Submitted:

22 May 2023

Posted:

23 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Webster, P.J. Heusler alloys. Contemp. Phys. 1969, 10, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heczko, O.; Seiner, H.; S Fähler, S. Coupling between ferromagnetic and ferroelastic transitions and ordering in Heusler alloys produces new multifunctionality. MRS Bull. 2022, 47, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabe, S.; Niemann, R.; Backen, A.; Wolf, D.; Damm, C.; Walter, T.; Seiner, H.; Heczko, O.; Nielsch, K.; Fähler, S. Building hierarchical martensite. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2005715(1)–2005715(10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemann, R.; Rößler, U.K.; Gruner, M.E.; Heczko, O.; Schultz, L.; Fähler, S. The role of adaptive martensite in magnetic shape memory alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2012, 14, 562–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibel, F.; Gottschall, T.; Taubel, A.; Fries, M.; Skokov, K.P.; Terwey, A.; Keune, W.; Ollefs, K.; Wende, H.; Farle, M.; Acet, M.; Gutfleisch, O.; Gruner, M.E. Hysteresis design of magnetocaloric materials—from basic mechanisms to applications. Energy Technol. 2018, 6, 1397–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heczko, O.; Scheerbaum, N.; Gutfleisch, O.; Liu, J.P.; Fullerton, E.; Gutfleisch, O.; Sellmyer, D.J. Magnetic shape memory phenomena. In Nanoscale Magnetic Materials and Applications, 1st ed., Liu J.P., Fullerton E., Gutfleisch O., Sellmyer D.J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 399–439.

- Sozinov, A.; Lanska, N.; Soroka, A.; Zou, W. 12% magnetic field-induced strain in Ni-Mn-Ga-based non-modulated martensite. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 021902(1)–021902(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heczko, O.; Sozinov, A.; Ullakko, K. Giant field-induced reversible strain in magnetic shape memory NiMnGa alloy. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2000, 36, 3266–3268. [Google Scholar]

- Saren, A.; Musiienko, D.; Smith, A.R.; Tellinen, J.; Ullakko, K. Modeling and design of a vibration energy harvester using the magnetic shape memory effect. Smart Mater. Struct. 2015, 24, 095002(1)–095002(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsangi, M.A.A.; Cottone, F.; Sayyaadi, H.; Zakerzadeh, M.R.; Orfei, F.; Gammaitoni, L. Energy harvesting from structural vibrations of magnetic shape memory alloys. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 103905(1)–103905(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozinov, A.; Lanska, N.; Soroka, A.; Straka, L. Highly mobile type II twin boundary in Ni-Mn-Ga five-layered martensite. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 124103(1)–124103(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiienko, D.; Nilsén, F.; Armstrong, A.; Rameš, M.; Veřtát, P.; Colman, R.H.; Čapek, J.; Müllner, P.; Heczko, O.; Straka, L. Effect of crystal quality on twinning stress in Ni-Mn-Ga magnetic shape memory alloys, J. Mater. Res. Technol-JMRT, 2021, 14, 1934–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straka, L.; Sozinov, A.; Drahokoupil, J.; Kopecký, V.; Hänninen, H.; Heczko, O. Effect of intermartensite transformation on twinning stress in Ni-Mn-Ga 10M martensite. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 114, 063504(1)–063504(7). [Google Scholar]

- Heczko, O.; Kopecký, V.; Sozinov, A.; Straka, L. Magnetic shape memory effect at 1.7 K. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 103, 072405(1)–072405(4). [Google Scholar]

- Pagounis, E.; Chulist, R.; Szczerba, M.J.; Laufenberg, M. High-temperature magnetic shape memory actuation in a Ni–Mn–Ga single crystal. Scr. Mater. 2014, 83, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Vronka, M.; Straka, L.; Klementová, M.; Palatinus, L.; Veřtát, P.; Sozinov, A.; Heczko, O. Unexpected modulation revealed by electron diffraction in Ni–Mn–Ga–Co–Cu tetragonal martensite exhibiting giant magnetic field- induced strain. Scr. Mater. 2023, submitted. [CrossRef]

