1. Introduction

Mulberry is a tree species widely distributed in Asia, Europe, Africa and other regions. With high growth speed, robust adaptability and long service life, it is a tree species with high ecological and economic benefits [

1]. Its fruits and leaves contain rich metabolites, thus having high nutritional value. Mulberry not only has edible value but also serves as the primary food for silkworms and is an important raw material for silk production. Mulberry trees have hard and durable wood that can be used to make furniture, and building materials [

2]. The most common mulberry species in Mori are red, white, and

Morus alba L. [

3]. Many Native American tribes use red mulberry to treat various diseases, and the juice of red mulberry is used to treat tinea [

4]. White mulberry can grow in different environmental conditions and climate change. Many European countries, such as Turkey and Greece, planted mulberry for food and the preparation of mulberry juice [

5]. More than two thousand years ago, people raised silkworms with mulberry leaves in China. The traditional mulberry silk industry opened the world-famous Silk Road [

6]. It has produced a profound influence on human society's development. Different from red mulberry and white mulberry,

Morus alba L. not only has edible fruits but also has been found in recent years to have the effects of treating diabetes and anti-cancer [

7,

8].

Morus nigra L., also known as Medicine mulberry, originated in Iran. After it was introduced into China along the Silk Road, it was often used to clear heat and detoxify, relieve cough and dissolve phlegm, and treat cold, cough, fever, dysentery and other diseases. Uighurs in southern Xinjiang are known as holy fruit and enjoy a sacred status [

9]. It was reported that the main active components in the leaves of Morus nigra were 1-DNJ alkaloids, flavonoids and phenols. It has high nutritional value, antioxidant activity, hypoglycemic activity, glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism regulation, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and anticancer effects [

10].

Medicinal mulberry leaves in many pharmacopoeias use frost mulberry leaves (harvest after frost), especially after the first frost is better [

11]. It has been reported that temperature was one of the main factors affecting the growth of mulberry leaves and metabolite synthesis [

12]. Since the Ming and Qing dynasties, the picking of mulberry leaves mostly believed that autumn and winter would be better after the frost. The selection of mulberry leaves by frost was not initially proposed. Still, it was gradually proposed in the practitioner's practical discovery, and the frosted mulberry leaves were retained under the screening of time. In recent years, some researchers also found that the content of secondary metabolic components in mulberry leaves picked in different seasons was significantly affected by the environmental temperature [

13]. With the development of metabolomics and system biology in recent years, relevant researchers have begun to pay attention to the dynamic changes of metabolites in mulberry leaves before and after the frost. Zou et al. found significant differences in phenol content and antioxidant activity of mulberry leaves from different varieties and picking times in the south of China [

14]. Through metabolic pathway analysis and bioinformatics methods, Xu et al. speculated that lower temperatures would induce the expression of key enzyme genes in the flavonoid synthesis pathway and facilitate the accumulation of flavonoids [

15]. Li et al. determined that there was the difference in the content of alkaloid compounds in 711 mulberry varieties from 24 provinces in East China [

16]. Although there have been many studies on the metabolites of mulberry leaves under different times, locations, and temperatures, there is still a lack of systematic research on the dynamic changes of metabolites, especially DNJ compounds and flavonoids compounds in mulberry leaves before and after the frost.

To further study the effects of mulberry leaves before and after the first frost and harvest time on the dynamic changes of metabolites, especially DNJ compounds and flavonoids, the components of 100+ metabolites were selected as indicators to comprehensively reflect the dynamic changes of metabolites in mulberry leaves using plant metabolomics technology. The key metabolites mainly affected after first frost were screened based on the absolute quantitative analysis of metabolites. In conclusion, the study on dynamic changes of metabolites in mulberry leaves before and after the frost is of great significance for the in-depth understanding of the physiological and ecological characteristics of mulberry in cold environments, which can provide a theoretical basis and practical guidance for the growth and yield of mulberry. Suppose the time and method of picking mulberry leaves can be scientifically selected. In that case, the advantages of DNJ compounds and flavonoid compounds in mulberry leaves can be utilized to the maximum extent, and the medicinal value of mulberry leaves can be improved.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Detection of the overall metabolome of mulberry leaf and evaluation of data quality

To study the effect of mulberry leaf harvest on the material accumulation pattern on different days after frost, 138 samples collected on 23 harvest days from two different mulberry varieties of

