Submitted:

03 June 2023

Posted:

05 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Aerobic exercise training improves systolic and diastolic cardiac function, and signs of heart failure in animals with heart failure resulting from aortic stenosis

2.2. Aortic stenosis impairs the rate of tension development and resting tension, whereas exercise is effective in restoring resting tension in exercised cardiac animals

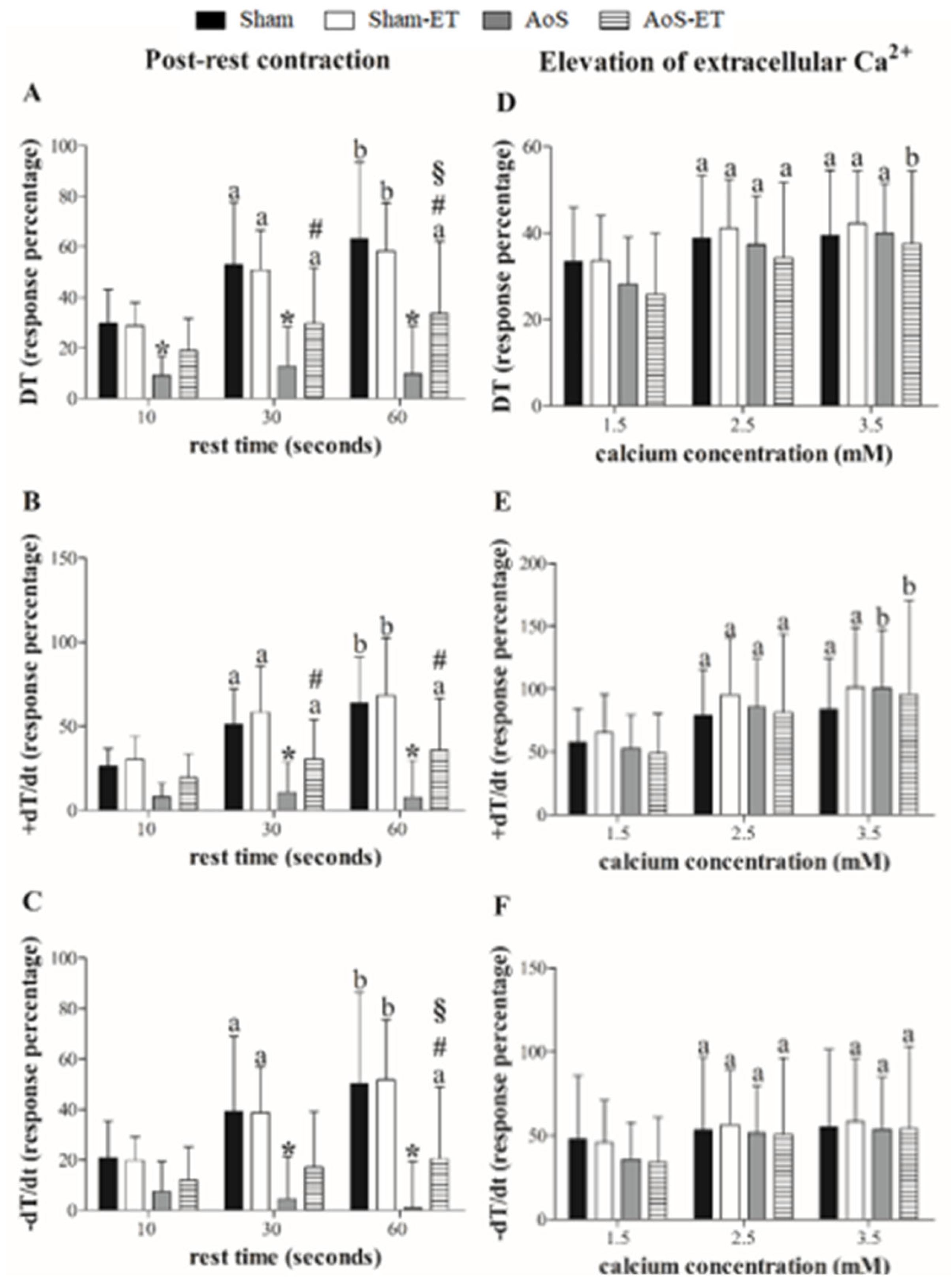

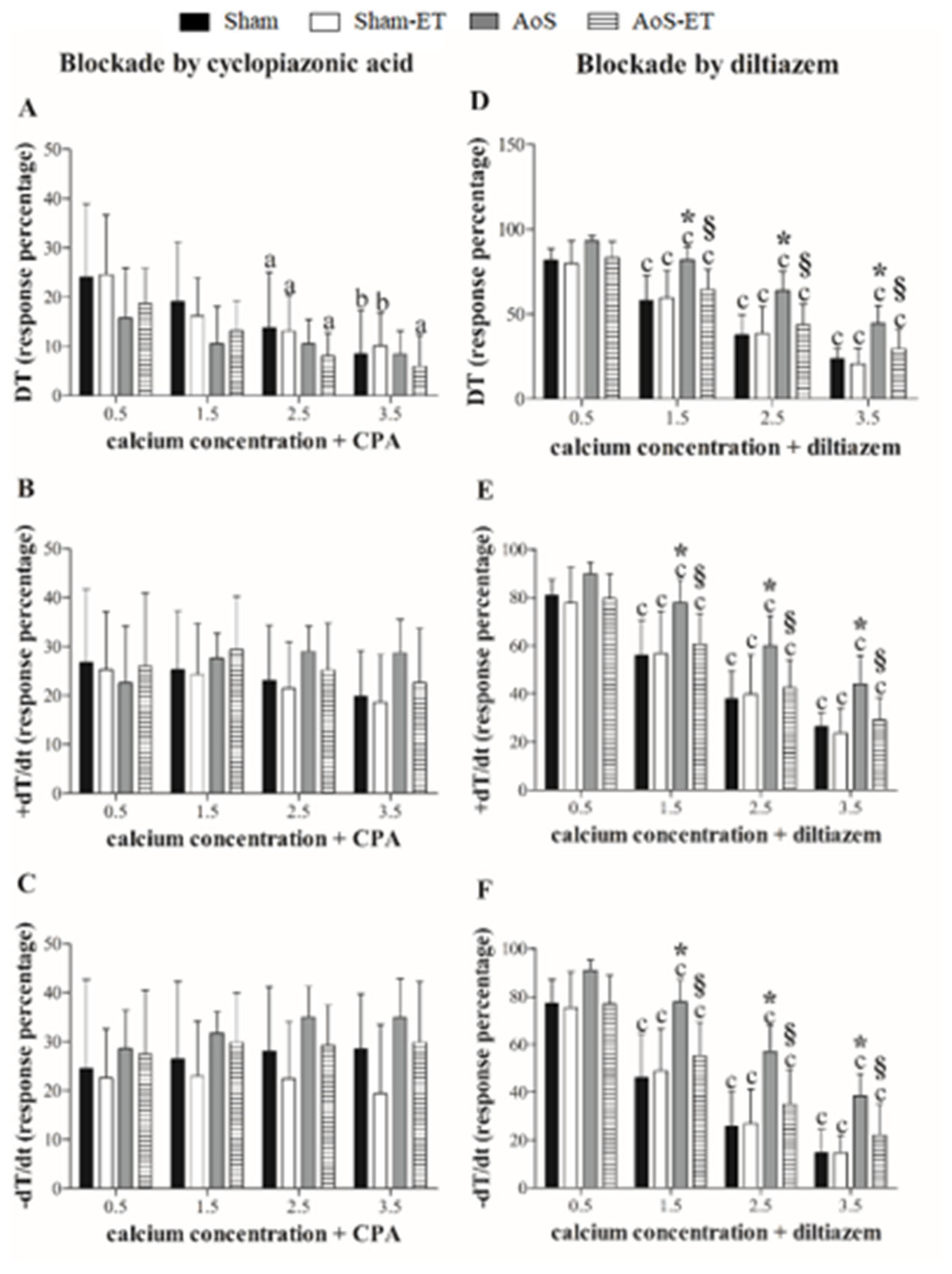

2.3. Aortic stenosis deteriorates SERCA2a function, whereas AET attenuates the loss of SERCA2a functionality in exercised cardiac animals

