Submitted:

18 May 2023

Posted:

19 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation of bacteria from the rhizosphere and roots

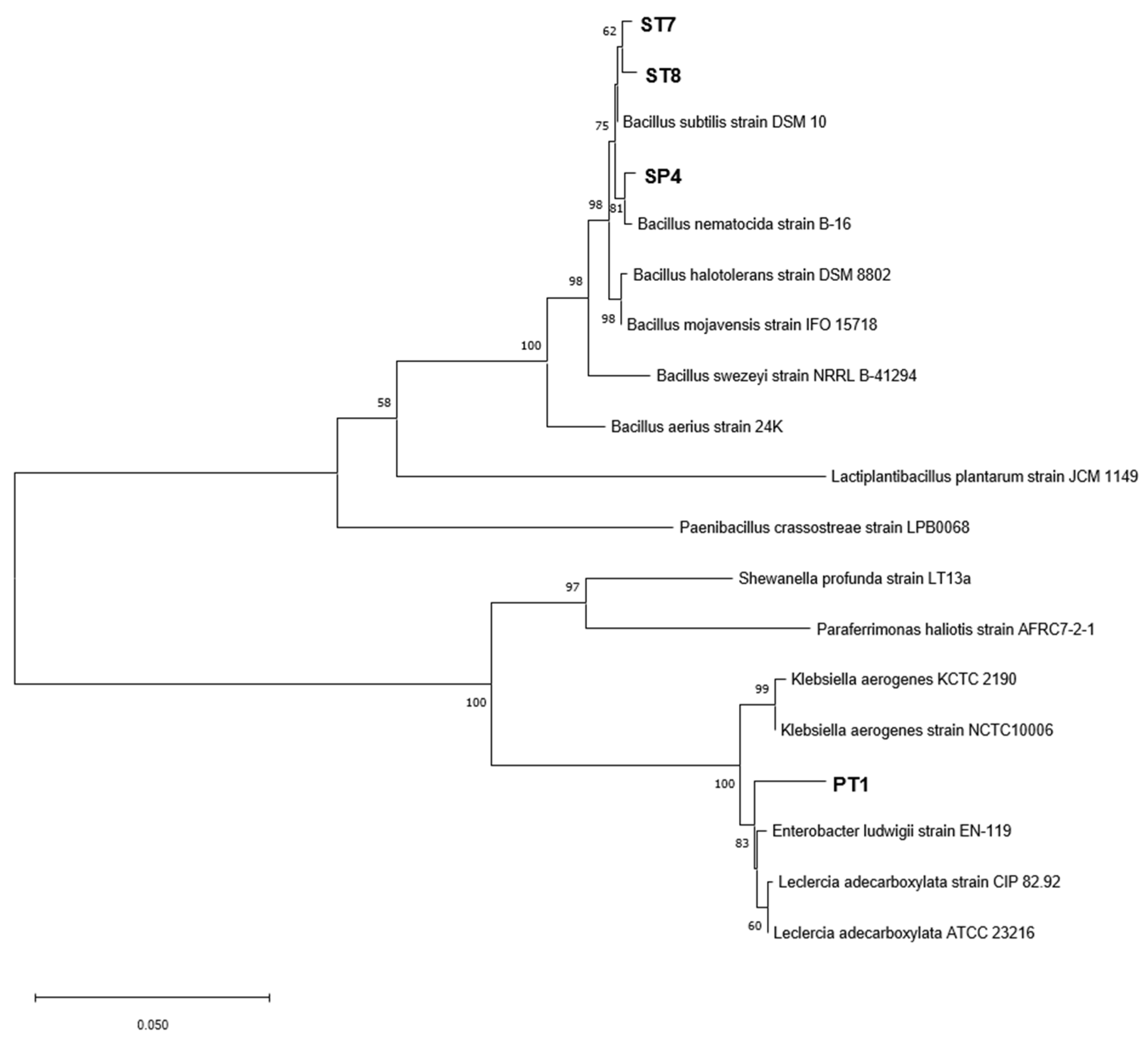

2.2. Identification of rhizosphere and root bacteria

2.3. In vitro antagonistic activity of the selected strains

2.4. In planta tests

2.5. Temperature tolerance assay

2.6. In Vitro Test of PGP Traits

2.6.1. Protease production assay

2.6.2. Cellulase production assay

2.6.3. Chitinase production assay

2.6.4. Hydrogen cyanide (HCN) production

2.6.5. Phosphate solubilization

2.6.6. Siderophore production

2.6.7. Indole-3-acetic acid production

2.7. Exoenzyme activity

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of bacteria from the rhizosphere soil and roots

