Submitted:

20 May 2023

Posted:

23 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

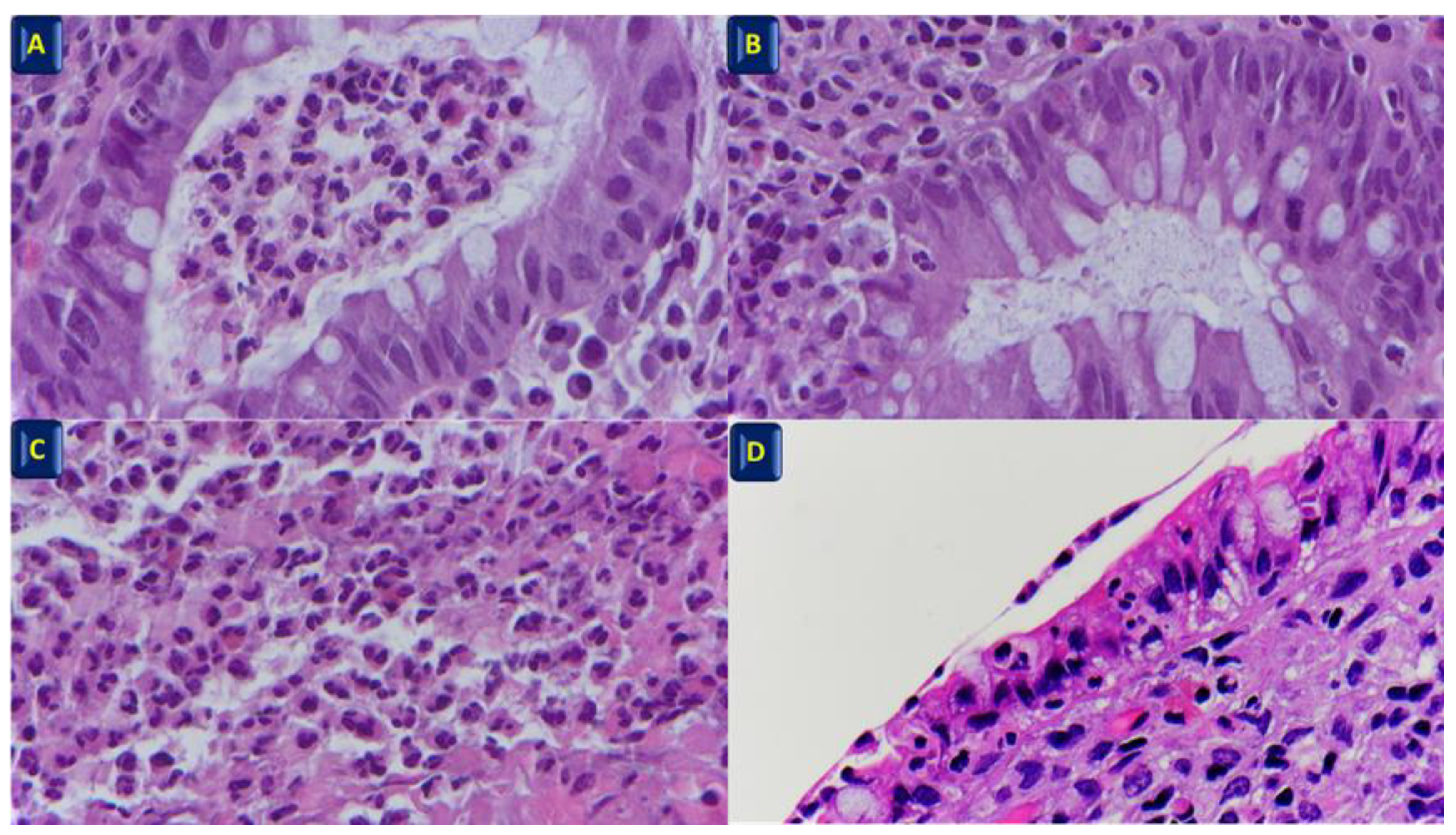

2. Histopathological features of IBD

3. Histological Mucosal Healing

- disappearance of neutrophil infiltration in the lamina propria;

- reduction of plasma cell infiltration (to normal values) and disappearance of basal plasmacytosis;

- reduction of eosinophil infiltration (to normal values).

