1. Introduction

Material degradation should be considered in power plants, chemical processing, and similar industries. Material degradation is a decrease in the ability or properties of a material, either physically or mechanically, over time due to mechanical, thermal, or electrochemical loading. Degradation on the material’s surface can take the form of corrosion and wear. Corrosion is the process of a metal reverting to its thermodynamic state; for most materials, this means the formation of oxides or sulfides from which they originally started when extracted from the earth before being refined into valuable engineering materials. Corrosion in aqueous solutions is the most common of all corrosion processes. The industry’s water, seawater, and various process streams provide an aqueous medium where corrosion can occur [

1]. Seawater is used for various industrial activities such as transport, exploration of natural resources, power production, and water supply. Seawater is a highly corrosive environment and is still challenging to corrosion experts; in some tests, natural seawater is used as an electrolyte. The main factors that make seawater such a corrosive fluid are divided into two groups: biochemical (oxygen, carbonate, salts, organic compounds, biochemical activity, and pollutants) and physical (temperature, flow velocity, potential, pressure) [

2].

The heat exchanger is equipment that facilitates the exchange of heat between two fluids at different temperatures. Heat exchangers are used in many engineering applications, such as power plants, chemical processing systems, food processing systems, and waste heat recovery units. Air preheaters, economizers, evaporators, superheaters, condensers, and cooling towers used in a power plant are a few examples of heat exchangers [

3]. The selection of materials for a heat exchanger must consider operating parameters, cost and reliability, physical properties (high heat transfer coefficient, thermal expansion coefficient), mechanical properties (tensile strength, creep resistance, fatigue limit, fracture toughness), and corrosion resistance. Because many factors are considered, the material used for heat exchangers varies, including Monel, Duplex, Super Duplex, Hastelloy, and Inconel [

4,

5].

2205 DSS or UNS S31803 is categorized as a standard duplex stainless steel with a low carbon content, 22% chromium, 5% nickel, 3% molybdenum, and controlled nitrogen additions. They have a reduced nickel content compared to standard austenitic stainless steels, which gives a duplex microstructure, and they contain molybdenum and nitrogen for corrosion resistance. These steels are always solution-treated, followed by quenching to give an approximately 50% austenite and 50% ferrite duplex microstructure without deleterious phases, such as sigma. 2205 DSS has a typical PREN of 35 or more. By 2000, they had become Europe’s third most widely used grade of stainless steel, after types 316L and 304L. 2205 DSS offers high strength (approximately twice that of standard austenitic stainless steel grades such as 316L), good general corrosion resistance in a variety of environments, high resistance to chloride-induced SCC, and high resistance to pitting attack in chloride environments, e.g., seawater [

5,

6].

Although the material selection process has been carried out comprehensively, sometimes failures occur due to other factors. Several failure modes of heat exchangers have been identified; the most common modes are fatigue [

7,

8], creep[

9,

10], oxidation[

11], and hydrogen attack[

12]. The common causes of heat exchangers include weld defects[

13,

14], vibration[

15,

16], erosion[

17,

18], stress corrosion cracking[

19,

20,

21], and microbial-induced cracking [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Considering its numerous failure modes, the failure of the heat exchanger should be analyzed by recognizing the possible root cause, especially the lessons learned from previous studies.

In this study, a shell and tube heat exchanger used as a discharge cooler at a power plant experienced corrosion. The tube and tube sheet material was 2205 Duplex Stainless Steel (DSS), and the cooling medium of the heat exchanger was seawater. Some defects were found in the tube and tube sheet, such as leaked tubes, deposits under the plug, and the formation of scales. This study was conducted to determine the root cause of the failure; the failure could be caused by improper material selection, fabrication process, installation process, or operation process. It is hoped that by conducting this study, similar failures will not occur in the future.

2. Materials and Methods

The failed component was a shell and tube heat exchanger of BEM TEMA type without an end channel, and it was used as a discharge cooler. According to the Tubular Exchanger Manufacturers Association, Inc. (TEMA) nomenclature, BEM is described as a bonnet (integral cover) front-end stationary head type, one pass shell type, and a fixed tube sheet stationary head, rear end head type. The illustration of BEM TEMA-type heat exchangers is shown in

Figure 1, and some essential parts to be discussed in this study are described in

Table 1. This heat exchanger cools the discharge gas from the third-stage compressor. The cooling medium for this heat exchanger was seawater. The shell design pressure was 22.6 MPa at 422K, and the tube design pressure was 1 MPa at 339K.

This heat exchanger used two types of materials: the shell material was carbon steel, and the tube and tube sheet material was 2205 duplex stainless steel (UNS S31803). A hypochlorite solution at two ppm by volume was injected into the running pump caisson to prevent marine growth in the cooling water; a flow of 15 to 20 US gallons per minute of hypochlorite solution should be maintained for any running pump. Although 2205 DSS offers high strength, good general corrosion resistance, high resistance to chloride-induced SCC, and high resistance to pitting attack in chloride environments, e.g., seawater [

5], in this study case, the cooler experienced some material degradation; 26 tubes were leaked and plugged both sides, and scales plugged 76 tubes. This study conducted a corrosion study and found out the root cause of the cooler failure.

