Submitted:

28 May 2023

Posted:

30 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Current biosolids management practices and regulatory framework in Australia

3. Limitations with recycling biosolids to land

3.1. Heavy metals and metalloids

3.2. Persistent organic pollutants

3.3. Microplastics

3.4. Pathogens

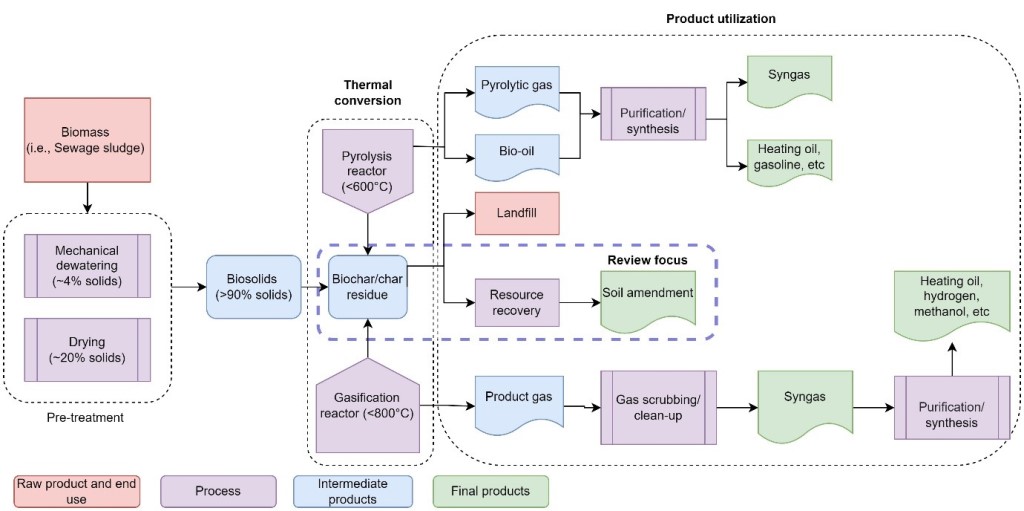

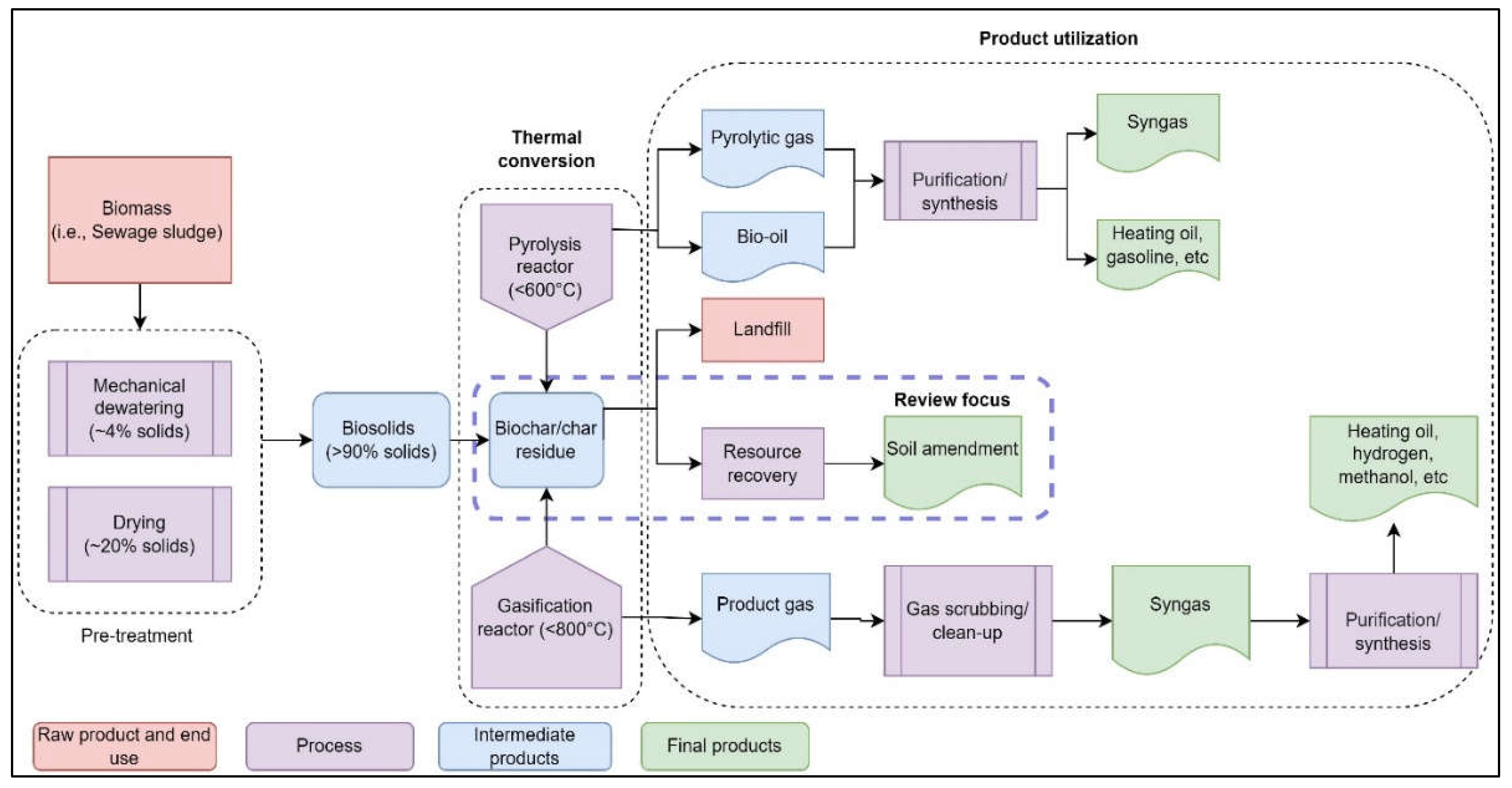

4. Thermal treatment of biosolids

4.1. Pyrolysis

4.2. Gasification

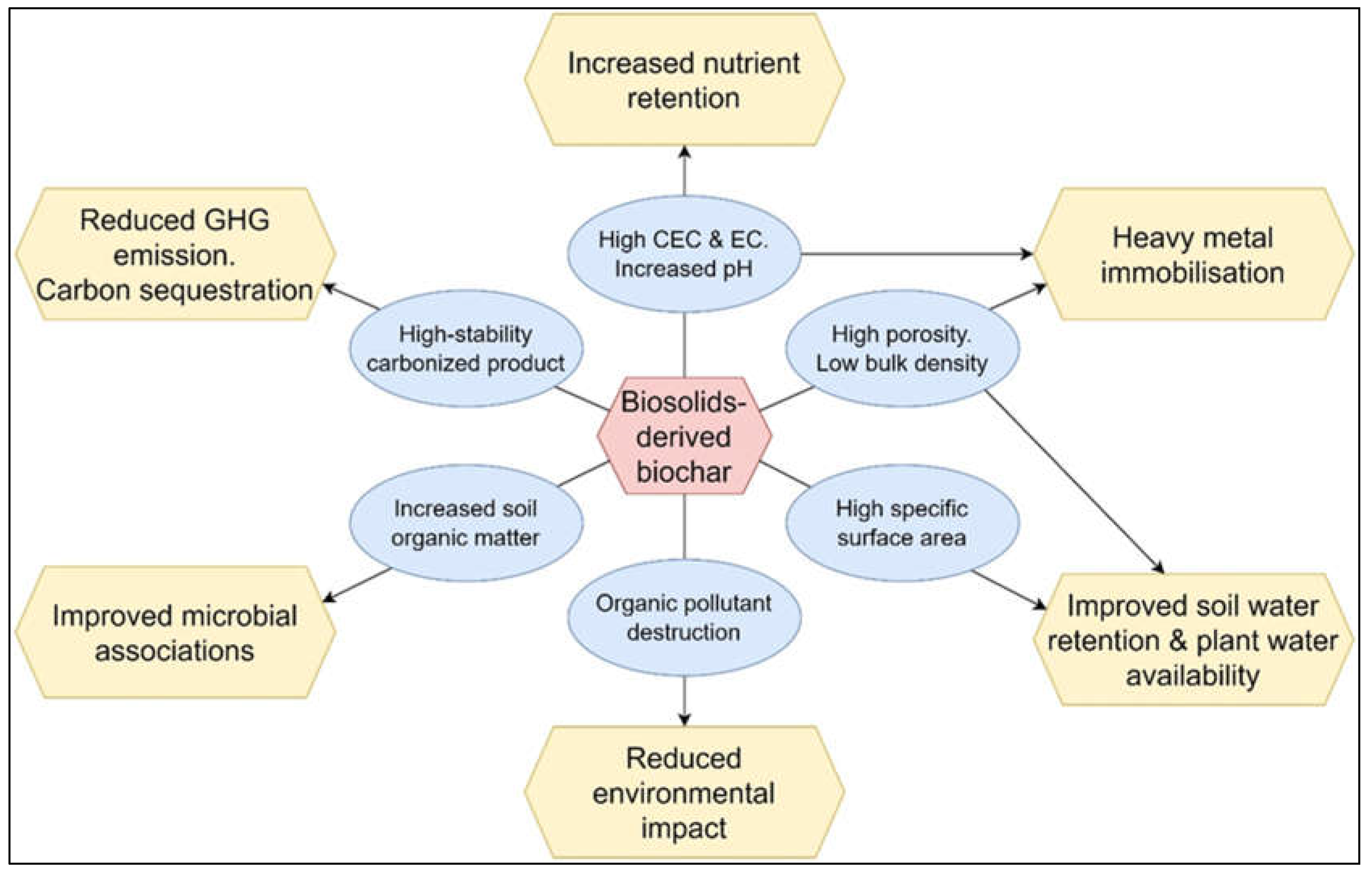

5. Biosolids-derived biochar

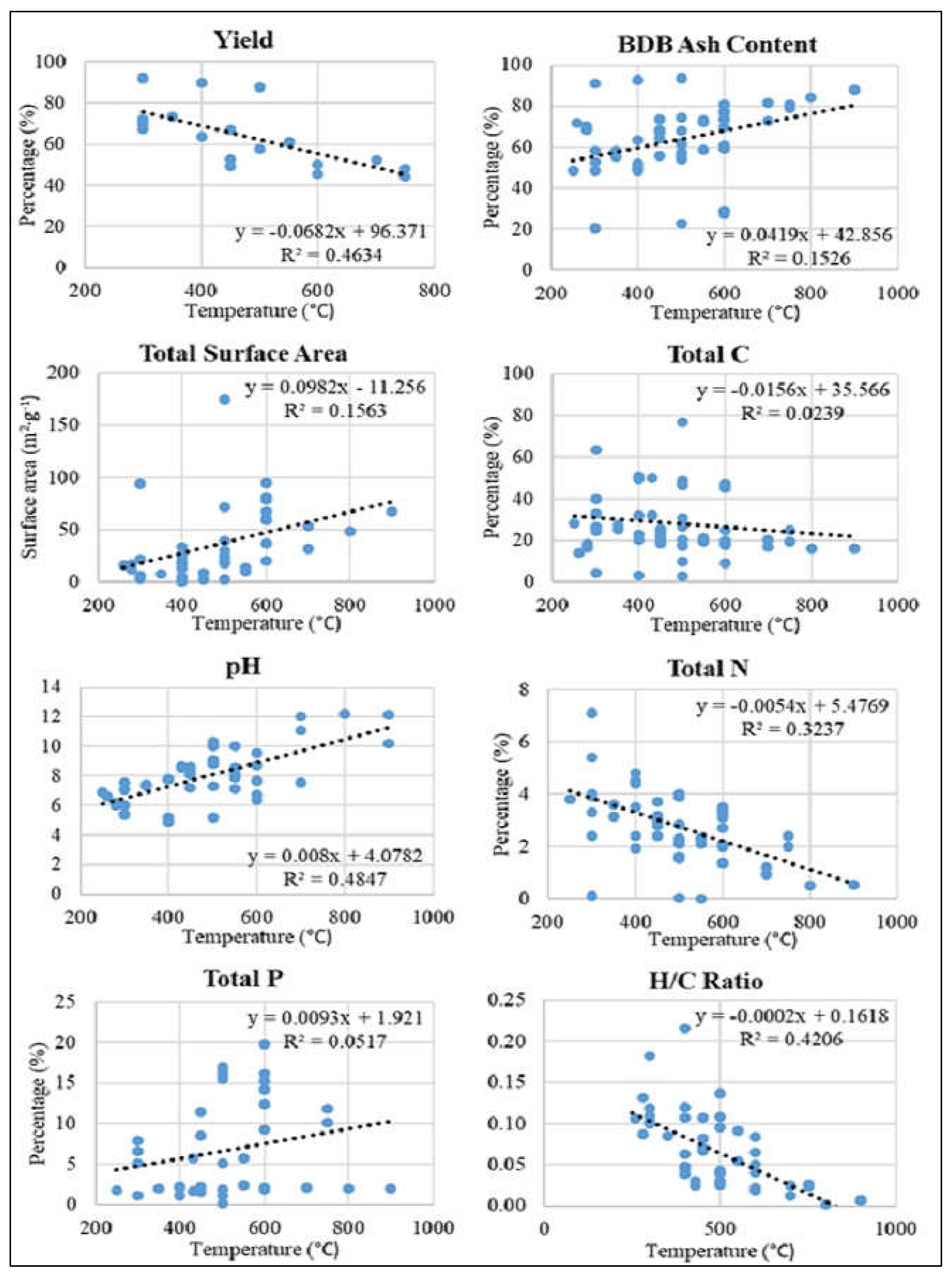

5.1. Physicochemical characteristics of biosolids-derived biochar

5.1.1. Biochar yield

5.1.2. Surface area & porosity

5.1.3. Electrical Conductivity and pH

5.1.4. H:C molar ratio

5.1.5. Nitrogen, phosphorus, and other nutrients

5.2. Contaminants in biosolid-derived biochar

5.2.1. Fate of Heavy Metals in biosolids-derived biochar

5.2.2. Fate of organic pollutants and microplastics in biosolids-derived biochar

6. Use of biosolids-derived biochar as a soil amendment

6.1. Soil effects

6.1.1. Soil acidity and nutrient leaching

6.1.2. Soil hydrology

6.1.3. Greenhouse gas emissions

6.1.4. Soil nutrients, soil organic matter, and soil carbon

6.2. Crop effects

6.2.1. Crop yield

6.2.2. Bioavailability and bioaccumulation of pollutants

7. Conclusions and future research needs

- Explore the potential for cost-effective thermal technology to treat biosolids, including alternatives for recovering energy for electricity generation and conversion of biosolids to biochar.

- Thermal treatment appears to be effective at eliminating persistent organic pollutants, microplastics, and pathogenic contaminants from biosolids. However, the efficacy of thermal treatment in reducing (or avoiding) soil contamination from these sources is not well documented. This information is critical for supporting the safe use of biosolid-derived biochar as a soil amendment and for removing concerns associated with recycling.

