Submitted:

12 May 2023

Posted:

12 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

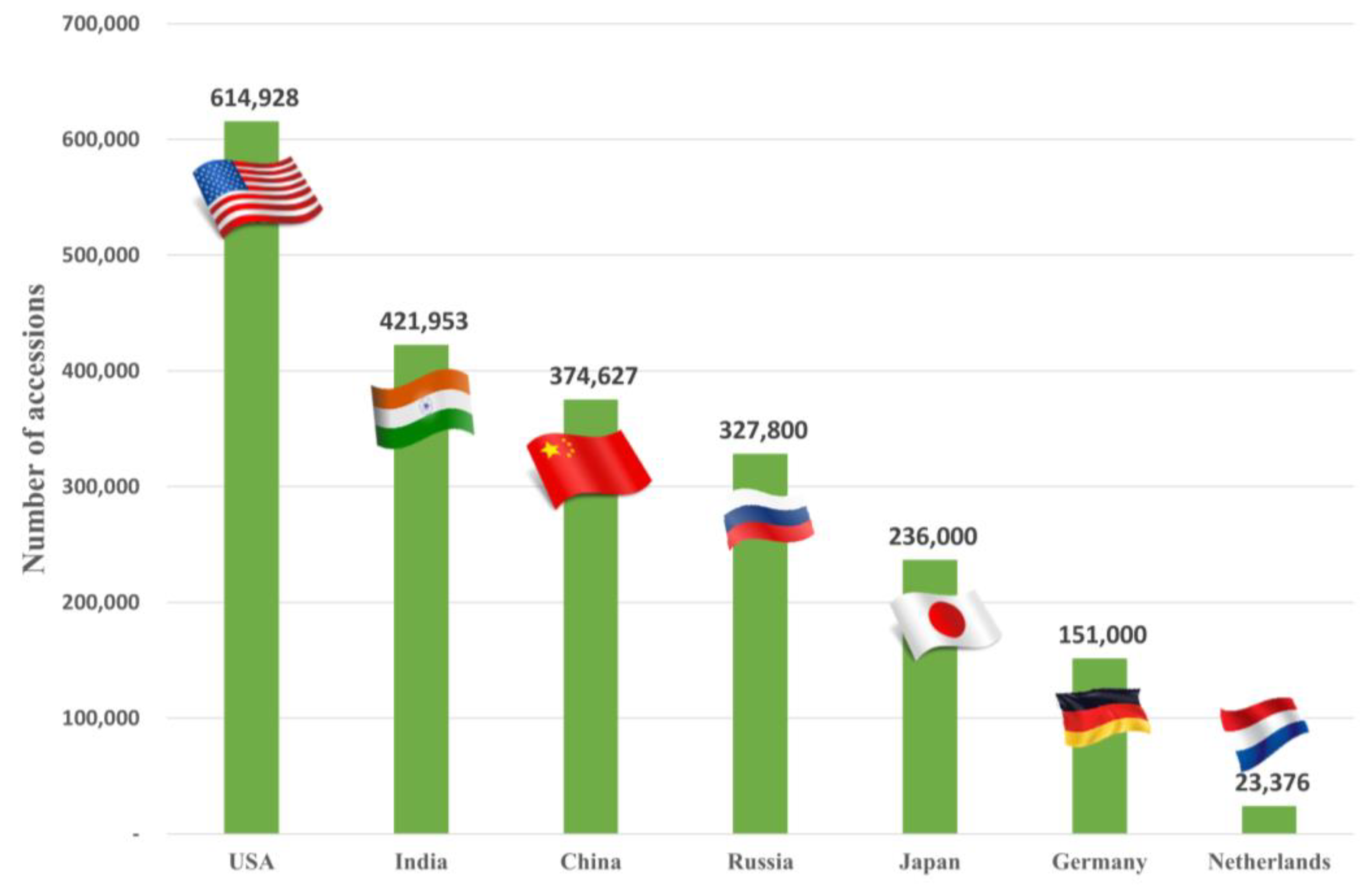

1. Introduction to the National