1. Introduction

Technology poses a significant threat to the banking and regulatory systems (Clarke,2021; Anagnostopoulos, 2018). The rapid pace of technology changes has left regulators with a huge task of developing adequate regulatory responses, even though they may not understand it (Ofoeda, 2022; Groepe, 2017). Most of the current banking regulations apply to the traditional banking model. However, in the digital innovation era, regulators still require banks to apply the same risk management practices to the current digital banking practices. Failure to apply culminates into non-compliance. Fintech is still emerging, evolving, and disrupting the financial services industry (Nejad, 2022; Anagnostopoulos, 2018; Dong, 2017; Brummer, 2015). Based on the old regulations, banks are still expected to have sound AML practices. This is detrimental. The global AML/CFT regulatory framework is anchored on the FATF’s 40 recommendations. FATF collaborates with other international organisations in the sharing and dissemination of AML/CFT associated information.

Money launderers prefer to use financial services as the ideal medium to launder. Accordingly, FATF designed recommendations 1 to 40 on which country AML/CFT regulations are based and benchmarked. FATF recommendations are universally acceptable guiding standards in the regulatory design to counter money laundering and the risks of financing terrorism. Post global financial crisis, financial regulations continue to be modified and reviewed with the aim of combatting money laundering, protecting consumers and ensuring integrity in the financial system. As such, this paper aims to provide an overview of the global AML/CFT regulations, application and how they should evolve in this dynamic environment.

This paper is organised into 6 sections.

Section 1 is the introduction with

Section 2 providing an overview of money laundering.

Section 3 discusses the research approach adopted.

Section 4 outlines FATF recommendations, country implementation and regulatory enforcements.

Section 5 outlines the critique concerning the current AML/CFT regulatory framework and lastly

Section 6 being the conclusion.

2. Overview of Money Laundering

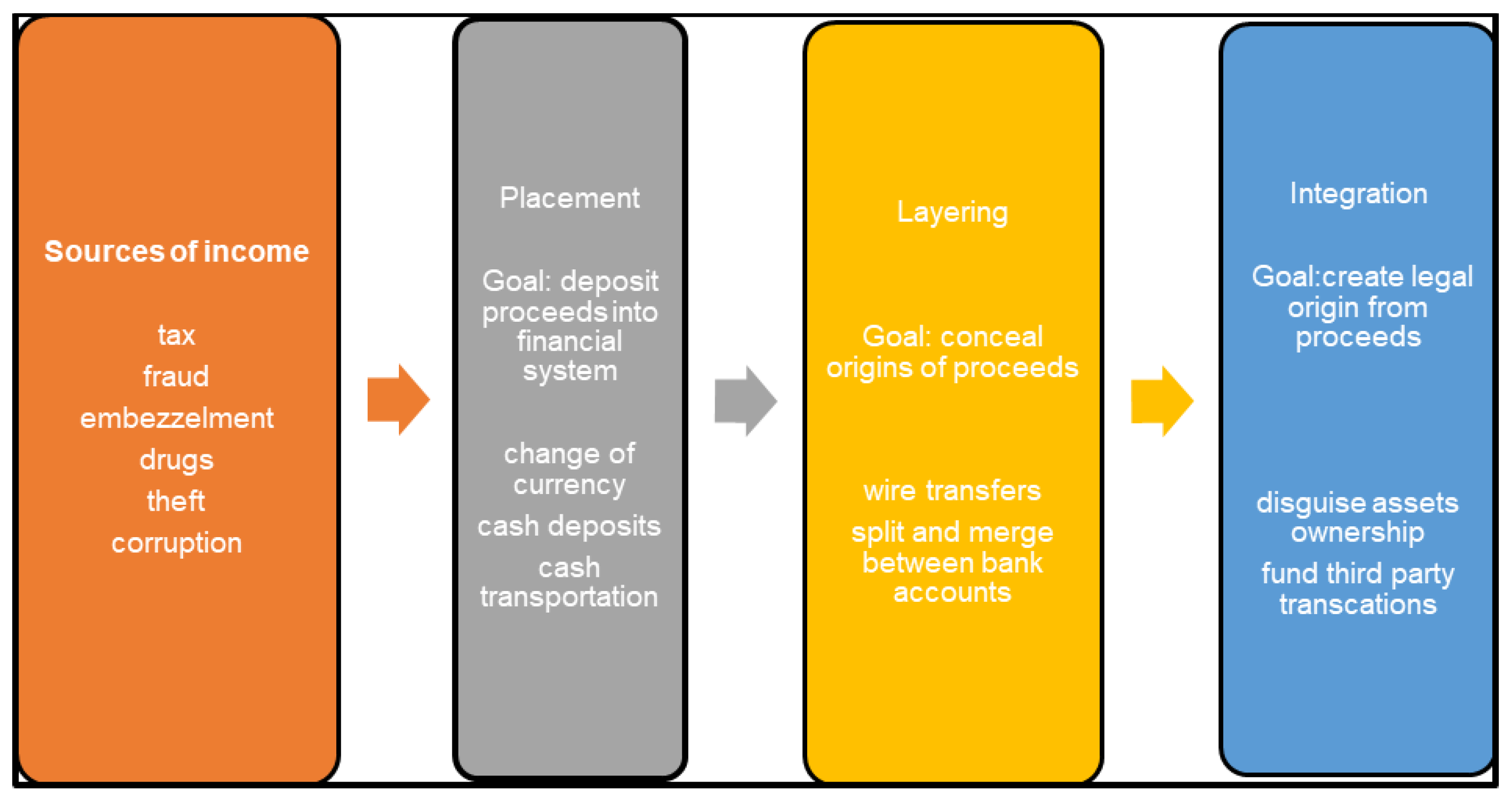

Economic players are rewarded for using factors of production (Littrell, 2022; Myohr & Fourie, 2008; Masciandaro, 1999). Rewards can be earned legally or illegally but still need to be accounted for under the economic performance statistics. However, illegally earned funds remain difficult to account for due to falsification of income sources (Clarke, 2021; Sotande, 2018; Arnone & Borlini, 2010). The sources of dirty money include (among others) corruption, fraud, tax evasion, theft, and bribery. Historically, money laundering goes through three stages. These are placement, layering and integration. However, with the digital innovations, money laundering can occur at any of these three stages. Each stage has associated activities, which are shown in

Figure 1. Typical money laundering activities under each stage are illustrated in the schematic map below.

2.1. Placement Stage

This is the first stage through which dirty money is infused into the formal banking channels in various forms (Clarke, 2021; Whisker & Lokanan, 2019; Papanicolaou, 2015). The aim at this stage is to place illegal money into the legitimate banking system and relieve the launderer of holding large amounts of money. Methods used at the placement stage include smurfing; deposits using fake identity documents; refining; cash transportation, and cash rich business (Papanicolaou, 2015). These methods are discussed below:

2.1.1. Physical cash deposit and smurfing

Dumitrache and Modiga (2011) postulate that physical cash deposits and or smurfing are usually utilised by money launderers. To circumvent meeting AML/CFT cash or suspicious reporting obligations, money launderers opt for smurfing (Choo, Amirrudin, Noruddin, & Othman, 2014). The breaking down of illegally earned funds into smaller deposits which are below cash reporting thresholds is known as smurfing. Similarly, with current electronic forms of money substituting cash deposits, this stage can become so obvious to overlook within the monitoring system (Whisker & Lokanan, 2019; Dumitrache & Modiga, 2011; Filipkwoski, 2008). Maynhardt & Marx (2014) observed that huge cash deposits have been associated with cash-based economies compared to digital based economies.

