1. Introduction

Flavor mainly results from the combination of three senses: taste, somatosensation, and olfaction. Taste and somatosensation are perceived in the mouth, and, thus, are distinguished from olfaction as oral sensations. Taste, which is detected by taste receptors on the tongue, generates sensations of sweetness, sourness, bitterness, saltiness, umami, and other potential sensations [

1]. Sugars and sweeteners have been shown to elicit sweetness by activating T1R2/T1R3 [

2]. Furthermore, volatile flavor compounds with an odor were found to affect the taste of food products [

3,

4]. Previous studies demonstrated that strawberry flavor enhanced sweetness, while flavor compounds containing soy sauce enhanced saltiness [

5,

6,

7]. In addition, volatile aroma compounds affected taste intensity at concentrations below the odor detection threshold [

3,

4]. Short-chain aliphatic aldehydes, such as isovaleraldehyde (IVAH) and 2-methylbutyraldehyde, are natural volatile aroma compounds, which are key flavors generated by the Maillard reaction of sugars and amino acids in the process of manufacturing food products, such as cheese, soy sauce, and sake [

8,

9]. The addition of these aldehydes to a basic taste solution or foods at concentrations below the odor detection threshold was found to enhance the intensities of sweet, umami, and salty tastes without imparting a smell [

10,

11]. A recent study reported that methional, a well-known flavor compound in cheese and soy sauce with an aldehyde structure containing sulfur, functioned as a positive allosteric modulator (PAM) for the human umami receptors T1R1/T1R3 [

12]. Other studies demonstrated that methional enhanced salty [

13] and umami [

14] tastes in human sensory evaluation tests. Therefore, aldehydes, including methional, may enhance the intensities of multiple basic tastes by activating the taste receptors expressed on the tongue. However, the receptors involved in the enhancement of multiple tastes have not yet been clarified.

γ-Glutamyl peptides, including γ-glutamyl-valyl-glycine (γ-EVG) and glutathione (GSH) [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20], are taste modulators that enhance the taste intensities of sweetness, saltiness, and umami as well as the mouthfeel, such as fattiness [

21] and pungency [

22]. They have no taste at the concentrations used and are now known as

kokumi substances. The addition of

kokumi substances to basic taste solutions or food enhances the intensities of thickness, mouthfulness, and continuity, which, in turn, increase taste intensity. Ohsu et al. [

19] and Maruyama et al. [

23] suggested that the activation of the calcium-sensing receptor CaSR by

kokumi substances is involved in the taste-enhancing effects of

kokumi substances.

We hypothesized that CaSR expressed on the tongue is involved in the taste-enhancing effects of aliphatic aldehydes. Therefore, the present study investigated the relationship between the activation of CaSR and the taste-enhancing effects of aliphatic aldehydes using a sensory evaluation and cell-based CaSR receptor assay. The results obtained showed the activation of CaSR by short-chain aliphatic aldehydes and suggest that these aldehydes function as taste modulators that modify oral sensations by activating CaSR expressed in the oral cavity.

4. Discussion

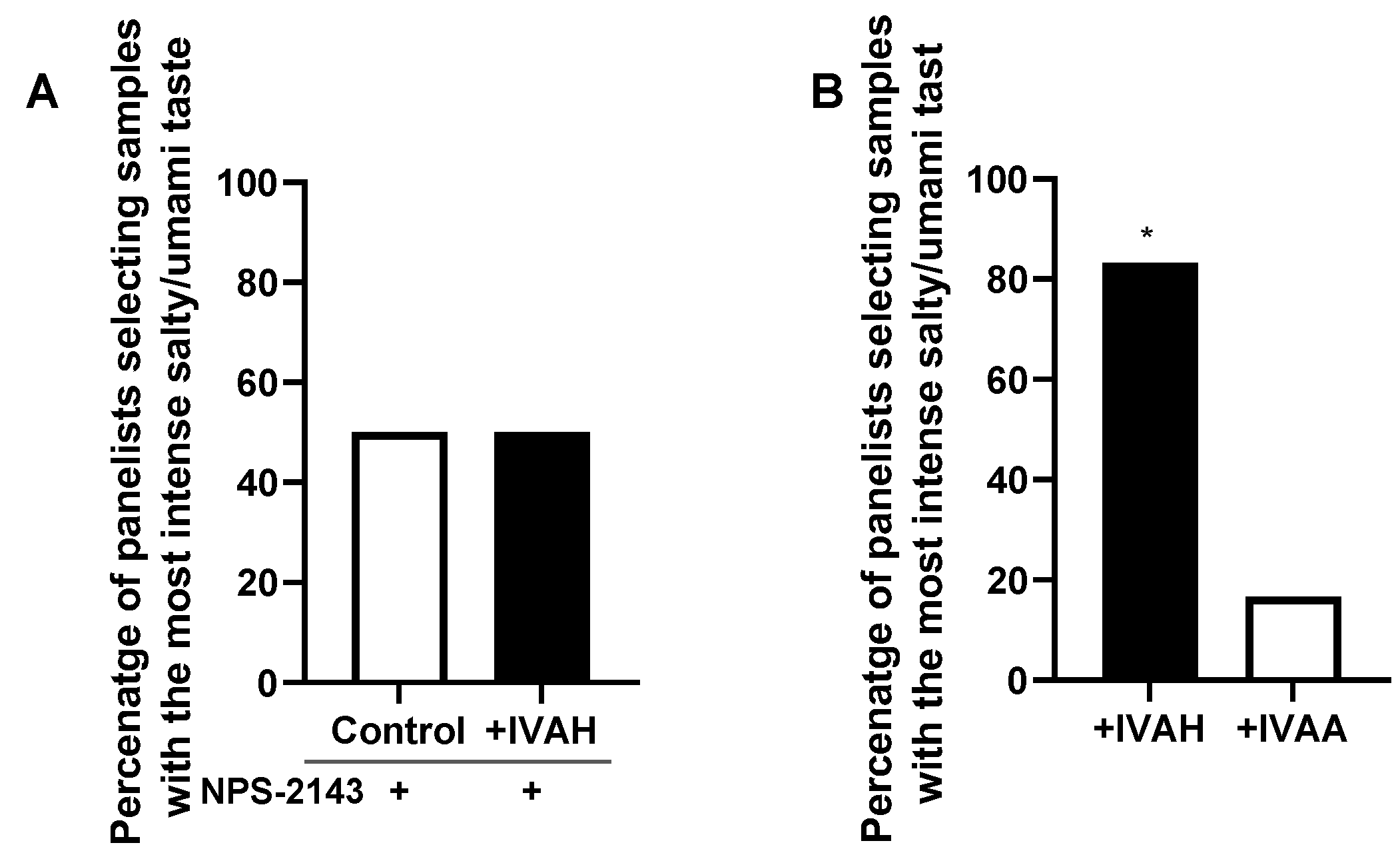

The present study was conducted to elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which aliphatic short-chain aldehydes exert taste-enhancing effects. In sensory evaluations, IVAH was used as a typical short-chain aldehyde to confirm its taste-enhancing effects. The results obtained showed that the taste intensities of umami and salty solutions were significantly enhanced with and without nose clips (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Therefore, the effects of the volatile aroma compound IVAH on the oral cavity appear to contribute to its taste-enhancing effects. IVAH in the sensory evaluations was added at a concentration close to the odor perception threshold reported by Chen [

9] and is tasteless. Therefore, the functionality of IVAH appears to be similar to that of

kokumi substances, which have no taste by themselves, but enhance taste intensity when added to a basic taste solution, as reported by Ueda et al. [

17]. On the other hand, this result does not exclude that the odor of IVAH enhanced taste, but suggests that part of its taste-enhancing effect is elicited by oral stimuli, as shown in

Figure 1B, in which the percentage of panelists selecting the IVAH sample decreased when a nose clip was attached.

