1. Introduction

The major challenge for the commercialization of solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) is to reduce their operating temperature to an intermediate temperature (IT) range of 600-750 °C while maintaining the cell performance comparable with those of high-temperature devices [

1]. An increase in the ohmic resistance of an electrolyte membrane with a decrease in operating temperatures is the main problem for achieving the set goals of maintaining a high performance of IT- SOFCs. Alternative electrolytes having higher ionic conductivity than conventional stabilized zirconia have therefore become increasingly attractive for use in IT-SOFC [

2,

3]. To date, most studies on electrolytes possessing satisfactory oxygen ion conductivity at decreased temperatures have been focused on oxide materials with cubic fluorite structures, such as doped CeO

2 [

4,

5] and Bi

2O

3 [

6,

7]. Nevertheless, despite high ionic conductivity, which is very attractive for designing IT-SOFCs, these electrolytes, along with the advantages over traditional electrolytes based on zirconium dioxide, have a number of disadvantages.

CeO

2-based materials are thermodynamically stable in a wide range of temperatures, in the presence of water vapor, hydrocarbons and hazardous gases, chemically compatible with a wide range of oxide electrodes. One of the major problems of using CeO

2 electrolytes as SOFCs’ membranes is that at low partial pressures of oxygen, partial reduction of cerium Сe

4+→Ce

3+ occurs, which leads to the appearance of electronic conductivity in the material and can cause internal short circuit in the SOFC, resulting in reduction of open circuit voltage (OCV) and cell power, as well as fuel utilization efficiency [

5]. As a solution to the problem of internal circuiting in CeO

2 electrolytes, the formation of blocking layers on the anode side based on yttria-stabilized zirconia or barium cerate-zirconate is used [

8]. However, due to their lower ionic conductivity compared to electrolytes based on cerium dioxide, the introduction of such blocking layers may cause a decrease in the overall conductivity of the electrolyte membrane [

9]. In this regard, the most promising technological decision is to use a more conductive electrolyte for the blocking layer compared to CeO

2, such as stabilized Bi

2O

3 electrolytes [

10,

11].

The use of bismuth oxide as a solid electrolyte is limited by its thermodynamic instability under reducing conditions, namely, the oxide is reduced to metallic bismuth at

pO2<10

-13 atm [

12]. Improving the thermodynamic stability of Bi

2O

3 is achieved by doping it, for example, with Er or Y, which also makes it possible to increase the ionic conductivity [

13]. The formation of blocking layers of doped bismuth oxide on the cathode side of a doped ceria electrolyte is aimed at reducing the internal leakage current in the cell, on the other hand, the main ceria electrolyte will prevent the reduction of bismuth oxide by eliminating its contact with the reducing atmosphere. The studies on the effect of doped Bi

2O

3- based blocking layer on the performance ceria electrolyte-supported SOFCs showed the possibility to improve the maximum power density (MPD), however, the growth in OCV was less significant than expected and achieved at the blocking layer thickness no less than 30 μm [

14,

15]. The low effect on the OCV value can be explained by insufficient density of Bi-containing blocking layers, which is strongly influenced by the deposition method [

16]. The highest OCV for the cell with a Sm-doped (SDC) 1 mm thick electrolyte in the range of 1.006 – 0.900 V at 500 – 800 °C was reached by using a Bi

1.6Er

0.4O

3 cathode barrier layer (30 μm) obtained by dip coating [

16]. Among other methods used for the deposition of doped-Bi

2O

3 coatings are screen-printing [

15,

17,

18], magnetron sputtering [

19], and pulsed laser deposition (PLD) [

20].

The method of electrophoretic deposition (EPD) is promising for the formation various barrier layers, since this method ensures rapid formation of coatings of complex chemical compositions on substrates of different shapes (flat, tubular) with a reproducible coating thickness. The advantage of the EPD method is the simplicity of its technological implementation and scalability [

21,

22,

23]. The application of the EPD method is associated with the preparation of suspensions of the powder materials of various morphology and dispersion. The movement and deposition of powder particles in suspension on the substrate occurs under the influence of an external electric field, which is accompanied by the formation of a coating, which is subsequently subjected to drying and high-temperature sintering. To the best of our knowledge, there is a few published studies on EPD of Bi

2O

3 [

24,

25] and BiVO

4 [

26,

27] coatings for photo-electrochemical cells and photocatalytic applications. Нowever, preparation stable suspensions based on doped Bi

2O

3 with following electrophoretic deposition on non-conductive dense electrolyte substrates are not covered topics. In the present work, we have for the first time carried out the formation of a coating based on erbium-doped bismuth oxide Bi

1.6Er

0.4O

3 (EDB) on SDC solid electrolyte by the EPD method. We have studied the electrokinetic properties of EDB suspensions in a non-aqueous dispersion medium, the features of the formation and sintering of EDB coatings and their morphology, and also studied the characteristics of the Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt single cell in order to determine the effect of the EDB blocking layer on the OCV values.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of the Electrolytes

Powders of Bi

1.60Er

0.4O

3 (EDB) were synthesized by the Solution Combustion Synthesis (SCS). Erbium oxide (Er

2O

3) (99.90% purity, Sigma Aldrich), bismuth nitrate [Bi(NO

3)

3*5H

2O] (98.00% purity Reidel chemicals), glycine [C

2H

5NO

2] (AMK Ltd., Russia) and citric acid [C

6H

8O

7] (>98% purity, Weifang Ensigh Industry Co. Ltd., China) were used as the starting raw materials. Aqueous solution of metal nitrates in distilled water was mixed in stoichiometric ratio. An appropriate amount of glycine and citric acid (as fuel and complexing agent) was then added to the mixed nitrate solution. The nitrates acted as oxidizer in the mixed solution. The molar ratio of fuel to nitrate was set at 1.4:1 (fuel enrichment range) to ensure complete complexation of Bi and for smooth and controlled combustion of the mixed solution of bismuth and erbium nitrates. Also increasing the amount of fuel above stoichiometric (φ=1) leads to an increase in the amount of gas-phase product, which is an important factor in controlling the product specific surface area [

28]. The ratio of glycine and citric acid was 1:1. The mixed solution was heated on a hotplate under stirring to form a gel, which was further heated until combustion occurred. The foam-like powder obtained after combustion was crushed and calcined at 600 °C for 5 h to remove residual organics. After that, the powder was calcined at 700 °C for 5 h for subsequent phase analysis.

The Ce0.8Sm0.2O1.9 (SDC) powder for the supporting electrolyte substrates was fabricated by a solid-state reaction method using CeO2 (99.9 % wt) and Sm2O3 (99.9 % wt) as the starting reagents. The reagents were mixed in a PM 100 planetary mill (Retsch, St. Petersburg, Russia) in ethyl alcohol medium using plastic drums and stainless-steel grinding bodies, dried and then calcined in alumina crucibles at 950 °C (10 h) and 1050 °C (10 h) with intermediate ball-milling for 1 hour. After the final calcination step the powder was ball-milled for 1 h, dried and dry-pressed into disks at 300 MPa. The disks were then sintered at 1600 °С, 3 h. To perform XRD characterization, the SDC sintered disk was crashed.

The XRD characterization of the obtained materials was performed using an XRD-7000 diffractometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) in a CuKα1 radiation in the 25 ≤ 2θ ≤ 80° angle range with a scanning step of Δ(2θ) = 0.02° and a fixed time of 5 s at each point. The parameters of the crystal structure of the obtained materials were refined using FullProf Suite software [

29]. The specific surface area of the EDB powder used for the suspension preparation was determined using a SORBI N 4.1 Instrument (Meta, Novosibirsk, Russia). The morphology of the EDB powder was investigated using a JSM-6390 LA scanning electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

2.2. Preparation of the Suspensions Based on the Electrolyte Materials and Their Characterization

Suspensions based on EDB powder with a concentration of 10 g/L were prepared in a mixed dispersion medium of isopropanol/acetylacetone (70/30 vol.%), as well as in an isopropanol medium with the addition of polyethyleneimine (PEI, 0.26 g/L) and acetylacetone (0.15 g/L). EDB suspensions were sonicated using an ultrasonic bath UZV-13/150-TH (Reltec, Yekaterinburg, Russia) at a generator power of 210 W and an operating frequency of 22 kHz for 125 min at room temperature. The electrokinetic zeta potential and pH in the as-prepared suspensions were measured by the electroacoustic method using a DT-300 analyzer (Dispersion Technology, Lakewood, USA).

