Submitted:

10 May 2023

Posted:

11 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Lozi map

2.1. History

2.1.1. Initial definition

2.1.2. Chaotic properties of the dissipative map (|b|<1)

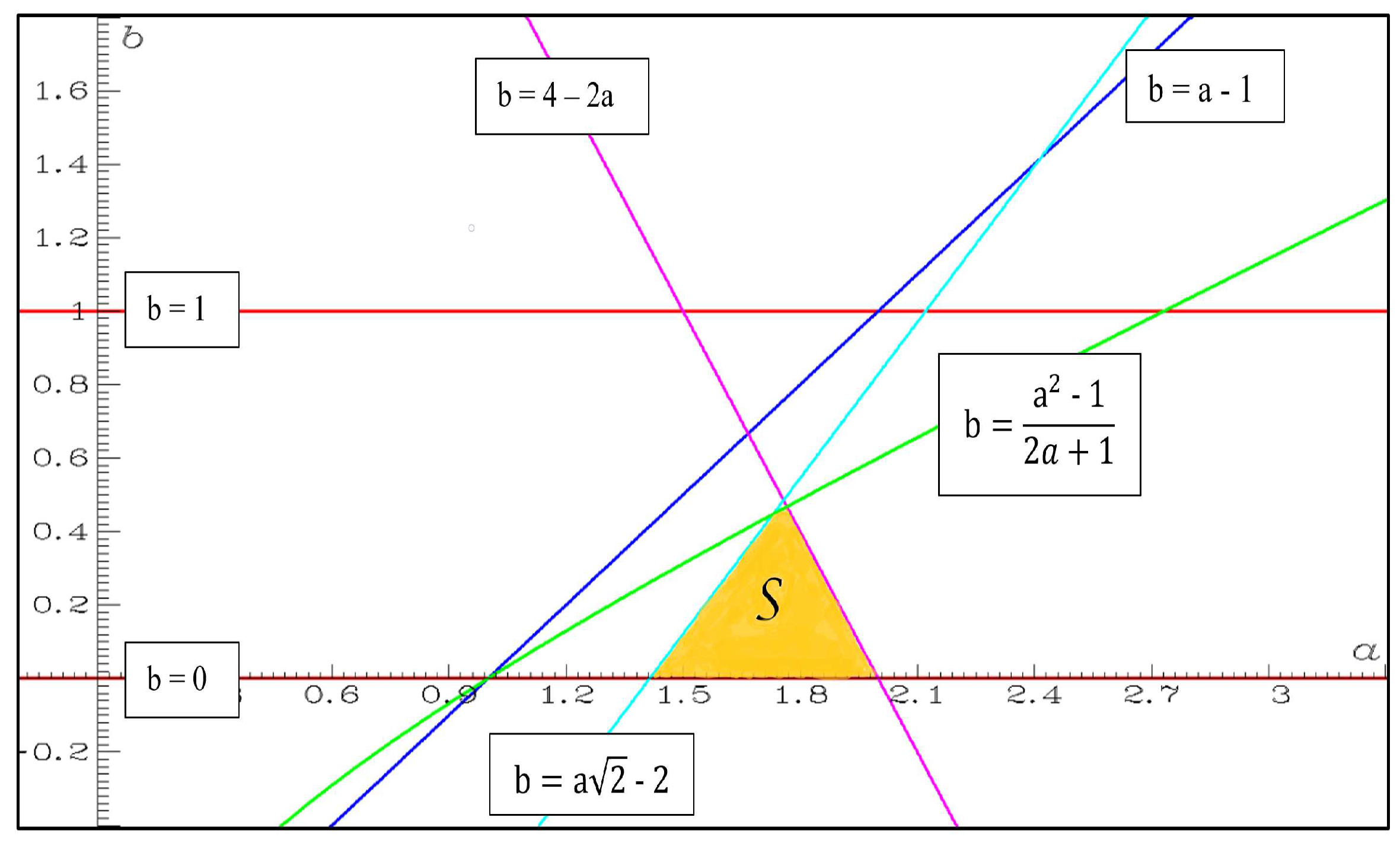

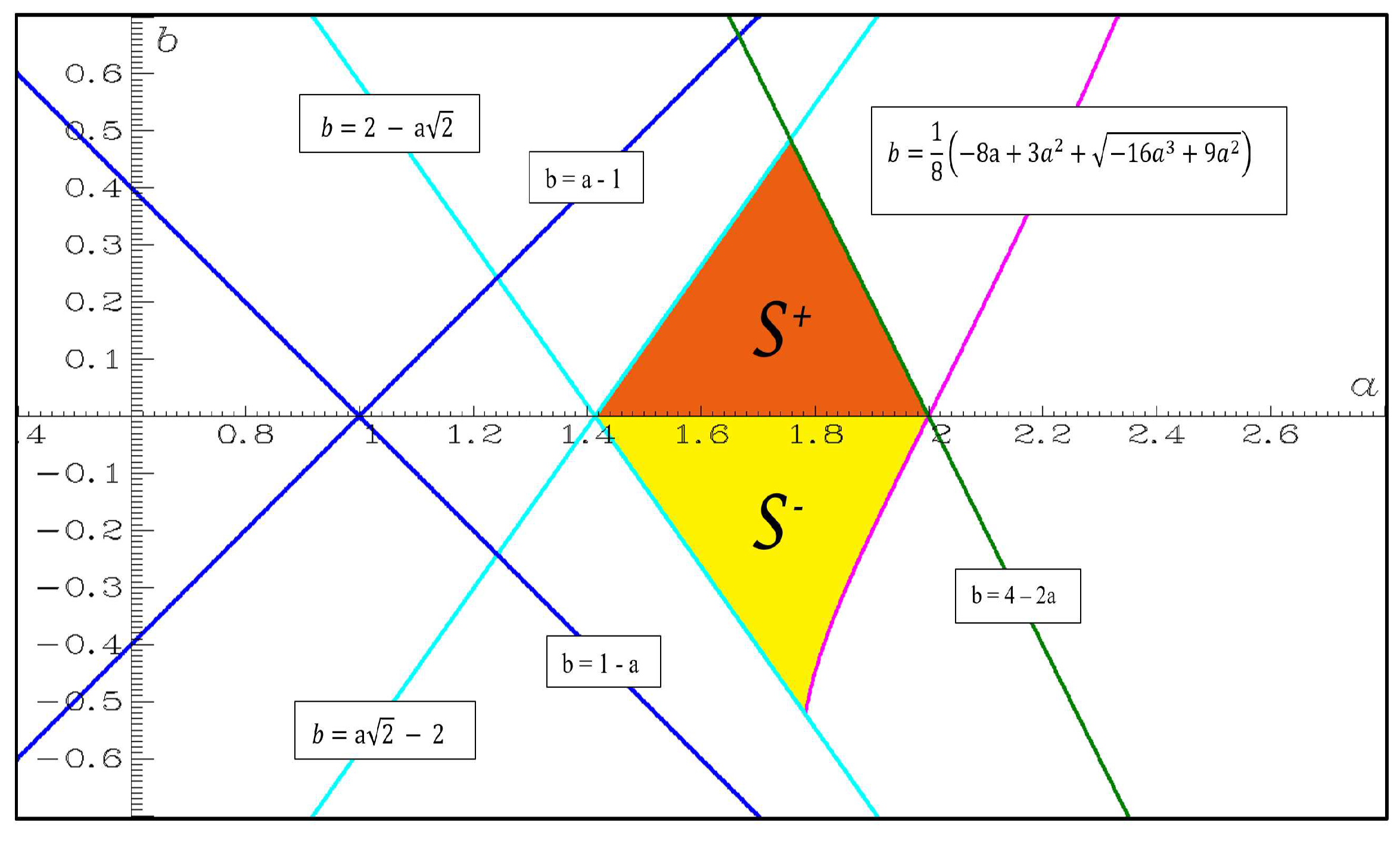

2.1.3. Fixed points, invariant manifolds and basin of attraction

2.1.4. Other dynamical properties of the dissipative map (|b|<1)

- -

- The union of the transversal homoclinic points and weak transversal homoclinic points are dense in .

- -

- All periodic points are hyperbolic.

- -

- The set of periodic points forms a dense set in .

- -

- Any two hyperbolic points forms a transversal heteroclinic cycle or a weak transversal heteroclinic cycle.