GSH is a tripeptide that has been identified as a

kokumi substance [

27]. Similar to other γ-glutamyl peptides, GSH has been shown to enhance the intensities of the basic tastes by activating CaSR [

19], which is expressed on taste cells in the tongue [

23]. Therefore, we investigated whether IVAH and other short-chain aliphatic aldehydes activated CaSR as well as GSH and other γ-glutamyl peptides using a cell-based assay on CaSR-expressing cells. As shown in

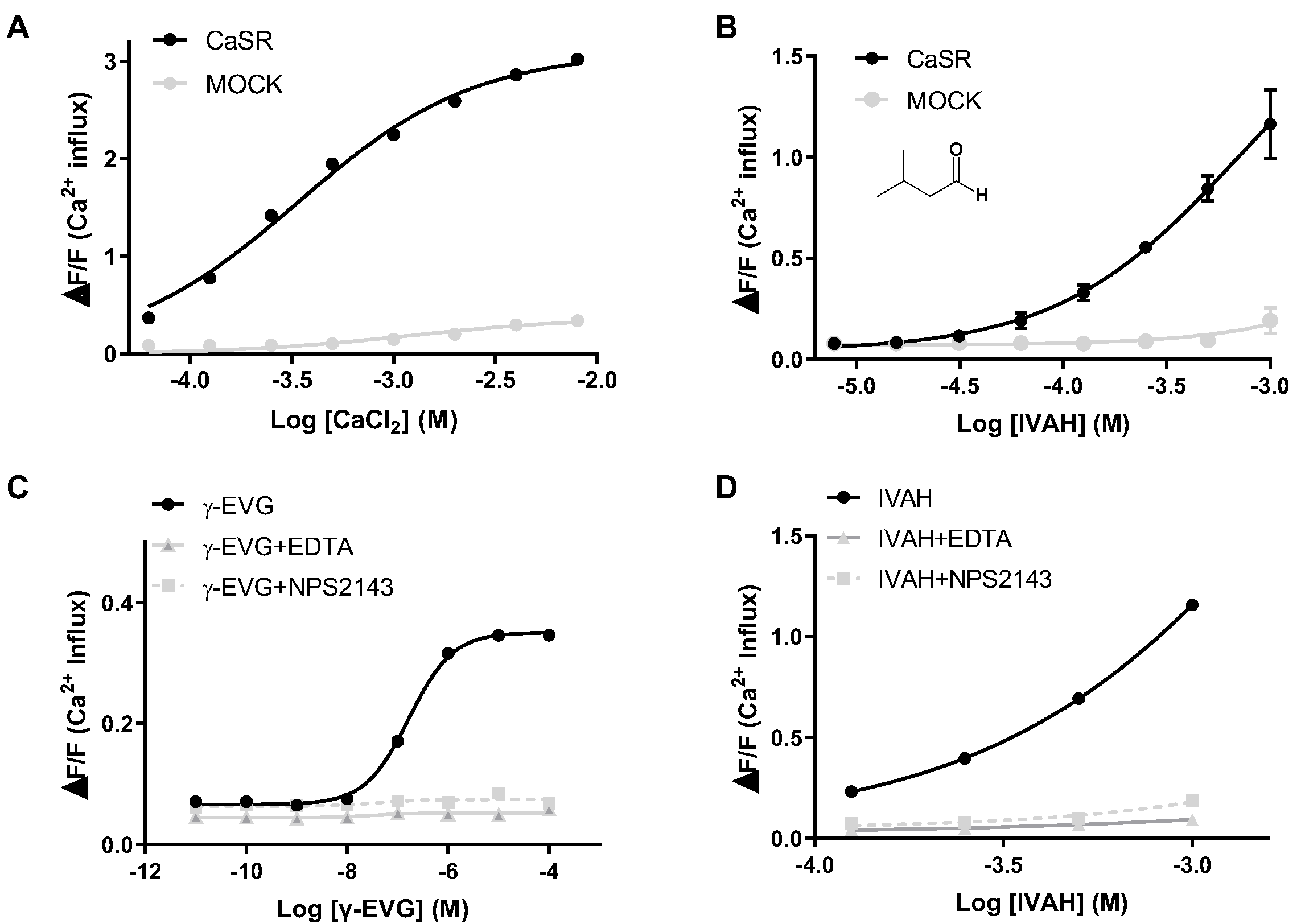

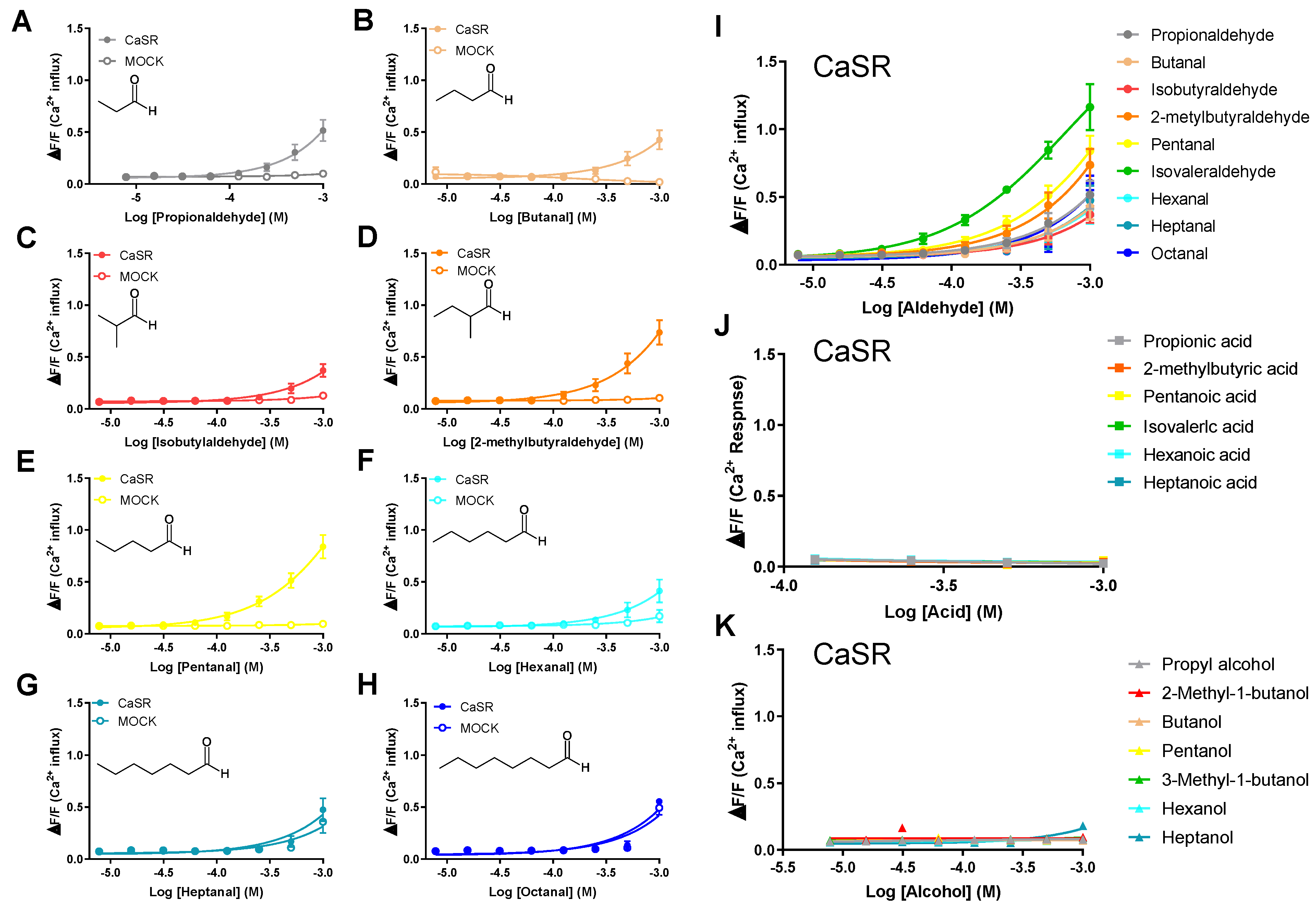

Figure 3, C3-C6 aldehydes selectively activated CaSR. The selective inhibitor of CaSR, NPS-2143, inhibited its activation, suggesting the carbon number-dependent activation of CaSR by aliphatic aldehydes (

Figure 2). Although CaSR was previously shown to be activated by a wide spectrum of amino acids, there is no evidence to support its activation by aldehydes. IVAH is generated from leucin in the fermented food. On the other hand, leucin and aliphatic amino acids have not been reported to activate CaSR [

28]. CaSR may be involved in the sensing of not only amino acids, but also their metabolites, and it may also be indirectly involved in the sensing of these amino acids. Although we focused on aliphatic aldehydes in the present study, CaSR is also activated by aromatic amino acids, such as tyrosine and phenylalanine [

