1. Introduction

Sulforaphane (SFN), an isothiocyanate of plant origin found in cruciferous vegetables, such as broccoli, presents potent antioxidant [

1] and immunomodulatory properties, such as anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic (including histone deacetylase inhibibitory action), anti-microbian, anti-Alzheimer, anti-diabetes effects [1-4]. These pleiotropic activities derive from their ability to influence multiple signaling pathways, highlighting the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) and hemoxigenase 1 (HO-1) pathways [

1,

5] in different immune cells, such as monocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes and dendritic cells (DCs) [

6]. In addition, these pathways have also been studied in microglia and neurons [

5,

7]. Specifically, it has been demonstrated that SFN activation of this signaling Nrf2 pathway in DCs produces their polarization towards a tolerogenic phenotype [8-11]. This is due to DCs are professional antigen-presenting cells (APC), and essential for interacting with naïve T lymphocytes [

12]. DCs through of a maturation process can modulate the tolerant or the effector immune responses mediated by different subtypes of T lymphocytes and the microenvironment [13-16]. We previously have demonstrated that DCs capacity to induce proliferation of specific lymphocytes from drugs or food allergic patients compared with other APCs, such as B cells, or monocytes, improving the in vitro diagnosis of this patients [13-15]. Moreover, our group have presented data in the characterization of pathway signaling in DCs or neutrophils [17-20]. Little is known about the initial steps mediated by the innate immune system after up-take of SFN nutraceutical and the T-lymphocyte-mediated response generated in a proinflammatory environment. As novel findings, in this study, we showed for the first time that SFN in an inflammatory environment could potentially reduce the type 2 immune response on human DCs. In this sense, we have studied the proliferation and modulation of the T-cell–mediated response in these experimental conditions. Therefore, we show that SFN in a proinflammatory environment exerts an important effect on DCs phenotypic changes, which induce T-cell activation, reducing the Th2 proliferative response and increasing the IL-10 levels in an

in vitro situation with LPS.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Subjects of Study

The biological samples used for this work were obtained from twelve healthy subjects older than 18 years. The samples collection was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospitales Universitarios Virgen Macarena – Virgen del Rocío (code: ID-SOL2022-21799) and, before it, each subject signed an informed consent for inclusion in the study.

2.2. Sample Collection and Cell Culture

Samples from controls were processed following current procedures immediately after their reception and kindly provided by the BBSSPA, unit HH.UU. Virgen Macarena – Virgen del Rocío. PBMCs and moDCs were obtained from peripheral blood (40mL) from the healthy subjects included in the study. PBMCs were isolated by centrifugation on a gradient with Ficoll (Sigma, Madrid, Spain) using standardized protocols. Monocytes were purified from PBMCs by positive selection with anti-CD14 magnetic microbeads following the manufacturer's protocol (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), showing a purity of more than 95%, as assessed by flow cytometry (data not shown). CD14

−cell fractions were frozen for further use. Monocytes (CD14

+ cells) were cultured in complete medium as described by us previously for the generation of monocyte derived DCs [

17].

2.3. Generation of DCs

Monocyte-derived DCs (moDCs) were generated from CD14

+ monocytes as described [

21] by culturing them in complete medium adding 200 ng/mL GM-CSF and 100 ng/mL IL-4 (both from R&D Systems Inc, Minneapolis, MN) at 5% CO

2 at 37 °C as described [

17].

2.4. Cytotoxicity Assay

moDCs and THP-1-cells seeded in 96-well plates (5 × 104 cells/well) were incubated in presence or absence of 100ng/mL LPS of Escherichia coli0127: B8 (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) as positive control of chronic inflammation and, 10, 20, and 30 μM SFN (Sigma-Aldrich) nutraceutical of study, for 48 h. In addition, the THP-1 was included as model of cancer cell line, since it is monocytes isolated from peripheral blood from an acute monocytic leukemia patients. At the end of the exposure time, the effect on cell growth/viability was analysed by flow cytometry using LIVE/DEAD™ viability kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell survival was measured as the percentage of alive cells (viability %) compared with non-treated control cells.

2.5. Activation Assays of DCs

On day 5, moDCs and THP-1 were seeded in 96-well plates (5 × 10

4 cells/well) and treated with 10µM SFN during 48 h, which showed to be the optimal concentration for moDCs maturation and proved to be non-cytotoxic effects, in presence or absence of 100 ng/mL LPS, which induce a strong inflammatory response as model of chronic inflammatory diseases [

22].