Morus nigra L. and

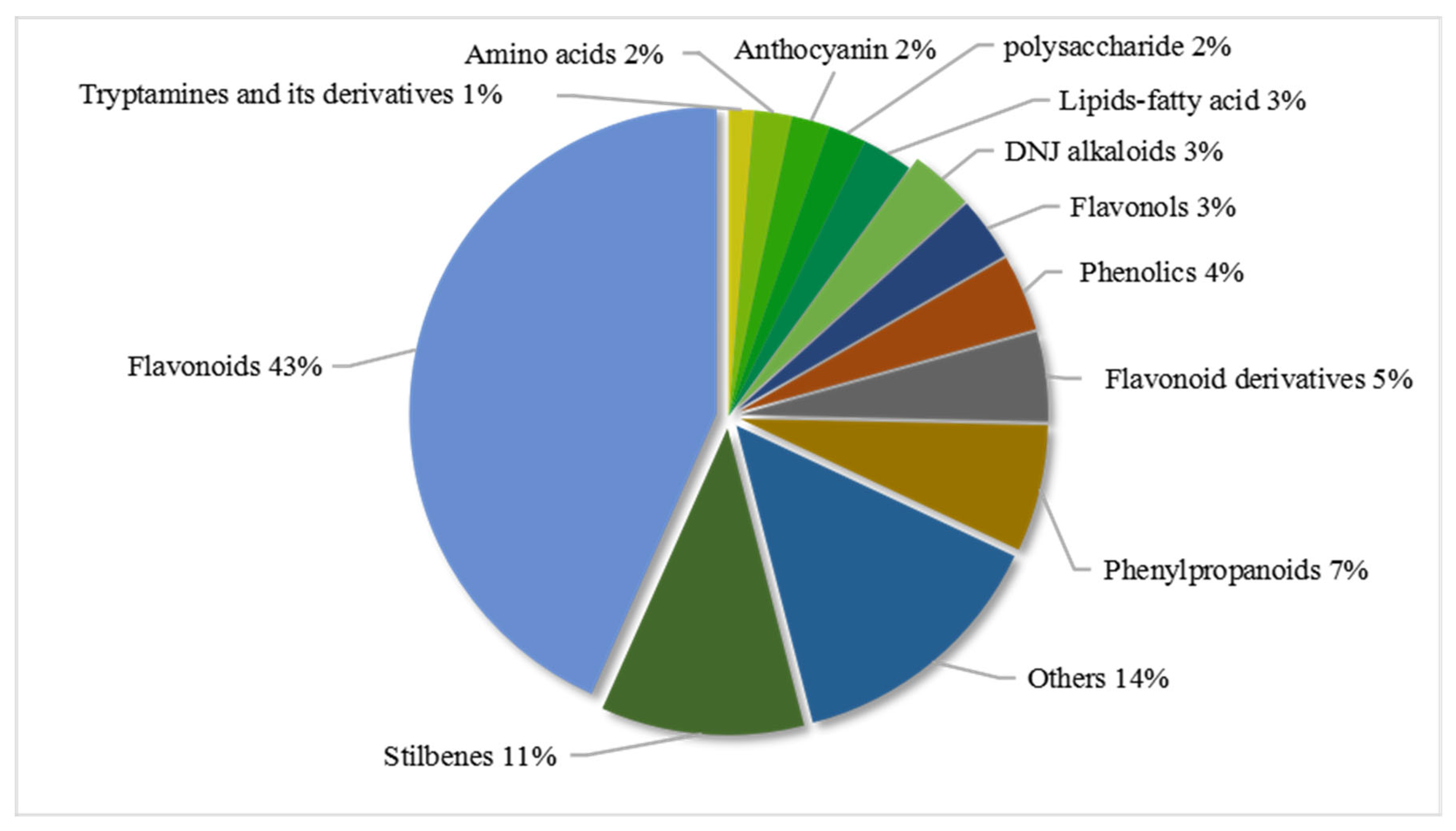

Morus alba L. were selected for metabonomic analysis. Through literature retrieval, standard comparison, public database matching and metabolite profiling, 150 different metabolites were identified, including 13 types of metabolites such as flavonoids, DNJ alkaloids, phenylpropane, lipids, anthocyanins, and amino acids (

Figure 1; Table S1).

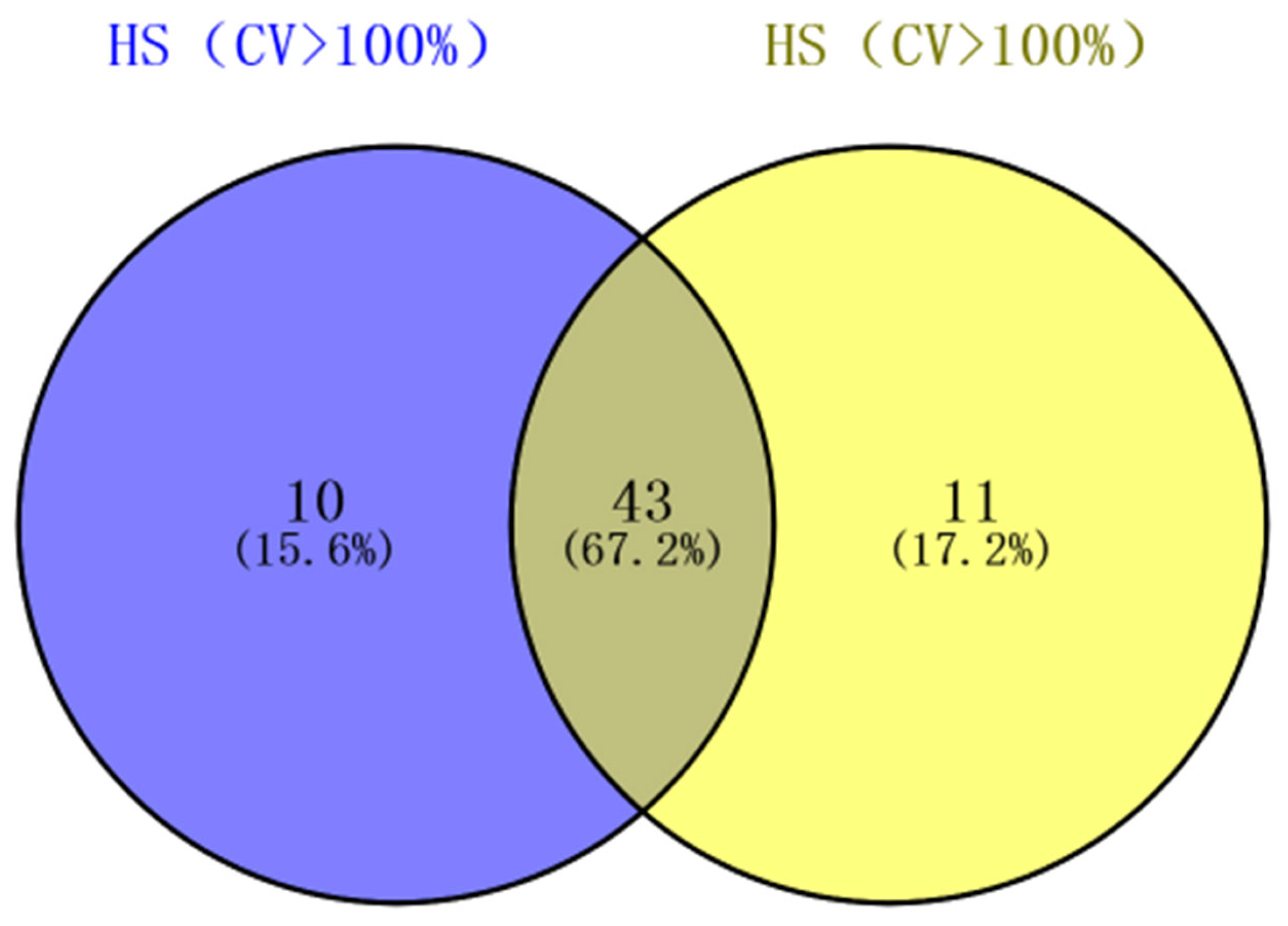

In order to master the overall metabolome data, statistical analysis was performed on the content of detected metabolites in 138 samples. The results showed that 64.0% of the metabolite coefficient of variation (CV) was over 50%, and the proportion of metabolites with CV value greater than 100% was 38.6% (Table 1), indicating that the metabolome data of mulberry leaves before and after first frost fluctuated greatly, providing a good data basis for subsequent analysis. For the Morus alba L. variety, the CV values of 35.5% and 36.0% metabolites at different growth stages were greater than 100%, respectively. Further analysis showed that 67.2% of the metabolites had CV values greater than 100% in both varieties, indicating that the affected metabolites of the two varieties were mostly similar in different growth and development stages, but there were metabolites that specifically responded to changes between varieties (

Figure 2).

