Introduction:

The use of information technologies (IT) in healthcare has been a controversial topic for decades [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The recent surge in the adoption of telemedicine has brought many historical debates to public attention. As the atmosphere surrounding remote healthcare delivery begins to stabilize, many questions arise as to systems for maintaining telemedicine technologies and programs that improve the human condition. The pace of technology innovation dramatically exceeds the capacity of traditional healthcare systems to implement new tools in a safe and effective manner [

6,

7]. This leads to a vicious cycle of patients and providers being inundated with cutting-edge solutions for healthcare, while regulators scramble to define the boundaries for vetting these solutions accordingly.

The first major spike in telemedicine utilization occurred in the 1960s when the United States government began investing in telecommunications to serve the healthcare needs of isolated populations [

8,

9]. A bias toward isolated and underserved populations persists today, and telemedicine has been frequently cited as a solution for confronting health disparities in rural and Native American communities [

10].

Broader commoditization of telemedicine occurred with the establishment of telemedicine conferences in the latter half of the 1970s, and the introduction of the internet redefining standards for IT in 1983 [

3,

7,

9]. However, up to the present day, the global adoption of telemedicine remains relatively slow. Commonly cited barriers to the widespread implementation of telemedicine include the lack of reimbursement and reliability [

8,

11,

12]. These two issues can go hand-in-hand with each other. For example, at this moment, we do not have separate accreditation processes for providers who wish to offer virtual medical services, including telemedicine [

8,

12,

13]. If it has not been validated that telemedicine appointments are performed to the same standards of care as traditional, in-person practice, then why impose equal reimbursement? In many ways, reimbursement can affect incentives pertaining to research or implementation of a clinically validated model.

Funding and support for digital health innovation have remained quite strong over the last decade and a half [

14]. In 2009, following the burst of the U.S. housing bubble and global financial crisis, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act allocated over

$25 billion in funds for digital healthcare and other health technologies [

15]. In 2016, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) awarded

$16 million in funding for the expansion of telehealth and other rural healthcare programs specifically [

16]. Beyond capital contributions, the overall sentiment of patients and providers suggest that telemedicine is here to stay. The 2021 Survey of America’s Physicians by the Physicians Foundation shows that 70% of respondents intend to incorporate telehealth as a regular part of their practice in the future [

17]. A survey published by Amwell in 2020 suggested that almost all providers intend to use telemedicine even when it is safe to see patients in person. Over half of the patients who responded to the survey expected to continue to use telemedicine at a greater frequency as a result of the pandemic [

18].

There is now an urgency to assure that valuable programs and technologies are recognized for the future of medicine. This is demonstrated by constant policymaking and a growing infrastructure surrounding the evaluation of telemedicine and other digital health technologies. The Center for Connected Health Policy publishes regular updates. Some of the most notable trends for 2022 include the expansion of services and types of providers that are eligible for reimbursement, implementation of practice standards, and licensure [

12]. Furthermore, the FDA has established the Digital Health Center of Excellence which is dedicated to advancing safe and effective digital health innovation through knowledge, networks, and regulatory systems [

19].

According to our review, very little work has been done to demonstrate end-users’ perceptions of telemedicine implementation in rural MN. Previous works have cited age, level of education, eHealth or computer literacy, bandwidth of dwelling, unawareness of the existence of telemedicine, high expectations of users, apathy, lack of access to a phone, socioeconomic status, gender, and preference for personal visits as end-user barriers to telemedicine [

4,

10,

20]. An additional systematic review further breaks down these barriers into internal (resistance, poor body language, and communication, negative perception of privacy and security) and external (slow internet speed, poor network signal, system difficulty to use, lack of organizational support, home obstructions), however, this review did not provide any insight to rural settings specifically [

11]. Furthermore, there has been substantial speculation about the future benefits of remote medical technologies for increasing access and equity of healthcare for isolated populations [

3,

4,

8]. Therefore, this study aims to provide a patient-centric view of emergency telemedicine implementation during the COVID-19 pandemic at a Primary Care clinic in rural MN. At this clinic, telemedicine services were rapidly implemented and then scaled back according to the severity of the situation surrounding COVID-19. Our research pertaining to the sudden shift to remote patient care during the pandemic will create a foundation for future studies regarding the remote provision of healthcare services. Additionally, the results may inform strategic changes to practice at this site and others throughout the state.

