Submitted:

06 May 2023

Posted:

08 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phytochemical screening

2.2. Extraction yields

2.3. Phytochemical constituents of three cassava varieties

| Cassava varieties | Flavonoids (μgEQ/100mg) | Polyphenols (μgEAG/100mg) | Tannins (mgEAG/g extract) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BEN | 110,96 ± 1,18a | 52,59 ± 7,56b | 0,35 ± 0,07b |

| MJ | 129,36 ± 9,22a | 32,62 ± 8,70c | 0,37 ± 0,04b |

| RB | 125,20 ± 2,77a | 65,14 ± 4,74a | 0,54 ± 0,03a |

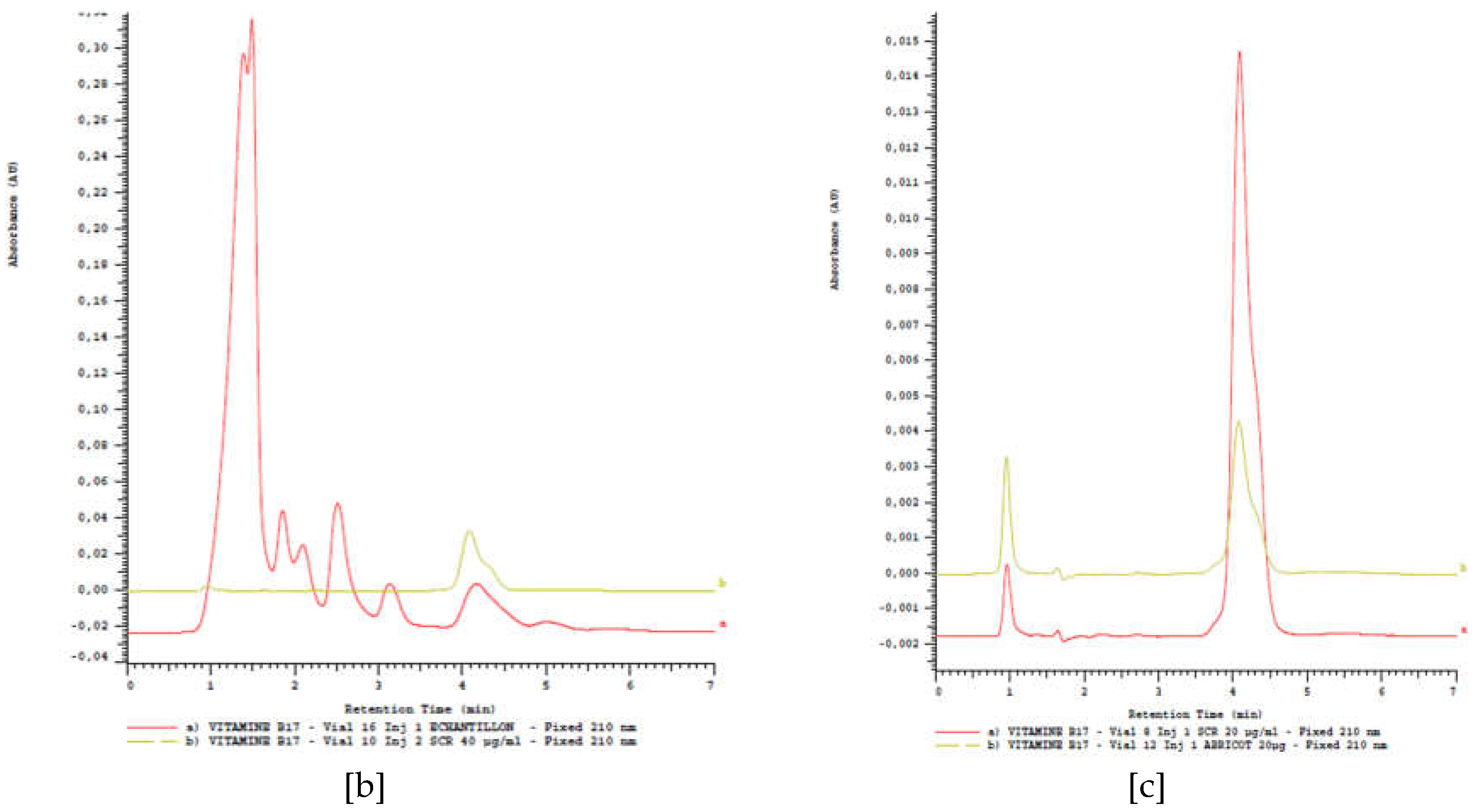

2.4. Variation of the amygdalin content in Cassava varieties organs

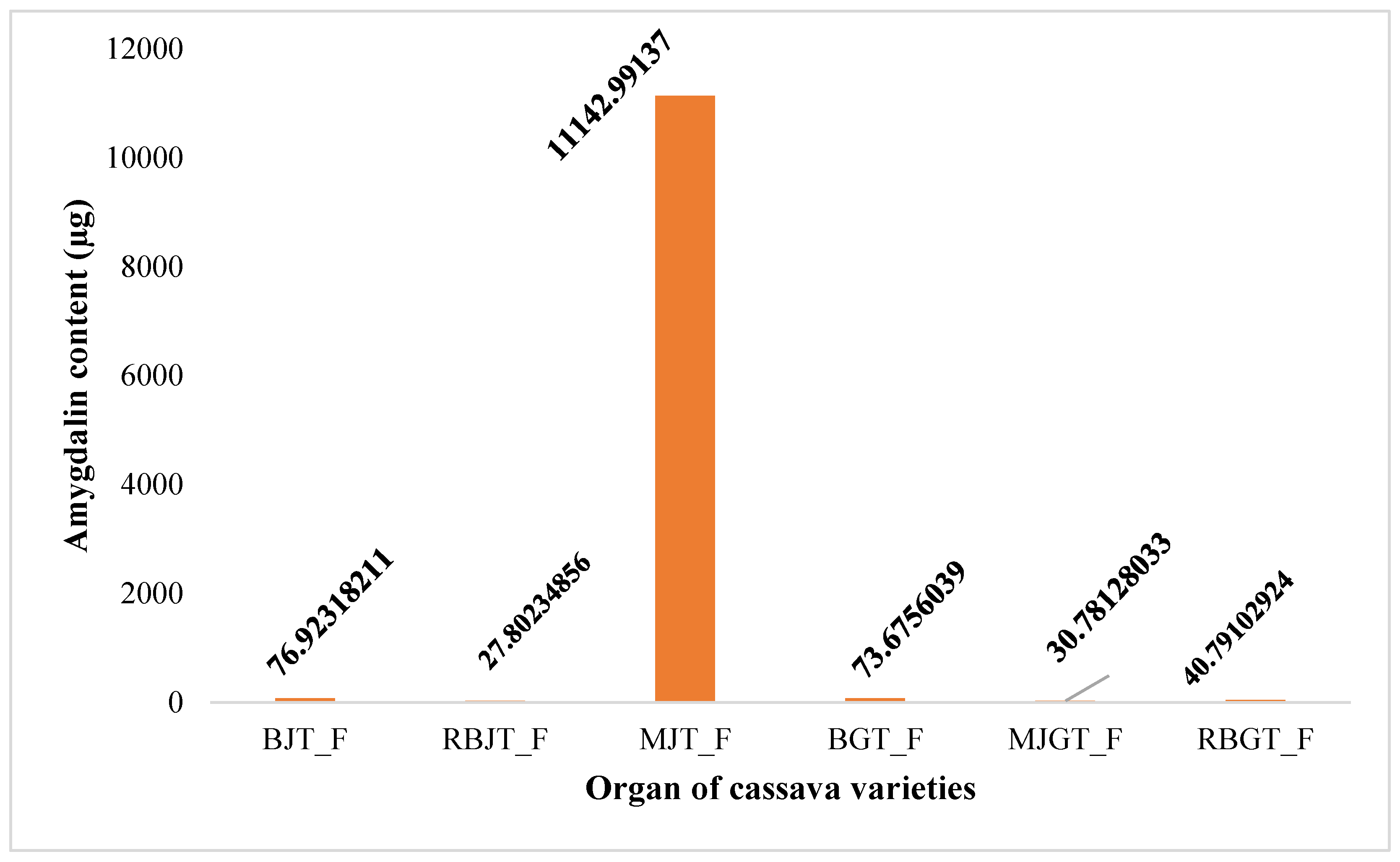

2.4.1. Amygdalin content in cassava stem organs

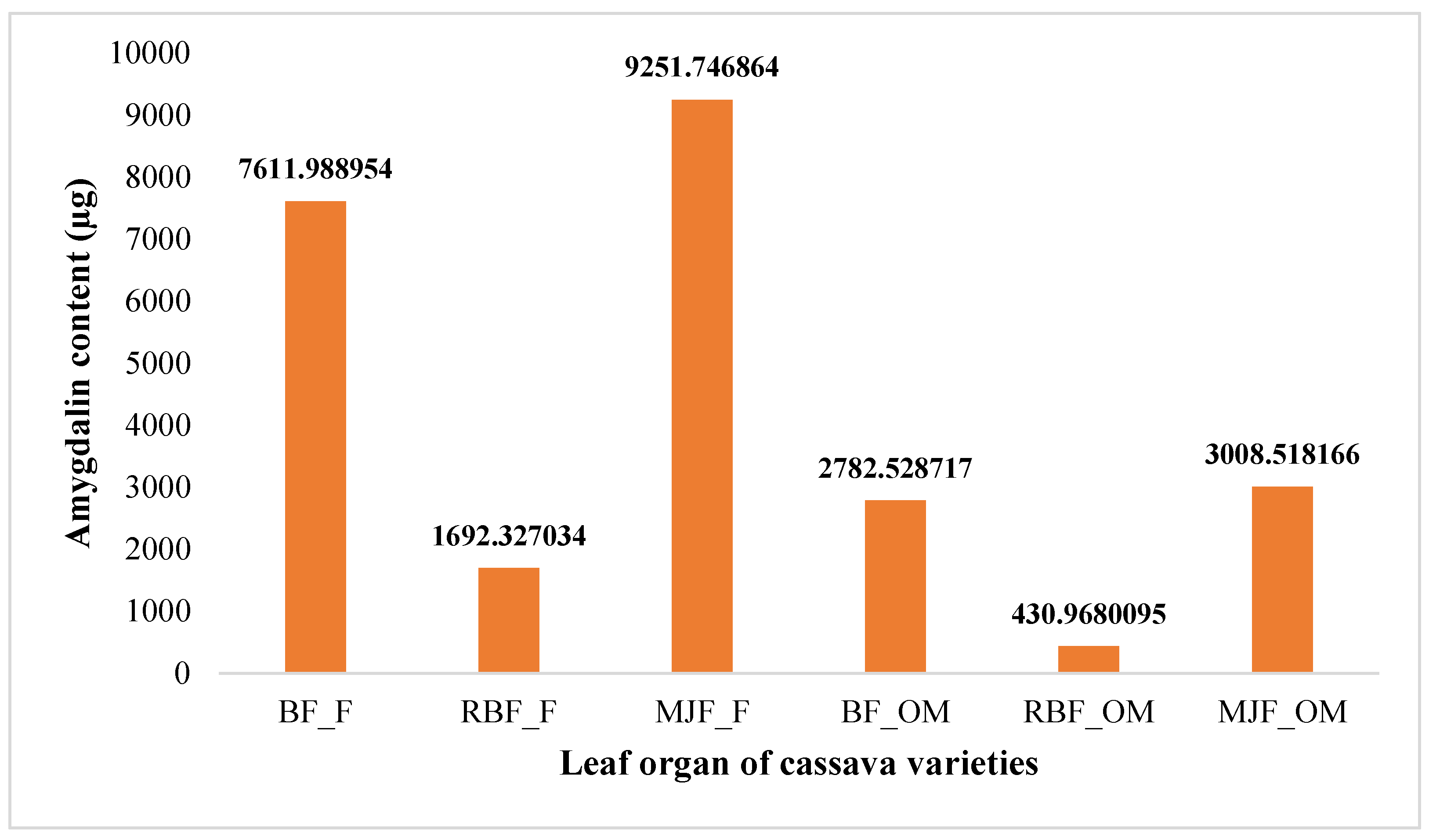

2.4.2. Amygdalin content in cassava leaves

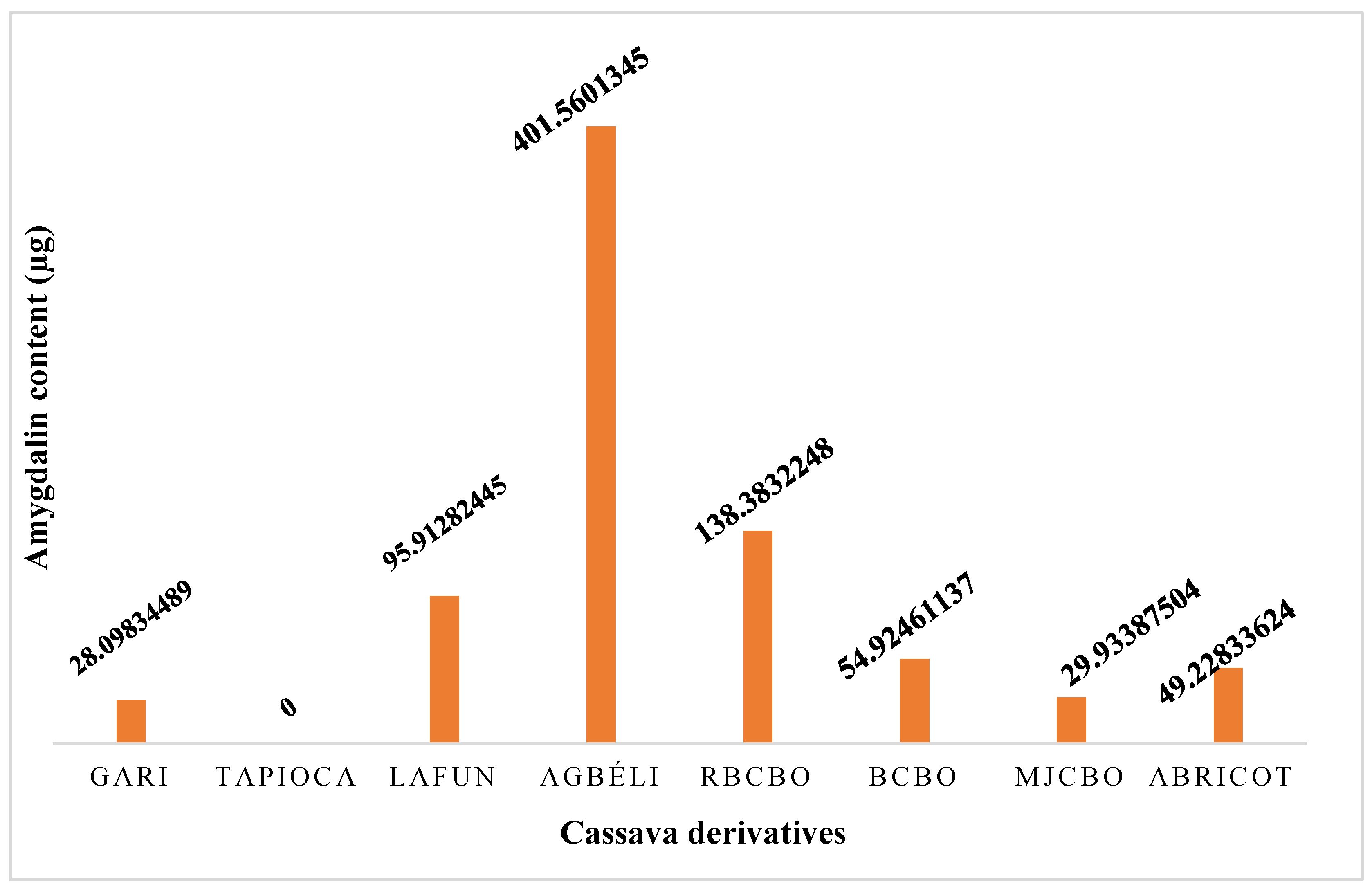

2.4.3. Amygdalin content in cassava derivatives

2.5. Antioxidant activity

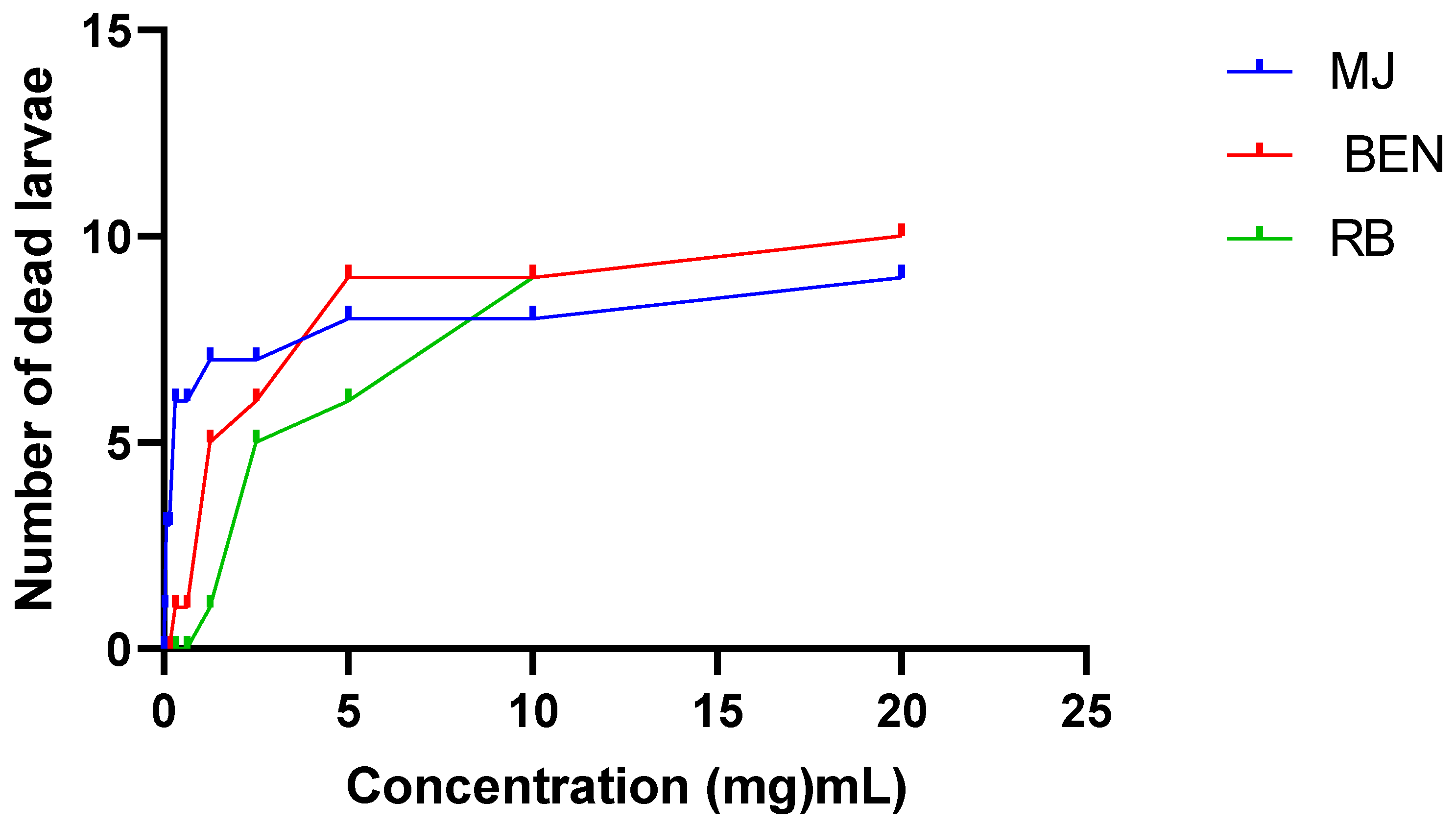

2.6. Larval cytotoxicity of amygdalin extracted of cassava varieties

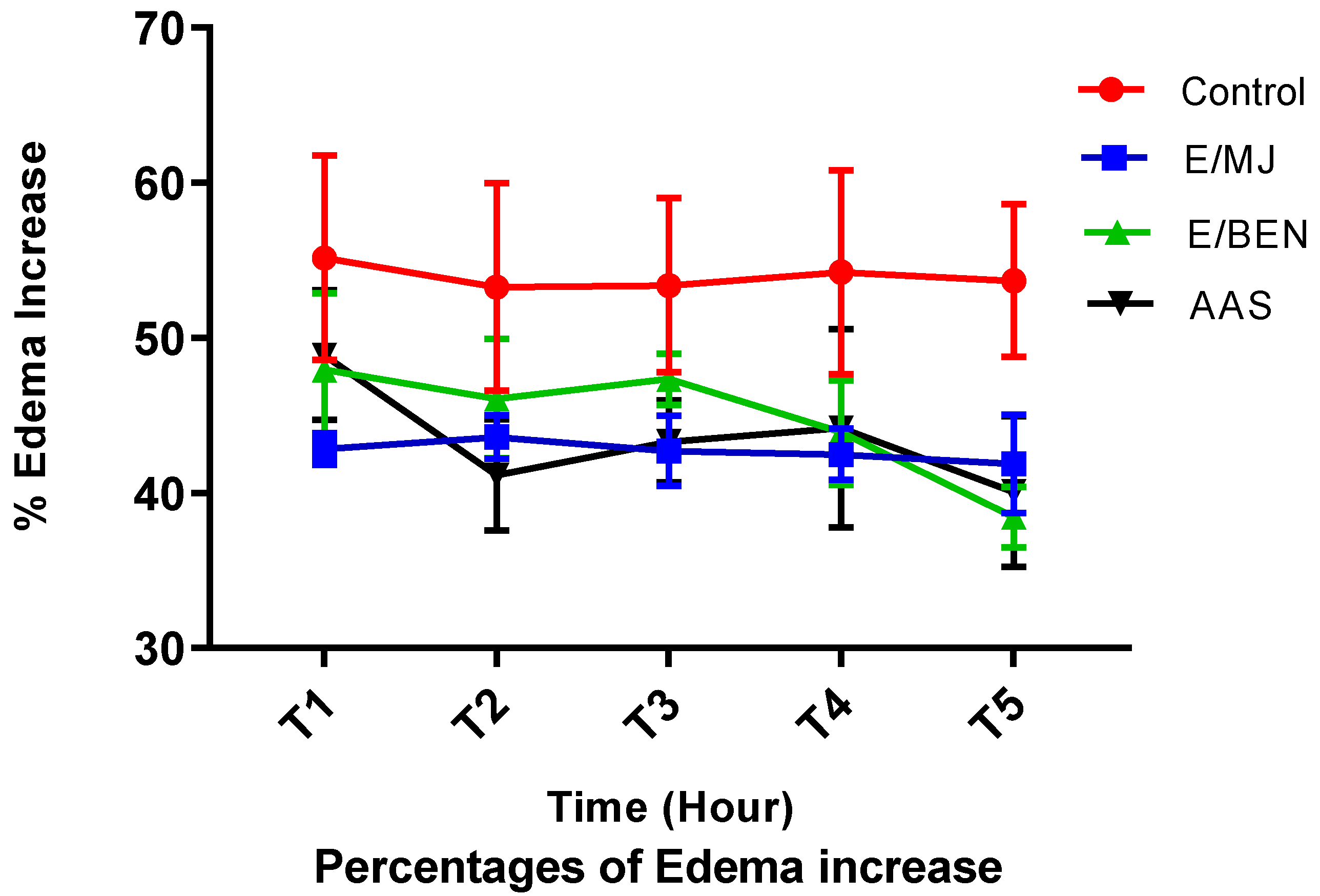

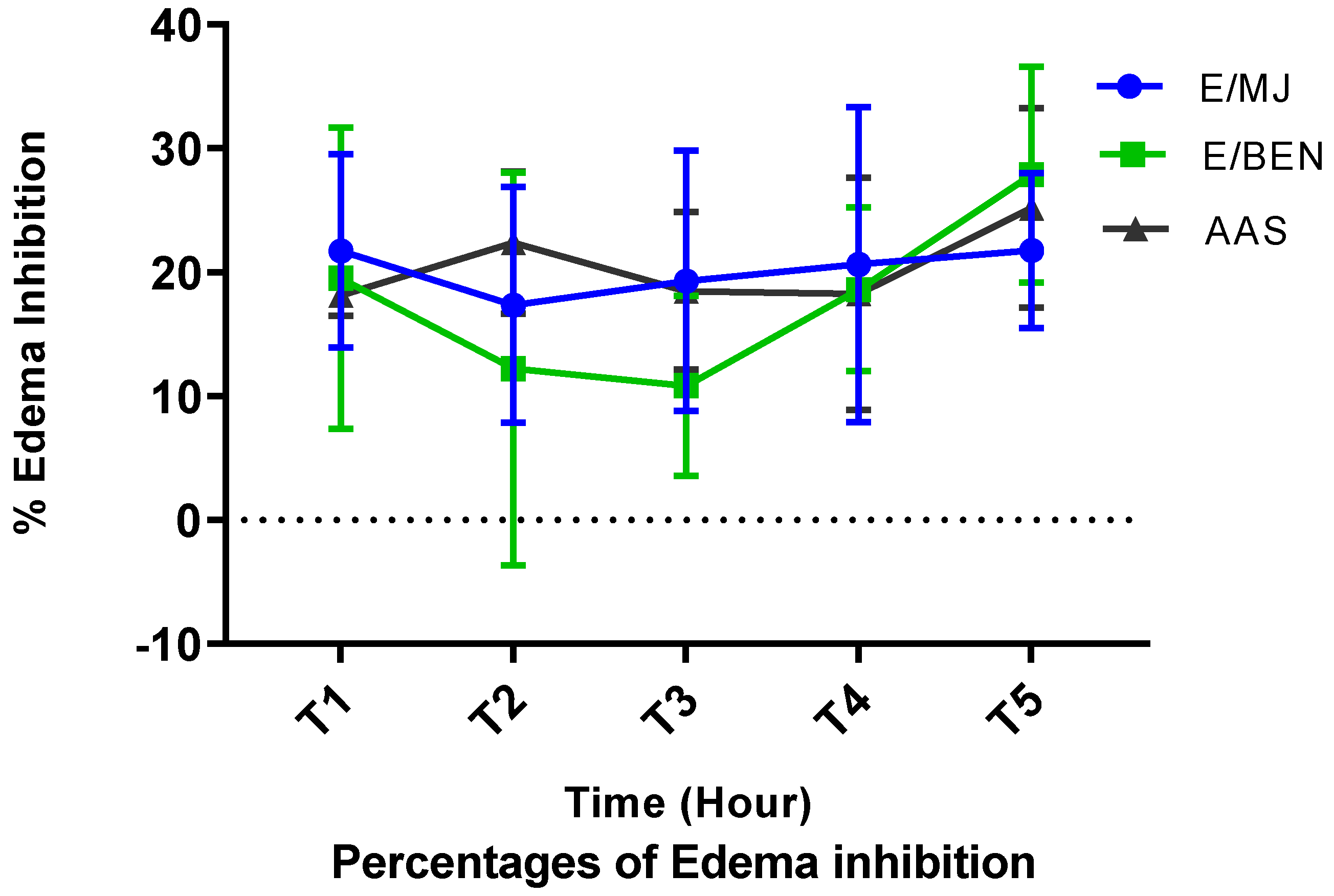

2.7. Anti-inflammatoiry activity of cassava leaf extracts

2.8. Anticancer activity of amygdalin extracts from cassava variety BEN

2.8.1. Biochemical analysis

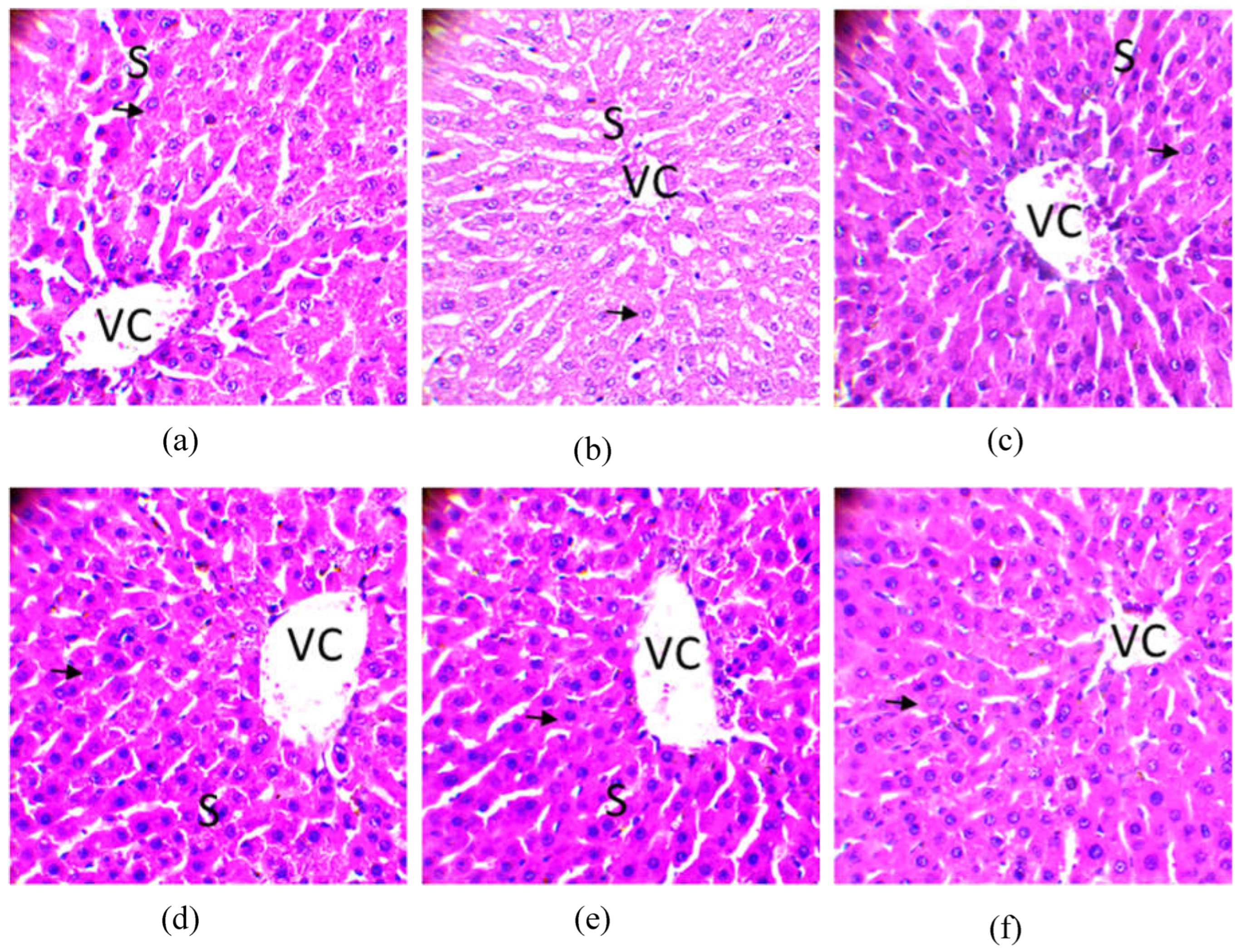

2.8.2. Histological analysis

