1. Introduction

Aging of the global population is increasing. In 2030, one in six people in the world will be over 65 years old. By 2050, two billion people are expected to be older than 65 years, [

1] and the number of people over 80 will have tripled, reaching 426 million.[

1,

2] This has several implications for health and social care planning. [

3]

Frailty is the most complex expression of aging, and it is defined as a state of vulnerability and having a poor recovery rate following a stressful event, which leads to an increased risk of delirium, disability, hospitalization, and death. [3-5] Frail patients usually have high health care needs, [

6] and are a growing group in the emergency departments (ED) of hospitals.[

6,

7]

Frailty assessment is a keystone in geriatric care. It is common in older patients in both hospital wards and in EDs, with reported prevalence rates between 21 and 62%.[

8,

9,

10,

11] In these two settings, frailty assessment is helpful for identifying the needs of patients and providing specific, tailored, and effective care.[

12,

13,

14,

15] A large number of tools have been proposed for frailty assessment, each with different characteristics and limitations, and they have all been validated in different healthcare setting. [

10,

11] Despite this, frailty assessment is not routinely performed in ED. [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] Barriers include the lack of ED clinical guidelines on frailty as well as the unfeasibility of conducting the assessment in a stressed setting.

Short Stay Units (SSU) are emergency support hospitalization units, which are useful for avoiding or reducing admissions. [

23,

24,

25] The admission criteria includes patients with medical pathology, a clear diagnosis, or a stable condition that does not require close monitoring or invasive treatment, and with an expected length of stay under 72 hours. [24-27] Over the years, the clinical profile of patients admitted to SSUs has changed significantly as a result of a change in the age demographic. [

26] Patients admitted to an SSU are now older, and they have more comorbidities and polypharmacy. Frailty assessment in an SSU may now be useful, then, but it is not routinely used, and, indeed, we did not find any work in which frailty has been explored in this setting. SSU-EDs are units with a heavy workload, and there are no recommendations on the best tools to assess frailty in this particular setting.

The Frail-VIG index (FI-VIG (VIG is the Spanish/Catalan abbreviation for Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment)) is a frailty index (FI) developed by Amblàs et al. (C3RG, Chronicity Research Group of Central Catalonia), which offers the possibility of conducting a rapid CGA of individuals as well as calculating their grade of frailty, and which was initially validated in a cohort of patients over 85 years of age in an Acute Geriatric Unit (UGA) [

11]. The index consists of a 22-item deficit rating scale. As the authors have noted, the results describe a simple and quick tool (it is completed in 5–10 minutes) with an excellent discriminative and predictive capacity in relation to mortality, and it performs a multidimensional assessment of the patient.

The scale has subsequently been validated in the context of intermediate care or health care hospitals [

28,

29] as well as in the community setting with the same results. The authors keep it available in different languages and free of charge at

https://www.c3rg.com/index-fragil-vig.

We think that this tool, which addresses more dimensions than other shorter tools recommended in ED, even though it requires a little more time, is applicable in SSUs and can provide significant clinical value. The aim of our study is to analyze the utility of FI-VIG in a new scenario––an ED SSU.

2. Materials and Methods

An observational, single-center, prospective cohort study was conducted in the SSU of the ED of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona, Spain), a tertiary and university urban hospital with a 550-bed center. The SSU in this hospital has 36 beds, reporting to the ED, and it had 2,243 admissions in 2021.

The admission criteria in the SSU includes patients with a medical pathology but with a stable condition that does not require close monitoring or invasive treatment, and the expected length of stay should be under 72 hours. The most frequent diagnoses are heart failure, acute chronic lung disease, urinary tract infection, respiratory infections, pyelonephritis, contusions, and non-surgical fractures of the elderly, among others.