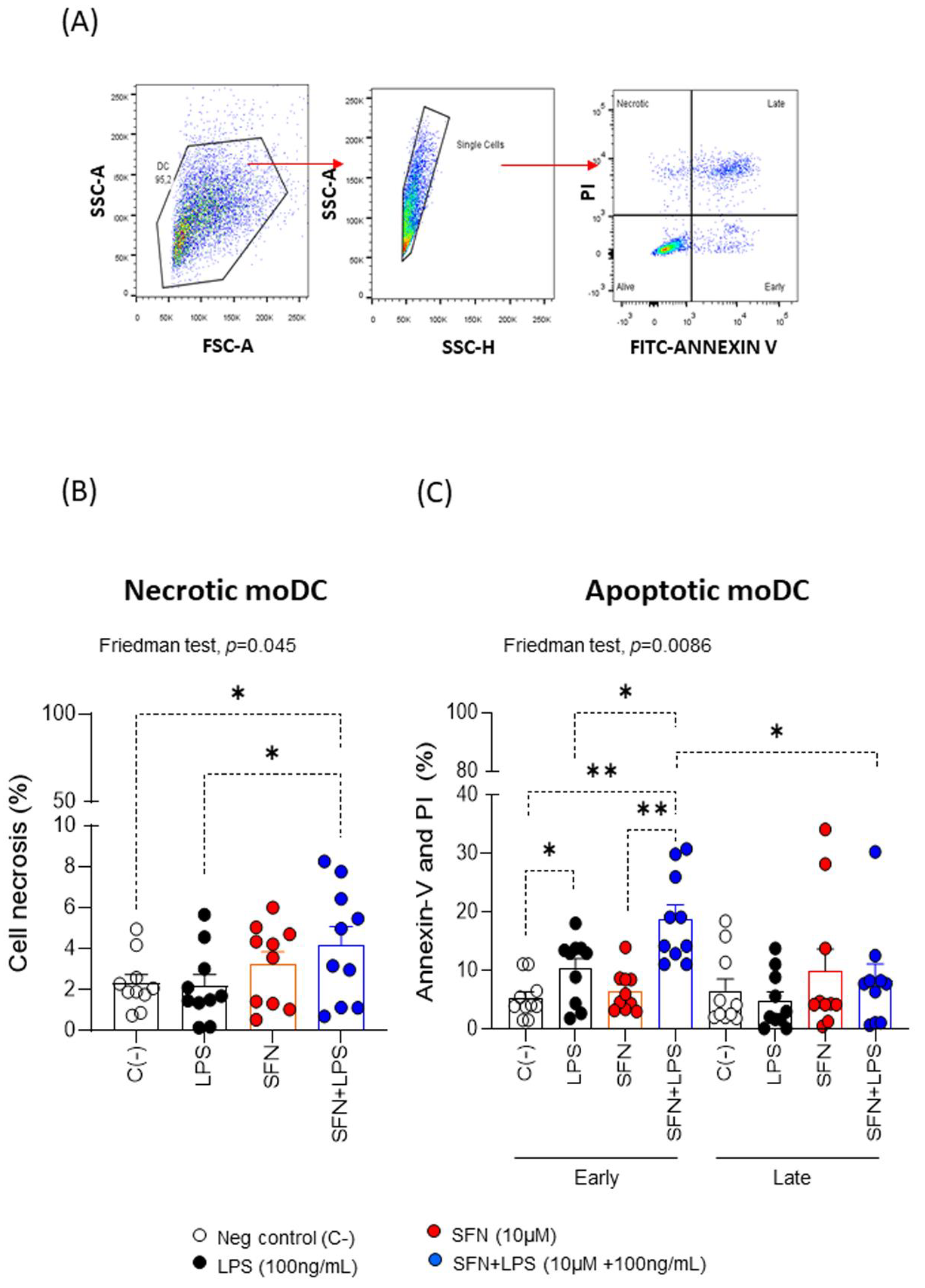

2.6. Apoptosis Assays

To detect the type of cell death that SFN can trigger, the FITC annexin V apoptosis detection kit (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) was used, following manufacturer instructions. Briefly, first, moDCs and THP-1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (5 × 104 cells/well) and treated with 10µM SFN and/or LPS during 48 h. Then, samples were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 15 minutes with FITC annexin V and Propidium Iodure (PI). Cells were acquired by using MACSQuant VYB flow cytometry (Miltenyi Biotec) and data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR). Results were expressed as the percentage of positive cells.

2.7. Autophagy Assay

Treated or nontreated moDCs (5 × 104 cells/well) were collected for the detection of autophagy after 48 h of culture at 37ºC, 5% CO2. Cells were washed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10 min at RT with gentle shaking. Then, cells were permeabilized with rinse buffer (PBS, 20 mM tris-HCl, 0.15 M NaCl and 0.05% tween-20) and incubated at room temperature and with gentle shaking for 30 min. Cells were washed with blocking solution (PBS and 3% BSA). Next, cells were incubated with LC3B-APC antibody (Novus Biologicals) for 30 minutes in dark, at room temperature. Finally, cells were acquired by flow cytometry and analyzed with FlowJo software, as previously we described. Fold change was calculated for LC3B (% LC3B expression on stimulated moDCs / % LC3B expression on unstimulated moDCs).

2.8. Phenotypic Analysis of moDCs

Treated or nontreated moDCs (5 × 104 cells/well) were incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature with specific mAbs (HLA-DR–FITC, PD-L1-PE, CD86-PerCP, CD80-PE-Cy7, and CD83-APC (Biolegend) or with an isotype-matched control (data not shown). Cells were acquired by flow cytometry and analyzed with FlowJo software, as previously we described. Results were expressed as fold change of the percentages of expression for each surface marker on moDCs. Fold change was calculated for each marker as (% marker expression on stimulated moDCs / % marker expression on unstimulated moDCs).

2.9. Specific Proliferative Response

The specific proliferation of different lymphocyte subpopulations was evaluated using, as APCs, autologous moDCs pre-stimulated with 10 µM SFN in presence or absence of LPS for 48 h previously described. Proliferation was determined using a 5,6- carboxyfluorescein diacetate N-succinimidyl ester (CFSE) dilution assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A total of 1.5 × 10

6 /mL pre-labeled CD14

-cells were cultured with moDCs pre-stimulated in different experimental combinations (10:1 ratio) at a final volume of 250 μL of complete medium in 96-well plates for 6 days at 37 °C and 5% CO

2. Moreover, 10 μg/mL phytohemaglutinin (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as positive proliferative control and unstimulated moDCs as negative proliferative control. The proliferative responses were assessed by flow cytometry, analyzing CFSE

low expression in the different cell subsets as T-lymphocytes (CD3

+CD4

+T-, CD3

+CD4

+CRTH2

+Th2-, CD3

+CD4

+CRTH2

-Th9- and CD3

+CD4

+CD25

+CD127

- as Treg-cells). For more details of the fluorescent antibodies used see

Table S1 in Supplementary Material. Results were expressed as fold change of the percentages of CFSE

low for each subpopulation cell. Fold change was calculated for each cell subset as (% CFSE

low stimulated moDCs:CD14

- PBMCs / % CFSE

low unstimulated moDCs:CD14

- PBMCs).

