1. Introduction

Poultry farms are the largest livestock farms and use increasing amounts of anti-microbials and coccidiostats, therefore, have more influence on spreading selective anti-microbial-resistant bacteria in the environment. Broiler chicken producing operations (CAFO) systems and the selective breeding of broilers that grow faster than the previous generation, as well as the crowded factory farming milieu, have effects on the chicken immune system [

1]. Chickens are grown on organic bedding and thus ingest their litter [

2]. All these reasons force the use of anti-microbials and coccidiostats in broiler growing systems. The use of a low minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and residue concentrations of drugs can lead to the development of selective resistant bacteria in the litter. According to EU council directive 2007/43/EC reducing chicken stocking density (from 39 to 33 Kg/m

3) were not effective to reduce the use of antimicrobials [3, 4]. However slower growing chickens with low stock density reduce the use of antimicrobial compared to fast growing chickens [

5]. The organic and slower growing breed farming can reduce the use of anti-microbial but they are more expensive than conventional broiler systems.

According to Witte, the widespread use of anti-microbials that select for communities of resistant bacteria in litter is one of the world’s problems [

6]. The pharmacokinetics of anti-microbials in litter decreases the profile of bacterial susceptibility, such that resistant bacteria grow easily. Animal manure e.g. BL spreads the resistant bacteria to the environment by selective pressure, spontaneous mutation and the unreasonable use of anti-microbials [7; 8]. One of the routes by which anti-microbial resistant bacteria are spread to the environment is via food animal production chain, like poultry, pork and beef. The presence of residue antimicrobials in the environment changes the soil structure and influence on degradation and microorganism diversity [

9]. Use of antimicrobials and their influences on selection antimicrobial bacteria were also studied well [

10]. The residues of sulfadiazine and oxyteteracycline at low MIC were effective to cause selective pressure on resistance population [

11]. However the threshold concentration of antimicrobials still not known enough. The residue antimicrobials in low concentration < MIC and co-selection compounds like coccidiostats needed more study to calculate the selection pressure concentration of residue drugs on resistant bacteria and their chronic and acute ecotoxicity effects on the environment.

The WHO recognized multi-anti-microbial resistance as one of top 10 global public health threats due environment contamination by resistant bacteria. The nosocomial pathogenic ESKAPE (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter spp.) are the most anti-microbial-resistant bacteria that spread and cause challenges to public health in the last decade [

12]. Anti-microbial resistance occurs in nature, with resistance to pencillin having been studied by Abrham and Chain in 1940, soon after Alexander Fleming discovered the drug [

13]. In 1969, Swann also reported the resistance of bacteria to growth promotors and advised against their use [

14]

. Smith’s mathematical modelling studies showed the use of antimicrobials in livestock farm is the major cause to spread resistance bacteria to the environment and human health [

15]. other studies also showed the prevalence of methicillin resistance staphylococcus aureus (MARSA) that were detected more in farmers and their families compared to other populations ( 68.3, 14 and 0.1% respectively; [

16]). The use of non-therapeutic concentration of antimicrobials in animal feed and water were also described in Kawano studies as a cause of selection antimicrobial resistance in manure and environment contamination [

17]. The resistance mechanism of bacteria, target alteration, drug inactivation, impermeability and efflux transfers from one organism to others by conjugation, transduction, transformation and bacteriophage systems were investigated in different researches [

18].

A major additional cause of resistant bacteria increasing in the environment is the non-approved use of anti-microbials in different food producer animals’ chain in the last four decades. In 1930-1962, twenty class of anti-microbials were discovered, however, since then, only a few anti-microbial classes have been approved for use with humans and animals [

19].

