Submitted:

18 May 2023

Posted:

19 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

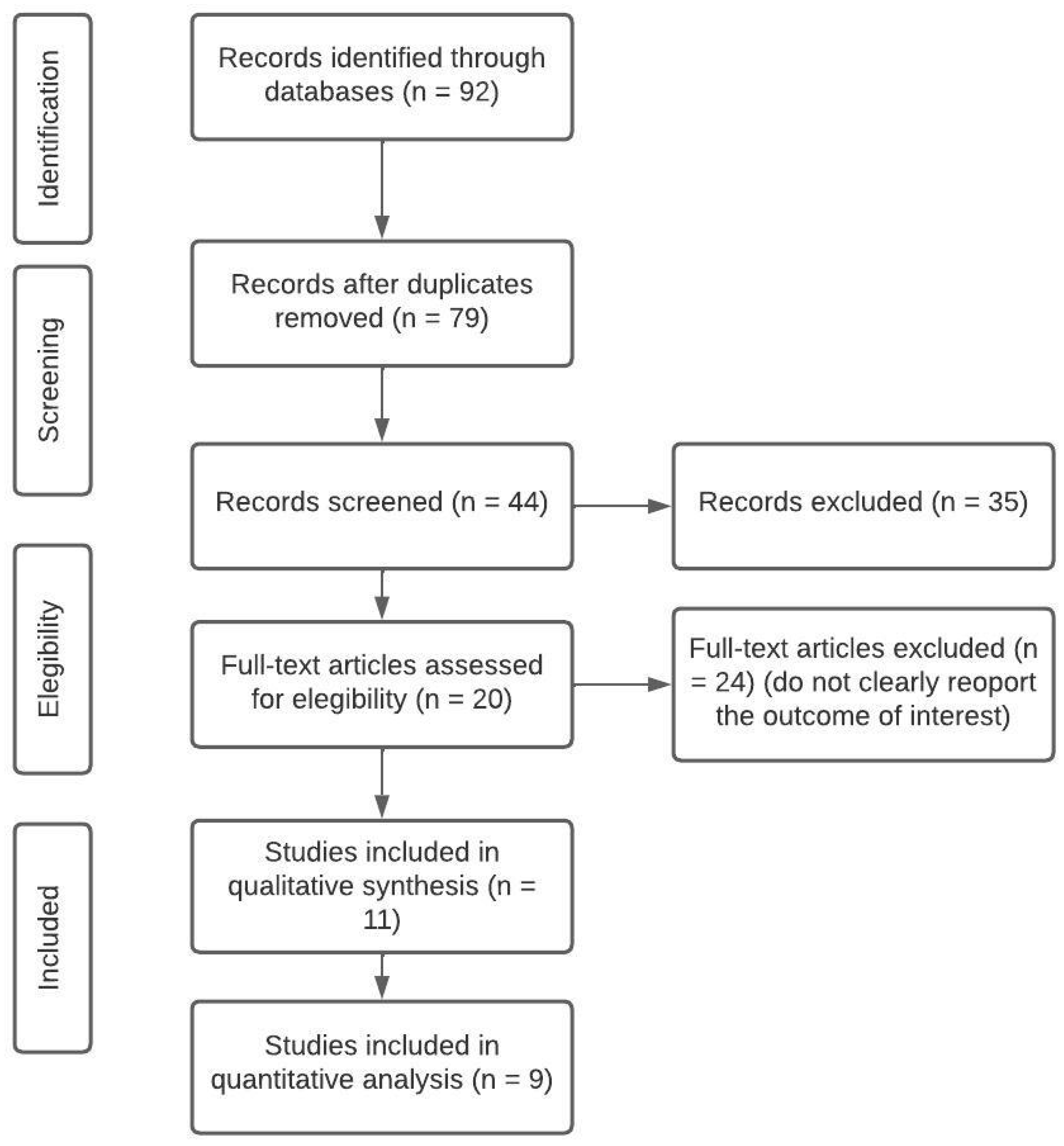

2. Methodology

2.1. Search strategy

2.2. Selection process and data analysis

3. Results

3.1. Qualtitative synthesis

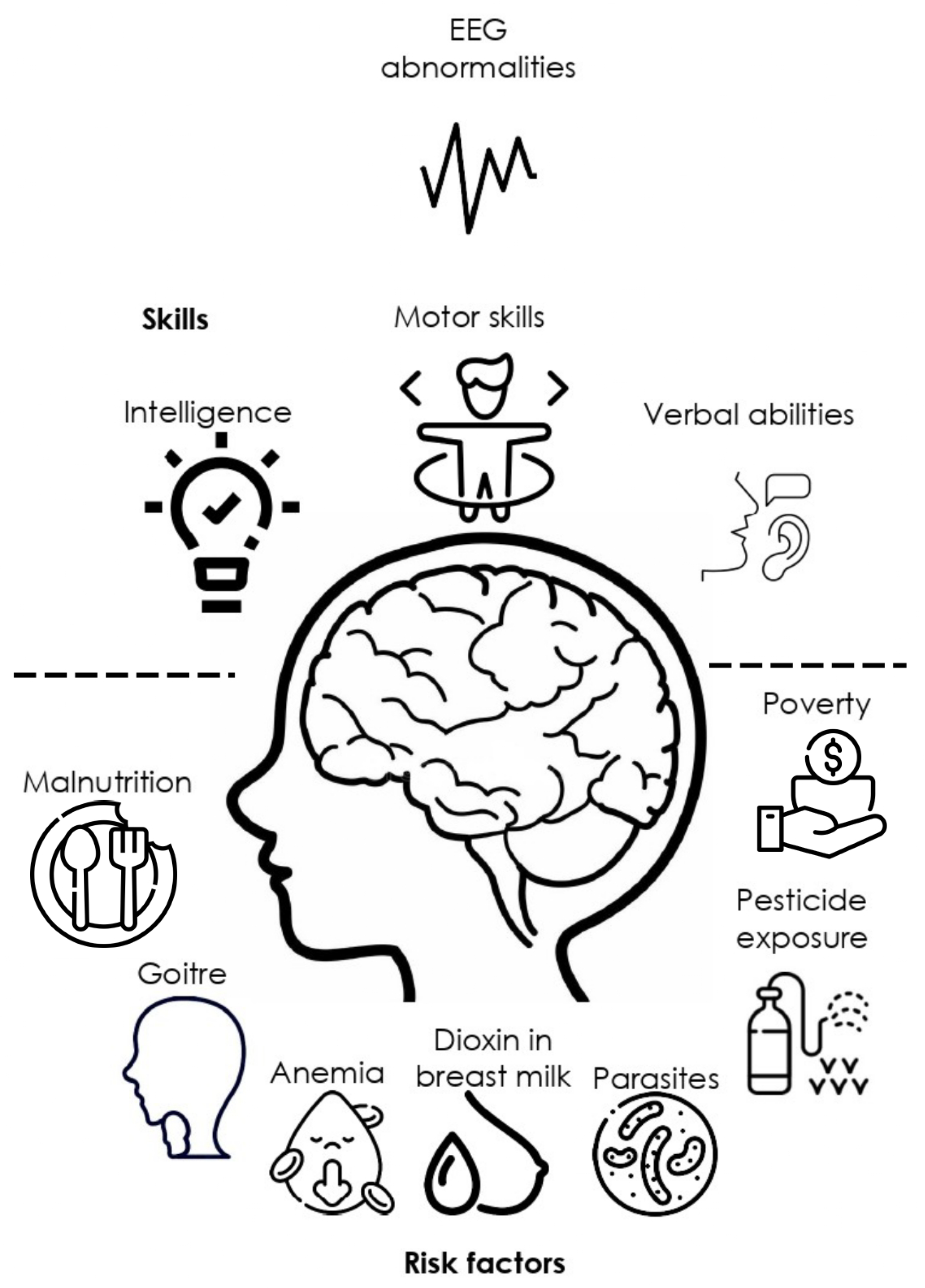

3.1.1. EEG in children at neurodevelopmental risk

| EEG finding | Brain Region | Neuropsychological finding | n | Covariates | Age | Country | Associated with factor | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sharp slow waves, Slow waves, Generalized sharp and slow waves, Sharp and slow waves | Right parietal, Bilateral centroparietal, Right frontal, Bifrontal | Soft neurological signs, poor performance in motor tasks, successive finger tapping, heel-toe tapping, alternating hand pronation supination | 208 | Movement coordination disorders | 8-10 yr | India | Malnourish | [31] |

