Submitted:

31 May 2023

Posted:

01 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Antifungal agents based on metal-nanoparticles, metal-organic frameworks and their derivatives

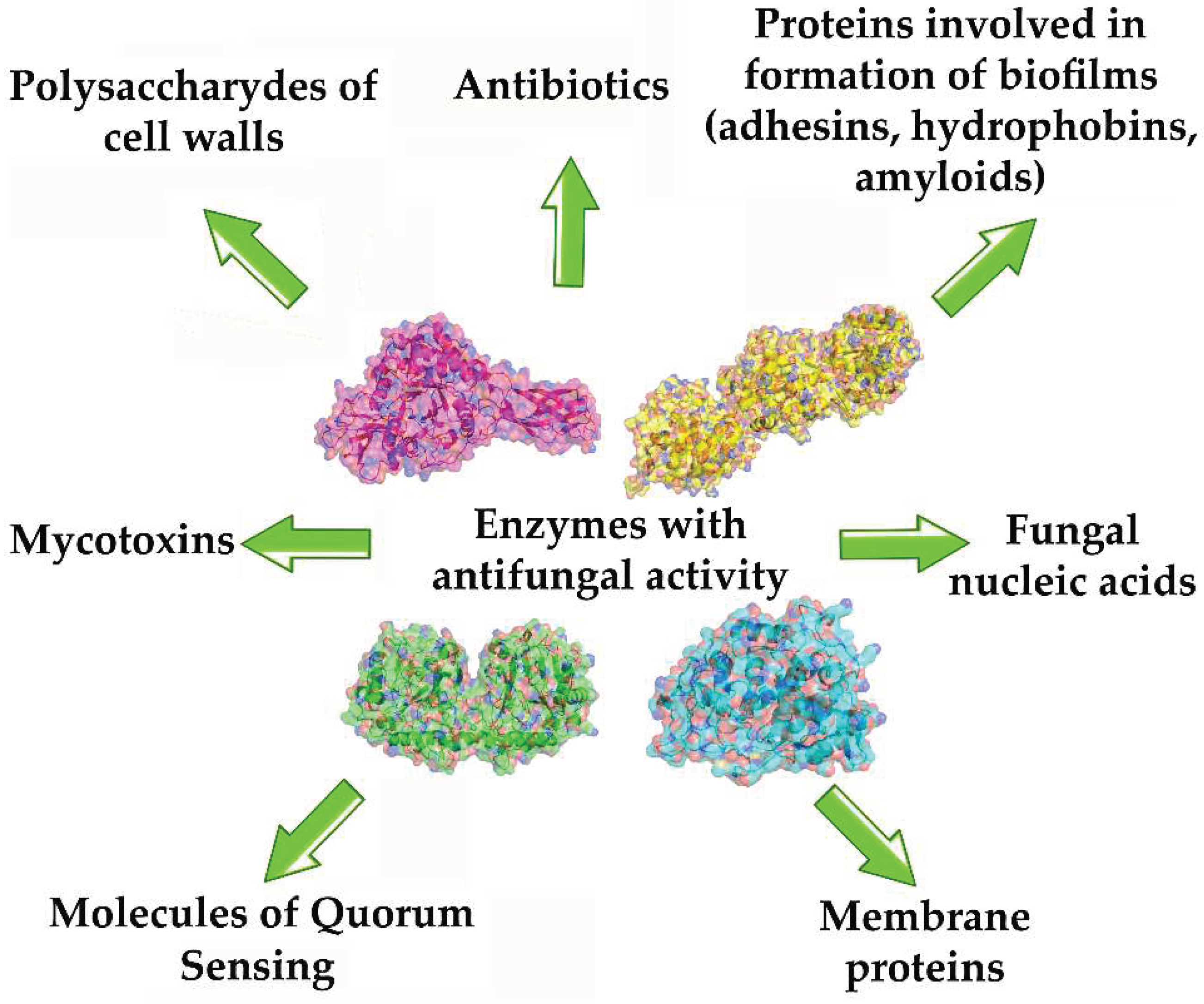

3. Enzymes as antifungal agents

3.1. Antifungal enzymes using cell structural components of fungi as substrates

3.2. Enzymes hydrolyzing fungal proteins with amyloid characteristics

3.3. Enzymes hydrolyzing mycotoxins, antibiotics and QS molecules (QSMs) of fungi

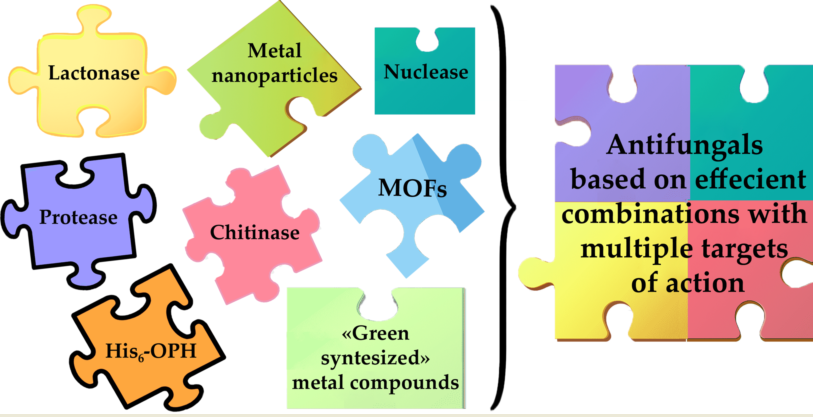

4. Combination of antifungal activity of enzymes with metal-containing compounds

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fisher, M.C.; Gurr, S.J.; Cuomo, C.A.; Blehert, D.S.; Jin, H.; Stukenbrock, E.H.; Stajich, J.E.; Regine Kahmann, R.; Boone, C.; Denning, D.W.; Gow, N.A.R.; Klein, B.S.; Kronstad, J.W.; Sheppard, D.C.; Taylor, J.W.; Wright, C.D.; Heitman, J.; Casadevall, A.; Cowen L.E. Threats posed by the fungal kingdom to humans, wildlife, and agriculture. MBio 2020. 11(3), e00449-20. [CrossRef]

- Garg, D.; Muthu, V.; Sehgal, I.S.; Ramachandran, R.; Kaur, H.; Bhalla, A.; Puri, G.D.; Chakrabarti, A.; Agarwal, R. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) associated mucormycosis (CAM): Case report and systematic review of literature. Mycopathologia 2021, 186, 289–298. [CrossRef]

- Raut, A.; Huy, N.T. Rising incidence of mucormycosis in patients with COVID-19: Another challenge for India amidst the second wave? Lancet Respir Med. 2021, 9(8), e77. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO fungal priority pathogens list to guide research, development and public health action. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2022, pp 48. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240060241 (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- WHO. WHO releases first-ever list of health-threatening fungi, 2022. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/25-10-2022-who-releases-first-ever-list-of-health-threatening-fungi (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Robbins, N.; Caplan, T.; Cowen, L.E. Molecular evolution of antifungal drug resistance. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 71, 753–775. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.C.; Hawkins, N.J.; Sanglard, D.; Gurr, S.J. Worldwide emergence of resistance to antifungal drugs challenges human health and food security. Science 2018, 360, 739–742. [CrossRef]

- Rabaan, A.A.; Sulaiman, T.; Al-Ahmed, S.H.; Buhaliqah, Z.A.; Buhaliqah, A.A.; AlYuosof, B.; Alfaresi, M.; Al Fares, M.A.; Alwarthan, S.; Alkathlan, M.S.; Almaghrabi, R.S.; Abuzaid, A.A.; Altowaileb, J.A.; Al Ibrahim, M.; AlSalman, E.M.; Alsalman, F.; Alghounaim, M.; Bueid, A.S.; Al-Omari, A.; Mohapatra, R.K. Potential strategies to control the risk of antifungal resistance in humans: A comprehensive review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 608. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Luna, A.R.; Cruz-Martínez, H.; Vásquez-López, A.; Medina, D.I. Metal nanoparticles as novel antifungal agents for sustainable agriculture: Current advances and future directions. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 1033. [CrossRef]

- Dananjaya, S.H.S.; Thao, N.T.; Wijerathna, H.M.S.M.; Lee, J.; Edussuriya, M.; Choi, D. Kumar, R.S. In vitro and in vivo anticandidal efficacy of green synthesized gold nanoparticles using Spirulina maxima polysaccharide. Process Biochem. 2020, 92, 138-148. [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, H.N.; Mahmoud, G.A.E.; Sharmouk, W. A cerium-based MOFzyme with multi-enzyme-like activity for the disruption and inhibition of fungal recolonization. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8(33), 7548-7556. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, K.; Acharya, K.; Biswas, A.; Jana, N.R. TiO2 nanoparticles co-doped with nitrogen and fluorine as visible-light-activated antifungal agents. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 2016-2025. [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Shi, H.; Jiang, N.; Qiu, J.; Lin, F.; Kou, Y. Antifungal mechanisms of silver nanoparticles on mycotoxin producing rice false smut fungus. Iscience 2023, 26(1), 105763. [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.A.; Batterjee, M.G.; Kamli, M.R.; Alzahrani, K.A.; Danish, E.Y.; Nabi, A. Polyphenol-capped biogenic synthesis of noble metallic silver nanoparticles for antifungal activity against Candida auris. J. Fungi 2022, 8(6), 639. [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, P.; Mehrvar, A.; Michaud, J.P.; Vaez, N. Optimization of silver nanoparticle biosynthesis by entomopathogenic fungi and assays of their antimicrobial and antifungal properties. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2022, 190, 107749. [CrossRef]

- Jamdagni, P.; Khatri, P.; Rana, J.S. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using flower extract of Nyctanthes arbor-tristis and their antifungal activity. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2018, 30(2), 168-175. [CrossRef]

- Jamdagni, P.; Rana, J.S.; Khatri, P.; Nehra, K. Comparative account of antifungal activity of green and chemically synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles in combination with agricultural fungicides. Int. J. Nano Dimens. 2018, 9(2), 198-208.