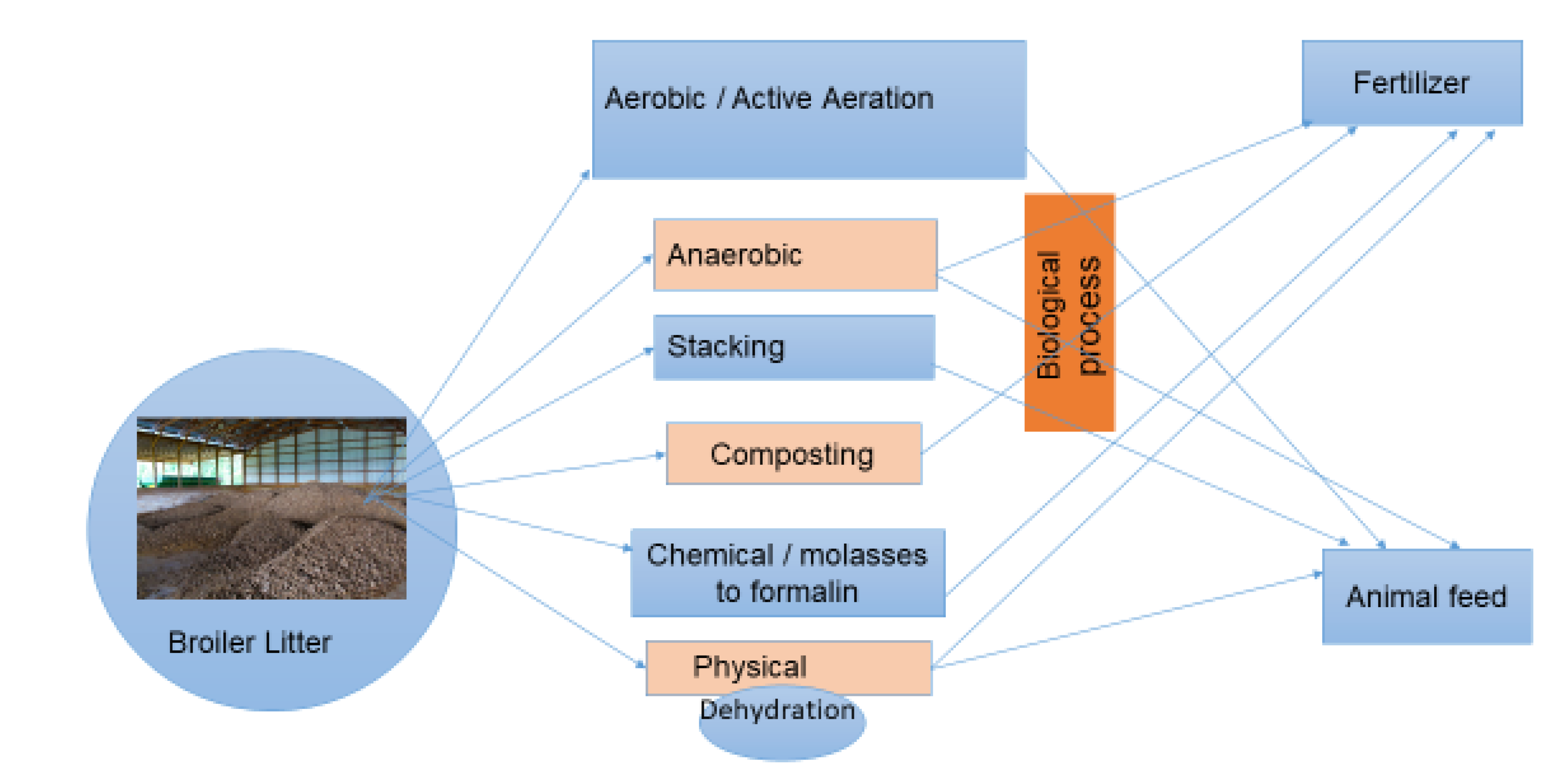

To regulate the treatment processes and safe use of BL as ruminant feed, the cattle producer must vaccinate their cattle to botolism before BL use (Animal feed law, 2014). Accordingly, Israel has regulated the use of BL for feeding ruminant animals since 1971 (Supervision Order, 1971). The cheapest and most widely-used BL treatment technology are microbial treatments. In 1973, Israel regulations require BL to be treated by a drying system at 130ºC. However, this demands more energy, and is expensive for treatment companies and farmers. Therefore, the preferred system used today are microbial treatment systems. The most popular microbial treatments of BL as animal feed in Israel are aerobic (forced aeration), anaerobic (ensiling) and stacking (

Figure 1).

The effect of composting treatments on reduction of pathogenic bacteria in BL were introduced in previous studies [20, 12, 21]. However, not in biotic treatments used as ruminant feed. The profiles of resistant pathogenic bacterial species from conventional and organic broiler farms were examined in only few studies, which focused on chicken organs and carcasses, and not on BL [

22]. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the differences between anti-microbial-dependent and -independent farming, on the effects of treatments and their differences in terms of reduction of four zoonotic bacteria species, Salmonella, Escherichia coli, Enterococcus and S. aureus in BL used as ruminants feed.

2. Results

All BL samples were tested for Enterococcus before treatments, conducted at four locations, were positive. E. faecium was more dominant than E. faecalis, as confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS. E. coli (11%) were also isolated before treatment. The labscale and company-based treatments detected only 7% of the original Enterococcus levels after treatment, and no E. coli were detected. Neither Salmonella nor S. aureus were detected before or after BL treatments. E. coli content in samples collected from windrow three days before treatment reached 26% in the southern and 9% in the north-western treatment companies (

Table 1).

