1. Introduction

Liquid Biopsy and Early Stage Lung Cancer

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common form of lung cancer, accounting for approximately 85% of all cases[

1,

2,

3,

4]. EGFR mutations are found in approximately 10-15% of NSCLC cases[

4,

5] in the United States and is more commonly found in patients who have never smoked or have a history of light smoking. Traditional methods for detecting EGFR mutations in NSCLC include tissue biopsy, which involves the collection of tissue samples through invasive procedures such as bronchoscopy or surgery.

Computed tomography (CT) and liquid biopsy are both valuable tools in lung cancer early screening and long-term monitoring[

6,

7]. CT scans are commonly used to screen for lung cancer in high-risk individuals, such as smokers, and can detect early-stage tumors that may not be visible on a chest X-ray. However, the inconvenience of radiation exposure and the false positive rate limits CT mainly for screening, not for accurate diagnostics in lung cancer. On the other hand, liquid biopsy is a minimally invasive method for detecting genetic mutations and other biomarkers associated with lung cancer, such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)[

8,

9], circulating tumor cells (CTCs)[

10], and protein markers[

11]. Liquid biopsy can provide information about tumor heterogeneity and evolution, which can be particularly useful in monitoring disease progression and treatment response over time. In early stage lung cancer, liquid biopsy has become an increasingly important method for detecting specific mutations in tumor DNA, such as the EGFR mutation. Liquid biopsy also has advantages in detecting mutations that may not be present in the primary tumor or metastases, as well as the ability to monitor changes in mutation status over time.

Ultra-Short Circulating Tumor DNA in Lung Cancer

Ultra-short circulating tumor DNA (usctDNA) is a subtype of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) that is characterized by very short fragment lengths, typically less than 100 base pairs in length[

12,

13,

14,

15]. UsctDNA is thought to be primarily derived from apoptotic and necrotic cancer cells that have undergone further fragmentation. These small DNA fragments are then released into the bloodstream. UsctDNA has been detected in the bloodstream and other body fluids of patients with various types of cancer, including lung cancer.[

14] UsctDNA has several potential advantages over longer ctDNA fragments, including increased stability and resistance to nuclease degradation [

14].

Recent studies have shown that ultrashort-single-stranded cfDNA (uscfDNA) and usctDNA

may have potential clinical utility in the diagnosis and monitoring of lung cancer[

14,

15]. In addition, biomarker discovery based on uscfDNA with mutation are also important and promising. Many of the biomarker discovery methods used for ctDNA analysis are based on fragmented ctDNA, and there may be a loss or deviation of certain biomarkers when analyzing very short fragments of ctDNA, such as uscfDNA. Developing a biomarker panel specifically for usctDNA could be an important area of research. By focusing on biomarkers that are more readily detectable in usctDNA, researchers may be able to improve the sensitivity and specificity of ctDNA-based diagnostic and prognostic assays for lung cancer.

However, the analysis of usctDNA in lung cancer can be challenging. One of the main challenges in detecting usctDNA is the limitation imposed by the small fragment size of the DNA. The size of usctDNA fragments are typically less than 100 base pairs in length, which makes them difficult to detect using traditional sequencing methods. Detection of mononucleosomal ctDNA routinely involves PCR amplification to locate the rare mutant copies amongst wild-type noise. For PCR-based detection, however, it is difficult to design primers that will reliably amplify the target sequence. This can result in poor sensitivity and specificity and can make it challenging to distinguish between usctDNA and non-tumor DNA fragments that may be present in the sample. Some technologies have been developed by adding adapters to the ends of the fragments, which can increase their length and make them easier to detect using standard sequencing methods, called as adapter ligation-based amplification (ALA)[

16]. However, ALA has the potential for adapter bias, in which some fragments may be preferentially amplified over others, which if applied to usctDNA, could lead to a skewed representation in the sample.

