Submitted:

01 June 2023

Posted:

02 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

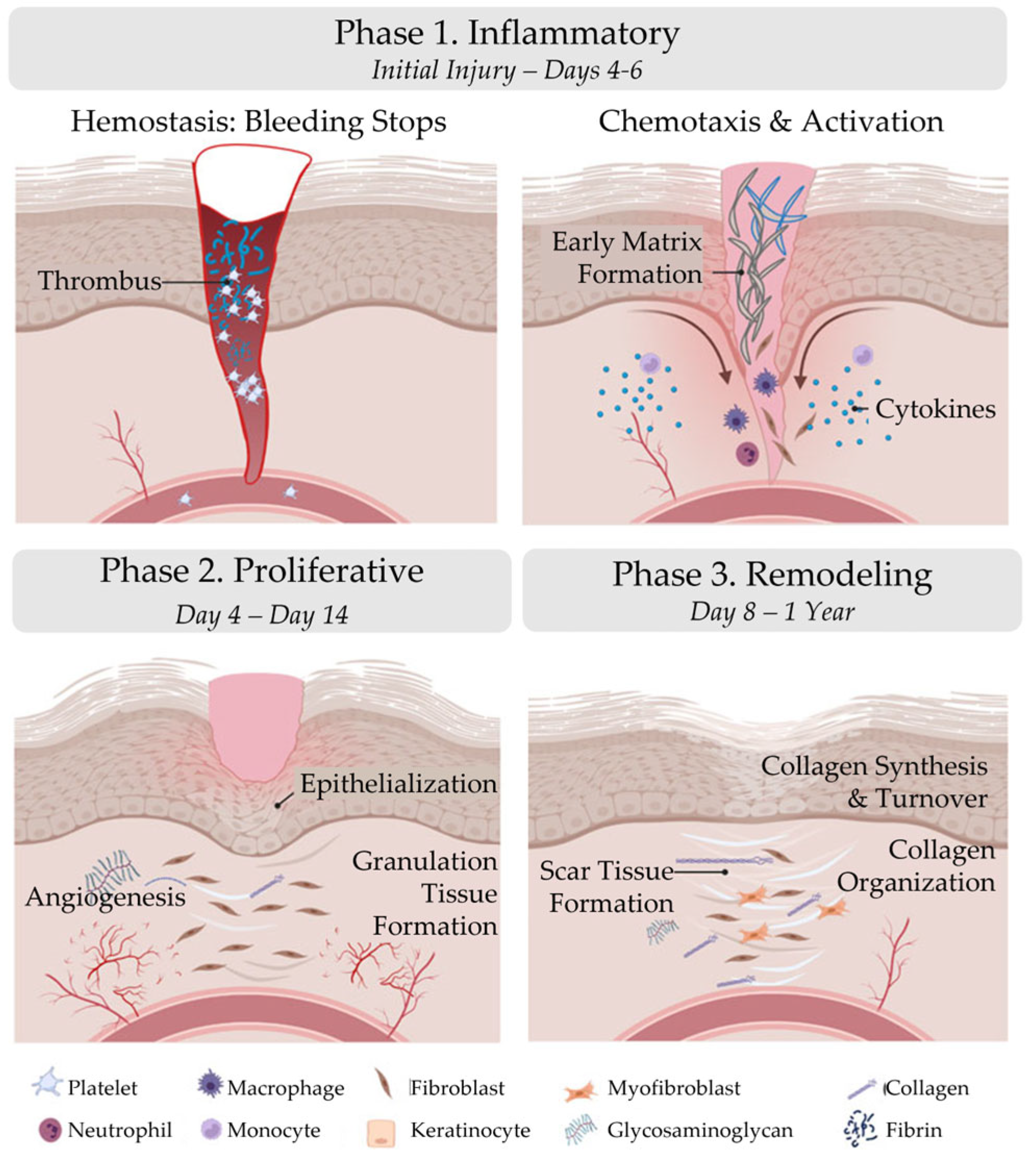

2. Overview of Wound Healing

2.1. Inflammatory Phase

2.2. Proliferative Phase

2.3. Remodeling Phase

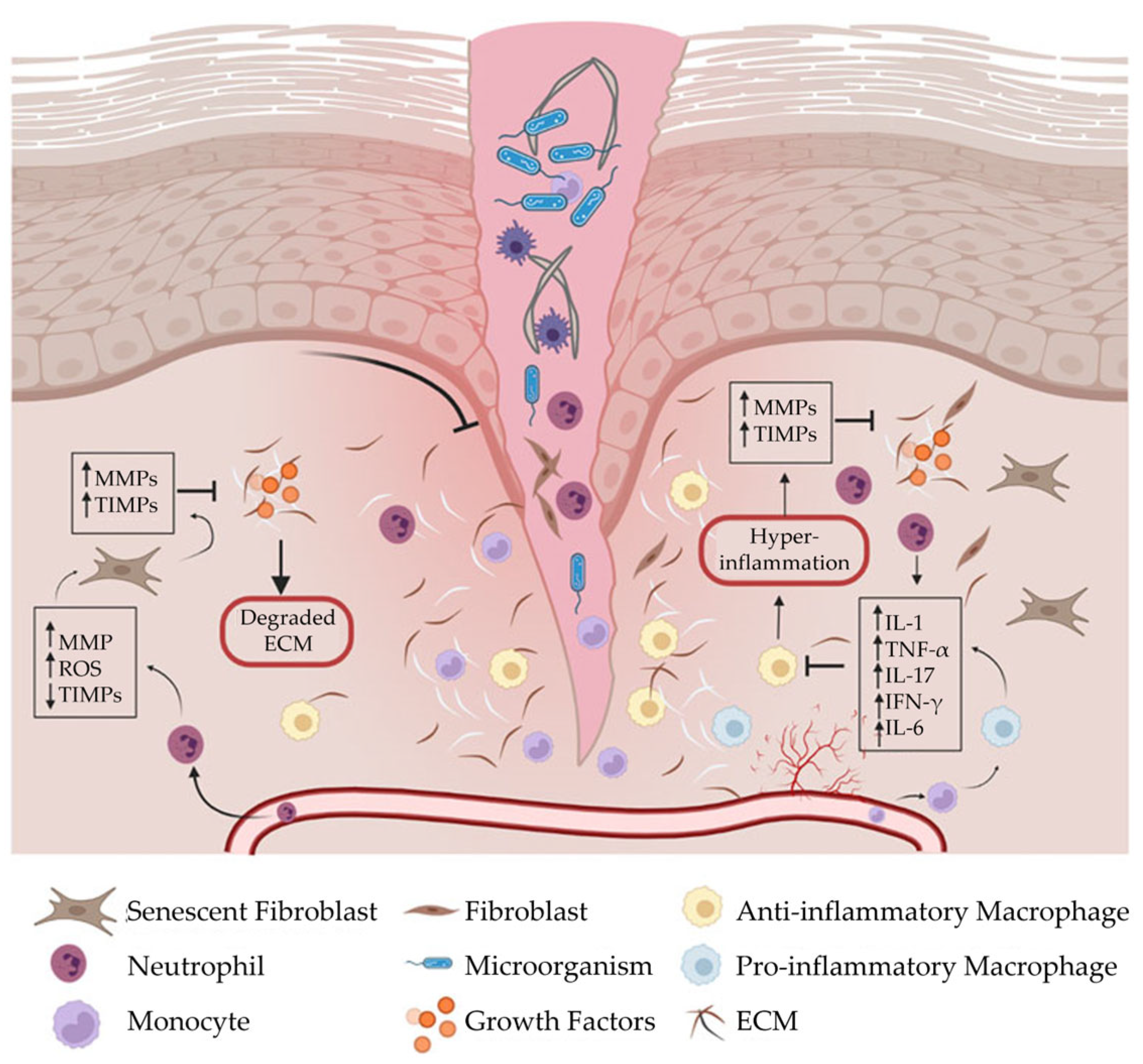

2.4. Wound Formation

- Elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines

- Dysfunctional macrophages

- Imbalanced proteolytic enzymes and protease inhibitors

- High concentrations of MMPs

- Abnormal ECM.

2.5. Factors That Impair Wound Healing

2.6. Economic Impact of Chronic Wounds

2.7. Treatment of Chronic Wounds

- Negative pressure wound therapy [37, 38];

- Hyperbaric oxygen therapy [39-42];

- Autologous platelet rich plasma [43, 44];

- Growth factors [45, 46];

- Cell therapy [47, 48];

- Scaffolds (e.g., autologous, biologic, synthetic) [49-52].

