Introduction

Overpopulation of the planet leads to a much faster depletion of natural resources. The planet cannot by itself produce the necessary materials so needed by humanity. Unfortunately, only in recent history have discussions begun about how humanity uses natural resources at a much too high rate and excessively pollutes environmental factors, thus severely damaging the planet. This is very important because at some point the planet will try to restore its natural balance without taking into account the wellbeing of humanity. That is why it is important to focus as much as possible on the processes of recycling / reuse of as many materials as possible, thus using the resources of the planet to their full potential, resulting in lesser impact of us humans.

As the global population grows, so does the demand for cars. This need of mankind also leads to the emergence of many wastes from this industry. An important waste is that of lead-acid batteries. Such a component has existed in the construction of motor vehicles since the beginning of the internal combustion engine. Even if the vehicles continued to develop, by increasing in speed, efficiency or comfort, the battery part did not undergo major changes, these having the same operation principle since 1859, when they were invented. In the construction of a car battery there are heavy metals, acids but also plastic elements. These constructive elements have a strong negative impact on both human health and the environment, things that have quite quickly made humanity aware of the danger we face and pushed into taking immediate action in connection with recycling.

Due to various public information and battery collection campaigns, some even returning part of the cost of the battery at the time of delivery to a collection point, in the United States was recovered about 99% of the used lead from these batteries.

Battery components can be almost completely recycled and the main purpose is to recover used materials and integrate methods to avoid environmental pollution. The recycling of used electrodes from the car battery requires the integration of an eco-innovative technology, with low costs, energy efficiency and efficient desulphatization of the plates.

The recycling methods currently applied in this field are those of pyrometallurgy and hydrometallurgy [

1]. These methods have some major drawbacks including: high efforts to convert back to metal oxide, inefficient desulfatization, complexity and toxicity of methods [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Due to these shortcomings, it was necessary to create a new eco-innovative [

1,

6,

7,

8] way of recycling, having as main objectives that of reducing complexity and cost, obtaining the highest possible yield (about 95%) and obtaining an increased purity of the recovered substances.

Due to the fact that lead has strong negative effects on humans and the environment, this new approach in battery recycling manages to offer in addition to the economic and energy benefits already listed, also a drastic reduction in lead pollution which is emitted into the environment. This is another advantage of the proposed method that should not be overlooked because from the moment a quantity of lead is discharged into the environment until it affects the population, the road is short and the diseases that can be inflicted upon people are dangerous and should not be neglected.

The main inconveniences that yield to the rapid discharge of the car battery are the phenomena of anodic passivation, the evolution reactions of hydrogen and oxygen. Passivation phenomena are due to the irreversible polarization of the anode and consist in a stagnation of the metal passage, in the present case of metal lead, in the form of ions, when it plays the role of anode. Then, lead monoxide is the main contributor to premature capacity loss and the corrosion process of the positive electrode [

9].

The present paper aims to recycle anodic and cathodic plates from a spent car battery and to optimize them by the doping with nickel (II) oxide, NiO or cobalt (II, III) oxide, Co3O4 by melt quenching method, a method with lower cost and less polluation in view of applications in the field of origin - as a new electrode for the lead accumulator. Doping of the recycled material with nickel oxide (II) and double cobalt (II and III) oxide were chosen because these oxides can have an effect on the reactions of hydrogen evolution. Recycled and metal-doped samples were characterized by the analysis of X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and Electronic Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) spectroscopy The electrochemical performance of the new materials as electrodes for the car battery was tested by cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements.

Experimental procedure

The electrolyte from a spent car battery was drained, the anodic plates were separated from the cathodic ones, and the active mass from the anodic plate was used as a source of lead, while the active mass from the cathode plate was useful as source of lead dioxide. The NiO and Co3O4 powders were used as a dopant.

Four host matrices based on PbO2 - Pb in 4 : 1 molar ratio were prepared at four temperatures: 850, 900, 1000 and 1050 oC in order to select the optimal synthesis temperature. The temperature of 1050 oC was chosen as the most suitable for the recycling of the spent electrodes due to the better homogeneity of the samples. The matrix obtained was doped with nickel oxide in the following xNiO·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] composition where x = 0, 1, 5, 10 and 15 mol% NiO or cobalt oxide in the xCo3O4·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] composition where x = 0, 1, 5, 8, 10, 15, 25 mol% Co3O4. Substances according to predetermined chemical formulas, in stoichiometric proportions were weighed to the analytical balance to four decimal places (0.0001g). Mixtures of substances weighed in stoichiometric proportions were ground in an agate mortar and then placed in sintered alumina crucibles. The crucibles with the weighed mixture were placed in an electric oven setated at varried temperature of: 850, 900, 1000 or 1050 oC. After 10 minutes, the crucible with the melt was removed from the oven and quickly poured onto a stainless steel plate at room temperature.

The amorphous or crystalline nature of the prepared samples (the synthesized samples were finely ground into powder) was investigated by X-ray diffraction using a Shimadzu XRD-6000 diffractometer, using a graphite monochromator for a copper anode tube (with the wavelength, λ = 1.54 Å). IR absorption spectra were recorded at room temperature using the JASCO 6200 Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometer. EPR spectroscopy measurements were performed at room temperature, in the X frequency band, using the Adani PS 8400 spectrometer. For investigations, finely ground powders were used with the samples to be analyzed, which were introduced into glass tubes. All structural investigations, respectively: X-ray diffraction, IR and ESR spectroscopy were performed on powder samples.

The electrochemical properties of the samples obtained were tested by cyclic voltammetry measurements using an AUTOLAB PGSTAT 302N potentiostat / galvanostat (EcoChemie, The Netherlands) and NOVA 1.11 software. The samples obtained in the form of discs were used as working electrode, the platinum electrode was used as counter electrode, the calomel electrode as reference electrode, and the sulfuric acid solution, H2SO4 was used as electrolyte solution. All experiments were performed in 38% H2SO4 solution, to simulate the operating conditions of an electrode from the car battery.

Results and discussions

The colour of the prepared samples changes from yellow to brown by the adding of NiO content and from yellow to black by the adding of Co3O4 content, respectively in the host matrix.

Structural analysis by X-ray diffraction (XRD)

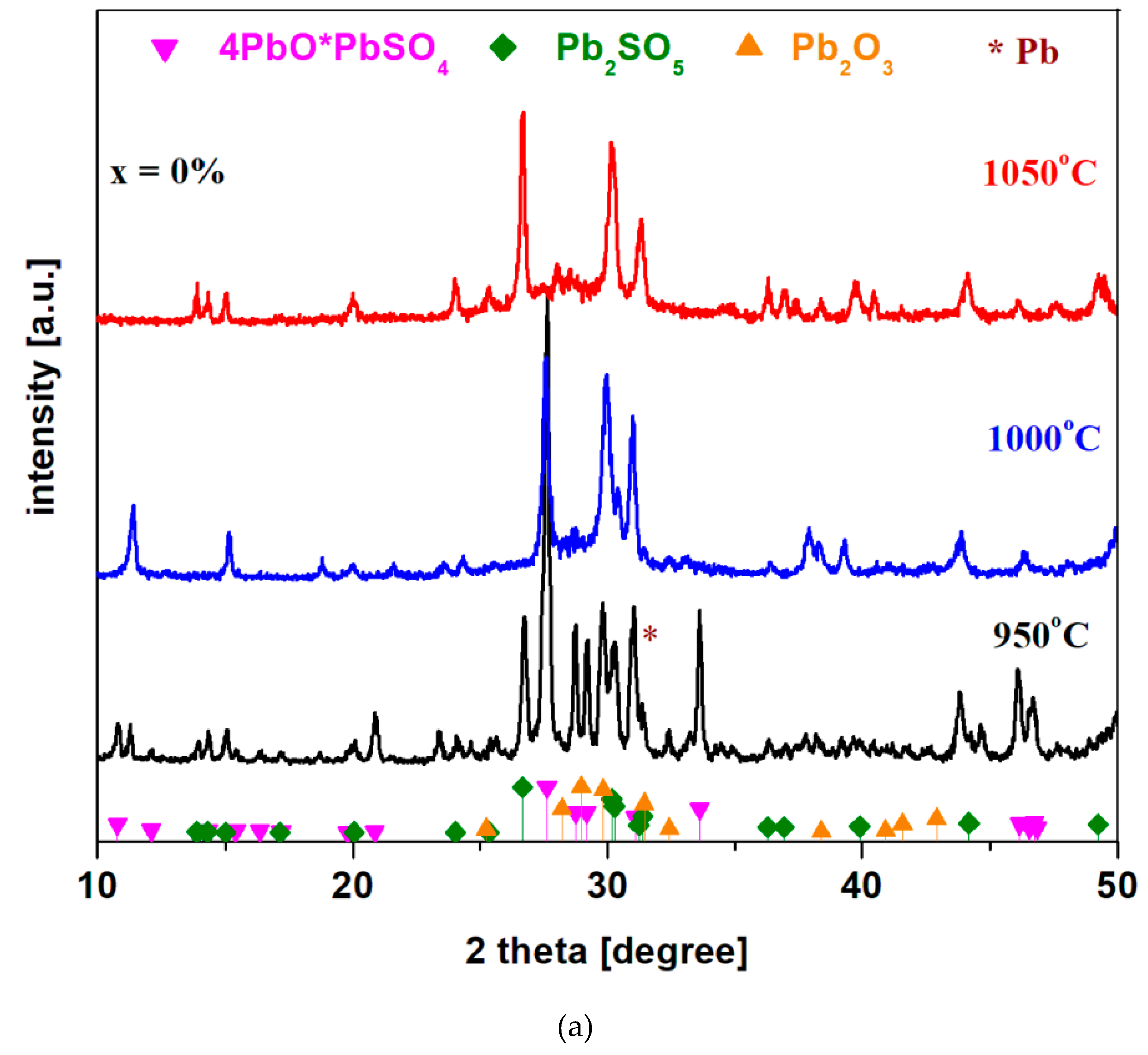

X-ray diffractograms of the system recycled from the electrodes of a spent car battery and doped with nickel oxide (II) in the xNiO·(100-x)[4PbO

2·Pb] composition where

x = 0 mol% NiO prepared at 950, 1000 and 1050

oC are shown in

Figure 1a). For the 4PbO

2·Pb host matrix prepared at 950

oC, four crystalline phases were found in the XRD data: 4PbO·PbSO

4, Pb

2SO

5≡PbO⸳PbSO

4, Pb

2O

3 and metallic lead (the diffraction peak centered at 31.3

o) crystalline phases. By increasing of the synthesis temperature to 1000 and 1050

oC, respectively, the peak corresponding to the metallic lead phase decreases in intensity, becoming undetectable at 1050

oC. At the synthesis temperature of 1000

oC, the 4PbO·PbSO

4 crystalline phase predominates and in the traces is found Pb

2SO

5 and Pb

2O

3 crystalline phases. At 1050

oC, the amount of Pb

2SO

5 crystalline phase attains maximum value, the 4PbO·PbSO

4 crystalline phase decreases to almost undetectable and in the traces the Pb

2O

3 crystalline phase is also identified.