The failure investigation was conducted on two heat exchangers, one on the platform and one laid down in the warehouse due to some defects. Visual inspections were conducted on both heat exchangers, including the welded section of the tube and tube sheet, plugged and unplugged tubes. The chemical composition of the tube and tube sheet material was examined using a Hilger E-9 OA701 optical emission spectroscopy to confirm the alloy grade. The hardness test was conducted on the tube and tube sheet material using a TB-V-10 Vickers microhardness tester with a load of 200 grams to confirm the alloy grade. The chloride content, water salinity, sulfate content, and total dissolved solid of the cooling medium were determined by conducting a seawater examination. Energy Dispersive Spectrometry (EDS) used JEOL JSM 6510 LA and X-ray diffraction with Rigaku Smart Lab to examine the tube deposit scale. A fractography examination was conducted using a scanning electron microscope JEOL JSM 6510 LA to observe the corrosion appearance. The microstructure of the tubes was examined by cutting some samples at the corroded region, mounted into cold-setting resin, ground, and polished. The polished samples were swabbed with etchant and observed under an optical microscope. [

27]

3. Results

3.1. Visual Examination

Visual examinations were conducted on two heat exchangers.

Figure 2(a) is the photograph of heat exchangers at the platform; defects were found on the welded section between the tube and tube sheet in A section, B, and C sections show the defect of the tube sheet under the gasket area, the further examination of this defect are shown at

Figure 3(a,b). The heat exchanger’s tube sheet at the warehouse (

Figure 2(b)) contains some leaked tubes. D section shows that some leaked tubes were plugged and weld overlayed. For further examination, the heat exchanger at the warehouse was cut into some sections, including the tube sheet and gasket interface, tube sheet inlet sections, and the tube itself.

Figure 3(a,b) are the further examination of

Figure 2(a) in the B section. Pitting defects under the gasket can be seen at those tube sheet interfaces; this defective surface will be examined further to determine the root cause of pitting defects.

Figure 3(c,d) are the cut piece of seawater inlet tube sheets. As practical information, when corrosion was found on the tube sheet, a plug was applied to the corroded tube, and the tube sheet was repaired by overlaying the tube sheet.

Figure 3(e) shows a cut plugged tube on the outlet side; white scale deposits were observed inside the tubes. Two pieces of the plugged tubes were cut for laboratory examinations to examine the crack locations. The outer surface of the tube was cleaned with fine emery paper and observed visually by dye penetrant and magnifying glass. There was no crack observed on the outer surface of the tube. Some shallow pitting was observed on the outer surface closed to the outlet side. However, this pitting was started from the outer surface, and some of them can be removed by emery paper.

Figure 3(f) shows the defective tube’s surface appearance. For further examination, the appearance of the tube’s inner surface conditions was done by cutting the tube longitudinally; this examination was conducted on the plugged tube, an unplugged tube, and a good tube, a standard tube without defect.

The cross-section of the excellent tube

Figure 4(a) shows that a weld overlay joined the tube and tube sheet; the overlay of the tube sheet protected it from corrosion and sealed the possible gap between the tube and tube sheet. No defect like corrosion or leak was observed in this tube, and the weld overlay sealed the gap between the tube and tube-sheet well.

Figure 4(b,c) are the macro-photograph of the plugged tube, and the tube was initially cold expanded to the tube sheet. Corrosion occurred on the tube sheet and has been repaired by weld overlay.

Figure 4(d,e) are pictures of the plugged tube’s inner surface. Heavy deposits under the plug were observed, and some deposits along the tube indicated the presence of biofilm that may promote microbiological-induced corrosion.

Figure 4(f) is the cross-section of the unplugged tube. Heavy deposit on the entrance side was observed, and some deposits along the tube indicated the presence of biofilm that may promote microbiological-induced corrosion.

3.2. Chemical Composition

The chemical composition of tube and tube sheet material was examined by optical emission spectrometry. The result is shown in

Table 2.

Based on optical emission spectrometry results, the tube and tube sheet materials comply with duplex stainless steel ASTM A-790/UNS S31803. The mechanical properties of UNS S31803 are shown in

Table 3.

3.3. Hardness Test

Besides chemical composition, a hardness test was conducted by a Vickers microhardness tester, with a load of 200 grams, for material confirmation purposes. The survey was conducted on tubes and tube sheet material, and the hardness distribution is shown in

Table 4.

The hardness of the tube and tube sheet is below the ASTM A-790/UNS S31803 specification and is widely scattered due to the torch cutting and the heating effect, which may cause a significant variation in the material hardness.

3.4. Seawater Examination

A seawater examination was conducted to determine the seawater’s salinity, chloride, sulfate, and total dissolved solids. Samples were taken from the Discharge Cooler and the Discharge Cooling Pump. The analysis results are shown in

Table 5.

Seawater salinity can be calculated as [

29]:

Based on the equation, the salinity is 33.4%

o, and the increase in salinity increases the rate of calcium carbonate precipitation [

30]. The chloride content is typical for seawater (around 19000 mg/l), and the sulfate content is also considered normal (around 2600 mg/l) [

29]. The total dissolved solids are considerably high (32 g/l) and will contribute to the formation of deposits/scale in stagnant conditions.

