Submitted:

26 May 2023

Posted:

29 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Assay design

2.2. Primers and Probes

2.3. Human ABCB5+ MSCs

2.4. Mouse tissue sampling

2.5. Preparation of reference standards

2.5.1. Calibration standards and quality control standards

2.5.2. Tissue quality control standards

2.5.3. Freeze-thaw stability

2.6. Amplification

2.7. Assay validation and acceptance criteria

2.7.1. Linearity

2.7.2. Accuracy and precision

2.7.3. Specificity

2.7.4. Tissue matrix effects

3. Results

3.1. Linearity and quantification range

3.2. Accuracy and precision

3.2. Specificity

3.3. Freeze-thaw stability of extracted DNA

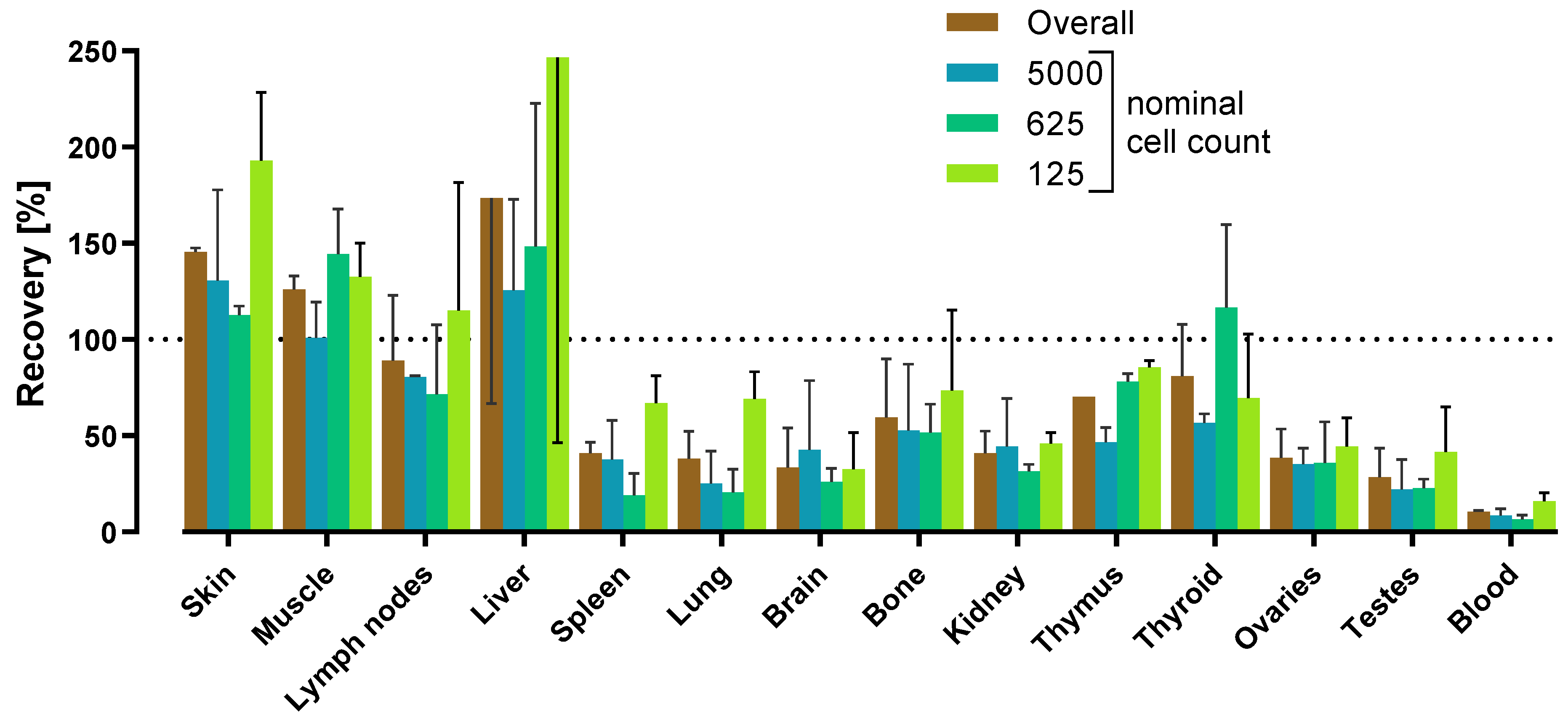

3.4. Tissue matrix effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sanchez-Diaz, M.; Quiñones-Vico, M.I.; Sanabria de la Torre, R.; Montero-Vílchez, T.; Sierra-Sánchez, A.; Molina-Leyva, A.; Arias-Santiago, S. Biodistribution of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells after Administration in Animal Models and Humans: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med 2021, 10, 2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.M.L.; Sampasivam, Y.; Lokanathan, Y. Biodistribution of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in animal models and implied role of exosomes following systemic delivery of MSCs: a systematic review. Am J Transl Res 2022, 14, 2147–2161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salvadori, M.; Cesari, N.; Murgia, A.; Puccini, P.; Riccardi, B.; Dominici, M. Dissecting the Pharmacodynamics and Pharmacokinetics of MSCs to Overcome Limitations in Their Clinical Translation. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2019, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, A.; Futrega, K.; Liang, X.; Hu, X.; Liu, X.; Crawford, D.H.G.; Doran, M.R.; Roberts, M.S.; Wang, H. Concise Review: Quantitative Detection and Modeling the In Vivo Kinetics of Therapeutic Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells. Stem Cells Transl Med 2018, 7, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiyama, Y.; Naritomi, Y.; Moriya, Y.; Yamamoto, S.; Kitahashi, T.; Maekawa, T.; Yahata, M.; Hanada, T.; Uchiyama, A.; Noumaru, A.; et al. Biodistribution studies for cell therapy products: Current status and issues. Regen Ther 2021, 18, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timm, F.; Vollmar, B. Heterogeneity of the intrahepatic portal venous blood flow: impact on hepatocyte transplantation. Microvasc Res 2013, 86, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, M.; Eertman, T.; Sierra Parraga, J.; t Hart, N.; Roemeling-van Rhijn, M.; Eijken, M.; Jespersen, B.; Reinders, M.; Hoogduijn, M.; Ploeg, R.; et al. Infusing Mesenchymal Stromal Cells into Porcine Kidneys during Normothermic Machine Perfusion: Intact MSCs Can Be Traced and Localised to Glomeruli. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohki, A.; Saito, S.; Fukuchi, K. Magnetic resonance imaging of umbilical cord stem cells labeled with superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: effects of labelling and transplantation parameters. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 13684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeder, E.; Henrionnet, C.; Goebel, J.C.; Gambier, N.; Beuf, O.; Grenier, D.; Chen, B.; Vuissoz, P.A.; Gillet, P.; Pinzano, A. Dose-response of superparamagnetic iron oxide labeling on mesenchymal stem cells chondrogenic differentiation: a multi-scale in vitro study. PLoS One 2014, 9, e98451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrzejewska, A.; Jablonska, A.; Seta, M.; Dabrowska, S.; Walczak, P.; Janowski, M.; Lukomska, B. Labeling of human mesenchymal stem cells with different classes of vital stains: robustness and toxicity. Stem Cell Res Ther 2019, 10, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Guidance for Industry – Preclinical Assessment of Investigational Cellular and Gene Therapy Products. