1. Introduction

The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (QTP) ranks as the highest plateau in the low-latitude areas around the world. It’s also been called the “third pole” for its high average elevation [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In terms of the global mid-latitude area, the QTP has the largest distribution of permafrost (~1.06 million km

2), which is defined as the rock or soil that remains at or below 0 ℃ for two or more consecutive years and it is a key component in the cryosphere [

5,

6,

7]. Due to its lower latitude and higher elevation, the permafrost on the QTP is more sensitive to climate change compared with permafrost in high altitude areas such as Canada and Russia [

8,

9]. The dynamic change of the frozen ground distribution under the background of global warming is of great importance for hydrology cycles, ecosystems, engineering infrastructure, and climate change [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Previous studies have reported that, as a result of global warming, the frozen ground on the QTP had warmed up in recent decades and the warming is more intense than the Arctic and similar mid-latitude regions[

14,

15]. Wu and Zhang [

16] monitored 10 boreholes in permafrost areas along the Qinghai-Tibetan Highway up to 10.7 m depth half-monthly from 1996 to 2006. They reported that the mean annual temperatures at 6.0 m depth have increased 0.12 ℃ to 0.67 ℃ with an average value of 0.43 ℃. Simultaneously, they conduct a further investigation on the active layer thickness and found that it increased sharply (about 39 cm) from 1983 to 2005 [

17]. To characterize the freezing and thawing states of the frozen ground, changes in near surface air freezing/thawing indices(AFI/ATI) and ground surface freezing/thawing indices (GFI/GTI) on the QTP have also been analyzed using in situ observations [

18]. The results show that the QTP has undergone a prominent increasing trend in thawing index while a decreasing trend in freezing index since 1998 [

19]. It is consistent with the pivotal year of 1998 when the QTP experienced dramatic wetting and warming thereafter [

20]. Climate warming also benefits the vegetation growth [

21,

22,

23,

24], and can induce a earlier start date of frozen through feedbacks to regional climates [

25]. Observational analysis further presented that the greening QTP can amplify the warming impact of spring snow cover on surface seasonally frozen ground (SFG), and also can intensify the warming effect of summer rainfall on top permafrost [

26]. These studies have shown us the uneven thermal responses of frozen ground to accelerated climate change and the vegetation growth on the QTP served as potential connections. Whereas owing to the complex terrains and harsh natural conditions, the monitoring sites are relatively sparse and a certain of uncertainties are also exists in the satellite products on the QTP, especially in the western high-altitude region [

27]. Consequently, studies on the changes of the thermal state of the frozen ground on the wetting and warming QTP are still spatially and temporally restricted and need further investigations.

Numerical simulation can be an appropriate method for expanding a site study to the regional and long-term time scales. Recently, considerable studies regarding thermal dynamics of frozen ground on the QTP have been conducted with the employment of numerical models [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Guo and Wang [

32] investigated the extent of permafrost degradation on the QTP using the Community Land Surface Model (CLM). The results indicated that the near-surface permafrost area decreased at a rate of 0.09×10

6 km

2/decade, and the area average active layer thickness increased by 0.15 m/decade from 1981 to 2010. It was projected that the shrinkage of permafrost area will exceed 58 % by the end of 21st century and most sustainable permafrost may only exists in the northwestern QTP [

9,

33]. Actually, the total area of thermally degraded permafrost is about 1.54×10

6 km

2 in history and the key period of degradation is from the 1960s to the 1970s and from the 1990s to the 2000s [

14]. Recent numerical experiment further reveals that winter warming has amplified the thermal degradation of permafrost after 2000 [

34]. These works extended the understandings of the thermal responses of frozen ground to climate warming. Whereas, temperature gradient transition between near-surface atmosphere and frozen ground in long-term time series and the associated thermal regimes dynamics in the context of climate change are still need further investigation because it is of great importance to reasonably project the changes of frozen ground on the QTP in the foreseeable future. Liu et al. [

6] analyzed the spatial and temporal variations of the air freezing/thawing indices and the ground surface freezing/thawing indices in the southwestern QTP from 1900 to 2017 prior to the dynamics of the frozen ground. The result suggests that these indices experienced abrupt changes around the 2000s consistently. It has been recognized that theses thermal changes in permafrost was influenced by air warming. Nonetheless, it also should be noted that the QTP underwent prominent wetting process since the late 1990s [

20,

35,

36], a super-heavy precipitation can cause dramatic rises in soil temperatures by 0.3 to 0.5 ℃ at shallow depths and advancement thawing of the active layer by half a month in permafrost region on the northeastern QTP [

37]. However, there still exist some uncertainties on thermal responses of permafrost and SFG to intensified wetting and warming conditions, when the occurrence of vegetation cover expansion across the QTP on a long run.

This study aims to characterize thermal dynamics in both permafrost and SFG regions on the QTP from 1961-2010 by investigating differences of freezing/thawing indices between near-surface atmosphere and ground surface in terms of temporal and spatial changes, based on a high resolution (0.05°×0.05°) simulation conducted by the Community Land Surface Model version 4.5 (CLM4.5). Decadal changes of frozen ground distribution on the QTP in the past decades were analyzed in advance. The reminder of this paper is organized as:

Section 2 describes the data and methods;

Section 3 presents the spatial patterns of frozen ground distribution, and the variations of freezing/thawing indices between atmosphere and ground surface in permafrost and SFG regions, respectively;

Section 4 provides a discussion between the ground surface freezing/thawing indices anomalies and the anomalies of air freezing/thawing indices, precipitation, and the vegetation cover conditions in the permafrost and SFG areas on the QTP, before the conclusions and an outlook are given in

Section 5.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.1.1. Land Surface Model Data

An atmospheric forcing dataset across the QTP including gridded near-surface temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, surface pressure, precipitation, and downward shortwave (longwave) radiation with a temporal-spatial resolution of 3 hourly and 5 km from 1961 to 2010 was used to force the land surface model (

http://globalchange.bnu.edu.cn/research/forcing). The forcing fields are generated through a new proposed approach based on observations collected at approximately 700 stations on mainland China. Before it was released by the Beijing Normal University (China, hereafter BNU), the reasonability of the dataset has been validated through comparisons of the corresponding components with the National Centers for Environmental Prediction Climate Forecast System Reanalysis dataset and the Princeton meteorological forcing dataset [

38]. Moreover, the reliabilities of air temperature and precipitation components of the dataset have also been confirmed using the observational records on the QTP, prior the numerical simulation [

39]. Additionally, the in-situ observations across the QTP also confirmed the simulation ability of the CLM4.5 to reproduce the soil temperature values in a long run [

36,

39], which were used to calculate the ground freezing/thawing indices (GFI/GTI) in this study. Meanwhile, the air freezing/thawing indices (AFI/ATI) presented in this study were also calculated using the near-surface (2 m above the ground) atmospheric temperatures derived from this data set.

2.1.2. Remote Sensing Data

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) from July 1981 to December 2015 was used to characterize vegetation cover condition across the QTP. It is the latest release of the long sequence product of NOAA Global Inventory Monitoring and Modeling System (GIMMS), version 3g.v1. The temporal resolution of the NDVI is half a month and the spatial resolution is 0.08°×0.08°, respectively. It is the classic dataset used to detect vegetation dynamics, as well as their influences on thermal regimes of frozen ground across the QTP [

40]. The data set is available on the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (

https://data.tpdc.ac.cn).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Freezing/thawing indices

In this study, freezing/thawing indices were calculated using accumulated monthly air temperature or ground surface temperature of numerical outputs [

41,

42]. The AFI and GFI can be conceptualized as the accumulated near-surface air temperature (2 m above the ground) and ground surface temperature (4.51 cm under the ground) in the whole freezing period from 1 July to 30 June in the next year. Similarly, the ATI and GTI are the sum of the air and ground surface temperatures with positive mean monthly values in a whole thawing period from 1 January to 31 December within a calendar year [

4,

14,

24]. Specific equations are shown as follows:

where FI and TI (℃d) are freezing and thawing indices which calculated by mean monthly temperatures (T

i , near-surface atmosphere or ground surface), respectively; D

i is the number of days in ith month; M

F and M

T represent months with negative and positive mean monthly values in near-surface air temperature or ground surface temperature.