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee under sponsor code IIBSP-FRA-2020-74. The CEIC considered the request for informed consent unnecessary because it was a registry of a validated scale and a non-interventional study. All patients admitted to the SSU were over 65 years old between March 1, 2021 and April 30, 2021, and they were consecutively included. Due to the characteristics of the study, and since it was an exploratory trial (due to the lack of previous information and the innovative nature of the research topic), a sample size calculation was not performed. Patients were included consecutively for 2 months, which was considered a reasonable period to obtain a representative sample, depending on the participants' availability. Only patients admitted for end-of-life care treatment were excluded from the study. After admission, patients were followed up for one year. Follow-up was performed by consultation with the Shared Health Record of Catalonia (HC3) and comprised a telephone call to the patient or carer after 12 months. There was no loss to follow-up.

The research team consisted of two attending physicians from the ED, the SSU chief nurse, and four nurses. FI-VIG support was used (available at

https://en.c3rg.com/index-fragil-vig). After initial training by the principal investigator, one of the nurses assessed IF-VIG within the first 24 hours of admission, taking into account, as determined by the index, the patient's situation in the 30 days prior to admission.

Based on the FI-VIG

https://en.c3rg.com/index-fragil-vig, patients were categorized into non-frail (<0.2), mild frailty (0.2–0.36), moderate frailty (0.36–0.55), and advanced frailty (>0.55).

The study variables were demographic and administrative data (date of birth, sex, date of admission to the short-stay unit, discharge date from the unit, and reason for discharge) as well as clinical data (comorbidities, functional and cognitive status, social status, and geriatric syndromes).

Following the methodology recommended by the authors of the scale, the binary variables were scored as "0" for absence and "1" for presence of deficits. Money management, telephone use, and medication management were assessed as instrumental activities of daily living. Weight loss of more than 5% in 6 months was assessed as a nutritional marker; the presence of depressive syndrome, insomnia, and anxiety were assessed as emotional markers; and the presence of social vulnerability was assessed as a social marker. The presence of pain and dyspnea were considered as symptoms that met the severity criteria. Delirium, falls, ulcers, polypharmacy, and dysphagia were assessed as geriatric syndromes. Finally, the existence of chronic diseases was recorded as "1", and in the case of advanced chronic disease, according to the NECPAL Test (

NECesidades PALiativas in Spanish, palliative needs), [

30] 2 points were assigned. In relation to ordinary variables, the Barthel index [

31] was used in four categories according to the absence of dependence or mild, moderate–severe, or severe dependence. Cognitive impairment was classified as 0 points with no impairment, 1 point was classed as mild/moderate impairment, and 2 points classed as severe/very severe impairment. Mortality was monitored at admission, at 1 month and 6 months, and then, finally, at 1 year through HC3 and telephone calls.

The result of the FI-VIG of each patient was not communicated to the healthcare team in order not to modify clinical practice or perform any intervention at this stage of the study.

Categorical variables were described as the frequency and the percentage of the available data while quantitative variables were described as the mean and standard deviation (SD). Descriptive statistics of the variables analyzed were performed using SPSS. Statistical significance (95% confidence interval/p < 0.05) for the variables between patients alive/dead was determined by means of mean contrasts (for quantitative variables) and proportion contrasts (for qualitative variables). For survival analysis, the log-rank test was used to compare survival curves according to the FI-VIG value and ROC curve analysis in order to determine the prognostic capacity of FI-VIG for 12-month mortality.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive analysis of the cohort

Of the 501 patients admitted to the SSU during the study period, 323 were over 65 years old. Of these, 21 had been admitted for end-of-life care and were excluded. A total of 302 patients were included in the study, whose mean age was 83 years, and 56% of them were women (n=169). A total of 5% of the patients (n=15) lived in a nursing home.

A total of 60.9% of the patients had independence regarding the basic activities of daily living (ADLs, n=184). Mild–moderate dependence for ADLs was observed in 23.5% (n=71), moderate–severe in 10.3% of patients (n=31), and absolute dependence in 5.3% (n=16). Mild–moderate cognitive impairment GDS<5 (n=44) and moderate–severe cognitive impairment GDS>6 (n=6) accounted for 14.6% of patients.