Agrobiodiversity Center (RDA-Genebank)

2. RDA-Genebank`s Efforts on the Nagoya Protocol

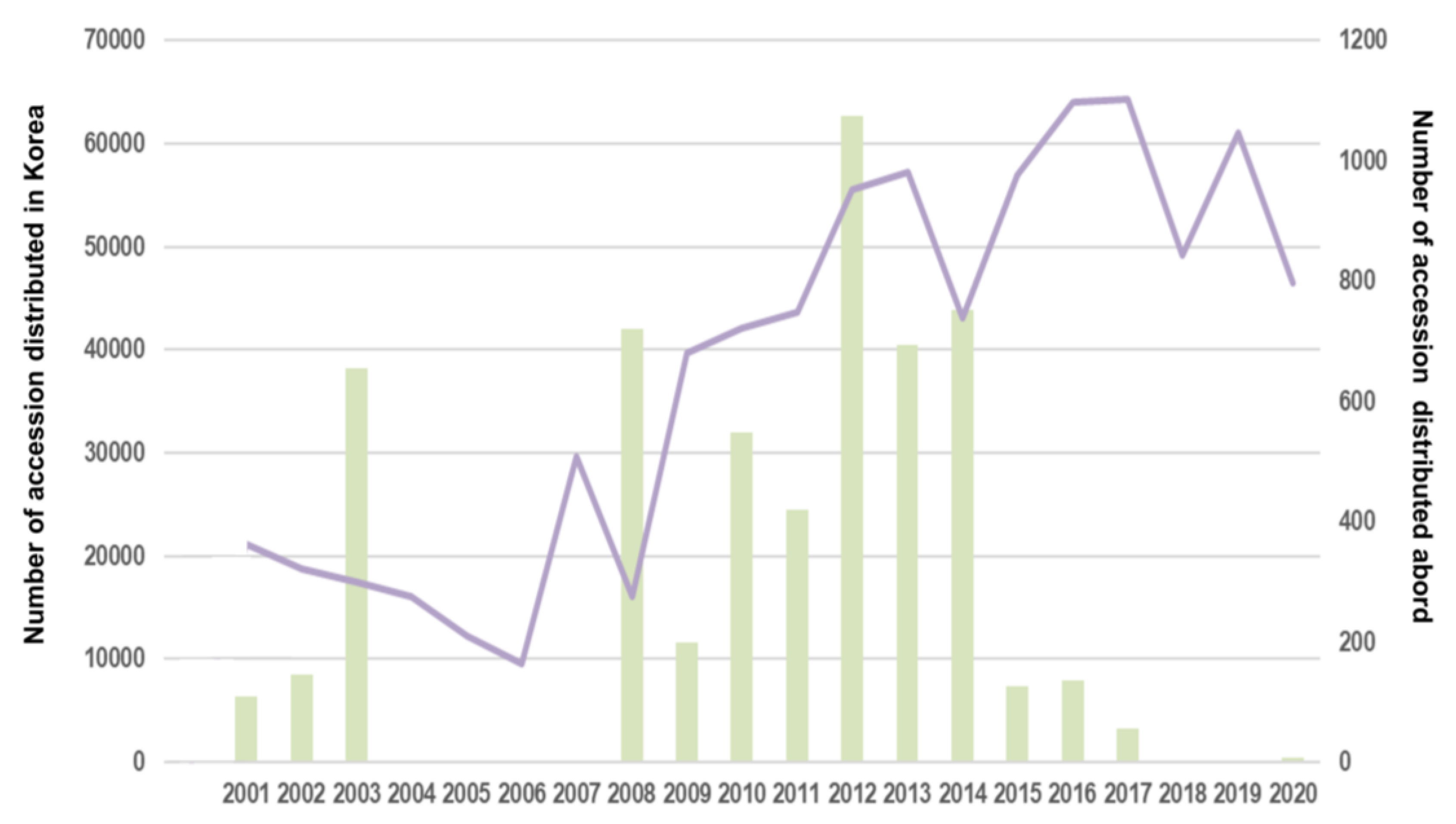

3. RDA-Genebank`s Distribution of Germplasm

