Submitted:

10 May 2023

Posted:

11 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

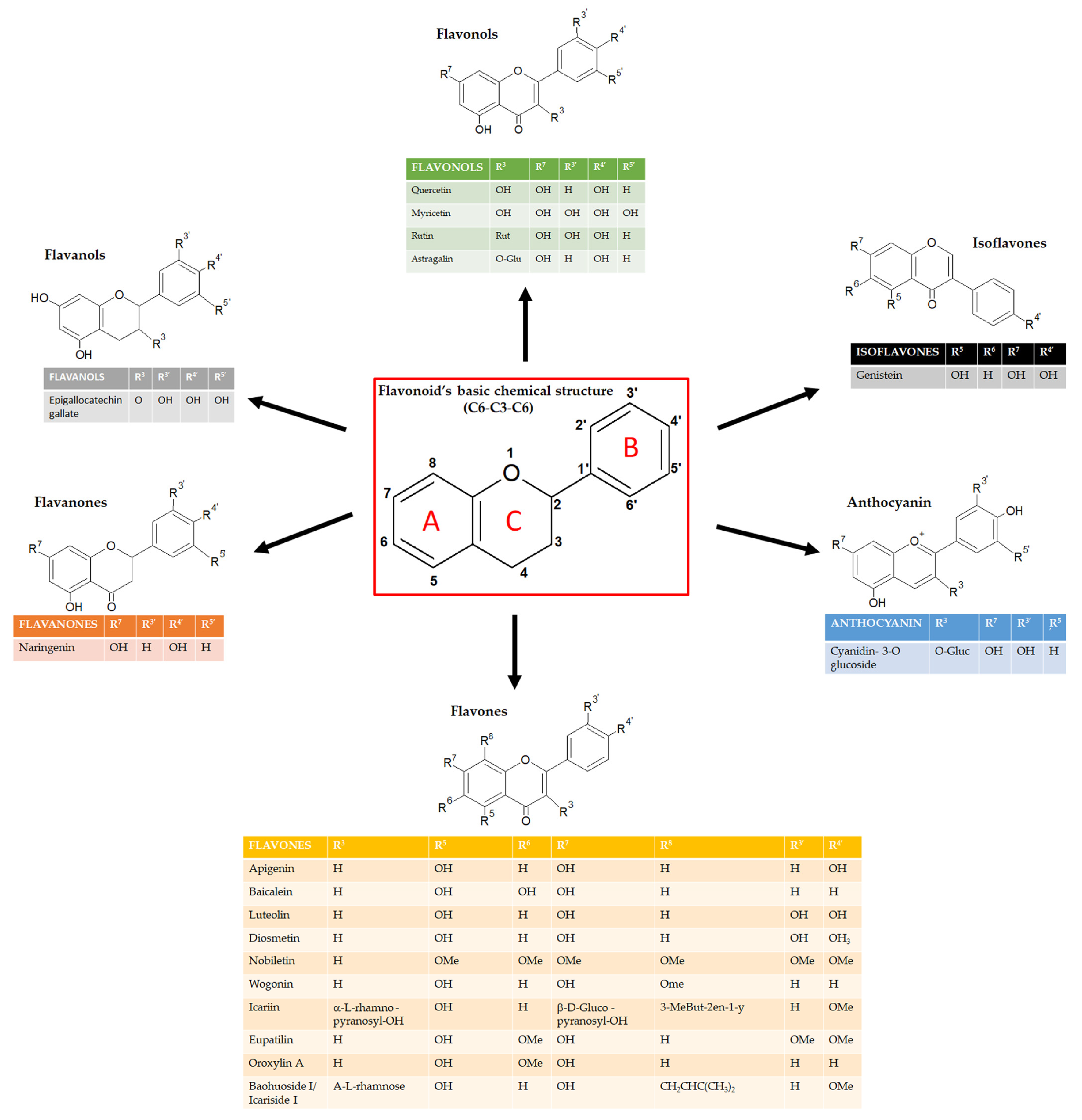

1. Introduction

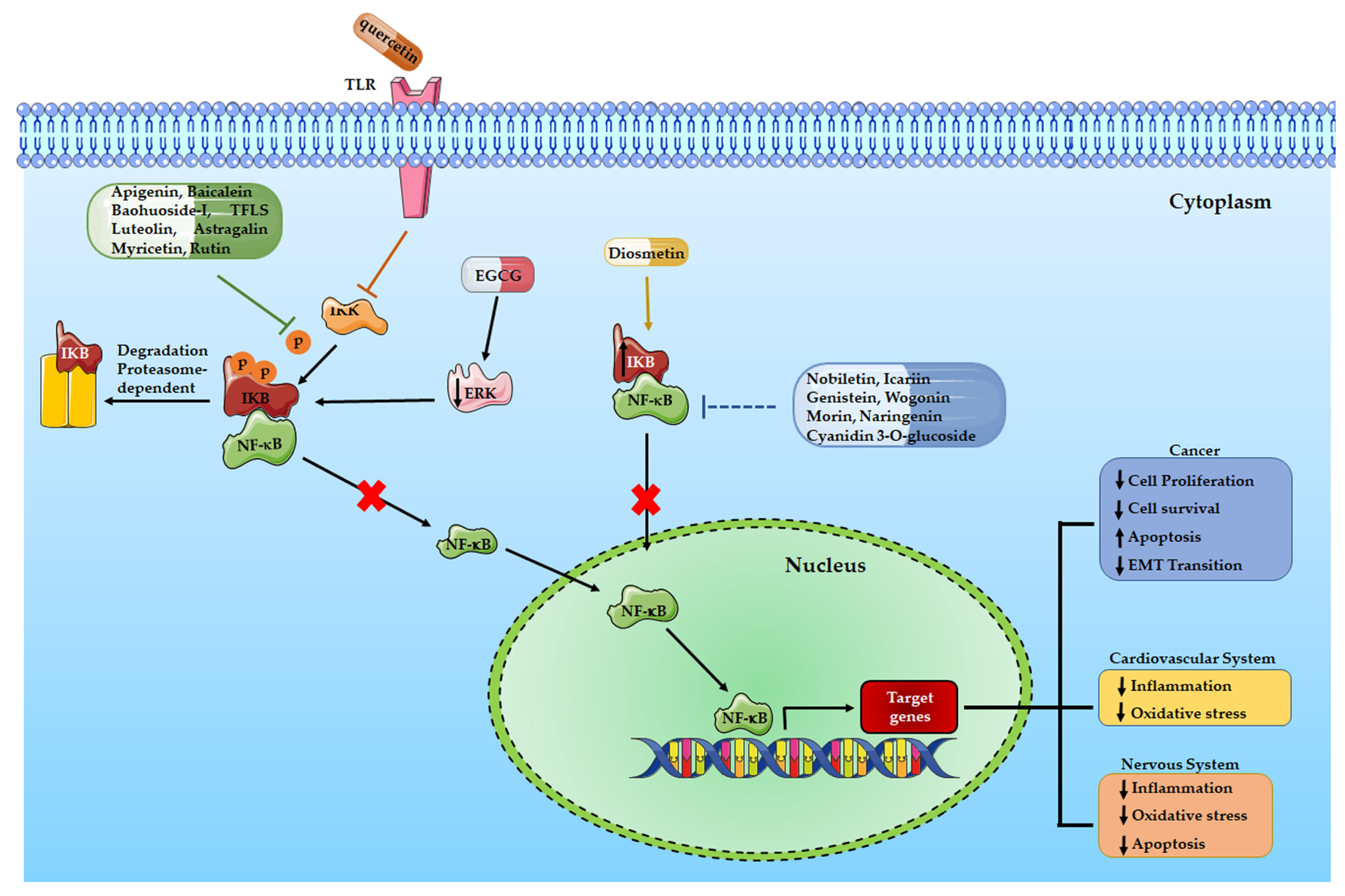

2. The NF-κB pathway

3. Flavonoids and cancer: role of NF-κB signaling pathway

| Flavonoids | Subgroups | Chemical Structure | Activity as NF-kB signaling inhibitor with proven anticancer effects | REFS. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercetin | Flavonol | C15H10O7 | Leukemia cells. Cervical, non-small lung, colon, liver, and prostate cancer cells | [49,50,51,52,53,54] |

