Submitted:

03 May 2023

Posted:

08 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Basic Characterization and Localization of β-D-Glucans in the Plant

2. Content of β-D-Glucans in Grains of Poales

3. Biosynthesis of β-D-Glucans in Poales

4. Environmental Factors Influencing the β-D-Glucans Content

5. Function of β-D-Glucans in the Plant Organism

6. Molecular Markers as Breeding Tools for β-D-Glucans Manipulations

7. Impact of Processing Technologies on β-D-Glucans in Cereals

7.1. Effect of the Milling Process and Grain Peeling

7.2. Effects and Changes of β-D-Glucans in the Process of Dough Preparation, Fermentation, and Baking

7.3. Effect of Extrusion

8. The Range of Applications of β-D-Glucans in Food Products

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fincher, G.B. Revolutionary Times in Our Understanding of Cell Wall Biosynthesis and Remodeling in the Grasses. Plant Physiology 2009, 149, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, R.A.; Gidley, M.J.; Fincher, G.B. Heterogeneity in the Chemistry, Structure and Function of Plant Cell Walls. Nat Chem Biol 2010, 6, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincher, G.B.; Stone, B.A. CEREALS|Chemistry of Nonstarch Polysaccharides. In Encyclopedia of Grain Science; Wrigley, C., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, 2004; pp. 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havrlentova 2006 Content of β-D-Glucan in Cereal Grains. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2006, 45, 97–103.

- Redaelli, R.; Sgrulletta, D.; Scalfati, G.; De Stefanis, E.; Cacciatori, P. Naked Oats for Improving Human Nutrition: Genetic and Agronomic Variability of Grain Bioactive Components. Crop science 2009. https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=US201301657634.

- Gajdošová, A.; Petruláková, Z.; Havrlentová, M.; Červená, V.; Hozová, B.; Šturdík, E.; Kogan, G. The Content of Water-Soluble and Water-Insoluble β-d-Glucans in Selected Oats and Barley Varieties. Carbohydrate Polymers 2007, 70, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, P.; Tosh, S.M.; Brummer, Y.; Olsson, O. Identification of High β-Glucan Oat Lines and Localization and Chemical Characterization of Their Seed Kernel β-Glucans. Food Chemistry 2013, 137, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckeridge, M.S.; Rayon, C.; Urbanowicz, B.; Tiné, M.A.S.; Carpita, N.C. Mixed Linkage (1→3),(1→4)-β- d -Glucans of Grasses. Cereal Chemistry Journal 2004, 81, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykut-Domańska, E.; Rzedzicki, Z.; Zarzycki, P.; Sobota, A.; Błaszczak, W. Distribution of (1,3)(1,4)-Beta-D-Glucans in Grains of Polish Oat Cultivars and Lines (Avena Sativa L.). Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2016, 66, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trethewey, J.A.K.; Campbell, L.M.; Harris, P.J. (1→3),(1→4)-ß-d-Glucans in the Cell Walls of the Poales (Sensu Lato): An Immunogold Labeling Study Using a Monoclonal Antibody. American Journal of Botany 2005, 92, 1660–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Sanchez, M.; Verhertbruggen, Y.; Scheller, H.V.; Ronald, P. Abundance of Mixed Linkage Glucan in Mature Tissues and Secondary Cell Walls of Grasses. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2013, 8, e23143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hozlár, P.; Gregusová, V.; Nemeček, P.; Šliková, S.; Havrlentová, M. Study of Dynamic Accumulation in β-D-Glucan in Oat (Avena Sativa L.) during Plant Development. Polymers 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.; Hu, Y. Effect of Nitrogen Forms and Levels on β-Glucan Accumulation in Grains of Oat ( Avena Sativa L.) Plants. Z. Pflanzenernähr. Bodenk. 2009, 172, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, M.S.; Macri, L.J.; MacGregor, A.W. Structure and Physicochemical Properties of Barley Non-Starch Polysaccharides—II. Alkaliextractable β-Glucans and Arabinoxylans. Carbohydrate Polymers 1998, 35, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-C.; Saldivar, R.K.; Liang, P.-H.; Hsieh, Y.S.Y. Structures, Biosynthesis, and Physiological Functions of (1,3;1,4)-β-d-Glucans. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fincher, G.B. Exploring the Evolution of (1,3;1,4)-β-d-Glucans in Plant Cell Walls: Comparative Genomics Can Help! Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2009, 12, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staudte, R.G.; Woodward, J.R.; Fincher, G.B.; Stone, B.A. Water-Soluble (1→3), (1→4)-β-d-Glucans from Barley (Hordeum Vulgare) Endosperm. III. Distribution of Cellotriosyl and Cellotetraosyl Residues. Carbohydrate Polymers 1983, 3, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.A.; Fincher, G.B. (1,3;1,4)-β-D-Glucans in Cell Walls of the Poaceae, Lower Plants, and Fungi: A Tale of Two Linkages. Molecular Plant 2009, 2, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skendi, A.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Lazaridou, A.; Izydorczyk, M.S. Structure and Rheological Properties of Water Soluble β-Glucans from Oat Cultivars of Avena Sativa and Avena Bysantina. Journal of Cereal Science 2003, 38, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, M.S.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Macri, L.J.; MacGregor, A.W. Fractionation of Oat (1→3), (1→4)-β-D-Glucans and Characterisation of the Fractions. Journal of Cereal Science 1998, 27, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosh, S.; Brummer, Y.; Wolever, T.; Wood, P. Glycemic Response to Oat Bran Muffins Treated to Vary Molecular Weight of β-Glucan. Cereal chemistry. 2008, 85, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridou, A.; Biliaderis, C.G. Molecular Aspects of Cereal β-Glucan Functionality: Physical Properties, Technological Applications and Physiological Effects. Journal of Cereal Science 2007, 46, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, J.R.; Fincher, G.B.; Stone, B.A. Water-Soluble (1→3), (1→4)-β-D-Glucans from Barley (Hordeum Vulgare) Endosperm. II. Fine Structure. Carbohydrate Polymers 1983, 3, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.; Fincher, G. Current Challenges in Cell Wall Biology in the Cereals and Grasses. Frontiers in plant science 2012, 3, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doehlert, D.C.; Simsek, S. Variation in Β-glucan Fine Structure, Extractability, and Flour Slurry Viscosity in Oats Due to Genotype and Environment. Cereal chemistry 2012, 89, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, M.S.; Dexter, J.E. Barley β-Glucans and Arabinoxylans: Molecular Structure, Physicochemical Properties, and Uses in Food Products–a Review. Food Research International 2008, 41, 850–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, H.P.; Tharanathan, R.N. Carbohydrates—The Renewable Raw Materials of High Biotechnological Value. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2003, 23, 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.S. Wood, P.J., Pietrzak, L.N., Fulcher, R.G. Mixed Linkage beta-Glucan, Protein Content, and Kernel Weight in Avena Species. Cereal Chem. 1993. Available online: https://www.cerealsgrains.org/publications/cc/backissues/1993/Documents/cc1993a47.html (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Cui, W.; Wood, P.J. Relationships between Structural Features, Molecular Weight and Rheological Properties of Cereal β-D-Glucans. In Hydrocolloids; Nishinari, K., Ed.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, 2000; pp. 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulone, V.; Schwerdt, J.G.; Fincher, G.B. Co-Evolution of Enzymes Involved in Plant Cell Wall Metabolism in the Grasses. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Meenu, M.; Liu, H.; Xu, B. A Concise Review on the Molecular Structure and Function Relationship of β-Glucan. IJMS 2019, 20, 4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, U.; Cummins, E. Factors Influencing β-Glucan Levels and Molecular Weight in Cereal-Based Products. Cereal Chemistry Journal 2009, 86, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, S.; Djukic, N.; Knezevic, D.; Lekovic, S. Divergence of Barley and Oat Varieties According to Their Content of β-Glucan. J Serb Chem Soc 2017, 82, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGregor, A.W. BARLEY. In Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition (Second Edition); Caballero, B., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishantha, M.D.L.C.; Zhao, X.; Jeewani, D.C.; Bian, J.; Nie, X.; Weining, S. Direct Comparison of β-Glucan Content in Wild and Cultivated Barley. International Journal of Food Properties 2018, 21, 2218–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauer, J.C.; Cu, S.; Burton, R.A.; Eglinton, J.K. Variation in Barley (1 → 3, 1 → 4)-β-Glucan Endohydrolases Reveals Novel Allozymes with Increased Thermostability. Theor Appl Genet 2017, 130, 1053–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elouadi, F.; Amri, A.; El-baouchi, A.; Kehel, Z.; Salih, G.; Jilal, A.; Kilian, B.; Ibriz, M. Evaluation of a Set of Hordeum Vulgare Subsp. Spontaneum Accessions for β-Glucans and Microelement Contents. Agriculture 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eticha, F.; Grausgruber, H.; Berghoffer, E. Multivariate Analysis of Agronomic and Quality Traits of Hull-Less Spring Barley (Hordeum Vulgare L.). Journal of plant breeding and crop science 2010, 2, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meints, B.; Vallejos, C.; Hayes, P. Multi-Use Naked Barley: A New Frontier. Journal of Cereal Science 2021, 102, 103370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.M. Oat Antioxidants. Journal of Cereal Science 2001, 33, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mälkki, Y. Trends in Dietary Fibre Research and Development. Acta Alimentaria 2004, 33, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulcher, R.G.; Miller, S.S. Structure of Oat Bran and Distribution of Dietary Fiber Components. Oat bran 1993, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, R.W.; Brown, J.C.W.; Leggett, J.M. Interspecific and Intraspecific Variation in Grain and Groat Characteristics of Wild Oat (Avena) Species: Very High Groat (1→3),(1→4)-β- -Glucan in an Avena Atlantica Genotype. Journal of Cereal Science 2000, 31, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, U.; Cummins, E. Simulation of the Factors Affecting β-Glucan Levels during the Cultivation of Oats. Journal of Cereal Science 2009, 50, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redaelli, R.; Del Frate, V.; Bellato, S.; Terracciano, G.; Ciccoritti, R.; Germeier, C.U.; De Stefanis, E.; Sgrulletta, D. Genetic and Environmental Variability in Total and Soluble β-Glucan in European Oat Genotypes. Journal of Cereal Science 2013, 57, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, V.S.; Khoreva, V.I.; Konarev, A.V.; Shelenga, T.V.; Blinova, E.V.; Malyshev, L.L.; Loskutov, I.G. Evaluating Germplasm of Cultivated Oat Species from the VIR Collection under the Russian Northwest Conditions. Plants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loskutov, I.G.; Polonskiy, V.I. Content of β-Glucans in Oat Grain as a Perspective Direction of Breeding for Health Products and Fodder.

