Submitted:

09 May 2023

Posted:

09 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Antioxidant Intake and Its Relationship with BA in Smokers and Nonsmokers

4. Biomarkers of OS and Inflammation in Smoking and Nonsmoking Asthmatics

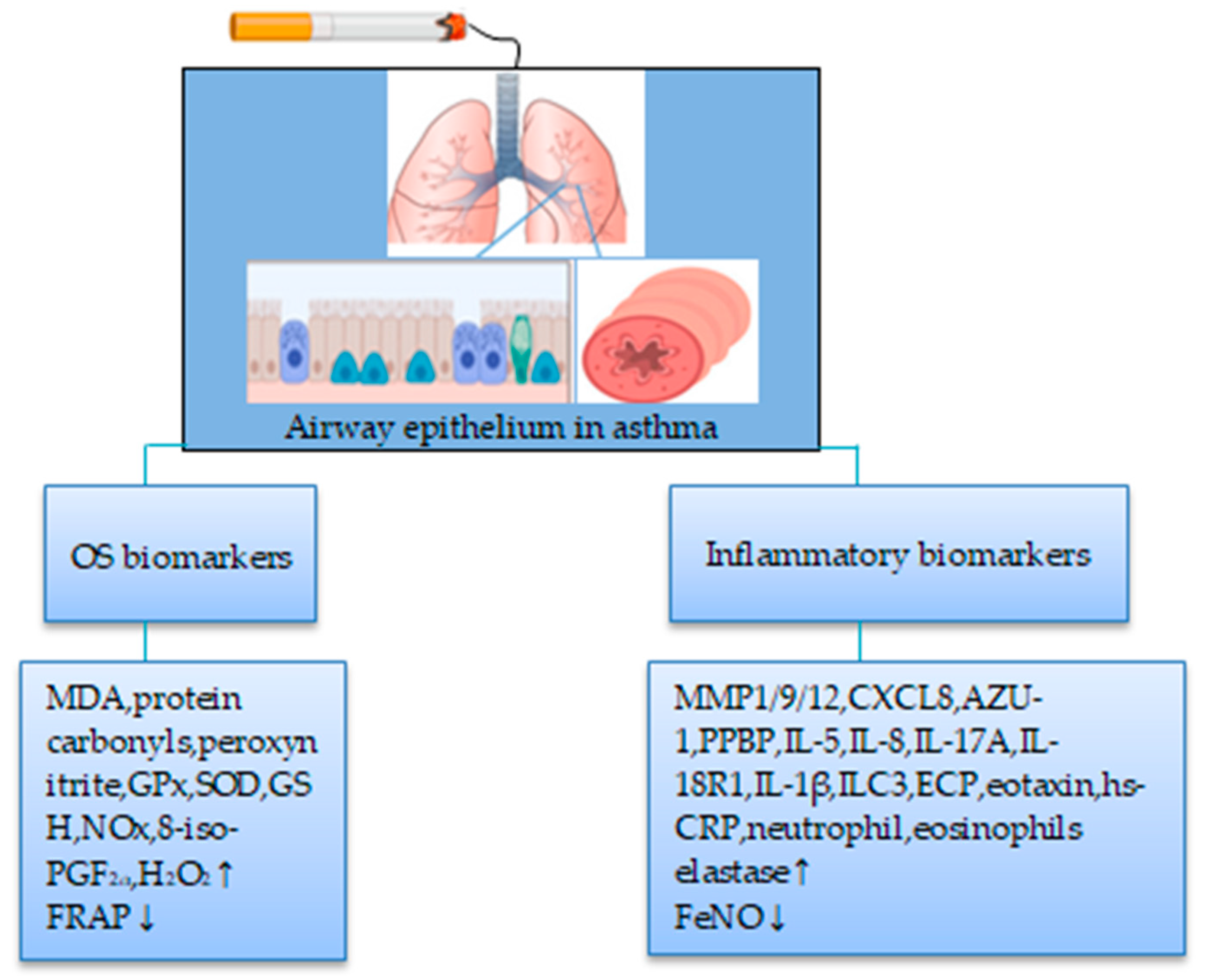

4.1. Smokers

4.1.1. Biomarkers of OS

4.1.2. Biomarkers of Inflammation

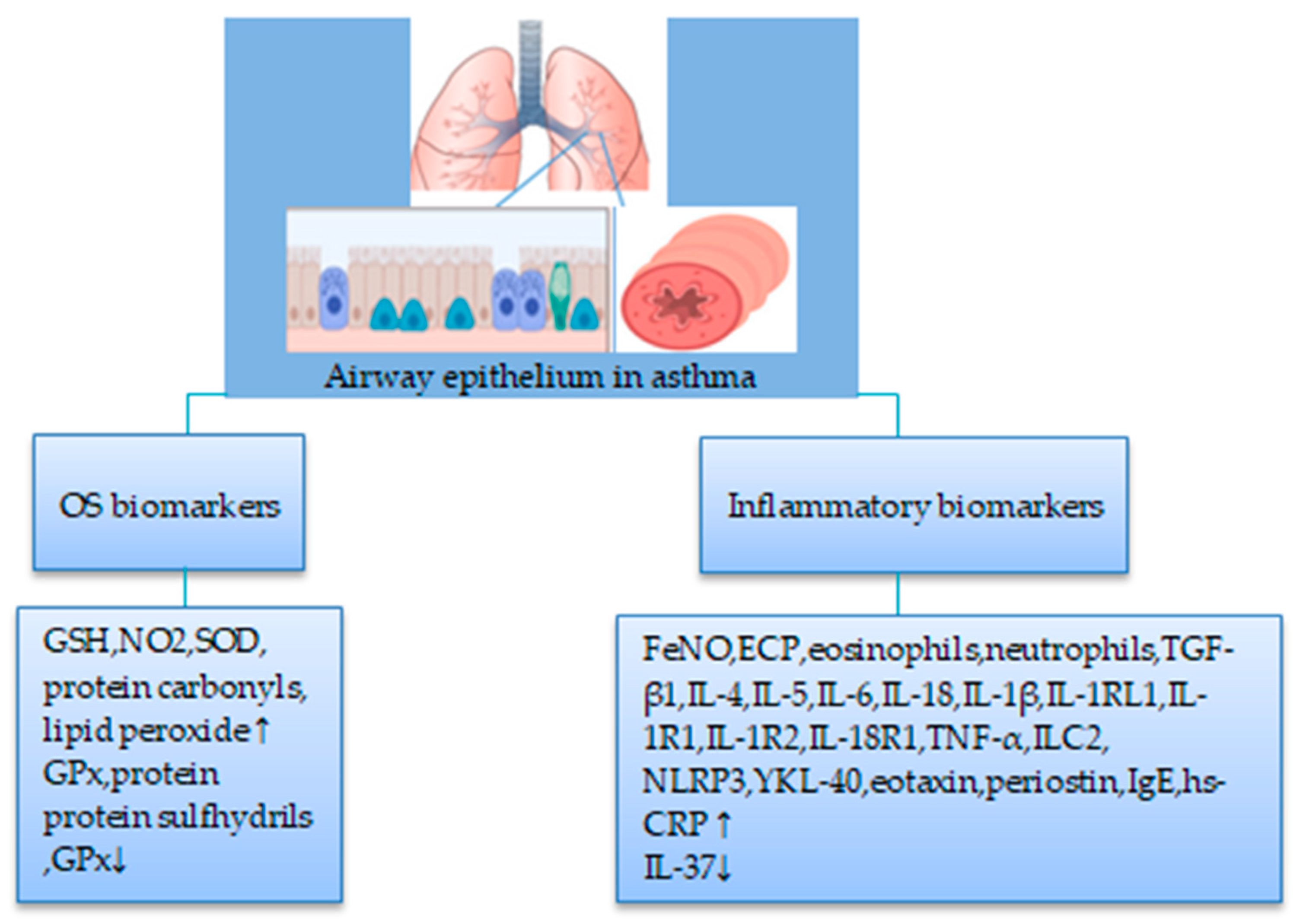

4.2. Nonsmokers

4.2.1. Biomarkers of OS

4.2.2. Biomarkers of Inflammation

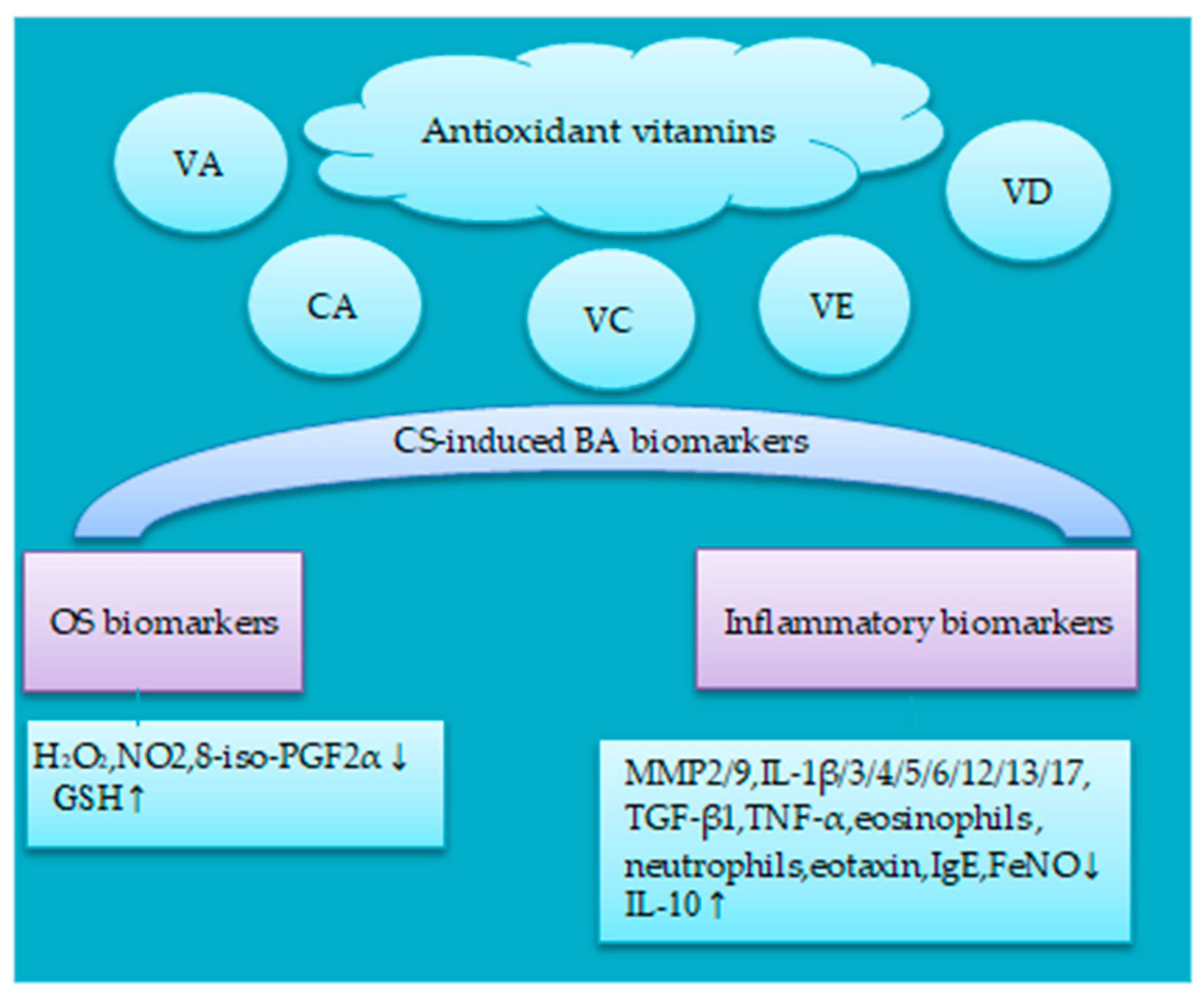

5. Potential Effects of Antioxidant on BA-Associated CS-Induced OS and Inflammation Biomarkers

5.1. Antioxidant Vitamins

5.1.1. Vitamin A

5.1.2. Carotenoids

5.1.3. Vitamin C and E

5.1.4. Vitamin D

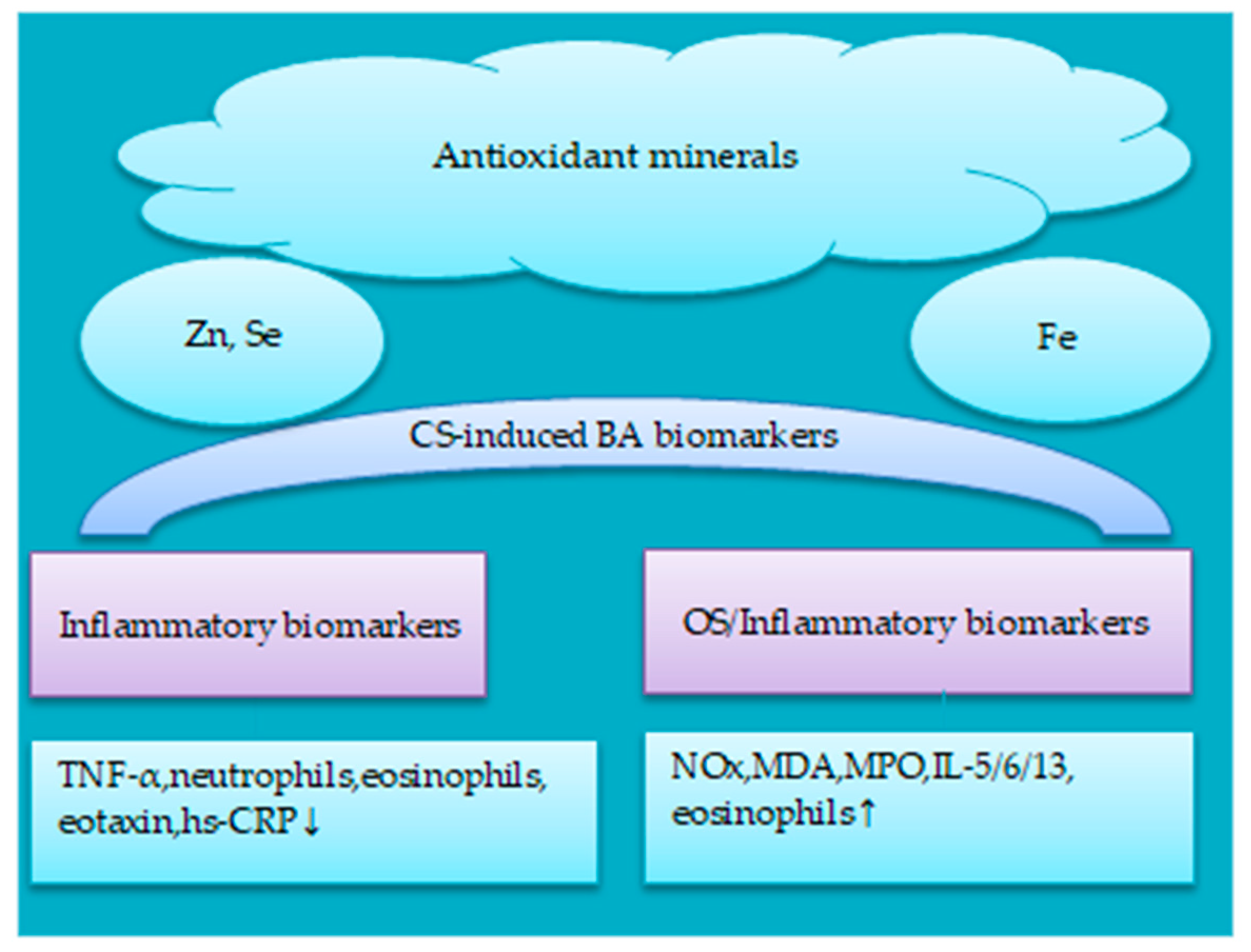

5.2. Antioxidant Minerals

5.2.1. Iron

5.2.2. Zinc, Selenium and Copper

6. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHR | Airway hyperresponsiveness |

| Akt | Serine-threonine kinase |

| AP-1 | Activator protein-1 |

| ASM | Airway smooth muscle |

| ATRA | All-trans RA |

| AZU-1 | Azurocidin 1 |

| BA | Bronchial asthma |

| BALF | Bronchoalveolar Lavavge Fluid |

| BaP | Benzo[a]pyrene |

| BCX | β-cryptoxanthin |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CS | Cigarette smoke |

| CSE | Cigarette smoke extract |

| Cu | Copper |

| CuONPs | Copper oxide nanoparticles |

| CuZnSOD | Zinc-superoxide dismutase |

| CXCL | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand |

| EBC | Expired breathe condensate |

| ECP | Eosinophilic cationic protein |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinases |

| ETS | Environmental tobacco smoke |

| Fe | Iron |

| FeNO | Fractional exhaled nitric oxide |

| FEV1 | Forced expiratory volume in 1s |

| FRAP | Ferric reducing ability of plasma |

| FVC | Forced vital capacity |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| GSH | Reduced glutathione |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| HBECs | Human bronchial epithelial cells |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| HGFR | Hepatocyte growth factor receptor |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha |

| HMGB1 | Mobility group box 1 protein |

| HO-1 | Heme-oxygenase-1 |

| hs-CRP | High-sensitivity C-reactive protein |

| ICS | Inhalation corticosteroid |

| IgE | Immunoglobulin E |

| IkBα | Inhibitory kappa B kinase |

| IL | Interleukin |

| ILC | Innate lymphoid cell |

| IL-18R1 | Interleukin 18 receptor 1 |

| IL-1RL1 | Interleukin 1 receptor-like 1 |

| 8-iso-PGF2α | Isoprostane-8-iso prostaglandin F2α |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| LABA | Long-acting β2 adrenergic |

| LC | Lung cancer |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| LP | Lipid peroxidation |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAPKs | Mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MMP | Matrix metallopeptidases |

| MPO | Myeloperoxidase |

| α7nAChR | α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor |

| NF-κB | Nuclear transcription factor-kappaB |

| NLRP | NLR Family CARD Domain Containing |

| NNK | Nitrosamine 4(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3–pyridyl)-1-butanone |

| NO2 | Nitrite |

| NOS | Nitric oxide synthase |

| Notch1 | Neurogenic locus notch homolog protein 1 |

| NOX | Nitric oxidase |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor-E2 related factor 2 |

| OS | Oxidative stress |

| OVA | Ovalbumin |

| OXSR1 | Oxidative stress responsive kinase 1 |

| P53 | Protein 53 |

| PARP-1 | Poly[ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 |

| PDGF | Platelet-derived growth factor |

| PEFR | Peak expiratory flow rate |

| PGF2 | Prostaglandin F2 |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase |

| PPBP | Pro-platelet basic protein |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| RA | Retinoic acid |

| RARs | Retinoic acid receptors |

| RXRs | Retinoid X receptors |

| RCTs | Randomised controlled trials |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| Se | Selenium |

| SHS | Secondhand smoke |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin1 |

| SLC-39 | Solute carrier family 39 |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor beta 1 |

| Th | T-helper |

| TLR | Toll-like receptors |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor α |