At placement stage with poor AML/CFT regulatory oversight, incorrectly captured customer details create money laundering risks (Collin, 2020; Whisker and Lokanan, 2019; Suarez, 2016). These include failure to risk profile customers resulting in financial institutions failing to place appropriate mitigatory measures and being complicit in money laundering.

2.1.2. Fake identity documents and refining

Another form commonplace in money-laundering is when deposits are made using fake identity documents and names (Arnone & Borlini, 2010). This, however, exerts pressure on financial institutions and KYC principles. As part of the CDD measures, banks need to verify and authenticate submitted customer`s national identity documents (Sultan & Mohamed 2022; Arasa & Ottichilo, 2015). Verification and authentication minimize the risk of wrongly profiling the customers. Launderers can also opt for refining, which entails using high denominated values of currency for smuggling purposes (Trajkovski & Blagoja, 2019; Hopton, 2009). In the fight against higher denominations being used for money laundering purposes and cash smuggling, the European Central Bank phased out issuance of Euro 500 denominations in 2018 and replaced them with 200 and 100 denominations (European Commission, 2016). Financial institutions need to perform strict CDD procedures during onboarding and throughout the course of the financial relationship.

2.2. Layering

Under this second stage of money laundering, the money launderers disguise original sources of illegal funds by moving funds from one location to another (Moiseienko, 2022; Whisker & Lokanan, 2019; Papanicolaou, 2015). Ryder (2015) posits that layering involves avoiding an audit trail by making payments or purchases of immovable property through electronic transfers to another bank either locally or internationally. At this stage, the aim is to create less traceability suspicion to the original much as possible.

Money launderers can structure financial transactions to conceal audit trail by breaking down the original amount into smaller transactions to deceive possible investigators (Whisker & Lokanan, 2019; Cassara, 2016). Stessens (2009) posits that for the transaction to be successful at the layering stage, the money launderers need to do as many electronic banking transactions as possible. Due to technological innovations which enable instant international and local bank transfers, at this stage regulators can fail to detect and or investigate possible money laundering issues (Whisker & Lokanan, 2019; Dumitrache & Modiga, 2011). Launderers can opt to use parallel banking systems such as Hawala/Hundi and illegal international money transfers (Mniwasa, 2019a; Papanicolaou, 2015; GoT, 2010) if they are determined to cover their trails.

Characteristically, money launderers at the layering stage are not concerned with brokerage or transfer fees and investment losses (Anagnostopoulos, 2018). This shows that the only motive of money launderers at this stage is disguising the original source of funds. Another characteristic is the increased frequency of cross border transactions in the form of investments or remittances, which could be an indicator of money laundering at layering stage (Sileshi, 2022; Cassara, 2016). Thus, proper CDD measures need to be exercised on the customers during onboarding and thereafter.

2.3. Integration

According to the three-stage process, this is the final stage in which money reappears into the economy through investments (Kaur & Sandhu, 2022; Papanicolaou, 2015). The money is returned to criminals through several methods and used for other purposes. The aim is to reunite in a way that does not draw attention and appears as if the source of funds is legitimate (Whisker & Lokanan, 2019). Launderers can use complex methods to avoid suspicions such as international funds transfer, direct or offshore investments (Suntura & Harry, 2020; Al-Nuemat, 2014). At this stage, the launderers constantly move funds to elude detection and exploit legal loopholes in the country’s AML/CFT legislation.

Most money launderers have offshore accounts and make transnational investments to disguise source of funds (Sultan & Norazida, 2022; Bofondi & Gobbi, 2017; Papanicolaou, 2015). Indeed, cross border investments need to be scrutinised. However, the challenge lies in the non-cooperation or cooperation among nations (Mathuva, et al., 2020; Naheem, 2019; Araujo, 2010; Masciandaro, 1999). Cross border payments and investments pose a considerable challenge to the financial institutions and anti-money laundering efforts (Sultan & Norazida, 2022; Bank for International Settlements, 2016a). Furthermore, increased cross border investments and international funds transfer combined with poorly performed CDD procedures and anonymity at the placement stage all pose significant threats to financial sector and ultimately financial integrity (Whisker & Lokanan, 2019; Solin & Zerzan, 2010).

3. Research Approach

To gather more insights into the global AML/CFT regulations and applications, a qualitative approach was adopted. This involved undertaking a structured literature review as well document analysis through of applicable legislation, publicized AML/CFT regulatory enforcements, and related developments. Armitage & Keeble-Allen (2008) posits that structured literature review summarizes the impactful, innovative and latest developments on the subject of under study.

4. FATF Recommendations, Country implementation and Regulatory enforcement

The section discusses FATF associated issues related to the organisation structure, recommendations and implementations. Also, to be discussed is the AML/CFT regulatory enforcements.

4.1. Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Organisation Structure

Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is an organisation under the auspices of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that specialises in offering measures to combat money laundering (Koker, 2022; FATF, 2012). FATF was established in 1989 as an intergovernmental body involving over 180 countries. Its mandate is designed to set up standards and promote effective implementation of regulatory, operational, and legal measures to combat risks associated with money laundering in the international financial system (FATF, 2021; FATF, 2012-2019).

Precipitating factors gave way to the establishment of FATF. Some of these factors included failure of domestic regulations to deal with challenges of increased cross border transactions, globalisation and diaspora remittances amongst others (Sujee, 2016). Associated money laundering measures adopted at national or community levels without regional and international support have limited influence (Mniwasa, 2019b; Sujee, 2016). The coordinated approach envisaged in the international bodies helps in addressing the challenges at global level.

Coordination of FATF`s international activities is done through regional and international bodies (Jones & Knaack, 2019; Ryder, 2015; FATF, 2012). The regional bodies include the Eastern and Southern African Anti-Money Laundering Group (ESAAMLG); Asia Pacific Group (APG); CFATF for Caribbean countries; GABAC for the Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa; and GIABA for countries in Western Africa. International private sector bodies have supported and recommended the adoption of the FATF 40 recommendations to curb risks associated with money laundering (Arnone & Borlini, 2010). Among others international bodies include Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, International Monetary Fund (IMF), United Nations (UN), World Bank Wolfsburg Group, Offshore Group of Banking Supervisors, Financial Stability Forum of Offshore Financial Centres, International Organisation of Securities Commission and Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units.