| Lower gamma power | Frontal, and parietal | Better Executive function performance, verbal intelligence | 105 | Anemia | From birth, 24, and 48 months | Pakistan | Poverty | [40] |

| Decrease in relative Delta and increase in alpha and beta powers | Right frontal, and parietal | Positive correlation with language, and motor development | 55 | Gestational age, body length and head circumference | Prenatal-2-year follow-up | Vietnam (US) | Dioxin in breast milk | [45] |

| Lower relative alpha, and higher relative theta power | Bilateral central, temporal, and parietal | Delay gratification and non-verbal cognitive ability. Lower scores in risk exposure group for visual reception | 143 | Friendliness | 18 months | US (International adoption) | Adoption, deprivation, parental exposure to drugs, parental malnourishment and premature birth | [46] |

| Decrease in Alpha, high theta | Lingual gyrus, and inferior frontal gyrus orbital right Middle temporal gyrus | WISC Full-Scale IQ | 108 | Classification techniques | 5-11 yr | Caribean islands | Protein undernutrition | [47] |

| Centro-parietal slow-wave, paroxysmal, and focal abnormalities. Increment of slow (<5 Hz). Decrease of alpha power (8.9 Hz) | Fronto-central. Centro-parietal, frontal | Non | 108 | Non | 5-11 yr | Barbados | Protein undernutrition | [48] |

| Abnormal slow wave background EEG tracings, Paroxysmal activity | Non | 194 | Parasitism, and goitre, iodine level | 9-13 yr | Ecuador | Malnutrition | [49] | |

| Bilateral slow waves, Slow abnormal waves, Sharp abnormal waves | Anterior brain areas, subcortical origin, Posterior regions | Reduced verbal abilities, problem solving/concentration, and focusing, and inhibition-control/flexibility in at-risk groups | 194 | Infection protozoan parasite, Parent’s education | 9-13 yr | Ecuador | Malnutrition | [50] |

| Alpha 1 band, and alpha-beta power ratio under driving 8 Hz | Temporo-occipital | Non | 20 | Lethargic movement, depressed oxygen consumption, and sodium pump activity | 5-23 months | Jamaica | Malnutrition, Marasmus and Kwashiorkor | [51] |

| Synchronous theta waves | Frontal and limbic | Motor and tactile perseverations, emotional-motivational regulation, poor communication skills | 172 | Learning difficulties | 10-12 yr | Russia | Non | [42,43] |

3.1.2. EEG, environmental and social risk factors

3.2. Quantitative analysis

| Reference | EEG technique | n | Age | p-value | r | 95% CI Upper limit |

95% CI Lower limit |

Fisher’s Zr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [61] | EEG Seizures report | 1014 | 0-17 yr | <0.01 | 0.0809 | 0.0194 | 0.1417 | 0.081 |

| [62] | ERPs | 50 | 6-7 yr | .450 | - | - | - | - |

| [63] | ERPs | 178 | 4-12 yr | .651 | - | - | - | - |

| [64] | EEG Seizures report | 494 | * | <0.001 | 0.1476 | 0.0602 | 0.2328 | 0.1487 |

| [65] | EEG Seizures report | 16 | * | <0.001 | 0.7419 | 0.3895 | 0.3895 | 0.9548** |

| [66] | EEG Seizures report | 72 | 6-14 yr | * | 0.3798 | 0.1624 | 0.562 | 0.3998** |