Multiplexing Point-of-Care Device for Lung Cancer Monitor

Point-of-care devices (POC) are medical devices that perform diagnostic tests at close proximity to the patient, with results available quickly and easily[

17,

18]. In the case of NSCLC and EGFR mutation monitoring, POC devices are particularly useful for the following reasons. Firstly, in early-stage NSCLC, it can be challenging to obtain enough tissue samples for accurate EGFR mutation analysis. Liquid biopsy-based POC devices can provide an alternative solution by detecting ctDNA in the patient's blood, allowing for more reliable and timely detection of EGFR mutations[

19]. Secondly, patients with NSCLC receiving targeted therapy, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), require regular monitoring to evaluate treatment efficacy and detect resistance mutations. POC devices that can detect EGFR mutations in blood samples can provide real-time monitoring of the patient's treatment response and help guide treatment decisions, including the selection of alternative therapies in case of TKI resistance[

20]. In summary, POC devices offer faster turnaround time, reduced cost, and ease of use, which makes them a more practical and convenient option for monitoring EGFR mutations in NSCLC patients.

Historically, liquid biopsy platforms were designed for a limited panel of targets. For example for NSCLC, EGFR L858R point mutation at exon21 and deletions within exon19 were priotized for their involvement in treatment selection[

21]. Recently, further research showed the importance of simultaneous biomarker detection since lung cancer is a complex disease with multiple genetic mutations and alterations that can influence treatment outcomes[

22,

23]. During early-stage screening for indeterminate pulmonary nodules (IPNs), the tumor burden is typically low, therefore detecting of single cancer-specific biomarkers in blood or other body fluids is challenging and always results in low sensitivity and specificity. Therefore, using a panel of biomarkers that reflect a lung cancer, in combination with imaging techniques, such as low-dose computed tomography (LDCT), may improve early detection rates, and reduce the number of false-positive results. This theoretical panel of biomarkers that includes multiple genetic mutations and protein markers may provide a comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment planning. In addition, in patients undergoing targeted therapy, such as TKI treatment, monitoring a panel of biomarkers that includes genetic mutations associated with TKI resistance, such as T790M[

24], C797S[

25] in EGFR, MET amplification[

26], and HER2 amplification[

27], can provide a more comprehensive approach to monitoring treatment response and detecting the emergence of resistance.

2. Results

2.1. m-eLB Sensor for Multiple EGFR Mutations

The EFIRM sensor were first precoated with single EGFR probe and assayed for multiple targets. Three EGFR probes included L858R, Ex19del and T790M were electrochemically polymerized onto the sensor by single droplet of coating buffer. Then each sensor chip was assayed for the three EGFR mutation targets at 100 pM, as well as a blank control (hybridization buffer only). The location of the 3 targets and blank is at the four quadrants of the 96-array by drop 4 different droplets of target onto the surface as illustrated in

Figure 1A. Each droplet is around 100 μL. Individual readings of each electrode are shown in

Figure 1B and the averaged data for each target shown in

Figure 1C. For each EGFR mutation probe, the sensor only shows positive signal to its correspondant target, while negative signal for other EGFR targets including blank. The signal to noise ratio (SNR) of L858R probe is 18.0 for Ex19del, 35.7 for T790M and 17.8 for blank. The SNR of Ex19del probe is 17.0 for L858R, 9.1 for T790M and 8.3 for blank. The SNR of T790M probe is 11.6 for L858R, 46.1 for Ex19del and 20.9 for blank. The total reaction time is around 45 minutes. Signal difference is observed within each quadrant, possibly due to the different distribution of target in the droplet on the surface.

2.2. Multiplexing DNA Measurement for three EGFR Mutation in Single Droplet

For single droplet based multiplexing assay, the context of use is for each individual clinical sample, multiple biomarkers need to be assay simultaneously in one reaction well. Therefore, multiple probes for biomarker panel needs to be pre-immobilized onto the sensor at pre-designated location for the same droplet of sample. Since the EFIRM probe immobilization is a rapid aqueous based electrochemical polymerization for only 8 seconds, therefore, a microprinting platform is combined with the EFIRM platform to do a rapid in situ fabrication and measurement. The total time for printing 3 EGFR probes and blank control is within 5 minutes followed by the 8 seconds polymerization (

