1. Introduction

There is a growing trend of fungal infections affecting immuno- and medically compromised patients (1,2). The treatment of invasive fungal infections (IFIs), including invasive aspergillosis (IA), has remained challenging due to several factors, namely the limitations in currently available antifungal therapies and changing epidemiology (3,4). A. terreus is the third or fourth most common etiological agent of IA, depending on the geographical region (5). This species has a unique clinical position among the opportunistic pathogenic Aspergillus species due to the relatively high mortality rate and reduced susceptibility to amphotericin B (AmB), making treatment challenging (6–9). Currently, voriconazole remains the first therapeutic choice for aspergillosis, followed by other substituted agents, such as isavuconazole (ISA), liposomal AmB (L-AmB), and voriconazole (VRC) plus an echinocandin (10). In addition to the limited therapeutic options available, azole-resistant A. terreus and related species, along with the tolerance phenomenon, threaten the current pipeline of antifungals (11–14).

New generations of antifungals are needed to combat the rapidly rising levels of resistance and their associated clinical failures (15). The development of antifungal drugs has stagnated in the past two decades, with only ISA introduced (16). Although ISA has a broader spectrum than VRC and fewer drug-related side effects, it still displays cross-resistance with other azoles (17). Even though antifungal drug development is a lengthy process, it addresses the consequences of limited drug classes. Several antifungals are currently being developed in clinical trials and have substantial support from pharmaceutical companies (18).

In the present study, the in vitro activity of some promising new drugs in development was analyzed, including ibrexafungerp, manogepix, olorofim, and rezafungin. Manogepix (formerly E1210) is the active component of fosmanogepix, a novel first-in-class broad-spectrum antifungal agent that inhibits the activity of Gwt1 enzyme, which is involved in the biosynthesis of glycosylphosphatidylinositol(GPI) anchors, an essential component of the fungal cell wall (19,20). This leads to defects in various steps of cell wall biosynthesis with accompanying inhibition of cell wall growth, hyphal elongation, and attachment of fungal cells to biological substrates (20). Manogepix has been shown to have broad-spectrum activity against various molds and yeasts (19). Ibrexafungerp (formerly SCY-078), a semisynthetic derivative of enfumafungin, is a potent inhibitor of fungal β-(1,3)-D-glucan synthases (21), with promising activity against Aspergillus and Candida species. Olorofim (formerly F901318), a new antifungal agent with a novel selective activity, inhibits fungal dihydroorotate dehydrogenase(DHODH), thus halting de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis and, ultimately DNA synthesis, cell growth, and division (22,23). The cyclic hexapeptide rezafungin (formerly CD101), which is structurally similar to anidulafungin, is an echinocandin highly active against Aspergillus (22). The current study aimed to evaluate the in vitro activity of the above-mentioned new antifungals against a collection of Aspergillus section Terrei isolates, including AmB wildtype/non-wildtype and azole-susceptible/-resistant A. terreus sensu stricto (s.s.) and related species, using the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) reference method.

2. Materials and Methods

A total of 100 molecular identified

Aspergillus section

Terrei isolates, including

A. terreus s.s. (n = 30),

A. citrinoterreus (n = 9),

A. alabamensis (n = 7),

A. hortae (syn.

A. hortai; n = 6),

A. carneus (n = 6),

A. niveus (n = 6),

A. aureoterreus (n = 5),

A. neoindicus (n = 5),

A. iranicus (n = 5),

A. neoafricanus (n = 4),

A. pseudoterreus (n = 4),

A. allahabadi (n = 4),

A. floccosus (n = 2),

A. barbosae (n = 2),

A. bicephalus (n = 1),

A. ambiguus (n = 1), and

A. microcysticus (n = 1) were analyzed. The isolate collection included strains previously obtained and included in the ISHAM-ECMM-EFISG TerrNet Study (

www.isham.org/working-groups/aspergillus-terreus) (24) and those preserved in the CBS biobank housed at the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, the Netherlands. Strains were identified, as previously described (13,25). A selection of non-wildtype/wildtype and resistant/susceptible isolates was made based on the susceptibility profiles of tested conventional antifungals (AmB, ISA, VRC, posaconazole (PSC)) (data not shown) (