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/87564/download (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Bailey, A.M.; Mendicino, M.; Au, P. An FDA perspective on preclinical development of cell-based regenerative medicine products. Nat Biotechnol 2014, 32, 721–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, B.; Coca, M.I.; Codinach, M.; López-Lucas, M.D.; Del Mazo-Barbara, A.; Caminal, M.; Oliver-Vila, I.; Cabañas, V.; Lope-Piedrafita, S.; García-López, J.; et al. Assessment of biodistribution using mesenchymal stromal cells: Algorithm for study design and challenges in detection methodologies. Cytotherapy 2017, 19, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, R.; Sann, J.; Frueh, J.T.; Ullrich, E.; Geiger, H.; Baer, P.C. Tracking of Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells in a Model of Cisplatin-Induced Acute Kidney Injury: Comparison of Bioluminescence Imaging versus qRT-PCR. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.C.; Nadeau, K.; Abbasi, M.; Lachance, C.; Nguyen, M.; Fenrich, J. The Ultimate qPCR Experiment: Producing Publication Quality, Reproducible Data the First Time. Trends Biotechnol 2019, 37, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchiyama, A.; Naritomi, Y.; Hashimoto, Y.; Hanada, T.; Watanabe, K.; Kitta, K.; Suzuki, G.; Komatsuno, T.; Nakamura, T. Understanding quantitative polymerase chain reaction bioanalysis issues before validation planning: Japan Bioanalysis Forum discussion group. Bioanalysis 2022, 14, 1391–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, A.; Durham, J.; Gullick, B.; Rudemiller, N.; Schneider, T. Bioanalytical Assay Strategies and Considerations for Measuring Cellular Kinetics. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 24, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Bell, K.N.; Loker, R.N. qPCR and qRT-PCR analysis: Regulatory points to consider when conducting biodistribution and vector shedding studies. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2021, 20, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurén, A.; Braun, M.; Byrne, P.; Cazzin, C.; Colletti, K.; Cox, C.; Dietz, L.; Emrich, T.; Geddes, K.; Herr, K.; et al. Applying context of use to quantitative polymerase chain reaction method validation and analysis: a recommendation from the European Bioanalysis Forum. Bioanalysis 2021, 13, 1723–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurén, A.; Braun, M.; Cazzin, C.; Colleti, K.; Cox, C.; Dietz, L.; Emrich, T.; Geddes, K.; Herr, K.; Iles, T.; et al. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction in the bioanalytical laboratory and technical and scientific considerations for nonclinical and clinical assay characterization, validation and sample analysis. Bioanalysis 2022, 14, 1085–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissel, M.; Poirier, M.; Satterwhite, C.; Lin, J.; Islam, R.; Zimmer, J.; Khadang, A.; Zemo, J.; Lester, T.; Fjording, M.; et al. Recommendations on qPCR/ddPCR assay validation by GCC. Bioanalysis 2022, 14, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. ICH guideline M10 on bioanalytical method validation and study sample analysis (EMEA/CHMP/ICH/172948/2019). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/ich-guideline-m10-bioanalytical-method-validation-step-5_en.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research & Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. M10 Bioanalytical Method Validation and Study Sample Analysis – Guidance for Industry. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/162903/download (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on bioanalytical method validation (EMEA/CHMP/EWP/192217/2009 Rev. 1 Corr. 2). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-bioanalytical-method-validation_en.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research & Center for Veterinary Medicine. Bioanalytical Method Validation – Guidance for Industry. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Bioanalytical-Method-Validation-Guidance-for-Industry.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Borchardt, M.A.; Boehm, A.B.; Salit, M.; Spencer, S.K.; Wigginton, K.R.; Noble, R.T. The Environmental Microbiology Minimum Information (EMMI) Guidelines: qPCR and dPCR Quality and Reporting for Environmental Microbiology. Environ Sci Technol 2021, 55, 10210–10223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedman, J.; Rådström, P. Overcoming inhibition in real-time diagnostic PCR. Methods Mol Biol 2013, 943, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedman, J.; Lavander, M.; Salomonsson, E.N.; Jinnerot, T.; Boiso, L.; Magnusson, B.; Rådström, P. Validation guidelines for PCR workflows in bioterrorism preparedness, food safety and forensics. Accreditation and Quality Assurance 2018, 23, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidstedt, M.; Rådström, P.; Hedman, J. PCR inhibition in qPCR, dPCR and MPS-mechanisms and solutions. Anal Bioanal Chem 2020, 412, 2009–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, H.; Kuze, Y.; Higuchi, T.; Matsumoto, S.I.; Yamamoto, S.; Goto, A.; Moriya, Y.; Hirabayashi, H. Development of a bioanalytical method for circulating human T cells in animals using Arthrobacter luteus-based quantitative polymerase chain reaction and its application in preclinical biodistribution studies. Regen Ther 2020, 15, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tichopad, A.; Didier, A.; Pfaffl, M.W. Inhibition of real-time RT-PCR quantification due to tissue-specific contaminants. Mol Cell Probes 2004, 18, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yama, I.N.; Garba, M.; Britton-Davidian, J.; Thiberville, S.D.; Dobigny, G.; Gould, E.A.; de Lamballerie, X.; Charrel, R.N. Comparative analysis of rodent tissue preservation methods and nucleic acid extraction techniques for virus screening purposes. J Virol Methods 2013, 189, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Hirabayashi, H. Novel Cell Quantification Method Using a Single Surrogate Calibration Curve Across Various Biological Samples. Aaps j 2023, 25, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittorf, P.; Bergmann, T.; Merlin, S.; Olgasi, C.; Pullig, O.; Sanzenbacher, R.; Zierau, M.; Walles, H.; Follenzi, A.; Braspenning, J. Regulatory-Compliant Validation of a Highly Sensitive qPCR for Biodistribution Assessment of Hemophilia A Patient Cells. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2020, 18, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tappenbeck, N.; Schroder, H.M.; Niebergall-Roth, E.; Hassinger, F.; Dehio, U.; Dieter, K.; Kraft, K.; Kerstan, A.; Esterlechner, J.; Frank, N.Y.; et al. In vivo safety profile and biodistribution of GMP-manufactured human skin-derived ABCB5-positive mesenchymal stromal cells for use in clinical trials. Cytotherapy 2019, 21, 546–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballikaya, S.; Sadeghi, S.; Niebergall-Roth, E.; Nimtz, L.; Frindert, J.; Norrick, A.; Stemler, N.; Bauer, N.; Rosche, Y.; Kratzenberg, V.; et al. Process data of allogeneic ex vivo-expanded ABCB5+ mesenchymal stromal cells for human use: off-the-shelf GMP-manufactured donor-independent ATMP. Stem Cell Res Ther 2020, 11, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebergall-Roth, E.; Frank, N.Y.; Ganss, C.; Frank, M.H.; Kluth, M.A. Skin-Derived ABCB5(+) Mesenchymal Stem Cells for High-Medical-Need Inflammatory Diseases: From Discovery to Entering Clinical Routine. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 24, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, M.; Nitsche, A.; Neumann, C.; Aumann, J.; Junghahn, I.; Fichtner, I. Sensitive PCR method for the detection and real-time quantification of human cells in xenotransplantation systems. Br J Cancer 2002, 87, 1328–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcoser, S.Y.; Kimmel, D.J.; Borgel, S.D.; Carter, J.P.; Dougherty, K.M.; Hollingshead, M.G. Real-time PCR-based assay to quantify the relative amount of human and mouse tissue present in tumor xenografts. BMC Biotechnol 2011, 11, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; et al. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, N.Y.; Pendse, S.S.; Lapchak, P.H.; Margaryan, A.; Shlain, D.; Doeing, C.; Sayegh, M.H.; Frank, M.H. Regulation of progenitor cell fusion by ABCB5 P-glycoprotein, a novel human ATP-binding cassette transporter. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 47156–47165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.Y.; Doddareddy, R. Considerations in the development and validation of real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction and its application in regulated bioanalysis to characterize the cellular kinetics of CAR-T products in clinical studies. Bioanalysis 2021, 13, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, A.; Islam, R.; Matys, K.; Williams, D. Best Practices in qPCR and dPCR Validation in Regulated Bioanalytical Laboratories. Aaps j 2022, 24, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsaro, B.; Yang, T.Y.; Murphy, R.; Sonderegger, I.; Exley, A.; Bertholet, S.; Dakappagari, N.; Dessy, F.; Garofolo, F.; Kierstead, L.; et al. 2020 White Paper on Recent Issues in Bioanalysis: Vaccine Assay Validation, qPCR Assay Validation, QC for CAR-T Flow Cytometry, NAb Assay Harmonization and ELISpot Validation (Part 3 - Recommendations on Immunogenicity Assay Strategies, NAb Assays, Biosimilars and FDA/EMA Immunogenicity Guidance/Guideline, Gene & Cell Therapy and Vaccine Assays). Bioanalysis 2021, 13, 415–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhart, L.; Bach, J.; Ban, J.; Tschachler, E. Melanin binds reversibly to thermostable DNA polymerase and inhibits its activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000, 271, 726–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, K.; Linge, C. The presence of melanin in genomic DNA isolated from pigmented cell lines interferes with successful polymerase chain reaction: a solution. Melanoma Res 1999, 9, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opel, K.L.; Chung, D.; McCord, B.R. A study of PCR inhibition mechanisms using real time PCR. J Forensic Sci 2010, 55, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bélec, L.; Authier, J.; Eliezer-Vanerot, M.C.; Piédouillet, C.; Mohamed, A.S.; Gherardi, R.K. Myoglobin as a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) inhibitor: a limitation for PCR from skeletal muscle tissue avoided by the use of Thermus thermophilus polymerase. Muscle Nerve 1998, 21, 1064–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilert, K.D.; Foran, D.R. Polymerase resistance to polymerase chain reaction inhibitors in bone. J Forensic Sci 2009, 54, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidstedt, M.; Hedman, J.; Romsos, E.L.; Waitara, L.; Wadsö, L.; Steffen, C.R.; Vallone, P.M.; Rådström, P. Inhibition