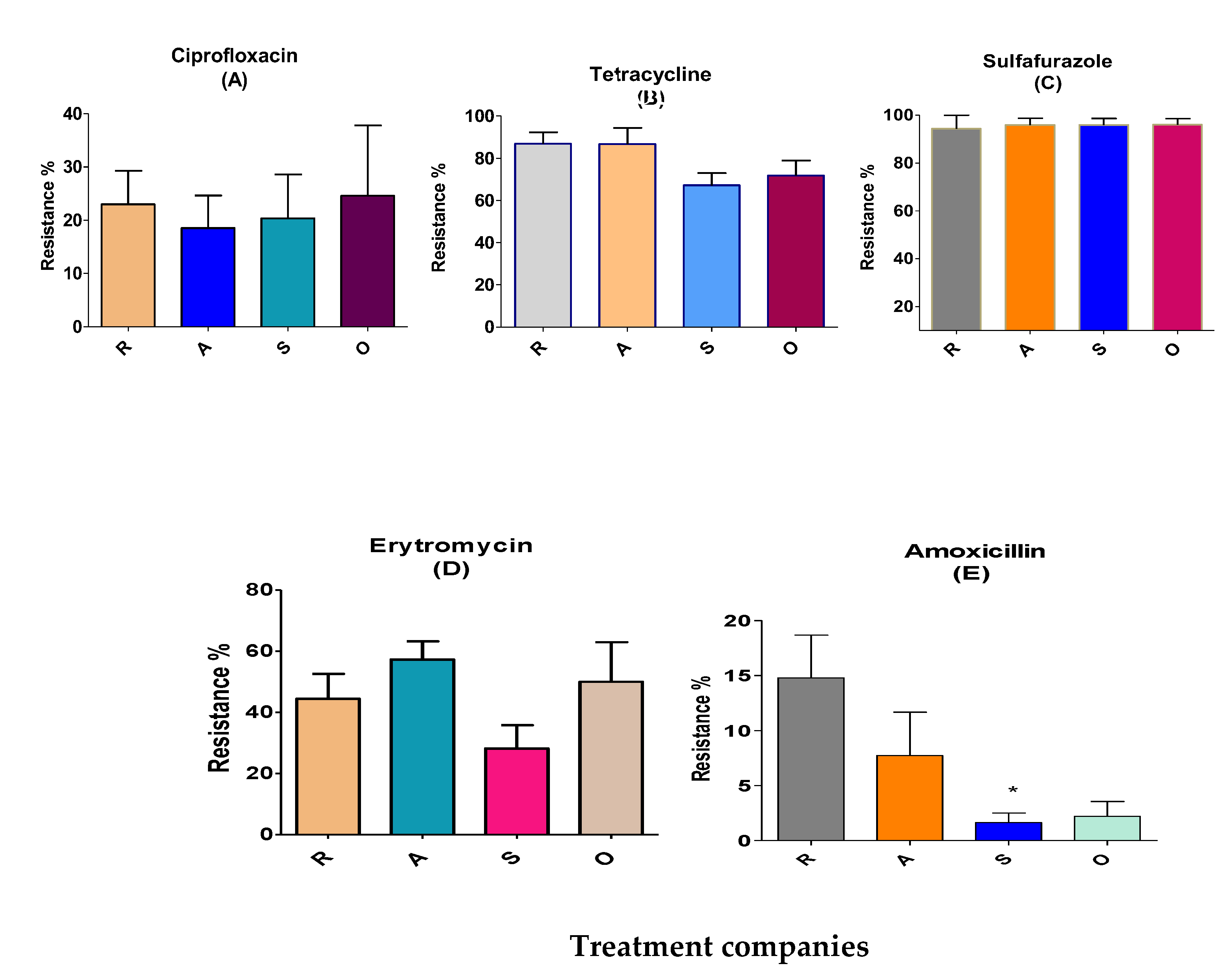

The largest resistance of Enterococcus was towards sulfafurazole and tetracycline, measured as 96 and 78%, respectively. In contrast, resistance to erythromycin, ciprofloxacine and amoxicillin was low (7-45%;

Table 2).

Sulfafurazole-resistant Enterococcus: Sulfafurazole-resistant Enterococcus in 713 colonies before treatment reached levels of 96%. 94% were in treatment company south of Israel (R), and 96% were at other three locations (north west (A), north east (S) and other broiler farms (O) as shown in

Table 2.

Teteracycline-resistant Enterococcus: 78% of the colonies were resistant to teteracycline. The distribution percentage were 87% at the R and A locations, and 67% and 72% at the S and O sites, respectively (

Table 2 and

Figure 2B).

Erythromycin-resistant Enterococcus: Erythromycin is an important anti-microbial group used in human treatments for ß-lactam resistance. The resistance of Enterococcus for erythromycin were 44%, 57%, 28% and 50% at the R, A, S and O locations, respectively (

Figure 2D). Ciprofloxacine resistance distribution was 19-25% at the four locations. Amoxicillin-resistant Enterococcus were few at anti-microbial-independent farm litters in S location (2%) but were more prevalent at the R, A and O locations (8-22%;

Figure 2E).

