Introduction

For several combined reasons, cross-cultural mobility is an increasingly salient phenomenon. In recent years, we have been experiencing a historical change at the global level in displacement events at different geographic scales. International Organization for Migration (2022) estimates that were around 281 million international migrants in the world in 2022, which equates to 3.6 percent of the global population. Current mobility has different characteristics from those observed in other historical moments: forced displacements have consolidated themselves as a growing trend in the context of international human mobility (e.g., environmental pressures, economic disparities, political oppression, war); regional and global free-trade arrangements encourage international marketing and international recruitment of skilled personnel (Rudmin, 2003); liberal political ideologies of dominant developed nations cause their governments, their minorities, and their academics to attend to acculturative rights and remediations; the rise of disinformation about migration has spread myths on mobility (International Organization for Migration, 2022).

For conceptual clarification, we will use the term mobility instead of migration, as there is a distinction between movement – the act of displacement between locations – and mobility – the dynamic equivalent of place and, therefore, imbued with meaning – (Cresswell, 2006). The notion of migration is a more restricted concept for the range of types, directions, durations, and human movement patterns. Therefore, transnational mobility refers to people acting, making decisions, and developing subjectivisms and identities embedded in networks of relationships that connect them to two or more Nation-states. Yet, cross-cultural mobility exceeds the Westphalian concept and can be performed outside the country's borders (e.g., globally, regionally) or within the same country in different cultural areas (e.g., Brazilian North, Northeast, Central-West).

Different terms have described the psychological and behavioural process of cross-cultural mobility. According to the American Psychological Association (APA), in 2003, the term cultural assimilation became obsolete, was removed from all records, and replaced with acculturation (VandenBos, 2015). The Dictionary of Race, Ethnicity and Culture defines acculturation as the processes of transformation and adaptation which take place within cultures when two or more groups – each of which has specific cultural and behavioural models – enter into relations with one another. Psychological research on this subject has highlighted its adverse outcomes, referred to as acculturation stress (Berry, 2006). Nevertheless, we propose that it is paramount to carry out an additional revision in the terminology as the concept of reported has been overcome in anthropology and social sciences since the 1940s and 1950s.

In 1936, the Social Science Research Council presented three outcomes of the acculturation process (acceptance, adaptation, and reaction) (Redfield et al., 1936) in the Memorandum for the Study of Acculturation. Subsequently, the debates centered on the idea that no culture is only giving or receiving; acculturation never is produced in one way (Cuche, 2016). Researchers began to conceive the process in a broader debate (Dorsinfang-Smets, 1961). For this reason, it was proposed the term culture inter-crossing, a fruitful cultural synthesis or hybridity when the person transforms the culture where he arrives.

Culture is always under construction. In that sense, the word acculturation has a limited scope since the contact between two or more cultures is more comprehensive than assimilation, integration, adaptation, or rejection. It is a mutual construction process that involves psychological, social, cultural, and environmental factors. Recent research has identified positive aspects which lead to healthy adjustment and integration in the host, and resilience as pivotal for successful adaptation (Keles et al., 2018). Consequently, we will use the expression cross-cultural mobility adaptation process instead of acculturation.

Different terminologies have been adopted to describe the cross-cultural mobility adaptation process. For example, culture shock is used to make reference to a variety of symptoms (e.g., anxiety, helplessness, excessive fear of being cheated, longing to be back home) that commonly is experienced in the process of adaptation to cultural stress. Other authors preferred alternative terms: language shock, as a fundamental element because it is in the language domain where many of the cues to social relations lie; cultural fatigue to describe symptoms such as irritability, impatience, depression, loss of appetite, poor sleep, and vague physical complaints, and stress.

Therefore, some individuals exhibit stress symptoms when in contact with other cultures or as a part of the adaptation process. Recently, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – DSM-V includes the Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorders category, in which the adjustment disorder’s criteria determines: the presence of emotional or behavioural symptoms in response to an identifiable stressor (Criterion A); these symptoms or behaviors are clinically significant (e.g., marked distress out of proportion to the severity or intensity of the stressor; impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning) (Criterion B); and the development of emotional or behavioural symptoms occurs within three months in response to an identifiable stressor(s) (Criterion C) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

According to American Psychiatric Association (2013), the stressors may be single or multiple (e.g., employment difficulties and security problems), recurrent (e.g., associated with seasonal crises), or continuous (e.g., a persistent painful condition). Stressors may affect a single individual, an entire family, or a larger group or community (e.g., forced migration). Adjustment disorders may be diagnosed following a ‘perceived’ stressful event when grief reactions intensity, quality, or persistence exceed what we expect and when we consider cultural, religious, or age-appropriate norms (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Noteworthy, recent research focuses on the subjective appraisal of life stress rather than on objective measures of the impact of life events (e.g., Lazarus and Folkman, 1984; Hewitt et al., 1992). Therefore, the new trend does not measure the frequency or presence of specific stressful circumstances – stressors – but the degree to which individuals appraise situations in their lives as stressful.

Cross-cultural mobility stress (CCMS) is a broader concept that goes beyond adjustment disorder stressors. The most objective standard explaining stress is the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (TMSC) (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). In a nutshell, TMSC defines stress as a particular relationship between the person and the environment (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). The variables of the model are stress, appraisal, and coping. There are three types of stressors: significant changes (often catastrophic), changes affecting one or a few individuals, and daily hassles. The appraisal is the process that elicits emotions from an individual subjective interpretation or evaluation of important events or situations. Coping is constantly changing cognitive and behavioural efforts to manage specific external or appraised internal demands (stressors) as taxing or exceeding the person’s resources (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

As with other forms of stress, CCMS carries positive (e.g., eustress) and negative (e.g., distress) connotations, but it has some specific characteristics. As proposed by TMSC, CCMS is a transactional process, that is, a relationship between the person and the environment. The appraisal of environmental events also is central to the manifestation of CCMS. The changes related to mobility are personally significant because they are interpreted as threats to well-being or as harm or loss potentials that require psychological, physiological, or behavioural efforts to manage the external and internal events and their outcomes.