| Apigenin | Flavone | C15H10O5 | Prostate adenocarcinoma, colon, prostate, and lung cancer cells. Mesothelioma. | [56,57,58,59] |

| Diosmetin | Flavone | C16H12O6 | Colorectal cancer cells | [60,61,62,64] |

| Baohuoside-I | Flavonol | C27H30O10 | Hepatocellular carcinoma, | [67] |

| Baicalein | Flavone | C15H10O5 | Breast cancer | [76] |

| Luteolin | Flavone | C15H10O6 | Glioblastoma cells, breast and pancreatic cancer cells, hepatocarcinoma cells | [78] |

| Nobiletin | Flavone | C21H22O8 | Pancreatic carcinoma, and colorectal cancer cells | [81] |

| TFLS | Flavone | C15H10O5 | Prostate cancer cells | [85] |

| Genistein | Flavone | C15H10O5 | Breast, thyroid, and colon cancer cells and multiple myeloma cells | [88,89] |

| Wogonin | Flavone | C16H12O5 | Hepatocellular carcinoma, colon cancer, and myelogenous leukemia | [90] |

| EGCG | Flavan-3-ol | C22H18O11 | Ovarian cancer cells | [96] |

| Eupatilin | Flavone | C18H16O7 | Gastric cancer cells | [97] |

| Oroxylin A | Flavone | C16H12O5 | Breast cancer cells | [98] |

| Astragalin | Flavone | C21H20O11 | Colon, and lung cancer cells | [99] |

4. Flavonoids and cardiovascular diseases: role of NF-κB signaling pathway

5. Flavonoids and neurodegenerative diseases: role of NF-κB signaling pathway

5. Methods

6. Conclusions, limitations and future perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor-kB |

| USDA | United States Department Of Agriculture |

| UV | ultraviolet |

| IKK | IκB Kinase |

| IκB | inhibitor of NF-κB |

| NLS | nuclear localization signal |

| TNFR | Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor |

| NIK | NF-κB-inducing kinase |

| 5-FU | 5-Fluorouracil |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor α |

| IL-1 | Interleukin-1 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| iNOS | inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| COX | CycloOXygenase |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinases |

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| ARE | antioxidant response element |

| EAC | Ehrlich ascites carcinoma |

| TRAMP | TRansgenic Adenocarcinoma Mouse Prostate |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| Bcl-xL | B-cell lymphoma-extra-large |

| TRAIL | tumor-necrosis factor related apoptosis-inducing ligand, CD253 |

| BMP | Bone morphogenetic proteins |

| HO-1 | heme oxygenase-1 |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth factor |

| hTERT | human telomerase reverse transcriptase |

| TFLS | total flavonoids of litchi seeds |

| EMT | epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| PARP | Poli ADP-ribose polymerase |

| Bax | Bcl-2 associated X protein |

| EGCG | epigallocatechin-gallate |

| Sp1 | Specific protein 1 |

| AP-1 | activator protein 1 |

| MMP-2 | metalloproteinase-2 |

| MMP-9 | metalloproteinase-9 |

| CVD | cardiovascular disease |

| AS | Atherosclerosis |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| TLR | Toll-Like Receptor |

| TGF- | tumor growth factor- |

| DOXO | Doxorubicin |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| GSK3 | Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin1 |

| Aβ | β-amyloid |

| Erk | extracellular signal-regulated kinases |

| SAMP8 | Senescence-accelerated mouse prone 8 |

| pMCAO | permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| CLP | cecal ligation and puncture |

References

- Sun, W.; Shahrajabian, M.H. Therapeutic Potential of Phenolic Compounds in Medicinal Plants-Natural Health Products for Human Health. Molecules 2023, 28. [CrossRef]

- Calis, Z.; Mogulkoc, R.; Baltaci, A.K. The Roles of Flavonols/Flavonoids in Neurodegeneration and Neuroinflammation. Mini Rev Med Chem 2020, 20, 1475-1488. [CrossRef]

- Micek, A.; Godos, J.; Del Rio, D.; Galvano, F.; Grosso, G. Dietary Flavonoids and Cardiovascular Disease: A Comprehensive Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Mol Nutr Food Res 2021, 65, e2001019. [CrossRef]

- Aiello, P.; Consalvi, S.; Poce, G.; Raguzzini, A.; Toti, E.; Palmery, M.; Biava, M.; Bernardi, M.; Kamal, M.A.; Perry, G.; et al. Dietary flavonoids: Nano delivery and nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Semin Cancer Biol 2021, 69, 150-165, doi:S1044-579X(19)30217-2. [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Wang, T.; Gan, Q.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Jin, B. Plant flavonoids: Classification, distribution, biosynthesis, and antioxidant activity. Food Chem 2022, 383, 132531, doi:S0308-8146(22)00493-9. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, I.; Perez-Gregorio, R.; Soares, S.; Mateus, N.; de Freitas, V. Wine Flavonoids in Health and Disease Prevention. Molecules 2017, 22. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xian, D.; Xiong, X.; Lai, R.; Song, J.; Zhong, J. Proanthocyanidins against Oxidative Stress: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications. Biomed Res Int 2018, 2018, 8584136. [CrossRef]

- Ferreyra, M.L.F.; Serra, P.; Casati, P. Recent advances on the roles of flavonoids as plant protective molecules after UV and high light exposure. Physiol Plant 2021, 173, 736-749. [CrossRef]

- Garcia Forero, A.; Villamizar Mantilla, D.A.; Nunez, L.A.; Ocazionez, R.E.; Stashenko, E.E.; Fuentes, J.L. Photoprotective and Antigenotoxic Effects of the Flavonoids Apigenin, Naringenin and Pinocembrin. Photochem Photobiol 2019, 95, 1010-1018. [CrossRef]

- Ghasemian, A.; Eslami, M.; Hasanvand, F.; Bozorgi, H.; Al-Abodi, H.R. Eucalyptus camaldulensis properties for use in the eradication of infections. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2019, 65, 234-237, doi:S0147-9571(19)30076-1. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.G.; Khadke, S.K.; Yamano, A.; Woo, J.T.; Lee, J. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities of prenylated flavanones from Macaranga tanarius. Phytomedicine 2019, 63, 153033, doi:S0944-7113(19)30199-0. [CrossRef]