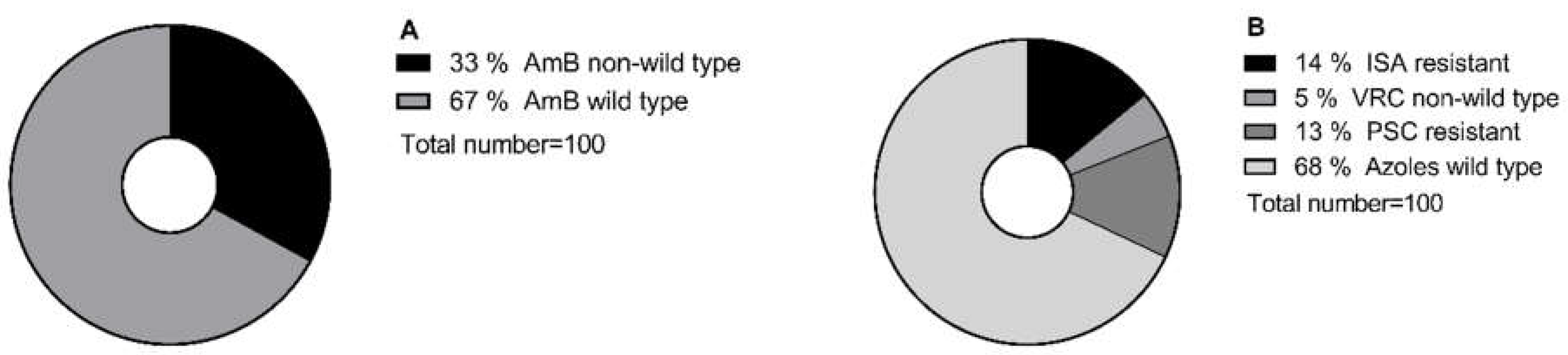

Figure 1). In total, 10% of selected isolates showed cross-resistance to the tested conventional antifungals.

Isolates were cultured from 10% glycerol frozen stocks (-80°C) on malt extract agar (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) at 37°C for up to 5 days; spores were harvested by applying spore suspension buffer (0.9% NaCl, 0.01% Tween 20 [Sigma-P1379]). Antifungal susceptibility testing was performed according to the broth microdilution method of EUCAST (26). The antifungals used were ibrexafungerp (range 0.03–16 mg/L; Scynexis, Inc., Jersey City, NJ, USA), olorofim (range 0.008–4 mg/L; F2G Ltd., Manchester, UK), rezafungin (range 0.01–8 mg/L; MedChemExpress, Sollentuna, Sweden), and manogepix (range 0.03–16 mg/L; MedChemExpress, Sollentuna, Sweden). The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs), the concentration at which no hyphal growth was detected, was assessed for olorofim, and for the rest of the tested agents, the minimal effective concentrations (MECs), which markedly altered hyphal growth with blunted colonies, was assessed. A final reading of MIC results was performed with a stereoscope after 48 h. Geometric mean (GM), MIC50/MEC50 (MIC/MEC causing inhibition of 50% of the isolates tested) and MIC90/MEC90 (MIC/MEC causing inhibition of 90% of the isolates tested) were calculated.