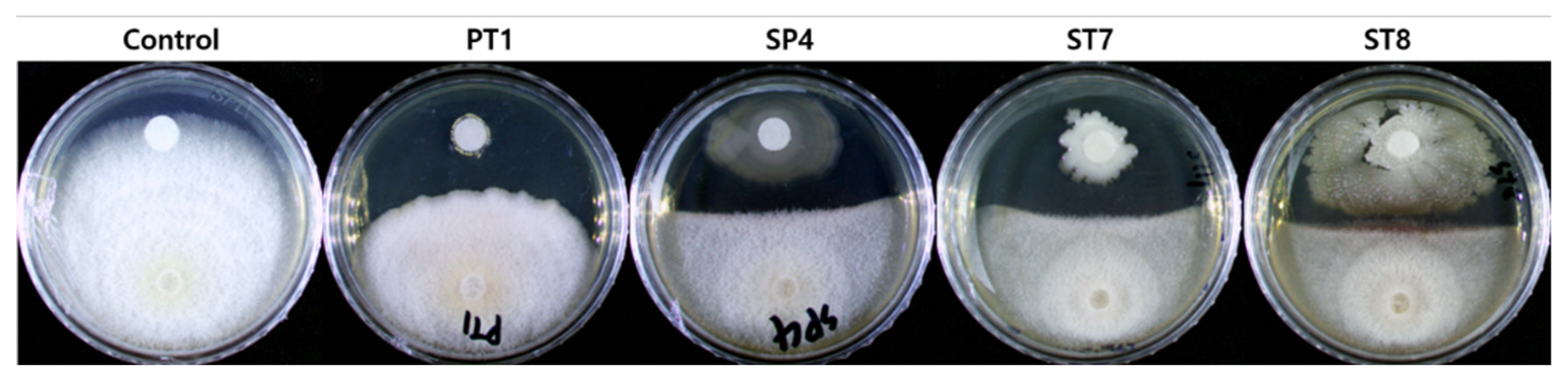

3.2. In vitro antagonistic activity of the selected strains

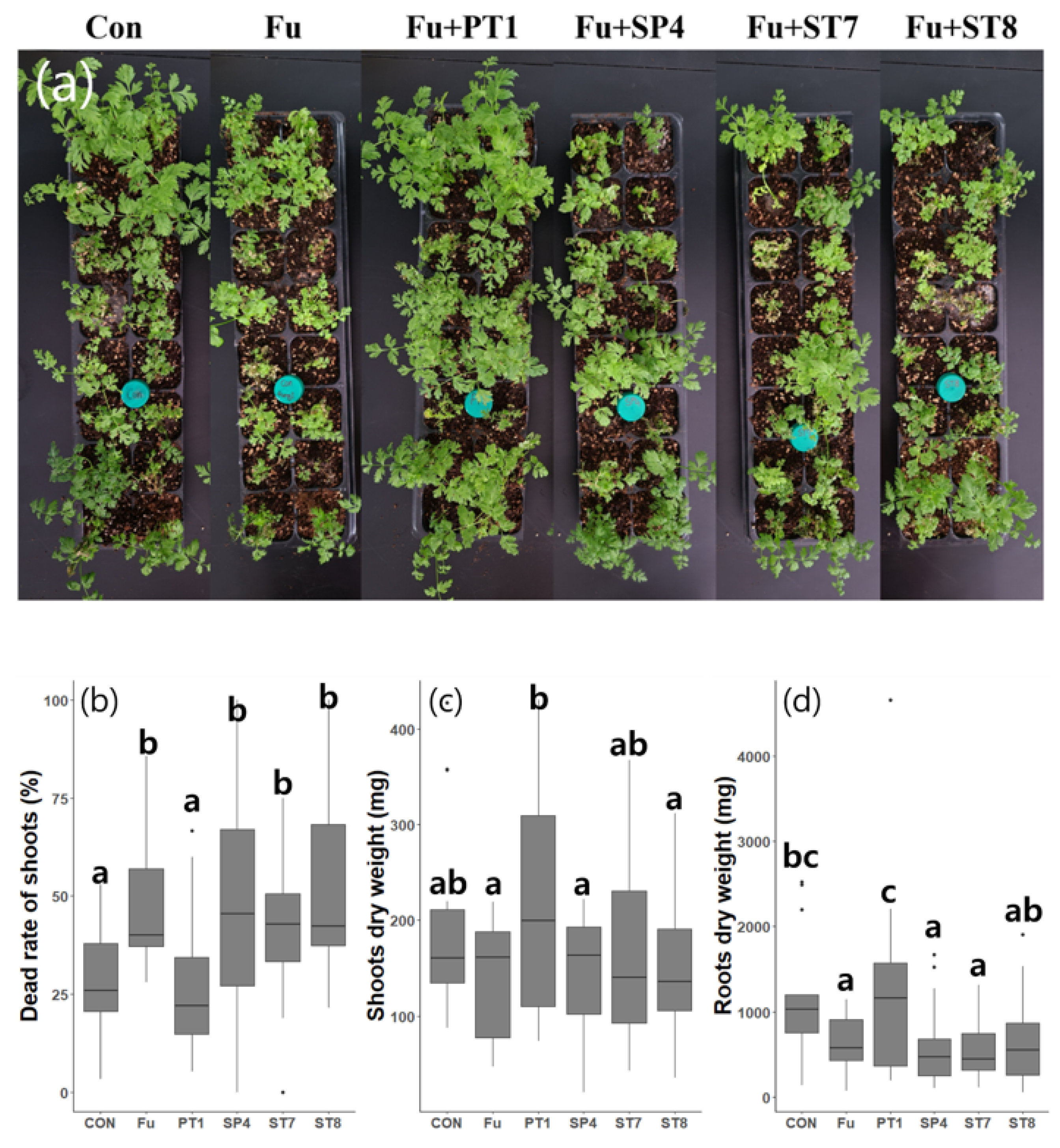

3.3. In planta tests

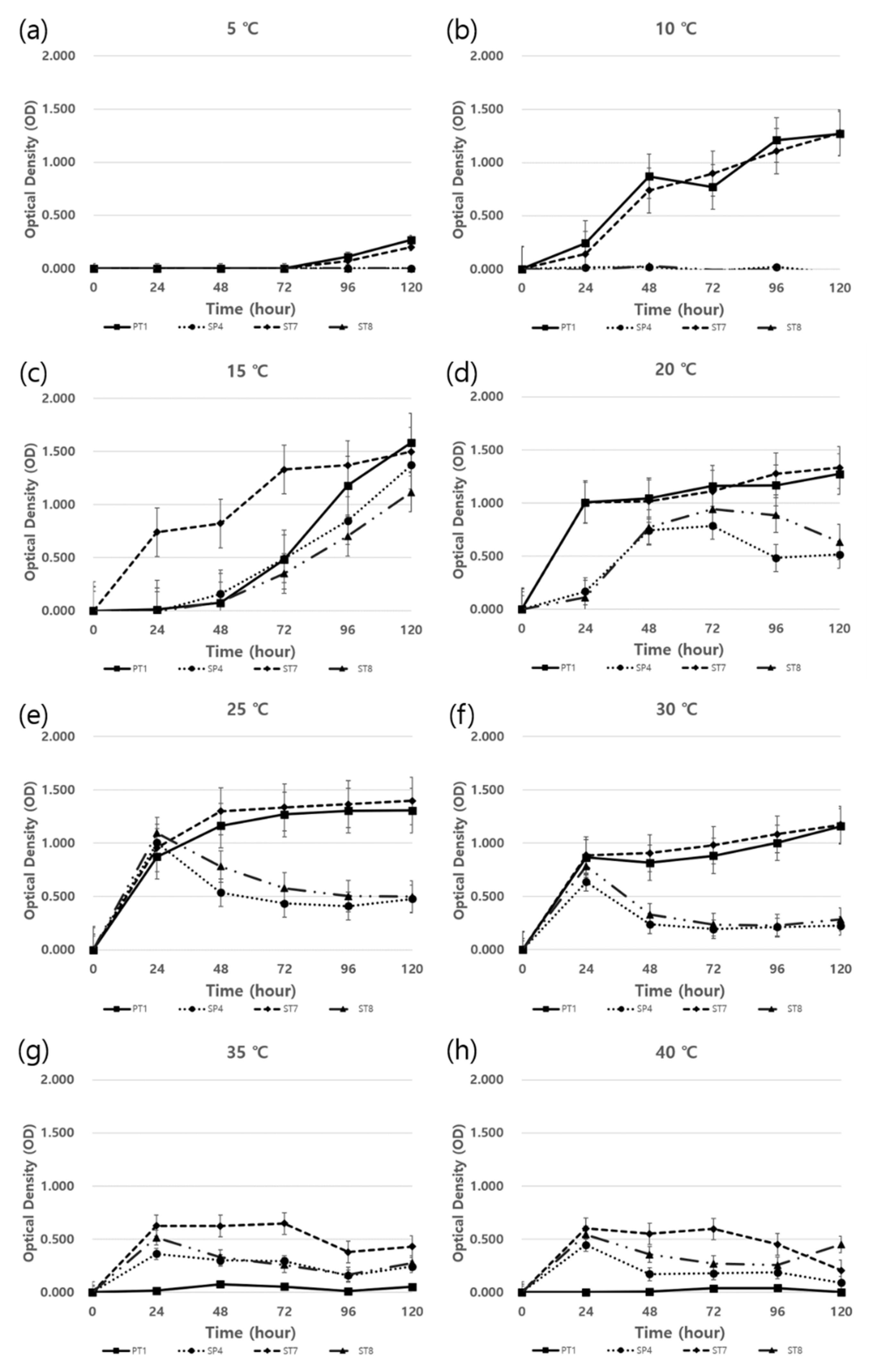

3.4. Growth traits in response to temperature

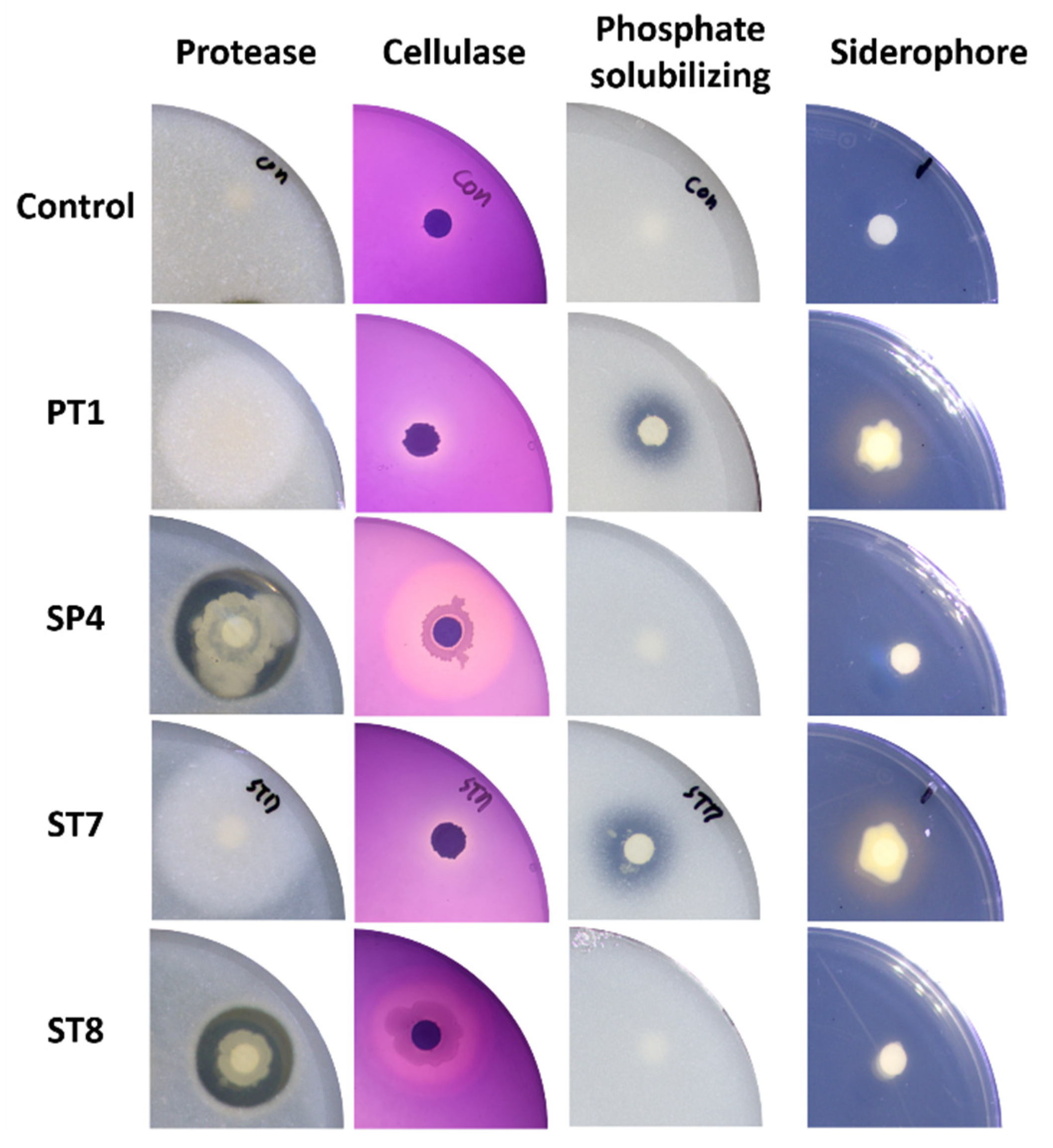

3.5. In Vitro Test of PGP Traits

3.6. Exoenzyme activity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OH, Y.J.; Seo, H.R.; Choi, Y.M.; Jung, D.S. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of the extracts from the aerial parts of Cnidium officinale Makino. Korean Journal of Medicinal Crop Science, 2010, 18, 373-378.