- Amer, S.A.; Attia, G.A.; Aljahmany, A.A.; Mohamed, A.K.; Ali, A.A.; Gouda, A.; Alagmy, G.N.; Megahed, H.M.; Saber, T.; Farahat, M. Effect of 1,3-Beta Glucans Dietary Addition on the Growth, Intestinal Histology, Blood Biochemical Parameters, Immune Response, and Immune Expression of CD3 and CD20 in Broiler Chickens. Animals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, J.P.; Pescatore, A.J. Barley β-Glucan in Poultry Diets. Annals of translational medicine 2014, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richmond, T.A.; Somerville, C.R. The Cellulose Synthase Superfamily. 2000, 55(1), 44–52. [CrossRef]

- Hazen, S.P.; Scott-Craig, J.S.; Walton, J.D. Cellulose Synthase-Like Genes of Rice. Plant Physiol. 2002, 128, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrokhi, N.; Burton, R.A.; Brownfield, L.; Hrmova, M.; Wilson, S.M.; Bacic, A.; Fincher, G.B. Plant Cell Wall Biosynthesis: Genetic, Biochemical and Functional Genomics Approaches to the Identification of Key Genes. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2006, 4, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocuron, J.-C.; Lerouxel, O.; Drakakaki, G.; Alonso, A.P.; Liepman, A.H.; Keegstra, K.; Raikhel, N.; Wilkerson, C.G. A Gene from the Cellulose Synthase-like C Family Encodes a -1,4 Glucan Synthase. PLANT BIOLOGY 6.