FATF was mandated to develop an assessment framework for the member countries` level of compliance and implementation regards the AML/CFT regulatory framework (GIABA, 2015; FATF, 2012). Assessments are carried out by the regional bodies of FATF and shared with the countries. Effective cooperation is the panacea to resolving the AML problem. Sherman (1993:69) argues that “the fight against money laundering cannot be the sole responsibility of government and law enforcement agencies. If these activities are to be suppressed and hopefully in the long term substantially eliminated, it will require the collective will and commitment of the public and private sector working together.” Progressively, the views of Sherman (1993) have been supported by Dobrowolski & Sulkowski (2020) and Usman (2014). Thus, the worldwide AML/CFT efforts through the FATF and international partners are aimed at enhancing the resilience of financial institutions in curbing money laundering and related crimes.

4.2. FATF Recommendations

FATF, as part of its mandate, established a minimum regulatory criterion known as the forty (40) recommendations in combating money laundering and terrorist financing (Koker, 2022; Sujee, 2016). These recommendations provide regulatory floors not ceilings to be met in order to be compliant (Held, 2019). However, depending on the country`s risk appetite, they can enhance or use the 40 recommendations as basis for the country`s AML regulations. These recommendations are not internationally binding, even though most countries have made political commitment to abide by the recommendations (Sujee, 2016; FATF, 2012). Johansson, Sutinen, Lassila, Lang, Martikainen, Lehner (2019) recommend that institutions operating in an uncertain environment are largely dependent on the political economy. In the long run, this uncertainty creates problems for financial institutions (Hill, 2018).

As shown in

Table 1, the 2012 recommendations cover legal systems, measures taken to prevent ML/TF, and international cooperation. FAFT recommendations have been progressively revised from the 1990 initial recommendations to the 2012 and these still have been amended in 2020 (Dobrowolski & Sulkowski, 2020; FATF, 2012-2019). Koker (2022) concurs with De Koker & Turkington (2016) that the initial FATF recommendations were not informed by research but based on the small group of people`s expertise and their subjective perceptions. Admittedly, these recommendations are continually revised to reflect the ever-changing environment and anticipated future threats posed by money launderers.

As shown in

Table 2, the revised forty recommendations include: risk identification; AML policy and domestic coordination; preventative measures for designated institutions; establishing the powers and responsibility for competent authorities and facilitation of international cooperation. Despite the comparative differences between the initial and revised recommendations, Mathuva, et al. (2020) and Maguchu (2018) recognise that the revised recommendations address emerging threats and strengthen existing obligations. Koker (2022) argues that FATF should conduct evidence based standard setting and not rely solely on the expertise of FATF members. As part of regulatory impact assessment, this contributes to policy making (OECD,2022). The next section discusses the countries FATF 40 implementation.

4.3. Selected Countries` Implementation of FATF 40 Recommendations

FATF recommendations are universally acceptable guiding standards in the regulatory design to counter money laundering risks (FATF, 2021; Jones & Knaack, 2019; Afande, 2015; Arnone & Borlini, 2010). Furthermore, FATF conducts periodic inspections on member countries and evaluates the progress thereof (Littrell, 2022; GIABA, 2015; Ryder, 2015; FATF, 2012). However, due to country environment factor differentials, the FATF recommendations are perceived as internationally acceptable and the basis on which countries can customize accordingly.

Afande (2015) and Maguchu (2018) affirm that countries need to implement the FATF recommendations in line with the country`s environment. Implementation of the FATF recommendations has resulted in AML/CFT legislation. However, the level of implementation differs from country or region. Below are some of the implementations to date by Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia, Zimbabwe and United Kingdom.

4.3.1. Botswana

Legislative instruments dealing with money laundering and the financing of terrorism in Botswana are shown in

Table 3. The country’s money laundering challenges are coordinated and planned by the Financial Intelligence Agency of Botswana (FIAB). FIAB is responsible for the policy, regulation, supervision, research, informing and educating the public about money laundering conduits and possibilities in Botswana as a country (Government Of Botswana, 2018). FIAB derives its powers from the country`s Financial Intelligence Act of 2009.

4.3.2. Namibia

Namibia has three pieces of legislation dealing with money laundering and financing of terrorism (Namibia Financial Intelligence Centre, 2017). These legislative instruments are shown in

Table 4. Namibia`s FIA is legally mandated to oversee the fighting of money laundering and terrorism financing in the country, which promotes the integrity and stability of the financial system.

4.3.3. South Africa

In line with the FATF recommendations, South Africa passed several legislations to deal with money laundering and the financing of terrorism. As shown in

Table 5, the legislations include Prevention of Organised Crime Act (POCA), Financial Intelligence Centre Act (FICA); and Protection of Constitutional Democracy against Terrorist and Related Activities Act (POCDATARA). All these legislations are interlinked to ensure that no legal loopholes exist (Sujee, 2016). FICA and POCA are closely interlinked.

FATF and ESAAMLG jointly evaluated South Africa in 2009. The report concluded that South Africa was compliant with nine recommendations; largely compliant with thirteen recommendations; partially compliant with nineteen recommendations; and non-compliant with seven recommendations. South Africa was further placed under the regular follow-up process. The 2021 Mutual Evaluation report concluded that South Africa was largely compliant with seventeen recommendations, partially compliant with fifteen recommendations, compliant with three recommendations and not compliant with five recommendations. Comparing the 2009 and 2021 mutual evaluation reports, South Africa progressively made concerted efforts to ensure compliance with the forty FATF recommendations. Even though significant progress had been made in addressing money laundering threats, a lot of time and resources are needed (Sujee, 2016; Garffer, 2015). Clearly, the existence of legal framework does not guarantee the effectiveness or adequacy of it (Mniwasa, 2019b; Maguchu, 2018; Sujee, 2016).

4.3.4 . Zambia

As shown in

Table 6, Zambia has various pieces of legislation dealing with financial crimes. These include the establishment of the Financial Intelligence Agency, and measures addressing money-laundering and terrorism financing threats. The AML legislation is enforced by Zambia`s Financial Intelligence Agency (ZFIA) in liaison with other regulatory bodies (Simwayi & Haseed, 2011). ZFIA derives supervisory oversight from the Financial Intelligence Centre Act 46 of 2010, while money laundering is defined and criminalised in the Prohibition and Prevention of Money Laundering Act 44 of 2010 as amended.

4.3.5. Zimbabwe

Table 7 outlines the legislation dealing with AML/CFT issues in Zimbabwe. The AML/CFT legal framework in Zimbabwe consists of the Banking Use Promotion and Suppression of Money Laundering Act (Chapter 24:24) of 2004; Money Laundering and Proceeds of Crime Act (Chapter 9:24) of 2013; and Suppression of Foreign and International Terrorism Act. All financial institutions and designated non-financial institutions in Zimbabwe operate within the provisions of the AML/CFT legal framework and guidelines issued by Financial Intelligence Unit of Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (Gaviyau, 2019; Maguchu, 2018). The FIU derives its powers from the Banking Use Promotion and Suppression of Money Laundering Act (Chapter 24:24) of 2004.

According to GoZ (2020), the estimated value of money laundered for the period 2004 to 2018 was USD900 million. Furthermore, Zimbabwe`s money laundering risk was classified as medium by the National Risk Assessment of Zimbabwe. However, own country assessments could give an impaired conclusion, hence the need to rely on FATF regulatory assessments.