28]. Therefore, future studies on the activation function of CaSR by aromatic aldehydes will provide a more detailed understanding of the relationship between chemical structures and its activation.

As shown in

Figure 5, IVAH, as well as the γ-Glu peptide γ-EVG, exhibited activity as a PAM that enhanced the responsiveness of CaSR to calcium. In addition, the sulfur-containing the volatile compound methional, which has a similar structure to aliphatic short-chain aldehydes that activate CaSR, activated CaSR and functioned as a PAM of CaSR. Toda et al. reported that methional bound to the transmembrane region of human T1R1, a constituent molecule of the human umami taste receptor, and functioned as a PAM [

12]. Class C GPCRs are mainly activated by amino acids and their analogues. They are characterized by an extracellular region called the Venus Fly Trap module. The amino acid sequence of the extracellular region is diverse among receptor gene species and is considered to significantly contribute to ligand selectivity [

29]. On the other hand, the transmembrane region was found to have higher homology than the extracellular region [

12,

30]. Therefore, short-chain aliphatic aldehydes, including methional, may also bind to the transmembrane membrane region of CaSR and function as PAM. However, the activation of CaSR by amino acids requires binding to the extracellular region near the calcium-binding domain [

28]. Therefore, further studies are needed to elucidate the binding site and mode of action responsible for the activation of CaSR.

