Submitted:

16 May 2023

Posted:

17 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

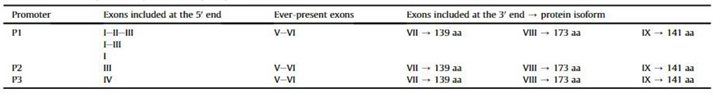

1. A Briefing Note about Parathyroid Hormone-Related Protein (PTHrP) Stucture and Function

2. Adipose Tissue: PTHrP-Related Signatures in Adipogenesis and Transdifferentiation

3. Bone and Dental Tissues: PTHrP-Related Signatures in Osteoblatogenesis, Osteoclastogenesis and Ossification

4. Cartilaginous tissue: PTHrP-related signatures in the repression of chondrocyte differentiation

5. Intestinal epithelium: PTHrP-related signatures in calcium uptake by enterocytes

6. Liver parenchyma: PTHrP-related signatures in the fibrotic reaction of hepatic stellate cells

7. Lung epithelium: PTHrP-related signatures in pulmonary surfactant production.

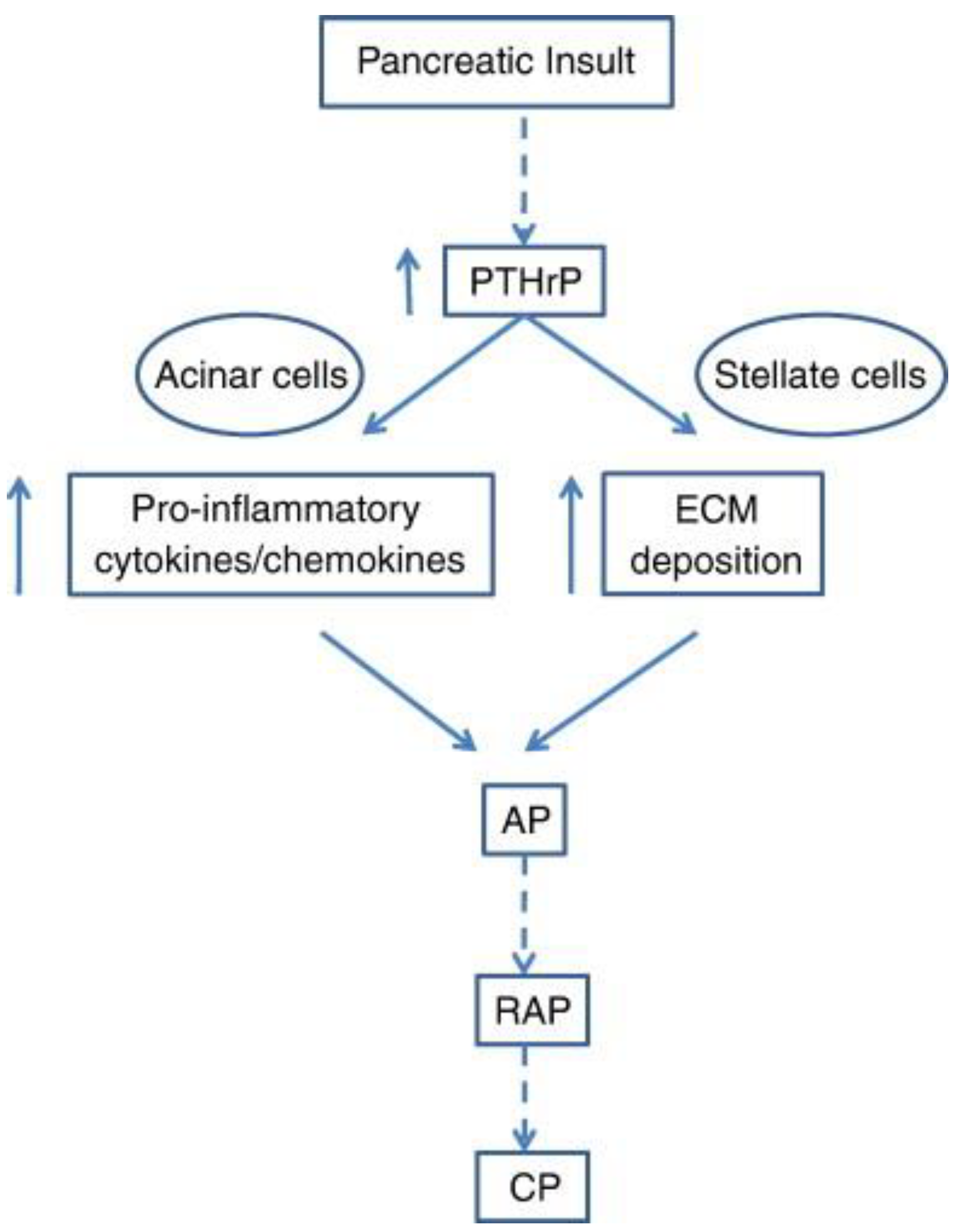