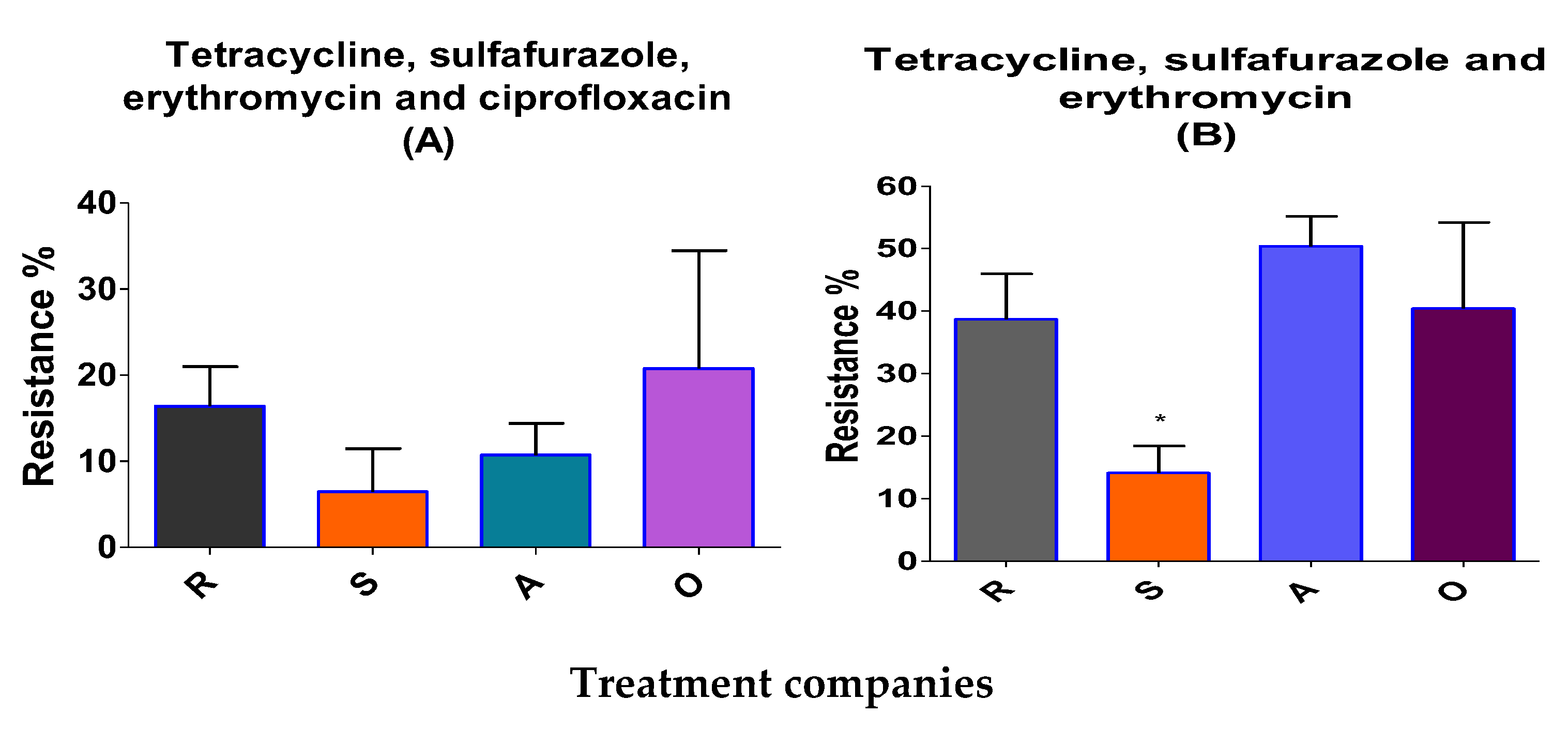

Of 713 isolated resistant Enterococcus colonies, 14 % were multi-resistant to tetracycline, sulfafurazole and erythromycin in anti-microbial-independent farm litters, values significantly were lower than those measured in anti-microbial-dependent broiler farm litter (38.6- 40%;

Figure 3B). There was a medium correlation between sulfufurazole and teteracycline-resistant Enterococcus bacteria (r=0.4,

P≤ 0.01; Table S3). Tetracycline- resistant Enterococcous also correlated with ciprofloxacin and erythromycin-resistant bacteria at the >99.9% level of significance. Erythromycin-resistant bacteria were correlated at a medium level to ciprofloxacin-resistant bacteria (r= 0.562,

P≤ 0.01; Table S3).

3. Discussion

3.1. Evaluation of the effects of different broiler treatments on antibiotic-resistant bacteria

The most readily detected Enterococcus bacteria resistant to teteracycline, amoxicillin, ciprofloxacin and erythromycin are critical priority categories of bacteria, according to the WHO (WHO, 2018. 6th revision ISBN 978-92-4-151552-8). Enterococcus in a healthy person does not cause infection. Indeed, these bacteria normally contribute to intestinal florae [23, 24]. However, immuno-compromised hosts, especially in hospitals, can be easily infected and be afflicted by urinary tract infections, bacteremia or endocarditis disease by E. facium [25, 26]. E. faecalis are the most pathogenic of 50 Enterococcus species to humans [

27]. In the current study, the most commonly Enterococcous spp. detected in BL litter by MALDI-TOF MS were E. faecalis and E. faecium. Broiler litter has the potential for generating resistant bacteria [

20]. Presently, composting treatment systems for fertilizer production are better known than are treatment systems used for preparing BL for use as ruminant feed [28, 20]. Nutrition, moisture content, particle size, age of the litter, aeration condition, size of windrows and treatment systems are the most essential conditions when treating BL and eliminating pathogenic bacteria before use as ruminant feed or fertilizer [

29]. These factors were also of influence in our lab scale treatments we used to achieve a good self-heating decompose and destroyed pathogenic microorganisms.

The biggest difference between composting treatment, aerobic, and stacking treatment processes are the duration of the treatment and the windrows aeration system. Aerobic and stacking treatments take three days and three weeks, respectively, and lead to reductions in moisture to 25-29%. The reduction of moisture is one of the critical concerns in reducing pathogenic bacteria numbers, as shown previously [

30]. Biological treatment methods, namely aerobic treament and stacking, create bio-oxidation and self-heating during treatment. This elevates the temperature gradation and reduces the moisture content. Mesophilic bacteria do not survive temperatures >45°C. The bio-oxidation activity releases heat, CO₂ and moisture from the treated BL into the environment. Due to thermal exposure and ammonia volatilization during the treatment process, pathogenic microorganisms are eliminated from the BL. Previous deep stacking treatment over 2-4 days and lab-scale composting treatments showed similar effects in terms of elimination of pathogenic bacteria, as compared to the treatment performed here [20, 31, 32, 33).