3. Results

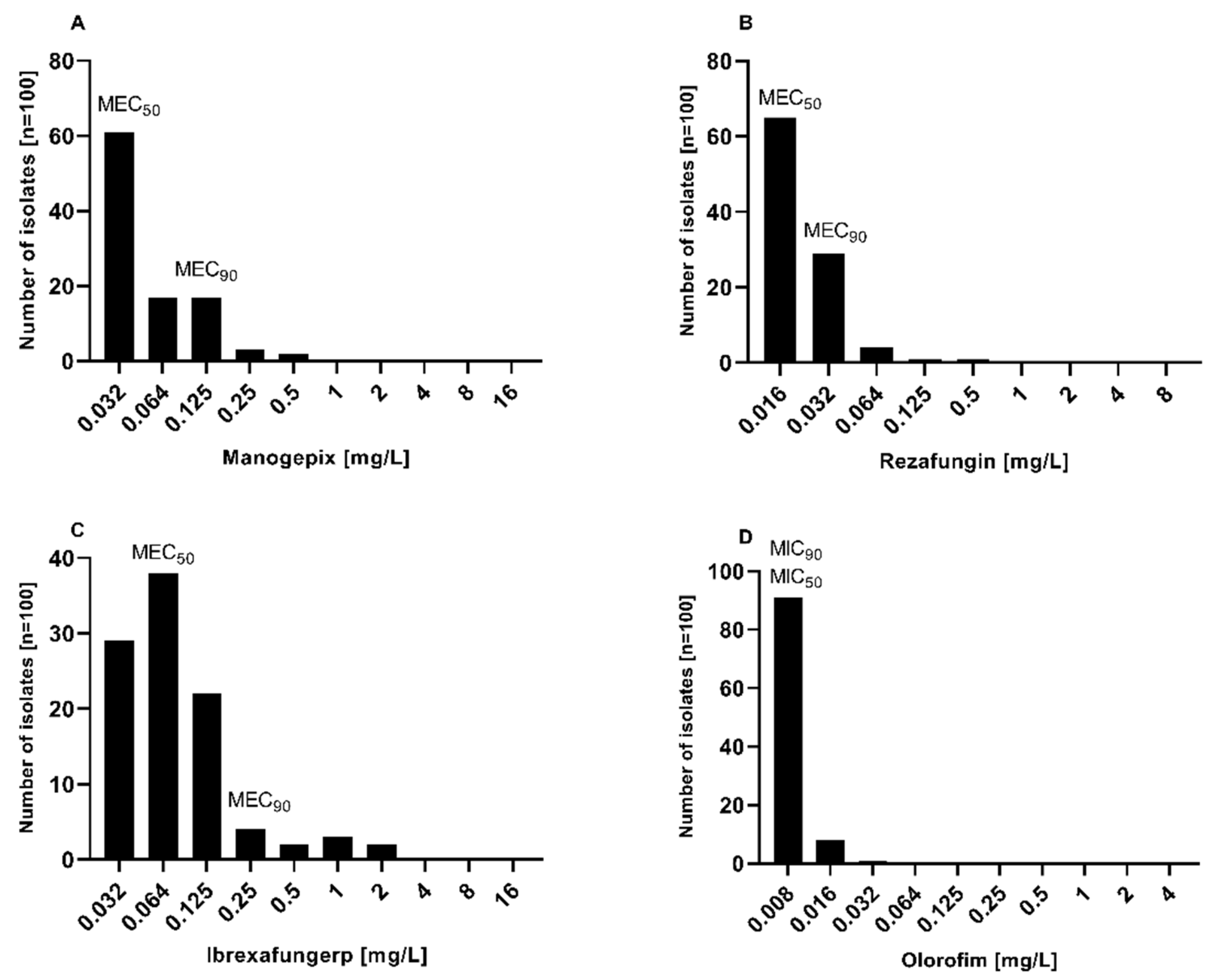

The MIC distribution and

in vitro susceptibility testing results of manogepix, rezafungin, ibrexafungerp, and olorofim against 100

Aspergillus section

Terrei isolates, including those with reduced susceptibility to AmB and resistance to azoles, are shown in

Figure 2,

Figure 3, and

Table 1.

Manogepix demonstrated potent

in vitro activity against all tested isolates, as shown in

Figure 1, with MECs ranging from 0.032 to 0.5 mg/L, and the MEC

50 and MEC

90 values of 0.032 and 0.125 mg/L, respectively. Considering the species separately (

