1. Introduction

Climate change is one of the most compelling issues of the twenty-first century (Solnørdal and Foss, 2018). This multifaceted challenge impinges upon a wide range of areas, including politics, the business world, and personal choices (Solnørdal and Foss, 2018). In this regard, energy efficiency is paramount to decrease firms’ climate footprint while enhancing their competitiveness (Bensouda and Benali, 2022b). Energy efficiency refers to the process of reducing energy consumption to its lowest possible level, without compromising the quality of production, the profitability, and the quality of life (Çengel, 2011; Lawrence et al., 2019).

A substantial body of the existing literature points to energy efficiency multiple benefits at the firm level (Russell, 2015; Zhang et al., 2015; Killip et al, 2019; Lung et al., 2019). However, energy efficiency potential is still untapped (Bensouda and Benali, 2022b), which means that there is a difference between energy efficiency potential and the current energy efficiency level (Solnørdal and Foss, 2018).

The energy efficiency gap is attributable to the existence of factors that impede the adoption of EEM, these factors are referred to as energy efficiency barriers (Bensouda and Benali, 2022a).

The empirical literature found that several barriers hinder energy efficiency within firms, including financial factors (Hill, 2019), organizational factors (Soepardi and Thollander, 2018), and behavioral factors (Abrardi, 2019; Bensouda and Benali, 2022a). Energy efficiency barriers could be classified into internal and external barriers to energy efficiency (Cagno et al., 2013). External barriers to energy efficiency are associated with institutional settings, while internal barriers are linked to internal capabilities and behaviors (Cattaneo, 2019).

In the current study, we will focus on the effect of internal barriers to energy efficiency on the implementation of EEMs, namely the competing interests within firms, the lack of information regarding energy efficiency, and the low technical competence within firms.

Competing interests could impede the adoption of EEMs within industrial firms, by attaching a high importance on expanding production capacity to the detriment of energy issues that could be beneficial as well (Soepardi and Thollander, 2018).

The lack of information concerning energy efficiency opportunities leads to non-optimal decisions regarding energy issues, or even the non-implementation of EEMs (Cagno et al, 2013).

The low technical competence within industrial firms is noticeable when it comes to sensing energy efficiency opportunities and integrating energy efficiency measures into the existing internal processes (Cagno et al., 2013).

We believe it is relevant to examine the effect of these internal barriers on the implementation of EEMs within the Moroccan industrial sector for the following reasons:

First, the industrial sector is well known for being an energy-intensive sector, a sector that could play a central role in decreasing the global energy consumption and in closing the energy efficiency gap (Bensouda and Benali, 2023). Second, in the Moroccan context, the industrial sector consumes one quarter of the overall energy production (Bensouda and Benali, 2022b); It is therefore relevant to explore the effect of internal barriers to energy efficiency within the Moroccan industrial sector in order to determine the most appropriate means to reduce their intensity.

Furthermore, in the current study, we explore the role of energy audits in tackling internal barriers to energy efficiency.

Energy audit is defined as an analysis of energy use within firms’ facilities in order to assess energy efficiency opportunities and identify avenues for energy savings (Thumann and Younger, 2008). Energy audits are powerful vehicles for encouraging firms to undertake energy efficiency investments (Kalantzis and Revoltella, 2019). Energy audits are important within the industrial sector for the following reasons:

To begin with, energy audits lead to cost savings within firms via lowering cost of maintenance, tracking energy savings, and enhancing equipment’s age (Katole and Katole, 2016). In addition, energy audits promote greater comforts within the workplace. Moreover, energy audits help firms to comply with current or potential regulations (Katole and Katole, 2016). Furthermore, several studies consider energy audits to be excellent instruments to overcome internal barriers to energy efficiency, including information barriers (Kalantzis and Revoltella, 2019), competing interests and competence related barriers (Chiaroni et al, 2017).

Overall, we explore in this study, First of all, the negative direct effect of competing interests, the lack of information and the low technical competence on the adoption of EEMs within the Moroccan industrial sector; Second of all, the positive direct effect of energy audits on the adoption of EEMs within the Moroccan industrial sector; Finally, the indirect moderating effect of energy audits on mitigating the negative effect of internal barriers to energy efficiency on the adoption of EEMs within the Moroccan industrial sector.

To the best of our knowledge, no empirical study in Morocco had put the emphasis on the role of energy audits on mitigating the negative effect of competing interests, the lack of information and the low technical competence on the adoption of EEMs within Moroccan industrial firms (Mohamed, 2017), that constitutes the originality of our study.