| [67] | EEG Seizures report | 679 | * | * | 0.0833 | 0.0081 | 0.1575 | 0.0835 |

| [68] | EEG Seizures report | 112 | 6-14 yr | <0.001 | 0.126 | 0.0513 | 0.1994 | 0.1267 |

| [69] | ERPs | 148 | 1-5 month | 0.356 | 0.356 | 0.2065 | 0.4892 | 0.3723** |

| [40] | EEG Gamma power | 105 | 0-24 months | 0.036 | 0.2049 | 0.0138 | 0.3816 | 0.2079 |

| [70] | EEG alpha and gamma power | 41 | 12-16 yr | <0.01 | 0.0016 | -0.3062 | 0.3091 | 0.0016 |

3.2.1. EEG abnormalities and frequent co-morbidity in rural areas

4. Integrated analysis: current limitations and future directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| qEEG | Quantitative Electroencephalography |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| IQ | Intellectual Quotient |

References

- Buda, A.; Dean, O.; Adams, H.R.; Mwanza-Kabaghe, S.; Potchen, M.J.; Mbewe, E.G.; Kabundula, P.P.; Mweemba, M.; Matoka, B.; Mathews, M.; Menon, J.A.; Wang, B.; Birbeck, G.L.; Bearden, D.R. Neighborhood-Based Socioeconomic Determinants of Cognitive Impairment in Zambian Children With HIV: A Quantitative Geographic Information Systems Approach. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society 2021, 10, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esqueda-Elizondo, J.J.; Juárez-Ramírez, R.; López-Bonilla, O.R.; García-Guerrero, E.E.; Galindo-Aldana, G.M.; Jiménez-Beristáin, L.; Serrano-Trujillo, A.; Tlelo-Cuautle, E.; Inzunza-González, E. Attention Measurement of an Autism Spectrum Disorder User Using EEG Signals: A Case Study. Mathematical and Computational Applications 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Arias, F.J.; García-Guerrero, E.E.; Tlelo-Cuautle, E.; Colores-Vargas, J.M.; García-Canseco, E.; López-Bonilla, O.R.; Galindo-Aldana, G.M.; Inzunza-González, E. Evaluation of Machine Learning Algorithms for Classification of EEG Signals. Technologies 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfurtscheller, G.; Lopes da Silva, F.H. Event-related EEG/MEG synchronization and desynchronization: basic principles. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology 1999, 110, 1842–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selim R. Benbadis, M.; Aatif M. Husain, M.; Peter W. Kaplan, M.; William O. Tatum, IV, D. Handbook of EEG Interpretation.; Demos Medical, 2008.

- Fried, S.; Moshé, S.L. Basic physiology of the EEG. Neurology Asia 2011, 16, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Schomer, D.L.; Lopes da Silva, F.H. Niedermeyer’s Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields; Oxford University Press, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Jellinger, K.A. Niedermeyer’s Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields, 6th edn. European Journal of Neurology 2011, 18, e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miley, C.E.; Forster, F.M. Activation of partial complex seizures by hyperventilation. Archives of neurology 1977, 34, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, J.S.; Chae, K.B.; Mauk, G.W.; McDonald, A. Achieving Access to Mental Health Care for School-Aged Children in Rural Communities: A Literature Review. The rural educator 2018, 39, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.L.; Franke, M.F.; Rusangwa, C.; Mukasakindi, H.; Nyirandagijimana, B.; Bienvenu, R.; Uwimana, E.; Uwamaliya, C.; Ndikubwimana, J.S.; Dorcas, S.; et al. Outcomes of a primary care mental health implementation program in rural Rwanda: A quasi-experimental implementation-effectiveness study. PloS one 2020, 15, e0228854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crichlow, M.A.; Northover, P.; others. Race and Rurality in the Global Economy; SUNY Press, 2018.

- BOOK REVIEWS. The Professional Geographer 1986, 38, 430–457. [CrossRef]

- K. Bryant Smalley, PhD, P.; Jacob C. Warren, P. Rural Public Health : Best Practices and Preventive Models.; Springer Publishing Company, 2014.

