Submitted:

25 May 2023

Posted:

29 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Bacterial Strains, Cloning, and Culture Conditions

2.3. Protein Expression and Analysis

2.4. Enzymatic Reaction

2.5. Optimization in Vitro Reaction

2.6. Reaction with Different Sugar Donors and Commercial Enzyme

2.7. In Vivo Preparation of Resveratrol Glucosides

2.8. Preparative Scale Production of Resveratrol Glucosides

2.9. Analytical Methods

2.10. Assay of Resveratrol Glucosides for Cosmetic Activities

3. Results

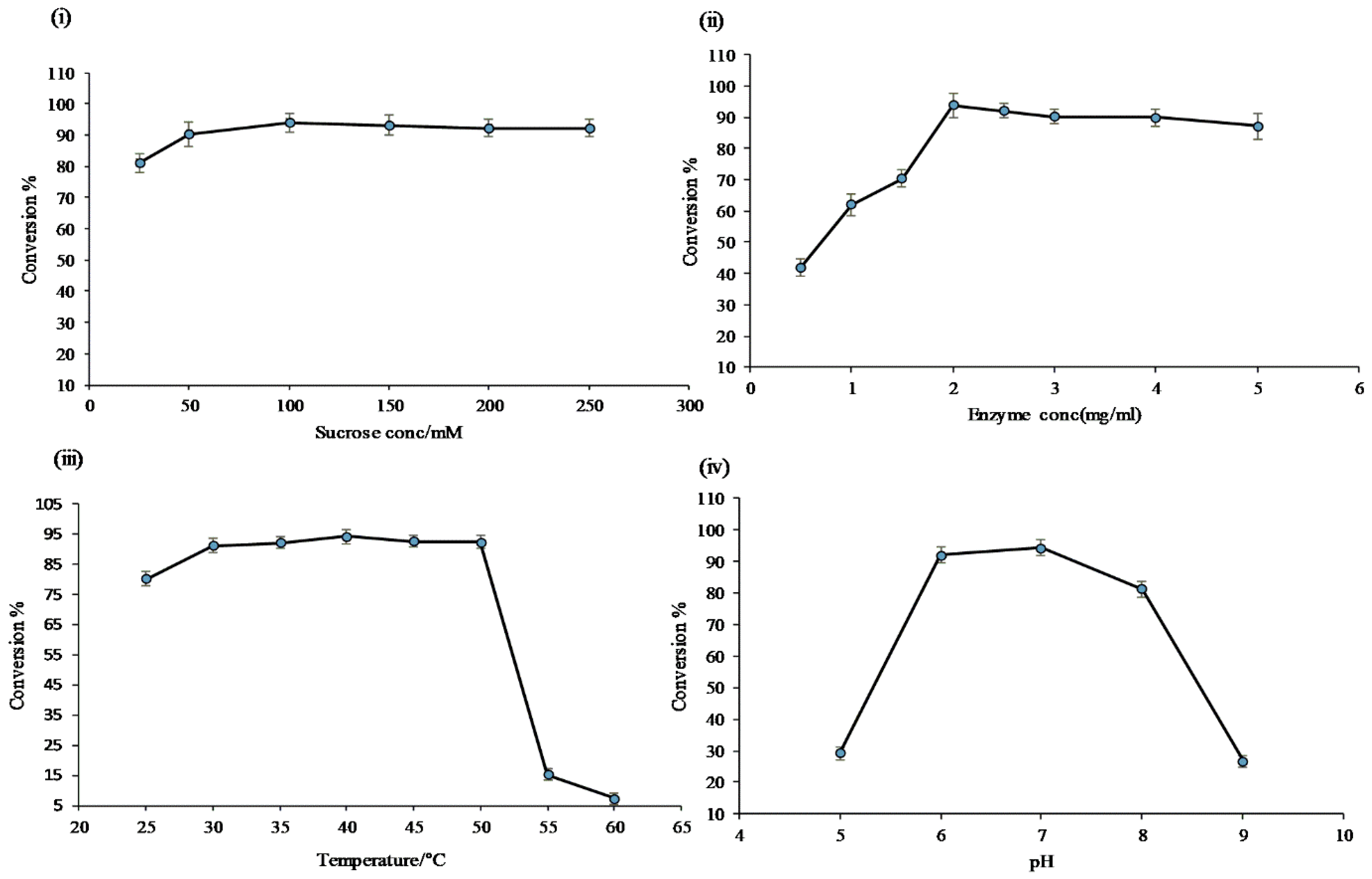

3.1. In Vitro Reaction of Resvatrol

3.2. Effect of Using Different Sugar Donors and Commercial Enzyme

3.3. Preparative Scale Production of Resveratrol Glucosides

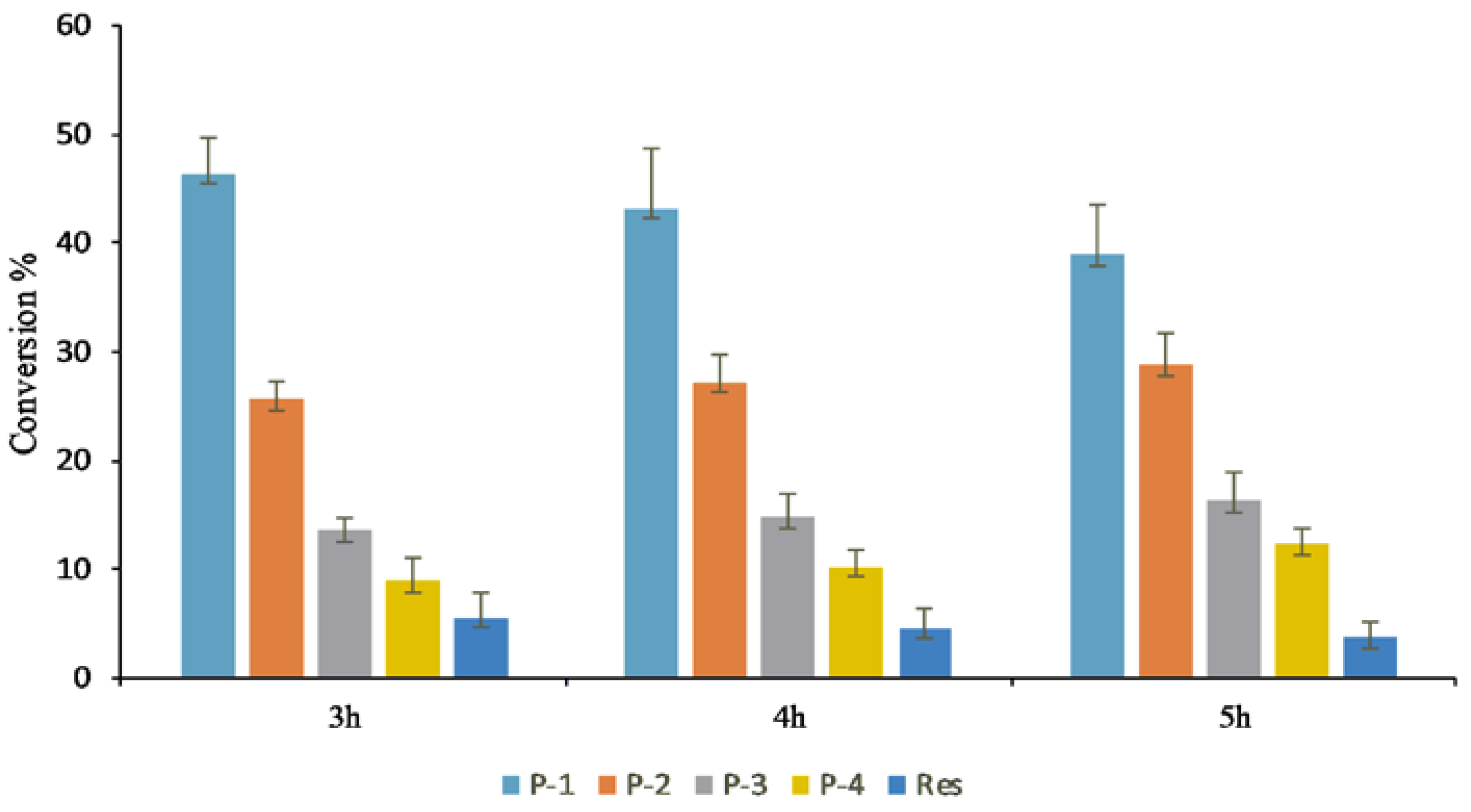

3.4. In Vivo Production of Resveratrol Glucoside

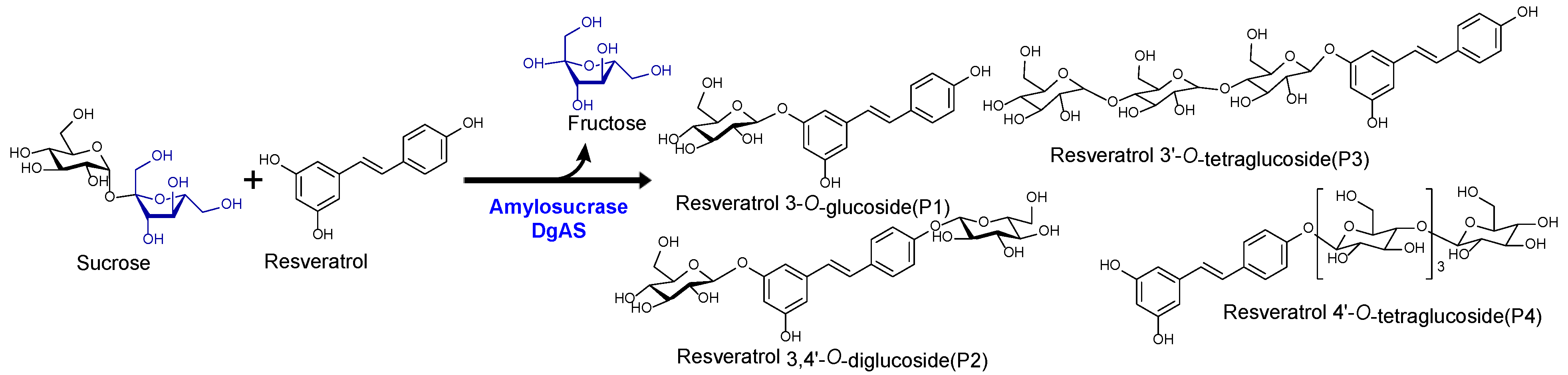

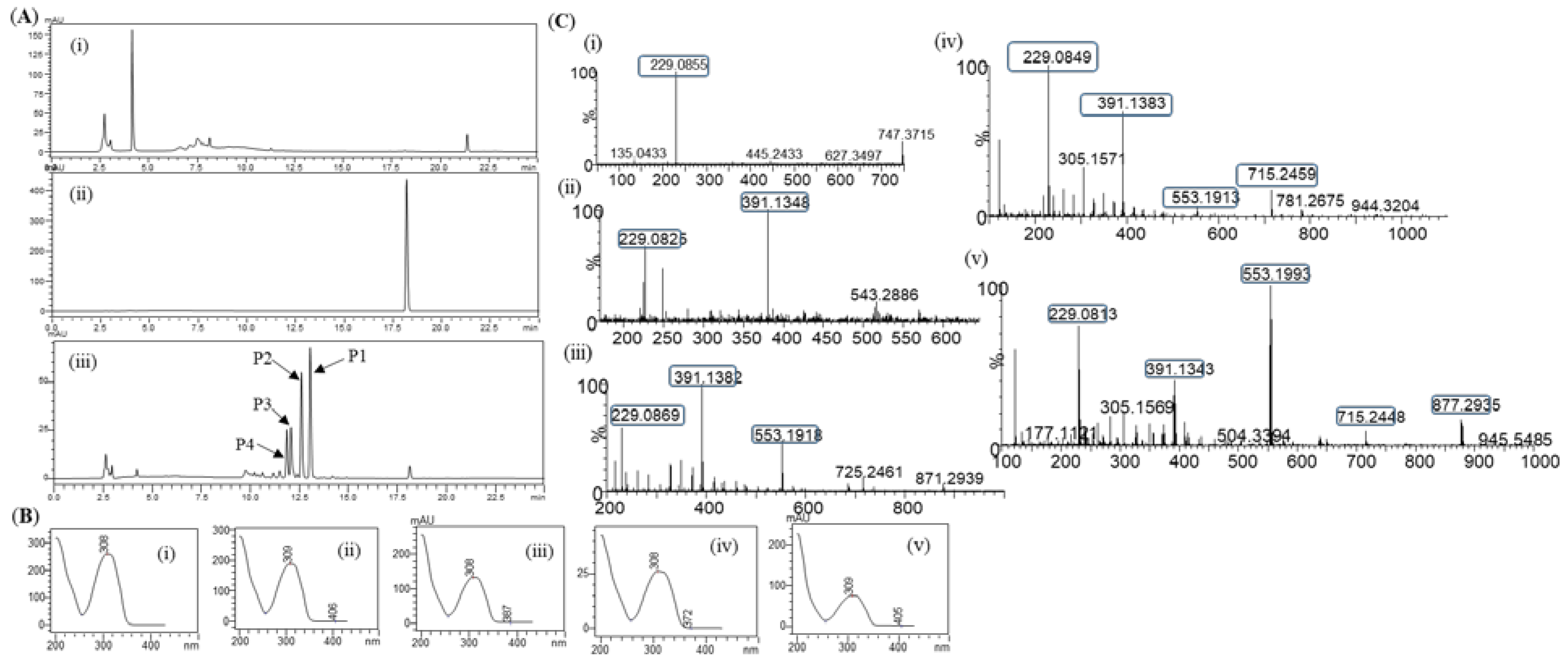

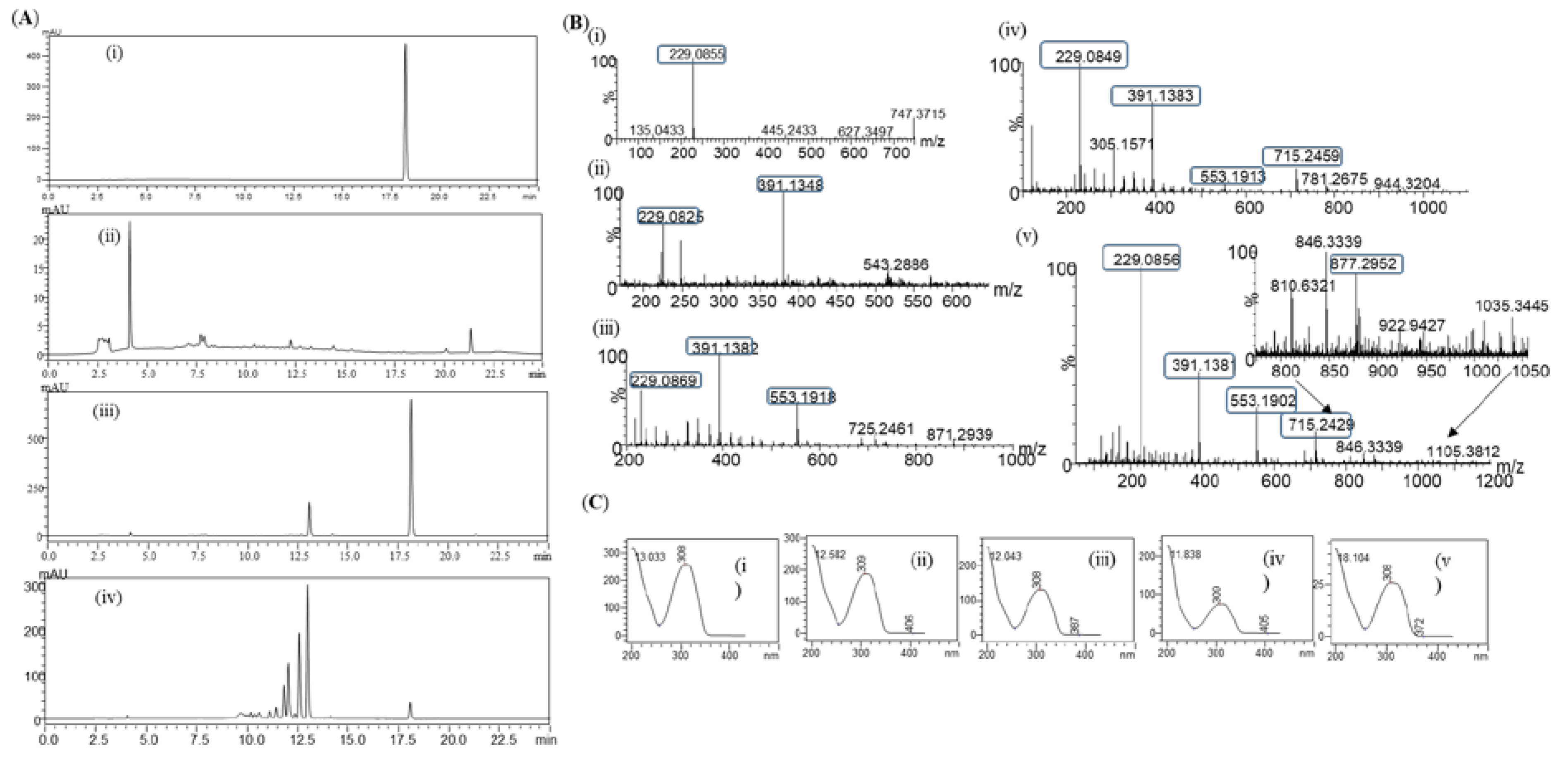

