1. Introduction

A large diversity of microorganisms resides in the oral cavity and colonize teeth, tongue, cheeks, gingival sulcus, tonsils, hard palate and soft palate [

1]. In periodontal disease, an alteration in the microbial composition and/or pathogenicity occurred, resulting in microbial dysbiosis [

2] that can induce an exacerbated inflammatory response associated with the secretion of cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which promote destruction of the tooth supporting structures, including the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone [

3,

4]. Periodontal tissue damage is also caused by an excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which contribute to cellular apoptosis and cause oxidative stresses [

5]. As described by Socransky et al. [

6], “the red complex” composed by

Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia, and

Treponema denticola has been strongly associated with the severity of periodontitis. Among these periodontopathogenic bacteria, the Gram-negative bacterium

P. gingivalis is thought to cause the dysbiosis condition and initiate the inflammatory process of periodontal disease [

7].

The oral epithelium is the main structure of the oral cavity that provides physical, chemical, and immunological barriers against chemical or microbial challenge [

8]. During periodontal disease, colonization of the gingival sulcus by periodontopathogenic bacteria leads to the release of microbial virulence factors and toxins, including lipopolysaccharide (LPS) that stimulate the inflammatory process and tissue destruction [

9].

P. gingivalis, known as a key periodontopathogenic bacterium, can express adhesive components [

10] and damage the epithelial barrier through proteolytic degradation of the junction proteins [

11]. Gingipains, including Arg-gingipains A and B, and Lys-gingipain, are the major extracellular and cell-bound proteolytic activities produced by

P. gingivalis [

12]. More specifically, gingipains mediate the collagen degradation, mainly type I collagen, which is particularly abundant in periodontal tissues [

12]. In addition, gingipains induce host defense perturbation through degradation of cellular signaling molecules and inactivation of cellular functions [

12,

13].

To enhance the outcome of periodontal disease treatments, several adjuncts to non-surgical periodontal therapy have been proposed, including local delivery drugs such as antibiotics and antimicrobials agents. In recent years, natural products have been extensively studied due to their high safety, cost-effectiveness and beneficial properties as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial. In this context, hesperidin is a flavonoid glycoside found in high amounts in citrus fruits such as sweet oranges, lemons, limes, and tangerines [

14]. Hesperidin has been reported to exert beneficial effects on various diseases, including neurological, cardiovascular and other disorders, due to their anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative and anti-cancer properties [

15]. With respect to periodontal disease, in vivo studies using rodent models showed that hesperidin can promote an ameliorative effect on the alveolar bone loss and attenuate the intensity of the inflammatory process [

16,

17].

Despite evidence suggesting a promising effect of hesperidin for periodontal disease, additional studies are necessary to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of action of this flavonoid. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of hesperidin on P. gingivalis-mediated barrier function damage and ROS production in an oral epithelial model. Moreover, the ability of hesperidin to attenuate the expression of inflammatory cytokines and MMPs by P. gingivalis-stimulated macrophages was studied.

3. Discussion

In periodontal disease, damage and destruction of periodontal tissues are caused mainly by an inappropriate host response to microorganisms and their products.

P. gingivalis can disturb the epithelial integrity and invade into the deeper periodontal tissues triggering an inflammatory response [

19]. In this context, therapies involving agents that enhance the oral mucosa barrier and exhibit anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties are promising for periodontal disease treatment. Among them, hesperidin is an attractive flavonoid with excellent biological properties that can modulate the epithelial cellular immune response [

15]. Then, the aim of the present study was to investigate the effect of hesperidin on

P. gingivalis-mediated damage to the gingival epithelial barrier function, ROS production and inflammatory response using in vitro models.

