1. Introduction

The wiring diagram of jaw-muscle activation during chewing has been studied extensively, yet the

in vivo control mechanism of jaw muscles of conscious subjects has remained an enigma [

1]. To chew the soft and hard parts of fruits-and-nuts-cake, instantaneous increase/decrease -adjusting of jaw muscle force is required. The nutty parts of a cake may even cause unexpected, unilateral jolts for the jaw-lever. Accidental encounter with a piece of bone in a mushy stew may cause tooth breakage or trauma for the jaw joints. The innate vigilance of our neural system does fairly good job in preventing tooth-fracture emergencies. The fracture of a tooth cusp or a broken filling is a costly, but relatively rare event, considered by most individuals and insurance companies an unpreventable “Act of God”.

The causative aetiologies of “bite-issue-emergencies” are considered obscure and unpredictable. The present-day consensus suggests the masticatory movements are caused by fast-conducting bilateral, corticobulbar fibers from the pre-central gyrus of the parietal lobe, the masticatory motor cortex [

2]. Special emphasis has been advocated to the dorsal part of brain stem, adjacent to the trigeminal nuclei, where astrocytes are postulated to contribute calcium-dependent rhythmogenic outputs resulting in repetitive open-close jaw-movement sequences of mastication [

3,

4]. Most dentistry textbooks vaguely explain mammalian mastication as “rhythmic, stereotyped activity of the jaw-closing and -opening muscles guided by the masticatory central pattern generator”. Since the pace of rhythmic masticatory movements are subject to variability, it is explained that the innate consistency of different food items “modulate the pace of mastication by peripheral sensory inputs”. However, the plausible mechanisms of this specific “peripheral sensory input modulation” remain to be explained satisfactorily. Placing a tongue blade between the anterior teeth (ANT) so that the back-tooth (BAT) contacts are prevented reduces the ability of a test subject for forceful jaw clenching [

5]. Lateral masticatory movements of jaw disclude the BAT contacts, while the guiding tooth-tooth-contacts become projected to the ANT-area. In result, instantaneous stalling of masseter and temporalis muscles is induced [

6,

7].

It is not quite clear why the original, bilaterally executed motor efferent feed for the rhythmic open-close activity of jaw muscles abruptly turns into unilateral reflex actions? Empty mouth jaw-closing without any tooth-food contacts is executed by bilateral muscle activity. The jaw-opening part of the chewing cycle is also executed by bilaterally equal amount of activity of jaw muscles. However, unilaterally located piece of food causes the activation of jaw-closing muscles from one side only, ipsilateral to the piece of food [

8]. The switching from centrally driven, bilateral jaw muscle activity to the unilateral mode of activity is extremely rapid and probably monosynaptic. The reflex response is exclusive for the working side jaw-closing muscles, and occurs within 12 milliseconds (ms) after a hard particle is placed between molars of laboratory animals [

9]. A part of the sensory inputs for rapid reflex deployment of jaw-elevator muscles are conveyed by primary afferent neurons (PAN), by stimuli from jaw-closing muscle spindles, another part of PAN-feed comes the ipsilateral side tooth mechanoreceptors. Accordingly, tooth contact stimulus is a trigger for unleashing jaw muscle force. Blocking the neural inputs from tooth mechanoreceptors by local anesthetic injections presents a risk of post-operative tooth-fractures for dental patients. Patients are warned not to chew anything until the anaesthesia has worn off. Real-time monitoring for unexpected tooth-contacts by PAN is essential for the control and reflex responses to the instantaneously changing and unpredictable kinematics of the jaw-lever during mastication.

The present review prospects the evolution of the neural control of the vertebrate jaw. Spatially precise and rapidly responding (preferably monosynaptic) reflex surveillance of oral peripheral sensory inputs was a necessity for the coherence of food-crushing of jawed vertebrates. Coincidental with the evolution of jaw, PANs and their respective peripheral sensor organs evolved to contribute for an innovative neural unit in the brain stem, the trigeminal mesencephalic ganglion (Vmes).

2. Review

2.1. The evolution of the triangular jaw

The jawless vertebrates with their sharp and caudally inclined teeth were inadequately prepared for the protective-thickness-amassing chitin-exoskeleton arms race of the Devonian seas. With relatively inefficient peristaltic pulsations of their circular mouth they were able to grasp, pierce, and swallow only the soft-skinniest of prey animals. They were probably slow to respond to unexpected soft-hard variabilities in the consistency of food, not to mention of controlling the “unwillingness-to-become-eaten-up-resistance” and the escape-potential of living prey. The cartilaginous rims of their circular mouth did not have the mechanical rigidity, nor neural feedback mechanism fast enough to target the available muscle force for cracking the weak spots of the body armour of e.g. trilobites. The jaw, evolving originally for Placoderms in the Silurian marine ecosystems some 430 million years ago, was a novel type of a “feeding limb”, a mechanic lever for crushing hard chitin shells.

The vertebrate lower jaw is a triangular appendage. The two rigid arms of the lower jaw are joined to the ventrolateral sides of the head by bilateral articulations. The rostral parts of the symmetrical jaw-arms are connected with a more or less rigid symphysis.