4. Agronomic Traits and Passport Data

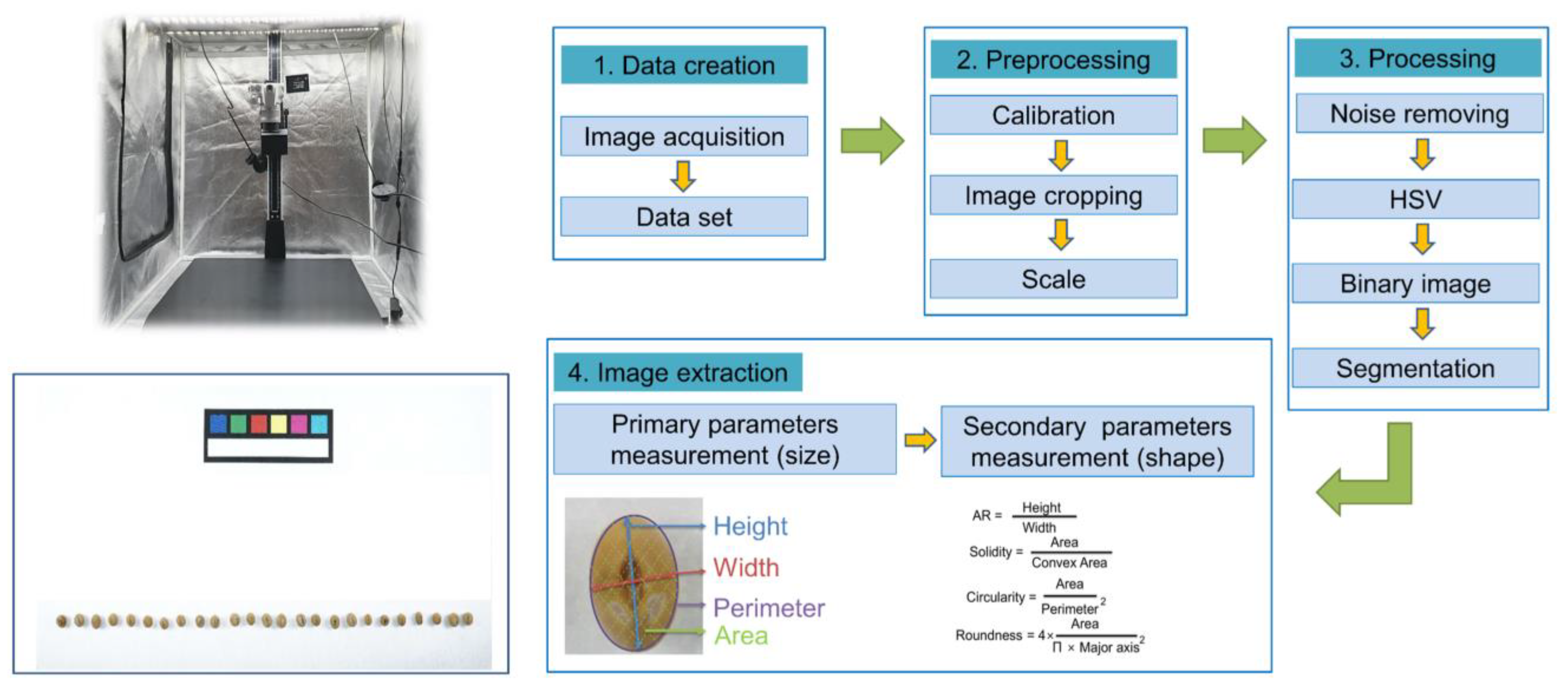

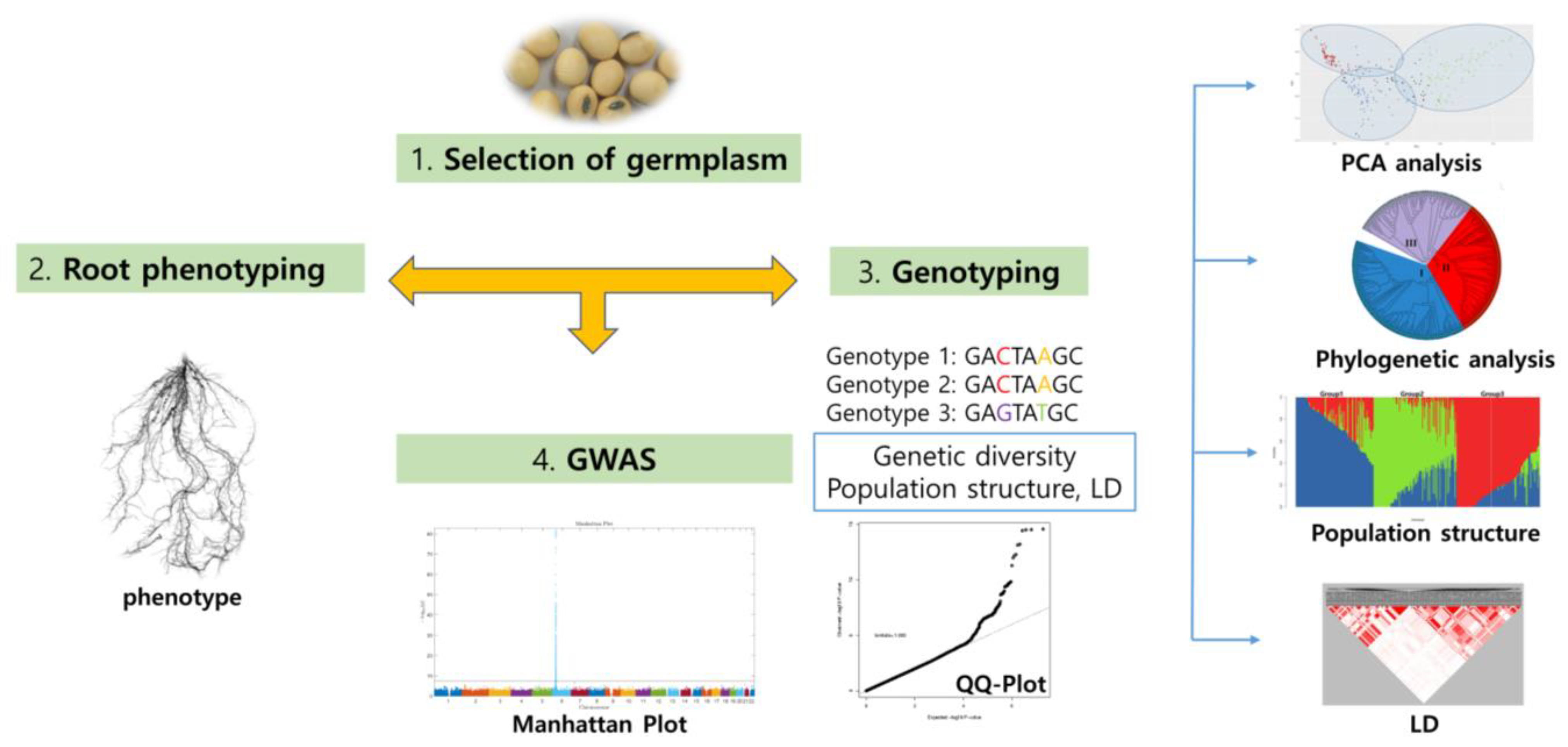

5. Digital Phenotyping of RDA-Genebank

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Genesys homepage. Available online: https://www.genesys-pgr.org/iso3166 (accessed on 0327).

