Submitted:

09 May 2023

Posted:

10 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

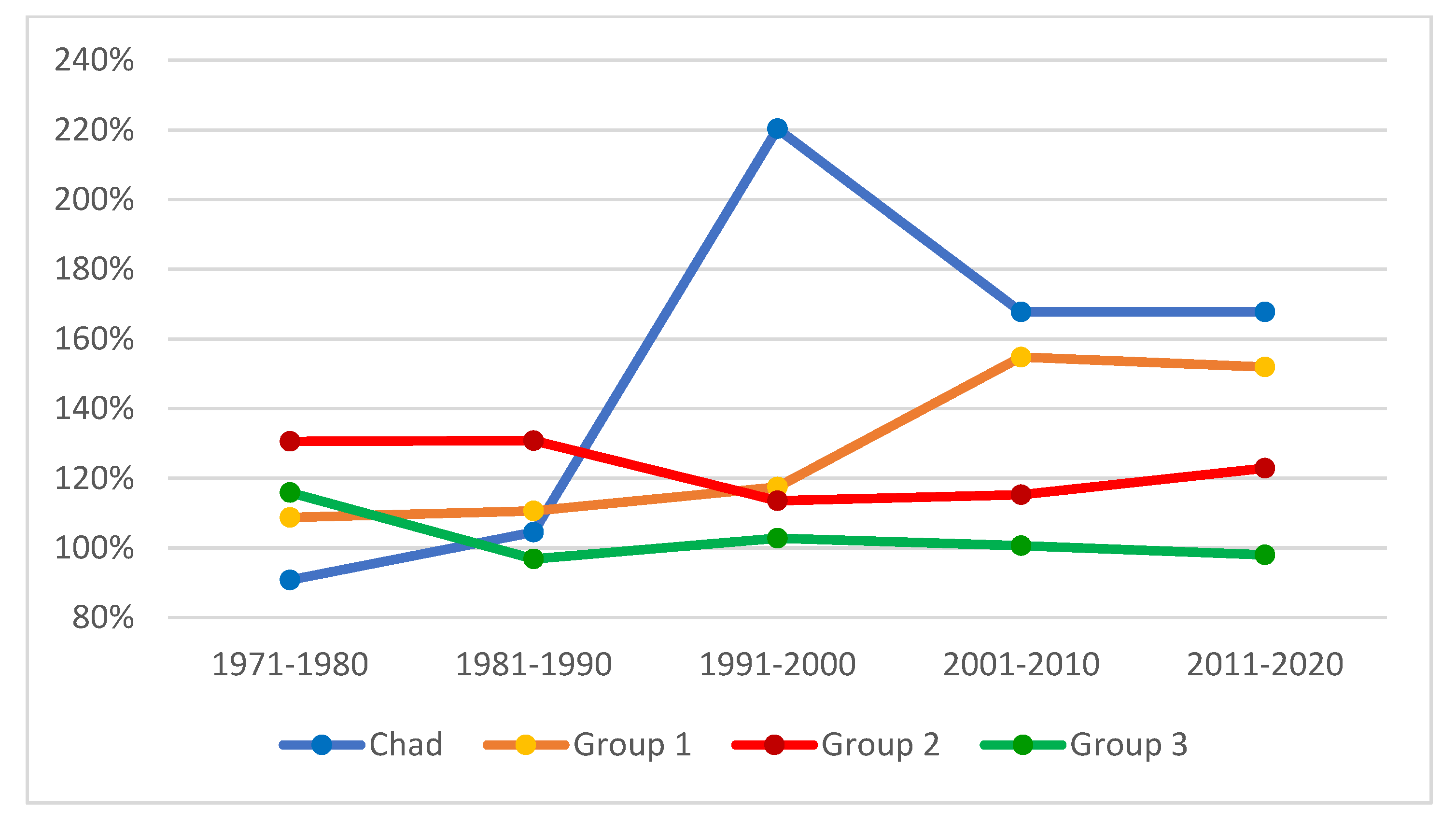

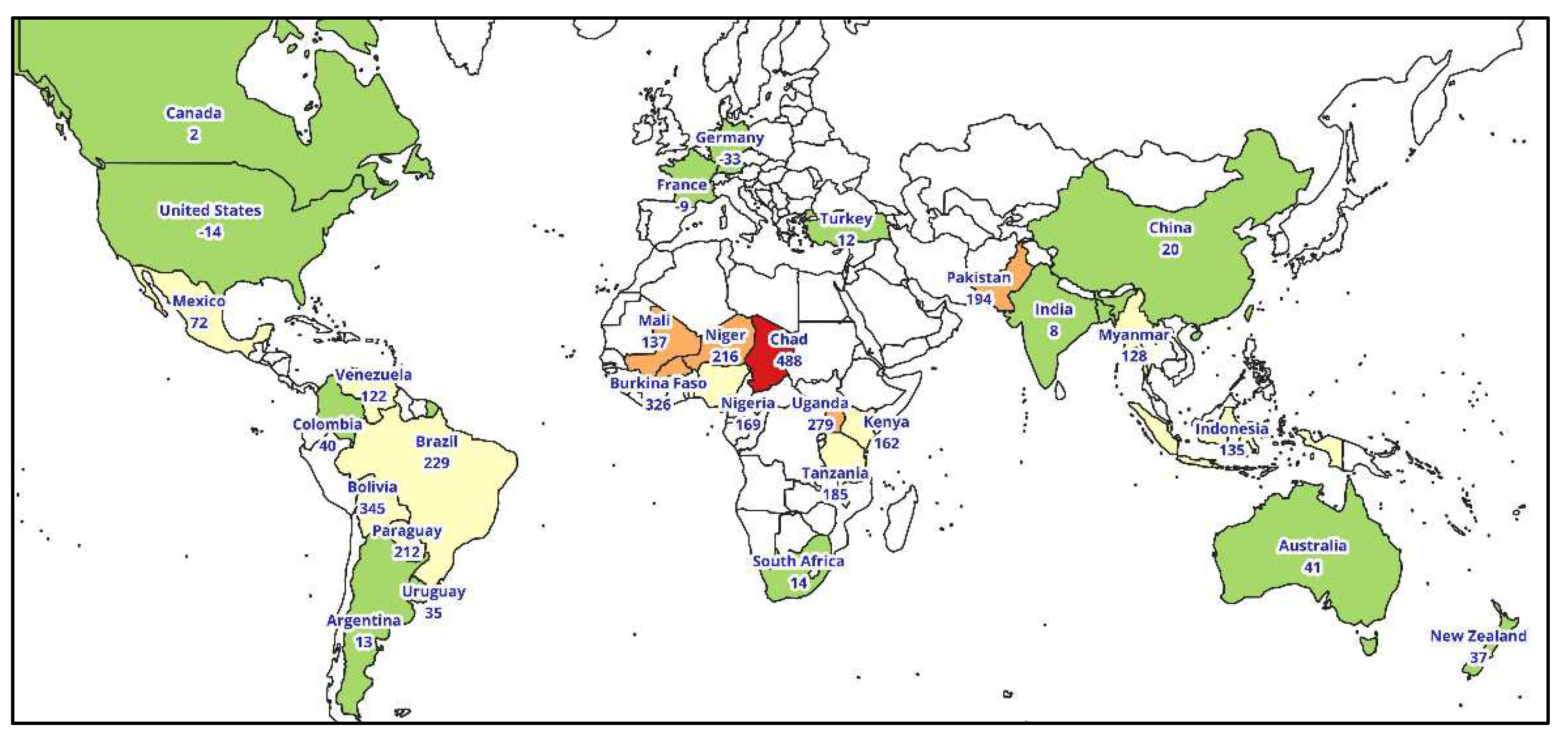

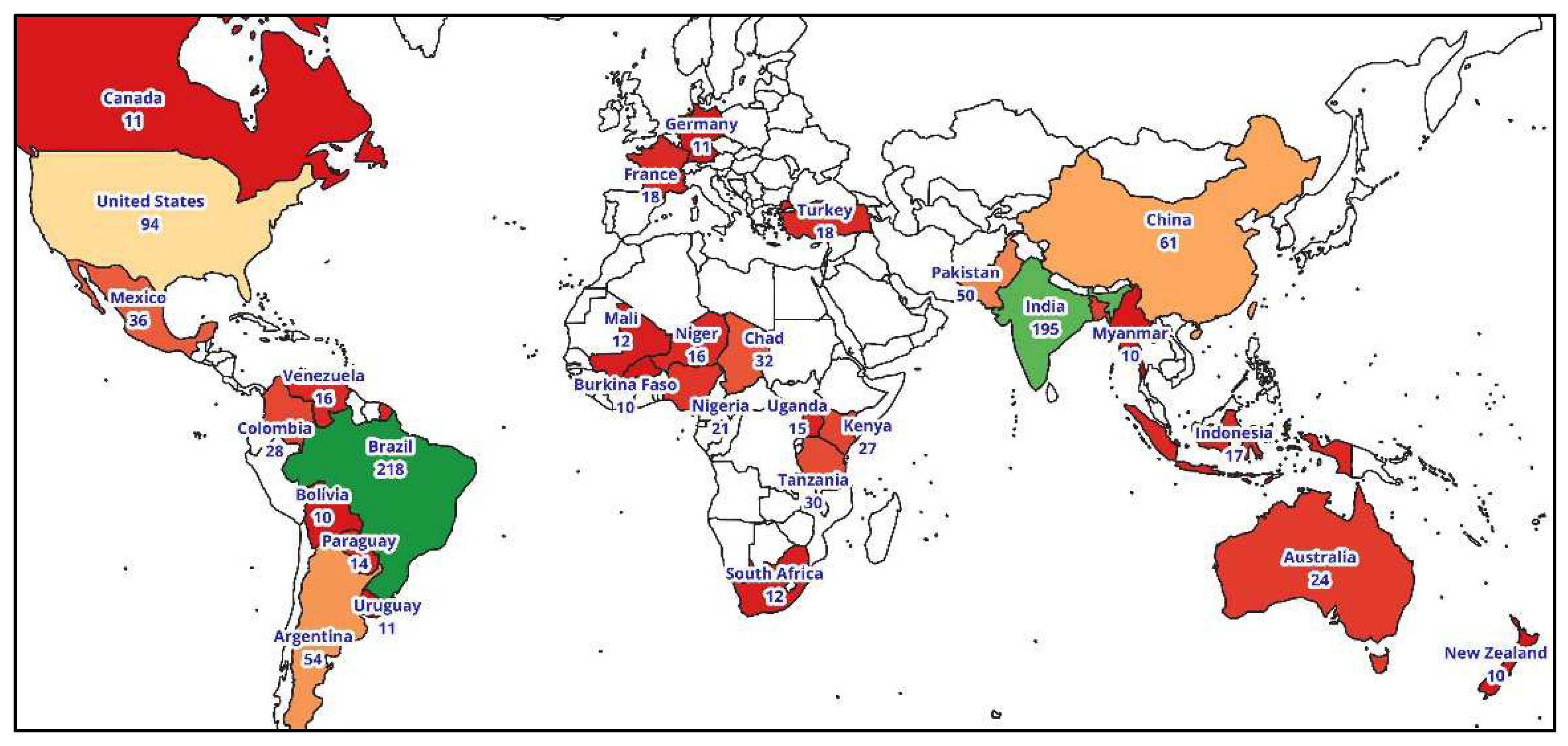

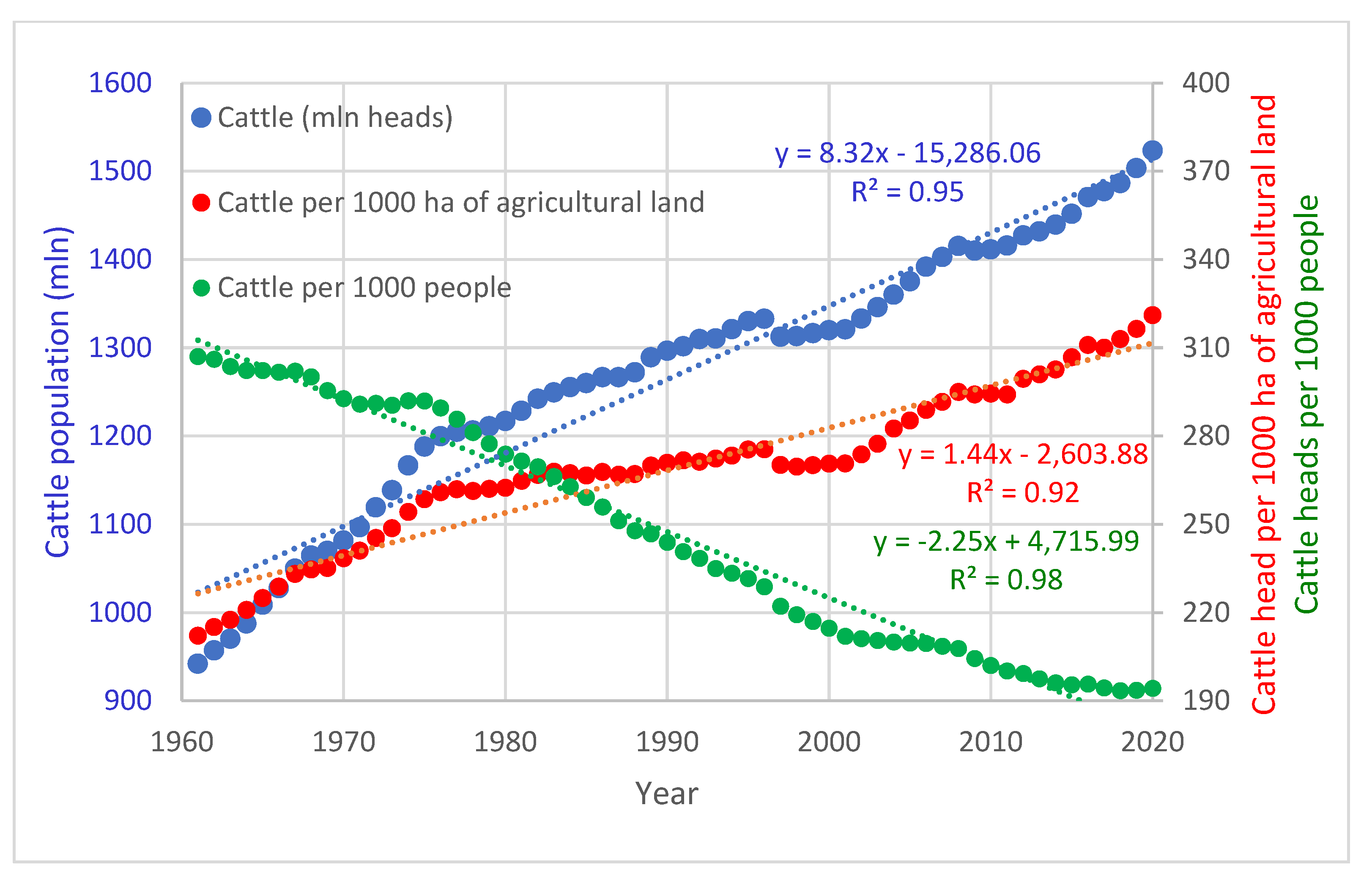

3.1. Temporal trends in cattle population in period 1961-2020

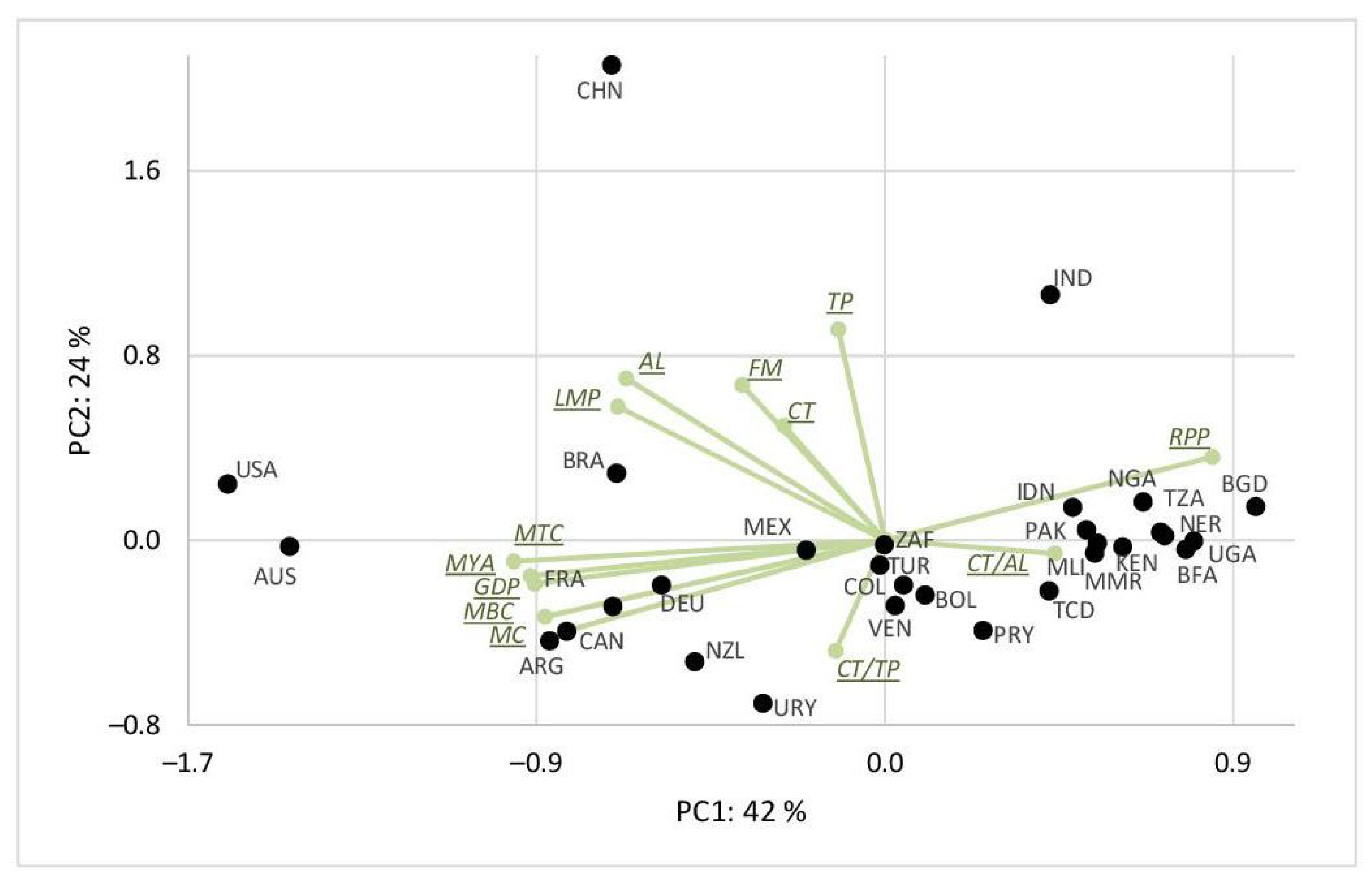

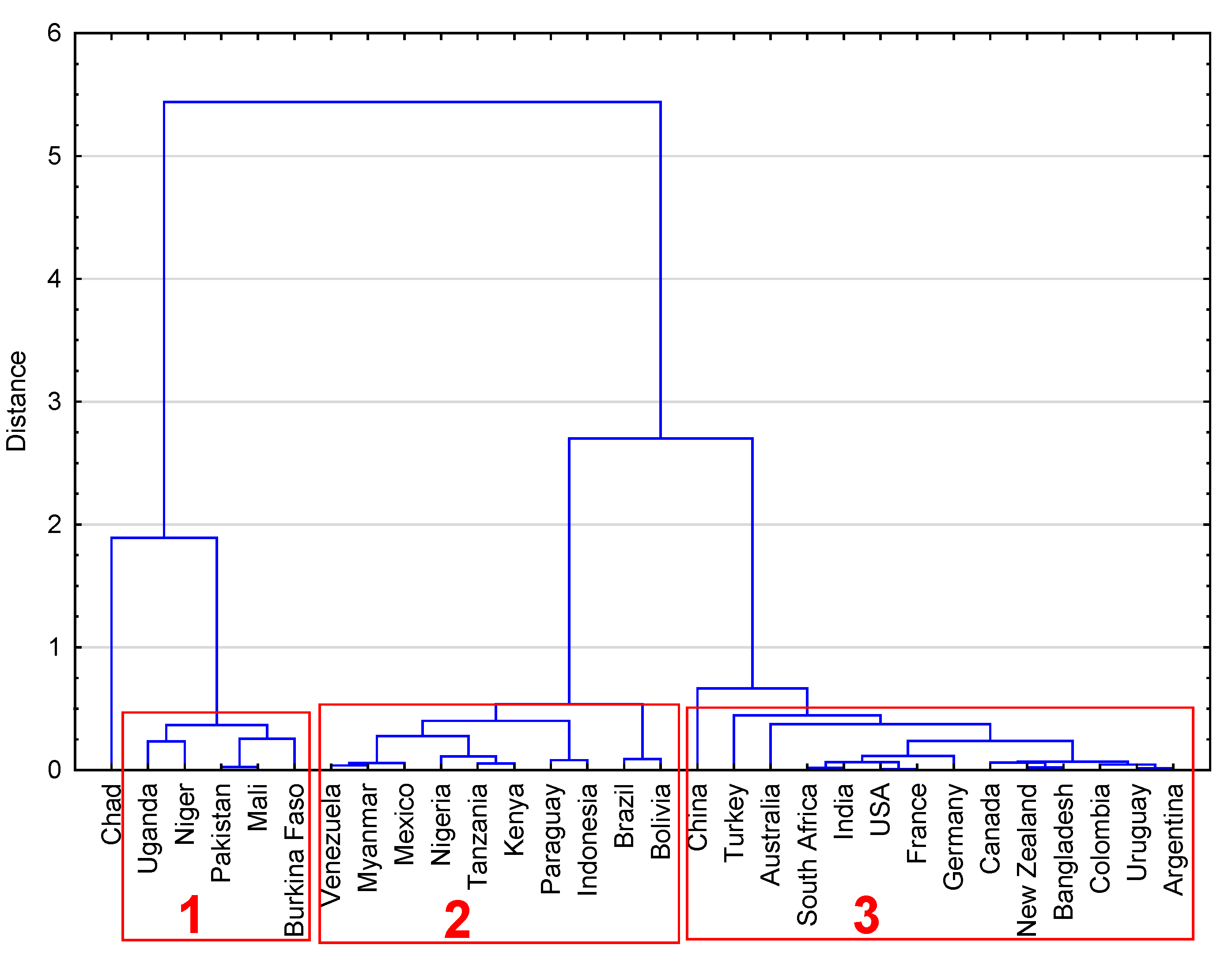

3.2. Relationship between cattle population with other variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wuebbles, D. Atmospheric Methane and Global Change. Earth-Science Reviews 2002, 57, 177–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Eggleston, H.S., Ed.; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies: Hayama, Japan, 2006; ISBN 978-4-88788-032-0. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruta, A.; Aalto, T.; Backman, L.; Hakkarainen, J.; van der Laan-Luijkx, I.T.; Krol, M.C.; Spahni, R.; Houweling, S.; Laine, M.; Dlugokencky, E.; et al. Global Methane Emission Estimates for 2000–2012 from CarbonTracker Europe-CH4 v1.0. Geoscientific Model Development 2017, 10, 1261–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gouw, J.A.; Veefkind, J.P.; Roosenbrand, E.; Dix, B.; Lin, J.C.; Landgraf, J.; Levelt, P.F. Daily Satellite Observations of Methane from Oil and Gas Production Regions in the United States. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.; Patra, P.K.; Ishijima, K.; Umezawa, T.; Ito, A.; Etheridge, D.M.; Sugawara, S.; Kawamura, K.; Miller, J.B.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; et al. Variations in Global Methane Sources and Sinks during 1910–2010. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2015, 15, 2595–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maasakkers, J.D.; Jacob, D.J.; Sulprizio, M.P.; Scarpelli, T.R.; Nesser, H.; Sheng, J.-X.; Zhang, Y.; Hersher, M.; Bloom, A.A.; Bowman, K.W.; et al. Global Distribution of Methane Emissions, Emission Trends, and OH Concentrations and Trends Inferred from an Inversion of GOSAT Satellite Data for 2010–2015. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 7859–7881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassey, K.R. Livestock Methane Emission: From the Individual Grazing Animal through National Inventories to the Global Methane Cycle. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2007, 142, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Bustamante, M.; Ahammad, H.; Clark, H.; Haberl, H.; Harper, R.; House, J.; Jafari, M.; Masera, O.; Mbow, C.; et al. 11 Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use (AFOLU).

- Gerber, P.; Opio, C. Greenhouse Gas Emmission from Ruminant Supply Chains: A Global Life Cycle Assessment; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, 2013; ISBN 978-92-5-107945-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tackling Climate Change through Livestock: A Global Assessment of Emissions and Mitigation Opportunities; Gerber, P. J., Ed.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, 2013; ISBN 978-92-5-107920-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hedenus, F.; Wirsenius, S.; Johansson, D.J.A. The Importance of Reduced Meat and Dairy Consumption for Meeting Stringent Climate Change Targets. Climatic Change 2014, 124, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollenberg, E.; Richards, M.; Smith, P.; Havlík, P.; Obersteiner, M.; Tubiello, F.N.; Herold, M.; Gerber, P.; Carter, S.; Reisinger, A.; et al. Reducing Emissions from Agriculture to Meet the 2 °C Target. Glob Change Biol 2016, 22, 3859–3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson-Delmotte, V. Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems : Summary for Policymakers; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, 2019; ISBN 978-92-9169-154-8.