- Zhou, L.; Zhao, X.; Li, M.; Lu, Y.; Ai, C.; Jiang, C.; Liu, Y.; Pan, Z.; Shi, J. Antifungal activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized by iturin against Candida albicans in vitro and in vivo. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105(9), 3759-3770. [CrossRef]

- Shamraychuk, I.L.; Belyakova, G.A.; Eremina, I.M.; Kurakov, A.V.; Belozersky, M.A.; Dunaevsky, Y.E. Fungal proteolytic enzymes and their inhibitors as perspective biocides with antifungal action. Moscow Univ. Biol. Sci. Bull. 2020, 75, 97–103. [CrossRef]

- Padder, S.A.; Prasad, R.; Shah, A.H. Quorum sensing: A less known mode of communication among fungi. Microbiol. Res. 2018, 210, 51-58. [CrossRef]

- Baier, F.; Tokuriki, N. Connectivity between catalytic landscapes of the metallo-β-lactamase superfamily. J. Molec. Biol. 2014, 426 (13), 2442-2456. [CrossRef]

- Lyagin, I.; Efremenko, E. Enzymes for detoxification of various mycotoxins: Origins and mechanisms of catalytic action. Molecules 2019, 24, 2362. [CrossRef]

- Ayanwale, A.P.; Estrada-Capetillo, B.L.; Reyes-López, S.Y. Evaluation of antifungal activity by mixed oxide metallic nanocomposite against Candida spp. Processes 2021, 9, 773. [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, V.K.; Patel, M.; Pataniya, P.M.; Iyer, B.D.; Sumesh, C.K.; Late, D.J. Enhanced antifungal activity of WS2/ZnO nanohybrid against Candida albicans. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6(11), 6069-6075. [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, H.N.; Mahmoud, G.A.E. Antifungal and nanozyme activities of metal–organic framework-derived CuO@C. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2023, 37(3), e7011. [CrossRef]

- Pillai, A.M.; Sivasankarapillai, V.S.; Rahdar, A.; Joseph, J.; Sadeghfar, F.; Rajesh, K.; Kyzas, G.Z. Green synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles with antibacterial and antifungal activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1211, 128107. [CrossRef]

- Arciniegas-Grijalba, P.A.; Patiño-Portela, M.C.; Mosquera-Sánchez, L.P.; Guerrero-Vargas, J.A.; Rodríguez-Páez, J.E. ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) and their antifungal activity against coffee fungus Erythricium salmonicolor. Appl. Nanosci. 2017, 7, 225-241. [CrossRef]

- Ilkhechi, N.N.; Mozammel, M.; Khosroushahi, A.Y. Antifungal effects of ZnO, TiO2 and ZnO-TiO2 nanostructures on Aspergillus flavus. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 2021, 176, 104869. [CrossRef]

- Miri, A.; Khatami, M.; Ebrahimy, O.; Sarani, M. Cytotoxic and antifungal studies of biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles using extract of Prosopis farcta fruit. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2020, 13(1), 27-33. [CrossRef]

- Parveen, S.; Wani, A.H.; Shah, M.A.; Devi, H.S.; Bhat, M.Y.; Koka, J.A. Preparation, characterization and antifungal activity of iron oxide nanoparticles. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 115, 287-292. [CrossRef]

- Golipour, F.; Habibipour, R.; Moradihaghgou, L. Investigating effects of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles on Candida albicans biofilm formation. Med. Lab. J. 2019, 13(6), 44-50. [CrossRef]

- Bouson, S.; Krittayavathananon, A.; Phattharasupakun, N.; Siwayaprahm, P.; Sawangphruk, M. Antifungal activity of water-stable copper-containing metal-organic frameworks. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4(10), 170654. [CrossRef]

- Celis-Arias, V.; Loera-Serna, S.; Beltrán, H.I.; Álvarez-Zeferino, J.C.; Garrido, E.; Ruiz-Ramos, R. The fungicide effect of HKUST-1 on Aspergillus niger, Fusarium solani and Penicillium chrysogenum. New J. Chem. 2018, 42(7), 5570-5579. [CrossRef]

- Veerana, M.; Kim, H.C.; Mitra, S.; Adhikari, B.C.; Park, G.; Huh, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y. Analysis of the effects of Cu-MOFs on fungal cell inactivation. RSC Adv. 2021, 11(2), 1057-1065. [CrossRef]

- Tella, A.C.; Okoro, H.K.; Sokoya, S.O.; Adimula, V.O.; Olatunji, S.O.; Zvinowanda, C.; Ngila, J. C.; Shaibu, R.O.; Adeyemi, O.G. Synthesis, characterization and antifungal activity of Fe(III)metal–organic framework and its nano-composite. Chemistry Africa 2020, 3, 119-126. [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Cui, X.; Wang, Z.; Dong, C.; Li, J.; Han, X. Recoverable peroxidase-like Fe3O4@MoS2-Ag nanozyme with enhanced antibacterial ability. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 408, 127240. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cheng, W.; Wang, Y.; Fan, X.; Shen, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, A.; Hui, A.; Nichols, F.; Chen, S. Cobalt-doped zinc oxide nanoparticle–MoS2 nanosheet composites as broad-spectrum bactericidal agents. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 4361-4370. [CrossRef]

- Chiericatti, C.; Basilico, J.C.; Basilico, M.L.Z.; Zamaro, J.M. Novel application of HKUST-1 metal–organic framework as antifungal: Biological tests and physicochemical characterizations. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 162, 60-63. [CrossRef]

- Livesey, T.C.; Mahmoud, L.A.M.; Katsikogianni, M.G.; Nayak, S. Metal–organic frameworks and their biodegradable composites for controlled delivery of antimicrobial drugs. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 274. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Han, Z.; Ding, H.; Xu, X.; Wang, D.; Zhu, Y.; An, F.; Tang, S.; Zhang, H.; Deng, J.; Zhou, Q. Enhanced eradication of bacterial/fungi biofilms by glucose oxidase-modified magnetic nanoparticles as a potential treatment for persistent endodontic infections. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 17289-17299. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jiang, J.; Gao, L. Catalytic antimicrobial therapy using nanozymes. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 14(2), e1769. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, X.M.; Yuan, T.; Zhu, J.R.; Yang, Y.L. Influence of the iodine content of nitrogen- and iodine-doped carbon dots as a peroxidase mimetic nanozyme exhibiting antifungal activity against C. albicans. Biochem. Eng. J. 2021, 175, 108139. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.bej.2021.108139.

- Qingzhi, W.; Zou, S.; Wang, Q.; Chen, L.; Yan, X.; Gao, L. Catalytic defense against fungal pathogens using nanozymes. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2021, 10(1), 1277-1292. [CrossRef]

- Efremenko, E.N.; Lyagin, I.V.; Maslova, O.V.; Senko, O.V.; Stepanov, N.A.; Aslanli, A.G. Catalytic degradation of microplastics. Rus. Chem. Reviews 2023, 92(2), RCR5069. [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Yan, X. Nanozymes: From new concepts, mechanisms, and standards to applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52(8), 2190-2200. [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, E.; Priyadarshini, S.S.; Cousins, B.G.; Pradhan, N. Metal-fungus interaction: Review on cellular processes underlying heavy metal detoxification and synthesis of metal nanoparticles. Chemosphere 2021, 274, 129976. [CrossRef]

- Jian, Y.; Chen, X.; Ahmed, T.; Shang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Ma, Z.; Yin, Y. Toxicity and action mechanisms of silver nanoparticles against the mycotoxin-producing fungus Fusarium graminearum. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 38, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Khina, A.G.; Krutyakov, Y.A. Similarities and differences in the mechanism of antibacterial action of silver ions and nanoparticles. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2021, 57, 683-693. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Li, J.; Pan, L.; Li, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Wu, X.; Luo, J.;Yang, S.T. Particulate toxicity of metal-organic framework UiO-66 to white rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 247, 114275. [CrossRef]