As recycling is intended to remove the lead sulphates and oxo-sulphates content, namely 4PbO·PbSO4 and PbO·PbSO4 crystaline phases, the sample prepared at 1050 oC was selected as being suitable for doping, because has smaller amounts of 4PbO·PbSO4 crystalline phase. The results suggest that the synthesis temperature has an important effect on the vitroceramic structure. By increasing of the preparation temperature up to 1050 oC, some amounts of oxo-sulfated crystalline phases were decomposed because lead sulfate decomposes into sulfur oxides at over 1000 oC.

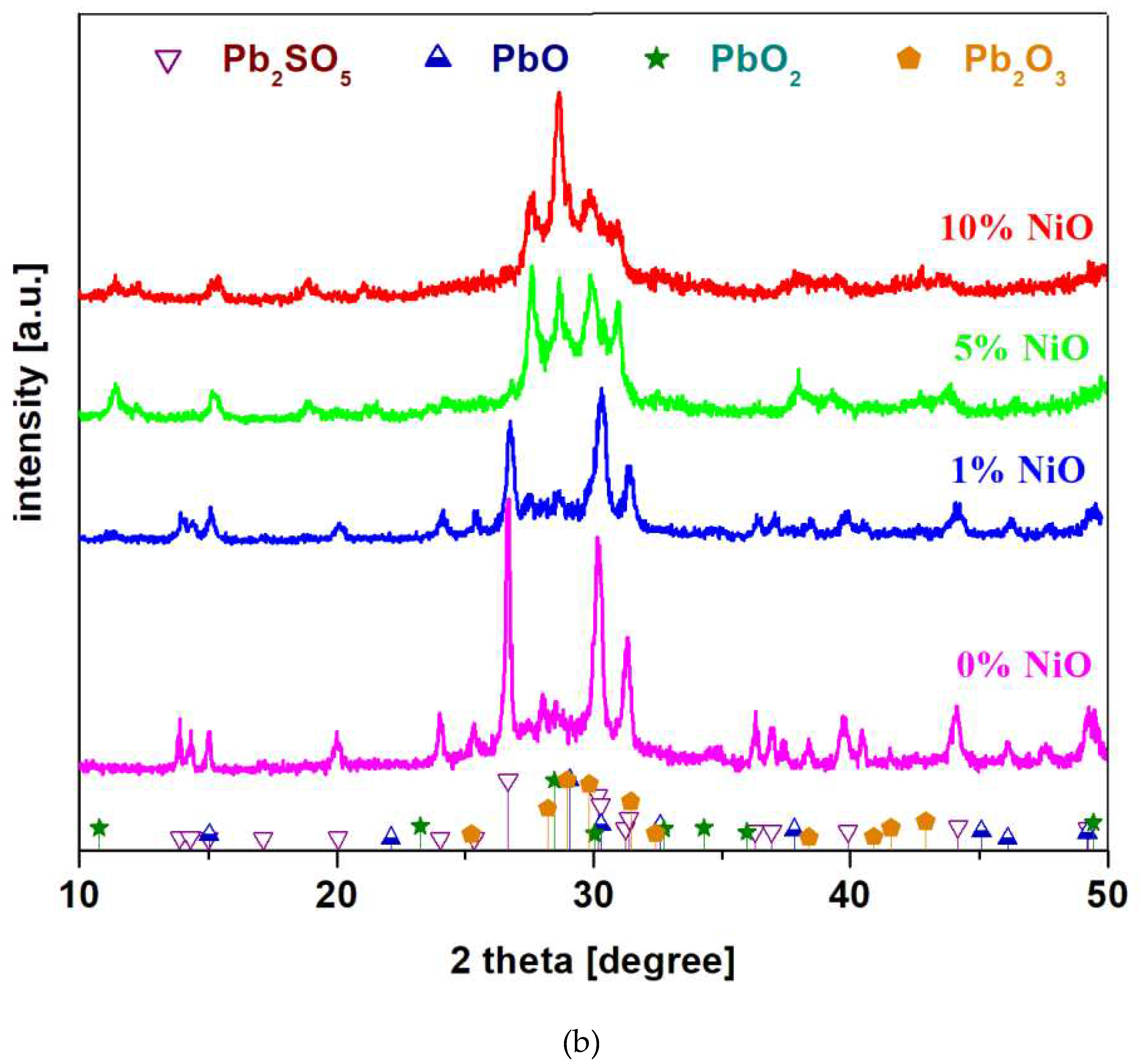

X-ray diffractograms of the recycled and metal-doped system in the xNiO·(100-x)[4PbO

2·Pb] composition where

x = 0, 1, 5 and 10 mol% NiO are represented in

Figure 1b). The analysis of XRD data indicates that the sample with

x = 0 mol% NiO contains main Pb

2SO

5 and Pb

2O

3 crystalline phases. By adding a smaller NiO content up to

x = 1 mol%, the same crystalline phases were highlighted as in the host matrix, but there is a decrease in the intensity of diffraction peaks corresponding to the Pb

2SO

5 crystalline phase, which indicates that its content decreases in the vitroceramic structure.

For the samples with x ≥ 5 mol% NiO appear new diffraction peaks characteristic of the Pb2O3, PbO2 and PbO crystalline phases. For the Pb2SO5 crystalline phase was evidenced a small diffraction peak centered at 26.91o corresponding to its intensity of 100%. For the sample with the x = 5 mol% NiO, the Pb2SO5 crystalline phase appears in traces below the detection limit of the diffractometer ( ≤ 1 – 2%). For the samples with x ≥ 5 mol% NiO, the content of PbO2 crystalline phase was increased.

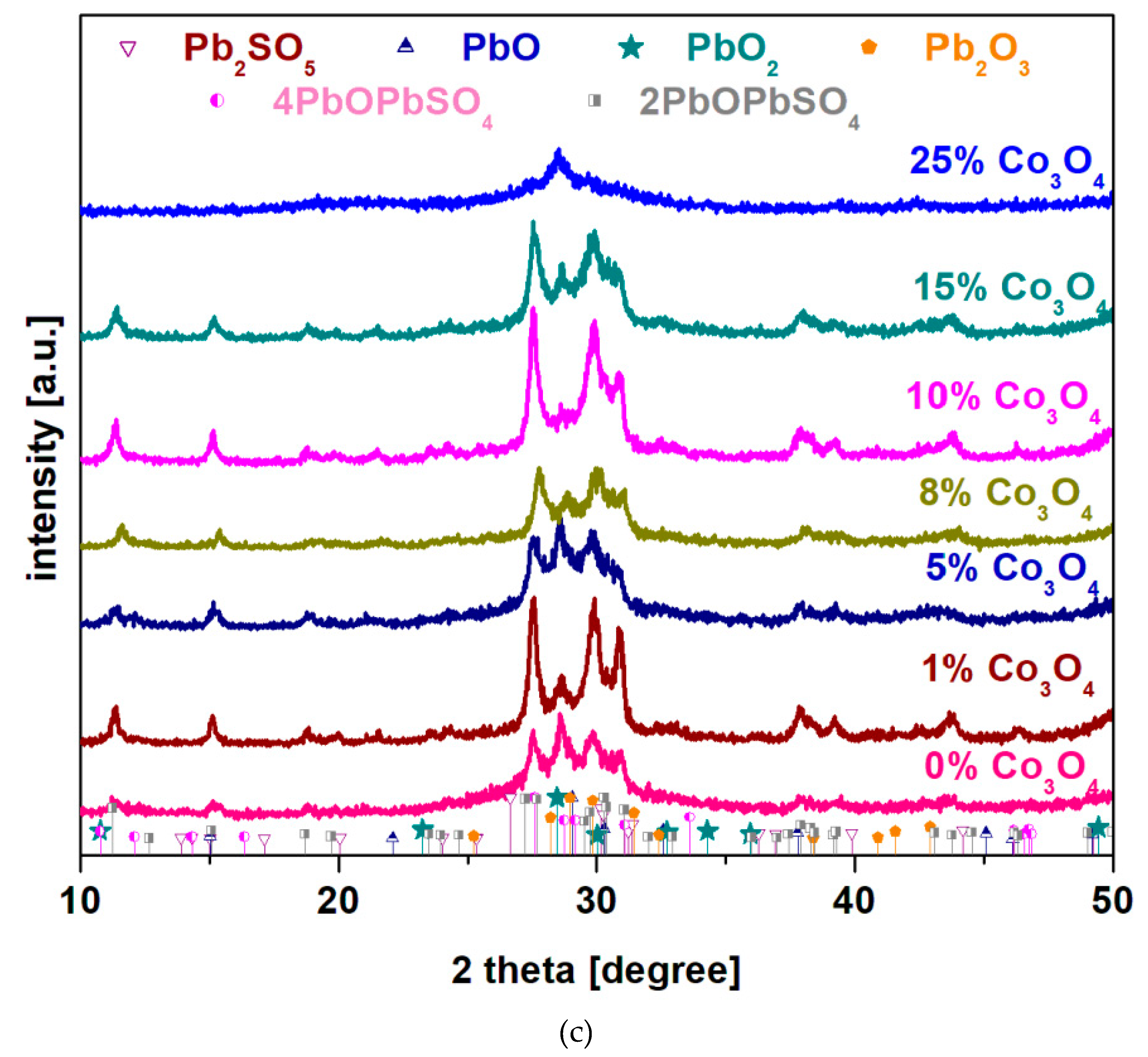

X-ray diffractograms of the recycled and Co-doped system in the xCo

3O

4·(100-x)[4PbO

2·Pb] composition where

x = 0, 1, 5, 8, 10, 15, 25 mol% Co

3O

4 are shown in

Figure 1c).

By the addition of smaller dopant contents, 1 ≤ x ≤ 10 mol% Co3O4, the presence of diffraction peaks attributed to the 4PbO·PbSO4, 2PbO·PbSO4, PbO and PbO2 crystalline phases in the vitroceramic structure was observed. For the sample with x ≥ 15 mol% Co3O4, small diffraction peaks corresponding to the Pb2O3=PbO·PbO2 crystalline phase are highlighted. For the sample with the highest dopant level, x = 25 mol% Co3O4, respectively in the diffractogram appears only small diffraction peaks corresponding to the lead oxides crystalline phase.

By the addition of higher dopant over x > 15 mol% Co3O4, the presence of cobalt ions ”accelerate” the decomposition of sulfated and oxo-sulphated phases in vitroceramic network and produce predominantly amorphous structure overlapped with small amounts of crystalline phase, respectively with the main diffraction peak of the PbO2 crystalline phase. As a result, the presence of cobalt ions plays an important role in the efficient desulfatization of spent and recycled electrodes by the melt quenching method.

In conclusion, in order to achieve an efficient desulfatization of the spent plates from the car battery, two factors must be taken into account: i) synthesis temperature - a high temperature achieves to the PbSO4 decomposition; ii) a suitable dopant content produces the efficient desulfatization of the spent electrodes up to lead oxides. For the samples with x ≥ 8 mol% NiO, the presence of the PbO2 and PbO crystalline phases was detected. X-ray diffractograms indicate a sudden decrease in the sulfated phase content and an increase in new diffraction peaks corresponding to the PbO2 crystalline phase by the addition of more than 10 mol% Co3O4 in the host matrix. This method has advantages of lower costs, less polution and efficient desulfatization processes of the spent plates from a lead-acid battery.