- Burton, R.A.; Wilson, S.M.; Hrmova, M.; Harvey, A.J.; Shirley, N.J.; Medhurst, A.; Stone, B.A.; Newbigin, E.J.; Bacic, A.; Fincher, G.B. Cellulose Synthase-like CslF Genes Mediate the Synthesis of Cell Wall (1, 3; 1, 4)-ß-D-Glucans. Science 2006, 311, 1940–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doblin, M.S.; Pettolino, F.A.; Wilson, S.M.; Campbell, R.; Burton, R.A.; Fincher, G.B.; Newbigin, E.; Bacic, A. A Barley Cellulose Synthase-like CSLH Gene Mediates (1,3;1,4)-β-d-Glucan Synthesis in Transgenic Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 5996–6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Huang, J.; Xu, Y. The Cellulose Synthase Superfamily in Fully Sequenced Plants and Algae. BMC Plant Biol 2009, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, A.; Lahnstein, J.; Jeffery, D.W.; Khor, S.F.; Schwerdt, J.G.; Shirley, N.J.; Hooi, M.; Xing, X.; Burton, R.A.; Bulone, V. A Novel (1,4)-β-Linked Glucoxylan Is Synthesized by Members of the Cellulose Synthase-Like F Gene Family in Land Plants. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yan, L.; Liu, M.; Guo, G.; Wu, B. Analysis of Beta-D-Glucan Biosynthetic Genes in Oat Reveals Glucan Synthesis Regulation by Light. Annals of Botany. [CrossRef]

- Dimitroff, G.; Little, A.; Lahnstein, J.; Schwerdt, J.G.; Srivastava, V.; Bulone, V.; Burton, R.A.; Fincher, G.B. (1,3;1,4)-β-Glucan Biosynthesis by the CSLF6 Enzyme: Position and Flexibility of Catalytic Residues Influence Product Fine Structure. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 2054–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, C.; Freeman, J.; Jones, H.D.; Sparks, C.; Pellny, T.K.; Wilkinson, M.D.; Dunwell, J.; Andersson, A.A.M.; Åman, P.; Guillon, F.; et al. Down-Regulation of the CSLF6 Gene Results in Decreased (1,3;1,4)- β - d -Glucan in Endosperm of Wheat. Plant Physiology 2010, 152, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, A.; Schwerdt, J.G.; Shirley, N.J.; Khor, S.F.; Neumann, K.; O’Donovan, L.A.; Lahnstein, J.; Collins, H.M.; Henderson, M.; Fincher, G.B.; et al. Revised Phylogeny of the Cellulose Synthase Gene Superfamily: Insights into Cell Wall Evolution. Plant Physiology 2018, 177, 1124–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, R.A.; Collins, H.M.; Kibble, N.A.J.; Smith, J.A.; Shirley, N.J.; Jobling, S.A.; Henderson, M.; Singh, R.R.; Pettolino, F.; Wilson, S.M.; et al. Over-Expression of Specific HvCslF Cellulose Synthase-like Genes in Transgenic Barley Increases the Levels of Cell Wall (1,3;1,4)-β-d-Glucans and Alters Their Fine Structure: Over-Expression of CslF Genes in Barley. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2011, 9, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taketa, S.; Yuo, T.; Tonooka, T.; Tsumuraya, Y.; Inagaki, Y.; Haruyama, N.; Larroque, O.; Jobling, S.A. Functional Characterization of Barley Betaglucanless Mutants Demonstrates a Unique Role for CslF6 in (1,3;1,4)-β-D-Glucan Biosynthesis. Journal of Experimental Botany 2012, 63, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwerdt, J.G.; MacKenzie, K.; Wright, F.; Oehme, D.; Wagner, J.M.; Harvey, A.J.; Shirley, N.J.; Burton, R.A.; Schreiber, M.; Halpin, C.; et al. Evolutionary Dynamics of the Cellulose Synthase Gene Superfamily in Grasses. Plant Physiology 2015, 168, 968–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Sánchez, M.E.; Verhertbruggen, Y.; Christensen, U.; Chen, X.; Sharma, V.; Varanasi, P.; Jobling, S.A.; Talbot, M.; White, R.G.; Joo, M.; et al. Loss of Cellulose Synthase - Like F6 Function Affects Mixed-Linkage Glucan Deposition, Cell Wall Mechanical Properties, and Defense Responses in Vegetative Tissues of Rice. Plant Physiol. 2012, 159, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, R.A.; Jobling, S.A.; Harvey, A.J.; Shirley, N.J.; Mather, D.E.; Bacic, A.; Fincher, G.B. The Genetics and Transcriptional Profiles of the Cellulose Synthase-Like HvCslF Gene Family in Barley. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 1821–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Gimenez, G.; Barakate, A.; Smith, P.; Stephens, J.; Khor, S.F.; Doblin, M.S.; Hao, P.; Bacic, A.; Fincher, G.B.; Burton, R.A.; et al. Targeted Mutation of Barley (1,3;1,4)-β-glucan Synthases Reveals Complex Relationships between the Storage and Cell Wall Polysaccharide Content. Plant J. 2020, 104, 1009–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coon, M.A. Characterization and Variable Expression of the CslF6 Homologs in Oat (Avena Sp.). 2012. Master thesis. Brigham Young University – Provo. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4749&context=etd.

- Wilson, S.M.; Ho, Y.Y.; Lampugnani, E.R.; Van de Meene, A.M.L.; Bain, M.P.; Bacic, A.; Doblin, M.S. Determining the Subcellular Location of Synthesis and Assembly of the Cell Wall Polysaccharide (1,3; 1,4)-β- d -Glucan in Grasses. The Plant Cell 2015, 27, 754–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Vendrell, A.M.; Guasch, J.; Francesch, M.; Molina-Cano, J.L.; Brufau, J. Determination of β-(1–3), (1–4)-D-Glucans in Barley by Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A 1995, 718, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redaelli, R.; Scalfati, G.; Ciccoritti, R.; Cacciatori, P.; De Stefanis, E.; Sgrulletta, D. Effects of Genetic and Agronomic Factors on Grain Composition in Oats. Cereal Research Communications 2015, 43, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, R.; Molina-Cano, J. Changes in Malting Quality and Its Determinants in Response to Abiotic Stresses. Barley science-recent advances from molecular biology to agronomy of yield and quality, Food Products Press, New York, 2002, 523–550.