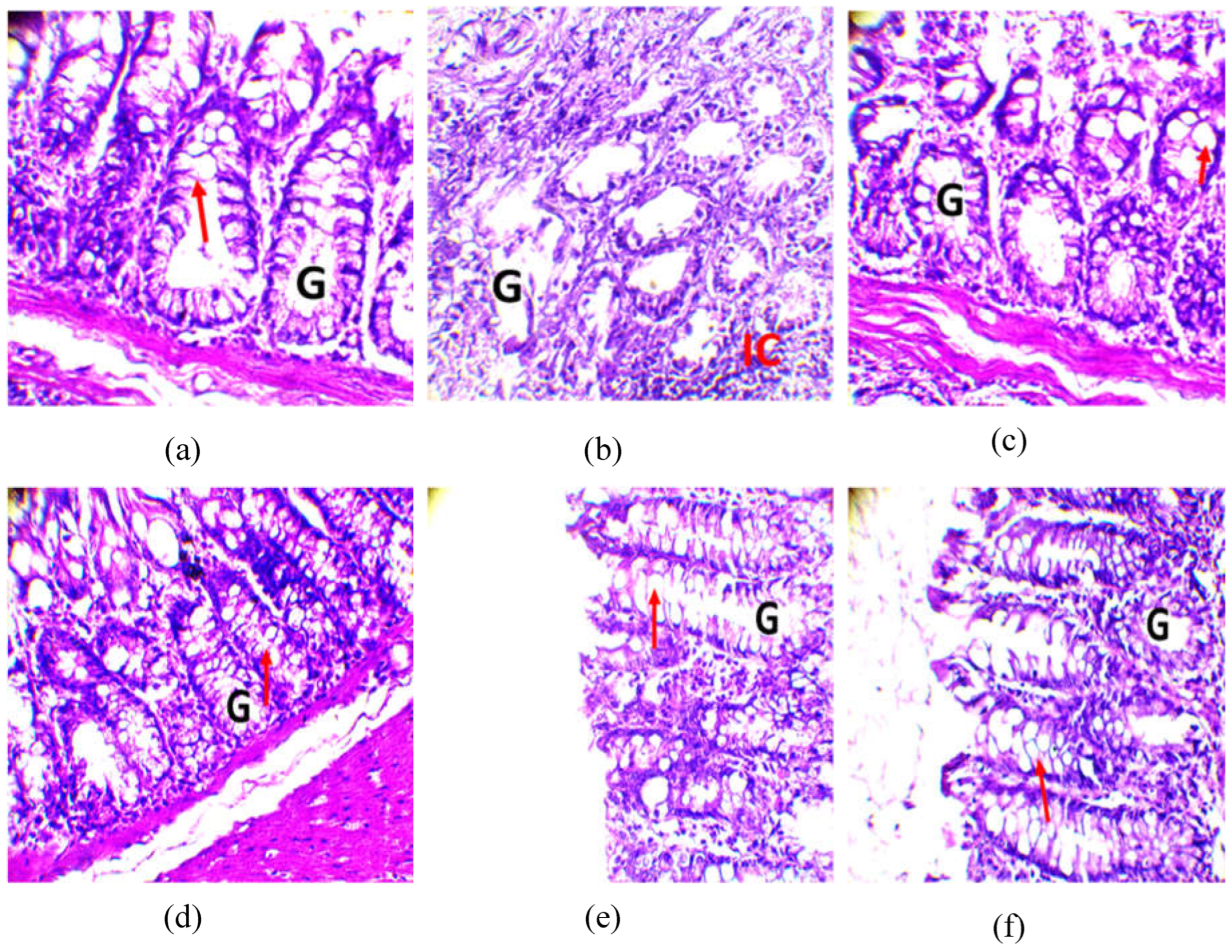

2.8.1. Observation of the colon

2.8.2. Observation on the liver

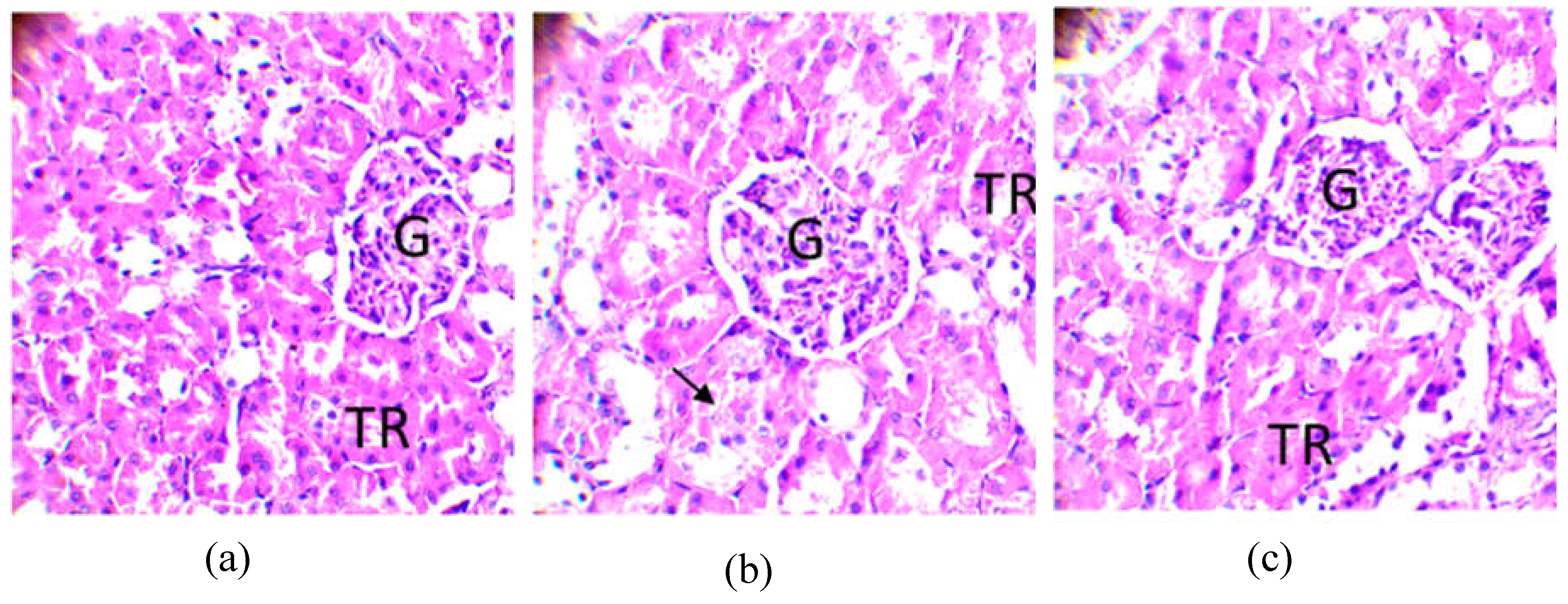

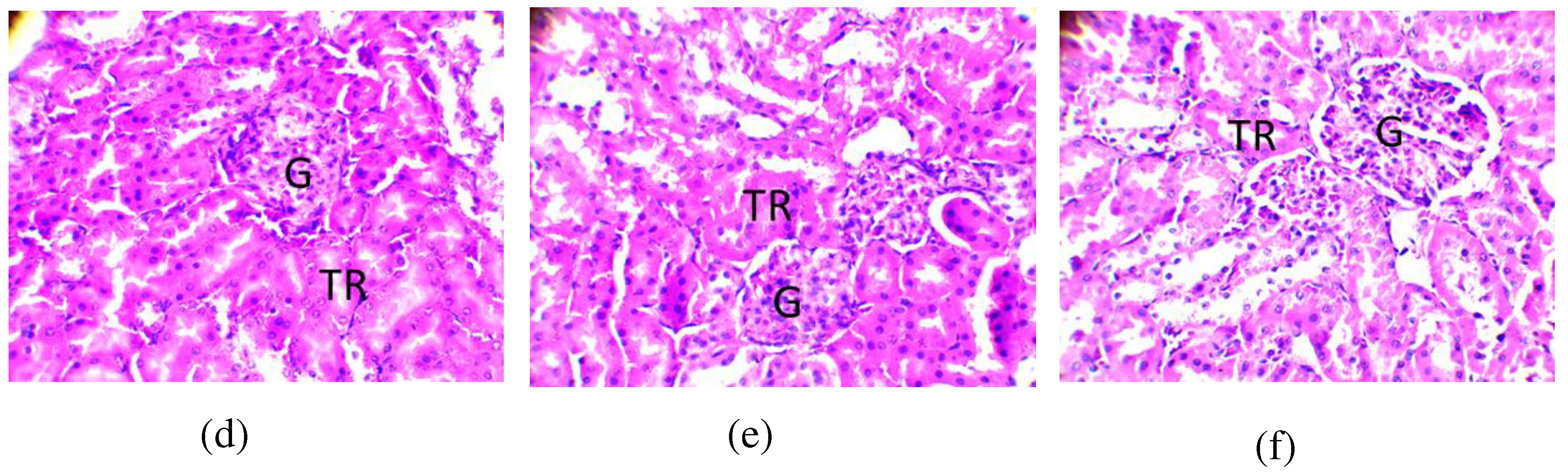

2.8.3. Observation of the kidney

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

4.2. Plant material and sample collection

4.3. Methods of drying cassava organs

4.3.1. Shade drying in the laboratory

4.3.2. Traditional sun drying

4.4. Animal material and acclimatization conditions

4.5. Phytochemical screening of cassava organs

4.5.1. Preparation of extracts

4.5.2. Determination of total phenols

4.5.3. Determination of total flavonoids

4.5.4. Determination of hydrolysable tannins

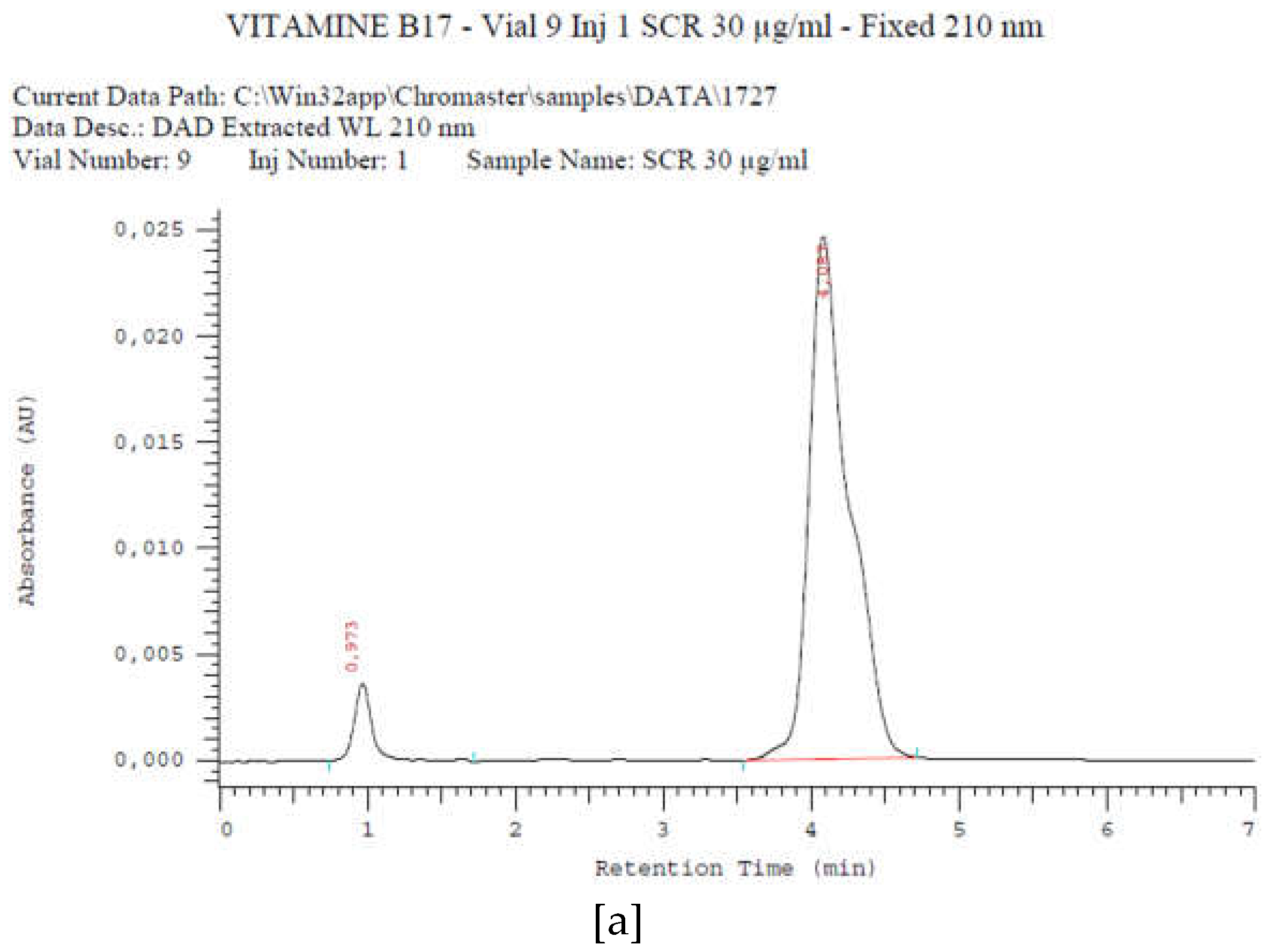

4.6. Method for the determination of amygdalin by HPLC

4.6.1. Extraction of amygdalin from cassava samples and derivatives

4.6.2. Analysis conditions

4.6.3. Quantification procedure

4.6.4. Validation of the amygdalin identification method

4.7. In vitro evaluation of the antioxidant activity of different extracts

4.7.1. Reduction of the DPPH radical

4.7.2. Evaluation of the reducing power of extracts

4.8. Evaluation of the cytotoxicity of extracts

4.9. In vivo evaluation of the anti-inflammatory activity of leaf extracts from three varieties of cassava

4.10. Evaluation of anticancer activity

4.10.1. Experimental design