3.5. Structural Elucidation of Resveratrol Glycosides Products

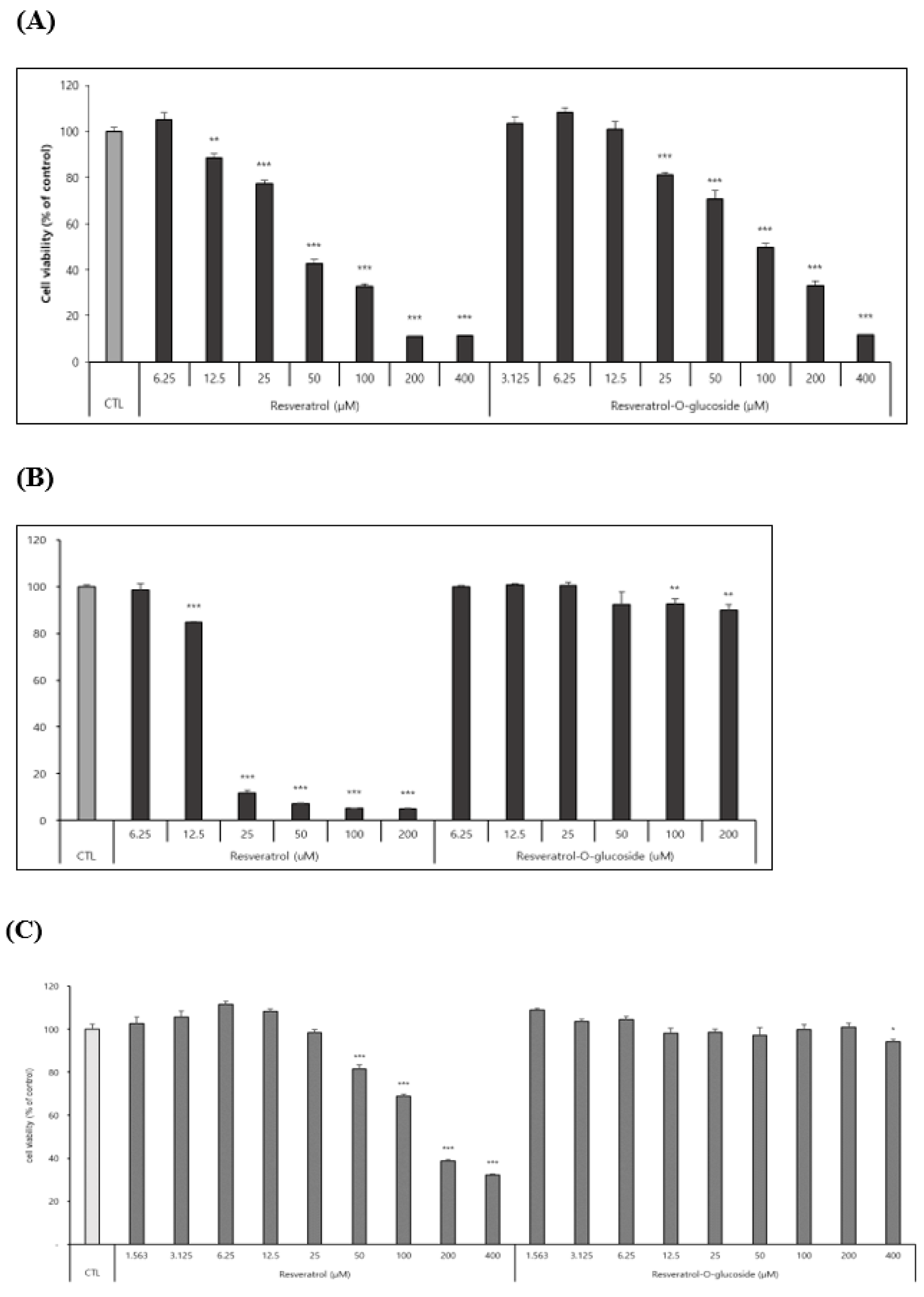

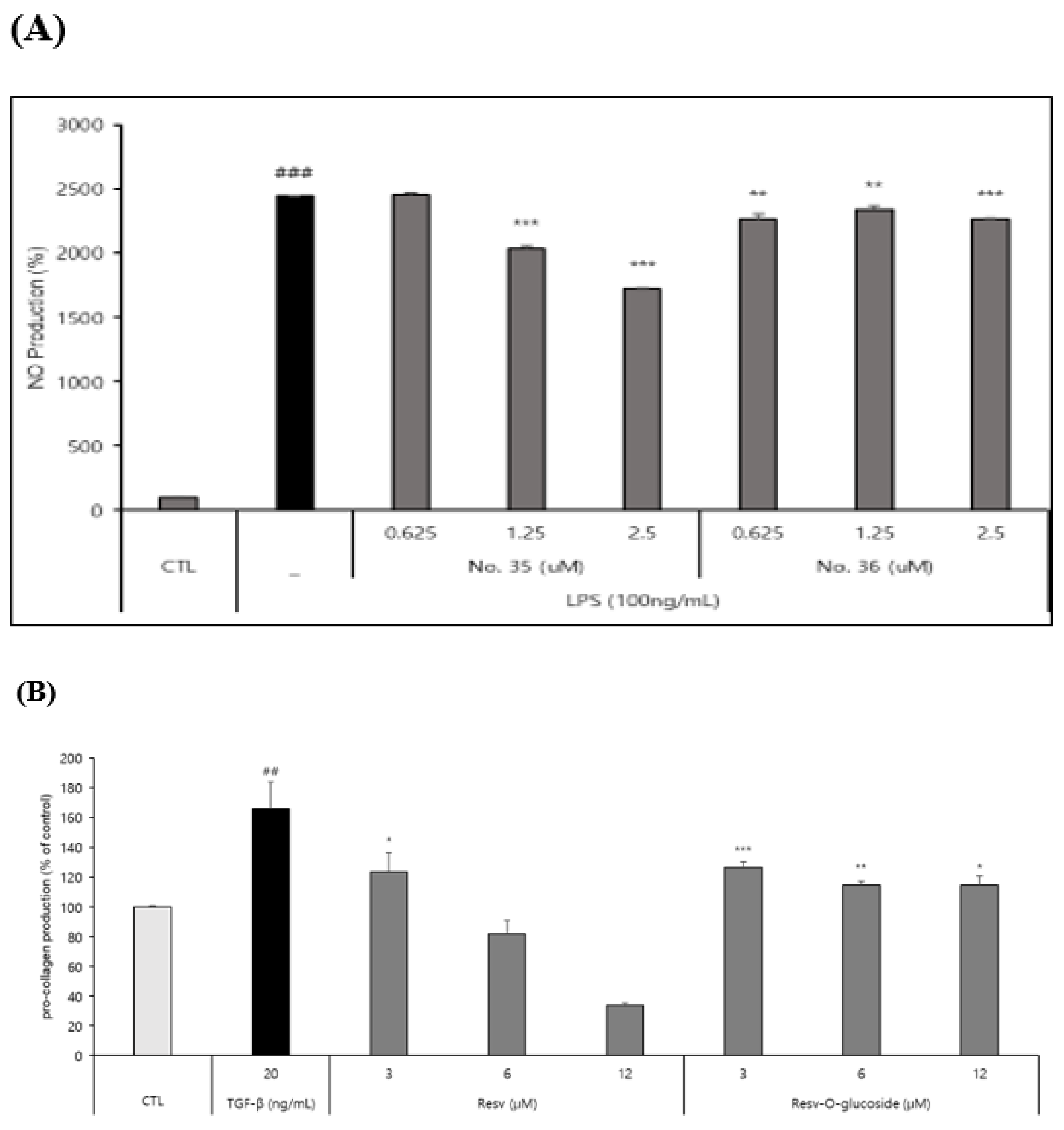

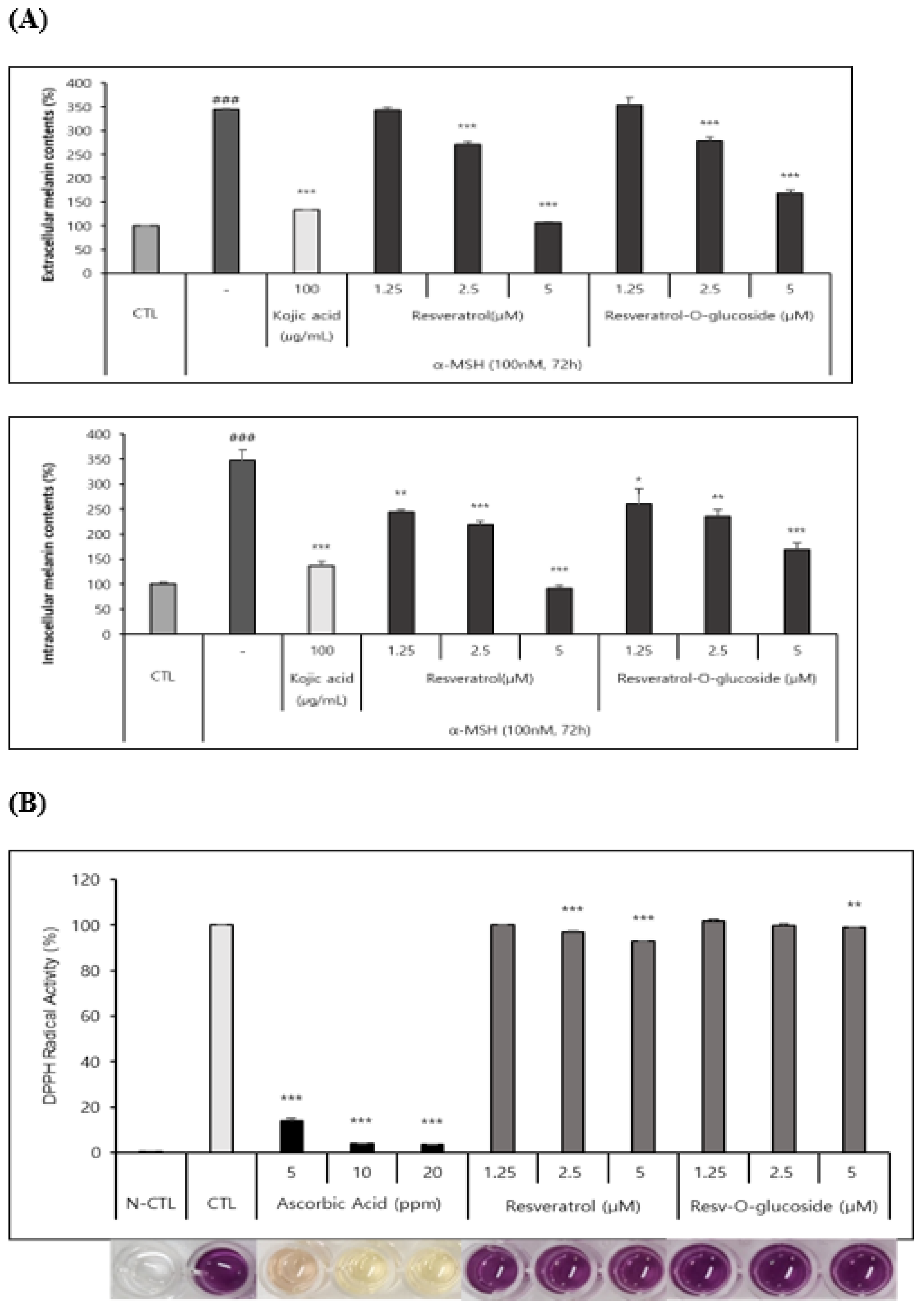

3.6. Cosmetic Activities of Resveratrol Glucosides

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

References

- Pandey, R.P.; Parajuli, P.; Shin, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Hong, Y.S.; Park, Y. Il; Kim, J.S.; Sohng, J.K. Enzymatic biosynthesis of novel resveratrol glucoside and glycoside derivatives. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 7235–7243. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02076-14. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Li, L.; Linhardt, R.J.; Yan, Y. Regulating malonyl-CoA metabolism via synthetic antisense RNAs for enhanced biosynthesis of natural products. Metab. Eng. 2015, 29, 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymben.2015.03.018. [CrossRef]