- Wójcik-Gront, E. Analysis of Sources and Trends in Agricultural GHG Emissions from Annex I Countries. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J.J.; Silver, W.L. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Dairy Manure Management: A Review of Field-Based Studies. Glob Change Biol 2015, 21, 550–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.; Asrar, G.R.; West, T.O. Revised Methane Emissions Factors and Spatially Distributed Annual Carbon Fluxes for Global Livestock. Carbon Balance Manage 2017, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wójcik-Gront, E.; Gront, D. Assessing Uncertainty in the Polish Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Emission Inventory Using Monte Carlo Simulation. Outlook Agric 2014, 43, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Peng, S.; Yin, Y.; Ciais, P.; Havlik, P.; Herrero, M. The Key Role of Production Efficiency Changes in Livestock Methane Emission Mitigation. AGU Advances 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, J.H.; Cushman, R.A.; Dechow, C.D.; Dobson, H.; Humblot, P.; Hutjens, M.F.; Jones, G.A.; Ruegg, P.S.; Sheldon, I.M.; Stevenson, J.S. Invited Review: Learning from the Future—A Vision for Dairy Farms and Cows in 2067. Journal of Dairy Science 2018, 101, 3722–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salter, A.M. Improving the Sustainability of Global Meat and Milk Production. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Ward, J.H. Hierarchical Grouping to Optimize an Objective Function. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganivet, E. Growth in Human Population and Consumption Both Need to Be Addressed to Reach an Ecologically Sustainable Future. Environ Dev Sustain 2020, 22, 4979–4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Proudman, J.; Mitloehner, F.M. Rethinking Methane from Animal Agriculture. CABI Agric Biosci 2021, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, I.C.D.F.; Barbosa, F.A.; Tomich, T.R.; Ribeiro, L.G.P.; Alvarenga, R.C.; Lopes, L.S.; Malacco, V.M.R.; Rowntree, J.E.; Thompson, L.R.; Lana, Â.M.Q. Could the Breed Composition Improve Performance and Change the Enteric Methane Emissions from Beef Cattle in a Tropical Intensive Production System? PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haas, Y.; Veerkamp, R.F.; De Jong, G.; Aldridge, M.N. Selective Breeding as a Mitigation Tool for Methane Emissions from Dairy Cattle. Animal 2021, 15, 100294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, M.L.; Rhoads, R.P.; VanBaale, M.J.; Collier, R.J.; Sanders, S.R.; Weber, W.J.; Crooker, B.A.; Baumgard, L.H. Effects of Heat Stress and Plane of Nutrition on Lactating Holstein Cows: I. Production, Metabolism, and Aspects of Circulating Somatotropin. Journal of Dairy Science 2009, 92, 1986–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summer, A.; Lora, I.; Formaggioni, P.; Gottardo, F. Impact of Heat Stress on Milk and Meat Production. Animal Frontiers 2019, 9, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardone, A.; Ronchi, B.; Lacetera, N.; Bernabucci, U. Climatic Effects on Productive Traits in Livestock. Vet Res Commun 2006, 30, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; McCarl, B.; Fei, C. Climate Change and Livestock Production: A Literature Review. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bačėninaitė, D.; Džermeikaitė, K.; Antanaitis, R. Global Warming and Dairy Cattle: How to Control and Reduce Methane Emission. Animals 2022, 12, 2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tian, H.; Shi, H.; Pan, S.; Chang, J.; Dangal, S.R.S.; Qin, X.; Wang, S.; Tubiello, F.N.; Canadell, J.G.; et al. A 130-year Global Inventory of Methane Emissions from Livestock: Trends, Patterns, and Drivers. Global Change Biology 2022, 28, 5142–5158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tian, H.; Shi, H.; Pan, S.; Qin, X.; Pan, N.; Dangal, S.R.S. Methane Emissions from Livestock in East Asia during 1961−2019. Ecosyst Health Sustain 2021, 7, 1918024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cattle (mln heads) | Cattle density (heads/1000 ha of agricultural land) | Cattle heads per 1000 people | |||||||

| country | 1961–1970 | 2011–2020 | Change* | 1961–1970 | 2011–2020 | Change | 1961–1970 | 2011–2020 | Change |