4. Histological scores in IBD

4.1. Geboes Score

4.2. Nancy Histological Index

4.3. Robarts Histological Index

5. Simplified Histological Mucosal Healing Scheme (SHMHS)

6. Future directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bryant, R.V.; Burger, D.C.; Delo, J.; Walsh, A.J.; Thomas, S.; von Herbay, A.; Buchel, O.C.; White, L.; Brain, O.; Keshav, S.; Warren, B.F.; Travis, S.P. Beyond endoscopic mucosal healing in UC: histological remission better predicts corticosteroid use and hospitalisation over 6 years of follow-up. Gut 2016, 65, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neurath, Markus, F.; Travis, Simon P. L. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Gut 2012, 61, 1619–1935. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samaan, M.A.; Mosli, M.H.; Sandborn, W.J.; Feagan, B.G.; DʼHaens, G.R.; Dubcenco, E., Baker, K.A.; Levesque, B.G. A systematic review of the measurement of endoscopic healing in ulcerative colitis clinical trials: recommendations and implications for future research. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 1465–1471. [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, K.W.; Tremaine, W.J.; Ilstrup, D.M. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987, 317, 1625–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travis, S.P.; Higgins, P.D.; Orchard, T.; Van Der Woude, C.J.; , Panaccione; Bitton, A., O'Morain, C.; Panés, J.; Sturm,A.; Reinisch, W.; Kamm, M.A.; D'Haens, G. Review article: defining remission in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011, 34, 113–124. [CrossRef]

- Colombel, J.F.; Rutgeerts, P.; Reinisch, W.; Esser, D;, Wang, Y.; Lang, Y.; Marano, C.W.; Strauss, R.; Oddens, B.J.; Feagan, B.G.; Hanauer, S.B.; Lichtenstein, G.R.; Present, D.; Sands, B.E.; Sandborn, W.J. Early mucosal healing with infliximab is associated with improved long-term clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1194–1201. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.C; Colombel, J.F; Sands, B.E.; Narula, N. Mucosal Healing Is Associated With Improved Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016, 14, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardizzone, S.; Cassinotti, A.; Duca, P.; Mazzali, C.; Penati, C.; Manes, G.; Marmo, R.; Massari, A.; Molteni, P.; Maconi, G.; Porro, G.B. Mucosal healing predicts late outcomes after the first course of corticosteroids for newly diagnosed ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011, 9, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frøslie, K.F; Jahnsen, J.; Moum, B.A; Vatn, M.H.; IBSEN Group. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology 2007, 133, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, S.A.; Mani, V.; Goodman, M.J.; Dutt, S.; Herd, M.E. Microscopic activity in ulcerative colitis: what does it mean? Gut 1991, 32, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosli, M.H.; Feagan, B.G.; Sandborn, W.J.; Dʼhaens, G.; Behling, C.; Kaplan, K.; Driman, D.K.; Shackelton, L.M.; Baker, K.A.; Macdonald, J.K.; Vandervoort, M.K.; Geboes, K.; Levesque, B-G. Histologic evaluation of ulcerative colitis: a systematic review of disease activity indices. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 564–575. [CrossRef]

- Pai, R.K.; Jairath, V.; Vande Casteele, N.; Rieder, F.; Parker, C.E.; Lauwers, G.Y. The emerging role of histologic disease activity assessment in ulcerative colitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018, 88, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truelove, S.C.; Richards, W.C. Biopsy studies in ulcerative colitis. Br Med J. 1956, 1(4979), 1315–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Yu, A.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Treat to Target: The Role of Histologic Healing in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021, 19, 1800–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.B.; Harpaz, N.; Itzkowitz, S.; Hossain, S.; Matula, S.; Kornbluth, A.; Bodian, C.; Ullman, T. Histologic inflammation is a risk factor for progression to colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology 2007, 133, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drug Admistration. Ulcerative colitis: Clinical Trial Endpoints Guidance for Industry. Draft guidance. Silver Spring, MD: FDA, 2016; 19.