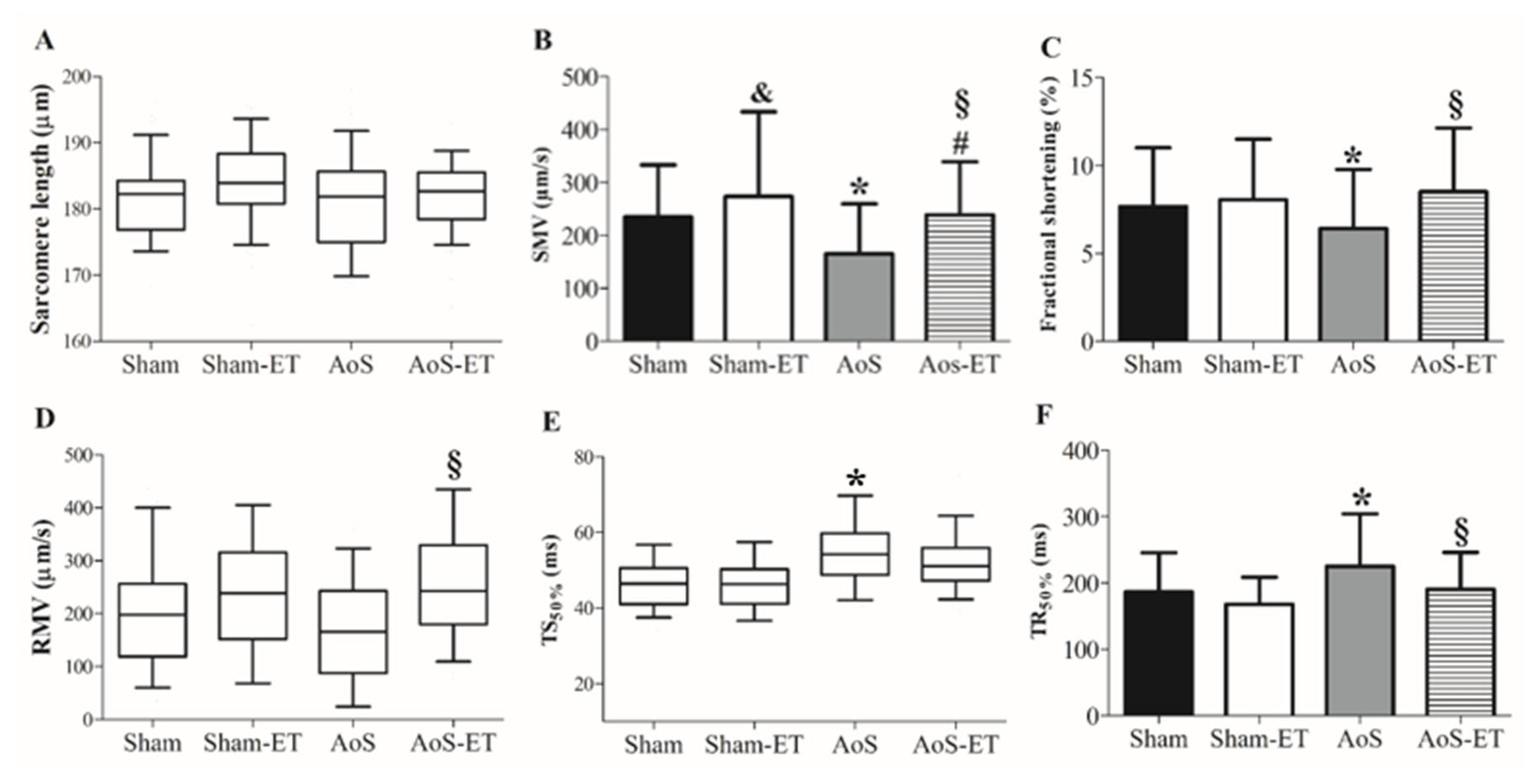

2.4. At a cellular level, AET improved the shortening and relaxation function exercised cardiac animals

2.5. In the isolated cardiomyocyte experiment, AET improves the responsiveness of myofilaments to calcium

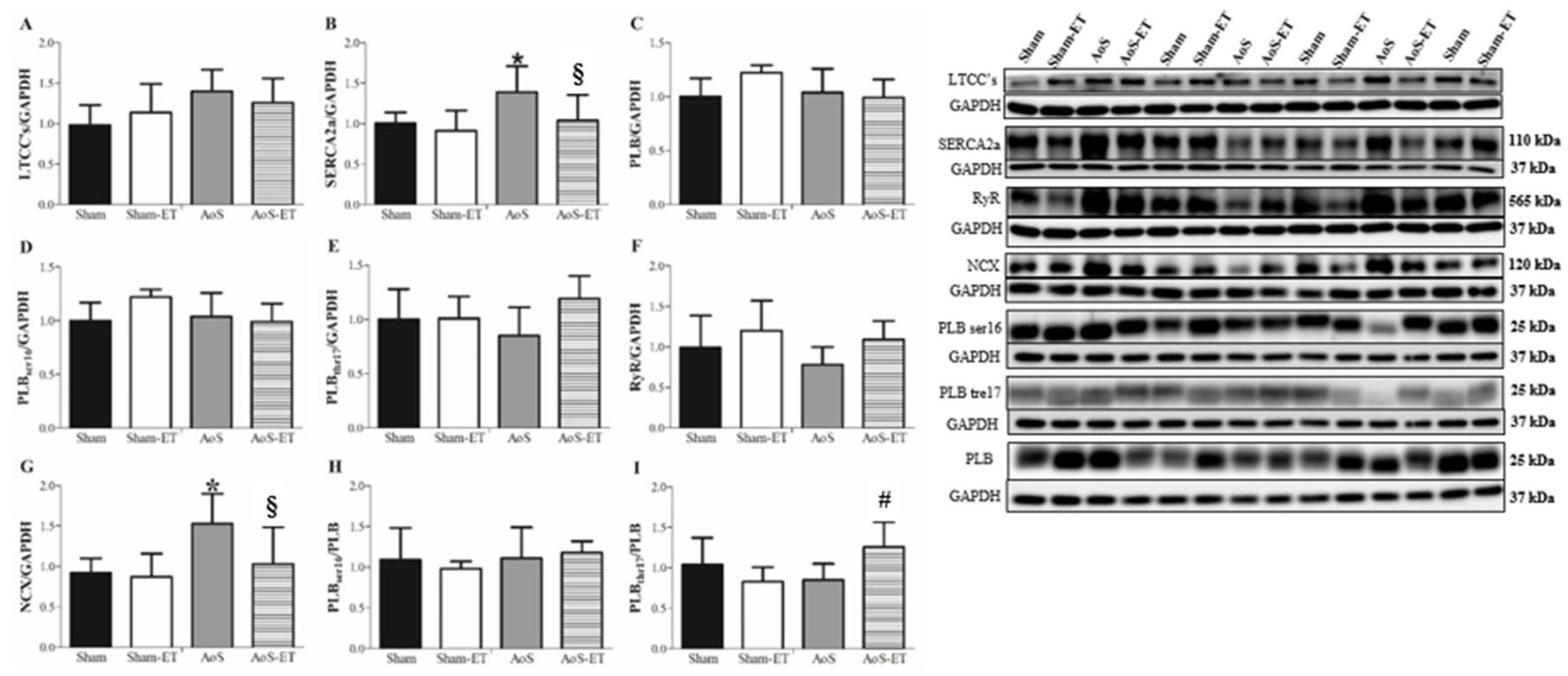

2.6. Aortic stenosis causes changes in calcium handling proteins, which are restored in animals that participated in the AET

