1. Introduction

With increasing importance of sustainable development, bio-based packaging materials and efficient drug delivery systems are gaining attention as viable options [

1,

2]. Cellulose has attracted particular interest for its advantages, such as reproducibility, biodegradability, non-cytotoxicity, thermostability, and chemical stability [

3]. However, the water-insolubility of cellulose greatly restricts its wide application. To address this limitation, cellulose is often modified to make it water-soluble. Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) is one of most water-soluble cellulose derivatives. In addition to being water soluble, CMC inherits all the advantages of cellulose and is widely used in food packaging and drug delivery [

4].

While pure CMC films show promise as food packaging materials and efficient drug delivery systems, they often lack of sufficient mechanical properties [

5]. Large number of studies has demonstrated that the incorporation of polymers or polymer-based nanomaterials, such as chitosan and cellulose derivatives, can improve the mechanical properties of CMC films, as well as their thermodynamic stability [

6,

7,

8]. It is due to the electrostatic interaction and hydrogen bonding between polymer additives and CMC. Rheological tests are commonly used to analyze the interaction between polymeric materials [

2,

9].

The rheological properties of polymeric solution depend on various factors such as molecular weight (

), distribution of molecular weight, degree of substitution (DS), and concentration (C

CMC). For example, at fixed concentration and DS, CMC solutions exhibit shear-thinning behavior, Newtonian fluid behavior and shear-thickening behaviors with

increasing from 9×10

4 to 25×10

4, and 70×10

4 [

10]. While the concentration is increased from 0.5, 2.0 and then 3.0 g/L, CMC solutions exhibit Newtonian fluid behavior, shear-thinning, and shear-thickening behaviors, respectively [

11]. The apparent viscosity of CMC solutions increases with increasing

, DS, and C

CMC. CMC with large

shows more notable influence on rheological properties. The variation of these rheological properties depends on the interaction between carboxymethyl cellulose molecules [

12].

In this paper, the effect of chitosan and cellulose derivatives on rheological properties of CMC-based film-forming solutions were comparatively studied. The molecular structure and content of the derivatives, and temperature were investigated. Based on the results of rheology, selected CMC-based films were prepared and their properties including wettability, transparency, hydrophilicity, mechanical properties, degradation and toxicity were studied. This work will provide an idea from the design of film-forming solution to the targeted preparation of food packaging and effective drug delivery materials with specific properties.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (UPS grade, CMC) and O-carboxymethylated chitosan (O-CMCh, with a degree of degradation ≥ 80% and a viscosity of 80 mPa.s) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Hydroxypropyltrimethyl ammonium chloride chitosan (HACC) with a degree of substitution (DS) of ≥ 98% was provided by Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. N-2-hydroxypropyl-3-trimethylammonium-O-carboxymethyl chitosan (HTCMCh), cellulose nanofibers (CNF), and cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) were synthesized according to our previous works [

13,

14,

15].

2.2. Preparation of film-forming solutions

Take the preparation of CMC/HTCMCh solution as an example. Mother solutions of CMC (4% w/v) and HTCMCh (2% w/v) were prepared at 80°C and 60°C by magnetic stirring (600 rpm) for 4 hours, then cooled to room temperature naturally. A film-forming solution consisting of 12.5 g CMC mother solution, certain amounts of HTCMCh and deionized water, the total weight of the film-forming solution was 25 g. The solution was then kept at 60°C and magnetically stirred (600 rpm) for 4 hours, followed by cooling to 25°C for later use. The mass ratios of HTCMCh to CMC (mHTCMCh/mCMC) were 1:99, 5:95, and 10:90, and abbreviated as CMC/HTCMCh1%, CMC/HTCMCh5%, CMC/HTCMCh10%, respectively.

The film-forming solutions of CMC/O-CMCh, CMC/HACC, CMC/CNC and CMC/CNF were also prepared, and the abbreviations were similar to those of CMC/HTCMCh.

2.3. Preparation of CMC-based films

Each film-forming solution (25 g) was poured into a polytetrafluoroethylene mold with 5.5 cm in diameter and 0.7 cm in height. The molds were then placed in a drying oven at 40 °C for 48 hours to evaporate the water.

2.4. Characterization of CMC-based films

The thickness of the films was measured using an electronic digital Vernier caliper (Shenzhen Duliang Precision Machinery Co., Ltd.) with an accuracy of 0.001 mm. During the measurement, five points were randomly selected for each film, and the values were averaged.

The wettability of the films was evaluated by measuring the contact angles using a KRUSS DSA 100 analyzer through the sessile drop method.

The whiteness and transmittance of the films were tested using a YQ-Z-48B whiteness tester (Hangzhou Qingtong Brocade Automation Technology Co., Ltd., China). A R457 whiteboard with a whiteness of 84.5 was used as the calibration sample. The transparency and transmittance were measured using a white board with a Ry of 84% and a black background.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of the films was performed using a thermo-gravimetric analyzer (Mettler Toledo, Switzerland) in the range of 25ºC to 500ºC. The heating rate was 10ºC·min-1, and a nitrogen flow was 100mL·min-1.

The tensile strength (TS), elongation at break (EB) and Young’s moduli (E) were measured using an electronic universal testing machine (Jinan Teson Machinery Co. Ltd.). The films were cut into 4.0×1.0 cm strips, and the crosshead speed was set at 0.2 cm/min.

2.5. Rheological measurement

The rheological properties were measured using the method we previously reported [

14]. In brief, a DHR-2 rheometer with a parallel plate geometry of 45.0 mm in diameter, and a gap of 1.0 mm between the plate and sample stage was used. Prior to the measurement of the dynamic moduli, a linear viscoelastic region was determined at an angular frequency of 1.0 rad/s. The dynamic moduli, including the storage (G') and loss moduli (G''), were determined with the angular frequency of 0.1 to 100 rad/s. The temperature was maintained at 25 °C unless otherwise specified. The apparent viscosity was measured within the shear rate range of 0.1 to 100 s

-1 at 25°C.

2.6. Biodegradability of films

To study the final aerobic biodegradability of the films, the methodology of the UNE-EN ISO 17556 standard was adapted [

16]. In summary, this assay was carried out under controlled composting conditions to determine the total biodegradability of the films. A constant rate of N

2-O

2 (78/23 v/v) mixture was blown into the containers with the films for every 24 h, and the CO

2 was collected with NaOH solution and titrated. After 35 days of testing, the biodegradability of each film was calculated based on the amount of CO

2.

2.7. In-vitro cytotoxicity

The cytotoxicity of the CMC-based films to Human foreskin fibroblast cells (HFF-1) was evaluated by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) (Sigma, USA) method. The initial concentration of HFF-1 cell in cultural medium was 104 HFF-1 cells/mL, and the cells were cultured for 24 h in 96-well plates. The HFF-1celles were treated with the 100 μL of the film-forming solution for another 24 h, before 10 μL MTT with concentration of 5 mg/mL was added into each well of the 96-well plate, and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. Subsequently, the cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and dissolved in 100 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The absorbance was measured at 540 nm on a microplate reader (SpectraMax M5; Molecular Devices, USA).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effect of chitosan and cellulose derivative structures on rheological properties