- Bryant, R.V.; Winer, S.; Travis, S.P.; Riddell, R.H. Systematic review: histological remission in inflammatory bowel disease. Is 'complete' remission the new treatment paradigm? An IOIBD initiative. J Crohns Colitis 2014, 8, 1582–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, B.; Erlich, J.; Gibson, P.R.; Turner, J.R.; Hart, J.; Rubin, D.T. Histologic Healing Is More Strongly Associated with Clinical Outcomes in Ileal Crohn's Disease than Endoscopic Healing. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020, 18, 2518–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanacci, V.; Reggiani-Bonetti, L.; Salviato, T.; Leoncini, G.; Cadei, M.; Albarello, L.; Caputo, A.; Aquilano, M.C.; Battista, S.; Parente, P. Histopathology of IBD Colitis. A practical approach from the pathologists of the Italian Group for the study of the gastrointestinal tract (GIPAD). Pathologica 2021, 113, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavese, G.; Villanacci, V.; Antonelli, E,.; Cadei, M.; Sapino, A.; Rocca, R.; Daperno, M.; Suriani, R.; Di Santo, M.G.; Cassoni, P.; Bernardini, N.; Bassotti, G. Eosinophilia - associated basal plasmacytosis: an early and sensitive histologic feature of inflammatory bowel disease. APMIS 2017, 125, 179–183. [CrossRef]

- Zezos, P.; Patsiaoura, K.; Nakos, A.; Mpoumponaris, A.; Vassiliadis, T.; Giouleme, O.; Pitiakoudis, M.; Kouklakis, G.; Evgenidis, N. Severe eosinophilic infiltration in colonic biopsies predicts patients with ulcerative colitis not responding to medical therapy. Colorectal Dis. 2014, 16, O420–O430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoncini, G.; Villanacci, V.; Marin, M.G.; Crisafulli, V.; Cadei, M.; Antonelli, E.; Leoci, C.; Bassotti, G. Colonic hypereosinophilia in ulcerative colitis may help to predict the failure of steroid therapy. Tech Coloproctol. 2018, 22, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langner, C.; Magro, F.; Driessen, A.; Ensari, A.; Mantzaris, G.J.; Villanacci, V.; Becheanu, G.; Borralho Nunes, P.; Cathomas, G.; Fries, W.; Jouret-Mourin, A.; Mescoli, C.; de Petris, G.; Rubio, C.A.; Shepherd, N.A.; Vieth, M,.;Eliakim, R.; Geboes, K.; European Society of Pathology; European Crohn's and Colitis Foundation. The histopathological approach to inflammatory bowel disease: a practice guide. Virchows Arch. 2014, 464, 511–527. [CrossRef]

- Yantiss, R.K.; Odze, R.D. Diagnostic difficulties in inflammatory bowel disease pathology. Histopathology 2006, 48, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, C.N.; Shanahan, F.; Anton, P.A.; Weinstein, W.M. Patchiness of mucosal inflammation in treated ulcerative colitis: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995, 42, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankey, E.A.; Dhillon, A.P,.; Anthony, A.; Wakefield ,A.J.; Sim, R.; More, L.; Hudson, M.; Sawyerr, A.M., Pounder, R.E. Early mucosal changes in Crohn's disease. Gut 1993, 34, 375–381. [CrossRef]