mechanisms of hemoglobin, immunoglobulin G, and whole blood in digital and real-time PCR. Anal Bioanal Chem 2018, 410, 2569–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Soud, W.A.; Jönsson, L.J.; Râdström, P. Identification and characterization of immunoglobulin G in blood as a major inhibitor of diagnostic PCR. J Clin Microbiol 2000, 38, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Soud, W.A.; Rådström, P. Purification and characterization of PCR-inhibitory components in blood cells. J Clin Microbiol 2001, 39, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggett, J.F.; Novak, T.; Garson, J.A.; Green, C.; Morris-Jones, S.D.; Miller, R.F.; Zumla, A. Differential susceptibility of PCR reactions to inhibitors: an important and unrecognised phenomenon. BMC Res Notes 2008, 1, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killelea, T.; Ralec, C.; Bossé, A.; Henneke, G. PCR performance of a thermostable heterodimeric archaeal DNA polymerase. Front Microbiol 2014, 5, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Behrmann, O.; Hufert, F.; Dame, G.; Urban, G. Direct DNA and RNA detection from large volumes of whole human blood. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davalieva, K.; Efremov, G.D. Influence of salts and pcr inhibitors on the amplification capacity of three thermostable DNA polymerases. Macedonian Journal of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering 2010, 29, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Al-Soud, W.; Râdström, P. Capacity of nine thermostable DNA polymerases To mediate DNA amplification in the presence of PCR-inhibiting samples. Appl Environ Microbiol 1998, 64, 3748–3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psifidi, A.; Dovas, C.I.; Bramis, G.; Lazou, T.; Russel, C.L.; Arsenos, G.; Banos, G. Comparison of eleven methods for genomic DNA extraction suitable for large-scale whole-genome genotyping and long-term DNA banking using blood samples. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0115960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creane, M.; Howard, L.; O'Brien, T.; Coleman, C.M. Biodistribution and retention of locally administered human mesenchymal stromal cells: Quantitative polymerase chain reaction-based detection of human DNA in murine organs. Cytotherapy 2017, 19, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.K.; Hoseok, s.; Kim, G.S.; Hwang, N.S.; Choi, H.S. Optical spectroscopic imaging for cell therapy and tissue engineering. Appl Spectrosc Rev 2018, 53, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samejima, K.; Earnshaw, W.C. Trashing the genome: the role of nucleases during apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2005, 6, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitazumi, I.; Tsukahara, M. Regulation of DNA fragmentation: the role of caspases and phosphorylation. Febs j 2011, 278, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, T.; Osl, F.; Friess, T.; Stockinger, H.; Scheuer, W.V. Quantification of human Alu sequences by real-time PCR--an improved method to measure therapeutic efficacy of anti-metastatic drugs in human xenotransplants. Clin Exp Metastasis 2002, 19, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigent, J.; Herrero, A.; Ambroise, J.; Smets, F.; Deblandre, G.A.; Sokal, E.M. Human Progenitor Cell Quantification After Xenotransplantation in Rat and Mouse Models by a Sensitive qPCR Assay. Cell Transplant 2015, 24, 1639–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on human cell-based medicinal products (EMEA/CHMP/410869/2006). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-human-cell-based-medicinal-products_en.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2023).