2.10. Cytokine Production

Cytokine production (IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-10, IL-13 and IFNγ) from supernatant cell cultures (moDCs: CD14- PBMCs) collected after 7 days, was determined with a human ProcartaPlex Multiplex Immunoassays kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), following the manufacturer’s indications and detected in a Bio-Plex 200 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Data were analyzed using Bio-Plex Data Analysis Software (Bio-Rad). Results were represented as fold change for the concentration of each cytokine.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

The data were analysed using the Shapiro−Wilk test to determine the normal distribution, but the most variables were fitted to non-parametric distribution. The Friedman test was used to find significant differences due to the effects of different LPS, SFN and SFN+LPS between subjects from the same group. If the Friedman test indicated the existence of significant differences between treatments, we used the Wilcoxon signed rank test to compare between pairs of related samples, resulting in three post hoc tests (LPS vs SNF; LPS vs SFN plus LPS; and SFN vs SFN plus LPS). The significant differences were reported as (*) and (**), representing a p-value < 0.05 and < 0.01, respectively. The statistical analysis was carried out using Graphpad Prism7.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sulforaphane Induces Apoptosis on Inflammatory moDC

The SFN optimal concentrations used on moDCs from healthy subjects were analyzed by a dose-response curve assay. After 48 h in culture, we measured the percentage of viable moDCs exposure of increasing doses (10, 20 and 30 μM) SFN (

Figure S1A). We assessed viable treated-moDCs by binding a fluorescent dye to free amines inside and the cell membrane of the necrotic bodies, through the flow cytometer. When we compared moDCs without stimulation, or stimulated with SFN increasing doses, we observed that the cell viability was strongly engaged from 20 μM SFN (

Figure S1A). This is in line with data from Wang lab [

10], although they described that the inhibition of cell viability slightly started at 25 μM. We selected the 10 μM SFN as optimal

in vitro assay doses, because at this concentration, the moDCs viability did not affect the overall moDCs viability (

Figure S1B). Similarly, when we added 100 ng/mL LPS as positive control of a chronic inflammation, the moDCs viability was not affected. Instead, when we added 10 μM SFN after inducing the moDCs chronic inflammation by adding 100 ng/mL LPS, we observed a significant decrease of the moDCs viability respect to negative and positive controls (

Figure S1B). We suggest that under a chronic inflammation, SFN may act on affected moDCs promoting apoptosis. This is in line with authors who proposed that the pharmacological induction of apoptosis may lead to entirely new therapies for chronic inflammatory diseases [

23,

24]. Moreover, Carstensen et al. demonstrated that exposure to an inflammatory environment maintained over time induces apoptosis in DCs [

25], and in our study, this action, could be enhanced by an anti-inflammatory agent such as SFN.

To further characterize the type of cell death that SFN can trigger on moDCs and LPS-stimulated moDCs we measured apoptosis (

Figure 1A). The results revealed that SFN alone induced cell apoptosis increasing doses (data do not show), both early and late apoptosis. Moreover, we observed that the analysis of the SFN effect in an inflammatory microenvironment induced by LPS indicated that SFN induces significant changes in necrosis, and apoptosis on moDCs (

Figure 1B and 1C). This could be related to studies that have shown that in cancer cells with an inflammatory profile, SFN could induce apoptosis [

26]. To confirm these results, we studied the effect of SNF on THP-1 cells, in a non- and -inflammatory microenvironment by LPS, and the data show that SFN under this inflammatory microenvironment induces necrosis, and apoptosis on cancer cell line (Figure SI2). Our findings SFN-induced apoptosis in an inflammatory microenvironment may be a promising strategy for cancer control.

3.2. Sulforaphane Decreases Autophagy in Inflammatory moDCs

Autophagy is involved in the tolerogenic and immunogenic functions of DCs depending on the micro-environment [

27]. Increased autophagy was detected in macrophages and DCs upon virus infection [

28,

29]. However, Blanchet et al. observed that HIV-1 inhibited autophagy in DCs but LPS increased autophagy [

30] LPS-treated DCs under hypoxia increased autophagy promoting DCs survival [

31]. Our results showed a chronic inflammatory environment LPS-induced increased autophagy on moDCs. This is in line with previous studies [

30], but SFN (alone) did not alter autophagy. However, SFN significant decreased the induced-autophagy by LPS (

Figure 2). Knowledge about the involvement of autophagy in DCs has been increasing, [

27], however the understanding of the functioning of autophagy in tolerogenic or immunogenic DCs and its interconnection with apoptosis need a deeper comprehension.

Considering all results, it is tempting to speculate that in an inflammatory profile, as occurs in cancer pathologies, there are an inhibition of autophagy enhancing SFN-induced apoptosis [

26,

32]. These findings provide a premise for use of nutraceutical agents for treatment of inflammatory diseases.

