Submitted:

09 May 2023

Posted:

10 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

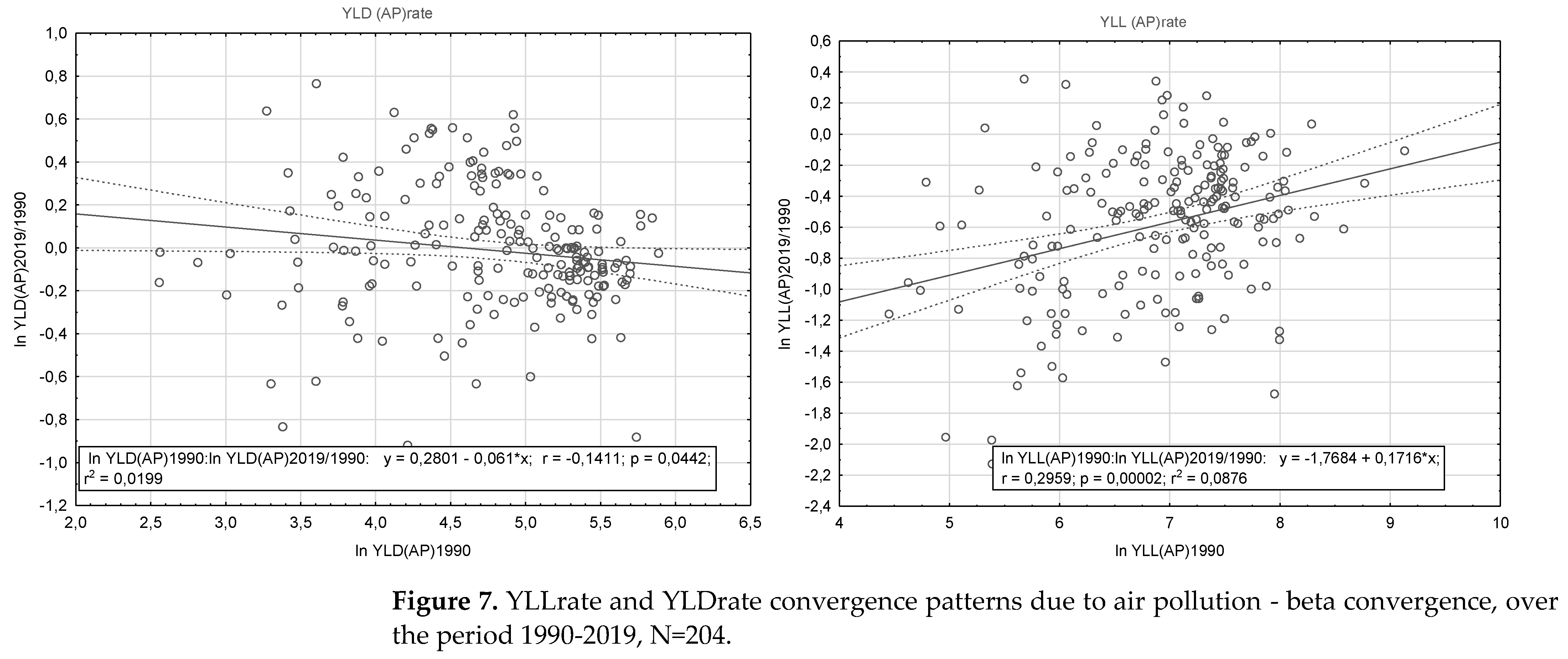

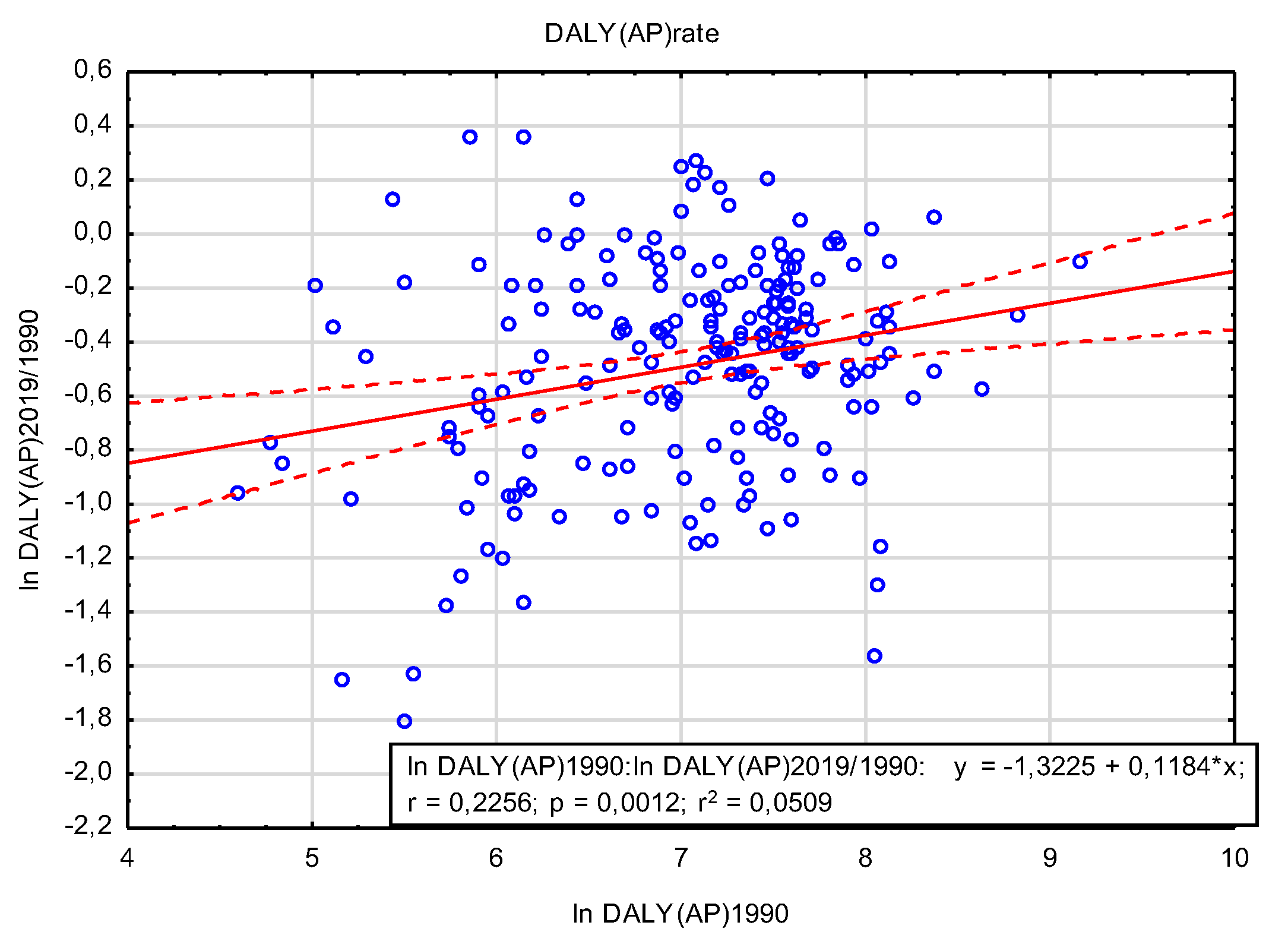

- a)

- YLL (AP)rate variable:

- b)

- YLD variable (AP)rate:

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cole, M.A.; Neumayer, E. The impact of poor health on total factor productivity. The Journal of Development Studies 2006, 42(6), 918-938. [CrossRef]

- William J.; Lewis, M. Health investments and economic growth: Macroeconomic evidence and microeconomic foundations; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series, 2009.

- Jakubowska, A.; Bilan, S.; Werbiński, J. Chronic diseases and labour resources: “Old and new” European Union member states. Journal of International Studies 2021, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Bialowolski, P.; McNeely, E.; VanderWeele, T.J.; Weziak-Bialowolska, D. Ill health and distraction at work: Costs and drivers for productivity loss. Plos one 2020, 15(3), e0230562. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, H. How to analyze work productivity loss due to health problems in randomized controlled trials? A simulation study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2021, 130. [CrossRef]

- Krol, M.; Brouwer, W. How to estimate productivity costs in economic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics 2014, 32, 335-344. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, T.; Oka, H.; Fujii, T.; Nagata, T.; Matsudaira, K. The Economic Burden of Lost Productivity due to Presenteeism Caused by Health Conditions Among Workers in Japan. J Occup Environ Med. 2020, Oct;62(10):883-888. PMID: 32826548; PMCID: PMC7537733. [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.R.; Shaw, C.A.; Langrish, J.P. From particles to patients: oxidative stress and the cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Future Cardiol 2012, Jul;8(4):577-602PMID: 22871197. [CrossRef]

- Van Rijn, R.M.; Robroek, S.J.; Brouwer, S.; Burdorf, A. Influence of poor health on exit from paid employment: a systematic review. Occupational and environmental medicine 2014, 71(4), 295-301. [CrossRef]

- Rice, N.E.; Lang, I.A.; Henley, W.; Melzer, D. Common health predictors of early retirement: findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age Ageing 2011, 40(1), 54-61. [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, W.; Verbooy, K.; Hoefman, R. et al. Production Losses due to Absenteeism and Presenteeism: The Influence of Compensation Mechanisms and Multiplier Effects. PharmacoEconomics 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bloom, D.E.; Canning, D.; Fink, G. Disease and development revisited. Journal of Political Economy 2014, 122(6), 1355-1366. [CrossRef]

- Abegunde, D.; Stanciole, A. An estimation of the economic impact of chronic noncommunicable diseases in selected countries, Working paper; WHO Department of Chronic Diseases and Health Promotion, CHP, 2006.