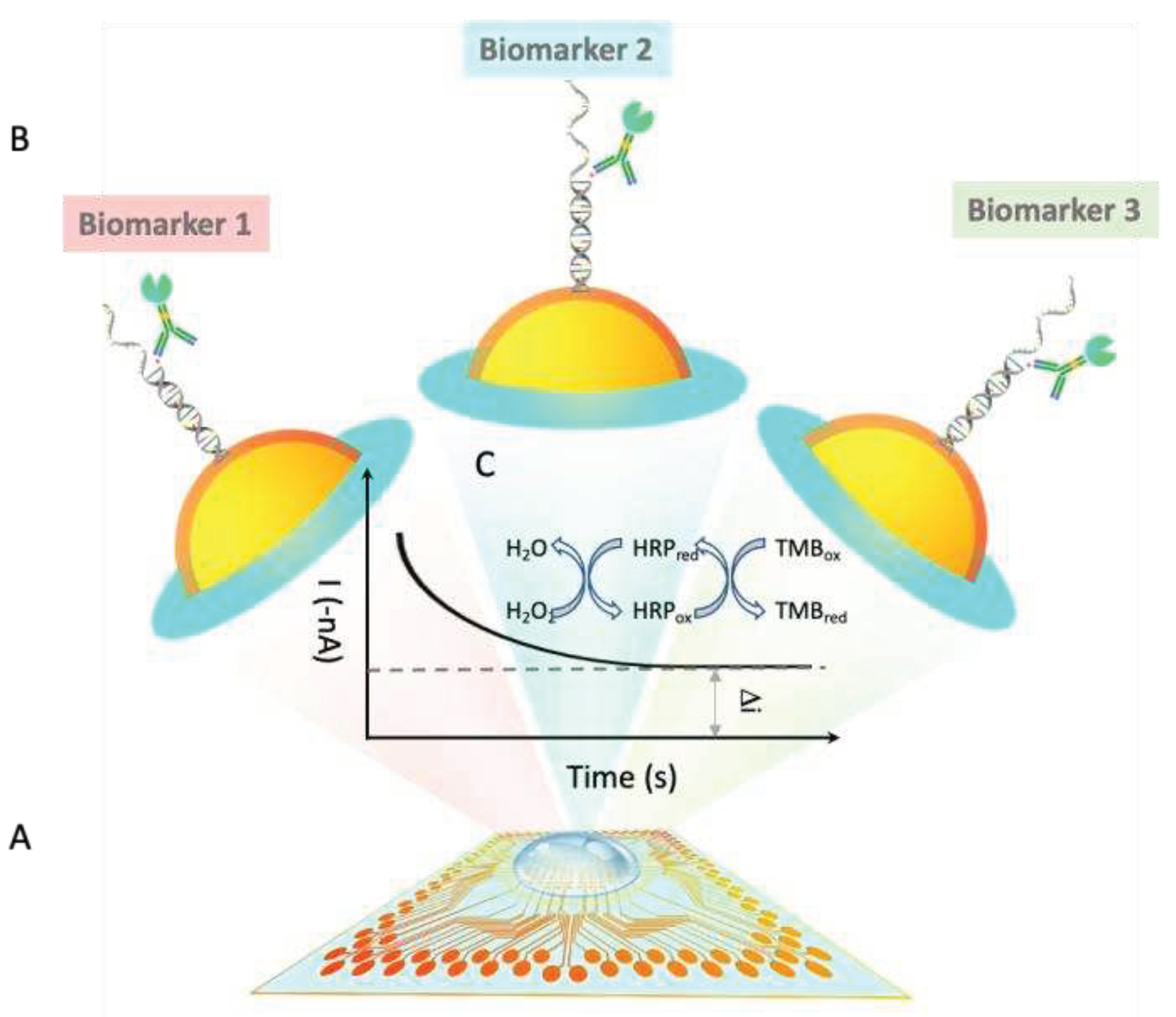

Figure 2A). Then followed by the EFIRM sample measurement with our homemade connector to multichannel potentiostat. Amperometric current for all 96 channels were readout simultaneously.

Since the amperometric reading is based on TMB substrate with couple redox procedure between HRP, hydrogen peroxide and TMB mediator, the TMB will turn to blue for positive reading (

Figure 2B). However, the colorimetric reaction is not localized, it is not accurate to measure the color, especially for high throughput microarray. In addition, colormetric measurement needs additional optical instrumentation, including light source, optical pathway alignment and optical grating to measure specific wavelength to avoid non-specific signal. Here EFIRM directly measure the redox current utilizing the same instrumentation for polymerization and hybridization. The 2-D mapping of the current in -nA are shown in

Figure 2C-E after background subtraction. High reading in the negative current indicates positive signal. Low current suggests negative signal.