| Parameter | Acceptance criteria | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Linearity | r2 ≥ 0.95 | 0.971 - 0.992 |

| Accuracy | Bias of the calculated cell number from the nominal cell number within ± 40% | Cals:intra-assay: -21% - 25%inter-assay: 10% - 13%QCs:intra-assay: -36% - 36%inter-assay: -18% - 8% |

| ≥ 75% of Cals and ≥ 67% of QCs meet the acceptance criterion for inter-assay accuracy | 100% of Cals and 100% of QCs met the acceptance criterion for inter-assay accuracy | |

| Precision | CV between a series of measurements ≤ 40% | Cals:intra-assay: -21% - 25%inter-assay: 10% - 13%QCs:intra-assay: -36% - 36%inter-assay: -18% - 8% |

| ≥ 75% of Cals and ≥ 67% of QCs meet the acceptance criterion for inter-assay precision | 100% of Cals and 100% of QCs met the acceptance criterion for inter-assay precision | |

| Quantification range | LLOQ = lowest cell concentration quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision | LLOQ: 125 human MSCs in 200 µl lysate |

| ULOQ = highest cell concentration quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision | ULOQ: 20,000 human MSCs in 200 µl lysate | |

| Specificity | No-template controls give either no amplification signal or a Cq value unequivocally distinguishable from the LLOQ | Assays 1 and 2:Cq value unequivocally distinguishable from the LLOQAssay 3:No amplification signal |

| DNA freeze-thaw stability | Bias of the cell number quantified in the frozen aliquot from that in the cooled aliquot within ± 40% | -14% - 14% |

| Matrix effects in 14 mouse tissues | Tissue-specific recovery rates determined and matrix factors calculated | |

| Assay No. | Objective | Slope | y-Intercept | Efficiency [%] | r2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Method validation | -4.8876 | 45.3621 | 60.177 | 0.990 |

| 2 | Method validation,matrix effects | -3.9656 | 41.0232 | 78.718 | 0.971 |

| 3 | Method validation,matrix effects | -3.5819 | 39.0348 | 90.187 | 0.992 |

| 4 | Matrix effects | -3.6903 | 38.9021 | 86.630 | 0.993 |

| 5 | Freeze-thaw stability | -4.6922 | 45.0217 | 63.350 | 0.994 |

|

Calibration standard Nominal cell number Replicates per assay |

Cal 1 | Cal 2 | Cal 3 | Cal 4 | Cal 5 | Cal 6 | Cal 7 | Blank | |

| 20,000 | 10,000 | 5000 | 1000 | 500 | 250 | 125 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 6 | ||