3.5. Scale Examination

The tube deposit from

Figure 3(e) was examined using SEM and EDS.

Figure 5(a) is the SEM macrograph of the tube scale deposit; the particle size is very fine, indicating that it was formed through a chemical reaction.

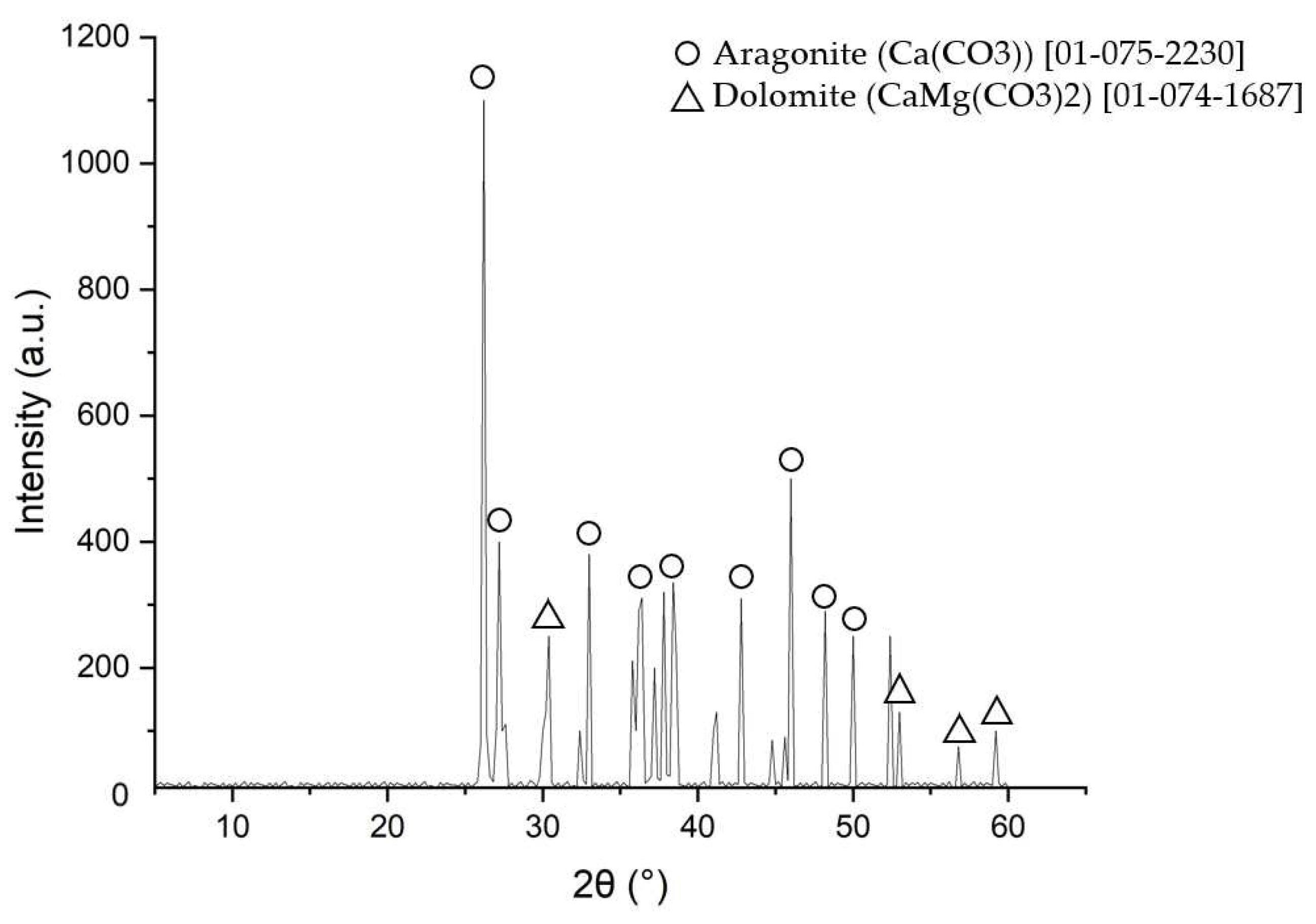

Figure 5(b) results from energy dispersive spectrometry of the tube deposit, with dominant calcium, magnesium, and oxygen elements. An XRD examination will further analyze this result, as shown in

Figure 6.

Based on the XRD examination results, the majority of the tube scale is Aragonite (CaCO3) and Dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2). The X-ray diffraction result confirmed the energy dispersive spectrometry data, which showed that calcium, magnesium, and oxygen are the main components in the tube deposit. The mechanism of scale formation and the composition of the scale will be discussed further in the discussion section.