8. Exocrine and endocrine pancreas: PTHrP-related signatures in β cell biology and in the onset of pancreatitis

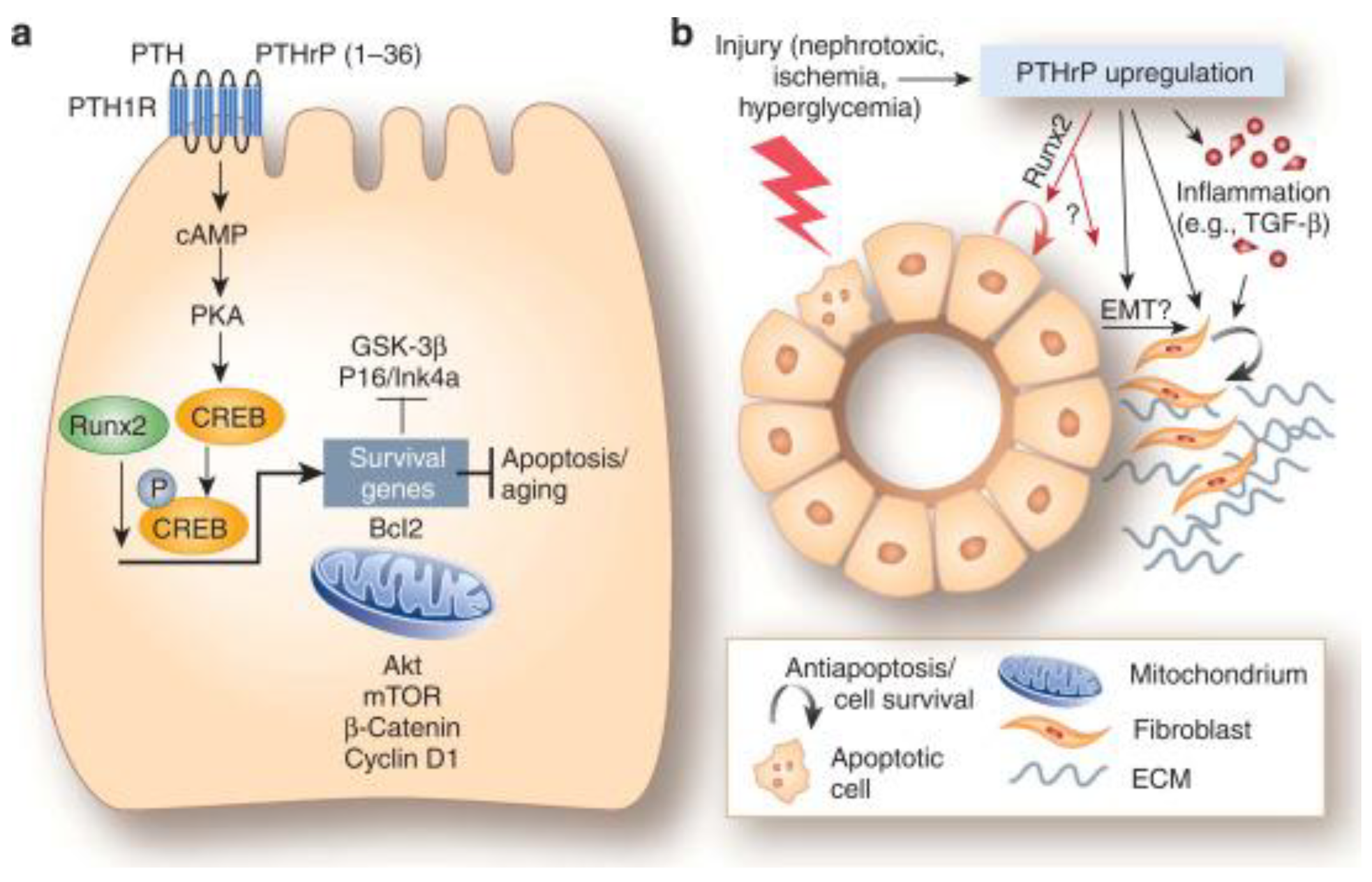

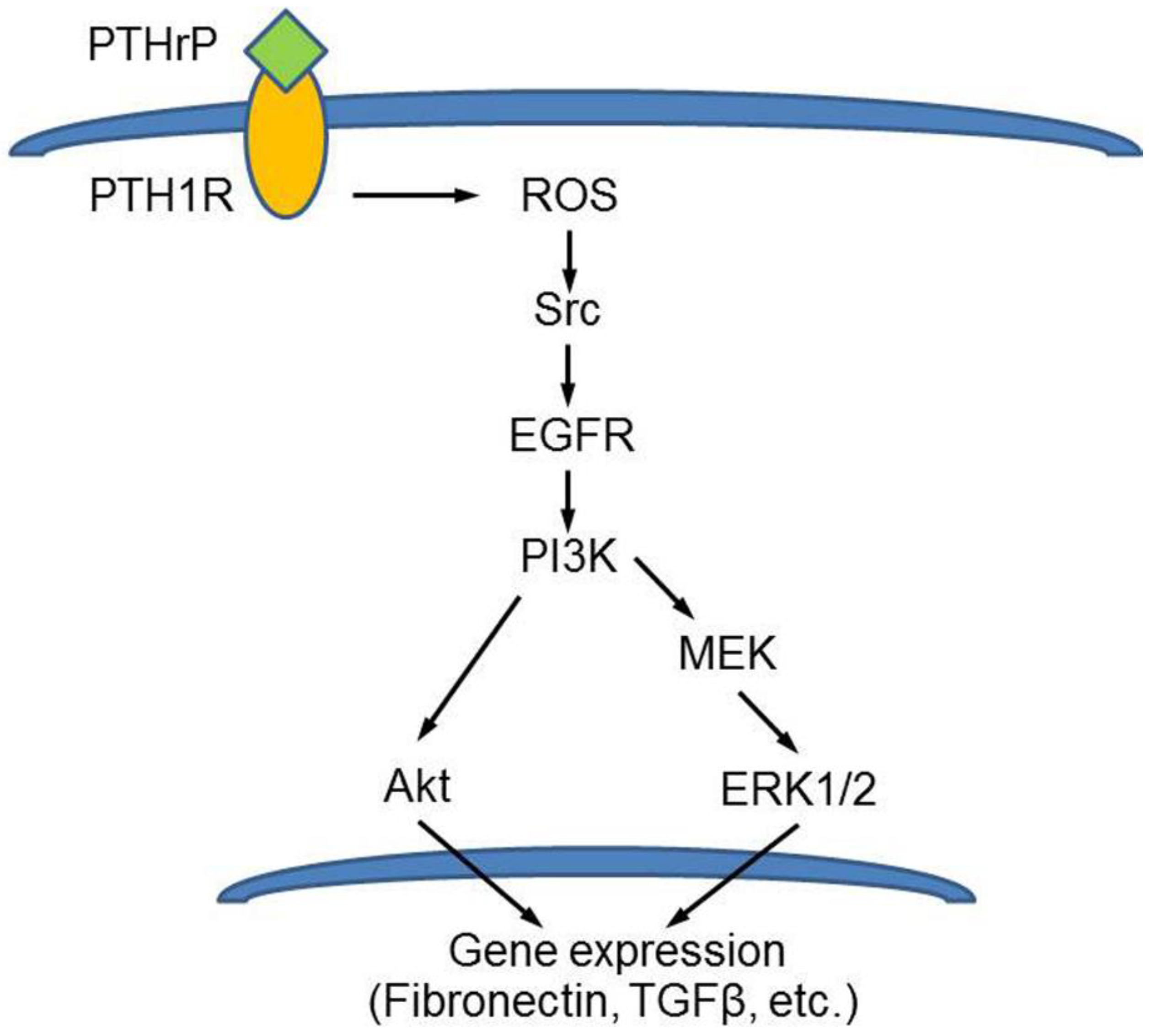

9. Renal parenchyma: PTHrP-related signatures in the promotion of kidney cell survival and in diabetes-related changes

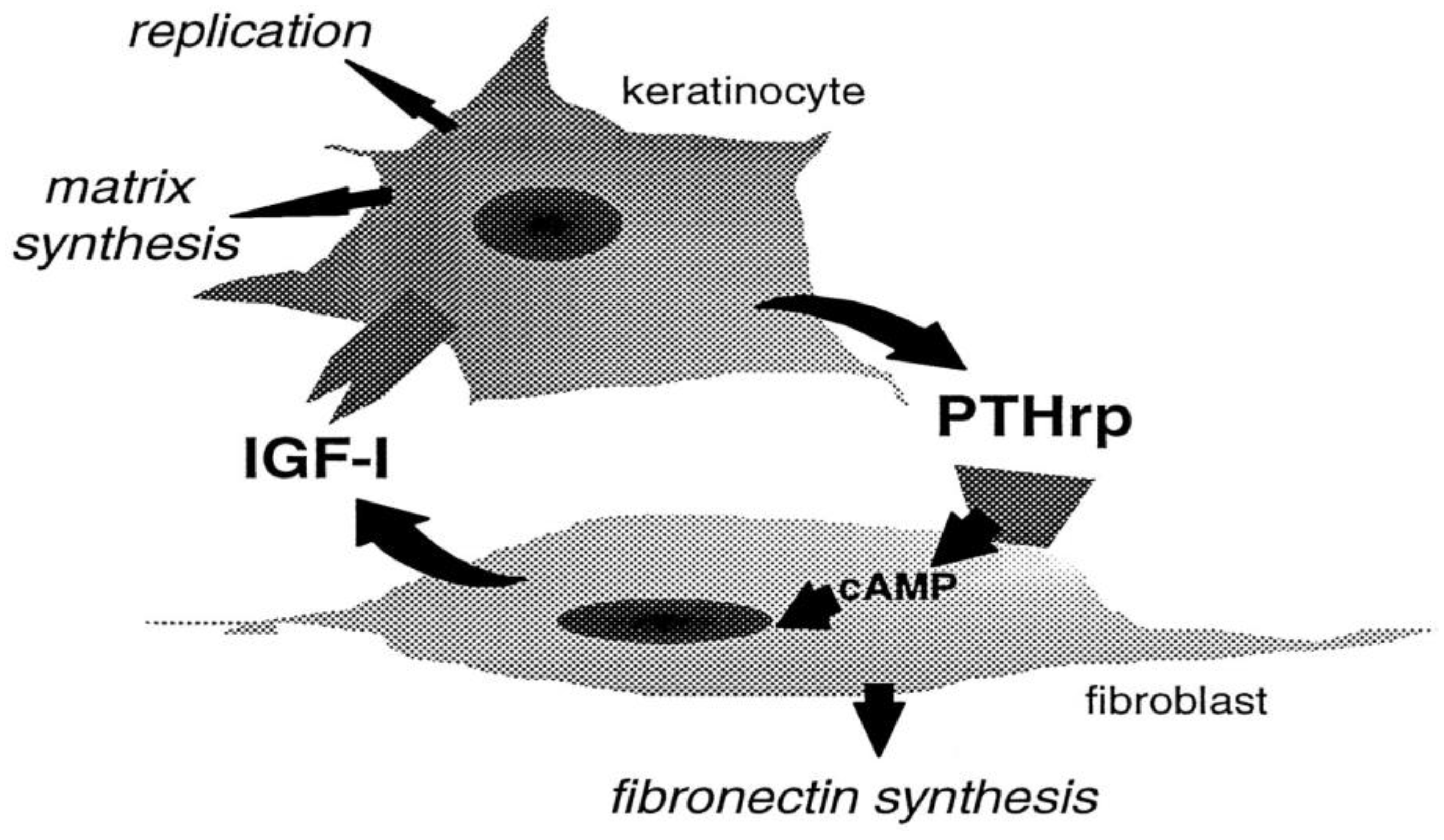

10. Skin: PTHrP-related signatures in keratinocyte development and anti-aging effect

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luparello, C. Parathyroid Hormone-Related Protein (PTHrP): A Key Regulator of Life/Death Decisions by Tumor Cells with Potential Clinical Applications. Cancers (Basel) 2011, 3, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, A.; Librizzi, M.; Naselli, F.; Caradonna, F.; Tobiasch, E.; Luparello, C. PTHrP in Differentiating Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Transcript Isoform Expression, Promoter Methylation, and Protein Accumulation. Biochimie 2013, 95, 1888–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