- There is potential to customize biochar products to suit specific users’ needs (e.g., soil and crop type, farm application method), which will require understanding of the relationship between the desired biochar characteristics and the production conditions and feedstock. The optimal combination of feedstock and treatment conditions to match specific crop and soil requirements needs to be determined. Optimizations of the physical and mechanical properties of biosolids-derived biochar will facilitate field application with standard fertilizer applicators, improving field delivery efficiency and logistics, and their acceptability by farmers.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Marchuk, S.; Tait, S.; Sinha, P.; Harris, P.; Antille, D.L.; McCabe, B.K. Biosolids-derived fertilisers: A review of challenges and opportunities. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 875, 162555. [CrossRef]

- Marchuk, S.; Antille, D.L.; Sinha, P.; Tuomi, S.; Harris, P.W.; McCabe, B.K. An investigation into the mobility of heavy metals in soils amended with biosolids-derived biochar. In: 2021 ASABE Annual International Meeting; ASABE Paper No.: 2100103; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers. St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ferreiro, J.; Nieto, A.; Méndez, A.; Askeland, M.P.; Gascó, G. Biochar from biosolids pyrolysis: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, (5). [CrossRef]

- Goldan, E.; Nedeff, V.; Barsan, N.; Culea, M.; Tomozei, C.; Panainte-Lehadus, M.; Mosnegutu, E. Evaluation of the use of sewage sludge biochar as a soil amendment—A review. Sustainability 2022, 14, (9), 5309. [CrossRef]

- Collivignarelli, M.C.; Canato, M.; Abbà, A.; Carnevale Miino, M. Biosolids: What are the different types of reuse? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238, 117844. [CrossRef]

- Australian & New Zealand Biosolids Partnership, 2020. https://www.biosolids.com.au/guidelines/australian-biosolids-statistics/ (30 April 2023).