- Heczko, O.; Straka, L. Compositional dependence of structure, magnetization and magnetic anisotropy in Ni–Mn–Ga magnetic shape memory alloys. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2004, 272, 2045–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koho, K.; Söderberg, O.; Lanska, N.; Ge, Y.; Liu, X.; Straka, L.; Vimpari, J.; Heczko, O.; Lindroos, V.K. Effect of the chemical composition to martensitic transformation in Ni–Mn–Ga–Fe alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A-Struct. Mater. Prop. Microstruct. Process. 2004, 378, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Parra, D.E.; Moya, X.; Mañosa, L.; Planes, A.; Flores-Zúñiga, H.; Alvarado-Hernández, F.; Ochoa-Gamboa, R.A.; Matutes-Aquino, J.A.; Ríos-Jara, D. Fe and Co selective substitution in Ni2MnGa: Effect of magnetism on relative phase stability. Philos. Mag. 2010, 90, 2771–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanomata, T.; Kitsunai, Y.; Sano, K.; Furutani, Y.; Nishihara, H.; Umetsu, R.Y.; Kainuma, R.; Miura, Y.; Shirai, M. Magnetic properties of quaternary Heusler alloys Ni2-xCoxMnGa. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 214402(1)–214402(6). [Google Scholar]

- Namvari, M.; Chernenko, V.; Saren, A.; Porro, J.M.; Ullakko, K. Structure-property control of polycrystalline Ni–Mn–Ga by moderate Co-doping. J. Alloy. Compd. 2023, 944, 169184(1)–169184(7). [Google Scholar]

- Sakon, T.; Fujimoto, N.; Kanomata, T.; Adachi, Y. Magnetostriction of Ni2Mn1-xCrxGa Heusler alloys. Metals 2017, 7, 410(1)–410(13). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.M.; Khan, M.; Stadler, S.; Ali, N.; Dubenko, I.; Takeuchi, A.Y.; Guimarães, A.P. Magnetocaloric properties of the Ni2Mn1-x(Cu,Co)xGa Heusler alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 99, 08Q106(1)–08Q106(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, Y.; Kouta, R.; Fujio, M.; Kanomata, T.; Umetsu, R.Y.; Xu, X.; Kainuma, R. Magnetic phase diagram of Heusler alloy system Ni2Mn1-xCrxGa. Physics Procedia 2015, 75, 1187–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yoshida, Y.; Omori, T.; Kanomata, T.; Kainuma, R. Magnetic properties and phase diagram of Ni50Mn50-xGax/2Inx/2magnetic shape memory alloys. Shape Mem. Superelasticity 2016, 2, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanomata, T.; Shirakawa, K.; Kaneko, T. Effect of hydrostatic pressure on the Curie temperature of the Heusler alloys Ni2MnZ (Z = Al, Ga, In, Sn and Sb). J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1987, 65, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Giri, S.; De, S.K.; Majumdar, S. Giant magneto-caloric effect near room temperature in Ni–Mn–Sn–Ga alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 2010, 503, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Giri, S.; Majumdar, S.; De, S.K.; Koledov, V.V. Effect of Sn doping on the martensitic and premartensitic transitions in Ni2MnGa. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2012, 324, 1891–1896. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, A.; Nilsén, F.; Rameš, M.; Colman, R.H.; Veřtát, P.; Kmječ, T.; Straka, L.; Müllner, P.; Heczko, O. Systematic trends of transformation temperatures and crystal structure of Ni-Mn-Ga-Fe-Cu alloys. Shape Mem. Superelasticity 2020, 6, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiner, H.; Zelený, M.; Sedlák, P.; Straka, L.; Heczko, O. Experimental observations versus first-principles calculations for Ni–Mn–Ga ferromagnetic shape memory alloys: a review. Phys. Status Solidi-Rapid Res. Lett. 2022, 16, 2100632(1)–2100632(19). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecký, V.; Rameš, M.; Veřtát, P.; Colman, R.H.; Heczko, O. Full variation of site substitution in Ni-Mn-Ga by ferromagnetic transition metals. Metals 2021, 11, 850(1)–850(18). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikazumi, S. Physics of ferromagnetism, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press Inc.: New York, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.; Marioni, M.; Bono, D.; Allen, S.M.; O’Handley, R.C.; Hsu, T.Y. Empirical mapping of Ni-Mn-Ga properties with composition and valence electron concentration. J. Appl. Phys. 2002, 91, 8222–8224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entel, P.; Buchelnikov, V.D.; Khovailo, V.V.; Zayak, A.T.; Adeagbo, W.A.; Gruner, M.E.; Herper, H.C.; Wassermann, E.F. Modelling the phase diagram of magnetic shape memory Heusler alloys. J. Phys. D-Appl. Phys. 2006, 39, 865–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