Structural investigations from FTIR spectra

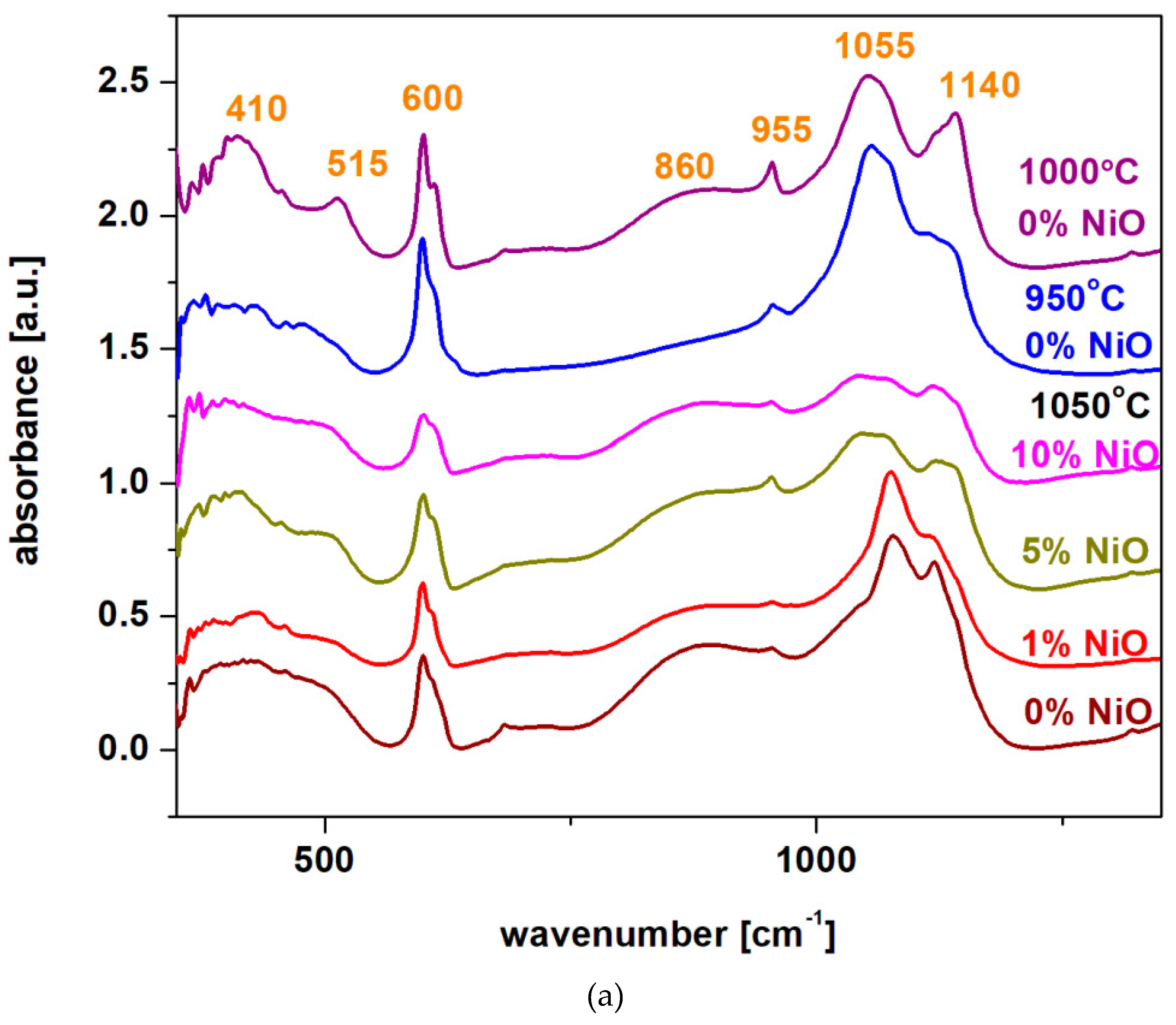

The FTIR spectra of the recycled and nickel-doped systems in the xNiO·(100-x)[4PbO

2·Pb] composition where

x = 0, 1, 5 and 10 mol% NiO are represented in

Figure 2a).

IR spectra indicate the regions of bands characteristic of different structural units in the vitroceramic structure. The IR band centered at 410 cm

-1 implies the bending vibrations of the Pb-O-Pb and O-Pb-O angles from the [PbO

4] structural units [

10,

11]. For the samples with

x = 0% prepared at 1000

oC and

x = 5 mol% NiO prepared at 1050

oC this band has the maximum intensity. These structural evolutions indicate a higher content of [PbO

4] pyramidal units in these vitroceramic structures.

The IR band centered at 600 cm

-1 derives from the overlaps of some contributions: Pb-O streching vibrations in the [PbO

n] structural units, the S-O and Ni-O stretching vibrations [

12]. By increasing the dopant level, a decrease of this IR band was observed, which can be explained by the decrease of the sulfate ions content in the host matrix. A decrease of sulphates content is possible during synthesis because it is known that lead sulphate decomposes at temperatures above 1000

oC. The IR band reaches its maximum value for the sample with

x = 0 mol% NiO prepared at 950

oC because has two major oxo-sulphates phases, namely 4PbO·PbSO

4 and PbO·PbSO

4 crystalline phases, according to XRD data (their decomposition did not take place at this synthesis temperature).

The IR band located at 1080 cm

-1 is associated with vibrations of elongation of S = O bonds from the sulfate units [

13]. The intensity of this IR band reaches high values for all samples with x = 0, independent of the sintering temperature, also for the sample with

x ≤ 1 mol% NiO. For samples with

x ≥ 5 mol% NiO a drastic decrease in the intensity of the IR band centered at 1050 cm

-1 was evidenced which suggests a sudden decrease in the amount of sulfate ions in the glass ceramics structure.

The temperature at which the recycling process takes place must be as close as possible to the point of thermal decomposition of lead sulphate - in this case the temperature of 1050 oC (the 4PbO·PbSO4 crystalline phase disappears) is more suitable than that of 1000oC (where the process of decomposition of the 4PbO·PbSO4 crystalline phase begins). The increase of the dopant level over x ≥ 5 mol % NiO “helps” with the thermal decomposition of the oxo-sulphates phases - in the studied case of the PbO·PbSO4 crystalline phase was detected below the detection limit of the diffractometer.

The region of IR bands centered at 610, 875, 1050 and 1150 cm-1 are attributed to the stretching vibrations of the Pb-O bonds in the [PbOn] structural units with n = 3, 4 and 6. The intensity of these IR bands increases by the addition of higher amounts of dopant levels, which suggests the “enrichment” of vitroceramics in crystalline phases based on lead oxides, according to XRD data. By doping the intensity of the IR band centered at 875 cm-1 increases sugesting the formation of [PbO6] structural units. For samples with x ≥ 5 mol% NiO, the position of the IR band centered at 1150 cm-1 shifts to higher wave numbers, which indicates conversions to the [PbOn] structural units with n = 3 and 4 (predominantly n = 3). By doping with high levels of NiO the transformation of the sulphated vitroceramic into a vitroceramic consisting mainly of [PbOn] structural units with n = 3, 4 and 6 (in which n = 3 and 6 predominate) was demonstrated.

In conclusion, the analysis of IR data indicates important structural changes in the vitroceramic structure depending on the synthesis temperature at which the recycling of spent electrodes took place and the concentration of nickel oxide added in doping. If the method of obtaining the glass ceramic allows for a wider range of synthesis ± 200 oC, the sintering temperature which is optimum for recycling will be chosen as close as possible to the decomposition point of lead sulphate - in the studied case 1050 oC. By adding a suitable NiO content, x > 5 mol% NiO, in the vitroceramic structure takes place a process of total decomposition of lead sulfate and as results, the formation of a mixture of lead oxides, respectively Pb2O3, PbO2 and PbO crystalline phases were happened. For samples with x > 5% mol NiO, IR data indicate significant structural changes in the intensity and position of the bands corresponding to [PbOn] structural units with n = 3 and 6. For samples with x < 5 mol% NiO, a characteristic feature of centered sulfate units is highlighted at 1050 cm-1. For host matrices prepared at temperatures below 1050 oC, the intensity of this IR band is highly. This evolution suggests the presence of a higher content of sulfated crystalline phases in host vitroceramics, according to XRD data.

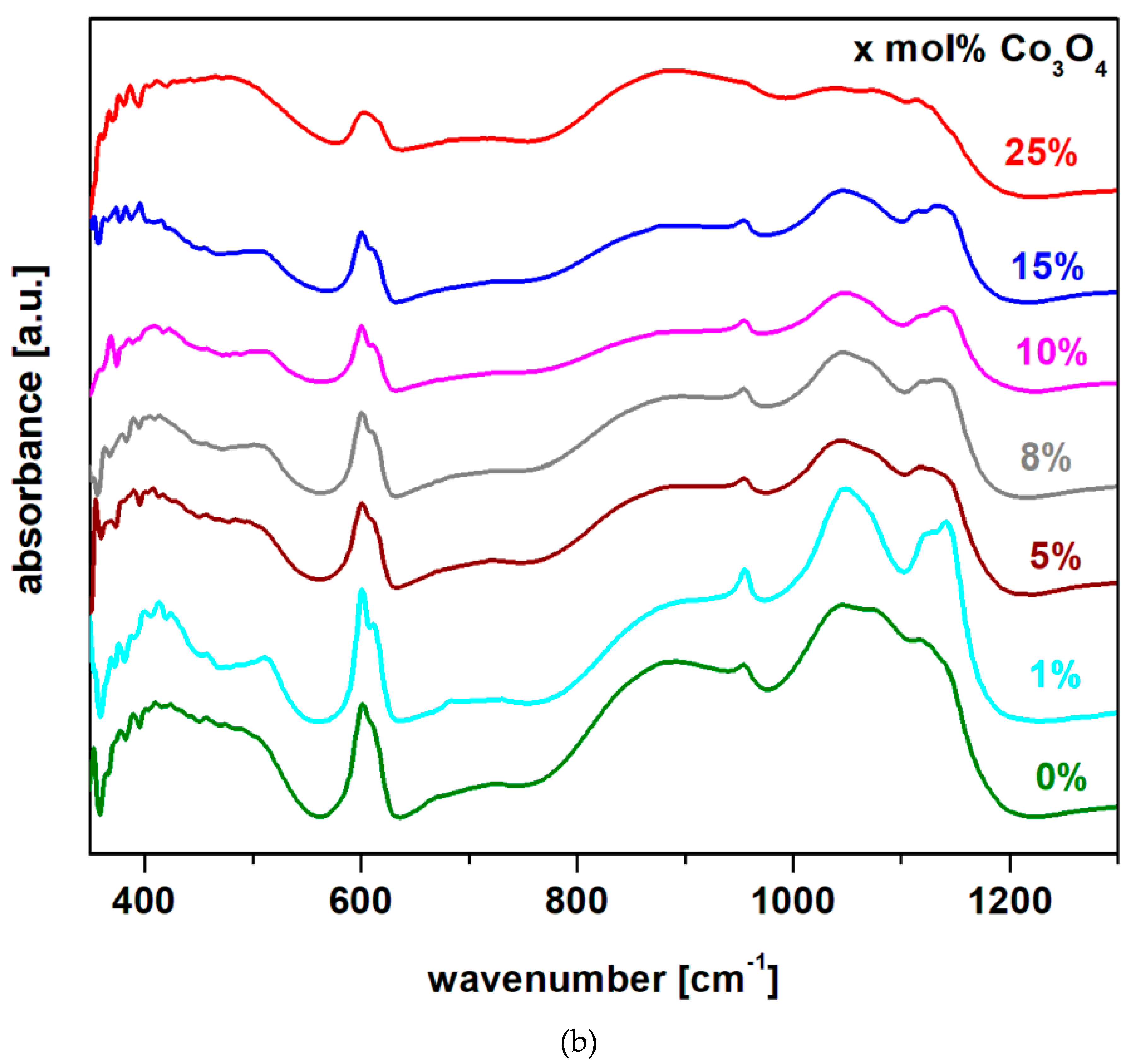

FTIR spectra of the system recycled from the electrodes of a spent lead acid battery and doped with cobalt (II) and (III) oxide in the xCo

3O

4·(100-x)[4PbO

2·Pb] composition,

x = 0, 1, 5, 8, 10, 15, 25 mol% Co

3O

4 are represented in

Figure 2b).

