1. Introduction

Ocean circulation plays a crucial role in exchanging matter and energy within the ocean. It exerts significant influences on the distribution of marine life, air-sea interactions, and climate change. In the field of ocean spatiotemporal data modeling, it is inevitable to confront heterogeneous semantic issues due to various expressions of specific phenomena. This makes it difficult to effectively and efficiently express and integrate marine data. To address this issue, it is necessary to establish a systematic and structured expression system that can comprehensively describe ocean circulation at the conceptual level. Such a framework should provide coherent and consistent descriptions across different scales to facilitate seamless data fusion and modeling.

A shared conceptual basis and vocabulary are instrumental in synthesizing multidisciplinary knowledge about ocean circulation. They are also pivotal to developing parameterizations and rehabilitation modules to represent ocean circulation in climate and ecosystem models. Overall, a robust conceptual framework for clarifying the expression of ocean phenomena is imperative to improve the understanding of ocean circulation and predictive capability of the climate system. Bermudez[

1] et al outlined a specific methodology for creating and sharing marine ontologies based on controlled vocabularies in the Marine Metadata Interoperability Project(MMI). These ontologies ultimately make scientific data facile to be distributed, advertised, reused, and combined with other data sets. In 2006, Bermudez[

2] et al proposed a marine platforms ontology to delineate practical design ontology principles and presented an important platform terminology for European marine community. However, the interactions between concepts have not been specifically described and expressed. Chau[

3] presented an ontology-based KM system (KMS) that simulates human expertise during the problem solving by incorporating artificial intelligence and coupling various descriptive knowledge, procedural knowledge and reasoning knowledge involved in the coastal hydraulic and transport processes. Rueda[

4] et al described the MMI Ontology Registry and Repository and associated semantic services developed by the Marine Metadata Interoperability Project. Tao[

5] et al used the National Oceanography Centre Southampton’s Ferrybox project to set up an ontology based reference model of a Collaborative Ocean, where relevant oceanographic resources can be semantically annotated to produce Resource Description Framework (RDF) format metadata to facilitate data/resource interoperability in a distributed environment. Meanwhile, Yun [

6] proposed a knowledge engineering approach to build domain ontology by combining software development life cycle standard IEEE 1074-2006. And then they described marine biology ontology development process with Hozo in detail. The Biological and Chemical Oceanography Data Management Office(BCO-DMO) developed an ontology project to improve the interoperability of ocean biogeochemical data [

7]. Jia [

8] et al proposed an ontology model using Hozone role theory, then an ontology about ocean carbon cycle was built to describe and share the basic knowledge of ocean carbon cycle. In 2017, Stocker[

9] conducted research on semantic representation of marine monitoring data, and demonstrated the application of the technological framework in experiments that integrate sensing data and metadata available by heterogeneous and distributed resources. Stephen[

10] et al analyzed basic flow processes in the hydrology domain and constructed a taxonomy of different flow patterns based on the differences between the source and goal participants. The taxonomy and related concepts are axiomatized in first-order logic as refinements of DOLCE’s participation relation and reuses hydrogeological concepts from the Hydro Foundational Ontology (HyFO). Poux[

11] et al presented an integrated 3D semantic reconstruction framework that leverages segmented point cloud data and domain ontologies. which adopted a part-to-whole conception that modeled a point cloud in parametric elements usable per instance and aggregated to obtain a global 3D model. During 2019, the All-Atlantic Ocean Observing System (AtlantOS) was promoted to establish a comprehensive ocean observation system for the Atlantic Ocean as a whole[

12]. The NZ marine science community used the OceanObs’19 white paper to establish a framework and plan for a collaborative NZ ocean observing system (NZ-OOS)[

13]. Ge[

14] et al proposed a forest fire prediction method that fuses multi-source heterogeneous spatio-temporal forest fire data by constructing a forest fire semantic ontology and a knowledge graph-based spatio-temporal framework. Regarding to the conceptual modeling of ocean circulation, particular efforts have been devoted by certain researchers. Ai [

15] et al proposed a method of selecting data points based on their importance to construct multi-scale representations of ocean circulation, which effectively retain flow-field characteristics. Li [

16] proposed a quadruple-based organization for ocean circulation features and performed a collaborative filtering method on the similarity of structural features in the ocean circulation which provides semantic support for the integration and management of spatiotemporal data in the ocean circulation. Ji [

17] et al constructed a three-tier architecture to realize the semantic expression of ocean flow domain knowledge. Based on Web Ontology Language (OWL) syntactic rules, they constructed spatiotemporal predicates and terms, extended OWL spatial-temporal modeling key nodes, and formed Ocean Current Spatial-temporal Web Ontology Language (OST OWL).

Given the powerfulness of ontology in conceptualizing and representing domain knowledge, this paper presents an ontological modeling and knowledge representation system for ocean circulation. Specifically, the conceptual knowledge and spatiotemporal characteristics of ocean circulation were firstly analyzed. The ontology was then formally expressed and articulated by using the Web Ontology Language (OWL). We have performed the reasoning and analysis over ontological relations. and provided sufficient cases to elaborate the ontological system. The resultant semantic expression system for ocean circulation ontology offers semantic foundations to manage the spatiotemporal data of ocean circulation.

3. Ocean circulation domain ontology construction

3.1. Definition of the ontology structure of ocean circulation

The ocean circulation is a complex system that exhibits diversity in motion across various spatial and temporal scales. It involves elements such as the namespace of ocean currents, geographical locations and time scales, as well as geographical factors like oceanic hydrology, meteorology, geological features, and environmental resources. Additionally, human factors like politics and economics are also important. Because of the heterogeneity of multi-source spatiotemporal data and differences in expressing relevant knowledge, it becomes challenging to directly achieve the data interoperability. Therefore, data standardization and conversion are necessary for effective sharing.

Ontology has been widespread developed in the information field, which provides an effective approach for sharing the knowledge, integrating the data and enabling new discovery. Its application in the field of geography has demonstrated its unique advantage in describing complex geographical knowledge. The core of ontology modeling is the precise definition of spatial data concepts, their attributes, constraint conditions, and the hierarchical relationships between concepts within a given domain. At present, many researchers have proposed models such as triples[

29,

30], quadruples[

31], quintuples[

32] and sextuples[

33] to express geographical ontologies. These models offer an effective means for integrating geographical concepts and relational rules within the geographical domain. Particularly, the triplet model is an abstract form of ontology modeling that is limited in describing detailed ontology information. The quintuple model separates the attributes and emphasizes their importance. The sextuple model provides a more specific classification of attributes and relationships, but this increased specificity may lead to a decrease for its applicability.

As an integral component of geographical information, the ocean exhibits not only numerous geographical features but also distinct characteristics such as high dimensionality, high dynamics, and complex materialization. Based on the concept of geographical ontology and incorporating the existing logical structure of geographical ontology, it is believed that the quintuple model is sufficient to meet the requirements for representing the ocean circulation ontology.

In equation(1), ‘C’ denotes the set of definitions for concepts in the ocean circulation. ‘R’ represents various relationships within ocean circulation, including those relationships between concepts, between concepts and attributes, between attributes, and between concepts and instances. ‘P’ represents the attribute characteristics of ocean circulation. ‘A’ conveys the recognized laws, knowledge, and rules or constraint conditions imposed on concepts in geography. For instance, in the context of ocean circulation, it is widely accepted that the spatial distance cannot be negative. ‘I’ denotes the set of instances of ocean circulation.