- Chassagne, F.; Samarakoon, T.; Porras, G.; Lyles, J.T.; Dettweiler, M.; Marquez, L.; Salam, A.M.; Shabih, S.; Farrokhi, D.R.; Quave, C.L. A Systematic Review of Plants With Antibacterial Activities: A Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Perspective. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 586548. [CrossRef]

- Selvakumar, P.; Badgeley, A.; Murphy, P.; Anwar, H.; Sharma, U.; Lawrence, K.; Lakshmikuttyamma, A. Flavonoids and Other Polyphenols Act as Epigenetic Modifiers in Breast Cancer. Nutrients 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, K.; Mazurakova, A.; Koklesova, L.; Kubatka, P.; Busselberg, D. Flavonoids Synergistically Enhance the Anti-Glioblastoma Effects of Chemotherapeutic Drugs. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Rauf, A.; Abu-Izneid, T.; Nadeem, M.; Shariati, M.A.; Khan, I.A.; Imran, A.; Orhan, I.E.; Rizwan, M.; Atif, M.; et al. Luteolin, a flavonoid, as an anticancer agent: A review. Biomed Pharmacother 2019, 112, 108612, doi:S0753-3322(18)36718-0.

- Khan, H.; Ullah, H.; Castilho, P.; Gomila, A.S.; D'Onofrio, G.; Filosa, R.; Wang, F.; Nabavi, S.M.; Daglia, M.; Silva, A.S.; et al. Targeting NF-kappaB signaling pathway in cancer by dietary polyphenols. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2020, 60, 2790-2800. [CrossRef]

- Choy, K.W.; Murugan, D.; Leong, X.F.; Abas, R.; Alias, A.; Mustafa, M.R. Flavonoids as Natural Anti-Inflammatory Agents Targeting Nuclear Factor-Kappa B (NFkappaB) Signaling in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Mini Review. Front Pharmacol 2019, 10, 1295. [CrossRef]

- Kariagina, A.; Doseff, A.I. Anti-Inflammatory Mechanisms of Dietary Flavones: Tapping into Nature to Control Chronic Inflammation in Obesity and Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, C.; Bucci, I.; Napolitano, G. The Role of the Transcription Factor Nuclear Factor-kappa B in Thyroid Autoimmunity and Cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 471. [CrossRef]

- Barnabei, L.; Laplantine, E.; Mbongo, W.; Rieux-Laucat, F.; Weil, R. NF-kappaB: At the Borders of Autoimmunity and Inflammation. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 716469. [CrossRef]

- Nathan, C. Points of control in inflammation. Nature 2002, 420, 846-852, doi:nature01320.

- Zinatizadeh, M.R.; Schock, B.; Chalbatani, G.M.; Zarandi, P.K.; Jalali, S.A.; Miri, S.R. The Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-kB) signaling in cancer development and immune diseases. Genes Dis 2021, 8, 287-297. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.C. Non-canonical NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Cell Res 2011, 21, 71-85. [CrossRef]

- Block, K.I.; Gyllenhaal, C.; Lowe, L.; Amedei, A.; Amin, A.; Amin, A.; Aquilano, K.; Arbiser, J.; Arreola, A.; Arzumanyan, A.; et al. Designing a broad-spectrum integrative approach for cancer prevention and treatment. Semin Cancer Biol 2015, 35 Suppl, S276-S304, doi:S1044-579X(15)00088-7. [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Ren, J.S.; Masuyer, E.; Ferlay, J. Global estimates of cancer prevalence for 27 sites in the adult population in 2008. Int J Cancer 2013, 132, 1133-1145. [CrossRef]

- Cragg, G.M.; Pezzuto, J.M. Natural Products as a Vital Source for the Discovery of Cancer Chemotherapeutic and Chemopreventive Agents. Med Princ Pract 2016, 25 Suppl 2, 41-59. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, J.; Silvan, B.; Entrialgo-Cadierno, R.; Villar, C.J.; Capasso, R.; Uranga, J.A.; Lombo, F.; Abalo, R. Antiproliferative and palliative activity of flavonoids in colorectal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother 2021, 143, 112241, doi:S0753-3322(21)01025-8. [CrossRef]

- Hatono, M.; Ikeda, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Kajiwara, Y.; Kawada, K.; Tsukioki, T.; Kochi, M.; Suzawa, K.; Iwamoto, T.; Yamamoto, H.; et al. Effect of isoflavones on breast cancer cell development and their impact on breast cancer treatments. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2021, 185, 307-316. [CrossRef]

- Goh, J.X.H.; Tan, L.T.; Goh, J.K.; Chan, K.G.; Pusparajah, P.; Lee, L.H.; Goh, B.H. Nobiletin and Derivatives: Functional Compounds from Citrus Fruit Peel for Colon Cancer Chemoprevention. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Turdo, A.; Glaviano, A.; Pepe, G.; Calapa, F.; Raimondo, S.; Fiori, M.E.; Carbone, D.; Basilicata, M.G.; Di Sarno, V.; Ostacolo, C.; et al. Nobiletin and Xanthohumol Sensitize Colorectal Cancer Stem Cells to Standard Chemotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Corrado, C.; Barreca, M.M.; Raimondo, S.; Diana, P.; Pepe, G.; Basilicata, M.G.; Conigliaro, A.; Alessandro, R. Nobiletin and xanthohumol counteract the TNFalpha-mediated activation of endothelial cells through the inhibition of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Cell Biol Int 2023, 47, 634-647. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.F.; Martino, T.; Dalmau, S.R.; Paes, M.C.; Barja-Fidalgo, C.; Albano, R.M.; Coelho, M.G.; Sabino, K.C. Terpenic fraction of Pterodon pubescens inhibits nuclear factor kappa B and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 1/2 activation and deregulates gene expression in leukemia cells. BMC Complement Altern Med 2012, 12, 231. [CrossRef]

- Tew, G.W.; Lorimer, E.L.; Berg, T.J.; Zhi, H.; Li, R.; Williams, C.L. SmgGDS regulates cell proliferation, migration, and NF-kappaB transcriptional activity in non-small cell lung carcinoma. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 963-976, doi:S0021-9258(20)69006-8. [CrossRef]

- Chua, H.L.; Bhat-Nakshatri, P.; Clare, S.E.; Morimiya, A.; Badve, S.; Nakshatri, H. NF-kappaB represses E-cadherin expression and enhances epithelial to mesenchymal transition of mammary epithelial cells: Potential involvement of ZEB-1 and ZEB-2. Oncogene 2007, 26, 711-724, doi:1209808. [CrossRef]

- Vilimas, T.; Mascarenhas, J.; Palomero, T.; Mandal, M.; Buonamici, S.; Meng, F.; Thompson, B.; Spaulding, C.; Macaroun, S.; Alegre, M.L.; et al. Targeting the NF-kappaB signaling pathway in Notch1-induced T-cell leukemia. Nat Med 2007, 13, 70-77, doi:nm1524. [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, C.M.; Stavnes, H.T.; Kleinberg, L.; Berner, A.; Hernandez, L.F.; Birrer, M.J.; Steinberg, S.M.; Davidson, B.; Kohn, E.C. Nuclear factor kappaB transcription factors are coexpressed and convey a poor outcome in ovarian cancer. Cancer 2010, 116, 3276-3284. [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.E.; Law, A. Morphoproteomic demonstration of constitutive nuclear factor-kappaB activation in glioblastoma multiforme with genomic correlates and therapeutic implications. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2006, 36, 421-426, doi:36/4/421.