However, CCMS has distinctive features from stress in general. The ability to deal with challenges (Bashir & Khalid, 2020), difficulties, conflicts, demands (Joiner & Walker, 2002), or events on the cross-cultural mobility adaptation process – before, during, and after the mobility (Merced et al., 2022) – is essential in that one type of stress.

By analogy, it is possible to consider that CCMS is the physiological (e.g., palpitations, sweating, dry mouth) or psychological (e.g., anxiety, dysthymia, excitement) responses to internal or external stressors (VandenBos, 2015) or stress sources (Basáñez et al., 2014). It Affects nearly every body system and influences how people feel and behave (VandenBos, 2015). CCMS varies depending on the differences between cultures (Castro-Olivo et al., 2014; Dokoushkani et al., 2019; Lueck & Wilson, 2010) and occurs when these experiences can produce a change in health status, including psychological, somatic, and social aspects (Berry, 2006), and a decrease in psychological well-being (Lueck & Wilson, 2010).

CCMS variables include social customs, language preference, age at the time of migration, years of residence in the host culture, income levels, ethnic networks, family extendedness, and perceptions of prejudice (Lueck & Wilson, 2010). Cognitive appraisal, situational properties, and attributions are elements of the stress process (Vitaliano et al., 1993), and the main factors are the appraisals of personal relevance (salience) and control; stressor properties (novelty, duration, and predictability); and self-attribution (causality) (Vitaliano et al., 1993).

CCMS tolerance is the level of either (a) one’s unwillingness to experience emotional distress as part of pursuing desired goals or (b) one’s inability to engage in goal-directed behaviors (adjustment or coping strategies) when experiencing distress. Low distress tolerance is related to a disorders range (e.g., substance abuse, eating disorders) (VandenBos, 2015).

This study performed a systematic literature review to analyze the CCMS measures presenting its internal structure. The specific objectives were: 1) to identify the former acculturation and acculturative stress definitions adopted by the studies, 2) to describe the size of the measure items pool, 3) to list their factor organization, 4) to recognize if the measure evaluates acculturative stress or merely a part of it, 5) to list the measure type (Likert, etc.), 6) to identify the target audience, 7) to present the type of factor analysis used to obtain validity evidence based on internal structure, and 8) to identify its evidence of validity.

Method

Research Design

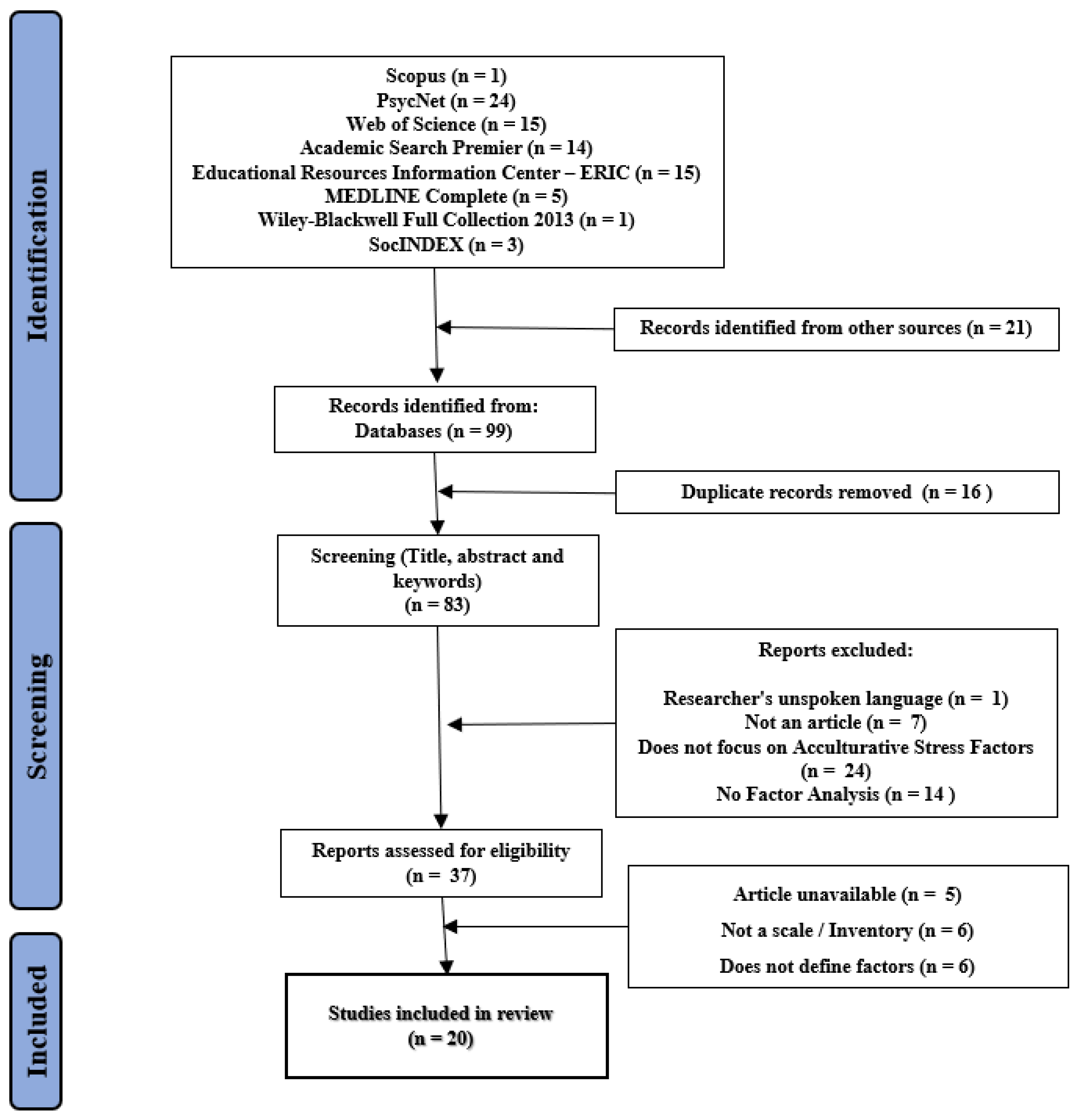

The research followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) (Page, McKenzie, et al., 2021), more specifically the extension for scoping reviews.. A systematic literature review serve many critical roles (e.g., provide syntheses of the state of knowledge in a field; address questions that otherwise could not be answered by individual studies; identify problems in primary research that should be rectified in future studies; generate or evaluate theories about how or why phenomena occur) (Page, McKenzie, et al., 2021) The general process steps for the review are identification, screening, and inclusion.

