1. Introduction

Engaging in sufficient Physical Activity (PA) can have significant benefits for the overall health of children and adolescents. This includes improvements in their physical well-being, as well as positive impacts on their mental and social-emotional health [

1]. Despite this, studies indicate that adolescents are failing to meet the recommended level of physical activity [

2]. As with adolescents in other countries, Czech adolescents are facing the same issue as a significant proportion of them do not meet public health guidelines for recommended levels of physical activity [

3].

The conduct of individuals regarding their health is significantly impacted by social norms. Such influence ranges from reinforcing favourable behaviours that can safeguard and improve one's well-being, to promoting unfavourable actions that elevate the possibility of detrimental health outcomes [

4].

The development of the theoretical basis for the investigation of social norms is grounded in the evolution of several frameworks. Initially, social norms were defined and explored within larger theories such as the theory of reasoned action (TRA) and theory planned behaviour (TPB) [

5]. The focus theory of normative conduct (FTNC) evolved from the TPB [

6] focusing exclusively on social norms.

The FTNC framework delineates norms into two distinct categories: injunctive and descriptive [

7]. Injunctive norms involve an evaluative component, whereas descriptive norms do not. Descriptive norms refer to individuals' perceptions of common behaviours within their social context. When faced with unfamiliar situations, people may rely on descriptive norms as a shortcut for understanding socially appropriate behaviour. By observing the actions of others around them and if widespread participation indicates social acceptability, individuals may adopt similar conduct themselves.

As the study of social norms advanced, researchers began to consider the referent group for injunctive and descriptive norms in terms of proximity: either proximal or distal. Proximal refers to an individual's close friend circle (for example, a few friends they spend most of their time with). On the other hand, distal pertains to a larger population such as students at one's university [

8,

9].

As the research on social norms has progressed, correlational studies have provided compelling evidence that descriptive norms have a positive association with both intention and behaviour. The effectiveness of norms as a means of influencing behaviour has been demonstrated across a wide range of behaviours, such as promoting healthier eating habits, encouraging energy conservation, and reducing binge drinking.[

10,

11,

12,

13] Studies investigating the connection between social norms and physical activity are limited. Even though research on social norms has not placed much emphasis on physical activity, certain studies demonstrate a correlation between the two [

4,

14,

15,

16].

In addition, the findings of Vorlíček et al [

17,

18] on a sample of Czech adolescents indicate that there might be room for targeted intervention based on the social norms approach to increase the PA of adolescents or at least strengthen their actual positive behaviour.

The Social Norms Approach (SNA) is commonly used to encourage positive health behaviours by addressing individuals' misperceptions of their peers' attitudes and actions.[

19] Studies have shown that people tend to overestimate the prevalence of negative behaviours and attitudes among their peers while underestimating positive ones. This misperception can lead to negative behaviours such as excessive alcohol consumption and a decrease in positive behaviours such as healthy eating, using sun protection, and being physically active [

20].

Understanding how Czech adolescents perceive their physical activity is crucial for developing effective interventions and strategies that encourage a more active lifestyle. Given that the discrepancy between self-perceived levels of behaviour and perceived social norms is crucial to the application of the SNA, our primary aim was to investigate whether Czech adolescents misperceive their peers’ PA behaviours. Furthermore, we aimed to investigate the associations between their self-perceived PA and descriptive social norms PA and whether these associations differed with gender and class grade.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure Sample and Participant Selection

The present cross-sectional study involved 1289 adolescents (46% of them boys) aged 11–15 years (mean 12.95 ± 3.6 years) from 12 randomly selected schools (Grades 6–9) from the Czech Republic. Schools with a specific focus on sport and schools for pupils with special educational needs were not recruited. Measurement was voluntary, and no incentives were provided in return for participation. Less than five percent of the adolescents opted out of the data collection.

2.2. Assessments and Measures

For the purposes of this study, we used questions on MVPA and VPA from HBSC study as a feasible and valid survey instrument.[

21]

Self-perceived MVPA was assessed using the following item:

“Physical activity is any activity that increases your heart rate and makes you get out of breath some of the time. Physical activity can be done in sports, school activities, playing with friends, or walking to school. Some examples of physical activity are running, brisk walking, rollerblading, biking, dancing, skateboarding, swimming, soccer, basketball, football, surfing.”

“Over the past 7 days, on how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60 minutes per day? Please add up all the time you spent in physical activity each day.”

The students could select a response from eight options, ranging from “zero days (never)” to “seven days”.

Descriptive norm on MVPA was assessed using modified item:

“Over the past 7 days, on how many days do you think most of your classmates were physically active for a total of at least 60 minutes per day?” The students could select a response from eight options, ranging from “zero days (never)” to “seven days”.

Self-perceived VPA was assessed using the following item:

“Outside school hours: how often do you usually exercise in your free time so much that you get out of breath or sweat?”

The students could select a response from seven options, ranging from “Every day” “4 to 6 times a week” “2 to 3 times a week” “Once a week” “Once a month” “Less than once a month” to “Never”.

Descriptive norm on VPA was assessed using the following item:

“Outside school hours: how often do you think most of your classmates usually exercise in their free time so much that you get out of breath or sweat?”

The students could select a response from seven options, ranging from “Every day” “4 to 6 times a week” “2 to 3 times a week” “Once a week” “Once a month” “Less than once a month” to “Never”.

2.3. Procedure

The data were collected from 2020 to 2021 in regular school weeks during the spring and autumn seasons. The pupils filled in an electronic questionnaire at school during class under the supervision of teachers and researchers.

2.4. Data Processing

Statistical data processing was performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Basic descriptive statistics, Chi-squared tests and binomial regression models were used to analyse the data.

3. Results

MVPA

According to results showed in

Table 1, 18% of Czech adolescents reported more than 60 minutes of MVPA daily. Significantly more boys than girls (20.6% vs. 15.8%) had 60 minutes of daily MVPA (χ

2 = 22.21; p = 0.002). Levels MVPA gradually and significantly decreased from 6

th grade to 9

th grade (χ

2 = 50.927; p < 0.001). While in 6

th grade 23.9% of adolescents had more than 60 minutes of daily MVPA, in 7

th grade it was 21.9%, in 8

th 16.8% and in 9

th it was only 8.4%.