Methods:

This retrospective cohort study utilized a mail questionnaire to assess patient attitudes and behaviors regarding telemedicine during the emergency response to COVID-19. The target population was patients of a Primary Care clinic in eastern Minnesota. Descriptive statistics were used to assess respondents’ level of agreement with survey items scored on a 0-10 scale.

Setting: The host clinic is located in a rural town of about 2700 people in eastern Minnesota. The population is predominantly white with a median age of 40 years old and a median household income of about

$40,000. Most people drive themselves to work and experience an average commute time of 23 minutes which is comparable to the national average. The most common industries include manufacturing, accommodation and food services, and other service professions. Over 90% of the population has health coverage with about 30% covered by public assistance. Aside from the COVID-19 pandemic, mental health, obesity, and substance use are the leading public health issues with a lack of social connection and economic security indicated as additional areas of concern [

21,

22].

Participants: Individuals from this population were invited to participate in the study according to the inclusion criteria: Over 18 years of age and completed an audio-only telehealth appointment between January 2020 and March 2022. Patients with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementia (ADRD) were excluded from participating due to concerns about their capacity to engage with the study. A preliminary report of prospective participants was generated from the Electronic Medical Record (EMR) and filtered down to a final sample of 766 by eliminating patients with repeat listings, as well as those who were pronounced dead. Individuals from the final sample were mailed a research packet for enrollment via self-selection.