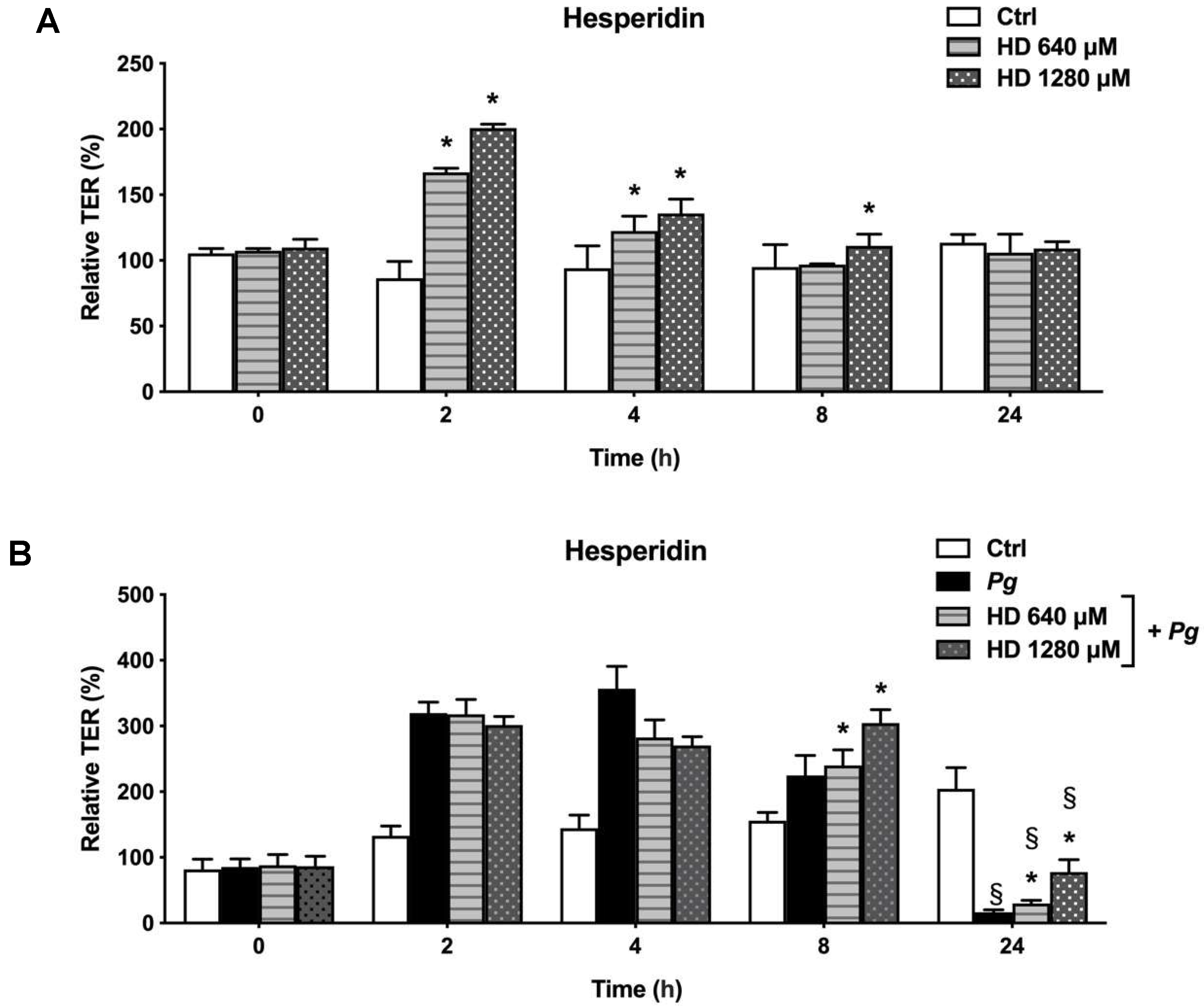

The gingival epithelium is an important barrier against bacterial invasion and for this reason becomes an important early line of defense in the oral cavity [

20]. Considering this concept, diverse flavonoids with capacity to enhance the oral epithelial barrier function are interesting candidates to the treatment or prevention of periodontal disease. In the present in vitro study, we reported interested results of TER after the treatment with hesperidin. More specifically, hesperidin showed a significant increase in TER following a short exposure (2,4 and 8 h). Although the protect capacity of hesperidin on oral epithelial barrier has not been investigated, Guo et al. [

21] showed the capacity of hesperidin of enhance the barrier integrity as well as epithelial permeability in Caco-2 cells.

The ability of

P. gingivalis to invade epithelial cells is triggered via the binding of fimbriae to cellular adhesion molecules thereby disrupting the epithelial integrity [

22,

23]. These cell-cell interactions are critical for the innate immune response against microbial and toxic challenge [

24]. In the present study, using an in vitro epithelial barrier model stimulated with

P. gingivalis, cells revealed a progressive increase of the TER after 2 and 8 h of incubation. After 24 h, the TER values began to decrease indicating a damage on the function of the epithelial barrier. These data are in agreement with a previous in vitro study that showed the same tendency in TER values [

19]. On the other hand, our results showed that cells infected with

P. gingivalis and treated with hesperidin showed a positive effect after 24 h by increasing the TER values when compared to the cells infected with bacteria alone. It remains unclear what is the exact mechanism of the protective effect of hesperidin on the epithelial barrier integrity in our model.

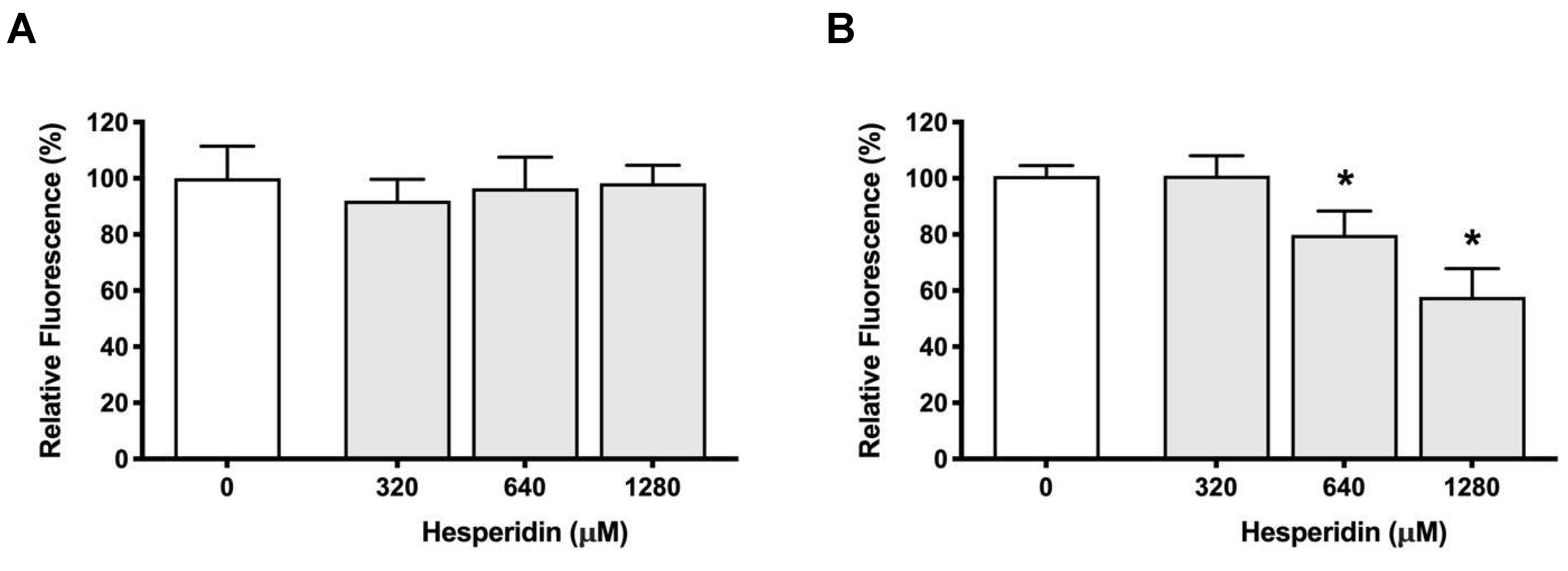

P. gingvalis is able to attach to the periodontal tissues and several investigations has been reported regarding its adhesion to epithelial cells [

25]. Using an in vitro study, we showed that

P. gingivalis was able to adhere to oral epithelial cells. However, hesperidin did not show a capacity to decrease this adhesion. In contrast, using a basement membrane model, hesperidin was able to decrease the adherence of

P. gingivalis. Then, our data suggest that hesperidin may alter the ability of

P. gingivalis to adhere to several extracellular matrix proteins, including laminin and type IV collagen, which are constituents of the basement membrane model. To the best of our knowledge, no study previously evaluated the effect of hesperidin on adherence of periodontopathogens to epithelial cells or periodontal tissues/cells.