Data Collection and Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion step was performed in January 2023. The studies to be included in the study were retrieved from the following electronic library databases (which traditionally index searches in the field of psychology, sociology, and education): Scopus, PsycNET, Web of Science, Academic Search Premier, ERIC, Medline, Wiley-Blackwell and SocINDEX – with no restriction on earliest search date and location. Additionally, we limited searches to the title, abstract, and keywords using the following search strategy: ("acculturative stress" AND "factor analysis"). Additionally, we included other articles identified from other sources (e.g., articles known by the researchers, and articles retrieved from references).

We adopted the following inclusion criteria: (1) to be scientific articles in English, Spanish, Portuguese, French or German (researcher's spoken languages); (2) that focus on acculturative stress; and (3) that used factor analysis as a methodology. We also excluded duplicate papers in the screening step. To avoid false-positives, we screened only the titles, abstracts, and keywords to identify articles that we read in full at the inclusion step. The process of screening, and inclusion of relevant articles was carried out by two independent judges: a professor, and a doctoral.

Data Analysis

We performed a content analysis of the acculturation and acculturative stress definitions adopted by the studies. This qualitative analysis was also used to categorize the evidence of validity presented for the measures, the stress dimensions, and the factors.

In a complementary way, we calculated descriptive statistics. We used only counting (n), frequencies (f) and percentages (%).

Results

After using the PRISMA, 20 articles were included in the final corpus analysis (

Figure 1). These texts report research on 16 acculturative stress measures (

Table 1).

All measures were Likert type: 4-point (n = 4; 25%), 5-point (n = 11; 68.75%), 6-point (n = 1; 6.25%). These instruments were applied in a variety of target audiences: Latinx immigrants in the USA, north Indian students, adult Hispanic immigrants, Chinese mainland students in Hong Kong, Iranian students, Hispanic children, Chinese college students, Chinese international students, international students enrolled in the United States, Pakistani Muslim students, culturally and linguistically diverse adolescents, Hispanic young adults, Asian American undergraduates attending a large West Coast university, bi-cultural individuals attending the same West Coast university, Colombian and Peruvian migrants living in Chile, mainland Chinese postgraduate students who were studying in Hong Kong, Latino middle school students, Latino and Asian Americans, Turkish people, Latin-American immigrants, Pakistani adult immigrants, senior Asian Indian women immigrants in Australia, Chinese-Americans living in the United States, international graduate students, and individuals currently living in the United Kingdom, Germany, the United States, China, or India.

The articles used exploratory factor analysis (n= 6; 30%) and confirmatory factor analysis (n = 2; 10%) as a statistical technique to obtain evidence of validity based on internal structure. Most of then used both techniques (n = 12; 60%).

To obtain some types of validity evidence based on relations to other variables to the acculturative stress measures, they included: the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985), Acculturation Attitudes Measure (Berry, 2006), Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, Social Support Questionnaire, and Daily Hassles Questionnaire.

In consonance with the APA Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing classification, some articles present criterion-related validity, more specifically concurrent validity (n = 3; 15%), content validity (n = 1; 5%), and construct validity (n = 2; 10%) for the measures. Other forms of validity evidence are also presented: concurrent validity (n = 3; 15%), divergent validity (n = 3; 15%), nomological validity (n = 1; 5%), and unspecified validity (n=1; 5%). Some articles (n = 5; 25%) do not report evidence of validity for the measurements but stress that they are necessary.

From the 424 items used in the acculturative stress measures (

Table 1), 262 (61.79%) are committed to stressors, 151 (35.62%) to cognitive appraisal, and 11 (2.59%) to coping. The instruments do not assess the symptoms.

Table 2 shows the factor organization, acculturative stress definitions, and the number and type of items (stressors, appraisal, coping, and symptoms). From the 85 factors that compose the internal structure of the measures, a content analysis identified that 23 (27.05%) are related to cultural stressors (e.g., preferred culture conflicts), 16 (18.82%) to language stressors (e.g., language difficulties), 10 (11.76%) to discrimination stressors (e.g., perceived discrimination), 8 (9.41%) to cognitive appraisal (e.g., threat, fearfulness), 7 (8.23%) to relationship stressors (e.g., intercultural relations), 4 (4.70%) to homesickness, 4 (4.70%) to academic stressors (e.g., academic pressure), 4 (4.70%) to work stressors (e.g., work challenges), and 2 (2.35%) to coping (e.g., making positive sense of adversity). The remaining factors (n = 7; 8.23%) are related to a variety of different stressors (e.g., family, religion, food consumption).

We highlight that, from the 20 articles analyzed, 8 (40%) used Berry´s acculturation definition, that is, a process of change experienced by individuals of a racial and ethnic minority group during the adoption of the culture of the majority group (Berry, 2006). There are 5 (25%) texts that do not even define acculturation, and the classical – and obsolete definition that states to be a group-level phenomenon, which occurs when two cultures come into continued direct contact (Redfield et al., 1936) – is present in 4 (20%) of the texts. Additionally, other possible aspects of acculturation are also present (n = 3; 35%), such as learning [e.g., acculturation into a country involves learning aspects of a new culture, including learning a new language, value system, and norms (Merced et al., 2022); it suggests that people from different cultural backgrounds who come to a new culture for a short or long-term stay may experience adaptations and changes related to many aspects of life, such as learning a new language and acquiring new social norms to fit into new environments (Zhang & Jung, 2017)].