3.6. Fractography Examination

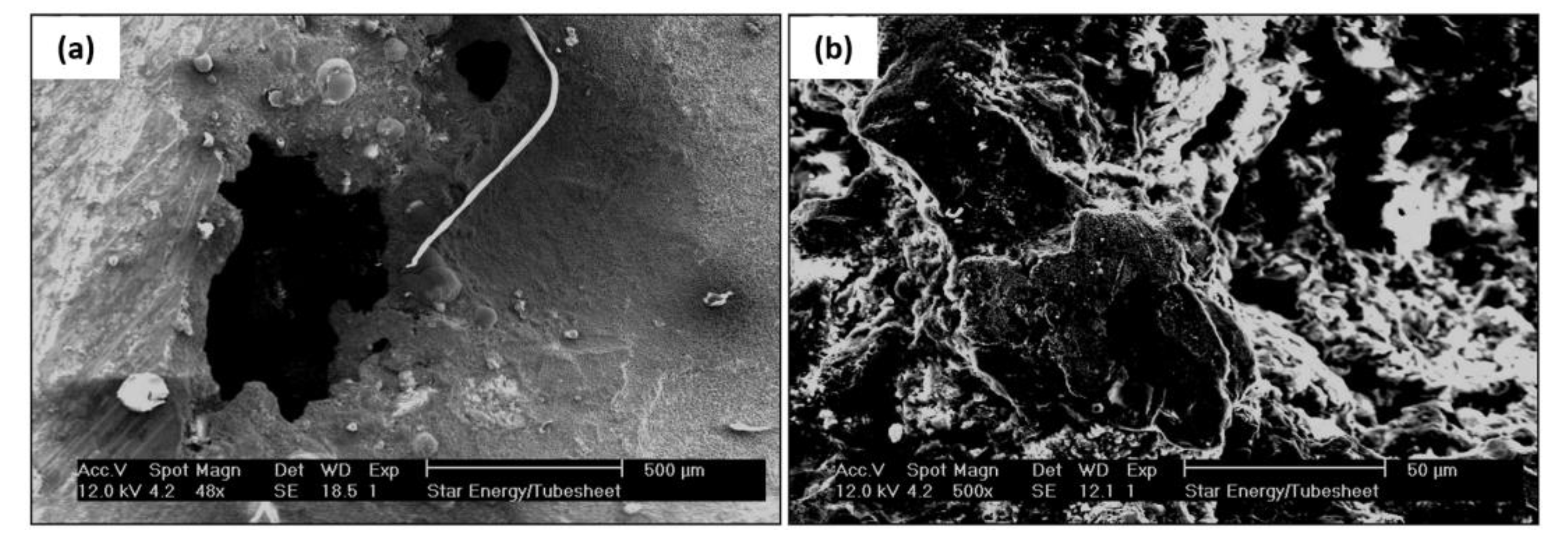

The surface of the tube sheet in

Figure 3(a,b) was cleaned with Clark solution before examination; the dirt on the surface cannot be entirely removed by Clark solution. The SEM micrograph of the tube sheet’s defective surface shown in

Figure 7(a) reveals traces of barnacles. The pitting present indicates the effect of a microbiological attack on the surface [

31].

Figure 7(b) is the scanning electron macrograph of another defective surface; the pitting geometry indicates the effect of crevice corrosion attack or corrosion under deposit. Detail examination of the defective surface cannot be performed because a permanent deposit still covers the surface.

