Submitted:

13 May 2023

Posted:

15 May 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

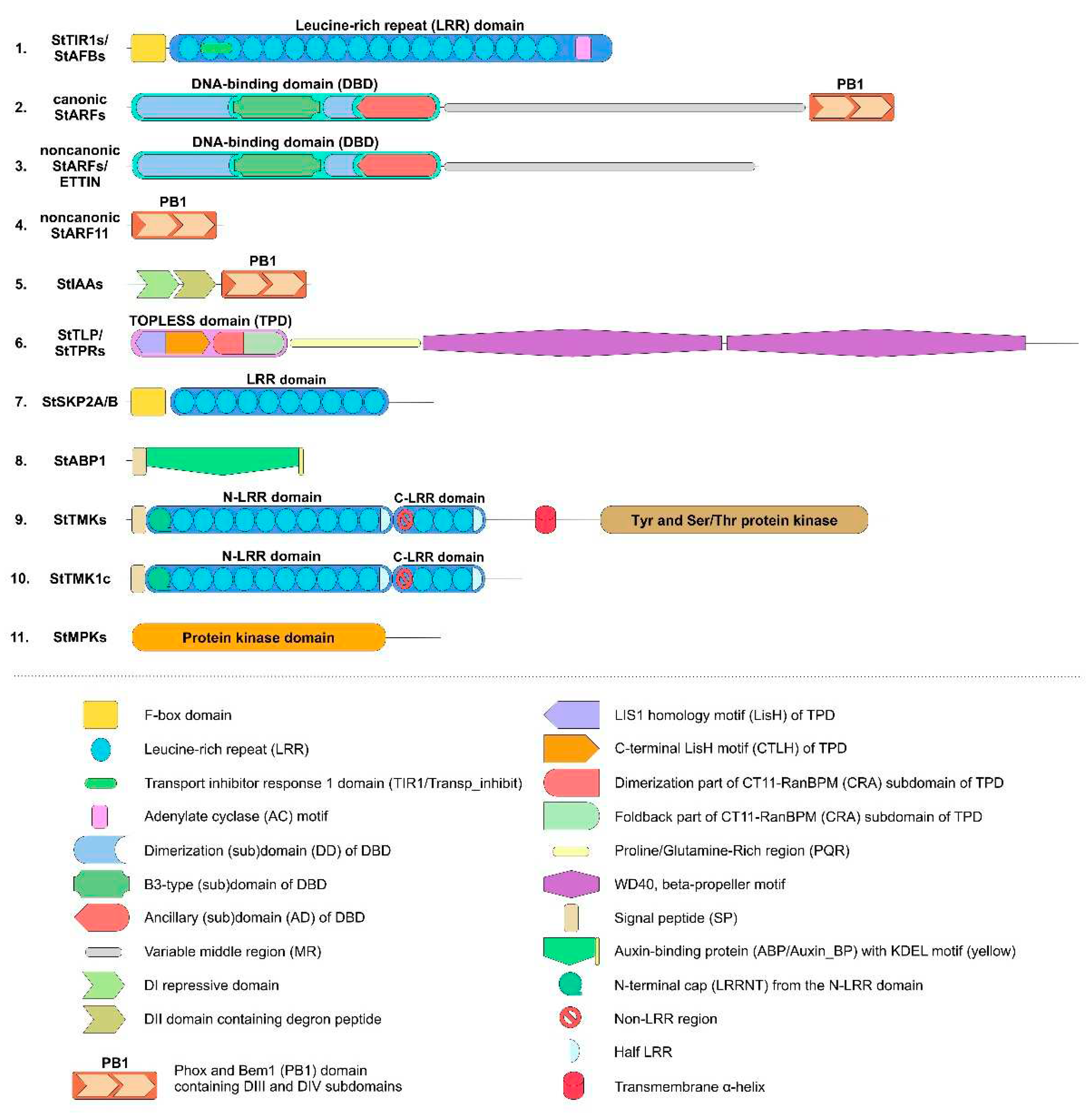

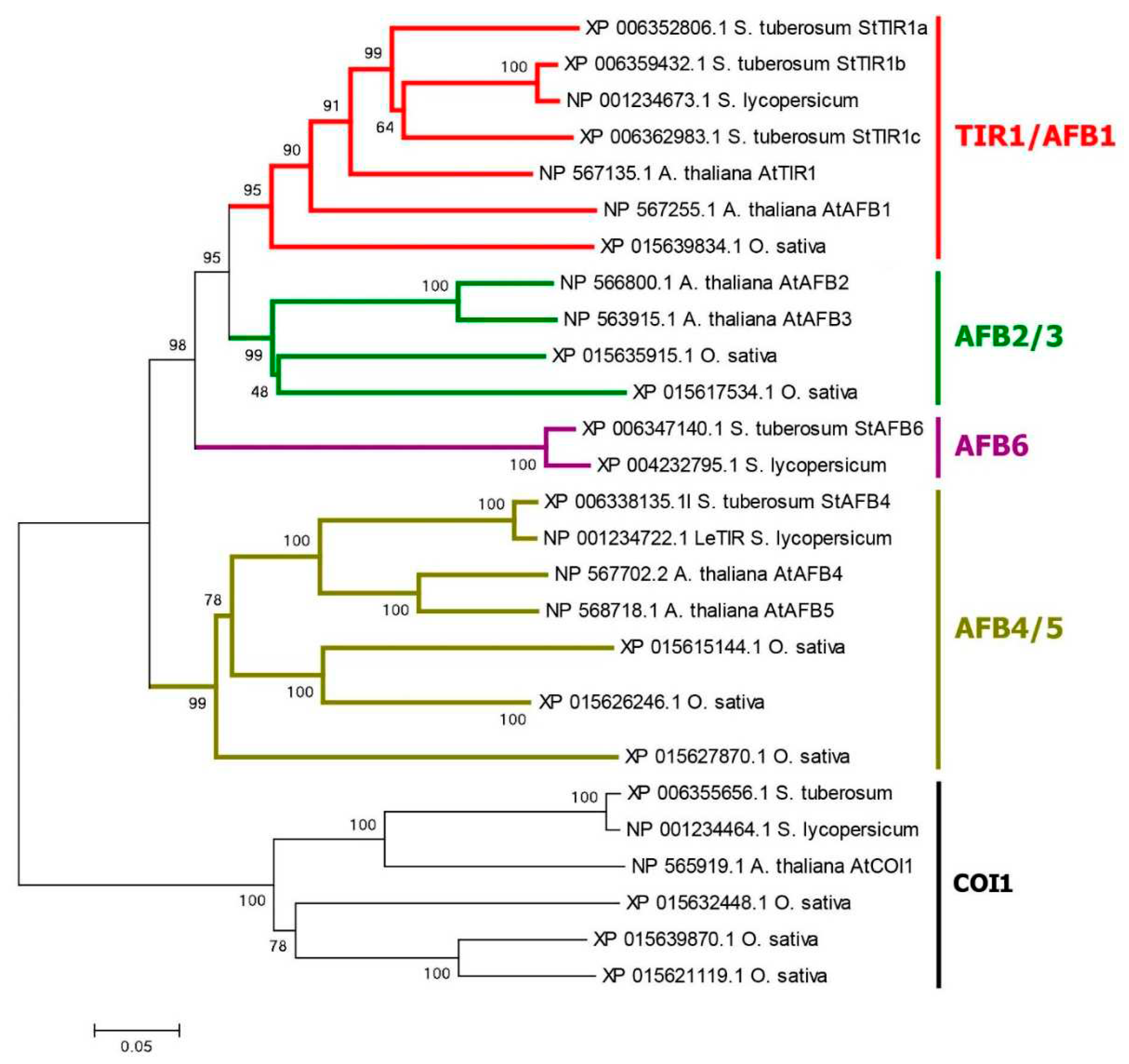

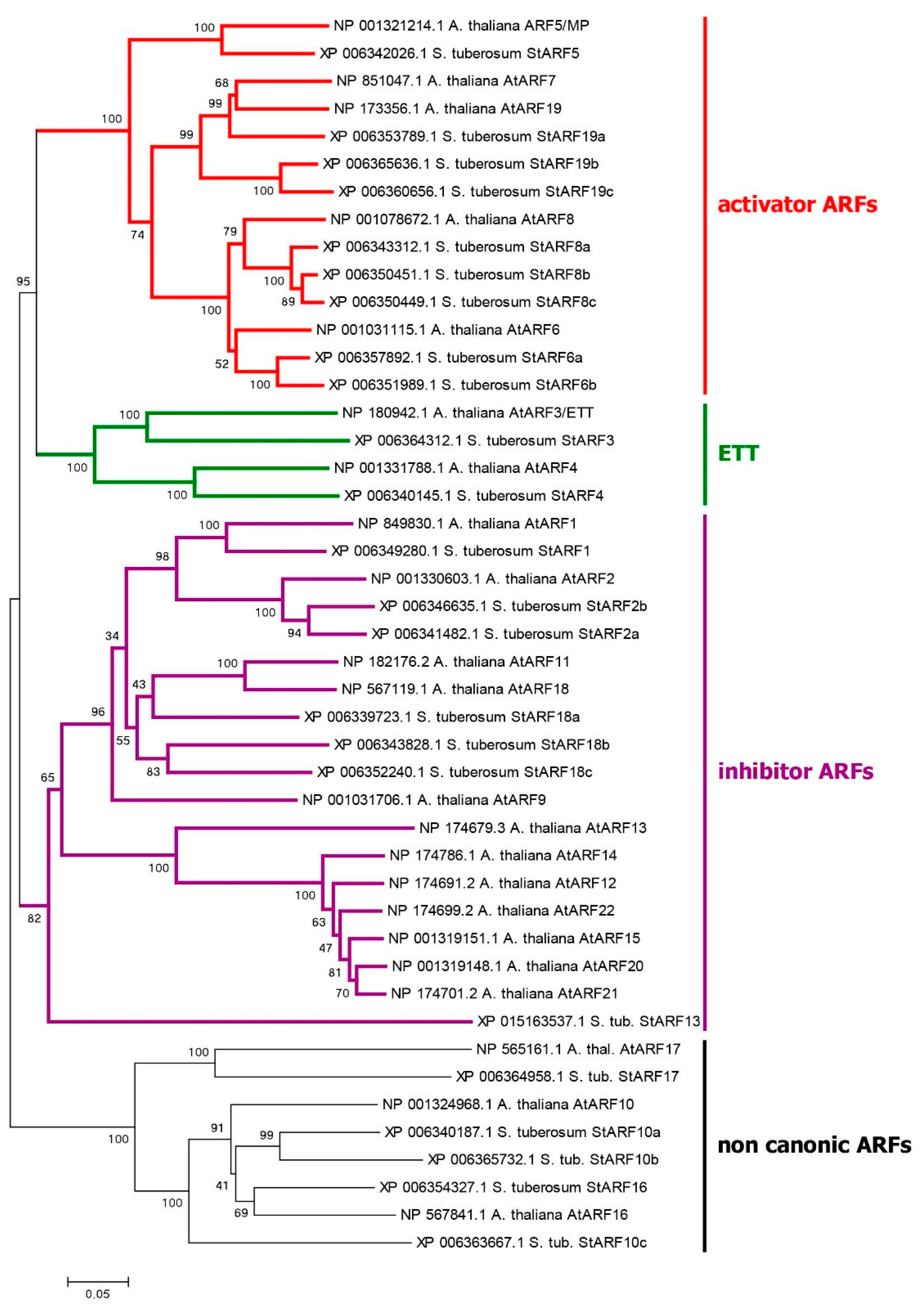

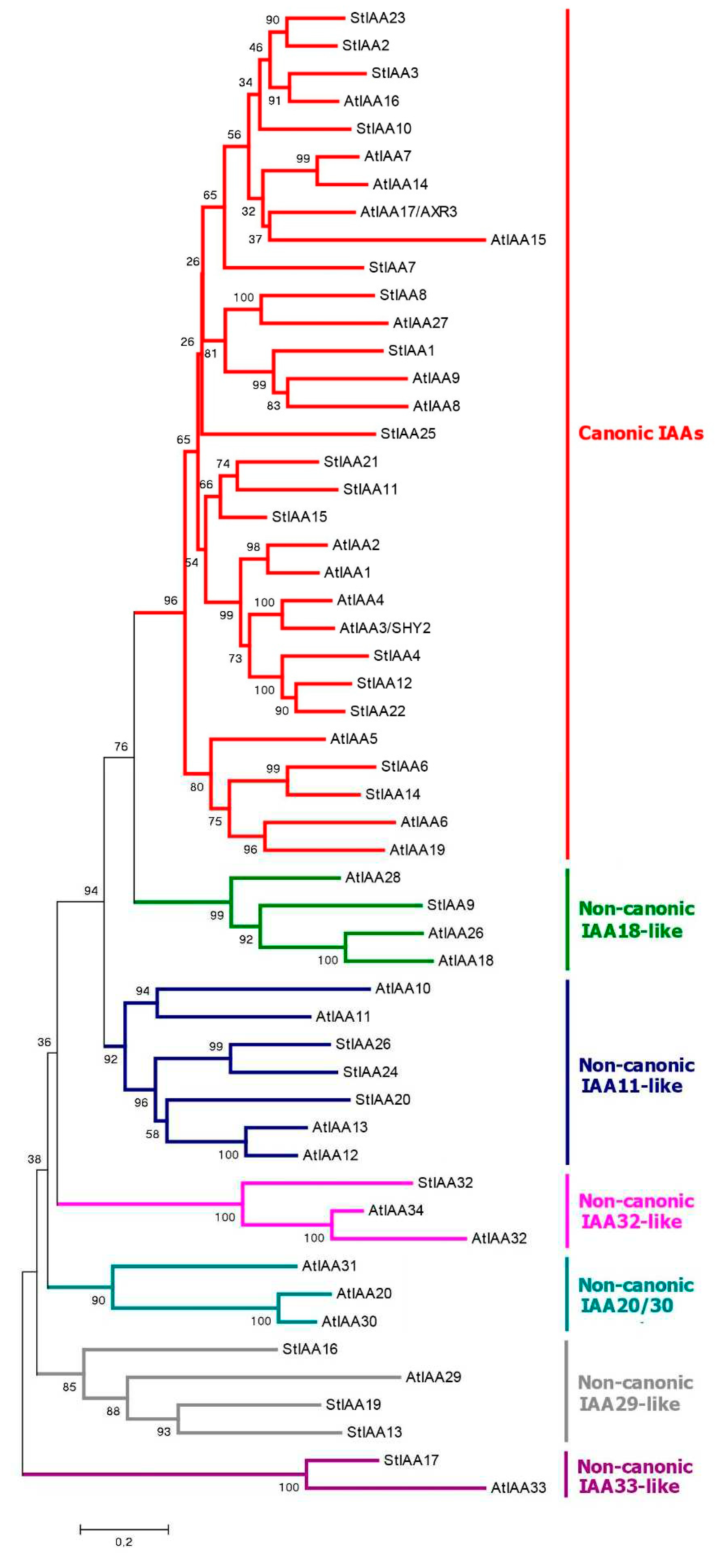

2.1. Genes/Proteins Related to Canonical Auxin Signaling in Potato

2.2. Genes/Proteins for Noncanonical Auxin Signaling in Potato

2.3. Expression Patterns of Auxin-Related Genes

2.3.1. Canonical Genes

2.3.2. Noncanonical Genes

2.3.3. Quantitative Comparison of Expression Patterns of Auxin Signaling Genes

2.4. Molecular Modeling of Key Elements of Auxin Signaling

2.4.1. Modeling of 3D-Structure of Canonical Auxin Receptors of TIR1 Superfamily

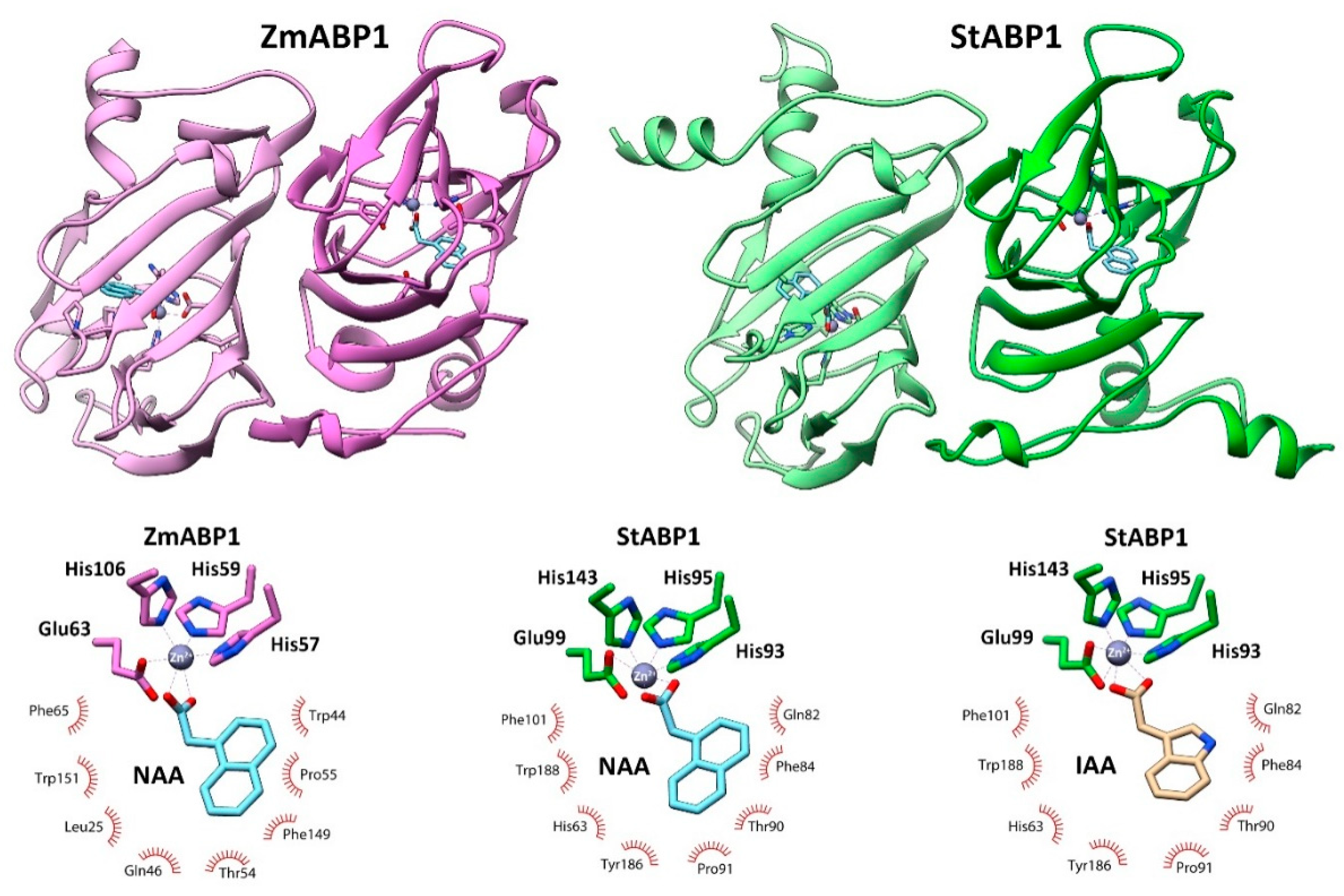

2.4.2. Modeling of 3D-Structure of ABP1 Orthologs – Extranuclear Auxin Receptor

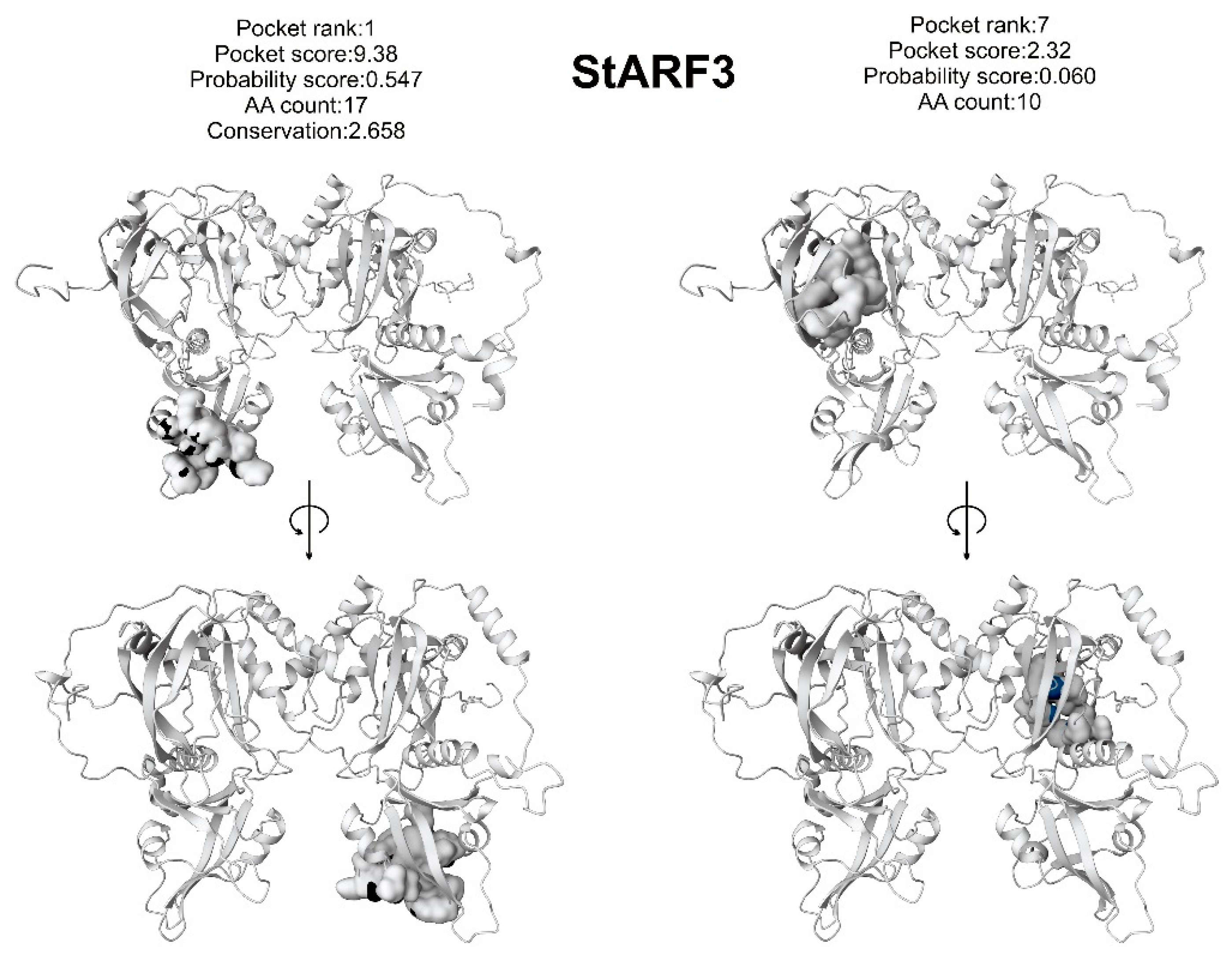

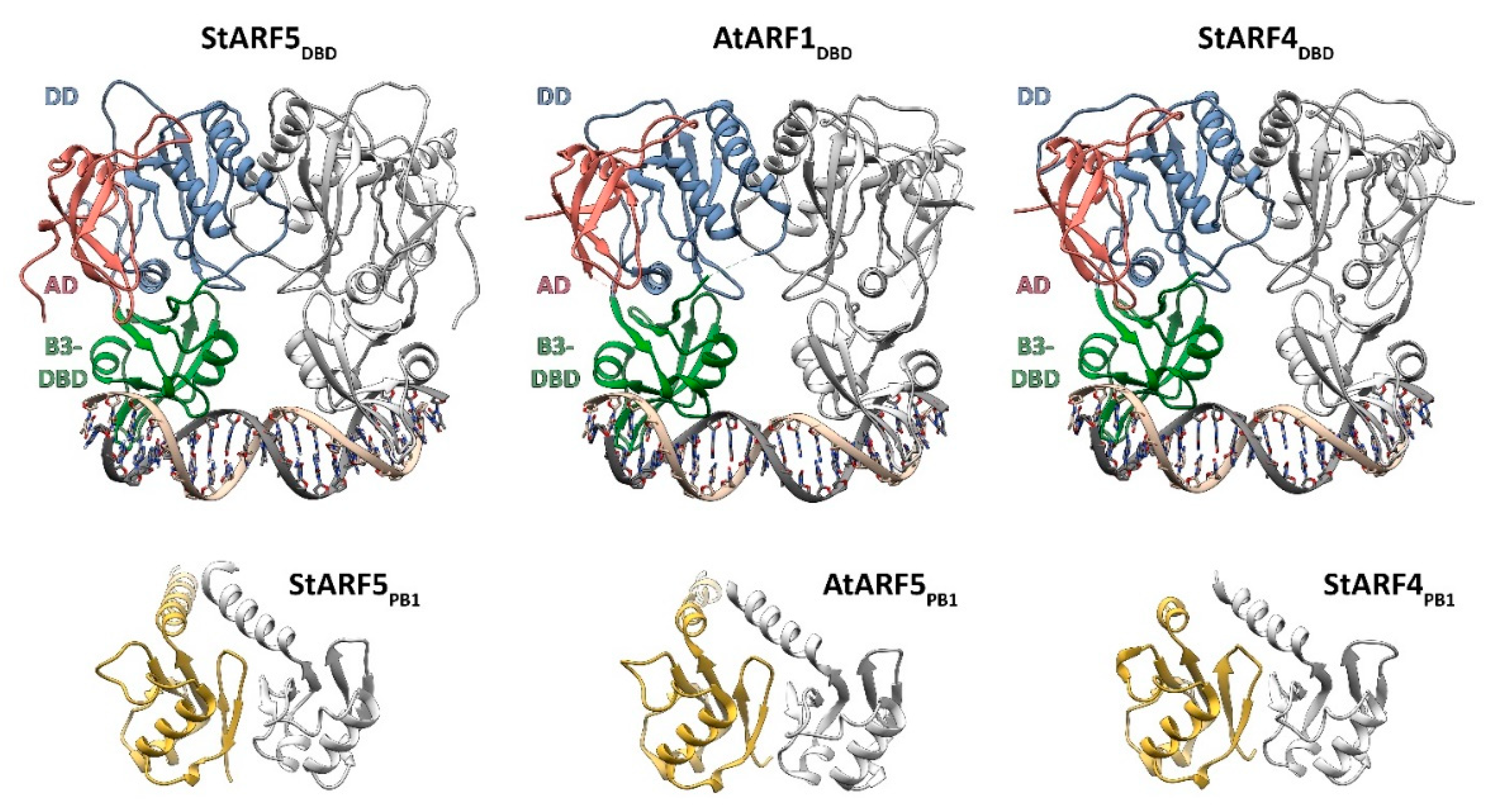

2.4.3. Modeling of Putative Components of Noncanonical Auxin Signaling in Potato

2.4.4. Main Conclusions of Molecular Modeling and Docking

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Analysis of Auxin Signaling-Related Genes