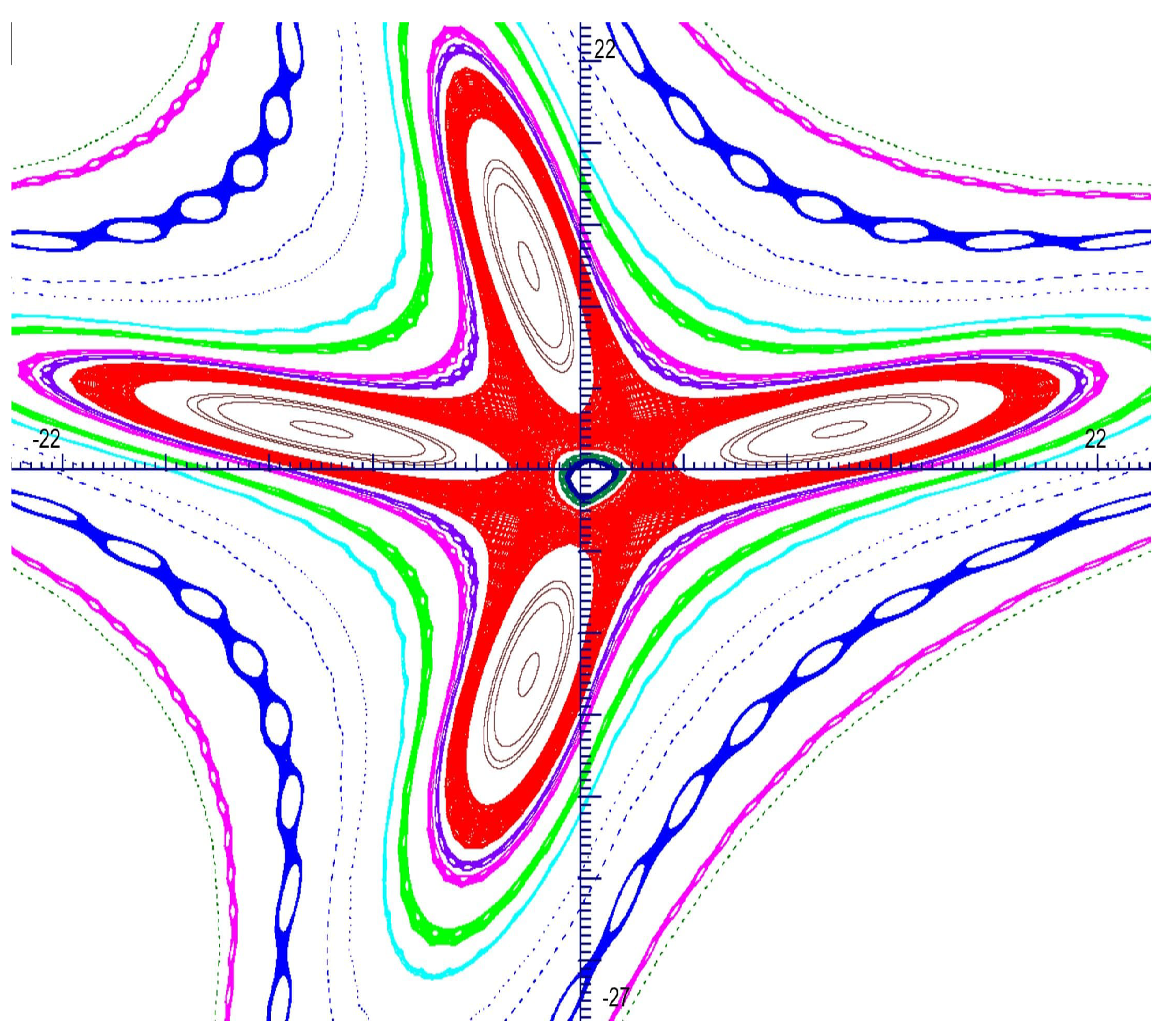

2.1.5. Chaotic properties of the conservative map (|b|=1)

2.2. Generalizations

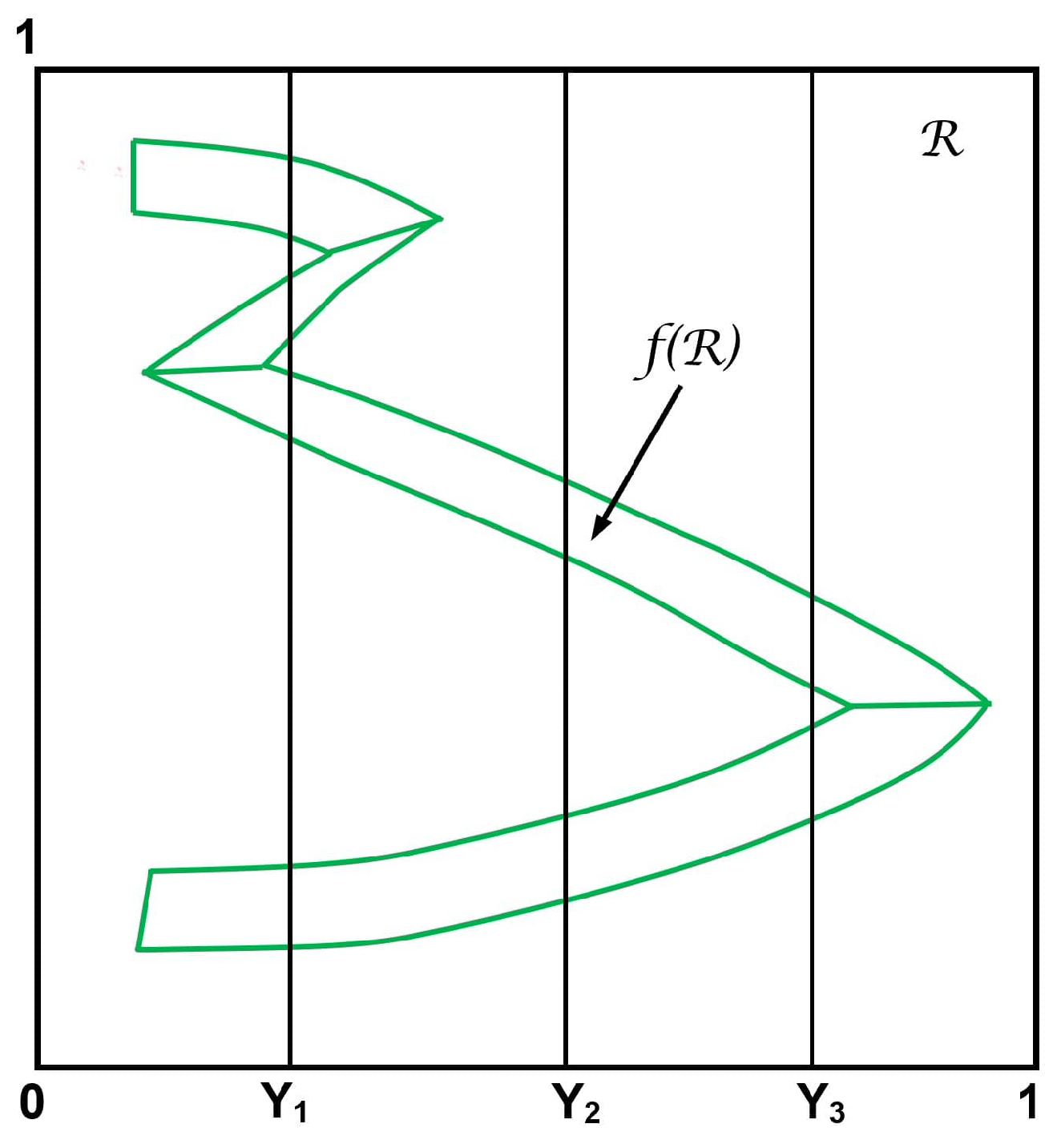

2.2.1. Topological generalizations: Lozi-like maps

- (L.1)

-

There exist such that f is a -diffeomorphism on \ where .From now on, we set .

- (L.2)

-

The norm of the derivative of f is uniformly bounded on , i.e.,,where = sup ; , .

- (L.3)

-

There exist constants and continuous cone-fields , , on such that, for any and any vectors ,

- -

- and

- -

- and

- (S1)

- For every point we have , , and , for .

- (S2)

- For every point and we have for every and for every .

- (S3)

- There exists a smooth curve such that for every we have , the vector tangent to Γ at P belongs to , and the vector tangent to at belongs to . We require that Γ is infinite in both directions.

- (L’.1)

- det for every point and .

- (L’.2)

- There exists a trapping region (for the map F), which is homeomorphic to an open disk and its closure is homeomorphic to a closed disk.

2.2.2. Geometrical generalization: Lozi-type map

2.2.3. Formulas generalization

- (i)

- all solutions converge toward the equilibrium point . Moreover, for a large value of and , they prove that if , then the solution converges toward the equilibrium point and,

- (ii)

- if , then the solution converges towards the periodic solution of period 5.

2.2.4. Fractal mappings

2.2.5. Non-conventional generalization

2.2.6. Network of chaotic maps and chimera

- (i)

- Clustering. A dynamical cluster is defined as a subset of elements that are synchronized among themselves. In a clustered state, the elements in the system segregate into K distinct subsets that evolve in time; i.e., in the th cluster with

- (ii)

- A chimera state consists of the coexistence of one or more clusters and a subset of desynchronized elements.

- (iii)

- A desynchronized or incoherent state occurs when .