3.7. Microstructural Examination

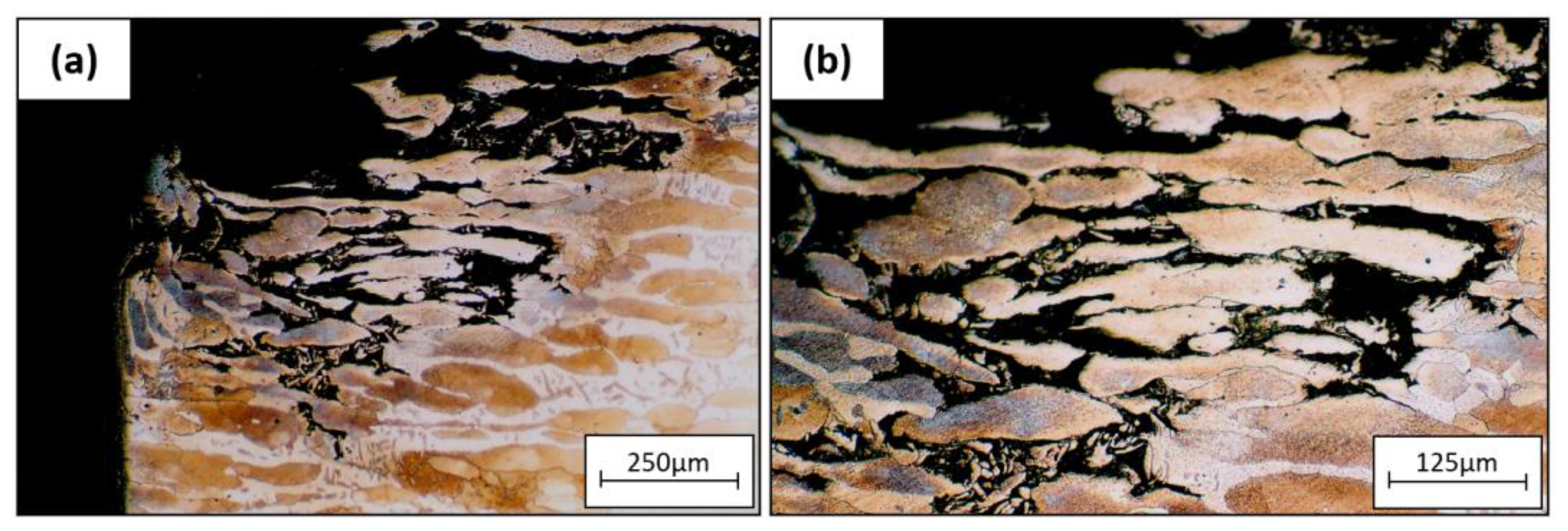

The corroded surface of the tube sheet from

Figure 3(a) was examined using an optical micrograph. According to

Figure 8(a,b), corrosion attack occurred preferentially along the austenite grains. On the contrary, there is no attack on the ferrite grain. Preferential attack on the austenite grain of the weld metal has also been observed during the crevice corrosion test of Ferralium Alloy 255 duplex stainless steel weldments (Cr = 25.5%, Ni = 5.5%, Mo = 3.0%) [

32]. The corrosion attack on this part of the tube sheet is caused by crevice corrosion that forms pitting colonies on the tube sheet surface.

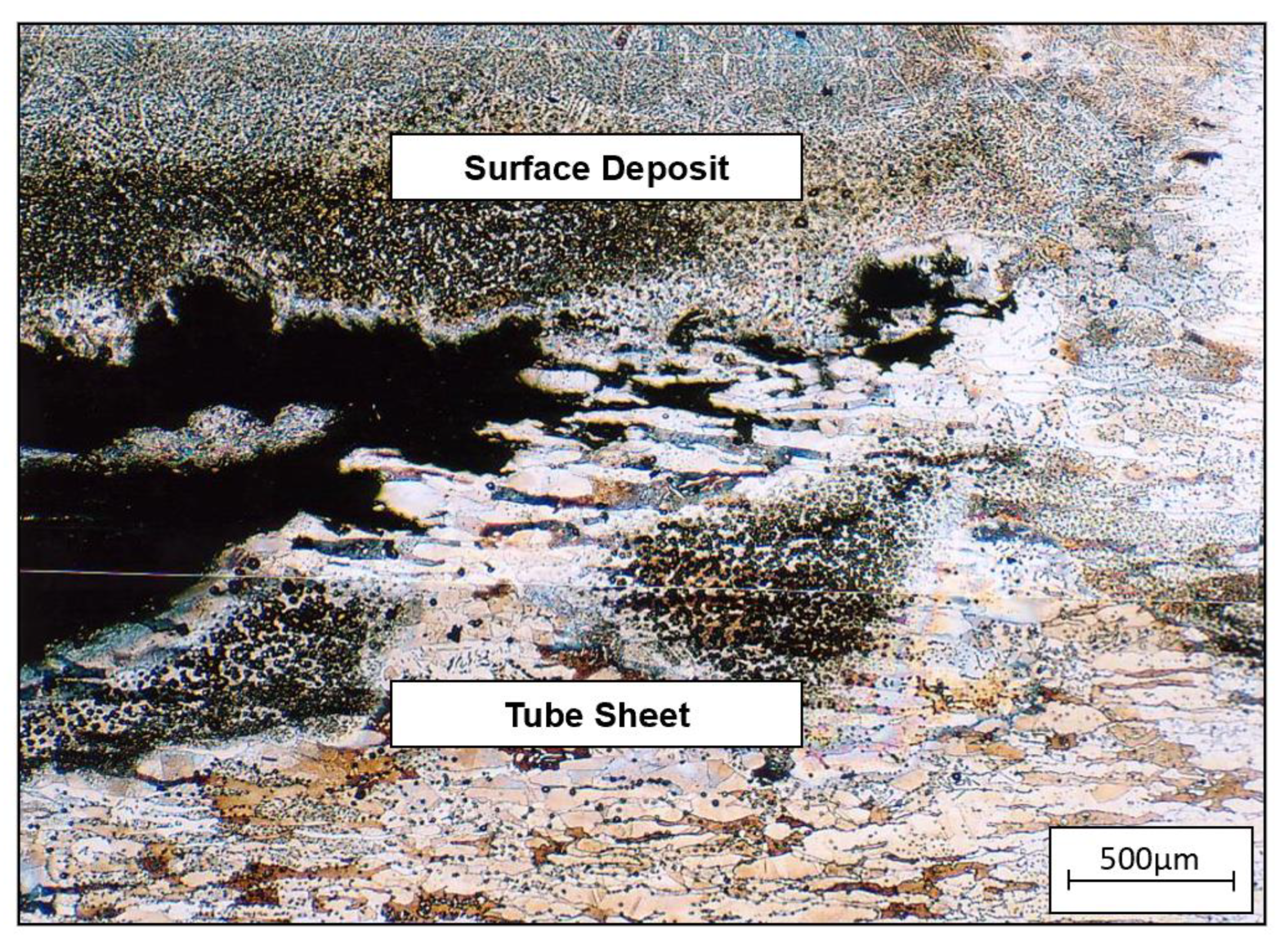

Figure 9 is the optical micrograph of the corroded tube sheet at the other location. The type of attack is different from that of

Figure 8. The corrosion attack occurred under deposit. Previous fractography data indicated that corrosion in this site is caused by micro/macro fouling. However, the corrosion occurred under the gasket; therefore, the macro/micro fouling was formed and attacked the tube sheet surface. The corrosion mechanism combines crevice and microbiological corrosion[

33].