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

3.3. Plant Growth Conditions

3.4. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

3.5. Statistics

3.6. Molecular Modeling

4. Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, D.; Wareing, P.F. Studies on tuberization of Solanum andigena. II. Growth hormones and tuberization. New Phytol. 1974, 73, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksenova, N.P.; Konstantinova, T.N.; Golyanovskaya, S.A.; Kossmann, J.; Willmitzer, L.; Romanov, G.A. Transformed potato plants as a model for studying the hormonal and carbohydrate regulation of tuberization. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2000, 47, 370–379. [Google Scholar]

- Romanov, G.A; Aksenova, N.P; Konstantinova, T.N.; Golyanovskaya, S.A.; Kossmann, J.; Willmitzer, L. Effect of indole-3-acetic acid and kinetin on tuberisation parameters of different cultivars and transgenic lines of potato in vitro. Plant Growth Regul. 2000, 32, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Cheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F. Comparative proteomic analysis of potato (Solanumtuberosum L.) tuberization in vitro regulated by IAA. Am. J. Potato Res. 2018, 95, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolachevskaya, O.O.; Lomin, S.N.; Arkhipov, D.V.; Romanov, G.A. Auxins in potato: Molecular aspects and emerging roles in tuber formation and stress resistance. Plant Cell Rep. 38, 681–698. [CrossRef]

- Kondhare, K.R.; Patil, A.B.; Giri, A.P. Auxin: An emerging regulator of tuber and storage root development. Plant Sci. 2021, 306, 110854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Negi, N.P.; Pareek, S.; Mudgal, G.; Kumar, D. Auxin response factors in plant adaptation to drought and salinity stress. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Potato Genome Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence and analysis of the tuber crop potato. Nature 2011, 475, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, S.; Manjul, A.S.; Raigond, P.; Singh, B.; Siddappa, S.; Bhardwaj, V.; Kawar, P.G.; Patil, V.U.; Kardile, H.B. Key players associated with tuberization in potato: potential candidates for genetic engineering. Crit. Rev.Biotechnol. 