| TNFRSF11A | TNF receptor superfamily member 11a |

| VA | Vitamin A |

| VC | Vitamin C |

| VD | Vitamin D |

| VE | Vitamin E |

| Zn | Zinc |

References

- Gan, H.; Hou, X.; Zhu, Z.; Xue, M.; Zhang, T.; Huang, Z.; Cheng, Z.J.; Sun, B. Smoking: a leading factor for the death of chronic respiratory diseases derived from Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMC Pulm Med. 2022, 22, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease 2017. 2017. Available online: http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/# (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Aoshiba, K.; Nagai, A. Differences in airway remodeling between asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2004, 27, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doeing, D.C.; Solway, J. Airway smooth muscle in the pathophysiology and treatment of asthma. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 114, 834–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kume, H. Role of airway smooth muscle in inflammation related to asthma and COPD. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021, 1303, 139–172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shimoda, T.; Obase, Y.; Kishikawa, R.; Iwanaga, T. Influence of cigarette smoking on airway inflammation and inhaled corticosteroid treatment in patients with asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2016, 37, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tommola, M.; Ilmarinen, P.; Tuomisto, L.E.; Haanpää, J.; Kankaanranta, T.; Niemelä, O.; Kankaanranta, H. The effect of smoking on lung function: A clinical study of adult-onset asthma. Eur Respir J. 2016, 48, 1298–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korsbæk, N.; Landt, E.M.; Dahl, M. Second-hand smoke exposure associated with risk of respiratory symptoms, asthma, and COPD in 20,421 adults from the General Population. J Asthma Allergy. 2021, 14, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogan, S.; Alonso, T.; Sunday, S.; Tigova, O.; Fernández, E.; López, M.J.; Gallus, S.; Semple, S.; Tzortzi, A.; Boffi, R.; et al. Lung function changes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma exposed to secondhand smoke in outdoor areas. J Asthma. 2021, 58, 1169–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coogan, P.F.; Castro-Webb, N.; Yu, J.; O’Connor, G.T.; Palmer, J.R.; Rosenberg, L. Active and passive smoking and the incidence of asthma in the Black Women’s Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015, 191, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Toorn, M.; Rezayat, D.; Kauffman, H.F.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Gans, R.O.B.; Koëter, G.H.; Choi, A.M.K.; Van Oosterhout, A.J.M.; Slebos, D-J. Lipid-soluble components in cigarette smoke induce mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species in lung epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009, 297, L109–L114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Xiao, W.; Xu, C.; Hu, Y.; Wu, X.; Huang, F.; Lu, X.; Shi, C.; Wu, X. Chemical constituents of tobacco smoke induce the production of interleukin-8 in human bronchial epithelium, 16HBE cells. Tob Induc Dis. 2016, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipollina, C.; Bruno, A.; Fasola, S.; Cristaldi, M.; Patella, B.; Inguanta, R.; Vilasi, A.; Aiello, G.; La Grutta, S.; Torino, C.; et al. Cellular and molecular signatures of oxidative stress in bronchial epithelial cell models injured by cigarette smoke extract. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelak, A.; Ratajczak, A.; Adamiec, A.; Feleszko, W. Tobacco smoke induces and alters immune responses in the lung triggering inflammation, allergy, asthma and other lung diseases: A mechanistic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018, 15, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsharairi, N.A. Scutellaria baicalensis and their natural flavone compounds as potential medicinal drugs for the treatment of nicotine-induced non-small-cell lung cancer and asthma. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonk, J.M.; Scholtens, S.; Postma, D.S.; Moffatt, M.F.; Jarvis, D.; Ramasamy, A.; Wjst, M.; Omenaas, E.R.; Bouzigon, E.; Demenais, F.; et al. Adult onset asthma and interaction between genes and active tobacco smoking: The GABRIEL consortium. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0172716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uh, S-T. ; Park, J-S.; Koo, S-M.; Kim, Y-K.; Kim, K.U.; Kim, M-A.; Shin, S-W.; Son, J-H.; Park, H-W.; Shin, H.D.; et al. Association of genetic variants of NLRP4 with exacerbation of asthma: The effect of smoking. DNA Cell Biol. 2019, 38, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losol, P.; Kim, S.H.; Ahn, S.; Lee, S.; Choi, J-P. ; Kim, Y-H.; Hong, S-J.; Kim, B-S.; Chang, Y-S. Genetic variants in the TLR-related pathway and smoking exposure alter the upper airway microbiota in adult asthmatic patients. Allergy. 2021, 76, 3217–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M-H. ; Chang, H.S.; Lee, J-U.; Shim, J-S.; Park, J-S.; Cho, Y-J.; Park, C-S. Association of genetic variants of oxidative stress responsive kinase 1 (OXSR1) with asthma exacerbations in non-smoking asthmatics. BMC Pulm Med. 2022, 22, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Belcaro, G.; Luzzi, R.; Cesinaro Di Rocco, P.; Cesarone, M.R.; Dugall, M.; Feragalli, B.; Errichi, B.M.; Ippolito, E.; Grossi, M.G.; Hosoi, M.; et al. Pycnogenol® improvements in asthma management. Panminerva Med. 2011, 53, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, N.C.; Spears, M. The influence of smoking on the treatment response in patients with asthma. Curr OpinAllergy Clin Immunol. 2005, 5, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, N.C.; Shepherd, M.; Spears, M.; Chaudhuri, R. Corticosteroid insensitivity in smokers with asthma: clinicalevidence, mechanisms, and management. Treat Respir Med. 2006, 5, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatkin, J.M.; Dullius, C.R. The management of asthmatic smokers. Asthma Res Pract. 2016, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duman, B.; Borekci, S.; Akdeniz, N.; Gazioglu, S.B.; Deniz, G.; Gemicioglu, B. Inhaled corticosteroids’ effects on biomarkers in exhaled breath condensate and blood in patients newly diagnosed with asthma who smoke. J Asthma. 2022, 59, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsharairi, N.A. The effects of dietary supplements on asthma and lung cancer risk in smokers and non-smokers: A review of the literature. Nutrients 2019, 11, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharairi, N.A. Supplements for smoking-related lung diseases. Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharairi, N.A. Dietary antioxidants and lung cancer risk in smokers and non-smokers. Healthcare (Basel). 2022, 10, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santillan, A.A.; Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Colditz, G.A. A meta-analysis of asthma and risk of lung cancer (United States). Cancer Causes Control 2003, 14, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, A.; Bickeböller, H.; McCormack, V.; Brenner, D.R.; Duell, E.J.; Tjønneland, A.; Friis, S.; Muscat, J.E.; Yang, P.; Wichmann, H.E.; et al. Asthma and lung cancer risk: A systematic investigation by the International Lung Cancer Consortium. Carcinogenesis 2012, 33, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.S.; Dockery, D.W.; Neas, L.M.; Schwartz, J.; Coull, B.A.; Raizenne, M.; Speizer, F.E. Low dietary nutrient intakes and respiratory health in adolescents. Chest. 2007, 132, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, W.; Du, J. Association between dietary carotenoid intakes and the risk of asthma in adults: a cross-sectional study of NHANES, 2007-2012. BMJ Open. 2022, 12, e052320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, P.J.K.; Lewis, S.A.; Britton, J.; Fogarty, A. Vitamin E supplements in asthma: a parallel group randomised placebo controlled trial. Thorax. 2004, 59, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaheen, S.O.; Newson, R.B.; Rayman, M.P.; Wong, A. P-L.; Tumilty, M.K.; Phillips, J.M.; Potts, J.F.; Kelly, F.J.; White, P.T.; Burney, P.G.J. Randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled trial of selenium supplementation in adult asthma. Thorax. 2007, 62, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Vaart, H.; Postma, D.S.; Timens, W.; Ten Hacken, N.H.T. Acute effects of cigarette smoke on inflammation and oxidative stress: a review. Thorax. 2004, 59, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, A.S.; Saini, M. Evaluation of systemic antioxidant level and oxidative stress in relation to lifestyle and disease progression in asthmatic patients. J Med Biochem. 2016, 35, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoli, M.L.; Novelli, F.; Costa, F.; Malagrinò, L.; Melosini, L.; Bacci, E.; Cianchetti, S.; Dente, F.L.; Di Franco, A.; Vagaggini, B.; et al. Malondialdehyde in exhaled breath condensate as a marker of oxidative stress in different pulmonary diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2011, 2011, 891752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anes, A.B.; Nasr, H.B.; Fetoui, H.; Bchir, S.; Chahdoura, H.; Yacoub, S.; Garrouch, A.; Benzarti, M.; Tabka, Z.; Chahed, K. Alteration in systemic markers of oxidative and antioxidative status in Tunisian patients with asthma: relationships with clinical severity and airflow limitation. J Asthma. 2016, 53, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, J.C.W.; Leung, H.C.M.; Ho, S.P.; Law, B.K.W.; Lam, W.K.; Tsang, K.W.T.; Ip, M.C.M.; Chan-Yeung, M. Systemic oxidative and antioxidative status in Chinese patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004, 114, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, T.; Kataoka, M.; Hirano, A.; Iio, K.; Tanimoto, Y.; Kanehiro, A.; Okada, C.; Soda, R.; Takahashi, K.; Tanimoto, M. Inflammatory markers in exhaled breath condensate from patients with asthma. Respirology. 2008, 13, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillas, G.; Kostikas, K.; Mantzouranis, K.; Bessa, V.; Kontogianni, K.; Papadaki, G.; Papiris, S.; Alchanatis, M.; Loukides, S.; Bakakos, P. Exhaled nitric oxide and exhaled breath condensate pH as predictors of sputum cell counts in optimally treated asthmatic smokers. Respirology. 2011, 16, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michils, A.; Louis, R.; Peché, R.; Baldassarre, S.; Van Muylem, A. Exhaled nitric oxide as a marker of asthma control in smoking patients. Eur Respir J. 2009, 33, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emma, R.; Bansal, A.T.; Kolmert, J.; Wheelock, C.E.; Dahlen, S-E. ; Loza, M.J.; De Meulder, B.; Lefaudeux, D.; Auffray, C.; Dahlen, B.; et al. Enhanced oxidative stress in smoking and ex-smoking severe asthma in the U-BIOPRED cohort. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0203874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telenga, E.D.; Kerstjens, H.A.M.; Ten Hacken, N.H.T.; Postma, D.S.; van den Berge, M. Inflammation and corticosteroid responsiveness in ex-, current- and never-smoking asthmatics. BMC Pulm Med. 2013, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Pavlidis, S.; Kwong, F.N.K.; Hoda, U.; Rossios, C.; Sun, K.; Loza, M.; Baribaud, F.; Chanez, P.; Fowler, S.J.; et al. Sputum proteomics and airway cell transcripts of current and ex-smokers with severe asthma in U-BIOPRED: an exploratory analysis. Eur Respir J. 2018, 51, 1702173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, N.C.; Chaudhuri, R.; Heaney, L.G.; Bucknall, C.; Niven, R.M.; Brightling, C.E.; Menzies-Gow, A.N.; Mansur, A.H.; McSharry, C. Clinical outcomes and inflammatory biomarkers in current smokers and exsmokers with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013, 131, 1008–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Wu, F. Association between fractional exhaled nitric oxide, sputum induction and peripheral blood eosinophil in uncontrolled asthma. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2018, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlidis, S.; Takahashi, K.; Kwong, F.N.K.; Xie, J.; Hoda, U.; Sun, K.; Elyasigomari, V.; Agapow, P.; Loza, M.; Baribaud, F.; et al. “T2-high” in severe asthma related to blood eosinophil, exhaled nitric oxide and serum periostin. Eur Respir J. 2019, 53, 1800938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, R.C.; Acharya, P.R.; Noushad, T.H.; Anand, R.; Acharya, V.K.; Sahu, K.R. A study of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in bronchial asthma. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2009, 51, 213–216. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C-C. ; Wang, C-H.; Wu, P-W.; He, J-R.; Huang, C-C.; Chang, P-H.; Fu, C-H.; Lee, T-J. Increased nasal matrix metalloproteinase-1 and -9 expression in smokers with chronic rhinosinusitis and asthma. Scientific Reports. 2019, 9, 15357.