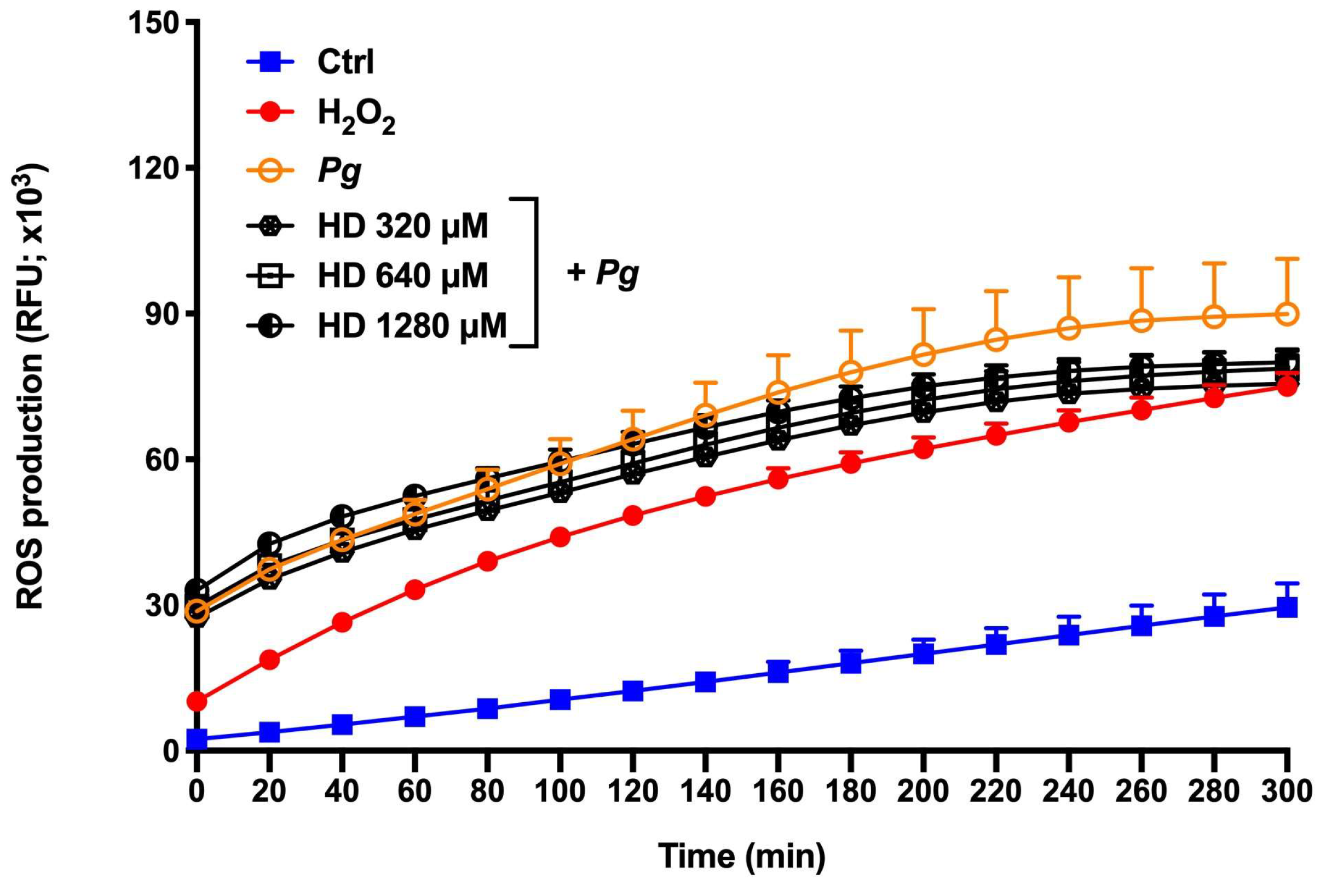

During periodontal disease, the exacerbated production of ROS is responsible for cell apoptosis and dysfunction, alveolar bone loss, and periodontal inflammation [

26]. In this way, the attenuation or inhibition of ROS production is a relevant and important event to regulate several signaling pathways, and consequently inflammatory response [

27]. In the present study, we proposed two ROS production models using

P. gingilvalis alone and

P. gingivalis + H

2O

2 (exacerbated ROS production model) as stimulus

. H

2O

2 is known as a major component of ROS and is widely used as an inducer of oxidative stress. Based in our results, hesperidin can inhibit the ROS production in response to

P. gingivalis. However, hesperidin did not show down-regulating effects in an event with exacerbate levels of ROS production. Previous in vitro studies showed that hesperidin treatment was able to reduce the by-products of lipid peroxidation in the human erythrocyte membrane [

28,

29]. Moreover, hesperidin attenuates the production of intracellular ROS in macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide [

30]. On the other hand, in vivo studies using models of supplementation in rats showed that hesperidin reduces the expression of levels of ROS and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) and increased activity of antioxidants [

31,

32,

33]. Additionally, Lim et al. [

34] demonstrated the marked ability of hesperidin to inhibit high glucose-induced intracellular ROS production in SH−SY5Y neuronal cells. Despite the fact that the literature shows its promising antioxidant property, our results using

P. gingivalis bacteria associated or not with H

2O

2 are not in accordance with them. This may be because

P. gingivalis is able to invade and survive into epithelial cells and then accumulate a hemin layer on the cell surface that have a function of provide oxidative stress protection [

35]. Therefore, more studies are necessary to understand the antioxidant mechanism and effect of hesperidin in the ROS production.

Since

P. gingivalis plays an important role in the induction of inflammatory processes, we evaluated the anti-inflammatory activity of hesperidin against this periodontopathogen. Using a monocyte-macrophage model stimulated with bacteria, we brought evidence that hesperidin was able to inhibit the secretion of IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-8. Previously, the anti-inflammatory potential of hesperidin was demonstrated using various cell models [

36,

37] and the data are in according with our results. In contrast to our results, Li et al. [

38] among the cytokines evaluated, also showed an inhibition of IL-6 after the treatment with hesperidin in an in vivo protocol.