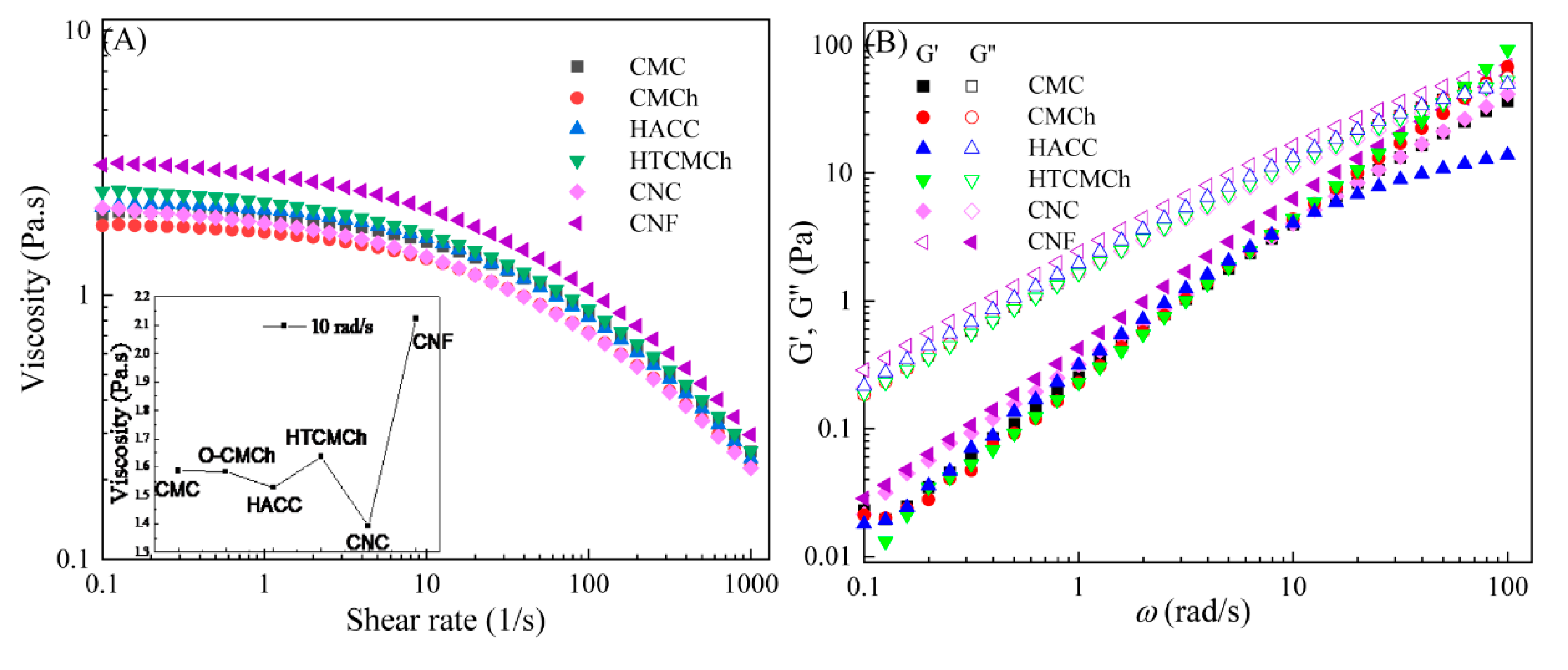

To investigate the effect of molecular structure on the rheological properties of CMC-based solutions, chitosan derivatives of HTCMCh, O-CMCh, HACC and cellulose derivatives of CNC and CNF with mass content of 1% were selected.

CMC solution exhibits Newtonian behavior at shear frequencies below 1 s

-1 and shear thinning behavior at frequencies above 1 s

-1, as shown in

Figure 1A. The Newtonian behavior corresponds to the insistence of hydrogen bonding and entanglement network between CMC molecular chains. With increasing shear rate, the hydrogen bonding is destroyed, as well as the entanglement network, leading to shear thinning behavior [

7,

11].

The introduction of HTCMCh, O-CMCh, HACC, CNC and CNF resulted in the variation of the CMC solution viscosity, however, they did not affect the Newtonian-shear thinning behavior of the solutions (

Figure 1A). All the chitosan and cellulose derivatives, except for O-CMCh, increased the viscosity of the CMC solution (the insert in Fig.1A). CNF showed the greatest enhancement to CMC solution viscosity, followed by HTCMCh, and CNC showed the least enhancement. It ascribed to the largest aspect ratio of CNF, except for large amount of hydrogen bonds, however, CNC possess the smallest one [

17]. It is noteworthy that the addition of HTCMCh resulted in an increase in the viscosity, while O-CMCh led to a slight decrease. This can be attributed to the different forces between O-CMCh and HTCMCh and CMC. The repulsion between CMC and O-CMCh may weaken the hydrogen bonds between CMC molecules, as a result the viscosity of CMC/O-CMCh solution decreases. HTCMCh is a kind of amphiphilic chitosan derivatives, quaternary ammonium salt groups in HTCMCh interact with the carboxyl groups in CMC, forming entanglement and increasing solution viscosity [

18].

The relationship between the shear rate and shear stress of CMC film-forming solutions was analyzed and fitted using a power-law model (Equation (1)).

Where ,, and n are shearing stress, consistency coefficient, shear rate and power-law exponent, respectively. When the value of n is less than 1, the solution exhibits shear thinning behavior.

The fitted parameters are consistent with the experimental data, such as all the power-law exponent values are less than 1, confirming the shear thinning behavior of the film-forming solutions. The consistency coefficient, viscosity at 1s-1 of CMC/CNF1% system is the largest, and those of CMC/CNC1% system is the lowest.

Table 1.

Parameters of CMC-based film-forming solutions fitted with power law model.

Table 1.

Parameters of CMC-based film-forming solutions fitted with power law model.

| Samples |

(Pa. s) |

n |

(Pa·s) |

(Pa·s) |

(Pa·s) |

| CMC |

6.9559 |

0.5321 |

1.8681 |

1.5866 |

0.8476 |

| CMC/O-CMCh1%

|

7.0044 |

0.5243 |

1.7254 |

1.5840 |

0.8279 |

| CMC/O-CMCh5%

|

6.2411 |

0.5459 |

1.7680 |

1.4569 |

0.8067 |

| CMC/O-CMCh10%

|

6.8765 |

0.5391 |

1.9459 |

1.5886 |

0.8636 |

| CMC/HTCMCh1%

|

6.7830 |

0.5249 |

2.2382 |

1.5275 |

0.8043 |

| CMC/HTCMCh5%

|

7.0774 |

0.5316 |

2.0604 |

1.6338 |

0.8595 |

| CMC/HTCMCh10%

|

6.4761 |

0.5434 |

1.8805 |

1.5285 |

0.8260 |

| CMC/HACC1%

|

7.1250 |

0.5195 |

2.0952 |

1.6355 |

0.8237 |

| CMC/HACC5%

|

10.5533 |

0.4723 |

4.1827 |

2.4424 |

0.9936 |

| CMC/HACC10%

|

10.1251 |

0.4630 |

5.0657 |

2.4074 |

0.9069 |

| CMC/CNC1%

|

5.7862 |

0.5361 |

1.9923 |

1.3922 |

0.7148 |

| CMC/CNC5%

|

7.6036 |

0.5203 |

2.3339 |

1.7777 |

0.8841 |

| CMC/CNC10%

|

8.8637 |

0.5168 |

2.5765 |

1.9835 |

1.0099 |

| CMC/CNF1%

|

9.4362 |

0.5096 |

2.8358 |

2.1238 |

1.0484 |

| CMC/CNF5%

|

8.8237 |

0.5054 |

2.6472 |

1.9926 |

0.9598 |

| CMC/CNF10%

|

6.8930 |

0.5299 |

2.1640 |

1.6343 |

0.8308 |

The viscoelastic moduli of CMC and CMC/additives1% solutions are shown in

Figure 1B, which shows that all the storage moduli (G″) is higher than that of elastic moduli (G′). According to previous work, the viscoelastic properties of CMC solutions are mainly related to the changes of CMC concentration [

19]. Benchabane et al. [

20] also revealed that CMC solutions showed viscous properties at concentrations of 1 wt% and 3 wt%. Additives can alter the properties of solutions, but they typically do not affect the fundamental characteristics of the liquid, such as the viscosity and elasticity modulus [

21]. These two parameters are important for describing the flow and deformation behavior of liquids, and are related to the intermolecular interactions within the liquid [

22]. When the angular frequencies were 50.12 rad/s, the elastic moduli of CMC/HTCMCh

1% and CMC/O-CMCh

1% film-forming solutions exceed the viscous ones, which can be attributed to intermolecular interactions.