- Loskutov, I.G. Vavilov Institute (VIR): historical aspects of international cooperation for plant genetic resources. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 2020, 67, 2237–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IndiaGene bank (ICAR-NBPGR) hompage. Available online: http://genebank.nbpgr.ernet.in/ (accessed on 0327).

- Oppermann, M.; Weise, S.; Dittmann, C.; Knüpffer, H. GBIS: the information system of the German Genebank. Database 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan gene bank(NARO) homepage. Available online: https://www.gene.affrc.go.jp/about-plant_en.php (accessed on 0327).

- Zhang, J.; Xin, X.; Yin, G.; Lu, X.; Chen, X. In vitro conservation and cryopreservation in national genebank of China. In Proceedings of the Proceeding of second international symposium on plant cryopreservation. Acta Hort; 2014; pp. 309–317. [Google Scholar]

- Weise, S.; Lohwasser, U.; Oppermann, M. Document or lose it—on the importance of information management for genetic resources conservation in genebanks. Plants 2020, 9, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Oh, M.; Bang, J.; Kim, D.; Kang, C.; Lee, B. Varietal difference of lignan contents and fatty acids composition in Korean sesame cultivars. Korean Journal of Crop science 2000, 45, 203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, M.S.; Lee, J.; Kim, C.Y.; Kang, J.H.; Cho, E.G.; Baek, H.J. DNA profiling and genetic diversity of Korean soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merrill) landraces by SSR markers. Euphytica 2009, 165, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-B.; Lee, C.-S.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, C.-H. Effects of crop rotation on the development of clubroot disease of Chinese cabbage caused by Plasmodiophora brassicae. The Plant Pathology Journal 2001, 17, 369.364–364. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, H.; Kim, S.; Wai, K.P.P.; Siddique, M.I.; Yoo, H.; Kim, B.-S. New sources of resistance to Phytophthora capsici in Capsicum spp. Horticulture, Environment, and Biotechnology 2014, 55, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElMasry, G.; Mandour, N.; Al-Rejaie, S.; Belin, E.; Rousseau, D. Recent applications of multispectral imaging in seed phenotyping and quality monitoring—An overview. Sensors 2019, 19, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juliano, B.O.; Villareal, C. Grain quality evaluation of world rices; Int. Rice Res. Inst.: 1993.