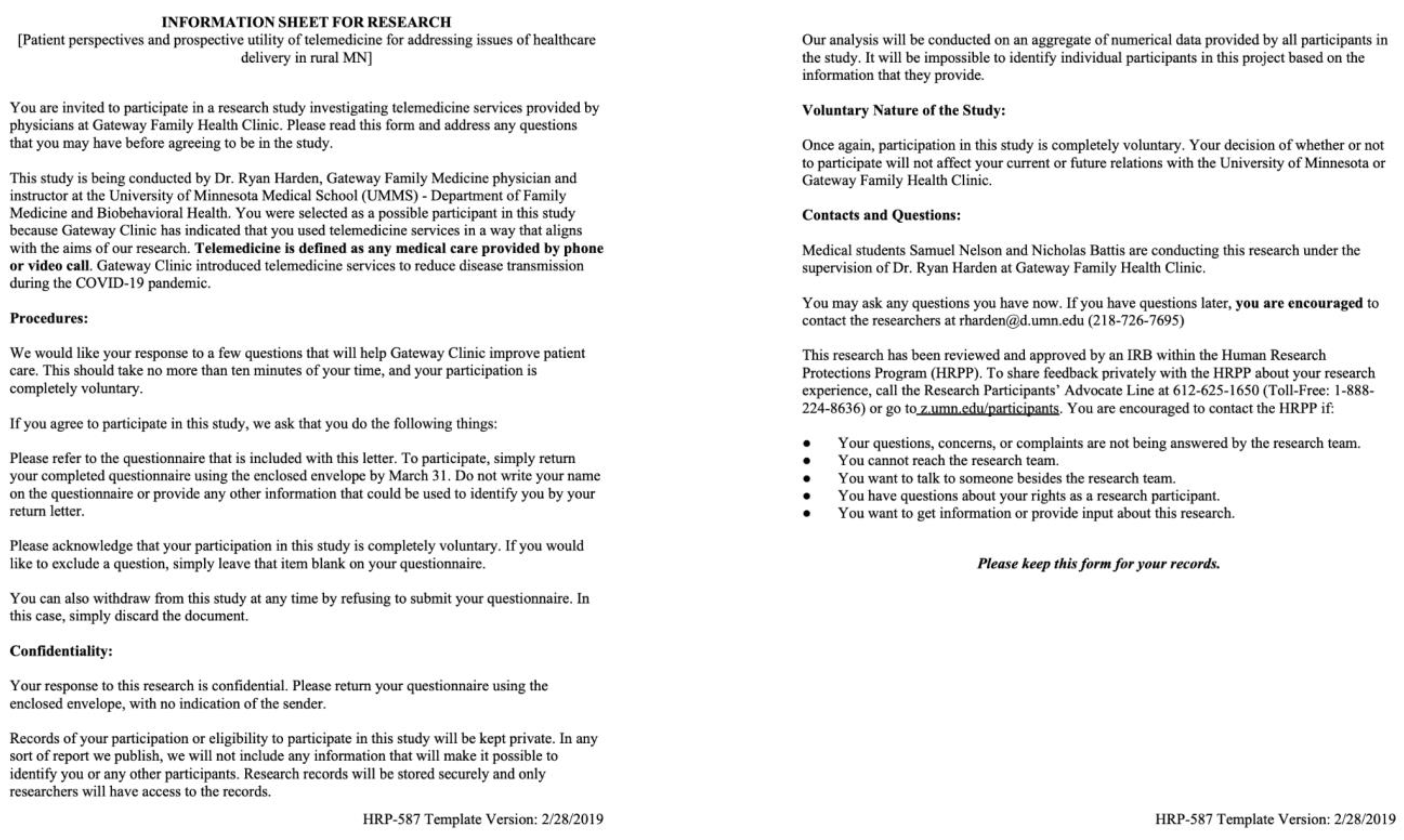

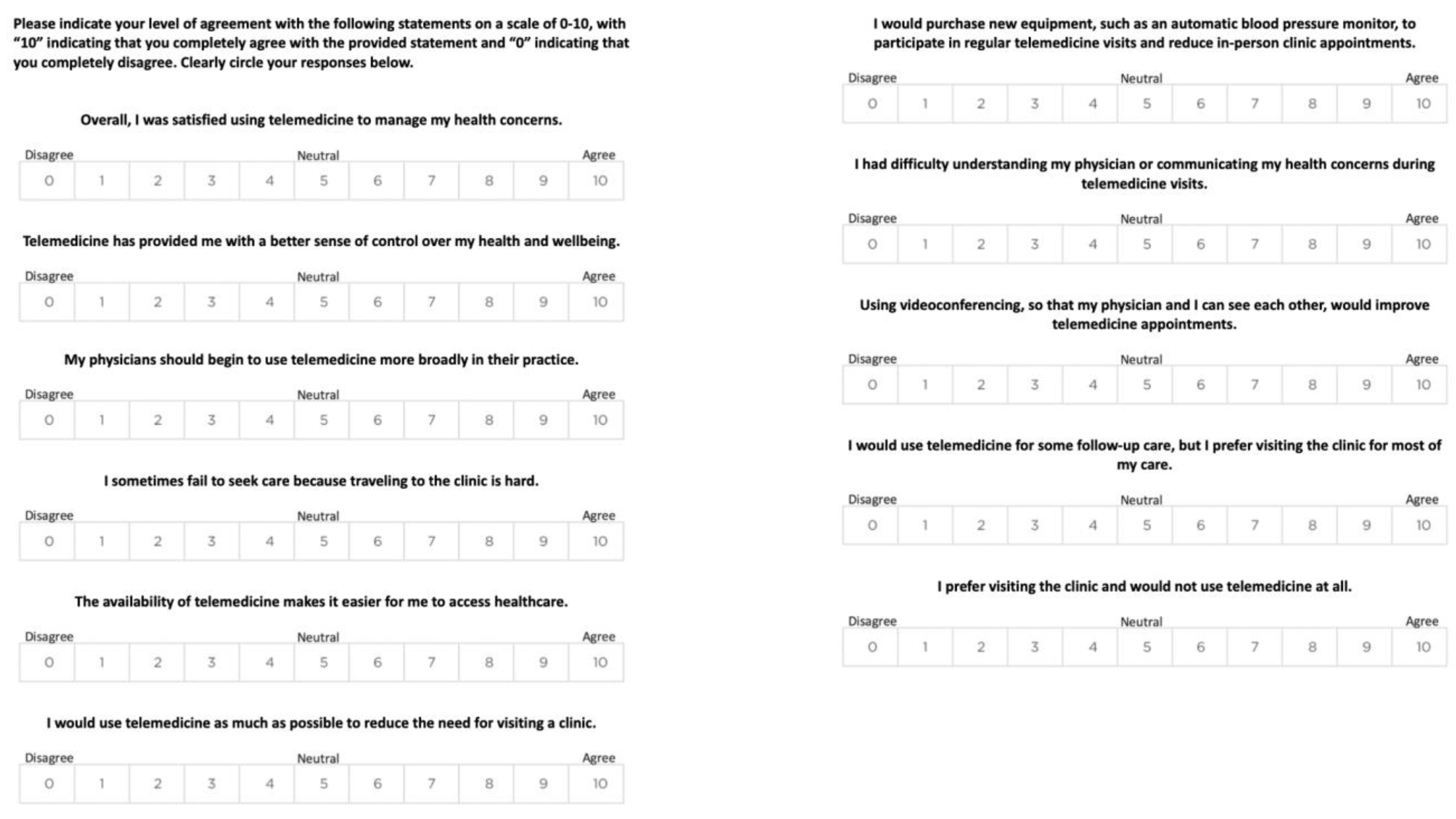

Data Collection: Each participant was mailed a research packet containing a study information sheet (