2.3. Electrophoretic Deposition of the Barrier Electrolyte Layers on the SDC Substrates and Their Characterization

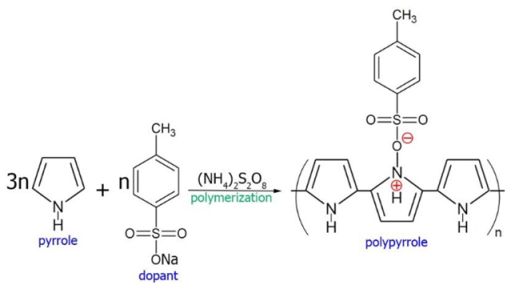

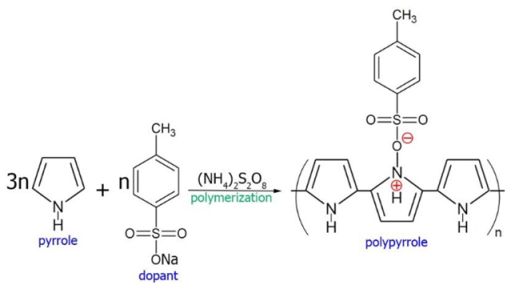

Electrophoretic deposition was performed using a specialized computerized experimental setup (Institute of Electrophysics, UB RAS, Yekaterinburg, Russia) with vertically arranged electrodes. The SDC supporting electrolyte disks were polished using a diamond disk to 550 μm in thickness and 13 mm in diameter. The substrates were cleaned in the ultrasonic bath for 10 min and calcined at 900 °C for 1 hour to eliminate surface contamination. A conductive polymer film of polypyrrole (PPy) was synthesized on the surface of the SDC substrate by chemical polymerization of pyrrole in an aqueous solution of ammonium persulfate served as an oxidizing agent (98%, 0.03 M), sodium salt of p-toluenesulfonic acid as a dopant (97.5%, 0.03 M), and pyrrole monomer (98%, 0.03 M) [

30]. To perform the EPD process, the SDC substrate with the deposited PPy conductive polymer film was placed on the EPD cell cathode electrode at the distance of 10 mm from the stainless-steel counter electrode, 12 mm in diameter. The deposition was performed in the constant voltage mode, current strength during the deposition process was controlled using an Intelligent Digital Multimeter UNI-T UT71E (Uni-Trend Technology, Guangdong, China). The morphology of the surface of the deposited layers was examined using an ST-VS-520 optical microscope (Yekaterinburg, Russia). The microstructure and element composition of the deposited films were studied by means of a JSM-6390 LA scanning electron microscope (JEOL, Japan) equipped with a system of the energy-dispersion X-ray microanalysis (EDX).

2.4. Single Cell Fabrication and Electrochemical Characterization

To study the effect of the EDB blocking layer on the OCV values, the Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt single cell was fabricated. Platinum electrodes with an effective area of approximately 0.3 cm2 were paint-brushed symmetrically on the both sides SDC electrolyte disks with the deposited and sintered EDB barrier coating. The electrodes were sintered at 900 °C for 2 h. To reduce polarization resistance of the electrodes, they were activated through the impregnation by the ethyl alcohol solution of Pr(NO3)3 (99.9% wt) (cathode side) and water solution of Ce(NO3)3 (99.9% wt) (anode side). Nitrate decomposition was performed at 600 °С, 2 h, with a rate of heating/cooling of 100 °C/h.

The measuring cell consisted of the YSZ tube with deposited Pt electrodes served as electrochemical pump and sensor. The Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt cell was fixed on the top of the measuring YSZ cell, placing the Pt anode activated with Ce inside and the Pr cathode activated with Pr outside the YSZ tube, respectively. The sample was fixed fist using Aremco Ceramabond™ 571 (Aremco Products Inc., USA) and then adhered tightly to the tube using a high-temperature sealant by heating up to 930 °C, holding time of 10 min, with a heating/cooling rate of 150°/h. The electrochemical study was performed using a B2901A precision source/measure unit (Keysight, Santa Rosa, USA). The spectra under the OCV conditions were collected using a Parstat 3000A potentiostat/galvanostat (Ametek Scientific Instruments, Newark, USA) at 30 mV in a frequency range of 2MHz – 0.1 Hz, 30 points per decade. Z-View 2 software was used to fit the obtained spectra.

To start the measurements, the cell was heated up to 600 °С and then the oxidizing atmosphere in the anode channel (inside the tube) was gradually replaced with argon and then with humidified hydrogen (3% H

2O, 5 L/h flow rate). The air was pumped to the cathode side at a rate of 5.7 L/h After the establishment the necessary atmosphere in the anode channel, the EMF measures by the electrochemical sensor placed on the YSZ-based measuring cell at 600 °С was equal to 1120 mV characteristic for the YSZ electrolyte [

31]. The measurements were carried out at 600 - 850°C by sequential recording the OCV values on the Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt cell, the cell impedance spectrum under OCV conditions, and the cell volt-ampere characteristics. The polarization and ohmic (IR) resistance of the cell was measured by the current interruption method using an RTM3004 oscillograph (Rohde&Schwarz, Munich, Germany).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of the Electrolyte Powder Materials

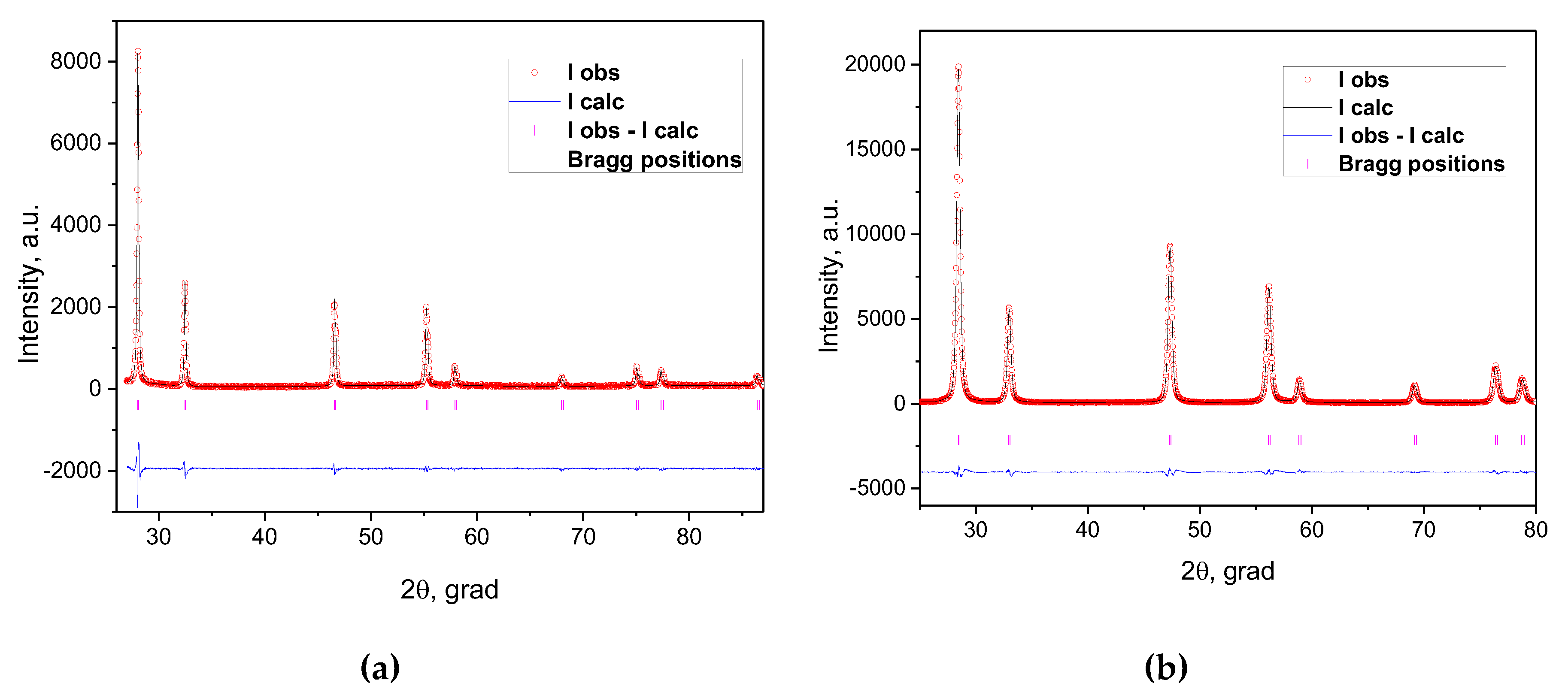

The results of the XRD characterization of the EDB and SDC electrolyte materials are represented in

Figure 1. The materials were single phase and exhibited a cubic type structure (

Table 1) with the unit cell parameters close to those presented in literature [

32,

33,

34].