2.2.2. Surface frost index

To estimate the frozen ground distribution in each decade, the surface frost index, which has been validated to capture permafrost distribution reasonably on the QTP [

24,

30,

31], was calculated and used to diagnose permafrost. In this study, the boundary of permafrost is determined by the ground surface freezing index and thawing index:

where F is a parameter to diagnose permafrost and the superscript of GFI represents adjustment for the effects of snow cover [

32]. The value of F ranges from 0.50 to 0.60 indicates sporadic permafrost, 0.60 to 0.67 indicates extensive permafrost, and above 0.67 indicates continuous permafrost [

33]. A threshold value of 0.58 was taken to estimate the absence or presence of permafrost in this study as it was deemed as an appropriate value to present the observed permafrost area [

33] and also matches the new map of permafrost distribution on the QTP well [

34].

2.2.3. Statistical analysis method

The modified Mann-Kendall (MMK) trend and Sen’s slope estimator methods were applied in this study to detect the tendencies and estimate the trends of variations in freezing and thawing indices across the QTP. The two nonparametric methods have been widely used to conduct statistical diagnosis in climate analysis studies and detailed description about these methods can be found in previous study [

35].

2.2.4. Model and numerical simulation design

The Community Land Surface Model version 4.5 (CLM 4.5) was used in this study to obtain the essential monthly air and ground surface temperature to calculate freezing/thawing indices across the QTP. As the land component of the Community Climate System Model and the Community Earth System Model, CLM 4.5 simulates the partitioning of mass and energy from the atmosphere, redistributes the mass and energy of the land surface, and then exports the fresh water and heat to the oceans [

36]. Previous studies have confirmed the simulation ability of CLM in different spatial scales on the QTP [

37,

38]. In this study, the CLM4.5 was driven by the BNU dataset and the numerical simulation was conducted at a spatial resolution of 0.05°×0.05° across the QTP. The outputs were set to a monthly step from 1961 to 2010. It is important to state that reliabilities of the simulated soil temperature and moisture have been validated with station records and in situ observations across the QTP in preceding works [

24,

27].

3. Results

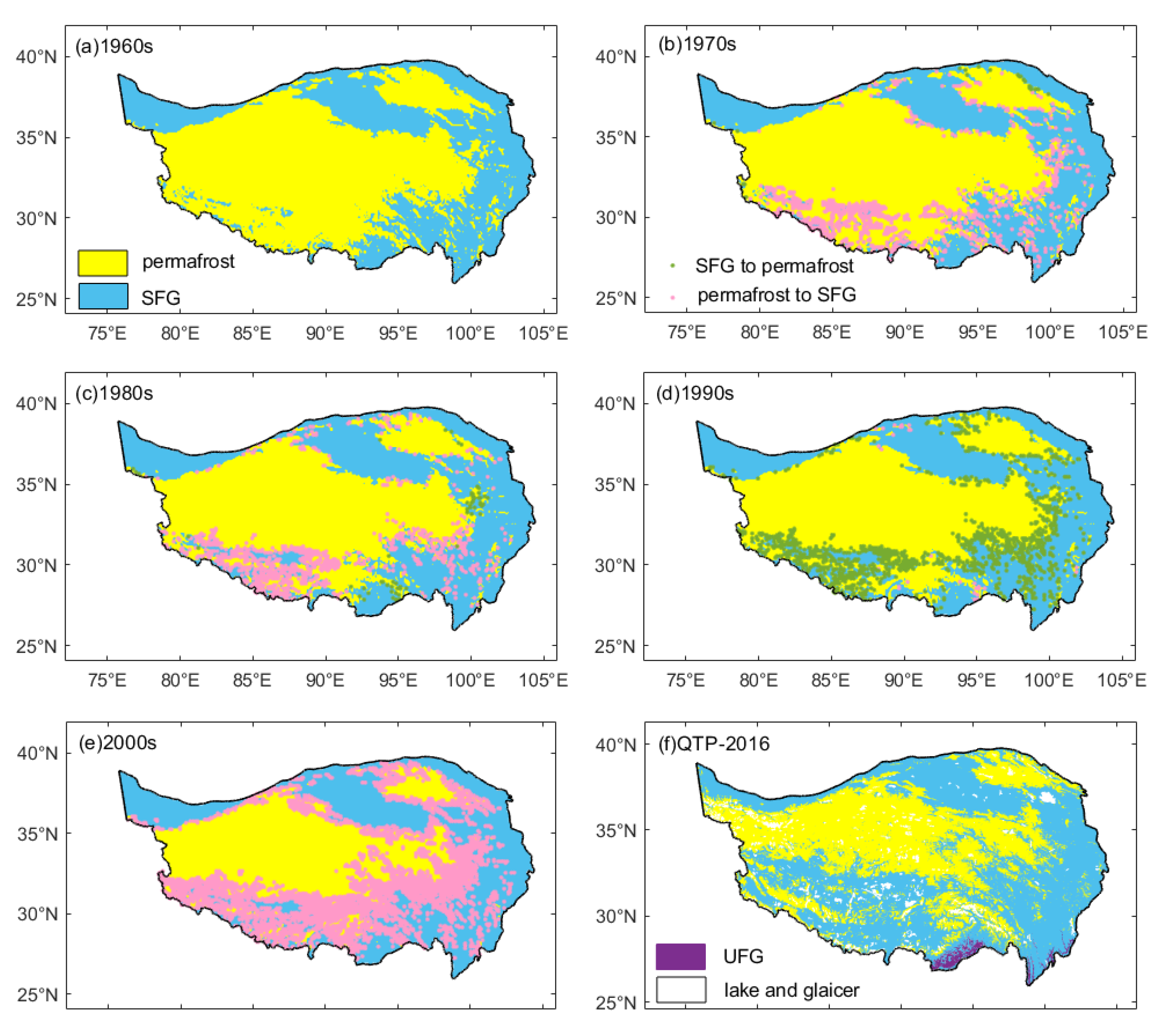

3.1. Decadal changes of permafrost distribution on the QTP from 1961 to 2010

The spatial patterns of frozen ground distribution in each decade from 1961 to 2010 across the QTP are presented in

Figure 1. Meanwhile, an new map of permafrost distribution on the QTP, which mapped permafrost, SFG, and unfrozen ground based on remote sensing land surface temperature products from 2009 to 2014 (

Figure 1f, hereafter as QTP-2016), is also included and can serve as a contrast benchmark [

34]. It is obvious that the conversion between permafrost and SFG mostly occurred around the rims of mountainous permafrost areas on the southwestern QTP and the sporadic permafrost regions on the eastern QTP during 1970s to 1980s. Statistically, the permafrost area shrunk from 1.62×10

6 km

2 to 1.40 ×10

6 km

2 in 1960s-1980s (

Table 1), which mainly concentrated in the Tanggula Mountain and Hengduan Mountain areas (

Figure 1b,c). The significant decreases in the AFI occurred in 1980s, which implies the occurrence of dramatic warming of air temperature over the entire QTP in frozen season during this decade. The air warming over permafrost region was also detected in thawed season, evidenced by the increased rate of 0.65 ℃·d/decade in the ATI. The prominent atmospheric warming seems caused the permafrost degradation (6.67 % reduction in area) and the thermal unstable in SFG, where the GFI decreased significantly (11.73 ℃·d/decade). Furthermore, we noticed that the GTI showed an opposite decreasing trend in permafrost areas, even through the increasing ATI (also air warming in thawed season) in 1980s. It suggests that the top permafrost shown less thermal responses within the active layer during thawing process in 1980s, and the intensified air warming in frozen season was more favorable for the remarkable shrinkage of permafrost area during this period.

The QTP has experienced obvious permafrost expansion in 1990s (0.13×10

6 km

2), after the pronounced shrinkage of permafrost area in 1980s.