Figure 1), a survey (

Figure 2), and a return envelope with pre-addressed postage for the University of Minnesota Medical School (UMMS) - Duluth Campus. Return envelopes were unpacked in a designated office for the researchers at the UMMS - Duluth Campus. Data values from the survey forms were entered into an Excel spreadsheet stored on the University Box Secure Storage system. All policies and procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Minnesota IRB and host site administration.

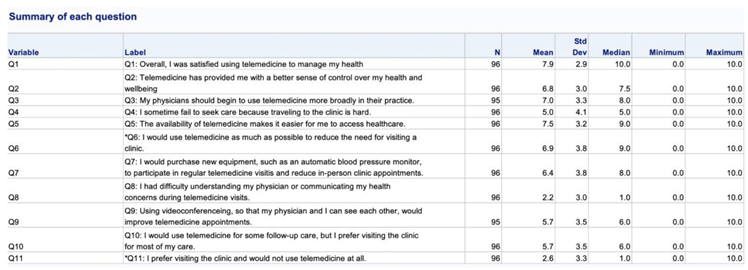

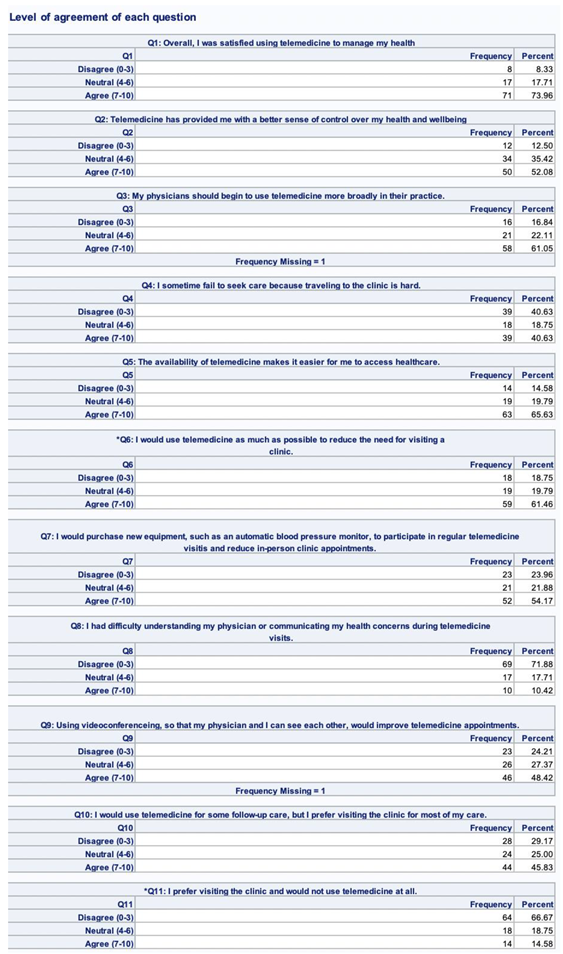

Statistical Methods: This study employed descriptive statistics to assess respondents’ level of agreement with survey items. The survey consisted of 11 items, each with response options on a 0-to-10 scale where “10” indicated complete agreement with a proposed item, and “0” indicated complete disagreement. The items were generated from a combination of literature review and clinical experience. These were grouped into descriptive categories: In support of telemedicine; against telemedicine; tangent/neutral. Response values were first grouped as follows: 0-3 (disagree); 4-6 (neutral); 7-10 (agree). Otherwise: 0 (strongest disagreement); 1-3 (disagree); 4-6 (neutral); 7-9 (agree); 10 (strongest agreement).