The analysis of IR data indicates some important structural modifications by increasing the Co3O4 content in the vitroceramic matrix, which can be systematized as follows:

i) The first region of IR bands located in the range between 360 and 550 cm-1 corresponds to the bending vibrations of the Pb-O-Pb and O-Pb-O angles in the [PbO4] structural units. By increasing the Co3O4 content, the intensity of these bands were increased and the band centered at 470 cm-1 reaches its maximum value for the sample with x = 25 mol%. For the sample with x = 25 mol% Co3O4, the increase of the number of [PbO4] structural units by the doping process produces the formation of the PbO2 crystalline phase in the vitroceramic structure, in agreement with the XRD data.

ii) The second region of IR bands centered at 600 cm-1 corresponds to some contributions: the stretching vibrations of the Pb-O bonds in the [PbOn] structural units superimposed with the stretching vibrations of the Co-O and S-O bonds in the sulfate ions. At higher dopant contents , the intensity of this band decreases due to the disappearance of the oxo-sulphatated phases from the vitroceramic network.

iii) The third region of IR bands located between 650 and 950 cm-1 is associated with the stretching vibrations of Pb-O bonds in [PbOn] structural units with n = 3, 4 and 6. The intensity of the IR band centered at 875 cm-1 corresponding to the [PbO6] octahedral units increases by doping with higher Co3O4 levels. This evolution suggests that the excess of oxygen atoms can be accommodated in the host matrix by the convertion of [PbO3] trigonal units into [PbOn] structural units with n = 4 and 6.

iv) The last region of high-intensity IR bands situated between 950 and 1200 cm

-1 is attributed to the stretching vibrations of the S = O bonds in the sulphate units [

14] (IR band located at 1080 cm

-1) overlapps with the stretching vibrations of the Pb-O bond in the [PbO

n] structural units with

n = 3 and 4. For undoped samples, the intensity of the band centered at 1080 cm

-1 suddenly decreases, by the increasing of the sintering temperature from 850 to 1050

oC, suggesting the decomposition of a significant amount of lead oxo-sulphate, according to XRD data.

For samples with x > 15 mol% Co3O4 these IR bands shift towards smaller wave numbers due to the [PbO3] →[PbO4] conversion and the formation of the PbO2 crystalline phase. The addition of a suitable Co3O4 content in the structure of the glass ceramic, namely x > 15 mol% Co3O4, produces a process of total decomposition of lead oxo-sulphate and as result, the formation PbO2 crystalline phase was evidenced.

Structural investigation by EPR data

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) data will be used to determine the coordination geometry of the nickel or cobalt ions in the vitroceramic structure.

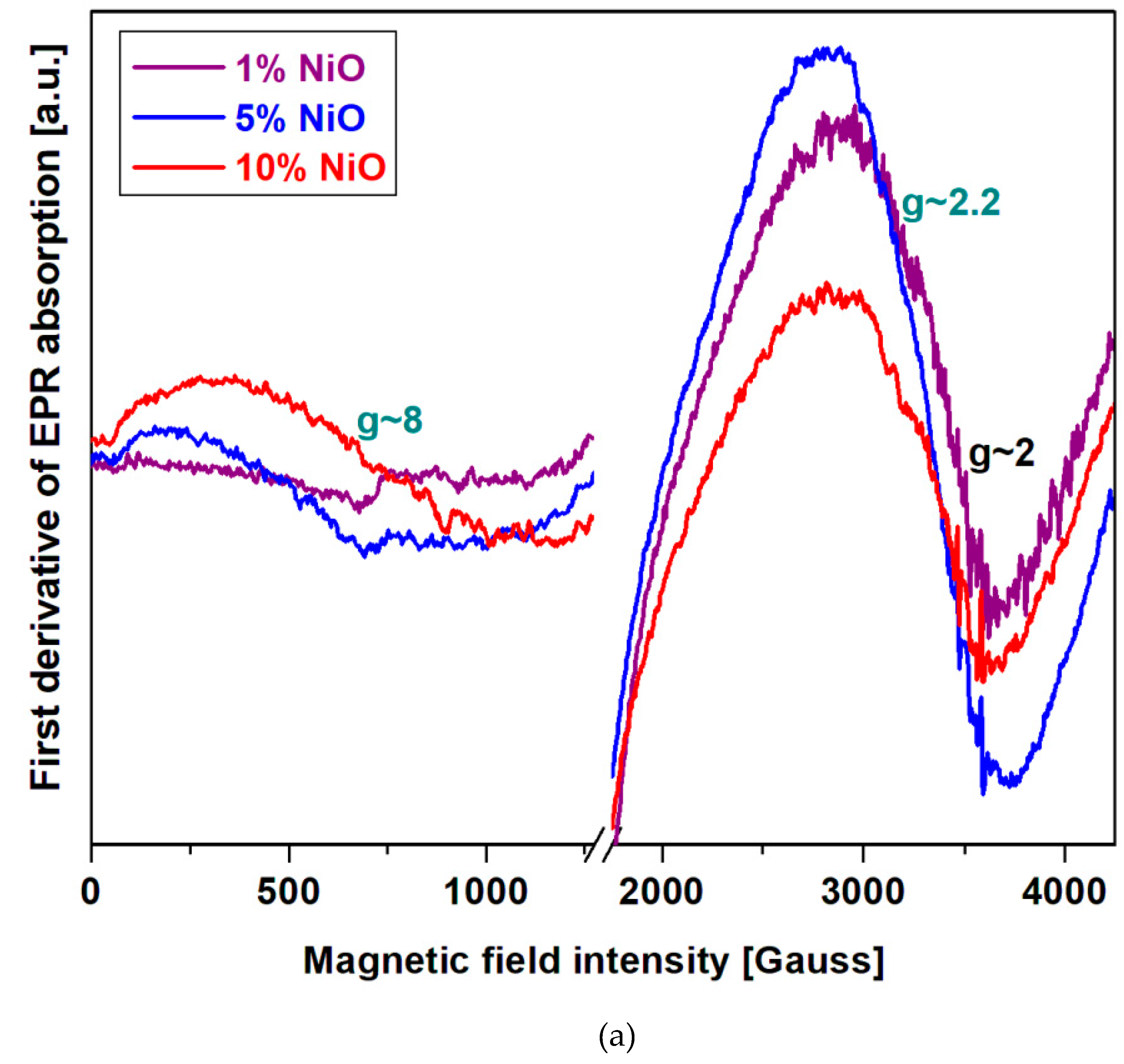

Figure 3a) shows the EPR spectra of the recycled system in the xNiO·(100-x)[4PbO

2·Pb] composition where

x = 1, 5 and 10 mol% NiO. The EPR data indicate three resonance lines centered at

g ~ 2, 2.2 and 8 for all studied samples and their intensities depend on the nickel content of the host matrix.

The Ni

+2 ions in the oxide glasses [

14,

15] have an asymmetric resonance line normally located at

g ~ 2.1 - 2.38 [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. In the case of lithium-bismuth-borate glasses, the EPR signal was reported at

g ~ 2.7 [

18]. These wide deviations of the value of g from the normal ones can occur due to the fact: a) the spin-orbit coupling process and the influence of the Ni

+2 microvecinity; b) the superexchange interactions between nickel ions by nonmagnetic oxygen ions that decrease the intensity of the magnetic field and increase of the g value.

The Ni

+3 ions of the oxidic compounds have contributions to the wide EPR absorption band situated at

g ~ 2 and 2.15 [

21]. This signal is characteristic to the Ni

+3 ions situated in the pseudooctahedral sites with rhombic structure. The Ni

+3 ions can appeared by an oxidation process of Ni

+2 ions to Ni

+3 ions based on the reduction of lead ions and/or in the during of synthesis.

The wider resonance line centered at

g ~ 8 is attributed to metallic nickel nanoparticles [

14] that can occur as a result of the reduction of nickel ions in higher oxidation states +2 (from the raw material) and +3 (in the during of synthesis through the oxidation process).

Analysis of the EPR data indicates that the intensity of the resonance lines located between g ~ 2 and 2.2 decreases with the increasing of NiO content in the vitrocermic matrix, while the wider signal centered at about g ~ 8 becomes more intensely by the doping process. This compositional evolution can be explained considering to the Ni+2 and/or Ni+3 reduction into metallic nickel nanoparticles.

The responsible mechanisms of these structural evolutions can be summarized as follows: i) for lower dopant contents, x ≤ 1 mol% NiO, the resonance line centered between g ~ 2 and 2.2 becomes dominantly in the EPR spectrum which indicates the presence of Ni+2 and several Ni+3 ions obtained in the during of synthesis by the Ni+2 oxidation process; ii) for samples with 5 ≤ x ≥ 10 mol% NiO, the intensity of the resonance line centered at g ~ 8 increases while the signals situated at g ~ 2 and 2.2 were decreases gradually. This suggests the Ni+2 and Ni+3 → Nio conversion. This conversion process is more pronounced for the sample with x =10 mol% NiO.