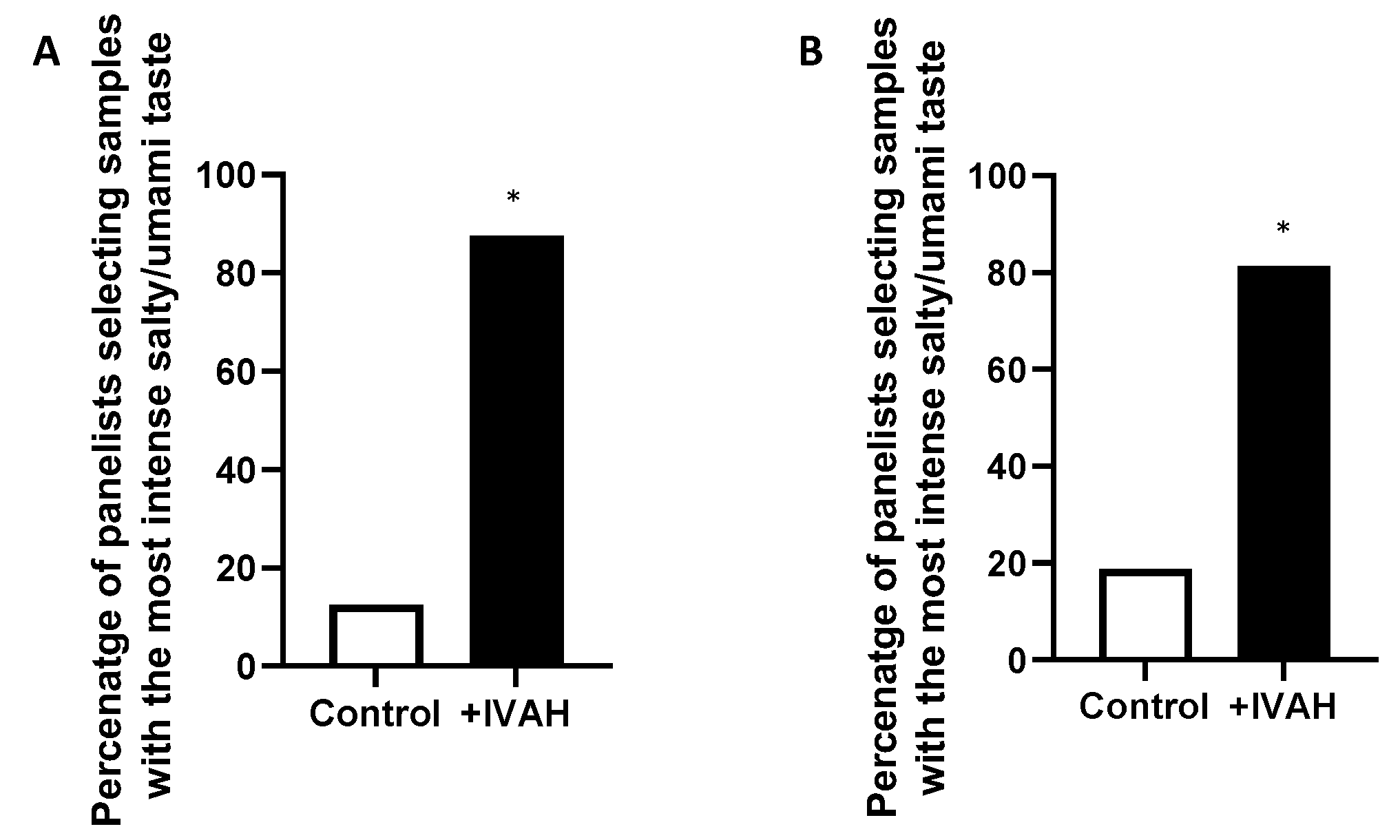

The relationship between the activation of CaSR of aldehydes observed in vitro and taste-enhancing effects in the sensory evaluation was investigated in

Figure 6A. The co-addition of the CaSR antagonist NPS-2143 abolished the taste-enhancing effects of IVAH. Furthermore, IVAH exerted significantly stronger taste-enhancing effects than IVAA, which does not activate CaSR. These results suggest that the activation state of CaSR correlates with taste-enhancing effects in human sensory evaluations, indicating that the activation of CaSR expressed in the oral cavity is involved in the taste-enhancing effects of IVAH. The concentration of IVAH at which taste-enhancing effects was observed in the sensory evaluation in the present study was very low at 2 ppb (0.02 μM), which is different from the concentration that activates CaSR

in vitro. Since IVAH functions as a PAM for CaSR, its ability to activate CaSR depends on the concentration of calcium. Furthermore, there are other amino acids in saliva that activate CaSR and these amino acids may act synergistically and affect the functionality of IVAH.

CaSR is also activated by aromatic amino acids, such as tyrosine and phenylalanine. Therefore, further studies on the activation of CaSR by aromatic aldehydes will provide more detailed information on the relationship between chemical structures and its activation. Besides amino acids, a number of components in food are known to activate CaSR, including metals, such as magnesium, poly-cations (spermine) [

31], peptides derived from soybeans (β51-63) [

32,

33], and pH [

34]. Furthermore, in the present study, CaSR was activated by volatile aldehydes; therefore, a number of food ligands may act on CaSR. Further research is needed to establish whether there are differences in the ligand-binding sites of these components and the resulting taste characteristics. The physiological benefits of the sensing of these various ligands by CaSR expressed on taste cells also warranted further study.

Aldehydes are generated during the fermentation process of fermented foods, such as cheese and sake [

8]. These components may enhance the taste of food and contribute to their palatability through their function as

kokumi substances via the activation of CaSR in the oral cavity in addition to their odor.

Kokumi substances modify mouthfeel sensations, such as thickness, continuity, and mouthfulness [

17], and the functions of these aldehydes in food as

kokumi substances may play a role in taste sensations, such as richness perceived in fermented foods. Further studies are needed on this complex taste contribution.

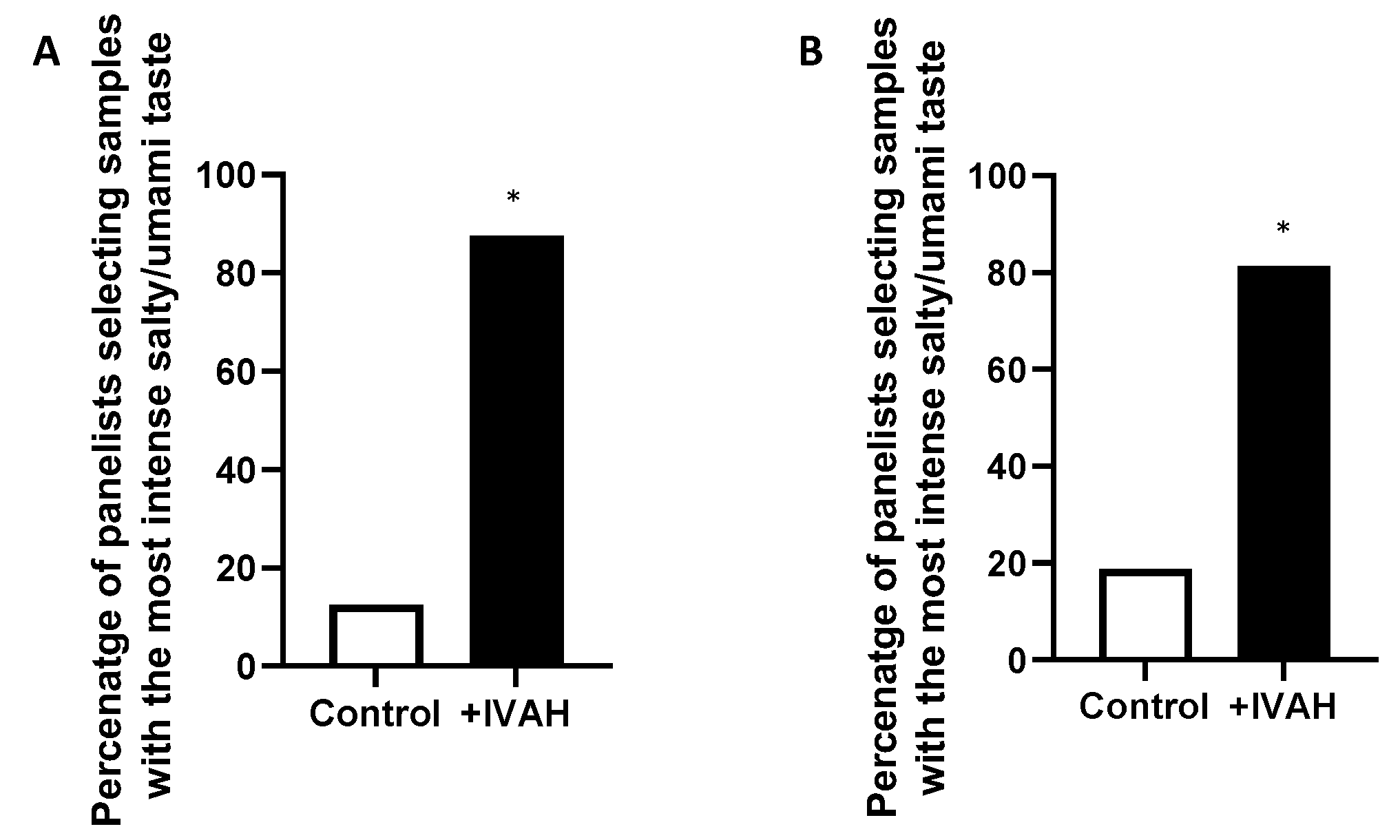

Figure 1.