- Güler, M. Barley Grain β-Glucan Content as Affected by Nitrogen and Irrigation. Field Crops Research 2003, 84, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.M. Genotype and Environment Effects on Oat Beta-Glucan Concentration. Crop Science, 1991; 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doehlert, D.C.; McMullen, M.S.; Hammond, J.J. Genotypic and Environmental Effects on Grain Yield and Quality of Oat Grown in North Dakota. Crop Science 2001, 41, 1066–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvoncova, D.; Havrlentova, M.; Hlinkova, A.; Hozlar, P. Effect of Fertilization and Variety on the β-Glucan Content in the Grain of Oats. ZNTJ, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorash, A.; Armonienė, R.; Mitchell Fetch, J.; Liatukas, Ž.; Danytė, V. Aspects in Oat Breeding: Nutrition Quality, Nakedness and Disease Resistance, Challenges and Perspectives: Aspects in Oat Breeding. Ann Appl Biol 2017, 171, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

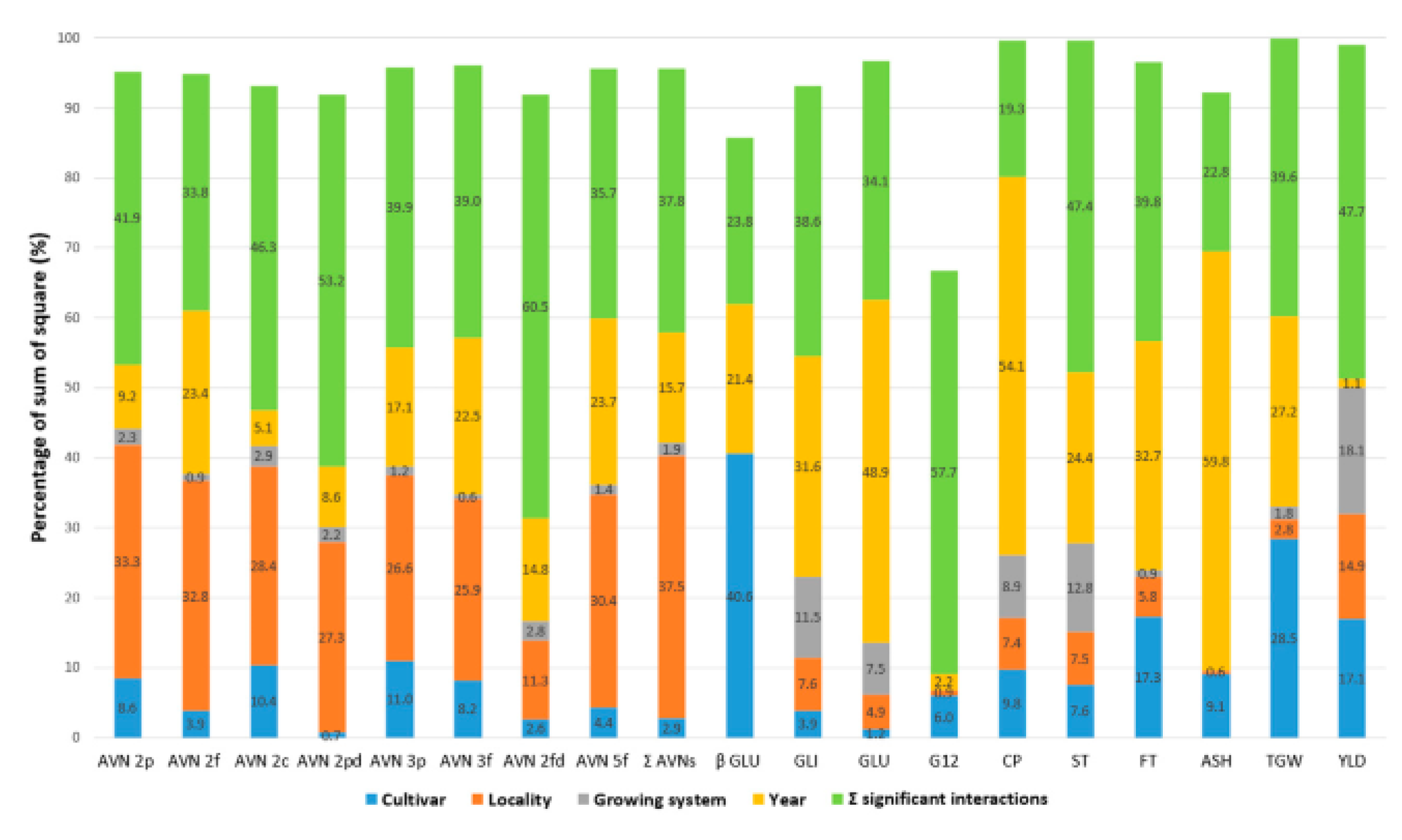

- Dvořáček, V.; Jágr, M.; Kotrbová Kozak, A.; Capouchová, I.; Konvalina, P.; Faměra, O.; Hlásná Čepková, P. Avenanthramides: Unique Bioactive Substances of Oat Grain in the Context of Cultivar, Cropping System, Weather Conditions and Other Grain Parameters. Plants 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Arcangelis, E.; Messia, M.C.; Marconi, E. Variation of Polysaccharides Profiles in Developing Kernels of Different Barley Cultivars. Journal of Cereal Science 2019, 85, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, R.; Kamil, A.; Chu, Y. Global Review of Heart Health Claims for Oat Beta-Glucan Products. Nutrition Reviews 2020, 78 (Supplement_1), 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Anjum, F.M.; Zahoor, T.; Nawaz, H.; Dilshad, S.M.R. Beta Glucan: A Valuable Functional Ingredient in Foods. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2012, 52, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havrlentová, M.; Gregusová, V.; Šliková, S.; Nemeček, P.; Hudcovicová, M.; Kuzmová, D. Relationship between the Content of β-D-Glucans and Infection with Fusarium Pathogens in Oat (Avena Sativa L.) Plants. Plants 2020, 9, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrmova, M.; Fincher, G.B. Structure-Function Relationships of β- D-Glucan Endo- and Exohydrolases from Higher Plants. Plant Molecular Biology 2001, 47, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulin, S.; Buchala, A.J.; Fincher, G.B. Induction of (1→3,1→4)-β-D-Glucan Hydrolases in Leaves of Dark-Incubated Barley Seedlings. Planta 2002, 215, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillon, F.; Tranquet, O.; Quillien, L.; Utille, J.-P.; Ordaz Ortiz, J.J.; Saulnier, L. Generation of Polyclonal and Monoclonal Antibodies against Arabinoxylans and Their Use for Immunocytochemical Location of Arabinoxylans in Cell Walls of Endosperm of Wheat. Journal of Cereal Science 2004, 40, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafford, K.; Haleux, P.; Henderson, M.; Parker, M.; Shirley, N.J.; Tucker, M.R.; Fincher, G.B.; Burton, R.A. Grain Development in Brachypodium and Other Grasses: Possible Interactions between Cell Expansion, Starch Deposition, and Cell-Wall Synthesis. Journal of Experimental Botany 2013, 64, 5033–5047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpita, N.C. Structure and Biogenesis of the Cell Walls of Grasses. Annual review of plant biology 1996, 47, 445–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-B.; Olek, A.T.; Carpita, N.C. Cell Wall and Membrane-Associated Exo-β-d-Glucanases from Developing Maize Seedlings1. Plant Physiology 2000, 123, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoson, T. Apoplast as the Site of Response to Environmental Signals. Journal of Plant Research 1998, 111, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havrlentová, M.; Šliková, S.; Gregusová, V.; Kovácsová, B.; Lančaričová, A.; Nemeček, P.; Hendrichová, J.; Hozlár, P. The Influence of Artificial Fusarium Infection on Oat Grain Quality. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.; Schöneberg, T.; Vogelgsang, S.; Morisoli, R.; Bertossa, M.; Mauch-Mani, B.; Mascher, F. Resistance against Fusarium Graminearum and the Relationship to β-Glucan Content in Barley Grains. Eur J Plant Pathol 2018, 152, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregusová, V.; Kaňuková, Š.; Hudcovicová, M.; Bojnanská, K.; Ondreičková, K.; Piršelová, B.; Mészáros, P.; Lengyelová, L.; Galuščáková, Ľ.; Kubová, V.; et al. The Cell-Wall β-d-Glucan in Leaves of Oat (Avena Sativa L.) Affected by Fungal Pathogen Blumeria Graminis f. Sp. Avenae. Polymers, 2022; 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofuji, K.; Aoki, A.; Tsubaki, K.; Konishi, M.; Isobe, T.; Murata, Y. Antioxidant Activity of β-Glucan. ISRN Pharm 2012, 2012, 125864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattanzio, V.; Lattanzio, V.M.T.; Cardinali, A. Role of Phenolics in the Resistance Mechanisms of Plants against Fungal Pathogens and Insects. Phytochemistry: Advance in research 2006, 661, 23–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.-P.; Zhou, H.-M.; Zhu, K.-R.; Li, Q. Effect of Thermal Processing on the Molecular, Structural, and Antioxidant Characteristics of Highland Barley β-Glucan. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 271, 118416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, I.; Willats, W.G. Plant Cell Walls: New Insights from Ancient Species. Plant signaling & behavior 2008, 3, 743–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstens, S.; Decraemer, W.F.; Verbelen, J.-P. Cell Walls at the Plant Surface Behave Mechanically like Fiber-Reinforced Composite Materials. Plant Physiology 2001, 127, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holthaus, J.; Holland, J.; White, P.; Frey, K. Inheritance of Β-glucan Content of Oat Grain. Crop Science 1996, 36, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshghi, R.; Akhundova, E. Inheritance Pattern of β-Glucan and Protein Countents in Hulless Barley. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology 2010, 12, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Swanston, J. The Barley Husk: A Potential Barrier to Future Success. Barley: Physical properties, genetic factors and environmental impacts on growth. Nova Science Publishers, inc., New york 2014, 81–106.

- Marcotuli, I.; Houston, K.; Schwerdt, J.G.; Waugh, R.; Fincher, G.B.; Burton, R.A.; Blanco, A.; Gadaleta, A. Genetic Diversity and Genome Wide Association Study of β-Glucan Content in Tetraploid Wheat Grains. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0152590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walling, J.G.; Sallam, A.H.; Steffenson, B.J.; Henson, C.; Vinje, M.A.; Mahalingam, R. Quantitative Trait Loci Impacting Grain Β-glucan Content in Wild Barley (Hordeum Vulgare Ssp. Spontaneum) Reveals Genes Associated with Cell Wall Modification and Carbohydrate Metabolism. Crop Science 2022, 62, 1213–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.; Li, M.; Xie, S.; Wu, D.; Ye, L.; Zhang, G. Identification of Genetic Loci and Candidate Genes Related to β-Glucan Content in Barley Grain by Genome-Wide Association Study in International Barley Core Selected Collection. Molecular Breeding 2021, 41, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