- Department of Environment and Science. End of Waste Code: Biosolids (ENEW07359617). Queensland Government, Australia. 2020. https://environment.des.qld.gov.au/data/assets/pdf_file/0029/88724/wr-eowc-approved-biosolids.pdf.

- Oladejo, J.; Shi, K.; Luo, X.; Yang, G.; Wu, T. A review of sludge-to-energy recovery methods. Energies 2019, 12, (1). [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, K.; Moustakas, K.; Witek-Krowiak, A. Bio-based fertilizers: A practical approach towards circular economy. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 295, 122223. [CrossRef]

- Racek, J.; Sevcik, J.; Chorazy, T.; Kucerik, J.; Hlavinek, P. Biochar – Recovery material from pyrolysis of sewage sludge: A review. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, (7), 3677-3709. [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Kundu, S.; Halder, P.; Ratnnayake, N.; Marzbali, M.H.; Aktar, S.; Selezneva, E.; Paz-Ferreiro, J.; Surapaneni, A.; de Figueiredo, C.C.; Sharma, A.; Megharaj, M.; Shah, K. A critical literature review on biosolids to biochar: an alternative biosolids management option. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 19, (4), 807-841. [CrossRef]

- Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council. National water quality management strategy: Guidelines for sewerage systems biosolids management. 2004. https://environment.des.qld.gov.au/assets/documents/regulation/wr-eowc-approved-biosolids.pdf.

- McCabe, B.K.; Harris, P.; Antille, D.L.; Schmidt, T.; Lee, S.; Hill, A.; Baillie, C. Toward profitable and sustainable bioresource management in the Australian red meat processing industry: A critical review and illustrative case study. Critical Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 50, (22), 2415-2439. [CrossRef]

- McCabe, B.K.; Antille, D.L.; Marchuk, S.; Tait, S.; Lee, S.; Eberhard, J.; Baillie, C.P. Biosolids-derived organomineral fertilizers from anaerobic digestion digestate: opportunities for Australia. In: 2019 ASABE Annual International Meeting, ASABE Paper No.: 1900192; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers. St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, D.L.; Penney, N.; McLaughlin, M.J.; Rigby, H.; Schwarz, K. Land application of sewage sludge (biosolids) in Australia: risks to the environment and food crops. Water Sci. Technol. 2010, 62, (1), 48-57. [CrossRef]

- Maulini-Duran, C.; Artola, A.; Font, X.; Sánchez, A. A systematic study of the gaseous emissions from biosolids composting: raw sludge versus anaerobically digested sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 147, 43-51. [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.-Y.; Yoon, J.-K.; Kim, T.-S.; Yang, J.E.; Owens, G.; Kim, K.-R. Bioavailability of heavy metals in soils: definitions and practical implementation—a critical review. Environ. Geochem. Health 2015, 37, 1041-1061. [CrossRef]

- Asmoay, A.S.; Salman, S.A.; El-Gohary, A.M.; Sabet, H.S. Evaluation of heavy metal mobility in contaminated soils between Abu Qurqas and Dyer Mawas Area, El Minya Governorate, Upper Egypt. Bull Natl Res Cent 2019, 43, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; He, Z.L.; Stoffella, P.J. Land application of biosolids in the USA: A Review. Appl Environ Soil Sci 2012, 2012, 201462. [CrossRef]

- Torri, S.I.; Corrêa, R.S. Downward movement of potentially toxic elements in biosolids amended soils. Appl Environ Soil Sci 2012, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Antille, D.L.; Godwin, R.J.; Sakrabani, R.; Seneweera, S.; Tyrrel, S.F.; Johnston, A.E. Field-Scale evaluation of biosolids-derived organomineral fertilizers applied to winter wheat in England. Agronomy Journal 2017, 109, (2), 654-674. [CrossRef]

- Wuana, R.A.; Okieimen, F.E. Heavy Metals in Contaminated Soils: A review of sources, chemistry, risks and best available strategies for remediation. ISRN Ecology 2011, 2011, 402647. [CrossRef]

- Silveira, M.L.A.; Alleoni, L.R.F.; Guilherme, L.R.G. Biosolids and heavy metals in soil. Scientia Agricola 2003, 60, (4). [CrossRef]

- Darvodelsky, P.; Hopewell, K. Assessment of emergent contaminants in biosolids. Water e-Journal 2018, 3. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.M.; Higgins, C.P.; Huset, C.A.; Luthy, R.G.; Barofsky, D.F.; Field, J.A. Fluorochemical mass flows in a municipal wastewater treatment facility. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, (23), 7350-7357. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, N.; Rice, C.P.; Ramirez, M.; Torrents, A. Fate of Triclocarban, Triclosan and Methyltriclosan during wastewater and biosolids treatment processes. Water Res. 2013, 47, (13), 4519-4527. [CrossRef]

- Mackay, D.; Fraser, A. Bioaccumulation of persistent organic chemicals: mechanisms and models. Environ. Pollut. 2000, 110, (3), 375-391. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Mansour, M.S.M. A review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Source, environmental impact, effect on human health and remediation. Egypt. J. Pet. 2016, 25, (1), 107-123. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, B.O.; Porter, N.A.; Marriott, P.J.; Blackbeard, J.R. Investigating the levels and trends of organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyl in sewage sludge. Environ. Int. 2010, 36, (4), 323-329. [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.-L.; Huerta Lwanga, E.; Eldridge, S.M.; Johnston, P.; Hu, H.-W.; Geissen, V.; Chen, D. An overview of microplastic and nanoplastic pollution in agroecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 1377-1388. [CrossRef]

- Nizzetto, L.; Futter, M.; Langaas, S. Are agricultural soils dumps for microplastics of urban origin? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, (20), 10777-10779. [CrossRef]

- Piehl, S.; Leibner, A.; Löder, M.G.J.; Dris, R.; Bogner, C.; Laforsch, C. Identification and quantification of macro- and microplastics on an agricultural farmland. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, (1), 17950. [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Luo, Y.; Lu, S.; Liu, M.; Song, Y.; Lei, L. Microplastics in soils: Analytical methods, pollution characteristics and ecological risks. Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2018, 109, 163-172. [CrossRef]

- Okoffo, E.D.; Tscharke, B.J.; O’Brien, J.W.; O’Brien, S.; Ribeiro, F.; Burrows, S.D.; Choi, P.M.; Wang, X.; Mueller, J.F.; Thomas, K.V. Release of Plastics to Australian land from biosolids end-use. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, (23), 15132-15141. [CrossRef]

- Mahon, A.M.; O’Connell, B.; Healy, M.G.; O’Connor, I.; Officer, R.; Nash, R.; Morrison, L. Microplastics in sewage sludge: Effects of treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, (2), 810-818. [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, A.; Karabatak, B. Microplastics and pollutants in biosolids have contaminated agricultural soils: An analytical study and a proposal to cease the use of biosolids in farmlands and utilise them in sustainable bricks. Waste Manage. 2020, 107, 252-265. [CrossRef]

- de Souza Machado, A.A.; Kloas, W.; Zarfl, C.; Hempel, S.; Rillig, M.C. Microplastics as an emerging threat to terrestrial ecosystems. Glob Chang Biol 2018, 24, (4), 1405-1416. [CrossRef]

- Panepinto, D.; Genon, G. Wastewater sewage sludge: the thermal treatment solution. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 2014, 180. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Walia, M.; Gera, R.; Kapoor, K.; Kundu, B. Impact of sewage sludge application on soil microbial biomass, microbial processes and plant growth–A review. Agric. Rev. 2008, 29, (1), 1-10. http://arccarticles.s3.amazonaws.com/webArticle/articles/ar291001.pdf.

- Mossa, A.-W.; Dickinson, M.J.; West, H.M.; Young, S.D.; Crout, N.M. The response of soil microbial diversity and abundance to long-term application of biosolids. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 224, 16-25. [CrossRef]

- Bradford, S.A.; Morales, V.L.; Zhang, W.; Harvey, R.W.; Packman, A.I.; Mohanram, A.; Welty, C. Transport, and fate of microbial pathogens in agricultural settings. Critical Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 43, (8), 775-893. [CrossRef]

- Goberna, M.; Simón, P.; Hernández, M.T.; García, C. Prokaryotic communities and potential pathogens in sewage sludge: Response to wastewaster origin, loading rate and treatment technology. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 360-368. [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, J.P.S.; Toze, S.G. Human pathogens and their indicators in biosolids: A literature review. Environ. Int. 2009, 35, (1), 187-201. [CrossRef]

- Edgerton, B.; Buss, W. A review of the benefits of biochar and proposed trials, biochar literature review and proposed trials: Potential to enhance soils and sequester carbon in the ACT for a circular economy. AECOM, Canberrra. 2019. https://www.environment.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/1394471/a-review-of-the-benefits-of-biochar-and-proposed-trials.pdf.