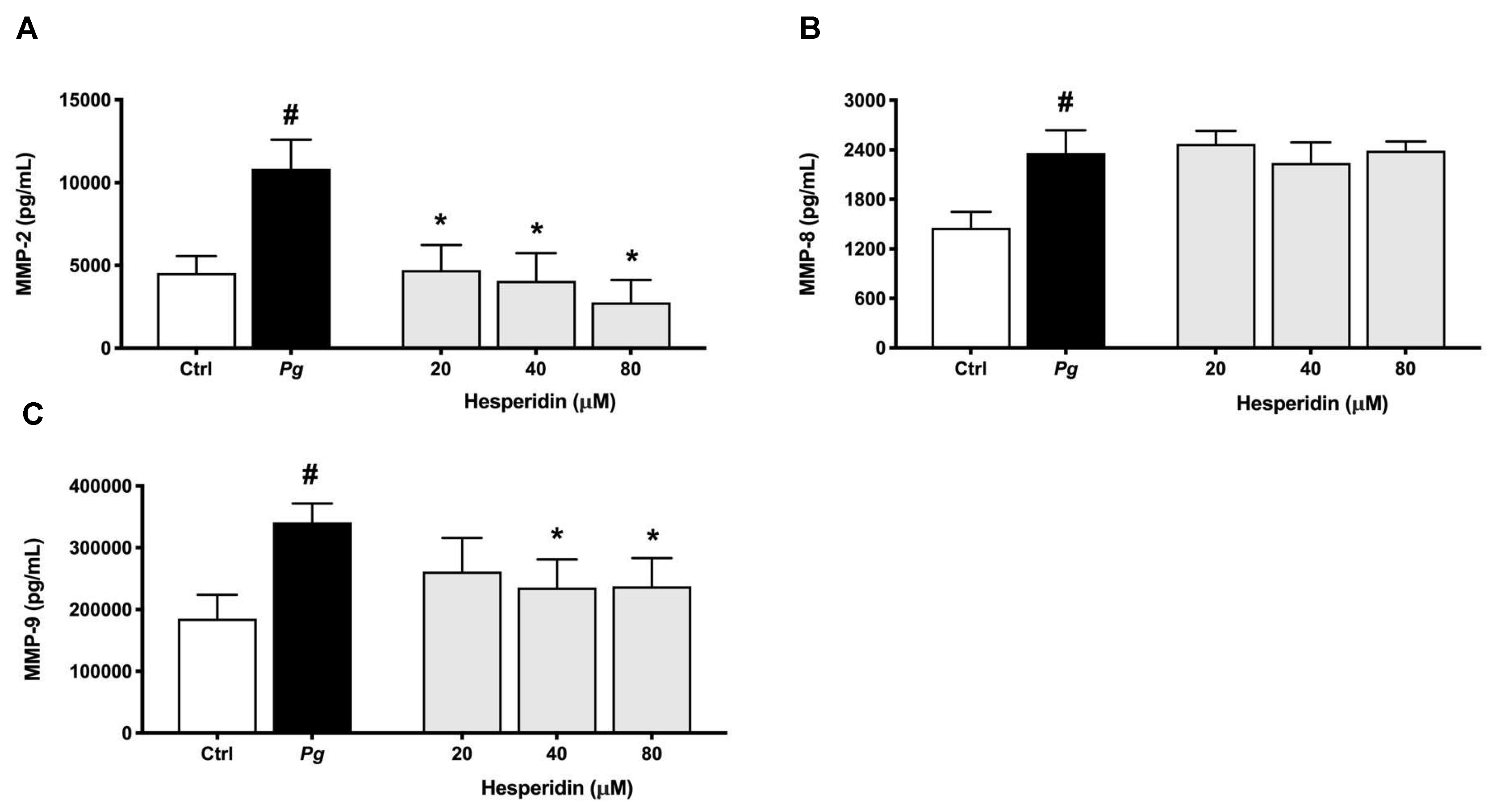

High levels of MMPs such as MMP-1, -2, -8, -9 and -13 are related with the severity and tissue destruction of periodontal disease [

39,

40]. In this context, the downregulation of MMP-2 and -9 by hesperidin as observed in our results may promote an anti-collagenase effect. These findings are in agreement with previous studies that reported the effect of hesperidin to inhibit the expression of these MMPs [

41,

42,

43]. Additionally, we showed for the first time that hesperidin was not able to reduce the expression of MMP-8 level. There are not previous data exploring the mechanism of hesperidin on MMP-8 expression. Overall, our results showed a selective inhibition of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-8, MMP-2 and MMP-9 associated with hesperidin could represent a promising novel approach to the treatment or prevention of periodontal disease.