2.2. The food-crushing class 1 lever

The jaw muscles are often multipennated and attached to the rigid jaw-lever and its distant extensions enabling its force multiplication and movements to almost every possible direction.

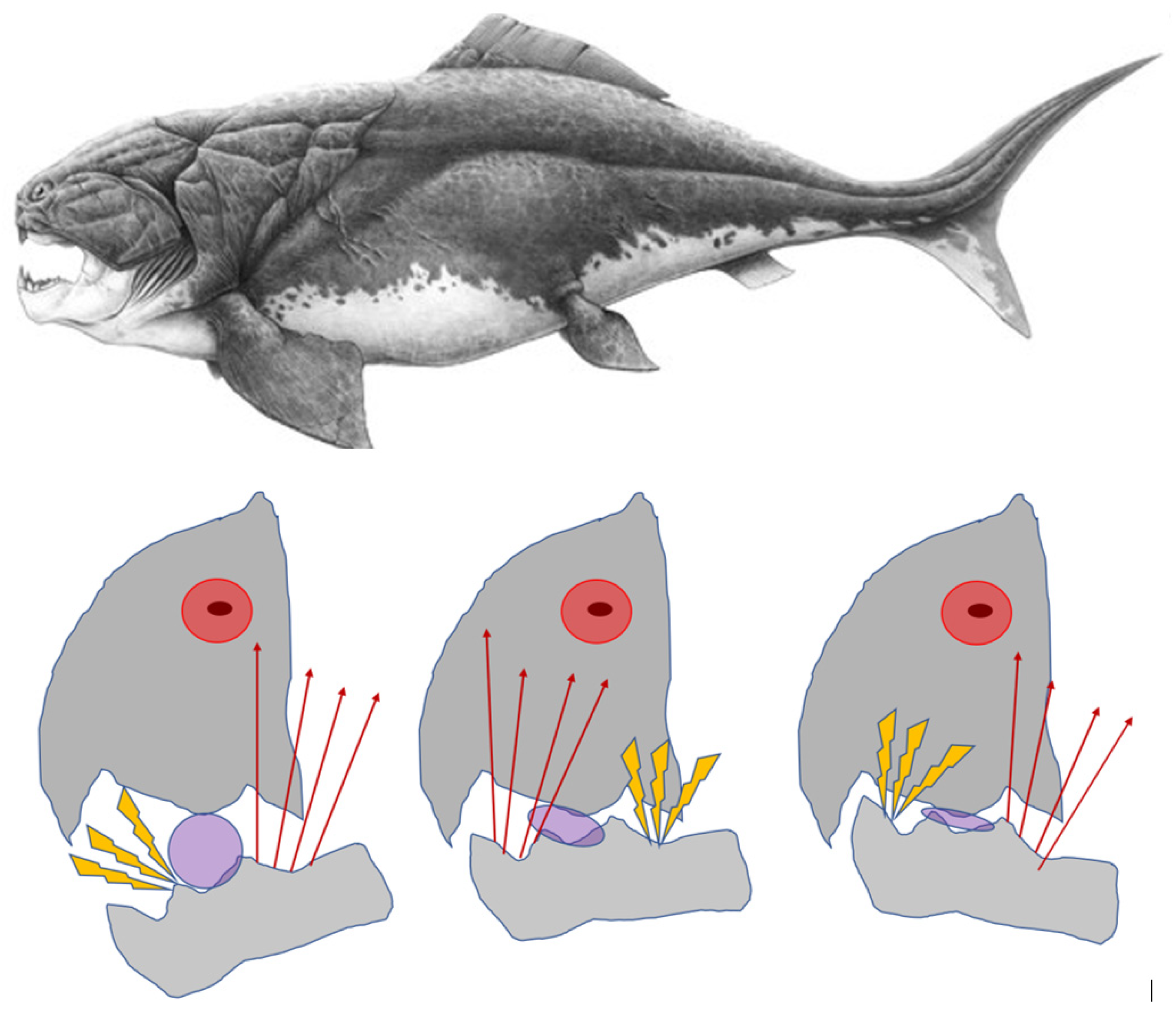

Figure 1 depicts a trilobite caught between the upper and lower jaw of

Dunkleosteus terrelli. The reciprocally alternating muscle force between the caudal and rostral ends of the jaw-lever targets the peak muscle force to the see-saw fulcrum, the hard piece of food, that can be randomly located between any of the three ends of the dental arches. All jaw-muscle force is very effectively subjected to a single bite point – nothing is wasted as reaction energy.