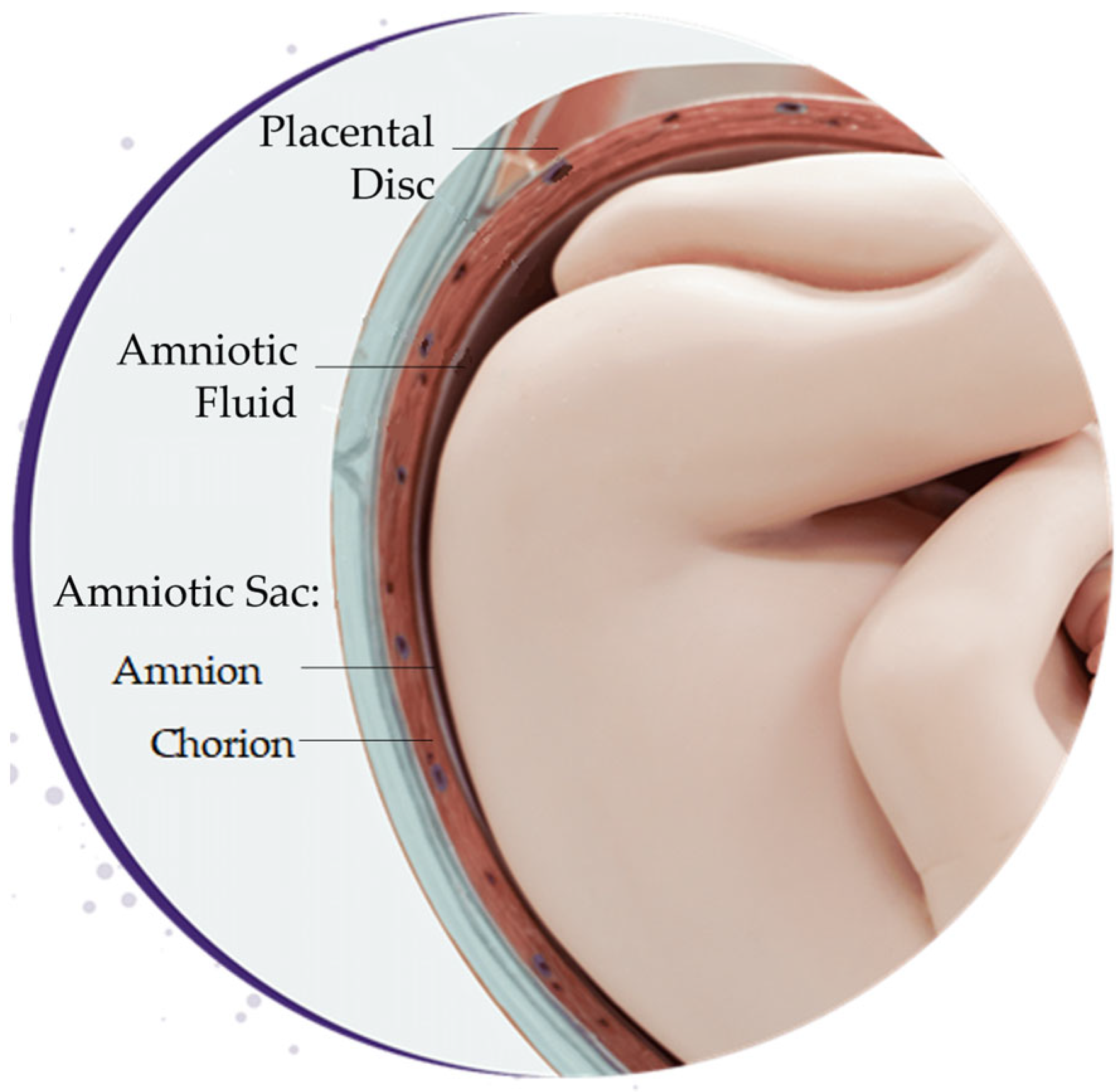

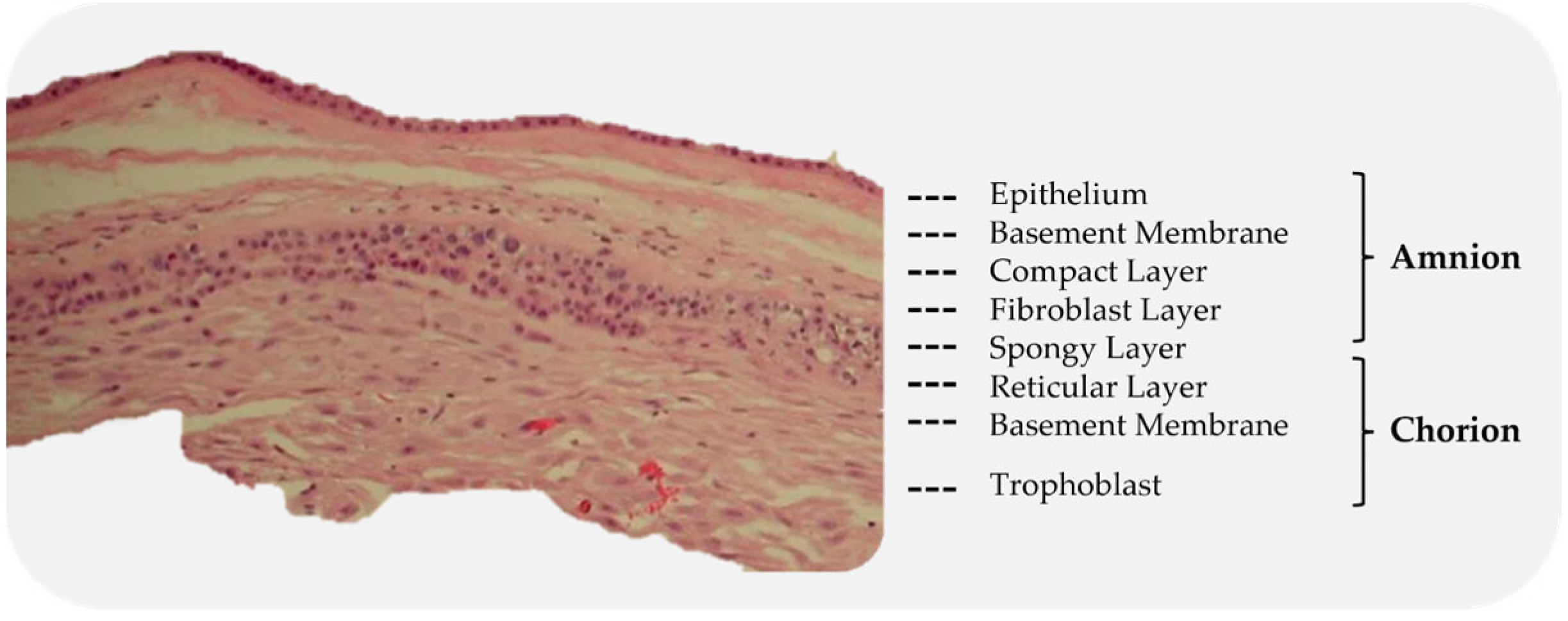

3. Placental-Derived Biomaterials

3.1. Source of Placental-Derived Biomaterials

3.1.1. Amniotic Fluid

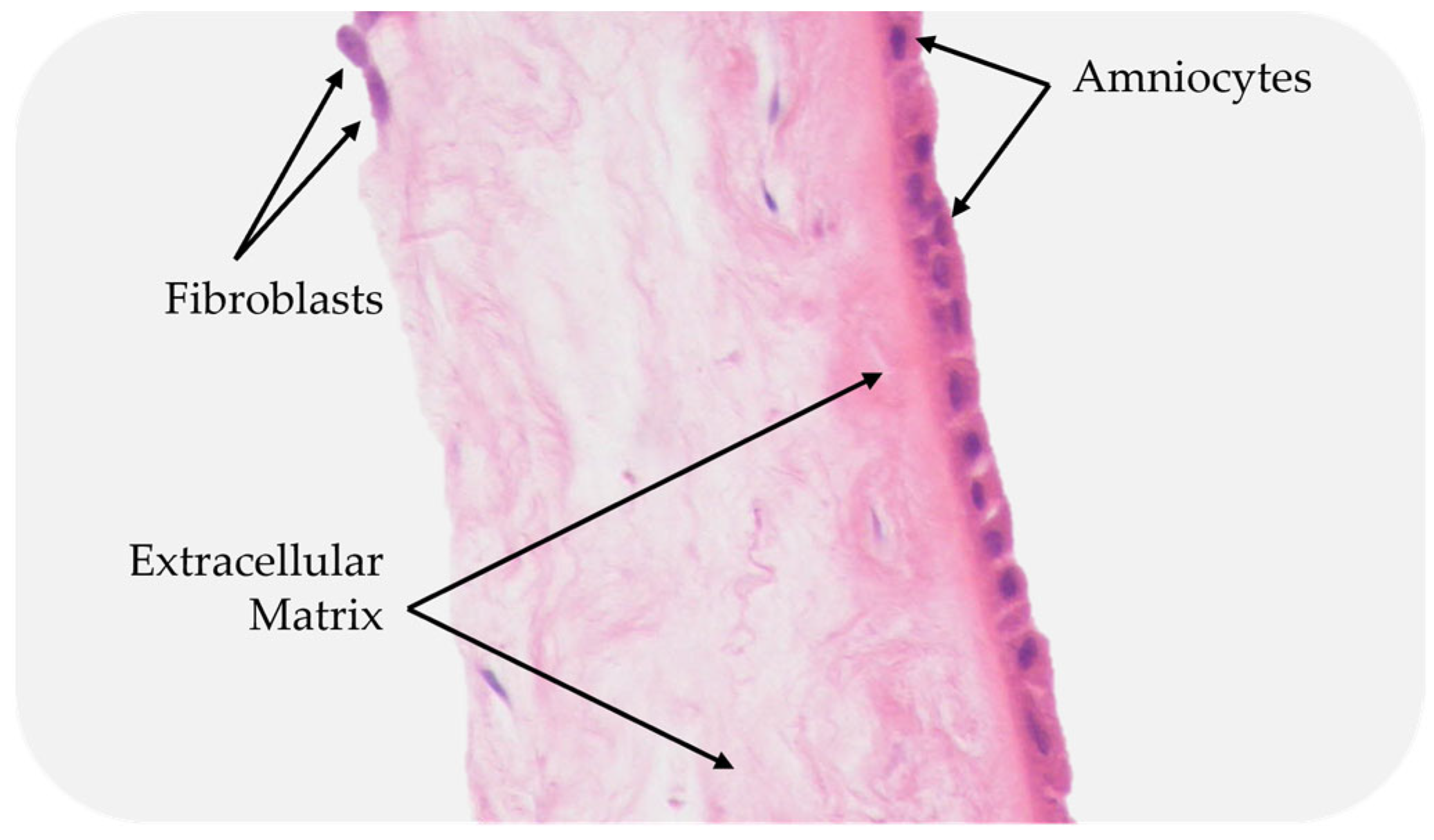

3.1.2. Amniotic Sac

3.1.3. Placental Disc

3.1.4. Umbilical Cord

3.2. Properties of Placental-Derived Biomaterials

3.3. Differences among Placental-Derived Biomaterials

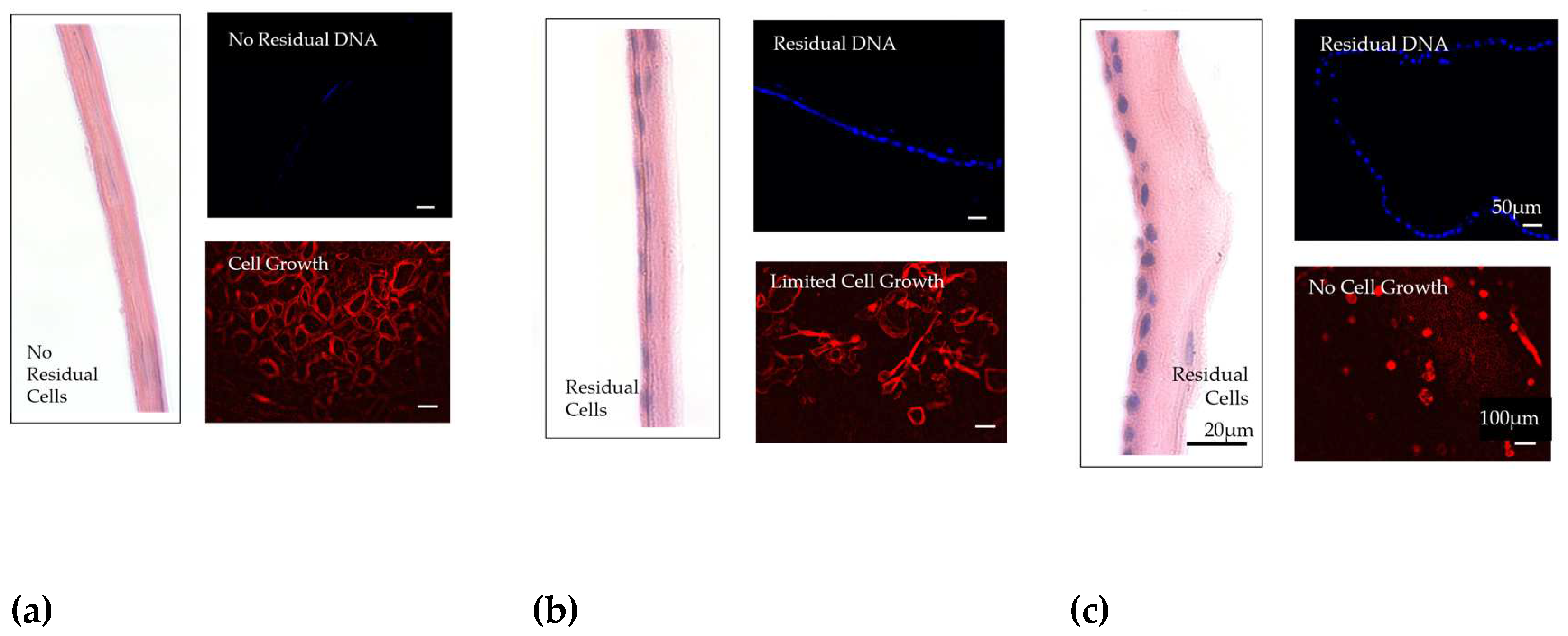

3.4. Preservation Method

3.5. Decellularization

3.6. Clinical Application

3.7. Commercial Products

4. Placental-Derived Biomaterials in Wound Healing: Clinical Results

4.1. Outcomes

| # | Company | Product | Source | Preservation Method | Decellularization Status | Unique Design Elements | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AlloSource | AlloWrap® DS | A | Dry; Proprietary Technology | Non-decellularized | Dual Layers, omnidirectional implantation | [156] |