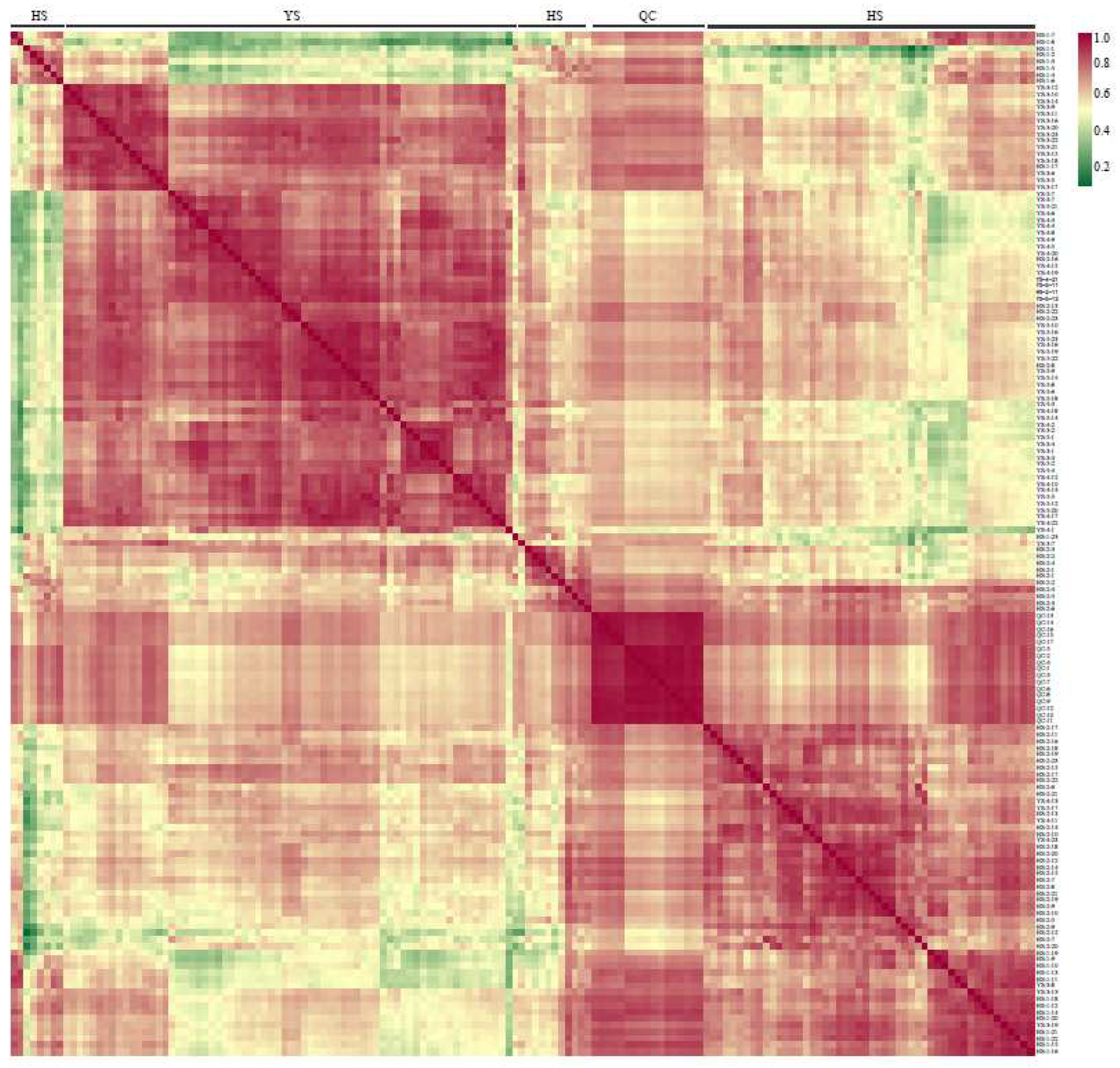

A total of 17 quality control (QC) samples were prepared. QC was prepared by uniformly mixing the extractive solutions of all samples to determine whether the conditions, such as instruments, were stable throughout the experiment. By analyzing the correlation between samples from the offline data of the metabolic group, we could determine the biological repeat effect of samples in the group. The higher the correlation coefficient, the higher the biological repeat in the group, and the more reliable the data would be. Pearson correlation coefficient (

r) was used to evaluate the correlation index of biological repeat samples. The statistical results showed that 17 QC groups were together, and

r was close to 1, indicating that the correlation between the samples in this experiment was strong. The data quality was good, which could be used for the subsequent analysis of differential metabolites (

Figure 3).