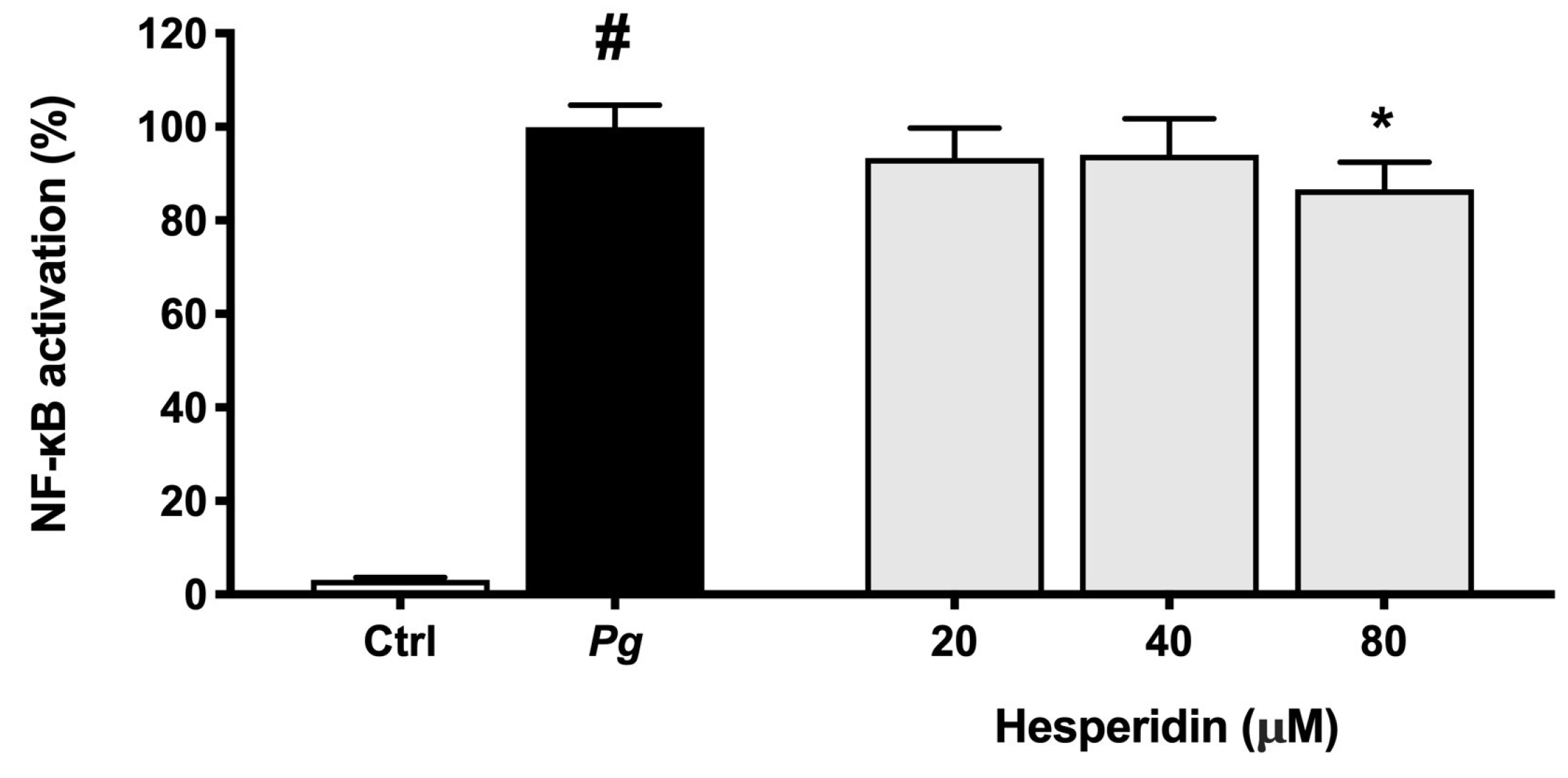

NF-κB pathway is a main key component of the inflammatory response that can be triggered by bacteria and their toxic products resulting in cytokine expression [

44]. Therefore, the capacity of compounds to inactivate this pathway become an important characteristic for modulation of inflammatory response. In this context, our results showed that hesperidin was able to inhibit the NF-κB activation in human monoblastic leukemia cell line transfected with a luciferase gene coupled to a promoter of three NF-κ B- binding sites. As expected, these findings suggest that the inhibitory effect of hesperidin on pro-inflammatory cytokine expression is significantly mediated through the inhibition of the NF-κB pathway. Similarly, Sato et al. [

45] suggested that hesperidin has a significant effect on the regulation of NF-κB signaling pathway.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Hesperidin

Hesperidin was obtained from the USDA-ARS Horticultural Research Laboratory (Fort Pierce, Florida, USA). A stock solution at a concentration of 1 M was prepared in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at 4°C in the dark. In all assays described below, the final concentration of DMSO in the culture medium was ≤ 0.1% (w/v).

4.2. Bacteria and growth conditions

The reference strain P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 was used in this study. Bacteria were grown in an anaerobic chamber (80% N2, 10% CO2, 10% H2) at 37°C in Todd-Hewitt broth (THB; Becton Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD, USA) containing 0.001% (w/v) hemin and 0.0001% (w/v) vitamin K.

4.3. Cell cultures

The B11 human oral epithelial cell line [

46], which was kindly provided by S. Gröger (Justus Liebig University Giessen, Germany), was cultivated in keratinocyte serum-free medium (K-SFM; Life Technologies Inc., Burlington, ON, Canada) supplemented with 50 µg/mL of bovine pituitary extract, 5 ng/mL of human epidermal growth factor, 100 µg/mL of penicillin G-streptomycin, and 0.5 µg/mL of amphotericin B. The U937 human monocyte cell line (CRL-1593.2), which was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) was cultivated in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium (RPMI; Life Technologies Inc.) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 µg/mL of penicillin G/streptomycin. The human monoblastic leukemia cell line U937 3xκ B-LUC, a subclone of the U937 cell line transfected with a luciferase gene coupled to a promoter of three NF-κ B- binding sites [

47], was kindly provided by R. Blomhoff (University of Oslo, Norway). This cell line was cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 μg/mL of penicillin G/streptomycin and 75 μg/mL of hygromycin B. All cell cultures were incubated in a humidified incubator with a 5% CO

2 atmosphere at 37ºC.