| 2 | Amniox Medical, Inc. | Neox® 1K | UC | Cryopreservation; CryoTek® | Non-decellularized | ||

| 3 | Amniox Medical, Inc. | Neox® 100 | A | Cryopreservation; CryoTek® | Non-decellularized | ||

| 4 | Amniox Medical, Inc. | Neox® Cord RT | UC & A | Dehydration; SteriTek® | Non-decellularized | [129, 157, 158] | |

| 5 | Applied BiologicsTM | Xwrap® | A | Dehydration | Non-decellularized | Chorion free | |

| 6 | Celularity Inc. | Biovance® | A | Dehydration | Decellularized | Decellularized | [4, 31, 87, 119, 120, 159] |

| 7 | Celularity Inc. | Biovance3L® | A | Dehydration | Decellularized | Tri-layer | |

| 8 | Integra Life Sciences | AmnioExcel® | A | Dehydration | Non-decellularized | [7, 160-168] | |

| 9 | Integra LifeSciences | BioDFence® G3 | A & C | Proprietary method | Non-decellularized | Tri-layer (amnion-chorion-amnion) | |

| 10 | Integra LifeSciences | BioDDryFlex® | A | Dehydration | Non-decellularized | ||

| 11 | Integra LifeSciences | BioFix® | A | Dehydration | Decellularized | Omnidirectional placement | |

| 12 | Integra LifeSciences | BioFix® Plus | C | Dehydration; HydraTek® | Decellularized | Omnidirectional placement | |

| 13 | MiMedx Group, Inc. | EPIFIX® | A & C | Dehydration; HydraTek® | Non-decellularized | Retains cytokines & growth factors | [118, 169] |

| 14 | MiMedx Group, Inc. | EPICORD® | UC | Dehydration; PURION® | Non-decellularized | Expandable | [118, 169] |

| 15 | MiMedx Group, Inc. | AMNIOCORD® | UC | Dehydration; PURION® | Non-decellularized | 250+ Regulatory Proteins | [170] |

| 16 | MiMedx Group, Inc. | AMNIOEFFECT® | A, IL & C | Dehydration; PURION® | Non-decellularized | 300+ regulatory proteins | |

| 17 | MiMedx Group, Inc. | AmnioFix® | A & C | Lyophilization; PURION® | Non-decellularized | 300+ regulatory proteins | [118, 169] |

| 18 | MTF Biologics | AmnioBand | PT | Dehydration; PURION® | Non-decellularized | ||

| 19 | Organogenesis | Affinity® | A | Dehydration; Proprietary aseptic method | Non-decellularized | Fresh allograft derived from amnion tissue | [145, 171] |

| 20 | Organogenesis | NuShield® | A & C | Hypothermically stored | Non-decellularized | LayerLoc™ preserves spongy layer | [123, 172-174] |

| 21 | Skye Biologics, Inc., | WoundEx®45 | A | Dehydration; LayerLoc™ | Non-decellularized | Thin | |

| 22 | Skye Biologics, Inc., | WoundEx®200 | C | Dehydration | Non-decellularized | Thick | |

| 23 | Skye Biologics, Inc., | WoundFix™ | A | Dehydration | Non-decellularized | ||

| 24 | Smith & Nephew | GRAFIX® PL | A & C | Dehydration | Non-decellularized | Retains native cells and growth factors | |

| 25 | Smith & Nephew | GRAFIX® | A & C | Lyopreservation | Non-decellularized | Retains native cells and growth factors | [151, 175, 176] |

| 26 | Smith & Nephew | STRAVIX® PL | UC | Cryopreservation | Non-decellularized | ||

| 27 | Smith & Nephew | STRAVIX® | UC | Lyopreservation | Non-decellularized | [177] | |

| 28 | StimLabs, LLC | Revita® | A, IL & C | Cryopreservation | Non-decellularized | ||

| 29 | StimLabs, LLC | Cogenex® | A, IL & C | Dehydration; Clearify™ | Non-decellularized | Fenestrated | |

| 30 | StimLabs, LLC | Enverse® | A, IL & C | Dehydration | Non-decellularized | Translucent | |

| 31 | StimLabs, LLC | Vialize® | A, IL & C | Clearify™ | Non-decellularized | Lyophilized | |

| 32 | Tides Medical | Artacent® Wound | A | Dehydration; Clearify™ | Non-decellularized | Dual layer | |

| 33 | Ventris Medical | CellestaTM | A | Dehydration; Clearify™ | Non-decellularized | Poly mesh backing | |

| 34 | Vivex | CYGNUS® Solo | A | Dehydration | Non-decellularized | Single Layer | |

| 35 | Vivex | CYGNUS® Matrix | A & C | Artacleanse® | Non-decellularized | ||

| 36 | Vivex | CYGNUS® Max | UC | Clearant™ | Non-decellularized | ||

| 37 | Vivex | CYGNUS® Max XL | UC | Dehydrated; INTEGRITY PROCESSING™ | Non-decellularized | Fenestrated |

| # | Company | Product | Source | Preservation Method | Decellularization Status | Unique Design Elements | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AediCell | Dermavest®/ Plurivest® | PD, A, C & UC | Dehydration | Decellularized | ||

| 2 | Applied Biologics™ | FLŌGRAFT® | AF | Cryopreservation | Non-decellularized | ||

| 3 | Celularity Inc. | Interfyl® | C | Dehydration | Decellularized | Decellularized | [137] |

| 4 | Integra LifeSciences | AmnioMatrix® | A & AF | Cryopreservation | Non-decellularized | ||

| 5 | Integra LifeSciences | BioDFactor® | A & AF | Cryopreservation | Non-decellularized | ||

| 6 | Integra LifeSciences | BioFix® Flo | PT | Dehydration; HydraTek® | Decellularized | ||

| 7 | MiMedx Group, Inc. | AmnioFill® | A & C | Dehydration; Purion® | Non-decellularized | 300+ regulatory proteins | [118] |

| 8 | MiMedx Group, Inc. | AxioFillTM | PD | Dehydrated; Purion® | Decellularized | ||

| 9 | Skye Biologics, Inc. | BioRenewTM | PT | Cryopreservation | Non-decellularized | Growth factors | [136] |

| 10 | Skye Biologics, Inc. | WoundEx®Flow | PT | Dehydration | Non-decellularized | ||

| 11 | Ventris Medical | CellestaTM Flowable | A | Clearant™ | Non-decellularized |

| # | Study Details | Purpose | Results Summary | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Study: Mohammadi Tofigh et al. 2022 [154] Study Design: Prospective, Single Center Wound Type: DFU Placental-derived Biomaterial: dAP (AMOR) Patients: 243 (81 dAP, 81 PDGF gel, 81 debridement) |

To compare the therapeutic effects of the three methods of diabetic wound care: surgical debridement and dressing, dressing with dAP, and dressing with PDGF gel | Percent area reduction was significantly different between dehydrated amnion, PDGF gel, and debridement at 4 weeks (49.3 vs 14.8 vs 7.4%), 6 weeks (79 vs 35.8 vs 20.1%), 8 weeks (86.4 vs 56.8 vs 43.7%), weeks 10 and 12 (87.6 vs 61.7 vs 50%) Similar safety profiles between groups |

Shows improved healing with application of dehydrated amnion powder in DFU patients, compared with platelet-derived growth factor dressing and surgical debridement |

| 2 | Study: Serena et al. 2022 [144] Study Design: Prospective, Multicenter Wound Type: VLU Placental-derived Biomaterial: dHACA (AmnioBand®) Patients: 60 (40 dHACA, 20 SOC) |

To evaluate the safety and effectiveness of weekly and biweekly applications of dHACA plus SOC compared to SOC alone on chronic VLUs | Significantly higher proportion of healed VLUs in the two dHACA groups than SOC (75% vs 30%) No significant differences in the proportion of ulcers achieving 40% closure at 4 weeks AE Rate: 63.5%; no graft or procedure related AEs |

Shows dHACA and SOC, either applied weekly or biweekly, healed significantly more VLUs than SOC alone, suggesting that the use of aseptically processed dHACA is a safe and effective treatment option in the healing of chronic VLUs |

| 3 | Study: Game et al. 2021 [155] Study Design: Prospective, Multicenter Wound Type: DFU Placental-derived Biomaterial: dHAM® (Omnigen) Patients: 31 (15 dHAM, 16 SOC) |

To investigate whether 2 weekly additions of the dHAM to standard care versus standard care alone increased the proportion of healed participants' DFUs within 12 weeks | Similar proportion of healed DFUs for dHAM and SOC (27 vs 6.3%) Percent wound area reduction was significantly higher in the dHAM group No difference in AEs |

Shows dHAM preparation is safe treatment for DFUs |

| 4 | Study: Carter, 2020 [178] Study Design: Health Economics Study Wound Type: DFU Placental-derived Biomaterial: dHACA (AmnioBand®) Patients: 80 (40 dHACA, 40 SOC) |

To estimate the cost-utility of an aseptically processed dHACA plus SOC versus SOC alone based on a published randomized controlled trial in which patients who had an eligible Wagner 1 DFU wound were randomized to either of these treatments | ICER at 1 year for group 1 versus group 2 was -$4,373 Group 1 had 69.2% lower cost values with increased positive incremental effectiveness for 94.9% of values A willingness to pay curve showed that about 92% of interventions were cost effective for group 1 when $50,000 was paid |

Demonstrates dHACA added to SOC compared to SOC alone is a cost-effective treatment for DFUs |

| 5 | Study: Serena et al. 2020 [145] Study Design: Prospective, Multicenter Wound Type: DFU Placental-derived Biomaterial: HSAM (Affinity®) Patients: 76 (38 HSAM, 38 SOC) |

To determine the effectiveness of HSAM versus SOC in DFUs | Proportion of wound closure for HSAM was significantly greater at 12 (55 vs 29%) and 16 (58 vs 29%) weeks Incidence of ulcers achieving >60% reductions in area and depth was significantly greater for HSAM (area: 82 vs 58%; depth: 65 vs 39%) |

Demonstrates an increased frequency and probability of wound closure in DFUs with HSAM versus SOC |

| 6 | Study: Tettelbach et al. 2019 [124] Study Design: Prospective, Multicenter Wound Type: DFU Placental-derived Biomaterial: dHACM (EpiFix®) Patients: 110 ITT (54 dHACM, 56 SOC); 98 PP (47 dHACM, 51 SOC) |

To confirm the efficacy of dHACM for the treatment of chronic lower extremity ulcers in persons with diabetes | Significantly higher proportion of complete wound closure in 12 weeks for dHACM (ITT: 70 vs 50%; PP: 81 vs 55%) A Kaplan-Meier analysis showed a significantly improved time to healing with dHACM Higher proportion of wound remained closed at 16 weeks for dHACM (95 vs 86%) 230 AEs; 3 possibly product-related |

Confirms dHACM is an efficacious treatment for lower extremity DFUs |

| 7 | Study: Bianchi et al. 2019 [146] Study Design: Prospective, Multicenter Wound Type: VLU Placental-derived Biomaterial: dHACM (EpiFix®) Patients: 128 (64 dHACM, 64 Control) |