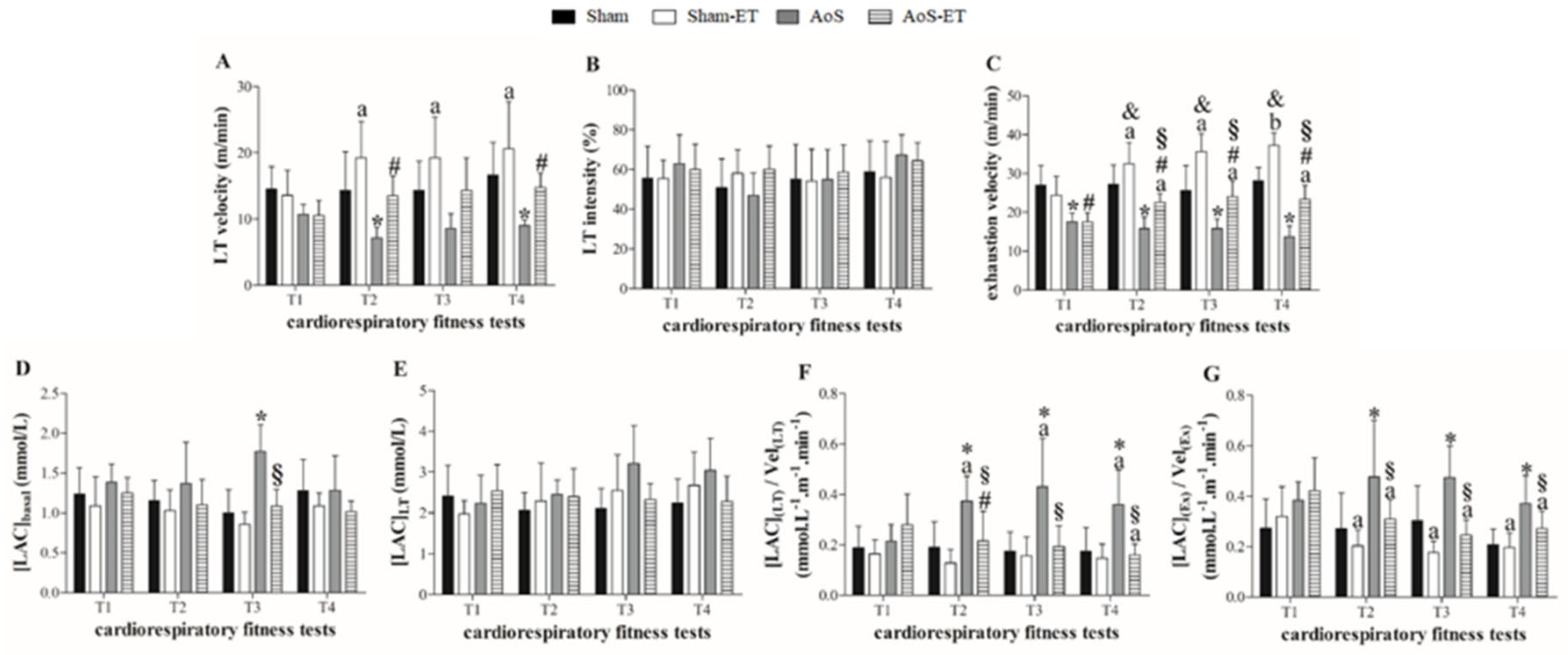

2.7. AET improves the functional capacity and metabolic profile of exercise in cardiac animals exercised

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study design

- The first experimental line evaluated cardiac function by echocardiogram and isolated papillary muscle, and the expression of Ca2+ handling regulatory protein by Western Blot. SERCA2a and L-type calcium channels activity were analyzed during post-rest contraction and calcium elevation (Sham, n = 22; Sham-ET, n = 20; AoS, n = 16; AoS-ET, n = 16), respectively, and by the cumulative administration of extracellular Ca2+ in the presence of SERCA2a or L-type calcium channels specific blockers in the isolated papillary muscle assay. In addition, in order to assess functional capacity and prescribe aerobic exercise training, the animals were submitted to cardiorespiratory fitness tests at weeks 18, 22, 25 and 28 of the experimental protocol.

- the second experimental line evaluated cardiac function by echocardiogram and isolated cardiomyocyte assay, which measured mechanical function and Ca2+ handling (Sham, n = 6; Sham-ET, n = 6; AoS, n = 6; AoS-ET, n = 6). In these animals, the week 28 cardiorespiratory fitness tests were not performed due to technical issues.

4.2. Animals

4.3. Aortic stenosis surgery

4.4. Cardiorespiratory fitness test (CFT)

4.5. Aerobic exercise training (AET)

4.6. Cardiac function

4.6.1. Echocardiogram

4.6.2. Isolated papillary muscle assay

4.6.3. Isolated cardiomyocyte assay

- Cardiomyocyte contractility

- Intracellular Ca2+ measurements

4.7. Expression of calcium handling protein

4.8. Statistical analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blair, S.N. Exercício, Envelhecimento Bem-Sucedido e Prevenção das Doenças. In: Fisiologia do Exercício: Nutrição, Energia e Desempenho Humano, 7th edition. Guanabara Koogan: Barueri, São Paulo, 2011, pp. 854–957.