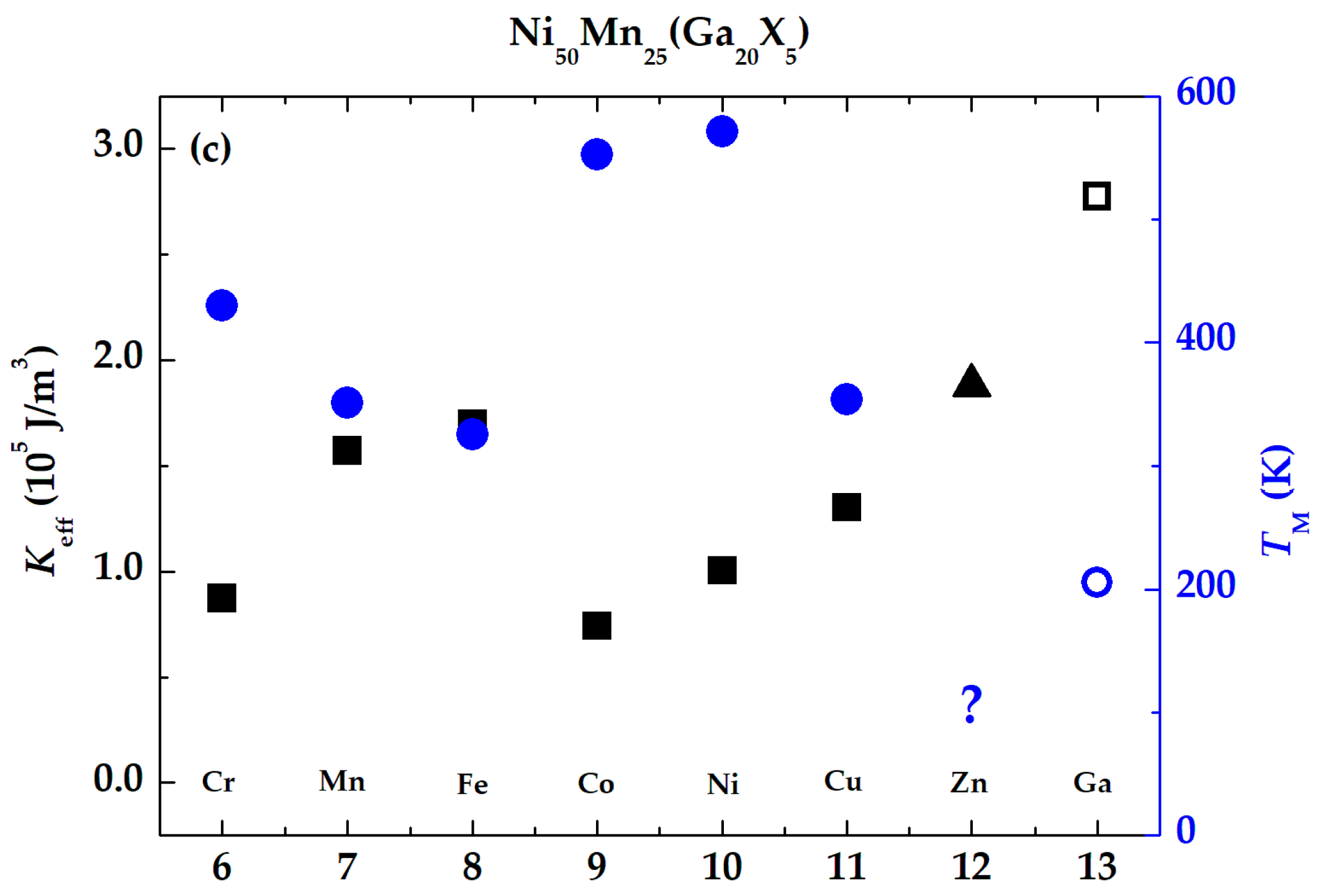

- Rameš, M.; Kopecký, V.; Heczko, O. Compositional dependence of magnetocrystalline anisotropy in Fe–, Co–, and Cu–alloyed Ni–Mn–Ga. Metals 2022, 12, 133(1)–133(8). [Google Scholar]

- Haschke, M. Quantification. In Laboratory Micro-X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 157–199. [Google Scholar]

- Koho, K.; Söderberg, O.; Lanska, N.; Ge, Y.; Liu, X.; Straka, L.; Vimpari, J.; Heczko, O.; Lindroos, V.K. Effect of the chemical composition to martensitic transformation in Ni–Mn–Ga–Fe alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A-Struct. Mater. Prop. Microstruct. Process. 2004, 378, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushin, V.; Kuranova, N.; Marchenkova, E.; Pushin, A. Design and development of Ti–Ni, Ni–Mn–Ga and Cu–Al–Ni-based alloys with high and low temperature shape memory effects. Materials 2019, 12, 2616(1)–2616(24). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.S.; Ramudu, M.; Seshubai, V. Effect of selective substitution of Co for Ni or Mn on the superstructure and microstructural properties of Ni50Mn29Ga21. J. Alloy. Compd. 2011, 509, 8215–8222. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, D.; Hernández, F.A.; Flores-Zúñiga, H.; Moya, X.; Mañosa, L.; Planes, A.; Aksoy, S.; Acet, M.; Krenke, T. Phase diagram of Fe-doped Ni-Mn-Ga ferromagnetic shape-memory alloys. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 184103(1)–184103(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Q.; Lu, X.; Wang, D.Y.; Qin, Z.X. The effect of Co-doping on martensitic transformation temperatures in Ni–Mn–Ga Heusler alloys. Smart Mater. Struct. 2008, 17, 065030(1)–065030(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belosludtseva, E.S.; Kuranova, N.N.; Marchenkova, E.B.; Popov, A.G.; Pushin, V.G. Effect of gallium alloying on the structure, the phase composition, and the thermoelastic martensitic transformations in ternary Ni–Mn–Ga alloys. Tech. Phys. 2016, 61, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, T.; Felser, C.; Parkin, S.S.P. Simple rules for the understanding of Heusler compounds. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2011, 39, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramudu, M.; Kumar, A.S.; Seshubai, V.; Rajasekharan, T. Correlation of martensitic transformation temperatures of Ni–Mn–Ga/Al–X alloys to non-bonding electron concentration. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 73, 012074(1)–012074(5). [Google Scholar]