Table 1),

A. citrinoterreus and

A. bicephalus demonstrated the highest MECs range (0.032-0.5 and 0.5 mg/L, respectively), and

A. carneus and

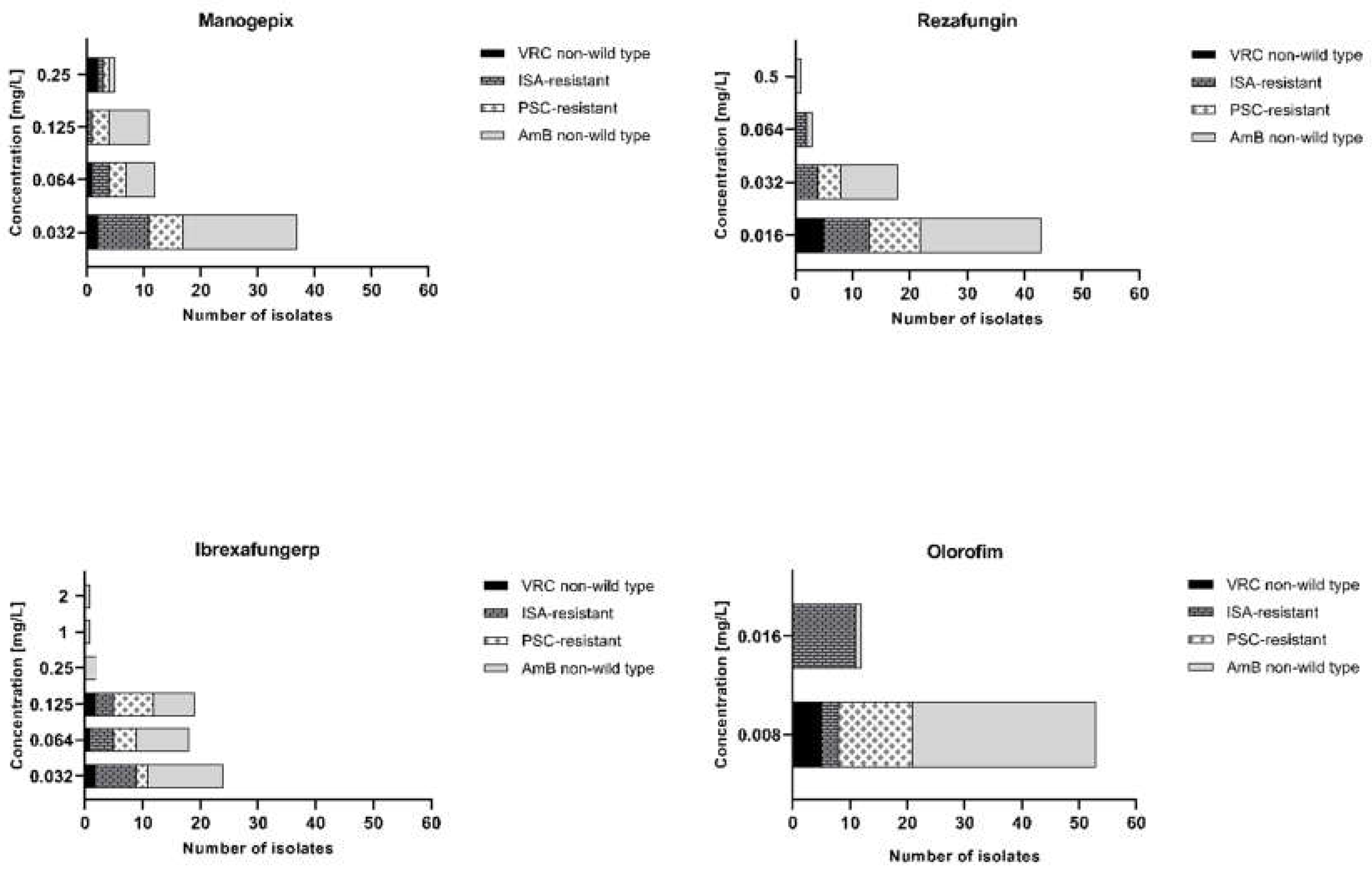

A. niveus the highest GM (both 0.086 mg/L). Furthermore, manogepix displayed potential activity at the lowest concentration (0.032 mg/L) against the majority of resistant/non-wildtype isolates (

Figure 3A). The MEC range, MEC

50, and MEC

90 values of rezafungin were 0.016 to 0.5 mg/L, 0.016 mg/L, and 0.5 mg/L, respectively, against all tested

Aspergillus. Among all tested species,

A. carneus showed the highest MEC range and GM for rezafungin (0.016-0.5 and 0.026 mg/L, respectively). Rezafungin inhibited most isolates at the lowest concentration, 0.016 mg/L, when focusing on resistant/non-wildtype isolates (

Figure 3B). Ibrexafungerp yielded MEC range, MEC

50, and MEC

90 values of 0.03 to 2 mg/L, 0.06 mg/L, and 0.25 mg/L, respectively. As compared to all other tested species,

A. citrinoterreus, and

A. terreus s.s, the most clinically isolated species, displayed the highest MEC range (both 0.032-2 mg/L), and

A. allahabadi showed the highest GM (0.087 mg/L). According to the results, ibrexafungerp exhibited promising inhibitory activity at the lowest concentration range tested (0.032-0.06 mg/L) against most of the non-wildtype and resistant isolates (

Figure 3C). Olorofim showed a high activity against all tested

Aspergillus section

Terrei isolates, exhibiting an MIC range, MEC

50, and MEC

90 values of 0.008–0.032 mg/L, 0.008 mg/L, and 0.008 mg/L, respectively. Comparatively,

A. neoindicus had the highest MIC range for olorofim (0.008-0.032 mg/L), and

A. iranicus showed the highest GM (0.012 mg/L). Considering non-wildtype/resistant isolates separately, olorofim showed a significant inhibitory effect at the lowest concentration tested (0.008-0.016 mg/L) (

Figure 3D).

Overall, all agents demonstrated promising activity against tested isolates and considering GM of all species together, the lowest value was assigned to olorofim, followed by rezafungin, manogepix, and ibrexafungerp (0.008 mg/L, 0.020 mg/L, 0.048 mg/L, and 0.071 mg/L, respectively).