2.2. Analysis of differences in metabolic accumulation patterns of Morus nigra L. and Morus alba L.

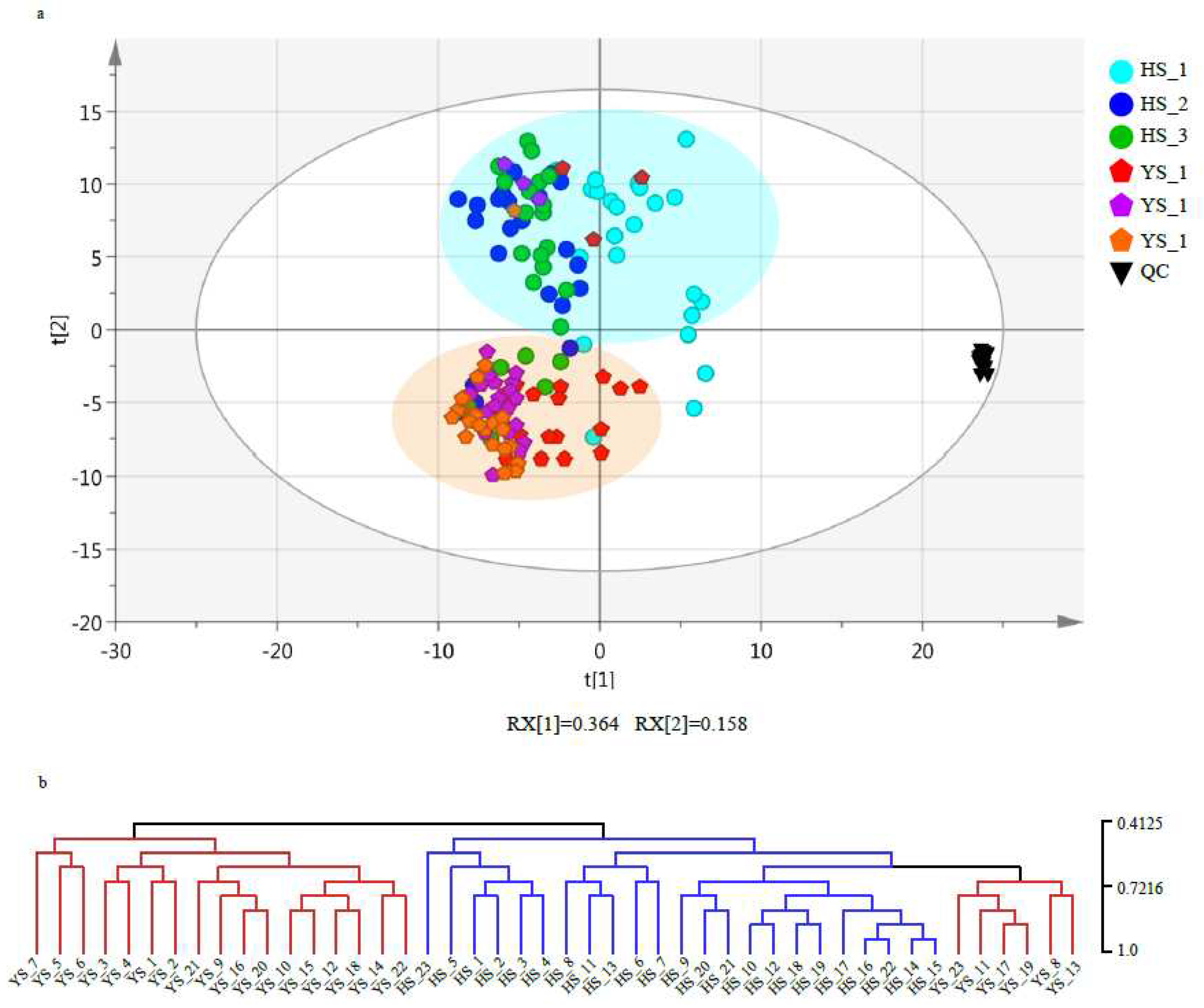

To understand the differences in metabolic accumulation patterns of two varieties of mulberry leaves, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on 138 tissues in this study. The results showed that the metabolic accumulation patterns of

Morus nigra L. and

Morus alba L. were significantly different, which were clustered into two groups (

Figure 4a). The first principal component mainly reflected the difference in metabolites between

Morus nigra L. and

Morus alba L. and explained 36.4% change in metabolites in the whole data set ( 4A). The tree diagram of clustering analysis was also consistent with that of PCA, with 138 tissues divided into two main branches (

Figure 4b). However, the metabolite accumulation patterns of tissues collected in the morning and evening of the frosting day of

Morus nigra L. (YS_11, YS_13, YS_17, and YS_19) were significantly different from those collected at other times, suggesting that the metabolite accumulation pattern had markedly changed on the frosting day of

Morus nigra L. Moreover, the leaf collection times on the frosting day (morning: YS_11 and YS_17, noon: YS_12 and YS_18, and evening: YS_13 and YS_19) had effects on the metabolite accumulation pattern.

2.3. Dynamic changes of metabolite contents before and after the frost of Morus nigra L. and Morus alba L.

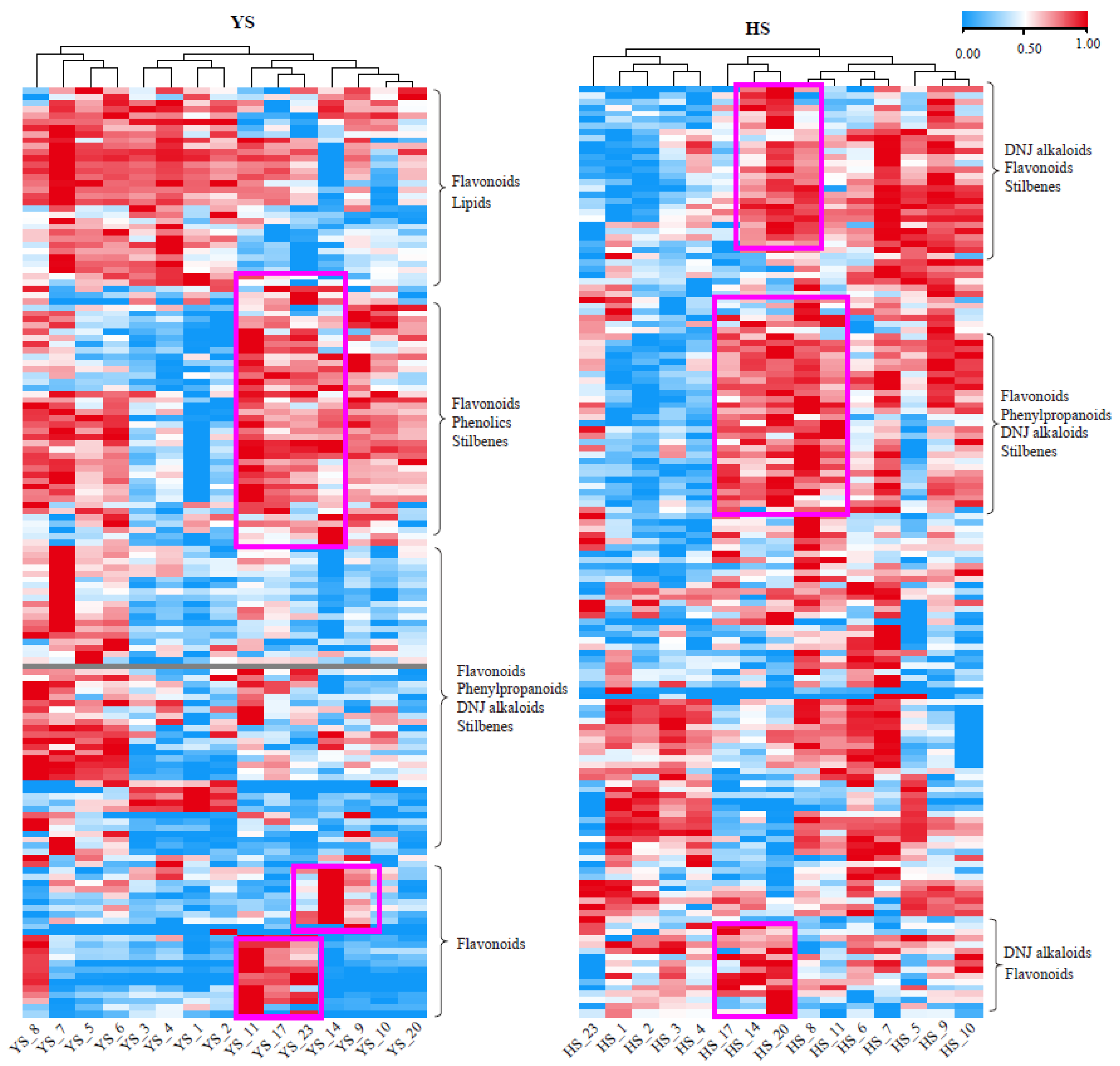

Based on the 150 metabolites present in the leaf tissues collected at different times, the analysis results showed that there existed significant differences in the content changes of metabolites of

Morus nigra L. and

Morus alba L. after undergoing the frost. After the frost of

Morus nigra L., some flavonoids and stilbenes were significantly enriched, while the contents of some flavonoids and most DNJ alkaloids were decreased considerably. After passing through the first frost, DNJ alkaloids, flavonoids and stilbenes were enriched significantly in

Morus alba L. Some flavonoid substances had the highest content before frost and began to be gradually reduced (

Figure 5).