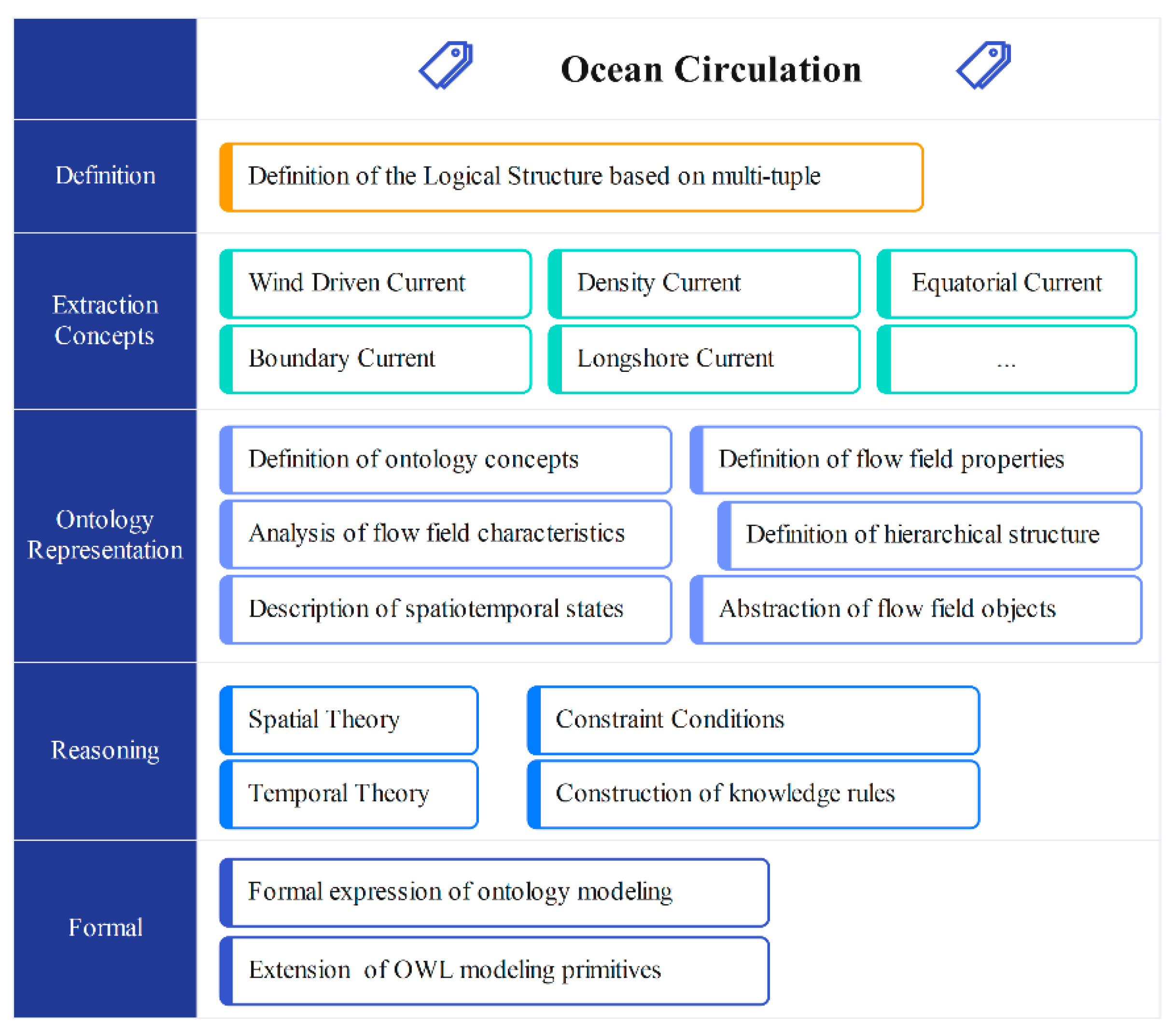

In our work, we have improved Noy's seven-step method[

34] for ontology modeling to achieve the ontology modeling of ocean circulation. Figure 1 shows the process of constructing ocean circulation ontology. The specific steps are as follows:

Step 1: Determine the purpose and scope of ontology for ocean circulation, and clearly define the concepts, properties, and relationships within this domain to meet the requirements for the semantic level.

Ocean circulation encompasses the intricate relationships among ocean currents, marine environments, oceanography, and marine economics. The formal representation of ocean circulation has been defined as a focused domain, specifically targeting the definition and spatiotemporal processes associated with ocean circulation. The purpose of ontology development is to establish a computer- interpretable knowledge sharing and management system for ocean circulation. This system aims to provide a robust platform to support marine scientific research and foster collaboration.

Step 2: Analyze the existing concepts and relationship descriptions of ocean circulation, and create an ocean circulation knowledge base. Creating a knowledge base involves to reference marine science, international standards, professional books, databases, research reports, etc. This entails to clarify specific concepts and their interrelationships involved in this field, enabling the reuse of domain knowledge. Specifically, when constructing the knowledge base of ocean circulation, it is essential to seek the assistance of marine experts to ensure the accuracy and precision in the experiment.

Step 3: Analyze the listed concepts and relationship systems, and define the concepts, relationships, properties, and constraint conditions within ocean circulation ontology.

In this step, it is necessary to extract the terminology associated with ocean circulation and determine the unanimously approved domain concept. It is important to acknowledge that, prior to conceptualization, we must determine the depth of the conceptual level and establish the development naming convention. Additionally, the semantic relationships during the spatiotemporal development of ocean circulation should be examined. Similarly, in this process, we rely on marine experts to ensure precise descriptions and conduct thorough analysis. We will elaborate these aspects further in

Section 3.2.

Step 4: Formally describe the ontology of ocean circulation.

In this step, the OWL language is utilized along with the Protégé software platform to create concepts, properties, instances, and relationships related to ocean circulation. This step is to finalize the formal representation of the ocean circulation ontology. A detailed introduction will be presented in

Section 3.3.

Step 5: Validate the adequacy of the ontology in describing various data, and ensure the effectiveness of ocean circulation ontology.

The ontology is expanded and enhanced based on the evaluation and analysis results. In reality, ontology construction follows a spiral approach, involving iterative and incremental processes aimed at continual improvement.

Step 6: Create an instance of ocean circulation ontology.

This step involves actively creating ontology instances and establish associations with the corresponding entries in the database.

Figure 1.

The process of constructing ocean circulation ontology.

Figure 1.

The process of constructing ocean circulation ontology.

3.2. Analysis of spatial-temporal process semantics

Considering the complexity of spatiotemporal processes in the ocean circulation, by leveraging the existing ontology knowledge, we will define the concepts of ocean circulation, and analyze the relationships between these concepts, including spatiotemporal relationships and property relationships. Furthermore, we will devote into the construction of semantic inference rules for ocean circulation.

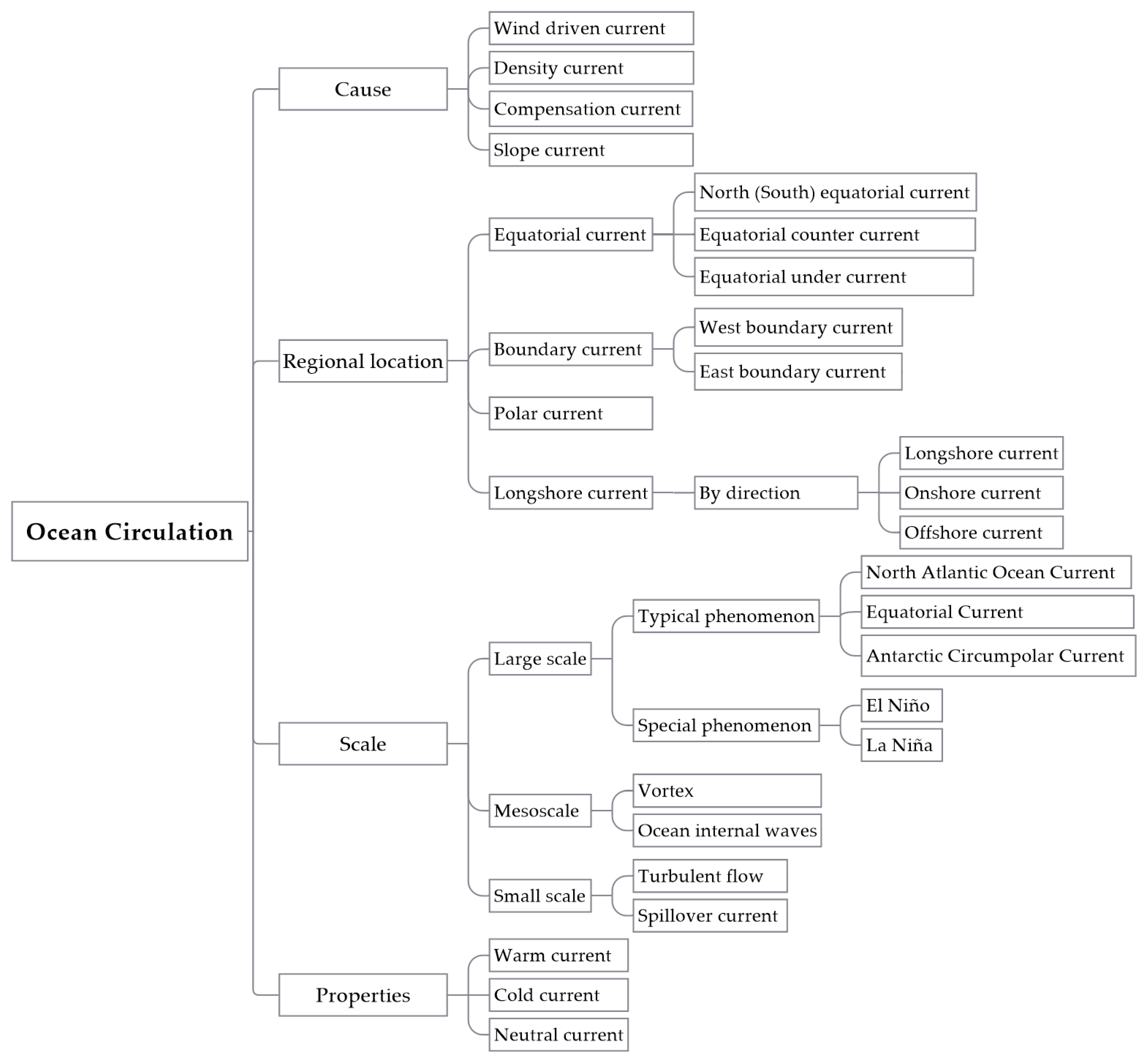

3.2.1. Analysis of semantic concepts

The movement of seawater in the ocean involves large-scale horizontal or vertical motion between different sea regions at various scales and speeds. It is a complex interplay of various phenomena, including the turbulence, waves, periodic tides, and stable ‘constant flow’. We aim to conceptualize the definitions related to ocean current phenomena by consulting resources such as the “Classification Method of Marine Science Literature”, professional marine science books, academic papers, and the Internet. This will help to establish a hierarchical structure for ocean circulation ontology. A class hierarchy can be constructed through top-down, bottom-up, or a combination of both approaches. The specific structure of the hierarchy is determined by the intended purpose and scope of the ontology. We will define the hierarchical structure of the semantic concepts of the ocean circulation from aspects such as regional location, cause, scale, and properties. as shown in Figure 2.