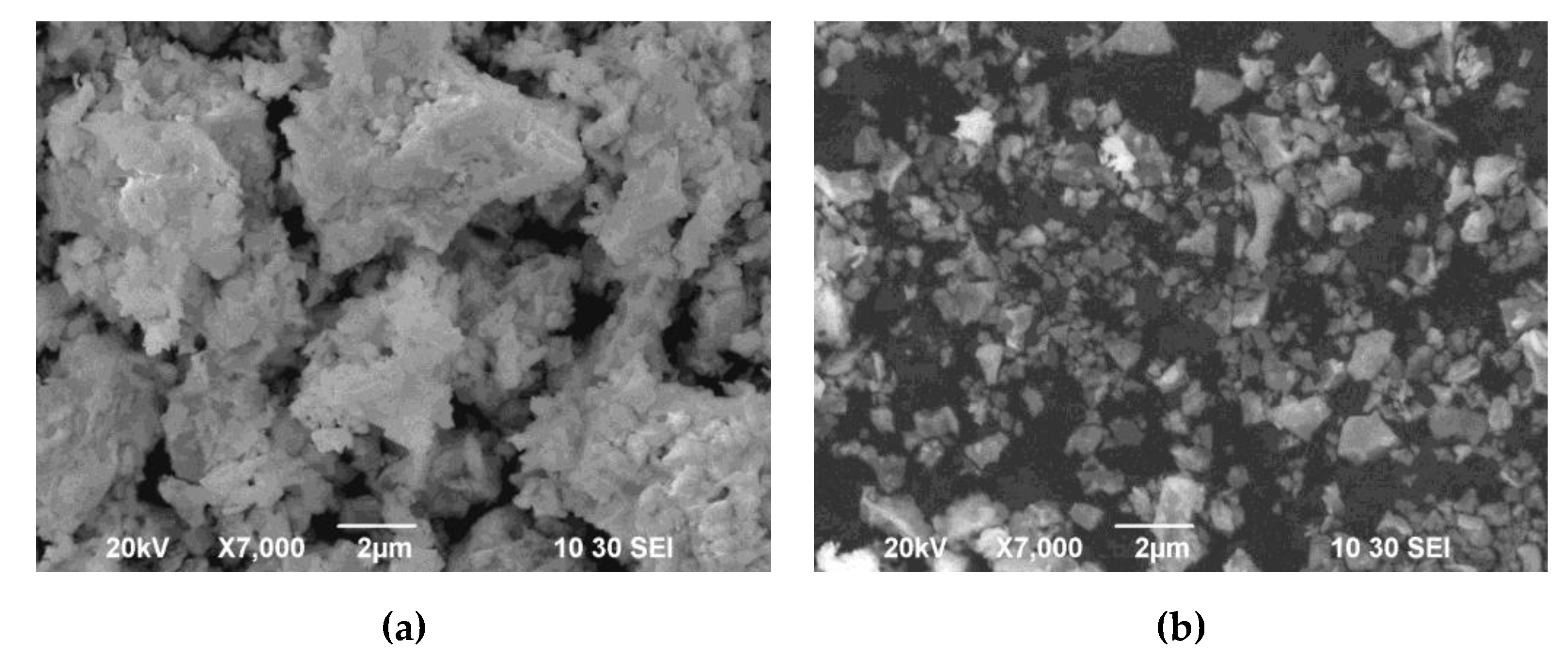

The powder after synthesis is characterized by the formation of large agglomerates up to 10 µm in size, consisting of irregularly shaped submicron particles (

Figure 2a). Along with the presence of agglomerates, the EDB powder was also characterized by the presence of individual particles with a size of 0.1 μm or more (

Figure 2b). The morphological inhomogeneity of the powder can lead to an uneven distribution of electrolyte powder particles over the substrate surface and subsequent multidirectional sintering in different parts of the surface during the formation of the EDB electrolyte layer. The crystallite size of the powder calcined at 700°C, determined by the Scherrer formula, was about 175 nm. The powder was additionally ball-milled for 1 hour in ethanol medium. After that the specific surface area of the EDB powder reached 3 m

2/g with an average particle size of 222 nm calculated according to [

35].

3.2. Preparation of Suspensions for EPD and Study of Kinetic Properties

The electrokinetic properties of suspensions of the EDB powder (10 g/L) in isopropanol/acetylacetone (70/30 vol.%) dispersion medium were studied after ultrasonic treatment (UST) for 5-125 min, the results are presented in

Table 2. A slight increase of zeta potential up to +20 mV during ultrasonic treatment for 125 min was noted, while pH shifted from 6.8 to 6.2, which characterizes the change in the ionic composition of the suspension due to improved solvation of particles by the dispersion medium. In the course of the experiments, another variant of the composition of the dispersion medium for the preparation of the EDB suspension was used - in isopropanol with the addition of polyethyleneimine (PEI, 0.26 g/L) and acetylacetone (0.15 g/L). The preparation of the EDB suspension was carried out in the following sequence. First, the EDB powder was introduced into an isopropanol medium with the addition of PEI (0.26 g/L) and UST was performed for 125 min. After that the measured zeta potential value was +10 mV at pH=11.0. However, in a suspension of EDB in an isopropanol medium with the addition of PEI the deposition process did not occur. On the second step of the preparation the resulting suspension was further modified by adding a small amount of acetylacetone (0.15 g/L). The amount of addition of acetylacetone as a dispersant was calculated the specific surface of the EDB powder, namely in the amount of 5 mg/m

2. Principles of introducing acetylacetone as a dispersant were described in our recent study [

36]. After the addition of acetylacetone (0.15 g/L) to the suspension of EDB in isopropanol with PEI and UST for 125 min, the zeta potential and pH values were +9 mV and 10.5, respectively. Despite the addition of acetylacetone had no significant effect on the value of the zeta potential and pH, the modification of the EDB suspension with the addition of acetylacetone dispersant made it possible to carry out the EPD process.

3.3. EPD from the EDB Suspensions on a Model Ni-Foil Substrate

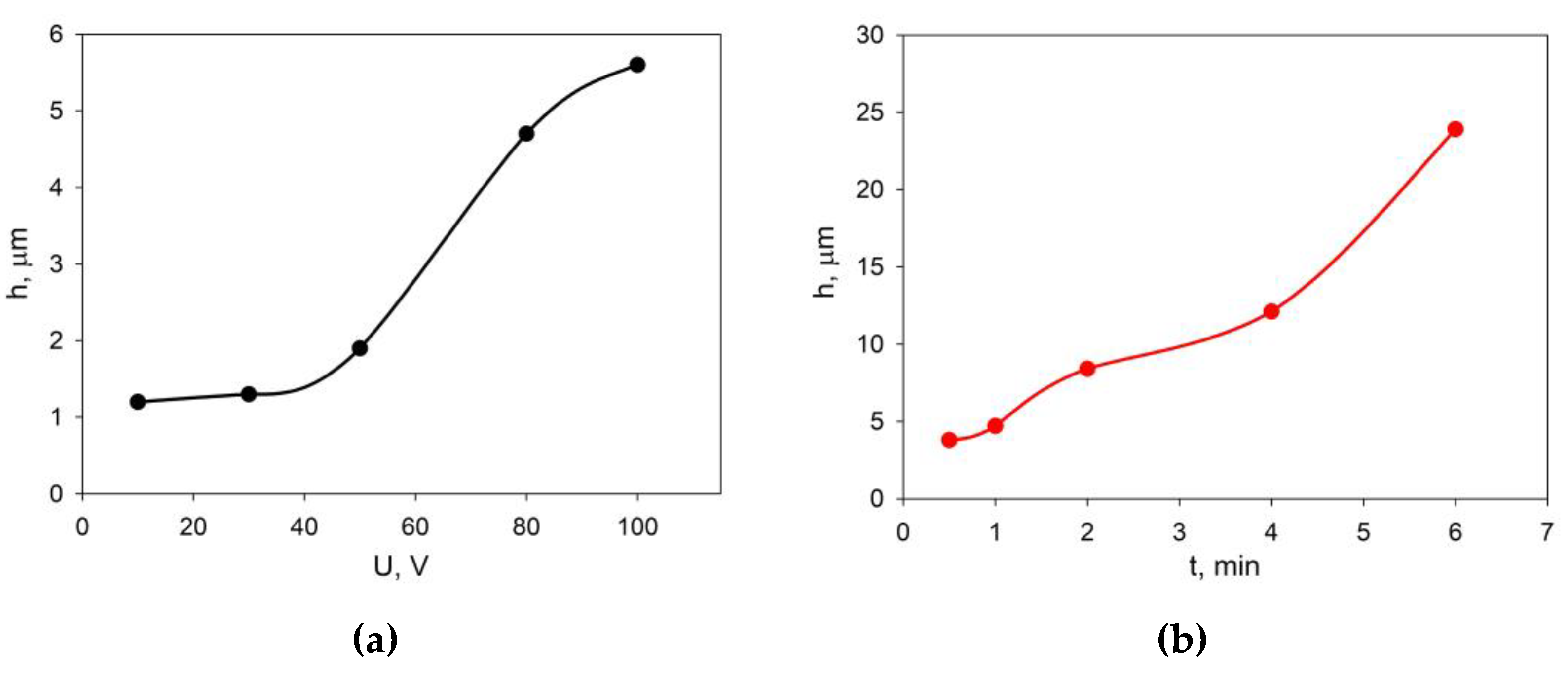

The selection of EPD modes was carried out on the basis of preliminary experiments on the deposition of the EDB powder from the prepared suspension in the isopropanol/acetylacetone 70/30 vol.% medium on a model electrode (Ni foil). The dependences of the EDB coating thickness on voltage at a fixed deposition time (1 min), as well as at a constant voltage of 80 V and various deposition times are shown in

