Submitted:

09 May 2023

Posted:

10 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

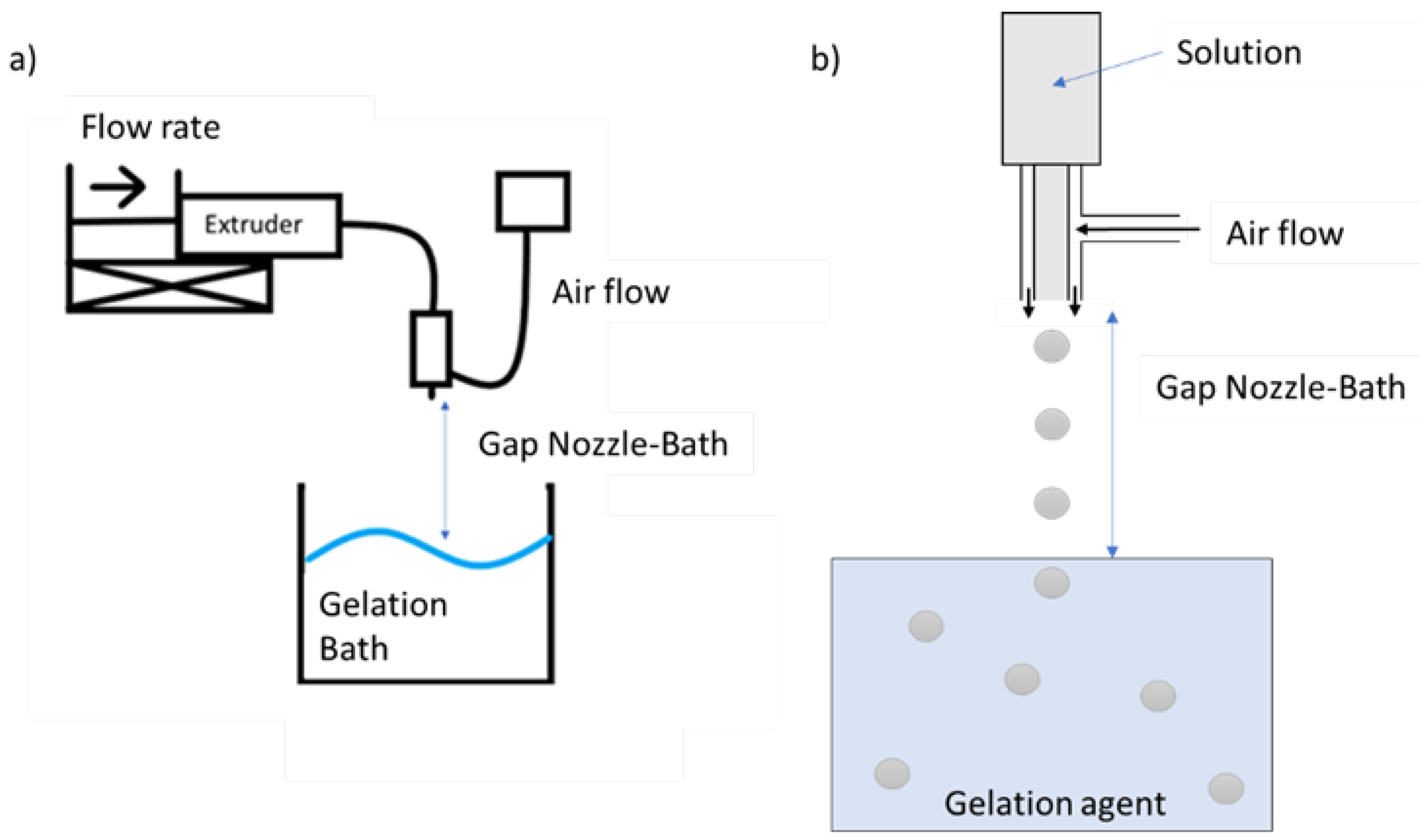

2.2. Production and Optimization of Particles using DoE

2.3. Morphological Characterization

2.4. Swelling

2.5. In Vitro Degradation

2.6. Encapsulation Efficiency and Loading Capacity

2.7. In Vitro Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.8. In Vitro Drug Release

3. Results

3.1. Production and Optimization of Particles

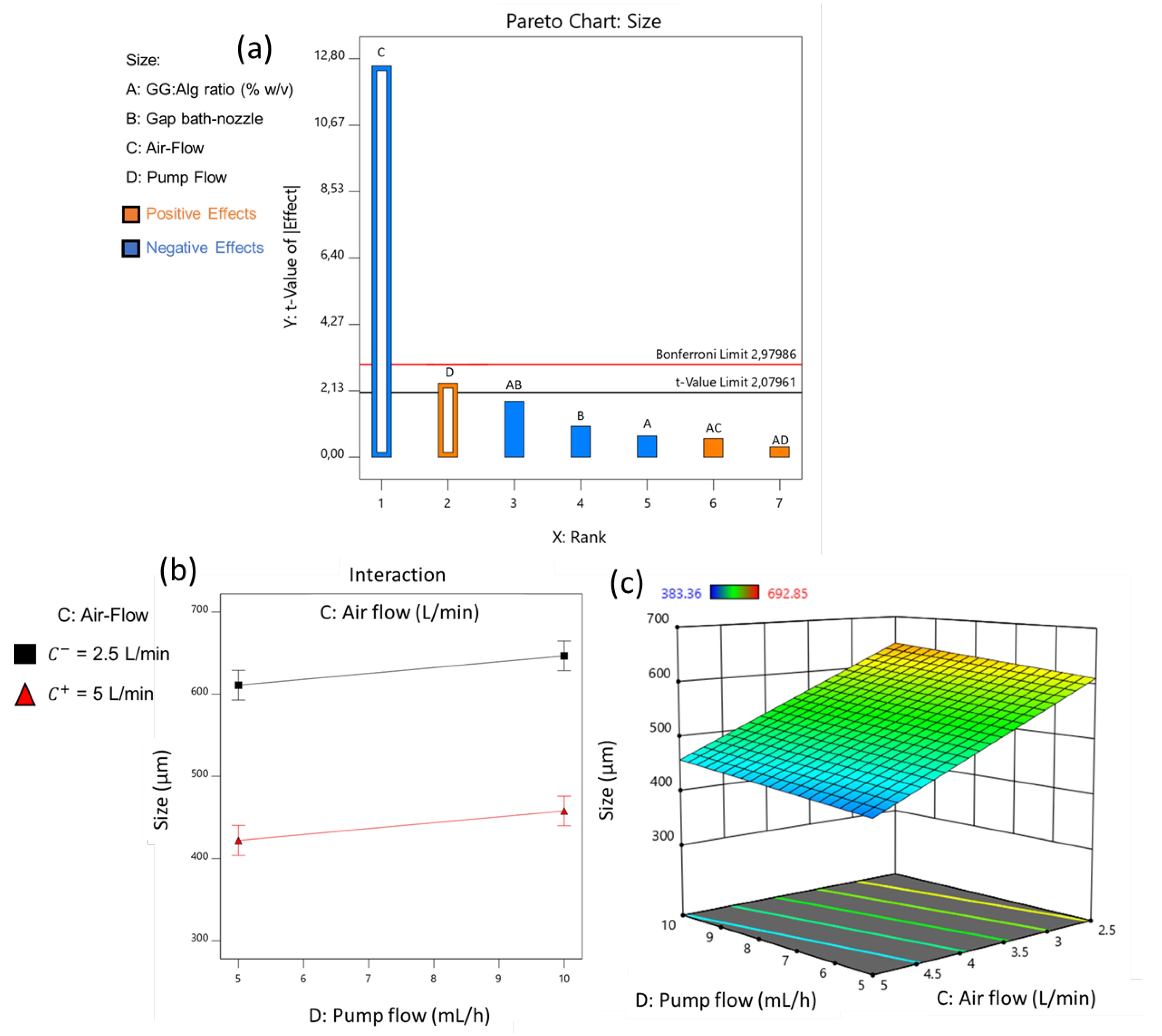

3.1.1. Microparticle’s Size

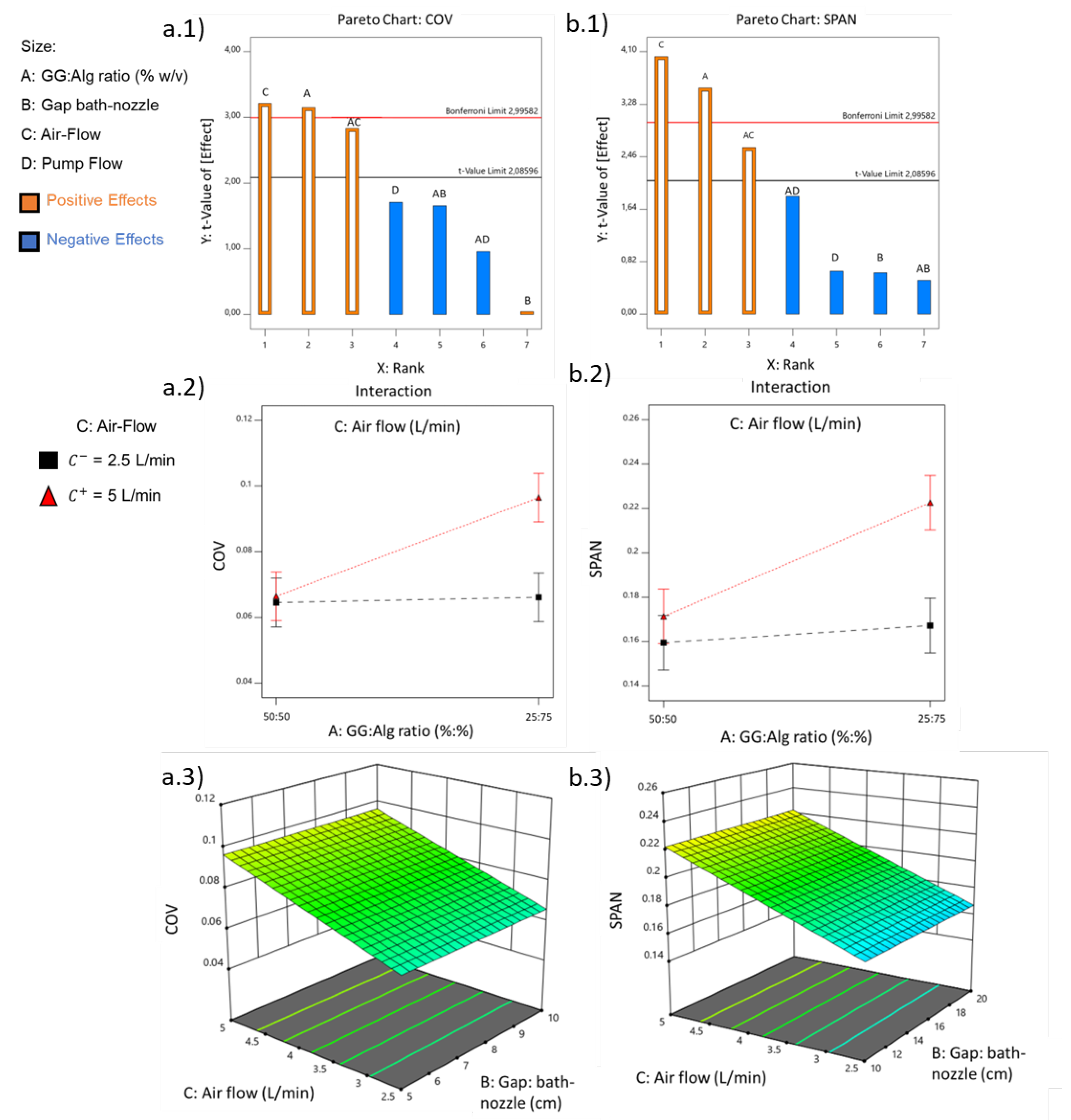

3.1.2. Dispersibility: COV and SPAN

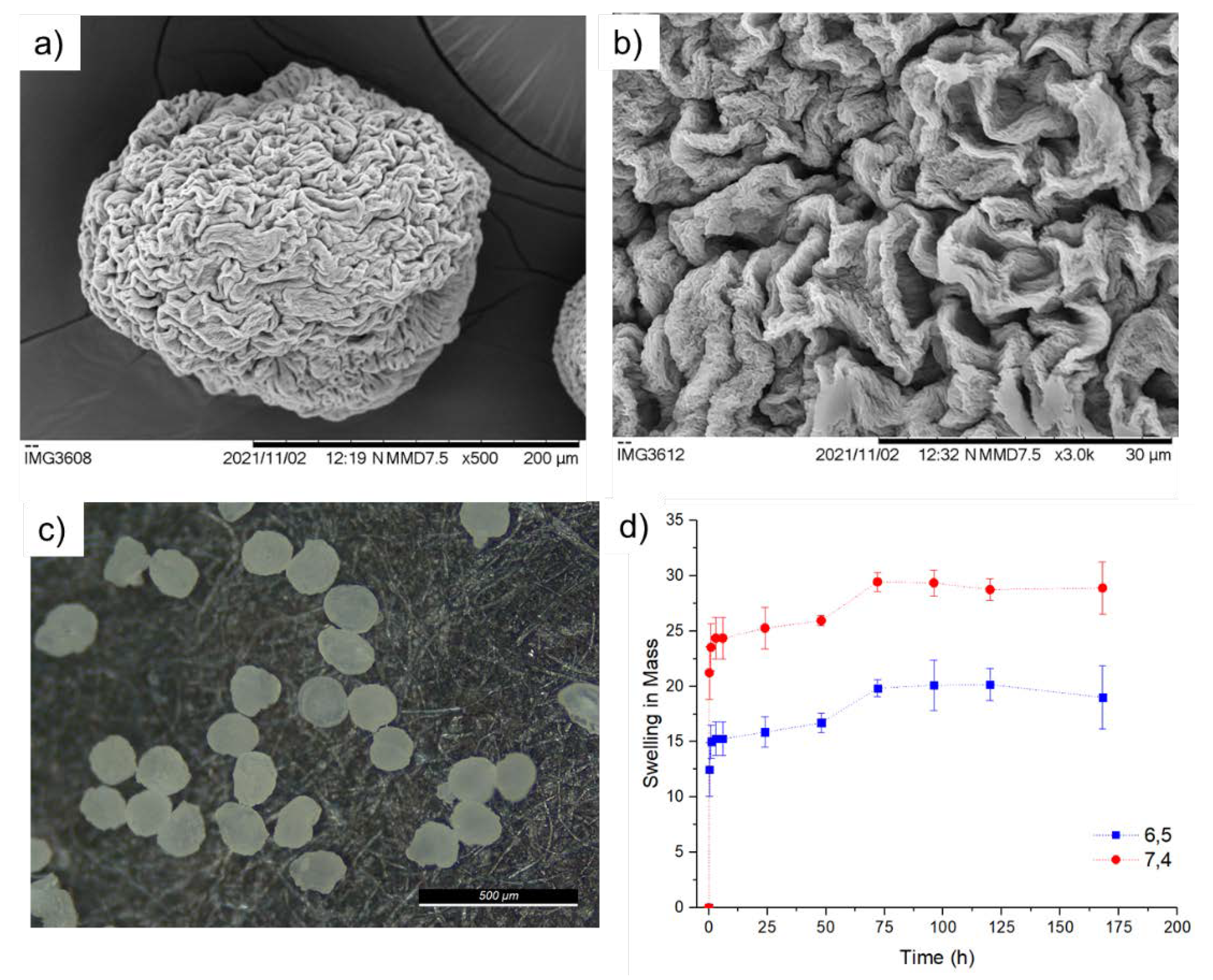

3.2. Drying and Swelling of the Microparticles

3.3. Encapsulation Efficiency and Loading Capacity

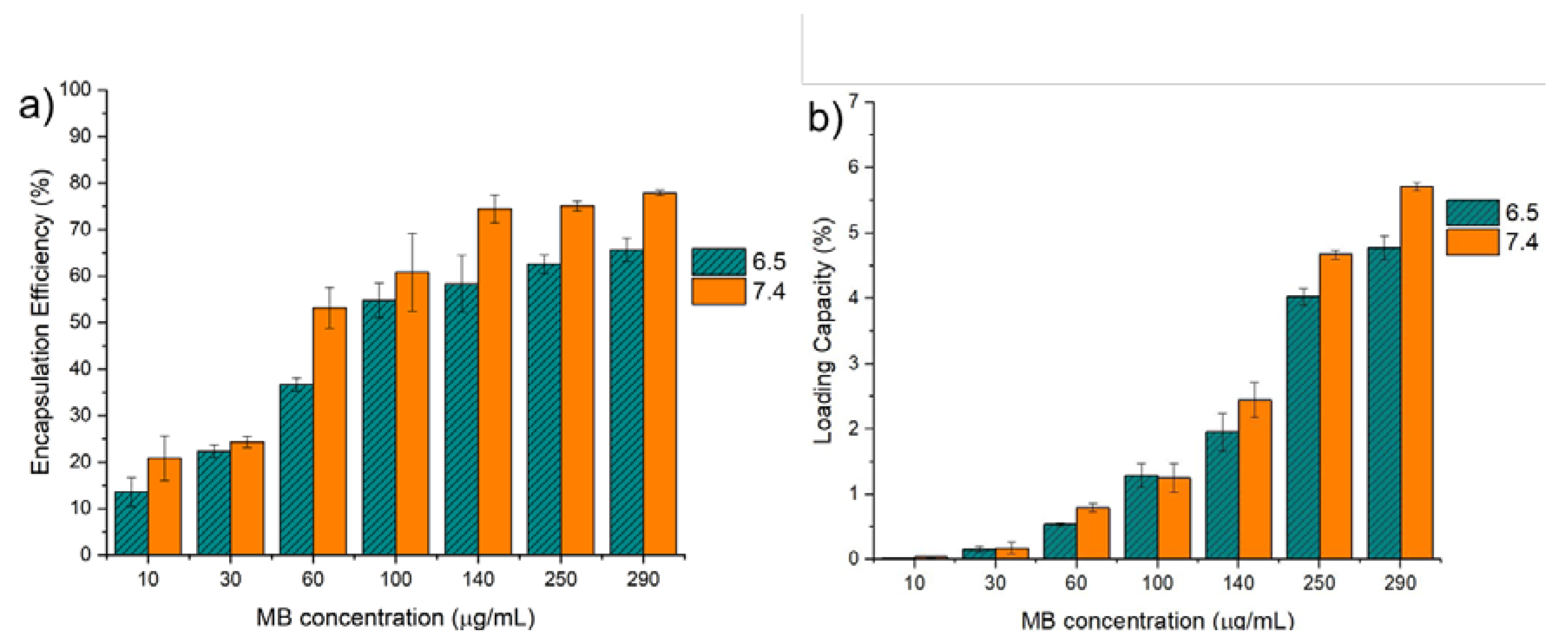

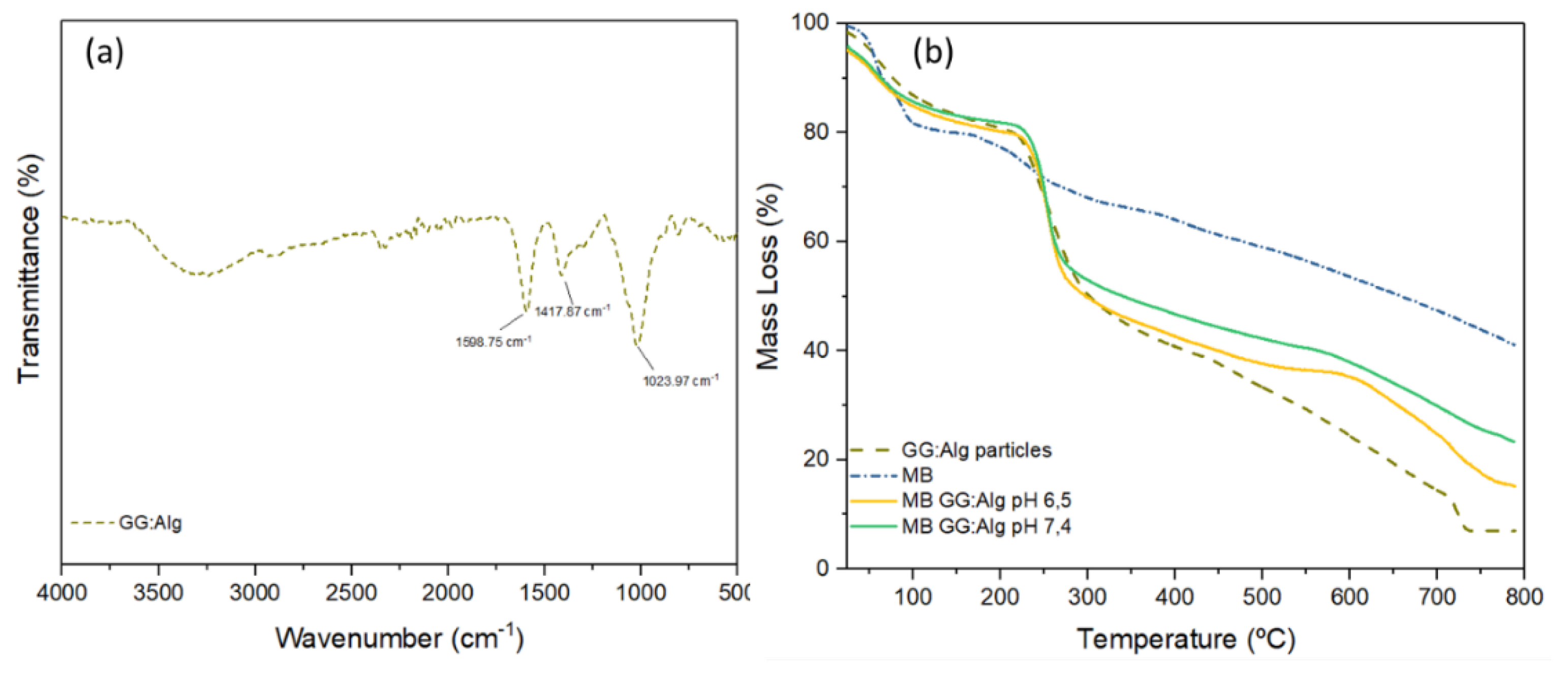

3.4. FTIR and TGA

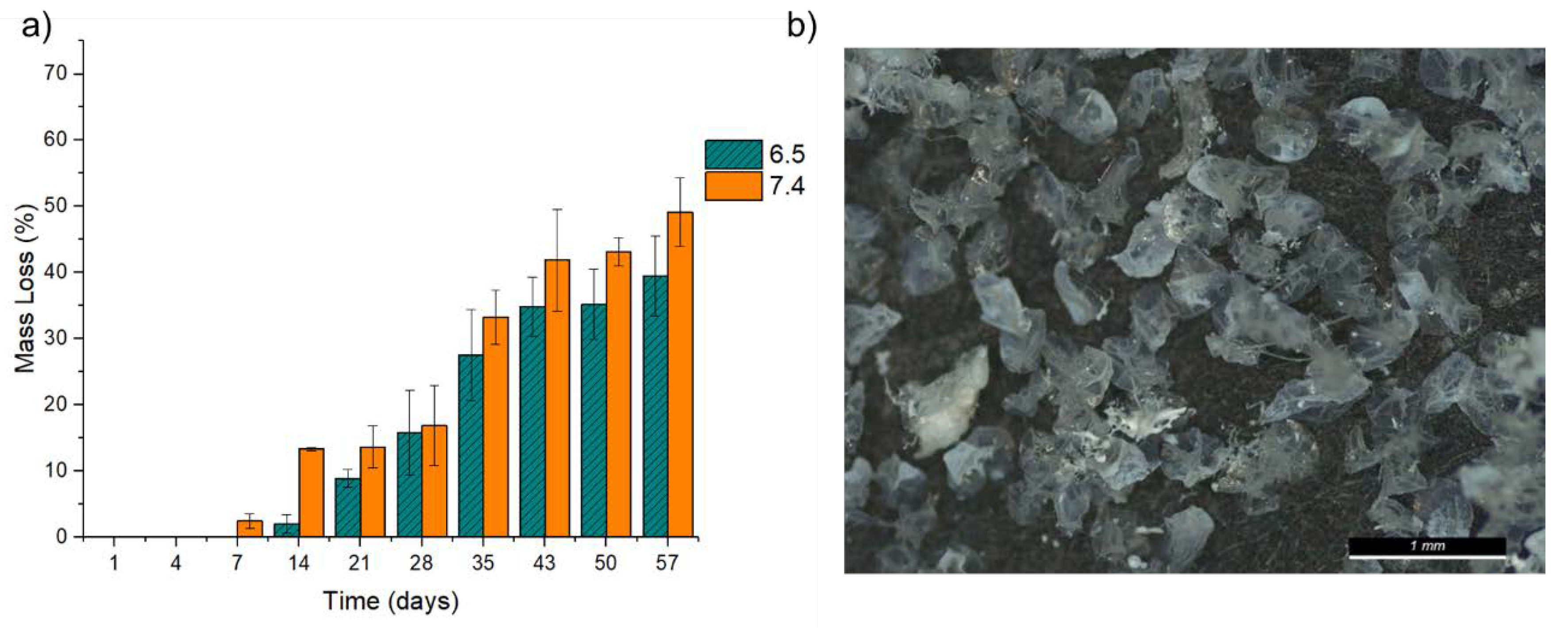

3.5. Degradation

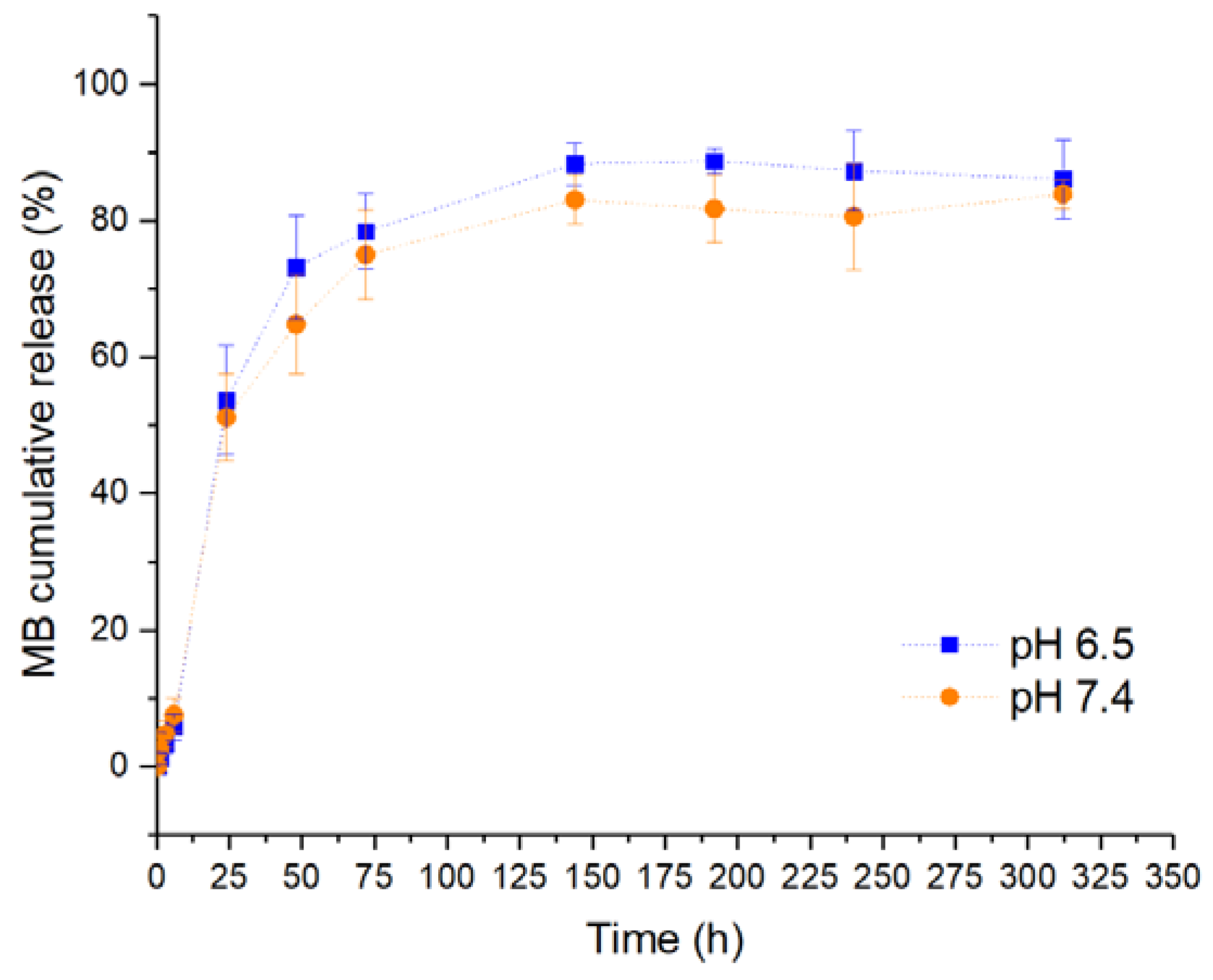

3.6. In Vitro Drug Release and Mathematical Model Fitting

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iordache, T.V.; Banu, N.D.; Giol, E.D.; et al. Factorial design optimization of polystyrene microspheres obtained by aqueous dispersion polymerization in the presence of poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) reactive stabilizer. Polym Int 2020, 69, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarta, E.; Sonvico, F.; Bettini, R.; et al. Inhalable microparticles embedding calcium phosphate nanoparticles for heart targeting: The formulation experimental design. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, I.; Abu Haija, M.; Kannan, P.; Banat, F. Adsorptive Removal of Methylene Blue from Water Using High-Performance Alginate-Based Beads. Water Air Soil Pollut 2020, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, S.; Das, A.; Nayak, A.K.; et al. Aceclofenac-loaded unsaturated esterified alginate/gellan gum microspheres: In vitro and in vivo assessment. Int J Biol Macromol 2013, 57, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halim, N.F.A.; Majid, S.R.; Arof, A.K.; et al. Gellan Gum-LiI gel polymer electrolytes. Mol Cryst Liq Cryst 2012, 554, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khampieng, T.; Aramwit, P.; Supaphol, P. Silk sericin loaded alginate nanoparticles: Preparation and anti-inflammatory efficacy. Int J Biol Macromol 2015, 80, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, I.S.M.; Majid, S.R.; Arof, A.K.; et al. Characteristics of gellan gum-LiCF3SO3polymer electrolytes. Solid State Ionics 2012, 225, 649–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Lalwani, D.; Gollmer, S.; et al. Development and evaluation of a calcium alginate based oral ceftriaxone sodium formulation. Prog Biomater 2016, 5, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrêlo, H.; Soares, P.I.P.; Borges, J.P.; Cidade, M.T. Injectable composite systems based on microparticles in hydrogels for bioactive cargo controlled delivery. Gels 2021, 7, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzler, M.; Vermeeren, S.; Kolevatov, R.O.; et al. Evaluating Release Kinetics from Alginate Beads Coated with Polyelectrolyte Layers for Sustained Drug Delivery. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2021, 4, 6719–6731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boni, F.I.; Prezotti, F.G.; Cury, B.S.F. Gellan gum microspheres crosslinked with trivalent ion: Effect of polymer and crosslinker concentrations on drug release and mucoadhesive properties. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 2016, 42, 1283–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Shi, M.; liu, Y.; et al. A Novel In Situ Gel Formulation of Ranitidine for Oral Sustained Delivery. Biomol Ther 2014, 22, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredenberg, S.; Wahlgren, M.; Reslow, M.; Axelsson, A. The mechanisms of drug release in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-based drug delivery systems—A review. Int J Pharm 2011, 415, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prezotti, F.G.; Cury, B.S.F.; Evangelista, R.C. Mucoadhesive beads of gellan gum/pectin intended to controlled delivery of drugs. Carbohydr Polym 2014, 113, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruschi, M.L. Strategies to Modify the Drug Release from Pharmaceutical Systems Related titles. Elsevier: Cambridge, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.; Lobo, J.M.S. Modeling and comparision of dissolution profiles. Eur J Pharm Sci 2001, 13, 123–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Fassihi, R. Application of binary polymer system in drug release rate modulation. 2. Influence of formulation variables and hydrodynamic conditions on release kinetics. J Pharm Sci 1997, 86, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Gao, Y.; Bou-Chacra, N.; Löbenberg, R. Evaluation of the DDSolver software applications. Biomed Res Int 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huo, M.; Zhou, J.; et al. DDSolver: An add-in program for modeling and comparison of drug dissolution profiles. AAPS J 2010, 12, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, D.Y.; Lee, L.Y.; Wang, C.H. Mathematical modeling and simulation of drug release from microspheres: Implications to drug delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2006, 58, 1274–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppas, N.A.; Sahlin, J.J. A simple equation for the description of solute release. III. Coupling of diffusion and relaxation. Int J Pharm 1989, 57, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.; Lim, T.K.; Ravindra, P.; et al. The effect of low air-to-liquid mass flow rate ratios on the size, size distribution and shape of calcium alginate particles produced using the atomization method. J Food Eng 2012, 108, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workamp, M.; Alaie, S.; Dijksman, J.A. Coaxial air flow device for the production of millimeter-sized spherical hydrogel particles. Rev Sci Instrum 2016, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastruzzi, A.; Pitingolo, G.; Luca, G.; Nastruzzi, C. DoE analysis of approaches for hydrogel microbeads’ preparation by millifluidic methods. Micromachines 2020, 11, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Yahya, R.; Hassan, A.; et al. pH Sensitive Hydrogels in Drug Delivery: Brief History, Properties, Swelling, and Release Mechanism, Material Selection and Applications. 