- Leem, H.H.; Kim, E.O.; Seo, M.J.; Choi, S.W. Anti-inflammatory effects of volatile flavor extract from herbal medicinal prescriptions including Cnidium officinale Makino and Angelica gigas Nakai. Journal of the society of cosmetic scientists of Korea, 2011, 37, 199-210. [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.J.; Kim, H.C.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, W.Y.; Han, S.H.; Kang J.W. Review of long-term climate change research facilities for forests. Korean Journal of Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 2016, 18, 274-286. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.K.; Kim, S.N.; Yoo, S.O.; An, J.G.; Kim, C.S.; Lee, M.S.; Kim, S.Y. Agricultural Technology Guide 007, Medicinal crops.; Hwang, J.W.; Cho, E.H.; Lim, E.S.; Jang, J.G.; Park, C.G.; Rural Development Administration: Jeonju, Korea, 2019; pp. 245-252, ISBN 978-89-480-3525-4 95520.

- Kim, Y.I.; Yu, H.H.; Yu, D.Y.; Jung, J.T.; Eom, Y.R. Changes in major components of Angelica Gigantis Radix and Glycyrrhizae Radix by storage temperature and period. Korean Medicinal Crop Society Conference Papers, 2015, 23, 336-337.

- Kim, K.Y.; Han, K.M.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, C.W.; Jeon, K.S.; Jung, C.R. Effect of Soil Properties on Soil Fungal Community in First and Continuous Cultivation Fields of Cnidium officinale Makino. Korean Journal of Medicinal Crop Science, 2020, 28, 209-220. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, S.M.; Park, H.J.; Lee, S.H.; Jang, J.S.; Lee, M.H. Isolation and characterization of various strains of Bacillus sp. having antagonistic effect against phytopathogenic fungi. Microbiology and Biotechnology Letters, 2019, 47, 603-613. [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)[Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information; [1988] – [cited 2017 Apr 06]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 1 December 2022.).