- Sholkamy, E.N.; Ahamd, M.S.; Yasser, M.M.; Eslam, N. Anti-microbiological activities of bio-synthesized silver Nano-stars by Saccharopolyspora hirsute. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 195–200. [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Ghany, M.N.; Hamdi, S.A.; Korany, S.M.; Elbaz, R.M.; Farahat, M.G. Biosynthesis of novel tellurium nanorods by Gayadomonas sp. TNPM15 isolated from mangrove sediments and assessment of their impact on spore germination and ultrastructure of phytopathogenic fungi. Microorganisms 2023, 11, e558. [CrossRef]

- Różalska, B.; Sadowska, B.; Budzyńska, A.; Bernat, P.; Różalska, S. Biogenic nanosilver synthesized in Metarhizium robertsii waste mycelium extract - As a modulator of Candida albicans morphogenesis, membrane lipidome and biofilm. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194254. [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.A.; AlHarbi, L.; Nabi, A.; Alzahrani, K.A.; Narasimharao, K.; Kamli, M.R. Facile synthesis of magnetic nigella sativa seeds: Advances on nano-formulation approaches for delivering antioxidants and their antifungal activity against Candida albicans. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, e642. [CrossRef]

- Akinola, P.O.; Lateef, A.; Asafa, T.B.; Beukes, L.S.; Abbas, S.H.; Irshad, H.M. Phytofabrication of titanium-silver alloy nanoparticles (Ti-AgNPs) by Cola nitida for biomedical and catalytic applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 139, e109357. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, Q.; Sun, Y.; Chen, B.; Wu, X.; Le, T. Improvement of banana postharvest quality using a novel soybean protein isolate/cinnamaldehyde/zinc oxide bionanocomposite coating strategy. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 258, e108786. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Tian, H.; Huang, R.; Liu, H.; Wu, H.; Guo, G.; Xiao, J. Fabrication and characterization of natural polyphenol and ZnO nanoparticles loaded protein-based biopolymer multifunction electrospun nanofiber films, and application in fruit preservation. Food Chem. 2023, 418, e135851. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Ma, X.; Gao, C.; Mu, Y.; Pei, Y.; Liu, C.; Zou, A.; Sun, X. Fabrication of CuO nanoparticles composite ε-polylysine-alginate nanogel for high-efficiency management of Alternaria alternate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 223(Pt A), 1208–1222. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.; Ribeiro, R.; Henriques, M.; Rodrigues, M.E. Candida auris, a singular emergent pathogenic yeast: Its resistance and new therapeutic alternatives. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2022, 41, 1371–1385. [CrossRef]

- Mourer, T.; El Ghalid, M.; d'Enfert, C.; Bachellier-Bassi, S. Involvement of amyloid proteins in the formation of biofilms in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. Res. Microbiol. 2021, 172, e103813. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Filler, S.G. Candida albicans Als3, a multifunctional adhesin and invasion. Eukaryot. Cell 2011, 10, 168–173. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Chang, W.; Li, C.; Lou, H. Als1 and Als3 regulate the intracellular uptake of copper ions when Candida albicans biofilms are exposed to metallic copper surfaces. FEMS Yeast Res. 2016, 16, fow029. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Kim, Y.-G.; Khadke, S.K.; Lee, J. Antibiofilm and antifungal activities of medium-chain fatty acids against Candida albicans via mimicking of the quorum-sensing molecule farnesol. Microb. Biotechnol. 2021, 14, 1353–1366. [CrossRef]

- Sephton-Clark, P.C.S.; Voelz, K. Spore germination of pathogenic filamentous fungi. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 102, 117–157. [CrossRef]

- Slavin, Y.N.; Bach, H. Mechanisms of antifungal properties of metal nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4470. [CrossRef]

- Efremenko, E.; Senko, O.; Stepanov, N.; Maslova, O.; Lomakina, G.Y.; Ugarova, N. Luminescent analysis of ATP: Modern objects and processes for sensing. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 493. [CrossRef]

- Ambati, S.; Ferarro, A.R.; Kang, S.E.; Lin, J.; Lin, X.; Momany, M.; Lewis, Z.A.; Meagher, R.B. Dectin-1-targeted antifungal liposomes exhibit enhanced efficacy. mSphere 2019, 4, e00025-19. [CrossRef]

- Gow, N.A.R.; Latge, J.P.; Munro, C.A. The fungal cell wall: Structure, biosynthesis, and function. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5, FUNK-0035-2016. [CrossRef]

- Kühbacher, A.; Burger-Kentischer, A.; Rupp, S. Interaction of Candida species with the skin. Microorganisms 2017, 5, 32. [CrossRef]

- Lyagin, I.; Stepanov, N.; Maslova, O.; Senko, O.; Aslanli, A.; Efremenko E. Not a mistake but a feature: Promiscuous activity of enzymes meeting mycotoxins. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1095. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, X.; Bai, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. A chitinase with antifungal activity from naked oat (Avena chinensis) seeds. J. Food Biochem. 2019; 43, e12713. [CrossRef]

- Dikbaş, N.; Uçar, S.; Tozlu, E.; Kotan, M.S.; ·Kotan, R. Antifungal activity of partially purified bacterial chitinase against Alternaria alternata. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ma, J.; Yan, Q.; Jiang,Z.; Yang, S. Biochemical characterization of a novel acidic chitinase with antifungal activity from Paenibacillus xylanexedens Z2–4. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 182, 1528-1536. [CrossRef]

- Rajninec, M.; Jopcik, M.; Danchenko, M.; Libantova, J. Biochemical and antifungal characteristics of recombinant class I chitinase from Drosera rotundifolia. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 854–863. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N-N.; Gao, K-Y.; Han, N.; Tian, R-Z.; Zhang, J-L.; Yan, X.; Huang, L-L. ChbB increases antifungal activity of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens against Valsa mali and shows synergistic action with bacterial chitinases. Biol. Control. 2020, 142, 104150. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Hou, Z.; Zhou, D.; Jia, M.; Lu, S.; Yu, J. Antifungal activity and possible mechanism of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FX2 against the postharvest apple ring rot pathogen. Phytopathology 2022, 112, 2486-2494. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, N.; He, J.; Li, Y.; Gao, X.; Huang, L.; Yan, X. Expression and characterization of a novel chitinase with antifungal activity from a rare actinomycete Saccharothrix yanglingensis Hhs.015. Protein Expr. Purif. 2018, 143, 45–51. [CrossRef]

- Brzezinska, M.S.; Jankiewicz, U.; Kalwasinska, A.; Swiatczak, J.; Zero, K. Characterization of chitinase from Streptomyces luridiscabiei U05 and its antagonist potential against fungal plant pathogens. J. Phytopathol. 2019, 167, 404–412. [CrossRef]

- Le, B.; Yang, S.H. Characterization of a chitinase from Salinivibrio sp. BAO-1801 as an antifungal activity and a biocatalyst for producing chitobiose. J. Basic Microbiol. 2018, 58, 848–856. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xia, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Qiao, Y.; Li, C.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, L.; Ye, X.; Huang, Y.; Cui, Z. Identification of an endo-chitinase from Corallococcus sp. EGB and evaluation of its antifungal properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 132, 1235–1243. [CrossRef]

- Moon, C.; Seo, D.J.; Song, Y.S.; Hong, S.H.; Choi, S.H.; Jung, W.J. Antifungal activity and patterns of N-acetyl-chitooligosaccharide degradation via chitinase produced from Serratia marcescens PRNK-1. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 113, 218–224. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.-J.; Shi, D.; Mao, H.-H.; Li, Z.-W.; Liang, S.; Ke, Y.; Luo, X.-C. Heterologous expression and characterization of an antifungal chitinase (Chit46) from Trichoderma harzianum GIM 3.442 and its application in colloidal chitin conversion. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 134, 113-121. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, G.; Cadirci, B. Comparison of in vitro antifungal activity methods using Aeromonas sp. BHC02 chitinase, whose physicochemical properties were determined as antifungal agent candidate. Res. Sq. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Xia, C.; Fan, Q.; Li, X.; Lan, Z.; Shi, G.; Dong, W.; Li, Z.; Cui, Z. Preparation of the active chitooligosaccharides with a novel chitosanase AqCoA and their application in fungal disease protection. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 3351−3361. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Ma, J.; Yan, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, S. Biochemical characterization of a bifunctional chitinase/lysozyme from Streptomyces sampsonii suitable for N-acetyl chitobiose production. Biotechnol. Lett. 2020, 42, 1489–1499. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, T. Cloning and expression of the chitinase encoded by ChiKJ406136 from Streptomyces sampsonii (Millard & Burr) Waksman KJ40 and its antifungal effect. Forests 2018, 9, 699. [CrossRef]

- Bamford, N.C.; Le Mauff, F.; Subramanian, A.S.; Yip, P.; Millán, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zacharias, C.; Forman, A.; Nitz, M.; Codée, J.D.C.; Usón, I.; Sheppard, D.C.; Howell, P.L. Ega3 from the fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus is an endo-α-1,4-galactosaminidase that disrupts microbial biofilms. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294(37), 3833-13849. [CrossRef]

- Ostapska, H.; Raju, D.; Lehoux, M.; Lacdao, I.; Gilbert, S.; Sivarajah, P.; Bamford, N.C.; Baker, P.; Nguyen, T.T.M.; Zacharias, C.A.; Gravelat, F.N.; Howell, P.L.; Sheppard, D.C. Preclinical evaluation of recombinant microbial glycoside hydrolases in the prevention of experimental invasive aspergillosis. mBio 2021, 12, e02446-21. [CrossRef]

- Vidhate, R.P.; Bhide, A.J.; Gaikwad, S.M.; Giri, A.P. A potent chitin-hydrolyzing enzyme from Myrothecium verrucaria affects growth and development of Helicoverpa armigera and plant fungal pathogens. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 141, 517-528. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, W.; Tao, Y.; Zhao, S.; Yao, L.; Cai, Y.; Niu, Q. Overexpression of the key virulencef 1,3-1,4-β-d-glucanase in the endophytic bacterium Bacillus halotolerans Y6 to improve Verticillium resistance in cotton. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67(24), 6828-6836. https:// doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.9b00728.