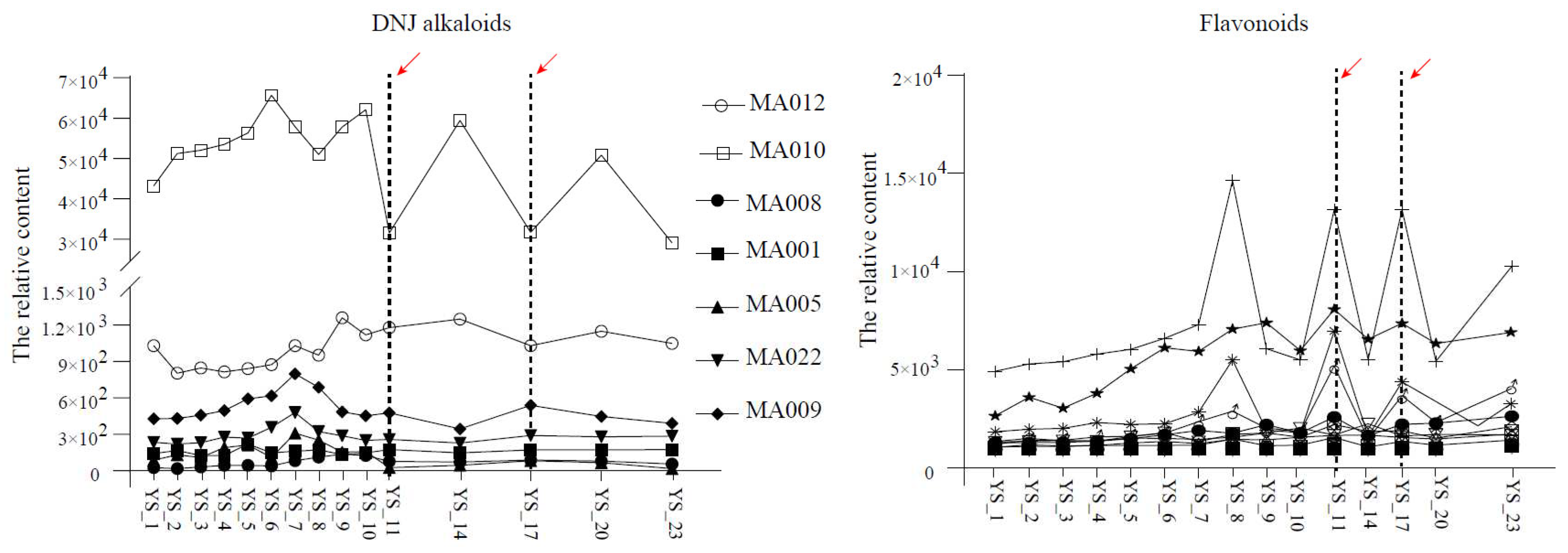

To observe the dynamic changes of some key metabolites more intuitively, we selected some metabolites with the most prominent fluctuation (CV>100%) after frost for analysis. The results showed that the content of DNJ alkaloids in

Morus nigra L. before the frost was significantly higher than that after the frost. In addition, significant decreases in some DNJ alkaloids (1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino 4-imino-D-arabinitol and 4-Benzyl-1,4-dihydro-3-oxo-3H-pyrro [2,1-c] [

1,

4] oxazine-6-carboxaldehyde) were observed on the first and second frosting days (YS_11 and YS_17). At the same time, we found that some flavonoids (kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside, Sanggenon T, 7,2'-DiHydroxy-4'-Methoxy-8-Prenylflavan, 2', 4', 7-Tri Hydroxy-8-(2-Hydroxyl) Flavan 7-Me) sharply increased on the same day of the two frostings, and these flavonoid contents were significantly higher after the frosting than before (

Figure 6). Therefore, we speculated that there was an opposite relationship between the dynamic changes of DNJ compounds and some flavonoid substances in

Morus nigra L. The results of correlation analysis also showed that DNJ alkaloids had a significant negative correlation with some flavonoids (

Table 1).