Taste-enhancing effects of isovaleraldehyde (IVAH) on umami and salty taste solutions. (A) The taste-enhancing effects of IVAH on salty and umami taste solutions of 0.5% NaCl and 0.1% MSG, respectively, were assessed by the two-alternative forced-choice test (2-AFC). Panelists were presented with a taste solution alone or that plus 2 ppb IVAH in three random orders and were asked to select the solution with the most intense salty and umami tastes. Data are shown as the percentage of panelists (out of 16) that selected a given solution as that with the most intense taste. We found that 87.5% of panelists selected the solution with IVAH as that with the most intense taste (p < 0.05). (B) The taste-enhancing effects of IVAH on salty and umami taste solutions with nose clips. Panelists with nose clips were presented with the same taste solution alone or that plus IVAH and were asked to select the solution with the most intense salty and umami tastes. Data are shown as the percentage of panelists (out of 16) that selected a given solution as that with the most intense taste. We found that 81.3% of panelists selected the solution with IVAH as that with the most intense taste (p < 0.05). The significance of differences is indicated above the bar (* p <0.05) and was evaluated by a binomial analysis.

Figure 1.

Taste-enhancing effects of isovaleraldehyde (IVAH) on umami and salty taste solutions. (A) The taste-enhancing effects of IVAH on salty and umami taste solutions of 0.5% NaCl and 0.1% MSG, respectively, were assessed by the two-alternative forced-choice test (2-AFC). Panelists were presented with a taste solution alone or that plus 2 ppb IVAH in three random orders and were asked to select the solution with the most intense salty and umami tastes. Data are shown as the percentage of panelists (out of 16) that selected a given solution as that with the most intense taste. We found that 87.5% of panelists selected the solution with IVAH as that with the most intense taste (p < 0.05). (B) The taste-enhancing effects of IVAH on salty and umami taste solutions with nose clips. Panelists with nose clips were presented with the same taste solution alone or that plus IVAH and were asked to select the solution with the most intense salty and umami tastes. Data are shown as the percentage of panelists (out of 16) that selected a given solution as that with the most intense taste. We found that 81.3% of panelists selected the solution with IVAH as that with the most intense taste (p < 0.05). The significance of differences is indicated above the bar (* p <0.05) and was evaluated by a binomial analysis.

Figure 2.

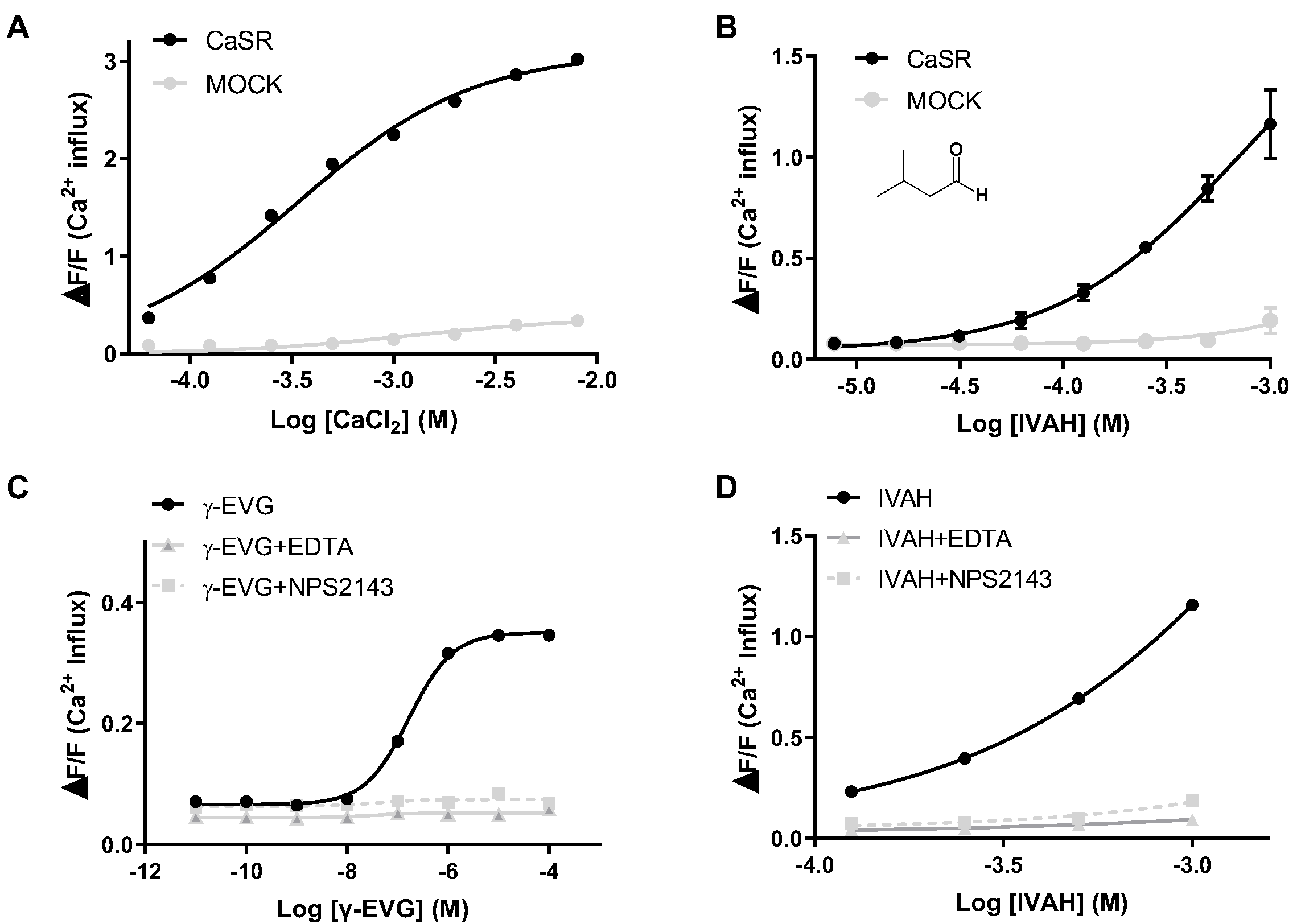

Human CaSR responds to IVAH. Dose-response curves of CaSR stimulated with a CaSR ligand and IVAH. PEAKrapid cells transiently transfected with human CaSR cDNA (black circles, black line) or MOCK (gray circles, gray line = negative control) were stimulated with increasing concentrations of each compound. Changes in fluorescence (y-axis, ΔF/F) were plotted against agonist concentrations (x-axis, logarithmically scaled). (A) CaSR stimulated with calcium chloride resulted in receptor activation (EC50 = 338 μM); (B) CaSR stimulated with IVAH resulted in receptor activation (EC50 = 681 μM); (C) Dose-response curves for γ-EVG were prepared, and the effects of 1 mM EDTA and 20 μM NPS2143 were examined. CaSR stimulated with γ-EVG resulted in receptor activation (EC50 = 0.167 μM). CaSR activation by γ-EVG was attenuated by the co-addition of 1 mM EDTA (gray triangle, gray line) or 20 μM NPS2143 (gray square, gray dashed line); (D) Dose-response curves for IVAH were prepared, and the effects of EDTA (gray triangle, gray line) and NPS2143 (gray square, gray dashed line) were examined. CaSR activation by IVAH was attenuated by the co-addition of EDTA or NPS2143. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error.