- Gambini, J.; Inglés, M.; Olaso, G.; Lopez-Grueso, R.; Bonet-Costa, V.; Gimeno-Mallench, L.; Mas-Bargues, C.; Abdelaziz, K.M.; Gomez-Cabrera, M.C.; Vina, J.; et al. Properties of Resveratrol: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies about Metabolism, Bioavailability, and Biological Effects in Animal Models and Humans. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/837042. [CrossRef]

- Pangeni, R.; Sahni, J.K.; Ali, J.; Sharma, S.; Baboota, S. Resveratrol: Review on therapeutic potential and recent advances in drug delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2014, 11, 1285–1298. https://doi.org/10.1517/17425247.2014.919253. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-J.; Ahmad, F.; Philp, A.; Baar, K.; Williams, T.; Luo, H.; Ke, H.; Rehmann, H.; Taussig, R.; Brown, A.L.; et al. Resveratrol ameliorates aging-related metabolic phenotypes by inhibiting cAMP phosphodiesterases. BMC Proc. 2012, 6, 6561. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-6561-6-s3-p73. [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Yu, W.; Ji, W.; Lin, Z.; Tan, S.; Duan, K.; Dong, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, N. Early versus delayed administration of norepinephrine in patients with septic shock. Crit. Care 2014, 18, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-014-0532-y. [CrossRef]

- Petrovski, G.; Gurusamy, N.; Das, D.K. Resveratrol in cardiovascular health and disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1215, 22–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05843.x. [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.R.; Lokhandwala, M.F.; Banday, A.A. Resveratrol prevents endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling and attenuates development of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 667, 258–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.05.026. [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.P. Isoflavones: Chemistry, analysis, functions and