- Ling, L.; Cheng, W.; Jiang, K.; Jiao, Z.; Luo, H.; Yang, C.; Pang, M.; Lu. L. The antifungal activity of a serine protease and the enzyme production of characteristics of Bacillus licheniformis TG116. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 601. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.-J.; Huang, W.Q.; Li, Z.-W.; Lu, D.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, X.-C. Biocontrol activity of recombinant aspartic protease from Trichoderma harzianum against pathogenic fungi. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2018, 112, 35-42. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Paul, J.; Weldrick, P.J.; Madden, L.A.; Paunov, V.N. Enhanced clearing of Candida biofilms on a 3D urothelial cell in vitro model using lysozyme-functionalized fluconazole-loaded shellac nanoparticles. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 6927–6939. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Téllez, C.N.; Rodríguez-Córdova, F.J.; Rosas-Burgos, E.C.; Cortez-Rocha, M.O.; Burgos-Hernández, A.; Lizardi-Mendoza, J.; Torres-Arreola, W.; Martínez-Higuera, A.; Plascencia-Jatomea, M. Activity of chitosan-lysozyme nanoparticles on the growth, membrane integrity, and β-1,3-glucanase production by Aspergillus parasiticus. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, e279. [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.A.; Albuquerque, L.M.; Martins, T.F.; de Freitas, J.A.; Vasconcelos I.M.; de Freitas,D. Q.; Moreno, F.B.M.B.; Monteiro-Moreira, A.C.O.; Oliveira, J. T.A. A peroxidase purified from cowpea roots possesses high thermal stability and displays antifungal activity against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and Fusarium oxysporum. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2022, 42, 102322. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tao, Y.; Zhao, S. A novel peroxiredoxin from the antagonistic endophytic bacterium Enterobacter sp. V1 contributes to cotton resistance against Verticillium dahliae. Plant Soil 2020, 454, 395–409. [CrossRef]

- Salazar, V.A.; Arranz-Trullén, J.; Navarro, S.; Blanco, J.A.; Sánchez, D.; Moussaoui, M.; Boix, E. Exploring the mechanisms of action of human secretory RNase 3 and RNase 7 against Candida albicans. MicrobiologyOpen 2016, 5(5), 830-845. [CrossRef]

- Salazar, V.A.; Arranz-Trullén, J.; Prats-Ejarque, G.; Torrent, M.; Andreu, D.; Pulido, D.; Boix, E. Insight into the antifungal mechanism of action of human RNase N-terminus derived peptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4558. [CrossRef]

- Kosgey, J.C.; Jia, L.; Nyamao, R.M.; Zhao, Y.; Xue, T.; Yang, J.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, F. RNase 1, 2, 5 & 8 role in innate immunity: Strain specific antimicrobial activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 160, 1042-1049. [CrossRef]

- Philip, N.V.; Koteshwara, A.; Kiran, G.A.; Raja, S.; Subrahmanyam, V.M.; Chandrashekar, H.R. Statistical optimization for coproduction of chitinase and beta 1,4-endoglucanase by chitinolytic Paenibacillus elgii PB1 having antifungal activity. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 191(1), 135-150. [CrossRef]

- Sinitsyna, O.A.; Rubtsova, E.A.; Sinelnikov, I.G.; Osipov, D. O.; Rozhkova, A. M.; Matys, V. Yu.; Bubnova, T.V.; Nemashkalov, V.A.; Sereda, A. S.; Tcsherbakova, L. A.; Sinitsyn, A.P. Creation of chitinase producer and disruption of micromycete cell wall with the obtained enzyme preparation. Biochem. (Mosc.) 2020, 85, 717–724. [CrossRef]

- Sachivkina, N.; Lenchenko, E.; Blumenkrants, D.; Ibragimova, A.; Bazarkina, O. Effects of farnesol and lyticase on the formation of Candida albicans biofilm. Vet. World 2020, 13(6), 1030-1036. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Ma, S.; Leonhard, M.; Moser, D.; Ludwig, R.; Schneider-Stickler, B. Co-immobilization of cellobiose dehydrogenase and deoxyribonuclease I on chitosan nanoparticles against fungal/bacterial polymicrobial biofilms targeting both biofilm matrix and microorganisms. Mater Sci. Eng. C 2020, 108, 110499. [CrossRef]

- Oyeleye, A.; Normi, Y.M. Chitinase: Diversity, limitations, and trends in engineering for suitable applications. Biosci. Rep. 2018, 38, BSR2018032300. [CrossRef]

- Pham, C.L.L.; de Francisco, B.R.; Valsecchi, I.; Dazzoni, R.; Pillé, A.; Lo, V.; Ball, S.R.; Cappai, R.; Wien, F.; Kwan, A.H.; Guijarro, J.I.; Sunde, M. Probing structural changes during self-assembly of surface-active hydrophobin proteins that form functional amyloids in fungi. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 3784–3801. [CrossRef]

- Valsecchi, I.; Dupres, V.; Stephen-Victor, E.; Guijarro, J.I.; Gibbons, J.; Beau, R.; Bayry, J.; Coppee, J.-Y.; Lafont, F.; Latgé, J. P.; Beauvais, A. Role of hydrophobins in Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Fungi 2017, 4, 2. [CrossRef]

- Valsecchi, I.; Lai, J.I.; Stephen-Victor, E.; Pillé, A.; Beaussart, A.; Lo, V.; Pham, C.L.L.; Aimanianda, V.; Kwan, A.H.; Duchateau, M.; Gianetto, Q.G.; Matondo, M.; Lehoux, M.; Sheppard, D.C.; Dufrene, Y.F.; Bayry, J.; Guijarro, J.I.; Sunde, M.; Latgé, J. P. Assembly and disassembly of Aspergillus fumigatus conidial rodlets. Cell Surf. 2019, 5, 100023. [CrossRef]

- Pham, C.L.L.; Rey, A.; Lo, V.; Soulès, M.; Ren, Q.; Meisl, G.; Knowles, T.P.J.; Kwan, A.H.; Sunde, M. Self-assembly of MPG1, a hydrophobin protein from the rice blast fungus that forms functional amyloid coatings, occurs by a surface-driven mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6. [CrossRef]

- Saad, S.; Cereghetti, G.; Feng, Y.; Picotti, P.; Peter, M.; Dechant, R. Reversible protein aggregation is a protective mechanism to ensure cell cycle restart after stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 1202e13. [CrossRef]

- Beaussart, A.; Alsteens, D.; El-Kirat-Chatel, S.; Lipke, P.N.; Kucharíkova, S.; Dijck, P.V.; Dufrene, Y.F. Single-molecule imaging and functional analysis of Als adhesins and mannans during Candida albicans morphogenesis. ACS Nano 2012, 6 (12), 10950–10964. [CrossRef]

- Ho, V.; Herman-Bausier, P.; Shaw, C.; Conrad, K.A.; Garcia-Sherman, M.C.; Draghi, J.; Dufrene, Y.F.; Lipke, P.N.; Rauceo, J.M. An amyloid core sequence in the major Candida albicans adhesin Als1p mediates cell-cell adhesion. mBio 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Breindel, C.; Saraswat, D.; Cullen, P.J.; Edgerton, M. Candida albicans Sap6 amyloid regions function in cellular aggregation and zinc binding, and contribute to zinc acquisition. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2908. [CrossRef]

- Monniot, C.; Boisrame, A.; Costa, G.D.; Chauvel, M.; Sautour, M.; Bougnoux, M-E.; Bellon-Fontaine, M.-N.; Dalle, F.; d’Enfert, C.; Richard, M.L. Rbt1 protein domains analysis in Candida albicans brings insights into hyphal surface modifications and Rbt1 potential role during adhesion and biofilm formation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82395. [CrossRef]