- Li, Y.; Ahmed, F.; Ali, S.; Philip, P.A.; Kucuk, O.; Sarkar, F.H. Inactivation of nuclear factor kappaB by soy isoflavone genistein contributes to increased apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic agents in human cancer cells. Cancer Res 2005, 65, 6934-6942, doi:65/15/6934. [CrossRef]

- Avci, N.G.; Ebrahimzadeh-Pustchi, S.; Akay, Y.M.; Esquenazi, Y.; Tandon, N.; Zhu, J.J.; Akay, M. NF-kappaB inhibitor with Temozolomide results in significant apoptosis in glioblastoma via the NF-kappaB(p65) and actin cytoskeleton regulatory pathways. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 13352. [CrossRef]

- Rasmi, R.R.; Sakthivel, K.M.; Guruvayoorappan, C. NF-kappaB inhibitors in treatment and prevention of lung cancer. Biomed Pharmacother 2020, 130, 110569, doi:S0753-3322(20)30762-9. [CrossRef]

- Vargas, A.J.; Burd, R. Hormesis and synergy: Pathways and mechanisms of quercetin in cancer prevention and management. Nutr Rev 2010, 68, 418-428. [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Shoorei, H.; Khanbabapour Sasi, A.; Taheri, M.; Ayatollahi, S.A. The impact of the phytotherapeutic agent quercetin on expression of genes and activity of signaling pathways. Biomed Pharmacother 2021, 141, 111847, doi:S0753-3322(21)00629-6. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G.S. Quercetin. Monograph. Altern Med Rev 2011, 16, 172-194.

- Lai, W.W.; Hsu, S.C.; Chueh, F.S.; Chen, Y.Y.; Yang, J.S.; Lin, J.P.; Lien, J.C.; Tsai, C.H.; Chung, J.G. Quercetin inhibits migration and invasion of SAS human oral cancer cells through inhibition of NF-kappaB and matrix metalloproteinase-2/-9 signaling pathways. Anticancer Res 2013, 33, 1941-1950, doi:33/5/1941.

- Anand David, A.V.; Arulmoli, R.; Parasuraman, S. Overviews of Biological Importance of Quercetin: A Bioactive Flavonoid. Pharmacogn Rev 2016, 10, 84-89. [CrossRef]

- Ramyaa, P.; Krishnaswamy, R.; Padma, V.V. Quercetin modulates OTA-induced oxidative stress and redox signalling in HepG2 cells - up regulation of Nrf2 expression and down regulation of NF-kappaB and COX-2. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1840, 681-692, doi:S0304-4165(13)00464-9. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A.; Das, I.; Chandhok, D.; Saha, T. Redox regulation in cancer: A double-edged sword with therapeutic potential. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2010, 3, 23-34. [CrossRef]

- Rushworth, S.A.; Zaitseva, L.; Murray, M.Y.; Shah, N.M.; Bowles, K.M.; MacEwan, D.J. The high Nrf2 expression in human acute myeloid leukemia is driven by NF-kappaB and underlies its chemo-resistance. Blood 2012, 120, 5188-5198. [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.F.; He, H.F.; Chen, Q. Quercetin inhibits proliferation and invasion acts by up-regulating miR-146a in human breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Biochem 2015, 402, 93-100. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Long, C.; Junming, T.; Qihuan, L.; Youshun, Z.; Chan, Z. Quercetin-induced apoptosis of HL-60 cells by reducing PI3K/Akt. Mol Biol Rep 2012, 39, 7785-7793. [CrossRef]

- Rubio, V.; Garcia-Perez, A.I.; Herraez, A.; Diez, J.C. Different roles of Nrf2 and NFKB in the antioxidant imbalance produced by esculetin or quercetin on NB4 leukemia cells. Chem Biol Interact 2018, 294, 158-166, doi:S0009-2797(18)30610-0. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.A.; Zhang, S.; Yin, Q.; Zhang, J. Quercetin induces human colon cancer cells apoptosis by inhibiting the nuclear factor-kappa B Pathway. Pharmacogn Mag 2015, 11, 404-409. [CrossRef]

- Ward, A.B.; Mir, H.; Kapur, N.; Gales, D.N.; Carriere, P.P.; Singh, S. Quercetin inhibits prostate cancer by attenuating cell survival and inhibiting anti-apoptotic pathways. World J Surg Oncol 2018, 16, 108. [CrossRef]

- Sahyon, H.A.E.; Ramadan, E.N.M.; Althobaiti, F.; Mashaly, M.M.A. Anti-proliferative effects of the combination of Sulfamethoxazole and Quercetin via caspase3 and NFkB gene regulation: An in vitro and in vivo study. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2022, 395, 227-246. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Shankar, E.; Fu, P.; MacLennan, G.T.; Gupta, S. Suppression of NF-kappaB and NF-kappaB-Regulated Gene Expression by Apigenin through IkappaBalpha and IKK Pathway in TRAMP Mice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138710. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Kanwal, R.; Shankar, E.; Datt, M.; Chance, M.R.; Fu, P.; MacLennan, G.T.; Gupta, S. Apigenin blocks IKKalpha activation and suppresses prostate cancer progression. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 31216-31232. [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Han, L. Apigenin inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition of human colon cancer cells through NF-kappaB/Snail signaling pathway. Biosci Rep 2019, 39, doi:BSR20190452.

- Chen, M.; Wang, X.; Zha, D.; Cai, F.; Zhang, W.; He, Y.; Huang, Q.; Zhuang, H.; Hua, Z.C. Apigenin potentiates TRAIL therapy of non-small cell lung cancer via upregulating DR4/DR5 expression in a p53-dependent manner. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 35468. [CrossRef]

- Masuelli, L.; Benvenuto, M.; Mattera, R.; Di Stefano, E.; Zago, E.; Taffera, G.; Tresoldi, I.; Giganti, M.G.; Frajese, G.V.; Berardi, G.; et al. In Vitro and In Vivo Anti-tumoral Effects of the Flavonoid Apigenin in Malignant Mesothelioma. Front Pharmacol 2017, 8, 373. [CrossRef]

- Androutsopoulos, V.P.; Mahale, S.; Arroo, R.R.; Potter, G. Anticancer effects of the flavonoid diosmetin on cell cycle progression and proliferation of MDA-MB 468 breast cancer cells due to CYP1 activation. Oncol Rep 2009, 21, 1525-1528. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Shi, Y.; Peng, W.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Chen, N.; Zhu, R. Diosmetin induces apoptosis by upregulating p53 via the TGF-beta signal pathway in HepG2 hepatoma cells. Mol Med Rep 2016, 14, 159-164. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wen, X.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Miao, H.; Zhu, R. Diosmetin inhibits the metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by downregulating the expression levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9. Mol Med Rep 2016, 13, 2401-2408. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.Y.; Yuan, D.; Yang, J.Y.; Wang, L.H.; Wu, C.F. Cytotoxic activity of flavonoids from the flowers of Chrysanthemum morifolium on human colon cancer Colon205 cells. J Asian Nat Prod Res 2009, 11, 771-778. [CrossRef]