In-hospital mortality of the cohort was 3% (n=9), and at 1 month it was 12.3% (n=37), at 6 months it was 20.6% (n=62), and at 1 year it was 23.2% (n=70).

3.2. Frailty assessment

Characteristics of patients admitted to the SSU according to their frailty are presented in

Table 1.

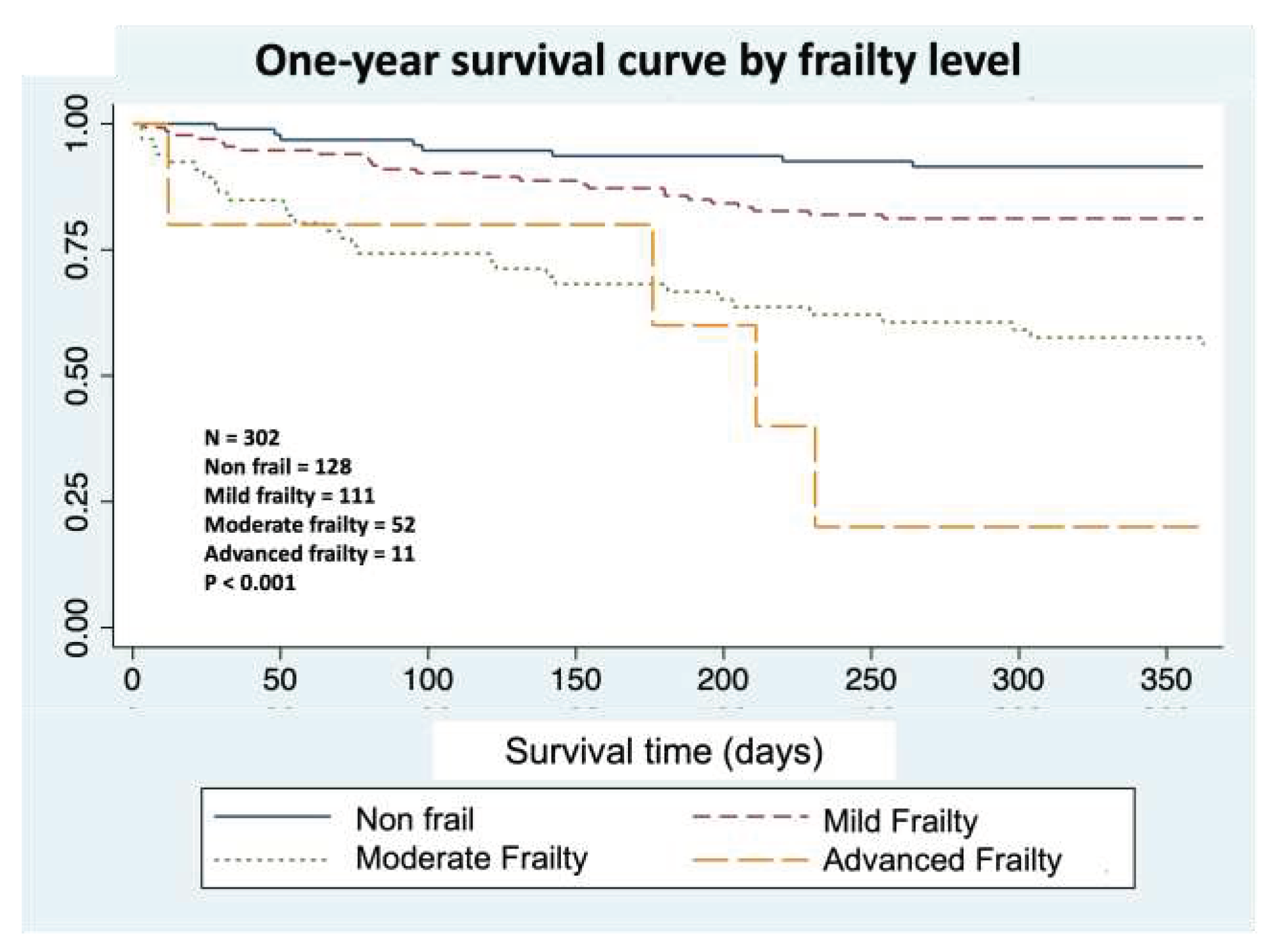

Of the 302 patients included, 128 (42.4%) were categorized as non-frail and 174 (57.6%) were categorized as frail. Of these, 111 (36.8%) had mild frailty, 52 (17.2%) had moderate frailty, and 11 (3.6%) had advanced frailty.