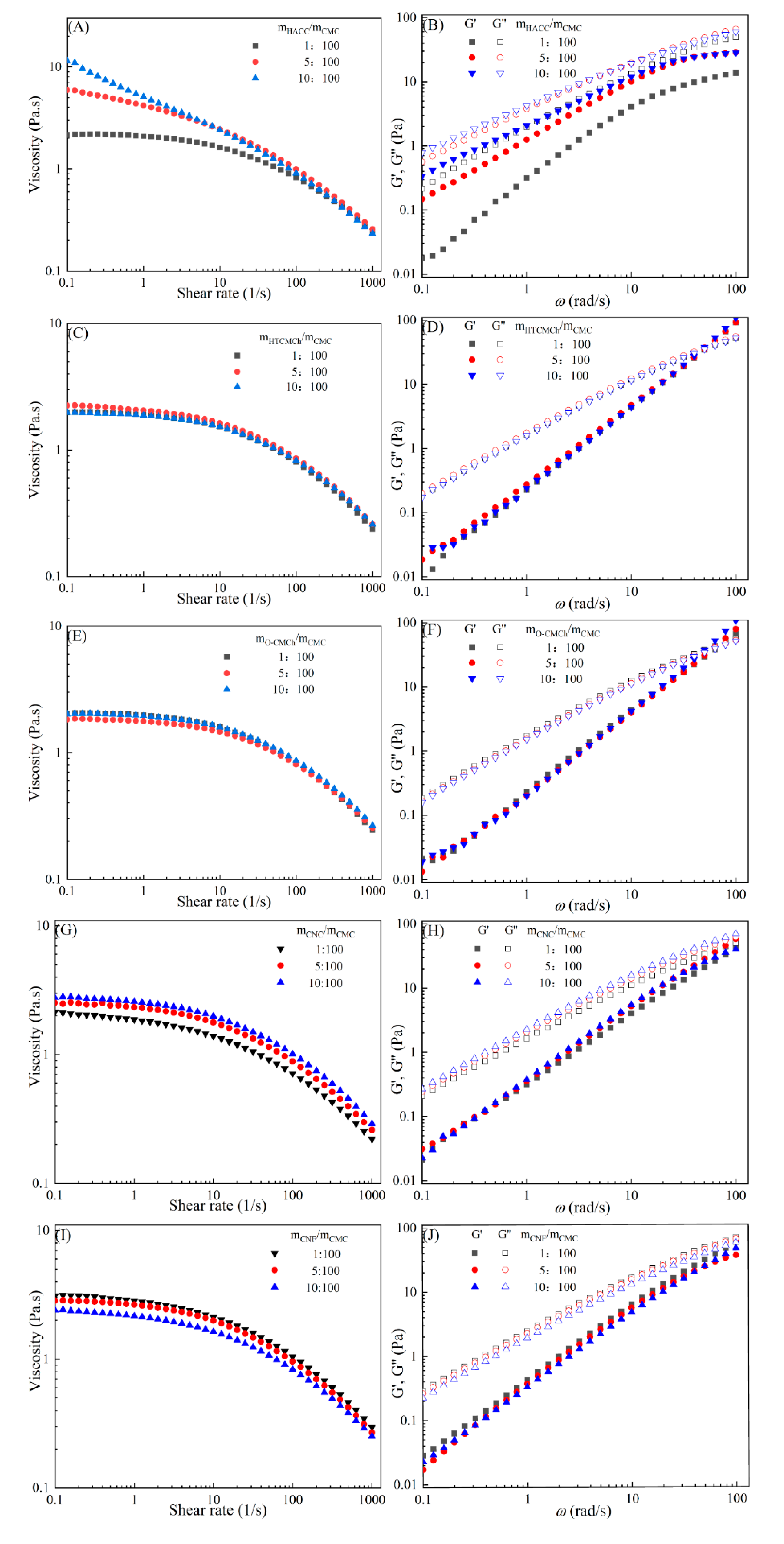

3.2. Effect of derivative concentration on rheological properties

The rheological behaviors of CMC-based film-forming solutions with different content of chitosan and cellulose derivatives are shown in

Figure 2. The content of HACC shows notable influence on viscosity of CMC/HACC film-forming solutions within shear rate of 0.1-100 s

-1. When the concentration of HACC is increased from 1% to 10%, the viscosity of the solution increased rapidly from 2.09 to 5.07 Pa·s (

Figure 2A). The contents of CNC and CNF show small influence on rheological properties of film-forming solutions (

Figure 2G,I), and those of HTCMCh and O-CMCh only a little influence (

Figure 2C,E). As is known that HACC is a kind of cationic chitosan derivatives, which can interact with CMC through electrostatic forces, however, O-CMCh is a kind of anionic chitosan derivatives, which has very strong electrostatic repulsion with CMC. HTCMCh is a kind of amphiphilic chitosan derivatives, and there are intra- and inter-molecular electrostatic interactions at a large content. In short, HACC increases the viscosity of the film-forming solutions through electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding, which also results in the lowest onset rate of shear thinning behavior among all the film-forming solutions [

18]. Similar phenomena have been observed in other systems [

17,

23]. For HTCMCh and O-CMCh, there is a balance between the hydrogen bond between HTCMCh and O-CMCh and CMC, and the shielding effect of –COO

- groups [

24]. In this work, the two effects are evenly matched. CNC and CNF influence the viscosity of CMC-based film-forming solution through their physical obstacles and forming a large number of hydrogen bonds with CMC [

25].

The viscoelasticity of the CMC/HACC film-forming solution is significantly affected by the content of HACC within the angular frequency from 0.1 to 100 rad/s. When the content of HACC increased from 1% to 10%, the storage modulus increased from 4.06 to 11.93 Pa (

Figure 2B). This is due to the strong electrostatic interaction between the quaternary ammonium groups in HACC and carboxyl groups in CMC, making the physical interactions between molecules stronger [

26]. Small amount of HACC could induce CMC aggregate, which increases the strength of the interactions and enhances the physical correlation effect between the aggregates [

27]. As a result, the storage modulus of CMC/HACC film-forming solution increases. The addition of O-CMCh and HTCMCh, as well as CNC and CNF, had little effect on the storage moduli (

Figure 2D,F,H,J). On the one hand, it is due to the presence of electrostatic repulsion between the macromolecules, and on the other hand, it is the competition between the additives and CMC molecules, decreasing the intramolecular hydrogen bonding of CMC molecules [

28,

29].

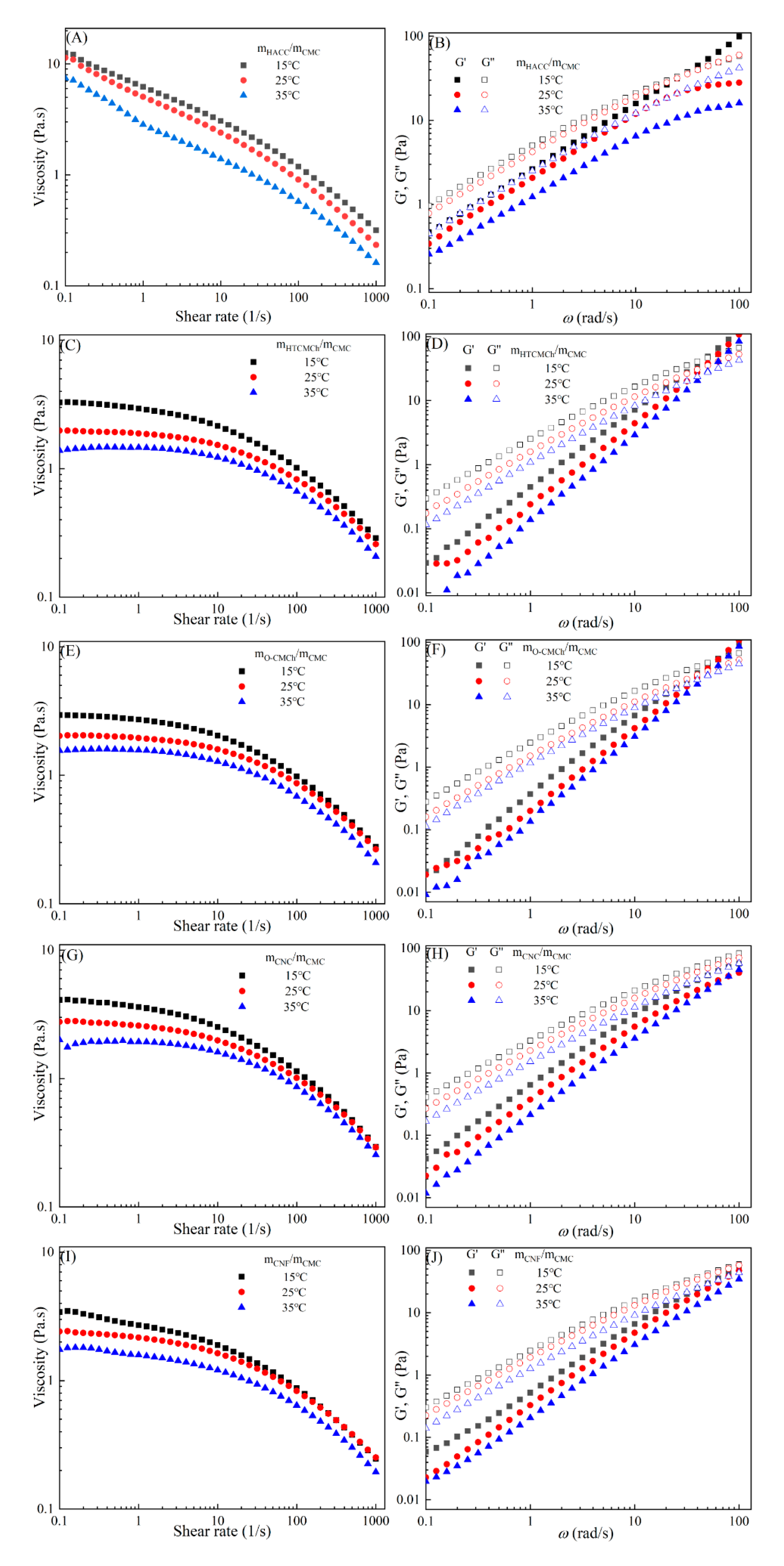

3.3. Effect of temperature on rheological properties

Figure 3 demonstrates that the viscosities and dynamic moduli of CMC-based film-forming solutions decrease with an increase in temperature, which are typical temperature-dependent behaviors [

30,

31]. As temperature increases, the decrease in viscosity can be attributed to an increase in molecular free volume and a corresponding decrease in intermolecular interactions [

32,

33]. The increase in temperature raises the average kinetic energy of molecules, which in turn increases the average distance between them, leading to an increase in their free volume [

34]. This temperature-dependent behavior also influences the viscoelastic properties. At lower temperatures, CMC molecules are mainly in a condensed state, and the intermolecular interactions between them are strong, resulting in a higher storage modulus [

35]. However, as temperature increases, a large amount of thermal energy is input into the system, resulting in enhanced molecular vibrations and increased molecular freedom for CMC molecules [

36]. Therefore, the intermolecular interaction forces decrease, leading to a decrease in storage modulus of CMC. In addition, under high temperature conditions, CMC molecules are more prone to rheological instability, which may also contribute to the decrease in storage modulus [

37]. CMC may undergo chemical degradation under different temperature, which may further affect the change in storage modulus [

38].

Table 2.

Rheological parameters of CMC-based film-forming solutions were calculated at different temperatures using the power law.

Table 2.