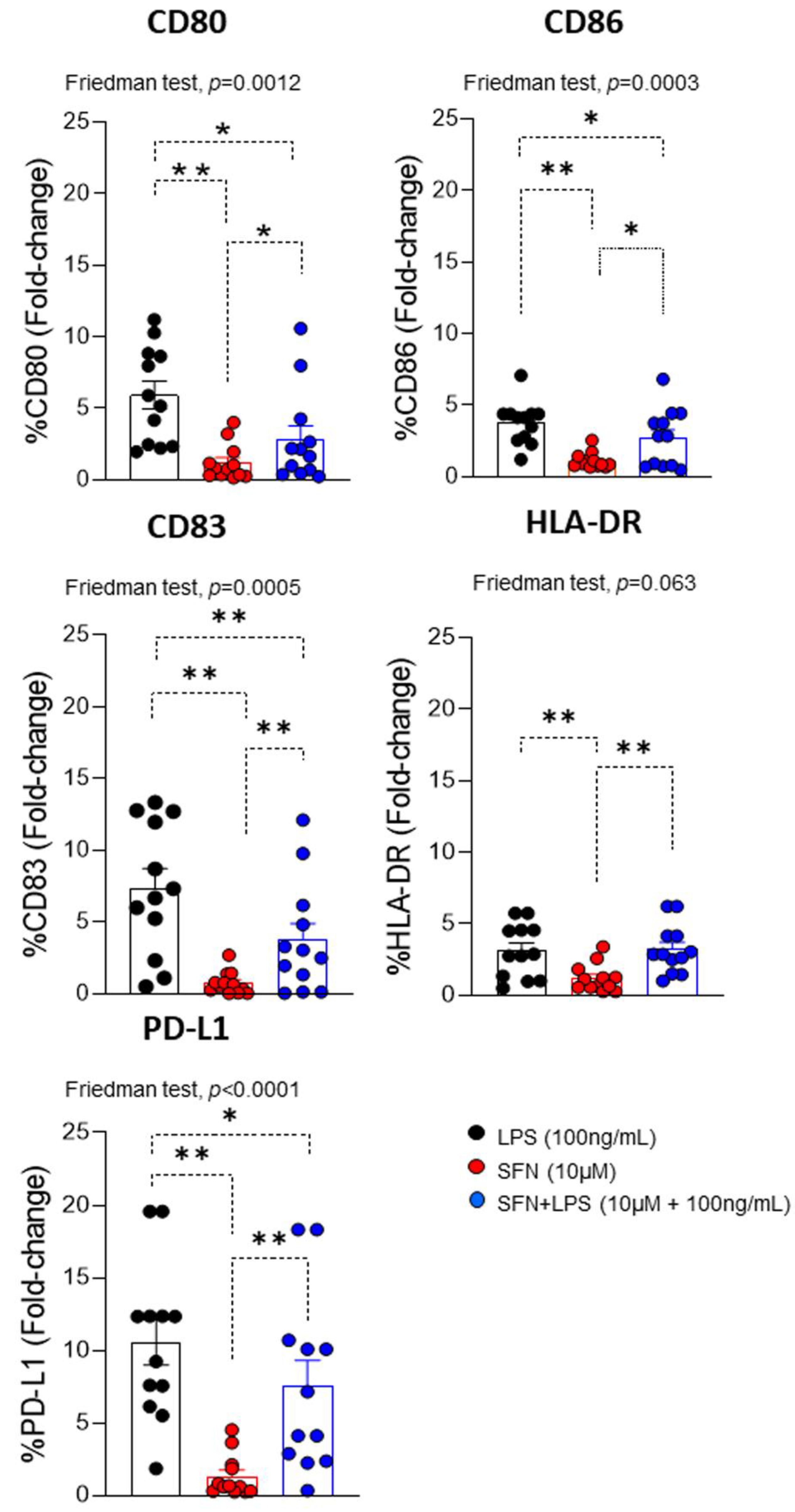

3.3. Sulforaphane Induces Phenotypic Changes in Inflammatory moDCs

In an inflammatory microenvironment induced by LPS, moDCs can be activated by it. This leads to changes in the expression of different co-stimulatory markers (CD80, CD86, CD83, HLA-DR and PD-L1), which promote the immune response and recruit other types of immune cells to the site of inflammation, as T lymphocytes [

33]. Evaluation of LPS-induced maturational phenotypic changes in the expression of cell surface markers of activation/regulation (CD83 and PD-L1), maturation (CD80 and CD86), and antigen presentation (HLA-DR) indicated that, compared to SFN, there was a significant increase in all markers.

However, SFN-stimulated moDCs had a down regulation of these markers (

Figure 2). This effect agrees with previous studies in which SFN was shown to inhibit the differentiation of immature to mature moDCs through down regulation of CD40, CD80, and CD86 expression [

34]. In addition, the analysis of the effect of the SFN in an inflammatory microenvironment induced by LPS indicated that SFN down-regulated the expression of CD80, CD83, CD86 and PD-L1 compared to LPS (alone) (

Figure 2). Currently, is described that LPS stimulation increase PD-L1 expression in cancer cells [

35].

Moreover, ours results indicate that SFN in an inflammatory microenvironment could modulate the PD-L1 pathway and could provide antitumor effect. Take together present data, it suggested that SFN showed a protective role in presence of LPS. In fact, SFN inhibit the LPS-stimulated inflammatory response in human monocytes [

36]. This capacity to modulate the moDCs phenotype in an inflammatory microenvironment, has also been described for other nutraceuticals, such as apigenin [

37].