- Cabral, V.; Znaidi, S.; Walker, L.A.; Martin-Yken, H.; Dague, E.; Legrand, M.; Lee, K.; Chauvel, M.; Firon, A.; Rossignol, T.; Munro, A.C.; Bachelier-Bassi, S.; d’Enfert, C. Targeted changes of the cell wall proteome influence Candida albicans ability to form single- and multi-strain biofilms. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004542. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Ruiz, E.; Ortu, G.; de Groot, P.W.J.; Cottier, F.; Loussert, C.; Prevost, M-C.; de Koster, C.; Klis, M.F., Goyard, S.; d’Enfert, C. The GPI-modified proteins Pga59 and Pga62 of Candida albicans are required for cell wall integrity. Microbiology 2009, 155, 2004e20. [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, N.; Baker, M.O.; Ball, S.R.; Steain, M.; Pham, C.L.; Sunde, M. Microbial functional amyloids serve diverse purposes for structure, adhesion and defence. Biophys. Rev. 2019, 11, 287-302. [CrossRef]

- Chernova, T.A.; Chernoff, Y.O.; Wilkinson, K.D. Yeast models for amyloids and prions: Environmental modulation and drug discovery. Molecules 2019, 24, 3388. [CrossRef]

- Hirata, A.; Hori, Y.; Koga, Y.; Okada, J.; Sakudo, A.; Ikuta, K.; Kanaya, S.; Takano, K. Enzymatic activity of a subtilisin homolog, Tk-SP, from Thermococcus kodakarensis in detergents and its ability to degrade the abnormal prion protein. BMC Biotech. 2013, 13, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Dabbagh, F.; Negahdaripour, M.; Berenjian, A.; Behfar, A.; Mohammadi, F.; Zamani, M.; Irajie, C.; Ghasemi, Y. Nattokinase: Production and application. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 9199–9206. [CrossRef]

- Pilon, J.L.; Nash, P.B.; Arver, T.; Hoglund, D.; VerCauteren, K.C. Feasibility of infectious prion digestion using mild conditions and commercial subtilisin. J. Virol. Methods. 2009, 161, 168–172. [CrossRef]

- Saunders, S.E.; Bartz, J.C.; Vercauteren, K.C.; Bartelt-Hunt, S.L. Enzymatic digestion of chronic wasting disease prions bound to soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 4129–4135. [CrossRef]

- McLeod, A.H.; Murdoch, H.; Dickinson, J.; Dennis, M.J.; Hall, G.A.; Buswell, C.M.; Carr, J.; Taylor, D.M.; Sutton, J.M.; Raven, N.D.H. Proteolytic inactivation of the bovine spongiform encephalopathy agent. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 317, 1165e1170. [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J.; Murdoch, H.; Dennis, M.J.; Hall, G.A.; Bott, R.; Crabb, W.D.; Penet, C.; Sutton, J.M.; Raven, N.D.H. Decontamination of prion protein (BSE301V) using a genetically engineered protease. J. Hosp. Infect. 2009, 72, 65e70. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, M.; Miwa, T.; Horii, H.; Takata, M.; Yokoyama, T.; Nishizawa, K.; Watanabe, M.; Shinagawa, M.; Murayama, Y. Characterization of a proteolytic enzyme derived from a Bacillus strain that effectively degrades prion protein. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 102, 509e515. [CrossRef]

- Hui, Z.; Doi, H.; Kanouchi, H.; Matsuura, Y.; Mohri, S.; Nonomura, Y.; Oka, T. Alkaline serine protease produced by Streptomyces sp. degrades PrPSc. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 321, 45e50. [CrossRef]

- Bahun, M.; Šnajder, M.; Turk, D.; Poklar Ulrih, N. Insights into the maturation of pernisine, a subtilisin-like protease from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Aeropyrum pernix. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00971-20. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.J.; Bennett, J.P.; Biro, S.M.; Duque-Velasquez, J.C.; Rodriguez, C.M.; Bessen, R.A.; Rocke, T.E. Degradation of the disease-associated prion protein by a serine protease from lichens. PLoS ONE. 2011, 11, e19836. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Rojanatavorn, K.; Clark, A.C.; Shih, J.C. Characterization and enzymatic degradation of Sup35NM, a yeast prion-like protein. Prot. Sci. 2005, 14, 2228-2235. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Borwornpinyo, R.; Odetallah, N.; Shih, J.C. Enzymatic degradation of a prion-like protein, Sup35NM-His6. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2005, 36, 758-765. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Gupta, R. Coupled action of γ-glutamyl transpeptidase-glutathione and keratinase effectively degrades feather keratin and surrogate prion protein, Sup 35NM. Biores. Tech. 2012, 120, 314-317. [CrossRef]

- Rajput, R.; Gupta, R. Thermostable keratinase from Bacillus pumilus KS12: Production, chitin crosslinking and degradation of Sup35NM aggregates. Biores. Tech. 2013, 133, 118-126. [CrossRef]

- Ningthoujam, D.S.; Mukherjee, S., Devi, L.J.; Singh, E.S.; Tamreihao, K.; Khunjamayum, R.; Banerjee, S.; Mukhopadhyay, D. In vitro degradation of β-amyloid fibrils by microbial keratinase. Alzheimers Dement. 2019, 5, 154-163. [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Lee, H.J. Redox-active metal ions and amyloid-degrading enzymes in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7697. [CrossRef]

- Manikandan, P.; Moopantakath, J.; Imchen, M.; Kumavath, R.; SenthilKumar, P. K. Identification of multi-potent protein subtilisin A from halophilic bacterium Bacillus firmus VE2. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 157, 105007. [CrossRef]

- Kokwe, L.; Nnolim, N. E.; Ezeogu, L.I.; Sithole, B.; Nwodo, U.U. Thermoactive metallo-keratinase from Bacillus sp. NFH5: Characterization, structural elucidation, and potential application as detergent additive. Heliyon. 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Efremenko, E.; Aslanli, A.; Lyagin, I. Advanced situation with recombinant toxins: Diversity, production and application purposes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4630. [CrossRef]

- Efremenko, E.; Senko, O.; Stepanov, N.; Aslanli, A.; Maslova, O.; Lyagin, I. Quorum sensing as a trigger that improves characteristics of microbial biocatalysts. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1395. [CrossRef]

- Willaert, R.G. Adhesins of yeasts: Protein structure and interactions. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 119. [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Ding, H.; Ke,W.; Wang, L. Quorum sensing in fungal species. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 75, 449–469. [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A.; Liu, G.;Wang, X.; Meng, G.;Wang, C.; Liu, Y. Fungal quorum-sensing molecules and inhibitors with potential antifungal activity: A review. Molecules 2019, 24, 1950. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.R.; Oh, H.S.; Park, P.K.; Choo, K.H.; Kim, Y.W.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, C.H. Fungal quorum quenching: A paradigm shift for energy savings in membrane bioreactor (MBR) for wastewater treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50(20), 10914-10922. [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, K.; Nakajima-Kambe, T.; Nakahara, T.; Kokufuta, E. Coimmobilization of gluconolactonase with glucose oxidase for improvement in kinetic property of enzymatically induced volume collapse in ionic gels. Biomacromolecules 2002; 3(3), 625-631. [CrossRef]

- Aslanli, A.; Domnin, M.; Stepanov, N.; Efremenko, E. “Universal” antimicrobial combination of bacitracin and His6-OPH with lactonase activity, acting against various bacterial and yeast cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9400. [CrossRef]

- Aslanli, A.; Domnin, M.; Stepanov, N.; Efremenko, E. Synergistic antimicrobial action of lactoferrin-derived peptides and quorum quenching enzymes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3566. [CrossRef]

- Hogan, D. Talking to themselves: Autoregulation and quorum sensing in fungi. Eukaryoitic Cell 2006, 5(4), 613–619. [CrossRef]

- Bu'LocK, J.D.; Jones, B.E.; Winskill, N. The apocarotenoid system of sex hormones and prohormones in mucorales. Pure AppL. Chem. 1976, 47, 191-202. [CrossRef]

- Alves, D.R.; de Morais, S.M.; Tomiotto-Pellissier, F.; Vasconcelos, F.R.; Francisco das Chagas Oliveira Freire, F.C.O.; da Silva, I.N.G.; Cataneo, A.H.D.; Miranda-Sapla, M.M.; Gustavo Adolfo Saavedra Pinto, G.A.S.; Conchon-Costa, I.; Arlindo de Alencar Araripe Noronha, A.A.A.; Pavanelli, W.R. Leishmanicidal and fungicidal activity of lipases obtained from endophytic fungi extracts. PLoS ONE 2018, 13(6), e0196796. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Poeta, M. Lipid signalling in pathogenic fungi. Cell. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 177–185. [CrossRef]

- Beccaccioli,M.; Reverberi,M.; Scala, V. Fungal lipids: Biosynthesis and signalling during plant-pathogen interaction. Front. Biosci. 2019, 24(1), 168–181. [CrossRef]