2020, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeb, B.; Saberi, A.H.; Weiss, J.; McClements, D.J. Retention and release of oil-in-water emulsions from filled hydrogel beads composed of calcium alginate: Impact of emulsifier type and pH. Soft Matter 2015, 11, 2228–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayment, P.; Wright, P.; Hoad, C.; et al. Investigation of alginate beads for gastro-intestinal functionality, Part 1: In vitro characterisation. Food Hydrocoll 2009, 23, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narkar, M.; Sher, P.; Pawar, A. Stomach-specific controlled release gellan beads of acid-soluble drug prepared by ionotropic gelation method. AAPS PharmSciTech 2010, 11, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temeepresertkij, P.; Iwaoka, M.; Iwamori, S. Molecular interactions between methylene blue and sodium alginate studied by molecular orbital calculations. Molecules 2021, 26, 7029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.T.; Islam, M.A.; Mahmud, S.; Rukanuzzaman, M. Adsorptive removal of methylene blue by tea waste. J Hazard Mater 2009, 164, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmalek, T.; Froelich, A.; Milanowski, B.; et al. pH-Dependent Behavior of Novel Gellan Beads Loaded with Naproxen. Curr Drug Deliv 2017, 15, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, V.; Caputo, T.; Altobelli, R.; Ambrosio, L. Degradation properties and metabolic activity of alginate and chitosan polyelectrolytes for drug delivery and tissue engineering applications. AIMS Mater Sci 2015, 2, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.N.; Edgar, K.J. Alginate derivatization: A review of chemistry, properties and applications. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 3279–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augst, A.D.; Kong, H.J.; Mooney, D.J. Alginate hydrogels as biomaterials. Macromol Biosci 2006, 6, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, Z. A pH-sensitive microemulsion-filled gellan gum hydrogel encapsulated apigenin: Characterization and in vitro release kinetics. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2019, 178, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picone, C.S.F.; Cunha, R.L. Influence of pH on formation and properties of gellan gels. Carbohydr Polym 2011, 84, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Xu, H.; Sun, J.; et al. Dual delivery of BMP-2 and bFGF from a new nano-composite scaffold, loaded with vascular stents for large-size mandibular defect regeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2013, 14, 12714–12728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranci, K.; Uzun, M.; Su, S.; et al. 3D Propolis-Sodium Alginate Scaffolds: Influence on Structural Parameters, Release Mechanisms, Cell Cytotoxicity and Antibacterial Activity. Molecules 2020, 25, 5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, Z.; Jiang, S.; Bratlie, K.M. Chemically Modified Gellan Gum Hydrogels with Tunable Properties for Use as Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 6998–7007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, J.S.; Oliveira, J.M.; Caridade, S.G.; et al. Gellan gum-based hydrogels for intervertebral disc tissue-engineering applications. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2011, 5, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, A.A.; Rita, A.; Duarte, A.R.C.; et al. Bioresorbable ureteral stents from natural origin polymers. J Biomed Mater Res - Part B Appl Biomater 2015, 103, 608–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Farias, A.L.; Meneguin, A.B.; da Silva Barud, H.; Brighenti, F.L. The role of sodium alginate and gellan gum in the design of new drug delivery systems intended for antibiofilm activity of morin. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 162, 1944–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, J.; Bolla, S.; Barr, J.; et al. Alginate microparticles prepared by spray-coagulation method: Preparation, drug loading and release characterization. Int J Pharm 2005, 303, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voo, W.P.; Ooi, C.W.; Islam, A.; et al. Calcium alginate hydrogel beads with high stiffness and extended dissolution behaviour. Eur Polym J 2016, 75, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanka, M.; Shetty, C.; Srivastava, R. Methotrexate loaded gellan gum microparticles for drug delivery. Int J ofBiological Macromol 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebru, F.; Tuba, K.; Altıncekic, G. Investigation of gelatin/chitosan as potential biodegradable polymer films on swelling behavior and methylene blue release kinetics. Polym Bull 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RUN | FACTORS | RESPONSES | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: GG:Alg ratio(%) | B: Gap bath-nozzle (cm) | C: Air flow (L/min) | D: Pump flow (mL/h) | Size (µm) | COV | SPAN | |