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Molecular biology and evolution, 2021, 38, 3022-3027. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, S.W.; Lamsal, K.; Lee, Y.S. Evaluation of rhizobacterial isolates for their antagonistic effects against various phytopathogenic fungi. The Korean Journal of Mycology, 2016, 44, 36-47. [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, E.; Kebede, A.; Nigussie, A.; Kebede, G.; Tafesse, M. Isolation and characterization of urease-producing soil bacteria. International Journal of Microbiology. 2021, 2021, 8888641. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.S.; Noor, Z.M.; Ariffin, Z.Z. Isolation and identification fibrinolytic protease endophytic fungi from Hibiscus leaves in Shah Alam. International Journal of Biological, Veterinary, Agricultural and Food Engineering. 2014, 8,1027-1030.

- Gohel, H.; Contractor, C.N.; Ghosh, S.K.; Braganza, V.J. A comparative study of various staining techniques for determination of extra cellular cellulase activity on Carboxy Methyl Cellulose (CMC) agar plates. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2014, 3, 261-266.

- Ramirez, M.G.; Avelizapa, L.I.R.; Avelizapa, N.G.R.; Camarillo, R.C. Colloidal chitin stained with Remazol Brilliant Blue R®, a useful substrate to select chitinolytic microorganisms and to evaluate chitinases. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2004, 56, 213-219. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Ding, H.; Yu, Y.; Chen, B. A cold-adapted chitinase-producing bacterium from Antarctica and its potential in biocontrol of plant pathogenic fungi. Marine drugs. 2019, 17, 695. [CrossRef]

- Deshwal, V.K.; Kumar, P. Production of plant growth promoting substance by Pseudomonads. J Acad Ind Res. 2013, 2, 221-215.

- Nautiyal, C.S. An efficient microbiological growth medium for screening phosphate solubilizing microorganisms. FEMS microbiology Letters. 1999, 170, 265-270. [CrossRef]

- Louden, B.C.; Haarmann, D.; Lynne, A.M. Use of blue agar CAS assay for siderophore detection. Journal of microbiology & biology education. 2011, 12, 51-53. [CrossRef]

- Glickmann, E.; Dessaux, Y. A critical examination of the specificity of the Salkowski reagent for indolic compounds produced by phytopathogenic bacteria. Applied and environmental microbiology. 1995, 61, 793-796. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, T.R.; Okamoto, D.; Jacobson D.J. Colonization of muskmelon and nonsusceptible crops by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. melonis and other species of Fusarium. Phytopathology. 1989, 79, 1095-1100.

- Wang, B.; Brubaker, C.L.; Burdon, J.J. Fusarium species and Fusarium wilt pathogens associated with native Gossypium populations in Australia. Mycological Research. 2004, 108, 35-44. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Horticultural and Herbal Science, Korean Society for Horticultural Science. History of Korean Horticulture; Korean Society for Horticultural Science: Suwon, Korea, 2013; pp. 399-402, ISBN 978-89-97776-67-2 93520.

- Vaughan, A.; Guilbault, G.G.; Hackney, D. Fluorometric methods for analysis of acid and alkaline phosphatase. Analytical chemistry, 1971, 43, 721-724. [CrossRef]

- Janckila, A.J.; Takahashi, K.; Sun, S.Z.; Yam, L.T. Naphthol-ASBI phosphate as a preferred substrate for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase isoform 5b. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 2001, 16, 788-793. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.; Holmström, S.J. Siderophores in environmental research: Roles and applications. Microbial biotechnology. 2014, 7, 196-208. [CrossRef]

- Saha, M.; Sarkar, S.; Sarkar, B.; Sharma, B.K.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Tribedi, P. Microbial siderophores and their potential applications: A review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2016, 23, 3984-3999. [CrossRef]

- Cochard, B.; Giroud, B.; Crovadore, J.; Chablais, R.; Arminjon, L.; Lefort, F. Endophytic PGPR from Tomato Roots: Isolation, In Vitro Characterization and In Vivo Evaluation of Treated Tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Microorganisms 2022, 10, 765. [CrossRef]

- Nabila, N.; Kasiamdari, R.S. Antagonistic activity of siderophore-producing bacteria from black rice rhizosphere against rice blast fungus Pyricularia oryzae. Microbiology and Biotechnology Letters. 2021, 49, 217-224. [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.M.; Woo, J.W.; Kim, S.D. Purification and Characterization of the Siderophore from Bacillus licheniformis K11, a Multi-functional Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacterium. Microbiology and Biotechnology Letters. 2007, 35, 128-34.