- Frolov, G.; Lyagin, I.; Senko, O.; Stepanov, N.; Pogorelsky, I.; Efremenko, E. Metal nanoparticles for improving bactericide functionality of usual fibers. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1724. [CrossRef]

- Lyagin, I.; Stepanov, N.; Frolov, G.; Efremenko, E. Combined modification of fiber materials by enzymes and metal nanoparticles for chemical and biological protection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1359. [CrossRef]

- Lyagin, I.; Maslova, O.; Stepanov, N.; Presnov, D.; Efremenko, E. Assessment of composite with fibers as a support for antibacterial nanomaterials: A case study of bacterial cellulose, polylactide and usual textile. Fibers 2022, 10, 70. [CrossRef]

- Lyagin, I.; Maslova, O.; Stepanov, N.; Efremenko, E. Degradation of mycotoxins in mixtures by combined proteinous nanobiocatalysts: In silico, in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 218, 866–877. [CrossRef]

- Garces, F.; Fernández, F.J.; Montellà, C.; Penya-Soler, Prohens, E.R.; Aguilar, J.; Baldomà, L.; Coll, M.; Badia, J.; Vega, M.C. Molecular architecture of the Mn2+-dependent lactonase UlaG reveals an RNase-like metallo-β-lactamase fold and a novel quaternary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 39(5), 715-729. [CrossRef]

- González, J.M. Visualizing the superfamily of metallo-β-lactamases through sequence similarity network neighborhood connectivity analysis. Heliyon 2021, 7(1), e05867. [CrossRef]

- Jang, E.-Y.; Son, Y.-J.; Park, S.-Y.; Yoo, J.-Y.; Cho, Y.-N.; Jeong, S.-Y.; Liu, S.; Son, H.-J. Improved biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using keratinase from Stenotrophomonas maltophilia R13: Reaction optimization, structural characterization, and biomedical activity. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 41, 381–393. [CrossRef]

- Abo-Zaid, G.; Abdelkhalek, A.; Matar, S.; Darwish, M.; Abdel-Gayed, M. Application of bio-friendly formulations of chitinase-producing Streptomyces cellulosae Actino 48 for controlling peanut soil-borne diseases caused by Sclerotium rolfsii. J. Fungi 2021, 7, e167. [CrossRef]

- Gaonkar, S.K.; Furtado, I.J. Biorefinery-fermentation of agro-wastes by Haloferax lucentensis GUBF-2 MG076878 to haloextremozymes for use as biofertilizer and biosynthesizer of AgNPs. Waste Biomass Valori. 2022, 13, 1117–1133. [CrossRef]

- Guilger-Casagrande, M.; Germano-Costa, T.; Pasquoto-Stigliani, T.; Fraceto, L.F.; de Lima, R. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles employing Trichoderma harzianum with enzymatic stimulation for the control of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, e14351. [CrossRef]

- Guilger-Casagrande, M.; Germano-Costa, T.; Bilesky-José, N.; Pasquoto-Stigliani, T.; Carvalho, L.; Fraceto, L.F.; de Lima, R. Influence of the capping of biogenic silver nanoparticles on their toxicity and mechanism of action towards Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. J. Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, e53. [CrossRef]

- Dror, Y.; Ophir, C.; Freeman, A. Silver-enzyme hybrids as wide-spectrum antimicrobial agents. Innovations and merging technologies in wound care (Amit Gefen, Ed.). Elsevier Inc. 2020, 293–307. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Q.; Liu, S.; Li, M. Synthesis of the ternary nanocomposites composed of zinc 2-methylimidazolate frameworks, lactoferrin and melittin for antifungal therapy. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 16809–16819. [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Xu, Y.; Hoy, R.; Zhang, J.; Qin, L.; Li, X. The notorious soilborne pathogenic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: An update on genes studied with mutant analysis. Pathogens 2020, 9, e27. [CrossRef]

- Chet, I.; Henis, Y. Effect of catechol and disodium EDTA on melanin content of hyphal and sclerotial walls of Sclerotium rolfsii sacc. and the role of melanin in the susceptibility of these walls to β-(1→3) glucanase and chitinase. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1969, 1, 131–138. [CrossRef]

- Melo, B.S.; Voltan, A.R.; Arruda, W.; Lopes, F.A.C.; Georg, R.C.; Ulhoa, C.J. Morphological and molecular aspects of sclerotial development in the phytopathogenic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Microbiol. Res. 2019, 229, e126326. [CrossRef]

- Babina, S.E.; Kanyshkova, T.G.; Buneva, V.N.; Nevinsky, G.A. Lactoferrin is the major deoxyribonuclease of human milk. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 2004, 69, 1006–1015. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, K.E.; Weeks, K.; Carter, D.A. Lactoferrin is broadly active against yeasts and highly synergistic with amphotericin B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e02284-19. [CrossRef]

- Espinel-Ingroff, A. Novel antifungal agents, targets or therapeutic strategies for the treatment of invasive fungal diseases: A review of the literature (2005-2009). Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2009, 26(1), 15-22. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, M.; Ćirić, A.; Stojković, D. Emerging antifungal targets and strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2756. [CrossRef]

| Antifungal agent [Reference] | Target of action | Antifungal activity | Efficiency of antifungal action |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZrO2-Ag2O (14-42 nm)[23] |

Candida albicans, C. dubliniensis, C.glabrata, C.tropicalis |

The growth rate inhibition | 89-97% inhibition |

| WS2/ZnO nano- hybrids [24] | C. albicans | Inhibition of biofilm formation | 91% inhibition |

| CuO@C (36–123 nm) [25] |

Alternaria alternata, Fusarium oxysporum, Penicillium digitatum, Rhizopus oryzae | Inhibition of the hydrolytic activity of fungal enzymes used by them for their own metabolism | Inhibition (100 μg/mL) of cellulases and amylases secreted by fungi: 38% and 42% for A. alternata, 39% and 45% for F. oxysporum, 24% and 67% for P. digitatum, and 20% and 24%for R. oryzae, respectively |

| ZnO-NPs [26] |

C. albicans, Aspergillus niger |

Inhibition of growth | Large enough zone of growth absence (8-9 mm) |

| ZnO-NPs (20-45 nm) [27] |

Erythricium salmonicolor | Notable thinning of the hyphae and cell walls, liquefaction of the cytoplasmic content with decrease in presence of a number of vacuoles | Significant inhibition (9-12 mmol/L) of cell growth |

| ZnO–TiO2 (8-33 nm) [28] |

A. flavus | High level of ROS production and oxidative stress induction. Treated objects have a lower count of spores and damaged tubular filaments and noticeably thinner hyphae compared to the untreated fungi | Fungicidal inhibition (150 μg/mL) zone is 100 % |

| ZnO (40-50 nm) [29] |

C. albicans | High level of ROS production | MIC=32-64 mkg/mL MFC=128-512 mg/mL |

| Fe2O3 (10–30 nm) [30] |

Trichothecium roseum, Cladosporium herbarum, P. chrysogenum, A. alternate, A. niger. |

Inhibition of spore germination | MIC=0.063-0.016 mg/mL |

| Fe3O4 (70 nm) [31] | C. albicans | Inhibition of cell growth and biofilm formation | MIC=100 ppm MFC=200 ppm |

| Cu-BTC (10–20 µm)[32] |

C. albicans, A. niger, Aspergillus oryzae, F. oxysporum |

ROS producing, the damage of the cell membrane | Inhibition of C. albicans colonies is 96% by 300 ppm and up to 100% by 500 ppm. Inhibition growth of F. oxysporum and A. oryzae is is 30% with 500 ppm. No significant effect on the A. niger growth. |

| HKUST-1 or HKUST-1NP (doped with NPs of Cu(I)) (49-51 nm) [33] | A. niger, Fusarium solani, Penicillium chrysogenum | Appearance of Cu+2 inhibiting of cell growth | 100% growth inhibition of F. solani by 750-1000 ppm and P. chrysogenum by 1000 ppm; for A. niger - no inhibition |

| [Cu2(Glu)2(LIGAND)] x(H2O) [34] |

C. albicans , A. niger spores |

The apoptosis-like fungal cell death | 50–80% fungal death at 2 mg/mL of the MOFs |

| MIL-53(Fe) and Ag@MIL-53(Fe) composite [35] | Aspergillus flavus | Inhibition of cell growth | MIC= 40 μg/mL for the MIL-53(Fe); MIC=15 μg/mL for the Ag@MIL-53(Fe) |

| Ce-MOF on the base of 4,4’,4”-nitrilo- tribenzoic acid [11] |

A. flavus, A. niger, Aspergillus terreus, C. albicans, Rhodotorula glutinis |

Enzymatic-like activity: catalase, superoxide dismutase, and peroxidase | Inhibition efficiency of 93.3–99.3% based on the colony-forming unit method |

| NPs of TiO2 co-doped with nitrogen and fluorine (200–300 nm) [12] | F. oxysporum | Peroxidase-like enzymatic activity, production of ROS under light irradiation | 100% inhibition of fungal growth |

| Fe3O4@MoS2-Ag (~428.9 nm) [36] | C. albicans | Peroxidase-like enzymatic activity | 80% damage of cell membranes |

| CoZnO/MoS2 nanocomposite [37] | A. flavus | Peroxidase-like photocatalytic activity | MIC=1.8 mg/mL |

| Antifungal formulation [References] |

Target fungi | *MFC, mg/L | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green synthesized Au NPs in Spirulina maxima [37] |