The ocean circulation is a vast and intricate conceptual system. From different classification perspectives, various structures for ocean circulation ontology can be proposed. Ocean currents can be classified as warm, cold, or neutral based on their thermal properties. From a regional perspective, ocean currents exhibit varying characteristics due to the influence of the terrain, temperature, and salinity. As such, they can be categorized as equatorial, boundary, polar, or coastal currents. The formation of ocean circulation is influenced by the wind, temperature, salinity, Earth’s rotation, seabed topography and so on. These factors interact together to determine the flow formation and evolution, which allows to classify the wind-driven, density, slope, and compensation currents. The ocean circulation is affected by factors such as coastal terrain, wind forces above the sea surface, seawater density, and the Coriolis force, which introduces the characteristic phenomena under various scales and sizes. Thus, from the scale perspective, ocean circulation can be divided into large-scale, mesoscale, and small-scale by encompassing both spatial and temporal elements.

Figure 2.

Building a hierarchical concepts ontology of ocean circulation.

Figure 2.

Building a hierarchical concepts ontology of ocean circulation.

In the semantic construction of ocean circulation, based on the semantic construction criteria of ontology, a conceptual hierarchical structure of ocean circulation is established to further complete the spatiotemporal reasoning and information retrieval of ocean circulation information. From a conceptual level, it can be divided into those relationships between concepts, relationships between concepts and attributes, and relationships between concepts and instances, as shown in

Table 1.

The basic conceptual relationships of ocean currents have been discussed above. Through an extensive review of previous literature[

35,

36,

37,

38,

39], five semantic relationships are selected: oc_exact, oc_subclass, oc_supclass, oc_null, oc_overlap. The prefix ’oc_’ indicates that the concept relationships is about ocean circulation. The former four relationships are relatively straightforward to be clarified. The relationship of oc_overlap is used to indicate that two concepts are semantically related, but each concept has its uniqueness part that another concept does not have. To some extent, ‘oc_overlap’ indicates that two concepts are semantically related regardless of similarity degree[

39].

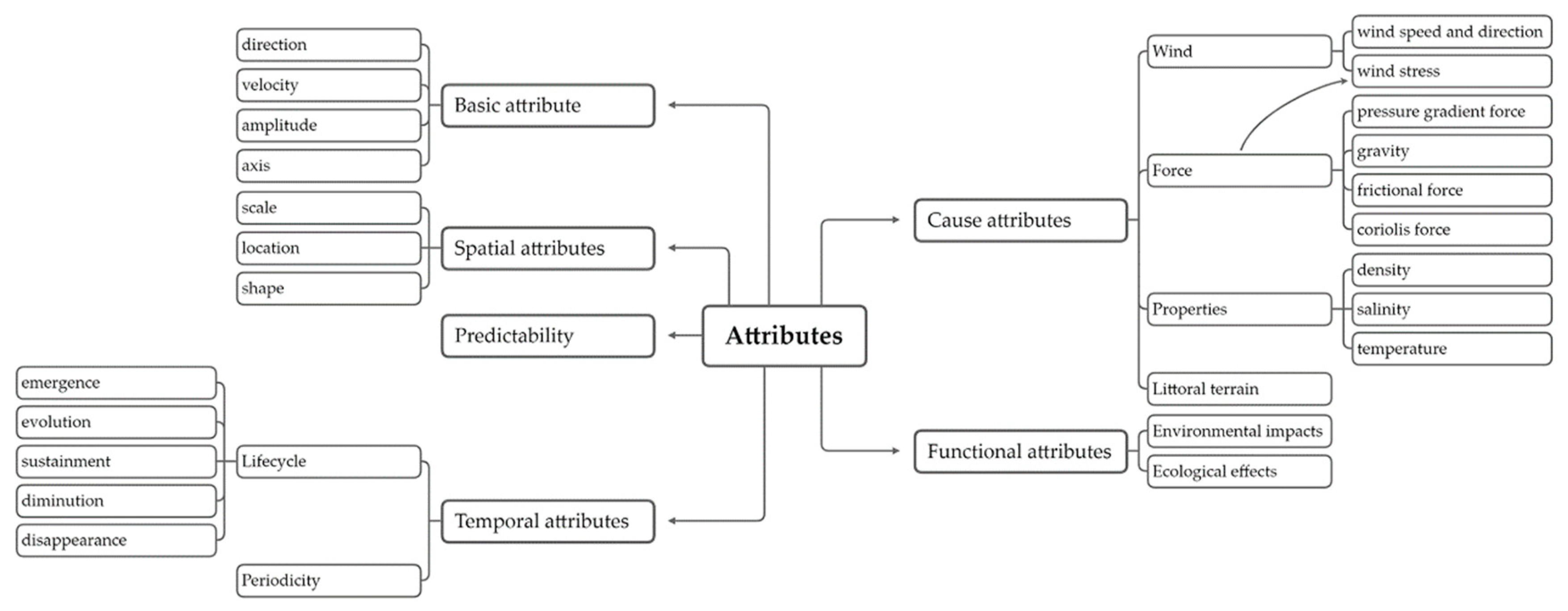

Another key point is the expression of ocean attributes. Ocean currents have multi-dimensional attributes[

40]. These include basic motion attributes such as flow direction and speed, as well as scalar field attributes like temperature, pressure, and density. Additionally, there are semantic attributes related to time and space. This article categorizes the attributes of ocean currents into basic, spatial, temporal, causal, functional, and predictability, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Semantic attributes of ocean circulation.

Figure 3.

Semantic attributes of ocean circulation.

3.2.2. Spatial semantic ontology

The spatial position, shape, and scale are all important attributes to provide a complete description of ocean currents. Spatial position refers to the geographic location of the current and can be either qualitative or quantitative. Qualitative positions are broad and vague, while quantitative positions can be precisely represented on a map using the latitude and longitude coordinates. The spatial shape of ocean currents reflects their state within their environment and is typically two-dimensional. Spatial scale measures the size of the current and includes concepts such as length, width, height, area, and volume. Overall, these three spatial attributes of ocean currents are interconnected and influence each other to unveil the information about the current’s spatial characteristics. Here we divide the spatial relationships of ocean circulation into three parts: spatial distance relationships, spatial sequence relationships, and spatial topological relationships[

41].

- 1.

Spatial distance relationships

Distance relationships can express the relative position and closeness of spatial entities, which reflects the potential for interaction and exchange between neighboring objects in space. Quantitative relationships typically disregard the target size and are calculated by Euclidean distance as shown below.

In equation (2), and represent the coordinates of two objective points respectively.

When building an ontology, the threshold for metric relationships is determined by the specific situation, which allows for a conversion between qualitative and quantitative expressions. In this article, the threshold set is defined as . The relationship between and can be expressed as

- 2.

Spatial sequence relationships

The sequential relationship, also known as a positional or extensional relationship, defines the relative orientation of geographical objects. Many scholars have proposed three-dimensional positional relationship models such as 3DR7[

42], 3DR27[

43], and 3DR39[

44]. However, given the unique characteristics of marine science data, these existing models do not account for internal positional relationships and are unable to express the specific positional relationship between two intersecting objects in space. Additionally, they are unable to express positional relationships in terms of depth (3DR44[

45], 3DR46[

46]).

In this article, the ocean circulation is considered as a planar entity and only external positional relationships are taken into account, rather than expanding on specific internal positional relationships. The positional relationship of ocean circulation is established by assuming P as the original target and

as a point of target P. Similarly, Q is the reference target and

is a point of Q.

(

,

) represents the angle between points

and

.

(

,

) represents the angle (north, south) deviating eastward.

(

,

) represents the angle between the direction line and the plane. The sequence relationship can be depicted in

Table 2.

- 3.

Spatial topological relationships

Spatial topology describes and analyzes the relative positions and relationships between geographical objects in space. It is a qualitative spatial relationship that includes the connectivity, adjacency, containment, intersection, nesting, mutual exclusion, and overlap[

47]. The analysis of spatial topological structures helps to understand the organizational patterns and operational mechanisms of geographical space and is an important aspect of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and spatial analysis, such as established models include the RCC topological relationship model[

48] and the N-intersection topological relationship model[

49,

50]. Based on point set topology, Egenhofer M.J. and others developed the 4-intersection and 9-intersection models[

51]. Based on the 9-intersection model and basic topological structure, the expression of three-dimensional topological relationships is shown in equation (4).

where and denote the internal point sets of their respective sets. The boundary point sets correspond to and , respectively. and also represent the external point sets of their respective sets.