2.3. Acurracy of m-eLB Platform for usctDNA

The accuracy of the EFIRM microsensor have been illustrated in

Figure 3A-D. The accumulated EFIRM results from 3 EGFR sequence is overlayed with the original design of the microprinted pattern. It shows all the EGFR positive probe detected positive EFIRM signal, all the negative electrodes only have low EFIRM reading. For quantitative analysis, receiver operator characteristics (ROC) has been conducted. For each EGFR mutation probe, the individual ROC curves were shown in

Figure 3E-G, with area under curve (AUC) of L858R as 0.98, Ex19del as 0.94, T790M as 0.93. The combinational ROC for 3 markers is also provided (

Figure 3H) with AUC of 0.97. Those results suggest the high sensitivity and specificity of the EFIRM microsensor for EGFR mutation.

The results demonstrate the m-eLB platform is capable to perform multiplexing biomarker detection from a single sample droplet. Although this is a proof-of-concept prototype with oligonucleotides in model system, it shows the novelty in single-droplet liquid biopsy assay in one reaction for detection of multiple lung cancer markers. With limited sample volume (~400 µL) and miniaturized size of sensor (total area around 1 cm

2), challenges for both sensitivity and specificity (including cross-reaction between different sensors in the simultaneous assay) have been greatly provided. The total reaction time is within 1 hour. eLB already shows multiplexibility for multiple types of targets in previous study, including measure protein, DNA, RNA simultaneously on the same sensor chip[

34,

35]. According to the COSMIC database, a biomarker panel with 14-plex-circulating lung tumor ctDNA and 6-plex miRNA biomarker panel can provide 85% coverage for early-stage lung cancer assessment. Our further work will develop the m-eLB into a 14-plex ctDNA and 6-plex miRNA LCBP, truly multiplexing.

The results indicate there is potential for direct measurement of ultra-short oligo nucleotide. Previous literature suggests that ultra-short ctDNA (~40bp) (usctDNA) is present in plasma and saliva of NSCLC patients [

14,

15,

33]. In limited samples, usctDNA were detected by targeted sequencing. Those reports indicate that usctDNA is a novel type of candidate for liquid biopsy. EFIRM is very efficient in its ability to directly detect usctDNA and mncfDNA, while PCR-based technologies cannot. The theoretical dynamic range of EFIRM for usctDNA is from 40 bp to 160 bp [

15].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. m-eLB Sensor Fabrication