Figure 1d shows that the conversions from SFG to permafrost mostly occurred in the central QTP, known as Qiangtang High Plain, as well as the Yarlung Zangbo River in the southwestern QTP. However, the AFI and the ATI in permafrost areas show decreasing and increasing trends with rates of 6.93 ℃·d/decade and 1.17 ℃·d/decade, respectively (

Table 1), implying that the atmosphere over permafrost regions exhibited warming changes in both frozen and thawed seasons in 1990s. These results indicate that air warming does not always declines the permafrost area, because of the active layer presented shortens in freezing (5.55 ℃·d/decade) and thawing (4.09 ℃·d/decade) periods. Zhang et al. [

15] reported that the Qiangtang High Plain has experienced the most intensively precipitation increase from 1998 and it exerted a cooling effect on the top permafrost regions by reducing their thermal responses to climate change. Based on these results, we can conclude that precipitation may also play an important role on declining the freezing and thawing intensities within the active layer, thus favoring the permafrost development in 1990s despite under the background of air warming.

Table 1 presented that the permafrost area grew in 1990s and dropped to a new low in 2000s, with a minimum value of 1.02×10

6 km

2.

Figure 1d shows that the conversions from permafrost into SFG was prevailing across the entire QTP, especially in the southern QTP. The shortens of freezing and thawing duration in active layer in the 1990s is likely to cause permafrost more vulnerable to climate change, which coincides with previous results [

39]. Our results indicated that, in contrast to 1990s, an area counting 33.33 % of permafrost on the QTP thawed into SFG in 2000s. While the AFI increased and the ATI decreased at rates of 13.37 ℃·d/decade and 6.41 ℃·d/decade, respectively, in permafrost regions during this decade (

Table 1). It illustrates that the QTP has undergone a warming hiatus during 2000s as the period of air temperature below (above) 0 ℃ extended (shortened) in frozen (thawed) season. SFG also exhibited increasing trend in the GFI and decreasing one in the GTI, followed the variations in the AFI and ATI. However, the variations in the ATI and the GTI shown an opposite direction in the permafrost parts in 2000s. The temperature of top permafrost above 0 ℃ lasted longer while the atmospheric temperature exceeds 0 ℃ lasted shorter, evidenced by the increasing rate of 10.98 ℃·d/decade in the GTI and the decreasing rate of 6.41 ℃·d/decade in the ATI (

Table 1). The warming hiatus in the thawed has not restrained the thermal degradation in permafrost regions in 2000s.

As a whole, the QTP witnessed a prominent permafrost shrinkage in 1960s-2000s, accounting for 37.04 % of permafrost area in 1960s. The most pronounced decline in permafrost area took place in 2000s, when QTP was undergoing a warming hiatus. From the perspective of surface freeing/thawing process, the frozen ground were thermally unstable in 1980s owing to the strikingly atmospheric warming in frozen season. The dramatic thermal degradation in 2000s, which might be due to the accelerated wetting process over the QTP, mainly occurred in permafrost regions in the thawed season. This differs from that in the 1980s. Despite recent studies have confirmed the intensified summer precipitation has exerted important warming effect on permafrost body [

15,

24,

25], our results further reveal that thermal degradation also terminated in SFG in the 2000s. Relative warmer and wetter conditions in SFG regions might experience more heat loss via evaporation when gradual plentiful water occupies in soil pores , which alters the thermal regimes of surface ground [

24].

3.2. Comparisons of thermal states between near-surface atmosphere and ground surface in climatology

The GFI and GTI across the QTP shows similar spatial patterns with the AFI and ATI, respectively (

Figure 2). From the perspective of value, the climatology of the GTI (GFI) is higher (lower) than that of the ATI (AFI), especially for the permafrost regions. The maximum value of the ATI is 1505.80 ℃d, which is substantially lower than that of the GTI (2485.06 ℃d). While the maximum AFI reaching the value of 2042.24 ℃d, higher than that of the GFI (1463.06 ℃d) for the entire QTP. It implies that, in general, period of ground temperature above 0 ℃lasted longer than air temperature in thawed season, while air temperature below 0 ℃ retained longer than ground surface temperature in frozen season in past decades. The maximum values of the averaged annual ground surface temperature is 3.44 ℃, more than five times the value of air temperature (-0.61 ℃,

Figure 2c,f).

Spatially, the spatial patterns for the AFI and GFI, ATI and GTI in climatology show distinctive regional differences (

Figure 2). It was found that in contrast to the GFI, permafrost and SFG tend to show more pronounced distinctions in the GTI during 1961 to 2010 with values of 1267.83 ℃d. However, the differences of the AFI between permafrost and SFG is 1298.38 ℃d, which is comparable to the value of 1222.01 ℃d in the ATI. It shows apparent distinctions of permafrost and SFG responses to climate change in terms of thawing intensities. Dramatic higher differences between the AFI and the GFI in permafrost regions suggests more pronounced freezing intensity in permafrost regions. Conversely, the differences between the ATI and GTI are more remarkable in SFG parts, which illustrates that SFG are more vulnerable to thawing when air temperature increasing. However, owing to the wetting and warming conditions over the QTP, the decreased cold stress in high altitude parts of the QTP encouraged expand climatically suitable areas for plants growth towards higher elevations [

40]. Accompanied by air temperature and precipitation changes in long time series, it could exert substantial impacts on regulating the thermal regimes of the surface permafrost. As one of typical characteristics of land surface process in high altitude parts of the QTP, alpine permafrost are also not immune to these impacts.