From the 20 texts, 12 (60%) employed Berry´s definition to define acculturative stress (e.g., a stress reaction in response to life events that are rooted in the experience of acculturation) (Berry, 2006). Five (25%) did not define acculturative stress or used a pleonasm. Three (15%) used other parameters as a definition. Stressors such as changes, depression, homesickness, loneliness, anxiety, stress, frustration, fear, and pessimism can have a direct impact on mental and physical health (Merced et al., 2022; Sandhu & Asrabadi, 1994). Additionally, people may experience difficulties due to personal and institutional discrimination, language barriers, and pressure to adopt new cultural values and behaviors while leaving family and friends behind in the country of origin (Castillo et al., 2015). It is important to emphasize that one measure used Lazarus and Folkman (1984) definition of tress: a response to a perceived imbalance between environmental demands and personal coping resources, whereby environmental demands exceeded the coping resources, leading to negative affect, although is not modified by culture.

More than half (61.79%; n = 262) of the 424 items in the measures focus on stressors. Several of them are considered, for instance: language, [e.g., “I feel difficulty communicating with local people due to the language barrier” (Bashir & Khalid, 2020, p. 9), “I often feel misunderstood or limited in daily situations because of my English skills” (Miller et al., 2011, p. 305)], cultural [e.g., “I feel uncomfortable when I am trying to adapt to a new culture and values” (J. Y. Pan et al., 2010, p. 171)], familiar [e.g., “I miss my country and my people” (Scholaske et al., 2020, p. 366)], cultural [“I feel sad when I do not see my cultural roots in this society” (Jibeen & Khalid, 2010, p. 237)]. About a third part of the items (35.61%; n = 151) are focused on appraisal: “I feel pressured when making a comparison with fellow students”; “I feel uncomfortable when I am trying to adapt to a new culture and values” (Pan, 2010, p. 171); less than 5% (2.59%; n = 11) consider coping: “Adversity provides a good learning opportunity”; “Adversity constitutes a platform for future development” (Pan, 2008, p. 483). And none consider symptoms.

Table 1.

Research about internal structure of measures of acculturative stress, number of items and their distribution according to dimensions of stress.

Table 1.

Research about internal structure of measures of acculturative stress, number of items and their distribution according to dimensions of stress.

| Research |

Items |

Stress Dimension |

| Stressors |

Appraisal |

Coping |

Symptoms |

| (A) |

12 item version riverside acculturative stress inventory a (merced et al., 2022) |

12 |

12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| (B) |

16-item acculturative stress scale (hasan, 2017) |

16 |

10 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

| (C) |

abbreviated version of the hispanic stress inventory for immigrants b (cavazos-rehg et al., 2006) |

25 |

20 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

| (D) |

acculturative hassles scale for chinese students (j. y. pan et al., 2010) |

17 |

13 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

| (E) |

acculturative stress for iranian diaspora scale (dokoushkani et al., 2019) |

27 |

24 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

| (F) |

acculturative stress inventory for children (suarez-morales et al., 2007) |

12 |

12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| (G) |

acculturative stress scale for chinese college students (bai, 2016) |

32 |

16 |

16 |

0 |

0 |

| (H) |

acculturative stress scale for international students c

[(i) sandhu e asrabadi (1994)c;

(ii) zhang e jung (2017)]. |

36 |

18 |

18 |

0 |

0 |

| 23 |

13 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

| (I) |

acculturative stress scale for pakistani muslim students (bashir & khalid, 2020) |

24 |

16 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

| (J) |

brief scale for the evaluation of acculturation stress in migrant population (urzúa et al., 2021) |

14 |

14 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| (K) |

chinese making sense of adversity scale (j. y. pan et al., 2010) |

12 |

0 |

1 |

11 |

0 |

| (L) |

coping with acculturative stress in american schools scale (castro-olivo et al., 2014) |

16 |

8 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

| (M) |

multidimensional acculturative stress inventory d

(i) jibeen e khalid (2010)

(ii) rodriguez et al. (2015)

(iii) castillo et al., (2015)

iv scholaske et al. (2020) |

24

24

25

25 |

12

14

14

14 |

12

10

11

11 |

0

0

0

0 |

0

0

0

0 |

| (N) |

multidimensional acculturative stress scale e (lapkin & fernandez, 2018) |

24 |

12 |

12 |

0 |

0 |

| (O) |

riverside acculturation stress inventory (miller et al., 2011) |

15 |

8 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

| (P) |

societal, attitudinal, familial, and environmental acculturative stress scale (suh et al., 2016) |

21 |

12 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

| |

|

(n= 424)

100% |

(n=262)

61.79% |

(n=151)

35.61% |

(n=11)

2.59% |

(n=0)

0% |

Table 2.

Acculturative stress definitions and internal structure (factors) of measures.

Table 2.

Acculturative stress definitions and internal structure (factors) of measures.

| Research |

Factors |

Acculturation definition |

Acculturative stress definition |

| (A) |

1) Work and Language Challenges; 2) Discrimination; 3) Intercultural Relations; 4) Cultural Isolation. |

“(…) learning aspects of a new culture, including learning a new language, value system, and norms” (p. 2). |

“Stressors, as well as the response to certain conditions that happen before, during, and after immigration, all cumulatively combined” (p. 2). |

| (B) |

1) discrimination; 2) threat of ethnic identity; 3) lack of opportunities for education; 4) homesickness; 5) language barrier. |

No definition |

“(…) reaction in response to life events that are rooted in the experience of acculturation or reduction in psychological health and psychological well-being of ethnic minorities that present between the process of adjustment to a recent culture” (p. 441). |

| (C) |

1) Extrafamilial Stress; 2) Intrafamilial Stress. |

No definition |

No definition |

| (D) |

1) Language deficiency; 2) academic work; 3) cultural difference; 4) social interaction |

“(…) the process of change that occurs to a person in a cross-cultural situation, both by the influence of contact with another culture and the culture of origin (p. 164)” |