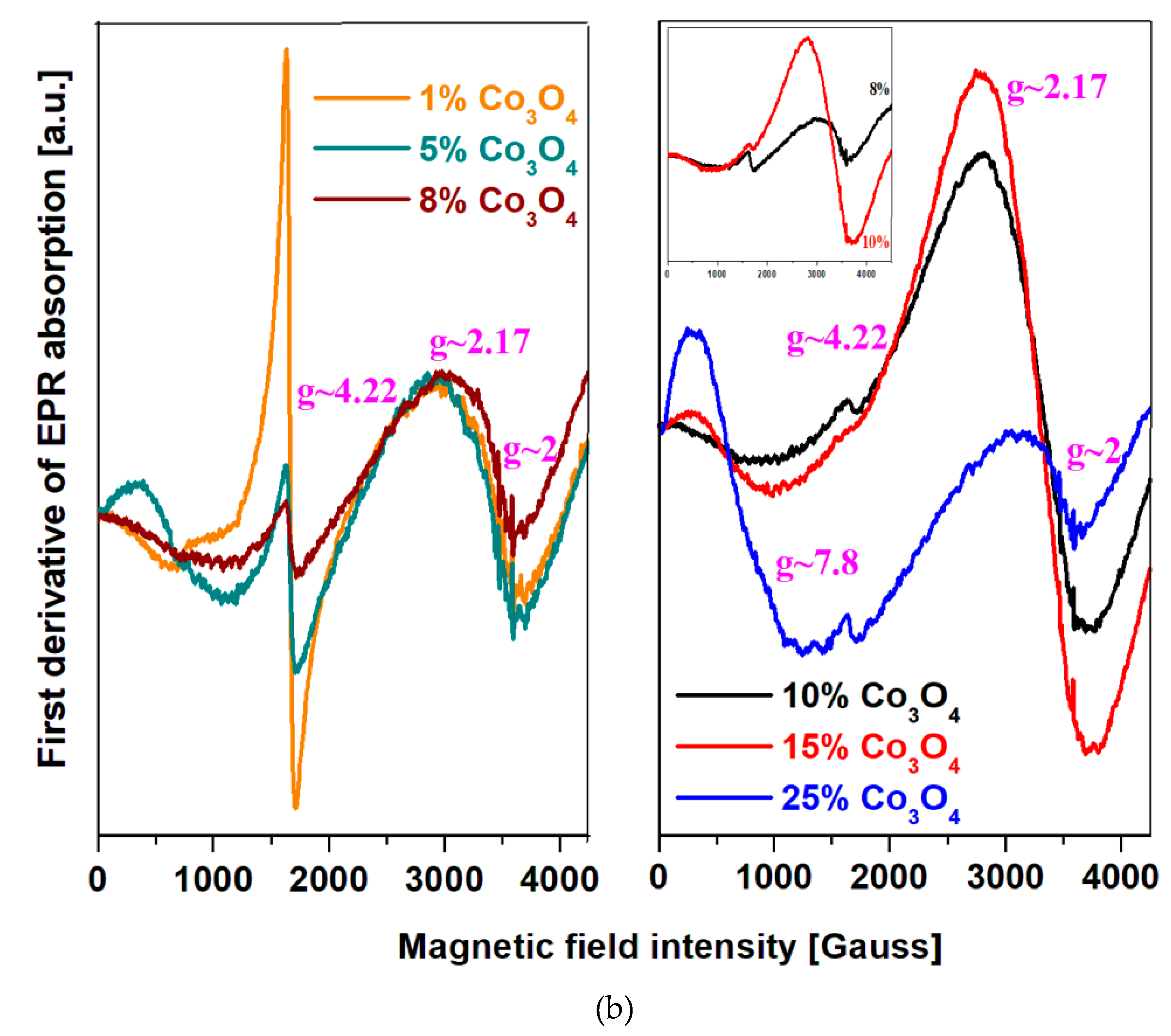

EPR spectra of the xCo

3O

4·(100-x)[4PbO

2·Pb] samples where

x = 1, 5, 8, 10, 15 and 25 mol% Co

3O

4 are given in the

Figure 3b). EPR data reveal four resonance signals centered at

g ~ 2, 2.17, 4.22 and 7.8. The resonance line centered at

g ~ 4.22 corresponds to the high spin of Co

+2 ions (S = 3/2) in octahedral sites while the absorption at

g ~ 2.17 can be ascribed to the isolated Co

+2 ions (S = 3/2) occupying tetrahedral geometries [

22,

23,

24]. The resonance signal located at about

g ~ 7.8 were attributed to the S = 3/2 state of the Co

+2 ions.

For the recycled and cobalt-doped samples, the contribution of three distinct features of the EPR spectrum modifies clearly with the increasing of Co3O4 content. These structural evolutions can be summarized as follows:

i) The resonance line located at about g ~ 2 including a hyperfine structure is assigned to the coupled or clusters Co+2 ions overlapped with Co+2 ions with low spin (S = 1/2) for octahedral symmetry. For the sample with x = 1 mol% Co3O4 the shape and feature of the resonance signal with hyperfine structure situated at about g = 2 can be same with the sample are very similar for the samples with x = 1 and 5 mol% Co3O4. For the sample with x = 8 mol% Co3O4 the eight line of the hyperfine structure was weak – resolved, the intensity of the signals located at g ~ 2 and 4.22 decrease and appears a new line centered at about g ~ 2.11.

In first stage at the adding of 1 mol% Co3O4 in the host matrix, the Co+2 ions ocuppy octahedral positions with high spin (g ~ 4.22) and low spin (g ~ 2). By the increasing of dopant level up to 15 mol% Co3O4 the feature of the signals located at about g ~ 2 and 2.11 broadens, changes shapes, increases in intensity and after that their intensities were decreased for the sample with x = 25 mol % Co3O4. For the samples with x = 10 and 15 mol% Co3O4 the tetrahedral geometry of the Co+2 ions reachs maximum value. The accommodation with oxygen excess can be realized by the conversion of octahedral positions with high spin in tetrahedral sites with high spin. After that, the adding of oxygen ions in the host matrix up to 25 mol% Co3O4 yields the conversion of tetrahedral into octahedral positions of the Co+2 ions.

ii) The contribution of the feature located at g ~ 4.22 decreases with increasing cobalt concentration. At higher content over 8 mol % Co3O4 this feature disappears almost completely in the EPR spectrum.

iii) The intensity of eight lines located at about g ~ 7.8 increases when the Co3O4 content increased from 1 to 25 mol%.

By increasing of cobalt content up to 25 mol % in the host matrix was evidenced an abruptly decreasing of the resonance line situated at about g ~ 2.17, the signal located at about g ~ 4.22 has a weak intensity and the resonance line located at g ~ 7.8 attains its maximum value. These compositional evolutions can be explained considering a conversion of four - coordinated sites into six - coordinated of the Co+2 ions sites and the transformation of Co+2 ions into Co+3 ions (no give EPR signal) by doping with higher Co3O4 levels.

The mechanism responsible for these evolutions can be described as follows: i) for samples with x ≤ 5 mol% Co3O4, the Co+2 ions ocuppy the octahedral sites; ii) for the samples with 8 ≤ x ≤ 15 mol% Co3O4, a conversion process of octahedral sites in tetragonal positions of the Co+2 ions was happened; iii) for higher dopping level up to 25 mol% Co3O4, the excess of oxygen ions can be acoomodation in the vitroceramic network by the transformation of tetrahedral positions into new octahedral sites of the Co+2 ions (the increase of intensity of the low-field resonance line situated at about g ~ 7.8 due to the high spin, S = 3/2 of the Co+2 ions). Quantitation of EPR spectra shows that the most of Co+2 ions are EPR visible at low dopant content in host matrix and a part of the Co+2 ions is oxidized to Co+3 ions for higher Co3O4 level.

Cyclic voltammetry measurements (CV)

The electrochemical performance of recycled materials, doped with nickel or cobalt oxide, as working electrodes on the car battery, was investigated by cyclic voltammetry measurements. To simulate the behavior of the electrode in the car battery was used an electrochemical cell with three electrodes: the reference electrode - calomel, the working electrode - recycled and metal-doped sample, and the counter electrode - platinum electrode, which are all immersed in a solution of sulfuric acid with a concentration of 38 %.

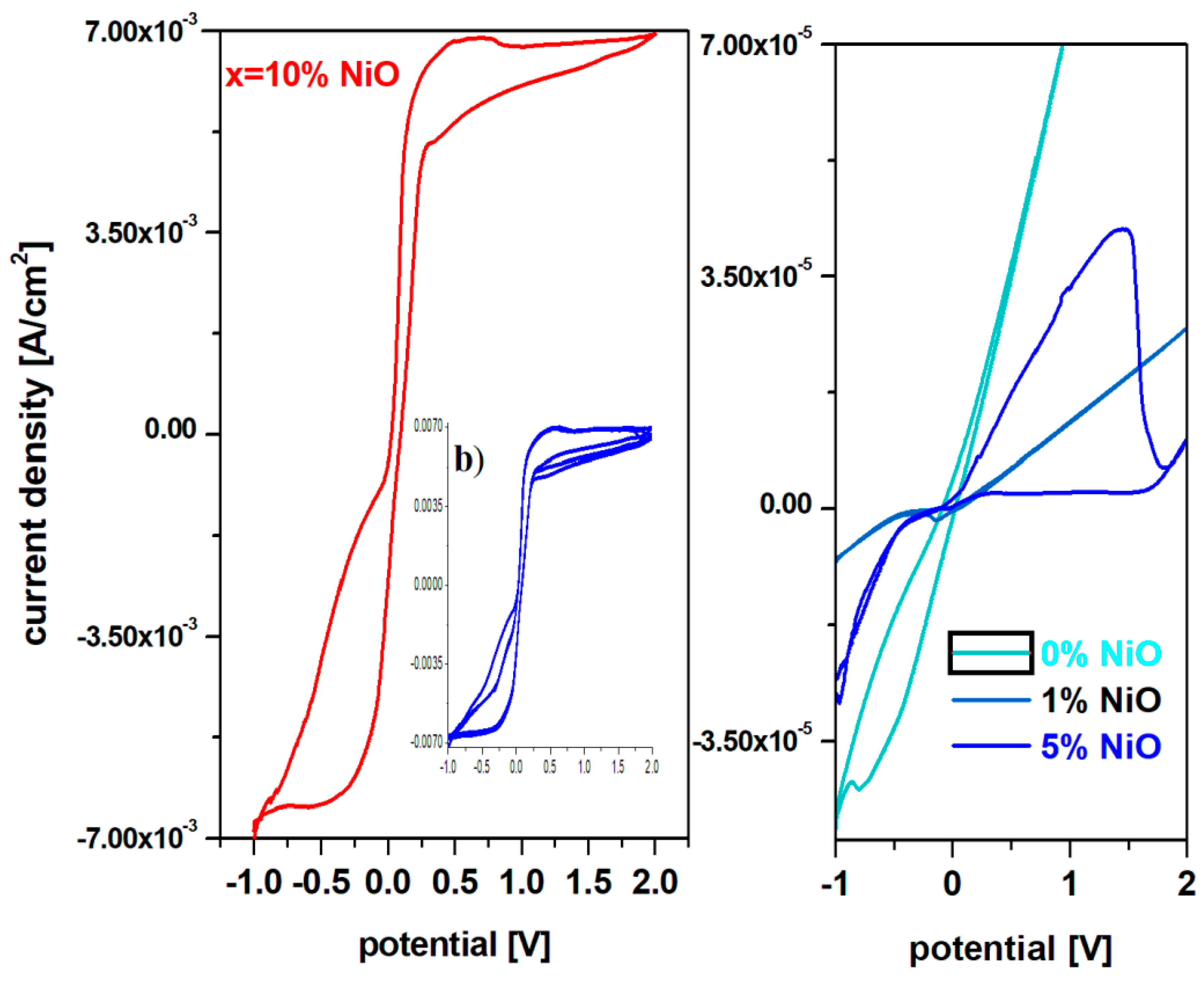

Cyclic voltamograms of electrode materials in the composition xNiO·(100-x)[4PbO

2·Pb] where

x = 0, 1, 5 and 10 mol% NiO are shown in

Figure 4a).

A simple inspection of cyclic voltammograms for the prepared electrode materials indicates that the current density increases almost 100 times for the samples with x = 10 mol% NiO. For the recycled and nickel-doped materials with a low NiO content of up to x = 1 mol% cyclic voltamograms highlight the presence of the electrode passivation phenomenon which consists in the sudden decrease of current intensity in the positive region of the potential – after 0V. For the electrode material with x = 5 mol% NiO, a well-defined and oxidation wave centered at ~ 1.2 V is observed in the positive region of the current density, which corresponds to the O2/H2O redox system and the reactions of oxygen evolution.