effects on health and cancer. Asian Pacific J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 7001–7010. https://doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.17.7001. [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, K.; Humayoun Akhtar, M. An updated review of dietary isoflavones: Nutrition, processing, bioavailability and impacts on human health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1280–1293. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2014.989958. [CrossRef]

- Szeja, W. la.; Grynkiewicz, G.; Rusin, A. Isoflavones, their Glycosides and Glycoconjugates. Synthesis and Biological Activity. Curr. Org. Chem. 2016, 21, 218–235. https://doi.org/10.2174/1385272820666160928120822. [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Liu, J. Resveratrol: a review of plant sources, synthesis, stability, modification and food application. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 1392–1404. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.10152. [CrossRef]

- Zupančič, Š.; Lavrič, Z.; Kristl, J. Stability and solubility of trans-resveratrol are strongly influenced by pH and temperature. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015, 93, 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.04.002. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zou, Y.; Liang, X.; Peng, Y.; McClements, D.J.; Hu, K. Encapsulation of resveratrol in zein/pectin core-shell nanoparticles: Stability, bioaccessibility, and antioxidant capacity after simulated gastrointestinal digestion. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 93, 261–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.02.039. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, Y.; Gao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yi, J. Enhanced pH and thermal stability, solubility and antioxidant activity of resveratrol by nanocomplexation with α-lactalbumin; 2018; Vol. 9; ISBN 1021382620.