2.3. The caveats of powerful force-leverage

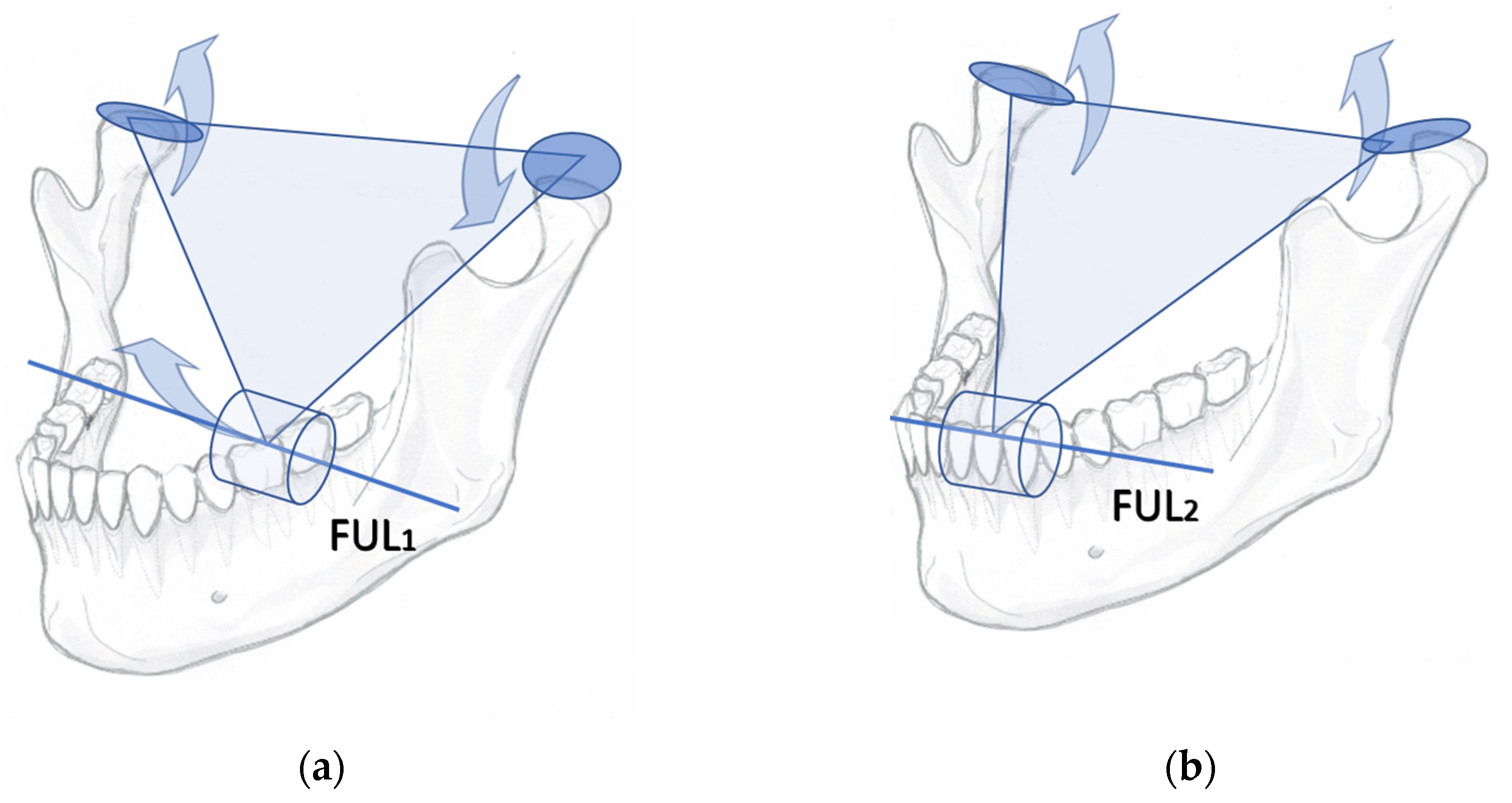

Any kind of powerful mechanical tool must be handled with caution. There are caveats for using the jaw-lever to multiply muscle force. Food-crushing with the jaw-lever may cause rapidly occurring, unexpected, and potentially harmful strains for the jaw-articulation and anterior teeth (

Figure 2).

Distraction and tearing of the articulation occur ipsilateral to the hard piece of food, while the contralateral jaw-joint might be forcefully compressed with the powerful jaw-arm-lever [

11]. Anterior teeth may be broken by the sudden leverage of an unfavourably placed food-particle-fulcrum in the BAT area. Therefore, the three ends of the triangularly arranged jaw-lever must be protected by short latency withdrawal reflexes.

2.4. The two parallel neural infrastructures for vertebrate jaw operations

The excitation and inhibition for circumoral, mouth-constricting muscles of early jawless vertebrates were conveyed by peripheral afferent inputs. The neural feed from PANs projecting from tactile receptors of the jawless mouth synapsed and crossed over to the midbrain to be further processed in the primitive forebrain pallium. In turn, reflex-like sets of sequenced synaptic spikes were produced in the pallium to be executed to the midbrain motor nuclei for repetitive and stereotyped rostro-caudally propagating pulsatory food-intake movements of oral muscles [

12]. Lampreys and hagfishes are the few jawless fish species remaining extant today. Their oromotor neural systems are also distinct from jawed vertebrates by the absence of Vmes and myelin [

13]. Without myelin, the conduction velocity of the reflex pathways of the early jawless verebrates were inadequate and slow to respond coherently to the instantaneous changes of the location, hardness and the amount of shattered food particles across and about the circular mouth.

The vertebrate jaw appears to have two parallel and alternating modes of neural control [

14]. The aforementioned, hemisphere-crossing pathway, is the original one that existed for jawless vertebrates. However, the central nervous system-driven feed appears to be temporarily overrun by independent and autonomous unilateral jaw-muscle reflexes.