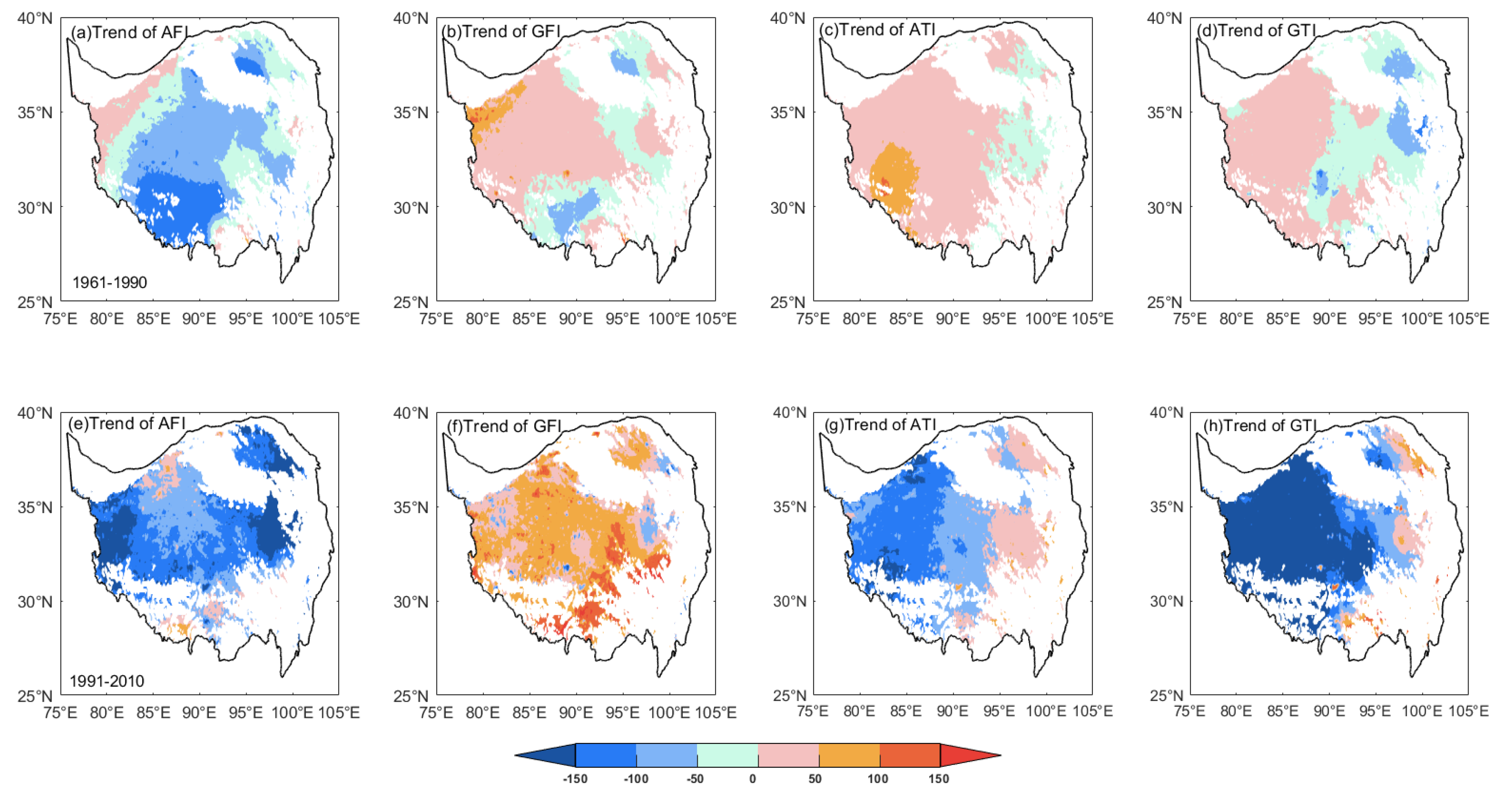

3.3. Spatial changes of freezing and thawing indices in permafrost and seasonally frozen ground

As the 1990s represent the pivotal period of permafrost area variations and freezing/thawing indices dynamics, the spatial patterns of changes in the AFI and GFI, the ATI and GTI in permafrost and SFG regions before and after the 1990s are shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, respectively. Before the 1990s, the changes of AFI in permafrost regions were dominated by negative values, which illustrates the air warming during the frozen season (

Figure 3a). Meanwhile, persistent negative trends of the GFI in Qilian Mountains, Tanggula Mountains and parts of Qiangtang High Plain in the interior QTP, indicating these surface permafrost areas have warmed substantially, broadly consistent with dynamics of permafrost distribution during in these decades (

Figure 1b,c). It can be well explained that the increased air temperature, which has been widely recognized to control thermal regime changes in recent studies [

14,

22,

23], has triggered the thermal regimes changes of the underlying permafrost. However, it should also be emphasized that the major Qiangtang High Plain in the western QTP exhibited prominent increases in the GFI, where the frozen duration maintained longer within the surface active layer. It appears that the air warming before the 1990s in frozen season only induced thermal unstable in some small portions of surface permafrost. Statistically, in contrast to the decreasing trend of the AFI (13.59 ℃·d/decade) from 1961 to 1990, the annual GFI in permafrost regions was growing at a rate of 67.59 ℃·d/decade (

Table 2). Meanwhile, positive-dominated changes in the ATI before the 1990s have consistently showed that the QTP has experienced prevalent warming process in thawed season, except for some portions in the sporadic permafrost regions in Hengduan Mountains and Qilian Mountains where negative trends were present (

Figure 3c).

Table 2 demonstrated that the ATI increased significantly at a rate of 39.86 ℃·d/decade during 1961-1990. While the GTI show pronounced spatial distinctions in terms of permafrost responses to warming. The eastern parts of the Qiangtang High Plain in the interior QTP exhibited decreased changes in the GTI. It implying that the thawed duration has a tendency to decline to some extent even through an accelerated warming process over the permafrost body. However, the western parts exhibit extended thawed duration as the responses of warming. Being different from the freezing process which releases heat to surroundings, the extension of thawing process with the surface ground might accompany with a certain amount of heat input from the surroundings. Positive changes in the GTI and the GFI consistently took place in the western parts of Qiangtang High Plain (

Figure 3b,d). The longer freezing duration and extended thawing times occurred in the top continuous permafrost regions tend to deepening the active layer, although the permafrost in these areas remained relatively stable in type before the 1990s (

Figure 1c).

In contrast to the slight decrease at a rate of 13.59 ℃·d/decade before the 1990s, the AFI started to decrease dramatically since the 1990s and reached a magnified value of 202.57 ℃·d/decade (

Table 2). However, the freezing duration within the surface active layer shown intensive extending tend, evidenced by the prevalent increased GFI in permafrost regions (

Figure 3f). This lies in contrast to the changes in AFI (

Figure 3e). The warming effect of increased air temperature shows less control role on thermal regimes in permafrost in frozen season during 1991-2010. Furthermore, spatial changes in the ATI also presented a reverse pattern after 1990. Most areas of the Qiangtang High Plain experienced a warming hiatus in thawed season. From the perspective of magnitude, the increasing rate of the ATI is 16.94 ℃·d/decade after 1990, which is substantially lower than that before 1990 (39.86 ℃·d/decade). It is shown that air warming in frozen season eventually exceeded that in thawed season after 1990. This corroborates with the findings of previous numerical experiments which reported that the summer warming has slowed and winter warming began to speed over the QTP around 1998 [

22]. Meanwhile, the ground surface, however, presented shortened thawing periods in the active layer of permafrost regions (

Figure 3h), with a rate of 83.58 ℃·d/decade in the GTI (

Table 2). Considering the relative milder increase in the ATI (16.94 ℃·d/decade), it can be reasonably concluded that the top permafrost was not particularly sensitive to the air warming since 1990s. Pronounced air warming had marginal effects on thermal regime changes in permafrost in frozen season.

Nevertheless, it was also found that QTP has also experienced dramatic wetting process around the 1998, and the remarkable greening process after 2000 which was favored by substantial climate change [

15,

18,

41]. Permafrost monitoring has indicated that intensified rainfall imposed a cooling effect in the frozen season and a warming effect in the thawed season in the active layer [

42], which has a pivotal impact on deepening the active layer thickness [

43]. Meanwhile, an expansion of climatically suitable areas for plants growth might favors the increasing impacts of vegetation on regulating the current thermal regimes of permafrost over the QTP [

18]. From these results, it can be reasonably inferred that variations in freezing/thawing indices after 1990 might also related to local variations in precipitation and vegetation cover dynamics in permafrost sections.

