Submitted:

01 June 2023

Posted:

02 June 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

>Mixing Time

- Circulation Model

- ii.

- Jet Turbulence Model

2. Materials and Methods

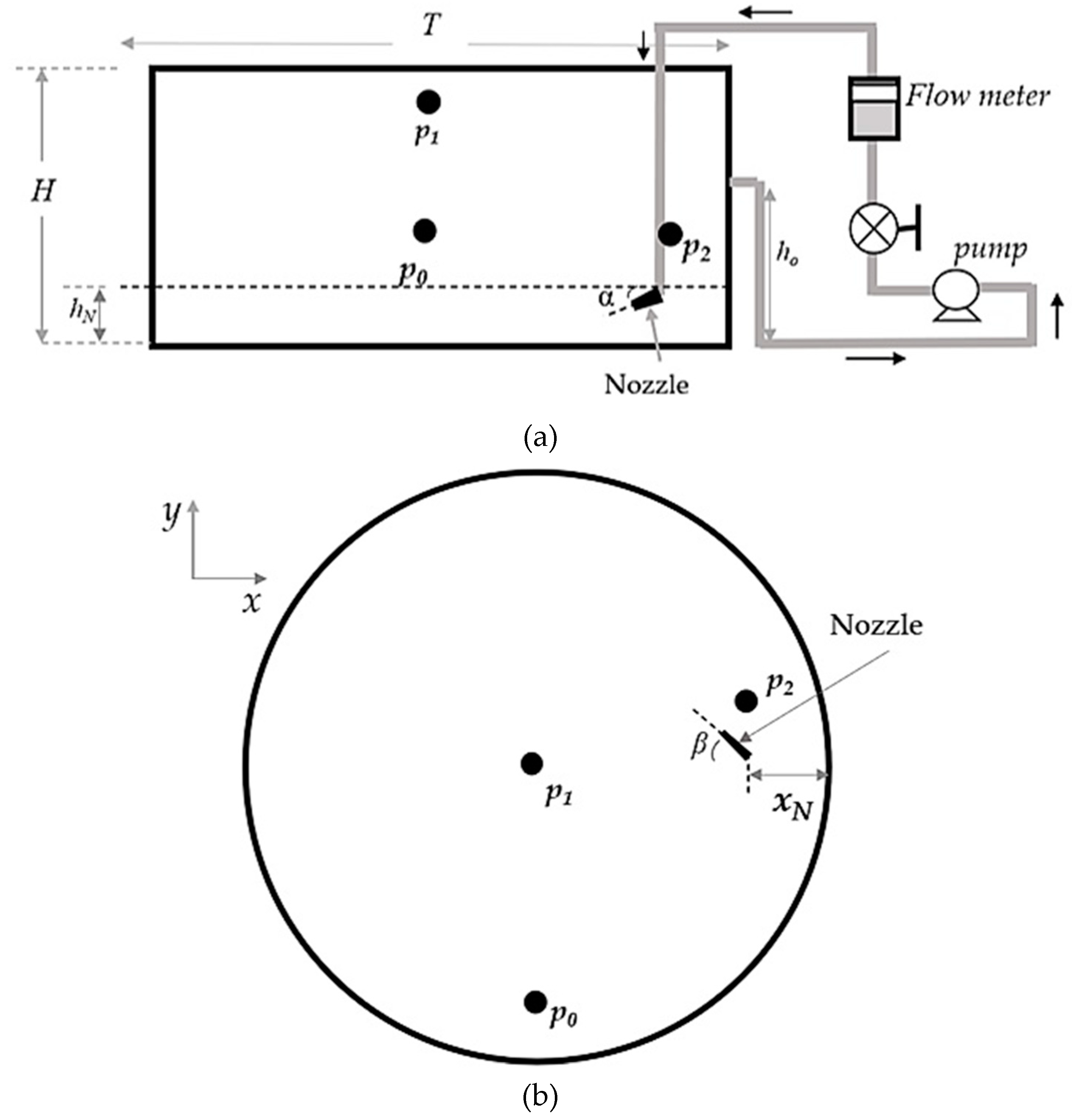

2.1. Experimental Set up and operating conditions

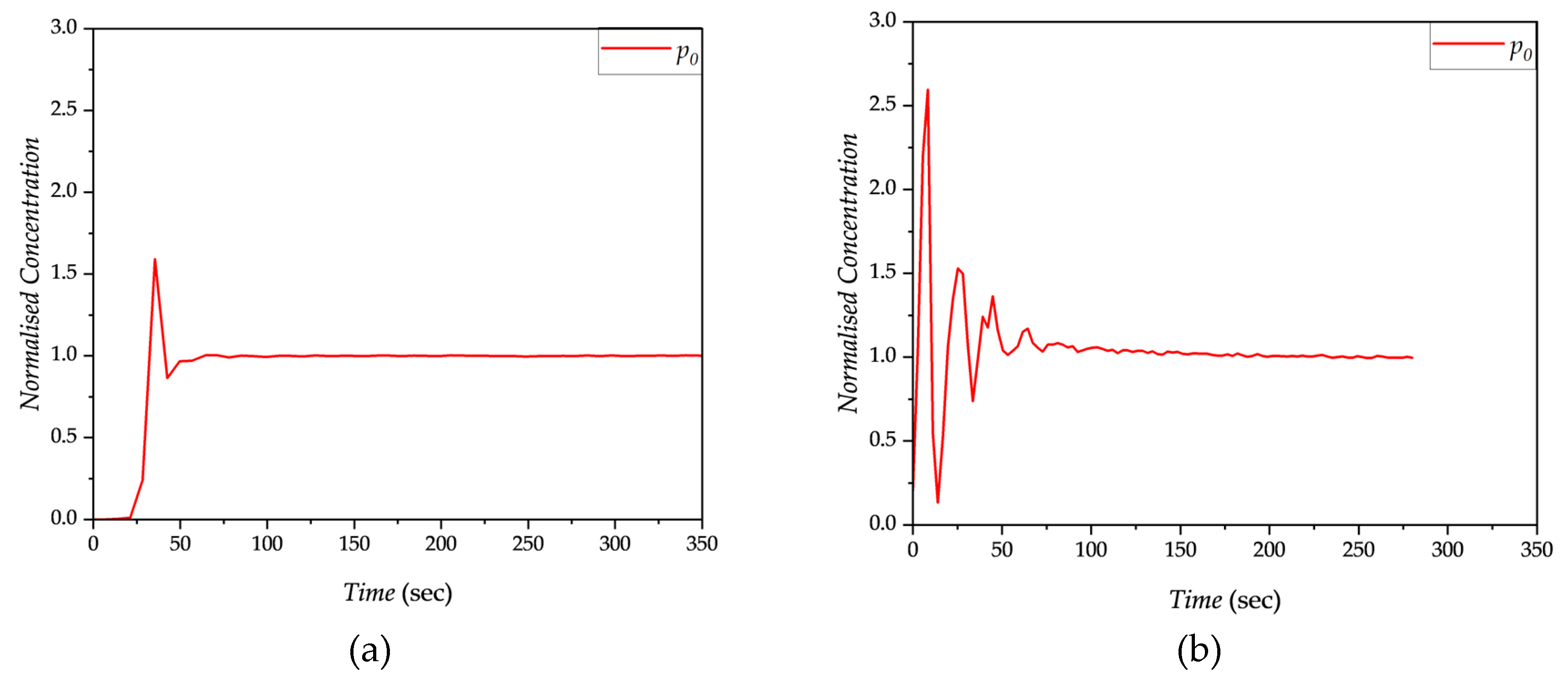

2.2. Mixing time measurements

2.6. The mixing time for each experimental configuration is determined a minimum of two times, and the average value is taken.