Bias: Acquiescence bias was adjusted for by inclusion of both positive and negative perception questions about telemedicine. Nonresponse bias was adjusted for by utilizing a mailing survey to capture attitudes of patients without access to computing technology. Self-selection bias was present and unadjusted for due to the voluntary nature of the study.

Results:

Of the 766 individuals provided with a research packet, 111 (14.5%) returned the packet. Responses were assessed for completeness and validity using the following criteria: More than 20% of survey items were left blank; a straight-lining pattern of responses; and contradictory items #6 and #11 had non-neutral scores that were similar (within 3 points). Fifteen surveys met these criteria and were excluded from the final analysis. For all of the others included in the analysis, descriptive summaries were generated (counts and percentages) for each item.

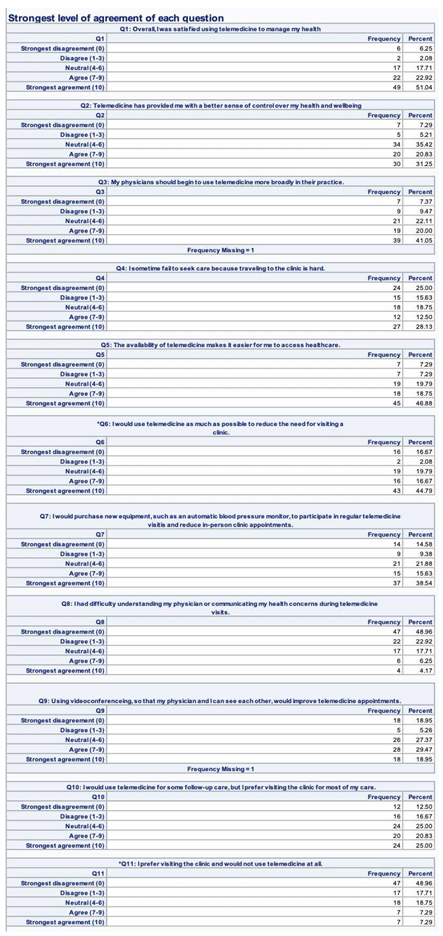

We observed a trend that the respondents agreed with the positive items and disagreed with the negative items (

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3). Specifically, a majority of the respondents indicated that they were satisfied with using telemedicine (73.96%); that they gained an additional sense of control over their health condition due to the availability of telemedicine (52.08%); that they would support the use of telemedicine in the future (61.05%); that telemedicine increased access to care (65.63%); telemedicine was preferred over the clinic (61.46%), and that they would purchase new equipment to increase the utility of telemedicine services (54.17%). 51.04% of the respondents indicated a 10/10 level of satisfaction with telemedicine services. 48.96% indicated the strongest level of disagreement related to difficulty using telemedicine or a preference for in-person clinical appointments.

Discussion:

Despite long-standing support for telemedicine and slow, but steady, adoption, its role in the broader healthcare ecosystem is largely speculative [

1,

3,

8]. Telemedicine has been touted as a viable solution for addressing health disparities in rural populations. This is largely through its presumed role in leveling barriers to healthcare access and equity [

10]. Current research has also demonstrated that general perceptions of telemedicine are favorable to the continued expansion of services [

23]. If this is the case, then more work needs to be done to understand exactly what services are valued by the patient population, as well as how to implement innovative telemedicine practices into highly effective healthcare systems.

Our study is aimed at elucidating some of the major factors affecting patients’ perceptions of telemedicine in a rural primary care setting in Minnesota. It provides useful context for buyers, regulators, researchers, and changemakers concerned with health IT. Our primary aim was to supply foundational information to encourage additional research, development, and strategic changes in practice.

Our results show that patients do appreciate telemedicine and plan to use these services in the future. They also suggest that patients would choose telemedicine over the clinic and that audio-only telemedicine was sufficient for their needs. In our rural patient population, this trend likely reflects the ability of telemedicine to address barriers of travel time, travel costs, and scheduling difficulties. Additional studies specifically addressing patient barriers within each of these categories would be beneficial to further clarify what features will retain patients in telehealth for future visits. Given the option, the patients in our study would purchase additional equipment to avoid traveling to the clinic for care. For some, this may reflect a very real barrier to accessing care at all, versus the convenience of fitting healthcare into their schedules. Regardless, our data suggest that telemedicine makes it easier to access healthcare and provides many patients with an improved sense of control over their health.