Figure 3. A steady increase in the thickness of the EDB coating was observed in the voltage range of 50 - 80 V (

Figure 3a). The dependence of the coating thickness on time (

Figure 3b) was close to linear.

A continuous EDB coating on the model substrate was formed at a voltage of 80 - 100 V (

Figure 4a), while at lower voltages an inhomogeneous network coating appeared (

Figure 4b). According to the obtained results, for the following deposition on the SDC substrate the EPD mode U=80 V and t=1 min was chosen to obtain a continuous EDB coating with a thickness of 5 µm. The deposition current was ~ 0.1 mA.

The same scheme was used to study the effect of EPD modes on the coating thickness on a model electrode (Ni-foil) deposited from the EDB suspension in isopropanol medium modified with PEI and acetylacetone. The results are shown in

Figure 5.

At a voltage of more than 80 V, the growth of the EDB coating thickness was accelerated (

Figure 5a), an increase in the deposition time of more than 4 minutes lead to a slowdown in the growth of the coating thickness (

Figure 5b). It was established that to obtain a continuous EDB coating, the deposition must be carried out at a voltage of at least 80 V, and to obtain a thickness of 5 μm, the deposition time must be ~ 2 min (

Figure 6a). Lower voltage and deposition time (e.g. 30 V, 1 min) resulted in a non-uniform coating structure (

Figure 6b). Based on the results obtained, for the following experiments the deposition mode of U = 80 V, t = 2 min was chosen to obtain a 5 μm thick EDB coating from a suspension in isopropanol with PEI and acetylacetone additives. The deposition current was 0.1 mA.

3.4. Formation of EDB Coatings on the Dense SDC Electrolyte Substrates

The implementation of the EPD method is related to the need to use a conductive substrate. EPD on non-conductive dense (solid state electrolyte membranes) or low-porous (NiO-based cermet anodes) substrates is possible by creating a conductive sublayer on their surface [

37]. Creating the surface conductivity can be achieved by deposition of conductive graphite layers [

38,

39,

40], by metallizing the substrate surface with silver or platinum [

41], as well as deposition of polypyrrole (PPy) coating [

42]. The synthesis of PPy was chosen in this study. It is known, that PPy films exhibit conductivity sufficient for EPD (~500 S/m) and small thickness, which ensures the integrity of the electrolyte coating when burning PPy during sintering [

30,

43,

44]. In this work, a conductive PPy film was synthesized on the surface of the dense SDC substrate by the chemical polymerization of a pyrrole monomer using the reagents described in the Experimental part. The reagents were intensively mixed at 0 °C to obtain a homogeneous reaction mixture, into which immediately after the start of synthesis, the SDC substrate was immersed. Chemical polymerization of PPy occurs according to the reaction:

The thickness of the resulting PPy sublayer was approximately 0.5 μm. On the SDC substrate with a PPy sublayer, the EDB barrier coating was deposited from the isopropanol/acetylacetone-based suspension in the constant voltage mode U=80V, t=1 min (Sample EDB-1). The EDB layer was dried at room temperature in a Petri dish. The thickness of the dried coating was 6 µm. The coating was sintered at a temperature of 850°C for 5 hours in a closed crucible with the EDB powder being poured around the substrate. The EDB coating was uniform and crack-free in the central zone of the substrate (

Figure 7a), but breaks in the coating were observed along the edges of the SDC substrate. An attempt was made to close the formed defects in the coating by applying the second EDB layer by EDB. The deposition was carried out according to a similar scheme: a PPy layer was synthesized on the surface of the sintered EDB layer and the second EDB layer was deposited (U=80 V, t=1 min) followed by drying and sintering at a temperature of 850 °C, 5 hours. The total thickness of the EDB coating after two deposition-sintering cycles was 11 µm. However, as a result, the net of breaks was observed on the surface of the sintered coating (

Figure 7b).

Formation of cracks and breaks in the EDB coating of the EBD-1 sample may be associated with the effect of shrinkage of the EDB electrolyte material. However, individual fragments of the EDB electrolyte layer have a sintered structure, which allows us to conclude that the selected sintering temperature of 850 °C is sufficient. To reduce the degree of shrinkage and evaporation of the EDB electrolyte material during sintering, we carried out additional annealing of the initial EDB powder at a temperature of 650°C for 1 h. However, it was found that the annealed powder was not suitable for the preparation of a stable suspension in the isopropanol/acetylacetone 70/30 medium. vol.%, and subsequent deposition from such the suspension did not occur. Based on the results obtained, we changed the composition of the dispersion medium, namely, the powder was dispersed in an isopropanol medium with PEI and acetylacetone additives, as described in

Section 3.2. The following formation of the EDB barrier layer was carried out on an SDC substrate with a PPy sublayer with two deposition-sintering cycles (EDB-2 sample). In the first deposition cycle, a 5 μm thick EDB barrier layer was obtained in the EPD mode at a constant voltage of 80 V for 2 min, followed by drying and sintering at a temperature of 850 °C for 5 h. The surface SEM image of the resulting EDB coating is shown on

Figure 8. The EDB was not continuous, however, no breaks in the material and delamination of the coating was observed. The non-continuity of the coating was probably caused by shrinkage of the EDB electrolyte material during sintering. Therefore, to heal the defects, a second cycle of deposition-sintering was carried out.

The second EDB layer was deposited in the same EPD mode, and a total coating thickness of 12 µm was obtained. The obtained EDB barrier layer on the EDB-2 sample did not contain breaks and through cracks in the coating (

Figure 9). This sample was used for following fabrication of a single button cell and its electrochemical characterization.

3.5. Electrochemical Testing of the Single SOFCs with the Supporting SDC Electrolyte Membrane and EDB Electrolyte Coating Applied by EPD on the Cathode Side

For electrochemical characterization of the SDC electrolyte with an EDB barrier layer, a Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt cell was fabricated as described in

Section 2.4. The current-voltage characteristics were collected in the temperatures range of 600 - 850°C and the MPD values were calculated. Additionally, the polarization and ohmic (IR) resistance of the cell was measured by the current interruption method. The results are shown in

Figure 10 a and

Figure 10 b, respectively. The main characteristic of the cell is the constant increase in the MPD values up to 850 °C, which is not characteristic for cells with supporting MIEC electrolytes. Usually the cell performance decreases at the temperatures higher than 800 °C due to reduction of ceria in the anode conditions, which becomes significant at such high temperatures [

5,

45]. The MPD values of 12.6, 58.9, 101.2, 187.3 and 293.2 mW cm

-2 at temperatures of 600, 700, 750, 800 and 850 °C, respectively. The obtained values are much higher than those obtained by Wachsman et al. in the cell with supporting SDC electrolyte with a Er-doped Bi

2O

3 barrier layer and Pt/Au electrodes (51 mW cm

-2 at 800 °C [

14]) due to the reduction of the total electrolyte thickness from 800 to 562 µm. The OCV values obtained in this study were in the range of 725 - 750 mV and were close to those obtained for the cells with doped Bi

2O

3 layers of the similar thickness deposited by dip-coating [

16]. It should be noted that the polarization resistance of Pt electrodes was quite high and exceeded the ohmic resistance contribution even at such the high temperatures as 750 °C. Due to the low sintering temperature established in this study for the EDB layer deposited by EPD, it would be preferable to use for future studies the composite electrodes with Bi

2O

3 additives with reduced sintering temperature developed in various studies [

46,

47], including our own [

48,

49], possessing excellent electrochemical activity at decreased temperatures (polarization resistance as low as 0.6 Ω cm

2 at 600 °C [

48]). It is important, as the electrode polarization influences not only the cell performance, but also the OCV value. Thus, the replacement of the model Pt cathodes used in this study would help further improve the cell performance.