4.3.6. United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom (UK) and European Union (EU), they have also implemented various legislations to counter money laundering threats. Sujee (2016) notes that after the country assessment, the FATF concluded that UK had the best AML legislative framework which was compliant with the Vienna and Palermo conventions. Ryder (2012) had earlier alluded to the notion that UK was clearly committed to implementing the best international practices and guidelines on AML. Progressively, the UK has fully embraced the risk-based approach in dealing with money laundering threats (Jones & Knaack, 2019; Sujee, 2016).

The financial markets in the UK play a significant role in Europe and the whole world, hence pose greater vulnerability and risks. This is due to the magnitude, nature sophistication and location at the epicentre of the world.

The AML/CFT legislative framework in UK was broadened to include United Nations and European Union legislative provisions (Sujee, 2016; Ryder, 2015). Estimates of money laundered annually in the UK are between GBP23 billion to GBP75 billion (Financial Service Authority, 2011). However, the Home Office Treasury estimated a conservative amount of GBP10 billion. The AML framework in the UK exceeds the expected international standards (Ngcetane-Vika, 2022; Ofoeda, 2022; Ryder, 2015). Despite having the best legislative AML/CFT regulatory framework, money laundering cases continue to be recorded even in the UK and the USA. This implies that those launderers continue to devise ways of bypassing the regulatory framework through using technology. Hence, regulators need to be proactive.

4.3.7. United States of America

The United States has a crucial role in the global struggle against money laundering and terrorist funding as the largest economy and most influential national power (Esoimeme, 2020). The US has a comprehensive AML/CFT strategy in place that reflects international regulatory standards and applies strict punishments for non-compliance. The US is a member of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). Therefore, to avoid these penalties, financial businesses need to be aware of the relevant legislation and understand how to comply.

AML/CFT legislation in USA is underpinned mainly by the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) and USA Patriot Act. The purpose of the BSA, often referred to as the Currency and Foreign Transactions Reporting Act, is to prevent terrorists from utilizing financial institutions to hide or launder their illicit gains. The legislation requires financial institutions to provide documentation to authorities whenever their customers deal with irregular cash exchanges of more than US$10,000.

In the wake of the terrorist events on September 11, 2001, the United States expanded measures to combat money laundering and terrorism funding. By allowing all financial institutions to deploy anti-money-laundering (AML) systems, the USA Patriot Act of 2001 modified the BSA. The USA Patriot Act prevents and punishes terrorist crimes both domestically and abroad by stepping up law enforcement and improving money laundering controls. Additionally, it promotes the application of research techniques for the prevention of organized crime and drug trafficking in terrorism investigations.

In terms of the regulators, Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) and Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) are responsible. FinCEN, the primary AML/CFT program of the US Treasury Department, is regulated by one of the most significant agencies in the world: the Financial Intelligence Unit of the United States (FIU). To combat money laundering, terrorism funding, and other financial crimes, FinCEN is in charge of monitoring banks, financial institutions, and other businesses as well as examining abnormal activities and transfers. Additionally, to exchange information to stop financial crime, FinCEN works with local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies.

The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), which functions similarly to FinCEN in terms of AML/CFT capabilities, is tasked with overseeing and carrying out US economic and trade sanctions. OFAC seeks to prevent blacklisted countries, organizations, and individuals from committing financial and related offences.

In the US, there are repercussions for breaking AML rules and regulations (New York State Department of Financial Services, 2017). According to the guidelines set out by AML authorities, Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) must be reported in the United States whenever a major or suspicious transaction takes place. Financial institutions in the US are also required to adhere to thorough customer recognition systems to verify each client's real identity and avoid money laundering. However, in more serious circumstances, violations may lead to criminal and civil accusations, fines, and jail terms. Each division or site that is determined not compliant with AML requirements may face penalties under the BSA, as well as fines for each day the violation continues. For breaches in client due diligence, the BSA may levy fines ranging from $10,000 to $100,000 per day.

4.3.8. Europe Union

According to Chicos (2019) in Europe money laundering was enshrined in the Council of Europe Directive 91/308/EEC of 1991. Successive amendments have been made in line with FATF recommendations. For instance, the FATF recommendations at global level especially recommendation 1 which requires “countries should identify, assess and understand the money laundering and terrorist financing risks for the country” (FATF 2012:11). Article 7 of Directive 2015/849 (or fourth anti-money laundering directive) transposes this recommendation into an obligation for all EU member states.

Table 8.

Legislation in Europe Union dealing with AML/CFT.

Table 8.

Legislation in Europe Union dealing with AML/CFT.

| Group |

Legislation dealing with AML/CFT |

| European Union |

Directive no. 91/308/EEC on the prevention of the use of the financial system for money laundering; Directive no. 2001/97/EC of amending the Directive 91/308/EEC; Directive 2005/60/EC on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purpose of money laundering and terrorist financing; Directive 2006/70/EC laying down implementing measures for Directive 2005/60/EC as regards the definition of "politically exposed person" and the technical criteria for simplified customer knowledge procedures and for exceptions to financial activities occasionally or very limited; Council of Europe Convention on Laundering, Search, Seizure and Confiscation of the Proceeds from Crime and on the Financing of Terrorism, adopted in Warsaw on 16 May 2005; 4th AML Directive (EU Directive 2015/849 - European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2015 - requires ML risk assessment to be performed at three levels: a) at the supranational level (Directive 2015/849, Art. 6); b) at the national level (Art. 7); c) by each obliged entity (Articles 8 and 10–24) |

4.3.9. Hong Kong

Hong Kong is required to adopt the most recent FATF recommendations since it is a member of the FATF. Yim and Lee (2021) argued that adhering to global AML/CFT standards is crucial for Hong Kong to remain as a major global financial hub. Notably, to incorporate development in the environment, the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing (Financial Institutions) Ordinance (Cap. 615) was renamed the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance (Cap. 615) (AMLO), Hong Kong’s AML/CFT law, on 1 March 2018 (Lee, 2022). The AMLO (Cap. 615), the Drug Trafficking (Recovery of Proceeds) Ordinance (Cap. 405), the Organized and Serious Crimes Ordinance (Cap.455), the United Nations (Anti-Terrorism Measures) Ordinance (Cap. 575), the United Nations Sanctions Ordinance, and the Weapons of Mass Destruction (Control of Provision of Services) Ordinance are the main pieces of legislation in Hong Kong that deal with AML/CFT issues. The Hong King Monetary Authorities continue to encourage the financial institutions to enhance AML/CFT systems by adopting risk-based approach and applying emerging technologies such as regtech.

4.4. Regulatory Enforcement

Post 2007/8 GFC, much emphasis has been placed on effecting regulatory sanctions for non-compliance with the overall aim of safeguarding the financial system and improving transparency (Zetzsche, et al., 2019; Butler & Brooks, 2018). AML/CFT weaknesses affect the financial system’s integrity and national security (Teichmann & Wittmann,2022; Cutter, 2017). Regulators utilise formal and informal enforcements to deter corrupt behaviour. Enforcement action is dependent on the magnitude of non-compliance. Minor violations require commitment from the senior management on the need to rectify and no public announcement is made thereof. When the noncompliance is more severe, this needs to be formalised, publicised and prescribed legally. The safety and soundness of the financial system is affected by AML/CFT non-compliance. There are various enforcements issued out: cease and desist orders; forfeiture orders; and monetary penalties, which are discussed below.