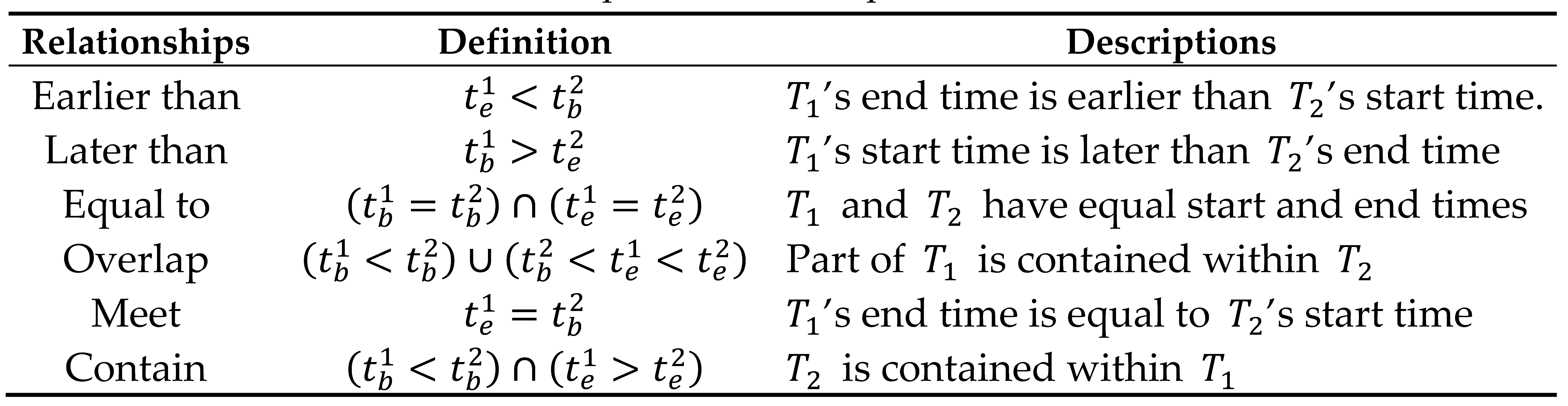

3.2.3. Temporal semantic ontology

Time constitutes an essential dimension in the spatiotemporal dynamics of ocean circulation, as their development exhibits lifecycle characteristics. To depict geographic space, the time can be expressed through time granularity, which captures both time scale and absolute time snapshot. Thus, the semantic ontology of ocean currents by combining time ontology with aspects such as time granularity and relationships denotes a venture that warrants effort.

Time granularity specifies the precision level in time descriptions. Depending on the duration of an event, it can be divided into units such as years, months, days, hours, minutes, and seconds. Alternatively, it can be divided into seasonal (spring, summer, autumn, winter) or solar divisions.

When considering time relationships in the context of current lifecycles, it is important to account for both time points and periods. Three relationships can be established based on the time points at which different currents occur: earlier than, later than, and equal to. For instance, ocean current ‘A’ may occur earlier than ocean current ‘B’. Time relationships can be expressed in various ways, ie. Allen’s interval algebra theory[

52]. By comparing the relationships between the endpoints of two time periods, 13 time relationships can be derived. Given events

T1 and

T2, where

and

,

and

denote the commencement and termination of

T1 and

T2 respectively, the temporal relationships in ocean circulation can be conceptualized as illustrated in the following

Table 3.

Table 3.

The temporal relationships of ocean circulation.

Table 3.

The temporal relationships of ocean circulation.

3.2.4. Semantic inference analysis of ocean circulation

To enhance data retrieval efficiency by accessing implicit knowledge within an ontology, it is typical to utilize knowledge rules that are based on the ontology knowledge system or the expression of ontology concepts and relationships. This enables semantic reasoning within ontology to discover implicit information. The former is based on describing ontology relationships to achieve semantic reasoning, while the latter formulates knowledge rules to expand ontology concepts and discover more implicit knowledge. Building upon these methods, we establish semantic inference rules and expression methods for ocean circulation by analyzing the semantic relationships within the spatiotemporal development of ocean circulation. These efforts improve the interoperability of spatiotemporal data in ocean circulation at a semantic level. In the following sections, we will discuss the semantic inference rules for ocean circulation from three perspectives: conceptual relationships, spatial relationships, and temporal relationships.

In section 3.1, we examined the interrelationships among various concepts related to ocean circulation. Then the semantic relationships of concepts in a tree-based ontology could be readily inferred based on the hierarchical structure of ocean current concepts that we have proposed (such as inheritance property of parent-child concepts). This hierarchical structure can be further expanded to infer semantic relationships between concepts from different ontologies. In the subsequent discussion, ‘A’ and ‘B’ denote different concept in ocean circulation ontology.

(1) If the semantic relationship between concepts A and B is oc_exat, these two concepts have the same meaning, and concept A shares the same semantic relationships with B.

(2) If the semantic relationship between concepts A and B is oc_subclass, concept A is a special type of concept B.

(3) If the semantic relationship between concepts A and B is oc_supclass, the semantic relationship between concept A's parents and concept B is oc_supclass.

(4) If the semantic relationship between concepts A and B is sem_null, then no new relationship can be inferred.

Therefore, the inference rules can be expressed as follows.

- 2.

Inference analysis of spatial relationships

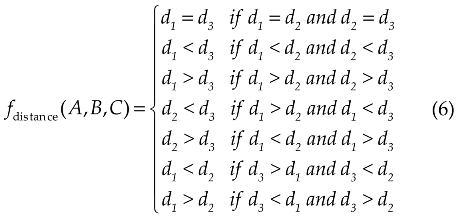

The determination of spatial semantic relationships in ocean circulation can take into account both spatial distance and spatial sequence relationships. We assume that ‘A’, ‘B’, and ‘C’ are three objects within the ocean circulation domain, with their respective distances defined as d1, d2, and d3 . From this point, we can draw the following conclusions shown in equation (6).

At the same time, if we assume that B is located at east of A and C lies east of B, then it could be inferred that C is located at east of A. Similarly, by combining the description of spatial sequence relationships, other spatial relationships can also be inferred.

- 3.

Inference analysis of temporal relationships

Time entities in ocean circulation include time point objects and time period objects. With regard to time point entities, time point objects , and are introduced, then the following relationships can be derived.

As for time period entities, temporal semantic relationships are typically determined by examining the start and end times of time objects. Based on previous analyses of temporal semantic relationships, a time period object is introduced, with start and end time denoted as and , respectively. This allows to derive the following temporal semantic reasoning and the inference rules can be expressed as follows.

3.3. Modeling and formal expression of ocean circulation domain ontology

Ontology description languages employ specific formalized representation methods to express ontology models within a domain, which provides clear and formal concept descriptions for domain models. OWL, as one of the most widely used ontology modeling languages, has unique advantages in building the ontologies. Thus, based on ontology concepts of ocean current phenomenon, attributes, and semantic relationships, we utilize OWL to construct an ontology for ocean currents. Given that the ocean circulation is a complex system involving many spatiotemporal concepts, the following chart diagram will simplify the formal expression of ocean currents. Below, we will outline the formal construction process of ocean currents in several steps.