4.10.2. Determination of biochemical parameters

4.10.3. Anatomical observations

4.10.4. Statistical analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gnangnon F.; Egue M.; Akele-Akpo M.; Amidou S.; Brun L.; Mehinto D.; Houinato D.; Parkin D. Incidence des cancers à Cotonou entre 2014–2016 : les premiers résultats du premier registre des cancers en République du Bénin. Revue d'Épidémiologie et de Santé Publique. 2020; 68, 3 : pp. 0398-7620. [CrossRef]

- Ferlay J.; Ervik M.; Lam F.; Colombet M.; Mery L.; Piñeros M. Observatoire mondial du cancer : « Cancer Today ». Lyon : Centre international de recherche sur le cancer, 2020.

- WHO. Global Health Observatory. (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/girls-aged-15-years-old-that-received-the-recommended-doses-of-hpv-vaccine (accessed June 15, 2022).

- WHO Globocan 2020. The Global Cancer Observatory/Mars 2021.

- Pezzatini M.; Marino G.; Conte S.; Catracchia V. Oncology: a forgotten territory in Africa. Annals of Oncology. 2007; 18, 12 : pp. 2046- 7. [CrossRef]

- Gombé C.M.; Godet J.; Gueye S.M. Cancers in Francophone Africa (Alliance des Ligues Africaines et Méditerranéennes contre le cancer). 2017. Accessed 17/ 04/ 2022.

- Egue M.; Gnangnon F.; Akele-Akpo M.T.; Parkin D. Incidence du cancer à Cotonou (Bénin), premiers résultats du registre des cancers de Cotonou. 2014-2016.