4.4.1. Cease and Desist Order

The ‘cease and desist order’ is issued when a financial institution fails to establish and maintain AML programme or correct previously identified deficiencies (ABA, 2020; FFIEC, 2020; FDIC, 2019). Accordingly, this order is issued under these two circumstances. Firstly, failure to maintain the established AML/CFT programme. Secondly, failure to rectify regulatory deficiencies previously identified. As shown in Table 3.8, the cease-and-desist orders were issued to MUFG Bank, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, JP Morgan Chase and United Bank for Africa over the period 2008 to 2019. These were issued after deficiencies were noted in the AML/CFT programme and risk management (FINMA, 2018).

Table 8.

Cease and Desist Orders Issued.

Table 8.

Cease and Desist Orders Issued.

| Year |

Institution`s Name |

AML/CFT Deficiency noted |

| 2019 |

MUFG Bank – USA |

Deficiencies in the BSA/AML programme – training, internal controls, reporting, CDD |

| 2018 |

Industrial and Commercial Bank of China |

Failure to rectify previously noted regulatory shortfalls |

| 2013 |

JP Morgan Chase |

Deficiencies in the BSA/AML programme – training, internal controls, reporting, CDD |

| 2008 |

United Bank for Africa (New York) |

Failure to rectify 2007 regulatory deficiencies and CD order issued in 2007#3. |

| |

|

Deficiencies in the BSA/AML programme – training, internal controls, reporting, CDD |

These orders were issued mainly by USA regulatory authorities. Larson (2020) argues that the legal counsel of the concerned institution should be aware and appraised on the regulatory effect of being issued with cease-and-desist order. Consequentially, banks can reduce or shift banking operations or restructure the balance sheet (Grossman, 2014). Evidently, the institution’s legal counsel together with AML/CFT team should promote regulatory compliance throughout the organisation.

4.4.2. Financial Penalties

Financial penalties are levied on repetitive legal infringements or failure to effect corrective measures (ABA, 2020; FFIEC, 2020). The study outlines some of the financial penalties issued out hereafter.

i) United States of America (USA)

Debvoise (2018) confirms that more than USD1.7 billion anti-money laundering regulatory fines were imposed on financial institutions worldwide by mid-2018, which was close to the USD2 billion in 2017. Surprisingly, more than USD1 billion was from USA regulatory authorities. In the USA there are several regulatory agencies such as FinCEN, DoJ and FRB. Cutter (2017) points on the need for regulators in the US to have a single coordinating body on all AML violations and avoid excessively penalizing companies.

The regulatory authorities are also obliged to institute personal liability. This was confirmed in the Rabobank case in which an employee was demoted, or contract terminated for failure to raise query on the transaction with the authorities on the inadequacy of the AML/CFT programme. The bank was eventually fined USD360 million on the related AML/CFT weaknesses (DoJ, 2018).

During the period 2009 to 2014, US Bancorp (USB) failed to provide adequate surveillance on alerts due to insufficient staff (Debvoise, 2018). The entity had thresholds proportionate to transaction risk level. As a result, USB failed to investigate and detect suspicious transactions. Also, USB filed at least 500 inaccurate and incomplete suspicious transactions based on poor alert mechanisms, eventually USD185 million fine was imposed on the bank (FinCEN, 2018).

ii) United Kingdom (UK)

In the UK, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is the financial regulator. Money laundering through the financial institutions undermines the integrity of the financial services sector of the country. UK based financial institutions need to ensure that the financial system minimises the money laundering risks through proper checks and balances that are conducted routinely (Financial Conduct Authority, 2015).

In 2015, the regulator fined Barclays Bank a penalty amounting to GBP72.1 million for failing to comply with the CDD principles. The offences were committed during the period May 2011 to November 2014. FCA report also verified that Barclays failed to conduct the business operations with due care and diligence to minimise the risk of money laundering. During the said period of investigation, Barclays Bank facilitated transactions worth GBP1.88 billion for high-net-worth clients who were classified as politically exposed persons (PEP).

iii) Namibia

The FIC of Namibia instituted AML/CFT enforcement actions for the period 2016/7. These enforcement actions are publicised in the FIC `s Annual Report. This concurs with the transparency stability theory which requires the publicising of these reports to stakeholders (FATF, 2015; Sainah, 2015; Tadesse, 2006). This also improves the integrity of the financial systems since the banking sector is based on confidence and trust.

4.4.3. Forfeiture Order

The “forfeiture order” is issued as a last resort after exhausting all the other remedies. This order entails removing the assets from the institution`s operations (FDIC, 2019; Gleb, 2016). Most countries have this provision in their legislation. For instance, Zambia has Forfeiture of Proceeds of Crime Act 19 of 2010 which caters for civil and criminal seizure of proceeds of crime (Simwayi & Haseed, 2011). However, to date no regulator has exercised this order. This might indicate that regulators fear exercising this order as this could cause financial instability in the economy. If instituted, this goes against the regulator’s mandate of maintaining financial stability and consumer protection among others.

5. Critique of Global AML/CFT regulations and application

Technology has been designed to bypass existing regulatory frameworks (Rupeika-Apoga & Wendt, 2022; Vermack, 2018). The following are the criticism of the current AML/CFT global regulations as guided by FATF 40 recommendation and from applications of the same.

5.1. Critique by Application of Global AML/CFT regulations

5.1.1. Money laundering definition

Money laundering is defined as proceeds earned from drug related offences (Alldridge, 2003), while Van Duyne (2003) views money laundering as a process in which the launderers falsify sources of funds as legitimate using the banking system. Additionally, Shavirta (2008) posits that money laundering is a criminal activity which includes proceeds from illegal practices. These criminal practices include trade in illegal narcotics, human trafficking, arms trade, fraud and corruption.

The definitions advanced by Shavirta (2008), Van Duyne (2003) and Alldridge (2003) concur that money laundering involves legitimizing illegally earned proceeds. Shavirta’s (2008) definition shows the evolving nature of money laundering by including the predicate offences from Van Duyne (2003) and Alldridge (2003) definitions. However, with the passage of time, these definitions fail to capture the electronic and digital avenues used to disguise the original source of funds. These can include international and local money transfers, and technology-based means which are instant and requiring robust systems controls.

5.1.2. Fintech

Financial technology (fintech) refers to products and services that become available to the financial services industry because of technological advancements (Navi, 2017). Financial Services Board (2017) defines fintech as financial innovation derived from technology which delivers new applications, products, services, processes or business models in the financial systems and provision of these services. Fintech denotes firms or companies that offer the latest technologies and apparatuses to the financial services industry (Saksonova & Kuzmina-Merlino, 2017). Gomber, Koch and Siering (2017) view fintech as existing between modern technologies and banking services activities by challenging the existing norms in banking industry. Puschmann (2017:74) views fintech as “incremental or disruptive innovations in the context of the financial services industry induced by IT developments resulting in new intra- or inter-organisational business models, products and services, organisations, processes and systems.”