Regarding perceived descriptive norms in MVPA, only 3.9% of adolescents believed that their peers have at least 60 minutes of daily MVPA. (

Table 2) Boys perceived their peers as having more MVPA compared to girls (χ

2 = 27.435; p = 0.001). We did not observe significant differences across grades (χ

2 = 31.954; p = 0.059).

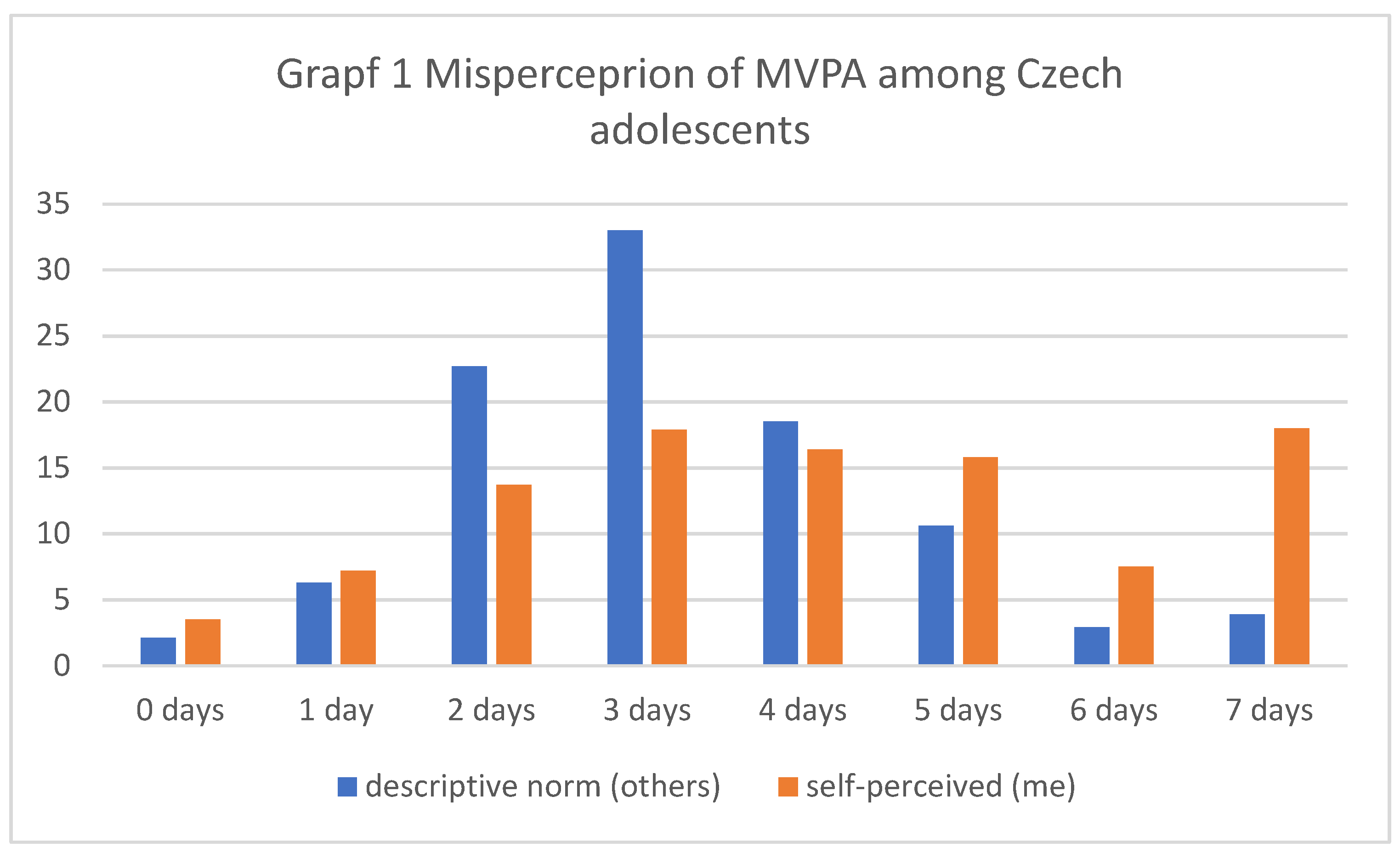

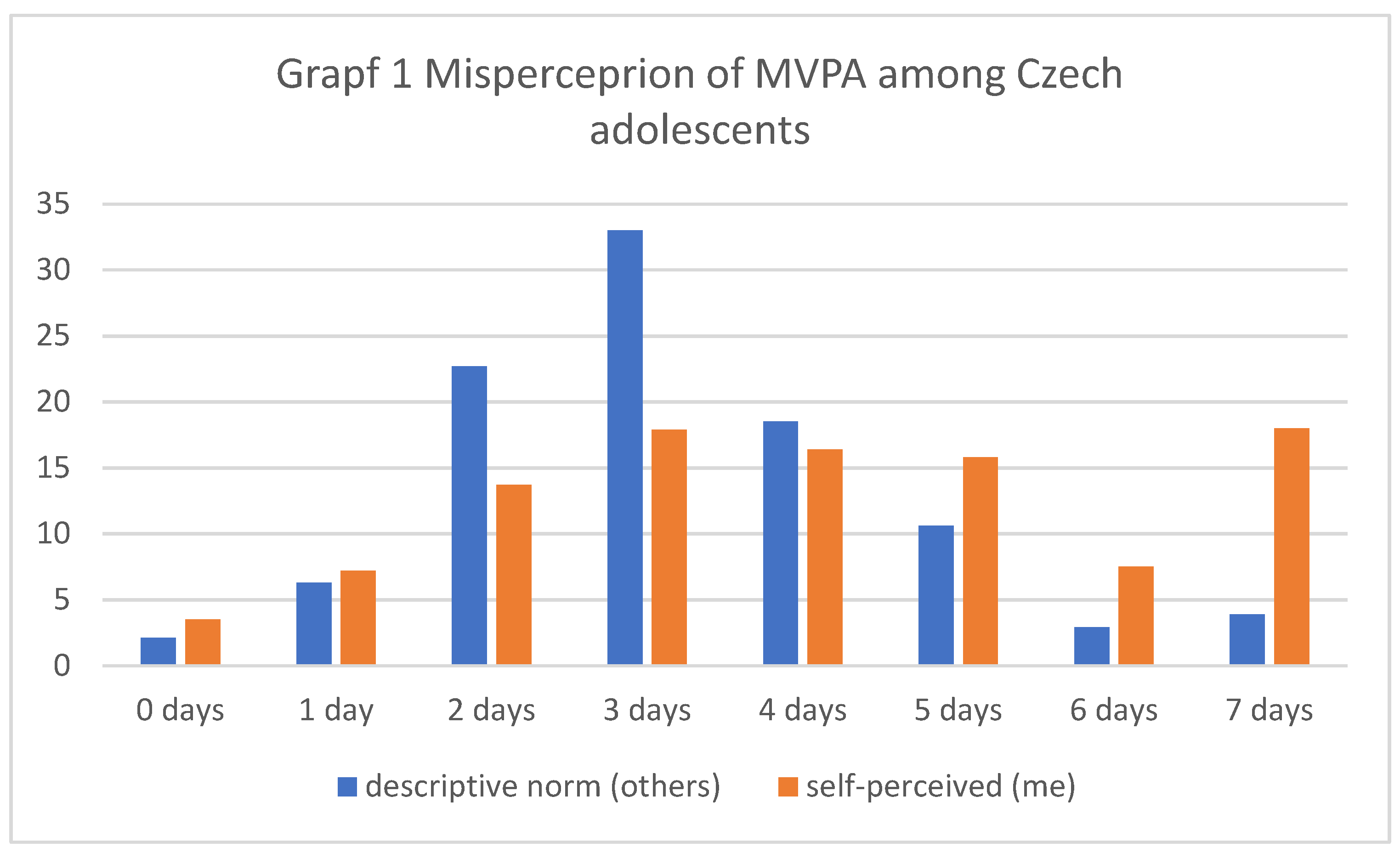

When comparing self-perceived MVPA and perceived descriptive norm in MVPA (i.e. adolescents own behaviour vs. behaviour of their peers) we found clear misperception. (Graph 1) Adolescents perceive the level of MVPA of their peers as much lower. While majority of adolescent (57.7%) have reported 60 minutes of MVPA at least 4 times a week, only 35.9% believe that their peers have 60 minutes of MVPA at least 4 times a week. This misperception is present both for boys and girls and across all grades (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

In order to identify which adolescents misperceive MVPA, we performed binominal logistic regression. Sample was dichotomized into two groups underestimated MVPA (1) vs. rest of the sample (0). In four steps we entered sex, grade, school and own MVPA.

According to results girls and older students tend to significantly more underestimate the prevalence of MVPA among their peers. School had no effect perception of MVPA. After entering the own self-perceived MVPA into the model almost all variance is explained and the most gradient appeared. Adolescents who have 0 days of MVPA weekly underestimate the MVPA of their peers almost 9 times more compared to their peers who have daily 60 minutes MVPA (OR 8.974). The more passive adolescents are, the more they tend to perceive this behaviour as less frequent, normal.

VPA

According to results showed in

Table 4, 29.8% of Czech adolescents reported VPA at least 4 times a week. Significantly more boys than girls had VPA at least 4 times a week (χ

2 = 23.03; p = 0.001). Levels VPA gradually and significantly decreased from 6

th grade to 9

th grade (χ

2 = 50.51; p < 0.001). While in 6

th grade 13% of adolescents had daily VPA, in 7

th grade it was 10%, in 8

th 8% and in 9

th it was only 4%.

Regarding perceived descriptive norms in VPA, only 10% of adolescents believed that their peers VPA everyday (

Table 5). Boys perceived their peers as having more VPA compared to girls (χ

2 = 22.67; p = 0.001). Levels VPA gradually and significantly decreased from 6

th grade to 9

th grade (χ

2 = 39.86; p < 0.002).