To report ITT results and assess if both ITT and PP data analyses arrive at the same conclusion of the efficacy of dHACM as a treatment for VLU | Kaplan-Meier plot of time to heal showed a superior wound healing trajectory for dHACM in both ITT and PP Proportion of healed ulcers was significantly greater for dHACM (ITT: 50 vs 31%; PP: 60 vs 35%) 65 AEs; none related to dHACM or study procedures |

Provides an additional level of assurance regarding the effectiveness of dHACM |

| 8 | Study: Tettelbach et al. 2019 [126] Study Design: Prospective, Multicenter Wound Type: DFU Placental-derived Biomaterial: dHUC (EpiCord®) Patients: 155 (101 dHUC, 54 Alginate); 134 PP (86 dHUC; 48 Alginate); 107 AD (67 dHUC; 40 Alginate) |

To determine the safety and effectiveness of dHUC allograft compared with alginate wound dressings for the treatment of chronic, non-healing DFUs | Proportion of patients with complete wound closure at 12 weeks was significantly greater for dHUC (70 vs 48%) Proportion of AD patients with complete wound closure at 12 weeks was significantly greater for dHUC (96 vs 65%) Rate of healing at 12 weeks in PP patients was significantly greater for dHUC (81 vs 54%) 160 AEs; none related to dHUC or alginate dressing |

Demonstrates the safety and efficacy of dHUC as a treatment for non-healing DFUs |

| 9 | Study: DiDomenico et al. 2018 [147] Study Design: Prospective, Multicenter Wound Type: DFU Placental-derived Biomaterial: dHACA (AmnioBand®) Patients: 80 (40 dHACA, 40 SOC) |

To compare dHACA with SOC in achieving wound closure in non-healing DFUs | Higher proportion of healed DFUs at 12 weeks for dHACA (85 vs 33%) Significantly faster mean time to heal for dHACA (37 vs 67 days) Mean number of grafts used per healed DFU was 4.0 Mean graft cost per healed DFU was $1,771 11 AEs; None dHACA related |

Shows aseptically processed dHACA heals DFUs significantly faster than SOC at 12 weeks |

| 10 | Study: Bianchi et al. 2018 [121] Study Design: Prospective, Multicenter Wound Type: VLU Placental-derived Biomaterial: dHACM (EpiFix®) Patients: 109 (52 dHACM, 57 Control) |

To evaluate the efficacy of dHACM as an adjunct to multilayer compression therapy for the treatment of non-healing full-thickness VLUs | Kaplan-Meier plot of time to heal showed a superior wound healing trajectory for dHACM Proportion of healed ulcers was significantly greater for dHACM at 12 weeks (60 vs 35%) and 16 weeks (71 vs 44%) 65 AEs; none related to dHACM or study procedures |

Confirms dHACM as an adjunct to multilayer compression therapy for the treatment of non-healing, full-thickness VLUs |

| 11 | Study: Zelen et al. 2016 [150] Study Design: Prospective, Multicenter Wound Type: DFU Placental-derived Biomaterial: dHACM (EpiFix®) Patients: 100 (33 Apligraf, 32 dHACM, 35 SOC) |

To compare clinical outcomes at 12 weeks in 100 patients with chronic lower extremity DFUs treated with weekly applications of Apligraf®, dHACM, or SOC with collagen-alginate dressing as controls | Significantly higher proportion of healed ulcers for dHACM versus Apligraft versus SOC (97 vs 73 vs 51%) Significantly faster time to healing for dHACM versus Apligraft versus SOC (23.6 vs 47.9 vs 57.4 days) Median number of grafts per healed wound was significantly lower for dHACM (2.5 vs 6) Median graft cost per healed wound was significantly lower for dHACM ($1,517 vs $8,918) 10 AEs; none dHACM related |

Provides further evidence of the clinical and resource utilization superiority of dHACM for the treatment of lower extremity DFUs |

| 12 | Study: Zelen et al. 2015 [149] Study Design: Prospective, Multicenter Wound Type: DFU Placental-derived Biomaterial: dHACM (EpiFix®) Patients: 60 (20 Apligraf, 20 dHACM, 20 SOC) |

To compare the healing effectiveness of treatment of chronic lower extremity diabetic ulcers with either weekly applications of Apligraf®, dHACM, or SOC with collagen-alginate dressing | Significantly higher proportion of complete wound closure for dHACM versus Apligraf and SOC at 4 weeks (85 vs 35 and 30%) and 6 weeks (95 vs 45 and 35%) At each week 1-6, mean percent wound size reduction was greatest for dHACM Significantly faster median time to healing for dHACM versus Apligraf and SOC (13 vs 49 and 49 days) Significantly fewer grafts for dHACM (2.15 vs 6.2) Significantly lower graft cost per patient for dHACM ($1,669 vs $9,216) 5 AEs; none related to treatment |

Demonstrates superior clinical and resource utilisation for dHACM compared with Apligraf and SOC for the treatment of DFUs |

| 13 | Study: Serena et al. 2015 [179] Study Design: Retrospective, Multicenter Wound Type: VLU Placental-derived Biomaterial: dHACM (EpiFix®) Patients: 44 (20 ≥40%, 24 <40%) |

To evaluate correct correlation between an intermediate rate of wound reduction (40% wound area reduction after 4-weeks of treatment) and complete healing at 24 weeks in patients with a VLU | Complete healing occurred in 16/20 of the ≥40% group at a mean of 46 days 8/24 of the <40% group at a mean of 103.6 days Correct correlation of status at 4 weeks and ultimate healing status of VLU occurred in 32/44 patients (73%) |

Confirms the intermediate outcome is a viable predictor of VLU healing |

| 14 | Study: Serena et al. 2014 [152] Study Design: Prospective, Multicenter Wound Type: VLU Placental-derived Biomaterial: dHACM (EpiFix®) Patients: 84 (53 dHACM, 31 Control) |

To evaluate the safety and efficacy of one or two applications of dHACM and multilayer compression therapy versus multilayer compression therapy alone in the treatment of VLUs | Proportion of patients achieving >40% wound closure at 4 weeks was significantly greater for dHACM (62 vs 32%). Significant reduction in mean ulcer size for dHACM (48 vs 19%) 14 AEs (9 dHACM, 5 Control) |

Shows dHACM significantly improved VLU healing at 4 weeks |

| 15 | Study: Zelen et al. 2014 [148] Study Design: Prospective, Single-Center Wound Type: DFU Placental-derived Biomaterial: dHACM (EpiFix®) Patients: 40 (20 weekly, 20 bi-weekly) |

To determine if weekly application of dHACM allograft reduce time to heal more effectively than biweekly application for treatment of DFUs | Significantly shorter mean time to complete healing in the weekly application group (2.4 ± 1.8 vs 4.1 ± 2.9 weeks) Proportion of completely healed wounds at 4 weeks was significantly greater in the weekly application group (90% vs 50%) Similar number of grafts applied to healed wounds (weekly: 2.3 ± 1.8; biweekly: 2.4 ± 1.5) 8 AEs; none attributed to dHACM |

Shows dHACM is an effective treatment for DFUs, and DFUs heal more rapidly with weekly application |

| 16 | Study: Lavery et al. 2014 [151] Study Design: Prospective, Multicenter Wound Type: DFU Placental-derived Biomaterial: hVWM (Grafix®) Patients: 97 (50 hVWM, 47 Control) |

To compare the efficacy of a hVWM with standard wound care to heal DFUs | Proportion of patients with complete wound closure at 12 weeks was significantly greater for hVWM (62 vs 21%) Significantly shorter median time to healing for hVWM (42 vs 69.5 days) Significantly fewer AEs for hVWM (44 vs 66%) Significantly fewer wound-related infections for hVWM (18 vs 36%) Similar proportion of wounds remained closed in crossover phase (hVWM: 82%; Control: 70%) |

Shows that hVWM is a safe and effective therapy for treating DFUs |

| 17 | Study: Zelen et al. 2013 [153] Study Design: Prospective, Single-Center Wound Type: DFU Placental-derived Biomaterial: dHACM (EpiFix®) Patients: 25 (13 dHACM, 12 SOC) |

To compare healing characteristics of DFUs treated with dHACM versus standard of care | Reductions in wound size were significantly greater for dHACM at 4 weeks (97 vs 32%) and 6 weeks (98 vs -2%) Healing rates were significantly higher for dHACM at 4 weeks (77 vs 0%) and 6 weeks (92 vs 8%) 5 AEs; none dHACM related |

Shows dHACM in addition to the SOC is efficacious for wound healing |

4.2. Safety

5. Discussion

6. Next Steps

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sindrilaru A., Peters T., Wieschalka S., Baican C., Baican A., Peter H., Hainzl A., Schatz S., Qi Y., Schlecht A., Weiss J.M., Wlaschek M., Sunderkötter C., Scharffetter-Kochanek K. An unrestrained proinflammatory m1 macrophage population induced by iron impairs wound healing in humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:985-997. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci44490. [CrossRef]

- Choi J.S., Kim J.D., Yoon H.S., Cho Y.W. Full-thickness skin wound healing using human placenta-derived extracellular matrix containing bioactive molecules. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19:329-339. https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.TEA.2011.0738. [CrossRef]

- Niknejad H., Peirovi H., Jorjani M., Ahmadiani A., Ghanavi J., Seifalian A.M. Properties of the amniotic membrane for potential use in tissue engineering. Eur Cell Mater. 2008;15:88-99. https://doi.org/10.22203/ecm.v015a07. [CrossRef]

- Gleason J., Guo X., Protzman N.M., Mao Y., Kuehn A., Sivalenka R., Gosiewska A., Hariri R., Brigido S.A. Decellularized and dehydrated human amniotic membrane in wound management: Modulation of macrophage differentiation and activation. J Biotechnol Biomater. 2022;12:1000288. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-952X.1000289. [CrossRef]

- Mao Y., John N., Protzman N.M., Kuehn A., Long D., Sivalenka R., Junka R.A., Gosiewska A., Hariri R.J., Brigido S.A. A decellularized flowable placental connective tissue matrix supports cellular functions of human tenocytes in vitro. J Exp Orthop. 2022;9:69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40634-022-00509-4. [CrossRef]

- Mao Y., Protzman N.M., John N., Kuehn A., Long D., Sivalenka R., Junka R.A., Shah A.U., Gosiewska A., Hariri R.J., Brigido S.A. An in vitro comparison of human corneal epithelial cell activity and inflammatory response on differently designed ocular amniotic membranes and a clinical case study. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.35186. [CrossRef]

- Thompson P., Hanson D.S., Langemo D., Anderson J. Comparing human amniotic allograft and standard wound care when using total contact casting in the treatment of patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2019;32:272-277. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.Asw.0000557831.78645.85. [CrossRef]

- Broughton G., 2nd, Janis J.E., Attinger C.E. Wound healing: An overview. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:1e-S-32e-S. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000222562.60260.f9. [CrossRef]

- Solarte David V.A., Guiza-Arguello V.R., Arango-Rodriguez M.L., Sossa C.L., Becerra-Bayona S.M. Decellularized tissues for wound healing: Towards closing the gap between scaffold design and effective extracellular matrix remodeling. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:821852. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2022.821852. [CrossRef]

- Ozgok Kangal M.K., Regan J.P. Wound healing. In: Statpearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2022.