Figure 2.

Human CaSR responds to IVAH. Dose-response curves of CaSR stimulated with a CaSR ligand and IVAH. PEAKrapid cells transiently transfected with human CaSR cDNA (black circles, black line) or MOCK (gray circles, gray line = negative control) were stimulated with increasing concentrations of each compound. Changes in fluorescence (y-axis, ΔF/F) were plotted against agonist concentrations (x-axis, logarithmically scaled). (A) CaSR stimulated with calcium chloride resulted in receptor activation (EC50 = 338 μM); (B) CaSR stimulated with IVAH resulted in receptor activation (EC50 = 681 μM); (C) Dose-response curves for γ-EVG were prepared, and the effects of 1 mM EDTA and 20 μM NPS2143 were examined. CaSR stimulated with γ-EVG resulted in receptor activation (EC50 = 0.167 μM). CaSR activation by γ-EVG was attenuated by the co-addition of 1 mM EDTA (gray triangle, gray line) or 20 μM NPS2143 (gray square, gray dashed line); (D) Dose-response curves for IVAH were prepared, and the effects of EDTA (gray triangle, gray line) and NPS2143 (gray square, gray dashed line) were examined. CaSR activation by IVAH was attenuated by the co-addition of EDTA or NPS2143. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error.

Figure 3.

Human CaSR responds to aldehydes. Dose-response curves of CaSR stimulated with C3-C8 aldehydes, acid analogues, and alcohol analogues. PEAKrapid cells transiently transfected with human CaSR cDNA (filled circles) or MOCK (open circles) were stimulated with increasing concentrations of each aldehyde, acid analogue (filled triangles), and alcohol analogue (filled squares). Changes in fluorescence (y-axis, ΔF/F) were plotted against agonist concentrations (x-axis, logarithmically scaled). CaSR was activated by propionaldehyde (A), butanal (B), isobutylaldehyde (C), 2-methylbutylaldehyde, pentanal (D), hexanal (E), and IVAH (I). CaSR stimulated with heptanal (G), octanal, (H), acid analogues (J), and alcohol analogues (K) did not result in receptor activation. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error.

Figure 3.

Human CaSR responds to aldehydes. Dose-response curves of CaSR stimulated with C3-C8 aldehydes, acid analogues, and alcohol analogues. PEAKrapid cells transiently transfected with human CaSR cDNA (filled circles) or MOCK (open circles) were stimulated with increasing concentrations of each aldehyde, acid analogue (filled triangles), and alcohol analogue (filled squares). Changes in fluorescence (y-axis, ΔF/F) were plotted against agonist concentrations (x-axis, logarithmically scaled). CaSR was activated by propionaldehyde (A), butanal (B), isobutylaldehyde (C), 2-methylbutylaldehyde, pentanal (D), hexanal (E), and IVAH (I). CaSR stimulated with heptanal (G), octanal, (H), acid analogues (J), and alcohol analogues (K) did not result in receptor activation. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error.

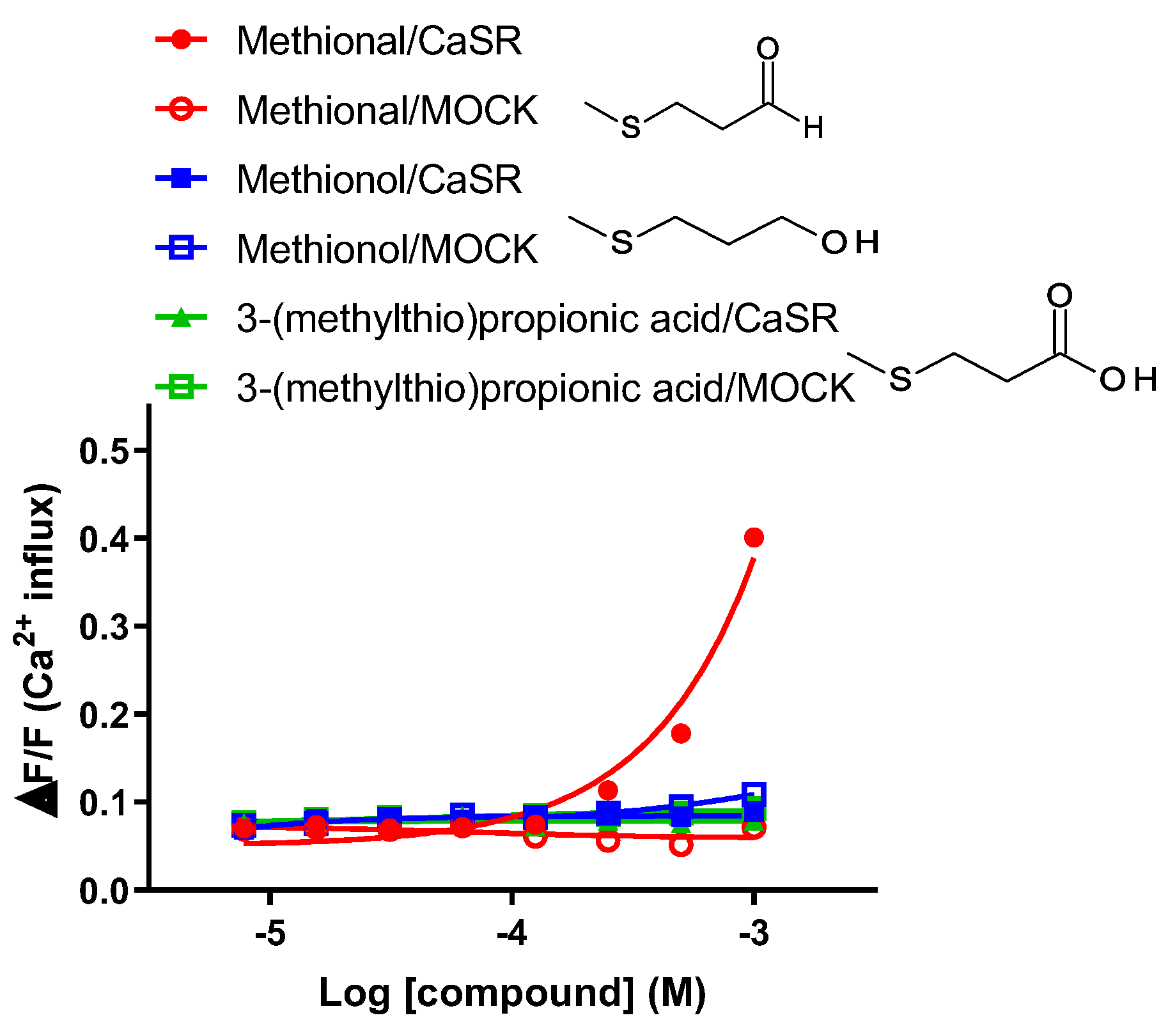

Figure 4.