- Miedema, A.; de Châtel, P.F.; de Boer, F.R. Cohesion in alloys-fundamentals of a semi-empirical model. Physica B 1980, 100, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayila, S.K.; Machavarapu, R.; Vummethala, S. Site preference of magnetic atoms in Ni–Mn–Ga–M (M = Co, Fe) ferromagnetic shape memory alloys. Phys. Status Solidi B–Basic Solid State Phys. 2011, 249, 620–626. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.M.; Luo, H.B.; Hu, Q.M.; Yang, R.; Johansson, B.; Vitos, L. Site preference and elastic properties of Fe–, Co–, and Cu–doped Ni2MnGa shape memory alloys from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 024206(1)–024206(10). [Google Scholar]

- Webster, P.J.; Ziebeck, K.R.A.; Town, S.L.; Peak, M.S. Magnetic order and phase transformation in Ni2MnGa. Philos. Mag. B–Phys. Condens. Matter Stat. Mech. Electron. Opt. Magn. Prop. 1984, 49, 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Enkovaara, J.; Heczko, O.; Ayuela, A.; Nieminen, R.M. Coexistence of ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic order in Mn-doped Ni2MnGa. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 67, 212405(1)–212405(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasil’ev, A.N.; Bozhko, A.D.; Khovailo, V.V.; Dikshtein, I.E.; Shavrov, V.G.; Buchelnikov, V.D.; Matsumoto, M.; Suzuki, S.; Takagi, T.; Tani, J. Structural and magnetic phase transitions in shape-memory alloys Ni2+xMn1-xGa. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janovec,J. ; Straka, L.; Sozinov, A.; Heczko, O.; Zelený, M. First-principles study of Zn-doping effects on phase stability and magnetic anisotropy of Ni-Mn-Ga alloys. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 026101(1)–026101(11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, J.C. The ferromagnetism of nickel. II. Temperature effects. Phys. Rev. 1936, 49, 931–937. [Google Scholar]

- Pauling, L. The nature of the interatomic forces in metals. Phys. Rev. 1938, 54, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Okamoto, T. Fukuda, T. Kakeshita, T. Takeuchi: Magnetocrystalline anisotropy constant and twinning stress in martensite phase of Ni-Mn-Ga. Mater. Sci. Eng. A –Struct. Mater. Prop. Microstruct. Process. 2006, 438, 948–951. [Google Scholar]

- Tickle, R.; James, R.D. Magnetic and magnetomechanical properties of Ni2MnGa. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1999, 195, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rameš, M.; Heczko, O.; Sozinov, A.; Ullakko, K.; Straka, L. Magnetic properties of Ni–Mn–Ga–Co–Cu tetragonal martensites exhibiting magnetic shape memory effect. Scr. Mater. 2018, 142, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkovaara, J.; Ayuela, A.; Nordström, L.; Nieminen, R.M. Magnetic anisotropy in Ni2MnGa. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 65, 134422(1)–134422(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namvari, M.; Laitinen, V.; Sozinov, A.; Saren, A.; Ullakko, K. Effects of 1 at.% additions of Co, Fe, Cu, and Cr on the properties of Ni–Mn–Ga–based magnetic shape memory alloys. Scr. Mater. 2023, 224, 115116(1)–115116(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