- Villanacci, V.; Bassotti, G. Histopathological findings of extra-ileal manifestations at initial diagnosis of Crohn's disease-related ileitis. Virchows Arch. 2017, 470, 595–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.; Ricciuto, A.; Lewis, A.; D'Amico, F.; Dhaliwal, J.; Griffiths, A.M.; Bettenworth, D.; Sandborn, W.J.; Sands, B.E.; Reinisch, W.; Schölmerich, J.; Bemelman, W.; Danese, S.; Mary, J.Y.; Rubin, D.; Colombel, J.F.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Dotan, I.; Abreu, M.T.; Dignass, A. International Organization for the Study of IBD.STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1570–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magro, F.; Langner, C.; Driessen, A.; Ensari, A:, Geboes, K.; Mantzaris, G.J.; Villanacci, V.; Becheanu, G.; Borralho Nunes, P.; Cathomas, G.; Fries, W.; Jouret-Mourin, A.; Mescoli, C.; de Petris, G.; Rubio, C.A.; Shepherd, N.A.; Vieth, M.; Eliakim, R.; European Society of Pathology (ESP); European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO). European consensus on the histopathology of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn’s Colitis 2013, 7, 827–851. [CrossRef]

- Stange, E.F.,Travis, S.P.; Vermeire, S.; Reinisch, W.; Geboes, K.; Barakauskiene, A.; Feakins, R.; Fléjou, J.F.; Herfarth, H.; Hommes, D.W.;Kupcinskas, L.; Lakatos, P.L.; Mantzaris, G.J.; Schreiber, S.; Villanacci, V.; Warren, B.F.; European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO). European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis: Definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis 2008, 2, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Villanacci, V.; Antonelli, E.; Reboldi, G.; Salemme, M.; Casella, G.; Bassotti, G. Endoscopic biopsy samples of naïve "colitides" patients: role of basal plasmacytosis. J Crohns Colitis 2014, 8, 1438–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessissow, T.; Lemmens, B.; Ferrante, M.; Bisschops, R.; Van Steen, K.; Geboes, K.; Van Assche, G.; Vermeire, S.; Rutgeerts, P.; De Hertogh, G. Prognostic value of serologic and histologic markers on clinical relapse in ulcerative colitis patients with mucosal healing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012, 107, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pai, R.K.; Geboes, K. Disease activity and mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: a new role for histopathology? Virchows Arch. 2018, 472, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkas, K.; Reisz, Z.; Sejben, A.; Tiszlavicz, L.; Szűcs, M.; Nyári, T.; Szepes, Z.; Nagy, F.; Rutka, M.; Balint, A.; Bor, R.; Milassin, Á.; Molnàr, T. Histological activity and basal plasmacytosis are nonpredictive markers for subsequent relapse in ulcerative colitis patients with mucosal healing. J Gastroenterol Pancreatol Liver Disord 2016, 3, 01–04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, S.; Riddell, R.H. The role of eosinophils in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2005, 54, 54,1674–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vande Casteele, N.; Leighton, J.A.; Pasha, S.F.; Cusimano, F.; Mookhoek, A.; Hagen, C.E.; Rosty, C.; Pai, R.K.; Pai, R.K. Utilizing Deep Learning to Analyze Whole Slide Images of Colonic Biopsies for Associations Between Eosinophil Density and Clinicopathologic Features in Active Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022, 28, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magro, F.; Doherty, G.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Svrcek, M.; Borralho, P.; Walsh, A.; Carneiro, F.; Rosini, F.; de Hertogh, G.; Biedermann, L.; Pouillon, L.; Scharl, M.; Tripathi, M.; Danese, S.; Villanacci, V.; Feakins, R. ECCO Position Paper: Harmonization of the Approach to Ulcerative Colitis Histopathology. J Crohns Colitis 2020, 14, 1503–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, M.F.; Genta, R.M.; Yardley, J.H.; Correa, P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol 1996, 20, 1161–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanacci, V.; Bassotti, G.; Langner, C. Histological remission in inflammatory bowel disease: where are we, and where are we going? J Crohns Colitis 2015, 9, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magro, F.; Sabino, J.; Rosini, F.; Tripathi, M.; Borralho, P.; Baldin, P.; Danese, S.; Driessen, A; Gordon, I.O.; Iacucci, M.; Noor, N.; Svrcek, M.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Feakins, R. ECCO Position on Harmonisation of Crohn's Disease Mucosal Histopathology. J Crohns Colitis 2022, 16, 876–883. [CrossRef]