These results are interesting in the current context because nearly all community health systems should be equipped to implement audio-only telemedicine services for their patients. If regulatory changes continue to support reimbursement of these services, then many clinics may experience an increase in service volume. As patients take advantage of their enhanced access to healthcare, regular assistance with health and wellness concerns could become more central to their lives.

Because this was a foundational study, there are several limitations and suggestions for future work. The rural setting and unique circumstances surrounding COVID-19 could certainly limit the generalizability of our findings. We also chose to study audio-only telemedicine services and the host site had limited experience with this modality of care. While these elements of the study may pose limitations to our work, they also provide an interesting perspective on the state of telemedicine in Minnesota. The fact that our sample has limited exposure to changes in health IT may provide an unbiased survey of the changes taking place. However, as it is inherent to all survey research, response bias affecting the results may diminish the proposed unique advantages of the niche population and reflect more positive or negative perceptions than appropriate. Knowing the demographic characteristics of individual participants could somewhat neutralize the effects of response bias and provide other useful insights. However, we were unable to gain approval for this data from the IRB within our project deadlines.

Future studies may replicate our timeline and design but employ a broader range of communities and personal data to provide more generalizable results. The questionnaire could also be expanded to address different technologies and programs. Outside of regular quality improvement initiatives locally, it is probably wise for researchers to address the evolution of health IT and widespread reactions to inform continued innovation. One insight that would be interesting to know is what health conditions or appointments are considered the most valuable for patients, and what features of those technologies are most desired. Also, as the health IT landscape expands, questions need to be answered regarding the roles that local providers and health systems should play in this inevitable decentralization of care.

The traditional model for healthcare, volume-based care delivered through siloed specialty practices, is less than ideal for managing many health concerns. The healthcare industry is also facing strain from workforce shortages and the growing prevalence of multimorbidity. Patients are often forced to forego healthcare due to issues of access, equity, cost, convenience, and overall satisfaction with available services, which contributes to insidious trends of declining population health and rising costs of care as patients eventually pursue treatment for more debilitating syndromes.

In the population addressed by this study, mental health, obesity, and substance abuse are priority health concerns with a lack of social connection cited as a principal contributor [

21]. Regularly scheduled phone calls with a local healthcare provider aimed at cognitive behavioral interventions could be a useful strategy for confronting these issues in the near term. Eventually, this may be outsourced to commercial health and wellness platforms that use different modalities of telemedicine, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality. Otherwise, tertiary care centers that create their own virtual medicine programs to broaden access to specialty care. Local providers and larger health systems alike may choose to partner with virtual networks to sponsor events and services analogous to the community marathons and health fairs of today. Regardless of the degree of technological enhancement, the shift to remote care encourages a strategic pivot from reactive to proactive healthcare. Patients will have more immediate and regular contact with their local healthcare providers so that critical issues are recognized and addressed in a timely manner.

Conclusion:

This study provided important insight into the state of telemedicine in rural Minnesota, but much work remains to be done in the areas of telemedicine innovation and policy. The data in this study trends to an overall positive attitude toward telemedicine, with patients generally agreeing with positive statements and disagreeing with negative statements, however, agreement was far from 100% indicating a continued need for improvement and evaluation of telemedicine in practice. Some limitations of this study include the relatively small and niche sample, the historic circumstances of COVID-19, and inherent self-selection bias. A replicate study could employ several communities throughout the state or region to provide more generalizable results. The questionnaire could also be expanded to address different modalities of telemedicine, remote patient monitoring technology, and other virtual therapeutics. If possible, future work should include the demographic characteristics of individual participants.

The circumstances surrounding COVID-19 were certainly unique and bound to influence strategies for healthcare. As the landscape continues to evolve at a rapid pace, this study should provide a great context for changemakers and end users making strategic decisions about the future of remote healthcare delivery.

Conflicts of Interest

Samuel Nelson: Dose Health LLC; MobileMSK LLC.

References

- Angaran DM. Telemedicine and telepharmacy: current status and future implications. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999 Jul 15;56(14):1405-26. [CrossRef]

- Bashshur RL, Howell JD, Krupinski EA, Harms KM, Bashshur N, Doarn CR. The Empirical Foundations of Telemedicine Interventions in Primary Care. Telemed J E Health. 2016 May;22(5):342-75. [CrossRef]

- Bashshur, Rashid, Patricia A. Armstrong, and Zakhour I. Youssef. “Telemedicine; Explorations in the Use of Telecommunications in Health Care.” Springfield, Ill: C. C. Thomas, 1975.

- Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: A systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(1):4-12.

- Polinski JM, Barker T, Gagliano N, Sussman A, Brennan TA, Shrank WH. Patients' Satisfaction with and Preference for Telehealth Visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2016 Mar;31(3):269-75. [CrossRef]

- Bhavnani SP, Narula J, Sengupta PP. Mobile technology and the digitization of healthcare. Eur Heart J. 2016 May 7;37(18):1428-38. [CrossRef]

- A brief history of the internet. University System of Georgia Online Library Learning Center [internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 4]. Available from: https://www.usg.edu/galileo/skills/unit07/internet07_02.phtml#:~:text=January%201%2C%201983%20is%20considered,Protocol%20(TCP%2FIP).

- Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of Telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):154-161.

- History of Telehealth. National Consortium of Telehealth Resource Center [internet]. 2021 Nov 30;. [cited 2022 Nov 4]. Available from: https://telehealthresourcecenter.org/resources/fact-sheets/history-of-telehealth/.

- Telemedicine Utilization Report 2020. Minnesota Department of Human Services [internet]. 2020 Dec 16; [cited 2022 Jul 7]. Available from: https://mn.gov/dhs/assets/telemedicine-utilization-report-2020_tcm1053-458660.pdf.

- Almathami HKY, Win KT, Vlahu-Gjorgievska E. Barriers and Facilitators That Influence Telemedicine-Based, Real-Time, Online Consultation at Patients' Homes: Systematic Literature Review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(2):e16407. Published 2020 Feb 20.

- State Telehealth Laws and Reimbursement Policies. The National Telehealth Policy Resource Center [internet]. 2022. [cited 2022 Jul 7]. Available from: https://www.cchpca.org/2022/05/Spring2022_Infographicfinal.pdf.

- Licensing and Credentialing of Telehealth Programs. Rural Health Information Hub [internet]. [cited 2022 Oct 28]. Available from: https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/telehealth/4/licensing-and-credentialing.

- 2021 Year-End Digital Health Funding: Seismic Shifts Beneath the Surface. Rock Health [internet]. 2022 Jan 10; [cited 2022 Jul 10]. Available from: https://rockhealth.com/insights/2021-year-end-digital-health-funding-seismic-shifts-beneath-the-surface/.

- H.R.1 - American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. 111th United States Congress [internet]. 2009 Jan 26. [cited 2022 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/house-bill/1/text.

- FY 2016 Rural Health Grant Awards. Health Resources & Services Administration [internet]. 2017 Jun 19. [cited 2022 Nov 4]. Available from: https://www.hrsa.gov/about/news/2016-tables/rural-health/index.html.

- 2021 Survey of America’s Physicians COVID-19 Impact Edition: A Year Later. The Physicians Foundation [internet]. 2021. [cited 2022 Jul 11]. Available from: https://physiciansfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/2021-Survey-Of-Americas-Physicians-Covid-19-Impact-Edition-A-Year-Later.pdf.

- From Virtual Care to Hybrid Care: COVID-19 and the Future of Telehealth. Amwell Physician and Consumer Survey [internet]. 2022 Jun. [cited 2022 Jul 8]. Available from: https://static.americanwell.com/app/uploads/2020/09/Amwell-2020-Physician-and-Consumer-Survey.pdf.

- Center for Devices and Radiological Health. U.S. Food and Drug Administration [internet]. [cited 2022 Jul 7]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center-excellence.

- Mair F, Whitten P. Systematic review of studies of patient satisfaction with telemedicine. BMJ. 2000;320(7248):1517-1520. [CrossRef]

- Community Health Assessment. Pine County, Minnesota [internet]. 2018 Apr 15. [cited 2022 Nov 4]. Available from: https://www.co.pine.mn.us/departments/health_and_human_services/public_health/community_health_assessment.php.

- Sandstone, MN. Data USA [internet]. [cited 2022 Jul 7]. Available from: https://datausa.io/profile/geo/sandstone-mn#:~:text=The%205%20largest%20ethnic%20groups,%2DHispanic)%20(3.22%25.

- Hyder MA, Razzak J. Telemedicine in the United States: An Introduction for Students and Residents. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(11):e20839. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).