Rheological parameters of CMC-based film-forming solutions were calculated at different temperatures using the power law.

| Samples |

(Pa. s) |

n |

(Pa·s) |

(Pa·s) |

(Pa·s) |

T (℃) |

| CMC/O-CMCh10%

|

8.7973 |

0.5099 |

2.7071 |

2.0333 |

0.9783 |

15 |

| CMC/O-CMCh10%

|

6.8765 |

0.5391 |

1.9459 |

1.5886 |

0.8636 |

25 |

| CMC/O-CMCh10%

|

5.5768 |

0.5362 |

1.5683 |

1.2776 |

0.6837 |

35 |

| CMC/HTCMCh10%

|

9.2297 |

0.5082 |

2.9375 |

2.1512 |

1.0171 |

15 |

| CMC/HTCMCh10%

|

6.4761 |

0.5434 |

1.8805 |

1.5285 |

0.8260 |

25 |

| CMC/HTCMCh10%

|

5.2879 |

0.5415 |

1.4607 |

1.2248 |

0.6657 |

35 |

| CMC/HACC10%

|

11.1922 |

0.4578 |

6.2172 |

3.0673 |

1.1879 |

15 |

| CMC/HACC10%

|

10.1251 |

0.4631 |

5.0656 |

2.4074 |

0.9069 |

25 |

| CMC/HACC10%

|

5.6527 |

0.4937 |

2.8466 |

1.3937 |

0.5750 |

35 |

| CMC/CNC10%

|

11.5919 |

0.4808 |

3.6063 |

2.5182 |

0.8147 |

15 |

| CMC/CNC10%

|

8.8637 |

0.5168 |

2.5765 |

1.9835 |

1.0099 |

25 |

| CMC/CNC10%

|

7.1385 |

0.5287 |

1.9328 |

1.6053 |

0.8605 |

35 |

| CMC/CNF10%

|

8.0515 |

0.5042 |

2.7048 |

1.8902 |

0.8744 |

15 |

| CMC/CNF10%

|

6.8930 |

0.5299 |

2.1640 |

1.6343 |

0.8308 |

25 |

| CMC/CNF10%

|

5.2780 |

0.5327 |

1.5827 |

1.2078 |

0.6411 |

35 |

The increase in temperature also results in a slight increase in the values of n, and a notable decrease in

[

12]. This suggests that an increase in temperature can reduce the degree of shear thinning and viscosity. Both the shear thinning behavior and viscosity depend on intermolecular and intramolecular interactions. The CMC/HACC

10%,15℃ system exhibits the highest

value, which may be attributed to the strong electrostatic interaction between HACC and CMC. According to Yang et al., the strong interaction between HACC/CMC and the reorganization of the chains allows the apparent viscosity of the hybrid system to be preserved even as the temperature increases [

18].

3.4. Morphology, thickness, whiteness, transmittance, and wettability of CMC-based films

The film-forming solutions with chitosan and cellulose were used to prepared CMC-based films. Take the films of CMC/HTCMCh and CMC/CNF films as examples (

Figure 4), the films are good at transparency. The results are similar to those polysaccharide-based films, which is attributed to the good compatibility of CMC with chitosan and cellulose derivatives [

39]. Zhang and Jin also reported that the microstructure (cross section) of CMC/cationic chitosan derivative film showed a rough structure, while the CMC/cellulose derivative film showed small amount of cracks [

39,

40]. The rough structures are attributed to the aggregates of CMC-cationic chitosan derivative resulted from the electrostatic interaction between cationic groups in chitosan derivative and

groups in CMC [

41]. The small amount of cracks in CMC/cellulose derivative film is caused by hydrogen bonding effect and nanoparticle effect [

14]. In addition, the microscopic morphology of CMC-based films can be influenced by various factors, including film-forming conditions, plasticizers, degree of substitution, molecular weight of CMC, and the interaction between CMC and additives [

42].

The thickness of CMC film is listed in

Table 3, where one can find that both the HTCMCh and HACC decrease the thickness of the films, on the contrary, HACC, CNC and CNF increase the thickness.

It is reported that film thickness depends on the natural properties of film-forming materials, the alignment/interaction between these materials, and the concentration of additives [

41]. CMC and HTCMCh are both water-soluble and contain groups with opposite charges in the two macromolecules. In other words, strong electrostatic interactions between these two macromolecules dominate their arrangement, and HACC is the same [

43]. Under a high mass ratio of HTCMCh and HACC (e.g., 10%), the electrostatic interactions between the molecules and hydrogen bonding induce tight cross-linking between the two macromolecules. Therefore, the thickness of CMC/HTCMCh and CMC/HACC films decreases with the increase of additives. CMC and O-CMCh, CNC, CNF contain the same negative charge groups. Therefore, with the increase of O-CMCh, CNC, and CNF content, the electrostatic interactions between the molecules weaken, resulting in an increase in film thickness.

The intermolecular interaction and arrangement of the macromolecules in the films also affect the surface properties, including wettability and water vapor permeability. The contact angles of the films are listed in

Table 3. All the CMC-based films are hydrophilic, and with the increase of HTCMCh and HACC contents, the contact angles of CMC-based films increase. However, with increasing O-CMCh, CNC, and CNF content, the contact angle of CMC-based films decreases. This was ascribed to the different intermolecular interactions as the thickness changes. These results are consistent with those in the N-(2-hydroxypropyl)-3-trimethylammonium chitosan (HTCC)/CMC film [

18] and the tea polyphenol/hydroxypropyl starch film [

44].

The whiteness and transmittance of the control CMC film are 35.34±0.13 and 92.72±0.16, respectively. The addition of chitosan derivatives and cellulose has almost no effect on the whiteness and transparency of CMC-based films (

Table 3), which is confirmed from the optical appearance in

Figure 4. This means there is good compatibility of the two biomacromolecules.

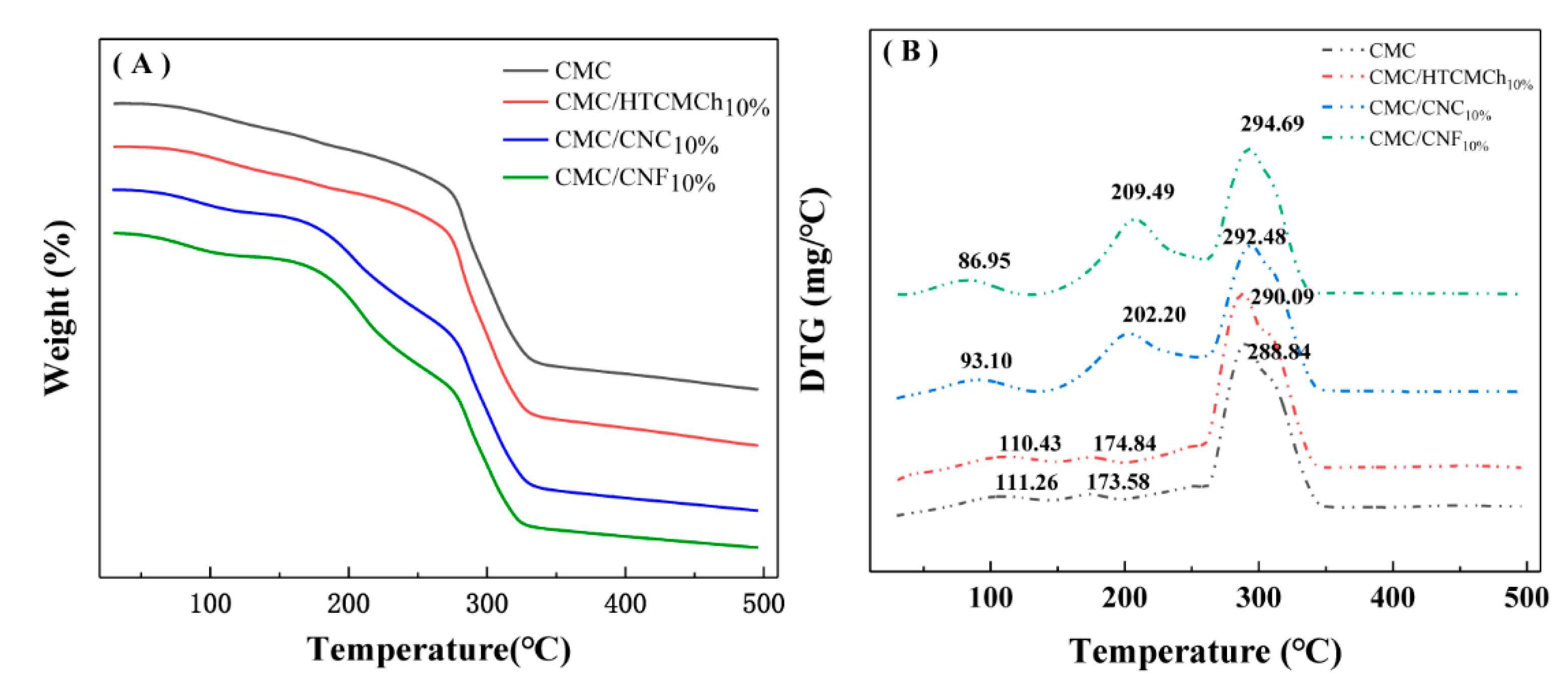

3.5. Thermodynamic properties of CMC-based films

The intermolecular interactions of CMC-based films are also reflected in the TGA curves. The thermal gravimetric results of CMC-based films are shown in

Figure 5. DTG curves are more sensitive than that of TGA ones. The DTG curve of pure CMC film exhibits three distinct peaks corresponding to the evaporation of bound water and the dissociation of hydrogen bonds (111℃), the evaporation of internal water (173℃), and the decomposition of the cellulose chain (288℃), respectively. [

40].