- Evers, A.; Cox, R.; Shaheedullah, M.; Withey, R. Predicting milling extraction rate by image analysis of wheat grains. Aspects of Applied Biology 1990, 417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Furbank, R.T.; Tester, M. Phenomics–technologies to relieve the phenotyping bottleneck. Trends in plant science 2011, 16, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minervini, M.; Scharr, H.; Tsaftaris, S.A. Image analysis: the new bottleneck in plant phenotyping [applications corner]. IEEE signal processing magazine 2015, 32, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Mukherjee, K.; Gangopadhyay, G. Image-analysis based on seed phenomics in sesame. Plant Breeding and Seed Science 2014, 68, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, P.J.; Bengough, A.G.; Grinev, D.; Schmidt, S.; Thomas, W.B.T.; Wojciechowski, T.; Young, I.M. Root phenomics of crops: opportunities and challenges. Functional Plant Biology 2009, 36, 922–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. A 3D print repository for plant phenomics. Plant Phenomics 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Feng, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Doonan, J.H.; Batchelor, W.D.; Xiong, L.; Yan, J. Crop phenomics and high-throughput phenotyping: past decades, current challenges, and future perspectives. Molecular Plant 2020, 13, 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Claussen, J.; Wörlein, N.; Eggert, A.; Fleury, D.; Garnett, T.; Gerth, S. Drought and heat stress tolerance screening in wheat using computed tomography. Plant Methods 2020, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Jo, J.W.; Wang, X.; Shin, M.-J.; Hur, O.S.; Ha, B.-K.; Hahn, B.-S. Diversity characterization of soybean germplasm seeds using image analysis. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-M.; Yoon, H.; Shin, M.-J.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S.; Hur, O.S.; Ro, N.Y.; Ko, H.-C.; Yi, J.; Lee, S.H. Differences in cotyledon color and harvest period affect the contents of major isoflavones and anthocyanins in black soybeans. Plant Breeding and Biotechnology 2021, 9, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Subramanian, P.; Hahn, B.-S.; Ha, B.-K. High-Throughput Phenotypic Characterization and Diversity Analysis of Soybean Roots (Glycine max L.). Plants 2022, 11, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, P.; Abdullah, J.S.; Kim, J.; Chung, Y.-S.; Kim, S.-H.; Hamayun, M.; Kim, Y. Investigation of root morphological traits using 2D-imaging among diverse soybeans (Glycine max L.). Plants 2021, 10, 2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayade, R.; Kim, S.-H.; Tripathi, P.; Choi, Y.-D.; Yoon, J.-B.; Kim, Y.-H. High-Throughput Root Imaging Analysis Reveals Wide Variation in Root Morphology of Wild Adzuki bean (Vigna angularis) Accessions. Plants 2022, 11, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, R.; Corke, F.; Doonan, J.H. Automated estimation of tiller number in wheat by ribbon detection. Machine Vision and Applications 2016, 27, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, T.; Chapman, S.; Holland, E.; Rebetzke, G.; Guo, Y.; Zheng, B. Dynamic quantification of canopy structure to characterize early plant vigour in wheat genotypes. Journal of Experimental Botany 2016, 67, 4523–4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genaev, M.A.; Komyshev, E.G.; Smirnov, N.V.; Kruchinina, Y.V.; Goncharov, N.P.; Afonnikov, D.A. Morphometry of the wheat spike by analyzing 2D images. Agronomy 2019, 9, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Guo, W.; Ninomiya, S. Node detection and internode length estimation of tomato seedlings based on image analysis and machine learning. Sensors 2016, 16, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Meacham-Hensold, K.; Guan, K.; Bernacchi, C.J. Hyperspectral leaf reflectance as proxy for photosynthetic capacities: an ensemble approach based on multiple machine learning algorithms. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yendrek, C.R.; Tomaz, T.; Montes, C.M.; Cao, Y.; Morse, A.M.; Brown, P.J.; McIntyre, L.M.; Leakey, A.D.; Ainsworth, E.A. High-throughput phenotyping of maize leaf physiological and biochemical traits using hyperspectral reflectance. Plant physiology 2017, 173, 614–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Perez, V.; Molero, G.; Serbin, S.P.; Condon, A.G.; Reynolds, M.P.; Furbank, R.T.; Evans, J.R. Hyperspectral reflectance as a tool to measure biochemical and physiological traits in wheat. Journal of Experimental Botany 2018, 69, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golzarian, M.R.; Frick, R.A.; Rajendran, K.; Berger, B.; Roy, S.; Tester, M.; Lun, D.S. Accurate inference of shoot biomass from high-throughput images of cereal plants. Plant methods 2011, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsi, R.H.; den Bakker, H.C.; Wiedmann, M. Listeria monocytogenes lineages: genomics, evolution, ecology, and phenotypic characteristics. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2011, 301, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, K.; Morinaka, Y.; Wang, F.; Huang, P.; Takehara, S.; Hirai, T.; Ito, A.; Koketsu, E.; Kawamura, M.; Kotake, K. GWAS with principal component analysis identifies a gene comprehensively controlling rice architecture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 21262–21267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Tang, J.; Han, B.; Huang, X. Advances in genome-wide association studies of complex traits in rice. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2020, 133, 1415–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-H.; Tayade, R.; Kang, B.-H.; Hahn, B.-S.; Ha, B.-K.; Kim, Y.-H. Genome-Wide Association Studies of Seven Root Traits in Soybean (Glycine max L.) Landraces. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weckwerth, W.; Ghatak, A.; Bellaire, A.; Chaturvedi, P.; Varshney, R.K. PANOMICS meets germplasm. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2020, 18, 1507–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).