C. albicans |

0.064 (μDT) |

Damage of cell wall |

| Green synthesized Ag NPs (30 nm) [50] |

C. albicans | n/a (DDT) | Antibacterial agent |

| Bio-synthesized Te nanorods (ca. 50×500 nm) [51] |

F. oxysporum Alternaria alternata |

60 (SGT) 40 (SGT) |

Germination inhibitor |

| Green synthesized Ag NPs (30 nm) [52] |

C. albicans Candida glabrata Candida parapsilosis |

1.6–6.3 (μDT) 3.1 (μDT) 12.5 (μDT) |

Antibiofilm agent, yeast-to-hyphal inhibitor |

| Green synthesized Fe3O4 NPs (0.5–2 μm) [53] |

C. albicans | 6.3 (μDT) | Antibiofilm agent, yeast-to-hyphal inhibitor |

| Green synthesized Ti/Ag NPs (20–120 nm) [54] |

A. niger A. flavus F. solani |

>100 (MGT) | Antibacterial agent |

| ZnO microparticles (2–5 μm) in film of soybean proteins with cinnamaldehyde [55] | Aspergillus niger | n/a (DDT) | Coating for surfaces, field trial |

| ZnO NPs (20–40 nm) in zein/gelatin nanofibers with (poly)phenolic acids [56] | Botrytis cinerea | n/a (MGT) | Coating for surfaces, field trial |

| CuO NPs in Ca-alginate nanogel coated by poly-ε-lysine (60 nm) [57] |

A. alternate, B. cinerea Phytophthora capsica, Thanatephorus cucumeris Fusarium graminearum |

>1000 (MGT) | Germination inhibitor used in field trials |

| Enzyme, its molecular weight and origin [Reference] | Object of action | Conditions of action | Target of action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chitinases | |||

| Chitinase (35 kDa) from seeds of naked oat Avena chinensis [70] | Panus conchatus, Trichoderma reesei | pH 7.0; 30-50 °C | Hydrolysis of β-1, 4-glycosidic linkages in chitin (an insoluble linear homopolymer of β-1,4-linked N-acetyl-glucosamine residues |

| Chitinase (33 kDa) from Lactobacillus coryniformis 3N11[71] | Alternaria alternata | pH 5.0-7.0; 50-80 °C | Inhibition of fungal cell growth detected by the method of disks on agar-containing medium |

| Acidic chitinase (52.8 kDa) from Paenibacillus xylanexedens Z2–4 was produced in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells [72] |

Alternaria alstroemeriae, Botrytis cinerea,Rhizoctonia solani,Sclerotinia sclerotorum, Valsa mali |

pH 4.0-13.0; 50-65 °C; pHoptimum 4.5; Inhibition of the enzyme was detected by the metals: 22-24% by Cu2+and Co2+; 15% by Cr3+ and Mn2+; 17-18% by Sr2+,Ni2+, Fe2+. |

The highest specific activity has towards colloidal chitin, followed by ethylene glycol chitin and ball milled chitin. It inhibits the hyphal extension. |

| Chitinase (30 kDa) from Drosera rotundifolia was produced in Escherichia coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL [73] | Fusarium poae, Trichoderma viride, Alternaria solani | pH 5.0-7.0; 30-45 °C; Inhibition of the enzyme was detected by the metals: 17% by Fe2+, 40% by Pb2+, 48% by Cu2+ and 58% by Cd2+ |

40-52.6% decrease of fungal growth, whereas the stimulation (up to 50%) of growth of R. solani sp. |

| Chitinase (64.1 kDa) from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens [74,75] |

Botryosphaeria dothidea, B. cinerea, F. graminearum, Rhizoctonia cerealis,S. sclerotiorum, Ustilaginoidea virens |

pH 8.0; 37 °C |

60-68% decrease of fungal growth, degeneration of hyphae morphology |

| Chitinase (77.9 kDa) from a rare actinomycete Saccharothrix yanglingensis Hhs.015 (isolated from the roots of cucumber) [76] |

V. mali | pH 6.0; 30-45 °C; Inhibition of the enzyme was detected by the metals: 80% by Zn2+, 65-70% by Ca2+, Mn2+, Fe2+. Ions Cu2+, Cr3+ and Mg2+ significantly promoted chitinase activity (by 187.3%, 167.5% and 111.9%, respectively). |

Multiple deformations of fungal hyphae. |

| Chitinase (45 kDa) from Streptomyces luridiscabiei U05 (isolated from wheat rhizosphere) [77] |

A. alternata, F. oxysporum, F. solani, F. culmorum, B. cinerea, Penicillium verrucosum |

pH 6.0–8.0; 35–40 °C; 98% inhibition of the enzyme was detected in presence of Hg2+and Pb2+. The chitinase activity was stimulated by Ca2+ (120%) and Mg2+ (140%) ions. |

Inhibition of fungal growth due to the demonstration of both endo- and exo-chitinase activity by the enzyme. |

| Chitinase (94.2 kDa) from Salinivibrio sp. BAO-1801 [78] |

A.niger, F. oxysporum, R. solani |

pH 6.0–8.0; 40–55 °C |

100% inhibitory effect on spore germination of fungal cellss |

| Endochitinase (52.9 kDa) from Corallococcus sp. EGB was produced in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) [79] | Magnaporthe oryzae | pH 5.0–8.0; 30–55 °C |

Inhibition of conidia germination and appressorium formation due to the hydrolysis of chitin into N-acetylated chitohexaose |

| Endo- and exochitinases (34, 41 and 48 kDa) from Serratia marcescens PRNK-1 isolated from cockroaches Periplaneta americana [80] | R. solani, F. oxysporum | pH 4.5-7.0; 40-60 °C; pHoptimum 5.5, toptimum 55 °C |

Strong inhibition of fungal hyphae growth |

| Chitinase (46 kDa) from Trichoderma harzianum GIM 3.442 [81] | B. cinerea | pH 5.0-8.0; 40-55 °C; pHoptimum 6.0, toptimum 45 °C 49.4% and 66.6% inhibition of the enzyme was detected in presence of Zn2+and Cu2+ respectively. The chitinase activity was stimulated by Ca2+ (115.2%) and Sr2+ (112.6%) ions. |

Up to 80% inhibition of fungal growth |

| Complex of chitinases (25, 37 and 110 kDa) from Aeromonas sp.[82] |

F. solani, A. alternate, B. cinerea, Penicillium sp. |

pH 5.0-8.0; 30-50 °C |

Inhibition of fungal growth |

| Endochitosanasa (50.7 kDa) from Aquabacterium sp. [83] |

M. oryzae, F. oxysporum |

pH 5.0; 40 °C | The enzyme inhibits appressorium formation of M. oryzae and hydrolyzes 95%-deacetylated chitosan with accumulation of chitooligosaccharides inhibiting the growth of fungal cells of M. oryzae and F. oxysporum. |

| Chitinase (30 kDa or 48 kDa) from Streptomyces sampsonii with bifunctional activity was produced in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) [84,85] |

Cylindrocladium scoparium, Cryphonectria parasitica,, Neofusicoccum parvum, F. oxysporum |

pH 3.0-11.5; 30-60 °C pHoptimum 6.0, toptimum 55 °C Enzymatic activity was stimulated by Ca2+ (132%), Mg2+ and Mn2+ slightly (9%) decrease the activity, whereas Ag+ and Cr3+ notably inhibited enzymatic activity (80% and 42% respectively). |

The enzyme possessed the dual enzymatic activity of chitinase and lysozyme and its action results in complete destruction of the mycelial morphology. |

| Glucanases | |||

| Endo-1,4-galactosaminidase from Aspergillus fumigatus was produced in E. coli BL21 (DE3) [86] | A. fumigatus | pH 6.0-7.0; 28 °C |

Enzyme catalyzes the hydrolysis of exopolysaccharide galactosaminogalactan being integral component of A. fumigatus matrix |

| Endo-a-1,4-N-acetyl-D- galactosaminidase (produced in E.coli) and Endo-a-1,4-D- galactosaminidase (produced in Pichia pastoris) [87] |

A. fumigatus | pH 7.4; 37 °C | The enzymes catalyses destruction of adhesive exopolysaccharides in biofilms formed by fungi. |

| Endo-β-1,3-glucanase (46.6 kDa) from M. oryzae was produced in E. coli BL21 (DE3) [88] | M. oryzae,U. maydis | pH 5.0-8.0; 20-45 °C Relative activity was following in presence of K+ (39%), Ba2+ (46.2%), Ca2+ (47.1%), Co2+ (22.2%), Cr2+ (55.1%), Cu2+ (30%), Mg2+ (31.6%), Mn2+ (23.1%), Ni2+ (20.7%), Zn2+ (1.9%), Fe3+ (60%) and Fe2+ (103.1%) |