3. Results and Discussion

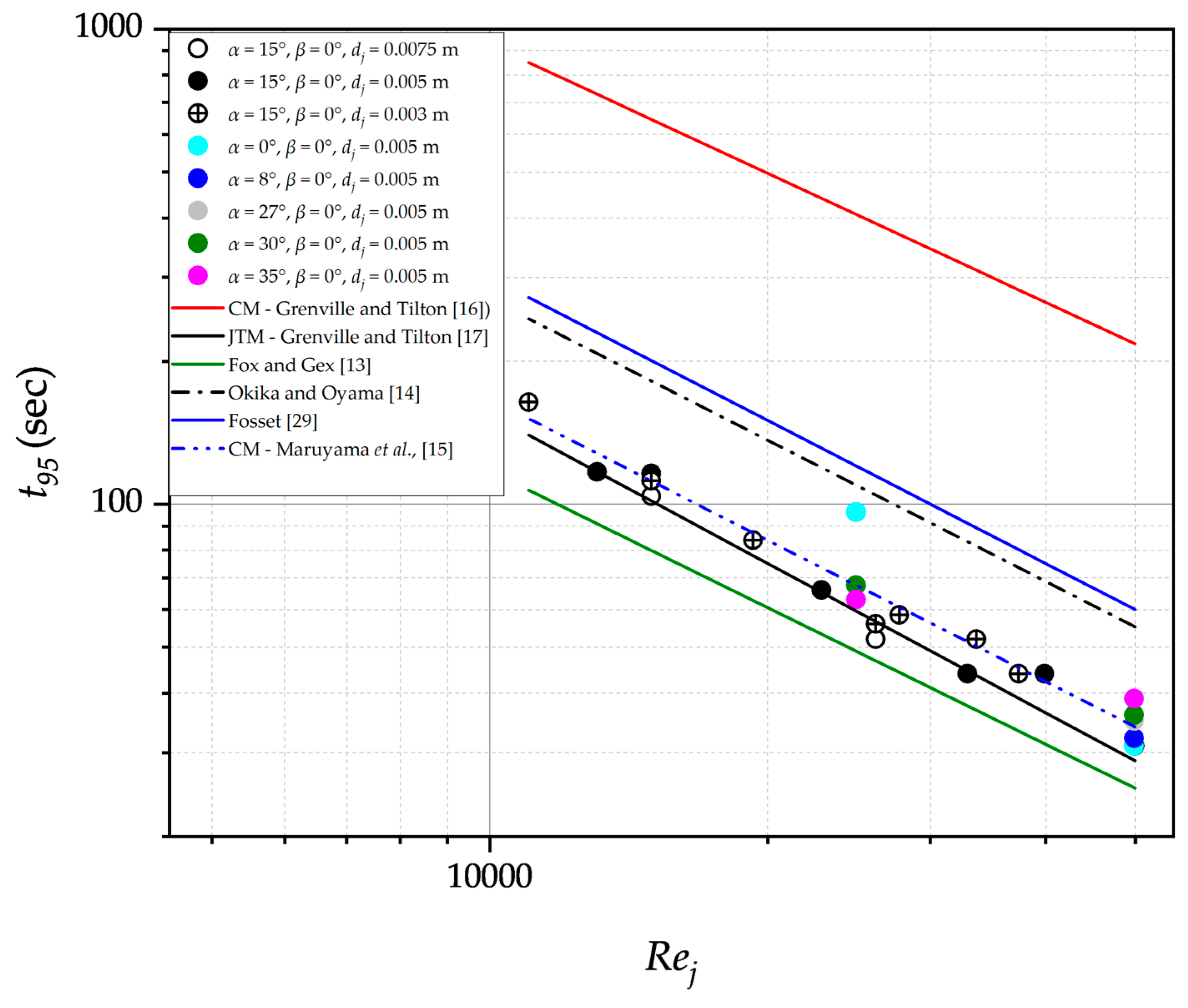

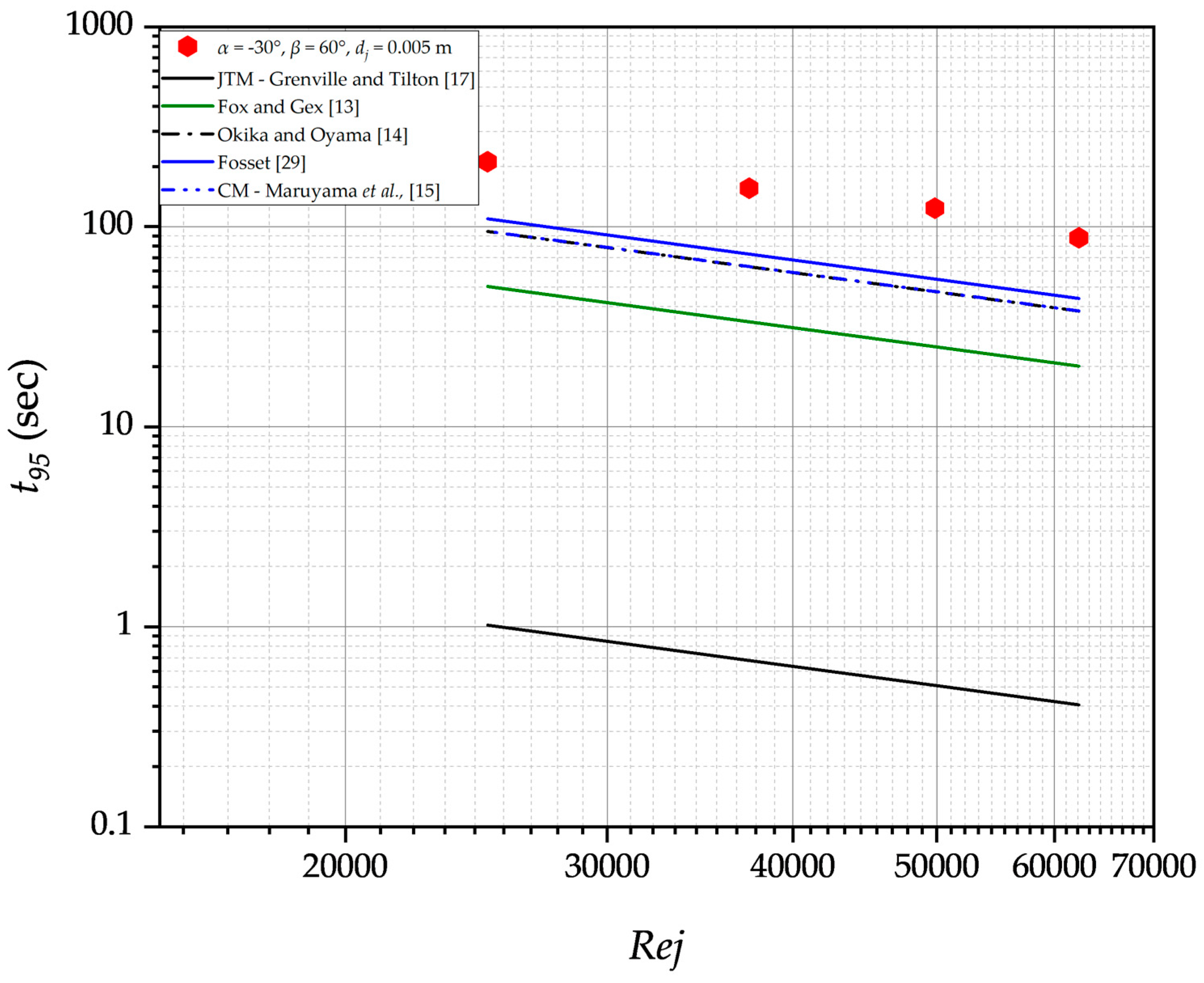

3.1. Experimental Data Prediction by Previous Models

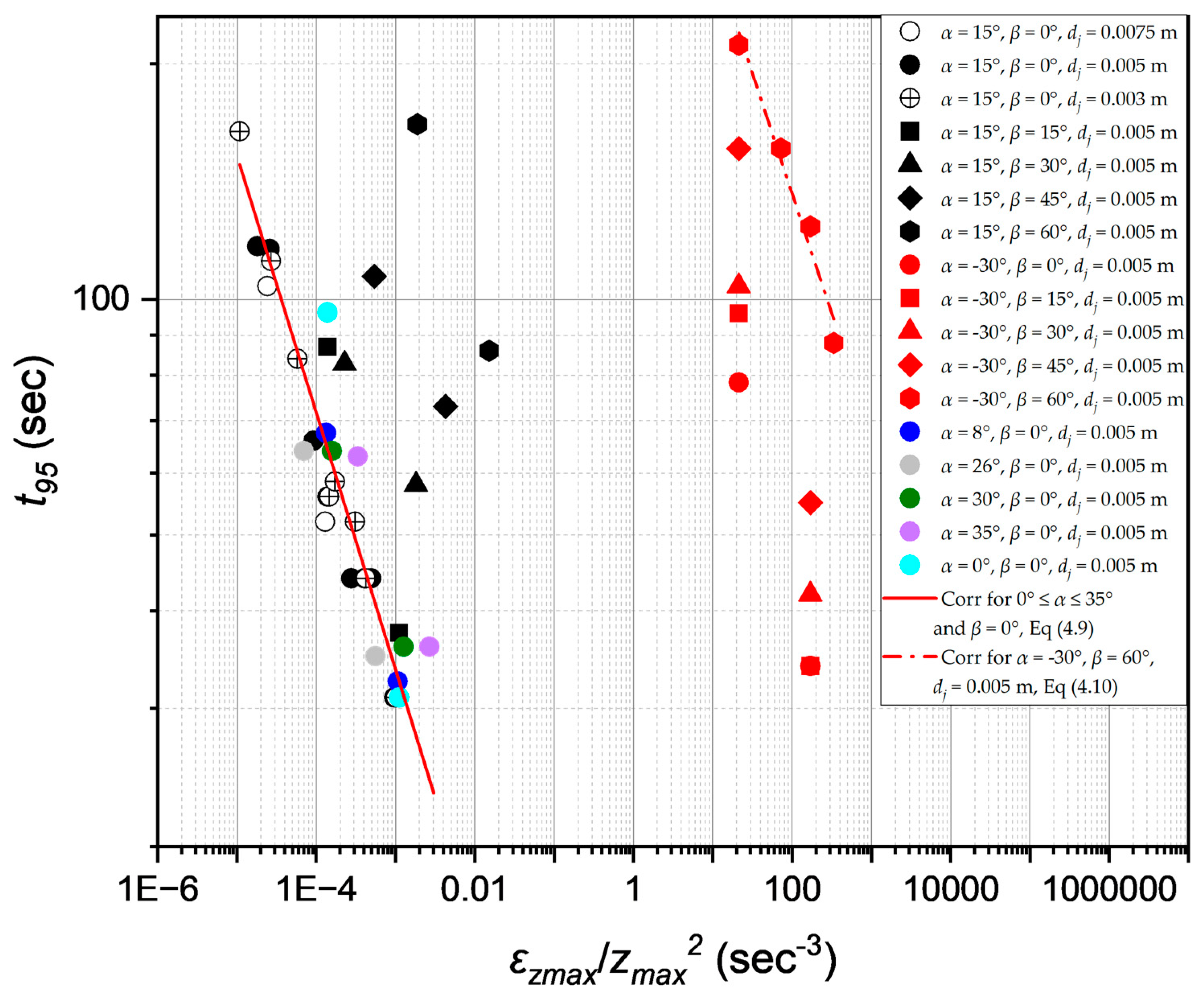

3.2. Correlating experimental data using Jet turbulent model