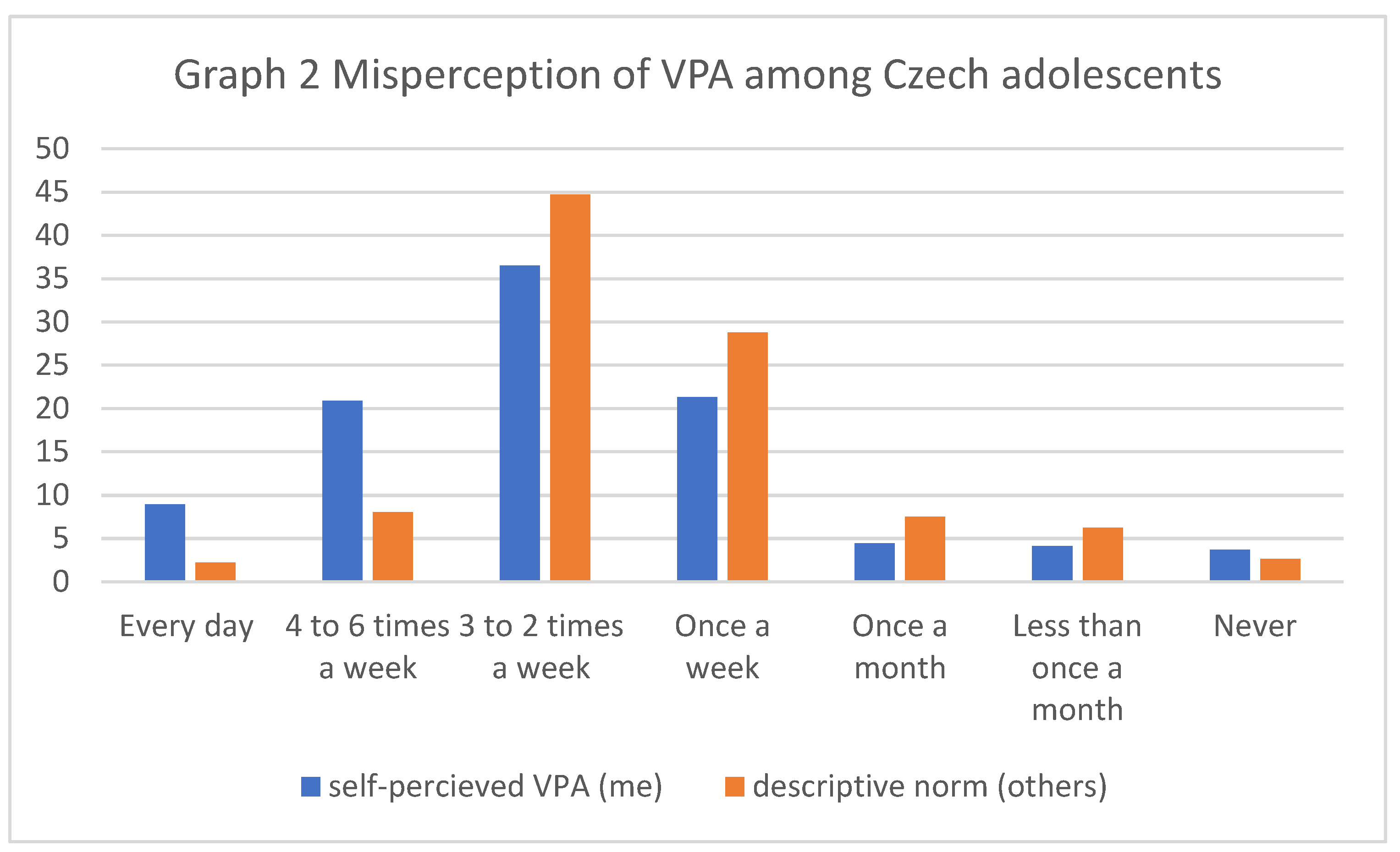

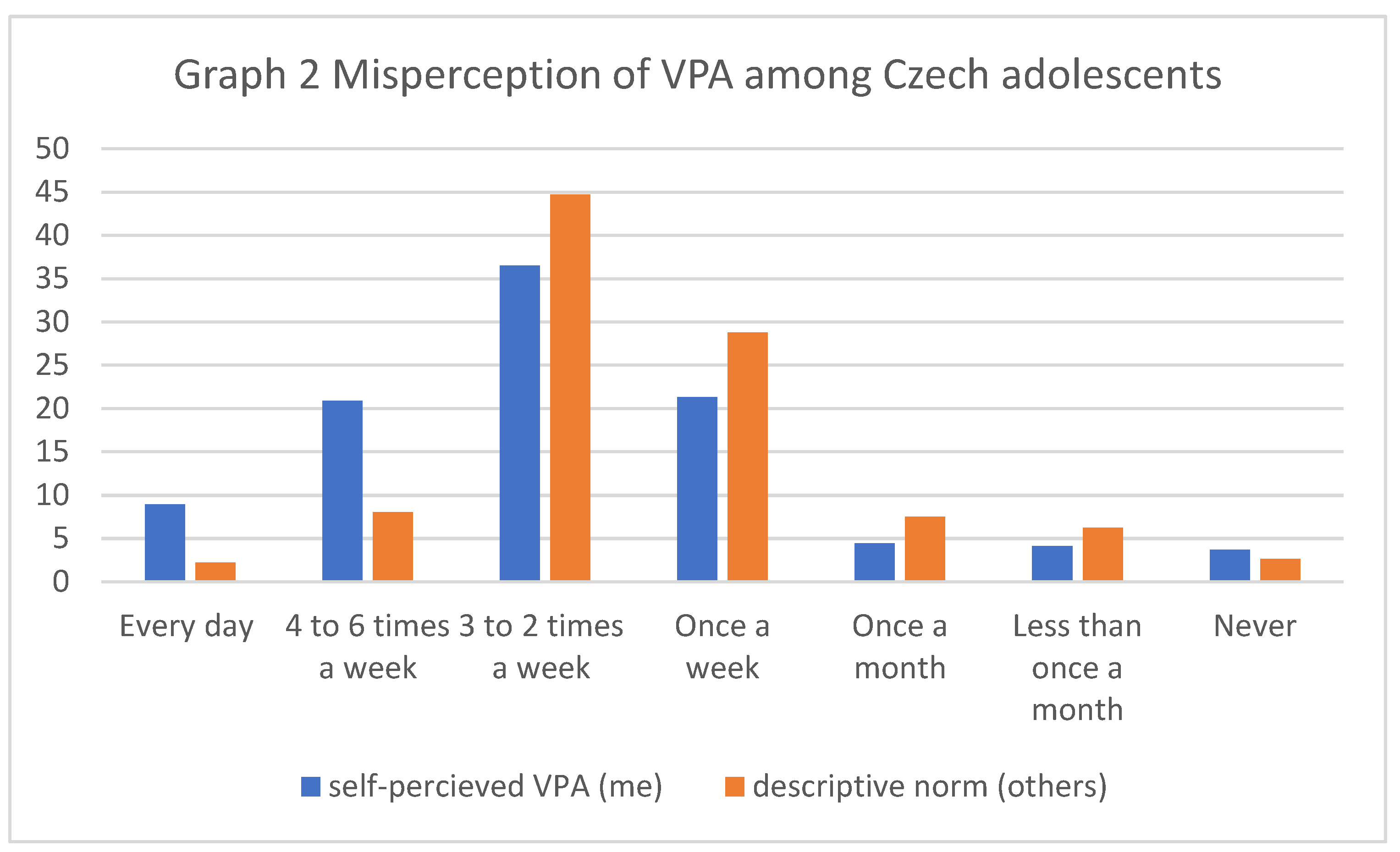

When comparing self-perceived VPA and perceived descriptive norm in VPA (i.e., adolescents own behaviour vs. behaviour of their peers) we found clear misperception. (Graph 2) While almost 30%of adolescent have reported VPA at least 4 times a week, only 10% believe that their peers have VPA at least 4 times a week. This misperception is present both for boys and girls and across all grades (

Table 4 and

Table 5).

In order to identify which adolescents misperceive VPA, we performed binominal logistic regression. Sample was dichotomized into two groups underestimated VPA (1) vs. rest of the sample (0). In four steps we entered sex, grade, school and own VPA.

In general, the results were very similar to what we reported for MVPA above, although less expressive. Girls and older students tend to significantly more underestimate the prevalence of VPA among their peers. School had no effect on perception of VPA. After entering the own self-perceived VPA into the model almost all variance is explained and the most gradient appeared. Adolescents who had no VPA during last month underestimate the VPA of their peers more than 9 times compared to their peers who had daily VPA (OR 3.134). As for MVPA, the less VPA adolescents have, the more they tend to perceive this behaviour as less frequent, normal.