The interaction between the additives and CMC, such as hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interaction, can improve the thermal stability of composite films. However, the destruction of intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonds and the formation of discontinuous structures can decrease the thermal stability properties of CMC. The addition of 10% HTCMCh did not have a significant effect on the thermal stability of CMC, while the presence of 10% nanocellulose (CNC and CNF) enhanced the encapsulation of water by the composite film, resulting in a higher evaporation temperature of the encapsulated water. The CMC/CNF

10% and CMC/CNC

10% films exhibit a higher maximum decomposition temperature (292.48℃ and 294.60℃, respectively). The addition of nanocellulose can effectively increase the maximum decomposition temperature of CMC composite films, which may be due to a small specific surface area and size of nanocellulose [

40]. The filling effect of nanocellulose on CMC and the strong hydrogen bond with CMC may hinder the relative motion between molecules, thereby increasing the maximum decomposition temperature of the composite films [

14]. The electrostatic interaction between CMC and cationic polymers can effectively improve the thermodynamic properties of CMC films. For example, HACC can effectively increase the maximum decomposition temperature of CMC films [

18] and HTCMCh can improve the glass transition temperature of CMC films from 56.5℃ to 90.2℃ [

41]. Electrostatic repulsive interactions between CMC and CNC and CNF can result in the formation of pinholes and occasional slits in CMC-based films.

The stronger intermolecular interaction between CMC and 10% CNF, as well as the denser structure of the resulting CMC/CNF10% film, contribute to a higher maximum decomposition temperature compared to 10% CNC. This finding is consistent with the results of the rheology.

3.6. Mechanical properties of CMC-based films

Table 4 displays the tensile strength (TS), elongation at break (EB), and Young's modulus (E) of CMC-based films. The neat CMC film exhibits a tensile strength of 13.57 MPa and an elongation at break of 44.41±0.61%. The mechanical properties of CMC films are influenced by various factors, including the source of CMC, its molecular mass and distribution, and the conditions under which the film is formed [

41]. The addition of chitosan and cellulose derivatives results in an increase in the tensile strength of CMC-based films compared to pure CMC film (Table 4). Among the CMC-based films, the maximum tensile strength is observed in CMC/CNF

10% (42.41 MPa), followed by CMC/CNC

10% (32.22 MPa), while the minimum is observed in pure CMC (13.57 MPa). Additives typically interact with film-forming substrates through hydrogen bonds, which can enhance the tensile strength of the film [

45]. Tarrés et al. [

46] reported that CNF significantly improved the strength of paper due to its high surface area. The carboxylate and carboxymethyl groups in dense and layered fibers form more hydrogen bonds between nanofibers, thereby increasing the tensile strength.

In the current study, it is found that the tensile strength and elongation at break of CMC-based films are enhanced with the incorporation of O-CMCh and HTCMCh. According to previous reports [

41], the increase in tensile strength and elongation at break can be attributed to the biocompatibility, strong electrostatic interactions, and hydrogen bonding between O-CMCh and CMC. With the addition of HACC, CNC, and CNF, the elongation at break of CMC-based films decreases. This ascribes to the hydrogen bonds between the additive and the film-forming substrate limit their relative sliding possibility, leading to a decrease in elongation at break.

Young's modulus is a typical characteristic of material stiffness, the larger the Young's modulus is, the less deformability [

47]. The incorporation of O-CMCh and HTCMCh in CMC-based films results in a lower Young's modulus, which translates to better toughness, superior processability, and wider applicability. The CMC/CNF film exhibits a tensile strength of 42.41 MPa and a Young's modulus of 121.17 MPa, which are 13.57 MPa and 30.84 MPa higher than those of CMC film, respectively. These findings suggest that CMC/CNF film possesses superior mechanical properties and deformation resistance. Similar results were observed in CMC/HACC films [

48], CMC/CNC films [

49], and graphene oxide/carboxymethylcellulose/alginate composite blend films [

50].

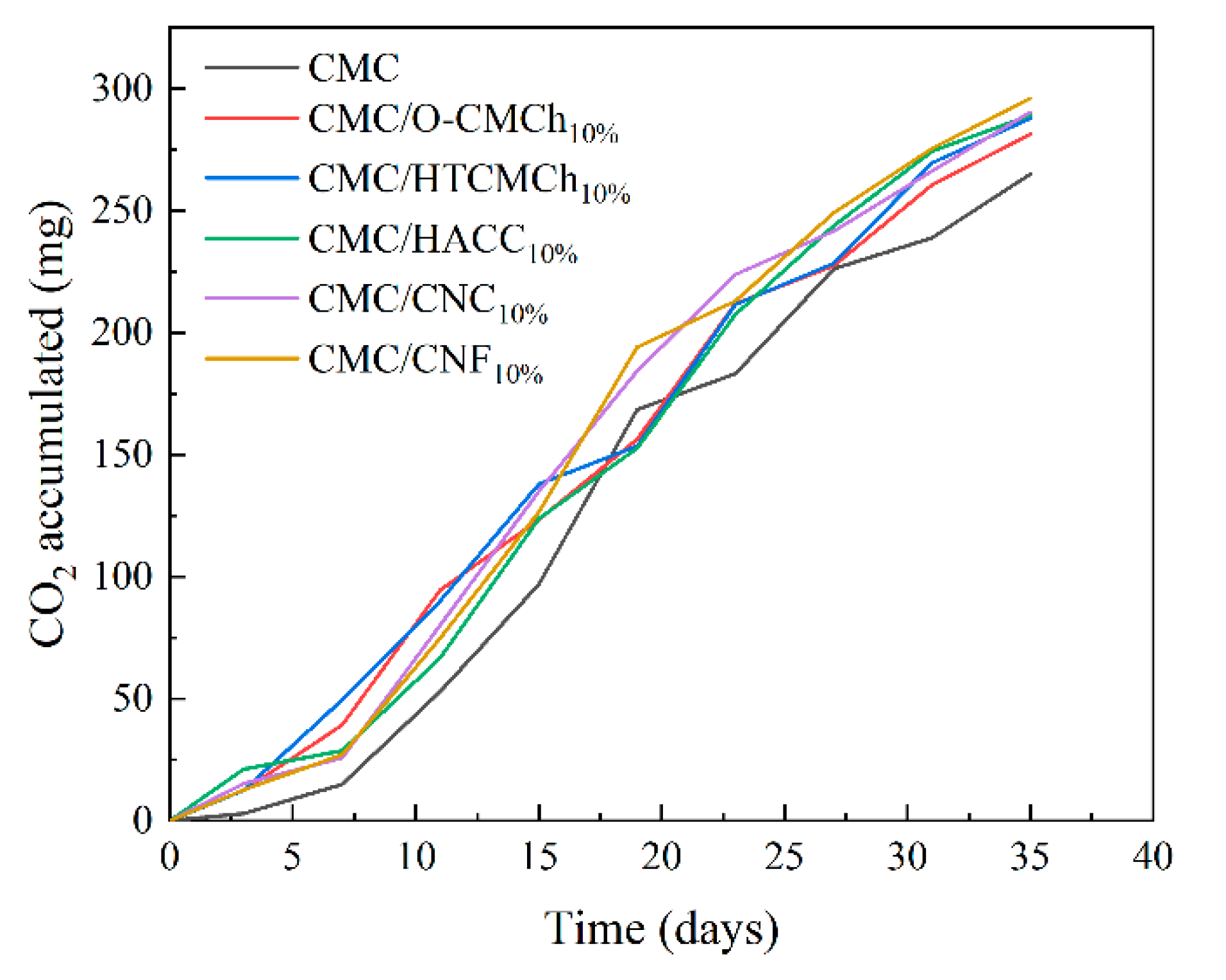

3.7. Biodegradability of CMC-based films

The films produced by adding chitosan and cellulose derivatives into CMC are suitable for various applications, including food packaging and drug delivery. However, the films should also be biodegradable to maintain its usability. This prompts us to evaluate the biodegradability of pure CMC film and CMC film containing chitosan and cellulose derivatives. CMC can be made more biodegradable by adding natural plasticizers [

51]. In the current, bio-based polylactic acid (PLA) was used as a control to evaluate if the level of biodegradability of our films was optimal compared to other materials already described as biodegradable [

52]. After 35 days of testing, the accumulated CO

2 (mg) values obtained were: 264.92 for CMC film, 281.45 for CMC/O-CMCh film, 287.78 for CMC/HTCMCh film, 289.08 for CMC/HACC film, 290.46 for CMC/CNC, 296.12 for CMC/CNF and 108.83 for PLA. Therefore, after 35 days, some of our films have already biodegraded more than PLA. The results obtained indicate that the biodegradability of our films was optimal. Furthermore, these findings support the use of the studied composites as a replacement for non-biodegradable, environmentally unfriendly plastics that can have additional harmful effects on both health and the economy.