- Gao, N.; Kamran, K.; Quan, C.; Williams, P.T. Thermochemical conversion of sewage sludge: A critical review. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2020, 79, 100843. [CrossRef]

- Raheem, A.; Sikarwar, V.S.; He, J.; Dastyar, W.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Wang, W.; Zhao, M. Opportunities and challenges in sustainable treatment and resource reuse of sewage sludge: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 337, 616-641. [CrossRef]

- Ni, B.-J.; Zhu, Z.-R.; Li, W.-H.; Yan, X.; Wei, W.; Xu, Q.; Xia, Z.; Dai, X.; Sun, J. Microplastics mitigation in sewage sludge through pyrolysis: The role of pyrolysis temperature. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 7, (12), 961-967. [CrossRef]

- Magdziarz, A.; Werle, S. Analysis of the combustion and pyrolysis of dried sewage sludge by TGA and MS. Waste Manage. 2014, 34, (1), 174-179. [CrossRef]

- Udayanga, C.W.D.; Veksha, A.; Giannis, A.; Lisak, G.; Chang, V.W.C.; Lim, T.-T. Fate and distribution of heavy metals during thermal processing of sewage sludge. Fuel 2018, 226, 721-744. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, M.; Sahu, J.N.; Ganesan, P. Effect of process parameters on production of biochar from biomass waste through pyrolysis: A review. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 467-481. [CrossRef]

- Rada, E.C., Thermochemical waste treatment: combustion, gasification, and other methodologies. 1st edition ed.; Apple Academic Press: 2017.

- Srinivasan, P.; Sarmah, A.K.; Smernik, R.; Das, O.; Farid, M.; Gao, W. A feasibility study of agricultural and sewage biomass as biochar, bioenergy and biocomposite feedstock: Production, characterization and potential applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 512-513, 495-505. [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.; Coello, M.D.; Quiroga, J.M.; Aragón, C.A. Overview of sewage sludge minimisation: techniques based on cell lysis-cryptic growth. Desalination Water Treat. 2013, 51, (31-33), 5918-5933. [CrossRef]

- Salman, C.A.; Schwede, S.; Thorin, E.; Li, H.; Yan, J. Identification of thermochemical pathways for the energy and nutrient recovery from digested sludge in wastewater treatment plants. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 1317-1322. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.K.; Strezov, V.; Chan, K.Y.; Ziolkowski, A.; Nelson, P.F. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on production and nutrient properties of wastewater sludge biochar. J. Environ. Manage. 2011, 92, (1), 223-228. [CrossRef]

- Mukome, F.N.D.; Parikh, S.J. UC Davis Biochar Databse. http://ucdavis.biochar.edu.

- Lehmann, J.; Gaunt, J.; Rondon, M. Bio-char sequestration in terrestrial ecosystems – A review. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2006, 11, (2), 403-427. [CrossRef]

- Steiner, C.; Glaser, B.; Geraldes Teixeira, W.; Lehmann, J.; Blum, W.E.H.; Zech, W. Nitrogen retention and plant uptake on a highly weathered central Amazonian Ferrosol amended with compost and charcoal. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2008, 171, (6), 893-899. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Gascó, G.; Méndez, A.; Surapaneni, A.; Jegatheesan, V.; Shah, K.; Paz-Ferreiro, J. Influence of pyrolysis parameters on phosphorus fractions of biosolids derived biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 695, 133846. [CrossRef]

- Song, X.D.; Xue, X.Y.; Chen, D.Z.; He, P.J.; Dai, X.H. Application of biochar from sewage sludge to plant cultivation: Influence of pyrolysis temperature and biochar-to-soil ratio on yield and heavy metal accumulation. Chemosphere 2014, 109, 213-220. [CrossRef]

- Van Wesenbeeck, S.; Prins, W.; Ronsse, F.; Antal, M.J. Sewage sludge carbonization for biochar applications: Fate of heavy metals. Energy & Fuels 2014, 28, (8), 5318-5326. [CrossRef]

- Callegari, A.; Capodaglio, A.G. Properties and beneficial uses of (bio)chars, with special attention to products from sewage sludge pyrolysis. Resources 2018, 7, (1). [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.; Heuer, S.; Quicker, P.; Li, T.; Løvås, T.; Scherer, V. An alternative approach for the estimation of biochar yields. Energy & Fuels 2018, 32. [CrossRef]

- Leng, L.; Xiong, Q.; Yang, L.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, S.; Li, H.; Huang, H. An overview on engineering the surface area and porosity of biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 763, 144204. [CrossRef]

- Kookana, R.S.; Sarmah, A.K.; Van Zwieten, L.; Krull, E.; Singh, B. Chapter three - Biochar application to soil: Agronomic and environmental benefits and unintended consequences. Adv. Agron. 2011, 112, 103-143. [CrossRef]

- Agrafioti, E.; Bouras, G.; Kalderis, D.; Diamadopoulos, E. Biochar production by sewage sludge pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2013, 101, 72-78. [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, A.; Sokołowska, Z.; Boguta, P. Biochar physicochemical properties: pyrolysis temperature and feedstock kind effects. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 19, (1), 191-215. [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, B.; Siatecka, A.; Jędruchniewicz, K.; Sochacka, A.; Bogusz, A.; Oleszczuk, P. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) persistence, bioavailability and toxicity in sewage sludge- or sewage sludge-derived biochar-amended soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 747, 141123. [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, K.; Ramteke, D.S.; Paliwal, L.J. Production of activated carbon from sludge of food processing industry under controlled pyrolysis and its application for methylene blue removal. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2012, 95, 79-86. [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Yang, X.; Spinosa, L. Development of sludge-based adsorbents: Preparation, characterization, utilization and its feasibility assessment. J. Environ. Manage. 2015, 151, 221-232. [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, C.C.; Pinheiro, T.D.; de Oliveira, L.E.Z.; de Araujo, A.S.; Coser, T.R.; Paz-Ferreiro, J. Direct and residual effect of biochar derived from biosolids on soil phosphorus pools: A four-year field assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 140013. [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, C.C.; Chagas, J.K.M.; da Silva, J.; Paz-Ferreiro, J. Short-term effects of a sewage sludge biochar amendment on total and available heavy metal content of a tropical soil. Geoderma 2019, 344, 31-39. [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, C.C.; Farias, W.M.; Coser, T.R.; de Paula, A.M.; Da Silva, M.R.S.; Paz-Ferreiro, J. Sewage sludge biochar alters root colonization of mycorrhizal fungi in a soil cultivated with corn. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2019, 93, 103092. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Lu, T.; Huang, H.; Zhao, D.; Kobayashi, N.; Chen, Y. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on physical and chemical properties of biochar made from sewage sludge. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2015, 112, 284-289. [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, S.F.; Dinelli, F.D.; Kenar, J.A.; Jackson, M.A.; Thomas, A.J.; Peterson, S.C. Physical and chemical properties of pyrolyzed biosolids for utilization in sand-based turfgrass rootzones. Waste Manage. 2018, 76, 98-105. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Meehan, B.; Shah, K.; Surapaneni, A.; Hughes, J.; Fouché, L.; Paz-Ferreiro, J. Physicochemical properties of biochars produced from biosolids in Victoria, Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, (7). [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.A.; Cole, A.J.; Whelan, A.; de Nys, R.; Paul, N.A. Slow pyrolysis enhances the recovery and reuse of phosphorus and reduces metal leaching from biosolids. Waste Manage. 2017, 64, 133-139. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Zhuang, L.; Yang, Y.; Qiu, R. Characterization of sewage sludge-derived biochars from different feedstocks and pyrolysis temperatures. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2013, 102, 137-143. [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, A.; Oleszczuk, P. The conversion of sewage sludge into biochar reduces polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon content and ecotoxicity but increases trace metal content. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 75, 235-244. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Lu, W.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, L. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on characteristics and heavy metal adsorptive performance of biochar derived from municipal sewage sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 164, 47-54. [CrossRef]

- Barry, D.; Barbiero, C.; Briens, C.; Berruti, F. Pyrolysis as an economical and ecological treatment option for municipal sewage sludge. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 122, 472-480. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, S.; Zhou, N.; Fan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, P.; Anderson, E.; Ding, K.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, P.; Ruan, R. Development and application of a continuous fast microwave pyrolysis system for sewage sludge utilization. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 256, 295-301. [CrossRef]