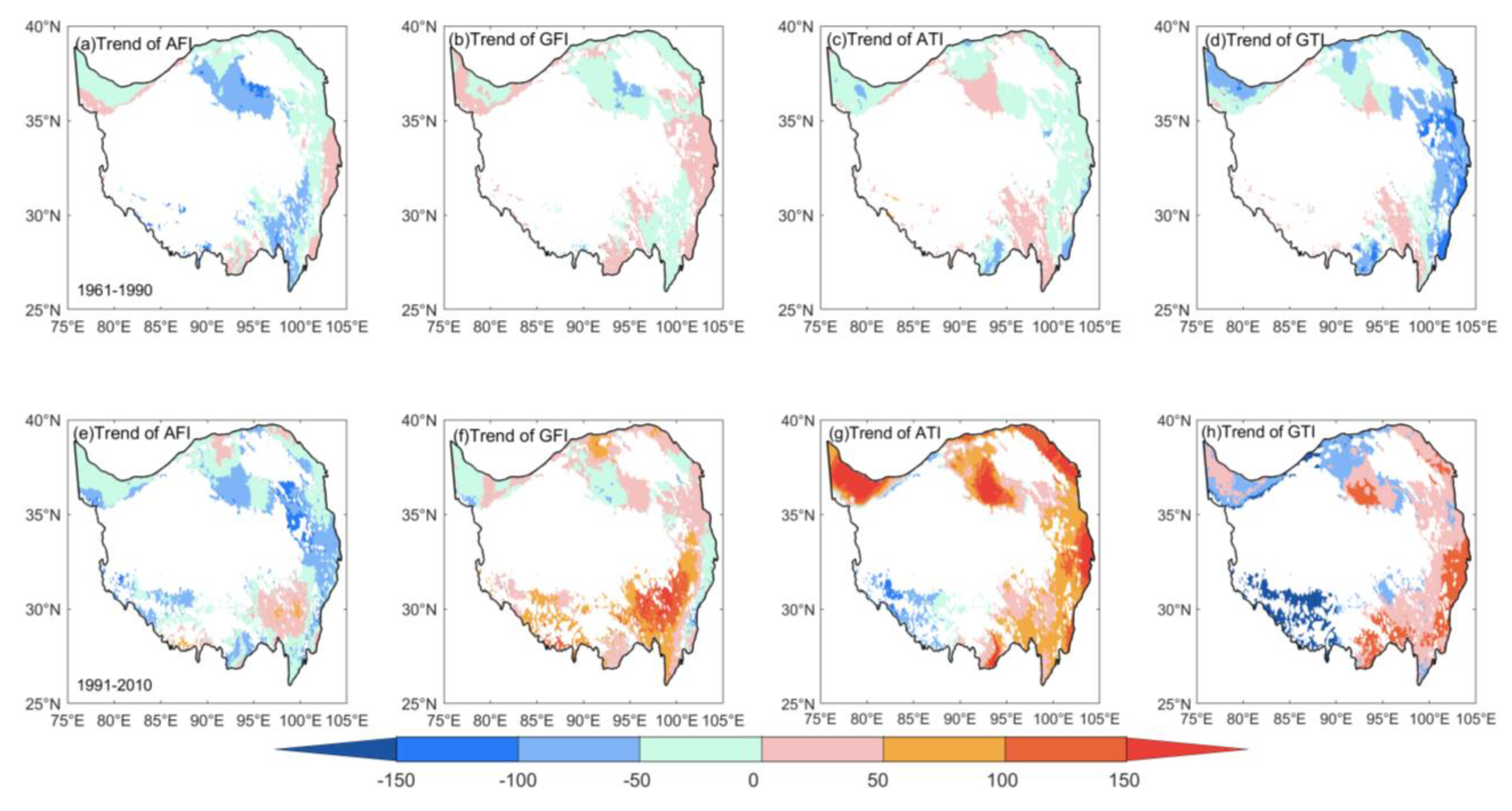

In SFG areas, the changes of AFI decreased significantly with the rates of 44.27 ℃·d/decade and 148.97 ℃·d/decade during the two subperiods, i.e., 1961-1990 and 1991-2010 (

Table 2). Spatially, the largest decreasing areas of the AFI expanded from the Qaidam Basin to the eastern parts of the QTP (

Figure 4a,e). The remarkable declines in the AFI indicate the near-surface atmosphere over the SFG has warmed substantially in the frozen season during the study period.

Figure 4b shows that the Qaidam Basin presented a prominent decreasing tendency in the GFI as responses of air temperature increase. However, some portions in the eastern QTP underwent cooling process where the GFI decreased. As a whole, the significant air temperature rise over the SFG has not exerted prominent warming effects on frozen surface ground before 1990s because of the GFI was increasing at a rate of 1.48 ℃·d/decade (

Table 2).

Whereas from 1991, the ground surface underwent obvious GFI decrease at a rate of 42.39 ℃·d/decade (

Table 2). While spatial patterns also indicate that SFG in the southeastern parts of the QTP also presented increases trends in the GFI (

Figure 4f). It is suggestive of diminishing thermal responses of SFG in these areas to air warming in frozen season since the 1990s. Moreover, distinct from freezing indices changes, the thawing indices changes show reversed patterns before and after the 1990s. It is clear that the SFG experienced progressively increases in the ATI after 1990 (

Figure 4g). Prominent increases in the GTI were correspondingly presented in the eastern QTP (

Figure 4h). While the southwestern QTP, where belongs the rims of the transitional areas between permafrost and SFG in 1990s-2000s (

Figure 1d,e), showed strikingly decreasing tendencies in the ATI and GTI (

Figure 4g,h). These results suggest that atmospheric warming over SFG after 1990 mainly occurred in thawed season, which differs from that in permafrost parts. The SFG degraded from permafrost in transitional areas tend to show less thermal responses to air warming in frozen season. A warming hiatus in thawed season might also favorable for permafrost development in these regions detected in 1990s (

Figure 1d).

4. Discussion

In this study, we compared the freezing/thawing indices between the near-surface atmosphere and frozen ground surface after presented the changes in frozen ground distribution, to fully characterize the effects of seasonal warming on frozen ground in the long run. The results indicate that air warming seems to show diminishing control role on thermal regimes in both permafrost and SFG areas since the 1990s when the occurrence of air warming shifted between frozen and thawed seasons. More specifically, after 1990, air temperature rise over permafrost was more pronounced in frozen season, while in thawed season, air warming over SFG exhibited more intensive increase. The warming hiatus over permafrost in thawed season and the prominent shrinkage of permafrost area in 2000s implies air warming seems to take a marginal controlling role on thermal regime changes.

As the occurrence of annual precipitation increase and the vegetation cover extension especially in 2000s [

4,

15,

18,

40], it is essential to investigate the effects on reregulating surface thermal regimes of frozen ground. Focused on a single precipitation event on the QTP, Li et al. [

42] reported that increased rainfall created a heating effect on active layers in thawed season, however, leads to a cooling effect in the frozen season. Moreover, recent observational results reveal that increases in vegetation greenness act as a promote role of SFG responses to highly wetting process from 1998 [

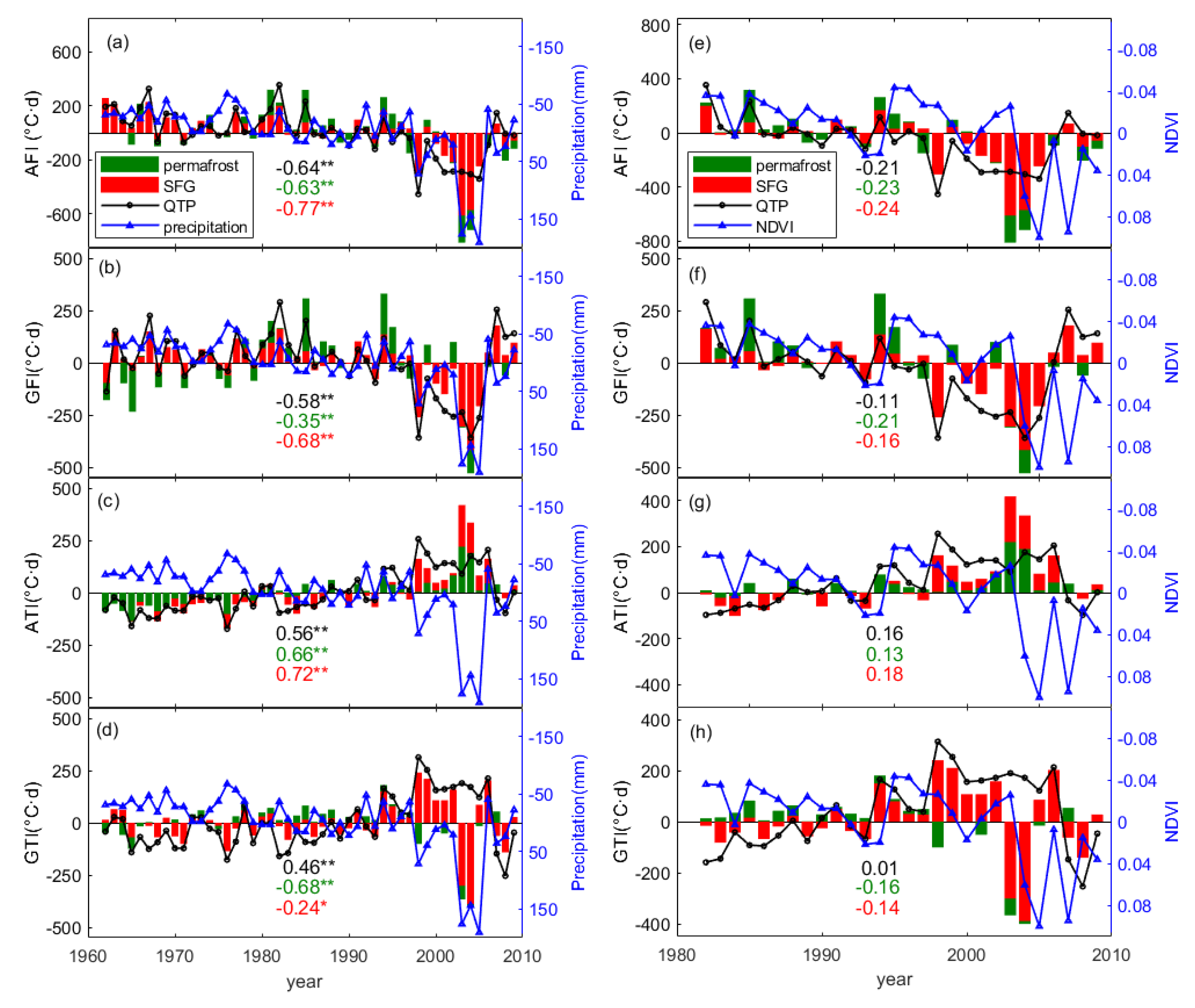

18]. In this study, we further deepened the investigation in perspective of changes in ground freezing and thawing indices response to those in atmospheric freezing and thawing indices on the entire QTP, on the base of analysis in frozen ground distribution changes for five decades. To state the conclusions more reasonably, we also presented the relations between freezing/thawing indices and precipitation, the NDVI across the QTP, respectively, in the

Figure 5.

