships | Symmetric relations |

| Responsibility lies with one person: school principal | Responsibility lies with the team: educational community |

| Rationalist-positivist paradigm | Descriptive-analytical or normative-prescriptive paradigm |

| Centralized power | Shared power |

| School | Typology | School principal’s code | Number of teacher leaders | Teacher leader’s code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| School A | Primary school | ADifem | 2 | ADL1fem |

| ADL2fem | ||||

| School B | BDifem | 3 | BDL1fem | |

| BDL2fem | ||||

| BDL3fem | ||||

| School C | CDifem | 3 | CDL1fem | |

| CDL2fem | ||||

| CDL3fem | ||||

| School D | DDifem | 2 | DDL1fem | |

| DDL2fem | ||||

| School E | High school | EDifem | 2 | EDL1mas |

| EDL2fem | ||||

| School F | Vocational Education and Training High school | FDimas | 3 | FDL1fem |

| FDL2mas | ||||

| FDL3mas | ||||

| Total: 21 participants | 6 school principals | 15 teacher leaders | ||

| Management of principals about school organisation | Development of the professional capacities of teacher leaders | Management of principals about coexistence and participation of teacher leaders |

|---|---|---|

| Identify teacher leaders | Know the role of the principal in promoting teachers’ professional development | Encourage relationship and interactions between principals and teacher leaders |

| Restructure the organisational conditions of the school | Support for teacher leaders in professional development | Fostering confidence with the school and self confidence |

| Creating opportunities for teachers’ professional development | Fostering the promotion of teacher leadership | Promoting collaborative work |

| Having a sense of school improvement | Empowering the teacher as a leader | Distributing leadership |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).