- Brown, S.; Sessions, J.G. The economics of absence: theory and evidence. Journal of economic surveys 1996, 10(1), 23-53.

- GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, Oct 17;396(10258):1223-1249. PMID: 33069327; PMCID: PMC7566194. [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results. Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2020. Available from https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

- Stern, D.I. The environmental Kuznets curve. Companion to Environmental Studies 2018, 49(54), 49-54.

- Kuznets, S. Economic growth and income inequality. The American economic review 1955, 45(1), 1-28.

- Dinda, S. Environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis: a survey. Ecological economics 2004, 49(4), 431-455.

- Chen, J.; Hu, T.E.; Van Tulder, R. Is the environmental Kuznets curve still valid: a perspective of wicked problems. Sustainability 2019, 11(17), 4747. [CrossRef]

- Leal P.H.; Marques A.C. The evolution of the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis assessment: A literature review under a critical analysis perspective. Heliyon. 2022 Nov 11;8(11):e11521. PMID: 36406679; PMCID: PMC9668524. [CrossRef]

- Ojaghlou, M.; Ugurlu, E.; Kadłubek, M.; Thalassinos, E. Economic Activities and Management Issues for the Environment: An Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) and STIRPAT Analysis in Turkey. Resources 2023, 12, 57. [CrossRef]

- Mannucci, P.M.; Franchini, M. Health Effects of Ambient Air Pollution in Developing Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1048. [CrossRef]

- Mannucci, P.M.; Harari, S.; Franchini, M. Novel evidence for a greater burden of ambient air pollution on cardiovascular disease. Haematologica 2019, Dec;104(12):2349-2357. [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Fuster, V. The Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks: A Compass for Global Action. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, Dec 22;76(25):2980-2981. PMID: 33309174. [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, S.; Al-Kindi, S.; Brook R, et al. Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Oct, 72(17) 2054–2070. [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Yu, S.; Pei, Y.; Peng, C.; Liao, Y.; Liu, N.; Ji, J.; Cheng, J. Association between Airborne Fine Particulate Matter and Residents’ Cardiovascular Diseases, Ischemic Heart Disease and Cerebral Vascular Disease Mortality in Areas with Lighter Air Pollution in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1918. [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, M.; Poulsen, A. H.; Hvidtfeldt, U. A.; Christensen, J. H.; Brandt, J.; Frohn, L. M.; ... & Raaschou-Nielsen, O. Effects of Sociodemographic Characteristics, Comorbidity, and Coexposures on the Association between Air Pollution and Type 2 Diabetes: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Environmental health perspectives 2023, 131(2), 027008. [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, A. Neurological Disorders from Ambient (Urban) Air Pollution Emphasizing UFPM and PM2.5 . Curr Pollution Rep 2016, 2, 203–211. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, W.H.; Kim, Y.Y.; Park, H.Y. Air pollution and central nervous system disease: a review of the impact of fine particulate matter on neurological disorders. Frontiers in Public Health 2020, 8, 575330. [CrossRef]

- Aldraihem, M.O.; Al-Ghamdi, F.; Murtaza, G. et al. Air pollution and performance of the brain. Arab J Geosci 2020, 13, 1158. [CrossRef]

- Buoli, M.; Grassi, S.; Caldiroli, A.; Carnevali, G.S.; Mucci, F.; Iodice, S.; ... & Bollati, V. Is there a link between air pollution and mental disorders?. Environment international 2018, 118, 154-168. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Plana-Ripoll, O.; Antonsen, S.; Brandt, J.; Geels, C.; Landecker, H.; ... & Rzhetsky, A. Environmental pollution is associated with increased risk of psychiatric disorders in the US and Denmark. PLoS biology 2019, 17(8), e3000353. [CrossRef]

- Attademo, L.; Bernardini, F.; Garinella, R.; Compton, M.T. Environmental pollution and risk of psychotic disorders: A review of the science to date. Schizophrenia research 2017, 181, 55-59. [CrossRef]

- Hahad, O.; Lelieveld, J.; Birklein, F.; Lieb, K.; Daiber, A.; Münzel, T. Ambient Air Pollution Increases the Risk of Cerebrovascular and Neuropsychiatric Disorders through Induction of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4306. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Duong, M.; Brauer, M.; Rangarajan, S.; Dans, A.; Lanas, F., ... & Hystad, P. Household Air Pollution and Adult Lung Function Change, Respiratory Disease, and Mortality across Eleven Low-and Middle-Income Countries from the PURE Study. Environmental Health Perspectives 2023, 131(4), 047015. [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, R.P. The Relationship between Ambient Fine Particulate Matter (PM2.5) Pollution and Depression: An Analysis of Data from 185 Countries. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 597. [CrossRef]