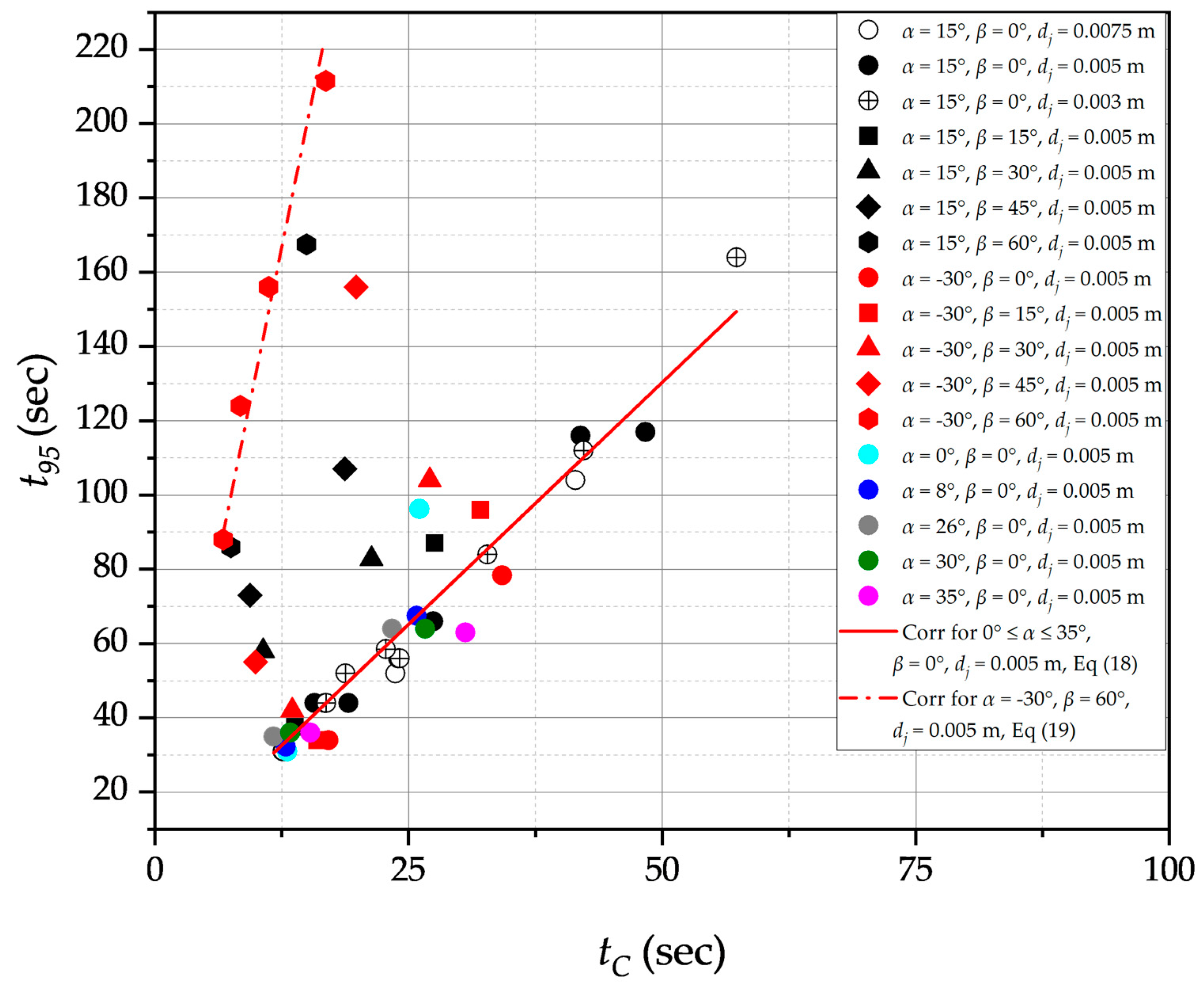

3.3. Correlating experimental data using Circulation Model

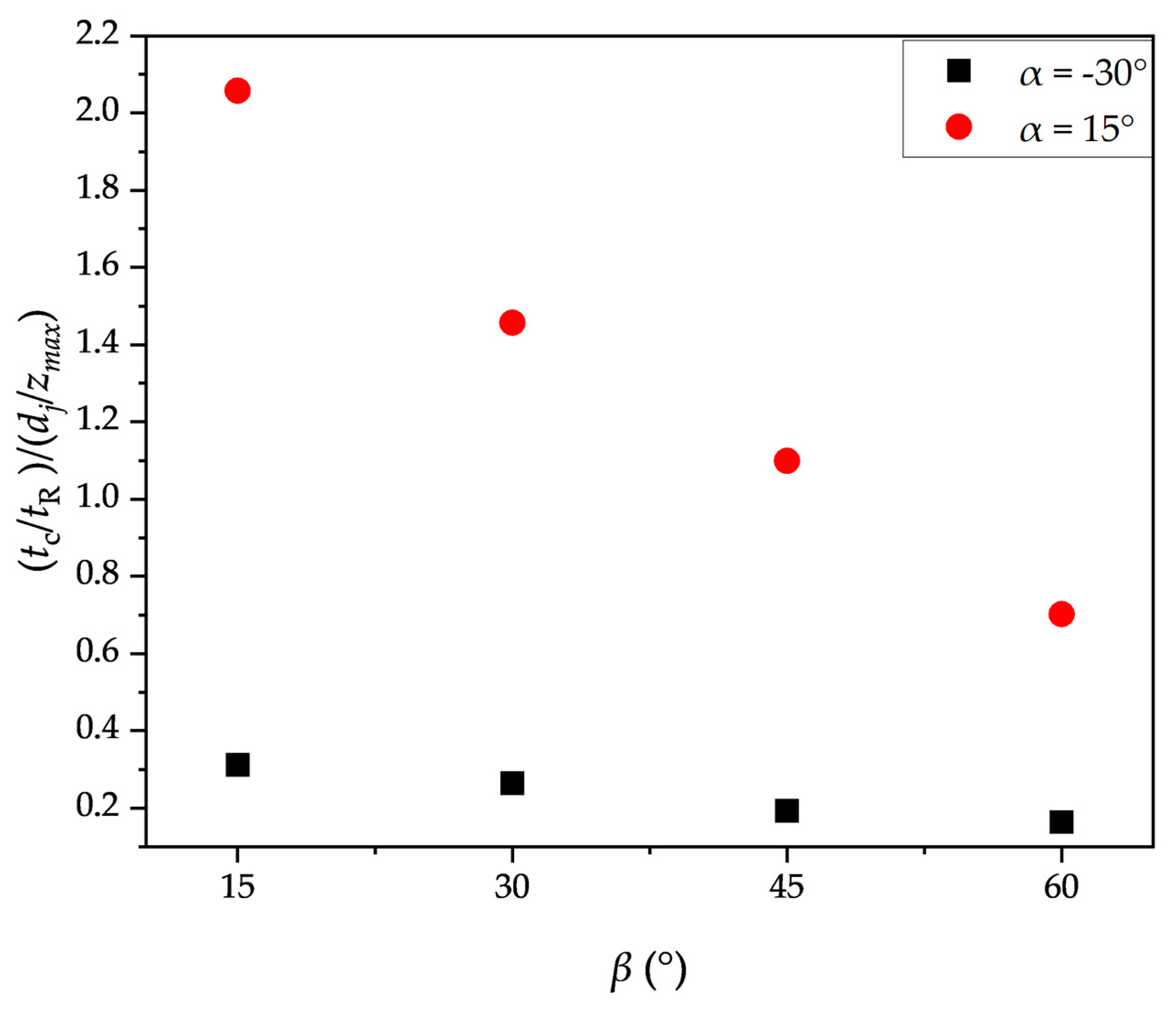

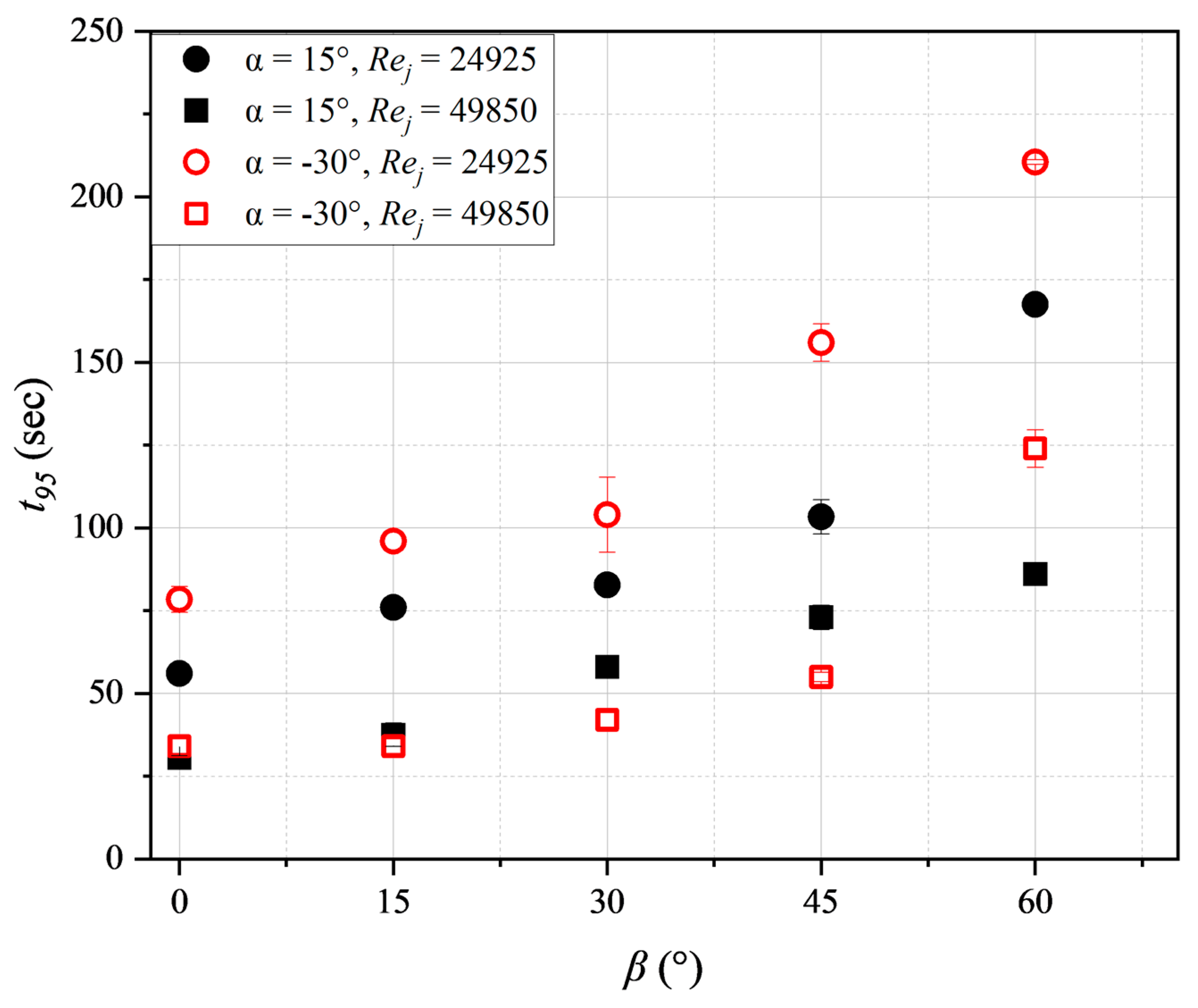

3.4. Impacts of Jet Nozzle Horizontal Position

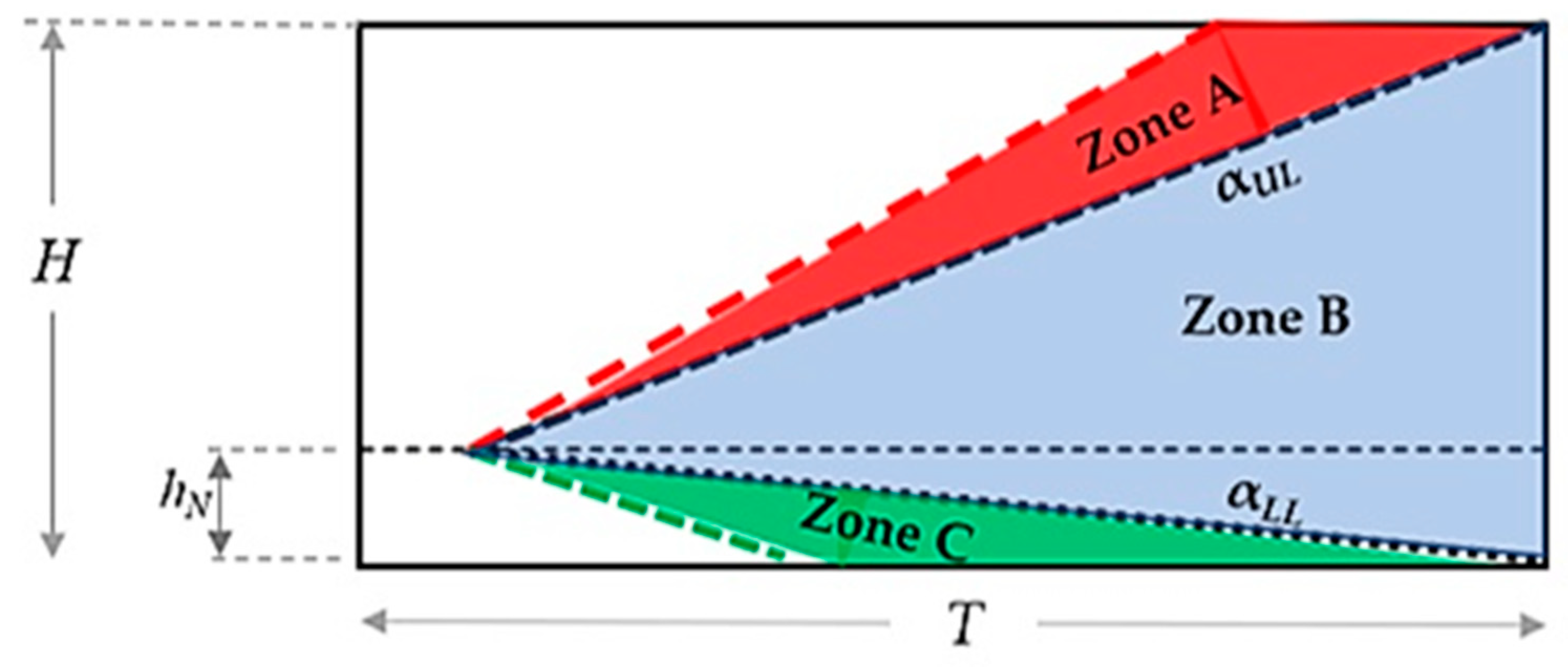