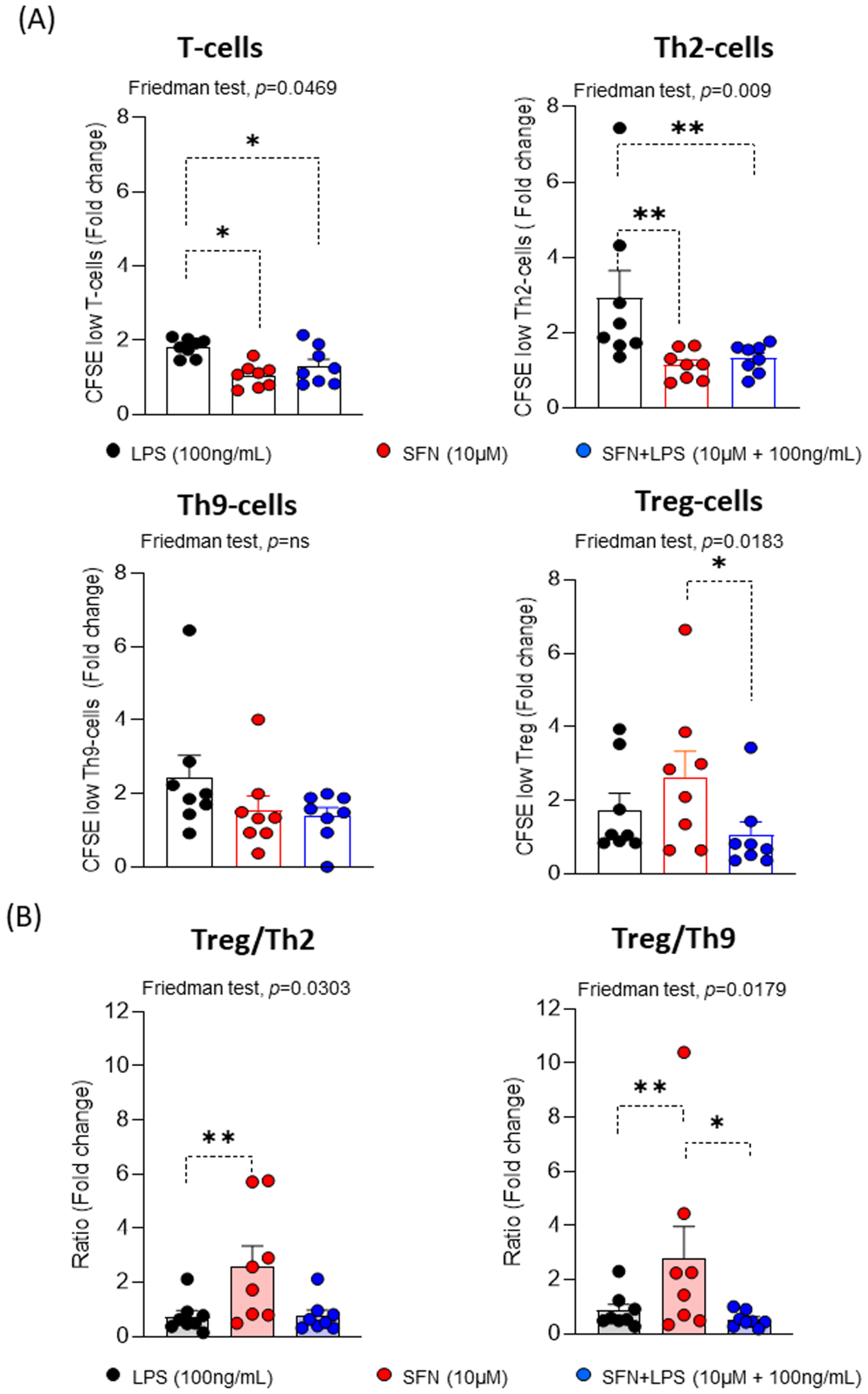

3.4. Sulforaphane Reduces the Th2 Proliferative Response under Inflammatory Microenvironment

Our findings showed that SFN in an inflammatory environment modulates the moDCs activation and maturation, suggested that they might be involved in the next steps of the immune response, where moDCs interact with T lymphocytes. To examine this possibility, we determined the proliferative response using pre-stimulated homologous moDCs under different experimental conditions. For this, different subpopulations of T lymphocytes (CD3+CD4+T-, CRTH2+Th2-, CRTH2-Th9- and Treg-cells) were assayed.

Ours results indicated that SFN independently of the inflammatory microenvironment led to significantly decreased CD3

+CD4

+T- and CRTH2

+Th2-cell proliferation compared to LPS, while there are no observed changes in the proliferative responses of the CRTH2-Th9-cells (

Figure 4). These results suggest that the SFN in inflammatory microenvironment induces a reduction of the immune response type 2. Regarding this, it has been described that SFN suppressed the levels of GATA3 and IL-4 expression in an asthma animal model, demonstrating the regulation of Th2 immune responses [

38]. However, the proliferative response of Treg-cells was significant increased under the SFN stimulation compared to SFN+LPS. Therefore, the Treg/Th2-cells and Treg/Th9-cells ratios were significantly higher in presence of SFN than SFN+LPS, suggesting that SFN display anti-inflammatory features and induce a Treg balance such as it has been described for other nutraceuticals [

39,

40].