It is obvious that the precipitation anomaly over the QTP has experienced a first peak in 1998 and rose to a new high in 2005 with the value of 191.10 mm. This corroborates with the findings in the previous numerical study [

15]. Negative anomaly in the AFI and positive anomaly in the ATI across the QTP reaching the maximum of 453.72 ℃·d/decade and 255.90 ℃·d/decade in 1998 consistently, suggesting that the QTP has undergone the most progressively atmospheric warming in frozen and thawed seasons in 1998. The GFI anomaly generally follow the evolution of the AFI anomaly until 2001. After that, the GFI reaching a new minimum anomaly of 359.79 in ℃·d/decade in 2004, whereas the AFI anomaly kept stable. Furthermore, the ATI showed weakened but stable positive anomalies during 2001-2005, while the GTI presented strikingly negative ones during this period, especially in the permafrost regions (

Figure 5c,d). These results suggest that the ground thawing duration shortened sharply even through air temperature rose. Instead, the intensified precipitation seems to act as a control role on regulating surface thermal regimes. Statistical results indicate that precipitation anomaly yields negative correlation relationships with the AFI and GFI significantly (p<0.05,

Figure 5a,b). The increased rainfall has a tendency to promote the air temperature rise and accelerate permafrost degradation in frozen season in the context of wetting and warming. However, in thawed season, sharp increase in precipitation tends to reduce ground thawing indices and exerts an obvious cooling effect on permafrost body. This conclusion is coincident with the work of Luo et al. [

25], which conducted based on permafrost monitoring in the northeastern QTP.

It is important to note that the NDVI started to increase in 2004 and reached a maximum value of positive anomaly (0.10) in 2005. As shown in

Figure 5, the NDVI anomaly yields negative correlation relationship with the AFI anomaly while positive one with the ATI anomaly, although they are not statistically significant. It implies the shortened periods of air temperature below zero in frozen season and the extended ones above zero in thawed season are favorable for vegetation cover expansion. For the frozen ground, positive anomaly in the NDVI will also encourage thermally unstable as its negative correlation relationship with the GFI and the GTI, respectively, especially in the permafrost regions. Rapid greening in 2001-2005 is coincident with the accelerated wetting over the QTP, might intensified the warming effect of increased precipitation on permafrost in frozen season. As a result, these results suggest that the dramatic permafrost shrinkage and thermal degradation across the QTP in the 2000s does not always only induced by air warming, intensive wetting and greening process over the QTP also played important roles. Further research into the influences of vegetation growth on thermal regime changes in different altitude ranges of the QTP in the context of warming and wetting is also required in the near future.

5. Conclusions

Based on the numerical simulation results, this study analyzed the thermal dynamics of frozen ground in a new perspective of comparing freezing and thawing indices between frozen ground and near-surface atmosphere, after changes in frozen ground distribution are investigated in each decade. The main conclusions are as following:

The net shrinkage of permafrost area in 2000s is 37.04 % relative to 1960s across the QTP. The permafrost area rose in 1990s and dropped to a new low in 2000s with the value of 1.02×106 km2. Decadal permafrost distribution patterns indicate the first occurrence of degradation lies in the Tanggula Mountain areas on the southwestern QTP in 1970s-1980s. And then, permafrost in Qilian Mountain areas in the northwestern QTP and the Hengduan Mountain in the interior QTP undergone pronounced reduction in areas in 2000s.

Atmosphere warming over the QTP seems to be play a control role on thermal dynamics of frozen ground before 1990s. The air warming achieving a peak in 1998 in both frozen and thawed seasons. The anomalies of GFI and GTI also reaching maximum in 1998, with values of 359.12 ℃·d and 313.32 ℃·d. Thermal regimes of permafrost and SFG generally followed the air temperature rise until the end of 1990s.

A warming hiatus was detected over the QTP in 2000s, especially for the permafrost regions in frozen season, which should favorable to restrain the permafrost degradation. While the QTP has undergone prominent thermally unstable in this decade, with the permafrost area shrunk by 33.33 %. The occurrence of increased precipitation over the QTP seems to take a control over permafrost degradation. The expanded vegetation cover exerts promote effect on thermal responses of frozen ground to climate change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.F.; methodology, X.F.; software, A.W. and C.C; validation, X.F.; formal analysis, X.F. and A.W.; investigation, X.F.; resources, X.F., S.L.; data curation, X.F.; writing-original draft preparation, X.F.; writing-review and editing, X.F. and K.F., visualization, X.W. and A.W.; supervision, X.F.; project administration, X.F. and S.L.; funding acquisition, X.F. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded jointly by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41905008, 41975007, 42275080) and the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students of Chengdu University of Information Technology (202210621006, 202210621003).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to the reviewers who provide valuable suggestions and supportive comments which are favor to improve the quality of the manuscript. And, also to the Max Planck Institute of Meteorology (Atmosphere in the Earth System) for providing hospitality combined with an excellent working environment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, D.; Qiu, G.; Li, S. Geocryology in China. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2001, 33, 245. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.; Ye, B.; Zhou, D.; Wu, B.; Foken, T.; Qin, J.; Zhou, Z.; Oppenheimer, M.; Yohe, G. Response of hydrological cycle to recent climate changes in the Tibetan Plateau. Climatic Change. 2011, 109, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Thompson, L.; Mosbrugger, V.; Zhang, F.; Ma, Y.; Luo, T.; Xu, B.; Yang, X.; Joswiak, D,; Wang, W. ; et al. Third Pole Environment (TPE). Environ. Dev. 2012, 3, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Guo, X.; Li, X.; Niu, X.; Yang, X.; Feng, M.; Che, T.; Jin, R.; Ran, Y.; Guo, J, et al. National Tibetan Plateau Data Center: Promoting Earth System Science on the Third Pole. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2021, 102, E2062–E2078. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, D.; Zhao, L.; Sheng, Y.; Chen, J.; Cheng, G. A new map of permafrost distribution on the Tibetan Plateau. Cryosphere. 2017, 11, 2527–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Luo, D.L.; Wang, L.; Huang, Y.D.; Chen, F.F. Dynamics of freezing/thawing indices and frozen ground from 1900 to 2017 in the upper Brahmaputra River Basin, Tibetan Plateau. Adv. Clim. Chang. Res. 2021, 12, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobinski, W. Permafrost. Earth. Sci. Rev. 2011, 108, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cheng, G. A GIS-aided response model of high-altitude permafrost to global change. Sci. China Earth Sci. 1999, 42, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Wang, H. CMIP5 permafrost degradation projection:A comparison among different regions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2016, 121, 4499–4517. [Google Scholar]