- Zhang, F.; Khan, M.A.; Cheng, H.; Liang, L. Co-encapsulation of α-tocopherol and resveratrol within zein nanoparticles: Impact on antioxidant activity and stability. J. Food Eng. 2019, 247, 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2018.11.021. [CrossRef]

- Caddeo, C.; Pucci, L.; Gabriele, M.; Carbone, C.; Fernàndez-Busquets, X.; Valenti, D.; Pons, R.; Vassallo, A.; Fadda, A.M.; Manconi, M. Stability, biocompatibility and antioxidant activity of PEG-modified liposomes containing resveratrol. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 538, 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.12.047. [CrossRef]

- Ravetti, S.; Clemente, C.; Brignone, S.; Hergert, L.; Allemandi, D.; Palma, S. Ascorbic acid in skin health. Cosmetics 2019, 6, 6–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/COSMETICS6040058. [CrossRef]

- Boo, Y.C. Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C) as a Cosmeceutical to Increase Dermal Collagen for Skin Antiaging Purposes: Emerging Combination Therapies. Antioxidants 2022, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11091663. [CrossRef]

- Gull, M.; Pasek, M.A. The role of glycerol and its derivatives in the biochemistry of living organisms, and their prebiotic origin and significance in the evolution of life. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11010086. [CrossRef]

- Kruschitz, A.; Nidetzky, B. Biocatalytic Production of 2-α- d -Glucosyl-glycerol for Functional Ingredient Use: Integrated Process Design and Techno-Economic Assessment. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 1246–1255. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c07210. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.W.; Kotta, S.; Ansari, S.H.; Sharma, R.K.; Ali, J. Enhanced dissolution and bioavailability of grapefruit flavonoid Naringenin by solid dispersion utilizing fourth generation carrier. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2015, 41, 772–779. https://doi.org/10.3109/03639045.2014.902466. [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y. ming; Yu, H.; Wu, P.; Li, S.; Han, L.; Gunatilaka, A.A.L.; et al. Methylglucosylation of aromatic amino and phenolic moieties of drug-like biosynthons by combinatorial biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, E4980–E4989. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1716046115. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.G.; Yang, S.M.; Kim, S.Y.; Cha, M.N.; Ahn, J.H. Biosynthesis and production of glycosylated flavonoids in Escherichia coli: current state and perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 2979–2988. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-015-6504-6. [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, S.; Sharma, K.; Zha, J.; Guleria, S.; Koffas, M.A.G. Recent advances in the recombinant biosynthesis of polyphenols. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02259. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Park, H.; Na, D.; Lee, S.Y. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of phenol from glucose. Biotechnol.J.2013, 9(5), 621-629.

- Shomar, H.; Gontier, S.; Van Den Broek, N.J.F.; Tejeda Mora, H.; Noga, M.J.; Hagedoorn, P.L.; Bokinsky, G. Metabolic engineering of a carbapenem antibiotic synthesis pathway in Escherichia coli. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018, 14, 794–800. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-018-0084-6. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-T.; Rha, C.-S.; Jung, Y.S.; Kim, Y.-J.; Jung, D.-H.; Seo, D.-H.; Park, C.-S. Comparative study on amylosucrases derived from Deinococcus species and catalytic characterization and use of amylosucrase derived from Deinococcus wulumuqiensis. Amylase 2019, 3, 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1515/amylase-2019-0002. [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, A.T.; Jang, D.; Kim, M.S.; Seo, D.H.; Nam, T.G.; Rha, C.S.; Park, C.S; Kim, D.O. Enrichment of Polyglucosylated Isoflavones from soybean isoflavone aglycones using optimized amylosucrase transglycosylation. Molecules, 2020, 25(1), 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25010181. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Kim, T.S.; Parajuli, P.; Pandey, R.P.; Sohng, J.K. Sustainable production of dihydroxybenzene glucosides using immobilized amylosucrase from Deinococcus geothermalis. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 28, 1447–1456. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1805.05054. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Qi, T.; Xu, L.; Lu, L.; Xiao, M. Recent progress in the enzymatic glycosylation of phenolic compounds. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 2016, 35, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/07328303.2015.1137580. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Pandey, A.K. Chemistry and Biological Activities of Flavonoids: An Overview. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013, 2013, 162750. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/162750. [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.Z.; Liu, R.X.; Wang, D.P.; Wang, X.; Dai, C.C. Biocatalysis and biotransformation of resveratrol in microorganisms. Biotechnol. Lett. 2015, 37, 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10529-014-1651-x. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, P.; Fan, Y.; Bao, H.; Du, G.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J. Multivariate modular metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli to produce resveratrol from l-tyrosine. J. Biotechnol. 2013, 167, 404–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.07.030. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Schneider, K.; Kristensen, M.; Borodina, I.; Nielsen, J. Engineering yeast for high-level production of stilbenoid antioxidants. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36827. [CrossRef]

- Choi, O.; Wu, C.Z.; Kang, S.Y.; Ahn, J.S.; Uhm, T.B.; Hong, Y.S. Biosynthesis of plant-speciWc phenylpropanoids by construction of an artificial biosynthetic pathway in Escherichia coli. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 38, 1657–1665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10295-011-0954-3. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Pandey, R.P.; Sohng, J.K. Biosynthesis of resveratrol and piceatannol in engineered microbial strains: achievements and perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 2959–2972. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-019-09672-8. [CrossRef]

- Fauconneau, B.; Waffo-teguop, P.; Huguet, F.; Barrier, L.; Decendit, A.; Merillon, J.M. Comparative study of radical scavenger and antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds from Vitis vinifera cell cultures using in vitro tests. Life Sci. 1997, 61, 2103–2110.