- Wynn T.A., Chawla A., Pollard J.W. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2013;496:445-455. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12034. [CrossRef]

- Porcheray F., Viaud S., Rimaniol A.C., Leone C., Samah B., Dereuddre-Bosquet N., Dormont D., Gras G. Macrophage activation switching: An asset for the resolution of inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;142:481-489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02934.x. [CrossRef]

- Stout R.D., Suttles J. Immunosenescence and macrophage functional plasticity: Dysregulation of macrophage function by age-associated microenvironmental changes. Immunol Rev. 2005;205:60-71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00260.x. [CrossRef]

- Stout R.D., Jiang C., Matta B., Tietzel I., Watkins S.K., Suttles J. Macrophages sequentially change their functional phenotype in response to changes in microenvironmental influences. J Immunol. 2005;175:342-349. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.342. [CrossRef]

- Arnold L., Henry A., Poron F., Baba-Amer Y., van Rooijen N., Plonquet A., Gherardi R.K., Chazaud B. Inflammatory monocytes recruited after skeletal muscle injury switch into antiinflammatory macrophages to support myogenesis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1057-1069. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20070075. [CrossRef]

- Spiller K.L., Koh T.J. Macrophage-based therapeutic strategies in regenerative medicine. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;122:74-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2017.05.010. [CrossRef]

- O'Brien E.M., Risser G.E., Spiller K.L. Sequential drug delivery to modulate macrophage behavior and enhance implant integration. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;149-150:85-94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2019.05.005. [CrossRef]

- Reinke J.M., Sorg H. Wound repair and regeneration. Eur Surg Res. 2012;49:35-43. https://doi.org/10.1159/000339613. [CrossRef]

- Demidova-Rice T.N., Hamblin M.R., Herman I.M. Acute and impaired wound healing: Pathophysiology and current methods for drug delivery, part 1: Normal and chronic wounds: Biology, causes, and approaches to care. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2012;25:304-314. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ASW.0000416006.55218.d0. [CrossRef]

- Bowers S., Franco E. Chronic wounds: Evaluation and management. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101:159-166.

- Mustoe T.A., O'Shaughnessy K., Kloeters O. Chronic wound pathogenesis and current treatment strategies: A unifying hypothesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:35s-41s. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000225431.63010.1b. [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum S.R., Carter M.J., Fife C.E., DaVanzo J., Haught R., Nusgart M., Cartwright D. An economic evaluation of the impact, cost, and medicare policy implications of chronic nonhealing wounds. Value Health. 2018;21:27-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2017.07.007. [CrossRef]

- Guo S., Dipietro L.A. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res. 2010;89:219-229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034509359125. [CrossRef]

- Anderson K., Hamm R.L. Factors that impair wound healing. J Am Coll Clin Wound Spec. 2012;4:84-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jccw.2014.03.001. [CrossRef]

- Heyer K., Herberger K., Protz K., Glaeske G., Augustin M. Epidemiology of chronic wounds in germany: Analysis of statutory health insurance data. Wound Repair Regen. 2016;24:434-442. https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.12387. [CrossRef]

- Guest J.F., Ayoub N., McIlwraith T., Uchegbu I., Gerrish A., Weidlich D., Vowden K., Vowden P. Health economic burden that wounds impose on the national health service in the uk. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e009283. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009283. [CrossRef]

- Sun H., Saeedi P., Karuranga S., Pinkepank M., Ogurtsova K., Duncan B.B., Stein C., Basit A., Chan J.C.N., Mbanya J.C., Pavkov M.E., Ramachandaran A., Wild S.H., James S., Herman W.H., Zhang P., Bommer C., Kuo S., Boyko E.J., Magliano D.J. Idf diabetes atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119. [CrossRef]

- Ogurtsova K., da Rocha Fernandes J.D., Huang Y., Linnenkamp U., Guariguata L., Cho N.H., Cavan D., Shaw J.E., Makaroff L.E. Idf diabetes atlas: Global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;128:40-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2017.03.024. [CrossRef]

- Hossain P., Kawar B., El Nahas M. Obesity and diabetes in the developing world--a growing challenge. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:213-215. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp068177. [CrossRef]

- Järbrink K., Ni G., Sönnergren H., Schmidtchen A., Pang C., Bajpai R., Car J. The humanistic and economic burden of chronic wounds: A protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2017;6:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0400-8. [CrossRef]

- Guo X., Kaplunovsky A., Zaka R., Wang C., Rana H., Turner J., Ye Q., Djuretic I., Gleason J., Jankovic V., Smiell J.M., Bhatia M., Hofgartner W., Hariri R. Modulation of cell attachment, proliferation, and angiogenesis by decellularized, dehydrated human amniotic membrane in in vitro models. Wounds. 2017;29:28-38.

- O'Meara S., Cullum N.A., Nelson E.A. Compression for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:Cd000265. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000265.pub2. [CrossRef]

- Lavery L.A., Higgins K.R., La Fontaine J., Zamorano R.G., Constantinides G.P., Kim P.J. Randomised clinical trial to compare total contact casts, healing sandals and a shear-reducing removable boot to heal diabetic foot ulcers. Int Wound J. 2015;12:710-715. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12213. [CrossRef]

- Lewis J., Lipp A. Pressure-relieving interventions for treating diabetic foot ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:Cd002302. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002302.pub2. [CrossRef]

- Kottner J., Haesler E. The dissemination of the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers clinical practice guideline 2014 in the academic literature. Wound Repair Regen. 2020;28:580-583. https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.12823. [CrossRef]

- Gould L., Stuntz M., Giovannelli M., Ahmad A., Aslam R., Mullen-Fortino M., Whitney J.D., Calhoun J., Kirsner R.S., Gordillo G.M. Wound healing society 2015 update on guidelines for pressure ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2016;24:145-162. https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.12396. [CrossRef]

- Liu X., Zhang H., Cen S., Huang F. Negative pressure wound therapy versus conventional wound dressings in treatment of open fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2018;53:72-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.02.064. [CrossRef]

- Chen L., Zhang S., Da J., Wu W., Ma F., Tang C., Li G., Zhong D., Liao B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and safety of negative pressure wound therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcer. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:10830-10839. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-2476. [CrossRef]

- Andrade S.M., Santos I.C. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for wound care. Rev Gaucha Enferm. 2016;37:e59257. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-1447.2016.02.59257. [CrossRef]

- Nik Hisamuddin N.A.R., Wan Mohd Zahiruddin W.N., Mohd Yazid B., Rahmah S. Use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (hbot) in chronic diabetic wound - a randomised trial. Med J Malaysia. 2019;74:418-424.

- Thistlethwaite K.R., Finlayson K.J., Cooper P.D., Brown B., Bennett M.H., Kay G., O'Reilly M.T., Edwards H.E. The effectiveness of hyperbaric oxygen therapy for healing chronic venous leg ulcers: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Wound Repair Regen. 2018;26:324-331. https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.12657. [CrossRef]

- Salama S.E., Eldeeb A.E., Elbarbary A.H., Abdelghany S.E. Adjuvant hyperbaric oxygen therapy enhances healing of nonischemic diabetic foot ulcers compared with standard wound care alone. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2019;18:75-80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534734619829939. [CrossRef]

- Qu W., Wang Z., Hunt C., Morrow A.S., Urtecho M., Amin M., Shah S., Hasan B., Abd-Rabu R., Ashmore Z., Kubrova E., Prokop L.J., Murad M.H. The effectiveness and safety of platelet-rich plasma for chronic wounds: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96:2407-2417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.01.030. [CrossRef]

- Qu S., Hu Z., Zhang Y., Wang P., Li S., Huang S., Dong Y., Xu H., Rong Y., Zhu W., Tang B., Zhu J. Clinical studies on platelet-rich plasma therapy for chronic cutaneous ulcers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2022;11:56-69. https://doi.org/10.1089/wound.2020.1186. [CrossRef]

- Lee Y., Lee M.H., Phillips S.A., Stacey M.C. Growth factors for treating chronic venous leg ulcers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Wound Repair Regen. 2022;30:117-125. https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.12982. [CrossRef]

- Brown G.L., Nanney L.B., Griffen J., Cramer A.B., Yancey J.M., Curtsinger L.J., 3rd, Holtzin L., Schultz G.S., Jurkiewicz M.J., Lynch J.B. Enhancement of wound healing by topical treatment with epidermal growth factor. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:76-79. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm198907133210203. [CrossRef]

- Dong Y., Yang Q., Sun X. Comprehensive analysis of cell therapy on chronic skin wound healing: A meta-analysis. Hum Gene Ther. 2021;32:787-795. https://doi.org/10.1089/hum.2020.275. [CrossRef]

- Pichlsberger M., Jerman U.D., Obradović H., Tratnjek L., Macedo A.S., Mendes F., Fonte P., Hoegler A., Sundl M., Fuchs J., Schoeberlein A., Kreft M.E., Mojsilović S., Lang-Olip I. Systematic review of the application of perinatal derivatives in animal models on cutaneous wound healing. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;9:742858. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2021.742858. [CrossRef]

- Jones J.E., Nelson E.A., Al-Hity A. Skin grafting for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013:Cd001737. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001737.pub4. [CrossRef]

- Turner N.J., Badylak S.F. The use of biologic scaffolds in the treatment of chronic nonhealing wounds. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2015;4:490-500. https://doi.org/10.1089/wound.2014.0604. [CrossRef]

- Dai C., Shih S., Khachemoune A. Skin substitutes for acute and chronic wound healing: An updated review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:639-648. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546634.2018.1530443. [CrossRef]

- Towler M.A., Rush E.W., Richardson M.K., Williams C.L. Randomized, prospective, blinded-enrollment, head-to-head venous leg ulcer healing trial comparing living, bioengineered skin graft substitute (apligraf) with living, cryopreserved, human skin allograft (theraskin). Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2018;35:357-365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpm.2018.02.006. [CrossRef]

- Roy A., Mantay M., Brannan C., Griffiths S. Placental tissues as biomaterials in regenerative medicine. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:6751456. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6751456. [CrossRef]

- Pogozhykh O., Prokopyuk V., Figueiredo C., Pogozhykh D. Placenta and placental derivatives in regenerative therapies: Experimental studies, history, and prospects. Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018:4837930. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4837930. [CrossRef]

- Underwood M.A., Gilbert W.M., Sherman M.P. Amniotic fluid: Not just fetal urine anymore. J Perinatol. 2005;25:341-348. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211290. [CrossRef]

- Tong X.L., Wang L., Gao T.B., Qin Y.G., Qi Y.Q., Xu Y.P. Potential function of amniotic fluid in fetal development---novel insights by comparing the composition of human amniotic fluid with umbilical cord and maternal serum at mid and late gestation. J Chin Med Assoc. 2009;72:368-373. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1726-4901(09)70389-2. [CrossRef]

- Suliburska J., Kocyłowski R., Komorowicz I., Grzesiak M., Bogdański P., Barałkiewicz D. Concentrations of mineral in amniotic fluid and their relations to selected maternal and fetal parameters. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2016;172:37-45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-015-0557-3. [CrossRef]

- Nyman E., Huss F., Nyman T., Junker J., Kratz G. Hyaluronic acid, an important factor in the wound healing properties of amniotic fluid: In vitro studies of re-epithelialisation in human skin wounds. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2013;47:89-92. https://doi.org/10.3109/2000656x.2012.733169. [CrossRef]

- Lim J.J., Koob T.J. Placental cells and tissues: The transformative rise in advanced wound care. In: Worldwide wound healing - innovation in natural and conventional methods. 2016.