2017, 37, 942–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannapel, D.J.; Sharma, P.; Lin, T.; Banerjee, A.K. The multiple signals that control tuber formation. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksenova, N.P.; Konstantinova, T.N.; Golyanovskaya, S.A.; Sergeeva, L.I.; Romanov, G.A. Hormonal regulation of tuber formation in potato plants. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 59, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksenova, N.P.; Sergeeva, L.I.; Kolachevskaya, O.O.; Romanov, G.A. Hormonal regulation of tuber formation in potato. In Bulbous Plants: Biotechnology,Ramavat, K., Mérillon, J., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeytilakarathna, P.D. Factors affect to stolon formation and tuberization in potato: a review. Agric. Rev. 2022, 43, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolachevskaya, O.O.; Alekseeva, V.V.; Sergeeva, L.I.; Rukavtsova, E.B.; Getman, I.A.; Vreugdenhil, D.; Buryanov, Y.I. , Romanov, G.A. Expression of auxin synthesis gene tms1 under control of tuber-specific promoter enhances potato tuberization in vitro. Int. Plant Biol. 2015, 57, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolachevskaya, O.O.; Sergeeva, L.I.; Floková, K.; Getman, I.A.; Lomin, S.N.; Alekseeva, V.V.; Rukavtsova, E.B.; Buryanov, Y.I.; Romanov, G.A. Auxin synthesis gene tms1 driven by tuber-specific promoter alters hormonal status of transgenic potato plants and their responses to exogenous phytohormones. Plant Cell Rep. 2017, 36, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolachevskaya, O.O.; Sergeeva, L.I.; Getman, I.A.; Lomin, S.N.; Savelieva, E.M.; Romanov, G.A. Core features of the hormonal status in in vitro grown potato plants, Plant Signal. Behav. 2018, 13, e1467697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolachevskaya, O.O.; Lomin, S.N.; Kojima, M.; Getman, I.A.; Sergeeva, L.I.; Sakakibara, H.; Romanov, G.A. Tuber-specific expression of two gibberellin oxidase transgenes from Arabidopsis regulates over wide ranges the potato tuber formation. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 66, 984–991. [CrossRef]