3.2. Relationship between resistant/multi-resistant bacteria and anti-microbial-independent therapy in broiler farms

The resistant Enterococcus isolated from anti-microbial-independent broiler farms (S) were significantly lower in amoxicillin-resistant Enterococcus (P< 0.05). The isolated resistant Enterococcus from anti-microbial-independent BL farms were also more resistant to sulfafurazole, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin and tetracycline, although these increases were not significant (P> 0.05). This finding agrees with previous studies conducted in Canada and US that detected more resistant E. coli in anti-microbial-dependent farms to sulfamethoxazole, amoxicillin and tetracycline, as compared to antibiotic using farms [15, 34,35 ].

The multi-anti-microbial resistant Enterococcus analysis showed results similar to those of Kim and Subirats [20, 22] who studied in chicken carcasses and areas of poultry production. Multiple anti-microbial-resistant (MAR) organisms are of great concern in terms of human and animal health. Infection caused by MAR strains are more critical than are infections caused by single anti-microbial-resistant bacteria. MAR Enterococcus have the ability to transfer genes via plasmids and other mobile genetic elements [36, 37]. E. faecalis and E. faecium correspond to those Enterococcus strains that are the most widely distributed in the environment [

38,

39]. 20% of MRA strains responsible for nosocomial infections in the US are Enterococcus and Staphylococcus strains [41, 42].

Results in the current study showed the differences between BL from anti-microbial-dependent and -independent farms in terms of three different representative anti-microbial-resistant bacteria. E. faecium was more readily detected than E. fecalis. MRA Enterococcus were significantly lower in independent farm BL for tetracycline, sulfafurazole and erythromycin (14%) resistance than were the same bacteria from dependent farms (38.6-40%). However, when we analyzed MRA Enterococcus for resistance to four different representative anti-microbials (tetracycline, sulfafurozole, ciprofloxacin and erythromycin), no significant difference between dependent and independent broiler farms were noted. These differences in the results confirm the unaccepted universal definition regarding multi-drug resistance (“if it is two or more classes of anti-microbials”; [

43]). The occurrences of multi-drug resistance in Enterococcus were low in low antibiotic using farms. Results from the current study thus, show some similarity to those of Kim et al., 2018 and Furtula et al., 2013 on chicken carcasses and areas of poultry production [30, 44].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and reagents

Luria broth and Muller Hinton agar were obtained from Neogen Culture Media (Heywood; U.K), saline from Sigma Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Darmstadt, Germany), glycerol (30%) was from Bio Lab (Jerusalem, Israel). Agar medium, agar blood, MacConkey agar, Xylose, Lysine and Tergitol (XLT 4), and Kenner Fecal (KF) agar were purchased from Becton Dickinson (Bergen, NJ, USA) and Baird-Parker agar was obtained from Oxoid (Basingstoke, UK). The solutions, broth and agars were prepared at the Kimron Veterinary Institute (accredited ISO 17025). E. coli, Salmonella species, S. aureus and Enterococcus species were purchased from the Oxoid (Basingstoke, UK). The strains were used as controls during microbiological diagnostic efforts. The American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) strain numbers for E. coli, Salmonella species, S. aureus and Enterococcus are 19433, 14028, 25922 and 25923 respectively. Anti-microbial disks containin gamoxicillin, ciprofloxacin, teteracycline, erythromycin and sulfurazole for resistance test were purchased from Oxoid (Basingstoke, UK).

4.2. Sample collection

Of 84 batches of samples collected during 2019-2021, half were sampled before treatment by any of three treatment companies (south (S), north west (A) and north east (S) of Israel) or broiler farms (O) and the other half was sampled after treatment by any of three treatment companies or after lab-scale treatment. Samples were collected from nine locations of the litter windrow utilizing by a zigzag pattern. Then, samples placed into a cold container and transferred to the laboratory within 12 hours. Samples were held at 4-8°C pending analysis. Laboratory identification of four pathogenic bacteria was performed at the Department of Bacteriology of the Kimron Veterinary Institute, Rishon Litzion.

4.3. Designing a method for aerobic, anaerobic and stacking BL treatment in the laboratory

BL was taken from the facility over the course of a year. An airflow mechanism (aerobic treatment) containing a 22 kg BL container was attached to a Balma compressed air system (Torino, Italy) for 72 hours. We supplied 4 psi air over 8 minutes, three times on the first day. During the second and third days, we reduced the air amount to maintain the self-heating temperature generated by microorganisms fermentation (Figure S3). The bottom of the plastic containers was drilled to release excess water during the treatment period. At the same time, anaerobic and stacking treatments were carried out in separate containers containing 12 kg of BL over the course of three weeks (Figure S4). The initial moisture contents were balanced to 40 % for all treatments. The four zoonotic resistant bacteria were identified before and after all three treatment.