In the second section, we present our research model, the theorical background and our hypotheses. In the third section, we explain the method of the study. Then, in the fourth section, we present our results. Subsequently, in the fifth section, we discuss the findings of the study. Finally, in the sixth section, we elaborate on our study’s policy implications.

2. Theorical Background and Research Hypotheses

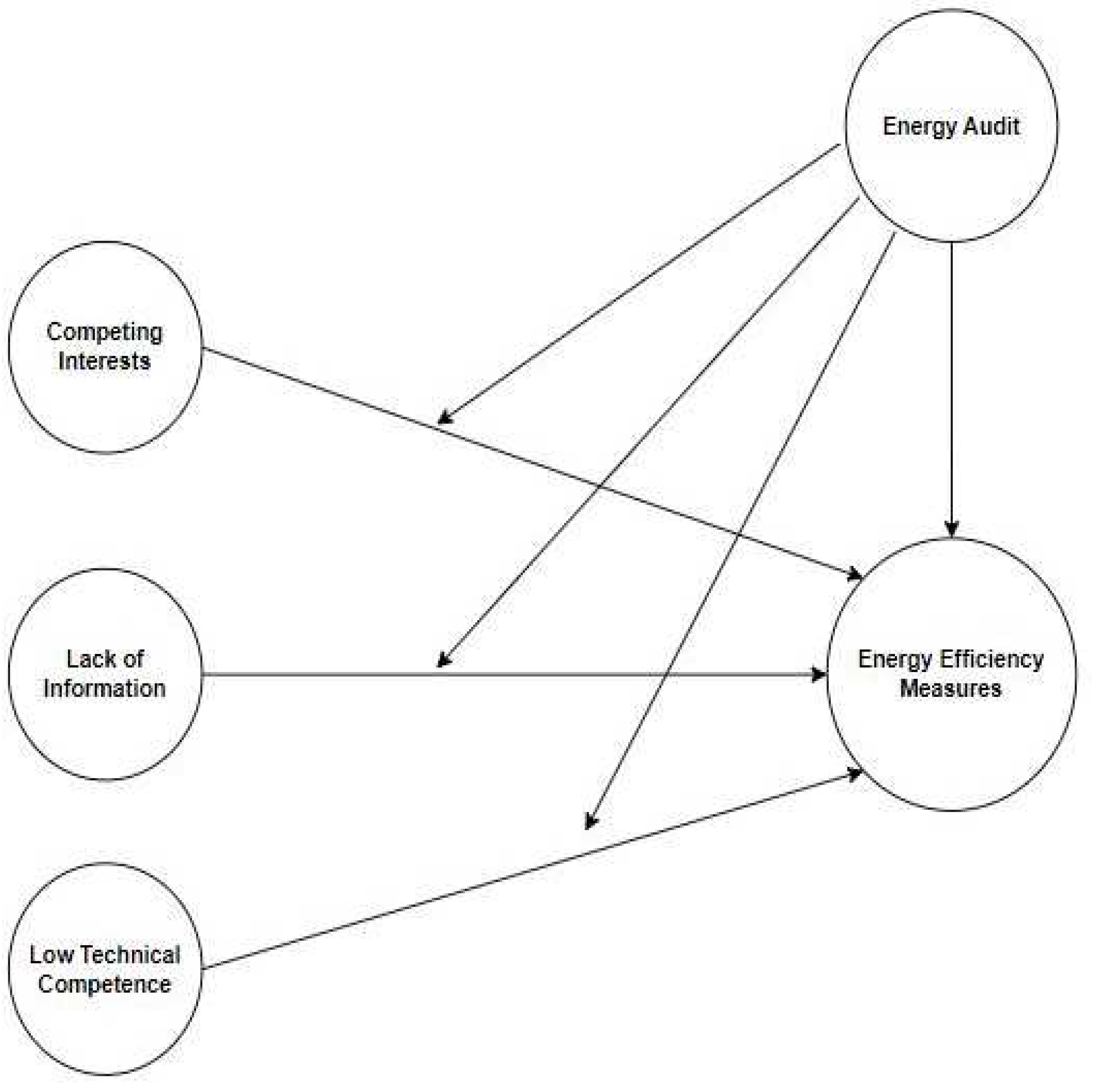

We build a model that examines the effect of competing interests, the lack of information and the low technical competence on EEMs’ adoption. We also explore the effect of energy audits on mitigating the negative effect of the aforementioned internal barriers on EEMs (See

Figure 1).