In the region with the positive current density for the electrode material containing x = 10% NiO three main oxidation waves appear centered at: -0.54 V, +0.5 V and +1.68 V corresponding to the HPbO2- / Pb (-0.54 V), PbO / Pb (-0.58 V), Ni2O3 / Ni(OH)2 (+0.5 V) and PbO2 / PbSO4 (+1.68 V) redox systems. In the cathode region there are two well-defined reduction peaks centered at 0.5 V, attributed to the Ni2O3 / Ni(OH)2 redox system and -0.354 V respectively assigned to the PbSO4 / Pb redox process and a small peak located at -0.126 V corresponding to the Pb+2 / Pbo redox system [7, 8].

For the electrode material containing x = 10 mol% NiO is observed from the cyclic voltammogram that the current density is higher than its analogue with x ≤ 10 mol% NiO. Figura 5a) shows the cyclic voltammograms of the electrode materials with x = 10 mol% NiO, after scanning three cycles. Cyclic voltammograms have a high degree of irreversibility because there is a pronounced dimerization effect of sulfate ions due to the S2O8-2 / 2SO4-2 redox process, which appears located at 2 V and as a result changes the oxidation peak attributed to the Pb+2 / Pbo redox system.

These structural developments suggest that redox couples do not produce completely reversible reactions. The main drawbacks that lead to the irreversibility of the cyclic voltamogram are the reactions of oxygen evolution and the dimerization of sulfate ions.

Therefore, cyclic voltammetry measurements indicate significantly higher electrochemical performance of recycled and doped materials with x = 10 mol% NiO compared to undoped or with a lower dopant content, which recommends them as suitable for batteries electrode. Doping with a suitable level of nickel oxide (II) removes the phenomenon of electrode passivation and hydrogen evolution reactions and the intensity of the residual current increases in the range 0 and 2 V. The high degree of irreversibility of cyclic voltammograms of electrode materials with a higher dopant level, respectively x = 10 mol% NiO due to the presence of the dimerization reactions of sulfate ions, yield to changes in electrolyte concentration and the disadvantage that upon discharging the battery, it cannot be recharged by the electrolysis process – it discharges current in the opposite direction using a generator.

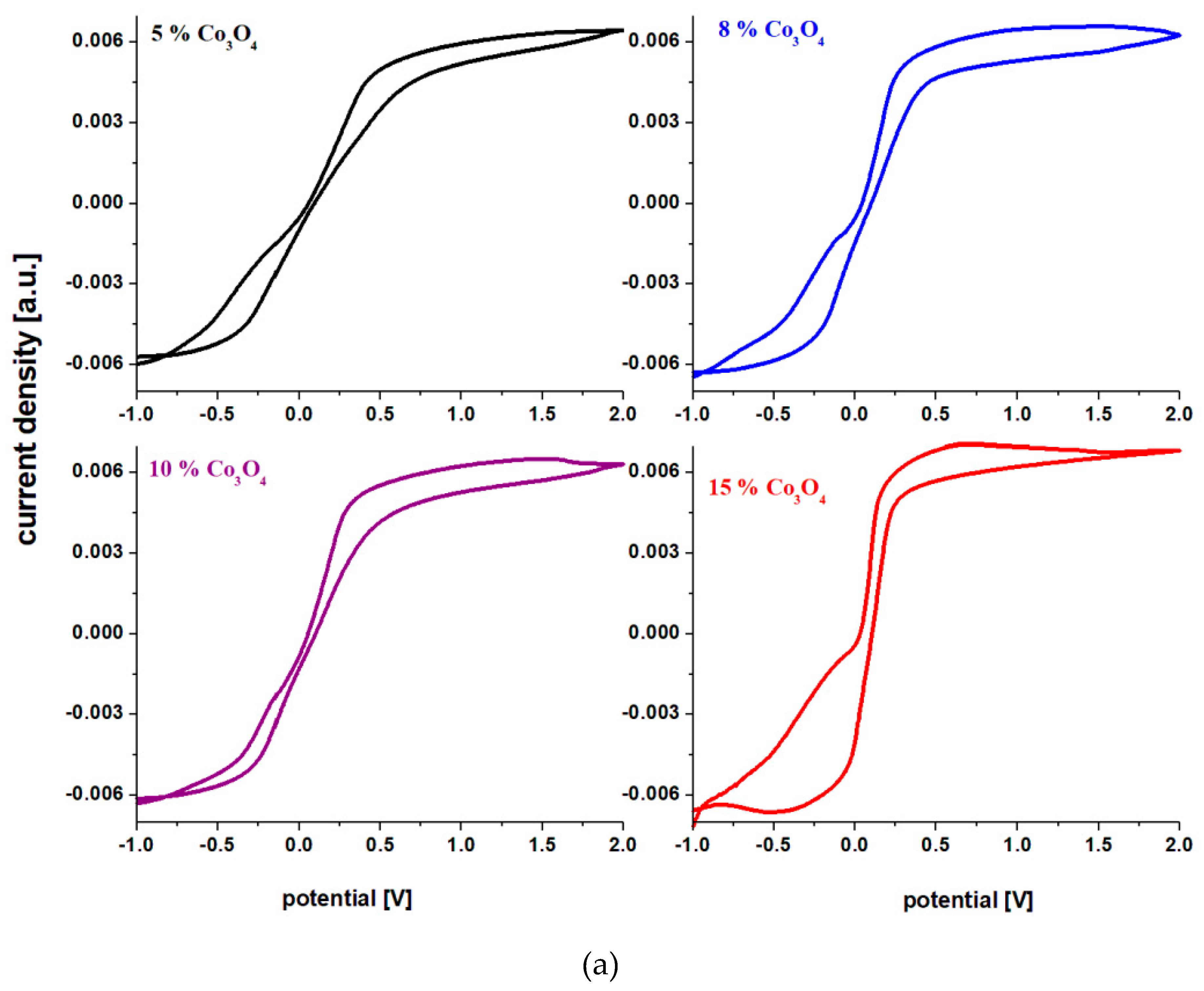

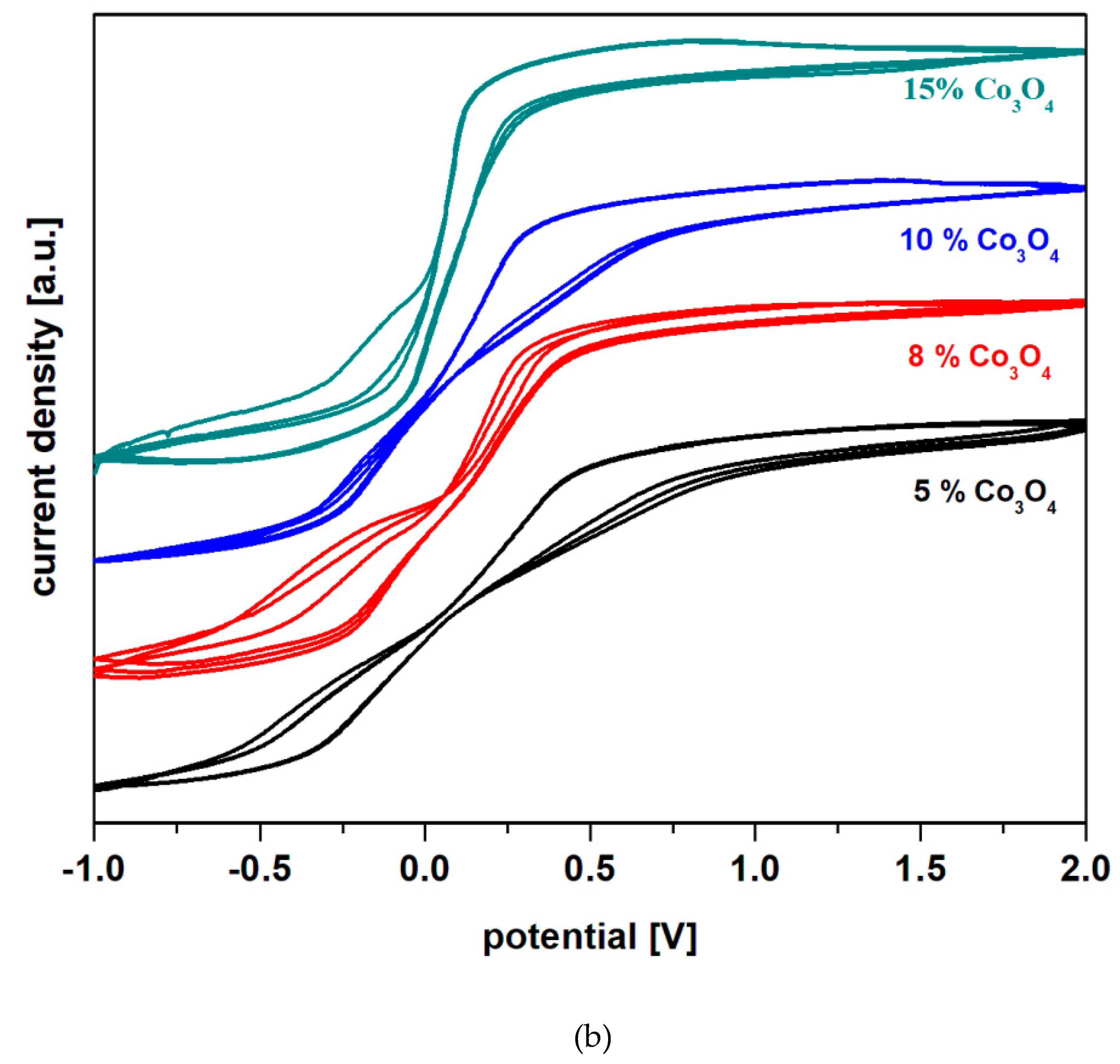

Cyclic voltamograms of electrodes formed from recycled materials and doped with cobalt (II) and (III) double oxide, having the composition xCo

3O

4·(100-x)[4PbO

2·Pb] with

x = 0, 1, 5, 8, 10, 15 mol% Co

3O

4 are shown in

Figure 4c).

In the cyclic voltamograms of the samples no evolutionary reactions of hydrogen are observed (-0.82 V) and oxidation peaks appear, respectively reduction peaks better formed only for samples with higher dopant content. For this reason we will discuss in more detail the oxidation and reduction waves for the sample with x = 15% moles of Co3O4. In the region with positive current density there are two oxidation peaks centered at: -0.25 and 0.5 V. The first peak in the anodic region corresponds to an overlap of waves from the redox systems Pb+2/Pb0 (located at -0.126 V) [15-20] and Co+2/Coo (centered at -0.28 V). The second peak centered at 0.5 V extending to the region above 1.23 V (much better defined and much more intense for the material with x = 20 mol% Co3O4) is responsible for the increase in current density in the range 0 and 2 V. These peaks correspond to the following two redox systems: Co+3/Coo (wave located at +0.33 V) and O2/H2O (wave centered at 1.23 V).