4.4. Sample preparation

Homogenates of BL samples (5 g) in 50 ml Falcon plastic tubes were weighed on a digital balance and 20 glass beads and 20 ml of Luria broth (Neogen Culture Media, Lansing MI, USA) were added. The samples vortexed for one minute and shaken in a lab shaker for 30 min, diluted 1:10 with Luria broth and grown for 12-18 h in a 38°C incubator (FAO, 2019. ISBN 978-92-5-131930-7) Preparation, storage and quality of the media were examined by the Food Hygiene laboratory at the Kimiron Veterinary Institute.

4.5. Isolation, identification and confirmation

After preparation, samples were centrifuged at 200×g for 5 min at 4˚C. One loopful of the supernatant (0.01 ml) was taken and streaked onto to selective agar, namely MacConkey (pink/red colour; Becton Dickinson, Bergen, NJ ), XLT4 (black; Becton Dickinson, Bergen, NJ), Baird-Parker (grey/black; Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) and Kenner KF (purple; Becton Dickinson, Bergen, NJ) agar to identify E. coli, Salmonella, S. aureus and Enterococcus, respectively. For quality control of each batch, all selective medium were incubated at 38°C for 24 h. As positive controls the four bacteria were directly applied to selective agar. The isolation and identification of pathogenic colonies were according to each manufacturer’s instructions manual.

Twenty isolated colonies from each selective agar were streaked onto blood agar at 38°C and incubated for 24 h. For Gram-positive bacteria, the incubation time was 24-36 h (FAO regional antimicrobial resistance monitoring and surveillance guidelines, 2019). The isolated colonies from agar blood were taken for MALDI-TOF-MS analysis (Bruker, Germany) at the Bacteriology Laboratory of the Kimron Institute for confirmation of their identities [

45].

4.6. Kirby-Bauer test for anti-microbial resistance

The identities environmental bacteria have to be confirmed by other methods due to high false positive rates (50-70%) on selective media [46, 47, 48]. Therefore, colonies were confirmed positive by MALDI-TOF-MS as shown in

Figure S1. The inoculation of colonies in 5 ml of saline served to match the volume of the bacterial inoculum against a 0.5 McFarland standard, thus ensuring that the number of bacterial cells in each diagnostic test to be approximately the same. This was the first step in a Kirby-Bauer test used to assess anti-microbial resistance. A sterile non-toxic cotton swab was dipped into the inoculum saline buffer and rotated firmly against the upper inside wall of the tube to release excess fluid. The entire agar surface was streaked with the swab three times while turning the Mueller Hinton agar plate at 60˚ between each streaking. The inoculums were allowed 5 min to dry, after which time the following anti-microbial-containing disks (sulfofurozile, ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin, erythromycin or tetracycline disks;

Table S1) were applied to Hinton agar and incubated at 37°C for 24-36 h (

Figure S2). Results were interpreted as susceptibility or resistance by measuring the diameter of an inhibition zone according to the criteria stipulated by CLSI 2015 (

Table S2). Negative and positive controls were included in each batch. Each isolated bacteria species was stored in Luria broth containing 25% glycerol at -80°C for further studies.

4.7. Statistical analysis

The prevalence of Enterococcus resistance to five representative anti-microbials, namely, sulfafuraziole, amoxicillin, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin and tetracycline, in BL was investigated by a diffusion disk test. The counts obtained were analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2011 and the statistical package of Prism-GraphPad software (San Diego, CA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and aTukey multiple comparison test were used to check for any significant differences in the means of anti-microbial-resistant Enterococcus counts from the different locations.

5. Conclusions

The source of anti-microbial-resistant bacteria is not solely due to the use of anti-microbials in livestock farming but also because resistance genes have naturally appeared for hundreds of millions of years [

49], inappropriate human use and unregulated prescriptions. In Israel, from 2019, the "one health" principle was introduced in public heath institutes to reduce the resistance bacteria in the environment. However, the one heath principle has not been applied properly to food-producing animals. In our study, resistant Enterococcus from anti-microbial-dependent and -independent farms showed that the low use of anti-microbial is important for reducing anti-microbial-resistant bacteria numbers in animal farms. These Enterococcus showing higher resistance to all anti-microbials were isolated from anti-microbial-user farms, rather than from those using low amounts of anti-microbials

. Due to these reasons, untreated BL used as fertilizer and ruminant feed carry potential of environmental and public hazards.