- Allott, K.; Lloyd, S. The provision of neuropsychological services in rural/regional settings: professional and ethical issues. Applied neuropsychology 2009, 16, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, D.; Du, J.; Wang, P.; Yang, W. Urban-rural comparisons in health risk factor, health status and outcomes in Tianjin, China: A cross-sectional survey (2009-2013). Australian Journal of Rural Health 2019, 27, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Ceballos, B.; Martínez-Herrera, E.; Ocharan-Hernández, M.E.; Guerra-Araiza, C.; Farfán García, E.D.; Muñoz-Ramírez, U.E.; Fuentes-Venado, C.E.; Pinto-Almazán, R. Nutritional Status and Poverty Condition Are Associated with Depression in Preschoolers. Children 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalley, K.B.; Warren, J.C.; Rainer, J. Rural mental health: Issues, policies, and best practices; Springer Publishing Company, 201.

- Bell, E.; Merrick, J. Rural Child Health: International Aspects.; Health and Human Development, Nova Science Publishers, Inc, 2010.

- Beck, S.; Wojdyla, D.; Say, L.; Betran, A.P.; Merialdi, M.; Requejo, J.H.; Rubens, C.; Menon, R.; Van Look, P.F.A. The worldwide incidence of preterm birth: a systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2010, 88, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, N.; Mitra, K. Neurodevelopmental outcome of high risk newborns discharged from special care baby units in a rural district in India. Journal of Public Health Research 2015, 4, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doandes, F.M.; Manea, A.M.; Lungu, N.; Brandibur, T.; Cioboata, D.; Costescu, O.C.; Zaharie, M.; Boia, M. The Role of Amplitude-Integrated Electroencephalography (aEEG) in Monitoring Infants with Neonatal Seizures and Predicting Their Neurodevelopmental Outcome. Children 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, A.H.; Lai, M.M.; Finnigan, S.; Ware, R.S.; Boyd, R.N.; Colditz, P.B. Background EEG features and prediction of cognitive outcomes in very preterm infants: A systematic review. Early Human Development 2018, 127, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Duran, N.L.; Nusslock, R.; George, C.; Kovacs, M. Frontal EEG asymmetry moderates the effects of stressful life events on internalizing symptoms in children at familial risk for depression. Psychophysiology 2012, 49, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; Chou, R.; Glanville, J.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Lalu, M.M.; Li, T.; Loder, E.W.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; McDonald, S.; McGuinness, L.A.; Stewart, L.A.; Thomas, J.; Tricco, A.C.; Welch, V.A.; Whiting, P.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Journal of clinical epidemiology 2021, 134, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcino, C.O.; Teles, R.B.d.A.; Almeida, J.R.G.d.S.; Lirani, L.d.S.; Araújo, C.R.M.; Gonsalves, A.d.A.; Maia, G.L.d.A. [Evaluation of the effect of pesticide use on the health of rural workers in irrigated fruit farming]. Ciencia & saude coletiva 2019, 24, 3117–3128. [Google Scholar]

- Correction: Perceptions and practices related to birthweight in rural Bangladesh: Implications for neonatal health programs in low- and middle-income settings. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, 1.

- Chanchani, D. Maternal and child nutrition in rural Chhattisgarh: the role of health beliefs and practices. Anthropology & Medicine 2019, 26, 142–158. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer, J.E.; Borders, T.F.; Blanton, J. Rural residence is not a risk factor for frequent mental distress: a behavioral risk factor surveillance survey. BMC public health 2005, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UEDA, T.; MUSHA, T.; ASADA, T.; YAGI, T. Classification Method for Mild Cognitive Impairment Based on Power Variability of EEG Using Only a Few Electrodes. Electronics & Communications in Japan 2016, 99, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, K.N.; Das, D.; Agarwal, D.K.; Upadhyay, S.K.; Mishra, S. Soft neurological signs and EEG pattern in rural malnourished children. Acta paediatrica Scandinavica 1989, 78, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, G.; Solovieva, Y.; Machinskaya, R.; Quintanar, L. Atención selectiva visual en el procesamiento de letras: un estudio comparative. OCNOS: Revista de Estudios sobre Lectura 2016, 15, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckwith, L.; Parmelee, A H, J. EEG patterns of preterm infants, home environment, and later IQ. Child development 1986, 57, 777–789. [CrossRef]