- Koosha, S.; Mohamed, Z.; Sinniah, A.; Alshawsh, M.A. Investigation into the Molecular Mechanisms underlying the Anti-proliferative and Anti-tumorigenesis activities of Diosmetin against HCT-116 Human Colorectal Cancer. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 5148. [CrossRef]

- Schnare, M.; Barton, G.M.; Holt, A.C.; Takeda, K.; Akira, S.; Medzhitov, R. Toll-like receptors control activation of adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol 2001, 2, 947-950, doi:ni712. [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, A.S., Jr. Series introduction: The transcription factor NF-kappaB and human disease. J Clin Invest 2001, 107, 3-6, doi:11891. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Pang, B.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Jiang, D. Baohuoside I Inhibits the Proliferation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells via Apoptosis Signaling and NF-kB Pathway. Chem Biodivers 2021, 18, e2100063. [CrossRef]

- El-Shitany, N.A.; Eid, B.G. Icariin modulates carrageenan-induced acute inflammation through HO-1/Nrf2 and NF-kB signaling pathways. Biomed Pharmacother 2019, 120, 109567, doi:S0753-3322(19)35190-X. [CrossRef]

- Ikemoto, S.; Sugimura, K.; Yoshida, N.; Yasumoto, R.; Wada, S.; Yamamoto, K.; Kishimoto, T. Antitumor effects of Scutellariae radix and its components baicalein, baicalin, and wogonin on bladder cancer cell lines. Urology 2000, 55, 951-955, doi:S0090429500004672. [CrossRef]

- Li-Weber, M. New therapeutic aspects of flavones: The anticancer properties of Scutellaria and its main active constituents Wogonin, Baicalein and Baicalin. Cancer Treat Rev 2009, 35, 57-68. [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, P.; Joshee, N.; Rimando, A.M.; Mittal, S.; Yadav, A.K. In vitro antitumor mechanisms of various Scutellaria extracts and constituent flavonoids. Planta Med 2009, 75, 41-48. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.W.; Lin, T.H.; Huang, W.S.; Teng, C.Y.; Liou, Y.S.; Kuo, W.H.; Lin, W.L.; Huang, H.I.; Tung, J.N.; Huang, C.Y.; et al. Baicalein inhibits the migration and invasive properties of human hepatoma cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2011, 255, 316-326. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Guo, C.; Yang, Y.; Li, F.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, B.; Li, Q. Baicalein induces apoptosis of human cervical cancer HeLa cells in vitro. Mol Med Rep 2015, 11, 2129-2134. [CrossRef]

- Miocinovic, R.; McCabe, N.P.; Keck, R.W.; Jankun, J.; Hampton, J.A.; Selman, S.H. In vivo and in vitro effect of baicalein on human prostate cancer cells. Int J Oncol 2005, 26, 241-246. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, A.Y.; Ye, X.; Luo, H.; Rankin, G.O.; Chen, Y.C. Inhibitory effect of baicalin and baicalein on ovarian cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci 2013, 14, 6012-6025. [CrossRef]

- Shehatta, N.H.; Okda, T.M.; Omran, G.A.; Abd-Alhaseeb, M.M. Baicalin; a promising chemopreventive agent, enhances the antitumor effect of 5-FU against breast cancer and inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis in Ehrlich solid tumor. Biomed Pharmacother 2022, 146, 112599, doi:S0753-3322(21)01386-X. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Shi, R.; Wang, X.; Shen, H.M. Luteolin, a flavonoid with potential for cancer prevention and therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2008, 8, 634-646. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Jin, K.; Lan, H. Luteolin inhibits cell cycle progression and induces apoptosis of breast cancer cells through downregulation of human telomerase reverse transcriptase. Oncol Lett 2019, 17, 3842-3850. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, A.; Nakamura, Y.; Torikai, K.; Tanaka, T.; Koshiba, T.; Koshimizu, K.; Kuwahara, S.; Takahashi, Y.; Ogawa, K.; Yano, M.; et al. Inhibitory effect of citrus nobiletin on phorbol ester-induced skin inflammation, oxidative stress, and tumor promotion in mice. Cancer Res 2000, 60, 5059-5066.

- Kandaswami, C.; Perkins, E.; Soloniuk, D.S.; Drzewiecki, G.; Middleton, E., Jr. Antiproliferative effects of citrus flavonoids on a human squamous cell carcinoma in vitro. Cancer Lett 1991, 56, 147-152, doi:0304-3835(91)90089-Z. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Chen, H.; Jin, C.; Mo, J.; Wang, H. Nobiletin flavone inhibits the growth and metastasis of human pancreatic cancer cells via induction of autophagy, G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and inhibition of NF-kB signalling pathway. J BUON 2020, 25, 1070-1075.

- Hsu, C.P.; Lin, C.C.; Huang, C.C.; Lin, Y.H.; Chou, J.C.; Tsia, Y.T.; Su, J.R.; Chung, Y.C. Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in human colorectal carcinoma by Litchi seed extract. J Biomed Biotechnol 2012, 2012, 341479. [CrossRef]

- Emanuele, S.; Notaro, A.; Palumbo Piccionello, A.; Maggio, A.; Lauricella, M.; D'Anneo, A.; Cernigliaro, C.; Calvaruso, G.; Giuliano, M. Sicilian Litchi Fruit Extracts Induce Autophagy versus Apoptosis Switch in Human Colon Cancer Cells. Nutrients 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Luo, H.; Yuan, H.; Xia, Y.; Shu, P.; Huang, X.; Lu, Y.; Liu, X.; Keller, E.T.; Sun, D.; et al. Author Correction: Litchi seed extracts diminish prostate cancer progression via induction of apoptosis and attenuation of EMT through Akt/GSK-3beta signaling. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 15201. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Zhu, D.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Li, X.L.; Cheng, Z.; Su, Z.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Y.; et al. Total Flavonoids of Litchi Seed Attenuate Prostate Cancer Progression Via Inhibiting AKT/mTOR and NF-kB Signaling Pathways. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 758219. [CrossRef]

- Zamani-Garmsiri, F.; Emamgholipour, S.; Rahmani Fard, S.; Ghasempour, G.; Jahangard Ahvazi, R.; Meshkani, R. Polyphenols: Potential anti-inflammatory agents for treatment of metabolic disorders. Phytother Res 2022, 36, 415-432. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Q.; Luo, Y.; Qiao, C.H. The mechanisms of anticancer agents by genistein and synthetic derivatives of isoflavone. Mini Rev Med Chem 2012, 12, 350-362, doi:MRMC-EPUB-20120201-011. [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wang, J.; Zhu, B. Genistein inhibits the proliferation of human multiple myeloma cells through suppression of nuclear factor-kappaB and upregulation of microRNA-29b. Mol Med Rep 2016, 13, 1627-1632. [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, S.A.; Alp, E.; Yar Saglam, A.S.; Konac, E.; Menevse, E.S. The effects of thymoquinone and genistein treatment on telomerase activity, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and survival in thyroid cancer cell lines. J Cancer Res Ther 2018, 14, 328-334. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tian, S.; Liu, M.; Jian, L.; Zhao, L. Wogonin inhibits the proliferation and invasion, and induces the apoptosis of HepG2 and Bel7402 HCC cells through NF-kappaB/Bcl-2, EGFR and EGFR downstream ERK/AKT signaling. Int J Mol Med 2016, 38, 1250-1256. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Afaq, F.; Saleem, M.; Ahmad, N.; Mukhtar, H. Targeting multiple signaling pathways by green tea polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 2500-2505, doi:66/5/2500. [CrossRef]