- Bourne G. The foetal membranes. A review of the anatomy of normal amnion and chorion and some aspects of their function. Postgrad Med J. 1962;38:193-201. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.38.438.193. [CrossRef]

- Mamede A.C., Carvalho M.J., Abrantes A.M., Laranjo M., Maia C.J., Botelho M.F. Amniotic membrane: From structure and functions to clinical applications. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;349:447-458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-012-1424-6. [CrossRef]

- Parry S., Strauss J.F., 3rd. Premature rupture of the fetal membranes. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:663-670. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199803053381006. [CrossRef]

- Gude N.M., Roberts C.T., Kalionis B., King R.G. Growth and function of the normal human placenta. Thromb Res. 2004;114:397-407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2004.06.038. [CrossRef]

- Chen C.P., Aplin J.D. Placental extracellular matrix: Gene expression, deposition by placental fibroblasts and the effect of oxygen. Placenta. 2003;24:316-325. https://doi.org/10.1053/plac.2002.0904. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y., Zhao S. Integrated systems physiology: From molecules to function to disease. In: Vascular biology of the placenta. San Rafael (CA): Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences Copyright © 2010 by Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences.; 2010.

- Ferguson V.L., Dodson R.B. Bioengineering aspects of the umbilical cord. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;144 Suppl 1:S108-113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.02.024. [CrossRef]

- Spurway J., Logan P., Pak S. The development, structure and blood flow within the umbilical cord with particular reference to the venous system. Australas J Ultrasound Med. 2012;15:97-102. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2205-0140.2012.tb00013.x. [CrossRef]

- Meyer F.A., Laver-Rudich Z., Tanenbaum R. Evidence for a mechanical coupling of glycoprotein microfibrils with collagen fibrils in wharton's jelly. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;755:376-387. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4165(83)90241-6. [CrossRef]

- Sobolewski K., Bańkowski E., Chyczewski L., Jaworski S. Collagen and glycosaminoglycans of wharton's jelly. Biol Neonate. 1997;71:11-21. https://doi.org/10.1159/000244392. [CrossRef]

- Franc S., Rousseau J.C., Garrone R., van der Rest M., Moradi-Améli M. Microfibrillar composition of umbilical cord matrix: Characterization of fibrillin, collagen vi and intact collagen v. Placenta. 1998;19:95-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0143-4004(98)90104-7. [CrossRef]

- Wang H.S., Hung S.C., Peng S.T., Huang C.C., Wei H.M., Guo Y.J., Fu Y.S., Lai M.C., Chen C.C. Mesenchymal stem cells in the wharton's jelly of the human umbilical cord. Stem Cells. 2004;22:1330-1337. https://doi.org/10.1634/stemcells.2004-0013. [CrossRef]

- Sobolewski K., Małkowski A., Bańkowski E., Jaworski S. Wharton's jelly as a reservoir of peptide growth factors. Placenta. 2005;26:747-752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2004.10.008. [CrossRef]

- McElreavey K.D., Irvine A.I., Ennis K.T., McLean W.H. Isolation, culture and characterisation of fibroblast-like cells derived from the wharton's jelly portion of human umbilical cord. Biochem Soc Trans. 1991;19:29s. https://doi.org/10.1042/bst019029s. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi K., Kubota T., Aso T. Study on myofibroblast differentiation in the stromal cells of wharton's jelly: Expression and localization of alpha-smooth muscle actin. Early Hum Dev. 1998;51:223-233. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-3782(97)00123-0. [CrossRef]

- Fénelon M., Catros S., Meyer C., Fricain J.C., Obert L., Auber F., Louvrier A., Gindraux F. Applications of human amniotic membrane for tissue engineering. Membranes (Basel). 2021;11. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes11060387. [CrossRef]

- Koob T.J., Lim J.J., Massee M., Zabek N., Rennert R., Gurtner G., Li W.W. Angiogenic properties of dehydrated human amnion/chorion allografts: Therapeutic potential for soft tissue repair and regeneration. Vasc Cell. 2014;6:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/2045-824x-6-10. [CrossRef]

- Shimmura S., Shimazaki J., Ohashi Y., Tsubota K. Antiinflammatory effects of amniotic membrane transplantation in ocular surface disorders. Cornea. 2001;20:408-413. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003226-200105000-00015. [CrossRef]

- Moreno S.E., Massee M., Koob T.J. Dehydrated human amniotic membrane regulates tenocyte expression and angiogenesis in vitro: Implications for a therapeutic treatment of tendinopathy. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2022;110:731-742. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.34951. [CrossRef]

- Hao Y., Ma D.H., Hwang D.G., Kim W.S., Zhang F. Identification of antiangiogenic and antiinflammatory proteins in human amniotic membrane. Cornea. 2000;19:348-352. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003226-200005000-00018. [CrossRef]

- King A.E., Paltoo A., Kelly R.W., Sallenave J.M., Bocking A.D., Challis J.R. Expression of natural antimicrobials by human placenta and fetal membranes. Placenta. 2007;28:161-169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2006.01.006. [CrossRef]

- Mencucci R., Paladini I., Menchini U., Gicquel J.J., Dei R. Inhibition of viral replication in vitro by antiviral-treated amniotic membrane. Possible use of amniotic membrane as drug-delivering tool. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:28-31. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2010.179556. [CrossRef]

- Ramuta T., Šket T., Starčič Erjavec M., Kreft M.E. Antimicrobial activity of human fetal membranes: From biological function to clinical use. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;9:691522. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2021.691522. [CrossRef]

- Mamede K.M., Sant'anna L.B. Antifibrotic effects of total or partial application of amniotic membrane in hepatic fibrosis. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2019;91:e20190220. https://doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765201920190220. [CrossRef]

- Niknejad H., Deihim T., Solati-Hashjin M., Peirovi H. The effects of preservation procedures on amniotic membrane's ability to serve as a substrate for cultivation of endothelial cells. Cryobiology. 2011;63:145-151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cryobiol.2011.08.003. [CrossRef]

- Wassmer C.H., Berishvili E. Immunomodulatory properties of amniotic membrane derivatives and their potential in regenerative medicine. Curr Diab Rep. 2020;20:31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-020-01316-w. [CrossRef]

- Warning J.C., McCracken S.A., Morris J.M. A balancing act: Mechanisms by which the fetus avoids rejection by the maternal immune system. Reproduction. 2011;141:715-724. https://doi.org/10.1530/rep-10-0360. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia M., Pereira M., Rana H., Stout B., Lewis C., Abramson S., Labazzo K., Ray C., Liu Q., Hofgartner W., Hariri R. The mechanism of cell interaction and response on decellularized human amniotic membrane: Implications in wound healing. Wounds. 2007;19:207-217.

- Cheng H.Y. The impact of mesenchymal stem cell source on proliferation, differentiation, immunomodulation and therapeutic efficacy. Journal of Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2014;04. https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7633.1000237. [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson A., McIntosh R.S., Tighe P.J., James D.K., Dua H.S. Amniotic membrane for ocular surface reconstruction: Donor variations and the effect of handling on tgf-beta content. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4316-4322. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.05-1415. [CrossRef]

- Jang T.H., Park S.C., Yang J.H., Kim J.Y., Seok J.H., Park U.S., Choi C.W., Lee S.R., Han J. Cryopreservation and its clinical applications. Integr Med Res. 2017;6:12-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imr.2016.12.001. [CrossRef]

- Hunt C.J. Cryopreservation: Vitrification and controlled rate cooling. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1590:41-77. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-6921-0_5. [CrossRef]

- Kruse F.E., Joussen A.M., Rohrschneider K., You L., Sinn B., Baumann J., Völcker H.E. Cryopreserved human amniotic membrane for ocular surface reconstruction. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2000;238:68-75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004170050012. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ares M.T., López-Valladares M.J., Touriño R., Vieites B., Gude F., Silva M.T., Couceiro J. Effects of lyophilization on human amniotic membrane. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87:396-403. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-3768.2008.01261.x. [CrossRef]

- Mensink M.A., Frijlink H.W., van der Voort Maarschalk K., Hinrichs W.L. How sugars protect proteins in the solid state and during drying (review): Mechanisms of stabilization in relation to stress conditions. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2017;114:288-295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2017.01.024. [CrossRef]

- Mao Y., Protzman N.M., John N., Kuehn A., Long D., Sivalenka R., Junka R.A., Shah A.U., Gosiewska A., Hariri R.J., Brigido S.A. An in vitro comparison of human corneal epithelial cell activity and inflammatory response on differently designed ocular amniotic membranes and a clinical case study. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2023;111:684-700. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.35186. [CrossRef]

- Aamodt J.M., Grainger D.W. Extracellular matrix-based biomaterial scaffolds and the host response. Biomaterials. 2016;86:68-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.02.003. [CrossRef]

- Cesur N.P., Yalman V., LaÇİN TÜRkoĞLu N. Decellularization of tissues and organs. Cumhuriyet Medical Journal. 2020. https://doi.org/10.7197/cmj.vi.609592. [CrossRef]

- Gilpin A., Yang Y. Decellularization strategies for regenerative medicine: From processing techniques to applications. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:9831534. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9831534. [CrossRef]

- Keane T.J., Swinehart I.T., Badylak S.F. Methods of tissue decellularization used for preparation of biologic scaffolds and in vivo relevance. Methods. 2015;84:25-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.03.005. [CrossRef]

- Crapo P.M., Gilbert T.W., Badylak S.F. An overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3233-3243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.057. [CrossRef]

- Neishabouri A., Soltani Khaboushan A., Daghigh F., Kajbafzadeh A.M., Majidi Zolbin M. Decellularization in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: Evaluation, modification, and application methods. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:805299. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2022.805299. [CrossRef]

- Leonel L., Miranda C., Coelho T.M., Ferreira G.A.S., Caãada R.R., Miglino M.A., Lobo S.E. Decellularization of placentas: Establishing a protocol. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2017;51:e6382. https://doi.org/10.1590/1414-431x20176382. [CrossRef]

- Schneider K.H., Enayati M., Grasl C., Walter I., Budinsky L., Zebic G., Kaun C., Wagner A., Kratochwill K., Redl H., Teuschl A.H., Podesser B.K., Bergmeister H. Acellular vascular matrix grafts from human placenta chorion: Impact of ecm preservation on graft characteristics, protein composition and in vivo performance. Biomaterials. 2018;177:14-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.05.045. [CrossRef]

- Asgari F., Asgari H.R., Najafi M., Eftekhari B.S., Vardiani M., Gholipourmalekabadi M., Koruji M. Optimization of decellularized human placental macroporous scaffolds for spermatogonial stem cells homing. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2021;32:47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10856-021-06517-7. [CrossRef]

- Henry J.J.D., Delrosario L., Fang J., Wong S.Y., Fang Q., Sievers R., Kotha S., Wang A., Farmer D., Janaswamy P., Lee R.J., Li S. Development of injectable amniotic membrane matrix for postmyocardial infarction tissue repair. Adv Healthc Mater. 2020;9:e1900544. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.201900544. [CrossRef]

- Wilshaw S.P., Kearney J., Fisher J., Ingham E. Biocompatibility and potential of acellular human amniotic membrane to support the attachment and proliferation of allogeneic cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:463-472. https://doi.org/10.1089/tea.2007.0145. [CrossRef]

- Schneider K.H., Aigner P., Holnthoner W., Monforte X., Nürnberger S., Rünzler D., Redl H., Teuschl A.H. Decellularized human placenta chorion matrix as a favorable source of small-diameter vascular grafts. Acta Biomater. 2016;29:125-134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2015.09.038. [CrossRef]