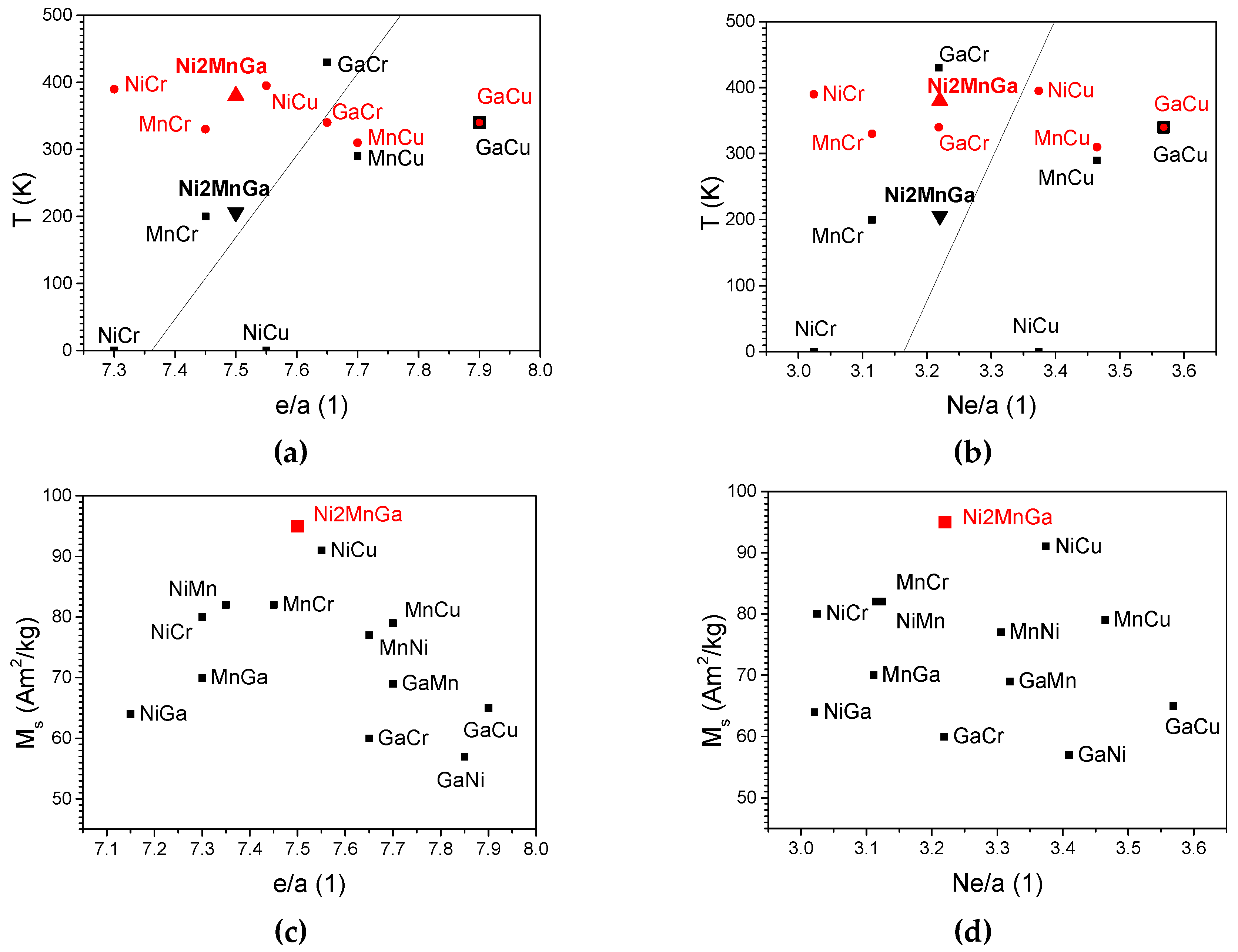

| Composition at.% |

Marking (deficient-excess) |

e/a | Ne/a | Structure at r.t. | Ms at 10 K (Am2/kg) | TC (K) | TM (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni50Mn20Cr5Ga25 | MnCr | 7.45 | 3.11 | A | 82 | 330 | 200 |