“(…) a process of interaction between acculturative stressor, cognitive appraisal and coping, and adaptation outcomes.” (p. 164). |

| (E) |

1) Concern about finances and a desire to stay in any country except Iran; 2) Language difficulties; 3) Interpersonal stress; 4) Stress from new culture and desire to return to Iran; 5) Academic pressure; and 6) Stress from new rules and regulations. |

No definition |

“ (…) reaction in response to dealing with life events rooted in the experience of acculturation in a new culture (…) carries both negative (e.g., distress) and positive (e.g., eustress) connotations” (p. 67). |

| (F) |

1) perceived discrimination; 2) immigration-related experiences. |

“a group-level phenomenon, which occurs when two cultures come into continuous direct contact (p. 216)” |

“(…) originates from attempts by individuals at resolving the differences between their culture of origin and the dominant culture (…) has been shown to be related to mental health problems, such as increased depression and substance use” (p. 216). |

| (G) |

1) Language insufficiency; 2) social isolation; 3) perceived discrimination; 4) academic pressure; 5) guilt toward family. |

No definition |

“(…) a negative side effect of acculturation. It occurs when acculturation experiences cause problems for individuals and can produce a reduction of individuals’ physical, psychological, and social health” (p. 443). |

| (H) |

(I) 1) perceived discrimination; 2) homesickness; 3) perceived hate/rejection; 4) fear; 5) stress due to change/culture shock; 6) guilt. |

No definition |

No definition |

| |

(II) 1) Perceived discrimination; 2) Fearfulness; 3) Homesickness; 4) Stress due to change; 5) Guilt. |

“(…) framework which explains at an individual level how well individuals can behaviorally and psychologically adapt to the new cultural environment (p. 24). |

No definition |

| (I) |

1) academic stressors; 2) general living and finance; 3) perceived discrimination; 4) cultural and religious; 5) local & environmental; 6) language barrier. |

“(…) a dual process of psychological and cultural change at the individual or group level, which takes place as a result of direct contact with the host culture. It has been argued that the new demands of the host society may impede the social, psychological and physical aspects of an individual” (p. 2). |

“(…) unbearable events, uninviting behaviors of host nationals, and tense situations, that are confronted by international students and reduce chances of cultural adjustment” (p. 2). |

| (J) |

1) the stress derived from preparation and departure from the country of origin; 2) the stress produced by socioeconomic concerns in the host country; 3) the tensions inherent to adaption to sociocultural changes or Chilean society. |

“(…) a process resulting from contact between two or more cultural groups with impacts at a group level, producing transformations in social and institutional structures, and at the individual level, bringing behavioral changes” (p. 1). |

No definition |

| (K) |

1) Making positive sense of adversity; 2) Making negative sense of adversity. |

“(…) the process of change that occurs to a person in a cross-cultural situation, both by influence of contact with another culture and by the culture of origin (p. 480). |

No definition |

| (L) |

1) Perceived Discrimination; 2) Sense of Belonging; 3) Related Stress; 4) Familial Acculturative Gap. |

No definition |

“(…) the psychological tension that results from attempts to adapt to a new culture or society and the need to resolve linguistic, social, and behavioral differences or conflicts that arise between one’s native and host culture” (p. 4). |

| (M) |

(I) 1) Discrimination and rejection; 2) differences with the out-group (native Spaniards); 3) citizenship problems and legality; 4) problems concerning social relationships with other immigrants; 5) nostalgia and longing; and 6) family break-up |

No definition |

“(…) the stress response to challenges in negotiating and adjusting to perceived cultural incompatibilities and cultural self-consciousness because of differences in language, practices, and values between and within the host and heritage cultures” (p. 1439). |

| |

(II) 1) Turkish Competency Pressures; 2) English Competency Pressures; 3) Pressure to Acculturate; 4) Pressure Against Acculturation. |

“(…) the process of adapting to the culture of the host country after migration that involves negotiating differing aspects of the heritage and host culture, and this affects immigrants (i.e., people who live in another country than where they were born) as well as their descendants who were born in the host country” (p. 2). |

(…) a reduction in mental health – such as consequent anxiety, depression, feelings of marginality, and identity confusion” (p. 2). |

| |

(III) 1) Heritage Language Competence Pressure; 2) English Competence Pressure; 3) Pressure to Acculturate; 4) Pressure Against Acculturation. |

“(…) process of cultural change that occurs when two cultural groups come into contact, has become an important area of study” (p. 916). |

“(…) difficulties due to (a) personal and institutional discrimination, (b) learning and becoming competent in a new language, (c) leaving family and friends behind in the country of origin, (d) pressure to adopt new cultural values and behaviors, and (e) pressure from heritage culture members to not become Americanized” (p. 916) |

| |

(IV) 1) Discrimination; 2) Threat; 3) Lack of opportunities; 4) Homesickness; 5) Language-barrier |

No definition |

“(…) a stress reaction in response to life events that are rooted in the experiences of acculturation” (p. 234) |

| (N) |

1) Discrimination; 2) Threat to ethnic identity; 3) Lack of opportunities for occupational and financial mobility; 4) Homesickness; 5) Language barrier. |

“The multidimensional process of cultural and psychological changes that occur as a result of contact between two or more cultural groups” (p. 2). |

“(…) stress related to the feelings of isolation and insecurity in a foreign country that immigrants experience has been associated with the increased risk of chronic health conditions and poor mental health outcomes” (p. 2). |

| (O) |

1) Language skills; 2) Work challenges; 3) Intercultural relations; 4) Discrimination; 5) Cultural/ethnic makeup of the community. |

“(…) process by which an individual undergoes cultural change across a number of life domains such as language, ethnic identification, cognition, affective expression, and affiliation preferences as a result of continuous exposure to a second culture (p. 1). |

“(…)a physiological and psychological state brought about by culture-specific stressors rooted in the process of acculturation” (p. 1). |

| (P) |

1) General stress; 2) family stress. |

“(…) a unique dual adjustment process that brings cultural and psychological change when two or more cultures and their individual members are in contact” (p. 217). |

“(…) stress reaction in response to life events that are rooted in the experience of acculturation” (p. 217) |

Discussion

The results indicate that the two-dimensional understanding of acculturation is prevalent in the studied corpus. Theories of acculturation have progressed from single-dimensional to two-dimensional conceptualizations of the acculturation process. (Suarez-Morales et al., 2007). In the unidimensional conceptualization, acculturation has been viewed as a process in which there is an inverse linear relationship between an individual’s involvement with her original and host cultures, a zero-sum process, that is, individuals adopting host-culture attributes (e.g., behaviors and values) simultaneously discard these same attributes that correspond to their culture of origin (Gim Chung et al., 2004). For Rhee (2019), this model of acculturation places migrants’ ethnic culture and host culture at the opposite end of a linear continuum (migrants are expected to renounce their ethnic culture and get assimilated into the host culture).