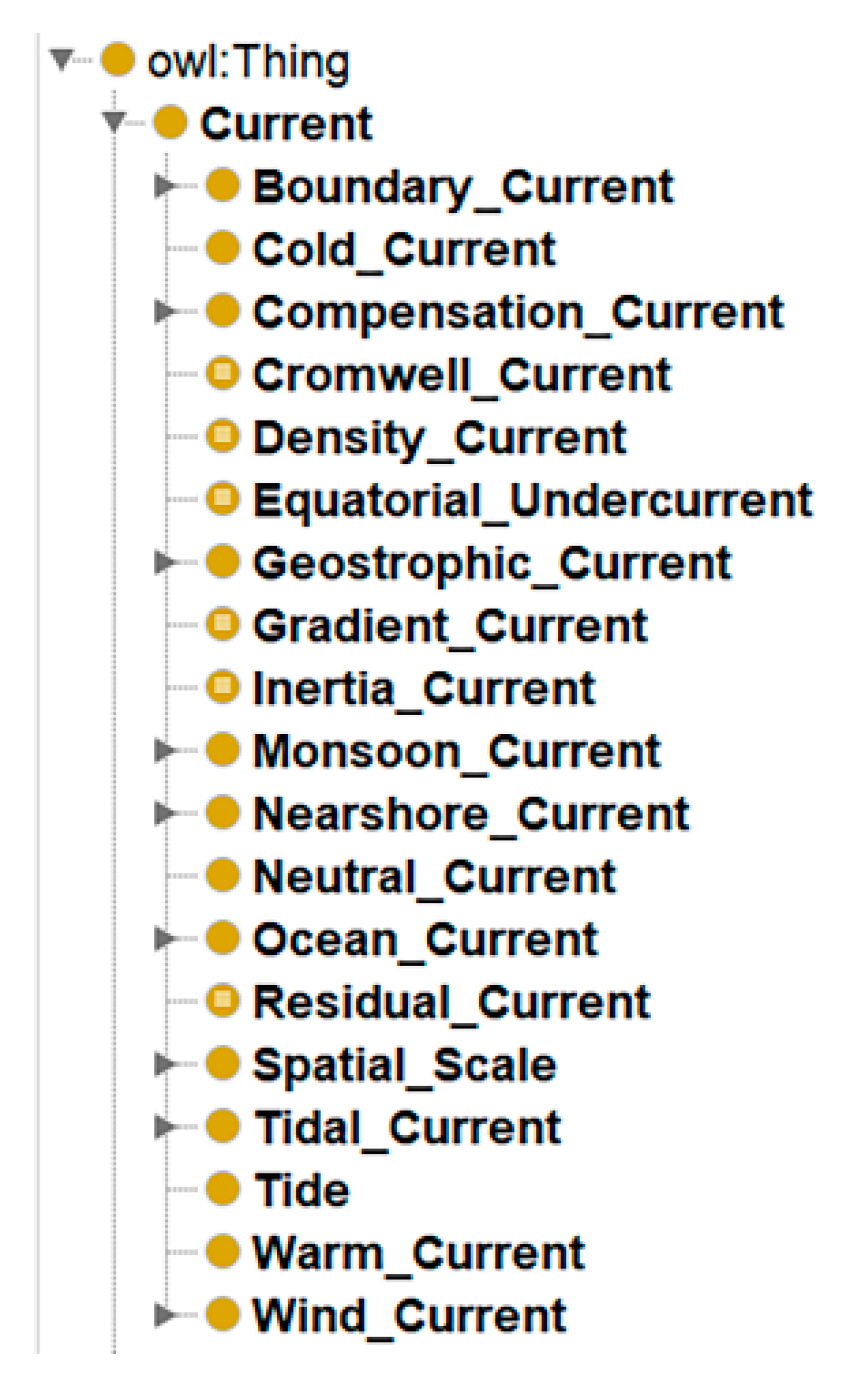

Step 1: Define the classes and the class hierarchy

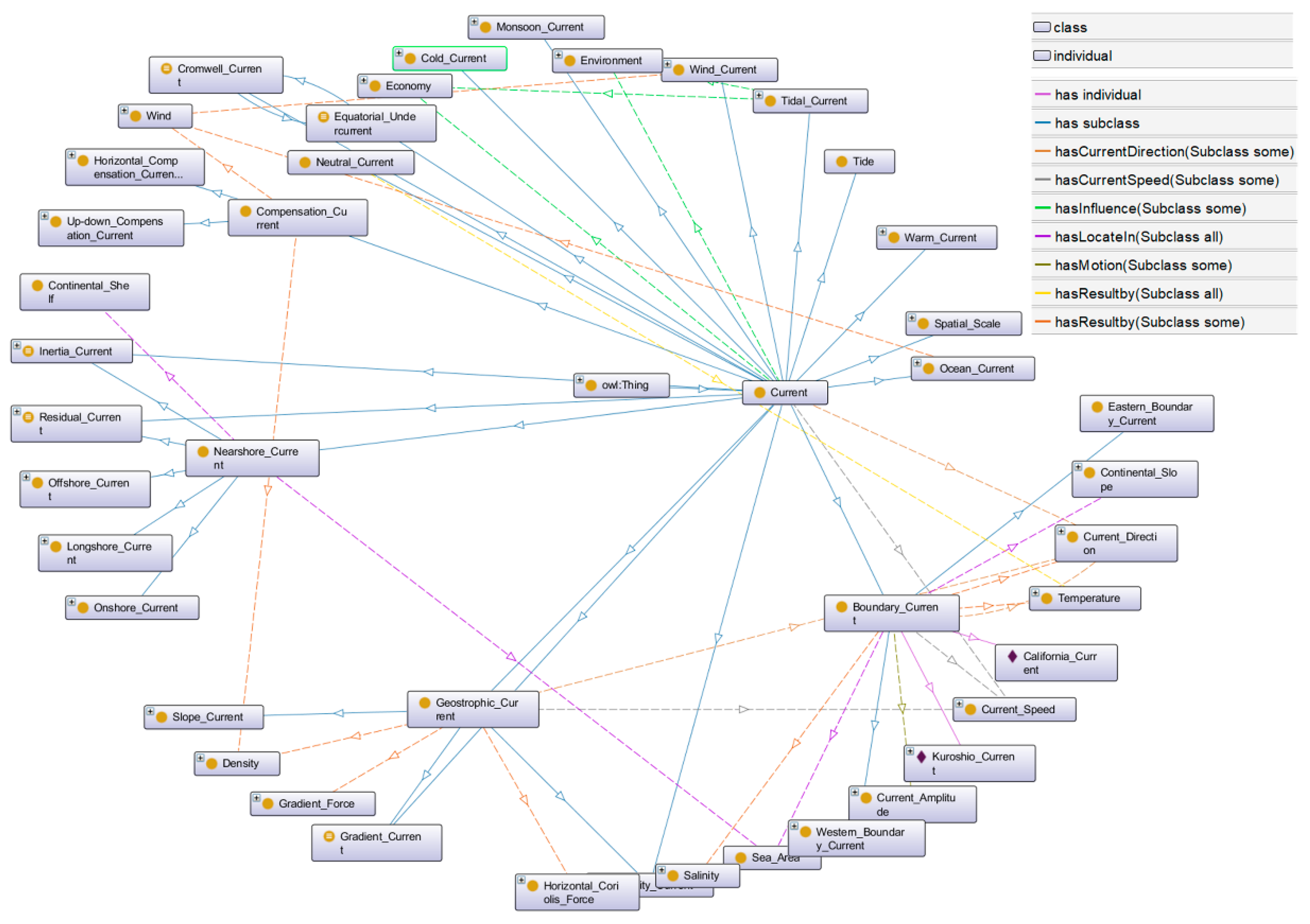

It is crucial to clearly define key terminology related to ocean circulation. Based on the analysis of concepts semantic in section 3.1, we have constructed the class hierarchy for ocean currents as depicted in following Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Class hierarchy for ocean currents

Figure 4.

Class hierarchy for ocean currents

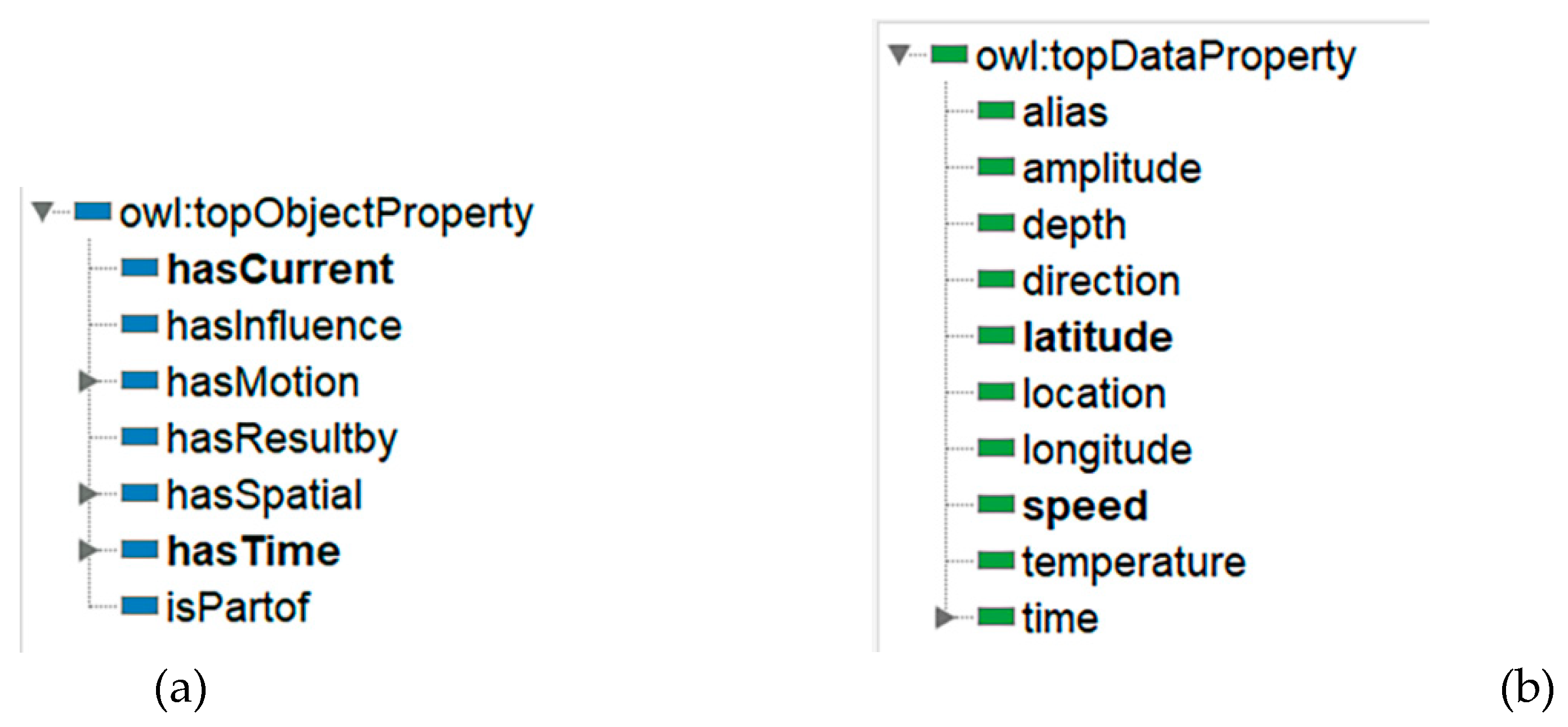

Step 2: Define the class properties

In OWL, it is necessary to define both object and data properties for ocean circulation ontology. Object properties are used to describe relationships between two entities. They represent associations, connections, or relationships between different individuals. Data properties are used to describe the characteristics, attributes, or individual values. They are usually linked to specific data types, such as strings, integers, dates, etc. An object property is commonly defined as an instance of the built-in OWL class owl: topObjectProperty, as illustrated in Figure 5(a). Similarly, a data property is typically defined as an instance of the built-in OWL class owl: topDataProperty, as shown in Figure 5(b).