- Placencia, M.; Sander, J.W.; Roman, M.; Madera, A.; Crespo, F.; Cascante, S.; Shorvon, S.D. The characteristics of epilepsy in a largely untreated population in rural Ecuador. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 1994, 57, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozac, V.V.; Chaturvedi, M.; Hatz, F.; Meyer, A.; Fuhr, P.; Gschwandtner, U. Increase of EEG Spectral Theta Power Indicates Higher Risk of the Development of Severe Cognitive Decline in Parkinson’s Disease after 3 Years. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2016, 8, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.R.; Varcin, K.J.; O’Leary, H.M.; Tager-Flusberg, H.; Nelson, C.A. EEG power at 3 months in infants at high familial risk for autism. Journal of neurodevelopmental disorders 2017, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanemura, H.; Sano, F.; Ohyama, T.; Mizorogi, S.; Sugita, K.; Aihara, M. EEG characteristics predict subsequent epilepsy in children with their first unprovoked seizure. Epilepsy research 2015, 115, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehlers, C.L.; Wall, T.L.; Garcia-Andrade, C.; Phillips, E. Effects of age and parental history of alcoholism on EEG findings in mission Indian children and adolescents. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research 2001, 25, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amores-Villalba, A.; Mateos-Mateos, R. Revisión de la neuropsicología del maltrato infantil: la neurobiología y el perfil neuropsicológico de las víctimas de abusos en la infancia. Psicologia Educativa 2017, 23, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarullo, A.R.; Obradović, J.; Keehn, B.; Rasheed, M.A.; Siyal, S.; Nelson, C.A.; Yousafzai, A.K. Gamma power in rural Pakistani children: Links to executive function and verbal ability. Developmental cognitive neuroscience 2017, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machinskaya, R.I.; Semenova, O.A.; Absatova, K.A.; Sugrobova, G.A. Neurophysiological factors associated with cognitive deficits in children with ADHD symptoms: EEG and neuropsychological analysis. Psychology & Neuroscience 2014, 7, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, O.; Machinskaya, R. The influence of the functional state of brain regulatory systems on the efficiency of voluntary regulation of cognitive activity in children: II. neuropsychological and EEG analysis of brain regulatory functions in 10-12-year-old children with learning difficulties. Human Physiology 2015, 41, 478–486. [Google Scholar]