4. Discussion

Our primary aim was to investigate whether Czech adolescents misperceive their peers’ PA behaviours. Furthermore, we aimed to investigate the associations between their self-perceived PA and descriptive social norms PA and whether these associations differed with gender and class grade. Thus, we were able to evaluate the suitability of utilizing the Social Norms Approach as an intervention strategy for promoting sufficient PA among adolescents. Perkins[

22] has identified two pre-conditions that must be met before implementing SNA properly. The first condition necessitates a discrepancy between perceived and actual behaviour, which indicates overestimation of problem conduct. The second condition demands that at least half of the population behaves responsibly; given that individuals strive to conform with societal norms, employing a social norms message campaign may inadvertently encourage harmful conduct if most people engage in it. Hence, if more than 50% violate desirable behaviours targeted by the intervention program, recognizing SNA's limitations would prove critical in decision-making regarding its implementation potentiality.

Our study points out that there is a discrepancy between the self-perceived levels of own MVPA and VPA and the perceived descriptive norms of peers’ MVPA and VPA. Adolescents underestimate the prevalence of sufficient MVPA and VPA, and thus perceived descriptive norms in MVPA and VPA are worse than levels of own MVPA and VPA. Girls and older students tend to significantly more underestimate the prevalence of VPA among their peers. School had no effect on perception of VPA. We confirmed clear relation between descriptive norms and PA. According to our findings, the more passive adolescents are, the more they tend to perceive this behaviour as less frequent, normal. In previous literature, there is general support for the notion that social norms can influence individual decisions to be physically active [

4]. Several studies have explored the correlation between descriptive social norms and physical activity, concluding that the perceived behaviour of one's peers strongly influenced their likelihood to engage in PA [

23,

24]. Ball et al [

23] also concluded that descriptive norms had an impact separate from social support and proposed adjusting social norms in interventions aimed at encouraging higher levels of physical activity.

We found that grade had effect on misperception of MVPA and VPA. On the contrary school had no effect. If may define a grade as more proximal and school more distal norms, our findings would be in line with previous research which indicates that norms closer to an individual have a greater impact on their behaviour than those further away. For example, studies by Yun and Silk [

9] showed that proximal descriptive and injunctive norms had more predictive power in promoting healthy food choices compared to distal norms. Likewise, Korcuska and Thombs [

25] found that college students' alcohol use was more influenced by perceived normative behaviours of close friends than the typical student.

In general, we found that unfortunately very low number of adolescents fulfilled the recommendations for sufficient physical activity, both MVPA and VPA. We also confirmed that boys are more active than girls and that PA level gradually decrease with older age. These findings are fully in line with other Czech [

3,

26,

27] studies but also with wider regional [

28,

29,

30,

31] and global situation [

1].

The study has a number of strengths and limitations that must be considered. A limitation worth noting is that the results rely on self-reported data, which may produce reporting biases or various alternative explanations (such as social pressure to respond in particular ways). Our participants reported their own physical activity levels along with their peers. Also, due to our cross-sectional approach, we cannot conclude any causal relationship between actual PA levels and perceived norms among adolescents. Another limitation could be that we focused solely descriptive norms. It was revealed that modifying descriptive norms alone may not be sufficient in changing behaviour [

32]. The direct impact of descriptive norms on actions is considered unlikely, as there are likely moderators or mediators involved between these norms and conduct. In this context, injunctive norms, outcome expectations, and group identity have been identified as key normative mechanisms [

33], while peer communication and issue familiarity have also received some attention in related research studies [

34].

Nonetheless, this research highlights the significance of analysing adolescents' physical activities while contemplating their perceptions towards social conventions when physically active - an area relatively less researched so far according to existing literature.

5. Conclusions

Our study points out that there is a discrepancy between the self-perceived levels of own MVPA and VPA and the perceived descriptive norms of peers’ MVPA and VPA. Adolescents underestimate the prevalence of sufficient MVPA and VPA, and thus perceived descriptive norms in MVPA and VPA are worse than levels of own MVPA and VPA. These findings indicate room for targeted intervention based on the social norms based approaches to increase the physical activity of adolescents or at least strengthen their actual positive behaviour.