- Astier A.; Blanc-Leger F.; Burtin C.; Cazin J.L.; Chenailler C.; Daouphars M.; Anticancéreux : utilisation pratique (7ème édition). Dossier du CNHIM 2013: XXXIV.

- Yadav A.; Rene E.R.; Mandal M.K.; Dubey K.K. Threat and sustainable technological solution for antineoplastic drugs pollution: Review on a persisting global issue. Chemosphere. 2021; 263:128285. [CrossRef]

- NIOSH list of antineoplastic and other hazardous drugs in healthcare settings, 2016. Connor TH, MacKenzie BA, DeBord DG, Trout DB, O’Callaghan JP. Cincinnati. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Publication Number 2016-161. 2016;42. [CrossRef]

- Valanis BG.; Vollmer W.M.; Steele P. Occupational exposure to antineoplastic agents: selfreported miscarriages and stillbirths among nurses and pharmacists. J Occup Environ Med. 1999;41(8): pp. 632-8. [CrossRef]

- Dranitsaris G.; Johnston M.; Poirier S.; Schueller T.; Milliken D.; Green E. Are health care providers who work with cancer drugs at an increased risk for toxic events? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2005;11(2): pp. 69-78. [CrossRef]

- Halfane Lehmane, Rafiatou Ba, Durand Dah-Nouvlessounon, Haziz Sina, Orou Daouda Bello, Horace Degnonvi, Farid T. Bade, Farid Baba-Moussa, Adolphe Adjanohoun, Lamine Baba-Moussa. Cassava use in southern Benin: Importance and perception of actors involved in the value chain. African Journal of Agricultural Research. 2022. 18(11), pp. 919-932.