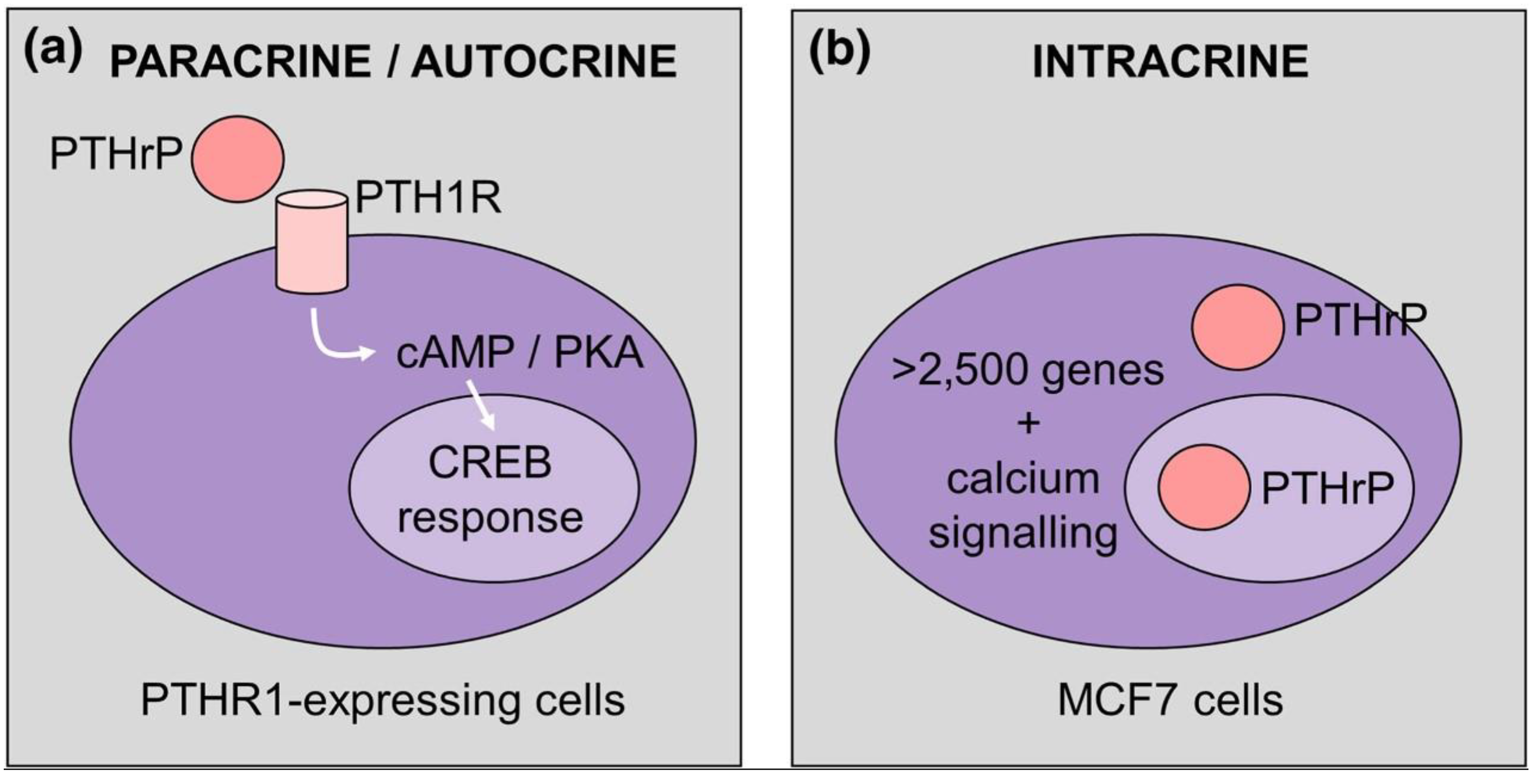

- Martin, T.J.; Johnson, R.W. Multiple actions of parathyroid hormone-related protein in breast cancer bone metastasis. Br J Pharmacol 2021, 178, 1923–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, T.J. PTH1R Actions on Bone Using the cAMP/Protein Kinase A Pathway. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 12, 833221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suva, L.J.; Friedman, P.A. Structural pharmacology of PTH and PTHrP. Vitam Horm 2022, 120, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luparello, C.; Librizzi, M. Parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP)-dependent modulation of gene expression signatures in cancer cells. Vitam Horm 2022, 120, 179–214. [Google Scholar]