- Piskorz, J.; Scott, D.S.; Westerberg, I.B. Flash pyrolysis of sewage sludge. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Process Design and Development 1986, 25, (1), 265-270. [CrossRef]

- Uchimiya, M.; Hiradate, S.; Antal, M.J. Dissolved phosphorus speciation of flash carbonization, slow pyrolysis, and fast pyrolysis biochars. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, (7), 1642-1649. [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, T.P.; Sárossy, Z.; Ahrenfeldt, J.; Henriksen, U.B.; Frandsen, F.J.; Müller-Stöver, D.S. Changes imposed by pyrolysis, thermal gasification and incineration on composition and phosphorus fertilizer quality of municipal sewage sludge. J. Environ. Manage. 2017, 198, 308-318. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, A.B.; Ferrasse, J.-H.; Chaurand, P.; Saveyn, H.; Borschneck, D.; Roche, N. Mineralogy and leachability of gasified sewage sludge solid residues. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 191, (1), 219-227. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wang, B.; Shi, Z.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Mao, Z.; Liao, L.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y. Immobilization of heavy metals (Cd, Zn, and Pb) in different contaminated soils with swine manure biochar. Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 2021, 33, (1), 55-65. [CrossRef]

- Méndez, A.; Terradillos, M.; Gascó, G. Physicochemical and agronomic properties of biochar from sewage sludge pyrolysed at different temperatures. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2013, 102, 124-130. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.D.; Camps-Arbestain, M.; Lin, Y.; Munroe, P.; Chia, C.H.; Hook, J.; van Zwieten, L.; Kimber, S.; Cowie, A.; Singh, B.P.; Lehmann, J.; Foidl, N.; Smernik, R.J.; Amonette, J.E. An investigation into the reactions of biochar in soil. Soil Res. 2010, 48, (7), 501-515. [CrossRef]

- Ok, Y.S.; MUchimiya, S.M.; Change, S.X.; Bolan, N., Biochar: production, characterisation and applications. CRC Press: New York, USA, 2015.

- Sánchez, M.E.; Menéndez, J.A.; Domínguez, A.; Pis, J.J.; Martínez, O.; Calvo, L.F.; Bernad, P.L. Effect of pyrolysis temperature on the composition of the oils obtained from sewage sludge. Biomass Bioenergy 2009, 33, (6), 933-940. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Zhang, X.; Tang, C.; Muhammad, N.; Wu, J.; Brookes, P.C.; Xu, J. Potential role of biochars in decreasing soil acidification - A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 581-582, 601-611. [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M.; Rangott, G.; Krull, E. Difficulties in using soil-based methods to assess plant availability of potentially toxic elements in biochars and their feedstocks. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 250-251, 29-36. [CrossRef]

- Cayuela, M.L.; Jeffery, S.; van Zwieten, L. The molar H:Corg ratio of biochar is a key factor in mitigating N2O emissions from soil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 202, 135-138. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, S.; Cao, Y.; Liang, P.; Zhang, J.; Wong, M.H.; Wang, M.; Shan, S.; Christie, P. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on properties and environmental safety of heavy metals in biochars derived from municipal sewage sludge. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 320, 417-426. [CrossRef]

- Antal, M.J.; Grønli, M. The art, science, and technology of charcoal production. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, (8), 1619-1640. [CrossRef]

- Bagreev, A.; Bandosz, T.J.; Locke, D.C. Pore structure and surface chemistry of adsorbents obtained by pyrolysis of sewage sludge-derived fertilizer. Carbon 2001, 39, (13), 1971-1979. [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, T.P.; Hauggaard-Nielsen, H.; Gøbel, B.; Stoholm, P.; Ahrenfeldt, J.; Henriksen, U.B.; Müller-Stöver, D.S. Low temperature circulating fluidized bed gasification and co-gasification of municipal sewage sludge. Part 2: Evaluation of ash materials as phosphorus fertilizer. Waste Manage. 2017, 66, 145-154. [CrossRef]

- Al-Wabel, M.I.; Al-Omran, A.; El-Naggar, A.H.; Nadeem, M.; Usman, A.R.A. Pyrolysis temperature induced changes in characteristics and chemical composition of biochar produced from conocarpus wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 131, 374-379. [CrossRef]

- Beesley, L.; Moreno-Jiménez, E.; Fellet, G.; Melo, L.; Sizmur, T., Biochar and heavy metals. In 2015; pp 563-594.

- Huang, H.J.; Yuan, X.Z. The migration and transformation behaviors of heavy metals during the hydrothermal treatment of sewage sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 200. [CrossRef]

- Devi, P.; Saroha, A.K. Risk analysis of pyrolyzed biochar made from paper mill effluent treatment plant sludge for bioavailability and eco-toxicity of heavy metals. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 162, 308-315. [CrossRef]

- Sauvé, S.; Hendershot, W.; Allen, H.E. Solid-solution partitioning of metals in contaminated soils: dependence on ph, total metal burden, and organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2000, 34, (7), 1125-1131. [CrossRef]

- Hameed, R.; Cheng, L.; Yang, K.; Fang, J.; Lin, D. Endogenous release of metals with dissolved organic carbon from biochar: Effects of pyrolysis temperature, particle size, and solution chemistry. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 255, 113253. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Yu, G.; Wang, Y. Effect of pyrolysis temperature on characteristics, chemical speciation and risk evaluation of heavy metals in biochar derived from textile dyeing sludge. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 168, 45-52. [CrossRef]

- International biochar initiative. Standardized product definition and product testing guidelines for biochar that is used in soil. 2015.

- Schmidt, H.-P.; Abiven, S.; Kammann, C.; Glaser, B.; Bucheli, T.; Leifeld, J.; Shackley, S. European Biochar Certificate - Guidelines for a sustainable production of biochar. European Biochar Foundation 2013. https://www.european-biochar.org/media/doc/2/version_en_9_5.pdf.

- Li, L.; Xu, Z.R.; Zhang, C.; Bao, J.; Dai, X. Quantitative evaluation of heavy metals in solid residues from sub- and super-critical water gasification of sewage sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 121, 169-175. [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Li, G.; Khan, S.; Shamshad, I.; Reid, B.J.; Qamar, Z.; Chao, C. Application of sewage sludge and sewage sludge biochar to reduce polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) and potentially toxic elements (PTE) accumulation in tomato. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, (16), 12114-12123. [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Song, J.; Xia, W.; Dong, M.; Chen, M.; Soudek, P. Characterization of contaminants and evaluation of the suitability for land application of maize and sludge biochars. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, (14), 8707-8717. [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Khan, S.; Qing, H.; Reid, B.J.; Chao, C. The effects of sewage sludge and sewage sludge biochar on PAHs and potentially toxic element bioaccumulation in Cucumis sativa L. Chemosphere 2014, 105, 53-61. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Chao, C.; Waqas, M.; Arp, H.P.H.; Zhu, Y.-G. Sewage sludge biochar influence upon rice (Oryza sativa L) yield, metal bioaccumulation and greenhouse gas emissions from acidic paddy soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, (15), 8624-8632. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Wang, N.; Reid, B.J.; Freddo, A.; Cai, C. reduced bioaccumulation of PAHs by Lactuca Satuva L. grown in contaminated soil amended with sewage sludge and sewage sludge derived biochar. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 175, 64-68. [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.J.; Zitomer, D.H.; Miller, T.R.; Weirich, C.A.; McNamara, P.J. Emerging investigators series: pyrolysis removes common microconstituents triclocarban, triclosan, and nonylphenol from biosolids. Environ. Sci. Water Res. 2016, 2, (2), 282-289. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Wen, J.; Jiang, X.; Dai, L.; Jin, Y.; Wang, F.; Chi, Y.; Yan, J. Distribution of PCDD/Fs over the three product phases in wet sewage sludge pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2018, 133, 169-175.

- Undri, A.; Rosi, L.; Frediani, M.; Frediani, P. Efficient disposal of waste polyolefins through microwave assisted pyrolysis. Fuel 2014, 116, 662-671. [CrossRef]

- Buss, W. Pyrolysis solves the issue of organic contaminants in sewage sludge while retaining carbon—making the case for sewage sludge treatment via pyrolysis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, (30), 10048-10053.

- Singh, B.; Macdonald, L.M.; Kookana, R.S.; van Zwieten, L.; Butler, G.; Joseph, S.; Weatherley, A.; Kaudal, B.B.; Regan, A.; Cattle, J.; Dijkstra, F.; Boersma, M.; Kimber, S.; Keith, A.; Esfandbod, M. Opportunities and constraints for biochar technology in Australian agriculture: looking beyond carbon sequestration. Soil Res. 2014, 52, (8), 739-750.