- Chaudhuri, R.; McSharry, C.; Brady, J.; Donnelly, I.; Grierson, C.; McGuinness, S.; Jolly, L.; Weir, C.J.; Messow, C.M.; Spears, M.; et al. Sputum matrix metalloproteinase-12 in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma: relationship to disease severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012, 129, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C-C. ; Wang, C-H.; Fu, C-H.; Huang, C-C.; Chang, P-H.; Chen, Y-W.; Wu, C-C.; Wu, P-W.; Lee, T-J. Association between cigarette smoking and interleukin-17A expression in nasal tissues of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis and asthma. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016, 95, e5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, G.W.; MacLeod, K.J.; Thomson, L.; Little, S.A.; McSharry, C.; Thomson, N.C. Smoking and airway inflammation in patients with mild asthma. Chest. 2001, 120, 1917–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossios, C.; Pavlidis, S.; Hoda, U.; Kuo, C-H. ; Wiegman, C.; Russell, K.; Sun, K.; Loza, M.J.; Baribaud, F.; Durham, A.L.; et al. Sputum transcriptomics reveal upregulation of IL-1 receptor family members in patients with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018, 141, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ham, J.; Kim, J.; Sohn, K-H. ; Park, I-W.; Choi, B-W.; Chung, D.H.; Cho, S-H.; Kang, H.R.; Jung, J-W.; Kim, H.Y. Cigarette smoke aggravates asthma by inducing memory-like type 3 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Commun. 2022, 4, 13–3852. [Google Scholar]