- Gan, R.Y.; Li, H.B.; Sui, Z.Q.; Corke, H. Absorption, metabolism, anti-cancer effect and molecular targets of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG): An updated review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2018, 58, 924-941. [CrossRef]

- Zubair, H.; Azim, S.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, M.A.; Patel, G.K.; Singh, S.; Singh, A.P. Cancer Chemoprevention by Phytochemicals: Nature's Healing Touch. Molecules 2017, 22. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M.; Shirakami, Y.; Moriwaki, H. Targeting receptor tyrosine kinases for chemoprevention by green tea catechin, EGCG. Int J Mol Sci 2008, 9, 1034-1049. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M.; Weinstein, I.B. Modulation of signal transduction by tea catechins and related phytochemicals. Mutat Res 2005, 591, 147-160, doi:S0027-5107(05)00156-9. [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Tian, D.; Qiao, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, L. Modulation of Myb-induced NF-kB -STAT3 signaling and resulting cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer by dietary factors. J Cell Physiol 2019, 234, 21126-21134. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hou, H.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Sun, L. Anticancer effect of eupatilin on glioma cells through inhibition of the Notch-1 signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep 2016, 13, 1141-1146. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Chang, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, B.; Cao, X. Oroxylin A Suppresses the Cell Proliferation, Migration, and EMT via NF-kappaB Signaling Pathway in Human Breast Cancer Cells. Biomed Res Int 2019, 2019, 9241769. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Cai, F.; Zha, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; He, Y.; Huang, Q.; Zhuang, H.; Hua, Z.C. Astragalin-induced cell death is caspase-dependent and enhances the susceptibility of lung cancer cells to tumor necrosis factor by inhibiting the NF-small ka, CyrillicB pathway. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 26941-26958. [CrossRef]

- Townsend, N.; Nichols, M.; Scarborough, P.; Rayner, M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe--epidemiological update 2015. Eur Heart J 2015, 36, 2696-2705. [CrossRef]

- Micha, R.; Penalvo, J.L.; Cudhea, F.; Imamura, F.; Rehm, C.D.; Mozaffarian, D. Association Between Dietary Factors and Mortality From Heart Disease, Stroke, and Type 2 Diabetes in the United States. JAMA 2017, 317, 912-924. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, X.; Meng, X. Role of inflammation, immunity, and oxidative stress in hypertension: New insights and potential therapeutic targets. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1098725. [CrossRef]

- Fiordelisi, A.; Iaccarino, G.; Morisco, C.; Coscioni, E.; Sorriento, D. NFkappaB is a Key Player in the Crosstalk between Inflammation and Cardiovascular Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D.; Ley, K. Immunity and Inflammation in Atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2019, 124, 315-327. [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Kwon, T.H.; Yun, B.S.; Park, N.H.; Rhee, M.H. Eisenia bicyclis (brown alga) modulates platelet function and inhibits thrombus formation via impaired P(2)Y(12) receptor signaling pathway. Phytomedicine 2018, 40, 79-87, doi:S0944-7113(18)30003-5. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.V.; Mistry, B.M.; Shinde, S.K.; Syed, R.; Singh, V.; Shin, H.S. Therapeutic potential of quercetin as a cardiovascular agent. Eur J Med Chem 2018, 155, 889-904, doi:S0223-5234(18)30544-0. [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, S.; Sudhakaran, P.R.; Helen, A. Quercetin attenuates atherosclerotic inflammation and adhesion molecule expression by modulating TLR-NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Cell Immunol 2016, 310, 131-140, doi:S0008-8749(16)30084-3. [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, E.V.; Falchetti, F.; Pernomian, L.; de Mello, M.M.B.; Parente, J.M.; Nogueira, R.C.; Gomes, B.Q.; Bertozi, G.; Sanches-Lopes, J.M.; Tanus-Santos, J.E.; et al. Quercetin decreases cardiac hypertrophic mediators and maladaptive coronary arterial remodeling in renovascular hypertensive rats without improving cardiac function. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chekalina, N.; Burmak, Y.; Petrov, Y.; Borisova, Z.; Manusha, Y.; Kazakov, Y.; Kaidashev, I. Quercetin reduces the transcriptional activity of NF-kB in stable coronary artery disease. Indian Heart J 2018, 70, 593-597, doi:S0019-4832(17)30210-9. [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yue, Y.; Yang, D. Icariside II improves myocardial fibrosis in spontaneously hypertensive rats by inhibiting collagen synthesis. J Pharm Pharmacol 2020, 72, 227-235. [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Kwon, T.H.; Lee, D.H.; Hong, S.B.; Oh, J.W.; Kim, S.D.; Rhee, M.H. Antiplatelet and Antithrombotic Effects of Epimedium koreanum Nakai. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2021, 2021, 7071987. [CrossRef]

- Hua, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Kang, L.; Tu, J.; Zhao, K.; Li, S.; Wang, K.; Song, Y.; Luo, R.; et al. Icariin Attenuates Interleukin-1beta-Induced Inflammatory Response in Human Nucleus Pulposus Cells. Curr Pharm Des 2018, 23, 6071-6078. [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Li, Y.L.; Wu, Y.T.; Yue, Y.; Qian, Z.Q.; Yang, D.L. Icariside II attenuates myocardial fibrosis by inhibiting nuclear factor-kappaB and the TGF-beta1/Smad2 signalling pathway in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Biomed Pharmacother 2018, 100, 64-71, doi:S0753-3322(17)36155-3. [CrossRef]

- Hao, G.; Yu, Y.; Gu, B.; Xing, Y.; Xue, M. Protective effects of berberine against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats by inhibiting metabolism of doxorubicin. Xenobiotica 2015, 45, 1024-1029. [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, D.; Swaroop, A.; Preuss, H.G.; Bagchi, M. Free radical scavenging, antioxidant and cancer chemoprevention by grape seed proanthocyanidin: An overview. Mutat Res 2014, 768, 69-73, doi:S0027-5107(14)00070-0. [CrossRef]

- Sadek, K.M.; Mahmoud, S.F.E.; Zeweil, M.F.; Abouzed, T.K. Proanthocyanidin alleviates doxorubicin-induced cardiac injury by inhibiting NF-kB pathway and modulating oxidative stress, cell cycle, and fibrogenesis. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2021, 35, e22716. [CrossRef]