Figure 5.

Define the class properties. (a) Object properties to represent extracted attributes; (b) Data properties to represent extracted attributes.

Figure 5.

Define the class properties. (a) Object properties to represent extracted attributes; (b) Data properties to represent extracted attributes.

Step 3: Define the restrictions associated with a class directly

In this context, we have established constraints for constructing an ontology of ocean circulation. For instance, we have defined restrictions to specify the domain and range of concepts. We assert that the spatial distance value cannot be negative. The data property "time" should be filtered by "data stamp", and the constraint should be defined as "some (existential)".

Step 4: Create the instances

In OWL, an "Individual" refers to a specific instance of a class in an ontology. It represents a unique object or entity that exists in the domain being modeled. Subsequently, based on the creation of classes and properties, we create instances of some ocean currents.

Figure 6 shows the concept relationships of ocean currents. The OntoGraf tab of protégé is used to develop this graph. In Figure 6, each block represents a class or an individual, and each class node represents a specific concept or a related concept. Solid lines represent subclass relationships (i.e., "has subclass") or instance relationships (i.e., "has individual"). Figure 6 clearly defines the semantic relationships within ocean circulation, and this formal and explicit description improves the representation of crucial features within ocean circulation. As a result, it improves the expression and sharing of knowledge related to ocean ontology.

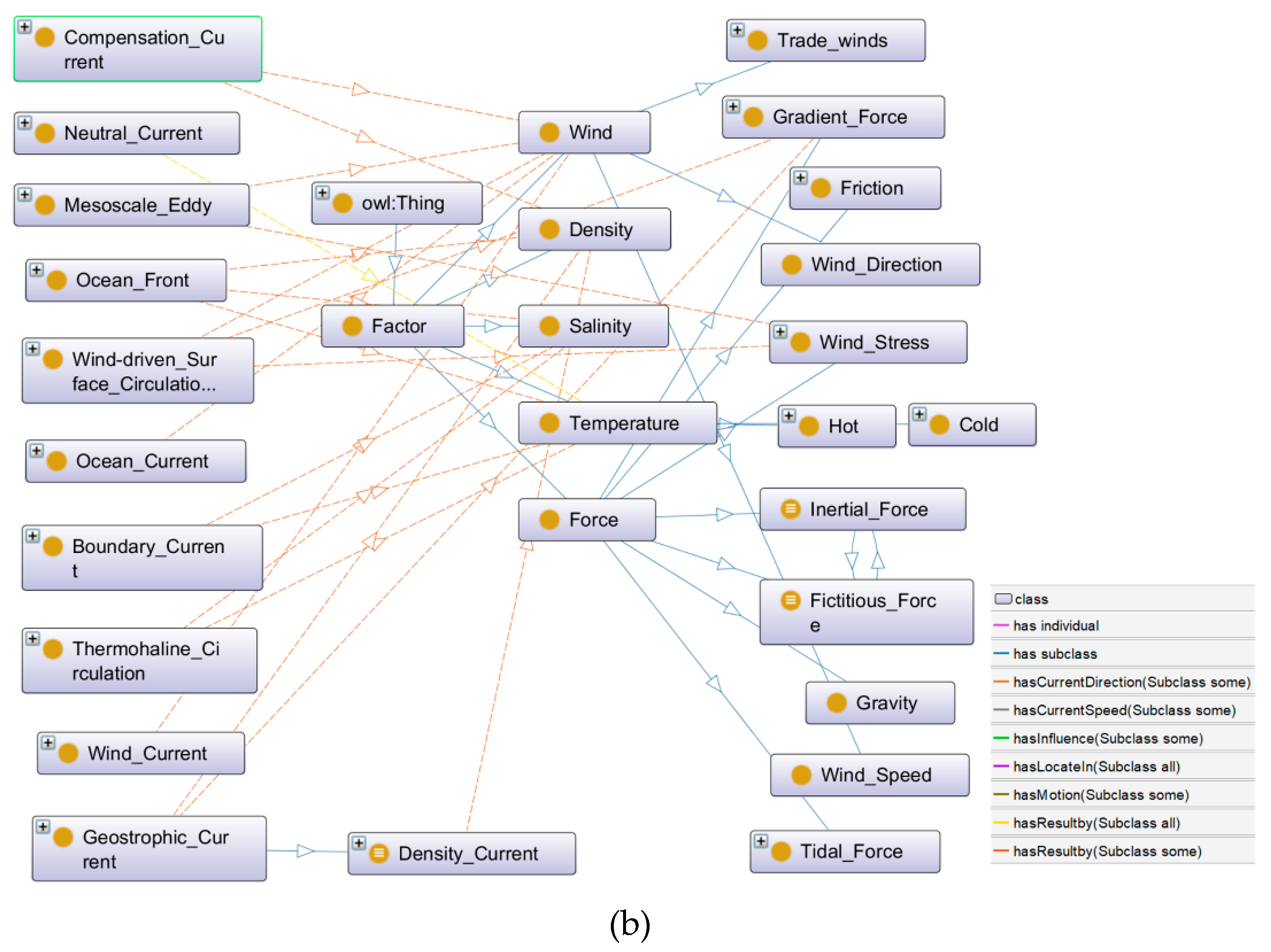

Figure 7 depicts the ontology expression of cause attributes in ocean circulation. There are numerous factors that influence the development of ocean circulation. One of the factors is wind. Through wind stress and turbulent mixing, the wind causes seawater to accumulate and redistributes its density, generating horizontal pressure gradient and turbulent friction forces. Additionally, the internal pressure gradient and friction forces within seawater also contribute to the formation of ocean currents. The differences in seawater density, which are caused by the variations of temperature and salinity, typically occur in polar regions. The Coriolis force also affects the formation of ocean currents. The topography of the area where land meets the sea can also influence the direction of ocean currents.

Figure 6.

Concept relationships of ocean currents: the graph generated by the OntoGraf tab in protégé owl.

Figure 6.

Concept relationships of ocean currents: the graph generated by the OntoGraf tab in protégé owl.

Figure 7.

The ontology expression of cause attributes in ocean circulation: the graph generated by the OntoGraf tab in protégé owl.

Figure 7.

The ontology expression of cause attributes in ocean circulation: the graph generated by the OntoGraf tab in protégé owl.