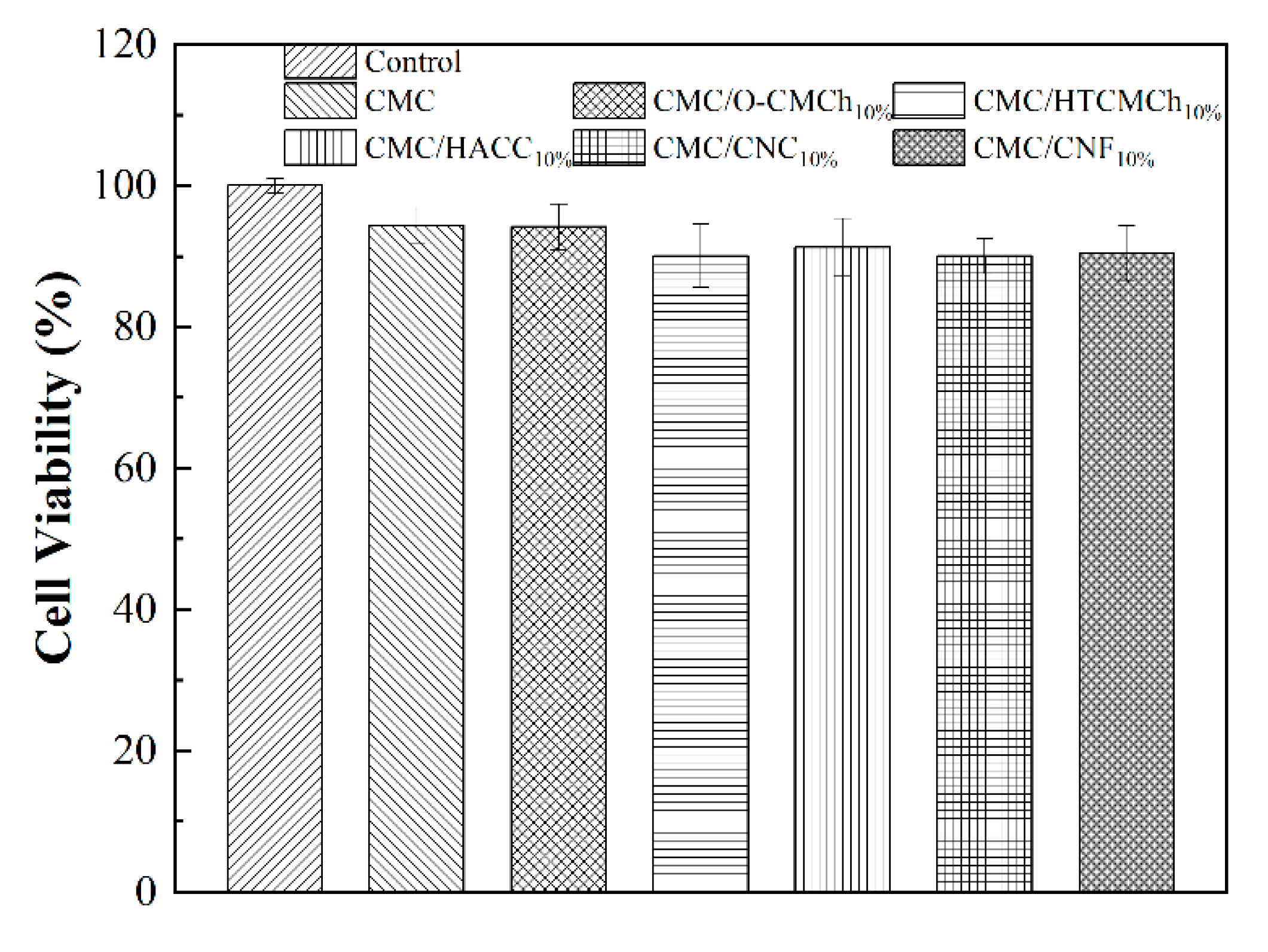

3.8. Cytotoxicity of CMC-based films

When considering the application of CMC-based films in food packaging and drug delivery, it is essential to evaluate their biocompatibility. The in-vitro cytotoxicity of CMC-based films was determined by MTT assay, with a concentration range of 0 (control sample) to 2.0 mg/mL. As shown in

Figure 7, the viability of cells on all films was greater than 90%, meaning that all CMC-based films were non-toxic and independent of the type of additive. This result is consistent with previous reports [

53,

54,

55], confirming the CMC-based films can be safely used as food packaging and drug delivery materials.

4. Conclusions

The rheological properties of CMC-based film-forming solutions were studied. The additives were O-CMCh, HTCMCh, HACC, CNC, and CNF. The results showed that all CMC-based film-forming solutions exhibited shear thinning behavior. The CMC-based film-forming solutions showed Newtonian plateau before 1s-1 followed by slight shear thinning behavior. The interaction between CMC and additives depends on the charge of the additives, for example, HACC and HTCMCh interact with CMC primarily through electrostatic interaction except for hydrogen bonds. O-CMCh, CNC and CNF interact with CMC mainly through hydrogen bonds. Both HTCMCh and CNF had a significant thickening effect on CMC solutions. The strong electrostatic force between HACC and CMC resulted in the loss of the original Newtonian plateau of CMC solutions at low shear frequencies. When HACC content reached to 5% and 10%, CMC solutions exhibited shear thinning behavior throughout the shear rate range of 0.1-100 s-l. The rheological properties showed that CMC and all the additives have good biocompatibility.

The films prepared from selected CMC-based film-forming solutions showed very high transmittance, hydrophilicity, improved thermal stability, enhanced tensile strength, good biocompatibility. These results also confirmed the good biocompatibility between CMC and the additives. The non-toxicity of the films suggest that the CMC-based films are potential food-packaging and drug delivery systems.

Author Contributions

Huatong Zhang, Shunjie Su, and Shuxia Liu studied the rheological properties; Congde Qiao guided the rheological experiments; Enhua Wang and Cangheng Zhang prepared films and characterized properties; Hua Chen participated the preparation of films and cytotoxicity tests; Xiaodeng Yang analyzed the experimental data, writing and reviewing the manusxript; Tianduo Li designed the experiments. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Financial support from Science, Education and Industry Integration Innovation Pilot Project from Qilu University of Technology & Shandong Academy of Sciences (2022JBZ02-04), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 52072190), and State Key Laboratory of Biobased Material and Green Papermaking (ZZ20210117).

Institutional Review Board Statement

applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of the colleagues from Qilu University of Technology, Shandong Academy of Sciences in experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Huang, Kehao, and Yixiang Wang. Recent Applications of Regenerated Cellulose Films and Hydrogels in Food Packaging. Current Opinion in Food Science 2022, 43, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Yaowen, Saeed Ahmed, Dur E. Sameen, Yue Wang, Rui Lu, Jianwu Dai, Suqing Li, and Wen Qin. A Review of Cellulose and Its Derivatives in Biopolymer-Based for Food Packaging Application. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 112, 532–546. [Google Scholar]

- Cazón, Patricia, and Manuel Vázquez. Bacterial Cellulose as a Biodegradable Food Packaging Material: A Review. Food Hydrocolloids 2021, 113, 106530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Derong, Yan Zheng, Xiao Wang, Yichen Huang, Long Ni, Xue Chen, Zhijun Wu, Chuanyan Huang, Qiuju Yi, Jingwen Li, Wen Qin, Qing Zhang, Hong Chen, and Dingtao Wu. Study on Physicochemical Properties, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Okara Soluble Dietary Fiber/Sodium Carboxymethyl Cellulose/Thyme Essential Oil Active Edible Composite Films Incorporated with Pectin. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 165, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef, Ahmed M. , and Samah M. El-Sayed. Bionanocomposites Materials for Food Packaging Applications: Concepts and Future Outlook. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 193, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idumah, Christopher Igwe, Azman Hassan, and David Esther Ihuoma. Recently Emerging Trends in Polymer Nanocomposites Packaging Materials. Polymer-Plastics Technology and Materials 58, no. 2019, 10, 1054–1109. [Google Scholar]

- An, Fangfang, Kuanjun Fang, Xiuming Liu, Chang Li, Yingchao Liang, and Hao Liu. Rheological Properties of Carboxymethyl Hydroxypropyl Cellulose and Its Application in High Quality Reactive Dye Inkjet Printing on Wool Fabrics. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 164, 4173–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, Vânia, Ana Sofia Pires, Nuno Mateus, Victor de Freitas, and Luís Cruz. Pyranoflavylium-Cellulose Acetate Films and the Glycerol Effect Towards the Development of Ph-Freshness Smart Label for Food Packaging. Food Hydrocolloids 2022, 127, 107501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, Carlos G. , and Walter Richtering. Oscillatory Rheology of Carboxymethyl Cellulose Gels: Influence of Concentration and Ph. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 267, 118117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalah, Kaci, Abdelbaki Benmounah, M'hamed Mahdad, and Rabia Kheribet. Rheological Study of Sodium Carboxymethylcellulose: Effect of Concentration and Molecular Weight. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 53, 185–190. [Google Scholar]