From

Figure 1, competing interests, the lack of information and the low technical competence are considered as potential barriers to EEMs. Moreover, energy audits could potentially enhance EEMs within firms and could dampen the negative effect of the aforementioned internal barriers on EEMs.

2.1. Internal Barriers to Energy Efficiency

The existing literature posits the existence of an untapped energy efficiency potential (Kalantzis and Revoltella, 2019), this potential is referred to as the energy efficiency gap (Koirala and Bohara, 2021). The energy efficiency gap is the difference between the theoretical energy efficiency potential and the current energy efficiency level (Dunlop, 2019).

The energy efficiency gap is attributed to the existence of energy efficiency barriers (Gerarden et al., 2015). Energy efficiency barriers could be internal (within firms) and external (with respect to firms) (Cagno et al., 2013). Internal barriers to energy efficiency are associated with internal competence and individual behaviors, while external barriers are linked to institutional and regulatory framework (Cattaneo, 2019).

Internal barriers arise from the lack of managerial competence and awareness, and a lack of management commitment to energy efficiency issues, but also from irrational behaviors and individual preferences within firms (Schleich et al., 2016; Cattenao, 2019).

Several energy efficiency barriers arise from firms, such as competing interests within firms and other priorities (Jalo et al., 2021a), the lack of information regarding energy efficiency technologies (Vakili et al., 2022), and the low technical competence within firms (Jalo et al., 2021b).

2.1.1. Competing interests

Competing priorities or competing interests or conflict of interests is undoubtedly a considerable internal barrier to energy efficiency within the industrial sector (Svensson and Paramonova, 2017; Chiaroni et al., 2017). The existence of competing priorities hinders EEMs by impeding the adoption of long-term perspectives, and by limiting firms’ ability to achieve their energy efficiency potential (Svensson and Paramonova, 2017).

In this regard, industrial firms tend to place a higher priority on production activities (Soepardi and Thollander, 2018). Industrial firms consider that the main value stream to be production, which explains the importance they attach to expanding their production capacity and increasing their market share (Soepardi and Thollander, 2018). By emphasizing on production activities, industrial firms’ management tends to neglect EEMs (Cooray, 1999).

Numerous papers have addressed how the existence competing interests within industrial firms could impede EEMs (Soepardi and Thollander, 2018; Johansson and Thollander, 2018; Lawrence et al., 2018). Therefore, hypothesis 1 is as follows:

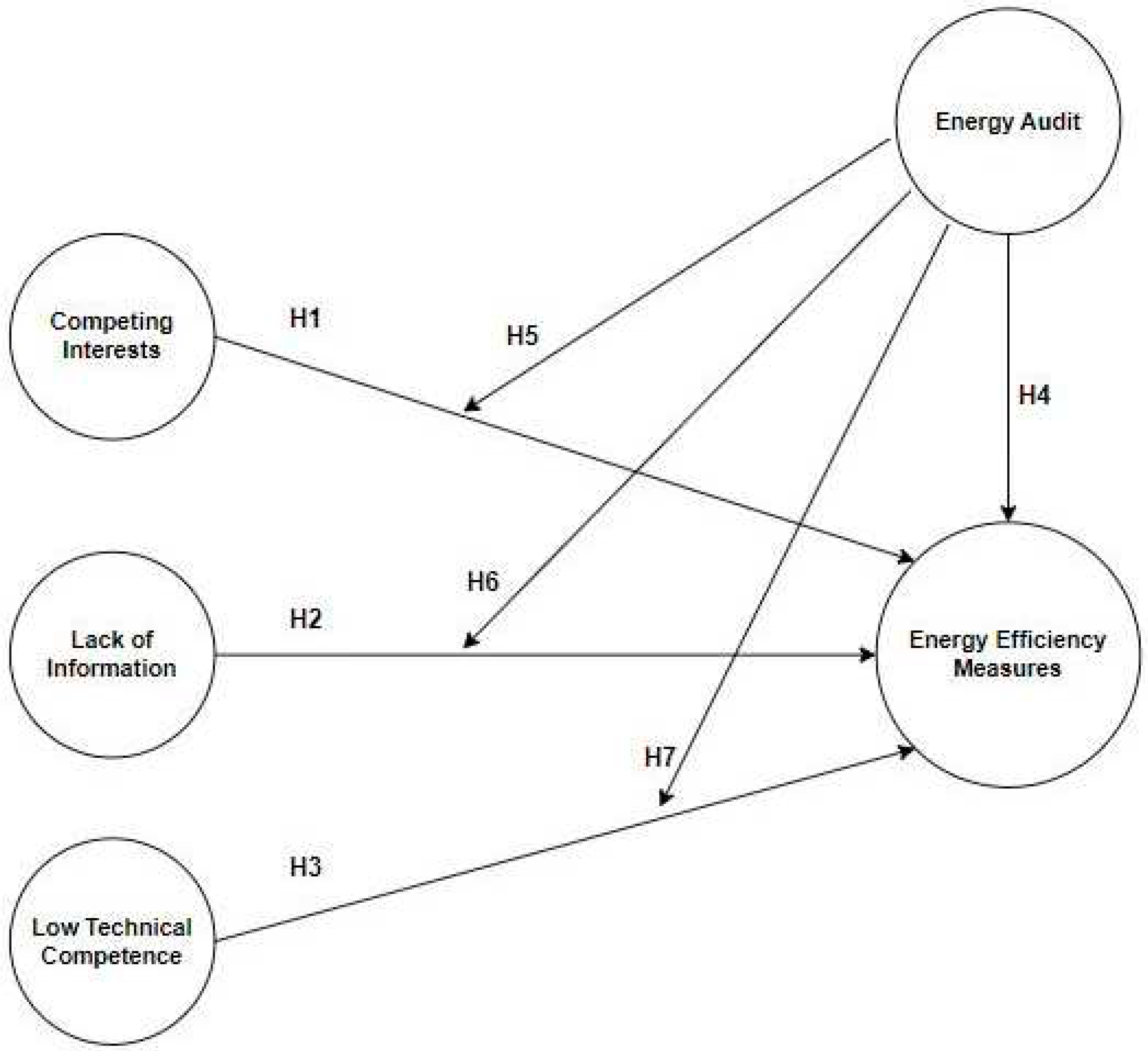

H1. The existence of competing interests has a negative effect on the adoption of EEMs.

2.1.1. Low technical competence

The technical competence and expertise are paramount to implement EEMs (Zafar, 2021). In this regard, a low technical competence within firms delays the adoption of EEMs (Hrovatin et al., 2021), and could lead to the non-implementation of EEM (Backman, 2017).

Barriers related to internal competence is materialized by inefficient diagnosis related to firms’ energy needs, inefficiencies in sensing energy efficiency opportunities, difficulties regarding the integration of EEMs into the existing internal processes, and the difficulty of attracting external competent human resources (Cagno et al., 2013).

These barrier points to management lack of awareness regarding energy efficiency opportunities (Trianni et Cagno, 2012), and to inadequate management capacity (Cagno et al., 2013; Soepardi and Thollander, 2018).

Various studies have highlighted the impact of a low technical competence within firms on impeding EEMs within firms (Cagno et al., 2013; Cagno et al., 2015; Zafar, 2021). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3. The low technical competence regarding energy efficiency has a negative effect on the adoption of EEMs.

2.2. Energy Audit

Energy audits are processes by which an auditor evaluates how facilities use different forms of energy, examines opportunities, and determines different routes for energy savings and areas for energy efficiency (Thumann and Younger, 2008). Energy audits do not result in energy savings (Paramonova and Thollander, 2016), but rather constitute a first step toward unlocking the untapped energy efficiency potential (Schleich, 2004; Backlund and Thollander, 2012). Thus, energy audits are great tools to incite firms to invest in energy-efficiency projects (Kalantzis and Revoltella, 2019).

Few studies found that energy audits might deter audit recipients to invest in energy efficiency when the perceived break-even point is reached only after a long period of time (Murphy, 2014; Barbetta et al., 2015). However, a vast body of the existing literature has shown that energy audits are critical to improve industrial firms’ energy management (Moya et al., 2016; Petek et al., 2016; Schleich and Fleiter, 2019; Kalantzis and Revoltella, 2019).

We believe that energy audits promote EEMs within industrial firms. Therefore, we have the following hypothesis:

H4. Energy audits have a positive effect on the adoption of EEMs.

Energy audits reduce the intensity of energy efficiency barriers (Schleich, 2004; Jalo et al., 2021b). Energy audits could overcome competing interests and the low priority given to energy issues within firms by increasing employees’ involvement (Chiaroni et al., 2017). Energy audits enable employees’ early commitment through the multiple cross functional meetings (Chiaroni et al., 2017). Thus, we believe that energy audits reduce the negative effect of firms’ competing priorities regarding the adoption of EEMs.