- Mosli, M.H.; Parker, C.E.; Nelson, S.A.; Baker, K.A.; MacDonald, J.K.; Zou, G.Y.; Feagan, B.G.; Khanna, R.; Levesque, B.G.; Jairath, V. Histologic scoring indices for evaluation of disease activity in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017, 5, CD011256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, G.; Parker, C.E.; Pai, R.K.; MacDonald, J.K.; Feagan, B.G.; Sandborn, W.J.; D'Haens, G.; Jairath, V.; Khanna, R. Histologic scoring indices for evaluation of disease activity in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017, 7, CD012351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Römkens, T.E.H.; Kranenburg, P.; Tilburg, A.V.; Bronkhorst, C.; Nagtegaal, I.D.; Drenth, J.P.H.; Hoentjen, F. Assessment of Histological Remission in Ulcerative Colitis: Discrepancies Between Daily Practice and Expert Opinion. J Crohns Colitis 2018, 12, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magro, F.; Lopes, J.; Borralho, P.; Dias, C.C.; Afonso, J.; Ministro, P.; Santiago, M.; Geboes, K.; Carneiro, F.; Portuguese IBD Study Group [GEDII]. Comparison of the Nancy Index With Continuous Geboes Score: Histological Remission and Response in Ulcerative Colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2020, 14, 1021–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marion, L.; Amélie, B.; Zoubir, D.; Guillaume, C.; Elise, M.S.; Hedia, B.; Margaux, L.S.; Aude, M.; Camille, B.R. Histological Indices and Risk of Recurrence in Crohn's Disease: A Retrospective Study of a Cohort of Patients in Endoscopic Remission. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022, 28, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanacci, V.; Antonelli, E.; Lanzarotto, F.; Bozzola, A.; Cadei, M.; Bassotti, G. Usefulness of Different Pathological Scores to Assess Healing of the Mucosa in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Real Life Study. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 6839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geboes, K.; Riddell, R.; Ost, A.; Jensfelt, B.; Persson, T.; Löfberg, R. A reproducible grading scale for histological assessment of inflammation in ulcerative colitis. Gut 2000, 47, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauregui-Amezaga, A.; Geerits, A.; Das, Y.; Lemmens, B.; Sagaert, X.; Bessissow, T.; Lobatón, T.; Ferrante, M.; Van Assche, G.; Bisschops, R.; Geboes, K.; De Hertogh, G.; Vermeire, S. A Simplified Geboes Score for Ulcerative Colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2017, 11, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchal-Bressenot, A.; Salleron, J.; Boulagnon-Rombi, C.; Bastien, C.; Cahn, V.; Cadiot, G.; Diebold, M.D.; Danese, S.; Reinisch, W.; Schreiber, S.; Travis, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Development and validation of the Nancy histological index for UC. Gut 2017, 66, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosli, M.H.; Feagan, B.G.; Zou, G., Sandborn, W.J.; D'Haens, G.; Khanna, R.; Shackelton, L.M.; Walker, C.W.; Nelson, S.; Vandervoort, M.K.; Frisbie, V.; Samaan, M.A.; Jairath, V.; Driman, D.K.; Geboes, K.; Valasek, M.A.; Pai, R.K.; Lauwers, G.Y.; Riddell, R.; Stitt, L.W.; Levesque, B.G. Development and validation of a histological index for UC. Gut 2017, 66, 50–58. [CrossRef]