2.5. The “shortcut” pathway for controlling unexpected jaw movements

For the jawed vertebrates, independent control of sensorimotor reflexes was required to monitor and control the separate proprioceptive tooth contacts and the stretching of the right and left side jaw-levering muscles. To accommodate the rapidly alternating excitatory and inhibitory needs of the jaw-levering muscles, a novel type of sensory ganglion was necessary for the autonomy of right- and left side reflexes, analogous to the spinal dorsal root ganglia (DRG) monitoring the independent reflex responses of bilateral fins and limbs. An “add-on proprioceptive supplement” was installed to the original vertebrate neural bauplan. The PAN from the two sides of teeth and jaw muscles were independently connected by the Vmes, a shortcut switch in the rostral part of midbrain. The Vmes evolved as the universal hallmark of jawed vertebrates to handle the rapidly changing and unexpected kinematics of the triangularly arranged jaw-lever, the symphysed pair of bilateral feeding limbs.

In result, jawed vertebrates have two distinct modes for the control of jaw movement, the fast one is there to surpass the slow one, when needed. The rapid increase of precisely targeted muscle force is delivered by ipsilaterally executed, rapid jaw-muscle reflexes mediated by Vmes, whereas the slow- responding, polysynaptic mode of jaw movement control is reserved for the more-or-less stereotyped cascades of low-force movement tasks.

An example of the bilaterally executed, polysynaptic mode of control is the jaw-opening-phase of an empty mouth. As there are no tooth-food contacts, opening an empty mouth does not require sensory monitoring of peripheral inputs. Swallowing, yawning, and the repeated initiations of the opening phases of masticatory cycle, as well as the closing phase of the jaw of an empty mouth, are also examples of the bilateral, polysynaptic and centrally-driven control-mode of jaw movement.

Should the upper and lower jaws happen to have something hard between teeth, the fast mode, mediated by Vmes, would instantly overrun and replace the slow mode of control of jaw muscle activity.

2.6. The simplified, dichotomous perspective on mammalian dental formulas

Dental occlusion is not a crash collision between upper and lower jaw, but a delicately guided sensorimotor process starting from the first contact of occlusion. Previously, I conducted a clinical study to demonstrating the qualitative difference of mandible-closure kinematics starting from an ANT contacts, as compared to jaw-closure dynamics for bites starting from a BAT area first contact. Bites starting from ANT contact stall the jaw-closure movement for some dozens of ms, while bites starting from BAT contacts are accelerated [

15]. Considering the anterior part of jaw is subject to potentially noxious strains by the forceful operations of the jaw-lever, it makes sense for the ANT to be equipped with a protective sensory infrastructure for inhibitory withdrawal reflexes, while excitatory PAN are needed for the BAT area. Accordingly, a tap on human incisor causes a short latency inhibitory silent period of the masseteric EMG activity, whereas a tap on a molar tooth rather causes rapid-onset excitatory activity of working side masseter muscle [

16,

17].

For mammaliform species, different types of teeth (incisors,canines premolars and molars) are positioned in the rostral and the caudal parts of dentition. The upper jaw dentition is a trinity of the embryonal prosencephalon-derived premaxillary ANT, whereas upper BAT, premolars and molars, are derived from the two sides of maxilla proper originating from the first branchial arch. The ANT of the human lower jaw symphysis, the incisors and canines, mostly occlude with the upper jaw incisors and canines only. Lateral masticatory excursions of human mandible may sometimes dispose for canine-premolar contacts, especially in worn down dentitions. Dentists refer to this condition as “lack of canine guidance”. The inadvertent tooth contacts between upper ANT and lower BAT, or vice versa, appears to be associated with a wide array of calamities and excessive wear for teeth and jaw-joints [

18,

19].

During embryonal ontogeny the incisor tooth primordia are developing in the symphyseal mesenchymal condensations, originating from cranial neural crest cells [

20]. Mandibular incisors (ANT) do not express the Barx1 homeobox gene, whereas Barx1-positivity characterizes molars [

21,

22,

23] and premolars of most mammals [

24]. The homeobox gene Barx1 is the general characteristic for BAT. The mechanisms of migration and axonal growth of neural cells towards the target sensory organs is not completely understood [

25]. Perhaps, the Barx1-negative gene-expression fenotypes of the primordia of ANT are enticing for the growth of the axons of inhibitory-fenotype PANs, while the mesenchymal primordial buds of Barx1-positive BAT would provide specific axonal growth cone cues for attracting excitatory type of PAN.

The rationale of different types of teeth of mammalian dental formulas could probably be dichotomized according to the functional properties of their PAN. Simply, there are two kinds of teeth, inhibition causing ANT and the exitatory BAT.

2.7. Improved velocity of reflexes

Coinciding with the first jawed vertebrates, myelin producing Schwann cells also appeared for the first jawed vertebrates to improve the conduction velocity between sensory receptors and motor efferent nerves of jaws and fins. The proprioceptive sensors acting within milliseconds of a proprioceptive stimulus were the

sine qua non for the neural infrastructure operating the unpredictable kinematics of food-crushing by jaw-lever. The stretching of muscles was perhaps sensed by the Piezo1 or Piezo2 type of calcium channel units [

26] or probably by the newly evolved muscle spindles [

27]. The overall rapidity of muscle-reflexes certainly was of great importance for the locomotion, especially for large-sized animal species, such as

Dunkleosteus, that are gigantic placoderms

, but the velocity of neural connections of their reflex actions were tantamount to control the unexpected, sudden kinematic tilts of their trilobite-cracking jaw-lever. Indeed, no evidence of myelin sheath can be demonstrated for fossils of the sister-clade of the same era, the jawless

Osteostraci [

28].