- Oguzlu, Hale, Christophe Danumah, and Yaman Boluk. The Role of Dilute and Semi-Dilute Cellulose Nanocrystal (Cnc) Suspensions on the Rheology of Carboxymethyl Cellulose (Cmc) Solutions. The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering 94, no. 2016, 10, 1841–1847. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Weijie, Fengying Zhang, Weiku Wang, Yinhui Li, Yaodong Liu, Chunxiang Lu, and Zhengfang Zhang. Rheological Transitions and in-Situ Ir Characterizations of Cellulose/Licl·Dmac Solution as a Function of Temperature. Cellulose 25, no. 2018, 9, 4955–4968. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Qun, Jialiang Chen, Xiaodeng Yang, Congde Qiao, Zhi Li, Chunlin Xu, Yan Li, and Jinling Chai. Synthesis, Structure, and Properties of N-2-Hydroxylpropyl-3-Trimethylammonium-O-Carboxymethyl Chitosan Derivatives. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 144, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Cangheng, Xiaodeng Yang, Yan Li, Shunping Wang, Yongchao Zhang, Huan Yang, Jinling Chai, and Tianduo Li. Multifunctional Hybrid Composite Films Based on Biodegradable Cellulose Nanofibers, Aloe Juice, and Carboxymethyl Cellulose. Cellulose 2021, 28, 4927–4941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Congde, Guangxin Chen, Jianlong Zhang, and Jinshui Yao. Structure and Rheological Properties of Cellulose Nanocrystals Suspension. Food Hydrocolloids 2016, 55, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Santos, Julia, Cristina Valls, Oriol Cusola, and M. Blanca Roncero. Improving Filmogenic and Barrier Properties of Nanocellulose Films by Addition of Biodegradable Plasticizers. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2021, 9, 9647–9660. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, Eronildo Alves, José Luis Dávila, and Marcos Akira d'Ávila. Rheological Studies on Nanocrystalline Cellulose/Alginate Suspensions. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2019, 277, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Beibei, Xiaodeng Yang, Congde Qiao, Yan Li, Tianduo Li, and Chunlin Xu. Effects of Chitosan Quaternary Ammonium Salt on the Physicochemical Properties of Sodium Carboxymethyl Cellulose-Based Films. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 184, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayarri, S., L. González-Tomás, and E. Costell. Viscoelastic Properties of Aqueous and Milk Systems with Carboxymethyl Cellulose. Food Hydrocolloids 2009, 23, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchabane, Adel, and Bekkour Karim. Rheological Properties of Carboxymethyl Cellulose (Cmc) Solutions. Colloid and Polymer Science 2008, 286, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanmohammadi, H., W. Wijanarko, and N. Espallargas. Ionic Liquids as Additives in Water-Based Lubricants: From Surface Adsorption to Tribofilm Formation. Tribology Letters 2020, 68, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzigiannakis, Emmanouil, Nick Jaensson, and Jan Vermant. Thin Liquid Films: Where Hydrodynamics, Capillarity, Surface Stresses and Intermolecular Forces Meet. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science 2021, 53, 101441. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, Karan, Amandeep, and Shivprasad Patil. Viscoelasticity and Shear Thinning of Nanoconfined Water. Physical Review E 2014, 89, 013004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Wenmeng, Rongrong Wang, Jinwang Li, Wenhao Xiao, Liyuan Rong, Jun Yang, Huiliang Wen, and Jianhua Xie. Effects of Different Hydrocolloids on Gelatinization and Gels Structure of Chestnut Starch. Food Hydrocolloids 2021, 120, 106925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Xiuxuan, Qinglin Wu, Xiuqiang Zhang, Suxia Ren, Tingzhou Lei, Wencai Li, Guangyin Xu, and Quanguo Zhang. Nanocellulose Films with Combined Cellulose Nanofibers and Nanocrystals: Tailored Thermal, Optical and Mechanical Properties. Cellulose 2018, 25, 1103–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Xiaolu, Yihan Li, Zhe Xu, Xuan Feng, Qingjun Kong, and Xueyan Ren. Efficient Binding Paradigm of Protein and Polysaccharide: Preparation of Isolated Soy Protein-Chitosan Quaternary Ammonium Salt Complex System and Exploration of Its Emulsification Potential. Food Chemistry 2023, 407, 135111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Dan, Xiuqin Bai, and Xiaoyan He. Research Progress on Hydrogel Materials and Their Antifouling Properties. European Polymer Journal 2022, 181, 111665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kötz, J., S. Kosmella, and T. Beitz. Self-Assembled Polyelectrolyte Systems. Progress in Polymer Science 2001, 26, 1199–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantero-López, Plinio, Mariel Godoy, Estefanía Oyarce, Guadalupe Del C. Pizarro, Chunlin Xu, Stefan Willför, Osvaldo Yañez, and Julio Sánchez. Removal of Nafcillin Sodium Monohydrate from Aqueous Solution by Hydrogels Containing Nanocellulose: An Experimental and Theoretical Study. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2022, 347, 117946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benslimane, Abdelhakim, Ilies Mohamed Bahlouli, Karim Bekkour, and Dalila Hammiche. Thermal Gelation Properties of Carboxymethyl Cellulose and Bentonite-Carboxymethyl Cellulose Dispersions: Rheological Considerations. Applied Clay Science 2016, 132-133, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancela, M. A., E. Álvarez, and R. Maceiras. Effects of Temperature and Concentration on Carboxymethylcellulose with Sucrose Rheology. Journal of Food Engineering 2005, 71, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, María, Adriaan van den Bruinhorst, and Maaike C. Kroon. Low-Transition-Temperature Mixtures (Lttms): A New Generation of Designer Solvents. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2013, 52, 3074–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, S. , and Kundan Sharma. Effect of Temperature and Additives on the Critical Micelle Concentration and Thermodynamics of Micelle Formation of Sodium Dodecyl Benzene Sulfonate and Dodecyltrimethylammonium Bromide in Aqueous Solution: A Conductometric Study. The Journal of Chemical Thermodynamics 2014, 71, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Miri, Nassima, Karima Abdelouahdi, Abdellatif Barakat, Mohamed Zahouily, Aziz Fihri, Abderrahim Solhy, and Mounir El Achaby. Bio-Nanocomposite Films Reinforced with Cellulose Nanocrystals: Rheology of Film-Forming Solutions, Transparency, Water Vapor Barrier and Tensile Properties of Films. Carbohydrate Polymers 2015, 129, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abutalib, M. M. Effect of Zinc Oxide Nanorods on the Structural, Thermal, Dielectric and Electrical Properties of Polyvinyl Alcohol/Carboxymethyle Cellulose Composites. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2019, 557, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oomens, Jos, Boris G. Sartakov, Gerard Meijer, and Gert von Helden. Gas-Phase Infrared Multiple Photon Dissociation Spectroscopy of Mass-Selected Molecular Ions. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry 2006, 254, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Weiss, A., V. Bifani, M. Ihl, P. J. A. Sobral, and M. C. Gómez-Guillén. Polyphenol-Rich Extract from Murta Leaves on Rheological Properties of Film-Forming Solutions Based on Different Hydrocolloid Blends. Journal of Food Engineering 2014, 140, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Britto, Douglas, and Odílio B. G. Assis. Thermal Degradation of Carboxymethylcellulose in Different Salty Forms. Thermochimica Acta 2009, 494, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Xiangxiang, Wei Lu, Cuixia Sun, Hoda Khalesi, Analucia Mata, Rani Andaleeb, and Yapeng Fang. Cellulose and Cellulose Derivatives: Different Colloidal States and Food-Related Applications. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 255, 117334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hyun-Ji, Swarup Roy, and Jong-Whan Rhim. Effects of Various Types of Cellulose Nanofibers on the Physical Properties of the Cnf-Based Films. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2021, 9, 106043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Cangheng, Xiaodeng Yang, Yan Li, Congde Qiao, Shoujuan Wang, Xiaoju Wang, Chunlin Xu, Huan Yang, and Tianduo Li. Enhancement of a Zwitterionic Chitosan Derivative on Mechanical Properties and Antibacterial Activity of Carboxymethyl Cellulose-Based Films. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 159, 1197–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macieja, Szymon, Bartosz Środa. Bioactive Carboxymethyl Cellulose (Cmc)-Based Films Modified with Melanin and Silver Nanoparticles (Agnps)&Mdash;the Effect of the Degree of Cmc Substitution on the in Situ Synthesis of Agnps and Films&Rsquo; Functional Properties. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, J. Andrés, Betty Matsuhiro, Paula A. Zapata, Teresa Corrales, and Fernando Catalina. Preparation and Characterization of Maleoylagarose/Pnipaam Graft Copolymers and Formation of Polyelectrolyte Complexes with Chitosan. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 182, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Mingyue, Long Yu, Peitao Zhu, Xiangping Zhou, Hongsheng Liu, Yunyi Yang, Jiaqiao Zhou, Chengcheng Gao, Xianyang Bao, and Pei Chen. Development and Preparation of Active Starch Films Carrying Tea Polyphenol. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 196, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Yaqing, Yingnan Liu, Shufang Kang, and Huaide Xu. Insight into the Formation Mechanism of Soy Protein Isolate Films Improved by Cellulose Nanocrystals. Food Chemistry 2021, 359, 129971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarrés, Q., M. Delgado-Aguilar, M. A. Pèlach, I. González, S. Boufi, and P. Mutjé. Remarkable Increase of Paper Strength by Combining Enzymatic Cellulose Nanofibers in Bulk and Tempo-Oxidized Nanofibers as Coating. Cellulose 2016, 23, 3939–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfenyuk, Elena V. , and Ekaterina S. Dolinina. Silica Hydrogel Composites as a Platform for Soft Drug Formulations and Cosmetic Compositions. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2022, 287, 126160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Fang, Qian Zhang, Kexin Huang, Jiarui Li, Kun Wang, Kai Zhang, and Xinyue Tang. Preparation and Characterization of Carboxymethyl Cellulose Containing Quaternized Chitosan for Potential Drug Carrier. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 154, 1392–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Mei-Chun, Changtong Mei, Xinwu Xu, Sunyoung Lee, and Qinglin Wu. Cationic Surface Modification of Cellulose Nanocrystals: Toward Tailoring Dispersion and Interface in Carboxymethyl Cellulose Films. Polymer 2016, 107, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, Mithilesh, Kyong Yop Rhee, and S. J. Park. Synthesis and Characterization of Graphene Oxide/Carboxymethylcellulose/Alginate Composite Blend Films. Carbohydrate Polymers 2014, 110, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaradoddi, Jayachandra S. , Nagaraj R. Banapurmath, Sharanabasava V. Ganachari, Manzoore Elahi M. Soudagar, N. M. Mubarak, Shankar Hallad, Shoba Hugar, and H. Fayaz. Biodegradable Carboxymethyl Cellulose Based Material for Sustainable Packaging Application. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 21960. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, Seth, Elisabeth Van Roijen, Cecily Ryan, and Sabbie Miller. Reducing the Environmental Impacts of Plastics While Increasing Strength: Biochar Fillers in Biodegradable, Recycled, and Fossil-Fuel Derived Plastics. Composites Part C: Open Access 2022, 8, 100253. [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa Leal, Antonia, Ricardo de Araújo, Grasielly Rocha Souza, Gláucia Laís Nunes Lopes, Sean Telles Pereira, Michel Muálem de Moraes Alves, Humberto Medeiros Barreto, André Luís Menezes Carvalho, Paulo Michel Pinheiro Ferreira, Davi Silva, Fernando Aécio de Amorim Carvalho, José Arimateia Dantas Lopes, and Lívio César Cunha Nunes. In Vitro Bioactivity and Cytotoxicity of Films Based on Mesocarp of Orbignya Sp. And Carboxymethylcellulose as a Tannic Acid Release Matrix. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 201, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Fang, Qian Zhang, Xinxia Li, Kexin Huang, Wei Shao, Dawei Yao, and Chaobo Huang. Redox-Responsive Blend Hydrogel Films Based on Carboxymethyl Cellulose/Chitosan Microspheres as Dual Delivery Carrier. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 134, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, Mahdiyar, Seyed Javad Ahmadi, Amirhossein Seif, and Ghadir Rajabzadeh. Carboxymethyl Cellulose Film Modification through Surface Photo-Crosslinking and Chemical Crosslinking for Food Packaging Applications. Food Hydrocolloids 2016, 61, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Apparent viscosity(A) and viscoelastic moduli (B) of CMC-based film-forming solutions at 25℃. The insert in A is the viscosities of the film-forming solutions at shear rate of 1s-1. The content of HTCMCh, O-CMCh, HACC, CNC and CNF were 1%.