3.4. Ontology Application Experiment

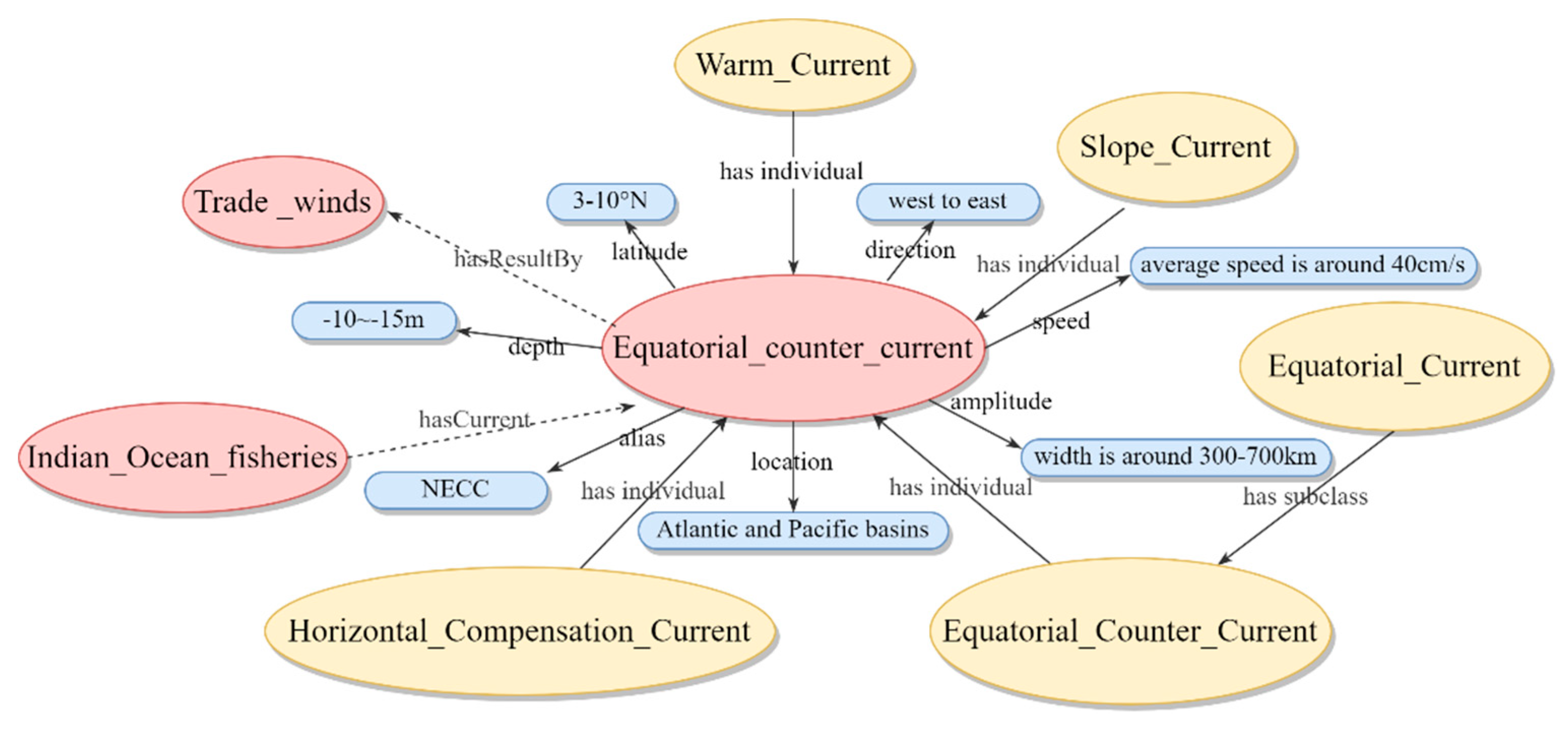

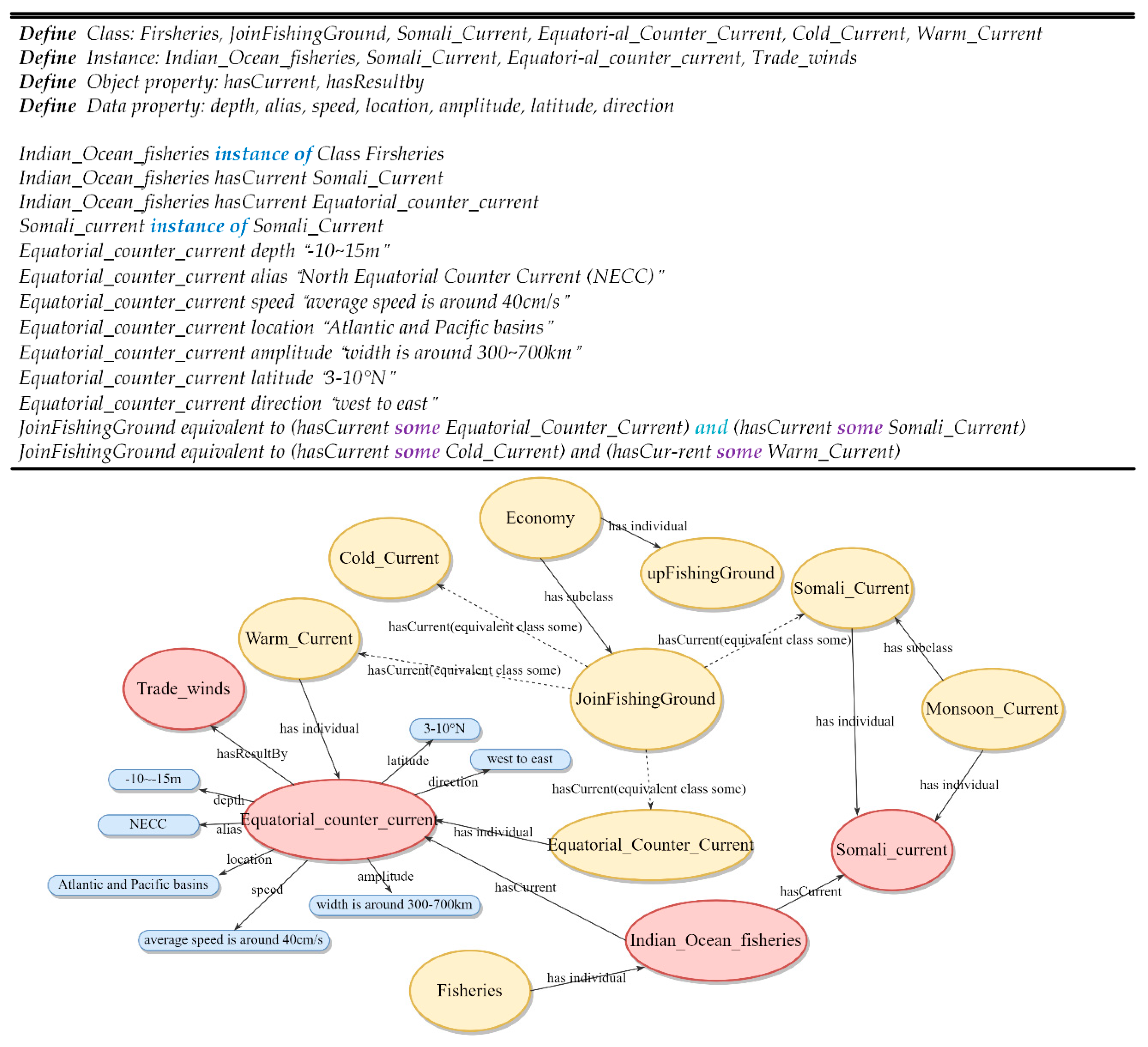

To validate above-mentioned oncology model, we take the Equatorial Counter Current as an example to illustrate the formal description of the ocean circulation.

The Equatorial Counter Current, also known as the North Equatorial Countercur-rent (NECC), flows from west to east to compensate for the ocean water carried away by the equatorial current in the eastern part of the ocean, which exhibits compensatory and inclined current characteristics. The Equatorial Counter Current is located between 3-5 degrees north latitude and 10-12 degrees north latitude, with flow rates ranging from 40-60 cm/s and reaching a maximum of 150 cm/s. In winter, flow rates decrease to 15-30 cm/s or less.

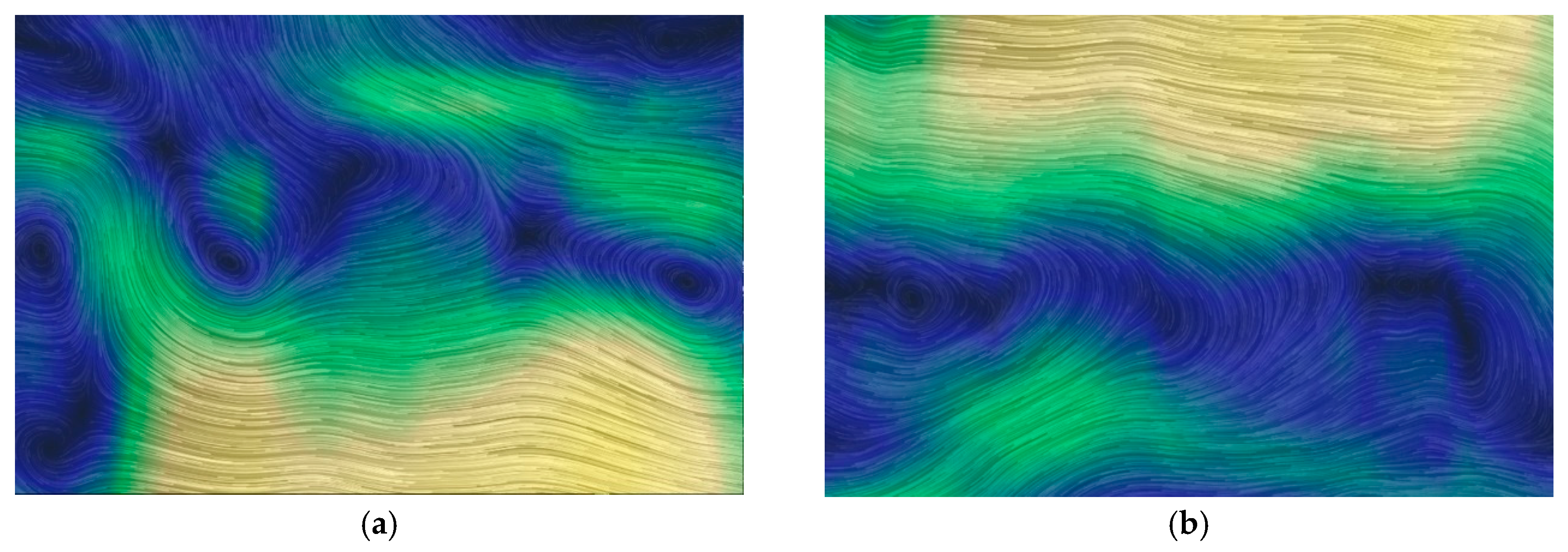

Figure 8 displays the dynamics of the Equatorial Counter Current on May 2nd. It can be clearly observed that the fuzzy boundary characteristics of the Equatorial Counter Current and its multidimensional dynamic attributes, particularly the change in flow direction, which primarily flows from west to east. Ocean circulation takes on various forms across different time and space scales, yet remains interconnected. For instance, the Equatorial Counter Current, along with the North and South Equatorial Currents, form a complex circulation system in the tropics. In certain regions, seawater converges from all directions, to force surface water to descend and create a downward current. In other regions, seawater diverges to allow deep water to rise and replenish the surface, finally create an upward current. This process brings nutrients from lower layers to the surface, which promote the growth of plankton and deepen and decrease the transparency of the seawater.