- Kurgansky, A.; Machinskaya, R. Bilateral frontal theta-waves in EEG of 7-8-year-old children with learning difficulties: Qualitative and quantitative analysis. Human Physiology 2012, 38, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machinskaya, R.; Kurgansky, A. Frontal bilateral synchronous theta waves and the resting EEG coherence in children aged 7-8 and 9-10 with learning difficulties. Human Physiology 2013, 39, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghiem, G.T.; Nishijo, M.; Pham, T.N.; Ito, M.; Pham, T.T.; Tran, A.H.; Nishimaru, H.; Nishino, Y.; Nishijo, H. Adverse effects of maternal dioxin exposure on fetal brain development before birth assessed by neonatal electroencephalography (EEG) leading to poor neurodevelopment; a 2-year follow-up study. Science of the Total Environment 2019, 667, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarullo, A.R.; Gunnar, M.R.; Garvin, M.C. Atypical EEG Power Correlates With Indiscriminately Friendly Behavior in Internationally Adopted Children. Developmental Psychology 2011, 47, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringas Vega, M.L.; Guo, Y.; Tang, Q.; Razzaq, F.A.; Calzada Reyes, A.; Ren, P.; Paz Linares, D.; Galan Garcia, L.; Rabinowitz, A.G.; Galler, J.R.; Bosch-Bayard, J.; Valdes Sosa, P.A. An Age-Adjusted EEG Source Classifier Accurately Detects School-Aged Barbadian Children That Had Protein Energy Malnutrition in the First Year of Life. Frontiers in neuroscience 2019, 13, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bringas-Vega, M.L.; Taboada-Crispi, A.; Bosch-Bayard, J.; Galán-García, L.; Bryce, C.; Rabinowitz, A.G.; Prichep, L.S.; Isenhart, R.; CALZADA-REYES, A.A.; Virues, T.; Galler, J.R.; Sosa, P.V. F168. An EEG fingerprint of early protein-energy malnutrition. Clinical Neurophysiology 2018, 129, e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levav, M.; Cruz, M.E.; Mirsky, A.F. EEG abnormalities, malnutrition, parasitism and goitre: a study of schoolchildren in Ecuador. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992) 1995, 84, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levav, M.; Mirsky, A.F.; Schantz, P.M.; Castro, S.; Cruz, M.E. Parasitic infection in malnourished school children: effects on behaviour and EEG. Parasitology 1995, 110 Pt 1, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, S.; Young, R.E.; Golden, M.H. Electrophysiological assessment of brain function in severe malnutrition. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992) 1995, 84, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottrell, J.N.; Thomas, D.S.; Mitchell, B.L.; Childress, J.E.; Dawley, D.M.; Harbrecht, L.E.; Jude, D.A.; Valentovic, M.A. Rural and urban differences in prenatal exposure to essential and toxic elements. Journal of toxicology and environmental health. Part A 2018, 81, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thatcher, R.W.; Lester, M.L. Nutrition, environmental toxins and computerized EEG: a mini-max approach to learning disabilities. Journal of learning disabilities 1985, 18, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urizar, Guido G, J.; Caliboso, M.; Gearhart, C.; Yim, I.S.; Dunkel Schetter, C. Process Evaluation of a Stress Management Program for Low-Income Pregnant Women: The SMART Moms/Mamás LÍSTAS Project. Health education & behavior : the official publication of the Society for Public Health Education 2019, 46, 930–941.