3. Three dimensional hyperchaotic attractors

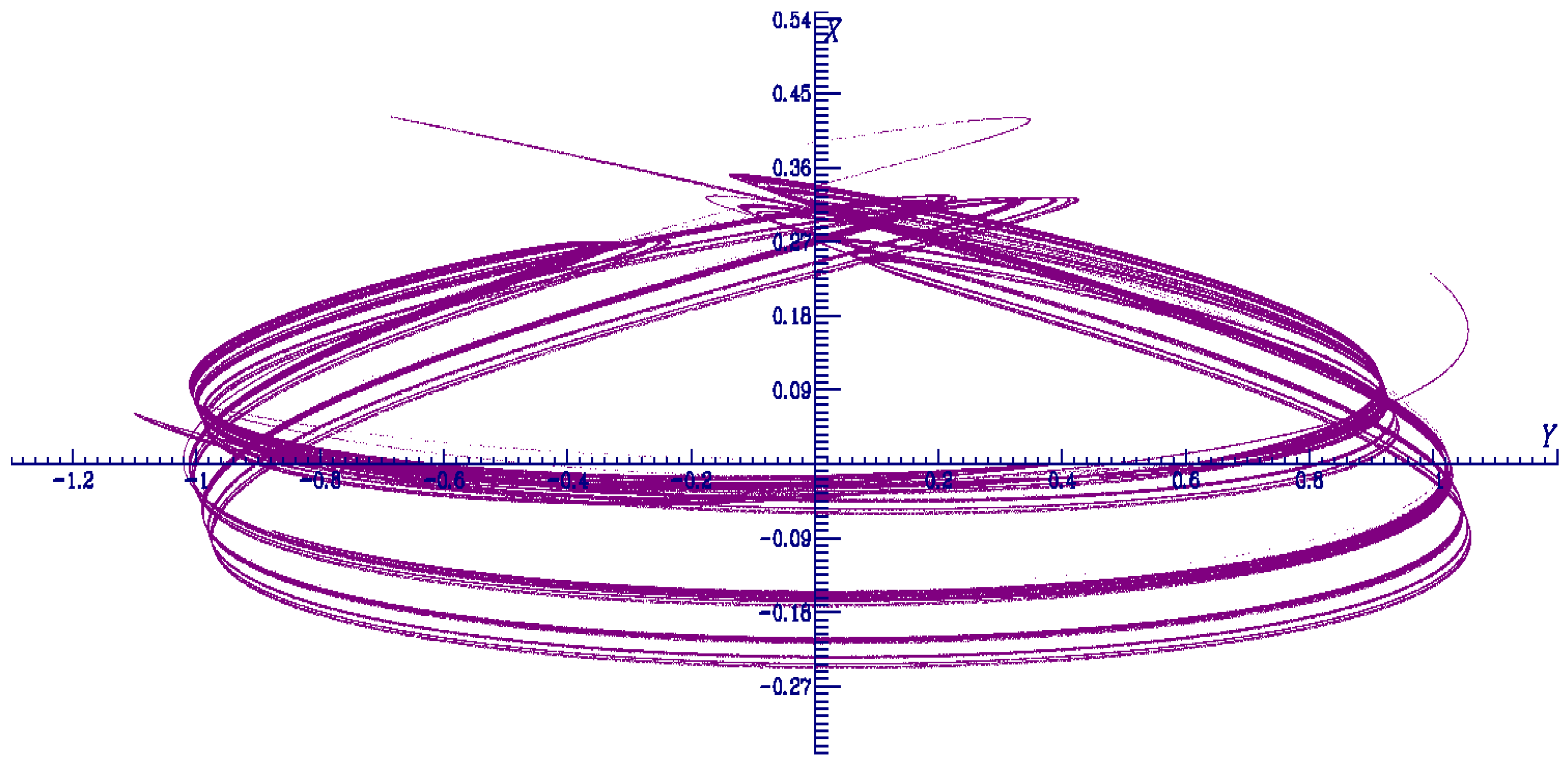

3.1. Ros̎sler hyperchaotic attractors

3.1.1. The "noodle" attractor