- Krisiukeniene, A.; Babusyte, A.; Stravinskaite, K.; Lotvall, J.; Sakalauskas, R.; Sitkauskiene, B. Smoking affects eotaxin levels in asthma patients. J Asthma. 2009, 46, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveci, F.; Ilhan, N.; Turgut, T.; Akpolat, N.; Kirkil, G.; Muz, M.H. Glutathione and nitrite in induced sputum from patients with stable and acute asthma compared with controls. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004, 93, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, A.; Chhabra, S.K.; Masood, A.; Raj, H.G. Increased oxidative stress and altered levels of antioxidants in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003, 111, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamitava, L.; Cazzoletti, L.; Ferrari, M.; Garcia-Larsen, V.; Jalil, A.; Degan, P.; Fois, A.G.; Zinellu, E.; Fois, S.S.; Pasini, A.M.F.; et al. Biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation in chronic airway diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerpin, E.; Ferreira, D.S.; Weyler, J.; Schlunnsen, V.; Jogi, R.; Semjen, C.R.; Gislasson, T.; Demoly, P.; Heinrich, J.; Nowak, D.; et al. Bronchodilator response and lung function decline: Associations with exhaled nitric oxide with regard to sex and smoking status. World Allergy Organ J. 2021, 14, 100544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinovschi, A.; Backer, V.; Harving, H.; Porsbjerg, C. The value of exhaled nitric oxide to identify asthma in smoking patients with asthma-like symptoms. Respir Med. 2012, 106, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannelli, J.; Chérot-Kornobis, N.; Hulo, S.; Ciuchete, A.; Clément, G.; Amouyel, P.; Matran, R.; Dauchet, L. Both exhaled nitric oxide and blood eosinophil count were associated with mild allergic asthma only in non-smokers. Clin Exp Allergy. 2016, 46, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostikas, K.; Papaioannou, A.I.; Tanou, K.; Giouleka, P.; Koutsokera, A.; Minas, M.; Papiris, S.; Gourgoulianis, K.I.; Taylor, D.R.; et al. Exhaled NO and exhaled breath condensate pH in the evaluation of asthma control. Respiratory Medicine. 2011, 105, 526e532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, N.C.; Chaudhuri, R.; Spears, M.; Haughney, J.; McSharry, C. Serum periostin in smokers and never smokers with asthma. Respir Med. 2015, 109, 708–7015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cianchetti, S.; Cardini, C.; Puxeddu, I.; Latorre, M.; Bartoli, M.L.; Bradicich, M.; Dente, F.; Bacci, E.; Celi, A.; Paggiaro, P. Distinct profile of inflammatory and remodelling biomarkers in sputum of severe asthmatic patients with or without persistent airway obstruction. World Allergy Organ J. 2019, 12, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildiz, H.; Alp, H.H.; Sünnetçioğlu, A.; Ekin, S.; Çilingir, B.M. Evaluation serum levels of YKL-40, Periostin, and some inflammatory cytokines together with IL-37, a new anti-inflammatory cytokine, in patients with stable and exacerbated asthma. Heart Lung. 2021, 50, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovina, N.; Dima, E.; Gerassimou, C.; Kollintza, A.; Gratziou, C.; Roussos, C. IL-18 in induced sputum and airway hyperresponsiveness in mild asthmatics: effect of smoking. Respir Med. 2009, 103, 1919–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zietkowski, Z.; Tomasiak-Lozowska, M.M.; Skiepko, R.; Zietkowska, E.; Bodzenta-Lukaszyk, A. Eotaxin-1 in exhaled breath condensate of stable and unstable asthma patients. Respir Res. 2010, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Ma, L.; Wei, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, Q.; Chen, M.; Jiang, M.; Luo, M.; Wu, J.; Mai, L.; et al. Smoking status modifies the relationship between Th2 biomarkers and small airway obstruction in asthma. Can Respir J. 2021, 2021, 1918518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikus, M.S.; Kolmert, J.; Andersson, L.I.; Östling, J.; Knowles, R.G.; Gómez, C.; Ericsson, M.; Thörngren, J-O. ; Khoonsari, P.E.; Dahlén, B.; et al. Plasma proteins elevated in severe asthma despite oral steroid use and unrelated to Type-2 inflammation. Eur Respir J. 2022, 59, 2100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wu, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Cao, L.; Liu, Y.; Dong, L. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells: A novel biomarker of eosinophilic airway inflammation in patients with mild to moderate asthma. Respir Med. 2015, 109, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvani, A.; Tahghighi, F.; Nadooshan, H.H. Evaluation of correlation between airway and serum inflammatory markers in asthmatic patients. Lung India. 2012, 29, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoda, T.; Obase, Y.; Kishikawa, R.; Iwanaga, T. Serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein can be an airway inflammation predictor in bronchial asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2015, 36, e23–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timoneda, J.; Rodríguez-Fernández, L.; Zaragozá, R.; Marín, M.P.; Cabezuelo, M.T.; Torres, L.; Viña, J.R.; Barber, T. Vitamin A deficiency and the lung. Nutrients. 2018, 10, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defnet, A.E.; Shah, S.D.; Huang, W.; Shapiro, P.; Deshpande, D.A.; Kane, M.A. Dysregulated retinoic acid signaling in airway smooth muscle cells in asthma. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e22016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druilhe, A.; Zahm, J-M. ; Benayoun, L.; El Mehdi, D.; Grandsaigne, M.; Dombret, M-C.; Mosnier, I.; Feger, B.; Depondt, J.; Aubier, M.; et al. Epithelium expression and function of retinoid receptors in asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008, 38, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.M.; Lee, Y.H.; Park, A-M. ; Suzuki, Y.J. Retinoic acid inhibits airway smooth muscle cell migration. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006, 34, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaghan, P.J.; Rybakovsky, E.; Ferrick, B.; Thomas, S.; Mullin, J.M. Retinoic acid improves baseline barrier function and attenuates TNF-α-induced barrier leak in human bronchial epithelial cell culture model, 16HBE 14o. PLoS One. 2020, 15, e0242536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhong, W.; Xia, Z. All-trans retinoic acid attenuates airway inflammation by inhibiting Th2 and Th17 response in experimental allergic asthma. BMC Immunol. 2013, 14, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamura, K.; Nasuhara, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Betsuyaku, T.; Tanino, Y.; Kinoshita, I.; Yamaguchi, E.; Matsukura, S.; Schleimer, R.P.; Nishimura, M. Retinoic acid inhibits interleukin-4-induced eotaxin production in a human bronchial epithelial cell line. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004, 286, L777–L785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurie, J.M.; Lotan, R.; Lee, J.J.; Lee, J.S.; Morice, R.C.; Liu, D.D.; Xu, X-C. ; Khuri, F.R.; Ro, J.Y.; Hittelman, W.N.; Walsh, G.L.; et al. Treatment of former smokers with 9-cis-retinoic acid reverses loss of retinoic acid receptorbeta expression in the bronchial epithelium: results from a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003, 95, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenberger, M.; Heimbeck, I.; Möller, W.; Mamidi, S.; Kaßner, G.; Pukelsheim, K.; Wjst, M.; Neiswirth, M.; Kroneberg, P.; Lomas, D.; et al. Inhaled all-trans retinoic acid in an individual with severe emphysema. European Respiratory J. 2009, 34, 1487–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.K.; Prasad, P.; Lokesh, V.; Shang, X.; Shin, J.; Keum, Y-S. ; Lee, J-H. Carotenoids: Dietary sources, extraction, encapsulation, bioavailability, and health benefits-A review of recent advancements. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022, 11, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.S.; Kim, S.R.; Kim, J.O.; Lee, Y.C. The roles of phytochemicals in bronchial asthma. Molecules. 2010, 15, 6810–6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, A.; Willhite, C.A.; Liebler, D.C. Interactions of beta-carotene and cigarette smoke in human bronchial epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis. 2001, 22, 1173–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, P.; Liu, C.; Hu, K-Q. ; Krinsky, N.I.; Russell, R.M.; Wang, X-D. Beta-carotene and beta-apo-14’-carotenoic acid prevent the reduction of retinoic acid receptor beta in benzo[a]pyrene-treated normal human bronchial epithelial cells. J Nutr. 2004, 134, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazlewood, L.C.; Wood, L.G.; Hansbro, P.M.; Foster, P.S. Dietary lycopene supplementation suppresses Th2 responses and lung eosinophilia in a mouse model of allergic asthma. J Nutr Biochem. 2011, 22, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, F.; Wang, X-D. Enzymatic metabolites of lycopene induce Nrf2-mediated expression of phase II detoxifying/antioxidant enzymes in human bronchial epithelial cells. Int J Cancer. 2008, 123, 1262–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaverelli, R.A.; Hu, K.-Q.; Liu, C.; Lim, J.Y.; Daniels, M.S.; Xia, H.; Mein, J.; von Lintig, J.; Wang, X.-D. β-Cryptoxanthin attenuates cigarette-smoke-induced lung lesions in the absence of carotenoid cleavage enzymes (BCO1/BCO2) in mice. Molecules. 2023, 28, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bronson, R.T.; Russell, R.M.; Wang, X.-D. β-Cryptoxanthin supplementation prevents cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation, oxidative damage, and squamous metaplasia in ferrets. Cancer Prev. Res. 2011, 4, 1255–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Britton, J.R.; Leonardi-Bee, J.A. Association between antioxidant vitamins and asthma outcome measures: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2009, 64, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tecklenburg, S.L.; Mickleborough, T.D.; Fly, A.D.; Bai, Y.; Stager, J.M. Ascorbic acid supplementation attenuates exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in patients with asthma. Respir Med. 2007, 101, 1770–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H-H. ; Chen, C-S.; Lin, J-Y. High dose vitamin C supplementation increases the Th1/Th2 cytokine secretion ratio, but decreases eosinophilic infiltration in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of ovalbumin-sensitized and challenged mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2009, 57, 10471–10476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Cromie, M.M.; Cai, Q.; Lv, T.; Singh, K.; Gao, W. Curcumin and vitamin E protect against adverse effects of benzo[a]pyrene in lung epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e92992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoskins, A.; Roberts, J.L.; Milne, G.; Choi, L.; Dworski, R. Natural-source d-α-tocopheryl acetate inhibits oxidant stress and modulates atopic asthma in humans in vivo. Allergy. 