Figure 10 is the optical micrograph of the unplugged tube, corrosion occurred on the inner surface of the tube, and the austenite grains were attacked by crevice corrosion. Corrosion also occurred on the tube sheet overlay.

Figure 11 is an optical micrograph of a plugged tube.

Figure 11(a) shows the inner surface of the tube attacked by corrosion, with the depth of the austenite grains attacked being 141μm.

Figure 11(b) shows the occurrence of corrosion in the crevice between the plug and the tube. The tube-sheet overlay is also attacked by corrosion (

Figure 11(c)).

4. Discussion

Tube and tube sheet materials are made of duplex stainless steel UNS 31803. Corrosion of the tube sheet may be caused by galvanic corrosion between the gasket and the tube sheet or between the tube sheet and carbon steel shell, crevice corrosion, and microbiological corrosion. The probability of each corrosion mechanism will be discussed further in 4.1, 4.2, and 4.3.

4.1. Galvanic Corrosion

Galvanic corrosion occurs when a metal or alloy is electrically coupled to another metal or conducting non-metal in the same electrolyte. During galvanic coupling, corrosion of the less corrosion-resistant metal increases while corrosion of the more corrosion-resistant metal decreases. The driving force for corrosion or current flow is the potential developed between dissimilar metals. The possible galvanic coupling is between the tube sheet and conductive gasket and between the tube sheet and carbon steel shell. The type of gasket material is unknown, so the possibility of galvanic coupling cannot be determined [

34].

There are two reasons galvanic coupling did not cause tube sheet corrosion. First, when the galvanic coupling formed between the tube sheet material and carbon steel shell, carbon steel would corrode because it is less noble than duplex stainless steel. Corrosion occurred in the tube sheet but not in the shell material. Second, most galvanic corrosion attacks are similar to general corrosion without surface deposits. If the attack is pitting, the pitted surface will be shiny, and there will be no surface deposit.

4.2. Crevice Corrosion

Small pits can form on the steel surface under certain specific conditions, particularly involving chlorides (such as sodium chloride in seawater) and exacerbated by elevated temperatures. Depending on both the environment and the steel itself, these small pits may continue to grow, and if they do, they can lead to perforation, while most of the steel surface may still be unaffected. Crevice corrosion can be considered a particular case of pitting corrosion, where the initial pit is provided by an external feature, such as a narrow opening or spaces (gaps) between metal-to-metal or nonmetal-to-metal components. Similarly, unintentional crevices such as cracks, rough surfaces, sheared edges, and other metallurgical defects can be sites for corrosion initiation. Crevice attack also occurs under deposits and biofouling growth attached to the metal surface [

35].

Stainless steel groups, including duplex stainless steel, a passive alloy, are more prone to crevice attack in seawater than materials that exhibit more active behavior. The pitting resistance of duplex stainless steel is defined as resistance to localized corrosion attack and is expressed as Pitting Resistance Equivalent Number (PREN) [

36]:

Using PREN as a reference, several duplex stainless steels with different alloy content will have different pitting resistance, as shown in

Table 6.

According to

Table 6, UNS 31803 has lower pitting resistance than the other grades. The pitting resistance of duplex stainless steel in seawater can be expressed as Critical Pitting Temperature (CPT), below which pitting will not occur. Similar to pitting corrosion, the susceptibility of duplex stainless steel to crevice corrosion is expressed as Critical Crevice Temperature (CCT).

Figure 12 shows some of stainless steel’s critical pitting and crevice temperatures in a 6% ferric chloride solution for 24 hours [

37].

UNS S31803 has the lowest pitting and crevice corrosion resistance among duplex stainless steel. The critical crevice temperature of UNS S31803 is about 20oC; above this, crevice corrosion will occur. The severity and rate of crevice corrosion will depend on the crevice’s geometry and the seawater’s quality. Crevice corrosion of the tube-sheet is likely to occur under the gasket and between tube to tube-sheet joint. Crevice corrosion under the gasket is a consequence that cannot be prevented for seawater service unless a better design and a better material are selected. The expanded joint type is not recommended for tubes and tube sheets used in seawater service, as the possibility of crevice formation is much higher than that of a welded joint. Applying an overlay on the tube-sheet surface is accepted, but the overlay material shall be selected to avoid crevice corrosion. The current overlay was insufficient to prevent crevice corrosion, as some have been attacked. The surface quality of the overlay should also be considered because a rough surface will create tiny crevices that can harm the surface.

4.3. Microbial Corrosion

In certain circumstances, microbial activity can influence the corrosion process and typically involves microbes that metabolize sulfur compounds, producing an aggressive, acidic, hydrogen sulfide-containing localized environment [

38]. When stainless steel is in contact with natural seawater, a biofilm will grow on the steel surface. Crevice corrosion may also occur because of localized deposits or differential aeration cells caused by slime-forming bacteria. Corrosion due to microbial activity has the form of a pitting attack. Since UNS S 31803 is prone to crevice attack, accumulating microbes in the crevice region will promote pitting corrosion under deposit. Localized deposits cause tube corrosion on the inner surface under the biofilm formed.