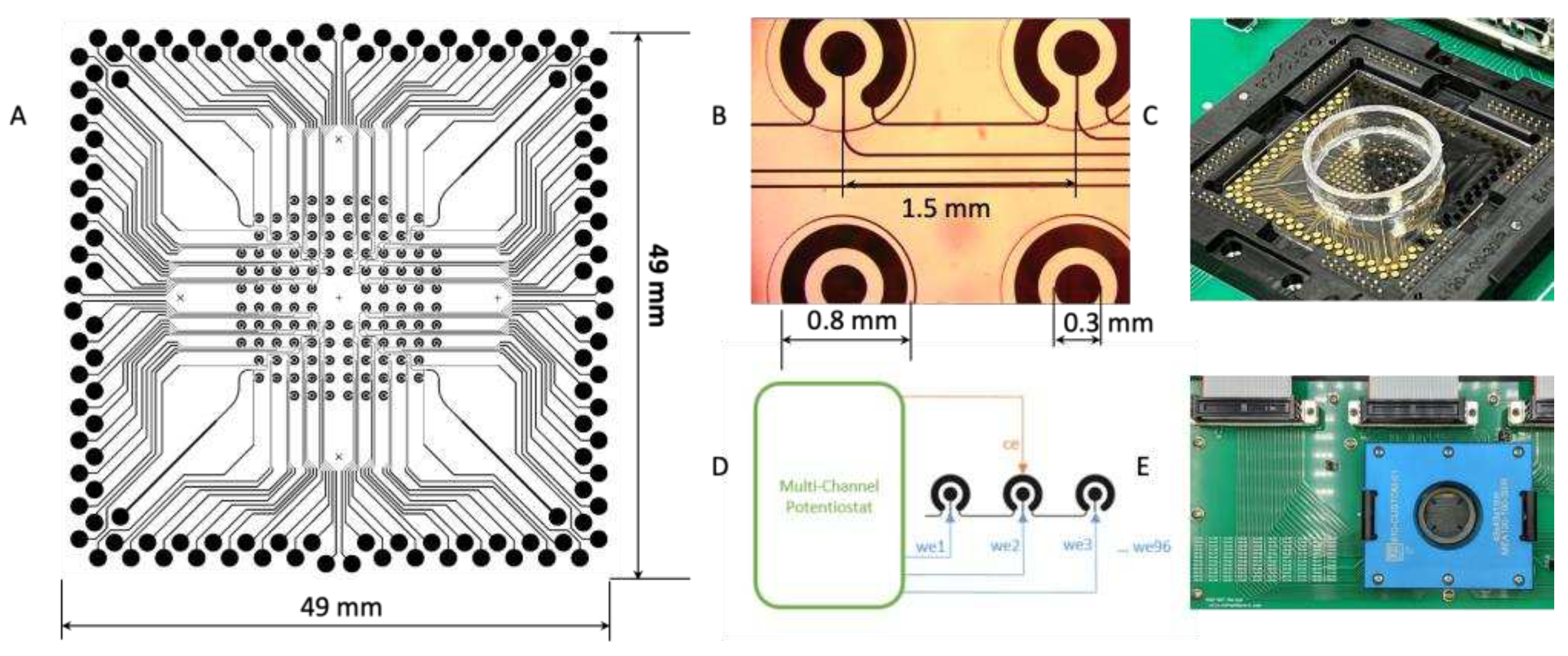

The microchip is fabricated with 100 nm gold film deposited on a glass substrate using E-beam evaporation for a smooth surface (Platypus Technologies, Madison, WI). The microchip consists of 96 individual electrochemical cells, and the cells are isolated with an epoxy-based negative photoresist SU-8 layer on top of the final chip (Figure4 A&B). The microchip uses a two electrodes system (working/counter) with counter electrode (CE) shared on the potentiostat for multiplexing. Each cell has a diameter of 2 mm and are 1.5 mm apart (

Figure 4B). With a BioDOT multichannel microprinter (Biodot OmniaTM, Irvine, CA), around 50 pL of reaction probe were precisely printed onto each electrode with designed location (

Figure 4C). For multiplexing assay, multiple probes were printed onto difference location, together with negative controls. To avoid evaporation during the printing, humidity is strictly controlled.

A custom adapter was designed to interface the microchip with a multichannel potentiostat (Figure D&E) (IVIUM CompactStat.h with 3 multiWE32, Eindhoven, Netherlands). The potentiostat could control and measure the 96 electrodes simultaneously.

3.2. m-eLB Platform with Multi-Channel Potentiostat

The basic EFIRM assay has been previously describe in detail[

19,

34,

36]. The single droplet EFIRM multiplexing assay utilize 150 μL clinical sample without any pretreatment. Paired probes (capture and detector; Integrated DNA Technologies, San Diego, CA) specific for the three TKIs EGFR mutations were designed for EFIRM as shown in

Table 1. The targeted sequences for all three are around 50 bp length.

The whole procedure is illustrated in

Figure 5. All the capture probes were non-labeled. All the detector probes were biotinylated on the 3’ end. The capture probes (100 nmol/L) were first co-polymerized with pyrrole onto the bare gold electrodes by applying a cyclic square wave electric field at 300 mV for 1 second and 1100 mV for 1 second for four cycles. The sensor is then washed with 1×PBST buffer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). Hybridization was performed in 300 μL of ultra-sensitive hybridization buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with single or mixture of oligonucleotide spiked in. The EFIRM condition is 300 mV for 1 second and 500 mV for 1 second for a total of 150 cycles of 2 seconds each followed by a 15-minute incubation at room temperature. After washing, detector probes were mixed with casein-phosphate buffered saline (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at a 1:100 dilution and transferred onto the electrodes. Subsequently, streptavidin poly-HRP80 conjugate (Fitzgerald Industries, Acton, MA) was mixed with casein- phosphate buffered saline (Invitrogen) at a 1:3 ratio and incubated for 15 minutes. Amperometric current was finally measured in TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine) at -200 mV for 1 minute.