To get information about the contributions from the electrolyte and the electrodes, the impedance of the cell was measured under air in both channels (designated as “Air”) and under the OCV conditions with air and wet hydrogen (3 % H

2O) in the cathode and anode channel, respectively (designated as “SOFC mode”). The typical spectra are presented in

Figure 11. Although the impedance of the single cell was fairly complicated, the intercept of the impedance arc at the low frequency side with the real axis usually embodies the overall cell resistance (R), while the inflection point on the impedance spectra at the high frequency section represents the serial resistance (

Rhf), which includes the electrolyte ohmic resistance as the main component, as well as the electrode/electrolyte interface resistance and lateral resistance of the electrodes. Therefore, the difference between two intercepts represents the overall polarization resistance (

Rp) from both the anode and cathode.

Table 3 summarizes the cell ohmic resistance and the polarization resistance of the electrodes, as well as the overall percentage of the ohmic resistance to the total resistance at different temperatures. The electrolyte ohmic resistance accounted for 44 and 49 % of the total cell resistance at 850 °C, while it was only 3 and 16% at 600 °C. The presence of the electronic conductivity in the electrolyte in the SOFC mode facilitates electrode reactions, thus decreasing R

p. Thus, as we mentioned above, at decreased temperatures, the electrode polarization is the main deteriorating factor for the cell considered in this study. This agrees well with the data obtained by the current interruption method. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the R

p values of the cell presented in this study were significantly lower than those observed by Wachsman et al. [

14], which ranged 2 – 2.9 Ω cm

2 at 800 °С in dependence on the EBD thickness. This result is due to electrode activation used in the study.

The electrolyte conductivity was calculated from the EIS data as follows:

where h is the total electrolyte thickness, included the SDC supporting electrolyte and the EDB coating.

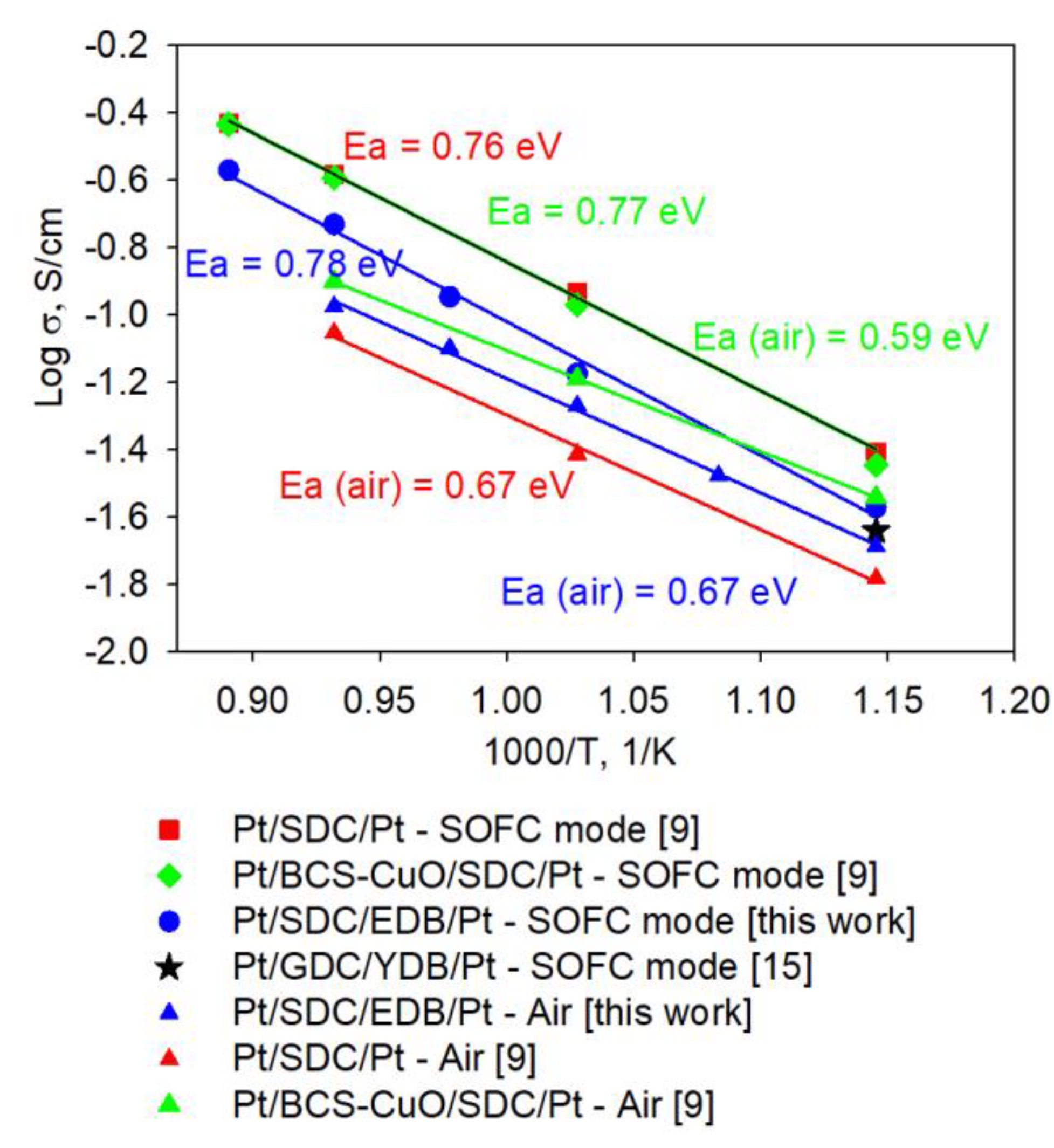

Figure 12 shows comparison of the Arrhenius dependence of the conductivity with those obtained for the SDC electrolytes without and with various barrier layers formed by EPD [

9,

15]. In the SOFC mode, the electrolyte conductivity is lower than that of SDC without electron-blocking layers and with BaCe

0.8Sm

0.2O

3+1 wt. % CuO (BCS-CuO) anode barrier layer. However, it is similar to that of SDC with Y-doped Bi

2O

3 coating, thus demonstrating superior effectiveness of Bi-based cathode to block electrons. In air, the SDC-EDB conductivity is higher than that of SDC electrolyte due to higher conductivity of EDB. And lower than that of BCS-CuO-SDC due to electronic conductivity in BCS-CuO electrolyte under air conditions. Deposition of EDB layer results in increasing the electrolyte conductivity, however it does not change the activation energy of conductivity (values are shown in

Figure 12 using the relevant colors).