3.3. Time of test execution

3.4. Mortality analysis

Table 2 shows the differences in the percentage of mortality between the frailty groups.

Table 2. Based on the Frail-VIG index, patients were classified into non-frail (< 0.2), mild frailty (0.2–0.36), moderate frailty (0.36–0.55), and advanced frailty (0.55–0.7).

Figure 1 shows the correlation between mortality at 1 year and FI-VIG using the log-rank test, comparing the survival curves according to the value of FI-VIG, and discretized by the previously described intervals.

4. Discussion

Our work shows that FI-VIG is a reliable and accurate tool for frailty screening in SSU, with a similar performance to that already demonstrated in other settings. FI-VIG correlates frailty status with mortality, and our study shows that this correlation is also valid for an SSU setting. Moreover, the performance mean time was 7 minutes, which confirms that it is a feasible and easy-to-use scale in this setting.

It is well known that frailty status leads to progressively higher mortalities during hospital admission, as well as at 30 days, 6 months, and 1 year after discharge. Although the patients admitted to the SSU showed different characteristics compared with the population in which the FI-VIG was initially validated, the results of this study demonstrate that the FI-VIG is also applicable in an SSU ED setting. Although the ROC curve results are slightly lower than those obtained in the pivotal study, in this patient cohort, FI-VIG value is accurate for predicting 12-month mortality.

In our study, the mean cohort age was 83 years old, and almost 40% of the patients had some degree of disability and 16.5% had dementia. As in other SSUs in our country, the population is selected a priori by the criteria that determine the decision of admission to this unit, and the demographic characteristics of our cohort are similar to those reported in the recent literature. [

34] Through FI-VIG application, we were able to determine that 57.6% of the patients in our SSU had some degree of frailty, given that most classified as mild (63.8%) or moderately (29.9%) frail. These data are relevant since we have not found similar studies describing frailty features in an SSU. Despite being a previously selected population with an expected short hospital stay, our study revealed that in our SSU, there was a large group of frail individuals in whom FI-VIG performance could offer a great opportunity for tailored interventions.

Systematically measuring frailty is undoubtfully useful in patient management, [

28] and in the SSU, FI-VIG turned out to be an accurate tool that should be incorporated in clinical practice. FI-VIG assigns to each patient a numerical score, allowing its categorization into different frailty degrees, which, in turn, correlate well with mortality. In addition, as it is a multidimensional scale, it is able to detect several deficits in frail patients that could be used as the base of a reglementary Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) in a second step. [

11,

26] This would allow prompt patient referral to expert teams in order to initiate interventions focused on reversing or preventing secondary risks. By doing this, it improves the prevention of incidental geriatric syndromes during admission in frail individuals, as a specific care plan can be designed early (i.e., early mobilization, identification and correct management of delirium, prevention of constipation and falls, careful pain management, avoidance of medication-related risks, and initiation of pharmaceutical care programs, among others). Finally, by frailty stratification, FI-VIG offers the chance for tailored interventions and therapeutic intensity for these patients. [32-34]

Our study has some notable limitations. It is a single-center study, and contains a low number of patients with advanced frailty, probably due to the narrow admission criteria in an SSU. No descriptive analysis of associated diseases, discharge destination, or length of stay were performed. Frailty assessment with FI-VIG includes several dimensions, including chronic and oncologic diseases, and, thus, these diseases that can impact on mortality are included in the frailty assessment itself. Our study is limited to frailty and mortality evaluation, and the absence of any analysis of the length of stay or the discharge destination is an obvious limitation. However, the study does have several strengths: it was designed as a prospective study, we recruited a large number of patients, and, lastly, frailty assessment was performed by a small and highly-trained research team.