4. Conclusions

The m-eLB enables simultaneous detection of multiple mutations in a single droplet of sample, making it a comprehensive and efficient diagnostic tool for lung cancer monitoring. The eventual direct measurement of multiple usctDNA in a clinical sample is not only critical for ctDNA diagnosis, but also for new biomarker discovery for other usctDNA correlated to diease conditions. Therefore, in the future the EFIRM platform's electrochemical detection method combined with microarray technology can offer significant benefits for EGFR mutation monitoring in lung cancer patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.W., P.Y., J.C., F.L., C.D. and D.W.; methodology, F.W. and P.Y.; validation, F.W. and P.Y.; formal analysis, F.W.; resources, D.W.; data curation, F.W.; writing—original draft preparation, F.W. and P.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.C., F.L., C.D. and D.W.; visualization, F.W. and P.Y.; supervision, C.D. and D. W.; funding acquisition, F.W. and D.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NIH grants UH2/UH3 CA206126, R01HD100015, U01 CA233370.

Data Availability Statement

All data are availability from authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by BioDot. Inc. for microdroplet printing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafiemanesh, H.; Mehtarpour, M.; Khani, F.; Hesami, S.M.; Shamlou, R.; Towhidi, F.; et al. Epidemiology, incidence and mortality of lung cancer and their relationship with the development index in the world. J Thorac Dis. 2016, 8, 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafiemanesh, H.; Mehtarpour, M.; Khani, F.; Hesami, S.M.; Shamlou, R.; Towhidi, F.; et al. Erratum to epidemiology, incidence and mortality of lung cancer and their relationship with the development index in the world. J Thorac Dis. 2019, 11, E24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paez, J.G.; Janne, P.A.; Lee, J.C.; Tracy, S.; Greulich, H.; Gabriel, S.; et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: Correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004, 304, 1497–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, T.J.; Bell, D.W.; Sordella, R.; Gurubhagavatula, S.; Okimoto, R.A.; Brannigan, B.W.; et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004, 350, 2129–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merker, J.D.; Oxnard, G.R.; Compton, C.; Diehn, M.; Hurley, P.; Lazar, A.J.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis in Patients With Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology and College of American Pathologists Joint Review. J Clin Oncol. 2018, 36, 1631–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Lung Screening Trial Research, T.; Aberle, D.R.; Adams, A.M.; Berg, C.D.; Black, W.C.; Clapp, J.D.; et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011, 365, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Ding, X.; Li, M.; Jiang, F.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA is effective for the detection of EGFR mutation in non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015, 24, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanero, M.; Tsao, M.S. Circulating tumour DNA in EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer. Curr Oncol. 2018, 25, S38–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofanilli, M.; Budd, G.T.; Ellis, M.J.; Stopeck, A.; Matera, J.; Miller, M.C.; et al. Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004, 351, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamay, T.N.; Zamay, G.S.; Kolovskaya, O.S.; Zukov, R.A.; Petrova, M.M.; Gargaun, A.; et al. Current and Prospective Protein Biomarkers of Lung Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zvereva, M.; Roberti, G.; Durand, G.; Voegele, C.; Nguyen, M.D.; Delhomme, T.M.; et al. Circulating tumour-derived KRAS mutations in pancreatic cancer cases are predominantly carried by very short fragments of cell-free DNA. EBioMedicine. 2020, 55, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Liu, L.; Ji, Y.; Li, C.; Wei, T.; Yang, X.; et al. Enrichment of short mutant cell-free DNA fragments enhanced detection of pancreatic cancer. EBioMedicine. 2019, 41, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudecova, I.; Smith, C.G.; Hansel-Hertsch, R.; Chilamakuri, C.S.; Morris, J.A.; Vijayaraghavan, A.; et al. Characteristics, origin, and potential for cancer diagnostics of ultrashort plasma cell-free DNA. Genome Res. 2022, 32, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Wei, F.; Huang, W.L.; Lin, C.C.; Li, L.; Shen, M.M.; et al. Ultra-Short Circulating Tumor DNA (usctDNA) in Plasma and Saliva of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Patients. Cancers (Basel). 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padegimas, L.S.; Reichert, N.A. Adaptor ligation-based polymerase chain reaction-mediated walking. Anal Biochem. 1998, 260, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, S.; Sridhara, A.; Melo, R.; Richer, L.; Chee, N.H.; Kim, J.; et al. Microfluidics-based point-of-care test for serodiagnosis of Lyme Disease. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 35069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Rodriguez, M.; Serrano-Pertierra, E.; Garcia, A.C.; Lopez-Martin, S.; Yanez-Mo, M.; Cernuda-Morollon, E.; et al. Point-of-care detection of extracellular vesicles: Sensitivity optimization and multiple-target detection. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017, 87, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Lin, C.C.; Joon, A.; Feng, Z.; Troche, G.; Lira, M.E.; et al. Noninvasive saliva-based EGFR gene mutation detection in patients with lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014, 190, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Xi, L.; Cultraro, C.M.; Wei, F.; Jones, G.; Cheng, J.; et al. Longitudinal Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis in Blood and Saliva for Prediction of Response to Osimertinib and Disease Progression in EGFR-Mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxnard, G.R.; Paweletz, C.P.; Kuang, Y.; Mach, S.L.; O'Connell, A.; Messineo, M.M.; et al. Noninvasive detection of response and resistance in EGFR-mutant lung cancer using quantitative next-generation genotyping of cell-free plasma DNA. Clin Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 1698–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, W.; Gao, Y.; Xu, W.; Tao, J.; et al. Non-invasive diagnosis of early-stage lung cancer using high-throughput targeted DNA methylation sequencing of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). Theranostics. 2019, 9, 2056–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halvorsen, A.R.; Bjaanaes, M.; LeBlanc, M.; Holm, A.M.; Bolstad, N.; Rubio, L.; et al. A unique set of 6 circulating microRNAs for early detection of non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016, 7, 37250–37259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelman, J.A.; Janne, P.A. Mechanisms of acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 2895–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandara, D.R.; Li, T.; Lara, P.N.; Kelly, K.; Riess, J.W.; Redman, M.W.; et al. Acquired resistance to targeted therapies against oncogene-driven non-small-cell lung cancer: Approach to subtyping progressive disease and clinical implications. Clin Lung Cancer. 2014, 15, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelman, J.A.; Zejnullahu, K.; Mitsudomi, T.; Song, Y.; Hyland, C.; Park, J.O.; et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007, 316, 1039–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillai, R.N.; Behera, M.; Berry, L.D.; Rossi, M.R.; Kris, M.G.; Johnson, B.E.; et al. HER2 mutations in lung adenocarcinomas: A report from the Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium. Cancer. 2017, 123, 4099–4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Guha, U.; Kim, C.; Ye, L.; Cheng, J.; Li, F.; et al. Longitudinal Monitoring of EGFR and PIK3CA Mutations by Saliva-Based EFIRM in Advanced NSCLC Patients With Local Ablative Therapy and Osimertinib Treatment: Two Case Reports. Front Oncol. 2020, 10, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.; Cheng, J.; Chen, Y.L.; Jea, W.C.; Chen, W.L.; Chen, C.J.; et al. Electric Field-Induced Release and Measurement (EFIRM): Characterization and Technical Validation of a Novel Liquid Biopsy Platform in Plasma and Saliva. J Mol Diagn. 2020, 22, 1050–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.; Wei, F.; Yang, J.; Wong, D. Detection of exosomal biomarker by electric field-induced release and measurement (EFIRM). J Vis Exp. 2015, 52439. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, F.; Yang, J.; Wong, D.T. Detection of exosomal biomarker by electric field-induced release and measurement (EFIRM). Biosens Bioelectron. 2013, 44, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Q.; Ji, C.; Liu, R.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, A.; et al. Detection of soybean transgenic event GTS-40-3-2 using electric field-induced release and measurement (EFIRM). Anal Bioanal Chem. 2021, 413, 6671–6676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Morselli, M.; Huang, W.L.; Heo, Y.J.; Pinheiro-Ferreira, T.; Li, F.; et al. Plasma contains ultrashort single-stranded DNA in addition to nucleosomal cell-free DNA. iScience. 2022, 25, 104554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, F.; Patel, P.; Liao, W.; Chaudhry, K.; Zhang, L.; Arellano-Garcia, M.; et al. Electrochemical sensor for multiplex biomarkers detection. Clin Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 4446–4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S.H.; Tu, M.; Cheng, J.; Wei, F.; Li, F.; Chia, D.; et al. Development and validation of a quantitative, non-invasive, highly sensitive and specific, electrochemical assay for anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in saliva. PLoS ONE. 2021, 16, e0251342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.; Kim, Y.; Chia, D.; Spielmann, N.; Eibl, G.; Elashoff, D.; et al. Role of pancreatic cancer-derived exosomes in salivary biomarker development. J Biol Chem. 2013, 288, 26888–26897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).