3.1.2. The folded "curtain" attractor

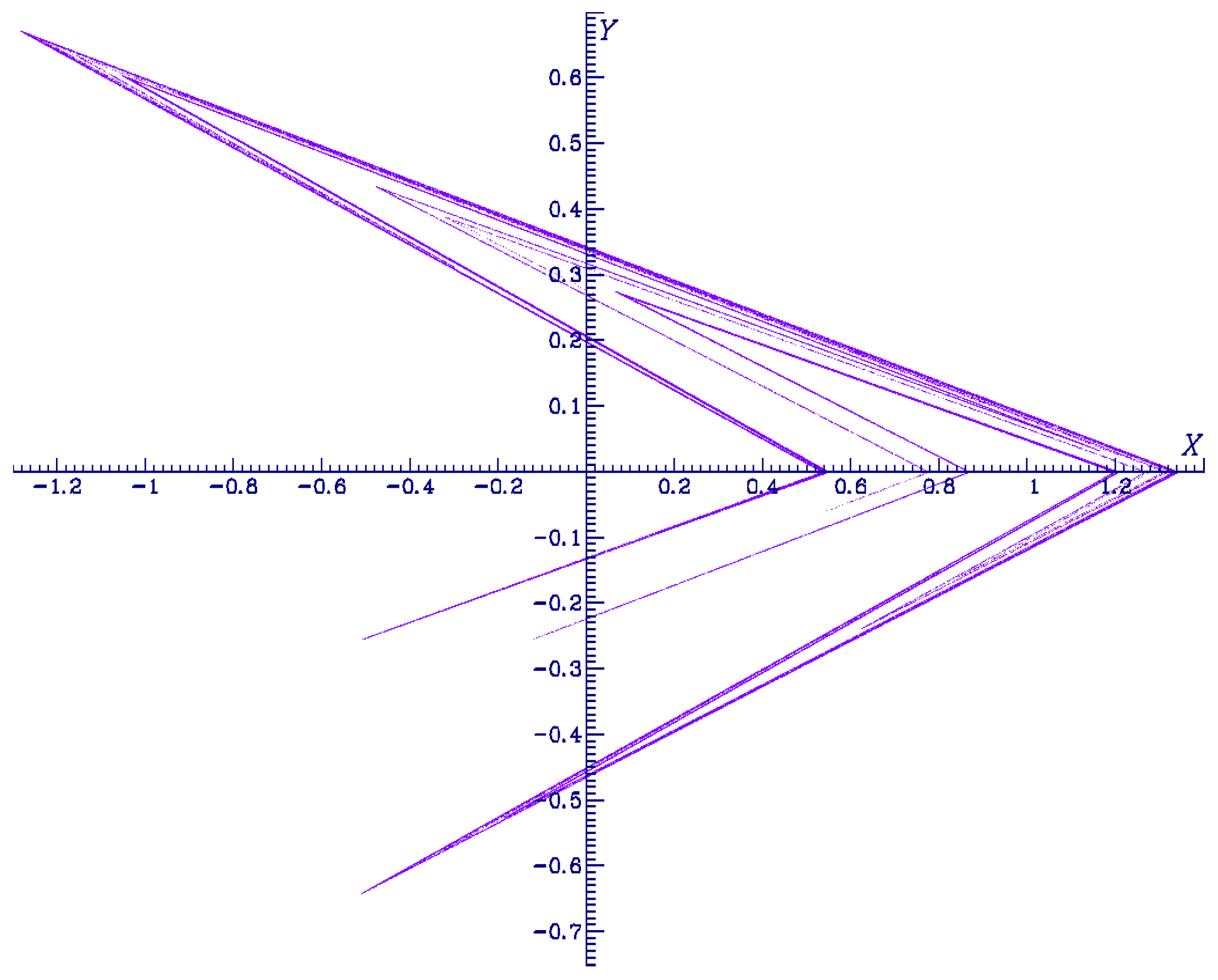

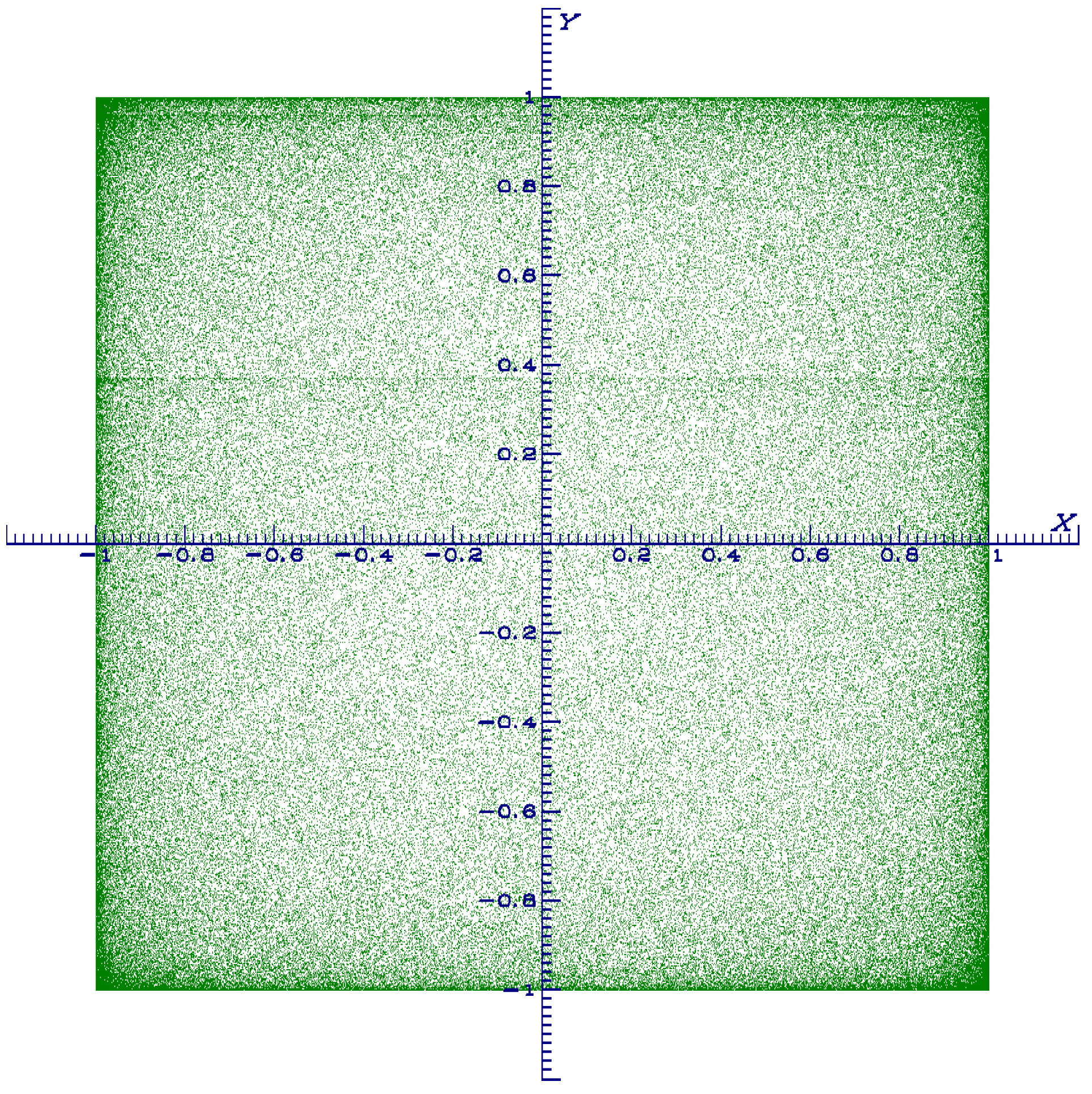

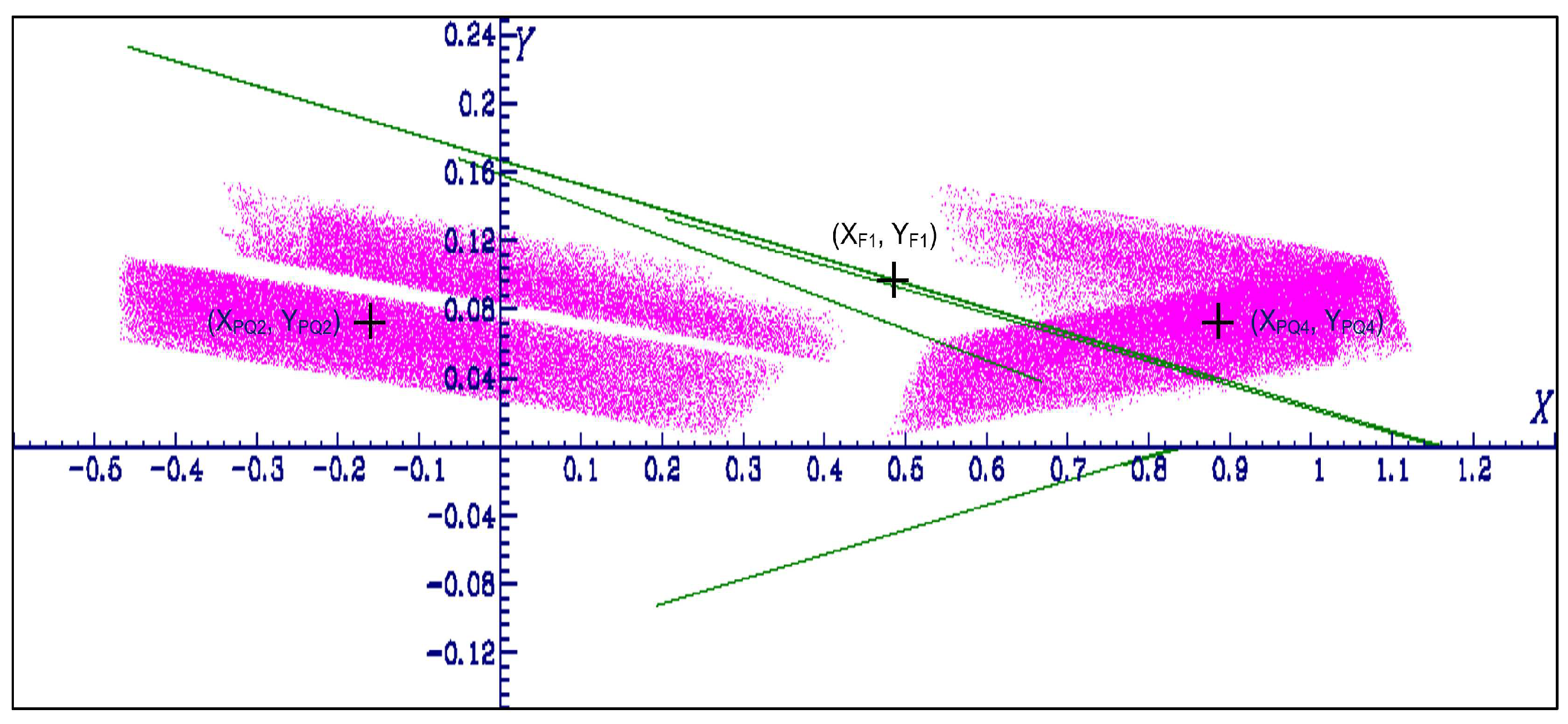