H5. Energy audits dampen the negative effect of competing interests on the adoption of EEMs.

Conducting energy audits is considered as an important tool to decrease the intensity of energy efficiency barriers, including the lack of information regarding energy efficiency opportunities (Schleich, 2004; Kalantzis and Revoltella, 2019). Therefore, we have the following hypothesis:

H6. Energy audits dampen the negative effect of the lack of information on the adoption of EEMs.

Energy audits could tackle internal barriers to energy efficiency, including the low technical competence within firms (Chiaroni et al., 2017). By pinpointing the various inefficiencies, installing energy management software, introducing energy KPIs, defining employees’ roles, and by setting training programs, energy audits are most likely to overcome internal barriers related to competence (Chiaroni et al., 2017). We believe that energy audits mitigate the negative effect of the low technical competence within firms regarding EEM.

H7. Energy audits dampen the negative effect of the low technical competence on the adoption of EEMs.

Figure 2 presents our research model and visualizes our seven research hypotheses.

3. Method

3.1. Measurement Development and Data Collection

Survey studies necessitate a carefully designed questionnaire. To ensure the quality of the questionnaire, several actions were taken. The measurements of constructs were built based on previous research (Backman, 2017; Zhang et al., 2018). We used simple and concise wordings, excluding those that could be seen as offensive. Afterwards, we started the pretest phase. Then, based on respondents’ feedback, minimal refinements were made resulting in the final version of our questionnaire.

Data collection lasted four-months, from May to August 2022. Questionnaires were made available to employees in industrial firms based in four regions: “Fes-Meknes”, “Tanger-Tétouan-Al Hoceïma”, “Casablanca-Settat”, and “Rabat-Salé-Kénitra”. We selected regions comprising the main industrial cities of Morocco.

Further to the data collection, 193 usable questionnaires were obtained. Most of the respondents are employees within a variety of departments such as production, finance, etc., which are arguably capable of providing answers regarding EEMs (Zhang et al., 2018).

Our sampling is constituted from industrial firms that belong to energy intensive sectors, composed of firms that implement energy audits.

3.2. Data Analysis Method

Once the data were collected, we employed the Partial least square (PLS) technique, and the software SmartPLS 3 to test the model and the research hypotheses. PLS is convenient to assess models with latent constructs, and moderating effects (Zhang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2018).

Data analysis through PLS-SEM comprises two major steps (Lacroux, 2009). One is the measurement model and the other one is the structural model. The measurement model examines the connection between variables/latent constructs and their corresponding items/measures. The structural model examines the connection among the various variables/latent constructs.

In our research, SmartPLS allowed us to assess the connection between our five latent variables and their observed indicators/measures. In addition, SmartPLS allowed us to analyze the direct effects, which refer to the effects of the independent variables, namely competing interests, the lack of information, the low technical competence, and energy audits, on the dependent variable which is EEMs. Furthermore, SmartPLS allowed us to analyze indirect moderating effects, which refer to the effect of energy audits on the relationship between the aforementioned internal barriers and the adoption of EEMs.