Given the growing importance of frailty as an expanding public health problem, interventions such as FI-VIG application, in order to deliver an integrated care procedure to older people across different settings, could make acute and community care more responsive for all patients.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, there is a strong correlation between the frailty degree measured with FI-VIG and mortality at 1, 6, and 12 months. FI-VIG is a valid tool for systematic frailty identification in an ED SSU. It is a feasible and easy-to-use scale in this setting, and its routine implementation in the SSU could enable early risk stratification to detect vulnerable patients with specific needs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Mireia Puig and Josep Ris; methodology, Miguel Rizzi and Josep Anton Montiel.; software, Miguel Rizzi and José Alberto Santos.; validation, Marta Blázquez, Josep Anton Montiel, Leopoldo Higa and Gastón Fernández; formal analysis, José Alberto Santos and Miguel Rizzi.; investigation, Marta Blázquez, Josep Anton Montiel, Belén Acosta, Elena Gonzalez, Rosario Fraile, David Figueroa, Iván Agra y Sergio Herrera; data curation, José Alberto Santos, Miguel Rizzi.; writing—original draft preparation, Marta Blázquez, Mireia Puig.; writing—review and editing, all; supervision, Josep Anton Montiel, Josep Ris, Mireia Puig.; project administration, Josep Anton Montiel.; funding acquisition, Josep Anton Montiel. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hestia Chair in Integrated Social and Health Care, 2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the IIB Sant Pau, code IIBSP-FRA-2020-74.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was obtained in all cases, as requested by the Ethics Committee.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jordi Amblàs Novellas for his review of this manuscript. Dr. Amblàs is Associate Professor at UVic-UCCC, Director of Strategy at l'Agència d'Integració Social i Sanitària (Departament de Salut) and Head of the Central Catalonia Chronicity Research Group (C3RG) & Centre for Health and Social Care Research (CESS).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations Population Division. The World at Six Billion. United Nations Publ, 1–63.

- WHO. Health and Ageing. 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health.

- Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013, 381, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Prevalence and 10-Year outcomes of frailty in older adults in relation to deficit accumulation. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010, 58(4), 681–687. [CrossRef]

- Theou O, Campbell S, Malone ML, Rockwood K. Older Adults in the Emergency Department with Frailty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018, 34(3), 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, Lumpkin J SJ. Caring for High-Need, High-Cost Patients. N Engl J Med 2016, 375(10), 909–911. [CrossRef]

- Brousseau AA, Dent E, Hubbard R, et al. Identification of older adults with frailty in the Emergency Department using a frailty index: Results from a multinational study. Age Ageing. 2018, 47, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji L, Michal Jazwinski S, Kim S. Frailty and biological age. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2021, 25(3), 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner G, Clegg A. Best practice guidelines for the management of frailty: a British Geriatrics Society, Age UK and Royal College of General Practitioners report. Age Ageing 2014, 43(6), 744–747. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boreskie KF, Hay JL, Boreskie PE, Arora RC, Duhamel TA. Frailty-aware care: giving value to frailty assessment across different healthcare settings. BMC Geriatr 2022, 22(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Amblàs-Novellas J, Martori JC, Espaulella J, et al. Frail-VIG index: A concise frailty evaluation tool for rapid geriatric assessment. BMC Geriatr 2018, 18(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Simon NR, Jauslin AS, Bingisser R, Nickel CH. Emergency presentations of older patients living with frailty: Presenting symptoms compared with non-frail patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2022, 59, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djärv T, Castrén M, Martenson L, Kurland L. Decreased general condition in the emergency department: High in-hospital mortality and a broad range of discharge diagnoses. Eur J Emerg Med 2015, 22(4), 241–246. [CrossRef]