Most BL used as animal feed are used without treatment. Such untreated BL can be a source of pathogenic bacteria like Salmonella that cause disease in ruminant animals and contaminate the environment. Treatmnts of BL eliminated human and zoonotic disease-causing pathogenic bacteria.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Sample MALDI-TOF MS identification results described in Section 4.6; Figure S2: Streaked colony plates and anti-microbial disks in Muller Hinton medium were incubated at 38°C described in Section 4.6; Figure S3: A compressor and drill jar for active aerobic treatment in a lab-scale study described in Section 4.3; Figure S4: Stacking and anaerobic treatment plastic bins described in Section 4.3. Table S1: Contents of representative anti-microbials in a disk diffusion test described in Section 4.6; Table S2: Table S3: Correlation between anti-microbials and resistance in Enterococcus described in Section 3.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.E., S.B., M.F., S.J.M., and M.B.; methodology, S.E., C.S., S.J.M., and S.B.; software, X.X.; validation, S.E., S.B., S.J.M., and M.B.; formal analysis, S.E. and C.S.; investigation, S.E.; resources, S.E.; data curation, S.E.; writing—original draft preparation, S.E.; writing—review and editing, S.J.M. and M.B.; visualization, S.E.; supervision, S.J.M. and M.B; project administration, S.J.M. and M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by The Chief Scientist, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural development, grant number 33-09-0001”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request from S.J.M.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of PL treatment companies in Israel. The authors thank the chief scientist of the Ministry of Agriculture for partial support of the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hofmann, T.; Schmucker, SS.; Bessei, W.; Grashorn, M.; Stefanski, V. Impact of Housing Environment on the Immune System in Chickens: A Review. Animals (Basel). 2020, 10, 1138. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, SH and Sakaguchi, G. Implication of coprophagy in pathogenesis of chicken botulism. Nihon Juigaku Zasshi. 1989, 51, 582–586. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeith, A.; Loper, M.; Tarrant, K.J. Research Note: Stocking density effects on production qualities of broilers raised without the use of antibiotics. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 698–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarakdjian, J.; Capello, K.; Pasqualin, D.; Cunial, G.; Lorenzetto, M.; Gavazzi, L.; Manca, G.; Di Martino, G. Antimicrobial use in broilers reared at different stocking densities: A retrospective study. Animals. 2020, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilson, Z. The case of the exploded Dutch chickens. Sustainable Food Trust. 2016.

- Witte, W.; Klare, I.; Werner, G. 1999. Selective pressure by antibiotics as feed addi-tives. In Infection. 1999, 27, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Boeckel, T.P.; Brower, C.; Gilbert, M.; Grenfell, B.T.; Levin, S.A.; Robinson, T.P. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, 5649–5654. [CrossRef]

- Manyi-Loh, C.; Mamphweli, S.; Meyer, E.; Okoh, A. Antibiotic use in agricul-ture and its consequential resistance in environmental sources: Potential public health implications. In Molecules. 2018, 23, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, P.L.; and Patrick, D.M. Tracking change: a look at the ecological foot-print of antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance. Antibiotics. 2013, 2, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.C.; Wang, C.Y.; Chu, C.C.; Tan, C.K.; Lu, C.L.; Lee, Y.C.; Huang, Y.T.; Lee, P.I.; Hsueh, P.R. Correlation between antibiotic consumption and resistance of Gram-negative bacteria causing healthcare-associated infections at a university hospital in Taiwan from 2000 to 2009. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011, 66, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaver, A.L. and Matthews, R.A. Effects of oxytetracycline on nitrification in a model aquatic system. Aquaculture. 1994, 123: 237-247.

- Dolliver, H.; Gupta, S.; Noll, S. Antibiotic degradation during manure composting. J. Environ. Qual. 2008, 37, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, A. On the antibacterial action of cultures of a Penicillium with special reference to their use in the isolation of B. influenza. Br J Exp Pathol. 1929, 10, 226–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, M.M.; Baxter, K.L.; Field, H.I. Report of the joint committee on the use of antibiotics in animal husbandry and veterinary medicine. 1969. MHSO.; Lon-don. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.L.; Drum, D.J.V.; Dai, Y.; Kim, J.M.; Sanchez, S.; Maurer, J.J.; Hofacre, C.L.; Lee, M.D. Impact of antimicrobial usage on antimicrobial resistance in commensal Escherichia coli strains colonizing broiler chickens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 1404–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagenaar, J.A. and van der Giessen, A.W. Veegerelateerd MRSA: epidemiologie in dierlijke productieketens, tranmissie naar de mens en karakteristieken van de kloon. Bilthoven: RIVM. 2009.

- Kawano, J.; Shimizu, A.; Saitoh, Y.; Yagi, M.; Saito, T.; Okamoto, R. Isolation of methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci from chickens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996, 34, 2072–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munita J., M.; Arias C., A. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.S. and Buss A. D. Natural products-the future scaffolds for novel antibiot-ics. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 71, 919–929. [Google Scholar]

- Subirats, J.; Murray, R.; Scott, A.; Lau, C.H.F.; Topp, E. Composting of chicken litter from commercial broiler farms reduces the abundance of viable en-teric bacteria, Firmicutes, and selected antibiotic resistance genes. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 746, 141113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y. ; Bin, Zakaria, M. P.; Latif, P.A.; Saari, N. Degradation of veterinary an-tibiotics and hormone during broiler manure composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 131, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Park, J.H.; Seo, K.H. Comparison of the loads and antibiotic-resistance profiles of Enterococcus species from conventional and organic chick-en carcasses in South Korea. In Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devriese, L.; Baele, M.; Butaye, P. The Genus Enterococcus. The Prokary-otes. Springer, New York, NY. 2006, 163-174.