| Assay 1 | Cq, mean | 24.816 | 25.519 | 27.238 | 30.346 | 32.029 | 33.610 | 35.427 1 | 36.233 |

| Cell number,mean (SD) | 16,009 (1148) | 11,478 (236) | 5111 (248) | 1189 (165) | 535 (19) | 258 (51) | 110 (23) 1 | 74 (8) | |

| Bias [%] | -20 | 15 | 2 | 19 | 7 | 3 | -12 | ||

| CV [%] | 7 | 2 | 5 | 14 | 4 | 20 | 21 | ||

| Assay 2 | Cq, mean | 23.727 | 25.376 | 26.594 | 28.925 | 30.452 | 31.244 | 33.003 1 | 38.867 2 |

| Cell number,mean (SD) | 23,121 (2970) | 8961 (1921) | 4486 (1407) | 1162 (376) | 485 (172) | 314 (128) | 109 (37) 1 | 3 2 | |

| Bias [%] | 16 | -10 | -10 | 16 | -3 | 25 | -12 | ||

| CV [%] | 13 | 21 | 31 | 32 | 36 | 41 | 34 | ||

| Assay 3 | Cq, mean | 23.311 | 24.711 | 26.149 | 28.362 | 29.592 | 30.298 | 31.498 | 39.735 3 |

| Cell number,mean (SD) | 24,567 (1347) | 9994 (710) | 3962 (202) | 955 (47) | 435 (53) | 277 (40) | 128 (19) | 1 (1) 3 | |

| Bias [%] | 23 | 0 | -21 | -4 | -13 | 11 | 3 | ||

| CV [%] | 5 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 12 | 15 | 15 | ||

| Assays 1-3 | n (total) | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 18 | 14 | |

| Cell number,mean (SD) | 21,232 (4581) | 10,145 (1265) | 4520 (575) | 1102 (128) | 485 (50) | 283 (28) | 116 (11) | ||

| Inter-assay bias [%] | 6 | 1 | -10 | 10 | -3 | 13 | -7 | ||

| Inter-assay CV [%] | 22 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 9 | ||

|

Quality control standard Nominal cell number Replicates per assay |

QC 1 | QC 2 | QC 3 | QC 4 | QC 5 | NTC | |

| 15,000 | 5000 | 1250 | 625 | 125 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 3 | ||

| Assay 1 | Mean Cq | 25.419 | 27.444 | [36.747] 1 | 33.265 | 34.826 | 36.511 3 |

| Cell number, mean (SD) | 12,079 (1288) | 4647 (398) | [61 (22)] 1 | 400 2 | 152 (56) | 66 3 | |

| Bias [%] | -19 | -7 | [-95] 1 | -36 | 22 | ||

| CV [%] | 11 | 9 | [37] 1 | n.d. 2 | 36 | ||

| Assay 2 | Mean Cq | 23.852 | 25.846 | 28.558 | 29.877 | 32.739 | 39.978 5 |

| Cell number, mean (SD) | 18,410 (2984) 4 | 6780 (1139) | 1417 (316) | 649 (68) | 125 (28) | 2 5 | |

| Bias [%] | 23 | 36 | 13 | 4 | 0 | ||

| CV [%] | 16 | 17 | 22 | 11 | 22 | ||

| Assay 3 | Mean Cq | 24.133 | 26.096 | 28.349 | 29.419 | 31.536 | 40.861 6 |

| Cell number, mean (SD) | 14,481 (908) | 4112 (437) | 965 (90) | 484 (26) | 126 (24) | 0 6 | |

| Bias [%] | -3 | -18 | -23 | -23 | 1 | ||

| CV [%] | 6 | 11 | 9 | 5 | 19 | ||

| Assays 1-3 | n (total) | 8 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 18 | |