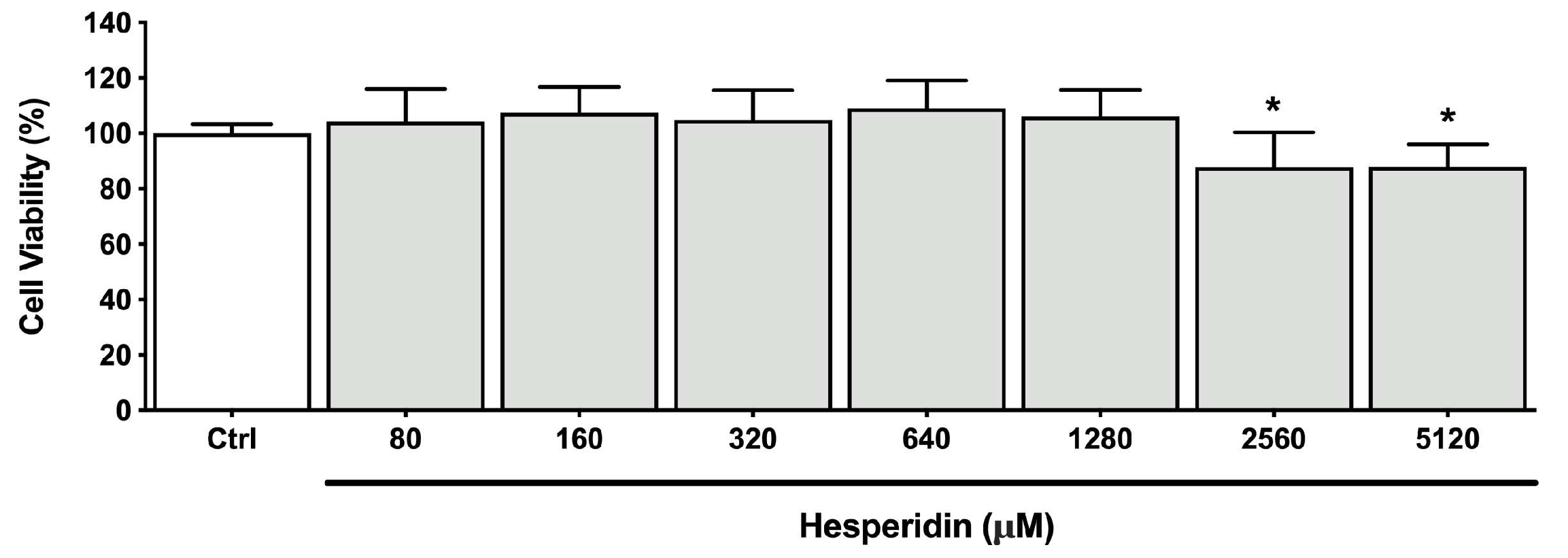

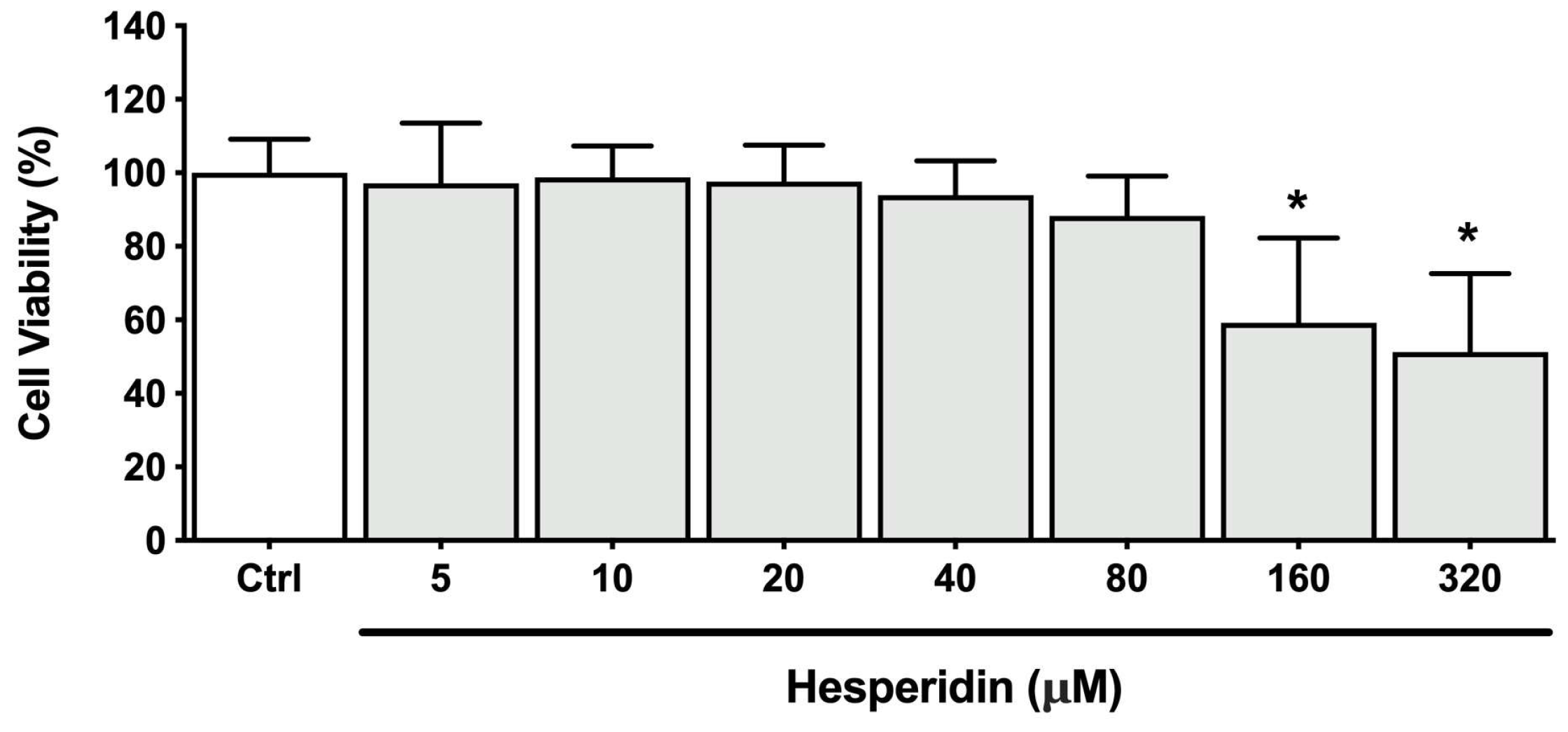

4.4. Oral epithelial barrier integrity

To investigate the effect of hesperidin on the epithelial barrier integrity challenged or not with

P. gingivalis, the B11 human oral epithelial cell line [

46] was used. First, non-cytotoxic concentrations of hesperidin were determined using a MTT (3-[4,5-diethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5diphenyltetrazolium bromide) colorimetric assay (Roche Diagnostics, Laval, QC, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s instructions following a 48-h treatment. The epithelial cells were seeded onto Transwell

TM clear polyester membrane insert (6.5 mm diameter, 0.4 μm pore size; Corning Co., Cambridge, MA, USA) (3 x 10

5 cells per insert). Basolateral and apical compartments were filled with 0.6 mL and 0.1 mL of culture medium, respectively. Then, the plates were incubated at 37ºC in a 5% CO

2 atmosphere for 72 h. After this period, the culture medium was replaced with fresh antibiotic-free K-SFM, and the plates were further incubated for 16 h. Then, in the first setup, non-cytotoxic concentrations of hesperidin (640 and 1280 µM) were added to the apical compartments, and in the second setup,

P. gingivalis at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10

4 prepared in antibiotic-free K-SFM was associated or not with non-cytotoxic concentrations and added to the apical compartments. Finally, the integrity of the epithelial tight junctions was determined by monitoring the transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) using an ohmmeter (EVOM2, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA). TER was determined after 0, 2, 4, 8, and 24 h of incubation at 37ºC in a 5% CO

2 atmosphere. Resistance values were calculated in Ohms (Ω)/cm

2 by multiplying the resistance values by the surface area of the membrane filter. Results were expressed as a percentage of the basal control value measured at time 0 (100% value). Assays were carried out in triplicate in two independent experiments and the means ± standard deviations were calculated.