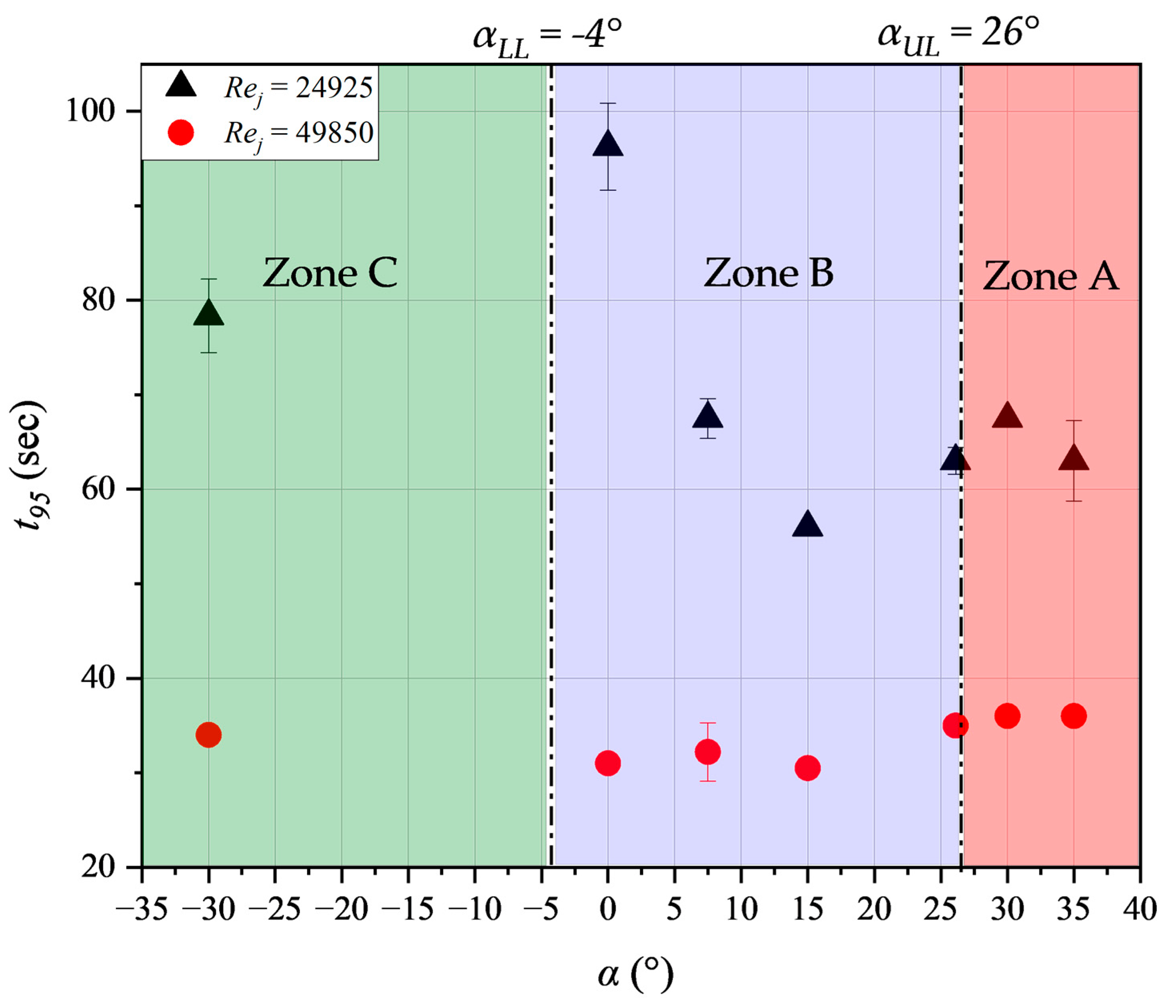

3.5. Impact of the vertical inclination of the nozzle, α

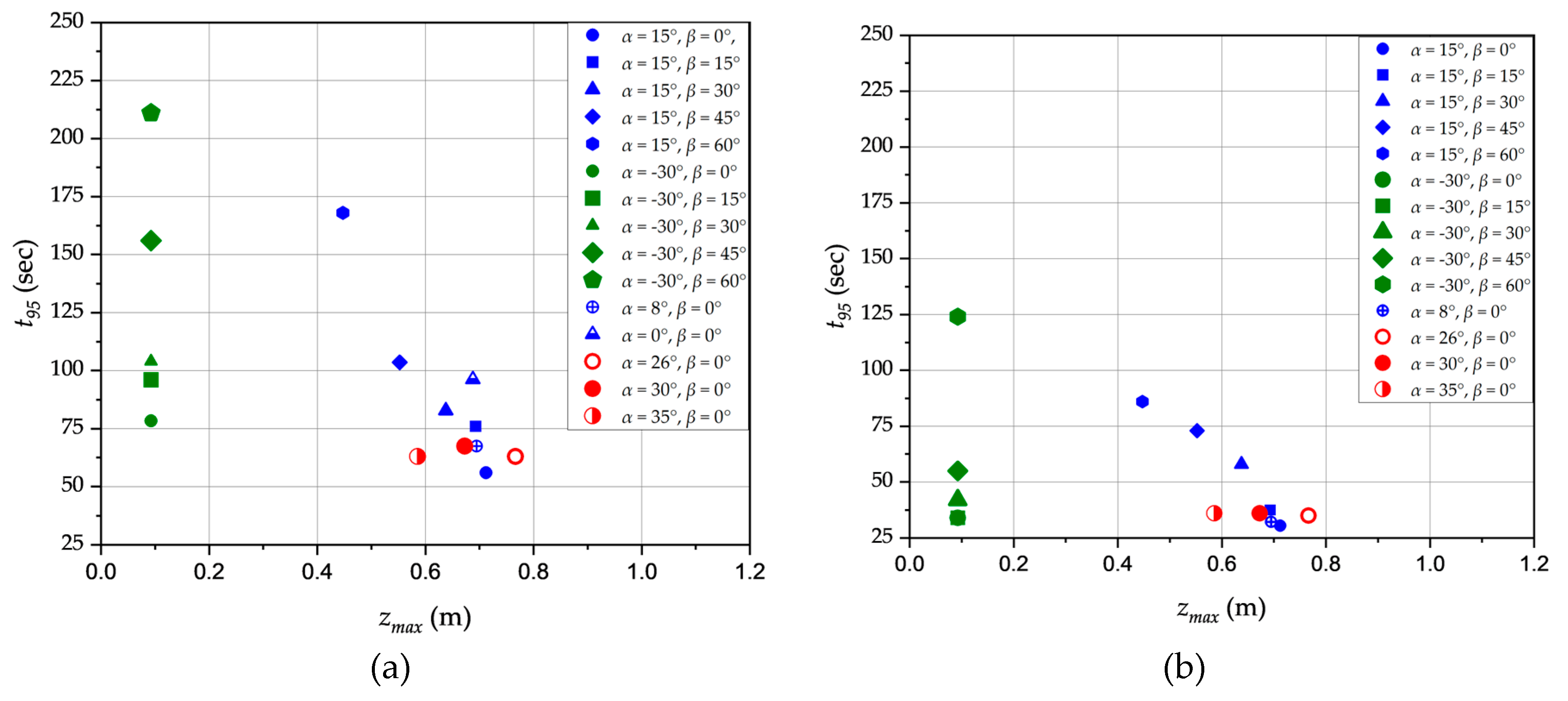

3.6. Impacts of the free jet path length on mixing time

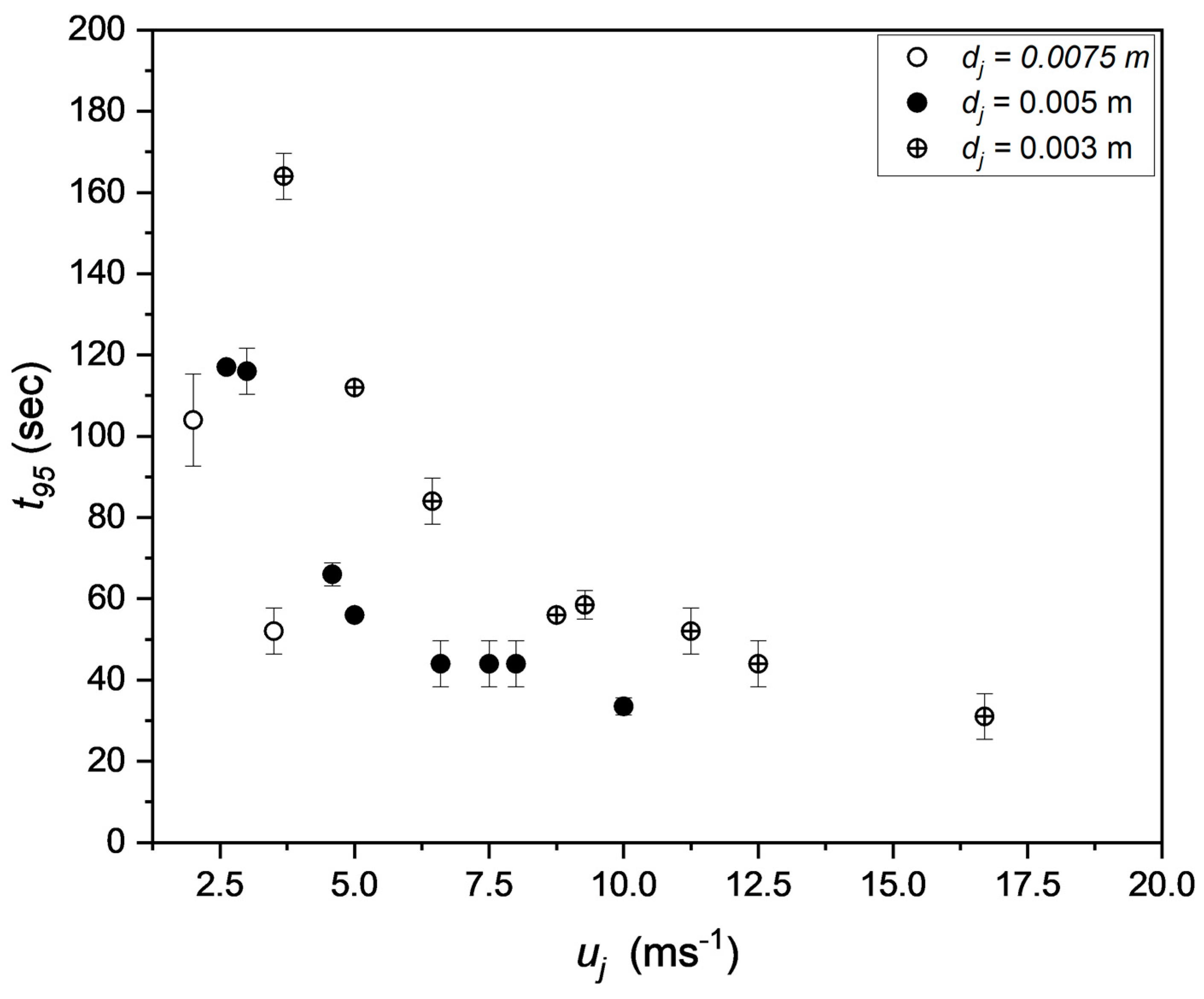