According to the XRD scale examination, calcium carbonate (CaCO3) is the tube deposit. Calcium-carbonate sediments are prevalent in the ocean. The origin of calcium carbonate is the result of the following chemical reaction [

39]:

In the form of Ca

+2 ion, calcium is one of the major inorganic positive ions (cations) in saltwater and freshwater. It can originate from the dissociation of salts, such as calcium chloride or calcium sulfate, in water.

Most calcium in surface water comes from streams flowing over limestones (CaCO

3), gypsum (CaSO

4.2H

2O), and other calcium-containing rocks and minerals. Calcium carbonate is relatively insoluble in water but dissolves more readily in water containing significant levels of dissolved carbon dioxide [

39]. Tube deposit was found only on plugged tubes. The tube deposit comes from the solid particles in seawater, as the total dissolved solid content is high. If the outlet ends were not plugged, seawater could enter the plugged tube from the outlet side. This way, the seawater will remain in the plugged tube, and the solid or colloidal particles will be deposited inside the plugged tube. Solid particles will be accumulated due to the low velocity and almost stagnant seawater inside the plugged tube.

5. Conclusions

UNS S31803 shell and tube heat exchanger that cooled by seawater experienced corrosion was caused by crevice corrosion and crevice corrosion enhanced by microbiologically induced corrosion (MIC) according to visual examination with the corrosion area between tube and tube sheet overlay, scale examination that contained Aragonite (CaCO3) and microstructural examination that reveal corrosion attack occurred preferentially along the austenite grains.

Some efforts to prevent similar crevice corrosion enhanced by microbiological-induced corrosion (MIC) in heat exchangers (discharge coolers) include upgrading material to ones that can resist crevice corrosion in seawater at the operating temperature, which can be determined by the critical pitting temperature (CPT) and critical crevice temperature (CCT). In the design and manufacturing aspects, there are several efforts to avoid crevice corrosion, including designing and fabricating to avoid trapped and pooled liquid; designing and fabricating to avoid crevices; using a weld joint between the tube and tube-sheet instead of a cold expanded joint; preparing surfaces to best possible finish (mirror finish resist pitting best); removing all contaminants and weld scale; and welding using the correct consumables and practices, and inspect to check for inadvertent crevices. The application of an overlay on the tube-sheet surface is accepted. The current overlay was insufficient to prevent crevice corrosion, as some have been attacked. The surface quality of the overlay should also be considered because a rough surface will create tiny crevices that can harm the surface.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, Afriyanti Sumboja; Investigation, Thomas Albatros; Writing – review & editing, Husaini Ardy..

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Schweitzer, P.A. Fundamentals of Metallic Corrosion: Atmospheric and Media Corrosion of Metals; 2006; pp 1-5.

- Shifler, D.A. La Que’s Handbook on Marine Corrosion; 2021; pp 1-24.

- Balaji, C.; Srinivasan, B.; Gedupudi, S. Chapter 7 - Heat Exchangers. In Heat Transfer Engineering; Balaji, C., Srinivasan, B., Gedupudi, S., Eds.; Academic Press, 2021; pp. 199–231 ISBN 978-0-12-818503-2.

- Morales, M.; Chimenos, J.M.; Fernández, A.I.; Segarra, M. Materials Selection for Superheater Tubes in Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Plants. J Mater Eng Perform 2014, 23, 3207–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, V.S.; Lima, L.D.; Pardal, J.M.; Kina, A.Y.; Corte, R.R.A.; Tavares, S.S.M. Influence of Microstructure on the Corrosion Resistance of the Duplex Stainless Steel UNS S31803. Mater Charact 2008, 59, 1127–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.C.M. Farrar The Alloy Tree, A Guide to Low-Alloy Steels, Stainless Steels and Nickel-Base Alloys; 2004; pp 53-62.