- Flynn L., Semple J.L., Woodhouse K.A. Decellularized placental matrices for adipose tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;79:359-369. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.a.30762. [CrossRef]

- Gholipourmalekabadi M., Bandehpour M., Mozafari M., Hashemi A., Ghanbarian H., Sameni M., Salimi M., Gholami M., Samadikuchaksaraei A. Decellularized human amniotic membrane: More is needed for an efficient dressing for protection of burns against antibiotic-resistant bacteria isolated from burn patients. Burns. 2015;41:1488-1497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2015.04.015. [CrossRef]

- Funamoto S., Nam K., Kimura T., Murakoshi A., Hashimoto Y., Niwaya K., Kitamura S., Fujisato T., Kishida A. The use of high-hydrostatic pressure treatment to decellularize blood vessels. Biomaterials. 2010;31:3590-3595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.073. [CrossRef]

- Sevastianov V.I., Basok Y.B., Grigoriev A.M., Nemets E.A., Kirillova A.D., Kirsanova L.A., Lazhko A.E., Subbot A., Kravchik M.V., Khesuani Y.D., Koudan E.V., Gautier S.V. Decellularization of cartilage microparticles: Effects of temperature, supercritical carbon dioxide and ultrasound on biochemical, mechanical, and biological properties. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2023;111:543-555. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.a.37474. [CrossRef]

- Nonaka P.N., Campillo N., Uriarte J.J., Garreta E., Melo E., de Oliveira L.V., Navajas D., Farré R. Effects of freezing/thawing on the mechanical properties of decellularized lungs. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014;102:413-419. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.a.34708. [CrossRef]

- Pulver, Shevtsov A., Leybovich B., Artyuhov I., Maleev Y., Peregudov A. Production of organ extracellular matrix using a freeze-thaw cycle employing extracellular cryoprotectants. Cryo Letters. 2014;35:400-406.

- Luo G., Cheng W., He W., Wang X., Tan J., Fitzgerald M., Li X., Wu J. Promotion of cutaneous wound healing by local application of mesenchymal stem cells derived from human umbilical cord blood. Wound Repair Regen. 2010;18:506-513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2010.00616.x. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Allah S.H., El-Shal A.S., Shalaby S.M., Abd-Elbary E., Mazen N.F., Abdel Kader R.R. The role of placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells in healing of induced full-thickness skin wound in a mouse model. IUBMB Life. 2015;67:701-709. https://doi.org/10.1002/iub.1427. [CrossRef]

- Meamar R., Ghasemi-Mobarakeh L., Norouzi M.R., Siavash M., Hamblin M.R., Fesharaki M. Improved wound healing of diabetic foot ulcers using human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells in gelatin electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds plus a platelet-rich plasma gel: A randomized clinical trial. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;101:108282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2021.108282. [CrossRef]

- Protzman N.M., Brigido S.A. Recent advances in acellular regenerative tissue scaffolds. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2015;32:147-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpm.2014.09.008. [CrossRef]

- Koob T.J., Lim J.J., Massee M., Zabek N., Denoziere G. Properties of dehydrated human amnion/chorion composite grafts: Implications for wound repair and soft tissue regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2014;102:1353-1362. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.33141. [CrossRef]

- Smiell J.M., Treadwell T., Hahn H.D., Hermans M.H. Real-world experience with a decellularized dehydrated human amniotic membrane allograft. Wounds. 2015;27:158-169.

- Letendre S., LaPorta G., O'Donnell E., Dempsey J., Leonard K. Pilot trial of biovance collagen-based wound covering for diabetic ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2009;22:161-166. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.Asw.0000305463.32800.32. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi C., Cazzell S., Vayser D., Reyzelman A.M., Dosluoglu H., Tovmassian G. A multicentre randomised controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane (epifix(®) ) allograft for the treatment of venous leg ulcers. Int Wound J. 2018;15:114-122. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12843. [CrossRef]

- Mrugala A., Sui A., Plummer M., Altman I., Papineau E., Frandsen D., Hill D., Ennis W.J. Amniotic membrane is a potential regenerative option for chronic non-healing wounds: A report of five cases receiving dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane allograft. Int Wound J. 2016;13:485-492. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12458. [CrossRef]

- Caporusso J., Abdo R., Karr J., Smith M., Anaim A. Clinical experience using a dehydrated amnion/chorion membrane construct for the management of wounds. Wounds. 2019;31:S19-s27.

- Tettelbach W., Cazzell S., Reyzelman A.M., Sigal F., Caporusso J.M., Agnew P.S. A confirmatory study on the efficacy of dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane dhacm allograft in the management of diabetic foot ulcers: A prospective, multicentre, randomised, controlled study of 110 patients from 14 wound clinics. Int Wound J. 2019;16:19-29. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12976. [CrossRef]

- Tettelbach W.H., Cazzell S.M., Hubbs B., Jong J.L., Forsyth R.A., Reyzelman A.M. The influence of adequate debridement and placental-derived allografts on diabetic foot ulcers. J Wound Care. 2022;31:S16-s26. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2022.31.Sup9.S16. [CrossRef]

- Tettelbach W., Cazzell S., Sigal F., Caporusso J.M., Agnew P.S., Hanft J., Dove C. A multicentre prospective randomised controlled comparative parallel study of dehydrated human umbilical cord (epicord) allograft for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Int Wound J. 2019;16:122-130. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.13001. [CrossRef]

- Garoufalis M., Tettelbach W. Expandable dehydrated human umbilical cord allograft for the management of nonhealing lower extremity wounds in patients with diabetes: A case series. Wounds. 2022;34:E91-e95. https://doi.org/10.25270/wnds/21126. [CrossRef]

- Couture M. A single-center, retrospective study of cryopreserved umbilical cord for wound healing in patients suffering from chronic wounds of the foot and ankle. Wounds. 2016;28:217-225.

- Raphael A. A single-centre, retrospective study of cryopreserved umbilical cord/amniotic membrane tissue for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. J Wound Care. 2016;25:S10-s17. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2016.25.Sup7.S10. [CrossRef]

- Raphael A., Grimes L. Implantation of cryopreserved umbilical cord allograft in hard-to-heal foot wounds: A retrospective study. J Wound Care. 2020;29:S12-s17. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2020.29.Sup8.S12. [CrossRef]

- Bemenderfer T.B., Anderson R.B., Odum S.M., Davis W.H. Effects of cryopreserved amniotic membrane-umbilical cord allograft on total ankle arthroplasty wound healing. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2019;58:97-102. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jfas.2018.08.014. [CrossRef]

- Koizumi N.J., Inatomi T.J., Sotozono C.J., Fullwood N.J., Quantock A.J., Kinoshita S. Growth factor mrna and protein in preserved human amniotic membrane. Curr Eye Res. 2000;20:173-177.

- Mermet I., Pottier N., Sainthillier J.M., Malugani C., Cairey-Remonnay S., Maddens S., Riethmuller D., Tiberghien P., Humbert P., Aubin F. Use of amniotic membrane transplantation in the treatment of venous leg ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15:459-464. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00252.x. [CrossRef]

- Mohajeri-Tehrani M.R., Variji Z., Mohseni S., Firuz A., Annabestani Z., Zartab H., Rad M.A., Tootee A., Dowlati Y., Larijani B. Comparison of a bioimplant dressing with a wet dressing for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Wounds. 2016;28:248-254.

- Moore M.C., Van De Walle A., Chang J., Juran C., McFetridge P.S. Human perinatal-derived biomaterials. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.201700345. [CrossRef]

- Irvin J., Danchik C., Rall J., Babcock A., Pine M., Barnaby D., Pathakamuri J., Kuebler D. Bioactivity and composition of a preserved connective tissue matrix derived from human placental tissue. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2018;106:2731-2740. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.34054. [CrossRef]

- Brigido S.A., Carrington S.C., Protzman N.M. The use of decellularized human placenta in full-thickness wound repair and periarticular soft tissue reconstruction: An update on regenerative healing. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2018;35:95-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpm.2017.08.010. [CrossRef]

- Protzman N.M., Mao Y., Sivalenka R., Long D., Gosiewska A., Hariri R., Brigido S.A. Flowable placental connective tissue matrices for tendon repair: A review. J Biol Med. 2022;6:010-020. https://doi.org/10.17352/jbm.000030. [CrossRef]

- Zheng Y., Ji S., Wu H., Tian S., Zhang Y., Wang L., Fang H., Luo P., Wang X., Hu X., Xiao S., Xia Z. Topical administration of cryopreserved living micronized amnion accelerates wound healing in diabetic mice by modulating local microenvironment. Biomaterials. 2017;113:56-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.10.031. [CrossRef]

- Garoufalis M., Nagesh D., Sanchez P.J., Lenz R., Park S.J., Ruff J.G., Tien A., Goldsmith J., Seat A. Use of dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane allografts in more than 100 patients with six major types of refractory nonhealing wounds. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2018;108:84-89. https://doi.org/10.7547/17-039. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins B. The use of micronized dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane allograft for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: A case series. Wounds. 2016;28:152-157.

- Amniochor. Available online: https://celltrials.org/sites/default/files/report_files/Amniotic-Membrane-Tissue-Allograft-Products_AmnioChor20170529.pdf. Accessed on: 21 05 2023.

- Davis J. Skin transplantation with a review of 550 cases at the johns hopkins hospital. Johns Hopkins Med. 1910;15:307.

- Serena T.E., Orgill D.P., Armstrong D.G., Galiano R.D., Glat P.M., Carter M.J., Kaufman J.P., Li W.W., Zelen C.M. A multicenter, randomized, controlled, clinical trial evaluating dehydrated human amniotic membrane in the treatment of venous leg ulcers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;150:1128-1136. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000009650. [CrossRef]

- Serena T.E., Yaakov R., Moore S., Cole W., Coe S., Snyder R., Patel K., Doner B., Kasper M.A., Hamil R., Wendling S., Sabolinski M.L. A randomized controlled clinical trial of a hypothermically stored amniotic membrane for use in diabetic foot ulcers. J Comp Eff Res. 2020;9:23-34. https://doi.org/10.2217/cer-2019-0142. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi C., Tettelbach W., Istwan N., Hubbs B., Kot K., Harris S., Fetterolf D. Variations in study outcomes relative to intention-to-treat and per-protocol data analysis techniques in the evaluation of efficacy for treatment of venous leg ulcers with dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane allograft. Int Wound J. 2019;16:761-767. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.13094. [CrossRef]

- DiDomenico L.A., Orgill D.P., Galiano R.D., Serena T.E., Carter M.J., Kaufman J.P., Young N.J., Jacobs A.M., Zelen C.M. Use of an aseptically processed, dehydrated human amnion and chorion membrane improves likelihood and rate of healing in chronic diabetic foot ulcers: A prospective, randomised, multi-centre clinical trial in 80 patients. Int Wound J. 2018;15:950-957. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12954. [CrossRef]

- Zelen C.M., Serena T.E., Snyder R.J. A prospective, randomised comparative study of weekly versus biweekly application of dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane allograft in the management of diabetic foot ulcers. Int Wound J. 2014;11:122-128. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12242. [CrossRef]

- Zelen C.M., Gould L., Serena T.E., Carter M.J., Keller J., Li W.W. A prospective, randomised, controlled, multi-centre comparative effectiveness study of healing using dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane allograft, bioengineered skin substitute or standard of care for treatment of chronic lower extremity diabetic ulcers. Int Wound J. 2015;12:724-732. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12395. [CrossRef]