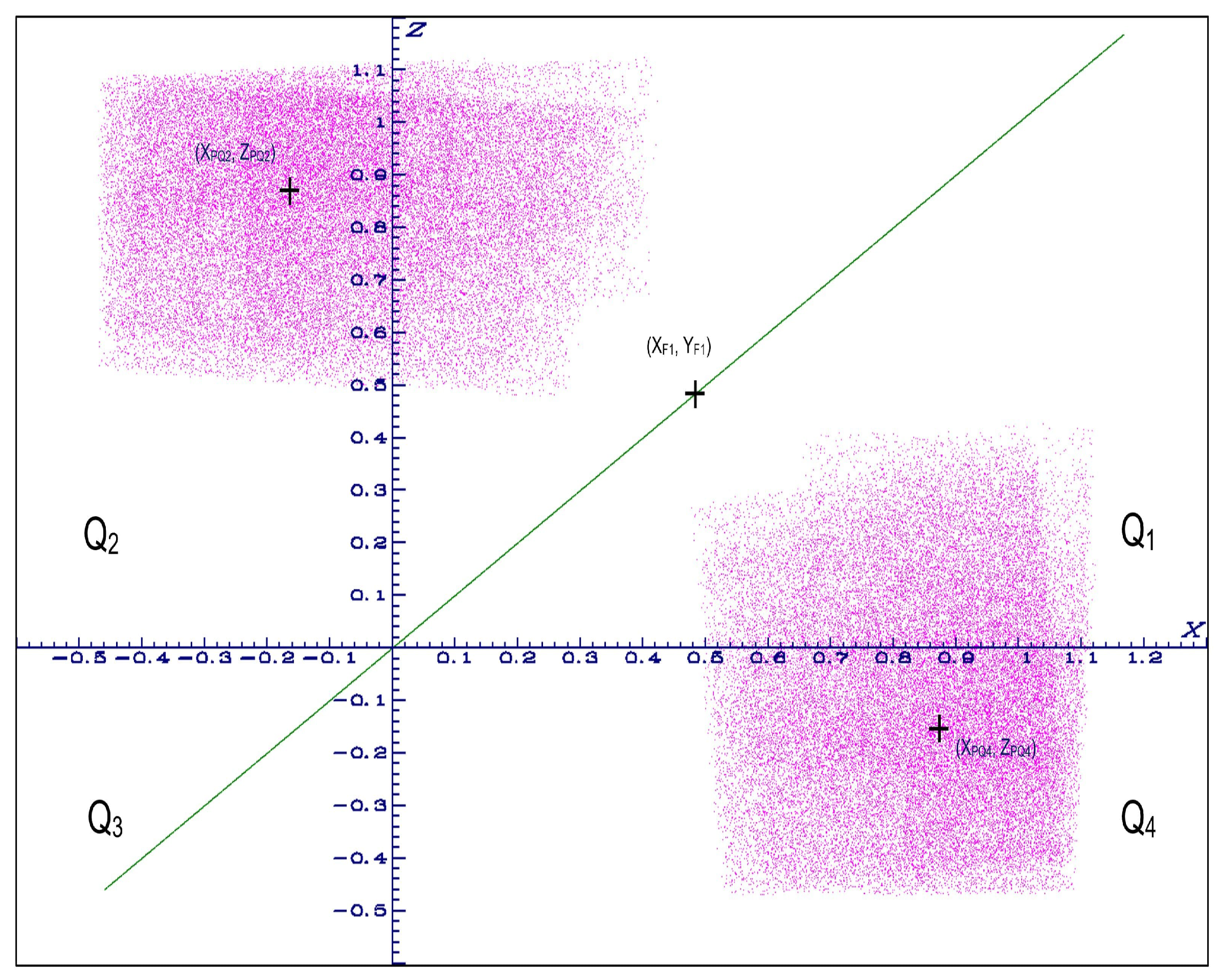

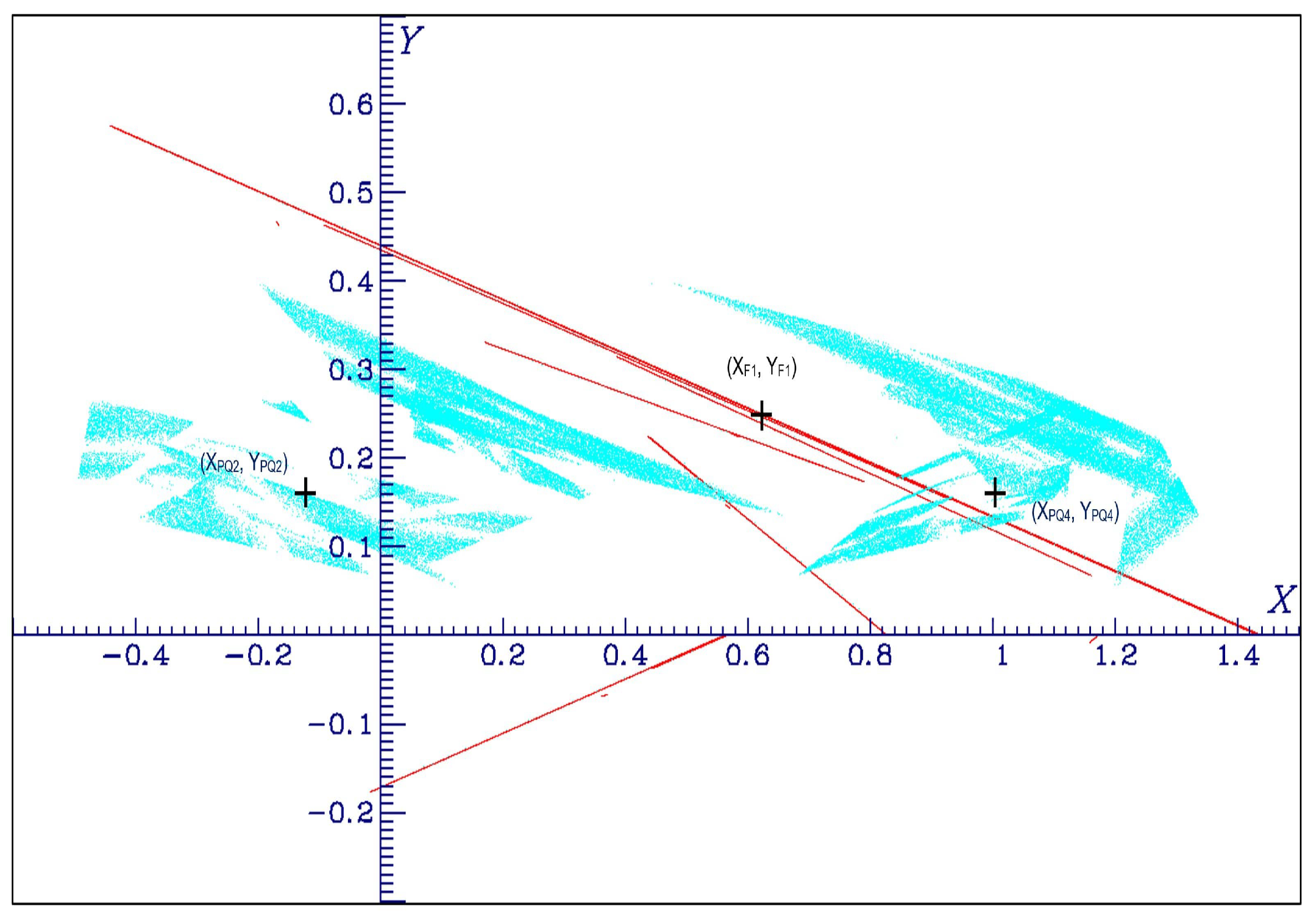

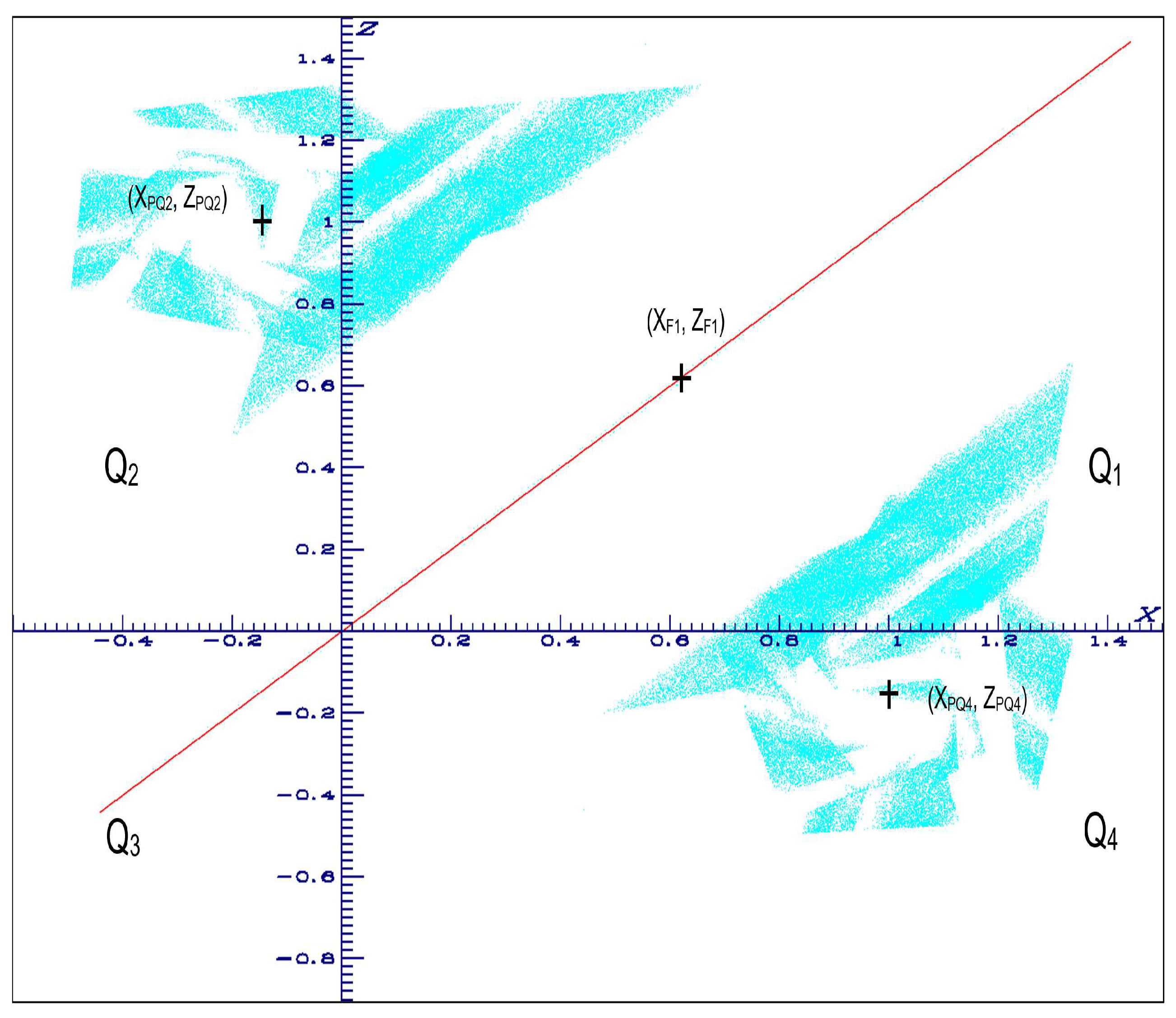

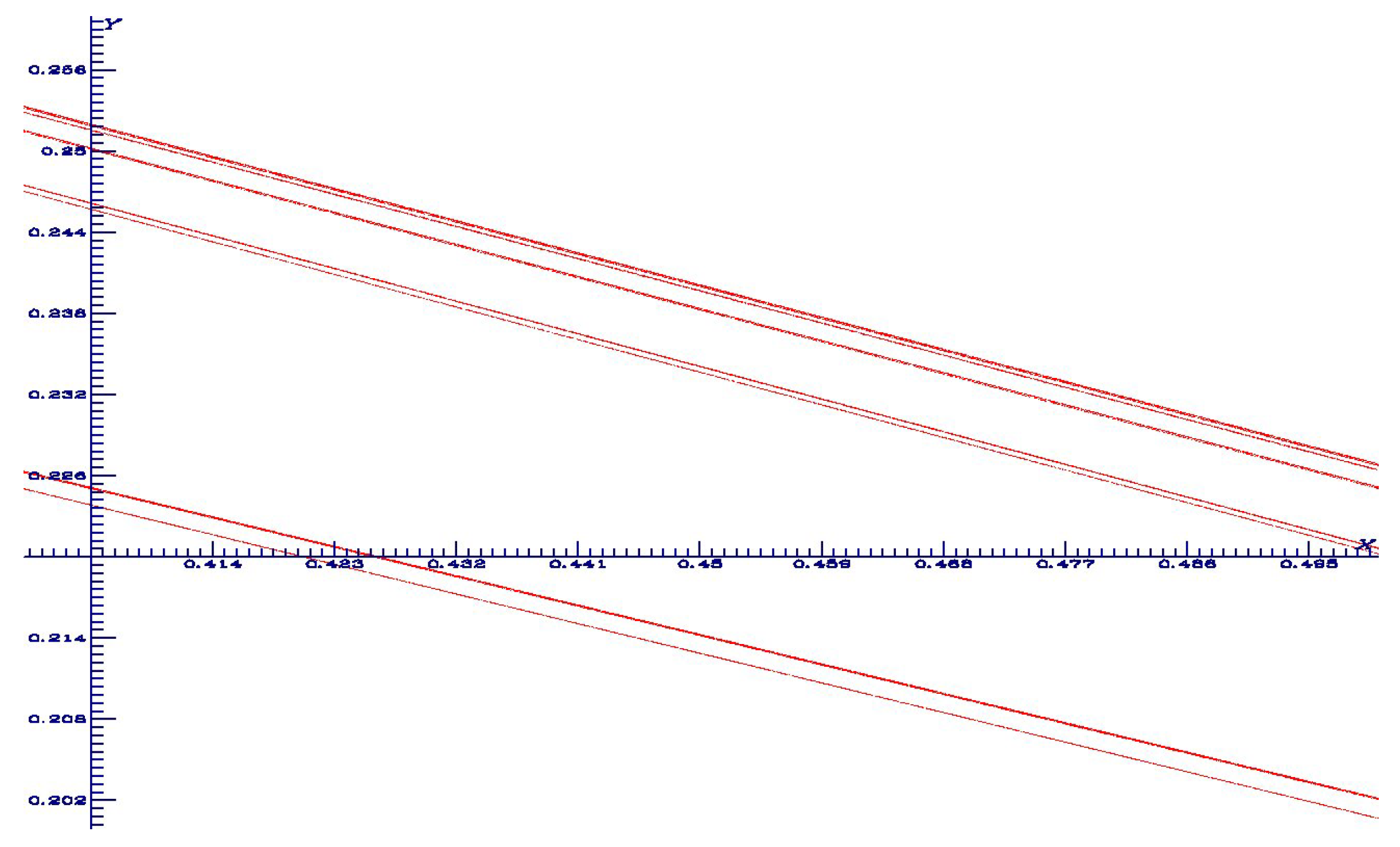