In the anodic region the following oxidation processes can be produced:

In the cathodic region there is a well-defined reduction peak for the electrode material containing

x = 15 mol% Co

3O

4 centered at -0.35 V corresponding to the redox system PbSO

4 / Pb (-0.345 V) superimposed with the wave from the redox systems Pb

+2 / Pb

o (located at -0.126 V) and Co

+2 / Co

o(centered at -0.28 V). As a result, a new reduction process appears in the cathodic region, which can be represented as follows:

These evolving trends in redox processes suggest that redox couples do not produce completely reversible reactions. In order to verify this hypothesis in

Figure 5b) we graphically represented the cyclic voltamograms, after scanning three cycles recorded in 38% sulfuric acid solution for recycled electrode materials having the composition xCo

3O

4·(100-x)[4PbO

2·Pb] where

x = 5, 8, 10, 15 mol% Co

3O

4. Inspection of cyclic voltamograms scanned after three cycles indicates their irreversibility for all samples studied, except for the sample with

x = 10 mol% Co

3O

4. A lower degree of irreversibility is observed for the sample with

x = 10 mol% Co

3O

4, but the reduction peaks are weak and much delayed.

In general, the main processes responsible for the irreversibility of the cyclic voltamogram are due to the following redox processes: i) the presence of lead oxide in the structure of recycled glass ceramic that produces two types of redox processes HPbO2- / Pb, located at -0.54 V and PbO / Pb centered at -0.58 V; this effect is most pronounced for the sample with x = 8 mol% Co3O4; ii) the presence of cobalt ions in the Co+2 / Coo redox system (centered at -0.28 V) with a strong effect on the irreversibility of the voltamogram in the sample with x = 15 mol% Co3O4; iii) the presence of cobalt ions in the Co+3 / Cooredox system (wave located at + 0.33 V) with a more intense effect on the irreversibility of the voltamogram in the sample with x = 8 mol% Co3O4; iv) the presence of the sulfate ion dimerization process in the redox process S2O8-2 / 2SO4-2 which appears located at 2 V, with a pronounced effect in the samples with x = 5 mol% Co3O4.

In conclusion, cyclic voltammetry measurements indicate clearly superior electrochemical performances of recycled and doped materials with higher cobalt double oxide (II and III) contents compared to undoped or those with a lower dopant content indicating a higher degree of irreversibility of redox processes. Doping with a suitable cobalt double oxide content (II and III) removes the passivation phenomenon of the electrode and the evolution reactions of hydrogen and the intensity of the residual current increases in the range 0 and 2 V. The lower degree of irreversibility of the cyclic voltammogram of the electrode material with a higher dopant level, respectively x = 10 mol% Co3O4 recommends it as suitable as an electrode for rechargeable batteries, ie when discharging the battery it can be recharged by the electrolysis process - charging reverse current using a generator.

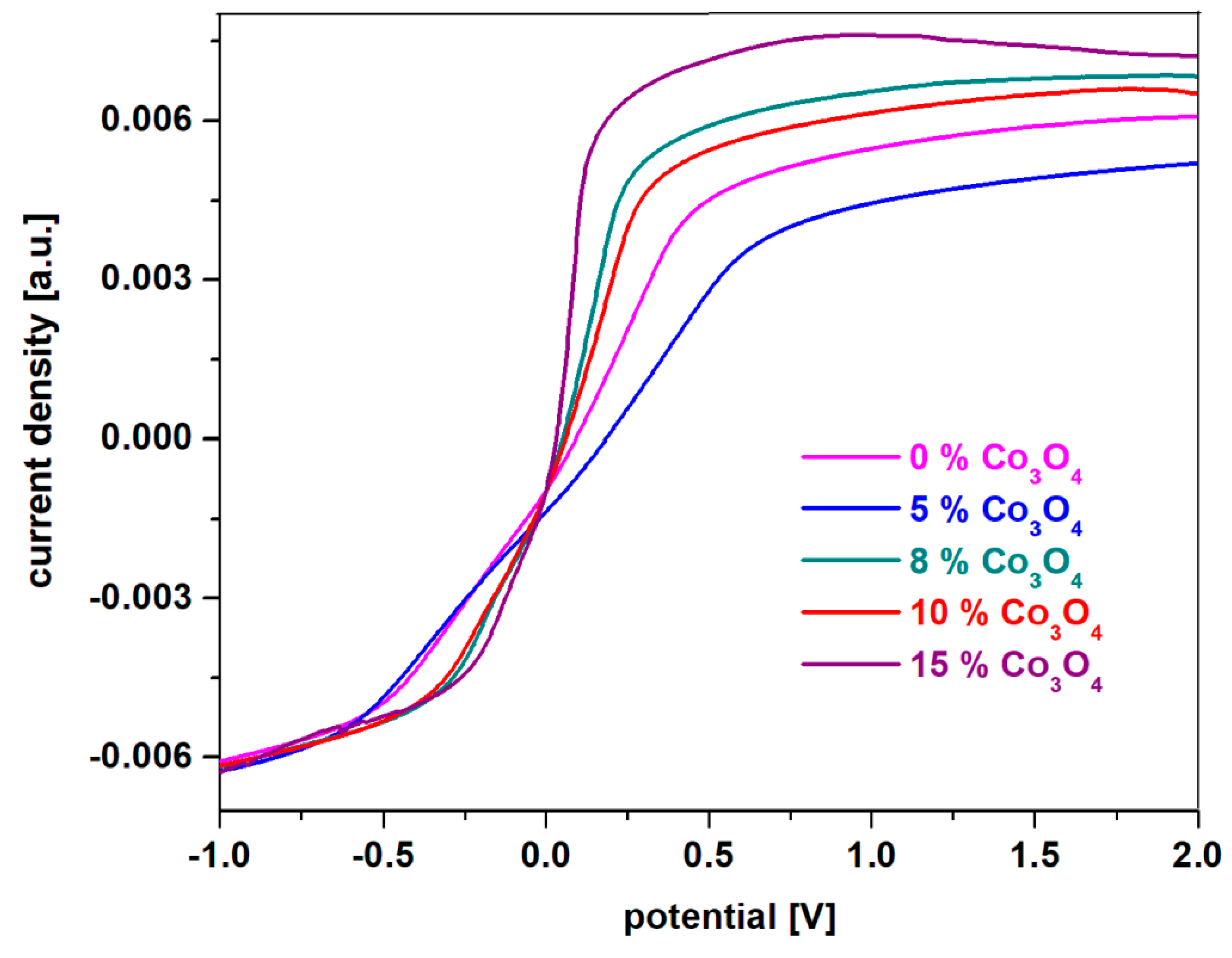

From the experimental data for voltammetry measurements with linear scanning, the appearance of the oxidation prime in the studied recycled system can be highlighted comparatively. The higher the current density of the main oxidation peak, the more suitable the electrode is for battery applications.

Linear scanning voltammograms of prepared electrode materials having the composition xCo

3O

4·(100-x)[4PbO

2·Pb],

x = 0, 1, 5, 8, 10, 15, 25 mol% Co

3O

4 in solution of sulfuric acid concentration 38 %, after scanning a cycle and having a scanning rate of 10 mV/s are shown in

Figure 6. A simple inspection of linear scanning voltamograms indicates that the current density is increased by doping with double cobalt oxide. Maximum current density for the first oxidation peak is obtained for samples with

x ≥ 15 mol% Co

3O

4, which is why it is recommended for applications as an electrode for batteries.

The sample with x = 10 mol% Co3O4, although it has a slightly lower current density than its analogues with a higher dopant content, is preferable for rechargeable batteries. Thus, the incorporation of a content of 10 mol% of double cobalt oxide in the host matrix will produce an improvement of the reversibility of the cyclic voltamogram and an increase of the number of charge-discharge processes of the battery. The new electrodes, recycled from the anodic and cathodic plates from a car battery with a high degree of wear and sulfation were optimized with a suitable content of double cobalt oxide by the melt queching method for applications to batteries as anode.

In conclusion, the paper proposes an eco-innovative and efficient method for recycling electrodes from a car battery with a high degree of wear and doping them with a suitable content of metal oxides in view of using the products obtained as new types of electrodes for batteries. The recycling method is more environmentally friendly, energy saving and offers an efficient desulphatization of the spent plates from car batteries. The results of various investigative techniques demonstrate the significant improvement of the conductive and electrochemical properties of the recycled electrode material in the composition of which high concentration nickel (II) oxide or cobalt (II, III) oxide was added. These performances are due to the presence of nickel or cobalt ions in different oxidation states, which have a drastic but beneficial effect in changing the structure of the recycled material. Recycled and doped electrodes with a higher content of metal oxides can be reused as new energy sources in batteries.

Conclusions

The systems in the xNiO·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] composition where x = 0, 1, 5, 10 mol % NiO and with the xCo3O4·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] composition where x = 0, 1, 5, 8, 10, 15, 25 mol% Co3O4 were synthesized by proposed recycling method. The raw materials used are: as the lead source - the active, disassembled mass of the anode from a used car battery, and as the lead dioxide source - the active mass of the cathode from a used car battery and NiO or Co3O4 powders from the laboratory. Recycled and nickel-doped or cobalt-doped materials were structurally characterized by XRD analysis, IR and ESR spectroscopy. The electrochemical performance of recycled and metal-ion-doped materials was highlighted by cyclic voltammetry measurements.

Analysis of XRD data indicates that the recycled and undoped sample contains as a majority phase the Pb2SO5 crystalline phase and traces of the Pb2O3 crystalline phase. The content of the Pb2SO5 crystalline phase decreases sharply with doping, so that it appears in traces only up to a content of x ≤ 5 mol% NiO and disappears for higher dopant levels. For samples with x > 5 mol% NiO, the content of PbO2 and PbO crystalline phases was increased.

The analysis of XRD data indicates that, the addition of high dopant contents up to 1 ≤ x ≤ 10 mol% Co3O4 in the structure of the glass ceramic, highlights the presence of three crystalline phases: 2PbO·PbSO4, PbO și PbO2. For samples with x ≤ 15 mol% Co3O4, a sudden decrease of the sulfated phase content is observed and new diffraction peaks corresponding to the PbO2 crystalline phase were appeared. For the total desulphatisation of spent plates from the car battery, a dopant content of at least 15 mol% Co3O4 must be taken into account.

The analysis of IR data indicates that by adding a suitable NiO content, x >5 mol% NiO, in the structure of the glass ceramic decreases the number of sulfate structural units and takes place the formation of a mixture of lead oxides, respectively Pb2O3, PbO2 and PbO crystalline phases, according to XRD data.

IR data show a decreasing trend in the intensity of the bands corresponding to sulfate ions by doping with high levels of Co3O4 in the structure of the glass ceramic host. Also, by increasing the dopant concentration there is the conversion of [PbO3] pyramidal units into [PbO4] tetrahedral units, which lead to the formation of Pb and PbO2 crystalline phases.

The EPR data indicate three resonance lines centered at g ~ 2, 2.2 and 8. The first two resonance lines are assigned to nickel ions in higher oxidation states, respectively Ni+2 ions (derived from the starting material, NiO) and ions Ni+3 (obtained during the synthesis by the oxidation process of Ni+2). The last resonance signal at g ~ 8 corresponds to nickel metal nanoparticles. The intensity of these resonance lines is dependent on the dopant level in the host matrix. Thus the first two resonance lines located at low values decrease by the addition of higher NiO contents in the structure of the glass ceramic, while the signal located at g ~ 8 increases by doping. This compositional evolution can be explained by considering a process of drastic reduction of nickel ions in oxidation states superior to metallic nickel. The presence of a higher nickel metal content in the samples with x > 5 mol% NiO explained the conductive properties of the electrode material, according to the cyclic voltammetry data.