- Zelen C.M., Serena T.E., Gould L., Le L., Carter M.J., Keller J., Li W.W. Treatment of chronic diabetic lower extremity ulcers with advanced therapies: A prospective, randomised, controlled, multi-centre comparative study examining clinical efficacy and cost. Int Wound J. 2016;13:272-282. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12566. [CrossRef]

- Lavery L.A., Fulmer J., Shebetka K.A., Regulski M., Vayser D., Fried D., Kashefsky H., Owings T.M., Nadarajah J. The efficacy and safety of grafix® for the treatment of chronic diabetic foot ulcers: Results of a multi-centre, controlled, randomised, blinded, clinical trial. Int Wound J. 2014;11:554-560. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12329. [CrossRef]

- Serena T.E., Carter M.J., Le L.T., Sabo M.J., DiMarco D.T. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial evaluating the use of dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane allografts and multilayer compression therapy vs. Multilayer compression therapy alone in the treatment of venous leg ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2014;22:688-693. https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.12227. [CrossRef]

- Zelen C.M., Poka A., Andrews J. Prospective, randomized, blinded, comparative study of injectable micronized dehydrated amniotic/chorionic membrane allograft for plantar fasciitis--a feasibility study. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34:1332-1339. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071100713502179. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi Tofigh A., Tajik M. Comparing the standard surgical dressing with dehydrated amnion and platelet-derived growth factor dressings in the healing rate of diabetic foot ulcer: A randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;185:109775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2022.109775. [CrossRef]

- Game F., Gray K., Davis D., Sherman R., Chokkalingam K., Connan Z., Fakis A., Jones M. The effectiveness of a new dried human amnion derived membrane in addition to standard care in treating diabetic foot ulcers: A patient and assessor blind, randomised controlled pilot study. Int Wound J. 2021;18:692-700. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.13571. [CrossRef]

- Duarte I.G., Duval-Araujo I. Amniotic membrane as a biological dressing in infected wound healing in rabbits. Acta Cir Bras. 2014;29:334-339. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-86502014000500008. [CrossRef]

- Caputo W.J., Vaquero C., Monterosa A., Monterosa P., Johnson E., Beggs D., Fahoury G.J. A retrospective study of cryopreserved umbilical cord as an adjunctive therapy to promote the healing of chronic, complex foot ulcers with underlying osteomyelitis. Wound Repair Regen. 2016;24:885-893. https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.12456. [CrossRef]

- Cooke M., Tan E.K., Mandrycky C., He H., O'Connell J., Tseng S.C. Comparison of cryopreserved amniotic membrane and umbilical cord tissue with dehydrated amniotic membrane/chorion tissue. J Wound Care. 2014;23:465-474, 476. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2014.23.10.465. [CrossRef]

- Brigido S.A., Riniker M.L., Protzman N.M., Constant D.D. Application of acellular amniotic scaffold following total ankle replacement: A retrospective comparison. Clinical Research on Foot & Ankle. 2018;06. https://doi.org/10.4172/2329-910x.1000275. [CrossRef]

- Snyder R.J., Shimozaki K., Tallis A., Kerzner M., Reyzelman A., Lintzeris D., Bell D., Rutan R.L., Rosenblum B. A prospective, randomized, multicenter, controlled evaluation of the use of dehydrated amniotic membrane allograft compared to standard of care for the closure of chronic diabetic foot ulcer. Wounds. 2016;28:70-77.

- Lintzeris D., Yarrow K., Johnson L., White A., Hampton A., Strickland A., Albert K., Cook A. Use of a dehydrated amniotic membrane allograft on lower extremity ulcers in patients with challenging wounds: A retrospective case series. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2015;61:30-36.

- Barr S.M. Dehydrated amniotic membrane allograft for treatment of chronic leg ulcers in patients with multiple comorbidities: A case series. J Am Coll Clin Wound Spec. 2014;6:38-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jccw.2016.01.002. [CrossRef]

- Abdo R.J. Treatment of diabetic foot ulcers with dehydrated amniotic membrane allograft: A prospective case series. J Wound Care. 2016;25:S4-s9. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2016.25.Sup7.S4. [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum B.I. A retrospective case series of a dehydrated amniotic membrane allograft for treatment of unresolved diabetic foot ulcers. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2016;106:328-337. https://doi.org/10.7547/15-139. [CrossRef]

- Doucette M., Payne K.M., Lough W., Beck A., Wayment K., Huffman J., Bond L., Thomas-Vogel A., Langley S. Early advanced therapy for diabetic foot ulcers in high amputation risk veterans: A cohort study. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2022;21:111-119. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534734620928151. [CrossRef]

- Tsai G.L., Zilberbrand D., Liao W.J., Horl L.P. Healing hard-to-heal diabetic foot ulcers: The role of dehydrated amniotic allograft with cross-linked bovine-tendon collagen and glycosaminoglycan matrix. J Wound Care. 2021;30:S47-s53. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2021.30.Sup7.S47. [CrossRef]

- Moore M.C., Bonvallet P.P., Damaraju S.M., Modi H.N., Gandhi A., McFetridge P.S. Biological characterization of dehydrated amniotic membrane allograft: Mechanisms of action and implications for wound care. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2020;108:3076-3083. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.34635. [CrossRef]

- Boyar V., Galiczewski C. Efficacy of dehydrated human amniotic membrane allograft for the treatment of severe extravasation injuries in preterm neonates. Wounds. 2018;30:224-228.

- Lei J., Priddy L.B., Lim J.J., Massee M., Koob T.J. Identification of extracellular matrix components and biological factors in micronized dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2017;6:43-53. https://doi.org/10.1089/wound.2016.0699. [CrossRef]

- Bullard J.D., Lei J., Lim J.J., Massee M., Fallon A.M., Koob T.J. Evaluation of dehydrated human umbilical cord biological properties for wound care and soft tissue healing. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2019;107:1035-1046. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.34196. [CrossRef]

- McQuilling J.P., Vines J.B., Mowry K.C. In vitro assessment of a novel, hypothermically stored amniotic membrane for use in a chronic wound environment. Int Wound J. 2017;14:993-1005. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12748. [CrossRef]

- McQuilling J.P., Vines J.B., Kimmerling K.A., Mowry K.C. Proteomic comparison of amnion and chorion and evaluation of the effects of processing on placental membranes. Wounds. 2017;29:E36-e40.

- McQuilling J.P., Sanders M., Poland L., Sanders M., Basadonna G., Waldrop N.E., Mowry K.C. Dehydrated amnion/chorion improves achilles tendon repair in a diabetic animal model. Wounds. 2019;31:19-25.

- McQuilling J.P., Burnette M., Kimmerling K.A., Kammer M., Mowry K.C. A mechanistic evaluation of the angiogenic properties of a dehydrated amnion chorion membrane in vitro and in vivo. Wound Repair Regen. 2019;27:609-621. https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.12757. [CrossRef]

- Farivar B.S., Toursavadkohi S., Monahan T.S., Sharma J., Ucuzian A.A., Kundi R., Sarkar R., Lal B.K. Prospective study of cryopreserved placental tissue wound matrix in the management of chronic venous leg ulcers. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2019;7:228-233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvsv.2018.09.016. [CrossRef]

- Gibbons G.W. Grafix(®), a cryopreserved placental membrane, for the treatment of chronic/stalled wounds. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2015;4:534-544. https://doi.org/10.1089/wound.2015.0647. [CrossRef]

- Cole A., Lee M., Koloff Z., Ghani K.R. Complex re-do robotic pyeloplasty using cryopreserved placental tissue: An adjunct for success. Int Braz J Urol. 2021;47:214-215. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1677-5538.Ibju.2020.0130. [CrossRef]

- Carter M.J. Dehydrated human amnion and chorion allograft versus standard of care alone in treatment of wagner 1 diabetic foot ulcers: A trial-based health economics study. J Med Econ. 2020;23:1273-1283. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2020.1803888. [CrossRef]

- Serena T.E., Yaakov R., DiMarco D., Le L., Taffe E., Donaldson M., Miller M. Dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane treatment of venous leg ulcers: Correlation between 4-week and 24-week outcomes. J Wound Care. 2015;24:530-534. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2015.24.11.530. [CrossRef]

- Lakmal K., Basnayake O., Hettiarachchi D. Systematic review on the rational use of amniotic membrane allografts in diabetic foot ulcer treatment. BMC Surg. 2021;21:87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-021-01084-8. [CrossRef]

- Paggiaro A.O., Menezes A.G., Ferrassi A.D., De Carvalho V.F., Gemperli R. Biological effects of amniotic membrane on diabetic foot wounds: A systematic review. J Wound Care. 2018;27:S19-s25. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2018.27.Sup2.S19. [CrossRef]

- Gholipourmalekabadi M., Farhadihosseinabadi B., Faraji M., Nourani M.R. How preparation and preservation procedures affect the properties of amniotic membrane? How safe are the procedures? Burns. 2020;46:1254-1271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2019.07.005. [CrossRef]

- Mendibil U., Ruiz-Hernandez R., Retegi-Carrion S., Garcia-Urquia N., Olalde-Graells B., Abarrategi A. Tissue-specific decellularization methods: Rationale and strategies to achieve regenerative compounds. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21155447. [CrossRef]

- Mrdjenovich D.E. Human placental connective tissue matrix (hctm) a pathway toward improved outcomes. In Proceedings of' Symposium on Advanced Wound Care & Wound Healing Society, San Diego, California, United States, 05 04 2017.

| Phase 1. Inflammatory | Phase 2. Proliferative | Phase 3. Remodeling | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Injury – Days 4-6 | Day 4 – Day 14 | Day 8 – 1 Year | |

| Hemostasis: Bleeding stops | Epithelialization | Collagen Synthesis | |

| Chemotaxis | Angiogenesis | Collagen Turnover | |

| Activation | Granulation Tissue Formation | Collagen Organization |

| Local Factors | Systemic Factors |

|---|---|

| Oxygenation | Age |

| Infection | Ambulatory status |

| Venous insufficiency | Co-morbidities (e.g., diabetes, obesity, malnutrition, ischemia) |

| Medications (e.g., steroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) | |

| Oncology interventions (e.g., radiation, chemotherapy) | |

| Lifestyle habits (e.g., smoking, alcohol abuse) |

| Method | Agent | Example(s) | Reference(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical | Ionic Detergents | SDS SDC Triton-X-200 |

[2, 102-104] | |

| Non-ionic detergents | Triton-X-100 | [102-104] | ||

| Zwitterionic | CHAPS SB-10 SB-16 |

[105] | ||

| Acids | Peracetic Acid Hydrochloric Acid |

[106] | ||

| Hypertonic Solutions | Sodium chloride | [105, 107] | ||

| Hypotonic Solutions | Tris-HCl | [105, 107] | ||

| Chelating Agents | EDTA EGTA |

[102, 105, 108, 109] | ||

| Organic Solvents | Ethanol Methanol Acetones |

[102] | ||

| Enzymatic | Proteases | Trypsin | [102] | |

| Nucleases | DNase RNase |

[2, 108] | ||

| Physical | Pressure | High Hydrostatic Pressure Supercritical Fluids |

[5, 110, 111] | |

| Temperature | Freeze-thaw | [107, 111-113] | ||

| Force | Immersion & Agitation Shaking Scraping |

[2, 107, 109] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).