4. Discussion

The mortality rate of aspergillosis infections remains high despite the improved diagnosis, and prophylaxis (27). There are currently four major classes of antifungal agents used to treat systemic mycoses: polyenes, azoles, echinocandins, and flucytosine (28). The effectiveness of present antifungals has been affected by toxicity, drug–drug interactions, variable pharmacokinetics, and reduced bioavailability (28). The emergence of drug resistance has introduced further limitations (29). For IA, VRC is the first line of treatment; alternatives include ISA, L-AmB, and VRC plus an echinocandin (30). Resistance to azoles, the first-line treatment, has grown alarmingly in the last decade, posing a serious challenge to the effective management of aspergillosis (29,31). The identification of antifungal resistance has relied on susceptibility testing, identifying MICs to define the susceptibility or resistance. Several factors further complicate treatment and lead to poor outcomes, such as method dependency of the susceptibility testing results and consequently discrepancies between in vitro and in vivo outcomes, as well as tolerance and persistence phenomena, which are not detectable by reference susceptibility testing methods (14,32,33). Therefore, the reduction in the currently limited antifungal arsenal leads to patient management complications and higher mortality due to resistant isolates, which calls for new antifungal agents and therapeutic approaches (3). Since A. terreus is naturally less susceptible to AmB, azole resistance in this species is of particular concern, which could lead to a loss of two primary lines of treatment (7,13). Furthermore, some less common species in section Terrei, exhibit high azole MICs, which, if not identified before antifungal therapy, may cause clinical failure (32). Thus, in this study, novel antifungals were tested against nearly all currently accepted species in section Terrei, including isolates with reduced susceptibility to conventional antifungals.

Similarly to previous studies (34,35), manogepix exhibited encouraging activity against all tested

Aspergillus spp., including AmB non-wildtype and azole-resistant isolates. Manogepix inhibited all tested isolates at 0.5 mg/L (MEC

50, 0.032 mg/L; MEC

90, 0.125 mg/L) (

Figure 1A, 2A, and

Table 1). Despite the similar MEC

50 and MEC

90 of

A. terreus s.s. and

A. terreus non-s.s. when compared separately, all

A. terreus s.s. were inhibited at 0.125 mg/L, while all

A. terreus non-s.s. were suppressed at 0.5 mg/L. As we found, a study of clinical isolates from Spanish patients found manogepix effective against cryptic

Aspergillus species, including those resistant to PSC and AmB (36). Furthermore, according to a recent study,

in vivo combining manogepix and L-AmB showed a synergistic effect in reducing invasive pulmonary aspergillosis fungal burden and improving survival (37). Synergistic effects with L-AmB may have greater utility in cases where azole resistance is suspected.

Rezafungin demonstrated significant

in vitro activity against all tested isolates, by 0.5 mg/L (MEC

50, 0.016 mg/L; MEC

90, 0.032 mg/L) (

Figure 1B,

Figure 2B, and

Table 1). Rezafungin MECs were higher for

A. terreus non-s.s. than

A. terreus s.s., 0.5 mg/L (MEC

50, 0.016 mg/L; MEC

90, 0.032 mg/L) and 0.06 mg/L (MEC

50, 0.016 mg/L; MEC

90, 0.032 mg/L), respectively. The prolonged half-life of rezafungin

in vivo (38), along with its potent

in vitro activity against

Aspergillus spp. (39), suggest that it may be beneficial in treating patients with infections caused by azole-resistant

Aspergillus. However, it should be noted that monotherapy with an echinocandin is not currently recommended as a primary treatment for IA. To determine whether this potent

in vitro activity would accelerate with combination therapy, and whether it would translate into

in vivo efficacy against infections caused by resistant

Aspergillus isolates, additional studies are warranted.

In vitro, ibrexafungerp, the new beta-glucan synthase inhibitor, showed promising antifungal activity against tested

Aspergillus section

Terrei, by MEC of 2 mg/L (MEC

50, 0.06 mg/L; MEC

90, 0.25 mg/L) (

Figure 1C,

Figure 2C, and

Table 1). There were no significant differences between MECs of

A. terreus s.s. 2 mg/L (MEC

50, 0.064 mg/L; MEC

90, 0.125 mg/L) and

A. terreus non-s.s. 2 mg/L (MEC

50, 0.064 mg/L; MEC

90, 0.25 mg/L). Ibrexafungerp has previously been shown to have

in vitro and

in vivo activity against

Aspergillus species, including azole-resistant and caspofungin-resistant strains, which is consistent with this study (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) (40,41). Furthermore, the synergistic effect of ibrexafungerp in combination with ISA, VRC, and AmB was shown (42). These results are likely to increase the appeal of using ibrexafungerp in combination with other agents for infections that are difficult to treat.