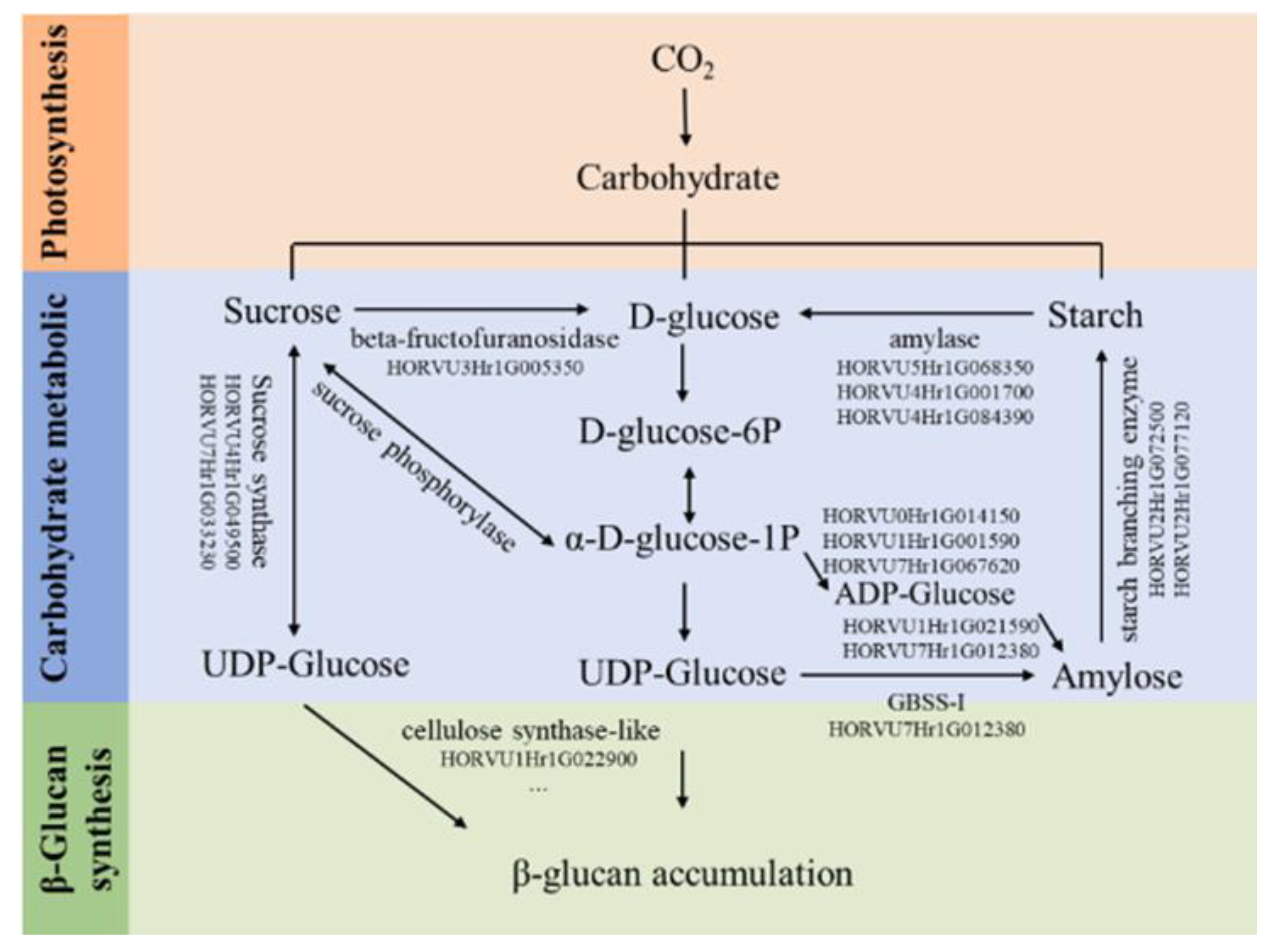

- Geng, L.; He, X.; Ye, L.; Zhang, G. Identification of the Genes Associated with β-Glucan Synthesis and Accumulation during Grain Development in Barley. Food Chemistry: Molecular Sciences 2022, 5, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, M.A.; Asoro, F.G.; Scott, M.P.; White, P.J.; Beavis, W.D.; Jannink, J.-L. Genome-Wide Association Study for Oat (Avena Sativa L.) Beta-Glucan Concentration Using Germplasm of Worldwide Origin. Theor Appl Genet 2012, 125, 1687–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, C.M.; Oliveira, G.; Pacheco, M.T.; Federizzi, L.C. Characterization and Absolute Quantification of the Cellulose Synthase-like F6 Homoeologs in Oats. Euphytica 2020, 216, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motilva, M.-J.; Serra, A.; Borrás, X.; Romero, M.-P.; Domínguez, A.; Labrador, A.; Peiró, L. Adaptation of the Standard Enzymatic Protocol (Megazyme Method) to Microplaque Format for β-(1, 3)(1, 4)-d-Glucan Determination in Cereal Based Samples with a Wide Range of β-Glucan Content. Journal of Cereal Science 2014, 59, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, D.; Caffe-Treml, M.; Krishnan, P. A Single Analytical Platform for the Rapid and Simultaneous Measurement of Protein, Oil, and Beta-Glucan Contents of Oats Using Near-Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy. Cereal Foods World 2018, 63, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kamp, J.W.; Asp, N.-G.; Miller-Jones, J.; Schaafsma, G. Dietary Fibre: Bio-Active Carbohydrates for Food and Feed; Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2004.

- Henrion, M.; Francey, C.; Lê, K.-A.; Lamothe, L. Cereal B-Glucans: The Impact of Processing and How It Affects Physiological Responses. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Li, L.; Wang, X. Molecular Characterization of Arabinoxylans from Hull-Less Barley Milling Fractions. Molecules 2011, 16, 2743–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, G.; Rossnagel, B.; Tyler, R.; Bhatty, R. Distribution of Β-glucan in the Grain of Hull-less Barley. Cereal Chemistry 2000, 77, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brier, N.; Hemdane, S.; Dornez, E.; Gomand, S.V.; Delcour, J.A.; Courtin, C.M. Structure, Chemical Composition and Enzymatic Activities of Pearlings and Bran Obtained from Pearled Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.) by Roller Milling. Journal of Cereal Science 2015, 62, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, M.; Cenkowski, S.; Dexter, J. Optimizing the Bioactive Potential of Oat Bran by Processing. Cereal Foods World 2014, 59, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosi, E.A.; Ré, E.; Lucero, H.; Masciarelli, R. Dietary Fiber Obtained from Amaranth (Amaranthus Cruentus) Grain by Differential Milling. Food Chemistry 2001, 73, 441–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escarnot, E.; Dornez, E.; Verspreet, J.; Agneessens, R.; Courtin, C.M. Quantification and Visualization of Dietary Fibre Components in Spelt and Wheat Kernels. Journal of Cereal Science 2015, 62, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallero, A.; Empilli, S.; Brighenti, F.; Stanca, A. High (1→ 3, 1→ 4)-β-Glucan Barley Fractions in Bread Making and Their Effects on Human Glycemic Response. Journal of cereal science 2002, 36, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtekjølen, A.; Olsen, H.; Færgestad, E.; Uhlen, A.; Knutsen, S. Variations in Water Absorption Capacity and Baking Performance of Barley Varieties with Different Polysaccharide Content and Composition. LWT-Food Science and Technology 2008, 41, 2085–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, M.; Chornick, T.; Paulley, F.; Edwards, N.; Dexter, J. Physicochemical Properties of Hull-Less Barley Fibre-Rich Fractions Varying in Particle Size and Their Potential as Functional Ingredients in Two-Layer Flat Bread. Food Chemistry 2008, 108, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knuckles, B.; Hudson, C.; Chiu, M.; Sayre, R. Effect of Beta-Glucan Barley Fractions in High-Fiber Bread and Pasta. Cereal foods world (USA) 1997.