2.8. The sensory ganglia controlling jaw movements.

The mechanoreceptors of the periodontal ligament of mammalian teeth (pmr) are important proprioceptive sensors providing essential information to control jaw-operations. Interestingly, these “tooth-contact-sensors” have two different pathways to the motor efferent neurons of the jaw-muscles. For the vertebrate jaw, two main sensory ganglia and two fenotypes of PAN are operational. The Vmes houses the perikarya of PAN-Mes-fenotype of neurons, and the trigeminal ganglion (TG) houses the cell bodies of PAN-TG- fenotype of neurons. The TG and Vmes together are the exclusive and the only ganglia to collect the primary afferent neural inputs from the pmr of mammalian teeth. This kind of dual-pathway sensory arrangement of tooth-contact information (either PAN-TG-pmr, or PAN-Mes-pmr) may seem curious. The TG-based neurons (PAN-TG-pmr) have di- or polysynaptic connections with jaw-muscle efferents, whereas the other pathway (PAN-Mes-pmr) is a direct monosynaptic connection by the Vmes -based PAN [

29,

30,

31].

The outgoing axons of PAN-TG-pmr-fenotype submit neural feed from tooth contacts

via synapses in the midbrain sensory nuclei crossing over to the opposite hemispheres of brain stem and the sensory cortex. The PAN-TG-pmr neural pathway appears to be the original mode of vertebrate proprioceptive information conveyed to the “masticatory-pallium”. The PAN-TG-pmr don’t have direct, monosynaptic connections with motor efferent neurons of the jaw muscles, while the PAN-Mes-pmr do [

30,

31,

32].

The neurochemical properties of TG and its cells are distinct from the cells of VMes ganglia. Both ganglia house an heterogenous array of many different cell-types. In addition to the PAN-TG neurons, TG has many different types of cells, satellite glial cells, fibroblasts and macrophage-like cells [

32,

33]. The differences between PAN cells can be identified by the axonal vesicle contents. The PAN-TG can express wide array of peptide neurotransmitters, such as calcitonin-gene-related peptide, Substance P, et.c [

33], with tissue morphogenetic functions. In distinction to the PAN-TG, the PAN-Mes neurons don’t express any peptide neurotransmitters [

34]. For the present text, I chose to consider the PAN-Mes “functionally more oriented for executing rapid reflexes”, as compared to PAN-TG. I postulate the PAN-Mes-mediated primary afferent neural feed for the motor efferent neurons of jaw muscles is monosynaptic, therefore of more relevant importance for the control of the unpredictable and rapidly developing kinematic events of the vertebrate jaw.

2.9. The coupling of spindle and pmr-inputs in Vmes

In the Vmes, two different kinds of PAN-Mes sensory neurons communicate. The PAN-Mes-sp and PAN-Mes-pmr convey information from two important sources. The two sources of proprioceptive information are from:

Muscle stretching, conveyed by PAN-Mes-sp neurons;

Tooth-contact-sensing mechanoreceptors, conveyed by PAN-Mes-pmr neurons.

At the instant of tooth contacting with solid food, both kinds of neural inputs are delivered almost simultaneously to Vmes. The axons and cell bodies of PAN-Mes-sp and PAN-Mes-pmr neurons are brought into physical proximity with each other. In my opinion this is in order for the PAN-Mes-sp and PAN-Mes-pmr to communicate with each other. The within Vmes interplay between these two types of neurons does not necessarily need to be intra-axonal synaptic transmission, but probably conveyed by direct (and rapid), electrical gap-junction connections [

35,

36].