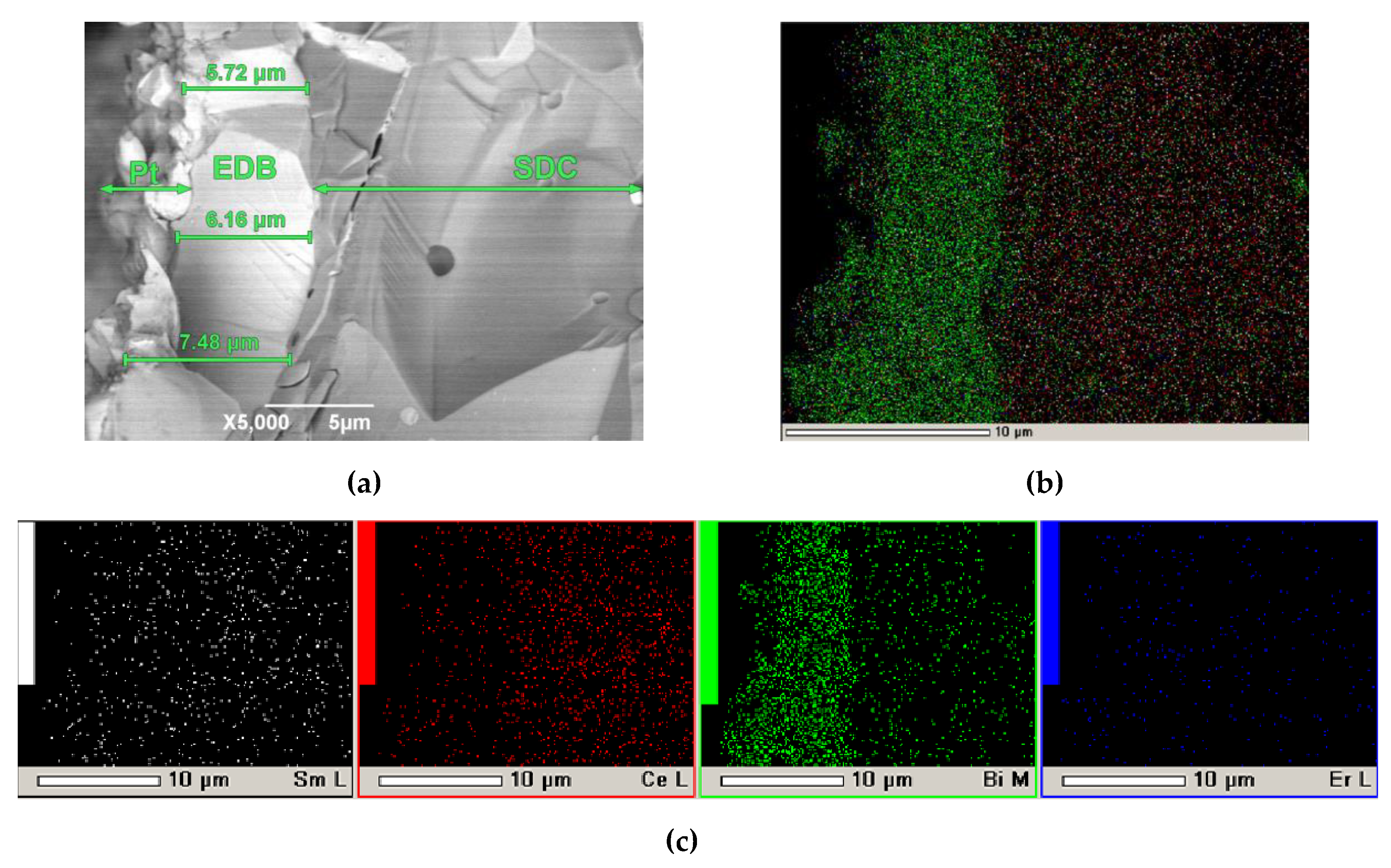

3.6. Microstructural Characterization of the SDC/EDB Electrolyte after Testing in the SOFC Mode

Figure 13 shows the SEM image of a Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt cell after testing in the SOFC mode. As shown in

Figure 13a, the EDB layer has a dense sintered structure, and the layer thickness is in the range of 5-7 µm, which is lower than it was calculated. Good adhesion between the EDB layer and the SDC substrate should be noted, which was maintained after three days of testing. In the bulk of the SDC substrate, diffusion of bismuth cations was observed. The inhomogeneity of the EDB layer may be related to its partial sevaporation during the sintering process as well as baking the Pt electrodes. However, the effect of the EDB layer manifested itself in the conductivity and power characteristics of the Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt cell (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). It should also be noted that the EDB layer obtained by EPD had superior density compared to Bi-containing coatings obtained screen-printing [

15,

20,

50]. In general, obtaining dense Bi-containing layers is a challenging task, which can mainly be realized by complicated physical methods such as PLD and magnetron sputtering [

20]. In this sense, the simple and inexpensive method of electrophoretic deposition offers undoubted advantages.

