Submitted:

15 May 2023

Posted:

16 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

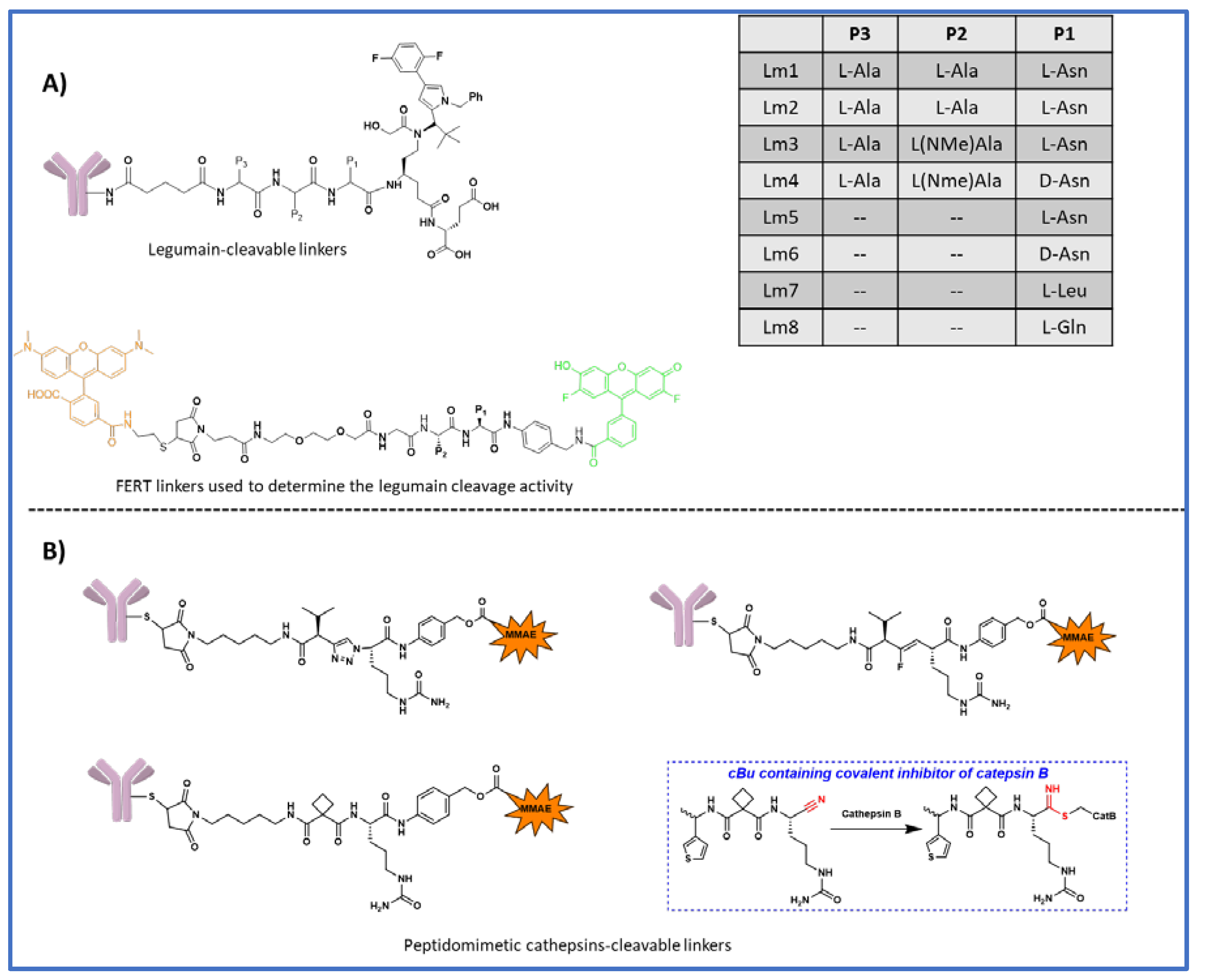

Keywords:

1. Introduction

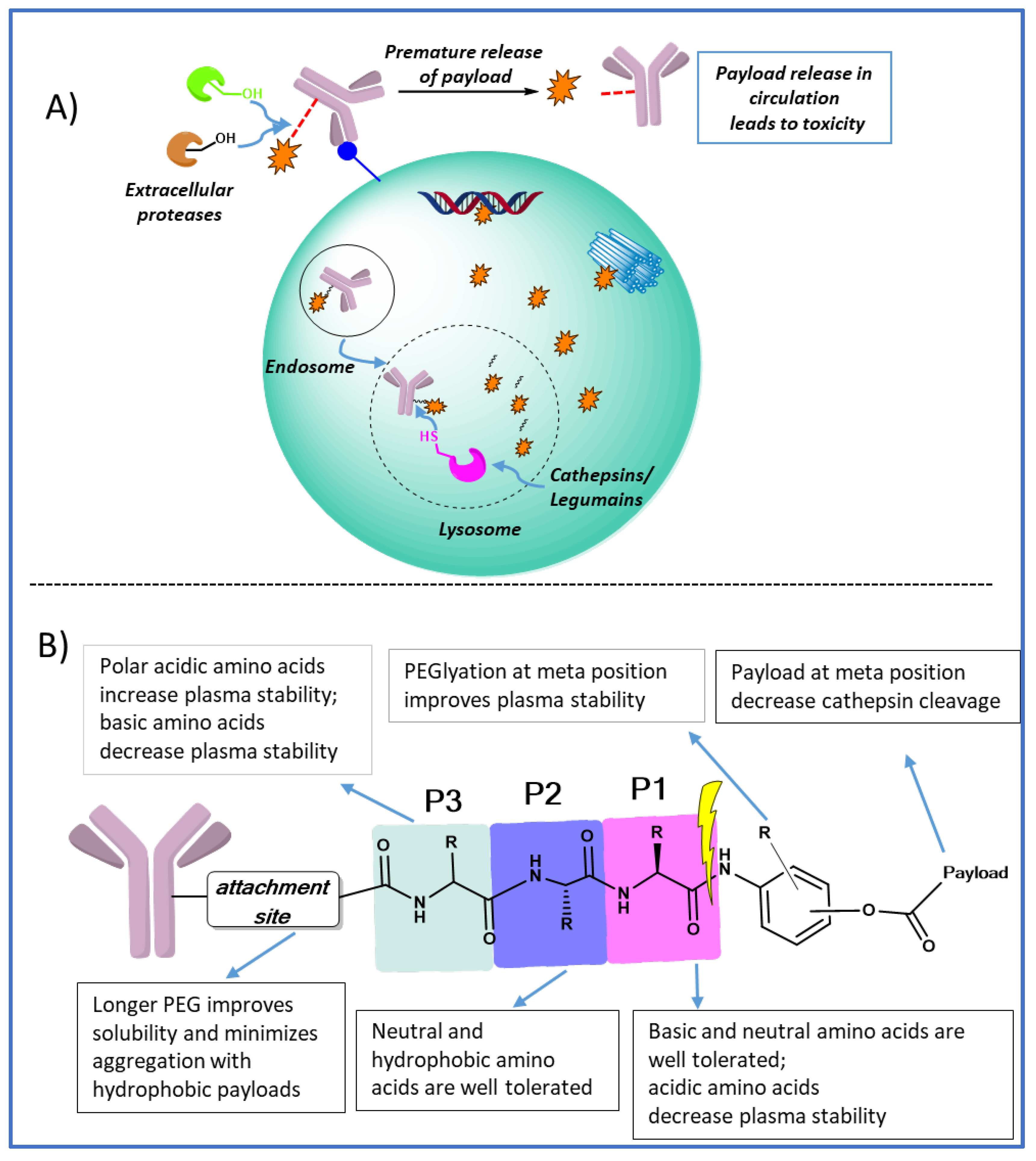

2. Polar acidic residues at P3 position increases plasma stability

3. Polar basic residues at P1 improves lysosomal cleavage

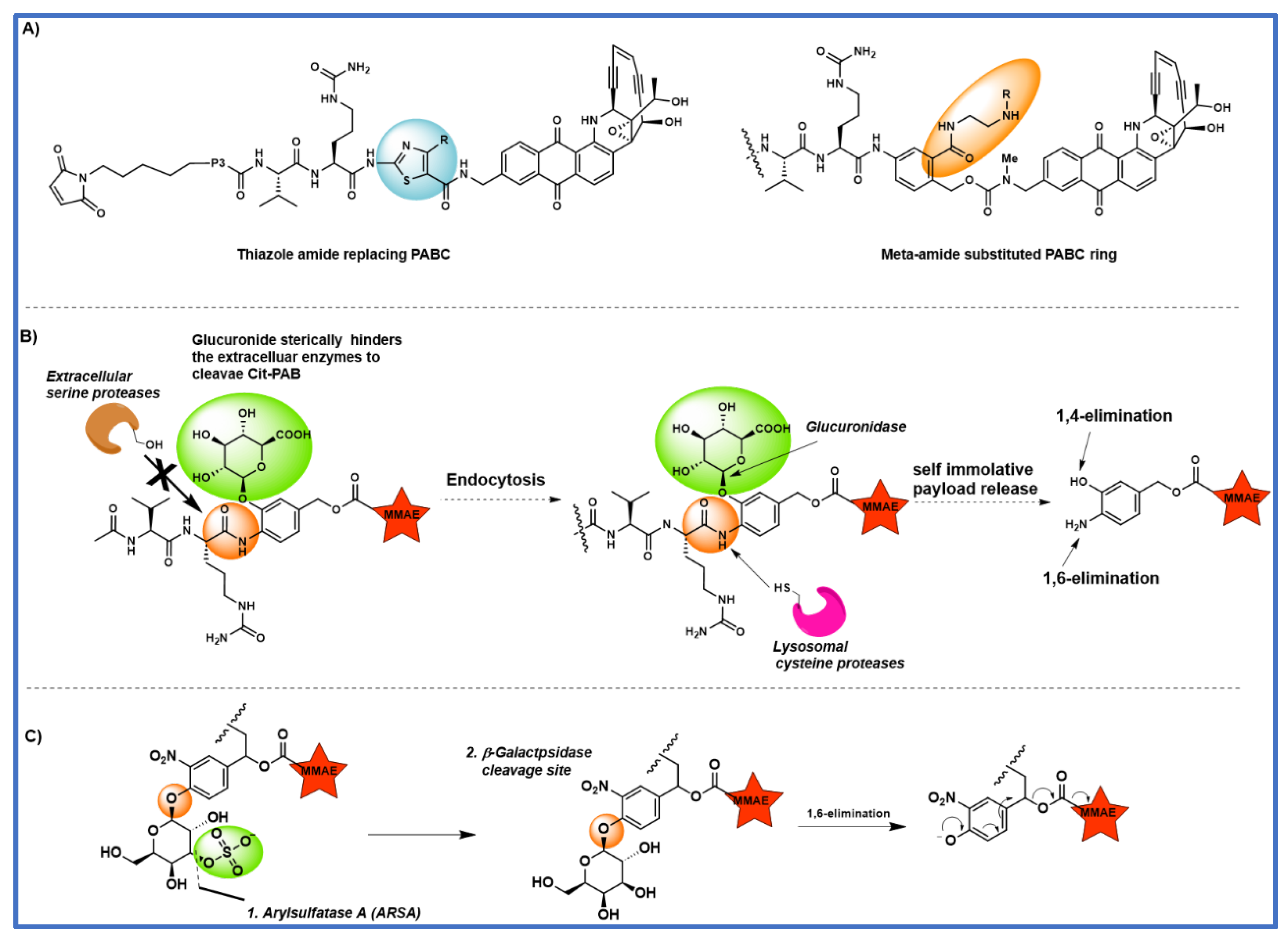

4. The effect of substitution on the PABC benzene ring

5. Tandem cleavable linkers

6. Legumain cleavable linkers

7. Peptidomimetic substitution at P2 position

8. Conclusion and outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fu, Z.; Li, S.; Han, S.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Y. Antibody drug conjugate: the “biological missile” for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, J. T.; Harris, P. W.; Brimble, M. A.; Kavianinia, I. An insight into FDA approved antibody-drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Molecules 2021, 26, 5847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, R. Drawing lessons from the clinical development of antibody-drug conjugates. Drug Discov Today Technol 2018, 30, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chau, C. H.; Steeg, P. S.; Figg, W. D. Antibody–drug conjugates for cancer. Lancet 2019, 394, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.; Goetsch, L.; Dumontet, C.; Corvaïa, N. Strategies and challenges for the next generation of antibody–drug conjugates. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2017, 16, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, B. Antibody-drug conjugates for cancer: poised to deliver? Highlighted by Genentech's recent US regulatory submission for trastuzumab-DM1, antibody-drug conjugation technology could be heading for the mainstream in anticancer drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010, 9, 665–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, P. J.; Senter, P. D. Antibody-drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Cancer J 2008, 14, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaghy, H. Effects of antibody, drug and linker on the preclinical and clinical toxicities of antibody-drug conjugates. MAbs 2016, 8, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, J. Z.; Modi, S.; Chandarlapaty, S. Unlocking the potential of antibody–drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2021, 18, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doronina, S. O.; Toki, B. E.; Torgov, M. Y.; Mendelsohn, B. A.; Cerveny, C. G.; Chace, D. F.; DeBlanc, R. L.; Gearing, R. P. ’ Bovee, T. D.; Siegall, C. B.; Francisco, J. A.; Wahl, A. F.; Meyer D. L.; Senter P. D. Development of potent monoclonal antibody auristatin conjugates for cancer therapy. Nat Biotech 2003, 2003 21, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doronina, S. O.; Bovee, T. D.; Meyer, D. W.; Miyamoto, J. B.; Anderson, M. E.; Morris-Tilden, C. A.; Senter, P. D. Novel peptide linkers for highly potent antibody− auristatin conjugate. Bioconjug Chem 