- Atif, N.; Nazir, H.; Zafar, S.; Chaudhri, R.; Atiq, M.; Mullany, L.C.; Rowther, A.A.; Malik, A.; Surkan, P.J.; Rahman, A. Development of a Psychological Intervention to Address Anxiety During Pregnancy in a Low-Income Country. Frontiers in psychiatry 2020, 10, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St John, A.M.; Kao, K.; Liederman, J.; Grieve, P.G.; Tarullo, A.R. Maternal cortisol slope at 6 months predicts infant cortisol slope and EEG power at 12 months. Developmental psychobiology 2017, 59, 787–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, C.; Berry, D.J. Moderate within-person variability in cortisol is related to executive function in early childhood. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 81, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, E.R.; Ahn, H.; Prichep, L.; Trepetin, M.; Brown, D.; Kaye, H. Developmental equations for the electroencephalogram. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1980, 210, 1255–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBourgeois, M.K.; Dean, D.C.; Deoni, S.C.L.; Kohler, M.; Kurth, S. A simple sleep EEG marker in childhood predicts brain myelin 3.5 years later. NeuroImage 2019, 199, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffari-Rafi, A.; Mehdizadeh, R.; Ghaffari-Rafi, S.; Leon-Rojas, J. Demographic and socioeconomic disparities of benign and malignant spinal meningiomas in the United States. Neuro-Chirurgie 2021, 67, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, P.; Tomson, T.; Edebol Eeg-Olofsson, K.; Brännström, L.; Ringbäck Weitoft, G. Association between sociodemographic status and antiepileptic drug prescriptions in children with epilepsy. Epilepsia 2012, 53, 2149–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kihara, M.; de Haan, M.; Garrashi, H.H.; Neville, B.G.R.; Newton, C.R.J.C. Atypical brain response to novelty in rural African children with a history of severe falciparum malaria. Journal of the neurological sciences 2010, 296, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihara, M.; Hogan, A.M.; Newton, C.R.; Garrashi, H.H.; Neville, B.R.; de Haan, M. Auditory and visual novelty processing in normally-developing Kenyan children. Clinical Neurophysiology 2010, 121, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariuki, S.M.; Matuja, W.; Akpalu, A.; Kakooza-Mwesige, A.; Chabi, M.; Wagner, R.G.; Connor, M.; Chengo, E.; Ngugi, A.K.; Odhiambo, R.; Bottomley, C.; White, S.; Sander, J.W.; Neville, B.G.R.; Newton, C.R.J.C.; Twine, R.; Gómez Olivé, F.X.; Collinson, M.; Kahn, K.; Tollman, S.; Masanja, H.; Mathew, A.; Pariyo, G.; Peterson, S.; Ndyomughenyi, D.; Bauni, E.; Kamuyu, G.; Odera, V.M.; Mageto, J.O.; Ae-Ngibise, K.; Akpalu, B.; Agbokey, F.; Adjei, P.; Owusu-Agyei, S.; Kleinschmidt, I.; Doku, V.C.K.; Odermatt, P.; Nutman, T.; Wilkins, P.; Noh, J. Clinical features, proximate causes, and consequences of active convulsive epilepsy in Africa. Epilepsia 2014, 55, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidi, I.R.; Chidi, N.A.; Ebele, A.A.; Chinyelu, O.N. Co-Morbidity of attention deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and epilepsy In children seen In University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital Enugu: Prevalence, Clinical and social correlates. The Nigerian postgraduate medical journal 2014, 21, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, K.; Rogathe, J.; Whittaker, R.G.; Mankad, K.; Hunter, E.; Burton, M.J.; Todd, J.; Neville, B.G.R.; Walker, R.; Newton, C.R.J.C. Co-morbidity of epilepsy in Tanzanian children: a community-based case-control study. Seizure 2012, 21, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariuki, S.M.; White, S.; Chengo, E.; Wagner, R.G.; Ae-Ngibise, K.A.; Kakooza-Mwesige, A.; Masanja, H.; Ngugi, A.K.; Sander, J.W.; Neville, B.G.; Newton, C.R. Electroencephalographic features of convulsive epilepsy in Africa: A multicentre study of prevalence, pattern and associated factors. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology 2016, 127, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, K.J.; Rogathe, J.; Whittaker, R.; Mankad, K.; Hunter, E.; Burton, M.J.; Todd, J.; Neville, B.G.R.; Walker, R.; Newton, C.R.J.C. Epilepsy in Tanzanian children: association with perinatal events and other risk factors. Epilepsia 2012, 53, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katus, L.; Mason, L.; Milosavljevic, B.; McCann, S.; Rozhko, M.; Moore, S.E.; Elwell, C.E.; Lloyd-Fox, S.; de Haan, M. ERP markers are associated with neurodevelopmental outcomes in 1-5 month old infants in rural Africa and the UK. NeuroImage 2020, 210, 116591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenger, M.J.; Murray Kolb, L.E.; Scott, S.P.; Boy, E.; Haas, J.D. Modeling relationships between iron status, behavior, and brain electrophysiology: evidence from a randomized study involving a biofortified grain in Indian adolescents. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos-Vidal, L.; Martínez-García, M.; Pretus, C.; Garcia-Garcia, D.; Martínez, K.; Janssen, J.; Vilarroya, O.; Castellanos, F.X.; Desco, M.; Sepulcre, J.; Carmona, S. Local functional connectivity suggests functional immaturity in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Human Brain Mapping 2018, 39, 2442–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Zang, Y.; Sun, L.; Sui, M.; Long, X.; Zou, Q.; Wang, Y. Abnormal neural activity in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroreport 2006, 17, 1033–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, B.J.; Castellanos, F.X.; Giedd, J.N.; Marsh, W.L.; Hamburger, S.D.; Schubert, A.B.; Vauss, Y.C.; Vaituzis, A.C.; Dickstein, D.P.; Sarfatti, S.E.; Rapoport, J.L. Implication of right frontostriatal circuitry in response inhibition and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 1997, 36, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).