- Migliore, L.; Coppedè, F. Environmental-induced oxidative stress in neurodegenerative disorders and aging. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis 2009, 674(1-2), 73-84. [CrossRef]

- Argacha, J.F.; Bourdrel, T.; van de Borne, P. Ecology of the cardiovascular system: A focus on air-related environmental factors. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2018, Feb;28(2):112-126. [CrossRef]

- Franchini, M.; Mannucci, P.M. Thrombogenicity and cardiovascular effects of ambient air pollution. Blood 2011, Sep 1;118(9):2405-12. Epub 2011 Jun 10. PMID: 21666054. [CrossRef]

- Laden, F.; Schwartz, J.; Speizer, F.E.; Dockery D.W. Reduction in fine particulate air pollution and mortality: Extended follow-up of the Harvard Six Cities study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006, Mar 15;173(6):667-72. Epub 2006 Jan 19. PMID: 16424447; PMCID: PMC2662950. [CrossRef]

- Williams, A., Calculating the global burden of disease: time for a strategic reappraisal?, Health economics 1999, 8(1), 1-8.

- Łyszczarz, B.; Sowa, K. Production losses due to mortality associated with modifiable health risk factors in Poland. The European Journal of Health Economics 2022, 23(1), 33-45. [CrossRef]

- Mahrouseh, N.; Chen-Xu, J.; Charalampous, P.; Eikemo, T.; Varga, O.; Grad, D.; ... & Baravelli, C. Premature mortality and levels of inequality in years of life lost across 296 regions of 31 european countries in 2019: A burden of disease study. Population Medicine 2023, 5. [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Air Pollution Exposure Estimates 1990-2019. Seattle, United States of America: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2021.

- Global Burden of Disease Health Financing Collaborator Network produced estimates for Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from 1960-2050. Estimates are reported as GDP per person in constant 2021 purchasing-power parity-adjusted (PPP) dollars. https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/global-gdp-per-capita-1960-2050-fgh-2021.

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Air Pollution. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/air-pollution [Online Resource], https://ourworldindata.org/air-pollution#citation.

- Davidson, C.I.; Phalen, R.F.; Solomon, P.A. Airborne particulate matter and human health: a review. Aerosol Science and Technology 2005, 39(8), 737-749. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kindi, S.G.; Brook, R.D.; Biswal, S. et al. Environmental determinants of cardiovascular disease: lessons learned from air pollution. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020, 17, 656–672. [CrossRef]

- Agibayeva, A.; Guney, M.; Karaca, F.; Kumisbek, A.; Kim, J.R.; Avcu, E. Analytical Methods for Physicochemical Characterization and Toxicity Assessment of Atmospheric Particulate Matter: A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13481. [CrossRef]

- Hassan Bhat, T.; Jiawen, G.; Farzaneh, H. Air Pollution Health Risk Assessment (AP-HRA), Principles and Applications. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1935. [CrossRef]

- Ogrizek, M.; Kroflič, A.; Šala, M. Critical review on the development of analytical techniques for the elemental analysis of airborne particulate matter. Trends in Environmental Analytical Chemistry 2022, e00155. [CrossRef]

- Lavigne, E.; Burnett, R.T.; Weichenthal, S. Association of short-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution and mortality: effect modification by oxidant gases. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 16097. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, H.; New WHO global air quality guidelines: more pressure on nations to reduce air pollution levels. The Lancet Planetary Health 2021, 5(11), e760-e761. [CrossRef]

- Lelieveld, J.; Evans, J.; Fnais, M. et al. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature 2015, 525(7569), 367–371. [CrossRef]

- WHO global air quality guidelines. Particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

- O'Neill, M.S.; Jerrett, M.; Kawachi, I.; Levy, J.I.; Cohen, A.J.; Gouveia, N.; ... & Workshop on Air Pollution and Socioeconomic Conditions. Health, wealth, and air pollution: advancing theory and methods. Environmental health perspectives 2003, 111(16), 1861-1870. [CrossRef]

- Hajat, A.; Hsia, C.; O’Neill, M.S. Socioeconomic disparities and air pollution exposure: a global review. Current environmental health reports 2015, 2(4), 440-450. [CrossRef]

- Gouveia N. Addressing Environmental Health Inequalities. International journal of environmental research and public health 2016, 13(9), 858. Doi: 10.3390/ijerph13090858.