| Ni45Cr5Mn25Ga25 | NiCr | 7.30 | 3.02 | A | 80 | 390 | - |

| Ni50Mn25Ga20Cr5 | GaCr | 7.65 | 3.22 | NM | 60 | 340 | 430 |

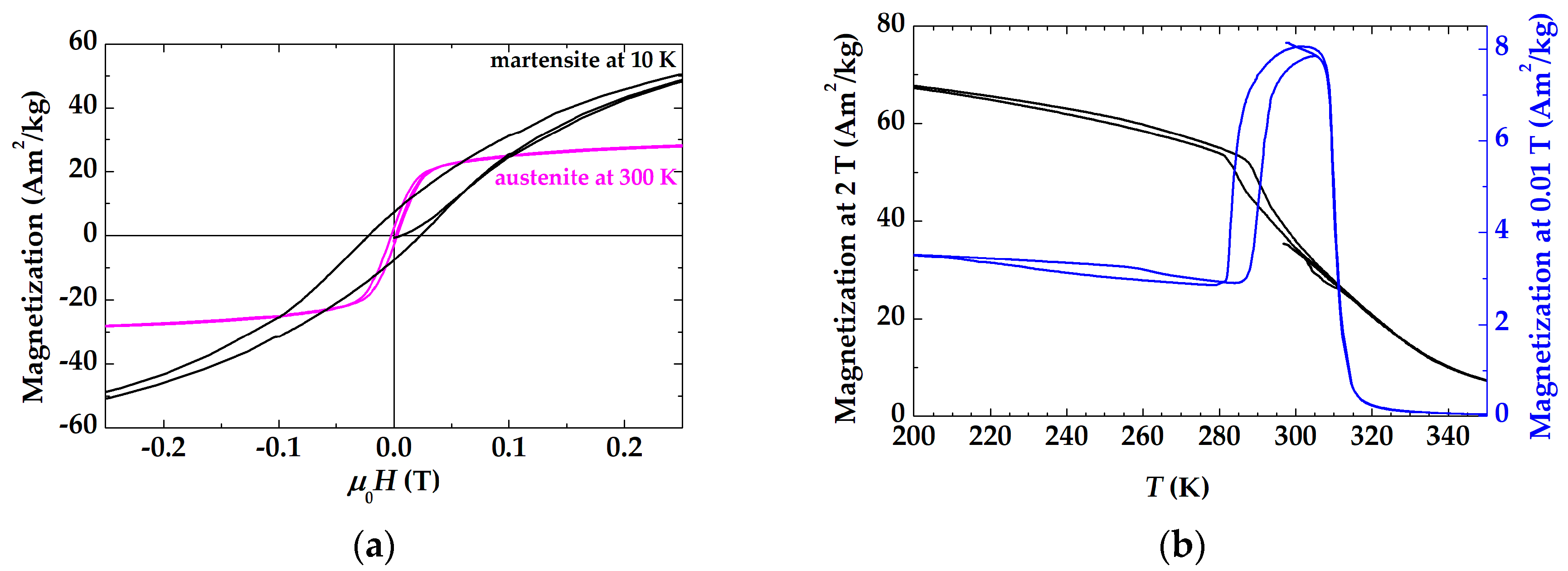

| Ni50Mn20Cu5Ga25 | MnCu | 7.70 | 3.46 | A | 79 | 310 | 290 |

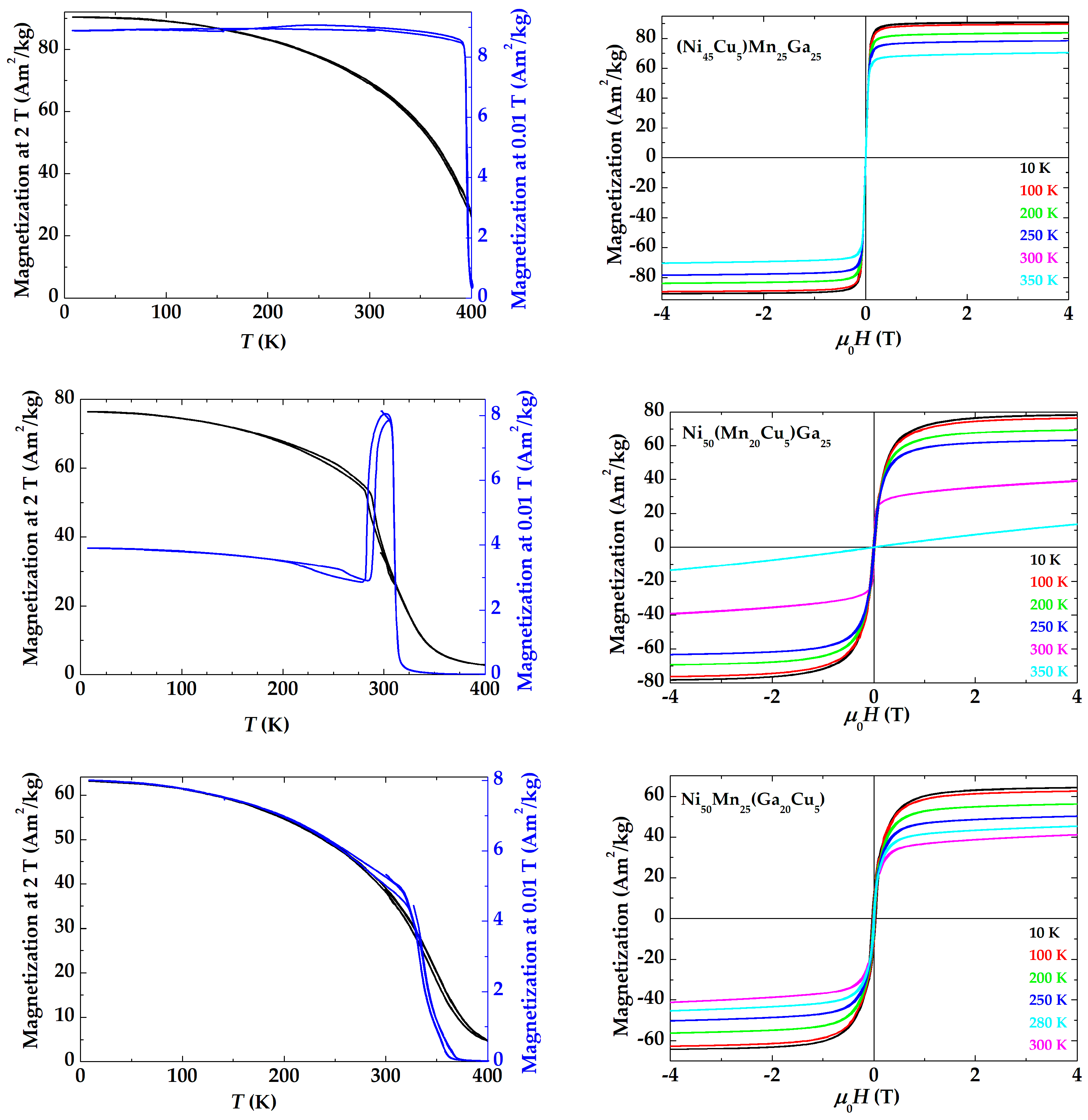

| Ni45Cu5Mn25Ga25 | NiCu | 7.55 | 3.37 | A | 91 | 395 | - |

| Ni50Mn25Ga20Cu5 | GaCu | 7.90 | 3.57 | NM | 65 | 340 | 340 |

| Ni50Mn20Ga30 | MnGa | 7.30 | 3.11 | A | 70 | 300 | - |

| Ni45Mn25Ga30 | NiGa | 7.15 | 3.02 | A | 64 | 300 | - |

| Ni45Mn30Ga25 | NiMn | 7.35 | 3.12 | A | 82 | 400 | 90 |

| Ni50Mn30Ga20 | GaMn | 7.70 | 3.32 | NM | 69 | 360 | 340 |

| Ni55Mn25Ga20 | GaNi | 7.85 | 3.41 | NM | 57 | 325 | 571 |

| Ni55Mn20Ga25 | MnNi | 7.65 | 3.31 | NM | 77 | 373 | 373 |

| Ni50Mn25Ga25* | Ni2MnGa | 7.50 | 3.22 | A | 95 | 380 | 206 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).