4. Conclusions

In the present work, the study was carried out on the electrophoretic formation of the EDB electron-blocking coating on the SDC supporting electrolyte using a sublayer of a conductive polymer, polypyrrole. A variant of preparing a suspension of EDB powder based on isopropanol with small additions of polyethyleneimine (PEI, 0.26 g/L) and acetylacetone (0.15 g/L) was proposed to obtain continuous EPD coatings and eliminate cracking of the coatings after sintering at a temperature of 850 °С, 5 h. Electrokinetic properties of suspensions based on the EDB powder were studied. A non-sintered electrophoretically deposited EDB coating 12 µm thick was obtained; after sintering (850°C, 5 h), the thickness of the EDB coating was 5–7 µm. The EDB coating was characterized by a dense sintered structure, the absence of pores, and good adhesion to the SDC substrate, including after testing in the SOFC mode for three days. The inhomogeneity of the thickness of the EDB coating after sintering was noted due to the partial evaporation of bismuth oxide. On the fabricated Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt SOFC cell, a monotonic increase in the maximum specific power with an increase in temperature up to 850 °C was noted. Therefore, the applied EDB electron-blocking layer decreased the effect of CeO2 reduction from the anode side at high temperatures on the cell performance. MPD values were 12.6, 58.9, 101.2, 187.3 and 293.2 mW cm-2 at temperatures of 600, 700, 750, 800 and 850 °C, respectively. The OCV values of the cell were not high, namely, they were in the range of 725–750 mV at temperatures of 600–850°C. We suppose that such low values are due to high electrode polarization and can be improved by using electrodes that are highly active at lower temperatures. Measurements of the Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt cell showed that the conductivity in SOFC mode decreased with respect to the Pt/SDC/Pt cell due to the blocking effect of the EDB layer. However, in air, the conductivity of the Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt cell was higher due to higher conductivity of the EBD layer. The results obtained in the framework of this study revealed, that the EPD method can be considered as a promising technology for the formation of barrier layers based on highly conductive doped bismuth oxide, such as in SOFC technology, as well as in other application fields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.K. and E.P.; methodology, E.K.; software, E.P.; validation, E.K., L.E. and E.P.; investigation, E.K. and L.E.; resources, L.E.; data curation, E.K., E.P.; writing—original draft preparation, E.K.; writing—review and editing, E.P.; visualization, E.K. and L.E.; supervision, E.P.; project administration, E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The XRD studies were performed using facilities of the Ural-M collective center (IMET UB RAS, Yekaterinburg, Russia). The authors are grateful to Sergey Pikalov (IMET UB RAS) and Elena Filonova (Ural Federal University, Yekaterinburg, Russia) for the XRD data treatment. SEM studies were performed using facilities of ISSC UB RAS shared access center (Yekaterinburg, Russia). The authors acknowledge Kirill Shubin (IHTE UB RAS, Yekaterinburg, Russia) for the electrochemical experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mendonça, C.; Ferreira, A.; Santos, D.M.F. Towards the Commercialization of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells: Recent Advances in Materials and Integration Strategies. Fuels 2021, 2, 393–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedhar, I.; Agarwal, B.; Goyal, P.; Singh, S.A. Recent Advances in Material and Performance Aspects of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 848, 113315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Ghosh, S.; Aich, S.; Roy, B. Low Temperature Solid Oxide Electrolytes (LT-SOE): A Review. J. Power Sources 2017, 339, 103–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunkumar, P.; Meena, M.; Babu, K.S. A Review on Cerium Oxide-Based Electrolytes for ITSOFC. Nanomater. Energy 2012, 1, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikalova, E.Yu.; Kalinina, E.G. Solid Oxide Fuel Cells Based on Ceramic Membranes with Mixed Conductivity: Improving Efficiency. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2021, 90, 703–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, A.M.; Larose, S.; Akbar, S.A. Bismuth Oxide-Based Solid Electrolytes for Fuel Cells. J. Mater. Sci. 1994, 29, 4135–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, I.; Jeong, S.J.; Yun, B.-H.; Lee, J.-W.; Lee, C.-W.; Jung, W.; Lee, K.T. Physically Driven Enhancement of the Stability of Bi2O3-Based Ionic Conductors via Grain Boundary Engineering. NPG Asia Mater. 2022, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shri Prakash, B.; Pavitra, R.; Senthil Kumar, S.; Aruna, S.T. Electrolyte Bi-Layering Strategy to Improve the Performance of an Intermediate Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cell: A Review. J. Power Sources 2018, 381, 136–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, E.G.; Pikalova, E.Yu. Electrophoretic Deposition of Dense Anode Barrier Layers of Doped ZrO2 and BaCeO3 on a Supporting Ce0.8Sm0.2O2-δ Solid Electrolyte: Problems and Search for Solutions in SOFC Technology. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy In press. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, Z.; Wei, K.; Wu, Y.; Khan, M.; Zheng, K.; Shen, S.; Wang, S. Review of Experimental and Modelling Developments for Ceria-Based Solid Oxide Fuel Cells Free from Internal Short Circuits. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsman, E.D.; Lee, K.T. Lowering the Temperature of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Science 2011, 334, 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, A.; Jaiswal, A.; Ren, Y.; Wachsman, E.D. Development of a New Ceria/Yttria-Ceria Double-Doped Bismuth Oxide Bilayer Electrolyte Low-Temperature SOFC with Higher Stability. Ionics 2019, 25, 3153–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concha-Balderrama, A.; Martinez-Rodriguez, H.A.; Rojas-George, G.; Esparza-Ponce, H.E.; Orozco-Carmona, V.; Pizá-Ruiz, P.; Bocanegra-Bernal, M.H.; Reyes-Rojas, A. Enhanced Ionic Transport and Compressive Residual Stress in Er-Doped Bi2O3 with Lower Er3+ Concentrations. J. Elec. Mater. 2018, 47, 5422–5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsman, E.D.; Jayaweera, P.; Jiang, N.; Lowe, D.M.; Pound, B.G. Stable High Conductivity Ceria/Bismuth Oxide Bilayered Electrolytes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1997, 144, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y.J. Development of YDB/GDC Composite Electrolyte For Low-Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. ECS Proc. Vol. 2005, 2005–07, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-Y.; Wachsman, E.D. Stable and High Conductivity Ceria/Bismuth Oxide Bilayer Electrolytes for Lower Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Ionics 2006, 12, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, N.; Ma, J.; Li, J.; Yan, D.; Chi, B.; Pu, J.; Li, J. High Performance Cathode-Unsintered Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Enhanced by Porous Bi1.6Er0.4O3 (ESB) Interlayer. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2018, 43, 12713–12719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.G.; Park, M.G.; Yoon, H.H.; Shul, Y.G. Application of GDC-YDB Bilayer and LSM-YDB Cathode for Intermediate Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. J. Electroceram. 2013, 31, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xia, C.; Zhao, F.; Chen, F. Thin Film Ceria–Bismuth Bilayer Electrolytes for Intermediate Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells with La0.85Sr0.15MnO3−δ–Y0.25Bi0.75O1.5 Cathodes. Matr. Res. Bull. 2010, 45, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.S.; Camaratta, M.A.; Pergolesi, D.; Lee, K.T.; Yoon, H.; Lee, B.W.; Jung, D.W.; Traversa, E.; Wachsman, E.D. Development of High Performance Ceria/Bismuth Oxide Bilayered Electrolyte SOFCs for Lower Temperature Operation. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2010, 157, B376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikalova, E.Yu.; Kalinina, E.G. Place of Electrophoretic Deposition among Thin-Film Methods Adapted to the Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Technology: A Short Review. Int. J. EQ 2019, 4, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikalova, E.Yu.; Kalinina, E.G. Electrophoretic Deposition in the Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Technology: Fundamentals and Recent Advances. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2019, 116, 109440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, E.G.; Pikalova, E.Yu. New Trends in the Development of Electrophoretic Deposition Method in the Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Technology: Theoretical Approaches, Experimental Solutions and Development Prospects. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2019, 88, 1179–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, X.; Lai, C.; Li, W.; Zhang, D.; Xiong, Z. Cathodic Electrophoretic Deposition of Bismuth Oxide (Bi2O3) Coatings and Their Photocatalytic Activities. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 331, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Guo, X. Remarkably Facile Preparation of Superhydrophobic Functionalized Bismuth Trioxide (Bi2O3) Coatings. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megnin, C. Electrophoretic deposition of BiVO₄ layers on FTO substrates for photo electro-chemical cells. Ceramics - Silikaty 2019, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahkandi, M.; Zargazi, M. New Water Based EPD Thin BiVO4 Film: Effective Photocatalytic Degradation of Amoxicillin Antibiotic. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 389, 121850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukasyan, A.S.; Epstein, P.; Dinka, P. Solution Combustion Synthesis of Nanomaterials. Proceed. Combust. Institute 2007, 31, 1789–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FullProf Suite Homepage. 2023. Available online: https://www.ill.eu/sites/fullprof/ (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Kalinina, E.; Shubin, K.; Pikalova, E. Electrophoretic Deposition and Characterization of the Doped BaCeO3 Barrier Layers on a Supporting Ce0.8Sm0.2O1.9 Solid-State Electrolyte. Membranes 2022, 12, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiodelli, G.; Malavasi, L. Electrochemical Open Circuit Voltage (OCV) Characterization of SOFC Materials. Ionics 2013, 19, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikalova, E.Yu.; Bamburov, V.G.; Murashkina, A.A.; Neuimin, A.D.; Demin, A.K.; Plaksin, S.V. Solid Electrolytes Based on CeO2 for Medium-Temperature Electrochemical Devices. Russ. J. Electrochem. 2011, 47, 690–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobaner, S.; Yilmaz, S. Electrical and Structural Properties of New Type Er and Yb Doped Bismuth Oxide Solid Electrolytes Synthesized by Pechini Method. J. Electroceram. 2021, 46, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasteh, S.; Maghsoudipour, A.; Alizadeh, M.; Nemati, A. Effect of Y2O3 and Er2O3 Co-Dopants on Phase Stabilization of Bismuth Oxide. Ceram. Int. 2011, 37, 3451–3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, S.A. Surface Area and Pore Volume of a System of Particles as a Function of Their Size and Packing. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 2009, 122, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, E.; Ivanov, M. The Electrophoretic Deposition of Nanopowders Based on Yttrium Oxide for Bulk Ceramics Fabrication. Inorganics 2022, 10, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, E.; Pikalova, E.; Ermakova, L.; Bogdanovich, N. Challenges of Formation of Thin-Film Solid Electrolyte Layers on Non-Conductive Substrates by Electrophoretic Deposition. Coatings 2021, 11, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosomi, T.; Matsuda, M.; Miyake, M. Electrophoretic Deposition for Fabrication of YSZ Electrolyte Film on Non-Conducting Porous NiO–YSZ Composite Substrate for Intermediate Temperature SOFC. J. Europ. Ceram. Soc. 2007, 27, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarian Borojeni, I.; Raissi, B.; Maghsoudipour, A.; Kazemzad, M.; Talebi, T. Fabrication of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFCs) Electrolytes by Electrophoretic Deposition (EPD) and Optimizing the Process. KEM 2015, 654, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, G.; Nguyen, N.T.K.; Rendtorff, N.M.; Sakka, Y.; Uchikoshi, T. Electrophoretic Deposition for Obtaining Dense Lanthanum Silicate Oxyapatite (LSO). Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 19283–19288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, E.G.; Pikalova, E.Yu. Formation of a Single- and Two-Layer Solid Electrolyte by Electrophoresis on Anodic Substrates Metalized with Silver or Platinum. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. 2022, 96, 2763–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.T.; Uchikoshi, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Suzuki, T.S.; Sugiyama, T.; Furuya, K.; Matsuda, M.; Sakka, Y.; Munakata, F. Fabrication of GDC/LSGM/GDC Tri-Layers on Polypyrrole-Coated NiO-YSZ by Electrophoretic Deposition for Anode-Supported SOFC. J. Ceram. Soc. Japan 2009, 117, 1246–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Basu, R.N. Electrophoretic Deposition of Zirconia Thin Film on Nonconducting Substrate for Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Application. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2014, 97, 3452–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchikoshi, T.; Furumi, S.; Shirahata, N.; Suzuki, T.S.; Sakka, Y. Conductive Polymer Coating on Nonconductive Ceramic Substrates for Use in the Electrophoretic Deposition Process. J Am. Ceram. Soc. 2008, 91, 1674–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, N.; Tanwar, K.; Suman, R.; Kumar, D.; Upadhyay, S.; Parkash, O. A Brief Review on Ceria Based Solid Electrolytes for Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 781, 984–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.C.; Chang, Y.-J.; Fung, K.-Z.; Haile, S. High Electrochemical Activity of Bi2O3-Based Composite SOFC Cathodes. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 2014, 51, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Yang, T.; Huang, K. In Situ Synthesis of a High-Performance Bismuth Oxide Based Composite Cathode for Low Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 2801–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikalova, E.; Bogdanovich, N.; Kolchugin, A.; Shubin, K.; Ermakova, L.; Eremeev, N.; Farlenkov, A.; Khrustov, A.; Filonova, E.; Sadykov, V. Development of Composite LaNi0.6Fe0.4O3-δ-Based Air Electrodes for Solid Oxide Fuel Cells with a Thin-Film Bilayer Electrolyte. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 16947–16964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovyev, A.A.; Shipilova, A.V.; Rabotkin, S.V.; Bogdanovich, N.M.; Pikalova, E.Y. Study of the Efficiency of Composite LaNi0.6Fe0.4O3-Based Cathodes in Intermediate-Temperature Anode-Supported SOFCs. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2023, S0360319923006948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y.J.; Chan, S.H. Anode-Supported SOFCs with Y2O3-Doped Bi2O3/Gd2O3-Doped CeO2 Composite Electrolyte Film. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2006, 9, A56–A59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Observed (points) and calculated (lines) XRD patterns for Bi1.60Er0.4O3 (a) and Ce0.8Sm0.2O1.9 (b)powders.