- Fehlmann CA, Nickel CH, Cino E, Al-Najjar Z, Langlois N, Eagles D. Frailty assessment in emergency medicine using the Clinical Frailty Scale: a scoping review. Intern Emerg Med. 2022, 17, 2407–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucke JA, Mooijaart SP, Heeren P, et al. Providing care for older adults in the Emergency Department: expert clinical recommendations from the European Task Force on Geriatric Emergency Medicine. Eur Geriatr Med 2022, 13(2), 309–317. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott A, Taub N, Banerjee J, et al. Does the Clinical Frailty Scale at Triage Predict Outcomes From Emergency Care for Older People? Ann Emerg Med. 2021, 77(6), 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeppeli T, Rueegg M, Dreher-Hummel T, et al. Validation of the Clinical Frailty Scale for Prediction of Thirty-Day Mortality in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med 2020, 76(3), 291–300. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Caoimh R, Kenelly S, Ahern E, S O’Keefe, RR O. Facing Covid-19 in Italy — Ethics, Logistics, and Therapeutics on the Epidemic’s Front Line. J Frailty Aging 2020, 9(3), 185–186. [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen R, Brabrand M. Screening of the frail patient in the emergency department: A systematic review. Eur J Intern Med. 2017, 45, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott A, Phelps K, Regen E, Conroy SP. Identifying frailty in the Emergency Department-feasibility study. Age Ageing 2017, 46(5), 840–845. [CrossRef]

- Lewis ET, Dent E, Alkhouri H, et al. Which frailty scale for patients admitted via Emergency Department? A cohort study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019, 80, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Caoimh R, Costello M, Small C, et al. Comparison of frailty screening instruments in the emergency department. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019, 16(19), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosco TD, Best J, Davis D, et al. What is the relationship between validated frailty scores and mortality for adults with COVID-19 in acute hospital care? A systematic review. Age Ageing. 2021, 50(3), 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig-Campmany M, Blázquez-Andion M, Ris-Romeu J. Aprender, desaprender y reaprender para asistir ancianos en urgencias : el secreto del cambio. Emergencias. 2020, 32, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alonso G, Escudero JM. La unidad de corta estancia de urgencias y la hospitalización a domicilio como alternativas a la hospitalización convencional. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2010, 33, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Marcos C, Jacob J, Llorens P, et al. Analysis of the effectiveness and safety of short-stay units in the hospitalization of patients with acute heart failure. Propensity Score SSU-EAHFE. Rev Clin Esp 2022, 222(8), 443–457. [CrossRef]

- González Armengol JJ, Fernández Alonso C, Martín Sánchez FJ, et al. Actividad de una unidad de corta estancia en urgencias de un hospital terciario: cuatro años de experiencia. Emergencias 2009, 21(2), 87–94.

- Amblàs Novellas J, Torné A, Oller R, Martori JC, Espaulella J, Romero Ortuno R. Transitions between degrees of multidimensional frailty among older people admitted to intermediate care : a multicentre prospective study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amblàs-Novellas J, Martori JC, Molist Brunet N, Oller R, Gómez-Batiste X, Espaulella Panicot J. Índice frágil-VIG: diseño y evaluación de un índice de fragilidad basado en la Valoración Integral Geriátrica. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 2017, 52(3), 119–127. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Batiste X, Martínez M, Blay C. Identifying patients with chronic conditions in need of palliative care in the general population: Development of the NECPAL tool and preliminary prevalence rates in Catalonia. BMJ Supportive and Palliative Care 2013, 3(3), 300–308. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney DI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J 1965, 14, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam CS, Hoogendijk EO, Mooijaart SP, et al. A narrative review of frailty assessment in older patients at the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2021, 28(4), 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juanes A, Garin N, Mangues MA, et al. Impact of a pharmaceutical care programme for patients with chronic disease initiated at the emergency department on drug-related negative outcomes: A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2018, 25(5), 274–280. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amblàs-Novellas J, Murray SA, Espaulella J, et al. Identifying patients with advanced chronic conditions for a progressive palliative care approach: a cross- sectional study of prognostic indicators related to end-of-life trajectories. BMJ 2016, 19(6), e012340. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).