Human CaSR responds to the sulfur-containing aldehyde methional. Dose-response curves of CaSR stimulated with methional, its alcohol analogue methionol, and the acid analogue 3-(methylthiol)propanic acid. PEAKrapid cells transiently transfected with human CaSR cDNA (filled marks) or MOCK (open marks) were stimulated with increasing concentrations of methional, methionol (filled squares), and 3-(methylthiol)propanic acid (filled triangles). Changes in fluorescence (y-axis, ΔF/F) were plotted against agonist concentrations (x-axis, logarithmically scaled). CaSR was activated by methional. Methionol and 3-(methylthiol)propanic acid did not result in receptor activation. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error.

Figure 4.

Human CaSR responds to the sulfur-containing aldehyde methional. Dose-response curves of CaSR stimulated with methional, its alcohol analogue methionol, and the acid analogue 3-(methylthiol)propanic acid. PEAKrapid cells transiently transfected with human CaSR cDNA (filled marks) or MOCK (open marks) were stimulated with increasing concentrations of methional, methionol (filled squares), and 3-(methylthiol)propanic acid (filled triangles). Changes in fluorescence (y-axis, ΔF/F) were plotted against agonist concentrations (x-axis, logarithmically scaled). CaSR was activated by methional. Methionol and 3-(methylthiol)propanic acid did not result in receptor activation. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error.

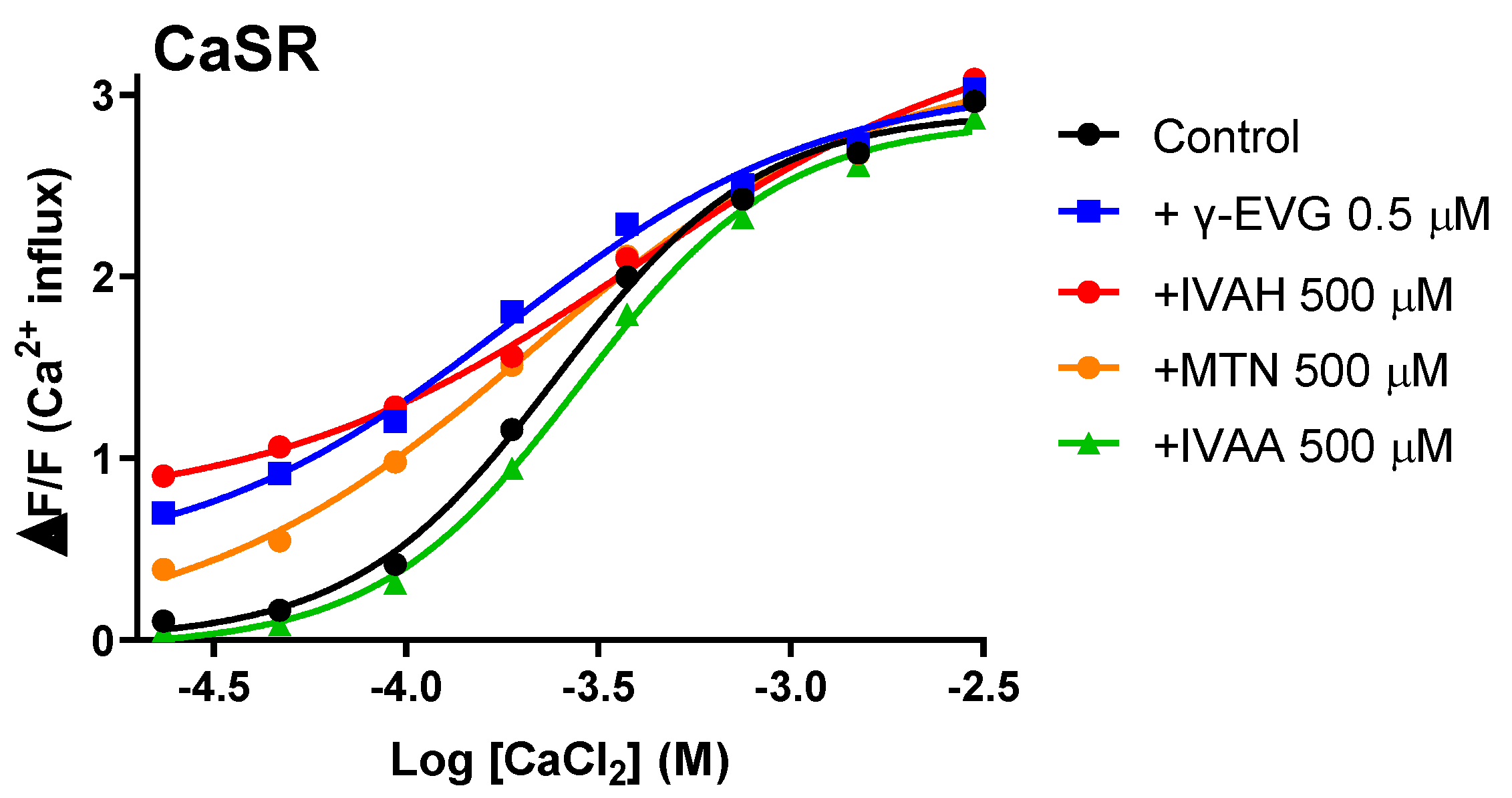

Figure 5.

Aldehydes act as positive allosteric modulators for human CaSR. Dose-response curves of CaSR to calcium chloride were obtained in the presence and absence of IVAH (500 μM), methional (MTN, 500 μM), γ-EVG (0.5 μM), and isovaleric acid (IVAA, 500 μM). PEAKrapid cells transiently transfected with human CaSR cDNA were stimulated with increasing concentrations of calcium chloride in the presence of DMSO (black circles, negative control), IVAH (red circles), methional (MTN, 500 μM, orange circles), γ-EVG (0.5 μM, blue squares), and isovaleric acid (IVAA, 500 μM, green triangles). Changes in fluorescence (y-axis, ΔF/F) were plotted against agonist concentrations (x-axis, logarithmically scaled). IVAH, methional, and γ-EVG enhanced the response of CaSR to calcium chloride, whereas isovaleric acid did not.

Figure 5.