- Veilleux, R.E. Solanum phureja: anther culture and the induction of haploids in a cultivated diploid potato species. In Haploids in Crop Improvement I, 1990, pp. 530–543. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- M'Ribu, H.K.; Veilleux, R.E. Phenotypic variation and correlations between monoploids and doubled monoploids of Solanum phureja. Euphytica 1991, 54, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Tang, D.; Huang, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Hamilton, J.P.; Visser, R.G.F.; Bachem, C.W.B.; Buell, C.R.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Haplotype-resolved genome analyses of a heterozygous diploid potato. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 1018–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoopes, G.; Meng, X.; Hamilton, J.P.; Achakkagari, S.R.; de Alves Freitas Guesdes, F.; Bolge, M. E.; Coombs, J.J.; Esselink, D.; Kaiser, N.R.; Kodde, L; et al. Phased chromosome-scale genome assemblies of tetraploid potato reveal a complex genome, transcriptome, and predicted proteome landscape underpinning genetic diversity. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 520–536. [CrossRef]

- Mari, R.S.; Schrinner, S.; Finkers, R.; Arens, P.; Schmidt, M.H.W.; Usadel, B.; Klau, G.W.; Marschall, T. Haplotype-resolved assembly of a tetraploid potato genome using long reads and low-depth offspring data. BioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Jiao, W.B.; Krause, K.; Campoy, J.A.; Goel, M.; Folz-Donahue, K.; Kukat, C.; Huettel, B.; Schneeberger, K. Chromosome-scale and haplotype-resolved genome assembly of a tetraploid potato cultivar. Nat. Gen. 2022, 54, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, G.; Calderon-Villalobos, L.I.; Prigge, M.; Peret, B.; Dharmasiri, S.; Itoh, H.; Lechner, E.; Gray, W.M.; Bennett, M.; Estelle, M. Complex regulation of the TIR1/AFB family of auxin receptors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci.USA 2009, 106, 22540–22545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigge, M.J.; Platre, M.; Kadakia, N.; Zhang, Y.; Greenham, K.; Szutu, W.; Pandey, B.K.; Bhosale, R.A.; Bennett, M.; Busch, W.; Estelle, M. Genetic analysis of the Arabidopsis TIR1/AFB auxin receptors reveals both overlapping and specialized functions. eLife 2020, 9, e54740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, L.; Qi, L. , Friml, J. Distinct functions of TIR1 and AFB1 receptors in auxin signaling. BioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friml, J.; Gallei, M.; Gelová, Z.; Johnson, A.; Mazur, E.; Monzer, A.; Rodriguez, L.; Roosjen, M.; Verstraeten, I.; Živanović, B.D.; et al. ABP1-TMK auxin perception for global phosphorylation and auxin canalization. Nature, 2022, 609, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Friml, J.; Ding, Z. Auxin signaling: Research advances over the past 30 years. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Xu, X.; Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; Huang, S.; Wei, H.; Wei, Z. Molecular mechanisms of diverse auxin responses during plant growth and development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delker, C.; Raschke, A.; Quint, M. Auxin dynamics: the dazzling complexity of a small molecule’s message. Planta 2008, 227, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargmann, B.O.; Estelle, M. Auxin perception: in the IAA of the beholder. Plant 2014, 151, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, A.; Harborough, S.R; McLaughlin, H.M.; Natarajan, B.; Verstraeten, I.; Friml, J.; Kepinski, S.; Østergaard, L. Direct ETTIN-auxin interaction controls chromatin states in gynoecium development. eLife 2020, 9, e51787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Villalobos, L.I.; Lee, S.; De Oliveira, C.; Ivetac, A.; Brandt, W.; Armitage, L.; Sheard, L.B.; Tan, X.; Parry, G.; Mao, H.; et al. A combinatorial TIR1/AFB–Aux/IAA co-receptor system for differential sensing of auxin. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.W. Auxin response factors. Plant, Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 1014–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilfoyle, T.J.; Hagen, G. Auxin response factors. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2007, 10, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallei, M.; Luschnig, C.; Friml, J. Auxin signalling in growth: Schrödinger’s cat out of the bag. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2020, 53, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.M.; Serre, N.B.; Oulehlová, D.; Vittal, P.; Fendrych, M. No time for transcription—rapid auxin responses in plants. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernoux, T.; Brunoud, G.; Farcot, E.; Morin, V.; Van den Daele, H.; Legrand, J.; Oliva, M.; Das, P.; Larrieu, A.; Wells, D.; et al. The auxin signalling network translates dynamic input into robust patterning at the shoot apex. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011, 7, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Chen, R.; Li, P.; Yu, Y.; Zheng, R.; Ge, D.; Zheng, W.; Wang, X.; Gu, Y.; Gelová, Z.; et al. TMK1-mediated auxin signalling regulates differential growth of the apical hook. Nature 2019, 568, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, H.M.; Ang, A.C.H.; Østergaard, L. Noncanonical auxin signaling. Cold Spring Harbor Persp. Biol. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Zheng, R.; He, J.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, J.; Xiong, Y.; Xu, T. Noncanonical auxin signaling regulates cell division pattern during lateral root development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 21285–21290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Yu, Q.; Liu, J.; Wen, X.; Yan, Z.; Hu, K.; Li, H.; Kong, X.; Li, C.; Tian, H.; et al. Non-canonical AUX/IAA protein IAA 33 competes with canonical AUX/IAA repressor IAA 5 to negatively regulate auxin signaling. EMBO J. 2020, 39, e101515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Wei, K.; Hu, K.; Tian, T.; Zhang, F.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Su, Y.; Sang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ding, Z. MPK14-mediated auxin signaling controls lateral root development via ERF13-regulated very-long-chain fatty acid biosynthesis. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogan, N.T.; Yin, X.; Ckurshumova, W.; Berleth, T. Distinct subclades of Aux/IAA genes are direct targets of ARF 5/MP transcriptional regulation. New Phytol. 2014, 204, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.J.; Valdés, A.E.; Wang, G.; Ramachandran, P.; Beste, L.; Uddenberg, D.; Carlsbecker, A. PHABULOSA mediates an auxin signaling loop to regulate vascular patterning in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 956–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonini, S.; Deb, J.; Moubayidin, L.; Stephenson, P.; Valluru, M.; Freire-Rios, A.; Sorefan, K.; Weijers, D.; Friml, J.; Ostergaard, L. A noncanonical auxin-sensing mechanism is required for organ morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 2286–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, S.; Kleine-Vehn, J.; Barbez, E.; Sauer, M.; Paciorek, T.; Baster, P.; Vanneste, S.; Zhang, J.; Simon, S.; Čovanová, M.; et al. ABP1 mediates auxin inhibition of clathrin-dependent endocytosis in Arabidopsis. Cell 2010, 143, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamowski, M.; Friml, J. PIN-dependent auxin transport: action, regulation, and evolution. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, M.; Gallei, M.; Tan, S.; Johnson, A.; Verstraeten, I.; Li, L.; Rodriguez, L.; Han, H.; Himschoot, E.; Wang, R.; et al. Systematic analysis of specific and nonspecific auxin effects on endocytosis and trafficking. Plant Physiol. 2021, 186, 1122–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, T. The induction of transport channels by auxin. Planta 1975, 127, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friml, J. Fourteen stations of auxin. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2022, 14, a039859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, R.; Thomson, K.S.; Russo, V.E.A. In-vitro auxin binding to particulate cell fractions from corn coleoptiles. Planta 1972, 107, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napier, R. The story of auxin-binding protein 1 (ABP1). Cold Spring Harbor Persp. Biol. 2021, 13, a039909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.; Dai, N.; Chen, J.; Nagawa, S.; Cao, M.; Li, H.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, X.; De Rycke, R.; Rakusová, H.; et al. Cell surface ABP1-TMK auxin-sensing complex activates ROP GTPase signaling. Science 2014, 343, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlke, R.I.; Fraas, S.; Ullrich, K.K.; Heinemann, K.; Romeiks, M.; Rickmeyer, T.; Klebe, G.; Palme, K.; Lüthen, H.; Steffens, B. Protoplast swelling and hypocotyl growth depend on different auxin signaling pathways. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175, 982–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, N.; Wang, W.; Patterson, S.E.; Bleecker, A.B. The TMK subfamily of receptor-like kinases in Arabidopsis display an essential role in growth and a reduced sensitivity to auxin. PloS One 2013, 8, e60990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelová, Z.; Gallei, M.; Pernisová, M.; Brunoud, G.; Zhang, X.; Glanc, M.; Li, L.; Michalko, J.; Pavlovičová, Z.; Verstraeten, I.; et al. Developmental roles of Auxin Binding Protein 1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Sci. 2021, 303, 110750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajný, J.; Tan, S.; Friml, J. Auxin canalization: From speculative models toward molecular players. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 2022, 102174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurado, S.; Díaz-Triviño, S.; Abraham, Z.; Manzano, C.; Gutierrez, C.; del Pozo, C. SKP2A, an F-box protein that regulates cell division, is degraded via the ubiquitin pathway. Plant J. 2008, 53, 828–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, S.; Abraham, Z.; Manzano, C.; López-Torrejón, G.; Pacios, L.F.; Del Pozo, J.C. The Arabidopsis cell cycle F-box protein SKP2A binds to auxin. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 3891–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Agarwal, P.; Pareek, A.; Tyagi, A.K.; Sharma, A.K. Genomic survey, gene expression, and interaction analysis suggest diverse roles of ARF and Aux/IAA proteins in Solanaceae. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2015, 33, 1552–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Cao, X.; Shi, S.; Ma, Y.; Wang, K.; Liu, S.; Chen, D.; Chen, Q.; Ma, H. Genome-wide survey of Aux/IAA gene family members in potato (Solanum tuberosum): Identification, expression analysis, and evaluation of their roles in tuber development. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 471, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Hao, L.; Zhao, P.; Xu, Y.; Zhong, N.; Zhang, H.; Liu, N. Genome-wide identification, expression profiling and evolutionary analysis of auxin response factor gene family in potato (Solanumtuberosumgroup Phureja). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolachevskaya, O.O.; Myakushina, Y.A.; Getman, I.A.; Lomin, S.N.; Deyneko, I.V.; Deigraf, S.V.; Romanov, G.A. Hormonal regulation and crosstalk of auxin/cytokinin signaling pathways in potatoes in vitro and in relation to vegetation or tuberization stages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Calderon-Villalobos, L.I.; Sharon, M.; Zheng, C.; Robinson, C.V.; Estelle, M.; Zheng, N. Mechanism of auxin perception by the TIR1 ubiquitin ligase. Nature 2007, 446, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesh, D. C.; Villalobos, L. I. A. C.; Abel, S. Structural Biology of Nuclear Auxin Action. Trends in plant science 2016, 21, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Kwiatkowski, M.; Chen, H.; Hoermayer, L.; Sinclair, S.; Zou, M.; Del Genio, C. I.; Kubeš, M. F.; Napier, R.; Jaworski, K.; Friml, J. Adenylate cyclase activity of TIR1/AFB auxin receptors in plants. Nature, 2022, 611, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancé, C.; Martin-Arevalillo, R.; Boubekeur, K.; Dumas, R. Auxin response factors are keys to the many auxin doors. New Phytol. 2022, 235, 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truskina, J.; Han, J.; Chrysanthou, E.; Galvan-Ampudia, C.S.; Lainé, S.; Brunoud, G.; Macé, J.; Bellows, S.; Legrand, J.; Bågman, A.-M.; et al. A network of transcriptional repressors modulates auxin responses. Nature 2021, 589, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhou, J.J.; Zhang, J.Z. Aux/IAA gene family in plants: molecular structure, regulation, and function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korasick, D.A.; Westfall, C.S.; Lee, S.G.; Nanao, M.H.; Dumas, R.; Hagen, G.; Guilfoyle, T.J.; Jez, J.M.; Strader, L.C. Molecular basis for AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR protein interaction and the control of auxin response repression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 5427–5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leydon, A. R., Wang, W.; Gala, H. P.; Gilmour, S.; Juarez-Solis, S.; Zahler, M. L.; Zemke, J. E.; Zheng, N.; Nemhauser, J. L. Repression by the Arabidopsis TOPLESS corepressor requires association with the core mediator complex. eLife 2021, 10, e66739. [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.; O'Grady, K.; Chen, S.; Gurley, W. The C-terminal WD40 repeats on the TOPLESS co-repressor function as a protein-protein interaction surface. Plant Mol. Biol. 2019, 100, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, B.; Liu, S.; Chai, J. Crystal structure of an LRR protein with two solenoids. Cell research 2013, 23, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonini, S.; Mas, P.J.; Mas, C.M.; Østergaard, L.; Hart, D.J. Auxin sensing is a property of an unstructured domain in the Auxin Response Factor ETTIN of Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Park, C.; Cha, S.; Han, M.; Ryu, K.S.; Suh, J.Y. Determinants of PB1 domain interactions in auxin response factor ARF5 and repressor IAA17. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 4010–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.; Zhao, X.; Wu, B.; Wang, C.; Wu, C.; Yang, S.; Zhou, J.; Xue, Z. Auxin response factors are ubiquitous in plant growth and development, and involved in crosstalk between plant hormones: a review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.J.; Marshall, J.; Bauly, J.; Chen, J. G.; Venis, M.; Napier, R.M.; Pickersgill, R.W. Crystal structure of auxin-binding protein 1 in complex with auxin. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 2877–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, M.; Kumar, S. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics. Oxford University Press, New York., 2000.