- Egan, B.; Zierath, J.R. Exercise metabolism and the molecular regulation of skeletal muscle adaptation. Cell. Metab. 2013, 17, 162–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Durstine, J.L. Physical activity, exercise, and chronic disease: A brief review. SMHS. 2019, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Available online: www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Warburton, D.E.; Nicol, C.W.; Bredin, S.S. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ. 2006, 174, 801–9. 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, F.W.; Roberts, C.K.; Laye, M.J. Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Compr. Physiol. 2012, 2, 1143–211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leskinen, T.; Stenholm, S.; Aalto, V.; Head, J.; Kivimäki, M.; Vahtera, J. Physical activity level as a predictor of healthy and chronic disease-free life expectancy between ages 50 and 75. Age Ageing. 2018, 47, 423–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanesco, A.; Antunes, E. Effects of exercise training on the cardiovascular system: pharmacological approaches. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 114, 307–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J. Exercise and Cardiovascular Health. Circulation. 2003, 107, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Saltin, B.K. Exercise as medicine - evidence for prescribing exercise as 95 therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 2015, 25, 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, G.A.F.; de Souza, S.L.B.; da Silva, V.L.S.; Gato, M.; de Campos, D.H.S.; Sant’Ana, P.G.; et al. Cardioprotection Generated by Aerobic Exercise Training is Not Related to the Proliferation of Cardiomyocytes and Angiotensin-(1-7) Levels in the Hearts of Rats with Supravalvar Aortic Stenosis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 54, 719–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, S.L.B.; Mota, G.A.F.; da Silva, V.L.S.; Sant’Ana, P.G.; Vileigas, D.F.; de Campos, D.H.S.; et al. Adjustments in β-Adrenergic Signaling Contribute to the Amelioration of Cardiac Dysfunction by Exercise Training in Supravalvular Aortic Stenosis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 54, 665–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky, L.A.; Arena, R.; Ellingsen, O.; Harber, M.P.; Myers, J.; Ozemek, C.; et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and cardiovascular disease – The past, present and future. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2019, 62, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiemstra, J.A.; Veteto, A.B.; Lambert, M.D.; Olver, T.D.; Ferguson, B.S.; McDonald, K.S.; et al. Chronic low-intensity exercise attenuates cardiomyocyte contractile dysfunction and impaired adrenergic responsiveness in aortic-banded mini-swine. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 2018, 124, 1034–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, A.; Rolim, N.P.L.; Oliveira, R.S.F.; Rosa, K.T.; Mattos, K.C.; Casarini, D.E.; et al. Exercise training delays cardiac dysfunction and prevents calcium handling abnormalities in sympathetic hyperactivity-induced heart failure mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 104, 103–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardo, B.C.; Ooi, J.Y.Y.; Weeks, K.L.; Patterson, N.L.; McMullen, L.R. Understanding key 96 mechanisms of exercise-induced cardiac protection to mitigate disease: current knowlegde and emerging concepts. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 419–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, S.F.S.; Barauna, V.G.; Neves, V.J.; Fernandes, T.; Lara, L.S.; Mazzotti, D.R.; et al. Exercise training restores the cardiac microRNA-1 and -214 levels regulating Ca2+ handling after myocardial infarction. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2015, 15, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garciarena, C.D.; Pinilla, A.O.; Nolly, M.B.; Laguens, R.P.; Escudero, E.M.; Cingolani, H.E.; et al. Endurance training in the spontaneously hypertensive rat: conversion of pathological into physiological cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2009, 53, 708–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Mei, D.F.; Gu, A.G.; Wang, S.; Lentzner, B.; Gutstein, D.E.; et al. Exercise training normalizes altered calcium-handling proteins during development of heart failure. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 92, 1524–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høydal, M.A.; Stølen, T.O.; Kettlewell, S.; Maier, L.S.; Brown, J.H.; Sowa, T.; et al. Exercise training reverses myocardial dysfunction induced by CaMKII overexpression by restoring Ca2+ homeostasis. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 121, 212–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro-Júnior, M.A.; Quintão-Júnior, J.F.; Drummond, L.R.; Lavorato, V.N.; Drummond, F.R.; Amadeu, M.A.; et al. Effect of exercise training on Ca+2 release units of left ventricular myocytes of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemi, O.J.; MacQuaide, N.; Hoydal, M.A.; Ellingsen, O.; Smith, G.L.; Wisløff, U. Exercise training corrects control of spontaneous calcium waves in hearts from myocardial infarction heart failure rats. J. Cell. Physiol. 2012, 227, 20–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bito, V.; de Waard, M.C.; Biesmans, L.; Lenaerts, I.; Ozdemir, S.; van Deel, E.; et al. Early exercise training after myocardial infarction prevents contractile but not electrical remodeling or hypertrophy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 86, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolim, N.P.; Medeiros, A.; Rosa, K.T.; Mattos, K.C.; Irigoyen, M.C.; Krieger, E.M.; et al. Exercise training improves the net balance of cardiac Ca+2 handling protein expression in heart failure. Physiol. Genomics. 2007, 29, 246–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisløff, U.; Loennechen, J.P.; Currie, S.; Smith, G.L.; Ellingsen, O. Aerobic exercise reduces cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and increases contractility, Ca+2 sensitivity and SERCA2a in rat after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2002, 54, 162–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Deel, E.D.; de Boer, M.; Kuster, D.W.; Boontje, N.M.; Holemans, P.; Sipido, K.R.; et al. Exercise training does not improve cardiac function in compensated or decompensated left ventricular hypertrophy induced by aortic stenosis. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2011, 50, 1017–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, V.L.; de Souza, S.L.B.; Mota, G.A.F.; de Campos, D.H.S.; Melo, A.B.; Vileigas, D.F.; et al. The Dysfunctional Scenario of the Major Components Responsible for Myocardial Calcium Balance in Heart Failure Induced by Aortic Stenosis. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2022, 118, 464–75. [Google Scholar]