- Bahekar S.; Kale R. Phytopharmacological Aspects of Manihot Esculenta Crantz (Cassava) - A Review, Mintage Journal of Pharmaceutical & Medicinal Sciences. 2013. 2, 1: pp. 4-5.

- Andrianarison et al., (2015.

- Viorica-Mirela G.; Socaciu C.; Jianu I.; Florica R.; Florinela F. Identification et évaluation quantitative de l'amygdaline des huiles et noyaux d'abricot, de prune et de pêche. Bulletin USAMV-CN. 2006; 62: pp. 246-253. [CrossRef]

- Yang H.; Chang H.; Lee J.; Kim Y.; Kim H.; Lee M.H.; Shin M.S.; Ham D.H.; Park HK.; Lee H.; Kim CJ. L'amygdaline supprime les expressions induites par les lipopolysaccharides de la cyclooxygénase-2 et de l'oxyde nitrique synthase inductible dans les cellules microgliales BV2 de souris. Neurology Research. 2007; 29 (Suppl 1): pp. 59-64. [CrossRef]

- Zhou C.; Qian L.; Ma H.; Yu X.; Zhang Y. Amélioration de l'amygdaline activée avec la D-glucosidase sur la prolifération et l'apoptose des cellules HepG2. Carbohydr Polym. 2012; 90, 1: pp. 516-523. [CrossRef]

- Liczbinski. 2018.

- Brou K.G.; Mamyrbekova-Bekro J.A.; Dogbo D.O.; Gogbeu S.J.; Bekro Y.A. Sur la Composition Phytochimique Qualitative des Extraits bruts Hydrométhanoliques des Feuilles de 6 Cultivars de Manihot Esculenta Crantz de Côte d’Ivoire. European Journal of Scientific Research. 2010; 45, 2: pp. 200-211.