- Goodman, A.; Wilkinson, P.; Stafford, M. et al. Characterising socio-economic inequalities in exposure to air pollution: a comparison of socio-economic markers and scales of measurement. Health Place 2011, 17(3), 767–774. [CrossRef]

- Molitor, J.; Su, J.; Molitor, NT.; et al. Identifying vulnerable populations through an examination of the association between multi-pollutant profiles and poverty. Environ Sci Technol. 2011, 45(18), 7754–7760. [CrossRef]

- Jakubowska, A.; Rabe, M. Air Pollution and Limitations in Health: Identification of Inequalities in the Burdens of the Economies of the “Old” and “New” EU. Energies 2022, 15, 6225. [CrossRef]

- Grandjean, P.; Bellanger, M. Calculation of the disease burden associated with environmental chemical exposures: application of toxicological information in health economic estimation. Environ Health 16, 123 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.L.; Edwards, S.E.; Keating, M.H.; Paul, C.J. Making the Environmental Justice Grade: The Relative Burden of Air Pollution Exposure in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 1755-1771. [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, J.; Schüle, S.A.; Dreger, S.; Karla Hilz, L.; Bolte, G. Social Inequalities in Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution: A Systematic Review in the WHO European Region. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3127. [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Srivastava, S.; Yang, L.; Jain, K.; Schröder, P. Understanding the impacts of outdoor air pollution on social inequality: Advancing a just transition framework. Local Environment 2020, 25(1), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Santana, P.; Almendra, R.; Pilot, E.; Doreleijers, S.; Krafft, T. Environmental inequalities in global health. In: Handbook of Global Health; Kickbusch, I., Ganten, D., Moeti, M., Eds.; Springer, Cham,2021. [CrossRef]

- Spalt, E.W.; Curl, C.L.; Allen R.W. et al. Factors influencing time-location patterns and their impact on estimates of exposure: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and Air Pollution (MESA Air). J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2016, Jun;26(4), 341-8. [CrossRef]

- Samet, J.M.. The environment and health inequalities: problems and solutions. Journal of Health Inequalities 2019, 5(1), 21-27. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, G.S.; Spadaro, J.V.; Chapizanis, D.; Kendrovski, V.; Kochubovski, M.; Mudu, P. Health Impacts and Economic Costs of Air Pollution in the Metropolitan Area of Skopje. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 626. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, S.; Ren, Z.; Liu, H.; Tong, Y.; & Wang, N. Life expectancy, air pollution, and socioeconomic factors: a multivariate time-series analysis of Beijing City, China. Social Indicators Research 2022, 162(3). 979-994. [CrossRef]

- Pu, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z. et al. Non-linear relations between life expectancy, socio-economic, and air pollution factors: a global assessment with spatial disparities. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2022, 29, 53306–53318. [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Brauer, M.; Zhang, J.; Cai, W.; Navrud, S.; Burnett, R.; ... & Liu, Z. Global economic cost of deaths attributable to ambient air pollution: Disproportionate burden on the ageing population. medRxiv 2020, 2020.04.28.20083576. [CrossRef]

- Conti, S.; Ferrara, P.; D'Angiolella, L. S.; Lorelli, S. C.; Agazzi, G.; Fornari, C.; ... & Mantovani, L. G. The economic impact of air pollution: a European assessment. European Journal of Public Health 2020, 30(Supplement_5), ckaa165-084. [CrossRef]

- Nair, M.; Bherwani, H.; Mirza, S.; Anjum, S.; Kumar, R. Valuing burden of premature mortality attributable to air pollution in major million-plus non-attainment cities of India. Sci Rep. 2021, Dec 2;11(1):22771. [CrossRef]

- Safari, Z.; Fouladi-Fard, R.; Vahedian, M. et al. Health impact assessment and evaluation of economic costs attributed to PM2.5 air pollution using BenMAP-CE. Int J Biometeorol 2022, 66, 1891–1902. [CrossRef]

- Maiti, M.; Jadhav, P. Impact of pollution level, death rate and illness on economic growth: evidence from the global economy. SN Bus Econ 1, 109 (2021). [CrossRef]