- Ojeda, G.; Mattana, S.; Àvila, A.; Alcañiz, J.M.; Volkmann, M.; Bachmann, J. Are soil–water functions affected by biochar application? Geoderma 2015, 249-250, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Haider, F.U.; Coulter, J.A.; Liqun, C.; Hussain, S.; Cheema, S.A.; Jun, W.; Zhang, R. An overview on biochar production, its implications, and mechanisms of biochar-induced amelioration of soil and plant characteristics. Pedosphere 2022, 32, (1), 107-130. [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S., Biochar for Environmental Management: Science, Technology and Implementation (2nd ed.). Routledge: London, UK, 2015.

- Lu, Y.; Silveira, M.L.; O’Connor, G.A.; Vendramini, J.M.B.; Erickson, J.E.; Li, Y.C.; Cavigelli, M. Biochar impacts on nutrient dynamics in a subtropical grassland soil: 1. Nitrogen and phosphorus leaching. J. Environ. Qual. 2020, 49, (5), 1408-1420. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.Z.; Bahar, M.M.; Sarkar, B.; Donne, S.W.; Wade, P.; Bolan, N. Assessment of the fertilizer potential of biochars produced from slow pyrolysis of biosolid and animal manures. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2021, 155, 105043. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.K.; Strezov, V.; Nelson, P.F. Thermal characterisation of the products of wastewater sludge pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2009, 85, (1), 442-446. [CrossRef]

- Watts, C.W.; Whalley, W.R.; Brookes, P.C.; Devonshire, B.J.; Whitmore, A.P. Biological and physical processes that mediate micro-aggregation of clays. Soil Sci. 2005, 170, (8). [CrossRef]

- Omondi, M.O.; Xia, X.; Nahayo, A.; Liu, X.; Korai, P.K.; Pan, G. Quantification of biochar effects on soil hydrological properties using meta-analysis of literature data. Geoderma 2016, 274, 28-34. [CrossRef]

- Herath, H.M.S.K.; Camps-Arbestain, M.; Hedley, M. Effect of biochar on soil physical properties in two contrasting soils: An Alfisol and an Andisol. Geoderma 2013, 209-210, 188-197. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Lal, R.; Zimmerman, A.R. Effects of biochar and other amendments on the physical properties and greenhouse gas emissions of an artificially degraded soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 487, 26-36. [CrossRef]

- McHenry, M.P. Agricultural bio-char production, renewable energy generation and farm carbon sequestration in Western Australia: Certainty, uncertainty, and risk. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2009, 129, (1), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.K.; Rees, R.M.; Skiba, U.M.; Ball, B.C. Influence of organic and mineral N fertiliser on N2O fluxes from a temperate grassland. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007, 121, (1), 74-83. [CrossRef]

- van Zwieten, L.; Kimber, S.; Morris, S.; Downie, A.; Berger, E.; Rust, J.; Scheer, C. Influence of biochars on flux of N2O and CO2 from Ferrosol. Soil Res. 2010, 48, (7), 555-568. [CrossRef]

- Grutzmacher, P.; Puga, A.P.; Bibar, M.P.S.; Coscione, A.R.; Packer, A.P.; de Andrade, C.A. Carbon stability and mitigation of fertilizer induced N2O emissions in soil amended with biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 625, 1459-1466. [CrossRef]

- Melas, G.B.; Ortiz, O.; AlacaÑIz, J.M. Can biochar protect labile organic matter against mineralization in soil? Pedosphere 2017, 27, (5), 822-831. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.K.; Varma, A., Role of enzymes in maintaining soil health. In Soil Enzymology, Shukla, G.; Varma, A., Eds. Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp 25-42.

- Beesley, L.; Moreno-Jiménez, E.; Gomez-Eyles, J.L.; Harris, E.; Robinson, B.; Sizmur, T. A review of biochars’ potential role in the remediation, revegetation and restoration of contaminated soils. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, (12), 3269-3282. [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ferreiro, J.; Fu, S.; Méndez, A.; Gascó, G. Interactive effects of biochar and the earthworm Pontoscolex corethrurus on plant productivity and soil enzyme activities. J. Soils Sediments. 2014, 14, (3), 483-494. [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ferreiro, J.; Gascó, G.; Gutiérrez, B.; Méndez, A. Soil biochemical activities and the geometric mean of enzyme activities after application of sewage sludge and sewage sludge biochar to soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2012, 48, (5), 511-517. [CrossRef]

- Bolan, N.; Hoang, S.A.; Beiyuan, J.; Gupta, S.; Hou, D.; Karakoti, A.; Joseph, S.; Jung, S.; Kim, K.-H.; Kirkham, M.B.; Kua, H.W.; Kumar, M.; Kwon, E.E.; Ok, Y.S.; Perera, V.; Rinklebe, J.; Shaheen, S.M.; Sarkar, B.; Sarmah, A.K.; Singh, B.P.; Singh, G.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Vikrant, K.; Vithanage, M.; Vinu, A.; Wang, H.; Wijesekara, H.; Yan, Y.; Younis, S.A.; Van Zwieten, L. Multifunctional applications of biochar beyond carbon storage. Int. Mater. Rev. 2021, 1-51. [CrossRef]

- Bridle, T.R.; Pritchard, D. Energy and nutrient recovery from sewage sludge via pyrolysis. Water Sci. Technol. 2004, 50, (9), 169-175. [CrossRef]

- Chagas, J.K.M.; Figueiredo, C.C.d.; Silva, J.d.; Shah, K.; Paz-Ferreiro, J. Long-term effects of sewage sludge–derived biochar on the accumulation and availability of trace elements in a tropical soil. J. Environ. Qual. 2021, 50, (1), 264-277. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.A.T.C.; Figueiredo, C.C. Sewage sludge biochar: effects on soil fertility and growth of radish. Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2016, 32, (2), 127-138. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.K.; Strezov, V.; Yin Chan, K.; Nelson, P.F. Agronomic properties of wastewater sludge biochar and bioavailability of metals in production of cherry tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum). Chemosphere 2010, 78, (9), 1167-1171. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, C.C.d.; Pinheiro, T.D.; de Oliveira, L.E.Z.; de Araujo, A.S.; Coser, T.R.; Paz-Ferreiro, J. Direct and residual effect of biochar derived from biosolids on soil phosphorus pools: A four-year field assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 140013. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.K.; Strezov, V.; McCormick, L.; Nelson, P.F. Wastewater sludge and sludge biochar addition to soils for biomass production from Hyparrhenia hirta. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 82, 345-348. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.K.; Strezov, V.; Nelson, P.F. Comparative assessment of the effect of wastewater sludge biochar on growth, yield and metal bioaccumulation of cherry tomato. Pedosphere 2015, 25, (5), 680-685. [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Cui, L.; Lin, Q.; Li, G.; Zhao, X. Efficiency of sewage sludge biochar in improving urban soil properties and promoting grass growth. Chemosphere 2017, 173, 551-556. [CrossRef]

- Méndez, A.M.; Barriga, S.; Guerrero, F.; Gascó Guerrero, G. The effect of paper mill waste and sewage sludge amendments on acid soil properties. Soil Sci. 2012, 177, (7).