- Jeong, T.K.; Kim, J.H.; Song, H.K. Antifungal activity and plant growth promotion by rhizobacteria inhibiting growth of plant pathogenic fungi. Korean Journal of Microbiology. 2012, 48, 16-21. [CrossRef]

- Ohtakara, A. Chitinase and β-N-acetylhexosaminidase from Pycnoporus cinnabarinus. InMethods in Enzymology. 1988, 161, 462-470. [CrossRef]

- Mamarabadi, M.; Jensen, D.F.; Lübeck, M. An N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase gene, cr-nag1, from the biocontrol agent Clonostachys rosea is up-regulated in antagonistic interactions with Fusarium culmorum. Mycological Research. 2009, 3, 33-43. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Sakazaki, R.; Kosako, Y.; Yoshizaki, E. Leclercia adecarboxylata Gen. Nov., Comb. Nov., formerly known asEscherichia adecarboxylata. Current Microbiology. 1986, 13, 79-84. [CrossRef]

- Richard, C. New Enterobacteriaceae found in medical bacteriology Moellerella wisconsensis, Koserella trabulsii, Leclercia adecarboxylata, Escherichia fergusonii, Enterobacter asbutiae, Rahnella aquatilis. InAnnales de biologie Clinique. 1989, 47, 231-236.

- Leclerc, H. Etude biochimique d'Enterobacteriaceae pigmentees. Ann Inst Pasteur 1962, 102, 726-741.

- Ahmed, B.; Shahid, M.; Syed, A.; Rajput, V.D.; Elgorban, A.M.; Minkina, T.; Bahkali, A.H.; Lee, J. Drought Tolerant Enterobacter sp./Leclercia adecarboxylata Secretes Indole-3-acetic Acid and Other Biomolecules and Enhances the Biological Attributes of Vigna radiata (L.) R. Wilczek in Water Deficit Conditions. Biology 2021, 10, 1149. [CrossRef]

- Danish, S.; Zafer-ul-Hye, M. Co-application of ACC-deaminase producing PGPR and timber-waste biochar improves pigments formation, growth and yield of wheat under drought stress. Scientific reports. 2019 Apr 12;9(1):1-3. [CrossRef]

- Bendaha, M.E.A.; Belaouni, H.A. Effect of the endophytic plant growth promoting EB4B on tomato growth. Hellenic Plant Protection Journal. 2020, 13, 54-65. [CrossRef]

- Steinkellner, S.; Mammerler, R.; Vierheilig, H. Microconidia germination of the tomato pathogen Fusarium oxysporum in the presence of root exudates. Journal of plant interactions. 2005, 1, 23-30. [CrossRef]

- Farda, B.; Djebaili, R.; Bernardi, M.; Pace, L.; Del Gallo, M.; Pellegrini, M. Bacterial Microbiota and Soil Fertility of Crocus sativus L. Rhizosphere in the Presence and Absence of Fusarium spp. Land. 2022, 11, 2048. [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, J.; Thürmer, A.; Hübel, T.; Popper, L.; Daniel, R.; Schweder, T. Characterization and optimization of Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6051 as an expression host. Journal of biotechnology. 2013, 163, 97-104. [CrossRef]

- Goto, K.; Omura, T.; Sadaie, Y. Application of the partial 16S rDNA sequence as an index for rapid identification of species in the genus Bacillus. The Journal of General and Applied Microbiology. 2000, 46, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Yarza P.; Spröer C.; Swiderski J.; Mrotzek N.; Spring S.; Tindall B.J.; Gronow S.; Pukall R.; Klenk H.P.; Lang E.; et al. Sequencing orphan species initiative (SOS): Filling the gaps in the 16S rRNA gene sequence database for all species with validly published names. Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 2013, 36, 69-73. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, N.; Shimomura, T. Action of rice α-glucosidase on maltose and starch. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 1973, 37, 67-74. [CrossRef]