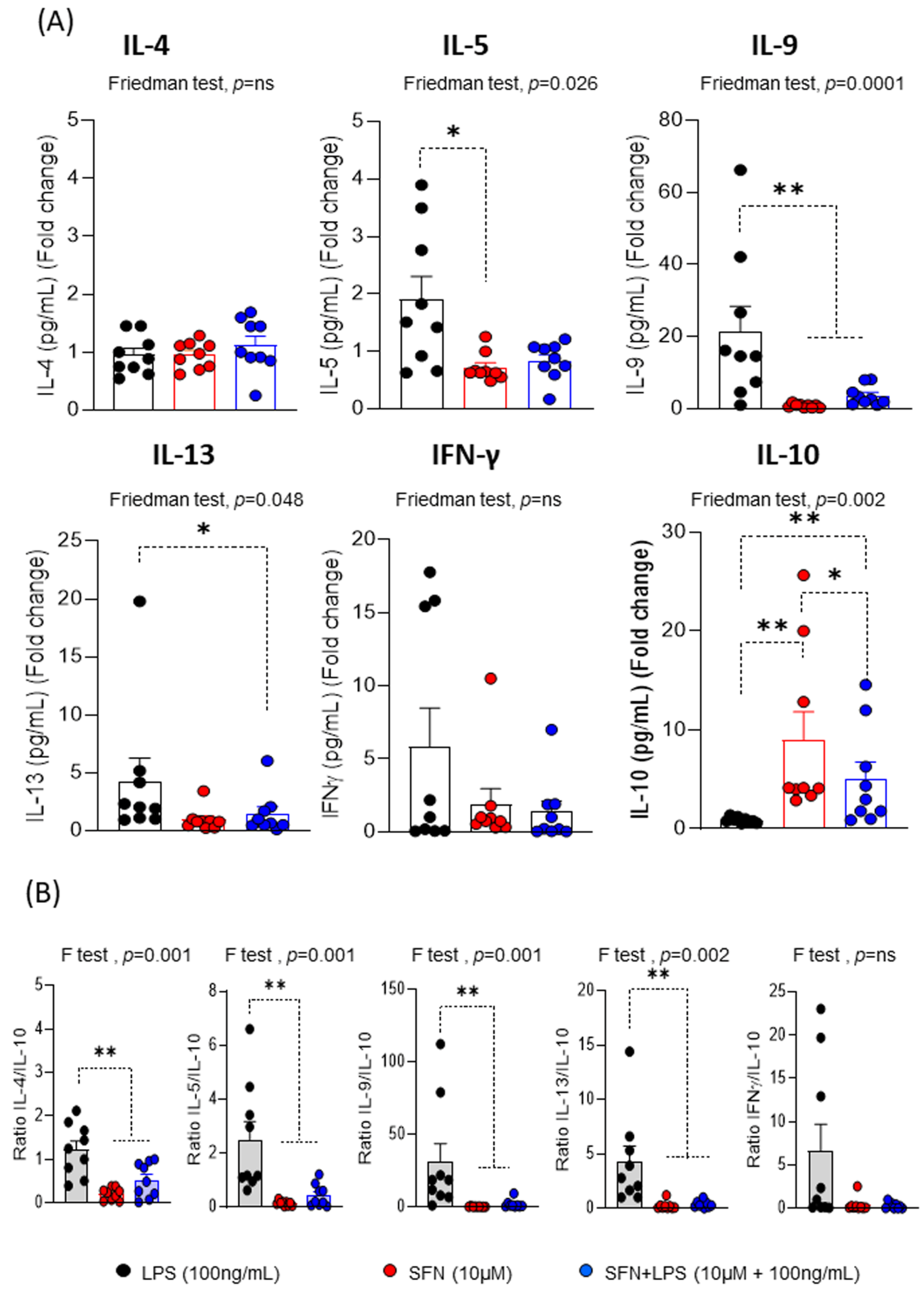

Regarding the cytokine profile produced during the proliferative response, the most interesting results indicated that SFN in the inflammatory microenvironment induced a decrease in the levels of IL-5, IL-9, IL-13 and IFNγ compared to LPS, being only significant for IL-9 and IL-13 (

Figure 5A). These changes that are observed in the levels of inflammatory and proinflammatory cytokines consistent with the ability of SFN to suppress type 2 cytokines in an asthma animal model [

38].

In addition, we demonstrated that SFN inhibited IFN-γ levels [

41], it as has been demonstrated by other natural substances with anti-inflammatory and/or immunomodulatory activities, such as curcumin [

42] or sanguinarine [

43]. Our results indicate that SFN has a potent effect on the inflammatory and proinflammatory pattern induced by T-cells. After 1 h of LPS stimulation, SFN significantly increased IL-10 production compared to LPS (

Figure 5A). Moreover, the IL-4/IL-10, IL-5/IL-10, IL-9/IL-10 and IL-13/10 ratios were significantly lower in presence of SFN than LPS, suggesting that SFN display anti-inflammatory feature (

Figure 5B). Therefore, that SFN stimulated a stable regulatory response under inflammatory condition, as demonstrated by their lower production of pro- and inflammatory cytokines. Supporting these data, SFN attenuates intestinal inflammation by increasing IL-10 levels in an animal model [

44].

These data suggested that SFN under inflammatory condition has the capacity to modulate the moDCs and generated a specific immunological response with regulatory immunological pattern and the suppression of Th2 effector cells.

4. Conclusions

The present study shows that SFN exerts protective effects against LPS-induced inflammation through modulation of moDCs/T-cells. In this regard, SFN interacts with moDCs and can reduce autophagy and increase apoptosis in the chronic inflammatory microenvironment, as it has been described to cancer. Furthermore, under these conditions, SFN reduces the phenotypic marker of moDCs and the Th2 proliferative response with a reduction of anti-inflammatory cytokines and an increase of regulatory cytokines profile. Therefore, SFN may be a potential candidate for use in the treatment of pathologies with an inflammatory profile. Future studies will be necessary to understand the mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of SFN on the inflammatory process.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S. L-E., F. P.; methodology, L. F.-P., M. B.-P., V. M., B. G.; formal analysis, S. M.-D. F. P., G. A., C.S.-M.; investigation, H. B.; resources, S. L-E., F. P.; writing – original draft preparation, S. L-E., F. P.; writing – review and editing, G. A., C.S.-M., F. S.; funding acquisition, G. A., C.S.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Grant Proyect-202200000421 VII Plan Propio de Investigación y Transferencia, University of Seville and by Ministry of Science and Innovation trough research Ramon y Cajal program (RYC2021-031256-I) from Spain.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved Research Ethics Committee of Hospitales Universitarios Virgen Macarena-Virgen del Rocio (projects ID-SOL2022-21799).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been approved by obtained from the healthy subjects to publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank to healthy subjects and the Biobank Nodo Hospital Virgen Macarena (Biobanco del Sistema Sanitario Público de Andalucía) integrated in the Spanish National biobanks Network (PT20/00069) supported by ISCIII and FEDER funds, and Modesto Carballo (CITIUS-Research, Technology, and Innovation Center-Seville University for the assistance with the flow cytometry (MACSQuant VYB flow cytometry).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| APC |