| Argentina | 46.3 | 52.4 | 13% | 351 | 451 | 29% | 2497 | 1347 | -46% |

| Australia | 19.0 | 26.9 | 41% | 39 | 73 | 88% | 2082 | 1331 | -36% |

| Burkina Faso | 2.2 | 9.4 | 326% | 269 | 773 | 188% | 494 | 684 | 39% |

| Bangladesh | 23.0 | 23.7 | 3% | 2392 | 2505 | 5% | 521 | 171 | -67% |

| Bolivia | 2.1 | 9.1 | 345% | 68 | 243 | 255% | 614 | 982 | 60% |

| Brazil | 65.2 | 214.4 | 229% | 376 | 911 | 142% | 1052 | 1155 | 10% |

| Canada | 11.5 | 11.8 | 2% | 182 | 203 | 12% | 738 | 367 | -50% |

| China | 52.6 | 63.1 | 20% | 147 | 120 | -19% | 88 | 49 | -45% |

| Colombia | 17.5 | 24.5 | 40% | 415 | 532 | 28% | 1310 | 585 | -55% |

| Germany | 18.4 | 12.3 | -33% | 948 | 735 | -22% | 257 | 151 | -41% |

| France | 20.7 | 18.9 | -9% | 614 | 657 | 7% | 477 | 313 | -34% |

| Indonesia | 6.7 | 15.7 | 135% | 174 | 264 | 52% | 87 | 69 | -20% |

| India | 175.9 | 190.7 | 8% | 993 | 1063 | 7% | 445 | 167 | -63% |

| Kenya | 7.6 | 19.9 | 162% | 301 | 718 | 139% | 1162 | 560 | -52% |

| Mexico | 19.6 | 33.7 | 72% | 200 | 343 | 71% | 630 | 323 | -49% |

| Mali | 4.5 | 10.7 | 137% | 143 | 260 | 82% | 909 | 824 | -9% |

| Myanmar | 6.1 | 14.0 | 128% | 575 | 1091 | 90% | 316 | 294 | -7% |

| Niger | 4.0 | 12.6 | 216% | 126 | 274 | 118% | 1339 | 919 | -31% |

| Nigeria | 7.4 | 19.9 | 169% | 128 | 290 | 127% | 183 | 143 | -22% |

| New Zealand | 7.4 | 10.1 | 37% | 467 | 941 | 102% | 3484 | 2480 | -29% |

| Pakistan | 14.4 | 42.2 | 194% | 394 | 1159 | 194% | 352 | 245 | -30% |

| Paraguay | 4.4 | 13.7 | 212% | 404 | 820 | 103% | 2623 | 2517 | -4% |

| Chad | 4.4 | 25.8 | 488% | 92 | 516 | 462% | 1607 | 2632 | 64% |

| Turkey | 13.1 | 14.7 | 12% | 350 | 385 | 10% | 554 | 216 | -61% |

| Tanzania | 9.2 | 26.3 | 185% | 343 | 683 | 99% | 1067 | 674 | -37% |

| Uganda | 3.6 | 13.8 | 279% | 377 | 960 | 155% | 558 | 501 | -10% |

| Uruguay | 8.6 | 11.6 | 35% | 539 | 814 | 51% | 3649 | 3506 | -4% |

| United States of America | 106.9 | 92.0 | -14% | 244 | 227 | -7% | 668 | 311 | -53% |

| Venezuela | 7.3 | 16.2 | 122% | 373 | 755 | 102% | 1100 | 615 | -44% |

| South Africa | 11.7 | 13.3 | 14% | 120 | 138 | 15% | 807 | 272 | -66% |

| Country | Gro-up | Agricultural land | Farm machinery | GDP per capita | Land under perm. meadows and pastures | Meat beef consumption per capita | Meat total (incl. fish and seafood) consumption per capita | Milk consumption per capita | Milk yield per animal | Rural population percent | Total population |

| Chad | 0 | 0.98 | -0.13 | 0.75 | 0.00 | 0.85 | 0.89 | -0.72 | -0.80 | -0.75 | 0.98 |

| Burkina Faso | 1 | 0.98 | 0.44 | 0.98 | 0.00 | 0.76 | 0.85 | 0.03 | -0.70 | -0.95 | 0.98 |

| Mali | 0.85 | -0.24 | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.43 | 0.28 | 0.31 | -0.84 | -0.86 | 0.95 | |

| Niger | 0.91 | -0.02 | -0.29 | 0.88 | -0.33 | -0.49 | -0.41 | 0.80 | -0.53 | 0.92 | |

| Pakistan | 0.02 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 0.06 | 0.92 | -0.89 | 0.96 | |

| Uganda | 0.87 | 0.69 | 0.96 | 0.93 | -0.38 | 0.33 | 0.79 | 0.53 | -0.44 | 0.93 | |

| Bolivia | 2 | 0.94 | 0.50 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.79 | 0.94 | -0.97 | 0.98 |

| Brazil | 0.78 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.66 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.79 | -0.99 | 0.99 | |

| Indonesia | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.96 | -0.74 | 0.82 | 0.96 | 0.25 | 0.91 | -0.94 | 0.94 | |

| Kenya | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.00 | -0.36 | -0.18 | 0.37 | 0.74 | -0.88 | 0.92 | |

| Mexico | 0.47 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.04 | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.61 | 0.78 | -0.94 | 0.88 | |

| Myanmar | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.74 | -0.24 | 0.57 | 0.78 | 0.65 | 0.90 | -0.78 | 0.90 | |

| Nigeria | 0.71 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.23 | -0.62 | 0.50 | -0.36 | 0.17 | -0.97 | 0.95 | |

| Paraguay | 0.97 | 0.77 | 0.96 | 0.82 | -0.68 | -0.45 | 0.72 | 0.80 | -0.96 | 0.98 | |