2008, 19, 1960–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salomon, P. L.; Reid, E. E.; Archer, K. E.; Harris, L.; Maloney, E. K.; Wilhelm, A. J.; Miller, M. L.; Chari, R. V.; Keating, T. A.; Singh, R. Optimizing Lysosomal Activation of Antibody–Drug Conjugates (ADCs) by Incorporation of Novel Cleavable Dipeptide Linkers. Mol Pharm 2019, 16, 4817–4825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorywalska, M.; Dushin, R.; Moine, L.; Farias, S. E.; Zhou, D.; Navaratnam, T.; Lui, V.; Hasa-Moreno, A.; Casas, M. G.; Tran, T.-T. Molecular basis of valine-citrulline-pabc linker instability in site-specific ADCs and its mitigation by linker designmolecular basis of VC-PABC linker instability. Mol Cancer Ther 2016, 15, 958–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahalingaiah, P. K.; Ciurlionis, R.; Durbin, K. R.; Yeager, R. L.; Philip, B. K.; Bawa, B.; Mantena, S. R.; Enright, B. P.; Liguori, M. J.; Van Vleet, T. R. Potential mechanisms of target-independent uptake and toxicity of antibody-drug conjugates. Pharmacol Ther 2019, 200, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younes, A.; Gopal, A. K.; Smith, S. E.; Ansell, S. M.; Rosenblatt, J. D.; Savage, K. J.; Ramchandren, R.; Bartlett, N. L.; Cheson, B. D.; De Vos, S. Results of a pivotal phase II study of brentuximab vedotin for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2012, 30, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Gulesserian, S.; Malinao, M. C.; Ganesan, S. K.; Song, J.; Chang, M. S.; Williams, M. M.; Zeng, Z.; Mattie, M.; Mendelsohn, B. A. A potential mechanism for ADC-induced neutropenia: role of neutrophils in their own demisemechanism for ADC-induced neutropenia. Mol Cancer Ther 2017, 16, 1866–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bargh, J. D.; Isidro-Llobet, A.; Parker, J. S.; Spring, D. R. Cleavable linkers in antibody–drug conjugates. Chem Soc Rev 2019, 48, 4361–4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poreba, M. Protease-activated prodrugs: strategies, challenges, and future directions. Febs j 2020, 287, 1936–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Xiao, D.; Xie, F.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Fan, S.; Zhou, X.; Li, S. Antibody–drug conjugates: Recent advances in linker chemistry. Acta Pharm Sin B 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckertish, C. M.; Kayser, V. Advances and limitations of antibody drug conjugates for cancer. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheyi, R.; de la Torre, B. G.; Albericio, F. Linkers: An assurance for controlled delivery of antibody-drug conjugate. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anami, Y.; Yamazaki, C. M.; Xiong, W.; Gui, X.; Zhang, N.; An, Z.; Tsuchikama, K. Glutamic acid–valine–citrulline linkers ensure stability and efficacy of antibody–drug conjugates in mice. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, Y. B.; Chowdari, N. S.; Cheng, H.; Iwuagwu, C. I.; King, H. D.; Kotapati, S.; Passmore, D.; Rampulla, R.; Mathur, A.; Vite, G. Chemical modification of linkers provides stable linker–payloads for the generation of antibody–drug conjugates. ACS Med Chem Lett 2020, 11, 2190–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Gunzner-Toste, J.; Yao, H.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Xu, Z.; Chen, J.; Wai, J.; Nonomiya, J.; Tsai, S. P. Discovery of peptidomimetic antibody–drug conjugate linkers with enhanced protease specificity. J Med Chem 2018, 61, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poudel, Y. B.; Rao, C.; Kotapati, S.; Deshpande, M.; Thevanayagam, L.; Pan, C.; Cardarelli, J.; Chowdari, N.; Kaspady, M.; Samikannu, R. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of phenol-linked uncialamycin antibody-drug conjugates. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2020, 30, 126782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuprakov, S.; Ogunkoya, A. O.; Barfield, R. M.; Bauzon, M.; Hickle, C.; Kim, Y. C.; Yeo, D.; Zhang, F.; Rabuka, D.; Drake, P. M. Tandem-cleavage linkers improve the in vivo stability and tolerability of antibody–drug conjugates. Bioconjug Chem 2021, 32, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, P.; Kudirka, R.; Albers, A. E.; Barfield, R. M.; de Hart, G. W.; Drake, P. M.; Jones, L. C.; Rabuka, D. Hydrazino-pictet-spengler ligation as a biocompatible method for the generation of stable protein conjugates. Bioconjug Chem 2013, 24, 846–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabuka, D.; Rush, J. S.; Dehart, G. W.; Wu, P.; Bertozzi, C. R. Site-specific chemical protein conjugation using genetically encoded aldehyde tags. Nat Protoc 2012, 7, 1052–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargh, J. D.; Walsh, S. J.; Ashman, N.; Isidro-Llobet, A.; Carroll, J. S.; Spring, D. R. A dual-enzyme cleavable linker for antibody–drug conjugates. Chem Commun 2021, 57, 3457–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, S. Legumain: Asparaginyl endopeptidase. Methods Enzymol 1994, 244, 604–615. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. M.; Dando, P. M.; Stevens, R. A. E.; Fortunato, M.; Barrett, A. J. Cloning and expression of mouse legumain, a lysosomal endopeptidase. Biochem J 1998, 335, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.-M.; Dando, P. M.; Rawlings, N. D.; Brown, M. A.; Young, N. E.; Stevens, R. A.; Hewitt, E.; Watts, C.; Barrett, A. J. Cloning, isolation, and characterization of mammalian legumain, an asparaginyl endopeptidase. J Biol Chem 1997, 272, 8090–8098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Sun, C.; Huang, H.; Janda, K.; Edgington, T. Overexpression of legumain in tumors is significant for invasion/metastasis and a candidate enzymatic target for prodrug therapy. Cancer Res 2003, 63, 2957–2964. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Luo, Y.; Sun, C.; Liu, Y.; Kuo, P.; Varga, J.; Xiang, R.; Reisfeld, R.; Janda, K. D.; Edgington, T. S. Targeting cell-impermeable prodrug activation to tumor microenvironment eradicates multiple drug-resistant neoplasms. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 970–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajjuri, K. M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, C.; Sinha, S. C. The legumain protease-activated auristatin prodrugs suppress tumor growth and metastasis without toxicity. ChemMedChem 2011, 6, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Li, J.; Tanaka, K.; Majumder, U.; Milinichik, A. Z.; Verdi, A. C.; Maddage, C. J.; Rybinski, K. A.; Fernando, S.; Fernando, D. MORAb-202, an antibody–drug conjugate utilizing humanized anti-human frα farletuzumab and the microtubule-targeting agent eribulin, has potent antitumor activityMORAb-202, an anti-FRA ADC utilizing eribulin as payload. Mol Cancer Ther 2018, 17, 2665–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerchen, H.-G.; Stelte-Ludwig, B.; Sommer, A.; Berndt, S.; Rebstock, A.-S.; Johannes, S.; Mahlert, C.; Greven, S.; Dietz, L.; Jörißen, H. Tailored linker chemistries for the efficient and selective activation of ADCs with KSPi payloads. Bioconjug Chem 2020, 31, 1893–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerchen, H. G.; Wittrock, S.; Stelte-Ludwig, B.; Sommer, A.; Berndt, S.; Griebenow, N.; Rebstock, A. S.; Johannes, S.; Cancho-Grande, Y.; Mahlert, C. Antibody–drug conjugates with pyrrole-based KSP inhibitors as the payload class. Angew Chem Int Ed 2018, 57, 15243–15247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpov, A. S.; Nieto-Oberhuber, C. M.; Abrams, T.; Beng-Louka, E.; Blanco, E.; Chamoin, S.; Chene, P.; Dacquignies, I.; Daniel, D.; Dillon, M. P.; Doumampouom-Metoul, L.; Drosos, N.; Fedoseev, P.; Furegati, M.; Granda, B.; Grotzfeld, R. M.; Hess Clark, S.; Joly, E.; Jones, D.; Lacaud-Baumlin, M.; Lagasse-Guerro, S.; Lorenzana, E. G.; Mallet, W.; Martyniuk, P.; Marzinzik, A. L.; Mesrouze, Y.; Nocito, S.; Oei, Y.; Perruccio, F.; Piizzi, G.; Richard, E.; Rudewicz, P. J.; Schindler, P.; Velay, M.; Venstrom, K.; Wang, P.; Zurini, M.; Lafrance, M. Discovery of potent and selective antibody–drug conjugates with Eg5 inhibitors through linker and payload optimization. ACS Med Chem Lett 2019, 10, 1674–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. T.; Vitro, C. N.; Fang, S.; Benjamin, S. R.; Tumey, L. N. Enzyme-agnostic lysosomal screen identifies new legumain-cleavable ADC linkers. Bioconjug Chem 2021, 32, 842–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S.No | ADC | Linker system | Cleavage mechanism | Payload | Company |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) |