- Lagathu, C.; Christodoulides, C.; Tan, C.Y.; Virtue, S.; Laudes, M.; Campbell, M.; Ishikawa, K.; Ortega, F.; Tinahones, F.J.; Fernández-Real, J.-M.; Orešič, M.; Sethi, J.K.; Vidal-Puig, A. Secreted Frizzled-Related Protein 1 Regulates Adipose Tissue Expansion and Is Dysregulated in Severe Obesity. Int J Obes 2010, 34, 1695–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca-Rodríguez, M.M.; el Bekay, R.; Garrido-Sanchez, L.; Gómez-Serrano, M.; Coin-Aragüez, L.; Oliva-Olivera, W.; Lhamyani, S.; Clemente-Postigo, M.; García-Santos, E.; de Luna Diaz, R.; Yubero-Serrano, E.M.; Fernández Real, J.M.; Peral, B.; Tinahones, F.J. Parathyroid Hormone-Related Protein, Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Adipogenic Capacity and Healthy Obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015, 100, E826–E835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, G.K.; Miao, D.; Deckelbaum, R.; Bolivar, I.; Karaplis, A.; Goltzman, D. Parathyroid Hormone-Related Peptide Interacts with Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2 to Increase Osteoblastogenesis and Decrease Adipogenesis in Pluripotent C3H10T½ Mesenchymal Cells. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 5511–5520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cheng, Q.; Wang, Y.; Leung, P.S.; Mak, K.K. Hedgehog Signaling in Bone Regulates Whole-Body Energy Metabolism through a Bone–Adipose Endocrine Relay Mediated by PTHrP and Adiponectin. Cell Death Differ 2017, 24, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, T.P.; Berg, A.H.; Obici, S.; Scherer, P.E.; Rossetti, L. Endogenous Glucose Production Is Inhibited by the Adipose-Derived Protein Acrp30. J Clin Invest 2001, 108, 1875–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamauchi, T.; Kamon, J.; Ito, Y.; Tsuchida, A.; Yokomizo, T.; Kita, S.; Sugiyama, T.; Miyagishi, M.; Hara, K.; Tsunoda, M.; Murakami, K.; Ohteki, T.; Uchida, S.; Takekawa, S.; Waki, H.; Tsuno, N.H.; Shibata, Y.; Terauchi, Y.; Froguel, P.; Tobe, K.; Koyasu, S.; Taira, K.; Kitamura, T.; Shimizu, T.; Nagai, R.; Kadowaki, T. Cloning of Adiponectin Receptors That Mediate Antidiabetic Metabolic Effects. Nature 2003, 423, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kir, S.; White, J.P.; Kleiner, S.; Kazak, L.; Cohen, P.; Baracos, V.E.; Spiegelman, B.M. Tumour-Derived PTH-Related Protein Triggers Adipose Tissue Browning and Cancer Cachexia. Nature 2014, 513, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jesus, L.A.; Carvalho, S.D.; Ribeiro, M.O.; Schneider, M.; Kim, S.-W.; Harney, J.W.; Larsen, P.R.; Bianco, A.C. The Type 2 Iodothyronine Deiodinase Is Essential for Adaptive Thermogenesis in Brown Adipose Tissue. J Clin Invest 2001, 108, 1379–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, B.; Qincao, L.; He, S.; Liao, Y.; Shi, J.; Xie, F.; Diao, N.; Bai, L. Parathyroid Hormone-Related Protein Prevents High-Fat-Diet-Induced Obesity, Hepatic Steatosis and Insulin Resistance in Mice. Endocr J 2022, 69, EJ20–EJ0728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tezze, C.; Romanello, V.; Sandri, M. FGF21 as Modulator of Metabolism in Health and Disease. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Miguel, F.; Martinez-Fernandez, P.; Guillen, C.; Valin, A.; Rodrigo, A.; Martinez, M.E.; Esbrit. P. Parathyroid hormone-related protein (107-139) stimulates interleukin-6 expression in human osteoblastic cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 1999, 10, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esbrit, P.; Alvarez-Arroyo, M.V.; DE Miguel, F.; Martin, O.; Martinez, M.E.; Caramelo, C. C-terminal parathyroid hormone-related protein increases vascular endothelial growth factor in human osteoblastic cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000, 11, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, V.; de Gortázar, A.R.; Ardura, J.A.; Andrade-Zapata, I.; Alvarez-Arroyo, M.V.; Esbrit, P. Parathyroid hormone-related protein (107-139) increases human osteoblastic cell survival by activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2. J Cell Physiol 2008, 217, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, D.; Sánchez-Salcedo, S.; Portal-Núñez, S.; Vila, M.; López-Herradón, A.; Ardura, J.A.; Mulero, F.; Gómez-Barrena, E.; Vallet-Regí, M.; Esbrit, P. Parathyroid hormone-related protein (107-111) improves the bone regeneration potential of gelatin-glutaraldehyde biopolymer-coated hydroxyapatite. Acta Biomater 2014, 10, 3307–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niida, A.; Hiroko, T.; Kasai, M.; Furukawa, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Sugano, S.; Akiyama, T. DKK1, a negative regulator of Wnt signaling, is a target of the β-catenin/TCF pathway. Oncogene 2004, 23, 8520–8526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semënov, M.; Tamai, K.; He, X. SOST is a ligand for LRP5/LRP6 and a Wnt signaling inhibitor. J Biol Chem 2005, 80, 26770–26775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutkovskiy, A.; Stensløkken, K.O.; Vaage, I.J. Osteoblast Differentiation at a Glance. Med Sci Monit Basic Res 2016, 22, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