The linewidth and the intensity of resonance lines from EPR spectra depend very strongly on the Co3O4 concentration. The variation in the g - values in the range of g ~ 2, 2.17, 4.22 and 7.8 can be ascribed to the interaction between varied Co+2 centers from the structure of recycled and cobalt-doped materials. The hyperfine structure centered at about g ~ 2 due to the octahedral geometry of the Co+2 ions with low spin remains almost unmodified when the intensity of the signal centered at about g ~ 4.22 decreases abruptly (due to hexa-coordinated Co+2 ions with high spin) for the samples with x = 1 and 5 mol% Co3O4. While the feature of the resonance lines situated at g ~ 2 and 2.11 broadens, changes shape and increases in intensity with increasing of cobalt content up to 15 mol% Co3O4. For samples with x = 10 and 15 mol% Co3O4, the major contribution of the Co+2 ions at EPR spectrum is due to their tetrahedral symmetries when for the sample with x = 25 mol% Co3O4 the six-coordinated sites were evidenced.

Analysis of cyclic votamograms after scanning one cycle and three cycles indicates that doping the recycled material with a suitable nickel oxide (II) content of 10 mol% NiO, respectively, has the following advantages: i) the evolutionary reactions of hydrogen are removed; ii) the passivation phenomenon of the electrode material is removed, through a more efficient dissolution of lead sulfate and the appearance of redox processes, which involve nickel ions which again increase the intensity of the residual current in the potential range 0 and 2 V. As disadvantages due to the presence of evolutionary reactions of oxygen and the process of dimerization of sulfate ions, cyclic voltammograms have a high degree of irreversibility.

The highest current density was obtained for the samples with x ≥ 8 mol % Co3O4, the voltamogram shows a high degree of irreversibility due to an irreversible hydrolysis processes. The best reversibility of the cyclic voltamogram was obtained for the sample with x = 10 mol% Co3O4, which is why we recommend it in applications as an electrode for renewable batteries, although it has a slightly lower current density than its analogues with a higher amount of dopant.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the ”Nucleu” project with the No. PN 19350101.

References

- Huang, K.; Liu, H.; Dong, H.; Li, M.; Ruan, J. A novel approach to recover lead oxide from spent lead acid batteries by desulfurization and crystallization in sodium hydroxide solution after sulfation. Resources, Conservation & Recycling 2021, 167, 105385. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zhu, X.; Yang, D.; Gao, L.; Liu, J.; Kumar, R.V.; Yang, J. Preparation characterization of nano-structured lead oxide from spent lead acid battery paste. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 203, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonmez, M.S.; Kumar, R.V. Leaching of waste battery paste components. Part 1: lead citrate synthesis from PbO and PbO2. Hydrometallurgy 2009, 95, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Qiu, K. Recovery of lead from lead paste in spent lead acid battery by hydrometallurgical desulfurization and vacuum thermal reduction. Waste Manage 2015, 40, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Shu, Y.; Chen, H. Recycling lead from spent lead pastes using oxalate and sodium oxalate and preparation of novel lead oxide for lead-acid batteries. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 94895–94902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, M.; Popa, A.; Rada, S.; Bot, A.; Culea, E. Recycled vanadium-doped materials as negative electrode of the lead acid battery. J. Solid State Electrochemistry 2019, 23, 2435–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, S.; Cuibus, D.; Vermesan, H.; Rada, M.; Culea, E. Structural and electrochemical properties of recycled active electrodes from spent lead acid battery and modified with different manganese dioxide contents. Electrochimica Acta 2018, 268, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, S.; Unguresan, M.; Rada, M.; Tudoran, C.; Wang, J.; Culea, E. Performance of the recycled and copper-doped materials from spent electrodes by XPS and Voltammetric characteristics. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 090548–090554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, X.G.; Zhuo, X.D.; Lin, Z.G. In-situ photoelectrochemical microscopic study of Pb/PbO/PbSO4 multi-interface system. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 1994, 367, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, S.; Rus, L.; Rada, M.; Culea, E.; Aldea, N.; Stan, S.; Suciu, R.C.; Bot, A. Synthesis, structure, optical and electrochemical properties of the lead sulfate-lead dioxide-lead glasses and vitroceramics. Solid State Ionics 2015, 274, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, S.; Zagrai, M.; Rada, M.; Culea, E.; Bolundut, L.; Unguresan, M.L.; Pica, M. Spectroscopic and electrochemical investigations of lead-lead dioxide glasses and vitroceramics with applications for rechargeable lead acid batteries. Ceramics International 2016, 42, 3921–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, S.; Unguresan, M.; Rada, M.; Cuibus, D.; Zhang, J.; Pengfei, A.; Suciu, R.; Bot, A.; Culea, E. Manganese-lead-lead dioxide glass ceramics as electrode materials. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, A3987–A3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, M.; Popa, A.; Rada, S.; Bot, A. Culea E Recycled and vanadium-doped materials as negative electrode of the lead acid battery. Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry 2019, 23, 2435–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrici, S.; Rada, S.; Culea, E.; Pop, L.; Popa, A.; Bot, A.; Macavei, S.; Pana, O.; David, L. Nickel-lead-borate glasses and vitroceramics with antiferromagnetic NiO and nickel-orthoborate crystalline phases. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2017, 471, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogomolova, L.D.; Krasilnikova, N.A.; Tarasova, VV. Electron paramagnetic resonance of silica glasses implanted with nickel. J. Non-Cryst.Solids 2003, 319, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottcher, R.; Langhammer, H.T.; Muller, T. Paramagnetic resonance study of nickel ions in hexagonal barium titanate. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2011, 23, 115903–11912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecht, H.G. Study of the Structure of Nickel in Soda-Boric Oxide Glasses. J. Chem. Phys. 1967, 47, 1840–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedhar, B.; Sumalatha, C.H.; Kojima, K. ESR optical absorption spectra of Ni(II) ions in lithium fluoroborate glasses. J. Mat. Sci. 1996, 31, 1445–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, R.V.S.S.N.; Yamauchi, J.; Chandrasekhar, A.V.; Reddy, Y.P. ; Rao PS Identification of chromium nickel sites in zinc phosphate glasses. J. Mol. Struc. 2005, 740, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardelean, I.; Ilonca, Gh.; Simon, V.; Jurcut, T.; Filip, S.; Hagau, T. Magnetic properties of nickel-strontium-borate oxide glasses. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 1997, 16, 200–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhecheva, E.; Stoyanova, R.; Alcantara, R.; Lavela, P.; Tirado, J.L. Cation order/disorder in lithium transition-metal oxides as insertion electrodes for lithium-ion batteries. Pure Appl. Chem. 2002, 74, 1885–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antholine, W.E.; Zhang, S.; Gonzales, J.; Newman, N. Better resolution of high-spin cobalt hyperfine at low frequency: co-doped Ba(Zn1/2Ta2/3)O3 as a model complex. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3532–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antholine, W.E. Resolved hyperfine at L-band for high-spin CoEDTA, a model for Co sites in proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Typek, J.; Guskos, N.; Zolnierkiewicz, G.; Sibera, D.; Narkiewicz, U. Magnetic resonance study of Co-doped ZnO nanomaterials: a case of high doping. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2017, 50, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

a): X-ray diffractograms of the recycled system and doped with nickel oxide (II) in the composition xNiO·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] where a) x = 0 mol% NiO synthesized at different temperatures; b) x = 0, 1, 5 and 10 mol % NiO prepared at 1050 oC and c) in the composition xCo3O4·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] where x = 0 - 20 mol % Co3O4.

Figure 1.

a): X-ray diffractograms of the recycled system and doped with nickel oxide (II) in the composition xNiO·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] where a) x = 0 mol% NiO synthesized at different temperatures; b) x = 0, 1, 5 and 10 mol % NiO prepared at 1050 oC and c) in the composition xCo3O4·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] where x = 0 - 20 mol % Co3O4.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of the a) xNiO·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] system where x = 0, 1, 5, 10 mol% NiO prepared at 1050 oC and x = 0 mol% NiO (prepared at 950 and 1000 oC) and b) xCo3O4·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] system where x = 0, 1, 5, 8, 10, 15, 25 mol% Co3O4 (prepared at 1050 oC) and x = 0 mol% Co3O4 (prepared at 850 oC).

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of the a) xNiO·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] system where x = 0, 1, 5, 10 mol% NiO prepared at 1050 oC and x = 0 mol% NiO (prepared at 950 and 1000 oC) and b) xCo3O4·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] system where x = 0, 1, 5, 8, 10, 15, 25 mol% Co3O4 (prepared at 1050 oC) and x = 0 mol% Co3O4 (prepared at 850 oC).

Figure 3.

EPR spectra of a) xNiO·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] system where x = 1, 5, 8, 10 mol% NiO b) xCo3O4·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb], x = 1, 5, 8, 10, 15, 25 mol% Co3O4.

Figure 3.

EPR spectra of a) xNiO·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] system where x = 1, 5, 8, 10 mol% NiO b) xCo3O4·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb], x = 1, 5, 8, 10, 15, 25 mol% Co3O4.

Figure 4.

Cyclic voltammograms of the system recycled and doped with metal oxide having the composition: a) xNiO·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] where x = 0, 1, 5, 8, 10 mol% NiO prepared at 1050 oC after scanning a cycle used as electrode material in an electrochemical cell using as electrolyte a 38% solution of sulfuric acid and simulating the processes from the electrode of a car battery; b) Cyclic voltamograms after scanning three cycles recorded in a solution of 38% sulfuric acid for recycled electrode materials having the composition xNiO·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] where x = 10 mol% NiO.

Figure 4.

Cyclic voltammograms of the system recycled and doped with metal oxide having the composition: a) xNiO·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] where x = 0, 1, 5, 8, 10 mol% NiO prepared at 1050 oC after scanning a cycle used as electrode material in an electrochemical cell using as electrolyte a 38% solution of sulfuric acid and simulating the processes from the electrode of a car battery; b) Cyclic voltamograms after scanning three cycles recorded in a solution of 38% sulfuric acid for recycled electrode materials having the composition xNiO·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] where x = 10 mol% NiO.

Figure 5.

Cyclic voltamograms after scanning a) a cycle and b) three cycles recorded in a solution of 38% sulfuric acid for recycled electrode materials having the composition xCo3O4·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb], x = 5, 8, 10, 15 mol % Co3O4.

Figure 5.

Cyclic voltamograms after scanning a) a cycle and b) three cycles recorded in a solution of 38% sulfuric acid for recycled electrode materials having the composition xCo3O4·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb], x = 5, 8, 10, 15 mol % Co3O4.

Figure 6.

Linear scanning voltammograms recorded in 38% sulfuric acid solution with a scanning rate of 10 mV/s for prepared electrode materials having the composition xCo3O4·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] where x = 0, 5, 8, 10, 15 mol% Co3O4.

Figure 6.

Linear scanning voltammograms recorded in 38% sulfuric acid solution with a scanning rate of 10 mV/s for prepared electrode materials having the composition xCo3O4·(100-x)[4PbO2·Pb] where x = 0, 5, 8, 10, 15 mol% Co3O4.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).