Aldehydes act as positive allosteric modulators for human CaSR. Dose-response curves of CaSR to calcium chloride were obtained in the presence and absence of IVAH (500 μM), methional (MTN, 500 μM), γ-EVG (0.5 μM), and isovaleric acid (IVAA, 500 μM). PEAKrapid cells transiently transfected with human CaSR cDNA were stimulated with increasing concentrations of calcium chloride in the presence of DMSO (black circles, negative control), IVAH (red circles), methional (MTN, 500 μM, orange circles), γ-EVG (0.5 μM, blue squares), and isovaleric acid (IVAA, 500 μM, green triangles). Changes in fluorescence (y-axis, ΔF/F) were plotted against agonist concentrations (x-axis, logarithmically scaled). IVAH, methional, and γ-EVG enhanced the response of CaSR to calcium chloride, whereas isovaleric acid did not.

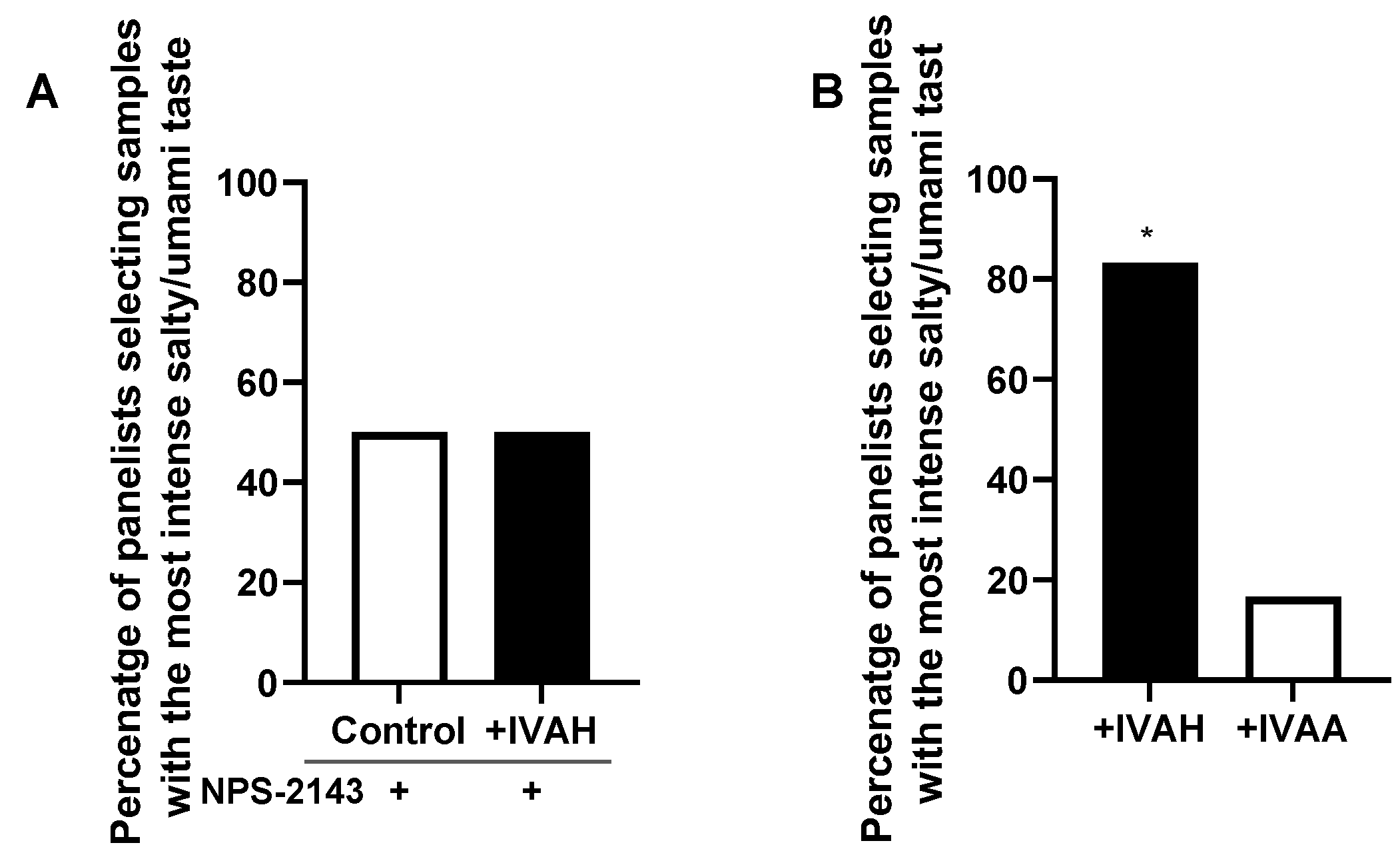

Figure 6.

Relationship between taste-enhancing effects and CaSR activity. (A) The taste-enhancing effects of IVAH on salty and umami taste solutions in the presence or absence of NPS-2143 (5 ppm, 10.4 μM) were assessed by 2-AFC. Panelists with nose clips were presented with the taste solution alone or that plus 2 ppb IVAH in three random orders and were asked to select the solution with the most intense salty and umami tastes. Data are shown as the percentage of panelists (out of 16) that selected a given solution as that with the most intense taste. No significant differences were observed in the perceived intensities of the salty and umami tastes. (B) The taste-enhancing effects of IVAH and IVAA were compared. Compounds with higher taste-enhancing effects on salty and umami taste solutions were examined by 2-AFC. Panelists were presented with taste solutions with 2 ppb IVAH or IVAH in three random orders and were asked to select the solution with the most intense salty and umami tastes. Data are shown as the percentage of panelists (out of 16) that selected a given solution as that with the most intense taste. We found that 83.3% of panelists selected IVAH-added solution as that with the most intense taste (p < 0.05). The significance of differences is indicated above the bar (* p <0.05) and was evaluated by a binomial analysis.

Figure 6.

Relationship between taste-enhancing effects and CaSR activity. (A) The taste-enhancing effects of IVAH on salty and umami taste solutions in the presence or absence of NPS-2143 (5 ppm, 10.4 μM) were assessed by 2-AFC. Panelists with nose clips were presented with the taste solution alone or that plus 2 ppb IVAH in three random orders and were asked to select the solution with the most intense salty and umami tastes. Data are shown as the percentage of panelists (out of 16) that selected a given solution as that with the most intense taste. No significant differences were observed in the perceived intensities of the salty and umami tastes. (B) The taste-enhancing effects of IVAH and IVAA were compared. Compounds with higher taste-enhancing effects on salty and umami taste solutions were examined by 2-AFC. Panelists were presented with taste solutions with 2 ppb IVAH or IVAH in three random orders and were asked to select the solution with the most intense salty and umami tastes. Data are shown as the percentage of panelists (out of 16) that selected a given solution as that with the most intense taste. We found that 83.3% of panelists selected IVAH-added solution as that with the most intense taste (p < 0.05). The significance of differences is indicated above the bar (* p <0.05) and was evaluated by a binomial analysis.