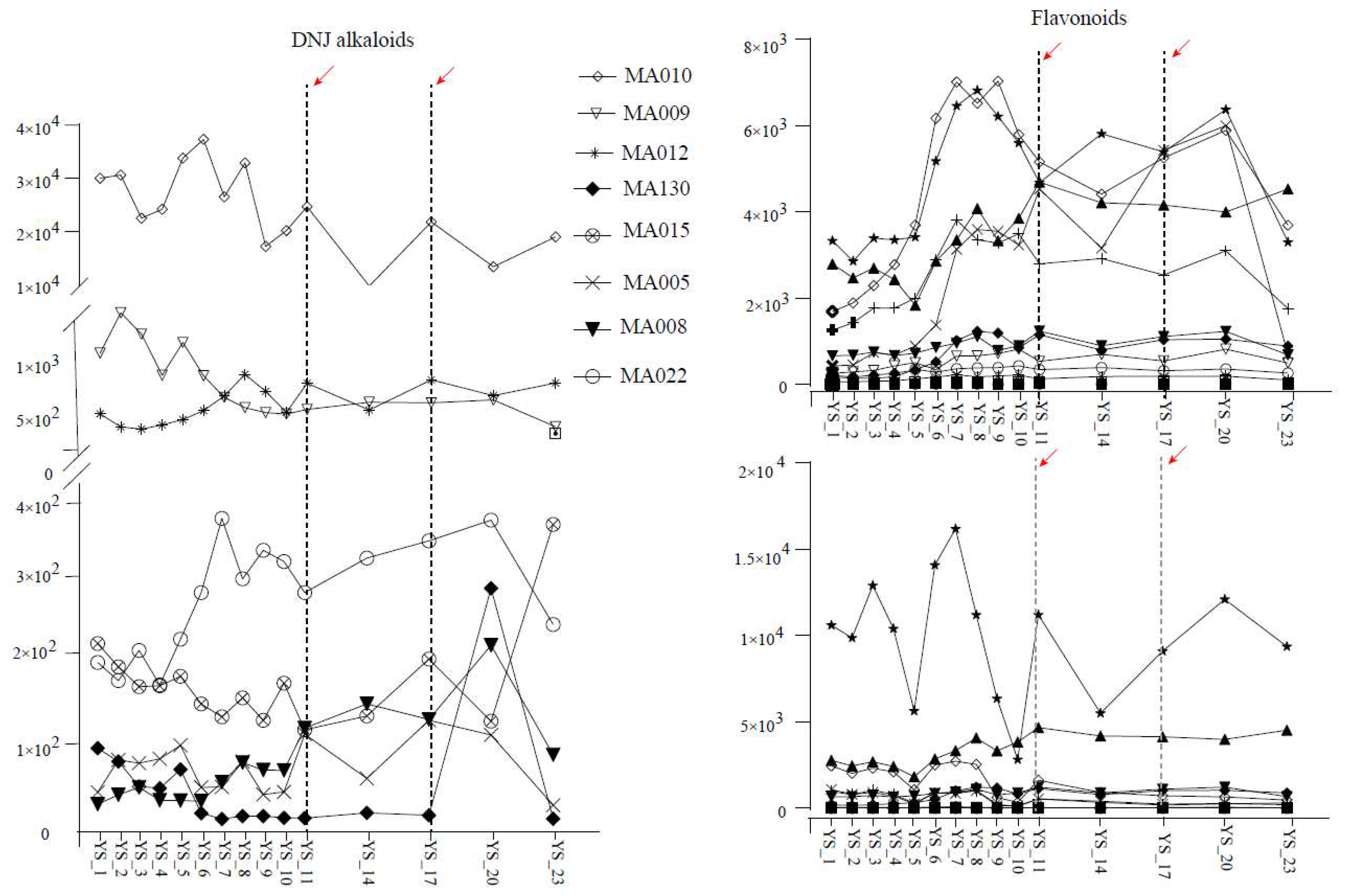

The dynamic changes of DNJ alkaloids in

Morus alba L. were different from that in

Morus nigra L. The contents of most DNJ alkaloids significantly increased after the frost, and they continuously increased after the first frost, peaked after the second first frost, and then declined sharply. The dynamic change rule of flavonoid was also slightly different from that of

Morus nigra L., mainly that the content increased sharply one week before the first frost, decreased significantly by the first frost, and then increased again until the first frost content reached the peak again at the second time (

Figure 7).

DNJ is considered to be the most effective anti-hyperglycemic compound in mulberry leaves [

17]. Studies have shown that the content of DNJ alkaloids shows a complex change trend in the growth and development of mulberry leaves [

18]. Our study also found that DNJ substances significantly change before and after the cream. Interestingly, the changes in DNJ content in medicinal mulberry leaves and black mulberry leaves showed opposite trends before and after frost treatment. In medicinal mulberry, the DNJ content showed an overall reducing trend after the frost. For black mulberry, DNJ content showed an increasing trend after the first frost and especially peaked one day after the second first frost. In their previous studies, Kim et al. also found significant differences in the genetic background of mulberry trees from different varieties, as well as differences in alkaloid content and change trends [

19]. Therefore, we speculated that the content change trend of DNJ compounds after frost treatment was not only possibly affected by the physiological state of mulberry leaf growth and development and environmental factors but also related to the different enrichment responses of DNJ compounds in mulberry leaves of different varieties before and after frost treatment.

Flavonoids, another essential active substance in mulberry leaves, have the effects of anti-bacteria, anti-inflammation, lipid-lowering, glucose-lowering, and anti-oxidation. They have become the hot spots in the research on the physiological activity of mulberry leaves as a drug in recent years [

20]. Yu determined that low temperature after the frost could induce

UFGT gene expression in mulberry leaves, accumulating many flavonoid glycosides in mulberry leaves [

11]. Combined metabolomics and transcriptomics analyses by Xu showed that many flavonoids were significantly enriched in mulberry leaves under cold stress [

21]. This study's results were consistent with the above studies' conclusions. The flavonoids were increased in black and medicinal mulberry leaves after passing through the first frost, and the content peaked in the second frost.