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalışkan, M.E.; Yavuz, C.; Yağız, A.K.; Demirel, U.; Çalışkan, S. Comparison of aeroponics and conventional potato mini tuber production systems at different plant densities. Pot. Res. 2021, 64, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicot, N.; Hausman, J.F.; Hoffmann, L.; Evers, D. Housekeeping gene selection for real-time RT-PCR normalization in potato during biotic and abiotic stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 2907–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, E.; Vriend, G. YASARA View - molecular graphics for all devices – from smartphones to workstations. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2981–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boer, D.R.; Freire-Rios, A.; van den Berg, W.A.; Saaki, T.; Manfield, I.W.; Kepinski, S.; López-Vidrieo, I.; Franco-Zorrilla, J.M.; de Vries, S.C.; Solano, R.; et al. Structural basis for DNA binding specificity by the auxin-dependent ARF transcription factors. Cell 2014, 156, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire-Rios, A.; Tanaka, K.; Crespo, I.; van der Wijk, E.; Sizentsova, Y.; Levitsky, V.; Lindhoud, S.; Fontana, M.; Hohlbein, J.; Boer, D.R.; et al. Architecture of DNA elements mediating ARF transcription factor binding and auxin-responsive gene expression in Arabidopsis. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 24557–24566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, H.; Mutte, S.K.; Suzuki, H.; Crespo, I.; Das, S.; Radoeva, T.; Fontana, M.; Yoshitake, Y.; Hainiwa, E.; van den Berg, W.; et al. Design principles of a minimal auxin response system. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanao, M.H.; Vinos-Poyo, T.; Brunoud, G.; Thévenon, E.; Mazzoleni, M.; Mast, D.; Lainé, S.; Wang, S.; Hagen, G.; Li, H.; et al. Structural basis for oligomerization of auxin transcriptional regulators. Nat. Communs, 2014, 5, 3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sali, A.; Blundell, T.L. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 1993, 234, 779–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, M.-Y.; Sali, A. Statistical potential for assessment and prediction of protein structures. Prot. Sci. 2006, 15, 2507–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature, 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; O’Neill, M.; Pritzel, A.; Antropova, N.; Senior, A.; Green, T.; Zídek, A.; Bates, R.; Blackwell, S.; Yim, J.; et al. Protein complex prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Ding, F.; Wang, R.; Shen, R.; Zhang, X.; Luo, S.; Su, C.; Wu, Z.; Xie, Q.; Berger, B.; et al. High-resolution de novo structure prediction from primary sequence. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuffin, L.J.; Adiyaman, R.; Maghrabi, A.H.A.; Shuid, A.N.; Brackenridge, D.A.; Nealon, J.O.; Philomina, L.S. IntFOLD: an integrated web resource for high performance protein structure and function prediction. Nucl. Acids Res. 2019, 47, W408–W413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDockVina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comp. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, E.; Joo, K.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Raman, S.; Thompson, J.; Tyka, M.; Baker, D.; Karplus, K. Improving physical realism, stereochemistry, and side-chain accuracy in homology modeling: Four approaches that performed well in CASP8. Proteins 2009, 77 (Suppl 9), 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, M.R.; Mackey, M.D. Electrostatic complementarity as a fast and effective tool to optimize binding and selectivity of protein–ligand complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 3036–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jendele, L.; Krivak, R.; Skoda, P.; Novotny, M.; Hoksza, D. PrankWeb: a web server for ligand binding site prediction and visualization. Nucl.Acids Res. 2019, 47, W345–W349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laskowski, R.A.; Swindells, M.B. LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011, 51, 2778–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera - a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M; Jialal, I. Physiology, Endocrine Hormones. [Updated 2022 Sep 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538498/.

- Romanov, G.A. Hormone-binding proteins of plants and the problem of perception of phytohormones. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 1989, 36, 136–146. [Google Scholar]

- Romanov, G.A. The phytohormone receptors. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2002, 49, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).