Figure 8.

The symbolization of Equatorial Counter Current. (a) The symbolization of the North Equatorial Counter Current; (b) The symbolization of the South Equatorial Counter Current.

Figure 8.

The symbolization of Equatorial Counter Current. (a) The symbolization of the North Equatorial Counter Current; (b) The symbolization of the South Equatorial Counter Current.

From the above description, combined with previous analysis of ocean current semantics, the following representation of Equatorial Counter Current can be extracted.

= {C(Current, Ocean_Current, Equatorial _Current, Equatorial_Counter_Current, Horizontal_Compensation_Current, Slope_Current, Warm_Current), R((subclass of Equatorial _Current),(disjointWith Polar_Current)), P((Atlantic and Pacific basins),(average speed is around 40cm/s),(-10~-15m),(3-10°N),(width is around 300-700km),(west to east)), I(Equatorial Counter Current)}. Using the Protégé ontology building platform, a visualization of the Equatorial Counter Current’s ontology is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

The ontology visualization of the Equatorial Counter Current.

Figure 9.

The ontology visualization of the Equatorial Counter Current.

Furthermore, based on the previously described semantic relationship expression and logical reasoning rules of ocean circulation, here we use the built-in HermiT reasoner in Protégé to verify the reasoning effects of certain instances.

Step1: Semantic relationship expression of instances

In the northwestern region of Indian Ocean, particularly in the Gulf of Aden, the high salinity and water temperature, influenced by the Somali Current and Equatorial Counter Current, create a broad upwelling. This has a significant impact on the fisheries in the Indian Ocean. From this information, it can be inferred that due to the influence of the Somali Current and Equatorial Counter Current, the Indian Ocean fisheries in this area is an instance of a mixed fishery. The partial code for describing the conceptual relationship of the Indian Ocean fishing ground instance is shown below. Figure 10 vividly illustrates the semantic relationship of this component.

Figure 10.

Describe the semantic reasoning relationship of the Indian Ocean fisheries

Figure 10.

Describe the semantic reasoning relationship of the Indian Ocean fisheries

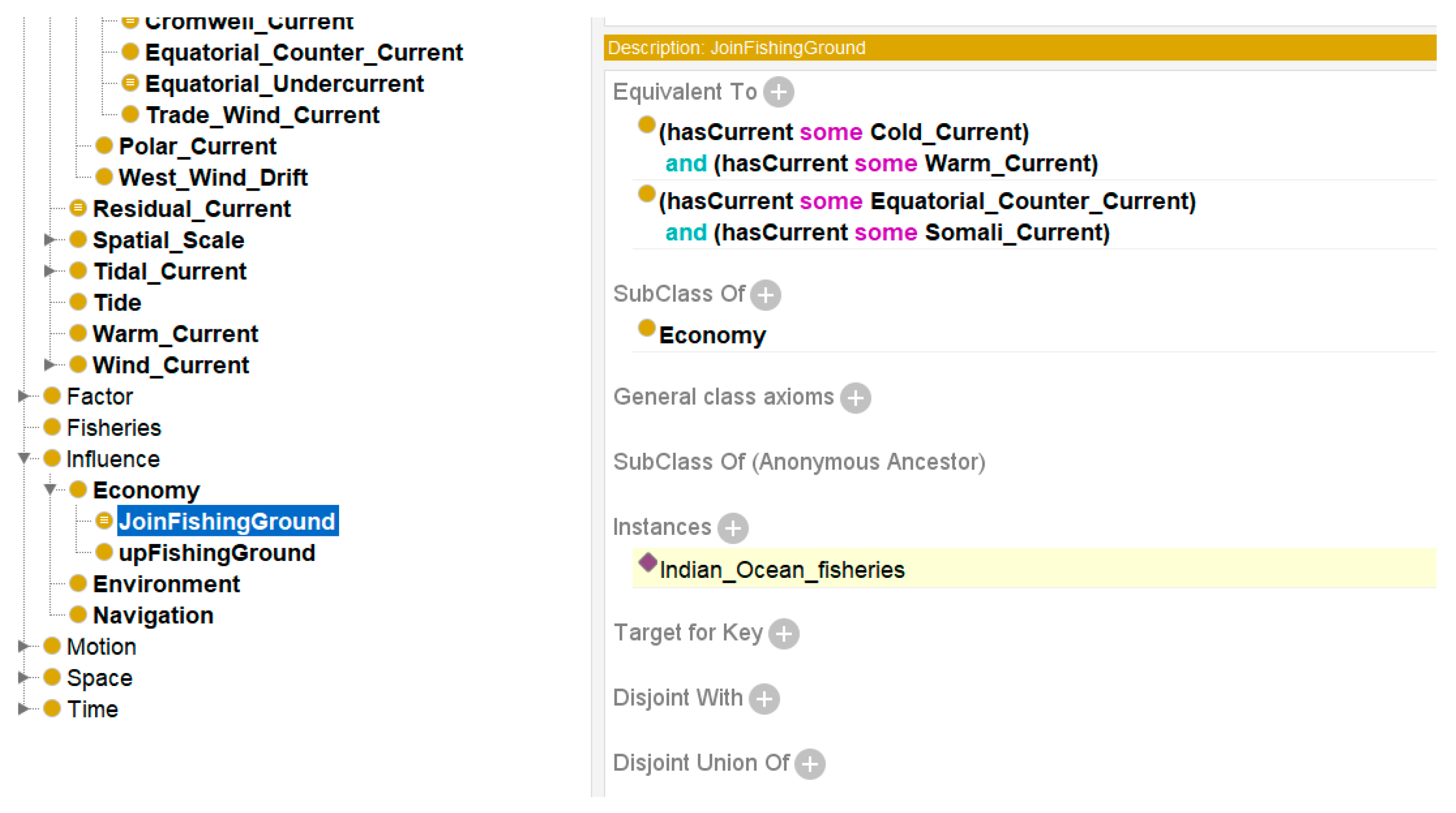

Step2: Validate the reasoning results

Based on the description of the aforementioned instance semantic relationship, by using hermiT reasoner, we obtained the following reasoning results (In Figure 11, the results inferred are represented by the yellow section).

Figure 11.

Reasoning results of instance.

Figure 11.

Reasoning results of instance.

5. Discussion

This paper introduces the relevant theories and methods of ocean circulation ontology. After carefully considering the conceptual and relational characteristics of the ocean circulation ontology and its resource environment, we have successfully constructed the ontology model by standardizing the definitions of concepts, attributes, relationships, and constraints. This approach facilitates the integration of oceanic spatiotemporal data by unifying it at the semantic level. This eliminates the challenges associated with sharing and integrating data from multiple sources that may have semantic differences.

The ontology of ocean circulation is primarily based on the characteristics of concept relationships. It extracts conceptual and relational descriptions, particularly those related to the spatial and temporal characteristics of the dynamic spatiotemporal process. Based on these characteristics, relevant attributes, and constraints, inference rules are defined to construct an ontology description framework for ocean circulation. However, ocean circulation is a dynamic process, the relationships between oceanic concepts are complex and constantly changed. Therefore, it is necessary to further clarify and define the relationships and constraints between concepts. Additionally, it is essential to introduce additional data type based on the existing ontology, expand the ontology primitives, and enhance the expressive ability of the ocean circulation ontology model.

An integrated framework for an ontology knowledge base of ocean circulation is constructed based on a standardized description of ocean circulation. This knowledge base employs a three-layer architecture to achieve an integrated process that includes ontology expression of multi-source heterogeneous data, technical services, inference, and system application management. The ocean circulation ontology knowledge base provides a unified logical description for knowledge in the domain. This technology enables the reuse of knowledge and provides efficient methods for sharing knowledge and integrating heterogeneous data within the domain. However, building an ontology knowledge base is essentially a massive project that involves a vast amount of domain-specific knowledge and requires the participation of domain experts. The ontology knowledge base is predominantly constructed manually, which can result in lower efficiency. Future work should focus on improving the fine-grained description of the ontology knowledge base and enhancing the efficiency of ontology construction. Furthermore, the validation of an ontology is crucial as it directly affects the accuracy of data description and the scalability of the ontology.