Unlike the unidimensional model, a popular bi-dimensional approach is the Fourfold Theory (Rudmin, 2003). It assumes that a person can appreciate, practice, or identify with two different cultures. Each one can present positive or negative valence, representing a person’s positive and negative psychological states (e.g., attitudes, preferences, attachment) or representing the presence or absence of cultural issues (e.g., behaviors, language use, food), and other observable manifestations of culture (Rudmin, 2003). According to Rudmin, this approach developed at least seven versions of acculturation typologies before, and independently of Berry’s version [e.g., mimicry, rejected, pseudo, denial (Ichheiser, 1949), monism, pluralism, interactionism]. Nevertheless, Berry’s (2006) Bi-dimensional Model of Acculturation (BMA) is one of the most productive acculturation frameworks. It considers the intersection of two attitudinal dimensions: adhering to ethnic identity and characteristics on a horizontal continuum and maintaining contacts and relationships with the host society on a vertical continuum (Rhee, 2019). Each one represents a level of adherence to one specific culture. Lefringhausen and Marshall (2016) define it as the degree to which one wishes to maintain its culture and the level to which one wishes to participate and have contact with different cultural groups. BMA also discusses the experience of locals and theoretically linked concepts (i.e., etnorelativism and ethnocentrism) (Lefringhausen & Marshall, 2016). Finally, this model generates four possible acculturation strategies: Separation, integration, assimilation, and marginalization (Rhee, 2019), following the Fourfold Theory.

As reported by Lefringhausen and Marshall (2016), in a bi-dimensional model, the two factors may vary independently from each other (i.e., orthogonal), or they may be positively correlated (i.e., oblique), allowing for integration – the simultaneous endorsement of one’s heritage and mainstream culture. Gim Chung et al. (2004) extend the orthogonal conception of acculturation to a third dimension: a pan-ethnic culture. In this view, Espiritu (1993) considers that pan-ethnicity may be appropriated as a political resource and as a basis for mobilization and collective empowerment. Within this context that the internal forces also take shape in the form of a new, emergent culture (Espiritu, 1993). As claimed by Huynh et al. (2018), bi-cultural individuals face the challenge of negotiating between multiple, and even conflicting, cultural identities and value systems in their everyday lives.

We can identify three approaches to conceptualize acculturative stress (J. Y. Pan et al., 2010): Stimulus-Based Approach, where conflicts, difficulties, or stressors arise from the cross-cultural adaptation (Joiner & Walker, 2002); Response-Based Approach, in which acculturative stress means an individual’s health-status reduction when confronting cultural-change problems (Berry, 2006); and Process-Oriented Approach, that defines acculturative stress as an interactive process between the new environment of the host society and acculturating individuals. It considers personal appraisal and coping (Berry, 2006). In this systematic review, we noted that the Stimulus-Based Approach was emphasized, as most of the items and their distribution, according to the dimensions of stress, pertained to stressors that arose from the cross-cultural adaptation process.

Most of the articles utilized both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis to assess the internal structure of the data and gain insights into the validity of the results. Exploratory factor analysis was used to identify the underlying latent constructs in the data, while confirmatory factor analysis was used to establish the degree to which the proposed measurement model conforms to observed data. Furthermore, this process allowed for further examination of the relationships between the different variables and their connections to the overall model. This enabled researchers to gain a better understanding of the structure of the data and the conclusions that could be drawn from it.

The demands on the cross-cultural mobility adaptation process – acculturation (Berry, 2006) – may become stressors, conflicts, and difficulties (Joiner & Walker, 2002), stress sources (Basáñez et al., 2014), or challenges (Bashir & Khalid, 2020). An inability to deal with such challenges may give rise to Acculturative stress, which can vary depending on the differences between cultures (Lueck & Wilson, 2010). It occurs when these experiences cause problems for individuals and can produce a reduction in health status, including psychological, somatic, and social aspects (Berry, 2006), and a decrease in psychological well-being (Lueck & Wilson, 2010). It is a reaction in response to life events that are rooted in the experience of acculturation (Berry, 2006). Acculturative stress is inherent to the adaptation process to a new culture and challenges in negotiating and adjusting to perceived cultural incompatibilities and cultural self-consciousness (e.g., differences in language, practices, and values) (Gil et al., 1994; Rodriguez et al., 2015). Psychological tension results from attempts to adapt to a new culture or society and the need to resolve linguistic, social, and behavioral differences or conflicts that arise between one’s native and host culture (Castro-Olivo et al., 2014; Dokoushkani et al., 2019). Acculturative Stress symptoms and variables include social customs, language preference, age at the time of migration, years of residence in the host culture, income levels, ethnic networks, family extendedness, and perceptions of prejudice (Lueck & Wilson, 2010).

Considering the acculturation and acculturative stress definitions used in the articles analyzed in this systematic literature review, we define CCMS as a type of stress that can be positive (eustress) or negative (distress) and refers to the ability to deal with events (e.g., challenges, difficulties, conflicts, demands) or stressors before, during, and after the cross-cultural mobility adaptation process. It is a transactional process, a relationship between the person and the environment appraised as personally significant (e.g., a change in health status, well-being). Requires constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and internal demands appraised as taxing or exceeding the individual's resources (coping) and varies depending on the differences between cultures. CCMS includes physiological (e.g., palpitations, sweating, dry mouth) and psychological (e.g., anxiety, dysthymia, excitement) responses to internal or external stressors or stress sources.