The strong activity of olorofim has been confirmed against the tested

Aspergillus section

Terrei, including those species that showed reduced susceptibility to AmB and/or azoles (

Figure 2 D,

Figure 3D, and

Table 1). Olorofim had the lowest MICs by 0.032 mg/L (MEC50 and MEC90, both 0.008 mg/L), with no differences between

A. terreus s.s., and

A. terreus non-s.s. Beside the present study, other studies have also shown that olorofim is effective against azole-resistant

A. fumigatus in vitro and

in vivo in murine models of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (22). Additionally this new drug has shown activity against other common

Aspergillus species, including

A. terreus (43–45). Olorofim's activity has been retained against isolates showing resistance to azoles and/or AmB, and given its entirely different target to the azoles, cross-resistance would not be expected.

In conclusion, a set of novel antifungals (manogepix, rezafungin, ibrexafungerp, and olorofim) has been demonstrated to have promising and consistent in vitro activity against nearly all currently accepted species of Aspergillus section Terrei regardless of azole and AmB resistance. The development of novel agents could play a pivotal role in treating multi-resistant mold infections, including azole-resistant aspergillosis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.V.-S., C.L.-F., M.B., and J.H.; methodology, R.V.-S., C.L.-F.; data analysis and investigation, R.V.-S., C.L.-F., M.B., and J.H.; resources, C.L.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, R.V.-S.; writing-review and editing, C.L.-F., R.V.-S., M.B., and J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The present study was funded by MUI.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are given in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

SCY-078 was provided by the sponsor, Scynexis, Inc., Jersey City, NJ, USA. Olorofim was provided by F2G Ltd. (Manchester, UK). The authors would thank Sonja Jähnig for technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. MB is an employee and shareholder of F2G Ltd.

References

- Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NAR, Levitz SM, Netea MG, White TC. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(165):165rv13. [CrossRef]

- Gow NAR, Netea MG. Medical mycology and fungal immunology: new research perspectives addressing a major world health challenge. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2016;371(1709):20150462. [CrossRef]

- Perfect JR. The antifungal pipeline: a reality check. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(9):603–16. [CrossRef]

- Lass-Flörl C, Cuenca-Estrella M. Changes in the epidemiological landscape of invasive mould infections and disease. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(suppl_1):i5–11. [CrossRef]

- Neal CO, Richardson AO, Hurst SF, Tortorano AM, Viviani MA, Stevens DA, et al. Global population structure of Aspergillus terreus inferred by ISSR typing reveals geographical subclustering. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:203. [CrossRef]

- Lass-Flörl C. Treatment of Infections Due to Aspergillus terreus Species Complex. J Fungi. 2018;4(3):83. [CrossRef]

- Vahedi Shahandashti R, Lass-Flörl C. Antifungal resistance in Aspergillus terreus: A current scenario. Fungal Genet Biol. 2019;131:103247. [CrossRef]

- Hachem R, Gomes MZR, El Helou G, El Zakhem A, Kassis C, Ramos E, et al. Invasive aspergillosis caused by Aspergillus terreus: an emerging opportunistic infection with poor outcome independent of azole therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(11):3148–55. [CrossRef]

- Fakhim H, Badali H, Dannaoui E, Nasirian M, Jahangiri F, Raei M, et al. Trends in the Prevalence of Amphotericin B-Resistance (AmBR) among Clinical Isolates of Aspergillus Species. J Med Mycol. 2022;32(4):101310. [CrossRef]

- Stewart ER, Thompson GR. Treatment of Primary Pulmonary Aspergillosis: An Assessment of the Evidence. J Fungi Basel Switz. 2016;2(3):25. [CrossRef]

- Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Mellado E, Peláez T, Pemán J, Zapico S, Alvarez M, et al. Population-Based Survey of Filamentous Fungi and Antifungal Resistance in Spain (FILPOP Study). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(7):3380. [CrossRef]

- Arendrup MC, Jensen RH, Grif K, Skov M, Pressler T, Johansen HK, et al. In vivo emergence of Aspergillus terreus with reduced azole susceptibility and a Cyp51a M217I alteration. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(6):981–5. [CrossRef]