Author Contributions

F.S. conceptualized and designed the study, conducted the data collection, and drafted the manuscript. D.K. assisted in writing the manuscript. M.V. assisted with the statistical analysis and writing of the manuscript. L.R. and J.V. assisted with the data collection and writing of the manuscript. J.M. assisted with the study design, data collection, and writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by the research grants of the Czech Science Foundation (No. 17-24378S) “Social norms intervention in the prevention of excessive sitting and promotion of physical activity among Czech adolescents”, and the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic (No. TL02000033) “Primary prevention of sedentary behavior and promotion of school-based physical activity based on social norms and a social marketing approach and using elements of e-health/m-health systems”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved under reference number 38/17 by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Physical Culture, Palacký University Olomouc, which is governed by the ethical standards set out in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed Consent Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- OWEN, K.B.; FOLEY, B.C.; WILHITE, K.; BOOKER, B.; LONSDALE, C.; REECE, L.J. Sport Participation and Academic Performance in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2022, 54, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global Trends in Insufficient Physical Activity among Adolescents: A Pooled Analysis of 298 Population-Based Surveys with 1·6 Million Participants. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gába, A.; Baďura, P.; Vorlíček, M.; Dygrýn, J.; Hamřík, Z.; Kudláček, M.; Rubín, L.; Sigmund, E.; Sigmundová, D.; Vašíčková, J. The Czech Republic’s 2022 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth: A Rationale and Comprehensive Analysis. J Exerc Sci Fit 2022, 20, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randazzo, K.D.; Solmon, M. Exploring Social Norms as a Framework to Understand Decisions to Be Physically Active. 2017; 70, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Nolan, J.M.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. The Constructive, Destructive, and Reconstructive Power of Social Norms. Psychol Sci 2007, 18, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A Focus Theory of Normative Conduct: Recycling the Concept of Norms to Reduce Littering in Public Places. J Pers Soc Psychol 1990, 58, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H. Influences of Norm Proximity and Norm Types on Binge and Non-Binge Drinkers: Examining the under-Examined Aspects of Social Norms Interventions on College Campuses. J Subst Use 2006, 11, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, D.; Silk, K.J. Social Norms, Self-Identity, and Attention to Social Comparison Information in the Context of Exercise and Healthy Diet Behavior. Health Commun 2011, 26, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pischke, C.R.; Zeeb, H.; van Hal, G.; Vriesacker, B.; McAlaney, J.; Bewick, B.M.; Akvardar, Y.; Guillen-Grima, F.; Orosova, O.; Salonna, F.; et al. A Feasibility Trial to Examine the Social Norms Approach for the Prevention and Reduction of Licit and Illicit Drug Use in European University and College Students. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmer, S.M.; Pischke, C.R.; Van Hal, G.; Vriesacker, B.; Dempsey, R.C.; Akvardar, Y.; Guillen-Grima, F.; Salonna, F.; Stock, C.; Zeeb, H. Personal and Perceived Peer Use and Attitudes towards the Use of Nonmedical Prescription Stimulants to Improve Academic Performance among University Students in Seven European Countries. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmer, S.M.; Mikolajczyk, R.T.; McAlaney, J.; Vriesacker, B.; Van Hal, G.; Akvardar, Y.; Guillen-Grima, F.; Salonna, F.; Stock, C.; Dempsey, R.C.; et al. Illicit Substance Use among University Students from Seven European Countries: A Comparison of Personal and Perceived Peer Use and Attitudes towards Illicit Substance Use. Prev Med (Baltim) 2014, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAlaney, J.; Helmer, S.M.; Stock, C.; Vriesacker, B.; Van Hal, G.; Dempsey, R.C.; Akvardar, Y.; Salonna, F.; Kalina, O.; Guillen-Grima, F.; et al. Personal and Perceived Peer Use of and Attitudes Toward Alcohol Among University and College Students in Seven EU Countries: Project SNIPE. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2015, 76, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draper, C.E.; Grobler, L.; Micklesfield, L.K.; Norris, S.A. Impact of Social Norms and Social Support on Diet, Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour of Adolescents: A Scoping Review. Child Care Health Dev 2015, 41, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucksch, J.; Kopcakova, J.; Inchley, J.; Troped, P.J.; Sudeck, G.; Sigmundova, D.; Nalecz, H.; Borraccino, A.; Salonna, F.; Dankulincova Veselska, Z.; et al. Associations between Perceived Social and Physical Environmental Variables and Physical Activity and Screen Time among Adolescents in Four European Countries. Int J Public Health 2019, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.J.H.; Lin, J.H.; Hsu, Y.W.; Chou, C.C.; Wang, E.T.W.; Yeh, L.C. Adolescents’ Physical Activities and Peer Norms: The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy. Percept Mot Skills 2014, 118, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorlíček, M.; Bad’ura, P.; Mitáš, J.; Kolarčik, P.; Rubín, L.; Vašíčková, J.; Salonna, F. How Czech Adolescents Perceive Active Commuting to School: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorlíček, M.; Rubín Jan Dygrýn Josef Mitáš, L. Does Active Commuting Help Czech Adolescents Meet Health Recommendations for Physical Activity? Tělesná kultura 2018, 40, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmer, S.M.; Muellmann, S.; Zeeb, H.; Pischke, C.R. Development and Evaluation of the Efficacy of a Web-Based ’Social Norms’-Intervention for the Prevention and Reduction of Substance Use in a Cluster-Controlled Trial Conducted at Eight German Universities. BMC Public Health 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, R.C.; McAlaney, J.; Bewick, B.M. A Critical Appraisal of the Social Norms Approach as an Interventional Strategy for Health-Related Behavior and Attitude Change. Front Psychol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moor, I.; Winter, K.; Bilz, L.; Bucksch, J.; Finne, E.; John, N.; Kolip, P.; Paulsen, L.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Schlattmann, M.; et al. The 2017/18 Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study – Methodology of the World Health Organization’s Child and Adolescent Health Study. Journal of Health Monitoring 2020, 5, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, H. Wesley. The Social Norms Approach to Preventing School and College Age Substance Abuse : A Handbook for Educators, Counselors, and Clinicians. 2003, 320.

- Ball, K.; Jeffery, R.W.; Abbott, G.; McNaughton, S.A.; Crawford, D. Is Healthy Behavior Contagious: Associations of Social Norms with Physical Activity and Healthy Eating. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2010, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priebe, C.S.; Spink, K.S. Less Sitting and More Moving in the Office: Using Descriptive Norm Messages to Decrease Sedentary Behavior and Increase Light Physical Activity at Work. Psychol Sport Exerc 2015, 19, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korcuska, J.S.; Thombs, D.L. Gender Role Conflict and Sex-Specific Drinking Norms: Relationships to Alcohol Use in Undergraduate Women and Men. J Coll Stud Dev 2003, 44, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gába, A.; Mitáš, J.; Jakubec, L. Associations between Accelerometermeasured Physical Activity and Body Fatness in School-Aged Children. Environ Health Prev Med 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frömel, K.; Groffik, D.; Chmelík, F.; Cocca, A.; Skalik, K. Physical Activity of 15–17 Years Old Adolescents in Different Educational Settings: A Polish-Czech Study. Cent Eur J Public Health 2018, 26, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brindova, D.; Veselska, Z.D.; Klein, D.; Hamrik, Z.; Sigmundova, D.; van Dijk, J.P.; Reijneveld, S.A.; Geckova, A.M. Is the Association between Screen-Based Behaviour and Health Complaints among Adolescents Moderated by Physical Activity? Int J Public Health 2015, 60, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ács, P.; Bergier, J.; Salonna, F.; Junger, J.; Melczer, C.; Makai, A. GENDER DIFFERENCES IN PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AMONG SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENTS IN THE VISEGRAD COUNTRIES (V4). Health Problems of Civilization 2016, 3, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ács, P.; Bergier, J.; Salonna, F.; Junger, J.; Melczer, C.; Makai, A. Gender Differences in Physical Activity among Secondary School Students in the Visegrad Countries (V4). Health Problems of Civilization 2016, 3, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ács, P.; Bergier, B.; Bergier, J.; Niźnikowska, E.; Junger, J.; Salonna, F. Students Leisure Time as a Determinant of Their Physical Activity at Universities of the EU Visegrad Group Countries. Health Problems of Civilization 2016, 4, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, R.N. Modeling the Relationship between Descriptive Norms and Behaviors: A Test and Extension of the Theory of Normative Social Behavior (TNSB). Health Commun 2008, 23, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real, K.; Rimal, R.N. Friends Talk to Friends about Drinking: Exploring the Role of Peer Communication in the Theory of Normative Social Behavior. Health Commun 2007, 22, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimal, R.N.; Mollen, S. The Role of Issue Familiarity and Social Norms: Findings on New College Students’ Alcohol Use Intentions. J Public Health Res 2013, 2, jphr.2013.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Self-perceived MVPA among Czech adolescents according to gender and school class grade.