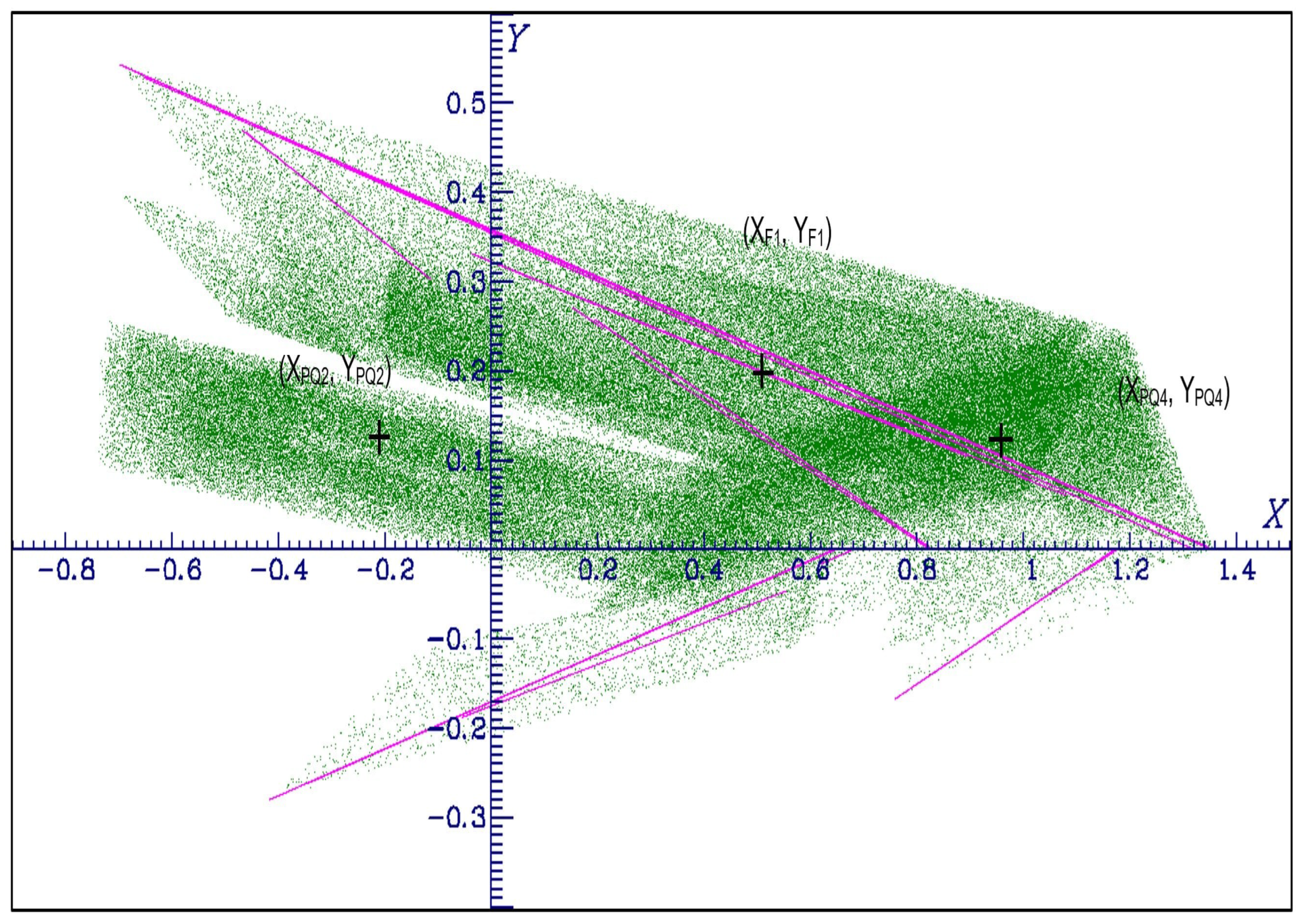

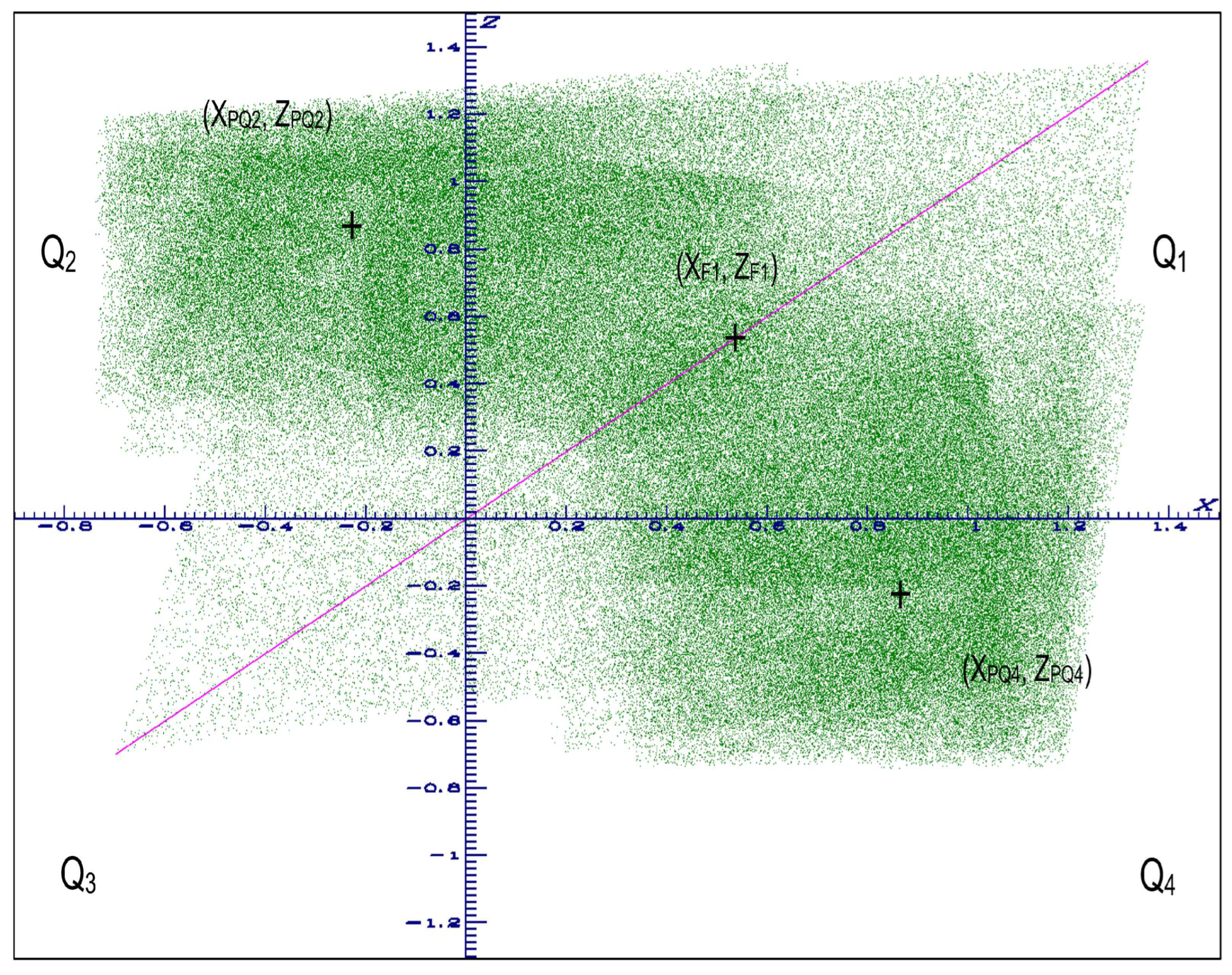

3.2. 3-Dimensional Lozi map with coexistence of thread and sheet hyperchaotic attractor