| Cell number, mean (SD) | 14,990 (3196) | 5180 (1412) | 1191 (320) | 511 (127) | 135 (15) | ||

| Inter-assay bias [%] | 0 | 4 | -5 | -18 | 8 | ||

| Inter-assay CV [%] | 21 | 27 | 27 | 25 | 11 | ||

| Tissue 2 | Spike recovery rates (%) | Matrix factor 3,4 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assay 2Mean (% CV) | Assay 3Mean (% CV) | Assay 4Mean (% CV) | Assays 2 - 4 | Assays 2 & 3 3 | ||||||

| Mean | SD | % CV | Mean | SD | % CV | |||||

| Skin | 144 (45) | 147 (22) | 29 (28) | 107 | 67 | 63 | 146 | 2 | 1 | 0.68 |

| Muscle | 131 (29) | 121 (5) | 31 (38) | 94 | 55 | 58 | 126 | 7 | 6 | 0.79 |

| Lymph nodes | 113 (38) | 65 (27) | 45 (16) | 74 | 35 | 47 | 89 | 34 | 38 | 1.12 |

| Liver | 249 (49) | 98 (7) | 26 (42) | 124 | 114 | 92 | 174 | 107 | 62 | 0.57 |

| Spleen | 37 (94) | 45 (36) | 12 (38) | 31 | 17 | 55 | 41 | 6 | 14 | 2.44 |

| Lung | 28 (94) | 48 (56) | 10 (23) | 29 | 19 | 66 | 38 | 14 | 37 | 2.63 |

| Brain | 19 (11) | 48 (38) | 11 (70) | 26 | 19 | 75 | 34 | 21 | 61 | 2.94 |

| Bone | 38 (23) | 81 (26) | 13 (21) | 44 | 34 | 78 | 60 | 30 | 51 | 1.67 |

| Kidney | 33 (25) | 49 (29) | 12 (10) | 31 | 19 | 59 | 41 | 11 | 28 | 2.44 |

| Thymus | 70 (23) | 70 (37) | 21 (29) | 54 | 28 | 53 | 70 | 0 | 0 | 1.43 |

| Thyroid | 100 (44) | 62 (34) | 42 (35) | 68 | 29 | 43 | 81 | 27 | 33 | 1.23 |

| Ovaries | 49 (14) | 28 (24) | 23 (11) | 33 | 14 | 41 | 39 | 15 | 39 | 2.56 |

| Testes | 18 (39) | 39 (43) | 17 (59) | 25 | 12 | 50 | 29 | 15 | 52 | 3.45 |

| Blood | 10 (80) | 11 (20) | 3 (22) | 8 | 4 | 54 | 11 | 1 | 7 | 9.09 |

| Inhibitor | Tissue | Mode of action | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melanin | Skin, melanoma metastases | Reversible binding to thermostable DNA polymerases | [45] |

| Binding to DNA, thereby limiting the amount of available template | [46,47] | ||

| Myoglobin | Muscle | Inhibition of Taq DNA polymerase | [48] |

| Collagen | Bone | Inhibition of thermostable DNA polymerases, binding to template DNA | [47,49] |

| Calcium ions | Inhibition of thermostable DNA polymerases, likely by competition with the polymerase cofactor Mg2+ | [47,49] | |

| Hemoglobin | Blood | Impairment of DNA polymerase activity, fluorescence quenching through binding to or interacting with fluorescent dyes | [50] |

| Immunoglobulin G | Binding to single-stranded genomic DNA, thereby hindering primer annealing or binding of DNA polymerase | [50,51] | |

| Lactoferrin | Release of iron ions | [52] | |

| EDTA 1 | Chelation of the polymerase cofactor Mg2+ | [53,54] | |

| Heparin 1 | Competition with template DNA, chelation of the polymerase cofactor Mg2+ | [52,54] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).