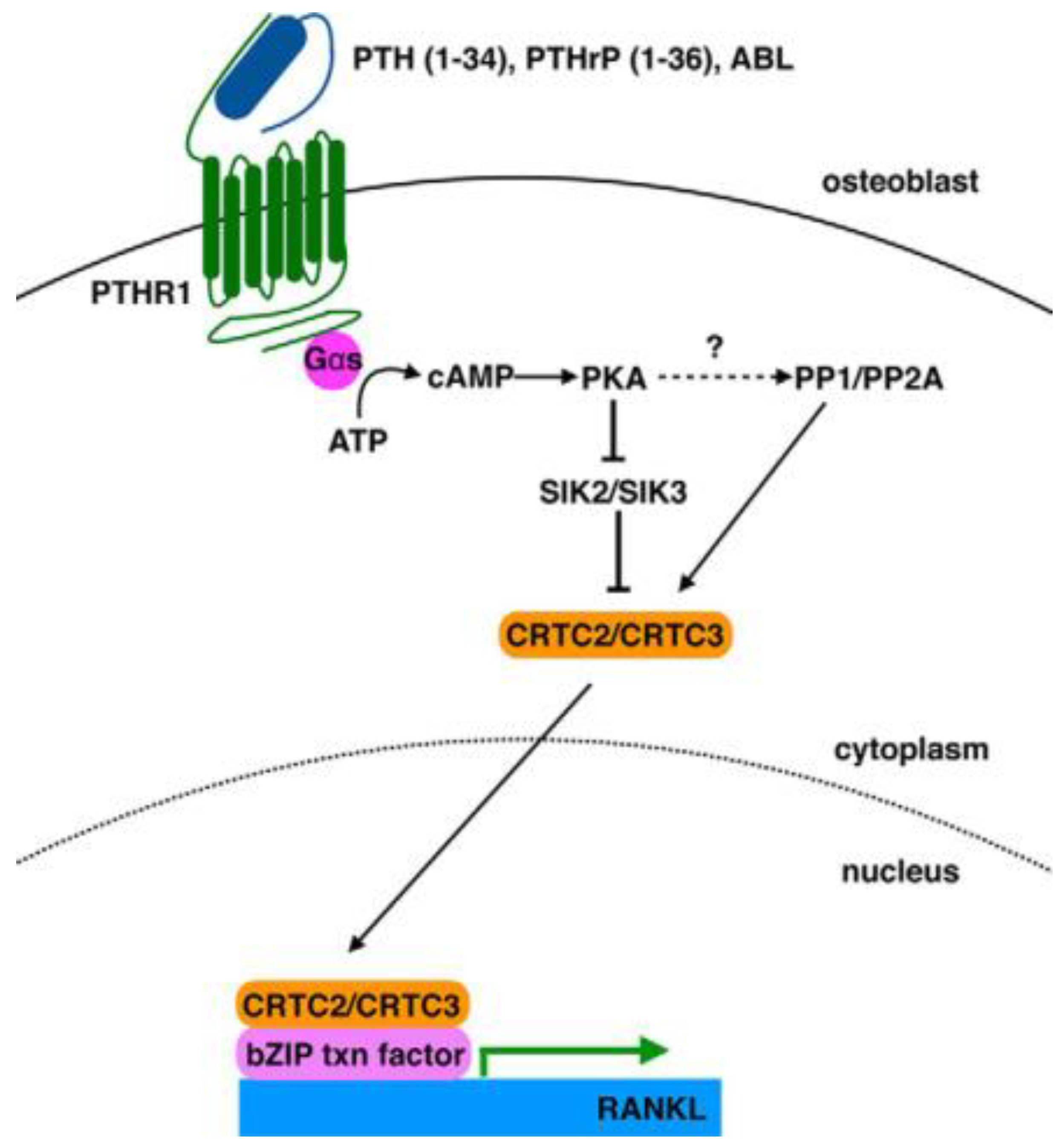

- Fukushima, H.; Jimi, E.; Kajiya, H.; Motokawa, W.; Okabe, K. Parathyroid-hormone-related protein induces expression of receptor activator of NF-κB ligand in human periodontal ligament cells via a cAMP/protein kinase A-independent pathway. J Dent Res 2005, 84, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Bi, Y.; Li, X.; Shu, Y.; Chen, X.; Jin, Z.; Ge, C. Regulation of OPG and RANKL expressed by human dental follicle cells in osteoclastogenesis. Cell Tissue Res 2015, 362, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, K.K.; Bi, Y.; Wan, C.; Chuang, P.T.; Clemens, T.; Young, M.; Yang, Y. Hedgehog signaling in mature osteoblasts regulates bone formation and resorption by controlling PTHrP and RANKL expression. Dev Cell 2008, 14, 674–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricarte, F.R.; Le Henaff, C.; Kolupaeva, V.G.; Gardella, T.J.; Partridge, N.C. Parathyroid hormone (1-34) and its analogs differentially modulate osteoblastic Rankl expression via PKA/SIK2/SIK3 and PP1/PP2A-CRTC3 signaling. J Biol Chem 2018, 293, 20200–20213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elango, J.; Rahman, S.U.; Henrotin, Y.; de Val, J.E.M.S.; Bao, B.; Wang, S.; Li, B.; Wu, W. Parathyroid Hormone-Related Protein (PTHrP) Accelerates Soluble RANKL Signals for Downregulation of Osteogenesis of Bone Mesenchymal Stem Cells. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Minashima, T.; McCarthy, E.F.; Winkles, J.A.; Kirsch, T. Progressive ankylosis protein (ANK) in osteoblasts and osteoclasts controls bone formation and bone remodeling. J Bone Miner Res 2010, 25, 1771–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, S.A.; Yee, J.A. Continuous and intermittent exposure of neonatal rat calvarial cells to PTHrP (1-36) inhibits bone nodule mineralization in vitro by downregulating bone sialoprotein expression via the cAMP signaling pathway. F1000Res. 2013, 2, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, X.; Wang, C.; Ding, C.; Lin, H.; Liu, A.; Wang, L.; Cao, Y. Exogenous PTHrP Repairs the Damaged Fracture Healing of PTHrP+/− Mice and Accelerates Fracture Healing of Wild Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

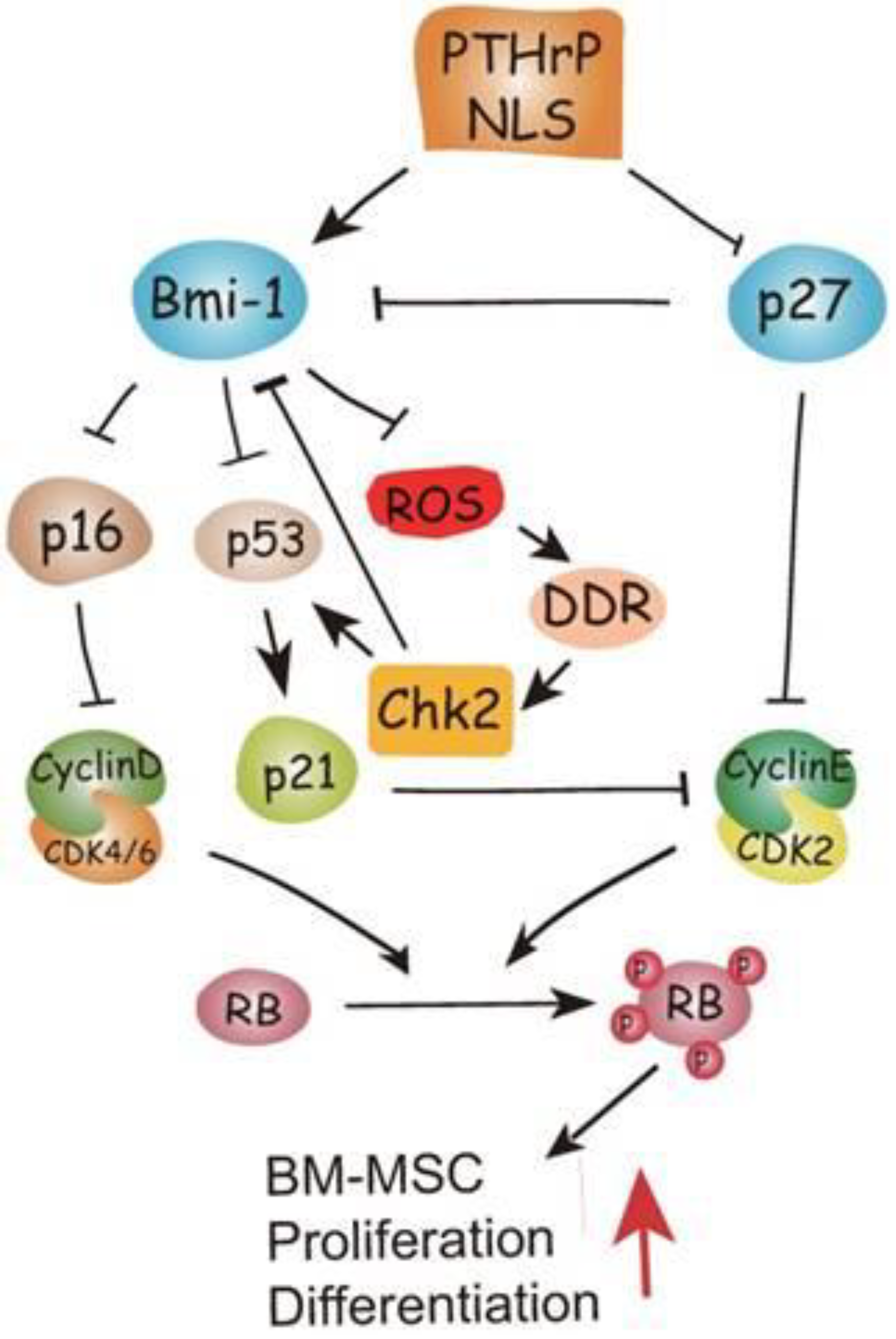

- Zhu, M.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R.; Karaplis, A.; Goltzman, D.; Miao, D. The p27 Pathway Modulates the Regulation of Skeletal Growth and Osteoblastic Bone Formation by Parathyroid Hormone-Related Peptide. J Bone Miner Res 2015, 30, 1969–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, G.; Gu, Z.; Sun, H.; Karaplis, A.; Goltzman, D.; Miao, D. DNA damage checkpoint pathway modulates the regulation of skeletal growth and osteoblastic bone formation by parathyroid hormone-related peptide. Int J Biol Sci 2018, 14, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