- Lu, T.; Yuan, H.; Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; Chen, Y. Characteristic of heavy metals in biochar derived from sewage sludge. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manage. 2016, 18, (4), 725-733. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Reid, B.J.; Li, G.; Zhu, Y.-G. Application of biochar to soil reduces cancer risk via rice consumption: A case study in Miaoqian village, Longyan, China. Environ. Int. 2014, 68, 154-161. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Waqas, M.; Ding, F.; Shamshad, I.; Arp, H.P.H.; Li, G. The influence of various biochars on the bioaccessibility and bioaccumulation of PAHs and potentially toxic elements to turnips (Brassica rapa L.). J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 300, 243-253. [CrossRef]

| Technology | Samplea, Temp°C | pH | Elemental Analysis (%) | Nutrient Composition (g·kg-1) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | H | N | Ca | Fe | K | Mg | P | S | |||

| Pyrolysis1 | BS 25 | 5.1 | 25.6 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 26.5 (19.4) | 37.0 (22) | 4.1 (3.3) | 8.1 (9.9) | 28.5 (6.8) | 23.2 (24.8) |

| BDB 300 | 5.9 (0.6) | 23.1 (2.7) | 2.7 (0.8) | 3.0 (0.6) | 31.24 (24) | 44.01 (30.4) | 4.17 (3.2) | 10.18 (12.8) | 32.89 (8.2) | 23.23 (1.9) | |

| BDB 400 | 6 (1.3) | 19.9 (0.4) | 1 | 2.2 (0.3) | 42.13 (19.7) | 48.94 (35.5) | 6.52 (3.5) | 13.31 (13.4) | 32.83 (8.7) | 28.46 (26.5) | |

| BDB 500 | 7.1 (0.5) | 15.3 (5.1) | 0.9 (0.8) | 1.0 (0.8) | 40.41 (32.6) | 54.72 (41.6) | 5.12 (4.5) | 13.19 (17.4) | 41.83 (14.9) | 24.43 (29.94) | |

| BDB 550 | 7 | 18.6 (12.5) | 0.8 (0.2) | 2.5 (0.5) | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| BDB 600 | 8.7 (0.7) | - | - | - | 24 | 41.7 | 13.3 | 7.86 | 45.1 | - | |

| BDB 700 | 9.6 (2.0) | 13.9 (5.6) |

- | 1.0 (0.3) | 48.96 (21.7) | 60.66 (43.3) | 12.35 (6.0) | 13.99 (12.7) | 40.92 (7.8) | 35.1 (37.7) | |

| BDB 900 | 11 | 5 | - | 0 | 71.82 | 33.37 | 9.83 | 29.06 | 40.65 | 9.69 | |

| Slow pyrolysis2 |

BS 25 | 7.1 | 25.6 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 42.4 (23.6) | 30.4 (28.0) | 5.1 (2.6) | 9.3 (5.9) | 38.7 (9.2) | 20.9 (10.7) |

| BDB 300 | 7.3 (0.2) | 27.5 (4.7) | 3.1 (0.3) | 4.5. (0.9) | 25.76 (28.7) | 7.10 (2.9) | 3.5 (2.6) | 12.40 (7.4) | 49.69 (21.6) | 7.92 (3.0) | |

| BDB 400 | 7.3 (0.2) | 22.2 (5.6) | 1.9 (0.2) | 3.6 (0.8) | 7.43 (5) | - | 2.17 (0.2) | 9.10 (4) | 42.03 (15.1) | 6.07 (0.6) | |

| BDB 450 | - | 22.5 (4.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | 3.4 (0.5) | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| BDB 500 | 7.4 (0.3) | 22.2 (4.0) | 1.2 (0.6) | 2.8 (1.1) | 56.47 (48.5) | 63.8 (47.5) | 7.59 (5.2) | 13.56 (9) | 56.73 (19.8) | 19.73 (16.9) | |

| BDB 600 | 9.6 (1.6) | 22.2 (3.9) | 0.9 (0.3) | 2.6 (0.9) | 58.96 (42.5) | 48.8 (50.5) | 8.32 (4.9) | 17.85 (13.5) | 68.93 (2.9) | 15.6 (13.9) | |

| BDB 700 | 12.5 (0.4) | 22.5 (3.6) | 0.5 (0.1) | 2.3 (0.4) | 93.05 (24.5) | 51.93 (53.4) | 11.98 (2.9) | 20.42 (9.4) | 83.63 (24.7) | 24.08 (20) | |

| Fast pyrolsis3 |

BS | 43.40 | 6.99 | 5.66 | 27.1 | 8.5 | 5.9 | 6.0 | 23.9 | 10.1 | |

| BDB 400 | - |

29.9 | 1.1 (0.6) |

2.5 (1.4) |

- | - | - | - | - | - | |

| BDB 500 | 8.8 | 19.7 (3.14) |

1.1 (0.6) | 2.5 (1.4) | 73.2 (19.8) | 28.8 (3.2) | 13.2 (6.7) | 17.2 (3.6) | 46.6 (40.2) | - | |

| BDB 600 | 9.5 | 19.5 (1.6) |

0.6 (0.6) | 2.3 (1.3) | 62.71 | 33.60 | 8.40 | 15.45 | 18.76 | - | |

| BDB 700 | 11.1 | 16.9 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 64.37 | 35.32 | 9.30 | 16.36 | 20.35 | - | |

| BDB 800 | 12.2 | 16.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 65.83 | 35.76 | 9.20 | 16.57 | 19.35 | - | |

| BDB 900 | 12.2 | 15.9 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 69.56 | 37.20 | 8.60 | 17.52 | 20.23 | - | |

| Flash Pyrolysis4 |

BDB 350 | 7.7 | 20.5 | 2.4 | 8.2 | 17.07 | 0.4 | 13.52 | 9.88 | 24.12 | - |

| BDB 400 | - | 15.4 | 1.6 | 6.6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| BDB 450 | - | 12 | 1.2 | 5.9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| BDB 500 | - | 12.6 | 1.2 | 3.9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| BDB 550 | - | 10.9 | 0.9 | 4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| BDB 650 | - | 10.3 | 0.7 | 0.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| BDB 700 | 8.7 | 10 | 0.5 | ND | 5.35 | ND | 23.20 | 13.6 | 22.89 | - | |

| BS | - | - | - | - | 51 | 30 | 5 | 6 | 40 | 8 | |

| Two stage gasification5 | BDB 850 | - | 5.8 | - | 0.1 | 14 | 7.5 | 15 | 17.0 | 11.2 | 20 |

| LT-CFB5, b gasification5 | BDB 750 | - | 7.2 | - | 0.6 | 13 | 8.1 | 15 | 17.0 | 11 | 10 |

| Gasification6 | BS | - | - | - | - | 49.7 | 38.7 | 3 | 9.6 | 41.8 | 9.5 |

| BDB 700 | 12 | 22.3 | 0.77 | 1.9 | 11 | 8.8 | 7.6 | 24.5 | 10.2 | - | |

| BDB 900 | 12 | 2.9 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 14.5 | 11.9 | 10.9 | 35.1 | 14.2 | - | |

| Guidelines | Sample | Temp °C |

Total heavy metals (mg·kg-1 DBS.)b | Total PAHs μg·kg-1 d.b. |

Reference | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | Cd | Cr | Cu | Pb | Hg | Ni | Zn | |||||

| AWA-Biosolid | - | - | 20-30 | 1-20 | 100-600 | 100-2000 | 150-420 | 1-15 | 60-270 | 200-2500 | - | Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council, 2004 [12] |

| IBI -Biochar | Category A Category B |

- | 13 100 |

1.4 20 |

93 100 |

143 6,000 |

121 300 |

1 10 |

47 400 |

416 7400 |

6000 300000 |

International biochar initiative, 2015 [106] |

| EBC-Biochar | Premium Basic |

- | 13 13 |

1 1.5 |

80 90 |

100 100 |

120 150 |

1 1 |

30 50 |

400 400 |

4000 12000 |

Schmidt et al. (2013) [107] |

| Technology | ||||||||||||

| Pyrolysis | BS | N/A | - | 2.3-5.3 | - | 401-611 | 136-224 | - | - | 629-1238 | - | Lu et al. (2013) [19] |

| BDB | 300 | - | 3.3-7.5 | - | 480-043 | 190-350 | - | - | 849-1909 | |||

| BDB | 400 | - | 3.8-9.8 | - | 549-1198 | 194-438 | - | - | 912-2104 | |||

| BDB | 500 | - | 4.3-8.9 | - | 565-1267 | 212-506 | - | - | 1014-2305 | |||

| Pyrolysis | BS | N/A | - | 7.54 | - | 545 | 189 | - | 102 | 2398 | Méndez et al. (2013) [88] | |

| BDB | 400 | - | 9.67 | - | 632 | 239 | - | 129 | 2983 | - | ||

| BDB | 600 | - | 9.76 | - | 740 | 253 | - | 134 | 3922 | |||

| Gasification | BS BDB |

N/A 750 |

- - |

1.0-2.5 1.5-5.5 |

34-66 80-182 |

- - |

41 84-110 |

1.5 0.2 |

24 87-158 |

- - |

- | Thomsen et al. (2017b) [85] |

| Gasification | BS BDB BDB |

- 350 400 |

- | 0.93 1.5-1.6 1.5-1.7 |

80.8 218-227 228-247 |

580 851-900 886-922 |

78.27 114-121 120-125 |

402 597-623 612-637 |

- | Li et al. (2012) [108] | ||

| Gasification | BS BDB BDB |

- 700 900 |

- | 1 ND ND |

36 (7) 98 (1) 104 (2) |

529 (8) 1159 (8) 1346 (6) |

45 88(1) 51(1) |

2 ND ND |

66(2) 122(1) 165(4) |

423(10) 753 (5) 757 (4) |

- | Hernandez et al. (2011) [86] |

| Pyrolysis | BDB | 200 | 7.6-16.7 | 2-9.1 | 67.6-281 | 712-1000 | 28.4-60 | 65-635 | 1964-2940 | Waqas et al. (2015) [109] | ||