- de Tomasi, L.C.; Campos, D.H.S.; Sant’Ana, P.G.; Okoshi, K.; Padovani, C.R.; Murata, G.M.; et al. Pathological hypertrophy and cardiac dysfunction are linked to aberrant endogenous unsaturated fatty acid metabolism. PLoS One. 2018, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Pacagnelli, F.L.; Okoshi, K.; Campos, D.H.S.; Souza, R.W.A.; Padovani, C.R.; Carvalho, R.F.; et al. Physical training attenuates cardiac remodeling in rats with supra-aortic stenosis. Exp. Clin. Cardiol. 2014, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, M.J.; Martinez, P.F.; Campos, D.H.; Pagan, L.U.; Bonomo, C.; Lima, A.R.; et al. Beneficial Effects of Physical Exercise on Functional Capacity and Skeletal Muscle Oxidative Stress in Rats with Aortic Stenosis-Induced Heart Failure. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.W.A.; Fernandez, G.J.; Cunha, J.P.Q.; Piedade, W.P.; Soares, L.C.; Souza, P.A.T.; et al. Regulation of cardiac microRNAs induced by aerobic exercise training during heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 2015, 309, H1629–H1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, P.A.T.; de Souza, R.W.A.; Soares, L.C.; Piedade, W.P.; Campos, D.H.S.; Carvalho, R.F.; et al. Aerobic training attenuates nicotinic acethylcholine receptor changes in the diaphragm muscle during heart failure. Histol. Histopathol. 2015, 30, 801–11. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, R.W.A.; Piedade, W.P.; Soares, L.C.; Souza, P.A.T.; Aguiar, A.F.; Vechetti-Júnior, I.J.; et al. Aerobic exercise training prevents heart failure-induced skeletal muscle atrophy by anti-catabolic, but not anabolic actions. PloS one. 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, D.L. Pathophysiology of Heart Failure. In: Braunwald’s Heart Disease - A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine, 11th edition. Elsevier. 2012. pp. 487–504.

- Maillet, M.; van Berlo, J.H.; Molkentin, J.D. Molecular basis of physiological heart growth: fundamental concepts and new players. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013, 14, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, M.; Sadoshima, J. Mechanisms of physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirone, L.; Forte, M.; Palmerio, S.; Yee, D.; Nocella, C.; Angelini, F.; et al. A Review of the Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Development and Progression of Cardiac Remodeling. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diwan, A.; Hill, J.A.; Force, T.L. Molecular Basis for Heart Failure. In: Heart Failure: A Companion to Braunwald’s Heart Disease, 3th edition. Elsevier. 2016. pp. 1-27.

- Katz, A.M. Heart Failure. In: Physiology of the Heart, 5th edition. Wolters Kluwer. 2011. p. 510-47.

- Plitt, G.D.; Spring, J.T.; Moulton, M.J.; Agrawal, D.K. Mechanisms, diagnosis, and treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and diastolic dysfunction. Expert. Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2018, 16, 579–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Heerebeek, L.; Paulus, W.J. Alterations in Ventricular Function: Diastolic Heart Failure. In: Heart Failure: A Companion to Braunwald’s Heart Disease, 3th edition. Elsevier. 2016. p. 156- 76.