4. Properties of thread-sheet hyperchaotic attractor

4.1. Basic properties: jacobian and symmetry

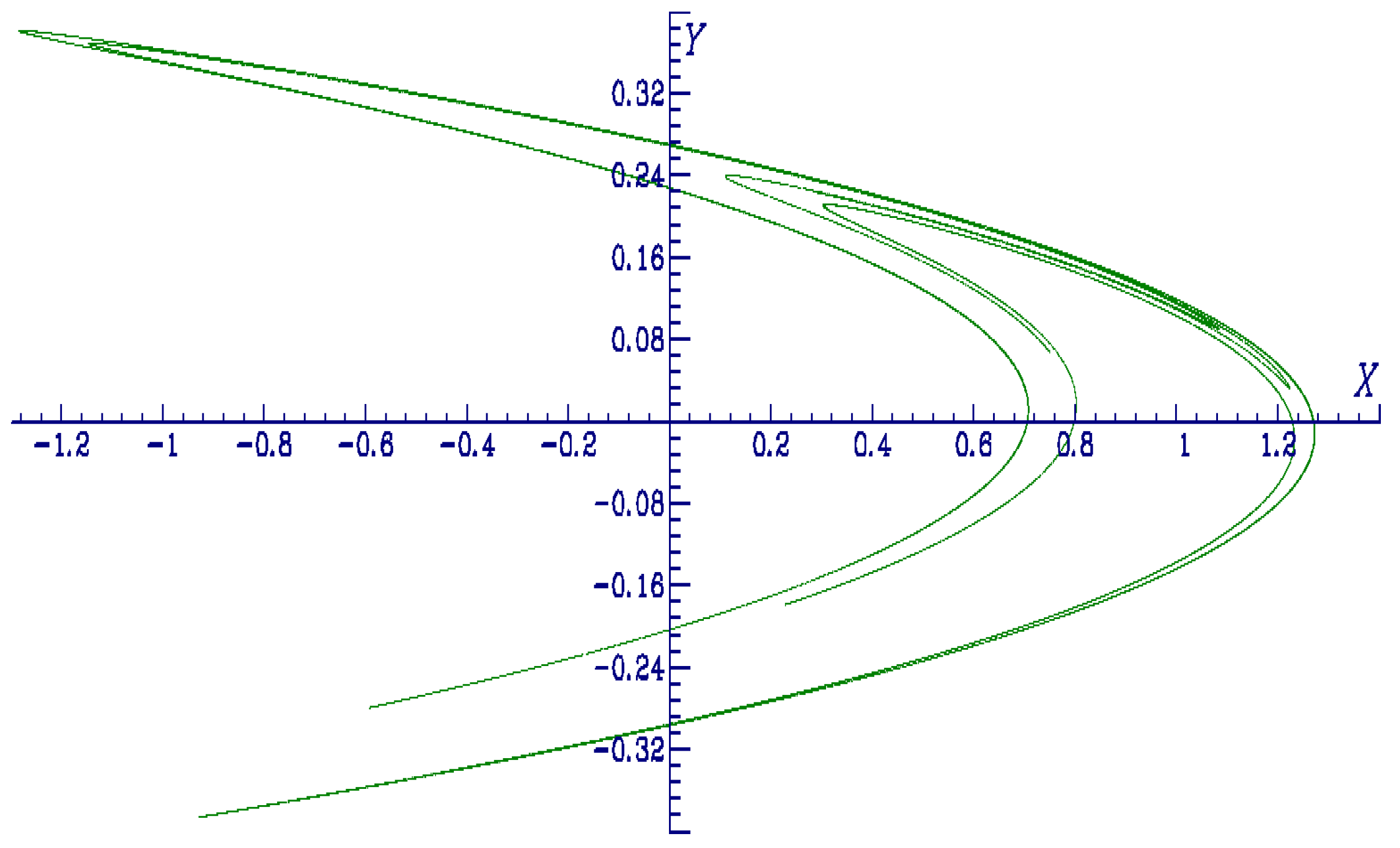

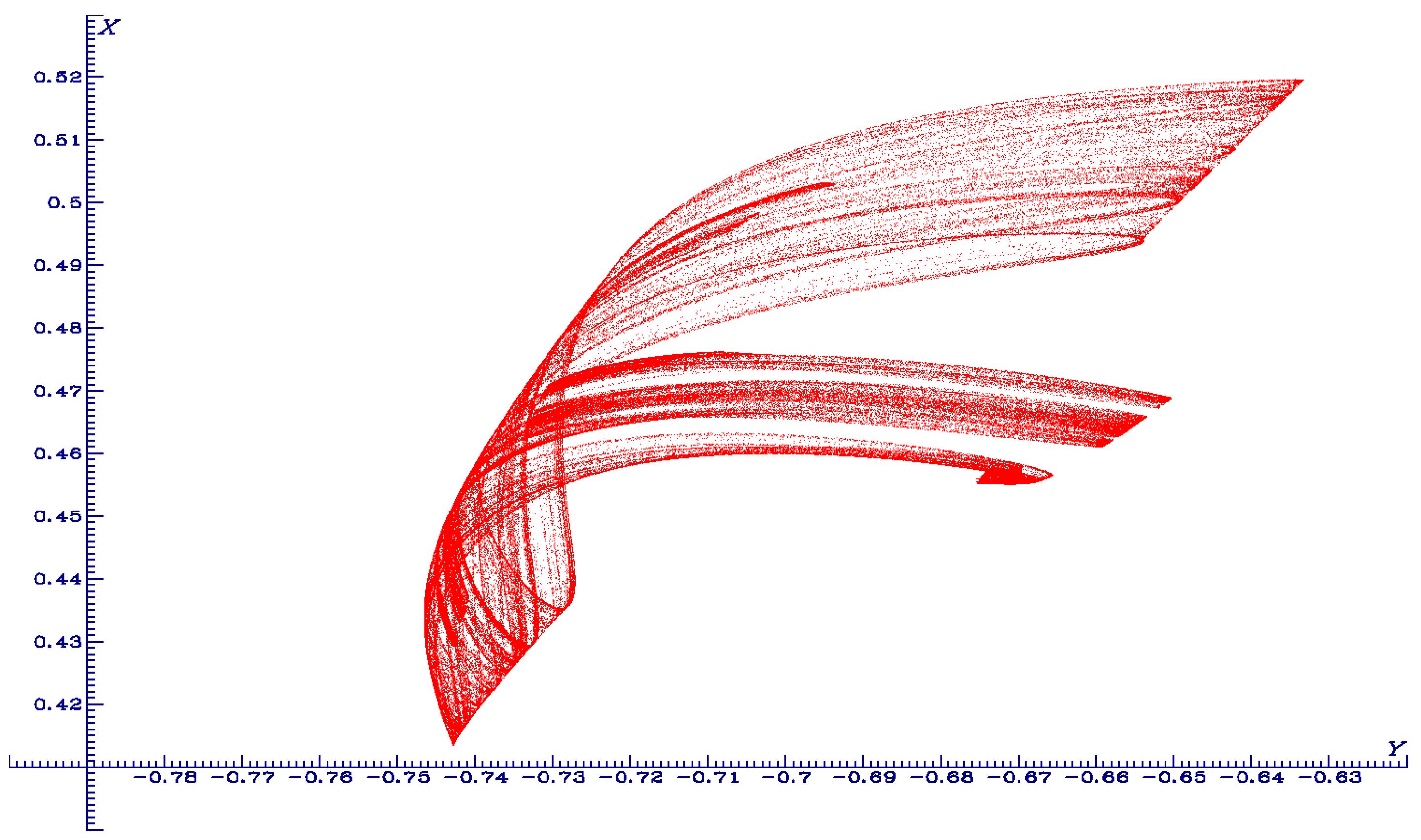

4.2. The thread attractor

4.3. Fixed points and period-two orbits

4.4. Numerical examples

4.4.1. Case a=-1.25, b=0.1, c=-1.25, one piece chaotic attractor, two-pieces hyperchaotic attractor

4.4.2. Case a=-1.0, b=0.2, c=-1.0, multi-pieces chaotic and hyperchaotic attractor

4.4.3. Case a=-1.25, b=0.2, c=-1.25, connected hyperchaotic attractor

4.4.4. Case a=-1.365 and a=-1.369, b=0.36, c=0.6, blow up of the attractor versus the parameter a

4.4.5. Case a=-1.369, b=0.02 to b=0.36, c=0.6, blow up of the attractor versus the parameter b

5. Conclusion

References

- Zeraoulia, E. Lozi mappings — Theory and applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, London, New York, 2013; 309p.

- Letellier, C.; Abraham, R.; Shepelyansky, D. L.; Rössler, O. E.; Holmes, P.; Lozi, R.; Glass, L.; Pikovsky, A.; Olsen, L.F.; Tsuda, I.; Grebogi, C.;Parlitz, U.; Gilmore, R.; Pecora, L. M.; Carroll, T. L. Some elements for a history of the dynamical systems theory. Chaos 2021, Vol. 31, 053110. [CrossRef]

- Ruelle, D. Dynamical systems with turbulent behavior. In Mathematical Problems in Theoretical Physics, Lecture Notes in Physics, edited by G. Dell’Antonio et al. (Springer, 1978), Vol. 80, pp. 341–360; International Mathematics Physics Conference, Roma, 1977. [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, E. N. Deterministic nonperiodic flow. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 1963, Vol. 20, pp. 130–141. [CrossRef]

- Hénon, M. A two-dimensional mapping with a strange attractor. Commun. Math. Phys. 1976, Vol. 50, pp. 69–77. [CrossRef]

- Smale, S. Differentiable dynamical systems. I Diffeormorphisms. Bulletin of American Mathematical Society 1967, vol. 73, pp. 747–817. [CrossRef]

- Lozi, R. Un attracteur étrange (?) du type attracteur de Hénon. Journal de Physique 1978, vol. 39, C5–9–C5–10. [CrossRef]

- Misiurewicz, M. Strange attractors for the Lozi mappings. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1980, vol. 357, pp. 348–358. [CrossRef]

- Misiurewicz, M.; Stimac, S. Symbolic dynamics for Lozi maps. Nonlinearity 2016, vol. 29 pp. 3031-3046 . [CrossRef]

- Kucharski, P. Strange attractors for the family of orientation preserving Lozi Maps. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2211.10296.pdf 2022.