4-(4-acetylphenoxy) butanoic acid |

pH sensitive | Calicheamicin | Pfizer/Wyeth |

| 2 | Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) |

mc- ValCitPABC |

Lysosomal | MMAE | Seattle/Takeda |

| 3 | Trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla) |

MCC | Non cleavable | Maytansine DM1 | Genentech Roche |

| 4 | Inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa) |

Hydrazone | pH sensitive | Calicheamicin | Pfizer/Wyeth |

| 5 | Polatuzumab vedotin (Polivy) |

mc- ValCitPABC |

Lysosomal degradation | MMAE | Genentech Roche |

| 6 | Enfortumab vedotin (Padcev) |

mc- ValCitPABC |

Lysosomal degradation | MMAE | Astellas/Seattle Genetics |

| 7 | Trastuzumab deruxtecan (Enhertu) |

mc-GGFG-aminol | Lysosomal degradation | Deruxtecan, Dxd | Daiichi-Sankyo/AstraZeneca |

| 8 | Sacituzumab govitecan (Trodelvy) |

mc-PEG-carbonate | pH | SN-98 | Immunomedics |

| 9 | Belantamab mafodotin (Blenerp)* | mc-MMAF | Non cleavable | MMAF | GSK |

| 10 | Loncastuximab tesirine (Zynlonta) |

mc- ValCitPABC |

Lysosomal degradation | SG3199, PDB dimer | ADC Therapeutics |

| 11 | Tisotumab vedotin (Tivdak) |

mc- ValCitPABC | Lysosomal degradation | MMAE | Genmab and Seattle Genetics |

| 12 | Disitamab Vedotin (Aidixi) |

mc- ValCitPABC |

Lysosomal degradation | MMAE | RemeGen |

| 13 | Moxetumomab pasudotox (Lumoxiti) | mc-ValCitPABC | Lysosomal degradation | PE38 | AstraZeneca |

| 14 | Cetuximab sarotalocan (Akalux) | NA | NA | IRDye700DX | Rakuten Medical |

| 15 | Mirvetuximab Soravtansine (ELAHERE) |

Disulfide-containing cleavable linker sulfo-SPDB | Glutathione cleavable | Maytansinoid DM4 | ImmunoGen |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).