- Gu, J.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Wang, X.; Xue, J.; et al. The Molecular Mechanism of Diastolic Heart Failure. Integr. Med. Int. 2015, 143–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souders, C.A.; Borg, T.K.; Banerjee, I.; Baudino, T.A. Pressure overload induces early morphological changes in the heart. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 181, 1226–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, C.F.S.M.P.; Campos, D.H.S.; Freire, P.P.; Deus, A.F.; Okoshi, K.; Padovani, C.R.; et al. Importance of SERCA2a on early isolated diastolic dysfunction induced by supravalvular aortic stenosis in rats. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2017, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.H.; Uriel, N.; Burkhoff, D. Reverse remodeling and myocardial recovery in heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikman-Coffelt, J.; Parmley, W.W.; Mason, D.T. The Cardiac Hypertrophy Process. Analyses of Factors Determining Pathological Vs. Physiological Development. Circ. Res. 1979, 45, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuer, J.; Malhotra, A.; Hirsch, C.; Capasso, J. Physiologic Cardiac Hypertrophy Corrects Contratile Protein Abnormalities Associated with Pathologic Hypertrophy in Rats. J. Clin. Invest. 1982, 70, 1300–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.K. Cardiovascular benefits of exercise. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2012, 5, 541–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gielen, S.; Schuler, G.; Adams, V. Cardiovascular effects of exercise training: molecular mechanisms. Circulation. 2010, 122, 1221–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito Vieira, W.H.; Halsberghe, M.J.; Schwantes, M.L.; Perez, S.E.; Baldissera, V.; Prestes, J.; et al. Increased lactate threshold after five weeks of treadmill aerobic training in rats. Braz. J. Biol. 2014, 74, 444–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A. Anaerobic threshold: its concept and role in endurance sport. Malays J. Med. Sci. 2004, 11, 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- van Deel, E.D.; Octavia, Y.; Waard, M.C.; Boer, M.; Duncker, D.J. Exercise training has contrasting effects in myocardial infarction and pressure overload due to divergent endothelial nitric oxide synthase regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemi, O.J.; Ceci, M.; Condorelli, G.; Smith, G.L.; Wisløff, U. Myocardial sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase function is increased by aerobic interval training. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 2008, 15, 145–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisløff, U.; Loennechen, J.P.; Falck, G.; Beisvag, V.; Currie, S.; Smith, G.; et al. Increased contractility and calcium sensitivity in cardiac myocytes isolated from endurance trained rats. Cardiovasc Res. 2001, 50, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemi, O.J.; Haram, P.M.; Loennechen, J.P.; Osnes, J.B.; Skomedal, T.; Wisløff, U.; et al. Moderate vs. high exercise intensity: Differential effects on aerobic fitness, cardiomyocyte contractility, and endothelial function. Cardiovasc Res 2005, 67, 161–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán, M.; Saborido, A.; Megías, A. Ca+2 regulatory systems in rat myocardium are altered by 24 weeks treadmill training. Pflugers Arch. 2003, 446, 161–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, A.M. Excitation-Contraction Coupling: Extracellular and Intracellular Calcium Cycles. In: Physiology of the Heart, 5th edition. Wolters Kluwer. 2011. p. 143-76.

- Wang, K.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Q.; Long, J.; Liu, J.; Ding, J. Mitochondria regulate cardiac contraction through ATP-dependent and independent mechanisms. Free Radic. Res. 2018, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, J.C.; Queliconi, B.B.; Bozi, L.H.M.; Bechara, L.R.G.; Dourado, P.M. M, Andres AM. Exercise reestablishes autophagic flux and mitochondrial quality control in heart failure. Autophagy. 2017, 13, 1304–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva Jr, S.D.; Jara, Z.P.; Peres, R.; Lima, L.S.; Scavone, C.; Montezano, A.C. Temporal changes in cardiac oxidative stress, inflammation and remodeling induced by exercise in hypertension: Role for local angiotensin II reduction. PLoS One. 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokelke, E.A.; Palmer, B.M.; Cheung, J.Y.; Moore, R.L. Endurance training does not affect intrinsic calcium current characteristics in rat myocardium. Am. J. Physiol. – Heart Circ. Physiol. 1997, 42, H1193–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, J.; Saborido, A.; Morán, M.; Megías, A. Chronic and acute exercise do not alter Ca+2 regulatory systems and ectonucleotidase activities in rat heart. J. Appl. Physiol. 1999, 87, 152–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Zheng, J.; Shu, M.; Zhu, S.; Jie, D. Swimming training can a V ect intrinsic calcium current characteristics in rat myocardium. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 104, 549–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bregagnollo, E.A.; Zornoff, L.A.M.; Okoshi, K.; Sugizaki, M.; Mestrinel, M.A.; Padovani, C.R.; et al. Myocardial contractile dysfunction contributes to the development of heart failure in rats with aortic stenosis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2007, 117, 109–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregagnollo, E.A.; Mestrinel, M.A.; Okoshi, K.; Carvalho, F.C.; Bregagnollo, I.F.; Padovani, C.R.; et al. Relative role of left ventricular geometric remodeling and of morphological and functional myocardial remodeling in the transition from compensated hypertrophy to heart failure in rats with supravalvar aortic stenosis. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2007, 88, 225–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, B.; Figueroa, D.M.; Mostarda, C.T.; Heeren, M.V.; Irigoyen, M.C.; De Angelis, K. Maximal exercise test is a useful method for physical capacity and oxygen consumption determination in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2007, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Before exercise training | After exercise training | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | Sham-ET | AoS | AoS-ET | Sham | Sham-ET | AoS | AoS-ET | |

| BW (g) | 469 ± 38 | 472 ± 55 | 450 ± 54 | 452 ± 59 | 519 ± 45 | 494 ± 60 | 494 ± 70 | 487 ± 59 |

| HR (bpm)& | 285 (280; 301) | 290 (269; 301) | 290 (262; 312) | 290 (280; 301) | 298 ± 42 | 292 ± 37 | 293 ± 43 | 305 ± 36 |

| LVDD (mm)& | 7.41 (6.90; 7.66) | 7.30 (6.90; 7.59) | 7.88 (7.21; 8.46) | 7.41 (6.32; 7.95) | 7.41 (7.15; 7.66) | 7.41 (7.09; 7.92) | 8.43 (7.27; 9.13) ** | 7.92 (7.34; 8.49) |