3.7. Impacts of jet nozzle diameter and jet inlet velocity on mixing time

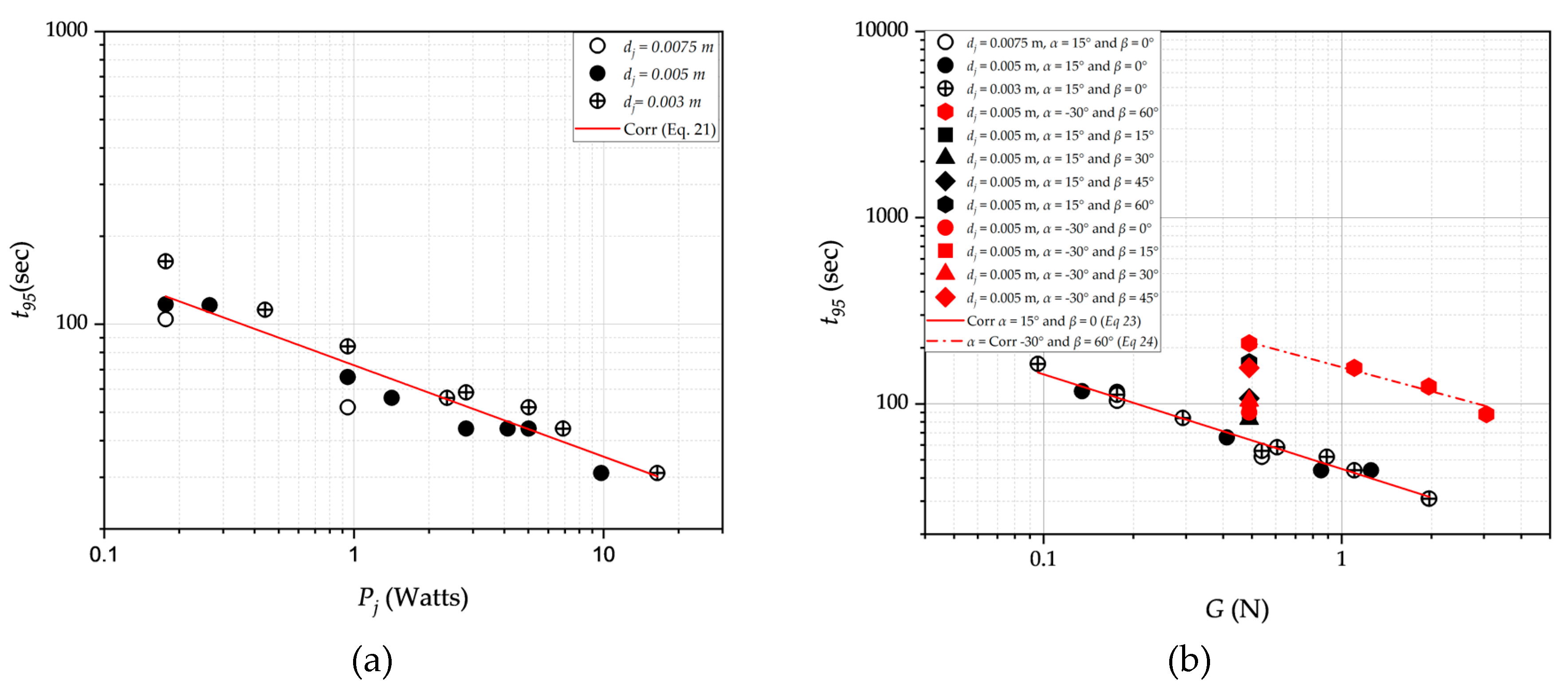

3.7. Mixing time measurements as a function of jet power input and flow momentum

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Ci | Initial Concentration (Moldm-3) |

| Final Concentration (Moldm-3) | |

| dj | Jet nozzle diameter (m) |

| dz | Jet spread diameter at z (m) |

| f | frequency (s-1) |

| Fr | |

| G | Jet flow momentum (N) |

| g | Gravitational force (m/s2) |

| H | Liquid height (m) |

| k | Entrainment rate model constant |

| L | integral scale of concentration fluctuations (m) |

| Pj | Jet power input expended at the jet nozzle (Watts) |

| Q | Jet nozzle discharge flow rate (m3/s) |

| QE(zmax) | Jet entrainment Rate within the jet spread across the free jet path length (m3/s) |