antigen-presenting cells |

| CFSE |

carboxyfluorescein diacetate N-succinimidyl ester |

| DCs |

dendritic cells |

| HO-1 |

Hemoxigenase 1 |

| LPS |

Lipopolysaccharide |

| moDCs |

monocyte-derived DCs |

| Nrf2 |

Factor erythroid 2-related factor-2 |

| SFN |

Sulforaphane. |

References

- Mangla, B.; Javed, S.; Sultan, M.H.; Kumar, P.; Kohli, K.; Najmi, A.; Alhazmi, H.A.; Al Bratty, M.; Ahsan, W. Sulforaphane: A review of its therapeutic potentials, advances in its nanodelivery, recent patents, and clinical trials. Phytother Res 2021, 35, 5440–5458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannucci, E.; Rimm, E.B.; Liu, Y.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C. A prospective study of cruciferous vegetables and prostate cancer. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 2003, 12, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, T.L.; Saha, S.; Bernuzzi, F.; Savva, G.M.; Troncoso-Rey, P.; Traka, M.H.; Mills, R.D.; Ball, R.Y.; Mithen, R.F. Accumulation of Sulforaphane and Alliin in Human Prostate Tissue. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J. Pre-Clinical Neuroprotective Evidences and Plausible Mechanisms of Sulforaphane in Alzheimer's Disease. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subedi, L.; Lee, J.H.; Yumnam, S.; Ji, E.; Kim, S.Y. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Sulforaphane on LPS-Activated Microglia Potentially through JNK/AP-1/NF-kappaB Inhibition and Nrf2/HO-1 Activation. Cells 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahn, A.; Castillo, A. Potential of Sulforaphane as a Natural Immune System Enhancer: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraft, A.D.; Johnson, D.A.; Johnson, J.A. Nuclear factor E2-related factor 2-dependent antioxidant response element activation by tert-butylhydroquinone and sulforaphane occurring preferentially in astrocytes conditions neurons against oxidative insult. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2004, 24, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geisel, J.; Bruck, J.; Glocova, I.; Dengler, K.; Sinnberg, T.; Rothfuss, O.; Walter, M.; Schulze-Osthoff, K.; Rocken, M.; Ghoreschi, K. Sulforaphane protects from T cell-mediated autoimmune disease by inhibition of IL-23 and IL-12 in dendritic cells. Journal of immunology 2014, 192, 3530–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Barajas, B.; Wang, M.; Nel, A.E. Nrf2 activation by sulforaphane restores the age-related decrease of T(H)1 immunity: role of dendritic cells. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2008, 121, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Petrikova, E.; Gross, W.; Sticht, C.; Gretz, N.; Herr, I.; Karakhanova, S. Sulforaphane Promotes Dendritic Cell Stimulatory Capacity Through Modulation of Regulatory Molecules, JAK/STAT3- and MicroRNA-Signaling. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11, 589818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Zhang, W.; Cui, H.; He, W.; Lu, S.; Jia, S.; Zhao, M. Sulforaphane Ameliorates the Severity of Psoriasis and SLE by Modulating Effector Cells and Reducing Oxidative Stress. Frontiers in pharmacology 2022, 13, 805508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallusto, F.; Lanzavecchia, A. The instructive role of dendritic cells on T-cell responses. Arthritis Res 2002, 4 Suppl 3, S127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Pena, R.; Lopez, S.; Mayorga, C.; Antunez, C.; Fernandez, T.D.; Torres, M.J.; Blanca, M. Potential involvement of dendritic cells in delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions to beta-lactams. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2006, 118, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Santamaria, R.; Bogas, G.; Palomares, F.; Salas, M.; Fernandez, T.D.; Jimenez, I.; Barrionuevo, E.; Dona, I.; Torres, M.J.; Mayorga, C. Dendritic cells inclusion and cell-subset assessment improve flow-cytometry-based proliferation test in non-immediate drug hypersensitivity reactions. Allergy 2021, 76, 2123–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palomares, F.; Ramos-Soriano, J.; Gomez, F.; Mascaraque, A.; Bogas, G.; Perkins, J.R.; Gonzalez, M.; Torres, M.J.; Diaz-Perales, A.; Rojo, J. , et al. Pru p 3-Glycodendropeptides Based on Mannoses Promote Changes in the Immunological Properties of Dendritic and T-Cells from LTP-Allergic Patients. Molecular nutrition & food research 2019, 63, e1900553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Madrigal, C.; Lopez, S.; Grao-Cruces, E.; Millan-Linares, M.C.; Rodriguez-Martin, N.M.; Martin, M.E.; Alba, G.; Santa-Maria, C.; Bermudez, B.; Montserrat-de la Paz, S. Dietary Fatty Acids in Postprandial Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins Modulate Human Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cell Maturation and Activation. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, S.; Gomez, E.; Torres, M.J.; Pozo, D.; Fernandez, T.D.; Ariza, A.; Sanz, M.L.; Blanca, M.; Mayorga, C. Betalactam antibiotics affect human dendritic cells maturation through MAPK/NF-kB systems. Role in allergic reactions to drugs. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 2015, 288, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, G.; El Bekay, R.; Chacon, P.; Reyes, M.E.; Ramos, E.; Olivan, J.; Jimenez, J.; Lopez, J.M.; Martin-Nieto, J.; Pintado, E. , et al. Heme oxygenase-1 expression is down-regulated by angiotensin II and under hypertension in human neutrophils. Journal of leukocyte biology 2008, 84, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, G.; Reyes-Quiroz, M.E.; Saenz, J.; Geniz, I.; Jimenez, J.; Martin-Nieto, J.; Pintado, E.; Sobrino, F.; Santa-Maria, C. 7-Keto-cholesterol and 25-hydroxy-1 cholesterol rapidly enhance ROS production in human neutrophils. European journal of nutrition 2016, 55, 2485–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa-Maria, C.; Lopez-Enriquez, S.; Montserrat-de la Paz, S.; Geniz, I.; Reyes-Quiroz, M.E.; Moreno, M.; Palomares, F.; Sobrino, F.; Alba, G. Update on Anti-Inflammatory Molecular Mechanisms Induced by Oleic Acid. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallusto, F.; Lanzavecchia, A. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. The Journal of experimental medicine 1994, 179, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Alcaraz, A.J.; Martinez-Sanchez, M.A.; Garcia-Penarrubia, P.; Martinez-Esparza, M.; Ramos-Molina, B.; Moreno, D.A. Analysis of the anti-inflammatory potential of Brassica bioactive compounds in a human macrophage-like cell model derived from HL-60 cells. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie 2022, 149, 112804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.P. Resolution of chronic inflammation by therapeutic induction of apoptosis. Trends in pharmacological sciences 1996, 17, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, F.J.; Hayes, I.; Cotter, T.G. Targeting inflammatory diseases via apoptotic mechanisms. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2003, 3, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carstensen, L.S.; Lie-Andersen, O.; Obers, A.; Crowther, M.D.; Svane, I.M.; Hansen, M. Long-Term Exposure to Inflammation Induces Differential Cytokine Patterns and Apoptosis in Dendritic Cells. Frontiers in immunology 2019, 10, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanematsu, S.; Uehara, N.; Miki, H.; Yoshizawa, K.; Kawanaka, A.; Yuri, T.; Tsubura, A. Autophagy inhibition enhances sulforaphane-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Anticancer research 2010, 30, 3381–3390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghislat, G.; Lawrence, T. Autophagy in dendritic cells. Cellular & molecular immunology 2018, 15, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, A.H.; Lee, D.C.; Yuen, K.Y.; Peiris, M.; Lau, A.S. Cellular response to influenza virus infection: a potential role for autophagy in CXCL10 and interferon-alpha induction. Cellular & molecular immunology 2010, 7, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, F.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Z.; Cai, Z.; Yu, L.; Xu, F.; Wang, J.; Zhu, W.; Lu, H. Autophagy is involved in regulating the immune response of dendritic cells to influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 infection. Immunology 2016. [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, F.P.; Moris, A.; Nikolic, D.S.; Lehmann, M.; Cardinaud, S.; Stalder, R.; Garcia, E.; Dinkins, C.; Leuba, F.; Wu, L. , et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 inhibition of immunoamphisomes in dendritic cells impairs early innate and adaptive immune responses. Immunity 2010, 32, 654–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaci, S.; Aldinucci, C.; Rossi, D.; Giuntini, G.; Filippi, I.; Ulivieri, C.; Marotta, G.; Sozzani, S.; Carraro, F.; Naldini, A. Hypoxia Shapes Autophagy in LPS-Activated Dendritic Cells. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11, 573646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman-Antosiewicz, A.; Johnson, D.E.; Singh, S.V. Sulforaphane causes autophagy to inhibit release of cytochrome C and apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer research 2006, 66, 5828–5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura, E.; Amigorena, S. Inflammatory dendritic cells in mice and humans. Trends in immunology 2013, 34, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, X.; Proll, M.; Neuhoff, C.; Zhang, R.; Cinar, M.U.; Hossain, M.M.; Tesfaye, D.; Grosse-Brinkhaus, C.; Salilew-Wondim, D.; Tholen, E. , et al. Sulforaphane epigenetically regulates innate immune responses of porcine monocyte-derived dendritic cells induced with lipopolysaccharide. PloS one 2015, 10, e0121574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xia, J.Q.; Zhu, F.S.; Xi, Z.H.; Pan, C.Y.; Gu, L.M.; Tian, Y.Z. LPS promotes the expression of PD-L1 in gastric cancer cells through NF-kappaB activation. Journal of cellular biochemistry 2018, 119, 9997–10004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, S.A.; Shelar, S.B.; Dang, T.M.; Lee, B.N.; Yang, H.; Ong, S.M.; Ng, H.L.; Chui, W.K.; Wong, S.C.; Chew, E.H. Sulforaphane and its methylcarbonyl analogs inhibit the LPS-stimulated inflammatory response in human monocytes through modulating cytokine production, suppressing chemotactic migration and phagocytosis in a NF-kappaB- and MAPK-dependent manner. International immunopharmacology 2015, 24, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginwala, R.; Bhavsar, R.; Moore, P.; Bernui, M.; Singh, N.; Bearoff, F.; Nagarkatti, M.; Khan, Z.K.; Jain, P. Apigenin Modulates Dendritic Cell Activities and Curbs Inflammation Via RelB Inhibition in the Context of Neuroinflammatory Diseases. Journal of neuroimmune pharmacology : the official journal of the Society on NeuroImmune Pharmacology 2021, 16, 403–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, J.W.; Lee, C.M.; Kim, Y.D.; Chung, S.W.; Jung, I.D.; Noh, K.T.; Park, J.W.; Heo, D.R.; Shin, Y.K. , et al. Sulforaphane inhibits the Th2 immune response in ovalbumin-induced asthma. BMB Rep 2012, 45, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginwala, R.; McTish, E.; Raman, C.; Singh, N.; Nagarkatti, M.; Nagarkatti, P.; Sagar, D.; Jain, P.; Khan, Z.K. Apigenin, a Natural Flavonoid, Attenuates EAE Severity Through the Modulation of Dendritic Cell and Other Immune Cell Functions. Journal of neuroimmune pharmacology : the official journal of the Society on NeuroImmune Pharmacology 2016, 11, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrarca, C.; Viola, D. Redox Remodeling by Nutraceuticals for Prevention and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Inflammation. Antioxidants 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.K.; Ramalingam, M.; Kim, S.; Jang, B.C.; Park, J.W. Sulforaphane inhibits the interferon-gamma-induced expression of MIG, IP-10 and I-TAC in INS-1 pancreatic beta-cells through the downregulation of IRF-1, STAT-1 and PKB. Int J Mol Med 2017, 40, 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, F.; Chen, H.; Han, L.; Jin, Y.; Wang, W. Curcumin attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced renal inflammation. Biological & pharmaceutical bulletin 2011, 34, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Fan, T.; Li, W.; Xing, W.; Huang, H. The anti-inflammatory effects of sanguinarine and its modulation of inflammatory mediators from peritoneal macrophages. European journal of pharmacology 2012, 689, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Jeffery, E.H.; Miller, M.J.; Wallig, M.A.; Wu, Y. Lightly Cooked Broccoli Is as Effective as Raw Broccoli in Mitigating Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis in Mice. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).