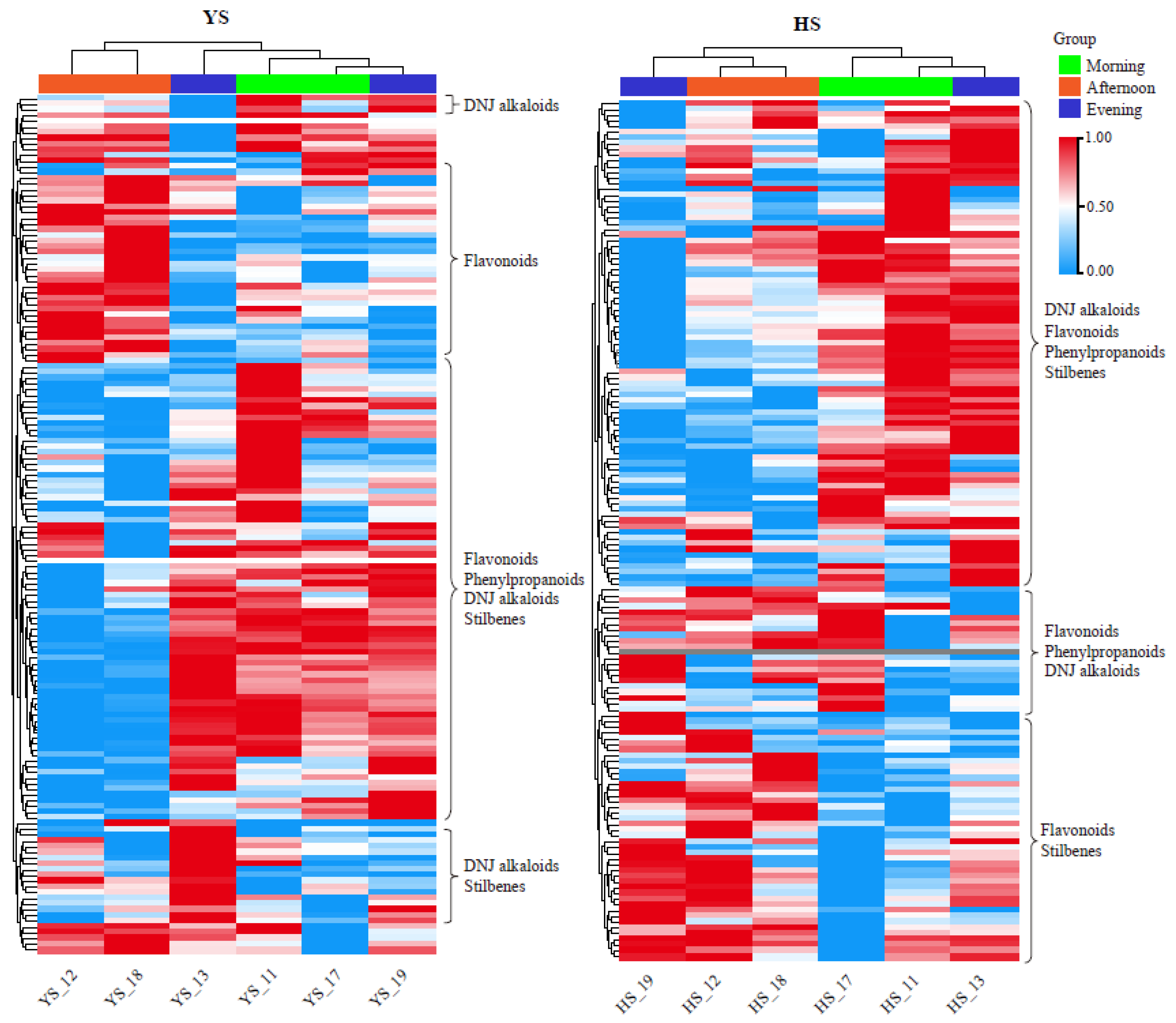

2.4. Metabolite content in mulberry leaves affected by the day-night cycle

To further explore the effect of circadian rhythm on the contents of metabolites in mulberry leaves, we collected the leaf tissues of

Morus nigra L. and

Morus alba L. in the morning (9:00 a.m.) and in the afternoon (4:00 p.m.). The evening (11:00 p.m.) and analyzed the results of metabolite detection during the two frostings. As shown in

Figure 8, the overall accumulation patterns of

Morus nigra L. and

Morus alba L. were the same, and the clearest rule was that there were significant differences in metabolite accumulation patterns between leaves collected in the afternoon and in the morning or at night. In

Morus nigra L., except for a small number of leaves collected at noon with high flavonoid content, most other substances, including DNJ alkaloids, flavonoids, phenylpropane, and stilbenes, were significantly lower than those in the morning and evening, and the similar situation was found in

Morus alba L. (

Figure 8).

Mari found that the content of flavonols in mulberry leaves had a positive correlation with the total hours of solar radiation on the picking day but a negative correlation with the temperature. The seasonal variation of DNJ content was also closely related to temperature [

22]. Guo measured that the flavonoid content in mulberry leaves was greatly affected by the leaf age (tip, tender and old leaves) and seasonal changes [23]. Our study also showed that different picking times on the picking date could significantly affect the metabolite content in mulberry leaves. We analyzed the effect of circadian rhythm on metabolite accumulation in two varieties of mulberry leaves. We concluded that harvesting mulberry leaves in the morning would obtain higher contents of DNJ alkaloids, flavonoids and other substances.

The above studies have shown that the dynamic changes of metabolites in mulberry leaves after frost are very significant, which has an important reference value for the rational use of active substances in mulberry leaves. In addition, the changing rules of metabolites in mulberry leaves before and after the frost was explored in depth. The results not only help to understand the growth and development law of mulberry leaves but also provide essential theoretical support and guidance for the development and utilization of mulberry leaves.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Medicinal mulberry (

Morus nigra L.) and black mulberry (

Morus alba L.) were collected from Jiamu Fruit Science's national long-term scientific research base, Xinjiang. Mulberry leaves were sampled from September 19, 2021, once every 7 d. When an early warning of the frost appeared, the sampling strategy was changed: Samples were collected every three days for 15 d before and every day for 3 d before the frost. Samples were collected once in the morning (9 a.m.), once in the afternoon (4 p.m.), and once in the evening (11 p.m.) on the day of the frosting. After the frost, the samples were collected daily for continuous 3 d. Then every 7 d, Continuous sampling was conducted 3 d before the second frost, consistent with the first frost sampling measure. Unless otherwise specified, the sampling time was 9: 00 a.m. (

Table 2). During sampling, three leaves (the 3rd-6th leaf from the top down of the branch) were collected from each tree, mixed and regarded as a biological repeat. The leaves were immediately put into liquid nitrogen and transferred to -80°C after 1 h. A total of five trees were collected. The samples from each tree were stored separately. Three biological repetitions were subsequently selected for metabolite detection.

3.2. Experimental methods

3.2.1. Preparation and extraction of sample

After grinding the mulberry leaf samples with the grinder (MM400, Retsch), 100 mg powder was weighed, and 1 mL 70% methanol-0.5% formic acid water was added. The powder was extracted by ultrasonic instrument (KQ-300DE, Kunshan, China) for 10 min, then by low-temperature high-speed centrifuge (MULTIFUGEXIR, after centrifugation for 5 min at 10000 r/min, 200 μL of supernatant was absorbed into a 2 mL volumetric bottle. The chromatographic solution was filled to the scale with methanol and mixed through a 0.22 μm microporous filter membrane. The filtrate samples were stored in the sample bottle.

3.2.2. Chromatographic and mass spectrometry conditions

ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (100 mm×2.1 mm, 1.7 μm) was used for UPLC analysis (I-Class, Waters, USA). The column and autosampler temperatures were set at 45°C and 10°C, respectively. The mobile phase A consisted of methanol, and phase B consisted of a 0.1% formic acid aqueous solution (v/v). Gradient elution was performed at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min, and an injection volume of 2 μL:0 to 3 min is 5-40% A, 3 to 10 min is 40 to 95% A, 10 to 12 min is 95% A, 12 to 13 min is 95 to 5% A, 13 to 15 min is 5% A.

The sample quality spectrometric analysis was performed on a QTOF mass spectrometer (I-Class XEVO G2-XS, Watersey, USA) with an electrospray ion source (ESI) molecular weight scanning range of m/z 100-1200. The optimized parameters are as follows: the capillary voltage in positive ion mode and negative ion mode is 3.00 kV and 2.50 kV, the source temperature and dissolvent temperature are 120°C and 450°C, the flow rate of cone-hole and dissolvent gas is 50 L/h and 800 L/h, and the cone-hole voltage is 40 V.

In MSE mode, the low energy scan is not set, and the energy for high energy scan is 15 eV-40 eV. For quality accuracy and reproducibility, sodium formate was used as a calibration solution. In addition, real-time mass number correction was performed using leucine enkephalin (LE) (M/Z 556.2771 in positive ion mode; M/Z 554.2615) in negative ion mode.