4.5. Adherence of P. gingivalis to human oral epithelial cells and a basement membrane model

The effect of hesperidin on the adherence of

P. gingivalis to human oral epithelial cells and a basement membrane model (Cultrex Basement Membrane Extract [BME]; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was evaluated, as previously described [

48]. First, a 24-h culture of

P. gingivalis was harvested by centrifugation (9,000 x g for 5 min), washed in 10 mm phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2), and suspended in K-SFM medium or 50 mM PBS (pH 8) containing 0.03 mg/mL of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), to assess adherence to B11 human oral epithelial cell or the basement membrane model, respectively. Then, the

P. gingivalis suspension was incubated in the dark at 37°C for 30 min with constant shaking. Thereafter, the labeled bacteria were washed three times by centrifugation (9,000 x g for 5 min). In a first analysis, oral epithelial cells (1 × 10

6 cells/mL) were seeded in sterile black wall, clear flat bottom 96-well microplates (Greiner Bio-One North America Inc.) and were incubated overnight at 37°C in a 5% CO

2 atmosphere to allow cell adherence. Then, the medium was removed and the cell monolayers were pre-incubated with hesperidin (320, 640 or 1280 µM; in K-SFM) for 30 min prior to adding FITC-labeled

P. gingivalis at an MOI of 1000. The cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO

2 atmosphere. After 4 h, unbound bacteria were removed, the wells were washed with PBS and the number of bacteria adhered was determined by relative fluorescence units (RFU) using a Synergy 2 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA) (excitation wavelength of 495 nm and an emission wavelength of 525 nm). In a second analysis, the BME containing laminin, collagen IV, entactin, and heparin sulfate proteoglycan was diluted 1:10 in ice-cold PBS and 100 μL were added to the wells of 96-well clear bottom black microplates. The microplates were maintained for 2 h at room temperature to allow gelification. Then, the wells were washed with PBS, and two-fold serial dilutions of hesperidin (320, 640 or 1280 µM in PBS) were added for 30 min. Thereafter, FITC-labeled

P. gingivalis (OD660 = 0.5) were added to each well (100 μL), and the microplate was maintained at 37°C for 4 h. The number of bacteria adhered to the basement membrane model was determined as described above. Wells without

P. gingivalis were used as controls to measure basal auto-fluorescence and wells without hesperidin were used to determine 100% adherence values. Adherence assays were carried out in triplicate in three independent experiments, and the means ± standard deviations were calculated.

4.6. Reactive oxygen species production by human oral epithelial cells

The B11 human oral epithelial cell line (3 x 105 cells/well) were seeded in black wall, clear flat bottom 96-well microplates (Greiner Bio-One North America, Monroe, NC, USA) and were incubated overnight at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. A fluorometric assay to monitor the oxidation of 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescein-diacetate (DCF-DA; Sigma-Aldrich Canada Co., Oakville, ON, Canada) into a fluorescent compound was used to measure ROS production. A 40-mM stock solution of DCF-DA was freshly prepared in DMSO. The cells were washed with Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS; HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA) and were incubated for a further 30 min in the presence of 100 µM DCF-DA in HBSS. Keratinocytes were washed with HBSS to remove the excess of DCF-DA. Then, the cells were treated with P. gingivalis at an MOI of 100 either in the presence or absence of 1 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and in the absence or presence of hesperidin (320, 640 or 1280 µM) previously prepared in HBSS. ROS production by monitoring fluorescence emission was recorded every 20 min for 5 h using a Synergy 2 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments) (485 nm excitation filter and a 528 nm emission filter). The assays were carried out in triplicate in three independent experiments, and the means ± standard deviations were calculated.

4.7. Cytokine and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) secretion by macrophages

To evaluate the effect of hesperidin on the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α) and MMPs (MMP-2, MMP-8, MMP-9), U937 human monocytes (CRL-1593.2; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were used. Non-cytotoxic concentrations of hesperidin were first determined using a MTT (3-[4,5-diethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5diphenyltetrazolium bromide) colorimetric assay (Roche Diagnostics, Laval, QC, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s instructions following a 24-h treatment. The monocytes (1 × 106 cells/mL) were differentiated into adherent macrophage-like cells by incubation in RPMI-10% FBS containing 100 ng/mL of phorbol myristic acid (PMA; Sigma-Aldrich Canada Co.) for 48 h into 12-well microplates. The adherent macrophage-like cells were washed to remove remaining PMA and non-adherent cells and were maintained in RPMI-10% FBS without PMA for 24 h. Thereafter, the medium was changed and the cells were maintained in RPMI-1% FBS and incubated overnight at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The macrophage-like cells were pre-treated for 2 h with hesperidin (20, 40, or 80 µM) previously prepared in RPMI-1% FBS and were stimulated with P. gingivalis cells at an MOI of 100 for 24 h. Then, the culture medium supernatants were collected and were kept at −20 °C until used. Culture medium collected from cells without treatment with hesperidin and bacteria were used as controls. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) were used to determine cytokines and MMPs concentrations according to the manufacturers’ protocols. Assays were performed in triplicate in three independent experiments, and the means ± standard deviations were calculated.

4.8. Activation of NF-κB in P. gingivalis-stimulated monocytes

To evaluate the effect of hesperidin on P. gingivalis-induced NF-κB activation, the human monoblastic leukemia cell line U937 3xκ B-LUC was used. The monocytes were seeded (105 cells/well) into wells of black wall, black bottom, 96-well microplates (Greiner Bio-One North America) and were pre-incubated with hesperidin (20, 40, or 80 µM) for 30 min. Thereafter, the monocytes were stimulated with P. gingivalis at an MOI of 100 for 6 h. Wells containing monocytes without P. gingivalis or hesperidin were used as controls. Bright-Glo reagent (Promega Corporation, Durham, NC, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol to measure luciferase activity and determine NF-κB activation. Luminescence was monitored using a Synergy 2 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments). Assays were performed in triplicate in three independent experiments, and the means ± standard deviations were calculated.