- Schuur, E.; Vogel, J.G.; Crummer, K.G.; Lee, H.; Sickman, J.O.; Osterkamp, T.E. The effect of permafrost thaw on old carbon release and net carbon exchange from tundra. Nature. 2009, 459, 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Jin, H. Permafrost and groundwater on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and in northeast China. Hydrogeol J. 2012, 21, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Wu, T. Responses of permafrost to climate change and their environmental significance, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Geophys. Res. Earth. Surf. 2007, 112, F2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Guo, J.; Han, B.; Sun, Q.; Liu, L. The effect of climate warming and permafrost thaw on desertification in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Gepmorphology. 2009, 108, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Y.; Li, X.; Cheng, G. Climate warming over the past half century has led to thermal degradation of permafrost on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Cryosphere. 2018, 12, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Bao, Q.; Hoskins, B.; Wu, G.; Liu, Y. Tibetan Plateau warming and precipitation changes in East Asia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, L14702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, T. Recent permafrost warming on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008, 113, D13108. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, T. Changes in active layer thickness over the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau from 1995 to 2007. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2010, 115, D09107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauenfeld, O.W.; Zhang, T.; Mccreight, J.L. Northern Hemisphere freezing/thawing index variations over the twentieth century. Int. J. Climatol. 2010, 27, 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Qin, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, R.; Zou, D.; Xie, C. Spatiotemporal changes of freezing/thawing indices and their response to recent climate change on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau from 1980 to 2013. Theor App Climatol. 2018, 132, 1187–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Nan, Z.; Zhao, L.; Liang, Y.; Cheng, G. Qinghai-Tibet Plateau wetting reduces permafrost thermal responses to climate warming. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2021, 31, 916–930. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Guo, C.; Degen, A.A.; Ahmad, A.A.; Wang, W.; Zhang, T.; Li, W.; Ma, L.; Huang, M.; Zeng, H. Climate Warming Benefits Alpine Vegetation Growth in Three-River Headwater Region, China. Sci.Total Environ. 2020, 742, 140574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cai, D.; Fraedrich, K.; Sielmann, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, X.; Guo, S.; Guan, Y. Vegetation Dynamics on the Tibetan Plateau (1982-2006); An Attribution by Ecohydrological Diagnostics. J. Clim. 2015, 28, 4576–4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, F.; Zhang, G.; Barlage, M.; Gan, Y.; Xin, X.; Wang, C. Impacts of Land Cover and Soil Texture Uncertainty on Land Model Simulations Over the Central Tibetan Plateau. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2018, 10, 2121–2146. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, L. , Ma, Y.; Salama, M.S.; Su, Z. Assessment of vegetation dynamics and their response to variations in precipitation and temperature in the Tibetan Plateau. Climatic Change. 2010, 103, 519–535. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wu, C.; Wu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ran, Y. Modeling the start of frozen dates with leaf senescence over Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 281, 113258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, C.; Wang, Z.; Lyu, S.; Fraedrich, K. Changes of timing and duration of the ground surface freeze on the Tibetan Plateau in the highly wetting period from 1998 to 2021. Climatic Change. 2023, 176, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Li, R.; Luan, L.; Lyu, S.; Zhang, T.; Ao, Y.; Han, B.; Zhao, L.; Ma, Y. Detecting hydrological consistency between soil moisture and precipitation and changes of soil moisture in summer over the Tibetan Plateau. Climate Dyn. 2018, 51, 4157–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Wu, T.; Zhao, L.; Wu, X.; Li, R.; Xie, C.; Pang, Q.; Hu, G.; Qiao, Y.; Zhao, G. Numerical Modeling of the Active Layer Thickness and Permafrost Thermal State Across Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2017, 122, 11604–11620.

- Li, D.; Chen, J.; Meng, Q.; Liu, D.; Fang, J.; Liu, J. Numeric simulation of permafrost degradation in the eastern Tibetan Plateau. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 2008, 19, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Nelson, F.E.; Shiklomanov, N.I.; Guo, D.; Wan, G. Permafrost degradation and its environmental effects on the Tibetan Plateau: A review of recent research. Earth Sci. Rev. 2010, 103, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wang, X.; Pang, G.; Wan, G.; Liu, Z. The Tibetan Plateau cryosphere: Observations and model simulations for current status and recent changes. Earth Sci. Rev. 2019, 190, 353–369. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, D.; Wang, H. Simulation of permafrost and seasonally frozen ground conditions on the Tibetan Plateau, 1981-2010. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 5216–5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Niu, F.; Lin, Z.; Luo, J.; Liu, M. Data-driven spatiotemporal projections of shallow permafrost based on CMIP6 across the Qinghai‒Tibet Plateau at 1 km2 scale. Adv. Climate Change Res. 2021, 12, 814–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Nan, Z.; Wu,X. ; Ji, H.; Zhao, S. The Role of Warming in Permafrost Change Over the Qinghai‒Tibet Plateau. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 11261–11269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Hu, G.; Zou, D.; Wu, X.; Ma, L; Sun, Z. ; Yuan, L.; Zhou, H., Liu, S. Permafrost changes and its effects on hydrological processes on Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2019, 34, 1233–1246. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Li, Z.; Cheng, C.; Fraedrich, K.; Wang, A.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Lyu, S. Response of freezing/thawing indexes to the wetting trend under warming climate conditions over the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau during 1961-2010: A Numerical Simulations. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 40, 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, D.; Jin, H.; Bense, V.F.; Jin, X.; Li, X. Hydrothermal processes of near-surface warm permafrost in response to strong precipitation events in the Headwater Area of the Yellow River, Tibetan Plateau. Geoderma. 2020, 376, 114531. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Zheng, X.; Dai, Y.; Yang, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wu, G.; Wang, Z.; Huang, C.; Shen, Y.; et al. Mapping near-surface air temperature, pressure, relative humidity and wind speed over Mainland China with high spatiotemporal resolution. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2014, 31, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Luo, S.; Lyu, S.; Cheng, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S. Numerical modeling of the responses of soil temperature and soil moisture to climate change over the Tibetan Plateau. 1961–2010. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, 4134–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzon, J.E.; Tucker, C.J. A Non-Stationary 1981-2012 AVHRR NDVI3g Time Series. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 6929–6960. [Google Scholar]

- Klene, A.E.; Nelson, F.E.; Shiklomanov, NI; Hinkel, K. M. The N-factor in natural landscapes: variability of air and soil-surface temperatures, Kuparuk River Basin, Alaska, U.S.A. Arct. Antarct. Apl. Res. 2001, 38, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Jin, H.; Marchenko, S.S; Romanovsky, V.E. Difference between near-surface air, land surface and ground surface temperatures and their influences on the frozen ground on the Qinghai-Tibe Plateau. Geoderma. 2018, 312, 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Jin, S.; Wu, Z.; Cui, Y. Evaluation and Application of the Estimation Methods of Frozen (Thawing) Depth over China. Adv. Earth Sci. 2009, 24, 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Change, Y.; Lyu, S.; Luo, S.; Li, Z.; Fang, X.; Chen, B. , Li, R.; Chen, S. Estimation of permafrost on the Tibetan Plateau under current and future climate conditions using the CMIP5 data. Int. J. Climatol. 2018, 38, 5659–5676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisinov, O.A.; Nelson, F.E. Permafrost distribution in the Northern Hemishpere under scenarios of climatic change. Glob. Planet. Change. 1996, 14, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, A.G.; Lawrence, D.M. Diagnosing Present and Future Permafrost from Climate Models. J. Clim. 2013, 26, 5608–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Zhao, L.; Sheng, Y.; Chen, J.; Hu, G.; Wu, T.; Wu, J.; Xie, C.; Wu, X.; Pang, Q. , et al. A new map of permafrost distribution on the Tibetan Plateau. Cryosphere. 2017, 11, 2527–2542. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Luo, S.; Lyu, S. Observed soil temperature trends associated with climate change in the Tibetan Plateau, 1960–2014. Theor App Climatol. 2019, 135, 169–181. [Google Scholar]

- Swenson, S.; Lawrence, D. A new fractional snow-covered area parameterization for the Community Land Model and its effect on the surface energy balance. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2012, 117, D21107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Wang, H. Simulated change in the near-surface soil freeze/thaw cycle on the Tibetan Plateau from 1981 to 2010. Chinese Sci. Bull. 2014, 59, 2439–2448. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Luo, S.; Lyu, S.; Chen, B.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, D.; Chang, Y. A Simulation and Validation of CLM during Freeze-Thaw on the Tibetan Plateau. Adv. Meteorol. 2016, 2016, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Wang, C. Water storage effect of soil freeze-thaw process and its impacts on soil hydro-thermal regime variations. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 265, 280–294. [Google Scholar]