| LVSD (mm)& | 3.07 (2.81; 3.32) | 2.81 (2.55; 3.07) | 3.58 (3.24; 4.02) | 3.32 (2.74; 3.58) | 3.07 (2.81; 3.32) | 3.07 (2.81; 3.38) | 3.65 (3.32; 5.40) ** | 3.58 (2.81; 4.52) |

| PWDT (mm)& | 1.53 (1.53; 1.53) | 1.53 (1.53; 1.57) | 3.07 (2.81; 3.07) * | 2.92 (2.81; 3.07) # | 1.53 (1.53; 1.65) | 1.53 (1.53; 1.61) | 2.81 (2.55; 3.03) ** | 2.30 (2.55; 2.81) ## |

| ISDT (mm)& | 1.56 (1.53; 1.65) | 1.55 (1.53; 1.65) | 3.07 (2.98; 3.24) * | 3.07 (3.07; 3.32) # | 1.62 (1.53; 1.70) | 1.60 (1.53; 1.65) | 2.95 (2.81; 3.07) ** | 2.81 (2.55; 3.07) ## |

| RWT | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 0.43 ± 0.04 | 0.76 ± 0.13 * | 0.81 ± 0.11 # | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 0.42 ± 0.03 | 0.68 ± 0.14 ** | 0.68 ± 0.11 ## |

| LA/Ao& | 1.21 (1.19; 1.30) | 1.23 (1.19; 1.29) | 1.93 (1.67; 2.00) * | 1.87 (1.52; 2.11) # | 1.23 ± 0.09 | 1.24 ± 0.09 | 1.93 ± 0.19 ** | 1.79 ± 0.19 ##§ |

| E wave (cm/s) | 81 ± 7 | 83 ± 8 | 124 ± 24 * | 127 ± 22 # | 85 ± 7 | 82 ± 9 | 130 ± 20 ** | 120 ± 25 ##§ |

| E/A | 1.64 ± 0.22 | 1.64 ± 0.25 | 3.55 ± 1.67 * | 3.82 ± 2.00 # | 1.50 ± 0.20 | 1.54 ± 0.18 | 5.22 ± 1.42 ** | 3.82 ± 1.85 ##§ |

| E’ (cm/s)& | 5.60 (5.30; 5.80) | 5.60 (3.20; 6.10) | 5.40 (3.70; 6.25) | 5.40 (3.70; 6.12) | 6.13 ± 0.77 | 6.20 ± 0.73 | 5.19 ± 0.99 ** | 5.40 ± 1.18 ## |

| A’ (cm/s)& | 3.75 (3.70; 3.90) | 3.70 (3.35; 4.20) | 3.30 (3.03; 5.35) | 3.20 (3.20; 3.75) | 4.24 ± 0.72 | 4.10 ± 0.60 | 3.08 ± 1.20 ** | 3.95 ± 1.50 § |

| E/E’ | 14.3 ± 1.58 | 14.9 ± 1.98 | 25.9 ± 6.78 * | 26.3 ± 7.82 # | 14.1 ± 2.24 | 13.4 ± 1.6 | 25.6 ± 4.85 ** | 22.5 ± 3.66 ##§ |

| EDT (ms) | 48 ± 7 | 48 ± 5 | 34 ± 11 * | 36 ± 13 # | 49 ± 6 | 50 ± 4 | 28 ± 8 ** | 34 ± 11 ##§ |

| PWSV (cm/s) | 67 ± 9 | 71 ± 7 | 53 ± 12 * | 55 ± 8 # | 68 ± 9 | 70 ± 9 | 37 ± 10 ** | 49 ± 9 ##§ |

| FS (%) | 26 ± 3 | 28 ± 4 | 25 ± 4 | 25 ± 4 # | 26 ± 3 | 25 ± 4 | 23 ± 5 ** | 24 ± 4 |

| EF (%)& | 93 (91; 94) | 94 (92; 95) | 90 (87; 92) | 89 (79; 92) # | 93 ± 2 | 92 ± 3 | 86 ± 9 ** | 90 ± 4 § |

| Sham | Sham-ET | AoS | AoS-ET | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSA (mm2) | 1.14 ± 0.13 | 1.15 ± 0.14 | 1.16 ± 0.16 | 1.20 ± 0.19 |

| DT (g/mm2) | 6.23 ± 1.43 | 6.12 ± 1.61 | 5.20 ± 1.11 | 5.23 ± 1.96 |

| RT (g/mm2) | 0.57 ± 0.19 | 0.61 ± 0.18 | 0.82 ± 0.22 * | 0.66 ± 0.17 § |

| +dT/dt (g/mm2/s) | 66.6 ± 17.2 | 65.9 ± 18.1 | 46.9 ± 10.3 * | 47.9 ± 20.0 # |

| −dT/dt (g/mm2/s) | 21.8 ± 5.50 | 22.1 ± 5.39 | 24.2 ± 5.57 | 23.0 ± 7.61 |

| TPT (ms) # | 180 (180; 200) | 180 (160; 180) | 210 (182; 220) | 200 (180; 210) # |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).