Figure 1.

Apparent viscosity(A) and viscoelastic moduli (B) of CMC-based film-forming solutions at 25℃. The insert in A is the viscosities of the film-forming solutions at shear rate of 1s-1. The content of HTCMCh, O-CMCh, HACC, CNC and CNF were 1%.

Figure 2.

Apparent viscosity (A, C, E, G, I) and viscoelastic moduli (B, D, F, H, J) of CMC-based film-forming solutions with different amounts of additives at 25℃.

Figure 2.

Apparent viscosity (A, C, E, G, I) and viscoelastic moduli (B, D, F, H, J) of CMC-based film-forming solutions with different amounts of additives at 25℃.

Figure 3.

Apparent viscosity (A, C, E, G, I) and viscoelastic moduli (B, D, F, H, J) of CMC solutions with 10% additives (HACC, HTCMCh, O-CMCh, CNC, and CNF) at different temperature.

Figure 3.

Apparent viscosity (A, C, E, G, I) and viscoelastic moduli (B, D, F, H, J) of CMC solutions with 10% additives (HACC, HTCMCh, O-CMCh, CNC, and CNF) at different temperature.

Figure 4.

Cross-sectional topography images of CMC/HTCMCh (A) and CMC/CNF (B). The background contents have been authorized by publisher [

14,

41].

Figure 4.

Cross-sectional topography images of CMC/HTCMCh (A) and CMC/CNF (B). The background contents have been authorized by publisher [

14,

41].

Figure 5.

TGA(A) and DTG(B) cures of CMC-based films.

Figure 5.

TGA(A) and DTG(B) cures of CMC-based films.

Figure 6.

Biodegradability, in terms of CO2 accumulation, of CMC-based films.

Figure 6.

Biodegradability, in terms of CO2 accumulation, of CMC-based films.

Figure 7.

In vitro cytotoxicity of CMC-based films.

Figure 7.

In vitro cytotoxicity of CMC-based films.

Table 3.

Thickness (Th), contact angle (θ), whiteness (W), transparency (Tr), tensile strength (TS), elongation at break (EB) and Young’s modulus (E) of the CMC-based films.

Table 3.

Thickness (Th), contact angle (θ), whiteness (W), transparency (Tr), tensile strength (TS), elongation at break (EB) and Young’s modulus (E) of the CMC-based films.

| Films |

Th (mm) |

θ (º) |

W (%) |

Tr (%) |

TS (MPa) |

EB (%) |

E (MPa) |

| CMC |

0.126±0.015 |

44.3±1.4 |

35.34±0.13 |

92.72±0.16 |

13.57±0.47 |

44.41±0.61 |

30.84±0.96 |

| CMC/O-CMCh1%

|

0.129±0.032 |

50.6±0.61 |

35.73±0.08 |

93.63±0.14 |

13.62±0.17 |

49.64±0.32 |

27.79±0.53 |

| CMC/O-CMCh5%

|

0.135±0.027 |

47.6±0.58 |

36.53±0.16 |

93.67±0.15 |

13.66±0.31 |

54.87±0.19 |

24.84±0.89 |

| CMC/O-CMCh10%

|

0.142±0.010 |

40.2±0.21 |

35.87±0.18 |

93.33±0.09 |

13.69±0.11 |

58.88±0.41 |

23.25±0.98 |

| CMC/HTCMCh1%

|

0.143±0.015 |

46.4±1.7 |

35.30±0.36 |

93.42±0.36 |

13.65±0.08 |

60.75±0.56 |

22.75±0.68 |

| CMC/HTCMCh5%

|

0.139±0.008 |

54.4±2.3 |

36.63±0.41 |

94.76±0.13 |

13.57±0.14 |

62.24±0.53 |

21.88±0.65 |

| CMC/HTCMCh10%

|

0.128±0.032 |

57.4±1.8 |

34.15±0.42 |

93.65±0.08 |

13.78±0.08 |

64.66±0.17 |

21.54±0.64 |

| CMC/HACC1%

|

0.148±0.012 |

44.6±0.61 |

35.83±0.15 |

93.54±0.17 |

15.65±0.17 |

42.93±0.23 |

36.45±0.82 |

| CMC/HACC5%

|

0.142±0.018 |

50.3±0.52 |

36.33±0.26 |

93.53±0.09 |

18.54±0.13 |

41.72±0.32 |

44.45±0.96 |

| CMC/HACC10%

|

0.138±0.032 |

55.2±0.45 |

36.20±0.08 |

92.07±0.12 |

20.51±0.27 |

40.08±0.03 |

51.17±0.78 |

| CMC/CNC1%

|

0.146±0.031 |

46.2±2.9 |

35.63±0.36 |

92.16±0.33 |

20.32±0.28 |

43.05±0.18 |

47.21±0.77 |

| CMC/CNC5%

|

0.152±0.036 |

45.4±1.3 |

35.54±0.12 |

93.77±0.05 |

26.76±0.62 |

42.21±0.02 |

63.39±0.65 |

| CMC/CNC10%

|

0.160±0.019 |

39.3±1.6 |

36.25±0.23 |

91.22±0.18 |

32.22±0.37 |

40.81±0.49 |

78.93±0.84 |

| CMC/CNF1%

|

0.145±0.012 |

46.9±0.9 |

35.54±0.11 |

93.05±0.16 |

28.35±0.31 |

40.07±0.13 |

70.75±0.83 |

| CMC/CNF5%

|

0.156±0.036 |

43.5±0.55 |

36.27±0.13 |

93.77±0.05 |

36.45±0.29 |

37.72±0.21 |

96.63±0.96 |

| CMC/CNF10%

|

0.161±0.021 |

38.7±0.6 |

36.16±0.16 |

92.22±0.28 |

42.41±0.46 |

34.74±0.33 |

121.17±0.94 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).