- Jacobs, M.S.; Izydorczyk, M.S.; Preston, K.R.; Dexter, J.E. Evaluation of Baking Procedures for Incorporation of Barley Roller Milling Fractions Containing High Levels of Dietary Fibre into Bread. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2008, 88, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinner, M.; Nitschko, S.; Sommeregger, J.; Petrasch, A.; Linsberger-Martin, G.; Grausgruber, H.; Berghofer, E.; Siebenhandl-Ehn, S. Naked Barley—Optimized Recipe for Pure Barley Bread with Sufficient Beta-Glucan According to the EFSA Health Claims. Journal of cereal science 2011, 53, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, R.; Fransson, G.; Tietjen, M.; Åman, P. Content and Molecular-Weight Distribution of Dietary Fiber Components in Whole-Grain Rye Flour and Bread. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2009, 57, 2004–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieder, A.; Holtekjølen, A.K.; Sahlstrøm, S.; Moldestad, A. Effect of Barley and Oat Flour Types and Sourdoughs on Dough Rheology and Bread Quality of Composite Wheat Bread. Journal of Cereal Science 2012, 55, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marklinder, I.; Johansson, L.; Haglund, Å.; Nagel-Held, B.; Seibel, W. Effects of Flour from Different Barley Varieties on Barley Sour Dough Bread. Food Quality and Preference 1996, 7, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambo, A.M.; Öste, R.; Nyman, M.E.-L. Dietary Fibre in Fermented Oat and Barley β-Glucan Rich Concentrates. Food Chemistry 2005, 89, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovaara, H.; Gates, F.; Tenkanen, M. Dietary Fibre Components and Functions; Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2007.

- Andersson, R.; Åman, P. 27 Cereal Arabinoxylan: Occurrence, Structure and Properties. Advanced dietary fibre technology 2008, 301. [Google Scholar]

- Comino, P.; Collins, H.; Lahnstein, J.; Gidley, M.J. Effects of Diverse Food Processing Conditions on the Structure and Solubility of Wheat, Barley and Rye Endosperm Dietary Fibre. Journal of Food Engineering 2016, 169, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, U.; Cummins, E.; Sullivan, P.; Flaherty, J.O.; Brunton, N.; Gallagher, E. Probabilistic Methodology for Assessing Changes in the Level and Molecular Weight of Barley β-Glucan during Bread Baking. Food Chemistry 2011, 124, 1567–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakha, A.; Åman, P.; Andersson, R. Characterisation of Dietary Fibre Components in Rye Products. Food Chemistry 2010, 119, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozer, N.; Poutanen, K. Fibre in Extruded Products. Fibre-Rich and Wholegrain Foods-Improving Quality 2013, 226–272. [CrossRef]

- Gajula, H.; Alavi, S.; Adhikari, K.; Herald, T. Precooked Bran-Enriched Wheat Flour Using Extrusion: Dietary Fiber Profile and Sensory Characteristics. Journal of Food Science 2008, 73, S173–S179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobota, A.; Sykut-Domańska, E.; Rzedzicki, Z. Effect of Extrusion-Cooking Process on the Chemical Compositon of Corn-Wheat Extrudates, With Particular Emphasis on Dietary Fibre Fractions. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2010, 60, 251–259. [Google Scholar]