6. Conclusions and Implications:

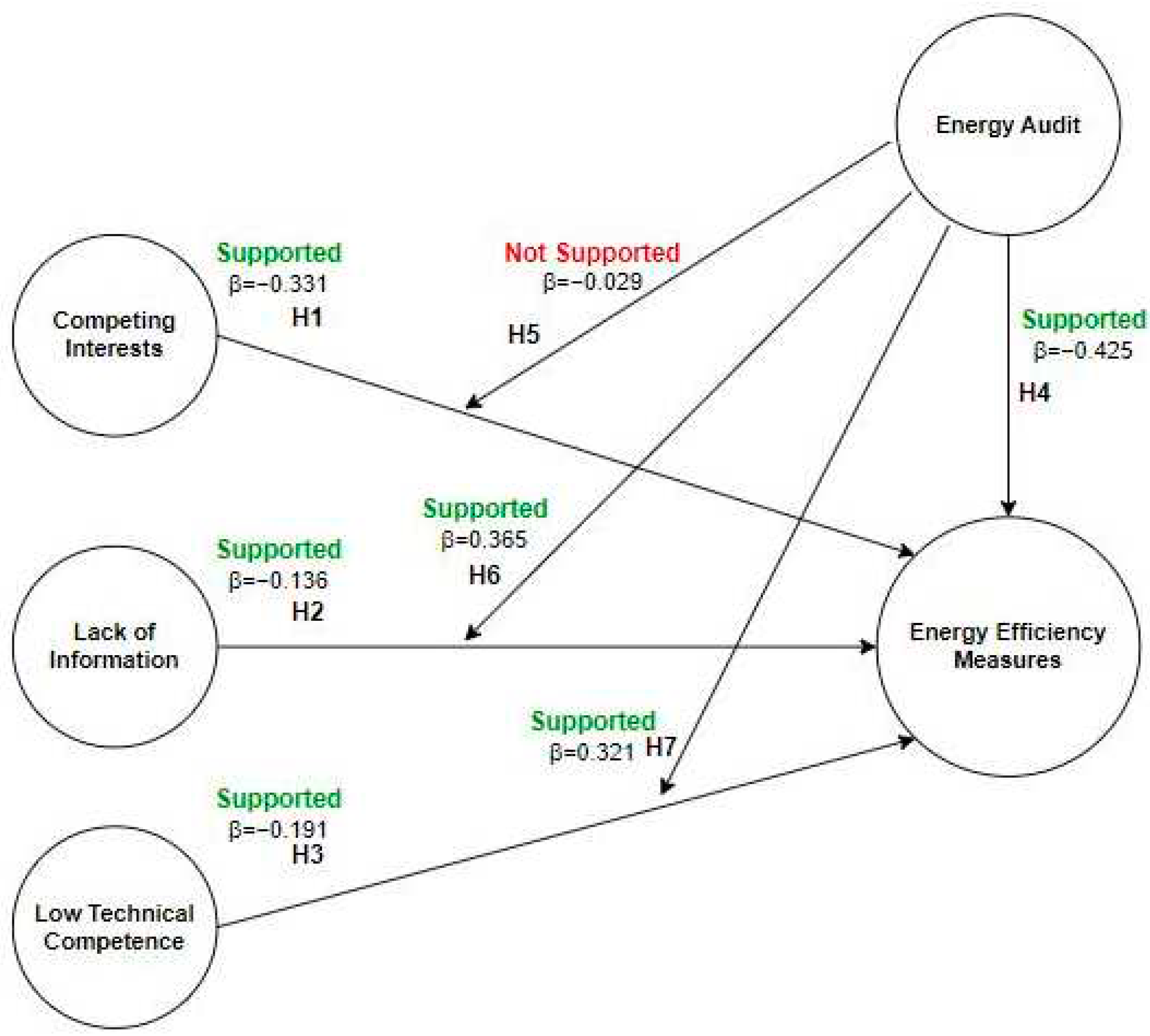

In this research, we built a research model with the aim of determining the effect of energy audits on reducing the intensity of internal barriers to energy efficiency, namely competing interests, the lack of information regarding energy issues and opportunities, and the low technical competence. We collected data from 193 industrial firms in four Moroccan regions. We analyzed the collected data via the software SmartPLS 3, then we tested our hypotheses. The following findings were obtained:

- -

Competing interests, the lack of information regarding energy issues and opportunities, and the lack of technical competence hinder the adoption of EEMs.

- -

Energy audits lead to the implementation of EEMs.

- -

Energy audits mitigate the negative effect of the lack of information and the low technical competence regarding the adoption of EEMs.

- -

Energy audits do not attenuate the negative effect of competing interests regarding the adoption of EEMs.

Based on our results, our research has theorical and policy implications.

Theorical implications: Our research reinforces previous studies with additional confirmation regarding the importance of energy audits as a factor that reduces the intensity of internal barriers to energy efficiency. Furthermore, our research invalidates the fact that energy audits reduce the intensity of competing interest within firms regarding the adoption of EEMs. In this regard, our study extends prior research.

Policy implications: Because of the importance of energy audits in tackling internal barriers to energy efficiency, policy makers could do the following: First, provide financial support for firms to implement energy audits (Schubert et al., 2021). Second, provide other supporting measures, such as training programs and certifications for energy auditors (Shen et al., 2012). Third, promote energy audits among firms using information tools, namely energy efficiency networks (Kalantzis and Revoltella, 2019). Energy efficiency networks facilitate an early involvement of all pertinent stakeholders related to EEMs, including local administrations, ESCOs and financial institutions (Kalantzis and Revoltella, 2019).