- Hanchi, H.; Mottawea, W.; Sebei, K.; Hammami, R. The genus Enterococcus: Between probiotic potential and safety concerns-an update. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Solache, M. and Rice, L. B. The enterococcus: A model of adaptability to its environment. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiadeh, S.M.J.; Pormohammad, A.; Hashemi, A.; Lak, P. Global prevalence of antibiotic resistance in blood-isolated Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faeci-um: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 2713–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Solache, M and Rice, L. B. The enterococcus: A model of adaptability to its environment. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Esperón, F.; Albero, B.; Ugarte-ruíz, M.; Domínguez, L.; Carballo, M.; Tadeo, J.L.; Delgado, M.; Moreno, M.Á.; Torre, A. De. Assessing the benefits of composting poultry manure in reducing antimicrobial residues, pathogenic bacte-ria, and antimicrobial resistance genes : a field-scale study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 27738–27749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtler, J.B.; Doyle, M.P.; Erickson, M.C.; Jiang, X.; Millner, P.; Sharma, M. Composting to inactivate foodborne pathogens for crop soil application: J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 1821–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Diao, J.; Shepherd, M.W.; Singh, R.; Heringa, S.D.; Gong, C.; Jiang, X. Validating thermal inactivation of Salmonella spp. in fresh and aged chick-en litter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 1302–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, K.G.; Tee, E.; Tomkins, R.B.; Hepworth, G.; Premier, R. Effect of Heating and Aging of Poultry Litter on the Persistence of Enteric Bacteria. Pou. Sci. 2011, 90, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurmessa, B. , Pedretti, E. F., Cocco, S., Cardelli, V., Corti, G. Manure anaer-obic digestion effects and the role of pre- and post-treatments on veterinary anti-biotics and antibiotic resistance genes removal efficiency. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 721, 137532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngquist, C.P. , Mitchell, S. M., Cogger, C.G. Fate of Antibiotics and Anti-biotic Resistance during Digestion and Composting: A Review. Environ. 2016, 45, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chander, Y.; Gupta, S.C.; Kumar, K.; Goyal, S.M.; Murray, H. Antibiotic use and the prevalence of antibiotic resistant bacteria on turkey farms. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2008, 88, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau, A.; Quessy, S.; Guévremont, E.; Houde, A.; Topp, E.; Diarra, M.S.; Letellier, A. Antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli and Enterococcus spp. isolates from commercial broiler chickens receiving growth-promoting doses of bacitracin or virginiamycin. Can. Vet. Res. 2008, 72, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wielders, C.L.; Vriens, S.; Brisse, L.A.; de Graaf-Miltenburg, A.; Troelstra, A. , Fle-er, F. J.; Schmitz, J.; Verhoef, A.C. In-vivo transfer of mecA to Staph-ylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2001, 357, 1674–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, K.L.; Kos, V.N.; Gilmore, M.S. Horizontal gene transfer and the ge-nomics of enterococcal antibiotic resistance. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2010, 13, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.R.; English, L.E.; Carr, D.D.; Wagner, S.W. Multiple-antibiotic resistance of Enterococcus spp. isolated from commercial poultry pro-duction environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 6005–6011. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, J. ; A. Friese, S.; Klees, B.A.; Tenhagen, A.; Fetsch, U.; Rosler, J. Longitudinal study of the contamination of air and of soil surfaces in the vicinity of pig barns by livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphy-lococcus aureus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 5666–5671. [Google Scholar]

- Kayser, F.H. Safety aspects of enterococci from the medical point of view. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 88, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorr, A.F. Epidemiolog y of staphylococcal resistance. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 45, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magill, S.S.; Edwards, J.R.; Bamberg, W.; Beldavs, Z.G.; Dumyati, G.; Kainer, M.A.; Lynfield, R.; Maloney, M.; McAllister-Hollod, L.; Nadle, J.; Ray, S.M.; Thompson, D.L.; Wilson, L.E.; Fridkin, S.K. Multistate Point-Prevalence Survey of Health Care–Associated Infections for the Emerging In-fections Program Healthcare-Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Use Prevalence Survey Team * Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014, 370, 1198–1208. [CrossRef]

- Khurana, C.M.; Wojack, B.R. Prevalence of ciprofloxacin resistance in multiresistant Gram-negative intensive care unit isolates. Infection. 1994, 22, S99–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtula, V. , Jackson, C. R., Farrell, E.G., Barrett, J.B., Hiott, L.M., Chambers, P.A. Antimicrobial resistance in Enterococcus spp. isolated from environmental samples in an area of intensive poultry production. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2013, 10, 1020–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, N.; Kumar, M.; Kanaujia, P.K.; Virdi, J.S. MALDI-TOF mass spec-trometry: An emerging technology for microbial identification and diagnosis. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peplow, M.O.; Correa-Prisant, M.; Stebbins, M.E.; Jones, F.; Davies, P. Sen-si-tivity, specificity and predictive values of three Salmonella rapid detection kits using fresh and frozen poultry environmental samples versus those of standard plating. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65:1055–1060.

- Roberts, M.C.; Meschke, J.S.; Soge, O.O., K. A. ; Reynolds, K.A. Com-ment on MRSA studies in high school wrestling and athletic training facili-ties. Envi-ron. Health. 2010, 72, 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- McLain, J.E.T.; Rock, C.M.; Lohse, K.; Walworth, J. False positive identifica-tion of Escherichia coli in treated municipal wastewater and wastewater-irrigated soils. Can. J. Microbiol. 2011, 57, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminov, R. I and Mackie, R. I. Evolution and ecology of antibiotic resistance genes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2007, 27, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).