- Magro, F.; Lopes, J.; Borralho, P.; Lopes, S.; Coelho, R.; Cotter, J.; Dias de Castro, F.; Tavares de Sousa, H.; Salgado, M.; Andrade, P.; Vieira, A.I.; Figueiredo, P.; Caldeira, P.; Sousa, A.; Duarte, M.A.; Ávila, F.; Silva, J.; Moleiro, J., Mendes, S.; Giestas, S.; Ministro, P.; Sousa, P.; Gonçalves, R.; Gonçalves, B.; Oliveira, A.; Chagas, C.; Cravo, M:, Dias, C.C.; Afonso, J.; Portela, F.; Santiago, M.; Geboes, K.; Carneiro, F. Comparing the Continuous Geboes Score With the Robarts Histopathology Index: Definitions of Histological Remission and Response and their Relation to Faecal Calprotectin Levels. J Crohns Colitis 2020, 14, 169–175. [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A.; Parente, P.; Cadei, M.; Fassan, M.; Rispo, A.; Leoncini, G.; Bassotti, G.; Del Sordo, R.; Metelli, C.; Daperno, M.; Armuzzi, A.; Villanacci, V.; SHMHS Study Group. Correction to: Simplified Histologic Mucosal Healing Scheme (SHMHS) for inflammatory bowel disease: a nationwide multicenter study of performance and applicability. Tech Coloproctol. 2023, 27, 167–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, X.; Bazarova, A.; Del Amor, R.; Vieth, M.; de Hertogh, G.; Villanacci, V.; Zardo, D.; Parigi, T.L.; Røyset, E.S.; Shivaji, U.N.; Monica, M.A.T.; Mandelli, G.; Bhandari, P.; Danese, S.; Ferraz, J.G.; Hayee, B.; Lazarev, M.; Parra-Blanco, A.; Pastorelli, L.; Panaccione, R.; Rath, T.; Tontini, G.E., Kiesslich, R.; Bisschops, R.; Grisan, E.; Naranjo, V.; Ghosh, S.; Iacucci, M. PICaSSO Histologic Remission Index (PHRI) in ulcerative colitis: development of a novel simplified histological score for monitoring mucosal healing and predicting clinical outcomes and its applicability in an artificial intelligence system. Gut 2022, 71, 889–898. [CrossRef]

- Iacucci, M.; Parigi, T.L.; Del Amor, R.; Meseguer, P.; Mandelli, G.; Bozzola, A.; Bazarova, A.; Bhandari, P.; Bisschops, R.; Danese, S., De Hertogh, G:, Ferraz, J.G.; Goetz, M.; Grisan, E.; Gui, X.; Hayee, B.; Kiesslich, R.; Lazarev, M.; Panaccione, R.; Parra-Blanco, A.; Pastorelli, L.; Rath, T.; Røyset, E.S.; Tontini, G.E.; Vieth, M.; Zardo, D.; Ghosh, S.; Naranjo, V.; Villanacci, V. Artificial Intelligence Enabled Histological Prediction of Remission or Activity and Clinical Outcomes in Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology 2023, S0016-5085(23)00216-0. [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, S.; Krieghoff-Henning, E.; Kather, J.N.; Jutzi, T.; Höhn, J.; Kiehl, L.; Hekler, A.; Alwers, E.; von Kalle, C.; Fröhling, S.; Utikal, J.S.; Brenner, H.; Hoffmeister, M.; Brinker, T.J. Gastrointestinal cancer classification and prognostication from histology using deep learning: Systematic review. Eur J Cancer 2021, 155, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leoncini, G.;Gentili, M.; Lusenti, E.; Caruso, L.; Calafà, C.; Migliorati, G ; Riccardi, C. ;Villanacci, V.; Ronchetti, S. The novel role of glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper as a marker of mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases. Pharmacol Res 2022, 182, 106353. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cari, L.; Rosati, L.; Leoncini, G.; Lusenti, E.; Gentili, M.; Nocentini, G.; Riccardi, C.; Migliorati, G.; Ronchetti, S. Association of GILZ with MUC2, TLR2, and TLR4 in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronchetti, S.; Ricci, E.; Migliorati, G.; Gentili, M.; Riccardi, C. How Glucocorticoids Affect the Neutrophil Life. Int J Mol Sci. 2018, 19, 4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, E.; Ronchetti, S.; Gabrielli, E.; Pericolini, E.; Gentili, M.; Roselletti, E.; Vecchiarelli, A.; Riccardi, C. GILZ restrains neutrophil activation by inhibiting the MAPK pathway. J Leukoc Biol. 2019, 105, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentili, M.; Hidalgo-Garcia, L.; Vezza, T.; Ricci, E.; Migliorati, G.; Rodriguez-Nogales, A., Riccardi, C.; Galvez, J.; Ronchetti, S. A recombinant glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper protein ameliorates symptoms of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis by improving intestinal permeability. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21950. [CrossRef]