Upon further examination of the studies conducted, it is apparent that researchers have not paid adequate attention to the four components of CCMS (stressors, appraisal, coping and symptoms). In fact, most studies focus largely on stressors and partially on cognitive appraisal, while neglecting the other components. This lack of attention presents a great challenge when attempting to measure CCMS. Any scale, questionnaire, and inventory should consider stressors, appraisal, coping and symptomatology; however, most of them simply address part of the phenomena, with some concentrating on the stressors and others on the coping strategies. There are very few scales that take into account physiological (e.g., sweating, palpitations) and psychological (e.g., anxiety, excitement) responses to internal or external stressors, or consider the positive aspects of such responses (e.g., excitement, success stories). Consequently, we think that most efforts to measure acculturative stress fail to reach their intended goals.

Most scales, questionnaires, and inventories use Berry’s Bi-dimensional Acculturation Model (Berry, 2006) as a base theory. Nevertheless, while Berry's model has evolved through time, the measures still lack to consider the CCMS as entire phenomena. That said, measures could benefit from new developments such as Kim’s Integrative Communication Theory of Cross-Cultural Adaptation (Kim, 2017) and Lazarus and Folkman´s Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (TMSC).

As expected, all measures identified in this systematic review are Likert scales. Despite some problems and controversies, like the mid-point biases and the number of items necessary (Tanujaya et al., 2022), this form of measurement has a notable role in contemporary psychology because it is one of the best methods in psychological research (Jebb et al., 2021).

Likert scales are a widely-used tool for measuring attitudes, however, there are some drawbacks to their usage that should be taken into consideration. The size of the measure items pool and the factor organization can have a significant impact on the accuracy and reliability of the results, as a greater number of response possibilities may require more mental effort from the respondent, thus reducing the quality of the responses (Tanujaya et al., 2022). In this research, 68.75% of the scales used were 5-point Likert scales, which is the most commonly used format. Additionally, the answers may be affected by the respondents' individual interpretation of the items, particularly in cross-cultural research, resulting in unreliable outcomes. Moreover, Likert scales may not provide a comprehensive measure of attitudes and opinions (Tanujaya et al., 2022). They may not capture the nuances and complexity of an individual's thoughts or attitudes, nor can they accurately measure how strongly an individual feels about a particular topic.

Therefore, when constructing an acculturative stress measure, incorporating a mix of scales can help to increase the validity of the results. Using a combination of Likert scales and open-ended questions allows for a more thorough assessment of the respondents' attitudes and opinions. The open-ended questions permit more detailed responses that can capture the full range of their feelings. Additionally, using both types of questions can diminish the influence of individual prejudices and lower the chance of erroneous results. Mixed scales can also be employed to measure more intricate topics and to assess the nuances of opinions and attitudes more accurately and validly than a single type of scale. Therefore, researchers should take into consideration using both Likert scales and open-ended questions when performing research that necessitates a comprehensive measure of attitudes and opinions. This can aid in ensuring more precise and dependable results and to provide a more comprehensive comprehension of the respondents' attitudes and opinions.

The previous recommendations should be considered with attention, as the measures analyzed have been applied to a wide array of target audiences (e.g., Latinx immigrants in the USA and Pakistani Muslim students). It is essential to broaden the scope of research about CCMS, including the development of measures with validity evidence and indicators of reliability for assessing the impact of mobility on diverse populations in a robust way, giving insights into how cross-cultural contact affects people from different cultures and how they can manage it.

Research Limitations

This systematic review has some limitations. The possibility of false negatives due to the terminology adopted (e.g., not using the expression "stress from acculturation") and to the fact that we restricted the search to specific parts of the text (abstract, keywords, and title) is the most prominent. These procedures may have generated bias in the number of records retrieved from the databases.

Regardless of the limitations, the results of this systematic review denote the necessity to develop a measure to examine CCMS as an entire phenomenon and not part of it. Without instruments like these, the effort to research and provide health services to people in mobility is hindered.

Author Contributions

Alberto Abad: Conceived and designed the analysis; Collected the data; Contributed data and analysis tools; Performed the analysis; Wrote the paper. Altemir José Gonçalves Barbosa: Conceived and designed the analysis; Contributed data and analysis tools; Wrote the paper.

Funding

Minas Gerais State Agency for Research and Development – FAPEMIG.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This investigation was approved by a Human Research Ethics Committee (CAAE) Number: 20092919.9.0000.5147 Resolution Number: 3775213.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (Org.). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed). American Psychiatric Association.

- Basáñez, T., Dennis, J. M., Crano, W. D., Stacy, A. W., & Unger, J. B. (2014b). Measuring Acculturation Gap Conflicts Among Hispanics: Implications for Psychosocial and Academic Adjustment. Journal of Family Issues, 35(13), 1727–1753. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Bashir, A., & Khalid, R. (2020). Development and Validation of the Acculturative Stress Scale for Pakistani Muslim Students. Cogent Psychology, 7(1), 1714101. [CrossRef]

- 30, 69–85. [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. W. (2006). Contexts of acculturation. Em D. L. Sam & J. W. Berry (Orgs.), The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology (p. 27–42). Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, L. G., Cano, M. A., Yoon, M., Jung, E., Brown, E. J., Zamboanga, B. L., Kim, S. Y., Schwartz, S. J., Huynh, Q. L., Weisskirch, R. S., & Whitbourne, S. K. (2015). Factor structure and factorial invariance of the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 27(3), 915–924. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Castro-Olivo, S. M., Palardy, G. J., Albeg, L., & Williamson, A. A. (2014). Development and validation of the Coping with Acculturative Stress in American Schools (CASAS-A) scale on a latino adolescent sample. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 40(1), 3–15. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, T. (2006). On the move: Mobility in the modern Western world. Routledge.

- Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of personality assessment 49((1)), 71–75.