- Kuzu, M.; Kandemir, F.M.; Yildirim, S.; Kucukler, S.; Caglayan, C.; Turk, E. Morin attenuates doxorubicin-induced heart and brain damage by reducing oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis. Biomed Pharmacother 2018, 106, 443-453, doi:S0753-3322(18)32527-7. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Jiang, L.; Lu, X.; Liu, X.; Ling, M. Curcumin protects radiation-induced liver damage in rats through the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. BMC Complement Med Ther 2021, 21, 10. [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.S.; Dutta, P.; Chard, N.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Q.H.; Chen, G.; Vadgama, J. A novel curcumin analog inhibits canonical and non-canonical functions of telomerase through STAT3 and NF-kappaB inactivation in colorectal cancer cells. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 4516-4531. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.U.; Rehman, M.S.; Khan, M.S.; Ali, M.A.; Javed, A.; Nawaz, A.; Yang, C. Curcumin as an Alternative Epigenetic Modulator: Mechanism of Action and Potential Effects. Front Genet 2019, 10, 514. [CrossRef]

- Benzer, F.; Kandemir, F.M.; Ozkaraca, M.; Kucukler, S.; Caglayan, C. Curcumin ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by abrogation of inflammation, apoptosis, oxidative DNA damage, and protein oxidation in rats. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2018, 32. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, T.G. Role of Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-kappaB) Signalling in Neurodegenerative Diseases: An Mechanistic Approach. Curr Neuropharmacol 2020, 18, 918-935. [CrossRef]

- Camandola, S.; Mattson, M.P. NF-kappa B as a therapeutic target in neurodegenerative diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2007, 11, 123-132. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Jana, M.; Majumder, M.; Mondal, S.; Roy, A.; Pahan, K. Selective targeting of the TLR2/MyD88/NF-kappaB pathway reduces alpha-synuclein spreading in vitro and in vivo. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 5382. [CrossRef]

- Calfio, C.; Gonzalez, A.; Singh, S.K.; Rojo, L.E.; Maccioni, R.B. The Emerging Role of Nutraceuticals and Phytochemicals in the Prevention and Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2020, 77, 33-51. [CrossRef]

- Maccioni, R.B.; Calfio, C.; Gonzalez, A.; Luttges, V. Novel Nutraceutical Compounds in Alzheimer Prevention. Biomolecules 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Zaplatic, E.; Bule, M.; Shah, S.Z.A.; Uddin, M.S.; Niaz, K. Molecular mechanisms underlying protective role of quercetin in attenuating Alzheimer's disease. Life Sci 2019, 224, 109-119, doi:S0024-3205(19)30219-X. [CrossRef]

- Atrahimovich, D.; Avni, D.; Khatib, S. Flavonoids-Macromolecules Interactions in Human Diseases with Focus on Alzheimer, Atherosclerosis and Cancer. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Maher, P. The Potential of Flavonoids for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [CrossRef]

- Zu, G.; Sun, K.; Li, L.; Zu, X.; Han, T.; Huang, H. Mechanism of quercetin therapeutic targets for Alzheimer disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 22959. [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.H.; Chan, S.H.; Chu, P.M.; Tsai, K.L. Quercetin is a potent anti-atherosclerotic compound by activation of SIRT1 signaling under oxLDL stimulation. Mol Nutr Food Res 2015, 59, 1905-1917. [CrossRef]

- Bouchelaghem, S. Propolis characterization and antimicrobial activities against Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans: A review. Saudi J Biol Sci 2022, 29, 1936-1946. [CrossRef]

- Nahmias, Y.; Goldwasser, J.; Casali, M.; van Poll, D.; Wakita, T.; Chung, R.T.; Yarmush, M.L. Apolipoprotein B-dependent hepatitis C virus secretion is inhibited by the grapefruit flavonoid naringenin. Hepatology 2008, 47, 1437-1445. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Kuboyama, T.; Tohda, C. Naringenin promotes microglial M2 polarization and Abeta degradation enzyme expression. Phytother Res 2019, 33, 1114-1121. [CrossRef]

- Sarubbo, F.; Ramis, M.R.; Kienzer, C.; Aparicio, S.; Esteban, S.; Miralles, A.; Moranta, D. Chronic Silymarin, Quercetin and Naringenin Treatments Increase Monoamines Synthesis and Hippocampal Sirt1 Levels Improving Cognition in Aged Rats. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2018, 13, 24-38. [CrossRef]

- Khalatbary, A.R.; Khademi, E. The green tea polyphenolic catechin epigallocatechin gallate and neuroprotection. Nutr Neurosci 2020, 23, 281-294. [CrossRef]

- Calderaro, A.; Patane, G.T.; Tellone, E.; Barreca, D.; Ficarra, S.; Misiti, F.; Lagana, G. The Neuroprotective Potentiality of Flavonoids on Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Arafa, M.H.; Atteia, H.H. Protective Role of Epigallocatechin Gallate in a Rat Model of Cisplatin-Induced Cerebral Inflammation and Oxidative Damage: Impact of Modulating NF-kappaB and Nrf2. Neurotox Res 2020, 37, 380-396. [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Rong, C.; Chen, Y.; Yang, C.; Hu, Q.; Mo, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gu, X.; Zhang, L.; He, W.; et al. (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate attenuates cognitive deterioration in Alzheimer's disease model mice by upregulating neprilysin expression. Exp Cell Res 2015, 334, 136-145, doi:S0014-4827(15)00136-6. [CrossRef]

- Nardini, M.; Garaguso, I. Characterization of bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of fruit beers. Food Chem 2020, 305, 125437, doi:S0308-8146(19)31552-3. [CrossRef]

- Taheri, Y.; Suleria, H.A.R.; Martins, N.; Sytar, O.; Beyatli, A.; Yeskaliyeva, B.; Seitimova, G.; Salehi, B.; Semwal, P.; Painuli, S.; et al. Myricetin bioactive effects: Moving from preclinical evidence to potential clinical applications. BMC Complement Med Ther 2020, 20, 241. [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Saeed, F.; Hussain, G.; Imran, A.; Mehmood, Z.; Gondal, T.A.; El-Ghorab, A.; Ahmad, I.; Pezzani, R.; Arshad, M.U.; et al. Myricetin: A comprehensive review on its biological potentials. Food Sci Nutr 2021, 9, 5854-5868. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Xu, P.; Fu, T.; Huang, X.; Song, J.; Chen, M.; Tian, X.; Yin, H.; Han, J. Myricetin against ischemic cerebral injury in rat middle cerebral artery occlusion model. Mol Med Rep 2018, 17, 3274-3280. [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Jung, K.; Yoo, H.; Park, G. Inhibitory Effects of Myricetin on Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Neuroinflammation. Brain Sci 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kaewmool, C.; Udomruk, S.; Phitak, T.; Pothacharoen, P.; Kongtawelert, P. Cyanidin-3-O-Glucoside Protects PC12 Cells Against Neuronal Apoptosis Mediated by LPS-Stimulated BV2 Microglial Activation. Neurotox Res 2020, 37, 111-125. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, G.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Yi, S.; Wang, K.; Fan, L.; Tang, J.; Chen, R. Multi-Omics Integration in Mice With Parkinson's Disease and the Intervention Effect of Cyanidin-3-O-Glucoside. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14, 877078. [CrossRef]