2012, 67, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiser, J.; Alexis, N.E.; Jiang, Q.; Wu, W.; Robinette, C.; Roubey, R.; Peden, D.B. In vivo gamma-tocopherol supplementation decreases systemic oxidative stress and cytokine responses of human monocytes in normal and asthmatic subjects. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008, 45, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, M.L.; Wagner, J.G.; Kala, A.; Mills, K.; Wells, H.B.; Alexis, N.E.; Lay, J.C.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, H.; et al. Vitamin E, γ-tocopherol, reduces airway neutrophil recruitment after inhaled endotoxin challenge in rats and in healthy volunteers. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013, 60, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbank, A.J.; Duran, C.G.; Pan, Y.; Burns, P.; Jones, S.; Jiang, Q.; Yang, C.; Jenkins, S.; Wells, H.; Alexis, N.; et al. Gamma tocopherol-enriched supplement reduces sputum eosinophilia and endotoxin-induced sputum neutrophilia in volunteers with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018, 141, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talati, M.; Meyrick, B.; Peebles Jr, R.S.; Davies, S.S.; Dworski, R.; Mernaugh, R.; Mitchell, D.; Boothby, M.; Roberts, L.J.; Sheller, J.R. Oxidant stress modulates murine allergic airway responses. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006, 40, 1210–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoc, Q.L.; Bich, T.C.T.; Kim, S-H. ; Park, H-S.; Shin, Y.S. Administration of vitamin E attenuates airway inflammation through restoration of Nrf2 in a mouse model of asthma. J Cell Mol Med. 2021, 25, 6721–6732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, L.; Chen, H.; Chang, Q.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Wei, C.; Li, R.; Kwan, J.K.C.; Yeung, K.L.; et al. Application of vitamin E to antagonize SWCNTs-induced exacerbation of allergic asthma. Sci Rep. 2014, 4, 4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabalirajan, U.; Aich, J.; Leishangthem, G.D.; Sharma, S.K.; Dinda, A.K.; Ghosh, B. Effects of vitamin E on mitochondrial dysfunction and asthma features in an experimental allergic murine model. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009, 107, 1285–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCary, C.A.; Abdala-Valencia, H.; Berdnikovs, S.; Cook-Mills, J.M. Supplemental and highly elevated tocopherol doses differentially regulate allergic inflammation: reversibility of α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol’s effects. J Immunol. 2011, 186, 3674–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, S.C.; Agrawal, D.K. Vitamin D and bronchial asthma: An overview of data from the past 5 years. Clin Ther. 2017, 39, 917–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeffer, P.E.; Lu, H.; Mann, E.H.; Chen, Y-H. ; Ho, T-R.; Cousins, D.J.; Corrigan, C.; Kelly, F.J.; Mudway, I.S.; Hawrylowicz, C.M. Effects of vitamin D on inflammatory and oxidative stress responses of human bronchial epithelial cells exposed to particulate matter. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0200040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Martínez, E.; López-Vancell, M.R.; Fernández de Córdova-Aguirre, J.C.; Rojas-Serrano, J.; Chavarría, A.; Velasco-Medina, A.; Velázquez-Sámano, G. Reduction of respiratory infections in asthma patients supplemented with vitamin D is related to increased serum IL-10 and IFNγ levels and cathelicidin expression. Cytokine. 2018, 108, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam-Bonci, T-I. ; Bonci, E-A.; Pârvu, A-E.; Herdean, A-I.; Moț, A.; Taulescu, M.; Ungur, A.; Pop, R-M.; Bocșan, C.; Irimie, A. Vitamin D supplementation: Oxidative stress modulation in a mouse model of ovalbumin-induced acute asthmatic airway inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 7089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Peng, M.; Tong, J.; Zhong, X.; Xian, J.; Zhong, L.; Deng, J.; Huang, Y. Vitamin D ameliorates asthma-induced lung injury by regulating HIF-1α/Notch1 signaling during autophagy. Food Sci Nutr. 2022, 10, 2773–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, K.D.; Hall, S.C.; Agrawal, D.K. Vitamin D supplementation reduces induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in allergen sensitized and challenged mice. PLoS One. 2016, 11, e0149180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorman, S.; Weeden, C.E.; Tan, D.H.W.; Scott, N.M.; Hart, J.; Foong, R.E.; Mok, D.; Stephens, N.; Zosky, G.; Hart, P.H. Reversible control by vitamin D of granulocytes and bacteria in the lungs of mice: an ovalbumin-induced model of allergic airway disease. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e67823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taher, Y.A.; van Esch, B.C.A.M.; Hofman, G.A.; Henricks, P.A.J.; van Oosterhout, A.J.M. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 potentiates the beneficial effects of allergen immunotherapy in a mouse model of allergic asthma: role for IL-10 and TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2008, 180, 5211–5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, T.; Gupta, G.K.; Agrawal, D.K. Vitamin D supplementation reduces airway hyperresponsiveness and allergic airway inflammation in a murine model. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013, 43, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, N.; Wang, T.; Dai, B.; Shang, Y. Vitamin D reduces inflammatory response in asthmatic mice through HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2018, 17, 2915–2920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ekmekci, O.P.; Donma, O.; Sardoğan, E.; Yildirim, N.; Uysal, O.; Demirel, H.; Demir, T. Iron, nitric oxide, and myeloperoxidase in asthmatic patients. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2004, 69, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narula, M.K.; Ahuja, G.K.; Whig, J.; Narang, A.P.S.; Soni, R.K. Status of lipid peroxidation and plasma iron level in bronchial asthmatic patients. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007, 51, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Han, F.; Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Bai, Z. Interleukin-6 promotes ferroptosis in bronchial epithelial cells by inducing reactive oxygen species-dependent lipid peroxidation and disrupting iron homeostasis. Bioengineered. 2021, 12, 5279–5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuribayashi, K.; Iida, S-I. ; Nakajima, Y.; Funaguchi, N.; Tabata, C.; Fukuoka, K.; Fujimori, Y.; Ihaku, D.; Nakano, T. Suppression of heme oxygenase-1 activity reduces airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation in a mouse model of asthma. J Asthma. 2015, 52, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghio, A.J.; Hilborn, E.D. Indices of iron homeostasis correlate with airway obstruction in an NHANES III cohort. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017, 12, 2075–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghio, A.J.; Hilborn, E.D.; Stonehuerner, J.G.; Dailey, L.A.; Carter, J.D.; Richards, J.H.; Crissman, K.M.; Foronjy, R.F.; Uyeminami, D.L.; Pinkerton, K.E. Particulate matter in cigarette smoke alters iron homeostasis to produce a biological effect. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008, 178, 1130–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, D. Mineral micronutrients in asthma. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, B.; Cormier, S.A. Copper oxide nanoparticles induce oxidative stress and cytotoxicity in airway epithelial cells. Toxicol In Vitro. 2009, 23, 1365–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J-W. ; Lee, I-C.; Shin, N-R.; Jeon, C-M.; Kwon, O-K.; Ko, J-W.; Kim, J-C.; Oh, S-R.; Shin, I-S.; Ahn, K-S. Copper oxide nanoparticles aggravate airway inflammation and mucus production in asthmatic mice via MAPK signaling. Nanotoxicology. 2016, 10, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagdic, A.; Sener, O.; Bulucu, F.; Karadurmus, N.; Özel, H.E.; Yamanel, L.; Tasci, C.; Naharci, I.; Ocal, R. ; Aydin Oxidative stress status and plasma trace elements in patients with asthma or allergic rhinitis. Allergol Immunopathol(Madr). 2011, 39, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C-H. ; Liu, P-J.; Hsia, S.; Chuang, C-J.; Chen, P-C. Role of certain trace minerals in oxidative stress, inflammation, CD4/CD8 lymphocyte ratios and lung function in asthmatic patients. Ann Clin Biochem. 2011, 48, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Wu, L.; Shi, W. Association between trace elements levels and asthma susceptibility. Respir Med. 2018, 145, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.; Cantin, A.M.; Beaulieu, C.; Cloutier, A.; Larivée. P. Zinc chelators inhibit eotaxin, RANTES, and MCP-1 production in stimulated human airway epithelium and fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003, 285, L719–L729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.; Murgia, C.; Leong, M.; Tan, L-W. ; Perozzi, G.; Knight, D.; Ruffin, R.; Zalewski, P. Anti-inflammatory effects of zinc and alterations in zinc transporter mRNA in mouse models of allergic inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007, 292, L577–L584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xin, Y.; Tang, Y.; Shao, G. Zinc suppressed the airway inflammation in asthmatic rats: effects of zinc on generation of eotaxin, MCP-1, IL-8, IL-4, and IFN-γ. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2012, 150, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Design | Study population | Antioxidants | Main findings | Ref. |