- Zoran, T.; Sartori, B.; Sappl, L.; Aigner, M.; Sánchez-Reus, F.; Rezusta, A.; Chowdhary, A.; Taj-Aldeen, S.J.; Arendrup, M.C.; Oliveri, S.; et al. Azole-Resistance in Aspergillus terreus and related species: An emerging problem or a rare phenomenon? Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 516. [CrossRef]

- Vahedi-Shahandashti R, Dietl AM, Binder U, Nagl M, Würzner R, Lass-Flörl C. Aspergillus terreus and the Interplay with Amphotericin B: from Resistance to Tolerance? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022;66(4):e0227421. [CrossRef]

- Vahedi-Shahandashti R, Lass-Flörl C. Novel Antifungal Agents and Their Activity against Aspergillus Species. J Fungi. 2020;6(4):213. [CrossRef]

- Maertens JA, Raad II, Marr KA, Patterson TF, Kontoyiannis DP, Cornely OA, et al. Isavuconazole versus voriconazole for primary treatment of invasive mould disease caused by Aspergillus and other filamentous fungi (SECURE): a phase 3, randomised-controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2016;387(10020):760–9. [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen KM, Astvad KMT, Hare RK, Arendrup MC. EUCAST Susceptibility Testing of Isavuconazole: MIC Data for Contemporary Clinical Mold and Yeast Isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63(6):e00073-19. [CrossRef]

- Hoenigl M, Sprute R, Egger M, Arastehfar A, Cornely OA, Krause R, et al. The Antifungal Pipeline: Fosmanogepix, Ibrexafungerp, Olorofim, Opelconazole, and Rezafungin. Drugs. 2021;81(15):1703–29. [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki M, Horii T, Hata K, Watanabe NA, Nakamoto K, Tanaka K, Shirotori S, Murai N, Inoue S, Matsukura M, Abe S, Yoshimatsu K, Asada M. In vitro activity of E1210, a novel antifungal, against clinically important yeasts and molds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(10):4652-8. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe N aki, Miyazaki M, Horii T, Sagane K, Tsukahara K, Hata K. E1210, a New Broad-Spectrum Antifungal, Suppresses Candida albicans Hyphal Growth through Inhibition of Glycosylphosphatidylinositol Biosynthesis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(2):960–71. [CrossRef]

- Wring SA, Randolph R, Park S, Abruzzo G, Chen Q, Flattery A, Garrett G, Peel M, Outcalt R, Powell K, Trucksis M, Angulo D, Borroto-Esoda K. Preclinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamic Target of SCY-078, a First-in-Class Orally Active Antifungal Glucan Synthesis Inhibitor, in Murine Models of Disseminated Candidiasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(4):e02068-16. [CrossRef]

- Oliver JD, Sibley GEM, Beckmann N, Dobb KS, Slater MJ, McEntee L, et al. F901318 represents a novel class of antifungal drug that inhibits dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(45):12809–14. [CrossRef]

- Buil JB, Rijs AJMM, Meis JF, Birch M, Law D, Melchers WJG, et al. In vitro activity of the novel antifungal compound F901318 against difficult-to-treat Aspergillus isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(9):2548–52. [CrossRef]

- Risslegger B, Zoran T, Lackner M, Aigner M, Sánchez-Reus F, Rezusta A, et al. A prospective international Aspergillus terreus survey: an EFISG, ISHAM and ECMM joint study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(10):776.e1-776.e5. [CrossRef]

- Houbraken J, Kocsubé S, Visagie CM, Yilmaz N, Wang XC, Meijer M, et al. Classification of Aspergillus, Penicillium, Talaromyces and related genera (Eurotiales): An overview of families, genera, subgenera, sections, series and species. Stud Mycol. 2020;95:5–169. [CrossRef]

- Arendrup, M.C.; Guinea, J.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Meletiadis, J.; Mouton, J.W.; Lagrou, k.; Howard, S.J.; the Subcommittee on Antifungal Susceptibility Testing (AFST) of the ESCMID European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST. Method for the Determination of Broth Dilution Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations of Antifungal Agents for Conidia Form-ing Moulds. EUCAST definitive document DEF 9.3.2. Available online: https://www.aspergillus.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2016/03/EUCAST_E_Def_9_3_Mould_testing_definitive_0.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Lin SJ, Schranz J, Teutsch SM. Aspergillosis case-fatality rate: systematic review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2001;32(3):358–66. [CrossRef]