| Risks | SEV 1990* | SEV 2019 | ARC 1990-2019 |

| I. Environmental/occupational risks | 52.55 (48.66-55.92)** |

45.36 (41.16-49.19) |

-0.51 (-0.62- -0.40)* |

| A. Air pollution | 45.37 (32.89-56.28) |

34.72 (25.86-44.40) |

-0.92 (-1.25- -0.61)* |

| A1. Particulate matter pollution | 44.26 (31.87-55.07) |

33.84 (25.08-43.43) |

-0.93 (-1.26- -0.61)* |

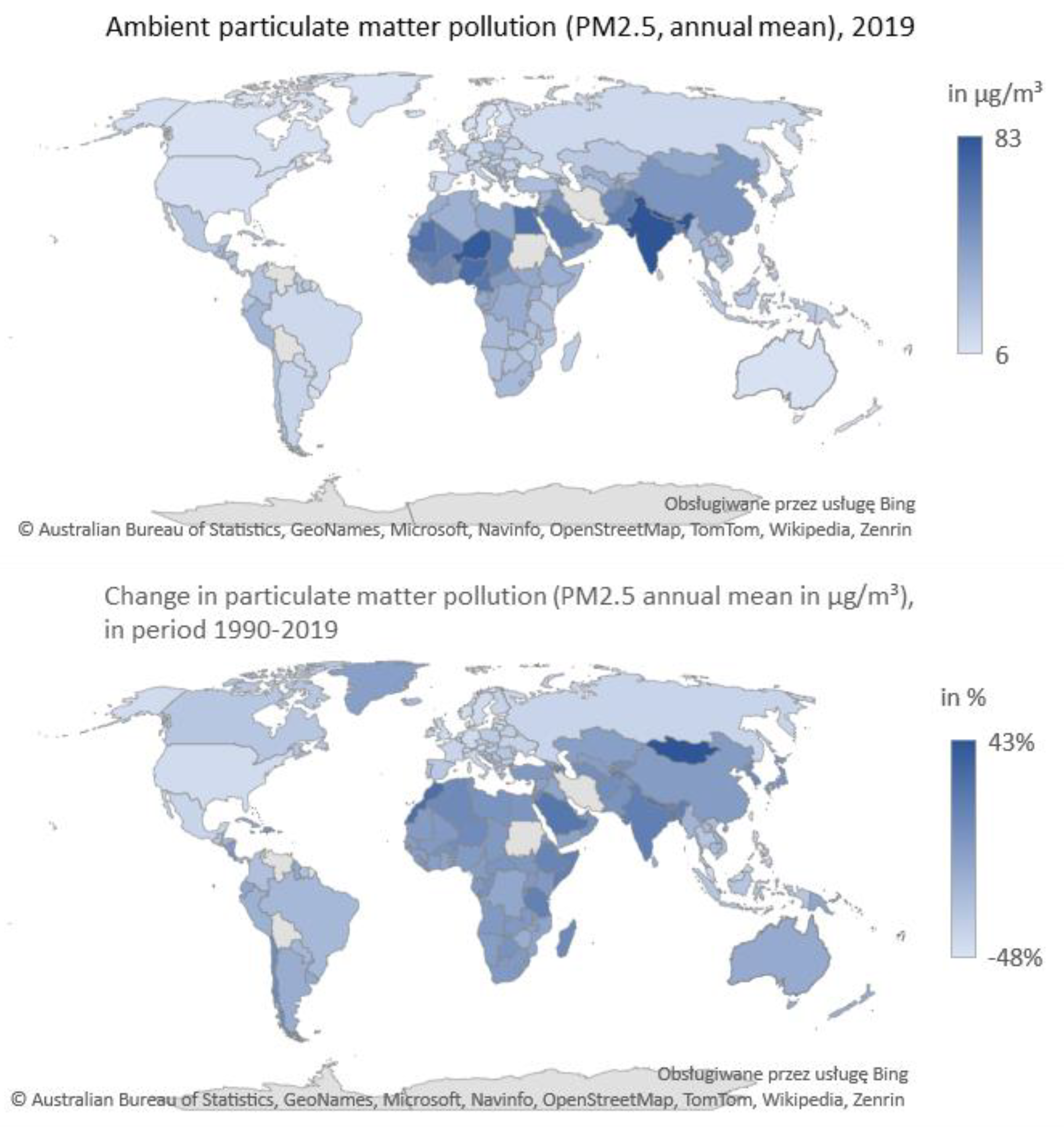

| A1a. Ambient particulate matter pollution | 15.65 (10.61-21.58) |

26.19 (21.55-30.48) |

1.78 (0.95-2.71)* |

| A1b. Household air pollution from solid fuels | 27.33 (16.18-38.86) |

12.04 (6.72-18.82) |

-2.83 (-3.53- -2.20)* |

| A2. Ambient ozone pollution | 50.67 (22.95-73.01) |