- Morant, A.V.; Jørgensen, K.; Jørgensen, C.; Paquette, S.M.; Sánchez-Pérez, R.; Møller, B.L.; Bak, S. β-Glucosidases as detonators of plant chemical defense. Phytochemistry. 2008, 69, 1795-1813. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Spadaro, D.; Valente, S.; Garibaldi, A.l Gullino, M.L. Cloning, characterization, expression and antifungal activity of an alkaline serine protease of Aureobasidium pullulans PL5 involved in the biological control of postharvest pathogens. International journal of food microbiology. 2012, 153, 453-464. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.; Gómez-Cabellos, S.; Giménez, M.J.; Barro, F.; Diaz, I.; Diaz-Mendoza, M. Plant proteases: From key enzymes in germination to allies for fighting human gluten-related disorders. Frontiers in plant science. 2019, 10, 721. [CrossRef]

- Hashem, A.; Tabassum, B.; Abd_Allah, E.F. Bacillus subtilis: A plant-growth promoting rhizobacterium that also impacts biotic stress. Saudi journal of biological sciences. 2019, 26, 1291-1297. [CrossRef]

- Sivasakthi, S.; Usharani, G.; Saranraj, P. Biocontrol potentiality of plant growth promoting bacteria (PGPR)-Pseudomonas fluorescens and Bacillus subtilis: A review. African journal of agricultural research. 2014, 9, 1265-1277.

- Almaghrabi, O.A.; Abdelmoneim, T.S.; Albishri, H.M.; Moussa, T.A. Enhancement of maize growth using some plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) under laboratory conditions. Life Sci J. 2014, 11, 764-772.

- Baldrian, P. Forest microbiome: Diversity, complexity and dynamics. FEMS Microbiology reviews. 2017, 41, 109-130. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, R.; You, M.P.; Barbetti, M.J.; Chen, Y. Pathogen Biocontrol Using Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria (PGPR): Role of Bacterial Diversity. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1988. [CrossRef]

- Doty, S.L.; Freeman, J.L.; Cohu, C.M.; Burken, J.G.; Firrincieli, A.; Simon, A.; Khan, Z.; Isebrands, J.G.; Lukas, J.; Blaylock, M.J. Enhanced degradation of TCE on a superfund site using endophyte-assisted poplar tree phytoremediation. Environmental science & technology. 2017, 51, 10050-10058. [CrossRef]

| Strains | 16S rRNA identification1 | GenBank Accession No.1 |

Similarity (%) | Isolated from |

| ST7 | Bacillus inaquosorum | NR_104873.1 | 99 | Rhizosphere soil |

| ST8 | Bacillus subtilis | CP019663.1 | 99 | Rhizosphere soil |

| SP4 | Bacillus vallismortis | NR_024696.1 | 99 | Rhizosphere soil |

| PT1 | Leclercia adecarboxylata | NR_104933.1 | 99 | Root tissue |

| Strain | Protease | Cellulase | Chitinase | HCN | PS | SP | IAA (ppm) |

| PT1 | - | - | - | - | + | + | 13.19 ± 4.22 |

| SP4 | + | + | - | - | - | - | NA |

| ST7 | - | - | - | - | + | + | NA |

| ST8 | + | + | - | - | - | - | NA |

| Enzyme | PT1 | SP4 | ST7 | ST8 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | + | + | + | + |

| Esterase (C4) | + | + | + | + |

| Esterase lipase (C8) | + | + | + | + |

| Lipase (C14) | - | - | - | - |

| Leucine arylamidase | - | - | - | - |

| Valine arylamidase | - | - | - | - |

| Crystine arylamidase | - | - | - | - |

| Trypsin | - | - | - | - |

| a-chymotrypsin | - | - | - | - |

| Acid phospatase | + | - | + | + |

| Naphthol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase | + | + | + | + |

| α-galactosidase | - | - | - | - |

| β-glucuronidase | - | - | - | - |

| β-glucosidase | - | - | - | - |

| α-glucosidase | - | + | - | + |

| β-glucosidase | - | - | + | + |

| N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase | + | - | - | - |

| α-mannosidase | - | - | - | - |

| α-fucosidase | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).