The enzyme inhibits formation of germ tubes and appressoria. |

| β-(1-3)-glucanase (32 kDa) from Bacillus halotolerans was produced in E. coli BL21 [89] | V. dahliae | pH 7.0; 28 °C |

Strong inhibition of spore germination and mycelial growth of the fungal cells. |

| Proteases | |||

| Serine protease (87.16 kDa) from B. licheniformis TG116 [90] |

P. capsica, R. solani, F. graminearum, F. oxysporum, Botrytis cinerea, Cescospora capsici |

pH 7.3; 30 °C | The most notable inhibition of fungal growth was revealed in case of C. capsici. |

| Aspartic protease P6281 (38 kDa) from T. harzianum was produced in Pichia pastoris cells [91] |

B. cinerea, Mucor circinelloides, A. fumigatus, A. flavus, R. solani, C. albicans |

pH 2.5-4.0; 30-45 °C; 49.4% and 66.6% inhibition of the enzyme was detected in presence of Zn2+and Cu2+ respectively. The aspartic protease activity was stimulated by Mn2+ (140.1%) and Cu2+ (151.2%) ions. Ca2+, Mg2+ and Ni2+ slightly (7-10%) increase the activity, whereas Fe2+ and Zn2+ ions decrease activity of the enzyme. | Inhibition of spore germination and growth of fungal cells: 57.3% B. cinerea, 30.9% 26.1% M. circinelloides, 27.2% A. fumigatus, 34.8% A. flavus, R. solani, C. albicans |

| Lysozyme | |||

| Lysozyme with fluconazole in shellac NPs [92] | Biofilm of C. albicans | pH 5.5 | Biofilm clearing effect was observed. |

| Lysozyme in NPs of chitosane [93] | Aspergillus parasiticus | 28 °C | The decrease in fungal cell viability, 100%- inhibitory effect on the germination of spores was confirmed. |

| Peroxidases | |||

| Peroxidase (58 kDa) from cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) roots [94] |

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, F. oxysporum |

pH 4-7; 37-75 °C |

Enzyme catalyzes redox reactions and inhibits the conidia germination of fungal cells by altering the permeabilization of membranes. |

| Peroxiredoxin (38 kDa) from Enterobacter sp. was produced in E. coli DH5α [95] |

Verticillium dahlia, F. solani |

pH 4-7; 37-75 °C |

Peroxidase inhibits the growth of fungi. |

| Nucleases | |||

| RNase 3 from eosinophils and the skin-derived RNase 7 were produced in E. coli BL21 (DE3) [96,97] | C. albicans | pH 5.0-7.2; 20-37 °C | RNases demonstrated dual mechanism of action: an overall yeast membrane-destabilization (permeabilization and depolymerization) and degradation of target cellular RNA. |

| Bovine pancreas RNase A1, human recombinant ribonucleases A2, A5 and A8 [98] |

C. albicans, C. glabrata |

pH 5.0-7.2; 30-37 °C | Action of RNase A1 was the most pronounced, it completely killed Candida cells by lowering the mitochondrial membrane potential but did not damage the cell membrane. |

| Enzymatic comlexes | |||

| Chitinase and β-1,4-endoglucanase co-synthesized by Paenibacillus elgii PB1[99] |

A. niger, Trichophyton rubrum, Microsporum gypseum, C. albicans, Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

pH 5.0; 30 °C Urea had significant negative effect on β-1,4-endoglucanase, Zn2+ positively affected both enzymatic activities. |

Inhibition of fungal growth: 88% A. niger, 92% T. rubrum, 52% M. gypseum, 55% C. albicans, 71% S. cerevisiae |

| Enzymatic complex from Penicillilum verruculosum containing chitinase (43 kDa, gene from Myceliophtora thermophyla), cellobiohydrolase (66 kDa), endoglucanase (39 kDa) and xylanase (32 kDa) [100] |

Fusarium culmorum; F. sambucinum; F. graminearum; Stagonospora nodorum; S. tritici; A. flavus |

pH 4.5-6.2; 52-65 °C |

The enzymatic complex catalyzed hydrolysis of fungal mycelium. |

| Lyticase (enzymatic complex with activity of β-(1-3)-glucan laminaripentaohydrolase, β-(1-3)-glucanase, protease and mannanase) from Arthrobacter luteus [101] | C. albicans | pH 7.3; 25-37 °C | Lyticase provides disruption of yeast cell walls and spores with formation of spheroplasts and further release of DNA from them. |

| Cellobiose dehydrogenase (CDH) and deoxyribonuclease I (DNase) co-immobilized on positively charged chitosan nanoparticles [102] | Polymicrobial biofilms of C. albicans and Staphylococcus aureus | pH 7.5; 37 °C | The action of two enzymes provides a violation of biofilm formation due to the degradation of eDNA, a decrease in the thickness of the biofilm and the death of microbial cells. |

| Enzyme; Origin; Reference | Protease Type | Prion/Amyloid |

|---|---|---|

| Subtilisin homolog Tk-SP from Thermococcus kodakarensis [117] | Serine protease |

abnormal human prion protein |

| Nattokinase from Bacillus subtilis natto [118] | amyloid β fibrils / recombinant human prion protein | |

| Subtilisin 309 from Bacillus lentus [119] | mouse-adapted scrapie prion protein | |

| Prionzyme from Bacillus subtilis [120] | hamster prion protein | |

| Properase from Bacillus lentus [121] | mouse-adapted prion protein | |

| MC3 (Prionzyme) from Bacillus lentus [122] | 301V prion | |

| MSK103 from Bacillus licheniforms [123] | hamster-adapted scrapie prion protein | |

| E77 from Streptomyces sp. [124] | ||

| Pernisine from Aeropyrum pernix [125] | abnormal human prion protein | |

| Protease from lichens (Parmelia sulcata, Cladonia rangiferina and Lobaria pulmonaria) [126] | hamster prion protein | |

| Keratinase from Bacillus licheniformis [127] | yeast prion protein, Sup35NM | |

| Proteinase K [128] | ||

| Keratinase rKP2 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa KS-1 [129] | ||

| Keratinase from Bacillus pumilus KS12 [130] | ||

| Keratinases, Ker1 and Ker2, from Amycolatopsis sp. MBRL 40 [131] |

Metal-activated serine protease | amyloid β fibrills |

| Neprilysin [132] | Zn-dependent metalloprotease | amyloid β fibrills |

| Insulin-degrading enzyme [132] | ||

| A disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM10) [132] |

| QQE [Reference] | Objects of action | Target QSMs |

|---|---|---|

| Gluconolactonase [141] | A. niger | Lactone-containing QSMs |

| His6-OPH [142,143] |

Trichosporon beigelii, Candida sp., S. cerevisiae, Pachysolen tannophilus, Kluyveromyces marxianus |

Lactone-containing QSMs |

| Esterases [144,145] |

Mucor mucedo, Blakeslea trispor Phycomyces blakesleeanus |

Trisporic acids |

| Lipases [146,147,148] |

Malassezia sp., Microsporum canis Leishmania amazonensi |

Lipids with long carbon chain fatty (oleic, linoleic, and linolenic) acids |

| Antifungal formulation [Reference] |

Target fungi | MFC*, mg/L | Comment, [Reference] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose oxidase with NPs of Fe3O4 [40] | C. albicans | 1 mg/mL | Antimicrobial activity |

| Keratinase on green synthesized Ag NPs (5–25 nm) [155] | C. albicans | n/a (DDT) | Antibacterial agent |

| Chitinase on talc (0.2–3 μm) combined with chitin [156] | Sclerotium rolfsii | n/a | Passed field trial |

| Protease and lipase on green synthesized Ag NPs (10–45 nm) [157] |

C. albicans | n/a (DDT) | Antibacterial agent |

| β-1,3-glucanase, chitinase, N-acetylglucosaminidase and acid protease on green synthesized Ag NPs (20–200 nm) [158] |

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum |

n/a (MGT) | Variable sorption capacityof Ag NPs for different enzymes |

| β-1,3-glucanase, chitinase, N-acetylglucosaminidase and acid protease on green synthesized Ag NPs (20–200 nm) [159] |

S. sclerotiorum Beauveria bassiana |

n/a (MGT) | Antibacterial agent |

| Glucose oxidase conjugated with polyglutaraldehyde–β-alanin and covered by Ag shell [160] |

C. albicans Microsporum canis T. rubrum |

n/a (DDT) | Antibacterial agent, cytochrome inhibition |

| Lactoferrin and melittin in Zn–MOF (0.5 μm) [161] | C.albicans | >100 (μDT) | Antibiofilm agent, yeast-to-hyphal inhibitor used in vivo |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).