Figure 1.

Observed (points) and calculated (lines) XRD patterns for Bi1.60Er0.4O3 (a) and Ce0.8Sm0.2O1.9 (b)powders.

Figure 2.

Morphology of the EDB electrolyte powder (Tcalc = 700°C) (SEM image): agglomerates (a) and individual particles (b).

Figure 2.

Morphology of the EDB electrolyte powder (Tcalc = 700°C) (SEM image): agglomerates (a) and individual particles (b).

Figure 3.

Dependences of the thickness of the EDB coating obtained from the suspension in the isopropanol/acetylacetone 70/30 vol.% medium on the Ni-foil model electrode: (a) at a constant deposition time of 1 min and various voltages; (b) at a fixed voltage of 80 V and various deposition times.

Figure 3.

Dependences of the thickness of the EDB coating obtained from the suspension in the isopropanol/acetylacetone 70/30 vol.% medium on the Ni-foil model electrode: (a) at a constant deposition time of 1 min and various voltages; (b) at a fixed voltage of 80 V and various deposition times.

Figure 4.

Optical surface images of the dried EDB coatings obtained from a suspension in an isopropanol/acetylacetone 70/30 vol.% medium on a Ni-foil model electrode: (a) at a deposition time of 1 min and a voltage of 80 V; (b) at a deposition time of 1 min and at a voltage of 30 V.

Figure 4.

Optical surface images of the dried EDB coatings obtained from a suspension in an isopropanol/acetylacetone 70/30 vol.% medium on a Ni-foil model electrode: (a) at a deposition time of 1 min and a voltage of 80 V; (b) at a deposition time of 1 min and at a voltage of 30 V.

Figure 5.

Dependences of the EDB coating thickness, obtained from a suspension in isopropanol with the addition of PEI and acetylacetone, on a Ni-foil model electrode: (a) at a constant deposition time of 1 min and various voltages; (b) at a fixed voltage of 80 V and various deposition times.

Figure 5.

Dependences of the EDB coating thickness, obtained from a suspension in isopropanol with the addition of PEI and acetylacetone, on a Ni-foil model electrode: (a) at a constant deposition time of 1 min and various voltages; (b) at a fixed voltage of 80 V and various deposition times.

Figure 6.

The surface of dried EDB coatings obtained from a suspension in isopropanol with the addition of PEI and acetylacetone, on a Ni-foil model electrode: (a) U= 80 V, t = 2 min; (b) U = 30 V and t = 1 min.

Figure 6.

The surface of dried EDB coatings obtained from a suspension in isopropanol with the addition of PEI and acetylacetone, on a Ni-foil model electrode: (a) U= 80 V, t = 2 min; (b) U = 30 V and t = 1 min.

Figure 7.

Optical image of the surface of the sintered coating of the EDB electrolyte (sample EDB-1, Tsint=850°C, 5 h), obtained from a suspension in isopropanol/acetylacetone 70/30 vol.%, on a dense SDC substrate: (a) after EPВ and sintering the first layer 6 µm thick; (b) after the second cycle of deposition-sintering of the EDB coating with a total thickness of 11 μm.

Figure 7.

Optical image of the surface of the sintered coating of the EDB electrolyte (sample EDB-1, Tsint=850°C, 5 h), obtained from a suspension in isopropanol/acetylacetone 70/30 vol.%, on a dense SDC substrate: (a) after EPВ and sintering the first layer 6 µm thick; (b) after the second cycle of deposition-sintering of the EDB coating with a total thickness of 11 μm.

Figure 8.

SEM image of the surface of the EDB coating (first deposition-sintering cycle) on the SDC substrate (EDB-2 sample, Tsint=850°C, 5 h) obtained by EPD from an EDB suspension in isopropanol with PEI and acetylacetone additives: (a) surface, x500; (b) integral map of elements’ distribution; (c) individual element maps.

Figure 8.

SEM image of the surface of the EDB coating (first deposition-sintering cycle) on the SDC substrate (EDB-2 sample, Tsint=850°C, 5 h) obtained by EPD from an EDB suspension in isopropanol with PEI and acetylacetone additives: (a) surface, x500; (b) integral map of elements’ distribution; (c) individual element maps.

Figure 9.

SEM image of the surface of the final EDB coating (two deposition-sintering cycles) on the SDC substrate (EDB-2 sample, Tsint=850°C, 5 h) obtained by ESP from EDB suspension in isopropanol medium with PEI and acetylacetone additives: (a) surface, x300; (b) integral map of elements’ distribution; (c) individual element maps.

Figure 9.

SEM image of the surface of the final EDB coating (two deposition-sintering cycles) on the SDC substrate (EDB-2 sample, Tsint=850°C, 5 h) obtained by ESP from EDB suspension in isopropanol medium with PEI and acetylacetone additives: (a) surface, x300; (b) integral map of elements’ distribution; (c) individual element maps.

Figure 10.

Electrochemical characterization of the Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt electrolyte supported cell: (a) Volt-ampere characteristics and cell power density; b) Ohmic and polarization cell resistances measured by the current interruption method.

Figure 10.

Electrochemical characterization of the Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt electrolyte supported cell: (a) Volt-ampere characteristics and cell power density; b) Ohmic and polarization cell resistances measured by the current interruption method.

Figure 11.

Typical spectra collected for the Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt electrolyte supported cell collected in Aie and SOFC mode: (a) at 800 °C; b) at 700 °C.

Figure 11.

Typical spectra collected for the Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt electrolyte supported cell collected in Aie and SOFC mode: (a) at 800 °C; b) at 700 °C.

Figure 12.

Arrhenius dependences of the electrolyte conductivity calculated from EIS data for the cells with the SDC supporting electrolyte with/without electron-blocking layers.

Figure 12.

Arrhenius dependences of the electrolyte conductivity calculated from EIS data for the cells with the SDC supporting electrolyte with/without electron-blocking layers.

Figure 13.

SEM image of a Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt cell after testing in the SOFC mode: (a) cleavage, x 5000. On the left, the Pt layer is shown, which was the electrode (cathode) during measurements in the SOFC mode; (b) integrated map of elements; (c) individual maps of elements.

Figure 13.

SEM image of a Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt cell after testing in the SOFC mode: (a) cleavage, x 5000. On the left, the Pt layer is shown, which was the electrode (cathode) during measurements in the SOFC mode; (b) integrated map of elements; (c) individual maps of elements.

Table 1.

Structural characteristics of the EDB and SDC electrolyte materials.

Table 1.

Structural characteristics of the EDB and SDC electrolyte materials.

| Electrolyte Material |

Crystal Lattice Type,

Space Group |

Lattice Parameters,

Å |

| EDB |

cubic,

Fm-3m |

a = 5.4960(1) |

| SDC |

cubic,

Fm-3m |

а=5.4324(3) |

Table 2.

Electrokinetic properties of the EDB suspensions (10 g/L) in various dispersion media: isopropanol/acetylacetone (70/30 vol.%); isopropanol-PEI; isopropanol-PEI-HAcAc.

Table 2.

Electrokinetic properties of the EDB suspensions (10 g/L) in various dispersion media: isopropanol/acetylacetone (70/30 vol.%); isopropanol-PEI; isopropanol-PEI-HAcAc.

| Suspension |

UT, min |

Zeta Potential, mV (рН) |

| EDB isopropanol/acetylacetone 70/30 vol.% |

5

25

125 |

+16 (6.8)

+19 (6.6)

+20 (6.2) |

| EDB isopropanol-PEI |

125 |

+10 (11.0) |

| EDB isopropanol-PEI-HAcAc |

125 |

+9 (10.5) |

Table 3.

Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt cell characteristics calculated from the EIS data.

Table 3.

Pt/SDC/EDB/Pt cell characteristics calculated from the EIS data.

| Temperature |

air (anode)/ air (cathode) |

hydrogen (anode)/ air (cathode) |

Rhf,

Ω cm2

|

Rp,

Ω cm2

|

Rhf/(Rhf+Rp)*100, % |

Rhf,Ω cm2

|

Rp,Ω cm2

|

Rhf/(Rhf+Rp)*100, % |

| 850 |

|

|

|

0.21 |

0.15 |

58 |

| 800 |

0.49 |

0.67 |

44 |

0.30 |

0.31 |

49 |

| 750 |

0.70 |

1.27 |

36 |

0.49 |

0.78 |

39 |

| 700 |

1.04 |

3.41 |

23 |

0.83 |

1.96 |

30 |

| 650 |

1.68 |

20.95 |

7 |

|

|

|

| 600 |

2.72 |

95.93 |

3 |

2.08 |

12.09 |

16 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).