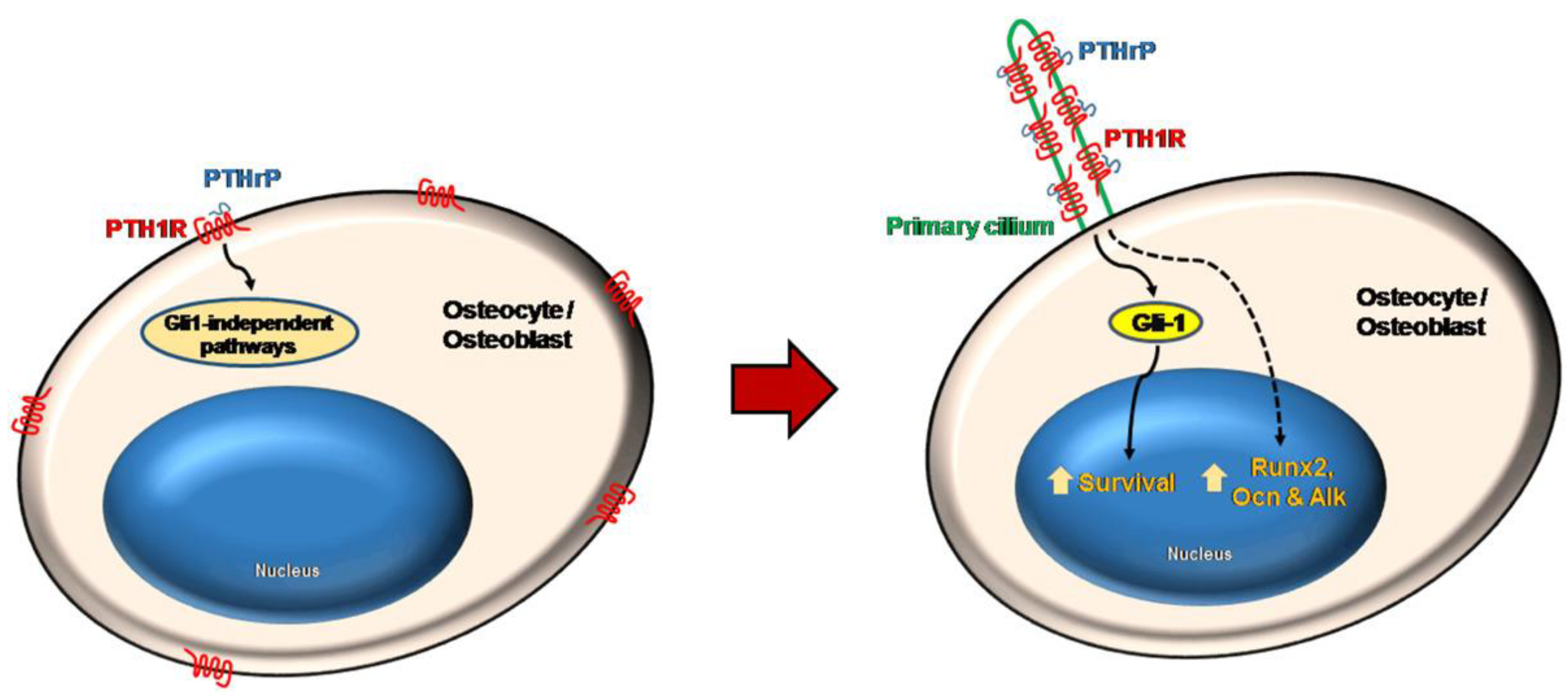

- Martín-Guerrero, E.; Tirado-Cabrera, I.; Buendía, I.; Alonso, V.; Gortázar, A.R.; Ardura, J.A. Primary cilia mediate parathyroid hormone receptor type 1 osteogenic actions in osteocytes and osteoblasts via Gli activation. J Cell Physiol 2020, 235, 7356–7369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platas, J.; Guillén, M.I.; Gomar, F.; Castejón, M.A.; Esbrit, P.; Alcaraz, M.J. Anti-senescence and Anti-inflammatory Effects of the C-terminal Moiety of PTHrP Peptides in OA Osteoblasts. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2017, 72, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardura, J.A.; Portal-Núñez, S.; Castelbón-Calvo, I.; Martínez de Toda, I.; De la Fuente, M.; Esbrit, P. Parathyroid Hormone-Related Protein Protects Osteoblastic Cells From Oxidative Stress by Activation of MKP1 Phosphatase. J Cell Physiol 2017, 232, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onan, D.; Allan, E.H.; Quinn, J.M.; Gooi, J.H.; Pompolo, S.; Sims, N.A.; Gillespie, M.T.; Martin, T.J. The chemokine Cxcl1 is a novel target gene of parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related protein in committed osteoblasts. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 2244–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portal-Núñez, S.; Lozano, D.; de Castro, L.F.; de Gortázar, A.R.; Nogués, X.; Esbrit, P. Alterations of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway and its target genes for the N- and C-terminal domains of parathyroid hormone-related protein in bone from diabetic mice. FEBS Lett 2010, 584, 3095–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maycas, M.; McAndrews, K.A.; Sato, A.Y.; Pellegrini, G.G.; Brown, D.M.; Allen, M.R.; Plotkin, L.I.; Gortazar, A.R.; Esbrit, P.; Bellido, T. PTHrP-Derived Peptides Restore Bone Mass and Strength in Diabetic Mice: Additive Effect of Mechanical Loading. J Bone Miner Res 2017, 32, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, A.; Takagi, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Hase, N.; Sugiyama, H.; Yamana, K.; Kobayashi, T. Abaloparatide Exerts Bone Anabolic Effects with Less Stimulation of Bone Resorption-Related Factors: A Comparison with Teriparatide. Calcif Tissue Int 2018, 103, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amizuka, N.; Warshawsky, H.; Henderson, J.E.; Goltzman, D.; Karaplis, A.C. Parathyroid hormone-related peptide-depleted mice show abnormal epiphyseal cartilage development and altered endochondral bone formation. J Cell Biol 1994, 126, 1611–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, D.E.; Liu, X. Expression of bone morphogenetic protein-6 messenger RNA in bovine growth plate chondrocytes of different size. J Bone Miner Res 1995, 10, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanske, B.; Karaplis, A.C.; Lee, K.; Luz, A.; Vortkamp, A.; Pirro, A.; Karperien, M.; Defize, L.H.; Ho, C.; Mulligan, R.C.; Abou-Samra, A.B.; Jüppner, H.; Segre, G.V.; Kronenberg, H.M. PTH/PTHrP receptor in early development and Indian hedgehog-regulated bone growth. Science 1996, 273, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, H.; Akiyama, H.; Shigeno, C.; Nakamura, T. Parathyroid hormone-related peptide inhibits the expression of bone morphogenetic protein-4 mRNA through a cyclic AMP/protein kinase A pathway in mouse clonal chondrogenic EC cells, ATDC5. Biochim Biophys Acta 2000, 1497, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.F.; Dong, Y.; Ionescu, A.M.; Rosier, R.N.; Zuscik, M.J.; Schwarz, E.M.; O’Keefe, R.J.; Drissi, H. Parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) inhibits Runx2 expression through the PKA signaling pathway. Exp Cell Res 2004, 299, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhemyakina, E.; Cohen, T.; Yao, T.P.; Lassar, A.B. Parathyroid hormone-related peptide represses chondrocyte hypertrophy through a protein phosphatase 2A/histone deacetylase 4/MEF2 pathway. Mol Cell Biol 2009, 29, 5751–5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Wang, S.T.; Duan, C.C.; Li, D.D.; Tian, X.C.; Wang, Q.Y.; Yue, Z.P. Effects of PTHrP on chondrocytes of sika deer antler. Cell Tissue Res 2013, 354, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.T.; Gao, Y.J.; Duan, C.C.; Li, D.D.; Tian, X.C.; Zhang, Q.L.; Guo, B.; Yue, Z.P. Effects of PTHrP on expression of MMP9 and MMP13 in sika deer antler chondrocytes. Cell Biol Int 2013, 37, 1300–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelosi, M.; Lazzarano, S.; Thoms, B.L.; Murphy, C.L. Parathyroid hormone-related protein is induced by hypoxia and promotes expression of the differentiated phenotype of human articular chondrocytes. Clin Sci (Lond) 2013, 125, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browe, D.C.; Coleman, C.M.; Barry, F.P.; Elliman, S.J. Hypoxia Activates the PTHrP-MEF2C Pathway to Attenuate Hypertrophy in Mesenchymal Stem Cell Derived Cartilage. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 13274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Aulmann, A.; Dexheimer, V.; Grossner, T.; Richter, W. Intermittent PTHrP(1-34) exposure augments chondrogenesis and reduces hypertrophy of mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cells Dev 2014, 23, 2513–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaplis, A.C.; Luz, A.; Glowacki, J.; Bronson, R.T.; Tybulewicz, V.L.; Kronenberg, H.M.; Mulligan, R.C. Lethal skeletal dysplasia from targeted disruption of the parathyroid hormone-related peptide gene. Genes Dev 1994, 8, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimori, S.; Lai, F.; Shiraishi, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Kozhemyakina, E.; Yao, T.P.; Lassar, A.B.; Kronenberg, H.M. PTHrP targets HDAC4 and HDAC5 to repress chondrocyte hypertrophy. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e97903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.X.; Nemere, I.; Norman, A.W. A parathyroid-related peptide induces transcaltachia (the rapid, hormonal stimulation of intestinal Ca2+ transport). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1992, 186, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, D.; Nemere, I. Vectorial Transcellular Calcium Transport in Intestine: Integration of Current Models. J Biomed Biotechnol 2002, 2, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beggs, M.R.; Alexander, R.T. Intestinal absorption and renal reabsorption of calcium throughout postnatal development. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2017, 242, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Shao, G.; Lu, Y.; Xue, M.; Liang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Bai, L. Parathyroid Hormone-Related Protein (1-40) Enhances Calcium Uptake in Rat Enterocytes Through PTHR1 Receptor and Protein Kinase Cα/β Signaling. Cell Physiol Biochem 2018, 51, 1695–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Xue, M.; Liu, C.; Xie, F.; Bai, L. Parathyroid Hormone-Like Hormone Induces Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition of Intestinal Epithelial Cells by Activating the Runt-Related Transcription Factor 2. Am J Pathol 2018, 188, 1374–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, B. The Molecular Mechanisms of Liver Fibrosis and Its Potential Therapy in Application. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 12572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.F.; Liu, C.P.; Li, L.X.; Xue, M.M.; Xie, F.; Guo, Y.; Bai, L. Activated effects of parathyroid hormone-related protein on human hepatic stellate cells. PLoS One 2013, 8, e76517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardi, C.; Arezzini, B.; Fortino, V.; Comporti, M. Effect of free iron on collagen synthesis, cell proliferation and MMP-2 expression in rat hepatic stellate cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2002, 64, 1139–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Tang, J.; Diao, N.; Liao, Y.; Shi, J.; Xu, X.; Xie, F.; Bai, L. Parathyroid hormone-related protein activates HSCs via hedgehog signalling during liver fibrosis development. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol 2019, 47, 1984–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torday, J.S.; Rehan, V.K. The evolutionary continuum from lung development to homeostasis and repair. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007, 292, L608–L611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torday, J.S.; Rehan, V.K. Stretch-stimulated surfactant synthesis is coordinated by the paracrine actions of PTHrP and leptin. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002, 283, L130–L135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torday, J.; Rehan, V. Neutral lipid trafficking regulates alveolar type II cell surfactant phospholipid and surfactant protein expression. Exp Lung Res 2011, 37, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oruqaj, L.; Forst, S.; Schreckenberg, R.; Inserte, J.; Poncelas, M.; Bañeras, J.; Garcia-Dorado, D.; Rohrbach, S.; Schlüter, K.D. Effect of high fat diet on pulmonary expression of parathyroid hormone-related protein and its downstream targets. Heliyon 2016, 2, e00182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehan, V.K.; Sakurai, R.; Wang, Y.; Santos, J.; Huynh, K.; Torday, J.S. Reversal of nicotine-induced alveolar lipofibroblast-to-myofibroblast transdifferentiation by stimulants of parathyroid hormone-related protein signaling. Lung 2007, 185, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, Y.; Zhang, B.; Okajima, F.; Izumi, T.; Takeuchi, T. PTHrP increases pancreatic β-cell-specific functions in well-differentiated cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2001, 182, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, Y.; Kameya, T.; Aizama, T.; Izumi, T.; Takeuchi, T. Proprotein-Processing Endoprotease Furin and its Substrate Parathyroid Hormone-Related Protein are Coexpressed in Insulinoma Cells. Endocr Pathol 2000, 11, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthalu Kondegowda, N.; Joshi-Gokhale, S.; Harb, G.; Williams, K.; Zhang, X.Y.; Takane, K.K.; Zhang, P.; Scott, D.K.; Stewart, A.F.; Garcia-Ocaña, A.; Vasavada, R.C. Parathyroid hormone-related protein enhances human ß-cell proliferation and function with associated induction of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 and cyclin E expression. Diabetes 2010, 59, 3131–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Abanquah, D.; Joshi-Gokhale, S.; Otero, A.; Lin, H.; Guthalu, N.K.; Zhang, X.; Mozar, A.; Bisello, A.; Stewart, A.F.; Garcia-Ocaña, A.; Vasavada, R.C. Systemic and acute administration of parathyroid hormone-related peptide(1-36) stimulates endogenous beta cell proliferation while preserving function in adult mice. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 2867–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, V.; Kim, S.O.; Aronson, J.F.; Chao, C.; Hellmich, M.R.; Falzon, M. Role of parathyroid hormone-related protein in the pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrogenic response associated with acute pancreatitis. Regul Pept 2012, 175, 49–60, Erratum in: Regul Pept 2014, 192-193, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadr-Azodi, O.; Oskarsson, V.; Discacciati, A.; Videhult, P.; Askling, J.; Ekbom, A. Pancreatic Cancer Following Acute Pancreatitis: A Population-based Matched Cohort Study. Am J Gastroenterol 2018, 113, 1711–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastellini, C.; Han, S.; Bhatia, V.; Cao, Y.; Liu, K.; Gao, X.; Ko, T.C.; Greeley, G.H. Jr.; Falzon, M. Induction of chronic pancreatitis by pancreatic duct ligation activates BMP2, apelin, and PTHrP expression in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2015, 309, G554–G565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Cao, Y.; Yang, W.; Duan, C.; Aronson, J.F.; Rastellini, C.; Chao, C.; Hellmich, M.R.; Ko, T.C. BMP2 inhibits TGF-β-induced pancreatic stellate cell activation and extracellular matrix formation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2013, 304, G804–G813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Englander, E.W.; Gomez, G.A.; Aronson, J.F.; Rastellini, C.; Garofalo, R.P.; Kolli, D.; Quertermous, T.; Kundu, R.; Greeley, G.H. Jr. Pancreatitis activates pancreatic apelin-APJ axis in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2013, 305, G139–G150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrell, N.W.; Archer, S.L.; Defelice, A.; Evans, S.; Fiszman, M.; Martin, T.; Saulnier, M.; Rabinovitch, M.; Schermuly, R.; Stewart, D.; Truebel, H.; Walker, G.; Stenmark, K.R. Anticipated classes of new medications and molecular targets for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ 2013, 3, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoumassoun, L.E.; Russo, C.; Denizeau, F.; Averill-Bates, D.; Henderson, Dr.J.E. Parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) inhibits mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis through CK2. J Cell Physiol 2007, 212, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, I.M.; Hanif, I.M.; Shazib, M.A.; Ahmad, K.A.; Pervaiz, S. Casein Kinase II: an attractive target for anti-cancer drug design. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2010, 42, 1602–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardura, J.A.; Rayego-Mateos, S.; Rámila, D.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Esbrit, P. Parathyroid Hormone–Related Protein Promotes Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010, 21, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, K.; Li, Y.; Zhou, H.; Hu, X.; Chen, Y.; He, R.; Luo, R.; Zhou, R.; Bi, D.; Jin, H. Haemophilus parasuis Infection Disrupts Adherens Junctions and Initializes EMT Dependent on Canonical Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2018, 8, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardura, J.A.; Sanz, A.B.; Ortiz, A.; Esbrit, P. Parathyroid hormone–related protein protects renal tubuloepithelial cells from apoptosis by activating transcription factor Runx2. Kidney Int 2013, 83, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramann, R.; Schneider, R.K. Parathyroid hormone-related protein and regulation of cell survival in the kidney. Kidney Int 2013, 83, 777–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochane, M.; Raison, D.; Coquard, C.; Béraud, C.; Bethry, A.; Danilin, S.; Massfelder, T.; Barthelmebs, M. Parathyroid hormone-related protein modulates inflammation in mouse mesangial cells and blunts apoptosis by enhancing COX-2 expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2018, 314, C242–C253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danilin, S.; Sourbier, C.; Thomas, L.; Rothhut, S.; Lindner, V.; Helwig, J.J.; Jacqmin, D.; Lang, H.; Massfelder, T. von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene-dependent mRNA stabilization of the survival factor parathyroid hormone-related protein in human renal cell carcinoma by the RNA-binding protein HuR. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 387–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltschmidt, B.; Linker, R.A.; Deng, J.; Kaltschmidt, C. Cyclooxygenase-2 is a neuronal target gene of NF-kappaB. BMC Mol Biol 2002, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.E.; Vranes, D.; Youssef, S.; Stacker, S.A.; Cox, A.J.; Rizkalla, B.; Casley, D.J.; Bach, L.A.; Kelly, D.J.; Gilbert, R.E. Increased renal expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor VEGFR-2 in experimental diabetes. Diabetes 1999, 48, 2229–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, K.D. Angiotensin II and its receptors in the diabetic kidney. Am J Kidney Dis 2000, 36, 449–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, A.; López-Luna, P.; Ortega, A.; Romero, M.; Guitiérrez-Tarrés, M.A.; Arribas, I.; Alvarez, M.J.; Esbrit, P.; Bosch, R.J. The parathyroid hormone-related protein system and diabetic nephropathy outcome in streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Kidney Int 2006, 69, 2171–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esbrit, P.; Santos, S.; Ortega, A.; Fernández-Agulló, T.; Vélez, E.; Troya, S.; Garrido, P.; Peña, A.; Bover, J.; Bosch, R.J. Parathyroid hormone-related protein as a renal regulating factor. From vessels to glomeruli and tubular epithelium. Am J Nephrol 2001, 21, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, M.; Ortega, A.; Izquierdo, A.; López-Luna, P.; Bosch, R.J. Parathyroid hormone-related protein induces hypertrophy in podocytes via TGF-beta(1) and p27(Kip1): implications for diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010, 25, 2447–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, A.; Romero, M.; Izquierdo, A.; Troyano, N.; Arce, Y.; Ardura, J.A.; Arenas, M.I.; Bover, J.; Esbrit, P.; Bosch, R.J. Parathyroid hormone-related protein is a hypertrophy factor for human mesangial cells: Implications for diabetic nephropathy. J Cell Physiol 2012, 227, 1980–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.M.; Dai, J.J.; Zhu, R.; Peng, F.F.; Wu, S.Z.; Yu, H.; Krepinsky, J.C.; Zhang, B.F. Parathyroid hormone-related protein induces fibronectin up-regulation in rat mesangial cells through reactive oxygen species/Src/EGFR signaling. Biosci Rep 2019, 39, BSR20182293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Póvoa, G.; Diniz, L.M. Growth Hormone System: skin interactions. An Bras Dermatol 2011, 86, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.H.; Ji, C.; Casinghino, S.; McCarthy, T.L.; Centrella, M. Parathyroid hormone-related protein enhances insulin-like growth factor-I expression by fetal rat dermal fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 1997, 272, 23498–23502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blomme, E.A.; Sugimoto, Y.; Lin, Y.C.; Capen, C.C.; Rosol, T.J. Parathyroid hormone-related protein is a positive regulator of keratinocyte growth factor expression by normal dermal fibroblasts. Mol Cell Endocrinol 1999, 152, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, D.; Su, H.; He, B.; Gao, J.; Xia, Q.; Zhu, M.; Gu, Z.; Goltzman, D.; Karaplis, A.C. Severe growth retardation and early lethality in mice lacking the nuclear localization sequence and C-terminus of PTH-related protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008, 105, 20309–20314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvat, B.L.; Wang, A.; Seth, P.; Jetten, A.M. Up-regulation of p27Kip1, p21WAF1/Cip1 and p16Ink4a is associated with, but not sufficient for, induction of squamous differentiation. J Cell Sci 1998, 111, 1185–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Chen, G.; Lu, N.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, S.; Karaplis, A.; Goltzman, D.; Miao, D. Deficiency of the parathyroid hormone-related peptide nuclear localization and carboxyl terminal sequences leads to premature skin ageing partially mediated by the downregulation of p27. Exp Dermatol 2015, 24, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).