- Baptista, D.; Severino, R.; Vinagre, S. The basin of attraction of Lozi Mappings. International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos 2009.vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 1043-1049. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, Y. Towards a kneading theory for Lozi mappings I: A solution of the pruning front conjecture and the first tangency problem. Nonlinearity 1997 vol. 10 , no. 3, pp. 731-747. [CrossRef]

- Boroński, J.P.; Kucharski, P.; Ou, D.-S. Lozi maps with periodic points of all periods n > 13. Preprint. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366740872_Lozi_maps_with_periodic_points_of_all_periods_n_13 2022.

- Botella-Soler, V.; Castelo, J. M.; Oteo, J. A.; Ros, J. Bifurcations in the Lozi map. J. Phys. A: Math.Theor. 2011, vol. 44, no. 30, p. 305101. [CrossRef]

- Sushko, I.; Avrutin, V.; Gardini, L. Center Bifurcation in the Lozi Map. International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos 2021.vol. 31, No. 16, p. 2130046. [CrossRef]

- Glendinning, P.A.; Simpson, D.J.W. Chaos in the border-collision normal form: A computer-assisted proof using induced maps and invariant expanding cones. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2022, vol. 434, p. 127357. [CrossRef]

- Collet, P.; Levy, Y. Ergodic properties of the Lozi mappings. Commun. Math. Phys. 1984, vol. 93, pp. 461–482. [CrossRef]

- Rychlik, M. Invariant Measures and the Variational Principle for Lozi Mappings. In: Hunt, B.R., Li, TY., Kennedy, J.A., Nusse, H.E. (eds) The Theory of Chaotic Attractors2004. Springer, New York, NY. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Liu, Z. The Geometric Structure of Strange Attractors in the Lozi Map. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation 1998, vol. 3, Iss. 2, pp. 119-123. [CrossRef]

- Afraimovich, V. S.; Chernov, N. I.; Sataev, E. A. Statistical properties of 2-D generalized hyperbolic attractors. Chaos 1995 vol. 5, pp. 238-252. [CrossRef]

- Zheng W.-M. Symbolic Dynamics for the Lozi Map. Chaos. Solitons & fractals 1991 vol. 1, No 3, pp. 243-248. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, Y. Towards a kneading theory for Lozi mappings II: Monotonicity of the Topological Entropy and Hausdorff Dimension of Attractors. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1997 ,vol. 190 , pp. 375–394. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, Y.; Sands. D. Monotonicity of the Lozi family near the tent-maps. Comm. Math. Phys. 1998, Vol. 198(2) pp.397-406. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho (de), A.; Hall, T. How to prune a horseshoe. Nonlinearity 2002, Vol. 15 pp. R19-R68. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, K.; Chen, M.; Bao, B. Coexisting Infinite Orbits in an Area-Preserving Lozi Map. Entropy 2020, vol. 22 , pp. 1119. [CrossRef]

- Natiq, H.; Banerjee, S.; Ariffin, M.R.K.; Said, M.R.M. Can hyperchaotic maps with high complexity produce multistability? Chaos 2019, vol. 29 , pp. 011103. [CrossRef]

- Zhusubaliyev, Z.T.; Mosekilde, E. Multistability and hidden attractors in a multilevel DC/DC converter. Math. Comput. Simul. 2015, vol. 109, pp. 32–45. [CrossRef]

- Bao, B.C.; Li, H.Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, M. Initial-switched boosting bifurcations in 2D hyperchaotic map.Chaos 2020, vol.30, p. 033107. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-P.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Z.-C.; Jiang, H.-B.; Bi, Q.-S. A novel class of two-dimensional chaotic maps with infinitely many coexisting attractors. Chin. Phys. B 2020, vol.29, p. 060501. [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Hua, Z.Y.; Wang, N.; Zhu, L.; Chen, M.; Bao, B.C. Initials-boosted coexisting chaos in a 2D Sine map and its hardware implementation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, vol.17, Iss. 2, pp. 1132 - 1140. [CrossRef]

- Lopesino, C.; Balibrea, F.; Wiggins, S. R.; Mancho, A. M. The Chaotic Saddle in the Lozi Map, Autonomous and Nonautonomous Versions. International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos 2015, vol. 25, no. 13, p.1550184. [CrossRef]

- Young, L.-S. A Bowen-Ruelle measure for certain piecewise hyperbolic maps. Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 1985, Vol. 287, pp. 41-48.

- Misiurewicz, M.; Stimac, S. Lozi-like maps. Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems 2018, Vol. 38(6), pp. 2965-2985. [CrossRef]

- Juang , J.; Chang, Y.-C. Boundary influence on the entropy of a Lozi-type map. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2010 vol. 371 , pp. 728-740. [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, A. Orbit shifted shadowing property of generalized Lozi map. Taiwanese Journal of Mathematics 2010, Vol. 14, No. 4 pp. 1609-1621 https://www.jstor.org/stable/43834956.

- Aiewcharoen, B.; Boonklurb, R.; Konglawan, N. Global and Local Behavior of the System of Piecewise Linear Difference Equations and Where . Mathematics 2021, vol. 9, 1390. [CrossRef]

- Mammeri, M.; Kina, N. E. Dynamical properties of solutions in a 3-D Lozi map. Proceedings of the 6th International Arab Conference on Mathematics and Computations (IACMC2019), Aliaa Burqan, Osama Ababneh and Shawkat Alkhazaleh (eds.), Zarqa University, Jordan, pp.27-33.

- Joshi, Y.; Blackmore, D.; Rahman, A. Generalized Attracting Horseshoes and Chaotic Strange Attractors. [CrossRef]

- Bilal, S.; Ramaswamy, R. A higher-dimensional generalization of the Lozi map: bifurcations and dynamics. J. Difference Equations and Applications 2022, 12 p. [CrossRef]

- Lozi, R. Strange attractors: a class of mapping of R2 which leaves some Cantor sets invariant. In Intrinsic stochasticity in plasmas, 1979 Laval, G.; Gresillon, D. (eds.), Cargese, 17-23 June 1979, Les Editions de Physique, Orsay, France, pp. 373-381.

- Chutani, M.; Rao, N.; Nirmal Thyagu, N.; Gupte, N. Characterizing the complexity of time series networks of dynamical systems: A simplicial approach. Chaos 2020 vol. 30, p. 013109 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Khennaoui A.-A.; Ouannas, A.; Bendoukha, S.; Grassi, G.; Lozi, R.; Pham, V.-T. On fractional–order discrete-time systems: Chaos, stabilization and synchronization. Chaos, Solitons and Fractals 2019, vol.119, pp. 150-162. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R. W.; Baleanu, D. Global stability of local fractional Hénon-Lozi map using fixed point theory. AIMS Mathematics 2022, Vol. 7(6), pp. 11399–11416. [CrossRef]

- Aliwi, B. H.; Ajeena, R. K. K. A performed knapsack problem on the fuzzy chaos cryptosystem with cosine Lozi chaotic map. AIP Conference Proceedings 2023, vol. 2414,, pp. 040047. [CrossRef]

- Aliwi, B. H.; Ajeena, R. K. K. On Fuzzy Sine Chaotic Based Model in Security Communications. Journal of Positive School Psychology 2022, Vol. 6, No. 4, pp. 8127 – 8133. https://journalppw.com/index.php/jpsp/article/view/5169.

- Cano, A. V.; Cosenza, M. G. Chimeras and clusters in networks of hyperbolic chaotic oscillators. Phys. Rev. E 2017, Vol. 95, pp. 030202(R). [CrossRef]

- Semenova, N.; Vadivasova, T.; Anishchenko, V. Mechanism of solitary state appearance in an ensemble of nonlocally coupled Lozi maps. Eur. Phys. J. Special Topics 2018, Vol. 227, pp.1173-1183. [CrossRef]

- Anishchenko, V.; Rybalova, E.; Semenova, N. Chimera States in two coupled ensembles of Henon and Lozi maps. Controlling chimera states. AIP Conference Proceedings 2018, Vol. 1978, pp. 470013-1–470013-4. [CrossRef]

- Rössler, O. E.; Hudson, J. L.; Farmer, J. D. Noodle-map chaos: a simple example. In: Schuster, P. (eds) Stochastic Phenomena and Chaotic Behaviour in Complex Systems. Springer Series in Synergetics, 1984,vol 21. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Rössler, O. E. An equation for hyperchaos. Physics Letters 1979, Vol. 71A, no 2-3, pp. 155-157. [CrossRef]

- Anosov, D.V. et al. Dynamical Systems IX: Dynamical Systems with Hyperbolic Behaviour 1995, (Encyclopedia of Mathematical Sciences: Vol. 9), Springer. [CrossRef]

- Elhadj, Z.; Sprott, J. C. Robust Chaos and Its Applications 2011, Singapore: World Scientific Series on Nonlinear Science Series A: Volume 79. [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, S. P. Some lattice models with hyperbolic chaotic attractors. Russian Journal of Nonlinear Dynamics 2020, Vol. 16, No 1, pp. 13–21. [CrossRef]

- Kilassa Kvaternik, K. Tangential homoclinic points locus of the Lozi maps. Doctoral thesis 2022, University of Zagreb, 110 p. https://repozitorij.pmf.unizg.hr/islandora/object/pmf:11546.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).