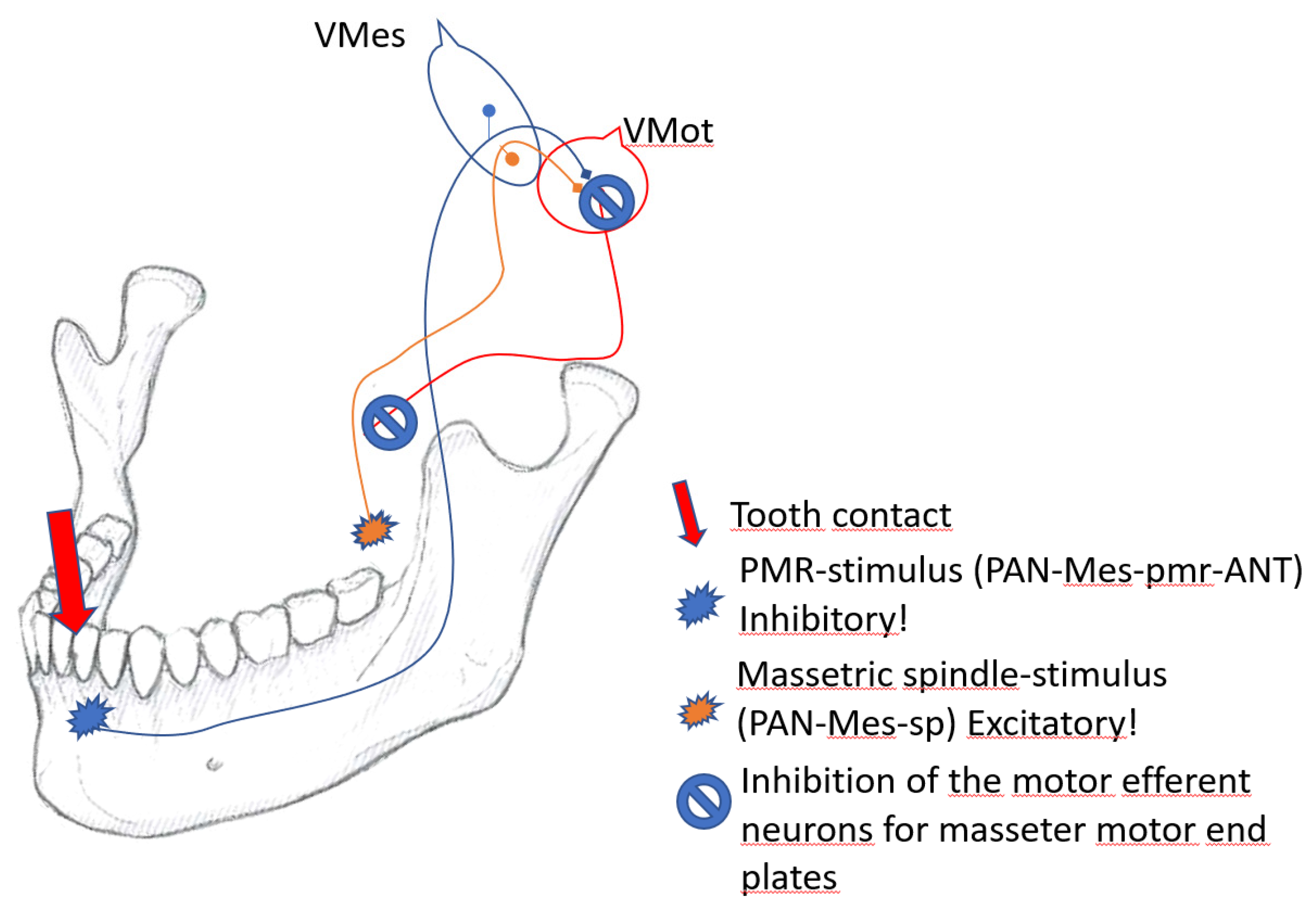

Figure 3 illustrates the “presynaptic coupling phenomenon”. Vmes is the control panel of the on-off switches for each of the differentially directed force vectors of the jaw-closing muscle units. Jaw-muscle motor efferent neurons are not fully functional unless for simultaneous inputs from both muscle-stretching, and mechanoreceptor sources. The simultaneous feed from both sources is probably essential for generating proper masticatory force. In the absence of proprioceptive neural inputs from the pmr the masticatory performance is reduced, as shown for dental patients with all their natural teeth missing and replaced by titanium implants [

37].

2.10. The pin-point targeting of muscle force

The PAN-Mes-sp are needed to answer the question: “Whereabout the dental arch triangle is the hardest part of food?” Those motor units that are being stretched most by the “hard-part-of food-fulcrum” are taut and send monosynaptic firing for the homonymous motor efferent neurons

via Vmes. The stretching of jaw muscle spindles is the condition that reveals which ones of the multipennate temporalis motor units are needed to operate the triangular jaw-lever to crush that specific, hard piece of food (

Figure 4).

2.11. The switch for the inhibitory withdrawal of muscle force

Vmes is the control panel of jaw muscle activity, where the PAN-Mes-sp and PAN-Mes-pmr neurons communicate with each other. Before executing their simple, monosynaptic commands both PAN-Mes-sp and the PAN-Mes-pmr neuron must be in mutual agreement: “Is it OK to direct jaw-muscle force for this specific whereabout at this very instant?” If not, a “power-off switch” is available to protect the rostral tip of the jaw, and the jaw-joints from accidental, excessive force-multiplication by jaw-lever.

The pmr are only firing for the specific tooth, where the piece of food is. This feedback is monosynaptic, and conveyed by PAN-Mes-pmr to the motor efferent neurons of jaw-closing muscles. Should the spatial location of the jaw-lever-fulcrum happen to be on the BAT, the perikarya, or the axonal part of the PAN-Mes-sp, also located in the Vmes, receives the presynaptic “go active” permission, by connection from the adjacent, excitatory fenotype PAN-Mes-pmr-BAT neuron. The two sources of excitatory inputs are in agreement.

However, the ANT-connected PAN-Mes-pmr-ANT are not excitatory, but they are storing inhibitory synaptic mediators in their axon terminal vesicles, unlike the excitatory axonal endings of PAN-Mes-sp, and PAN-Mes-pmr-BAT. As the PAN-Mes-pmr inputs come from the rostral end of the jaw-lever, from ANT contacts (PAN-Mes-pmr-ANT), a withdrawal reflex ensues. The PAN-Mes-pmr-ANT send a direct, monosynaptic, and inhibitory signal to the motor efferent neurons. A silent period of several dozens of ms follows and the motor efferent neurons cannot execute their mission. Furthermore, there may be primary afferent depolarization inhibition going on between the axons of inhibitory PAN-Mes-pmr-ANT and the excitatory PAN-Mes-sp, within Vmes (

Figure 5).