| QT | Total volumetric flow rate of the bulk volume (m3/s) |

| Rej | |

| tm | Mixing time (s) |

| tc | Mean circulation time due to entrainment within the jet spread around zmax (s) |

| tR | Bulk fluid residence time (s) |

| t95 | 95% mixing time (s) |

| T | Tank diameter (m) |

| uj | Jet inlet velocity (m/s) |

| uz | Jet velocity at z (m/s) |

| V | Bulk fluid volume (m3) |

| XN | Jet nozzle clearance from the side wall (m) |

| z | Distance from the nozzle in the axis of the jet (m) |

| zmax | Free jet path length as the jet impinges on the liquid surface, side tank wall, or tank bottom (m) |

| Greek Symbols | |

| εj | Turbulent energy dissipation rate at the jet inlet (m2/s3) |

| εz | Turbulent energy dissipation rate at z (m2/s3) |

| Density (kg/m3) | |

| µ | Viscosity (Pa.s) |

| α | Jet nozzle vertical inclination (°) |

| αuL | Jet nozzle vertical inclination upper limit (°) |

| αLL | Jet nozzle vertical inclination lower limit (°) |

| β | Jet nozzle horizontal position (°) |

| δ | Fox and Gex correlation constant |

| φ | Circulation model constant |

References

- Wasewar, K.L.; Sarathi, J.V. CFD Modelling and Simulation of Jet Mixed Tanks. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2008, 2, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randive, P.S.; Singh, D.P.; Varghese, V.; Badar, A.M. Study of Jet Mixingin Flocculation Process. IJFMR-Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2018, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wasewar, K.L. A design of jet mixed tank. Chem. Biochem. Eng. Q. 2006, 20, 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Patwardhan, A.W.; Thatte, A.R. Process Design Aspects of Jet Mixers. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2008, 82, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, A. A review of effects of initial and boundary conditions on turbulent jets. WSEAS Trans. Fluid Mech. 2010, 4, 257–275. [Google Scholar]

- Tilton, J.N. Perry’s Chemical Engineers’ Handbook: Fluid and Particle Dynamics; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Patwardhan, A.; Gaikwad, S. Mixing in Tanks Agitated by Jets. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2003, 81, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabaret, F.; Rivera, C.; Fradette, L.; Heniche, M.; Tanguy, P. Hydrodynamics Performance of a Dual Shaft Mixer with Viscous Newtonian Liquids. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2007, 85, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, E.A.; Gex, V.E. Single-phase blending of liquids. AIChE J. 1956, 2, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okita, N.; Oyama, Y. Mixing Characteristics in Jet Mixing. Chem. Eng. 1963, 27, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, T.; Ban, Y.; Mizushina, T. Jet mixing of fluids in tanks. . J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 1982, 15, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revill, B.K. Chapter 9 - Jet mixing. In Mixing in the Process Industries; Harnby, N., Edwards, M.F., Nienow, A.W., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1992; pp. 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenville, R.; Tilton, J.N. March. In Turbulence for flow as a predictor of blend time in turbulent jet mixed vessels. In Proceedings of the Nineth European Conference on Mixing, Paris, France, 18–21 March 1997; pp. 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Grenville, R.K.; Tilton, J.N. A new theory improves the correlation of blend time data from turbulent jet mixed vessels. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 1996, 74, 390–396. [Google Scholar]

- Fossett, H.; Prosser, L.E. The Application of Free Jets to the Mixing of Fluids in Bulk. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. 1949, 160, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, A.G.C.; Rice, P. Comparative assessment of the performance of the three designs for liquid jet mixing. Ind. Eng. Chem. Process. Des. Dev. 1982, 21, 650–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenville, R.; Tilton, J. Jet mixing in tall tanks: Comparison of methods for predicting blend times. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2011, 89, 2501–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwadero, T.A.; Xuereb, C.; Aubin, J.; Poux, M. Effect of Jet Nozzle Position on Mixing Time in Large Tanks. 2023.

- Paul, E.L.; Atiemo-Obeng, V.A.; Kresta, S.M. Handbook of industrial mixing; Wiley-Blackwell: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 1–143. [Google Scholar]

- Orfaniotis, A.; Fonade, C.; Lalane, M.; Doubrovine, N. Experimental study of the fluidic mixing in a cylindrical reactor. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 1996, 74, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Fonade, C. Experimental study of mixing performances using steady and unsteady jets. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 1993, 71, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Vusse, J. Mixing by agitation of miscible liquids Part I. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1955, 4, 178–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perona, J.J.; Hylton, T.D.; Youngblood, E.L.; Cummins, R.L. Jet Mixing of Liquids in Long Horizontal Cylindrical Tanks. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1998, 37, 1478–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, J.P.; Delville, J.; Glauser, M.N.; Antonia, R.A.; Bisset, D.K.; Cole, D.R.; Fiedler, H.E.; Garem, J.H.; Hilberg, D.; Jeong, J.; Kevlahan, N.K.R. Collaborative testing of eddy structure identification methods in free turbulent shear flows. Exp. Fluids 1998, 25, 197–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FP Ricou and D., B. Spalding: J. Fluid Mech., Vol. 11, no. 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Corrsin, S. The isotropic turbulent mixer: Part, I.I. Arbitrary Schmidt number. AIChE J. 1964, 10, 870–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaratnam, N. Turbulent mixing and diffusion of jets. Encycl. Fluid Mechanics. 1986, 2, 391–405. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Symbol | Value (m) |

|---|---|---|

| Tank diameter | T | 0.780 |

| Liquid height | H | 0.390 |

| Nozzle diameter | dj | 0.003, 0.005, 0.0075 |

| Nozzle clearance from side wall | XN | 0.085 |

| Nozzle clearance from tank bottom | hN | 0.050 |

| Outlet clearance | hO | 0.192 |

| Vertical inclination of nozzle | α | 35°, 30°, 26°, 15°, 8°, 0°, 30° |

| Horizontal inclination of nozzle | β | 0°, 15°, 30°, 45°, 60° |

| α (°) | β (°) | dj (m) | zmax (m) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 0 | 0.005 | 0.093 | 0.32 |

| 15 | 0.005 | 0.093 | 0.31 | |

| 30 | 0.005 | 0.093 | 0.264 | |

| 45 | 0.005 | 0.093 | 0.193 | |

| 60 | 0.005 | 0.093 | 0.164 | |

| 15 | 0 | 0.0075 | 0.720 | 1.89* |

| 0 | 0.005 | 0.712 | 1.89* | |

| 0 | 0.003 | 0.707 | 1.89* | |

| 15 | 0.005 | 0.6930 | 2.06 | |

| 30 | 0.005 | 0.638 | 1.46 | |

| 45 | 0.005 | 0.552 | 1.10 | |

| 60 | 0.005 | 0.447 | 0.70 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0.005 | 0.688 | 1.89* |

| 8 | 0 | 0.005 | 0.694 | 1.89* |

| 26 | 0 | 0.005 | 0.766 | 1.89* |

| 30 | 0 | 0.005 | 0.673 | 1.89* |

| 35 | 0 | 0.005 | 0.585 | 1.89* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).