The definitions by Gomber et al (2017), Saksonova and Kuzmina-Merlino (2017), Puschmann (2017), Navi (2017) confirm the existence and incorporation of modern technologies into the banking activities. Furthermore, there is no universally accepted definition of fintech, which could be attributed to the evolving nature of the discipline.

5.1.3. Regtech

Financial Conduct Authority (2015:64) defines regulatory technology as “a subset of fintech that focuses on technologies that may facilitate the delivery of regulatory requirements more efficiently and effectively than existing capabilities.” These are technological solutions that utilise information and technology aimed at addressing regulatory compliance processes and problems (Johansson, Sutinen, Lassila, Lang, Martikainen, Lehner, 2019). Butler and Brooks (2018) view Regtech as technology-based solutions to several regulatory and compliance problems faced by the financial services industry. Another definition by Weber and Baisch (2018) perceives regtech as the technology-based solutions establishing a relationship between regulator and an intermediary in the scope of system design, compliance and regulation in any industry.

These definitions agree that RegTech is a technology-based solution aimed at addressing regulatory, compliance and system design problems. Thus, Johansson et al (2019), Butler and Brooks (2018), Weber and Baisch (2018) argue in their definitions to that effect. Weber and Baisch (2018) further expanded the solutions and understand them as not limited to financial services sector only but pervasive in different organisational spaces which result in regulatory compliance. The views of Butler and Brooks (2018) can be attributed to the increased regulatory sanctions witnessed after the 2007/8GFC. The definition of Financial Conduct Authority (2015) further illustrates the notion that RegTech is a subset of FinTech. Therefore, RegTech was developed from FinTech. Thus, RegTech is defined as technology-based solutions which is oriented at regulatory, system design and compliance issues in any sector. This alone demonstrates the complementary nature in addressing regulatory challenges.

5.1.4. Three Stage Process of Money Laundering

Drawbacks of the three-stage process and changes over time have led to the development of new approaches. Critics cite the three-stage process as being too simplified for the modern times, as money laundering can happen with no physical or actual money movement (see for instance: Naheem, 2019; Casella, 2018; Naheem, 2015; Choo, et al., 2014; Hopton, 2009). Casella (2018) argues that the three-stage process fails to take into consideration forms of electronic money being laundered. There have been instances when laundered money was not identified when using the traditional three step process.

For the money laundering activities to be effective requires a reliable medium (Papanicolaou, 2015). In order to formalize illegal earnings, money launderers prefer using the financial services sector as a reliable medium (Sotande, 2018; Panda & Leepsa, 2017). Evidently, in the USA and Switzerland HSBC cases, it was found that money launderers continued to use the formal financial system undetected (Naheem, 2019; ICIJ, 2015). In Zimbabwe (OFAC, 2016) and Tanzania (Mniwasa, 2019b), foreign AML regulators unearthed money laundering breaches and imposed regulatory penalties. This leaves the financial institution and wider financial system vulnerable to the relentless morphing of laundering practices.

Hopton (2009) posits that money laundering occurs every time when a financial transaction or relationship happens which involves any form of tangible or intangible benefit with origins from criminal activity. This approach is modern and shows that money laundering can occur at any given period with no money paid or received. Money laundering should be viewed as multi-faceted, complex, and ever-evolving (Naheem, 2019; Choo, et al., 2014).

5.1.5. Link between penalty and violations

Gleb (2016) argues that regulators need to show the link between penalties and AML/CFT violations. The lack of clarity and unpredictable penalties within countries impede financial sector growth (Zetzsche, et al., 2019). Instead, lack of clarity comes from FATF recommendations which are deemed as advisory than enforceable (AL-Rawashdeh, 2022; Gomber, et al., 2017; Gleb, 2016). As a consequence, financial institutions become risk averse to other economic participants which defeats the financial inclusion regulatory objective.

5.2. Critique by emerging trends

5.2.1. Technology innovations

Technology can result in innovative solutions or disrupt the current financial services and products. Remarkably, if technology leads to innovative solutions they need to be developed within the present regulatory framework, while if disruption occurs new development guidelines are needed (Basel Committee on Bank Supervision, 2018). The evolving nature and integration of the disciplines influences how to regulate financial transactions of a dubious or suspicious nature. Technological innovations require an interdisciplinary approach in understanding the impact to money laundering (Nejad, 2022; Kavuni & Milne, 2019). However, innovation and disruption interfere with the offering of services in a heavily regulated financial services sector. By failing to develop effective regulatory measures, money launderers exploit this opportunity by maximising their activities, consequently affecting the integrity and soundness of the banking system.

5.2.2. Technological and Regulatory gaps

Buttigieg et al (2019) examined the AML/CFT legal framework for crypto assets in Malta. Malta is considered a small state within the European Union and has the AML/CFT legal framework which covers virtual assets in the digitalized world as espoused by FATF Recommendation 15. No other country has this legal framework; hence the model was considered appropriate to serve as the baseline for adoption in the EU. It was further found that the framework addressed regulatory mandates of consumer protection, stability and integrity in the era of digital innovations. The legal framework is seen as a starting point to addressing AML/CFT issues given the rapid pace of financial innovations. However, the technological and regulatory gaps in the implementation of AML/CFT regulations continue to present opportunities for launderers and hinder effectiveness of regulations. Risk is dynamic and not static. In order to attain regulatory mandates, this should be based on adequate and effective design of data driven regulations without impeding innovation.

5.2.3. Cyber-attacks and Data Privacy

Technology lowers compliance costs while information privacy and security issues remain a threat (Buckley, et al., 2020; Butler & Brooks, 2018; Chin, 2016). Personal information can be misused and stolen by third party agents. There is need to minimize this downside of technology with the economy deriving greater benefits. In the face of new products and services, financial institutions still need to verify customer`s identities before the commencement of any relationship. Verification may need reliance on third party service providers which exposes them to cyber risks and data privacy issues (Mniwasa, 2019a; Irwin, Slay, Choo, Lui, 2014; Stokes, 2012). FATF recommendation 15, states that in outsourcing the technology services issues of data security and privacy needs to be addressed (FATF, 2012-2019).

5.2.4. Regulations paradigm shift

The paradigm shift from Know Your Customer to Know Your Data shows the movement to data-based regulations (Perlman & Gurung, 2019; Arner, et al., 2019; Lootsma, 2017). Big data is key in using financial application tools such as machine learning. Machine learning matches big data to identify any activity or pattern without any human interface. This assists in identifying suspicious transactions. Failure to identify suspicious transactions has been noted as one of the non-compliance reasons for regulatory fines and penalties imposed on banks. Thus, technology could enable financial institutions to have monitoring systems that detect normal and abnormal transaction behaviour. This aids in reducing the number of false alerts, thereby submitting quality suspicious reports to regulators.

Innovativeness in the financial services industry coupled with financial markets transformation for the world warrants redesign and reconceptualization of financial regulations (Yu, Gong, and Sampat, 2022; Arner, et al., 2017; Brummer, 2015). The paradigm shift makes regulations, regulatory bodies and financial services effective in meeting their mandates at an affordable cost (Bains, Sugimoto, and Wilson, 2022; World Economic Forum, 2016). However, success is based on adequate and effective design of data driven regulations without impeding innovation and attaining regulatory mandates.