| Tanzania | 0.94 | -0.46 | 0.97 | 0.82 | -0.19 | -0.50 | 0.15 | 0.96 | -0.86 | 0.97 | |

| Venezuela | -0.72 | 0.44 | 0.57 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.52 | -0.08 | -0.78 | -0.90 | 0.85 | |

| Argentina | 3 | -0.34 | 0.05 | 0.32 | -0.39 | -0.10 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.15 | -0.42 | 0.31 |

| Australia | -0.28 | 0.50 | 0.49 | -0.28 | 0.14 | 0.59 | -0.56 | 0.43 | -0.56 | 0.46 | |

| Bangladesh | 0.27 | -0.04 | -0.05 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.01 | -0.09 | 0.45 | 0.17 | -0.13 | |

| Canada | 0.10 | -0.10 | -0.53 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.51 | -0.05 | 0.25 | -0.26 | 0.25 | |

| China | 0.71 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 0.71 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.23 | -0.24 | 0.56 | |

| Colombia | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.67 | 0.61 | -0.38 | 0.53 | 0.39 | 0.36 | -0.85 | 0.72 | |

| France | 0.52 | 0.77 | -0.54 | 0.71 | 0.80 | 0.04 | 0.53 | -0.69 | 0.31 | -0.54 | |

| Germany | 0.79 | 0.97 | -0.91 | 0.78 | 0.94 | 0.13 | -0.05 | -0.88 | 0.69 | -0.59 | |

| India | 0.81 | 0.33 | 0.32 | -0.72 | -0.16 | 0.51 | 0.69 | 0.43 | -0.63 | 0.54 | |

| New Zealand | -0.80 | 0.81 | 0.93 | -0.70 | -0.57 | -0.04 | -0.51 | 0.81 | -0.77 | 0.85 | |

| South Africa | 0.21 | -0.57 | 0.30 | 0.07 | -0.35 | 0.42 | -0.63 | 0.54 | -0.61 | 0.64 | |

| Turkey | -0.65 | -0.18 | 0.12 | -0.32 | 0.30 | 0.10 | 0.75 | 0.08 | 0.12 | -0.07 | |

| Uruguay | -0.75 | 0.19 | 0.74 | -0.64 | -0.73 | -0.68 | 0.09 | 0.71 | -0.80 | 0.82 | |

| USA | 0.67 | 0.24 | -0.75 | -0.05 | 0.92 | -0.58 | 0.27 | -0.75 | 0.60 | -0.72 |

| CT | CT/AL | CT/TP | AL | FM | GDP | LMP | MBC | MTC | MC | MYA | RPP | TP | |

| Cattle population (CT) | 0.13 | -0.11 | 0.50 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.05 | -0.09 | 0.57 | |

| Cattle/agricultural land (CT/AL) | 0.13 | 0.03 | -0.37 | -0.07 | -0.26 | -0.41 | -0.27 | -0.30 | -0.17 | -0.34 | 0.27 | -0.02 | |

| Cattle/total population (CT/TP) | -0.11 | 0.03 | -0.16 | -0.21 | 0.07 | -0.06 | 0.46 | 0.11 | 0.19 | -0.06 | -0.25 | -0.32 | |

| Agricultural land (AL) | 0.50 | -0.37 | -0.16 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.96 | 0.28 | 0.48 | 0.25 | 0.36 | -0.19 | 0.65 | |

| Farm machinery (FM) | 0.14 | -0.07 | -0.21 | 0.56 | 0.21 | 0.52 | -0.10 | 0.31 | 0.08 | 0.24 | -0.10 | 0.70 | |

| GDP per capita (GDP) | 0.00 | -0.26 | 0.07 | 0.38 | 0.21 | 0.40 | 0.56 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.88 | -0.66 | -0.08 | |

| Land under perm. meadows and pastures (LMP) | 0.33 | -0.41 | -0.06 | 0.96 | 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.54 | 0.27 | 0.33 | -0.24 | 0.47 | |

| Meat beef consumption per capita (MBC) | 0.21 | -0.27 | 0.46 | 0.28 | -0.10 | 0.56 | 0.34 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.62 | -0.75 | -0.27 | |

| Meat total (incl. fish and seafood) consumption per capita (MTC) | 0.11 | -0.30 | 0.11 | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.79 | 0.54 | 0.73 | 0.68 | 0.79 | -0.74 | -0.02 | |

| Milk consumption per capita (MC) | 0.16 | -0.17 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.80 | 0.27 | 0.74 | 0.68 | 0.78 | -0.81 | -0.16 | |

| Milk yield per animal (MYA) | 0.05 | -0.34 | -0.06 | 0.36 | 0.24 | 0.88 | 0.33 | 0.62 | 0.79 | 0.78 | -0.70 | 0.00 | |

| Rural population percent (RPP) | -0.09 | 0.27 | -0.25 | -0.19 | -0.10 | -0.66 | -0.24 | -0.75 | -0.74 | -0.81 | -0.70 | 0.17 | |

| Total population (TP) | 0.57 | -0.02 | -0.32 | 0.65 | 0.70 | -0.08 | 0.47 | -0.27 | -0.02 | -0.16 | 0.00 | 0.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).