- Choi, O.; Lee, J.K.; Kang, S.Y.; Pandey, R.P.; Sohng, J.K.; Ahn, J.S.; Hong, Y.S. Construction of artificial biosynthetic pathways for resveratrol glucoside derivatives. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 24, 614–618. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1401.01031. [CrossRef]

- Moulis, C.; André, I.; Remaud-Simeon, M. GH13 amylosucrases and GH70 branching sucrases, atypical enzymes in their respective families. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 2661–2679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-016-2244-8. [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.H.; Jung, J.H.; Jung, D.H.; Park, S.; Yoo, S.H.; Kim, Y.R.; Park, C.S. An unusual chimeric amylosucrase generated by domain-swapping mutagenesis. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2016, 86, 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enzmictec.2016.01.004. [CrossRef]

- Rha, C.S.; Jung, Y.S.; Seo, D.H.; Kim, D.O.; Park, C.S. Site-specific α-glycosylation of hydroxyflavones and hydroxyflavanones by amylosucrase from Deinococcus geothermalis. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2019, 129, 109361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enzmictec.2019.109361. [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.J.; Seo, D.H.; Jung, J.H.; Cha, J.; Kim, T.J.; Kim, Y.W.; Park, C.S. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a new amylosucrase from Alteromonas macleodii. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2009, 73, 1505–1512. https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb.80891. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Yan, Y. Bioproduction of resveratrol. Biotechnol. Nat. Prod. 2017, 61–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-67903-7_3. [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H.; Seo, D.H.; Ha, S.J.; Song, M.C.; Cha, J.; Yoo, S.H.; Kim, T.J.; Baek, N.I.; Baik, M.Y.; Park, C.S. Enzymatic synthesis of salicin glycosides through transglycosylation catalyzed by amylosucrases from Deinococcus geothermalis and Neisseria polysaccharea. Carbohydr. Res. 2009, 344, 1612–1619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carres.2009.04.019. [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.H.; Jung, J.H.; Ha, S.J.; Song, M.C.; Cha, J.; Yoo, S.H.; Kim, T.J.; Baek, N.I.; Park, C.S. Highly selective biotransformation of arbutin to arbutin-α-glucoside using amylosucrase from Deinococcus geothermalis DSM 11300. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2009, 60, 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcatb.2009.04.006. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, H.; Kamel, R.; El-Sayed, N. Dermal anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-aging effects of Compritol ATO-based Resveratrol colloidal carriers prepared using mixed surfactants. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 541, 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.01.054. [CrossRef]

- Honisch, C.; Osto, A.; Dupas de Matos, A.; Vincenzi, S.; Ruzza, P. Isolation of a tyrosinase inhibitor from unripe grapes juice: A spectrophotometric study. Food Chem. 2020, 305, 125506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125506. [CrossRef]

- Skoczynska, A., Budzisz, E., Trznadel-Grodzka, E., and Rotsztehn, H. Melanin and Lipofuscin. Adv. dermatology Allergol. 2017, 34 (2), 1.

- Zolghadri, S.; Bahrami, A.; Hassan Khan, M.T.; Munoz-Munoz, J.; Garcia-Molina, F.; Garcia-Canovas, F.; Saboury, A.A. A comprehensive review on tyrosinase inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019, 34, 279–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/14756366.2018.1545767. [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, A.; Panzella, L.; Monfrecola, G.; d’Ischia, M. Pheomelanin-induced oxidative stress: Bright and dark chemistry bridging red hair phenotype and melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014, 27, 721–733. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcmr.12262. [CrossRef]

- Smit, N.P.M.; Van Nieuwpoort, F.A.; Marrot, L.; Out, C.; Poorthuis, B.; Van Pelt, H.; Meunier, J.R.; Pavel, S. Increased melanogenesis is a risk factor for oxidative DNA damage - Study on cultured melanocytes and atypical nevus cells. Photochem. Photobiol. 2008, 84, 550–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00242.x. [CrossRef]

- Okura, M.; Yamashita, T.; Ishii-Osai, Y.; Yoshikawa, M.; Sumikawa, Y.; Wakamatsu, K.; Ito, S. Effects of rhododendrol and its metabolic products on melanocytic cell growth. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2015, 80, 142–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2015.07.010. [CrossRef]

- De La Lastra, C.A.; Villegas, I. Resveratrol as an anti-inflammatory and anti-aging agent: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2005, 49, 405–430. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.200500022. [CrossRef]

- López-Vélez, M.; Martínez-Martínez, F.; Valle-Ribes, C. Del The Study of Phenolic Compounds as Natural Antioxidants in Wine. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2003, 43, 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408690390826509. [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, C.; Simon-Assmann, P.; Kedinger, M.; Evans, G.S. Cytokines modulate fibroblast phenotype and epithelial-stroma interactions in rat intestine. Gastroenterology 1997, 112, 826–838. https://doi.org/10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9041244. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.H.; Lin-Shiau, S.Y.; Lin, J.K. Suppression of nitric oxide synthase and the down-regulation of the activation of NFκB in macrophages by resveratrol. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 126, 673–680. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0702357. [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, T.L.; Koop, D.R. Effects of the wine polyphenolics quercetin and resveratrol on pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999, 57, 941–949. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00002-7. [CrossRef]

- Tommasini, S.; Raneri, D.; Ficarra, R.; Calabrò, M.L.; Stancanelli, R.; Ficarra, P. Improvement in solubility and dissolution rate of flavonoids by complexation with β-cyclodextrin. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2004, 35, 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0731-7085(03)00647-2. [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.; Lee, S.; Park, H.; Cha, J. Enzymatic Synthesis of Resveratrol α-Glucoside by Amylosucrase of Deinococcus geothermalis. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 1692–1700. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.2108.08034. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).