Table 1.

Self-perceived MVPA among Czech adolescents according to gender and school class grade.

| |

|

0 days |

1 day |

2 days |

3 days |

4 days |

5 days |

6 days |

7 days |

Total |

χ2 |

| |

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

(p) |

| Total |

|

45 |

3.5% |

93 |

7.2% |

176 |

13.7% |

231 |

17.9% |

211 |

16.4% |

204 |

15.8% |

97 |

7.5% |

232 |

18.0% |

1289 |

|

| Boys |

|

27 |

4.6% |

30 |

5.1% |

72 |

12.2% |

97 |

16.4% |

90 |

15.2% |

105 |

17.7% |

49 |

8.3% |

122 |

20.6% |

592 |

22.21 |

| Girls |

|

18 |

2.6% |

63 |

9.0% |

104 |

14.9% |

134 |

19.2% |

121 |

17.4% |

99 |

14.2% |

48 |

6.9% |

110 |

15.8% |

697 |

(0.002) |

| Grade |

6th |

15 |

4.3% |

20 |

5.8% |

35 |

10.1% |

58 |

16.7% |

63 |

18.2% |

44 |

12.7% |

29 |

8.4% |

83 |

23.9% |

347 |

|

| 7th |

7 |

2.3% |

25 |

8.0% |

40 |

12.9% |

46 |

14.8% |

46 |

14.8% |

59 |

19.0% |

20 |

6.4% |

68 |

21.9% |

311 |

50.927 |

| 8th |

9 |

2.7% |

20 |

6.0% |

50 |

15.0% |

62 |

18.6% |

52 |

15.6% |

58 |

17.4% |

26 |

7.8% |

56 |

16.8% |

333 |

(<0.001) |

| 9th |

14 |

4.7% |

28 |

9.4% |

51 |

17.1% |

65 |

21.8% |

50 |

16.8% |

43 |

14.4% |

22 |

7.4% |

25 |

8.4% |

298 |

|

Table 2.

Percieved descriptive norms of MVPA among Czech adolescents according to gender and school class grade.

Table 2.

Percieved descriptive norms of MVPA among Czech adolescents according to gender and school class grade.

| |

|

0 days |

1 day |

2 days |

3 days |

4 days |

5 days |

6 days |

7 days |

χ2 |

| |

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

(p) |

| Total |

|

27 |

2.1% |

81 |

6.3% |

293 |

22.7% |

425 |

33.0% |

239 |

18.5% |

137 |

10.6% |

37 |

2.9% |

50 |

3.9% |

|

| Boys |

|

16 |

2.7% |

34 |

5.7% |

126 |

21.3% |

175 |

29.6% |

113 |

19.1% |

77 |

13.0% |

15 |

2.5% |

36 |

6.1% |

27.435 |

| Girls |

|

11 |

1.6% |

47 |

6.7% |

167 |

24.0% |

250 |

35.9% |

126 |

18.1% |

60 |

8.6% |

22 |

3.2% |

14 |

2.0% |

(<0.001) |

| Grade |

6th |

5 |

1.4% |

25 |

7.2% |

77 |

22.2% |

108 |

31.1% |

64 |

18.4% |

38 |

11.0% |

16 |

4.6% |

14 |

4.0% |

|

| 7th |

8 |

2.6% |

14 |

4.5% |

65 |

20.9% |

96 |

30.9% |

64 |

20.6% |

41 |

13.2% |

7 |

2.3% |

16 |

5.1% |

31.954 |

| 8th |

7 |

2.1% |

16 |

4.8% |

84 |

25.2% |

103 |

30.9% |

62 |

18.6% |

36 |

10.8% |

10 |

3.0% |

15 |

4.5% |

(0.059) |

| 9th |

7 |

2.3% |

26 |

8.7% |

67 |

22.5% |

118 |

39.6% |

49 |

16.4% |

22 |

7.4% |

4 |

1.3% |

5 |

1.7% |

|

Table 3.

Underestimation of norms in Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity (results of logistic regression).

Table 3.

Underestimation of norms in Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity (results of logistic regression).

| |

|

|

|

OR(95% C.I.) |

p |

| Model 1 |

Gender |

Boys |

|

ref. |

|

| Girls |

|

1.469(1.169 - 1.846) |

0.001 |

| Model 2 |

Gender |

Boys |

|

ref. |

|

| Girls |

|

1.468(1.166 - 1.847) |

0.001 |

| Grade |

6th |

|

ref. |

0.002 |

| 7th |

|

0.876(0.640 - 1.200) |

0.410 |

| 8th |

|

1.052(0.770 - 1.437) |

0.752 |

| 9th |

|

1.670(1.193 - 2.339) |

0.003 |

| Model 3 |

Gender |

Boys |

|

ref. |

|

| Girls |

|

1.474(1.171 - 1.855) |

0.001 |

| Grade |

6th |

|

ref. |

0.003 |

| 7th |

|

0.875(0.639 - 1.199) |

0.407 |

| 8th |

|

1.043(0.763 - 1.426) |

0.790 |

| 9th |

|

1.647(1.174 - 2.309) |

0.004 |

| School |

|

|

0.984(0.954 - 1.015) |

0.306 |

| Model 4 |

Gender |

Boys |

|

ref. |

0.030 |

| Girls |

|

1.317(1.026 - 1.690) |

|

| Grade |

6th |

|

ref. |

0.164 |

| 7th |

|

0.841(0.597 - 1.184) |

0.321 |

| 8th |

|

0.948(0.676 - 1.330) |

0.758 |

| 9th |

|

1.282(0.888 - 1.851) |

0.185 |

| School |

|

|

0.992(0.960 - 1.026) |

0.660 |

| MVPA |

7 days |

|

ref. |

0.000 |

| 6 days |

|

0.843(0.516 - 1.377) |

0.495 |

| 5 days |

|

1.354(0.923 - 1.988) |

0.121 |

| 4 days |

|

2.549(1.725 - 3.764) |

0.000 |

| 3 days |

|

5.402(3.548 - 8.223) |

0.000 |

| 2 days |

|

7.735(4.706 - 12.714) |

0.000 |

| 1 days |

|

9.754(4.908 - 19.383) |

0.000 |

| 0 days |

|

8.974(3.636 - 22.153) |

0.000 |

Table 4.