- El Hazzat N.; Iraqi R.; Bouseta A. Identification par GC-MS et GCFID-O des composés volatils des olives vertes de la variété « Picholine marocaine » : effet de l’origine géographique. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences. 2015; 9(4): pp. 2219-2233. [CrossRef]

- Wei-Feng L.V.; Ding M.Y.; Zheng R. Isolation and quantitation of amygdalin in Apricot-kernel and Prunus Tomentosa Thunb by HPLC with solid-phase extraction. J Chromatogr Sci. 2005; 43(7): pp. 383-7. PMID: 16176653. [CrossRef]

- Bolarinwa I.F.; Orfila C.; Morgan M.R.A. Détermination de l'amygdaline dans les pépins de pomme, les pommes fraîches et les jus de pomme transformés. Food Chemistry. 2014. 170, pp. 437-442. [CrossRef]

- Ganse H.; Gbaguidi F.; Aminou T.; Zime H.; Moudachirou M.; Quentin-Leclercq J. Développement et validation d’une méthode quantitative de dosage par Chromatographie Liquide à Haute Performance UltraViolet (CLHP6UV) de l’artémimisine cultivé au Bénin. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences. 2013. 5(1): pp. 142-149. [CrossRef]

- Wang W.; Xiao X.Z.; Xu X.Q.; Li Z.J.; Zhang J.M. Variation in Amygdalin Content in Kernels of Six Almond Species (Prunus spp. L.) Distributed in China. Frontier in Plant Science. 2022. 12: pp. 753-151.