| Pyrolysis | BDS BDB BDB BDB BDB |

25 200 500 600 700 |

- | 1.0 1.1 1.4 1.1 0.7 |

173 180 233 239 247 |

143 149 193 198 202 |

51.1 54.7 67.9 69.1 74.2 |

42 41.1 55.1 56.1 55.2 |

698 735 887 976 986 |

3339 1644 70385 1241 179 |

Luo et al. (2014) [110] |

|

| Pyrolysis | BS BDB BDB |

25 300 500 |

- | 3.6 5.5 6.5 |

- | 487 733 841 |

167 260 506 |

- | - | 922 1417 1705 |

- | Lu et al. (2013) [78] |

| Pyrolysis | BS BDB |

- 550 |

2.6 12 |

1.7 2.7 |

- | 160 210 |

44 82 |

- | - | 1200 2080 |

3860 900 |

Waqas et al. (2014) [111] |

| Pyrolysis | BS BDB |

550 |

2.3 11.9 |

1.5 2.3 |

- | 171 237 |

53.8 71.9 |

- | - | 1105 1879 |

5780 1701 |

Waqas et al. (2015) [109] |

| Pyrolysis | BS BDB BDB |

Air 400 500 |

18 9.4 14 |

ND 3.2 3.2 |

20 60.7 61 |

165 357 334 |

42 83 92.6 |

23 77.1 68.4 |

703 1478 1704 |

- | Song et al. (2014) [60] | |

| Pyrolysis | BDB | 550 | 9.3 | 3.7 | 74.1 | 222 | 27 | 34.5 | 1102 | - | Khan et al. (2013a) [112] | |

| Pyrolysis | BS BDB |

- 500 |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2950 4350 |

Khan et al. (2013b) [113] |

| Pyrolysis | BS BDB |

- 500 |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8625-13333 612-766 |

Tomczyk et al. (2020b) [68] |

| Technology | Samplea |

Temp °C |

Available heavy metals (mg·kg-1 DBSb) | Reference | ||||||||

| As | Cd | Cr | Cu | Pb | Hg | Ni | Zn | |||||

| Pyrolysis | BS BDB BDB BDB BDB |

25 300 500 600 700 |

- | 7.80 0.45 2.30 5.90 10.5 |

9 11 9 8.5 8 |

700 45.5 205 295 365 |

309 48 27.5 67 115 |

- | 135 20.5 25 37 46.5 |

3565 280 385 635 970 |

Luo et al. (2014) [110] | |

| Pyrolysis | BS BDB BDB |

25 300 500 |

- | 1.8 ND ND |

- | 139 1.7 0.4 |

34.9 ND 6.5 |

- | - | 586.6 4.5 50.8 |

Lu et al. (2013) [78] | |

| Pyrolysis | BS BDB |

- 550 |

1.1 0.04 |

1.1 0.2 |

- | 37 3.4 |

8.2 2.5 |

- | - | 371 66 |

Waqas et al. (2014) [111] | |

| Pyrolysis | BS BDB |

- 550 |

1.07 0.05 |

1.03 0.17 |

- | 35.3 4.35 |

9.02 3.41 |

- | - | 387 56.7 |

Waqas et al. (2015) [109] | |

| Pyrolysis | SS BDB BDB |

Air 400 500 |

- 0.9 0.6 |

- ND ND |

- 0.2 ND |

- 0.3 0.2 |

- 0.5 0.6 |

- | - 0.3 ND |

- 7.9 1.8 |

Song et al. (2014) [60] | |

| Pyrolysis | BDB | 550 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 1.24 | 6.5 | 2.13 | 2.26 | 127 | Khan et al. (2013b) [113] | ||

| Gasification | BS BDB BDB |

- 350 400 |

- | 0.62 0.03-0.12 0.01-0.24 |

1.26 1-3.91 1.2-7.51 |

22.63 0.42-1.17 0.37-0.97 |

2.74 0.58-1.13 0.59-1.40 |

- | - | 112 7.67-17.19 9.05-12.25 |

Li et al. (2012) [108] | |

| Gasification | BS BDB BDB |

- 700 900 |

- | - | 8.89 0.06 0.04 |

16.3 0.49 2.08 |

- | - | 3.44 0.04 <0.01 |

- | Hernandez et al. (2011) [86] | |

| Temp °C |

Plant species | Soil fertility | Agronomic performance | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crop yield | Heavy metals bioaccumulation | ||||

| 300 | Radish | Increased soil base saturation, CEC, available P, Ca, and Mg, except K. Soil pH was not affected. | Increased plant height, yields, and above-ground dry weight. | - | Sousa & Figueiredo (2016) [141] |

| 450 | Wheat | Increased soil CEC, K, and available P. | Increased plant height, biomass, and grain yield. | - | Rehman et al. (2018) [46] |

| 500 | Rice | Increased pH, EC, total N, C and available P and K. Availability of heavy metals in the soil was reduced. | Increased shoot biomass, grain yields, and above-ground dry weight. | Reduced bioaccumulation of As, Co, Cr, Cu, Ni and Pb in rice grains, stems, and leaves. | Khan et al. (2013a) [112] |

| 400-550 | Garlic | - | Increased average plant height, plant biomass (stem and leaves) and garlic yield when compared with control. | No heavy metal accumulation was found in stem and leaves. Although, higher Zn and Cu content was found in roots and bulbs compared to the control. |

Song et al. (2014) [60] |

| 550 | Coolatai grass | - | Increased grass yield was observed, specifically when biosolids-derived biochar was combined with chemical fertilizer. | - | Hossain et al. (2015a) [144] |

| 550 | Cherry tomatoes | - | Increased plant height and fruit yield. | Heavy metals concentrations in the fruits were lower in the biochar treatment than the biosolids treatment. | Hossain et al. (2015b) [145] |

| 550 | Cucumber | - | Increased plant biomass and fruit yields | Reduced bioaccumulation of As, Cu, Cd, Zn and Pb in the fruit when compared to the biosolids treatment. | Waqas et al. (2014) [111] |

| 200-700 | Turf grass | Increased soil organic carbon, total N, available P and K, decreased soil pH. | Increased above-ground dry matter and total N, P and K content. | Reduced bioaccumulation of heavy metals was observed in above-ground biomass |

Yue et al. (2017) [146] |

| Plants | Treatments | As | Cd | Cr | Cu | Ni | Pb | Zn | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice grain | Control 5 % BDB 10% BDB |

0.45 0.19 0.17 |

0.4 0.32 0.28 |

ND ND ND |

20 17 16 |

ND ND ND |

0.95 0.6 0.5 |

54 44 41 |

Khan et al. (2014) [149] |

| Control | 0.35 | 0.26 | ND | 2.8 | ND | 0.5 | 85 | ||

| Tomato | 2% BDB | 0.17 | 2.6 | ND | 4 | ND | 0.25 | 20 | Hossain et al. (2010) [142] |

| 5% BDB | 0.16 | 2.5 | ND | 2 | ND | 0.2 | 12 | ||

| 10% BDB | 0.12 | 2 | ND | 1.2 | ND | 0.17 | 8 | ||

| Rice grain | Control 5% BDB 10% BDB |

0.14 0.05 0.04 |

0.02 0.12 0.13 |

0.3 0.21 0.17 |

4.8 4.7 4.6 |

0.68 0.55 0.49 |

0.35 0.1 0.05 |

8 26 28 |

Khan et al. (2013a) [112] |

| Turnip | 2% BDB | 0.12 | 0.11 | ND | 3.2 | ND | 0.22 | 48 | Khan et al. (2015) [150] |

| 5% BDB | 0.11 | 0.1 | ND | 1.9 | ND | 0.19 | 36 | ||

| Turf grass | Control | 0.14 | 0 | 0.19 | 0.25 | ND | 0.18 | 0.59 | Yue et al. (2017) [146] |

| 1% BDB | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.12 | ND | 0.2 | 0.23 | ||

| 5% BDB | 0.03 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.1 | ND | 0.05 | 0.11 | ||

| 10% BDB | 0.07 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.14 | ND | 0.14 | 0.18 | ||

| 20% BDB | 0.06 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.1 | ND | 0.08 | 0.11 | ||

| 50% BDB | 0.05 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.1 | ND | 0.05 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).