RegTech brings the integration of technology into the bank’s risk management processes (Arner, et al., 2017; 2016). Most of the current banking regulations apply to the traditional banking model. However, in the digital innovation era, regulators still require banks to apply the same risk management practices to the current digital banking practices. Failure to apply culminates into non-compliance. Fintech is still emerging, evolving, and disrupting the financial services industry (Anagnostopoulos, 2018; Dong, 2017; Brummer, 2015). Based on the old regulations, banks are still expected to have sound AML practices. This is detrimental. Studies have opined that in this era of technological innovations, money laundering should be risk based and not rule based (Shust and Dostov, 2020; and ElYacoubi, 2020; Naheem, 2018; Vasiljeva and Lukanova, 2016).

6. Conclusion

The study aimed to provide an overview of the global AML/CFT regulations, application and how they should evolve in this dynamic environment. A qualitative inquiry was adopted which involved reviewing FATF recommendations and associated AML/CFT legislation, analyzing publicized AML/CFT regulatory enforcements, and related developments.

The study`s main findings include the country implementation of the global AML/CFT regulations differed due to political and economic factors amongst others. While the various AML/CFT enforcements done on sampled countries were mainly cease and desist orders and monetary penalties which were publicised. Forfeiture orders have not been issued. Criticising the global AML/CFT regulations centred on application of these regulations and emerging trends. These include among other definitions of money laundering, reference to the three stage of money laundering, link between penalty and violations, technological innovations and regulations paradigm shift, cyber-attacks and data privacy.

The following are the recommendations being proffered, it is our considered view that FATF Recommendations be revised, since AML/CFT risk is dynamic in the era of digital innovations. Regulatory enforcements should be risk based and not rule based. Thus, the FATF at global level should revise the FATF guidelines and be informed by research.

Also, AML/CFT regulators need to be pragmatic in responding to the environmental induced threats posed by digital currencies and digital economies. There is need to develop adequate and effective regulatory responses to ensure that technological outcomes are met without compromising regulatory objectives. Regulations should not be static but evolve as well. The paradigm shift makes regulations, regulatory bodies and financial services to be effective in meeting their regulatory mandates.

The areas of future studies should revolve around digital innovations and digital economies. These include AML/CFT guidelines for digital currencies and collaborative based research on the interdisciplinary nature of AML/CFT.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.G. and A.B.S.; methodology, W.G. and A.B.S.; software, W.G.; validation, W.G. and A.B.S.; formal analysis, W.G.; investigation, W.G.; resources, W.G.; data curation, W.G.; writing—original draft preparation, W.G.; writing—review and editing, A.B.S.; visualization, W.G.; supervision, A.B.S.; project administration, W.G.; funding acquisition, A.B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the University of South Africa.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Accornero, Matteo, and Mirko Moscatelli. 2018 "Listening to the buzz: social media sentiment and retail depositors' trust." Bank of Italy Temi di Discussione (Working Paper) No 1165 (2018).

- Alexandra, Micu; Ion, Micu. Financial Technology (FinTech) and its implementation on the Romanian non-banking capital market. SEA Practical Applications of Science 2016, 11, 379–84. [Google Scholar]

- Alldridge, Peter. 2003 Money laundering law: Forfeiture, confiscation, civil recovery, criminal laundering and taxation of the proceeds of crime. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2003.

- AL-Rawashdeh, Sami Hamdan, 2022. Criminal liability for the crime of money laundering and the regulatory framework for combatting it in Qatari law. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues 25, 1–17.

- Armitage, Andrew, and Diane Keeble-Allen (2008): "Undertaking a structured literature review or structuring a literature review: Tales from the field." In Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies: ECRM2008, Regent's College, London, p. 35. 2008.

- Anagnostopoulos, Ioannis. 2018 "Fintech and regtech: Impact on regulators and banks." Journal of Economics and Business 100 (2018): 7-25.

- Arner, Douglas Wayne, Janos Barberis, and Ross Buckley. 2017a Fintech, Regtech and the Reconceptualization of Financial Regulation. NortWestern Journal of International Law and Business, 37(3).

- Arnone, Marco, and Leonardo Borlini. 2010 "International anti-money laundering programs: Empirical assessment and issues in criminal regulation." Journal of Money Laundering Control 13, no. 3 (2010): 226-271.

- Basel Committee on Bank Supervision, 2018. Sound practices: Implications of fintech developments for banks and banks supervisors, s.l.: Bank for International Settlements.

- Butler, Tom; Brooks, Robert. On the role of ontology-based Regtech for managing risk and compliance reporting in the age of regulation. Journal of Risk Management in Financial Institutions 2018, 11, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Brummer, C., 2015. Disruptive Technology and Securities Regulation. Fordham Law Review, Volume (84), pp. 84-95.

- Buttigieg, Christopher P. Christos Efthymiopoulos, Abigail Attard, and Samantha Cuyle.2019 "Anti-money laundering regulation of crypto assets in Europe’s smallest member state.". Law and Financial Markets Review. 13, no. 4 (2019): 211-227. [CrossRef]

- Byttebier, Koen. and Adamos, Konstantionos., 2022. Cryptoassets–a new frontier for money laundering and terrorist financing: legal changes to address the increasing AML risk. Journal of Financial Crime, (forthcoming). [CrossRef]

- Carney, M., 2017. The promise of Fintech -something new under the sun? Wiesbak, Deutsche Budesbank G20 Conference on Digitising Finance.

- Chico Oana, (2019): Money laundering Internationally: Perspectives of Law and Public Administration Volume 8, Issue 1, May 2019. P.

- Clarke, Andrew Emerson. (2021), “Is there a commendable regime for combatting money laundering in international business transactions?”. Journal of Money Laundering Control. Vol. 24 No. 1, pp. 163-176. [CrossRef]

- Colaert, Veerle., 2017. Regtech as a response to regulatory expansion in the financial sector. KU Leuven, Research Unit of Economic Law.

- De Koker, Louis. and Turkington, Mark. (2016), “Transnational organised crime and the anti-money laundering regime”, in Hauck, P. and Peterke, S. (Eds), International Law and Transnational Organised Crime, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 241-263.

- Debvoise, 2018. 2018 Mid-Year Anti-Money Laundering Review and Outlook, New York: Debevoise & Plimpton LLP.

- Dermine, Jean., 2017. Digital disruption and bank lending. European Economy, Volume 2, pp. 63-76. 2.

- DoJ, 2018. Rabobank pleads guilty and agree to pay USD360 million, s.l.: US Department of Justice.

- Dong, He., 2017. Fintech and Cross Border Payments. New York, Central Bank Summit.

- Esoimeme, Eric Ehi, 2020. "Identifying and reducing the money laundering risks posed by individuals who been unknowingly recruited as money mules.". Journal of Money Laundering Control. 24.1 (2020): 201-212. [CrossRef]

- ElYacoubi, Dina. "Challenges in customer due diligence for banks in the UAE." Journal of Money Laundering Control (2020).