| Cross-sectional | Total subjects = 2112 12th grade US students Smokers = 515 |

VC, VE (diet) | Low dietary VC intake (<110 mg/day) was associated with FEV1 decline and respiratory symptoms in smokers with BA VE intake was not associated with BA |

[30] |

| Cross-sectional | Total subjects = 13,039 US adults (20-80 yrs) Current asthma=1784; non-current asthma= 11,255 Nonsmokers= 7106; current smokers= 3304; former smokers= 2624 |

Total carotenoids (diet and supplement) | High intake of carotenoids (≥165.59 μg/kg/day) was associated with reduced BA risk in nonsmokers (OR= 0.63, 95% CI = 0.42 to 0.93), current smokers (OR= 0.54, 95% CI = 0.36 to 0.83) and former smokers (OR= 0.64, 95% CI = 0.42 to 0.97) | [31] |

| RDBPC | Total subjects = 72 UK nonsmoking asthmatic (18-60 yrs) | VE (supplement) 500 mg VE capsules (D-α-tocopherol) in soya bean oil or matched placebo (capsules, gelatine base) for 6 weeks |

VE had no beneficial effects on BA | [32] |

| RDBPC | Total subjects = 197 UK smoking and nonsmoking asthmatic (18-54 yrs) |

Se (supplement) 100 μg/day high-Se yeast preparation or matched placebo (yeast only) for 24 weeks |

Plasma Se was increased by 48% in the Se group. However, no significant improvement in QoL score was observed in the Se group compared with placebo | [33] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).