3. Conclusion. The unilateral food-crushing reflex (UFCR) hypothesis

The UFCR is the underlying characteristic that manifests in the exorbitantly varied anatomical diversities of the extinct and extant vertebrate jaws demonstrating the natural history of feeding habits of our clade.

The tooth-contact-elicited afferent neural inputs from ANT periodontal mechanoreceptors to the motor efferent neurons of jaw muscles are inhibitory, whereas that from the BAT are excitatory. Masticatory tooth contacts from ANT negates the concomitant excitatory feed from jaw-muscle spindles that have become stretched by the same tooth contact. Conversely, masticatory tooth contacts from BAT are excitatory to summate and potentiate the excitatory feed from the stretched jaw muscle spindles. The PAN-feed from spindle and tooth-contact sources are coupled to communicate with each other by interactive presynaptic connections in the Vmes.

In order to crack the hard parts of their diet, the first branchial arch of pre-gnathostomes stiffened to evolve into more rigid jaw-arms [

38]. Force-leverage and the complicated kinematics of the symphysis-connected bilateral jaw-arms necessitated autonomous control of the neural afferent-efferent feed for left and right side of the jaw. Therefore, Vmes, analogous to the DRG, evolved for jawed vertebrates [

39]. In result the original, peristaltic food-intake mechanisms of the vertebrate mouth remained, but were supplemented with the evolutionary novelty, the food-crushing plug-in gadget. The jaw itself is the hardware, the Vmes is its’ microchip. The Vmes and the triangular jaw-lever has been around for some 430 million years to monitor the food intake and to switch on the jaw-muscle force to be dispensed whenever anything harder than water is caught between teeth. Understanding the evolution of vertebrate jaw, and its neural control should open prospects for systematic assessment of the causal conditions for “bite-issue-emergencies”. In the future, perhaps, a fractured tooth cusp will be classified as a preventable disease-entity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization; methodology; writing LV. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to my friend Pertti O Väisänen (Chairman, PalMedical OÜ, Estonia) for reading the final versions of this review and for his constructing comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Türker KS. Reflex control of human jaw muscles. (2002) Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 13:85-104. [CrossRef]

- Nordstrom MA. (2007) Insights into the bilateral cortical control of human masticatory muscles revealed by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Arch Oral Biol. 52:338-42. [CrossRef]

- Morquette P, Lavoie R, Fhima MD, Lamoureux X, Verdier D, Kolta A. (2011) Generation of the masticatory central pattern and its modulation by sensory feedback. Prog Neurobiol. 96:340-55. [CrossRef]

- Montalant A, Carlsen EMM, Perrier JF. Role of astrocytes in rhythmic motor activity. (2021) Physiol Rep. 9(18):e15029. [CrossRef]

- Forrester, S.E., Allen, S.J., Presswood, R.G., Toy, A., & Pain, M.T. (2010). Neuromuscular function in healthy occlusion. J Oral Rehabil, 37: 663-9. [CrossRef]

- Manns, A., Chan, C., & Miralles, R. (1987). Influence of group function and canine guidance on electromyographic activity of elevator muscles. J Prosthet Dent, 57: 494-501. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, E.H., & Lundquist, D.O. (1983). Anterior guidance: its effect on electromyographic activity of the temporal and masseter muscles. J Prosthet Dent, 49: 816-23. [CrossRef]

- Gorniak GC, Gans C. (1980) Quantitative assay of electromyograms during mastication in domestic cats (Felis catus). J Morphol. 163: 253-81. [CrossRef]

- Lavigne G, Kim JS, Valiquette C, Lund JP. (1987) Evidence that periodontal pressoreceptors provide positive feedback to jaw closing muscles during mastication. J Neurophysiol 58:342-58. [CrossRef]

- Ferrón HG, Martínez-Pérez C, Botella H. (2017). Ecomorphological inferences in early vertebrates: reconstructing Dunkleosteus terrelli (Arthrodira, Placodermi) caudal fin from palaeoecological data. PeerJ 5:e4081 . [CrossRef]

- Greaves, WS. (1978) The jaw lever system in ungulates: a new model. J. Zool., Lond. 184: 271-285. [CrossRef]

- Suryanarayana SM, Robertson B, Grillner S. (2022) The neural bases of vertebrate motor behaviour through the lens of evolution. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 14: 377(1844):20200521. [CrossRef]

- Marie-Theres Weil, Saskia Heibeck, Mareike Töpperwien, Susanne tom Dieck, Torben Ruhwedel, Tim Salditt, María C. Rodicio, Jennifer R. Morgan, Klaus-Armin Nave, Wiebke Möbius, Hauke B. Werner. (2018) Axonal Ensheathment in the Nervous System of Lamprey: Implications for the Evolution of Myelinating Glia. Journal of Neuroscience 38: 6586-6596. [CrossRef]

- Rokx J, Jüch P, van Willigen J. (1985) On the bilateral innervation of masticatory muscles: a study with retrograde tracers. J Anat 140: 237-243.