- FATF (2021), “High-level synopsis of the stocktake of the unintended consequences of the FATF standards”, Available online: www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/Unintended-Consequences.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- FATF. (2012). ‘International Standards on Combating Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism & Proliferation. The FATF Recommendations’. Paris, France: Financial Action Task Force - Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Available online: http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/recommendations/pdfs/FATF_Recommendations.pdf.

- FATF, 2012-2019. International Standards on Combatting Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism & Proliferation, Paris,France : FATF.

- FCA, 2018. FCA fines and imposes a restriction on Canara Bank for anti-money laundering systems failings, s.l.: FCA.

- FinCEN, 2018. FinCEN penalizes US Bank National Association for Anti-Money Laundering Laws Violations, s.l.: FinCEN,Feb 15 2018.

- Gaviyau, William; Sibindi, Athenia Bongani. Customer Due Diligence in the FinTech Era: A Bibliometric Analysis. Risks 2023, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government Of Botswana, 2018. Anti-Money Laundering Annual Report, Gaborone : Government of Botswana.

- Groepe, Francois., 2017. Regulatory responses to Fintech development. Joburg, Strate GIBS Fintech Innovation Conference 2017.

- Held, Micheal., 2019. The first line of defence and financial crime. New York,USA, The First Line of Defence Summit.

- Hill, John. Fintech and the remaking of financial institutions. Academic Press 2018. [CrossRef]

- Jones, H., 2016. Global Regulators move closer to regulatory Fintech, s.l.: Reuters.

- Koker, Louis De. (2022), "Editorial: Regulatory impact assessment: towards a better approach for the FATF", Journal of Money Laundering Control, Vol. 25 No. 2, pp. 265-267.

- Littrell, Charles 2022: Biases in National Anti-Money Laundering Risk Assessments (January 21, 2022). Available at SSRN. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4137532 (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Lootsma, Yvonne (2017). "Blockchain as the newest regtech application—the opportunity to reduce the burden of kyc for financial institutions." Banking & Financial Services Policy Report 36, no. 8: 16-21.

- Mniwasa, Eugene., 2019b. Money laundering control in Tanzania: Did the bank gatekeepers fail to discharge their obligations?. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 22(4), pp. 796-835.

- Naheem, Mohammed Ahmad. 2018: TBML suspicious activity reports – a financial intelligence unit perspective: Journal of Financial Crime, Volume 25, Number 3, 2018, pp. 721-733(13).

- Namibia Financial Intelligence Centre, 2017. Annual Report 2016/2017, Windhoek,Namibia: Financial Intelligence Centre. Annual Report 2016/2017.

- Nejad, Mohammad, 2022. Research on financial innovations: an interdisciplinary review. International Journal of Bank Marketing. [CrossRef]

- New York State Department of Financial Services (DFS) (2017) ‘DFS fines Deutsche Bank $425 million for Russian mirror-trading scheme. Available online: https://www.dfs.ny.gov/about/press/pr1701301.htm (accessed on 25 January 2017).

- Ngcetane-Vika (2022): “Comparative Analysis of Anti-money Laundering (AML) and Counter Terrorist Financing (CTF) Regimes in the UK and USA.” AfricArXiv, 31 May 2022.

- OECD (2022), “Regulatory impact assessment”. Available online: www.oecd.org/regreform/regulatory-policy/ria.htm (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- OFAC, 2016. Enforcement information, New York: Office of Foreign Assets and Control, USA Department of Tresuary Office.

- Ofoeda, Isaac, 2022. Anti-money laundering regulations and financial inclusion: empirical evidence across the globe. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, (forthcoming). [CrossRef]

- Papanicolaou, George., 2015. One Stop Brokers. Available online: https://www.onestopbrokers.com/2015/01/12/stages-money-laundering/ (accessed on 14 September 2018).

- Perlman, Leon. & Gurung, Nora., 2019. Focus Note: The Use of eKYC for Customer Identity and Verification and AML. Social Science Research Network, pp. 1-28.

- Phanwichit, Supatra., 2018. Fintech and causing customers to comply with Anti-Money Laundering Law. PSAKU International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research 7.

- Riccardi Michele & Milani Riccardo & Camerini Diana (2019): Assessing Money Laundering Risk across Regions. An Application in Italy: European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research (2019) 25, 21–43.

- Rupeika-Apoga, Ramona, & Stefan Wendt. 2022. "FinTech Development and Regulatory Scrutiny: A Contradiction? The Case of Latvia" Risks 10, no. 9: 167.

- Saksonova, Svetlana, and Irina Kuzmina-Merlino, 2017. Fintech as financial innovation - The possibilities and problems of implementation. European Research Studies. 20(3A), pp. 961-973. [CrossRef]

- Shust, Pavel & Dostov, Victor., 2020. Implementing Innovative Customer Due Diligence: Proposal for Universal Model. Journal of Money Laundering Control. 7(1), pp. 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Sujee, Zain Jadewin, 2016. A study of the anti-money laundering framework in South Africa and the United Kingdom, Pretoria, South Africa: PhD Thesis, Univeristy of Pretoria.

- Teichmann, Fabian Maximilian Johannes, and Chiara Wittmann. (2022), "Money laundering in the United Arab Emirates: the risks and the reality", Journal of Money Laundering Control (forthcoming). [CrossRef]

- Lee Emily (2022): Technology-driven solutions to banks’ de-risking practices in Hong Kong: FinTech and blockchain-based smart contracts for financial inclusion: Common Law World Review 2022, Vol 51(1-2) 83–108.

- Vasiljeva Tatjana, and Lukanova Kristina, 2016 Commercial Banks and Fintech Companies in the Digital Transformation: Challenges for the future: Journal of Business Management, 2016, No.11.

- Whisker, James, & Mark Eshwar Lokanan, 2019. Anti-money laundering and counter terrorist financing threats posed by mobile money. Journal of Money Laundering Control. 22(1), pp. 158-172. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Dong, & Min Li Yang,2018. Evolutionary approaches and the construction of technology driven regulations. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, Volume 54, pp. 256-271.

- Yap, Brian., 2016. Key take aways:Fintech Asia 2016- Navigating legal risks and regulation. London, International financial law review 35, no. 44 (2016): 1-1.

- Yim, Foster Hong-Cheuk and Lee, Ian Philip. (2021), "Updates on Hong Kong’s anti-money laundering laws 2020", Journal of Money Laundering Control, Vol. 24 No. 1, pp. 3-9.

- Yuen, Aurthur., 2018. Regetch in the smart banking era-a supervisor`s perspective. Hong Kong, HKIB Annual Banking Conference.

- Zabelina, O. A., Vasiliev, A. A. & Galushkin, S. V., 2018. Regulatory Technologies in the AML/CFT. s.l., III Network AML/CFT Institute International Scientific and Research Conference " FinTech and RegTech: Possibilities,Threats and Risks of Financial Technologies".

- Zetzsche, Dirk,, Arner, Warner. Douglas, Buckley, Ross. & Weber, Rolf, 2019. The Future of Data-Driven Finance and RegTech: Lessons from EU Big Bang II. EBI Working Paper Series, Issue 35.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).