Self-perceived VPA among Czech adolescents according to gender and school class grade.

Table 4.

Self-perceived VPA among Czech adolescents according to gender and school class grade.

| |

|

Every day |

4 to 6 times a week |

3 to 2 times a week |

Once a week |

Once a month |

Less than once a month |

Never |

|

| χ2 |

| (p) |

| |

| |

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

| Total |

|

115 |

8.9% |

269 |

20.9% |

470 |

36.5% |

274 |

21.3% |

57 |

4.4% |

53 |

4.1% |

48 |

3.7% |

|

| Boys |

|

64 |

10.8% |

136 |

23.1% |

218 |

36.9% |

94 |

15.9% |

27 |

4.6% |

25 |

4.2% |

26 |

4.4% |

23.036 |

| Girls |

|

51 |

7.3% |

133 |

19.1% |

252 |

36.2% |

180 |

25.9% |

30 |

4.3% |

28 |

4.0% |

22 |

3.2% |

(<0.001) |

| Grade |

6th |

45 |

13.0% |

74 |

21.4% |

130 |

37.6% |

61 |

17.6% |

5 |

1.4% |

18 |

5.2% |

13 |

3.8% |

|

| 7th |

30 |

9.7% |

83 |

26.9% |

110 |

35.6% |

51 |

16.5% |

13 |

4.2% |

11 |

3.6% |

11 |

3.6% |

50.548 |

| 8th |

27 |

8.1% |

61 |

18.3% |

121 |

36.3% |

86 |

25.8% |

16 |

4.8% |

10 |

3.0% |

12 |

3.6% |

(<0.001) |

| 9th |

13 |

4.4% |

51 |

17.1% |

109 |

36.6% |

76 |

25.5% |

23 |

7.7% |

14 |

4.7% |

12 |

4.0% |

|

Table 5.

Perceived descriptive norms on VPA among Czech adolescents according to gender and school class grade.

Table 5.

Perceived descriptive norms on VPA among Czech adolescents according to gender and school class grade.

| |

|

Every day |

4 to 6 times a week |

3 to 2 times a week |

Once a week |

Once a month |

Less than once a month |

Never |

|

| χ2 |

| (p) |

| |

| |

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

| Total |

|

28 |

2.2% |

103 |

8.0% |

575 |

44.7% |

370 |

28.8% |

97 |

7.5% |

80 |

6.2% |

33 |

2.6% |

|

| Boys |

|

19 |

3.2% |

53 |

9.0% |

271 |

45.9% |

146 |

24.7% |

47 |

8.0% |

31 |

5.3% |

23 |

3.9% |

22.677 |

| Girls |

|

9 |

1.3% |

50 |

7.2% |

304 |

43.7% |

224 |

32.2% |

50 |

7.2% |

49 |

7.0% |

10 |

1.4% |

(<0.001) |

| Grade |

6th |

12 |

3.5% |

42 |

12.1% |

147 |

42.5% |

98 |

28.3% |

19 |

5.5% |

21 |

6.1% |

7 |

2.0% |

|

| 7th |

9 |

2.9% |

30 |

9.7% |

150 |

48.5% |

76 |

24.6% |

18 |

5.8% |

18 |

5.8% |

8 |

2.6% |

39.865 |

| 8th |

5 |

1.5% |

17 |

5.1% |

154 |

46.2% |

97 |

29.1% |

31 |

9.3% |

23 |

6.9% |

6 |

1.8% |

(0.002) |

| 9th |

2 |

0.7% |

14 |

4.7% |

124 |

41.6% |

99 |

33.2% |

29 |

9.7% |

18 |

6.0% |

12 |

4.0% |

|

Table 6.

Underestimation of norms in Vigorous Physical Activity (results of logistic regression).

Table 6.

Underestimation of norms in Vigorous Physical Activity (results of logistic regression).

| |

|

|

|

OR(95% C.I.) |

p |

| Model 1 |

Gender |

Boys |

|

ref. |

|

| Girls |

|

1.274(1.021 - 1.589) |

0.032 |

| Model 2 |

Gender |

Boys |

|

ref. |

|

| Girls |

|

1.273(1.020 - 1.590) |

0.033 |

| Grade |

6th |

|

ref. |

0.003 |

| 7th |

|

0.88(0.643 - 1.204) |

0.423 |

| 8th |

|

1.24(0.915 - 1.68) |

0.165 |

| 9th |

|

1.562(1.143 - 2.135) |

0.005 |

| Model 3 |

Gender |

Boys |

|

ref. |

|

| Girls |

|

1.274(1.020 - 1.592) |

0.033 |

| Grade |

6th |

|

ref. |

0.003 |

| 7th |

|

0.88(0.643 - 1.204) |

0.423 |

| 8th |

|

1.238(0.914 - 1.679) |

0.168 |

| 9th |

|

1.558(1.138 - 2.132) |

0.006 |

| School |

School |

|

0.997(0.968 - 1.027) |

0.850 |

| Model 4 |

Gender |

Boys |

|

ref. |

|

| Girls |

|

1.238(0.981 - 1.563) |

0.073 |

| Grade |

6th |

|

ref. |

0.056 |

| 7th |

|

0.885(0.639 - 1.227) |

0.464 |

| 8th |

|

1.161(0.846 - 1.593) |

0.357 |

| 9th |

|

1.387(0.998 - 1.927) |

0.051 |

| School |

|

|

0.999(0.968 - 1.03) |

0.941 |

| VPA |

Every day |

|

ref. |

0.000 |

| 4 to 6 times a week |

|

0.493(0.312 - 0.781) |

0.003 |

| 3 to 2 times a week |

|

0.862(0.568 - 1.309) |

0.487 |

| Once a week |

|

1.45(0.927 - 2.269) |

0.104 |

| Once a month |

|

4.521(2.148 - 9.518) |

0.000 |

| Less than once a month |

|

2.941(1.465 - 5.905) |

0.002 |

| Never |

|

3.134(1.513 - 6.489) |

0.002 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).