61.19 (32.26-80.39) |

0.65 (0.33-1.25)* |

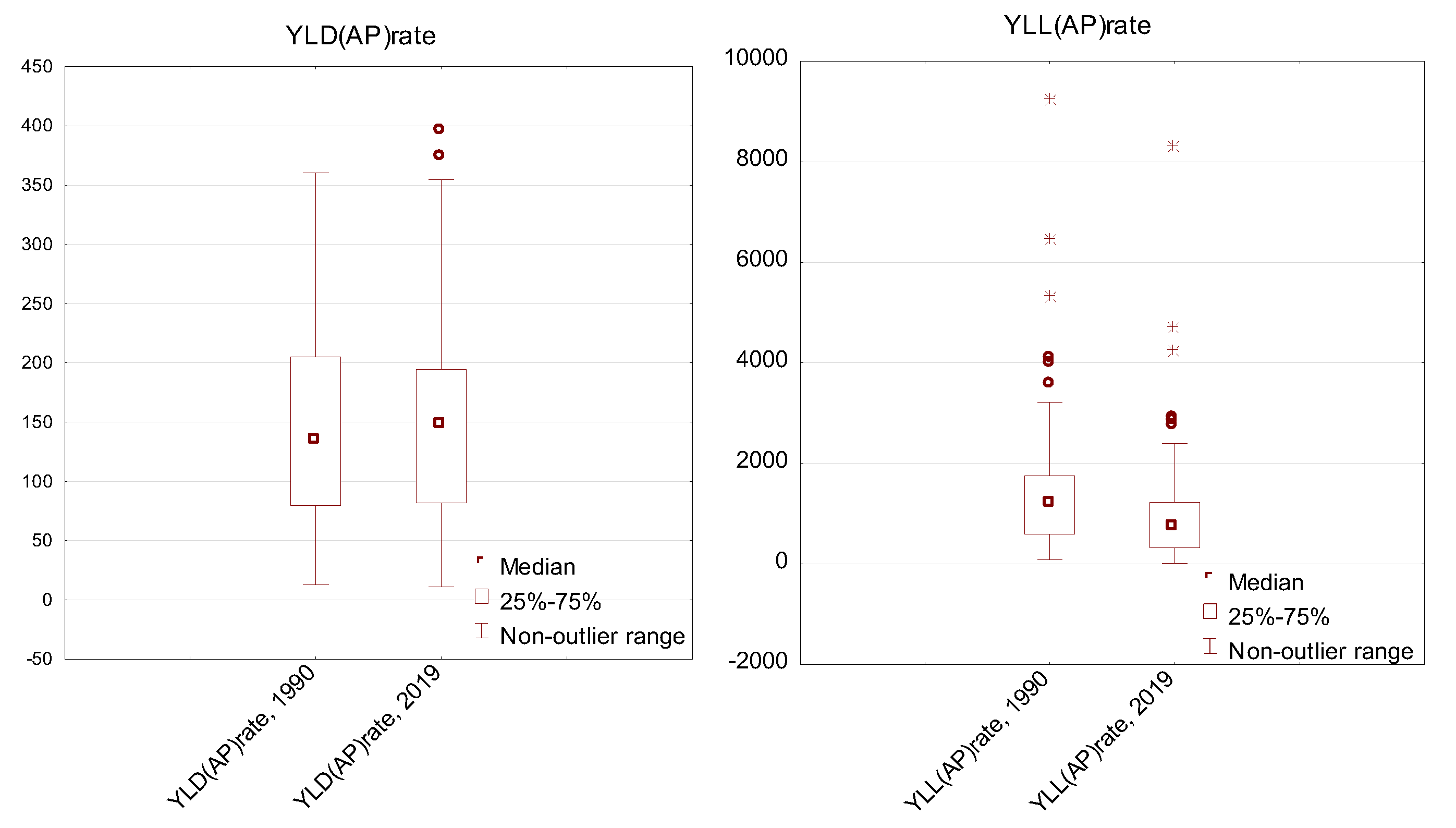

| Variable | Descriptive statistics | ||||||

| N valid | Mean | Min. | Max. | Variance | SD | CV | |

| YLL(AP)rate, 1990 | 204 | 1349,0 | 86,0 | 9249,9 | 1193365,6 | 1092,4 | 81,0 |

| YLL(AP)rate, 2019 | 204 | 879,8 | 20,4 | 8299,1 | 780868,3 | 883,7 | 100,4 |

| YLD(AP)rate, 1990 | 204 | 144,6 | 12,9 | 360,3 | 6259,0 | 79,1 | 54,7 |

| YLD(AP)rate, 2019 | 204 | 143,0 | 11,0 | 396,3 | 5674,7 | 75,3 | 52,7 |

| World Bank Income Group | YLLs (AP) 2019 | YLDs (AP) 2019 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate* | % in | Rate* | % in | |||