- Vaahtoniemi L. (2020) The reciprocal jaw-muscle reflexes elicited by anterior- and back-tooth-contacts-a perspective to explain the control of the masticatory muscles. BDJ Open. 6: 27. [CrossRef]

- Brinkworth RS, Türker KS, Savundra AW. (2003) Response of human jaw muscles to axial stimulation of the incisor. J Physiol. 547: 233-45. [CrossRef]

- Brinkworth RS, Male C, Türker KS. (2004) Response of human jaw muscles to axial stimulation of a molar tooth. Exp Brain Res. 159: 214-24. [CrossRef]

- Kerstein, R.B., & Farrell, S. (1990). Treatment of myofascial pain-dysfunction syndrome with occlusal equilibration. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry, 63: 695-700 . [CrossRef]

- Thumati, P., & Thumati, R.P. (2016). The effect of disocclusion time-reduction therapy to treat chronic myofascial pain: A single group interventional study with 3 year follow-up of 100 cases. The Journal of the Indian Prosthodontic Society 16: 234 - 241. [CrossRef]

- Mina M. Regulation of Mandibular Growth and Morphogenesis. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology & Medicine. 2001;12(4):276-300. [CrossRef]

- Miletich, I., Yu, W-Y., Zhang, R., Yang, K., Caixeta de Andrade, S., Pereira, S. F. D. A., Ohazama, A., Mock, O. B., Buchner, G., Sealby, J., Webster, Z., Zhao, M., Bei, M. & Sharpe, P. T., (2011) Developmental stalling and organ-autonomous regulation of morphogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108, 48, p. 19270–19275. [CrossRef]

- Tucker, A., Sharpe, P. (2004). The cutting-edge of mammalian development; how the embryo makes teeth. Nat Rev Genet 5: 499–508. [CrossRef]

- Tucker A, Matthews K, Sharpe P (1998) Transformation of Tooth Type Induced by Inhibition of BMP Signaling. Science 282: 1136-1138. [CrossRef]

- Wakamatsu, Y., Egawa, S., Terashita, Y. et al. (2019) Homeobox code model of heterodont tooth in mammals revised. Sci Rep 9, 12865. [CrossRef]

- Igarashi M. (2019) Molecular basis of the functions of the mammalian neuronal growth cone revealed using new methods. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 95: 358-377. [CrossRef]

- Lin Y, Ren J, McGrath C. (2022) Mechanosensitive Piezo1 and Piezo2 ion channels in craniofacial development and dentistry: Recent advances and prospects. Front Physiol. 13:1039714. [CrossRef]

- Maeda N, Miyoshi S, Toh H. (1983) First observation of a muscle spindle in fish. Nature. 302(5903):61-2. [CrossRef]

- Zalc B, Goujet D, Colman D. (2008) The origin of the myelination program in vertebrates. Curr Biol. 18:R511-2. [CrossRef]

- Byers M, Dong W. (1989). Comparison of trigeminal receptor location and structure in the periodontal ligament of different types of teeth from the rat, cat, and monkey. J Comp Neurol 279: 117-127. [CrossRef]

- Linden R, Scott B. (1989) Distribution of mesencephalic nucleus and trigeminal ganglion mechanoreceptors in the periodontal ligament of the cat. J Physiol 410: 35-44. [CrossRef]

- Hassanali J. (1997) Quantitative and somatotopic mapping of neurones in the trigeminal mesencephalic nucleus and ganglion innervating teeth in monkey and baboon. Arch Oral Biol. 42: 673-82. [CrossRef]

- Messlinger K, Russo AF. (2019) Current understanding of trigeminal ganglion structure and function in headache. Cephalalgia. 39: 1661-1674. [CrossRef]

- Messlinger K, Balcziak LK, Russo AF. (2020) Cross-talk signaling in the trigeminal ganglion: role of neuropeptides and other mediators. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 127:431-444. [CrossRef]

- Lazarov NE. (2002) Comparative analysis of the chemical neuroanatomy of the mammalian trigeminal ganglion and mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus. Prog Neurobiol. 66: 19-59. [CrossRef]

- Baker R, Llinás R. (1971) Electrotonic coupling between neurones in the rat mesencephalic nucleus. J Physiol. 212:45-63. [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Prado N, Hoge G, Marandykina A, Rimkute L, Chapuis S, Paulauskas N, Skeberdis VA, O'Brien J, Pereda AE, Bennett MV, Bukauskas FF. (2013) Intracellular magnesium-dependent modulation of gap junction channels formed by neuronal connexin36. J Neurosci. 33:4741-53. [CrossRef]

- Homsi G, Kumar A, Almotairy N, Wester E, Trulsson M, Grigoriadis A. (2021) Assessment of masticatory function in older individuals with bimaxillary implant-supported fixed prostheses or with a natural dentition: A case-control study. J Prosthet Dent. 6:S0022-3913(21)00494-7. [CrossRef]

- Jon Mallatt, (1996) Ventilation and the origin of jawed vertebrates: a new mouth, Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 117: 329–404. [CrossRef]

- Sato K. (2021) Why is the mesencephalic nucleus of the trigeminal nerve situated inside the brain? Med Hypotheses. 153:110626. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).