- Dokoushkani, F., Juhari, R., Abdollahi, A., Motevaliyan, S. M., Villanueva, R. A., & Chen, Z. J. (2019). Development and validation of the acculturative stress among iranian diaspora scale. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 13(1), 65–79. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Dorsinfang-Smets, A. (1961). R. Bastide. Problèmes de l’entrecroisement des civilisations et de leurs oeuvres (II, pp. 315-330). Revue de l’Institut de sociologie 1–2, 398–401.

- Espiritu, Y. (1993). Asian American Panethnicity: Bridging Institutions and Identities. http://www.vlebooks.com/vleweb/product/openreader?id=none&isbn=9781439905562.

- Gil, A. G., Vega, W. A., & Dimas, J. M. (1994). Acculturative stress and personal adjustment among hispanic adolescent boys. Journal of Community Psychology, 22(1), 43–54. [CrossRef]

- Gim Chung, R. H., Kim, B. S. K., & Abreu, J. M. (2004). Asian American Multidimensional Acculturation Scale: Development, Factor Analysis, Reliability, and Validity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 10(1), 66–80. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, B. (2017). Development and validation of 16-item acculturative stress scale for within country migrated students. Indian Journal of Health & Wellbeing 8((6)).

- Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., & Mosher, S. W. (1992). The Perceived Stress Scale: Factor structure and relation to depression symptoms in a psychiatric sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 14(3), 247–257. [CrossRef]

- Huynh, Q. L., Benet-Martínez, V., & Nguyen, A. M. D. (2018). Measuring variations in bicultural identity across U.S. ethnic and generational groups: Development and validation of the Bicultural Identity Integration Scale-Version 2 (BIIS-2). Psychological Assessment, 30(12), 1581–1596. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Ichheiser, G. (1949). Misunderstandings in human relations: A study in false social perception. American Journal of Sociology 55, 70.

- International Organization for Migration. (2022). WORLD MIGRATION REPORT 2022.

- Jibeen, T., & Khalid, R. (2010). Development and Preliminary Validation of Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Scale for Pakistani Immigrants in Toronto, Canada. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34(3), 233–243. [CrossRef]

- Joiner, T. E., & Walker, R. L. (2002). Construct validity of a measure of acculturative stress in African Americans. Psychological Assessment, 14(4), 462–466. [CrossRef]

- Kefayati, E. (2016). The Relationship between Acculturative Stress, Perceived Social Support, and Perceived Discrimination in International Students. Eastern Mediterranean University EMU.

- Keles, S., Friborg, O., Idsøe, T., Sirin, S., & Oppedal, B. (2018). Resilience and acculturation among unaccompanied refugee minors. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 42(1), 52–63. [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, N. G., & Carr, K. (2020). Exploring the factor structure and psychometric properties of an acculturation and resilience scale with culturally and linguistically diverse adolescents. Australian Psychologist, 55(1), 26–37. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Y. (2017). Integrative Communication Theory of Cross-Cultural Adaptation. The International encyclopedia of Intercultural communication 1–13.

- Kuo, C.-H. B. (2001). Correlates of coping of three Chinese adolescent cohorts in Toronto, Canada: Acculturation and acculturative stress. The University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- Lapkin, S., & Fernandez, R. (2018). Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Psychometric Properties of the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Scale. Australian Psychologist, 53(4), 339–344. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

- Lefringhausen, K., & Marshall, T. C. (2016). Locals’ Bidimensional Acculturation Model: Validation and Associations with Psychological and Sociocultural Adjustment Outcomes. Cross-Cultural Research, 50(4), 356–392. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Lueck, K., & Wilson, M. (2010). Acculturative stress in Asian immigrants: The impact of social and linguistic factors. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34(1), 47–57. [CrossRef]

- Merced, K., Ohayagha, C., Grover, R., Garcia-Rodriguez, I., Moreno, O., & Perrin, P. B. (2022). Spanish Translation and Psychometric Validation of a Measure of Acculturative Stress among Latinx Immigrants in the USA. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5). Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Miller, M. J., Kim, J., & Benet-Martínez, V. (2011). Validating the Riverside Acculturation Stress Inventory with Asian Americans. Psychological Assessment, 23(2), 300–310. [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, n71. [CrossRef]

- Pan, J. Y., Yue, X., & Chan, C. L. W. (2010). Development and validation of the acculturative hassles scale for chinese students (AHSCS): An example of mainland chinese university students in Hong Kong. Psychologia, 53(3), 163–178. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Redfield, R., Linton, R., & Herskovits, M. J. (1936). Memorandum for the study of acculturation. American anthropologist 38((1)), 149–152.

- Rhee, S. L. (2019). Korean immigrant older adults residing in non-Korean ethnic enclaves: Acculturation strategies and psychosocial adaptation. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 29(7), 861–873. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, N., Flores, T., Flores, R. T., Myers, H. F., & Vriesema, C. C. (2015). Validation of the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory on adolescents of Mexican origin. Psychological assessment, 27(4), 1438–1451. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Rudmin, F. W. (2003). Critical History of the Acculturation Psychology of Assimilation, Separation, Integration, and Marginalization. Review of General Psychology, 7(1), 3–37. [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, D. S., & Asrabadi, B. R. (1994). Development of an Acculturative Stress Scale for International Students: Preliminary Findings. Psychological Reports, 75(1), 435–448. [CrossRef]

- Scholaske, L., Rodriguez, N., Sari, N. E., Spallek, J., Ziegler, M., & Entringer, S. (2020). The German Version of the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory (MASI) for Turkish-Origin Immigrants: Measurement Invariance of Filter Questions and Validation. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 36(5), 889–900. [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Morales, L., Dillon, F. R., & Szapocznik, J. (2007). Validation of the Acculturative Stress Inventory for Children. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13(3), 216–224. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- VandenBos, G. R. (Org.). (2015). APA dictionary of psychology (2nd ed.). American Psychological Association. [CrossRef]

- Vitaliano, P. P., Russo, J., Weber, L., & Celum, C. (1993). The Dimensions of Stress Scale: Psychometric Properties1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23(22), 1847–1878. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., & Jung, E. (2017). Multi-Dimensionality of Acculturative Stress among Chinese International Students: What Lies behind Their Struggles? 7((1)), 23–43.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).