4.9. Statistical analysis

A one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison test was used to analyze the data. Results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, p < 0.01 or p < 0.001.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G and P.M.M.H.; methodology, P.M.M.H.; software, P.M.M.H.; validation, P.M.M.H.; formal analysis, P.M.M.H.; investigation, P.M.M.H.; resources, D.G.; data curation, P.M.M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M.M.H.; writing—review and editing, P.M.M.H., D.M.P.S., J.M. and D.G.; visualization, P.M.M.H.; supervision, D.G.; project administration, D.G.; funding acquisition, D.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Viability of human oral epithelial cell line B11 after treatment (48 h) with hesperidin. *Significant difference in comparison with the control group (p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Viability of human oral epithelial cell line B11 after treatment (48 h) with hesperidin. *Significant difference in comparison with the control group (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Time- and dose-dependent effects of hesperidin on oral epithelial barrier model (A) and challenged with P. gingivalis (B) as determined by monitoring TER. A 100% value was assigned to the TER values recorded at time 0. Results are expressed as the means ± SD of triplicate assays. *, significant increase (p < 0.05) compared to control cells (A) or P. gingivalis-stimulated cells (B). §, significant decrease (p < 0.05) compared to non-stimulated control cells (B).

Figure 2.

Time- and dose-dependent effects of hesperidin on oral epithelial barrier model (A) and challenged with P. gingivalis (B) as determined by monitoring TER. A 100% value was assigned to the TER values recorded at time 0. Results are expressed as the means ± SD of triplicate assays. *, significant increase (p < 0.05) compared to control cells (A) or P. gingivalis-stimulated cells (B). §, significant decrease (p < 0.05) compared to non-stimulated control cells (B).

Figure 3.

Effect of hesperidin on the adherence of P. gingivalis to human oral epithelial cells (A) and Cultrex® Basement Membrane Extract (B). Results are expressed as the means ± SD to triplicate assays. *, significantly different from the control (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effect of hesperidin on the adherence of P. gingivalis to human oral epithelial cells (A) and Cultrex® Basement Membrane Extract (B). Results are expressed as the means ± SD to triplicate assays. *, significantly different from the control (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Time- and dose-dependent effects of hesperidin on ROS production by P. gingivalis-stimulated epithelial cells. Results are expressed as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. Values are significantly different from P. gingivalis-stimulated epithelial cells (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Time- and dose-dependent effects of hesperidin on ROS production by P. gingivalis-stimulated epithelial cells. Results are expressed as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. Values are significantly different from P. gingivalis-stimulated epithelial cells (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Time- and dose-dependent effects of hesperidin on ROS production by human epithelial cells stimulated synergistically with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and P. gingivalis. Results are expressed as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. Values are significantly different from H2O2 and P. gingivalis-stimulated epithelial cells (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Time- and dose-dependent effects of hesperidin on ROS production by human epithelial cells stimulated synergistically with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and P. gingivalis. Results are expressed as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. Values are significantly different from H2O2 and P. gingivalis-stimulated epithelial cells (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Cell viability of macrophage-like cells after treatment (24 h) with hesperidin. *Significant difference in comparison with the control group (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Cell viability of macrophage-like cells after treatment (24 h) with hesperidin. *Significant difference in comparison with the control group (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Secretion of IL-6 (A), IL-8 (B), TNF-α (C), and IL-1β (D) by macrophage-like cells treated with hesperidin and stimulated with P. gingivalis (MOI = 100) for 24 h. Results are expressed as the means ± SD of triplicate assays for three independent experiments. #, significant increase (p < 0.001) compared to cells not stimulated with P. gingivalis. *, significant decrease (p < 0.001) compared to P. gingivalis-stimulated cells.

Figure 7.

Secretion of IL-6 (A), IL-8 (B), TNF-α (C), and IL-1β (D) by macrophage-like cells treated with hesperidin and stimulated with P. gingivalis (MOI = 100) for 24 h. Results are expressed as the means ± SD of triplicate assays for three independent experiments. #, significant increase (p < 0.001) compared to cells not stimulated with P. gingivalis. *, significant decrease (p < 0.001) compared to P. gingivalis-stimulated cells.

Figure 8.

Secretion of MMP-2 (A), MMP-8 (B), and MMP-9 (C) by macrophage-like cells treated with hesperidin and stimulated with P. gingivalis (MOI = 100) for 24 h. Results are expressed as the means ± SD of triplicate assays for three independent experiments. #, significant increase (p < 0.001) compared to cells not stimulated with P. gingivalis. *, significant decrease (p < 0.001) compared to P. gingivalis-stimulated cells.

Figure 8.

Secretion of MMP-2 (A), MMP-8 (B), and MMP-9 (C) by macrophage-like cells treated with hesperidin and stimulated with P. gingivalis (MOI = 100) for 24 h. Results are expressed as the means ± SD of triplicate assays for three independent experiments. #, significant increase (p < 0.001) compared to cells not stimulated with P. gingivalis. *, significant decrease (p < 0.001) compared to P. gingivalis-stimulated cells.

Figure 9.

NF-κB activation in U937-3xκB monocytic cell line induced by P. gingivalis (MOI = 100). A value of 100% was assigned to the activation obtained with P. gingivalis in the absence of hesperidin. Results are expressed as the means ± SD of triplicate assays for three independent experiments. #, significant increase (p < 0.01) compared to cells not stimulated with P. gingivalis. *, significant decrease (p < 0.01) compared to P. gingivalis-stimulated cells.

Figure 9.

NF-κB activation in U937-3xκB monocytic cell line induced by P. gingivalis (MOI = 100). A value of 100% was assigned to the activation obtained with P. gingivalis in the absence of hesperidin. Results are expressed as the means ± SD of triplicate assays for three independent experiments. #, significant increase (p < 0.01) compared to cells not stimulated with P. gingivalis. *, significant decrease (p < 0.01) compared to P. gingivalis-stimulated cells.