| 1 | 25:75 | 20 | 5 | 10 | 383.4 | 0.0770 | 0.1969 |

| 2 | 50:50 | 20 | 5 | 5 | 434.6 | 0.0662 | 0.1486 |

| 3 | 50:50 | 10 | 2.5 | 5 | 652.6 | 0.0659 | 0.1582 |

| 4 | 50:50 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 496.1 | 0.0400 | 0.1611 |

| 5 | 25:75 | 20 | 2.5 | 5 | 617.6 | 0.0648 | 0.1610 |

| 6 | 25:75 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 427.0 | 0.1200 | 0.2460 |

| 7 | 25:75 | 20 | 5 | 10 | 441.7 | 0.0949 | 0.2311 |

| 8 | 25:75 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 418.1 | 0.1109 | 0.2496 |

| 9 | 50:50 | 20 | 2.5 | 10 | 666.9 | 0.0619 | 0.1473 |

| 10 | 50:50 | 10 | 2.5 | 5 | 607.4 | 0.0618 | 0.1447 |

| 11 | 25:75 | 10 | 2.5 | 10 | 649.0 | 0.0600 | 0.1447 |

| 12 | 50:50 | 20 | 5 | 5 | 453.3 | 0.0690 | 0.1740 |

| 13 | 25:75 | 10 | 2.5 | 10 | 655.6 | 0.0718 | 0.1723 |

| 14 | 50:50 | 20 | 2.5 | 10 | 619.5 | 0.0653 | 0.1604 |

| 15 | 50:50 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 435.0 | 0.0589 | 0.1505 |

| 16 | 50:50 | 10 | 2.5 | 5 | 591.0 | 0.0587 | 0.1623 |

| 17 | 25:75 | 20 | 5 | 10 | 490.6 | 0.0853 | 0.1935 |

| 18 | 50:50 | 20 | 2.5 | 10 | 692.8 | 0.0735 | 0.1838 |

| 19 | 50:50 | 20 | 5 | 5 | 405.2 | 0.0825 | 0.1752 |

| 20 | 25:75 | 10 | 2.5 | 10 | 676.4 | 0.0586 | 0.1679 |

| 21 | 50:50 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 418.4 | 0.0820 | 0.2185 |

| 22 | 25:75 | 20 | 2.5 | 5 | 527.9 | 0.0796 | 0.1928 |

| 23 | 25:75 | 20 | 2.5 | 5 | 588.0 | 0.0619 | 0.1646 |

| 24 | 25:75 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 474.1 | 0.0907 | 0.2184 |

| pH | pH 6.5 | pH 7.4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KP | k | 20.760 | 19.675 |

| n | 0.239 | 0.238 | |

| R2adj | 0.8313 | 0.8461 | |

| KP Tlag | k | 67.111 | 50.531 |

| n | 0.044 | 0.081 | |

| Tlag | 23.994 | 14.713 | |

| R2adj | 0.9915 | 0.9819 | |

| Wbll | a | 10.989 | 8.095 |

| b | 0.591 | 0.466 | |

| R2adj | 0.9279 | 0.9201 | |

| PS | k1 | 12.637 | 11.920 |

| k2 | -0.428 | -0.405 | |

| m | 0.446 | 0.445 | |

| R2adj | 0.9228 | 0.9365 | |

| PS Tlag | k1 | 35.742 | 31.730 |

| k2 | -3.575 | -2.991 | |

| m | 0.264 | 0.273 | |

| Tlag | 5.999 | 5.994 | |

| R2adj | 0.9893 | 0.9914 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).