- Lamsal, P.; Kumar, L.; Shabani, F.; Atreya, K. The greening of the Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau under climate change. Glob. Planet. Change. 2017, 159, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, X.; Leung, L.R.; Chen, D.; Xu, J. Aridity changes in the Tibetan Plateau in a warming climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 034013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wen, Z.; Cheng, Q.; Xing, A.; Zhang, M; Li, A. Thermal dynamics of the permafrost active layer under increased precipitation at the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Mt. Sci. 2019, 16, 309–322. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Zhao, L.; Li, R.; Wang, Q.; Xie, C.; Pang, Q. Recent ground surface warming and its effects on permafrost on the central Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Int. J. Climatol. 2013, 33, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Simulated spatial distribution of frozen ground types in (a) 1970s (b) 1980s (c) 1990s (d) 2000s (e) 2010s, against the (f) new map of permafrost distribution on the QTP (QTP-2016). The yellow, navy blue, purple, and white colors represent the areas of permafrost, seasonally frozen ground (SFG), unfrozen ground (UFG), glaciers and lakes, respectively.

Figure 1.

Simulated spatial distribution of frozen ground types in (a) 1970s (b) 1980s (c) 1990s (d) 2000s (e) 2010s, against the (f) new map of permafrost distribution on the QTP (QTP-2016). The yellow, navy blue, purple, and white colors represent the areas of permafrost, seasonally frozen ground (SFG), unfrozen ground (UFG), glaciers and lakes, respectively.

Figure 2.

Spatial patterns of climatology of freezing/thawing indices (a) GTI, (b) GFI, (c) surface ground temperature, (d) ATI, (e) AFI and (f) air temperature from 1961-2010 across the QTP.

Figure 2.

Spatial patterns of climatology of freezing/thawing indices (a) GTI, (b) GFI, (c) surface ground temperature, (d) ATI, (e) AFI and (f) air temperature from 1961-2010 across the QTP.

Figure 3.

Spatial changes of freezing and thawing indices in permafrost regions between 1961-1990 and 1991-2010. (a) and (e) AFI, (b) and (f) GFI, (c) and (g) ATI, (d) and (h) GTI on the QTP.

Figure 3.

Spatial changes of freezing and thawing indices in permafrost regions between 1961-1990 and 1991-2010. (a) and (e) AFI, (b) and (f) GFI, (c) and (g) ATI, (d) and (h) GTI on the QTP.

Figure 4.

The same as the

Figure 3, but for seasonally frozen ground on the QTP.

Figure 4.

The same as the

Figure 3, but for seasonally frozen ground on the QTP.

Figure 5.

The time series of anomaly comparisons between precipitation (left panels), NDVI (right panels) and freezing/thawing indices during 1961-2010, respectively. (a, e) AFI; (b, f) GFI; (c, g) ATI; and (d, h) GTI. Two colors of green (red) bars represent indices anomalies in permafrost and SFG, and the black lines with circles indicate those across the whole QTP. The blue lines with triangles represent the anomalies in the precipitation and the NDVI. Figures in the same colors as permafrost, SFG, and the entire QTP indices shown in the plots represent their correlation coefficients with precipitation and NDVI anomalies. Two asterisks (**) denote p<0.05.

Figure 5.

The time series of anomaly comparisons between precipitation (left panels), NDVI (right panels) and freezing/thawing indices during 1961-2010, respectively. (a, e) AFI; (b, f) GFI; (c, g) ATI; and (d, h) GTI. Two colors of green (red) bars represent indices anomalies in permafrost and SFG, and the black lines with circles indicate those across the whole QTP. The blue lines with triangles represent the anomalies in the precipitation and the NDVI. Figures in the same colors as permafrost, SFG, and the entire QTP indices shown in the plots represent their correlation coefficients with precipitation and NDVI anomalies. Two asterisks (**) denote p<0.05.

Table 1.

Decadal permafrost areas (km2) and trends of AFI, GFI, and ATI, GTI (℃·d/decade) in permafrost, SFG, and the entire QTP from 1961 to 2010.

Table 1.

Decadal permafrost areas (km2) and trends of AFI, GFI, and ATI, GTI (℃·d/decade) in permafrost, SFG, and the entire QTP from 1961 to 2010.

| Periods |

Permafrost area (×106 km2) |

Region |

AFI

(℃·d/decade) |

GFI

(℃·d/decade) |

ATI

(℃·d/decade) |

GTI

(℃·d/decade) |

| 1960s |

1.62 |

permafrost |

-20.75 |

14.99 |

2.07 |

2.25 |

| SFG |

-20.87 |

8.13 |

-4.79 |

-9.10* |

| QTP |

-10.59 |

16.57 |

-8.31 |

-11.09 |

| 1970s |

1.50

(7.41 % ↓) |

permafrost |

0.40 |

1.72 |

-0.53 |

0.25 |

| SFG |

2.14 |

1.16 |

0.05 |

2.40 |

| QTP |

1.32 |

0.73 |

0.45 |

2.67 |

| 1980s |

1.40

(6.67 % ↓) |

permafrost |

-23.28* |

-13.68* |

0.65 |

-1.95 |

| SFG |

-14.87* |

-11.73* |

-3.79 |

-5.19 |

| QTP |

-22.64* |

-17.13* |

0.81 |

-0.13 |

| 1990s |

1.53

(9.29 % ↑) |

permafrost |

-6.93 |

-5.55 |

1.17 |

-4.09 |

| SFG |

-13.03* |

-14.75* |

16.39 |

24.33* |

| QTP |

-19.23 |

-18.60 |

20.96 |

27.21 |

| 2000s |

1.02

(33.33 % ↓) |

permafrost |

13.37 |

14.73 |

-6.41 |

10.98 |

| SFG |

25.68 |

32.66* |

-12.91 |

-9.57 |

| QTP |

38.07 |

52.42* |

-20.07 |

-38.16 |

Table 2.

Comparison of the annual mean (℃·d) and trends (℃·d/decade) of the AFI, GFI, ATI and GTI over the QTP in permafrost and SFG regions from 1961-1990 and 1991-2010.

Table 2.

Comparison of the annual mean (℃·d) and trends (℃·d/decade) of the AFI, GFI, ATI and GTI over the QTP in permafrost and SFG regions from 1961-1990 and 1991-2010.

| Periods |

Frozen type |

AFI |

GFI |

ATI |

GTI |

| |

|

Mean |

Trend |

Mean |

Trend |

Mean |

Trend |

Mean |

Trend |

| 1961-1990 |

permafrost |

3357.15 |

-13.59 |

2427.27 |

67.59 |

187.27 |

39.86* |

940.77 |

29.26 |

| SFG |

1806.63 |

-44.27* |

1258.67 |

1.48 |

1165.43 |

19.61 |

2120.32 |

-10.70 |

| QTP |

1991.66 |

-41.85 |

1397.33 |

8.58 |

1063.34 |

27.71 |

2009.92 |

-0.11 |

| 1991-2010 |

permafrost |

3168.49 |

-202.57* |

2393.41 |

-85.22* |

263.83 |

16.94 |

918.51 |

-83.58 |

| SFG |

1640.24 |

-148.97* |

1184.92 |

-42.39 |

1297.28 |

68.33 |

2162.22 |

-15.20 |

| QTP |

1796.94 |

-57.24 |

1275.56 |

3.21 |

1203.37 |

2.35 |

2154.49 |

-45.90 |

| 1961-2010 |

permafrost |

3286.73 |

-72.74 |

2413.87 |

-0.50 |

217.57 |

32.73* |

931.96 |

-5.38 |

| SFG |

1740.77 |

-68.74 |

1229.48 |

-24.35 |

1217.62 |

47.98 |

2136.69 |

6.13 |

| QTP |

1914.58 |

-71.00* |

1349.13 |

-34.33* |

1118.77 |

48.13* |

2067.14 |

40.37* |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).