- Gintjee TJ, Donnelley MA, Thompson GR. Aspiring Antifungals: Review of Current Antifungal Pipeline Developments. J Fungi. 2020;6(1):28. [CrossRef]

- Fisher MC, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Berman J, Bicanic T, Bignell EM, Bowyer P, et al. Tackling the emerging threat of antifungal resistance to human health. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022;20(9):557–71. [CrossRef]

- LO Cascio G, Bazaj A, Trovato L, Sanna S, Andreoni S, Blasi E, Conte M, Fazii P, Oliva E, Lepera V, Lombardi G, Farina C. Multicenter Italian Study on "In Vitro Activities" of Isavuconazole, Voriconazole, Amphotericin B, and Caspofungin for Aspergillus Species: Comparison between SensititreTM YeastOneTM and MIC Test Strip. Infect Drug Resist. 2022;15:5839-5848. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhary A, Sharma C, Meis JF. Azole-Resistant Aspergillosis: Epidemiology, Molecular Mechanisms, and Treatment. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(suppl_3):S436–44. [CrossRef]

- Vahedi-Shahandashti R, Hahn L, Houbraken J, Lass-Flörl C. Aspergillus Section Terrei and Antifungals: From Broth to Agar-Based Susceptibility Testing Methods. J Fungi. 2023;9(3):306. [CrossRef]

- Berman J, Krysan DJ. Drug resistance and tolerance in fungi. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18(6):319–31. [CrossRef]

- Pfaller MA, Huband MD, Flamm RK, Bien PA, Castanheira M. Antimicrobial activity of manogepix, a first-in-class antifungal, and comparator agents tested against contemporary invasive fungal isolates from an international surveillance programme (2018–2019). J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2021;26:117–27. [CrossRef]

- Huband MD, Pfaller M, Carvalhaes CG, Bien P, Castanheira M. 2043. In Vitro Activity of Manogepix Against 2,810 Fungal Isolates from the SENTRY Surveillance Program (2020-2021) Stratified by Infection Type. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022 1;9(Supplement_2):ofac492.1665. [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Menendez O, Cuenca-Estrella M, Alastruey-Izquierdo A. In vitro activity of APX001A against rare moulds using EUCAST and CLSI methodologies. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74(5):1295–9. [CrossRef]

- Gebremariam T, Gu Y, Alkhazraji S, Youssef E, Shaw KJ, Ibrahim AS. The Combination Treatment of Fosmanogepix and Liposomal Amphotericin B Is Superior to Monotherapy in Treating Experimental Invasive Mold Infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022;66(7):e0038022. [CrossRef]

- Lepak AJ, Zhao M, Andes DR. Pharmacodynamic Evaluation of Rezafungin (CD101) against Candida auris in the Neutropenic Mouse Invasive Candidiasis Model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(11):e01572-18. [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold NP, Locke JB, Daruwala P, Bartizal K. Rezafungin (CD101) demonstrates potent in vitro activity against Aspergillus, including azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus isolates and cryptic species. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(11):3063–7. [CrossRef]

- Pfaller MA, Messer SA, Motyl MR, Jones RN, Castanheira M. In Vitro Activity of a New Oral Glucan Synthase Inhibitor (MK-3118) Tested against Aspergillus spp. by CLSI and EUCAST Broth Microdilution Methods. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(2):1065–8. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Ortigosa C, Paderu P, Motyl MR, Perlin DS. Enfumafungin derivative MK-3118 shows increased in vitro potency against clinical echinocandin-resistant Candida Species and Aspergillus species isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(2):1248–51. [CrossRef]

- Ghannoum M, Long L, Larkin EL, Isham N, Sherif R, Borroto-Esoda K, et al. Evaluation of the Antifungal Activity of the Novel Oral Glucan Synthase Inhibitor SCY-078, Singly and in Combination, for the Treatment of Invasive Aspergillosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(6):e00244-18. [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen KM, Astvad KMT, Hare RK, Arendrup MC. EUCAST Determination of Olorofim (F901318) Susceptibility of Mold Species, Method Validation, and MICs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(8):e00487-18. [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Menendez O, Cuenca-Estrella M, Alastruey-Izquierdo A. In vitro activity of olorofim (F901318) against clinical isolates of cryptic species of Aspergillus by EUCAST and CLSI methodologies. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74(6):1586–90. [CrossRef]

- Lackner M, Birch M, Naschberger V, Grässle D, Beckmann N, Warn P, et al. Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitor olorofim exhibits promising activity against all clinically relevant species within Aspergillus section Terrei. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(11):3068–73. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).