- Ravindranath, K.; Tanoli, N.; Gopal, H. Failure Investigation of Brass Heat Exchanger Tube. Eng Fail Anal 2012, 26, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, C.R.F.; Alves, G.S. Failure Analysis of a Heat-Exchanger Serpentine. Eng Fail Anal 2005, 12, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.R.H. Creep Failures of Overheated Boiler, Superheater and Reformer Tubes. Eng Fail Anal 2004, 11, 873–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psyllaki, P.P.; Pantazopoulos, G.; Lefakis, H. Metallurgical Evaluation of Creep-Failed Superheater Tubes. Eng Fail Anal 2009, 16, 1420–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kain, V.; Chandra, K.; Sharma, B.P. Failure of Carbon Steel Tubes in a Fluidized Bed Combustor. Eng Fail Anal 2008, 15, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Arada, M.; Al Otaibi, M. Evaluation of High Temperature Hydrogen Attack Effect on Carbon Steel - 0. 5 Mo Heat Exchanger. In Proceedings of the NACE - International Corrosion Conference Series; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Otegui, J.L.; Fazzini, P.G. Failure Analysis of Tube–Tubesheet Welds in Cracked Gas Heat Exchangers. Eng Fail Anal 2004, 11, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corleto, C.R.; Argade, G.R. Failure Analysis of Dissimilar Weld in Heat Exchanger. Case Stud Eng Fail Anal 2017, 9, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ding, N.; Shi, J.; Xu, N.; Guo, W.; Wu, C.M.L. Failure Analysis of Tube-to-Tubesheet Welded Joints in a Shell-Tube Heat Exchanger. Case Stud Eng Fail Anal 2016, 7, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyder, H.G.D. Flow-Induced Vibration in Heat Exchangers. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2002, 80, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuźnicka, B. Erosion-Corrosion of Heat Exchanger Tubes. Eng Fail Anal 2009, 16, 2382–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Yang, Z.-G.; Yuan, J.-Z. Failure Analysis of Leakage on Titanium Tubes within Heat Exchangers in a Nuclear Power Plant. Part II: Mechanical Degradation. Materials and Corrosion 2012, 63, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, C.; Wang, W. Failure Analysis of Stress Corrosion Cracking in Heat Exchanger Tubes during Start-up Operation. Eng Fail Anal 2015, 51, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnyana, D.N. Failure Analysis of Stainless Steel Heat Exchanger Tubes in a Petrochemical Plant. Journal of Failure Analysis and Prevention 2018, 18, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodamorad, S.H.; Alinezhad, N.; Haghshenas Fatmehsari, D.; Ghahtan, K. Stress Corrosion Cracking in Type.316 Plates of a Heat Exchanger. Case Stud Eng Fail Anal 2016, 5–6, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nabulsi, K.M.; Rizk, T.Y.; Al-Abbas, F.M.; Dias, O.C. Sea Water Cooler Tubes Corrosion and Leaks Due to Microbiologically Induced Corrosion. In Proceedings of the NACE - International Corrosion Conference Series; 2016; Vol. 1; pp. 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, G.J.; Kain, V.; Dey, G.K. MIC Failure of Cupronickel Condenser Tube in Fresh Water Application. Eng Fail Anal 2009, 16, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttunen-Saarivirta, E.; Honkanen, M.; Lepistö, T.; Kuokkala, V.-T.; Koivisto, L.; Berg, C.-G. Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion (MIC) in Stainless Steel Heat Exchanger. Appl Surf Sci 2012, 258, 6512–6526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. Microbiological-Influenced Corrosion Failure of a Heat Exchanger Tube of a Fertilizer Plant. Journal of Failure Analysis and Prevention 2014, 14, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.C. Standards of the Tubular Exchanger Manufacturers Association. 2019, 1–3.

- ASTM E3-11; Standard Guide for Preparation of Metallographic Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- ASTM A790/A790M-22; Standard Guide for Preparation of Metallographic Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Millero, F.J.; Huang, F. The Density of Seawater as a Function of Salinity (5 to 70 g Kg -1) and Temperature (273.15 to 363.15 K). Ocean Science 2009, 5, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, B.M.; Haber, M.J.; Dejong, J.T.; Caslake, L.F.; Nelson, D.C. Effects of Environmental Factors on Microbial Induced Calcium Carbonate Precipitation. J Appl Microbiol 2011, 111, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huttunen-Saarivirta, E.; Rajala, P.; Marja-aho, M.; Maukonen, J.; Sohlberg, E.; Carpén, L. Ennoblement, Corrosion, and Biofouling in Brackish Seawater: Comparison between Six Stainless Steel Grades. Bioelectrochemistry 2018, 120, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, S. Preferential Dissolution Mechanism of α or γ Phase in Crevice Corrosion of Duplex Stainless Steels. Zairyo to Kankyo/ Corrosion Engineering 2016, 65, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machuca, L.L.; Bailey, S.I.; Gubner, R.; Watkin, E.L.J.; Ginige, M.P.; Kaksonen, A.H.; Heidersbach, K. Effect of Oxygen and Biofilms on Crevice Corrosion of UNS S31803 and UNS N08825 in Natural Seawater. Corros Sci 2013, 67, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revie, R.W. Uhlig’s Corrosion Handbook: Third Edition; 2011.

- Blackwood, D.J.; Lim, C.S.; Teo, S.L.M.; Hu, X.; Pang, J. Macrofouling Induced Localized Corrosion of Stainless Steel in Singapore Seawater. Corros Sci 2017, 129, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papavinasam, S. Chapter 6 - Modeling – Internal Corrosion. In Corrosion Control in the Oil and Gas Industry; Papavinasam, S., Ed.; Gulf Professional Publishing: Boston, 2014; pp. 301–360. ISBN 978-0-12-397022-0. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, R.N. 1 - Developments, Grades and Specifications. In Duplex Stainless Steels; Gunn, R.N., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing, 1997; pp. 1–13 ISBN 978-1-85573-318-3.

- Makhlouf, A.S.H.; Botello, M.A. Chapter 1 - Failure of the Metallic Structures Due to Microbiologically Induced Corrosion and the Techniques for Protection. In Handbook of Materials Failure Analysis; Makhlouf, A.S.H., Aliofkhazraei, M., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann, 2018; pp. 1–18 ISBN 978-0-08-101928-3.

- Schütze, M. Corrosion Books: Handbook of Corrosion Engineering. By Pierre R. Roberge - Materials and Corrosion 4/2002. Materials and Corrosion 2002, 53, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).