- Chiocchio, I.; Prata, C.; Mandrone, M.; Ricciardiello, F.; Marrazzo, P.; Tomasi, P.; Angeloni, C.; Fiorentini, D.; Malaguti, M.; Poli, F.; et al. Leaves and Spiny Burs of Castanea Sativa from an Experimental Chestnut Grove: Metabolomic Analysis and Anti-Neuroinflammatory Activity. Metabolites 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Badanjak, K.; Fixemer, S.; Smajic, S.; Skupin, A.; Grunewald, A. The Contribution of Microglia to Neuroinflammation in Parkinson's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, A. Postmortem studies in Parkinson's disease. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2004, 6, 281-293. [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Singh, S. Apigenin Attenuates Functional and Structural Alterations via Targeting NF-kB/Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in LPS-Induced Parkinsonism in Experimental Rats : Apigenin Attenuates LPS-Induced Parkinsonism in Experimental Rats. Neurotox Res 2022, 40, 941-960. [CrossRef]

- Budzynska, B.; Faggio, C.; Kruk-Slomka, M.; Samec, D.; Nabavi, S.F.; Sureda, A.; Devi, K.P.; Nabavi, S.M. Rutin as Neuroprotective Agent: From Bench to Bedside. Curr Med Chem 2019, 26, 5152-5164. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.Y.; Li, L.J.; Dong, Q.X.; Zhu, J.; Huang, Y.R.; Hou, S.J.; Yu, X.L.; Liu, R.T. Rutin prevents tau pathology and neuroinflammation in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 131. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wei, H.; Cai, M.; Lu, Y.; Hou, W.; Yang, Q.; Dong, H.; Xiong, L. Genistein attenuates brain damage induced by transient cerebral ischemia through up-regulation of ERK activity in ovariectomized mice. Int J Biol Sci 2014, 10, 457-465. [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Chen, M.; Xia, Z.; Tang, W.; Li, Y.; Qin, C.; Ahmadi, A.; Huang, C.; Xu, H. Genistein attenuates neuroinflammation and oxidative stress and improves cognitive impairment in a rat model of sepsis-associated encephalopathy: Potential role of the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Metab Brain Dis 2023, 38, 339-347. [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, A.; Ohizumi, Y. Potential Benefits of Nobiletin, A Citrus Flavonoid, against Alzheimer's Disease and Parkinson's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [CrossRef]

- Kimura, J.; Shimizu, K.; Kajima, K.; Yokosuka, A.; Mimaki, Y.; Oku, N.; Ohizumi, Y. Nobiletin Reduces Intracellular and Extracellular beta-Amyloid in iPS Cell-Derived Alzheimer's Disease Model Neurons. Biol Pharm Bull 2018, 41, 451-457. [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.; Mi, Y.; Fan, R.; Li, R.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X. Nobiletin Protects against Systemic Inflammation-Stimulated Memory Impairment via MAPK and NF-kappaB Signaling Pathways. J Agric Food Chem 2019, 67, 5122-5134. [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi-Tarie, R.; Kiasalari, Z.; Fakour, M.; Khorasani, M.; Keshtkar, S.; Baluchnejadmojarad, T.; Roghani, M. Nobiletin prevents amyloid beta(1-40)-induced cognitive impairment via inhibition of neuroinflammation and oxidative/nitrosative stress. Metab Brain Dis 2022, 37, 1337-1349. [CrossRef]

- Hua, F.Z.; Ying, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.F.; Hu, Y.H.; Liang, Y.P.; Liu, Q.; Xu, G.H. Naringenin pre-treatment inhibits neuroapoptosis and ameliorates cognitive impairment in rats exposed to isoflurane anesthesia by regulating the PI3/Akt/PTEN signalling pathway and suppressing NF-kappaB-mediated inflammation. Int J Mol Med 2016, 38, 1271-1280. [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O'Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010, 5, 69. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hassan, Y.I.; Liu, R.; Mats, L.; Yang, C.; Liu, C.; Tsao, R. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Absorption of Aglycone and Glycosidic Flavonoids in a Caco-2 BBe1 Cell Model. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 10782-10793. [CrossRef]

- Kosinova, P.; Berka, K.; Wykes, M.; Otyepka, M.; Trouillas, P. Positioning of antioxidant quercetin and its metabolites in lipid bilayer membranes: Implication for their lipid-peroxidation inhibition. J Phys Chem B 2012, 116, 1309-1318. [CrossRef]

- Raghunathan, M.; Zubovski, Y.; Venable, R.M.; Pastor, R.W.; Nagle, J.F.; Tristram-Nagle, S. Structure and elasticity of lipid membranes with genistein and daidzein bioflavinoids using X-ray scattering and MD simulations. J Phys Chem B 2012, 116, 3918-3927. [CrossRef]

- Tarahovsky, Y.S.; Kim, Y.A.; Yagolnik, E.A.; Muzafarov, E.N. Flavonoid-membrane interactions: Involvement of flavonoid-metal complexes in raft signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1838, 1235-1246, doi:S0005-2736(14)00029-7. [CrossRef]

- Hendrich, A.B. Flavonoid-membrane interactions: Possible consequences for biological effects of some polyphenolic compounds. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2006, 27, 27-40. [CrossRef]

- Middleton, E., Jr.; Kandaswami, C.; Theoharides, T.C. The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: Implications for inflammation, heart disease, and cancer. Pharmacol Rev 2000, 52, 673-751.

- Singh, P.; Mishra, S.K.; Noel, S.; Sharma, S.; Rath, S.K. Acute exposure of apigenin induces hepatotoxicity in Swiss mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31964. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, S.; Mei, H.; Xuan, J.; Guo, X.; Couch, L.; Dobrovolsky, V.N.; Guo, L.; Mei, N. Ginkgo biloba leaf extract induces DNA damage by inhibiting topoisomerase II activity in human hepatic cells. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 14633. [CrossRef]

| Flavonoids | Subgroups | Chemical Structure | Effects on NF-kB signaling with proven positive effect on cardiovascular diseases | REFS. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercetin | Flavonols | C15H10O7 | Hypertension, coronary artery diseases | [108,109] |

| Icariside II | Flavonol | C27H30O10 | Myocardial fibrosis | [113] |

| Pronthocyanidin | polyphenols | Heart injury and fibrosis | [116] | |

| Morin | Flavone | C15H10O7 | Heart damage | [117] |

| Curcumin | Diarylheptanoid | Cardiotoxicity | [118] |

| Flavonoids | Subgroups | Chemical Structure | Effects on NF-kB signaling with proven positive effect on neurodegenerative diseases | REFS. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercetin | Flavonols | C15H10O7 | Atherosclerosis | [132] |

| Apigenin | Flavone | C15H10O5 | Parkinson disease | [150] |

| Naringenin | Flavanones | C15H12O5 | Alzheimer disease cognitive impairment |

[134,159] |

| EGCG | Flavan-3-ols | C22H18O11 | Alzheimer disease | [138] |

| Myricetin | Flavonols | C15H10O8 | Ischemic cerebral injury, microglia inflammation | [143,144] |

| Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside | Anthocyanin | C21H21ClO11 | microglia inflammation | [145,146] |

| Rutin | Flavonols | C27H30O16 | Alzheimer disease | [152] |

| Genistein | Flavone | C15H10O5 | Hippocampus inflammation | [154]. |

| Nobiletin | Flavone | C21H22O8 | Microglia inflammation Alzheimer disease |

[157,158] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).