4. Conclusions

The results of metabonomics analysis in different leaf tissues of Morus nigra L. and Morus alba L. before and after the frost showed that the accumulation patterns of metabolites in leaves of Morus nigra L. and Morus alba L. were significantly different before and after the frost, indicating that the types and contents of metabolites in the two varieties were quite different, which represented that the applications of the two varieties might be various. In addition, the primary differential metabolites in the two varieties before and after the frost were analyzed, and it was found that the DNJ content in Morus nigra L. showed an overall reducing trend after the frost. The flavonoids reached their peak during the second frost. For Morus alba L., DNJ increased after the first frost and peaked one day after the second first frost. Flavonoids peak mainly the week before the frost and again the day after the second frost. It could be seen that frost had a more significant effect on Morus nigra L. In actual application, we should select the appropriate time to harvest the mulberry leaves according to the target metabolites. Finally, by analyzing the effect of circadian rhythm on metabolite accumulation in two varieties of mulberry leaves, it was concluded that harvesting mulberry leaves in the morning would obtain higher contents of DNJ alkaloids, flavonoids and other substances.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W.; methodology, L.Y.; J.Z. and S.F.; software, L.Y. and J.L.; validation, L.Y. and Y.C.; formal analysis, L.Y. and J.Z.; investigation, L.Y.; resources, L.Y.; data curation, L.Y.; J.Z. and S.F.; writing-original draft preparation, L.Y. ; writing-review and editing, L.Y.; J.Z. and Y.W.; visualization, L.Y.; supervision, Y.W.; project administration, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Application for Open Project of Key Laboratory of Xinjiang Autonomous Region (Analysis of Genetic Variation in Morus nigra L. and Research on Key Genes of 1-DNJ Alkaloid Synthesis), and Innovation project of germplasm resources of main forest and fruit tree species (lgxy202108) .

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chang, Jer-Chia.; Yi-Hsuan, Hsu. Mulberry. Temperate Fruits; Apple Academic Press, 2021; pp. 491–535. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtiyarullaevich, U. F.; Norqobilovich, M. A.; Kamaraddinovich, K. S. Agrotechnics of cultivation and use of mulberry seedlings for picturesque landscaping of highways. Galaxy International Interdisciplinary Research J. 2023, 11, 363–370. [Google Scholar]

- Gundogdu, M.; Muradoglu, F.; Sensoy, R.G.; Yilmaz, H.J.S.H. Determination of fruit chemical properties of Morus nigra L.; Morus alba L. and Morus rubra L. by HPLC. Sci. hortic. 2011, 132, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.; Duke, J.A. A Field Guide to Medicinal Plants: Eastern and Central North America. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. 1990.

- Munir, A.; Khera, R.A.; Rehman, R.; Nisar, S. Multipurpose white mulberry: A review. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2018, 13, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Adachi, K. Analytical insights for silk science and technology. Anal. Sci. 2023, 29, 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, S.; Liu, B.; Liu, F.; Xu, Y. Mulberry leaf (Morus alba L.): A review of its potential influences in mechanisms of action on metabolic diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 175, 106029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Dai, H.; An, Y.; Cheng, L.; Shi, L.; Lv, Y.; Zhao, B. Mulberry leaf flavonoids inhibit liver inflammation in type 2 diabetes rats by regulating TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Nie, W.J. Chemical properties in fruits of mulberry species from the Xinjiang province of China. Food Chem. 2015, 174, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.; Chai, X.; Hou, G.; Zhao, F.; Meng, Q. Phytochemistry, bioactivities and future prospects of mulberry leaves: A review. Food Chem. 2022, 372, 131335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Fan, J.; Wang, D.; Gong, X,Ouyang, Z. Accumulation of flavonoid glycosides and UFGT gene expression in mulberry leaves (Morus alba L.) before and after frost. Chem & Biodivers. 2017, 14, 1600496. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D. Q.; Cheng, S. Y.; Zhang, J. Q.; Lin, H. F.; Chen, Y. Y.; Yue, S. J. Zhao, Y. C. Morus alba L. Leaves-Integration of Their Transcriptome and Metabolomics Dataset: Investigating Potential Genes Involved in Flavonoid Biosynthesis at Different Harvest Times. Front. Plant. Sci 2021, 2452. [Google Scholar]

- Dalmagro, A. P.; Camargo, A.; da Silva Filho, H. H.; Valcanaia, M. M.; de Jesus, P. C.; Zeni, A. L.B. Seasonal variation in the antioxidant phytocompounds production from the Morus nigra leaves. Ind. Crops and Prod. 2018, 123, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Liao, S.; Shen, W.; Liu, F.; Tang, C.; Chen, C. Y. O.; Sun, Y. Phenolics and antioxidant activity of mulberry leaves depend on cultivar and harvest month in Southern China. Int. J. mol. sci. 2012, 13, 16544–16553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D. Q.; Cheng, S. Y.; Zhang, J. Q.; Lin, H. F.; Chen, Y. Y.; Yue, S. J. Zhao, Y. C. Morus alba L. Leaves–Integration of Their Transcriptome and Metabolomics Dataset: Investigating Potential Genes Involved in Flavonoid Biosynthesis at Different Harvest Times. Front. Plant. Sci 2021, 2452. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D. Y.; Wan, Y.; Hao, J. Y.; Hu, R. Z.; Chen, C.; Yao, X. H.; Li, L. Evaluation of the alkaloid, polyphenols, and antioxidant contents of various mulberry cultivars from different planting areas in eastern China. Ind. Crops and Prod. 2018, 122, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.Q.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, J.G.; Deng, W.; Wang, H. L.; Wei, Z.J. Quantitative determination of 1-deoxynojirimycin in mulberry leaves from 132 varieties. Ind. Crops and Prod. 2013, 49, 782–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, L.; Saviane, A.; Montà, A. D.; Paglia, G.; Pellati, F.; Benvenuti, S.; Cappellozza, S. Determination of 1-deoxynojirimycin (1-dnj) in leaves of italian or italy-adapted cultivars of mulberry (Morus sp. pl.) by hplc-ms. Plants. 2021, 10, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.; Kim, J. W.; Lee, H. S.; Ha, N. K.; Ryu, K. S. Regional and varietal variation of 1-deoxynojirimycin (DNJ) content in the mulberry leaves. Int. J. Ind. Entom. 2001, 2, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Chen, G.; Ma, B.; Zhong, C.; He, N. Metabolic profiling and transcriptome analysis of mulberry leaves provide insights into flavonoid biosynthesis. J. Agr. food chem. 2020, 68, 1494–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiyama, M.; Katsube, T.; Koyama, A.; Itamura, H. Seasonal changes in functional component contents in mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaves. Horticult. J. 2017, 86, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Lai, J.; Wu, Y.; Fang, S.; Liang, X. Investigation on Antioxidant Activity and Different Metabolites of Mulberry (Morus spp.) Leaves Depending on the Harvest Months by UPLC–Q-TOF-MS with Multivariate Tools. Molecules, 2023, 28, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).