- Stoilova L.; Krastanov A.; Stoyanova A.; Denev P.; Gargova S. 2007. Activité antioxydante d'un extrait de gingembre (Zingiber officinale). Food Chemistry. 2007.102: pp. 764–770.

- Yi, B.; Hu, L.; Mei, W.; Zhou, K.; Wang, H.; Luo, Y.; Wei, X.; Dai, H. Antioxidant Phenolic Compounds of Cassava (Manihot esculenta) from Hainan. Molecules. 2011; 16, pp. 10157-10167. [CrossRef]

- Ekeledo E.; Sajid L.; Adebayo A.; Joachim M. Potentiel antioxydant des extraits d'écorces et de tiges de variétés de manioc à chair jaune et blanche. Journal international des sciences et technologies alimentaires. 2020; 56, pp. 1333–1342.

- Dilworth L.; Brown R.; Wright M.; Oliver S.; Hall H.; Asemota H. Antioxydants, minéraux et composés bioactifs dans les aliments de base tropicaux. Journal Africain des Sciences et Technologies Alimentaires. 2012; 3, pp. 90 – 98.

- Spina M.; Cuccioloni M.; Sparapani L.; Acciarro S.; Eleuteri A.; Fioretti E. Évaluation comparative de la teneur en flavonoïdes dans l'appréciation de la qualité des légumes sauvages et cultivés destinés à la consommation humaine. Journal des sciences de l'alimentation et de l’agriculture, 2008 ; 88 : pp. 294 – 296.

- Nampoothiri S.V.; Prathapan A.; Cherian O.L.; Raghu K.G.; Venugopalan V.V.; Sundaresan A. 2011. In vitro antioxidant and inhibitory potential of Terminalia bellerica and Emblica officinalis fruits against LDL oxidation and key enzymes linked to type 2 diabetes. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011; 49(1): pp. 125-31. [CrossRef]

- Boeing J.S.; Barizão É.O.; Silva B.C.; Montanher P.F.; de Cinque A.V.; Visentainer J.V. Evaluation of solvent effect on the extraction of phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacities from the berries: application of principal component analysis. Chemistry Central Journal. 2014; 8, pp. 48. [CrossRef]

- Siddhuraju P.; Becker K. The antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities of processed cowpea (Vigna unguiculata Walp) seed extracts. Food Chemistry, 2007; 101, 1 : pp. 10-19. [CrossRef]

- Moshi J.M.; Cosam J.C.; Mbwambo Z.H.; Kapingu M.; Nkunya M.H.H. Testing Beyond Ethnomedical Claims : Brine Shrimp Lethality of some Tanzanian Plants. Journal of Pharmaceutical Biology. 2004; 42: pp. 547-551. [CrossRef]

- Di Carlo K.G.; Mascolo N.; Izzo A.A.; Capasso F. Flavonoids: Old and new aspects of a class of natural therapeutic drugs. Life Sciences. 1999; 65, 4 : pp. 337-353. [CrossRef]

- Boua B.B.; Békro Y.A.; Mamyrbékova-Békro J.A.; Wacothon K.C.; Ehilé E.E. Assessment of sexual stimulant potential of total flavonoïds extracted from leaves of Palisota hirsuta Thumb. 2008.

- Singh S.; Bani S.; Singh S.; Gupta B.D.; Banerjee S.K.; Singh B. Antinflammatory activity of lupeo1. Fitoterapia, 1997; 68, 1: pp. 9-16.

- Ossipov M.H.; Kovelowski C.J.; Porreca F.The increase in morphine antinoceptive potency produced by carrageenan-induced hindpaw inflammation is blocked by nalttrindole, a selective delta-opiod antagonist. Neuroscience Letter, 1995. 184: pp. 173-176. [CrossRef]

- Maity T.K.; Mandal S.C.; Mukherjee P.K. Studies on antiinflammatory effect of Cassia tora leaf extract (fam Leguminosae). Phytotherapy Research, 1998. 12: pp. 221–3.

- Ndiaye M.; Sy G.; Diéye A.M.; Touré M.T.; Faye B. Evaluation de l’activité des feuilles de Annona reticulata (Annonaceae) sur l’œdème aigue de la patte de rat induit par la carragenine. Pharmacology Medicinal Traditional in Africa. 2006. 14: pp. 186-179.

- Ammon H.P.T.; Safayhi H.; Mack T.; Sabieraj J. Mechanism of antiinflammtory actions of curcumne and bowellic acids. Ethnopharmacology, 1993; 38: pp. 113-119.

- Clarke J.M.; Sabrena M.B.; Edward C.; Jo R.W. Surfactant protein A protects growing cells and reduces TNF-alpha activity from LPS-stimulated macrophages. American Journal of Physiology, 1996; 271: pp. 310-319. [CrossRef]

- Huanga M.H.; Wang B.S.; Chiu C.S.; Amagaya S.; Hsieh W.T.; Huang S.S.; Shie P.H.; Huang G.J. Antioxidant, antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of Xanthii Fructus extract. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2011; (135): pp. 545–552. [CrossRef]

- Gilles C.; Nicolas L. 2010. https://planet-vie.ens.fr/thematiques/sante/pharmacologie/l-aspirine#:~:text=L'action%20de%20l'aspirine,d'o%C3%B9%20son%20action%20antipyr%C3%A9tique.

- Alam K.; Pathak D.; Ansari S.H. Evaluation of Anti-inflammatory Activity of Ammomum subulatum fruit extract. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Drug Research. 2011; 3: pp. 37-35.

- Talwar S.; Nandakumar K.; Nayak P.G.; Bansal P.; Mudgal J.; Mor V.; Rao C.M.; Lobo R. Anti-inflammatory activity of Terminalia paniculata bark extract against acute and chronic inflammation in rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2011; 134: pp. 328-323. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Guerrero C.; Herrera M.D.; Ortiz R. Alvarez de Sotomayor M., Fernandez MA: A pharmacological study of Cecropia obtusifolia Bertol aqueous extract. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2001; 76: pp. 279–84.

- Bandaru S.; Reddy. 2002. Encyclopédie du cancer (deuxième édition).

- Tôt B.; Malick L.; Shimizu H. Production de tumeurs intestinales et autres par le dichlorhydrate de 1,2-diméthylhydrazine chez la souris. I. Une étude au microscope électronique à lumière et à transmission des néoplasmes du côlon. Suis J Pathol; 1976; 84: pp. 69–86.

- Karthikkumar V.; Ramachandran V.; Mariadoss A.V.A.; Nurulfiza M.I.; Rajasekar P. Biochemical and molecular aspects of 1,2-dimethylhydrazine (DMH)-induced colon carcinogenesis: a review, Toxicology Research, 2020; Volume 9, pp. 2–18, . [CrossRef]

- Chang H.K.; Shin M.S.; Yang H.Y.; Lee J.W.; Kim Y.S.; Lee M.H.; Kim J.; Kim K.H.; Kim C.J. L'amygdaline induit l'apoptose par la régulation des expressions de Bax et Bcl-2 dans les cellules cancéreuses de la prostate humaine DU145 et LNCaP. Biol. Pharm. Taureau. 2006 ; 29 : pp. 1597–1602. [CrossRef]

- Shim S.M.; Kwon H. Métabolites de l'amygdaline dans des fluides digestifs humains simulés. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010 ; 61 : pp. 770–779. [CrossRef]

- Chang J.; Zhang Y. Dégradation catalytique de l'amygdaline par des enzymes extracellulaires d'Aspergillus niger. Processus. Biochimie. 2012 ; 47 : pp. 195–200. [CrossRef]

- Nowak A.; Zielińska A. Aktywność przeciwnowotworowa amigdaliny Activité anticancéreuse de l'amygdaline. Postępy Fitoter. 2016 ; 17 : pp. 282–292.

- Albogami S.; Hassan A.; Ahmed N.; Alnefaie A.; Alattas A.; Alquthami L.; Alharbi A. Évaluation de la dose efficace d'Amygdalin pour l'amélioration de l'expression des gènes antioxydants et la suppression des dommages oxydatifs chez les souris. 2020; PeerJ, 8, pp. 9232. [CrossRef]

- Houghton P.J.; Raman A. Laboratory Handbook for fractionation of natural extracts. Pharmacognosy Research Laboratories, Departement of Pharmacy, king’s college, London, 1998; pp. 212.

- Sushma P.; Bindu J.; Et R.T.; Narendhirakannan. Évaluation des propriétés antioxydantes et de cytotoxicité de l'amygdaline extraite de prunus dulcis. Kongunadu Research Journal. 2019; 6, 2: pp. 8-12.

- Harborne J.B. 1998. Phytochemical methods: A guide to modern techniques of plant analysis. 3rd ed. chapman and hall international (Ed). NY, pp. 49–188.