| all causes | NCD | all causes | NCD | |||

| 2019 | ||||||

| High Income | 219,4 | 3,1% | 4,2% | 68,7 | 0,5% | 0,6% |

| Upper Middle Income | 771,5 | 7,6% | 12,4% | 163,6 | 1,6% | 1,9% |

| Lower Middle Income | 1343,0 | 9,5% | 16,3% | 223,3 | 2,0% | 2,5% |

| Low Income | 1428,5 | 7,3% | 15,5% | 209,8 | 1,9% | 2,5% |

| Change over the period 1990-2019 (in %) | ||||||

| High Income | -50,0% | -31,5% | -40,3% | 7,9% | 3,4% | 1,4% |

| Upper Middle Income | -40,4% | -17,6% | -19,9% | -2,4% | -4,7% | -6,8% |

| Lower Middle Income | -22,6% | 12,6% | -7,5% | -7,6% | -4,1% | -7,2% |

| Low Income | -35,2% | 12,6% | -11,0% | -10,8% | -3,5% | -11,9% |

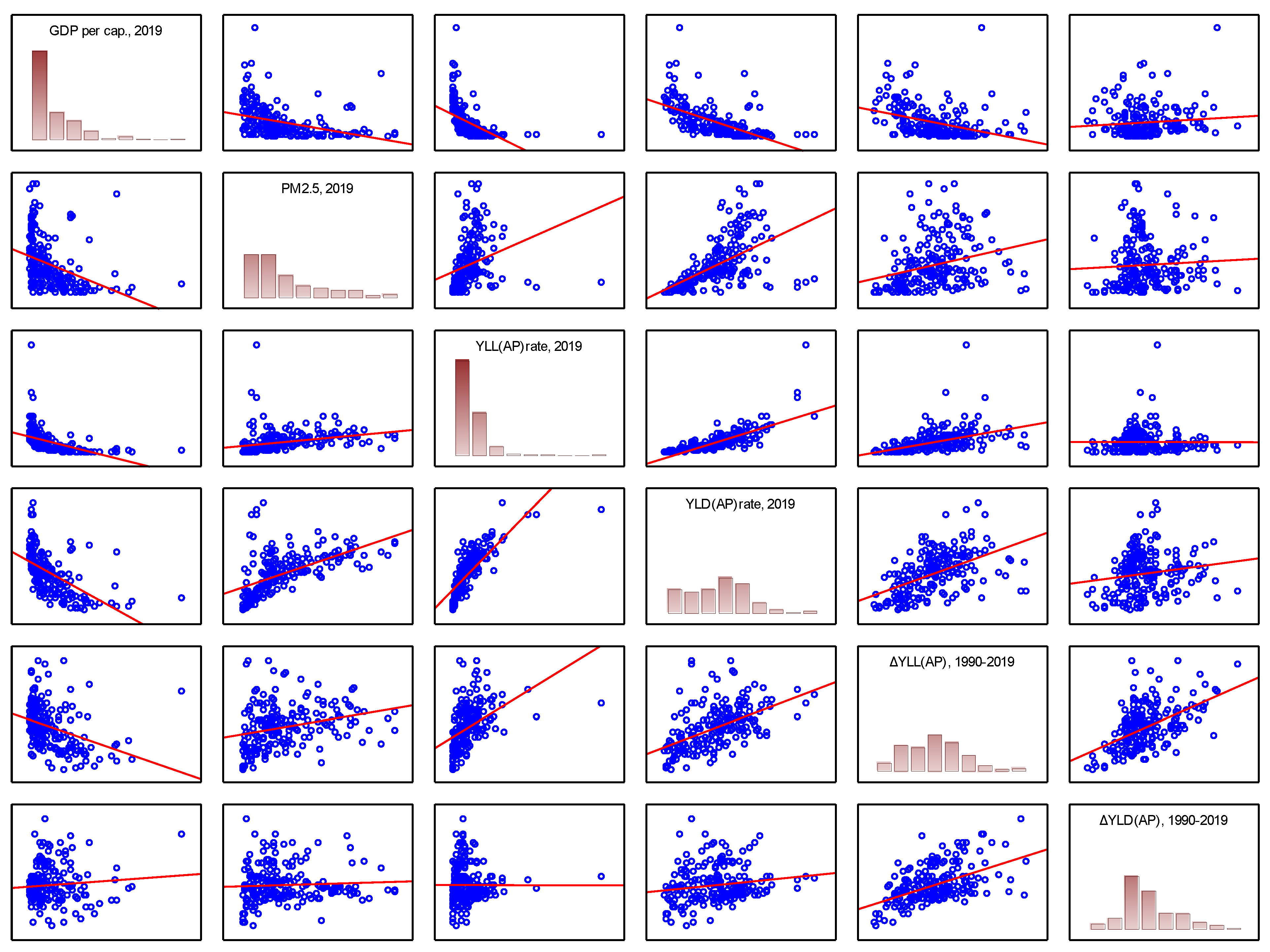

| Average | SD | GDP per cap., 20191 | PM2.5 (annual mean, µg/m3), 20192 | YLL(AP)rate, 20193 | YLD(AP)rate, 20193 | %ΔYLL(AP)rate, 1990-2019 | %ΔYLD(AP)rate, 1990-2019 | |

| GDP per cap., 2019 | 22658 | 24332 | 1,000 | -0,368* | -0,489* | -0,595* | -0,362* | 0,092 |

| PM2.5 (annual mean, µg/m3), 2019 | 26,1 | 17,7 | -0,368* | 1,000 | 0,283* | 0,560* | 0,274* | 0,056 |

| YLL(AP)rate, 2019 | 879,8 | 883,7 | -0,489* | 0,283* | 1,000 | 0,785* | 0,458* | -0,002 |

| YLD(AP)rate, 2019 | 143,0 | 75,3 | -0,595* | 0,560* | 0,785* | 1,000 | 0,516* | 0,163* |

| ΔYLL(AP)rate, 1990-2019 | -38% | 26% | -0,362* | 0,274* | 0,458* | 0,516* | 1,000 | 0,522* |

| ΔYLD(AP)rate, 1990-2019 | 3% | 31% | 0,092 | 0,056 | -0,002 | 0,163* | 0,522* | 1,000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).