| Simplified Geboes Score | Nancy Score | Robarts Score | SHMHS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 0: No inflammatory activity |

0.0 No abnormalities 0.1 Presence of architectural changes 0.2 Presence of architectural changes and chronic mononuclear infiltrate |

Chronic inflammatory infiltrate (quantity of lymphocytes and plasmacytes in the biopsy) | 0 No increase 1 Mild but unequivocal increase 2 Moderate increase 3 Marked increase |

Chronic inflammatory infiltrate | 0 No increase 1 Mild but unequivocal increase 2 Moderate increase 3 Marked increase |

Part I. Features | ||

| Neutrophils in lamina propria | 1 Present 0 Absent |

|||||||

| Cryptitis or crypt abscesses (presence of neutrophils) | 1 Present 0 Absent |

|||||||

| Grade 1: Basal plasma cells |

1.0 No increase 1.1.Mild increase 1.2 Marked increase |

Neutrophils in the epithelium | 0 None 1<50% crypt involved 2>50% crypt involved |

Lamina propria neutrophils | 0 None 1 Mild but unequivocal increase 2 Moderate increase 3 Marked increase |

Erosions or ulcerations (presence of granulation tissue) | 1 Present 0 Absent |

|

| Grade 2A: Eosinophils in lamina propria | 2A.0 No increase 2A.1 Mild increase 2A.2 Marked increase |

Ulceration (visible epithelial injury, regeneration, fibrin,tissue granulation) | 0 Absent 1 Present |

Part II. Site of involvement | ||||

| Neutrophils in the epithelium | 0 None 1<5% crypts involved 2<50% crypts involved 3>50% crypts involved |

Ileum (CD patient only) | 1 Active 0 Quiescent 0 Not involved |

|||||

| Grade 2B: Neutrophils in lamina propria | 2B.0 No increase 2B.1 Mild increase 2B.2 Marked increase |

Acute inflammatory cell infiltrate | 0 None 1 Mild 2 Moderate 3 Severe |

Right colon | 1 Active 0 Quiescent 0 Not involved |

|||

| Erosion or ulceration | 0 No erosion, ulceration or granulation tissue 1 Recovering epithelium+ adjacent inflammation 1 Probable erosion-focally stripped 2 Unequivocal erosion 3 Ulcer or granulation tissue |

|||||||

| Grade 3: Neutrophils in epithelium | 3.0 None 3.1<50% crypts involved 3.2>50% crypts involved |

Mucin depletion | 0 None 1 Mild 2 Moderate 3 Severe |

Trasverse colon | 1 Active 0 Quiescent 0 Not involved |

|||

| Grade 4: Epithelial injury (in crypt and surface epithelium) | 4.0 None 4.1 Marked attenuation 4.2 Probable crypt destruction: probable erosions 4.3 Unequivocal crypt destruction: unequivocal erosions 4.4 Ulcer or granulation tissue |

Neutrophils in lamina propria | 0 None 1 Mild 2 Moderate 3 Severe |

Descending Colon | 1 Active 0 Quiescent 0 Not involved |

|||

| Sigmoid colon and rectum | 1 Active 0 Quiescent 0 Not involved |

|||||||

| Basal plasmacytosis | 0 None 1 Mild 2 Moderate 3 Severe |

|||||||

| Serrated architectural (defined as the presence of dilated crypts showing a scalloped lumen) | 0 None 1<5% crypt involved 2<50% crypt involved 3 >50% crypt involved |

|||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).