- Vasanthan, T.; Gaosong, J.; Yeung, J.; Li, J. Dietary Fiber Profile of Barley Flour as Affected by Extrusion Cooking. Food Chemistry 2002, 77, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A.A.M.; Armö, E.; Grangeon, E.; Fredriksson, H.; Andersson, R.; Åman, P. Molecular Weight and Structure Units of (1→3, 1→4)-β-Glucans in Dough and Bread Made from Hull-Less Barley Milling Fractions. Journal of Cereal Science 2004, 40, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujral, H.S.; Sharma, P.; Rachna, S. Effect of Sand Roasting on Beta Glucan Extractability, Physicochemical and Antioxidant Properties of Oats. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2011, 44, 2223–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Gujral, H.S. Extrusion of Hulled Barley Affecting β-Glucan and Properties of Extrudates. Food and Bioprocess Technology 2013, 6, 1374–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M. Cereal Beta-Glucans: An Underutilized Health Endorsing Food Ingredient. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2022, 62, 3281–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebnitz, N.; Grunert, K.G. Impact of Self-Health Awareness and Perceived Product Benefits on Purchase Intentions for Hedonic and Utilitarian Foods with Nutrition Claims. Food Quality and Preference 2018, 64, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, P.J. Cereal β-Glucans in Diet and Health. Journal of Cereal Science 2007, 46, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeković, D.B.; Kwiatkowski, S.; Vrvić, M.M.; Jakovljević, D.; Moran, C.A. Natural and Modified (1→3)-β-D-Glucans in Health Promotion and Disease Alleviation. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2005, 25, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz de Erive, M.; He, F.; Wang, T.; Chen, G. Development of β-Glucan Enriched Wheat Bread Using Soluble Oat Fiber. Journal of Cereal Science 2020, 95, 103051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, A.-S.; Ryan, L.A.M.; Schwab, C.; Gänzle, M.G.; O’Doherty, J.V.; Arendt, E.K. Influence of the Soluble Fibres Inulin and Oat β-Glucan on Quality of Dough and Bread. European Food Research and Technology 2011, 232, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paula, R.; Abdel-Aal, E.-S.M.; Messia, M.C.; Rabalski, I.; Marconi, E. Effect of Processing on the Beta-Glucan Physicochemical Properties in Barley and Semolina Pasta. Journal of Cereal Science 2017, 75, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, C.L.; Aziz, N.A.A. Effects of Banana Flour and β-Glucan on the Nutritional and Sensory Evaluation of Noodles. Food Chemistry 2010, 119, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messia, M.C.; Oriente, M.; Angelicola, M.; De Arcangelis, E.; Marconi, E. Development of Functional Couscous Enriched in Barley β-Glucans. Journal of Cereal Science 2019, 85, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moza, J.; Gujral, H.S. Influence of Barley Non-Starchy Polysaccharides on Selected Quality Attributes of Sponge Cakes. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2017, 85, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaglione, P.; Lumaga, R.B.; Montagnese, C.; Messia, M.C.; Marconi, E.; Scalfi, L. Satiating Effect of a Barley Beta-Glucan–Enriched Snack. Journal of the American College of Nutrition 2010, 29, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, C.S.; Tudorica, C.M. Carbohydrate-Based Fat Replacers in the Modification of the Rheological, Textural and Sensory Quality of Yoghurt: Comparative Study of the Utilisation of Barley Beta-Glucan, Guar Gum and Inulin. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2008, 43, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raikos, V.; Grant, S.B.; Hayes, H.; Ranawana, V. Use of β-Glucan from Spent Brewer’s Yeast as a Thickener in Skimmed Yogurt: Physicochemical, Textural, and Structural Properties Related to Sensory Perception. Journal of Dairy Science 2018, 101, 5821–5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, B.; Patel, T. Increased Sensory Quality and Consumer Acceptability by Fortification of Chocolate Flavored Milk with Oat Beta Glucan. International Journal of Clinical and Biomedical Research 2016, 2, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Volikakis, P.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Vamvakas, C.; Zerfiridis, G.K. Effects of a Commercial Oat-β-Glucan Concentrate on the Chemical, Physico-Chemical and Sensory Attributes of a Low-Fat White-Brined Cheese Product. Food Research International 2004, 37, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santipanichwong, R.; Suphantharika, M. Carotenoids as Colorants in Reduced-Fat Mayonnaise Containing Spent Brewer’s Yeast β-Glucan as a Fat Replacer. Food Hydrocolloids 2007, 21, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, D.; Khatkar, S.K.; Chawla, R.; Panwar, H.; Kapoor, S. Effect of β-Glucan Fortification on Physico-Chemical, Rheological, Textural, Colour and Organoleptic Characteristics of Low Fat Dahi. Journal of Food Science and Technology 2017, 54, 2684–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsanhoty, R.; Zaghlol, A.; Hassanein, A. The Manufacture of Low Fat Labneh Containing Barley β-Glucan 1-Chemical Composition, Microbiological Evaluation and Sensory Properties. Current Research in Dairy Sciences 2009, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vithanage, C.; Mishra, V.K.; Vasiljevic, T.; Shah, N.P. Use of β-Glucan in Development of Low-Fat Mozzarella Cheese. Milchwissenschaft 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mykhalevych, A.; Polishchuk, G.; Nassar, K.; Osmak, T.; Buniowska-Olejnik, M. β-Glucan as a Techno-Functional Ingredient in Dairy and Milk-Based Products—A Review. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyly, M.; Salmenkallio-Marttila, M.; Suortti, T.; Autio, K.; Poutanen, K.; Lähteenmäki, L. Influence of Oat β-Glucan Preparations on the Perception of Mouthfeel and on Rheological Properties in Beverage Prototypes. Cereal Chemistry 2003, 80, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, S.; Wyrwisz, J.; Kurek, M.A. Comparative Analysis of the Physical Properties of o/w Emulsions Stabilised by Cereal β-Glucan and Other Stabilisers. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 132, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, N.; Xiong, Z.; Wang, G.; Xia, Y.; Lai, P.; Ai, L. Structural Characterization and Rheological Properties of β-D-Glucan from Hull-Less Barley (Hordeum Vulgare L. Var. Nudum Hook. f.). Phytochemistry 2018, 155, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelov, A.; Gotcheva, V.; Kuncheva, R.; Hristozova, T. Development of a New Oat-Based Probiotic Drink. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2006, 112, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harasym, J.; Suchecka, D.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J. Effect of Size Reduction by Freeze-Milling on Processing Properties of Beta-Glucan Oat Bran. Journal of Cereal Science 2015, 61, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, M.; Chen, J.; Chung, S.S.M.; Xu, B. A Critical Review on the Impacts of β-Glucans on Gut Microbiota and Human Health. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2018, 61, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avramia, I.; Amariei, S. Spent Brewer’s Yeast as a Source of Insoluble β-Glucans. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kim, S.; Liu, S.X. Effect of Purified Oat β-Glucan on Fermentation of Set-Style Yogurt Mix*. Journal of Food Science 2012, 77, E195–E201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahan, N.; Yasar, K.; Hayaloglu, A.A.; Karaca, O.B.; Kaya, A. Influence of Fat Replacers on Chemical Composition, Proteolysis, Texture Profiles, Meltability and Sensory Properties of Low-Fat Kashar Cheese. Journal of Dairy Research 2008, 75, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudorica, C.M.; Jones, T.E.R.; Kuri, V.; Brennan, C.S. The Effects of Refined Barley β-Glucan on the Physico-Structural Properties of Low-Fat Dairy Products: Curd Yield, Microstructure, Texture and Rheology. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2004, 84, 1159–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Application | Addition | Source | Product | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cereal processing | 2.5 and 5 % | barley | bread | [81] |

| Cereal processing | 0.2, 0.6, 1.0, and 1.4 % | barley | bread | [19] |

| Cereal processing | 10, 12, and 14 % soluble oat fiber (70% β-D-glucans) | oat | bread | [143] |

| Cereal processing | 2.6 and 5.6% | whey | bread | [144] |

| Cereal processing | 30% high-glucan barley flour | barley | pasta | [145] |

| Cereal processing | 10% | oat | yellow alkaline noodles | [146] |

| Cereal processing | 20 and 30% high-glucan barley flour | barley | couscous | [147] |

| Cereal processing | 100% barley flour (3.4-4.4% β-D-glucans) |

barley | sponge cake | [148] |

| Cereal processing | 5.2% | barley | biscuit bar | [149] |

| Milk processing | 0.5% | barley | yoghurt | [150] |

| Milk processing | 0.2-0.8% | yeast | yoghurt | [151] |

| Milk beverage production | 3% | oat | chocolate-flavored milk | [152] |

| Cheese production | 0.7 and 1.4% | oat | white-brined cheese | [153] |

| Cheese production | fat replacement 3.47% and 6.84% | yeast | cheddar cheese | [154] |

| Cheese production | 0.5% | barley | Dahi cheese | [155] |

| Cheese production | 5% | barley | Labneh | [156] |

| Cheese production | 0.2% | barley | mozzarella | [157] |

| Milk processing | 0.5% | cereal (not specified) | cottage cheese | [158] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).