- Singleton V.L.; Orthofer R.; Lamuela-Raventós R.M. Analysis of Total Phenols and Other Oxidation Substrates and Antioxidants by Means of Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent. Methods in Enzymology. 1999. 299 : pp. 152-178. [CrossRef]

- Durand D.N.; Hubert A.S.; Nafan D.; Haziz S.; Adolphe A.; Mariam I.; Donald A.; Joachim D.G.; Simeon O.; Kotchoni M.; Dicko H.; Lamine B.M. Phytochemical Analysis and Biological Activities of Cola nitida Bark. Biochemistry Research International, 2015: pp. 1-12, ID 493879.

- Yi Z.B.; Yu Y.; Liang Y.Z.; Zeng B. 2007. In Vitro Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of the Extract of Pericarpium Citri Reticulatae of a New Citrus Cultivar and Its Main Flavonoids. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 2007; 4: pp. 597-603. [CrossRef]

- Mole S.; Waterman P.G. Une analyse critique des techniques de mesure des tanins dans les études écologiques. I. Techniques de définition chimique des tanins. Oecologia (Berlin), 1987; 72: pp. 137–147.

- Badr S.E.A.; Ola A.; Wahdan.; Mohamed S.A.F. Characterization and cytotoxic activity of amygdalin extracted from apricot kernels growing in Egypt. International Research Journal of Public and Environmental Health, 2020; Volume.7 (2), pp. 37-44. [CrossRef]

- Lamien-Médard A.; Lamien-Médard C.E.; Compaoré M.M.H.; Lamien-Medard N.T.R.; Kiendrebeogo M.; Zeba B.; Millogo J.F.; Nacoulma O.G. Polyphenol content and antioxidant activity of fourteen wild edible fruits from Burkina Faso. Molecules. 2008. 13: pp. 581-594. [CrossRef]

- Dieng S.I.M.; Fall A.D.; Diatta-Badji K.; Sarr A.; Sene M.; Sene M.; Mbaye A.; Diatta W.; Bassene E. Evaluation de l’activité antioxydante des extraits hydro-ethanoliques des feuilles et écorces de Piliostigma thonningii Schumach. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences, 2017; volume 11, 2: pp. 768-776. [CrossRef]

- Kawsar S.M.A.; Huq E.; Nahar N. Cytotoxicity assessment of the aerial part of Macrotyloma uniflorum Lim. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 2008 ; 4: pp. 297-300.

- Bassène E. Initiation à la Recherche sur les Substances Naturelles ; Extraction, Analyse, Essais Biologiques. Presses Universitaires de Dakar. 2012.

- Sharma P.; Kaur J.; Sanyal S.N. Effect of etoricoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitor on aberrant crypt formation and apoptosis in 1, 2 dimethyl hydrazine induced colon carcinogenesis in rat model. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 2010; volume 25, 1: pp. 39-48.

| Secondary metabolites | Cassava varieties leaves | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| BEN | MJ | RB | |

| Alkaloids | + | + | + |

| Tannins | + | + | + |

| Saponosides | + | + | + |

| Leuco-anthocyanins | + | + | + |

| Flavonoids | + | + | + |

| Steroids | + | + | + |

| Triterpenes | - | - | - |

| Coumarins | + | + | + |

| Glycosides | + | + | + |

| Cyanogenic derivatives | + | + | + |

| Samples | Organs | Yield (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drying in the sun | Drying in the shade | ||

|

MJ |

Chair | 11.40 | 9.23 |

| 1st skin | 1.36 | 1.18 | |

| 2nd skin | 14.20 | 14.78 | |

| Leaves | - | 1.50 | |

|

BEN |

Chair | 12.41 | 3.55 |

| 1st skin | 1.13 | 1.05 | |

| 2nd skin | 12.26 | 10.95 | |

| Leaves | - | 1.5 | |

|

RB |

Chair | 13.08 | 4.65 |

| 1st skin | 0.98 | 0.95 | |

| 2nd skin | 18.21 | 12.75 | |

| Leaves | - | 1.50 | |

| Substances | Extracts of sun-dried organs | PI (%) | IC50 (µg/mL-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RB | flesh | 87.28±1.25 | 3.00±0.00 |

| 1st skin | 91.72±0.00 | 0.75±0.07 | |

| 2nd skin | 91.15±0.14 | 2.35±1.20 | |

| MJ | flesh | 95.11±0.18 | 0.5±0.22 |

| 1st skin | 93.77±0.54 | 0.25±0.07 | |

| 2nd skin | 85.12±0.67 | 4.6±1.97 | |

| BEN | flesh | 94.71±0.07 | < 0.19 |

| 1st skin | 95.38±0.07 | < 0.19 | |

| 2nd skin | 89.38±0,23 | 7.25±0.35 |

| Substances | Extracts of organs dried in the shade | PI (%) | IC50 (µg/mL-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecule | Quercetine | 82.35±1.86 | 5.75±1.06 |

| RB | flesh | 88.93±0.12 | 17.25±0.35 |

| 2nd skin | 89.60±0.98 | 4.1±0.14 | |

| MJ | flesh | 90.14±0.32 | 21±14.14 |

| 2nd skin | 92.10±0.16 | 0.5±0 | |

| BEN | flesh | 85.88±0.28 | 9.6±0.56 |

| 2nd skin | 91.37±0.18 | 2.75±0.35 |

| Standard/samples | IC50 (µg.mL-1) | |

|---|---|---|

| DPPH | FRAP | |

| Ascorbic acid | 1,11±0,09 | - |

| RB | 8,11±0,70 | 0.63±0.04 |

| MJ | 3,25±0,32 | 0.69±0.03 |

| BEN | 3,99±0,27 | 0.52±0.04 |

| Amygdalin extracts | RB | BEN | MJ |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC50 (mg/mL) | 12,73 | 11,60 | 12,32 |

| R2 | 0,80 | 0,64 | 0,41 |

| Variables | R0 | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | P-value | Significativity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hb | 13.66b±0.49 | 16.43a±0.9 | 9.00c±1.0 | 15.6a±0.70 | 14.2b±0.30 | 13.6b±0.60 | 7.215e-07 | *** |

| Hte | 41.00b±2.00 | 9.00c±1.00 | 19.33d±2.00 | 30.33c±3.20 | 42.00b±2.00 | 39.33b±1.50 | 6934e-08 | *** |

| NR | 4.43b±0.26 | 5.46b±0.30 | 10.79a±2.50 | 6.16b±1.80 | 7.62b±2.40 | 4.26b±0.00 | 0.003153 | ** |

| NB | 7.77ab±1.15 | 4.18b±0.80 | 13.82a±6.10 | 7.91ab±2.40 | 8.86ab±0.40 | 7.12ab±1.00 | 0.02841 | * |

| Lym | 28.00c±7.21 | 39.33c±7.20 | 114.66a±7.30 | 84.00b±11.10 | 37.33c±11.90 | 21.66c±1.50 | 5.907e-08 | *** |

| Neut | 67.33b±11.84 | 61.66b±6.40 | 114.33a±8.50 | 82.00b±16.30 | 62.33b±11.50 | 72.00b±11.20 | 0.0008887 | *** |

| Eos | 0.33b±0.57 | 0.33b±0.50 | 1.66a±0.50 | 00b±00 | 0.33b±0.50 | 00b±00 | 0.009067 | ** |

| Mono | 0.33b±0.57 | 00.00a±00.00 | 00.00a±00.00 | 0.66a±1.10 | 00.00a±00.00 | 0.66a±0.50 | 0.4755 | NS |

| ASAT | 97.66b±9.07 | 96.66b±4.04 | 570.33a±39.80 | 147.33b±46.50 | 121.00b±8.80 | 102.33b±2.50 | 1.427e-10 | *** |

| ALAT | 86.33c±10.21 | 67.33c±10.10 | 567.66a±55.01 | 160.33b±26.50 | 122.66bc±8.10 | 91.00c±5.20 | 1.311e-10 | *** |

| CREAT | 6.92c±0.56 | 8.10c±0.40 | 19.57a±1.50 | 8.21c±0.80 | 13.10b±5.30 | 7.60c±1.40 | 0.0001756 | *** |

| Name of the varieties | Characteristics | Quality and different processing options |

|---|---|---|

|

BEN 86052 |

soft variety |

Gari, Tapioca, Agbéli, lafoun |

| brown stem | ||

| Dark green leaf, edible. | ||

| Average yield in pods: 30%. | ||

|

RB 89509 |

soft variety |

Gari, Tapioca, Agbéli, lafoun |

| brown stem | ||

| green leaf, edible | ||

| low hydrocyanic acid content | ||

|

Yellow cassava (MJ) |

soft variety |

Gari, semolina |

| white stem | ||

| edible leaf | ||

| low hydrocyanic acid content |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).